HMS Bulolo—No. 1 Ship Signal Section, 1942-1945 (Part 1)

In the Summer 2019 edition of the Journal of the Royal Signals Institution, John Young wrote an excellent short history of 661 Signal Troop (LPD). I was prompted to write something about the troop’s predecessor and where it all began—No. 1 Ship Signal Section on HMS Bulolo during the Second World War. The article (somewhat bizarrely attributed to Captain Neil Donaghy, who in fact wrote the update about Project Caduceus) was published in the Journal but (due to another editing error) that version was incomplete and missing its footnotes and some illustrations. The story is told here in two parts…

HMS Bulolo

No. 1 Ship Signal Section was formed aboard HMS Bulolo at Chatham on 16 June 1942.[1] Arising out of the growing understanding of the requirements for effective command of amphibious landings, most importantly the need for a combined[2] headquarters afloat (a lesson learned on Operation Menace—the ill-fated attack on Dakar in 1940), HMS Bulolo was the first of several ships to be converted into a Landing Ship, Headquarters.[3] Designed as a passenger, general cargo and mail steamer, the 6,500-ton ship had piled her trade in the south Pacific for less than a year before war broke out in Europe. Bulolo was requisitioned in September 1939 and converted into an armed merchant cruiser, in which guise she worked as a convoy escort in the Atlantic until being bought by the Admiralty in March 1942. There then followed an extensive period of refitting—the forward cargo hold being converted into a three-deck suite of headquarters staff spaces and communications centres—which was completed that summer and by which time the conversion of a second ship, HMS Largs, had begun.[4] For most of this period, and for the period described here, HMS Bulolo was commanded by Captain R. L. Hamer DSO, the father of Lieutenant Colonel J. R. Hamer, Royal Signals.[5]

The initial establishment of No. 1 Ship Signal Section, the Army component of the tri-service communications staff, was for a major or captain in command (chief signalmaster), a subaltern as second-in-command (signalmaster), four sergeants (signal office superintendents) and 41 junior ranks of various trades. Posted from 11th Armoured Divisional Signals to take command was Captain H. Kenworthy. Like many excellent wartime signallers, Kenworthy had been an employee of the General Post Office before he was commissioned in September 1939; he would return to his post as a traffic superintendent in Preston after the war.[6] His second-in-command was Second Lieutenant K. A. Davis,[7] who joined from 1st Holding Battalion at Scarborough where he had just finished his training after being commissioned six months previously. Amongst the three sergeants who joined was Sergeant P. A. A. Court, who features later in this tale. The first 22 junior ranks also joined in June 1942.

Trade tests and a training programme began immediately, and Bulolo sailed via Sheerness, to load with ammunition, to Greenock where she would be based until the late autumn. From here there was regular movement of personnel to and from the ship and the Royal Signals Wing at the Combined Operations School (HMS Dundonald II) at Troon and for the next few months the men of the signal section would train at their principal tasks and in ship’s routine. On 13 July the section received its first American visitors, a group of US Army signal officers, who were briefed on the internal organisation of the ship and its procedures. From that day the section was ‘affiliated’ to First Army Signals and in August some men from that unit joined to bring the section up to strength.

In addition to controlling the amphibious landing, one of the primary tasks of the headquarters ship was to ensure coordination between the landing forces and supporting close air support. That work was carried out on board by an embarked Army Air Support Control and exercises in this work began in late July.[8] On 17 September a meeting was held on board to discuss procedures; commanding 7 AASC was Major J. D. Profumo MP, the future Secretary of State for War and the leading cast member in the ‘Profumo affair’.[9]

The radio room aboard HMS Bulolo in 1942; in the centre is the duty signalmaster.

On 14 October, HMS Bulolo was joined by Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough KBE, CB, DSO and a few days later by Major General Charles W. Ryder, Commanding General of the United States 34th Infantry Division, and Major General V. Evelegh OBE, General Officer Commanding the British 78th Division. On 24 October shore leave was suspended and two days later Admiral Burrough, Major Generals Ryder and Evelegh, and Air Commodore G. M. Lawson CBE, MC (the First Army air liaison officer) briefed the ship’s company on Operation Torch—an amphibious landing on the shores of North Africa. The operation would comprise three landings: The Western Task Force, which had sailed from the United States, would land troops on the Atlantic coast of Morocco; the Centre Task Force, would land at Oran in Algeria; and the Eastern Task Force at Algiers. Admiral Burrough would command the Eastern Task Force, the ground force for that landing being commanded by Major General Ryder.

That night HMS Bulolo sailed and joined a convoy at the mouth of the Clyde, beginning the voyage south to the Straits of Gibraltar under radio silence. On 6 November Bulolo and the accompanying convoy sailed into the Mediterranean and by 22.30 hours on 7 November was 12 miles off Algiers. Radio silence was broken at 01.00 hours the following morning as the landings commenced. The landings met with little opposition and on 9 October Bulolo came into port at Algiers. This somewhat ignominious arrival was at some speed and Bulolo hit the sea wall and a waterfront building due to damage to the engine room telegraph that had occurred the previous day when Bulolo narrowly escaped being hit by bombs dropped during a German air attack; the damage was unknown to the crew and resulted in a bell to the engine room being missed. With the divisional headquarters now ashore, the signal section spent the next few days responding to the demands of various groups of staff officers who required to use its extensive communications suite. A dispatch rider service was set up (using DRs from the two divisions) and on 12 November GOC First Army, Lieutenant General K. A. N. Anderson CB, MC, establish a temporary command post aboard. Although 90% of traffic on the day of the landings had been in plain language, over 23,000 cypher groups had been encoded or decoded by 14 November. On 10 December HMS Bulolo left Algiers in convoy bound for the United Kingdom, where she arrived a week later and where work was immediately started to make good on the lessons learned during Operation Torch.

The next task for HMS Bulolo and its signal section was not an amphibious landing but communications support for the Casablanca conference between the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill. The ship’s company was recalled from leave on 28 December and on 5 January, with a small team from No. 1 Ship Signal Section (one sergeant and 14 other ranks) and escorted by three destroyers, Bulolo sailed for Morocco. The remainder of the section meanwhile remained at HMS Dundonald II. The ship came alongside at Casablanca on 10 January and accepted a five-pair cable that allowed connection to the naval headquarters ashore and to the Anfa Hotel, where the conference was to take place. The lines to the hotel provided for a secure telephone link, a line to the hotel switchboard and a teleprinter circuit. The terminal equipment for the latter was provided by the Americans and a team arrived on board to train the British operators. The section’s war diary records that throughout the conference the telephone traffic was ‘heavy’. On 24 January after the conference the ship’s company was addressed by Churchill, who also toured the signal office and operations rooms. On 27 January Bulolo sailed for the United Kingdom arriving on the last day of the month.

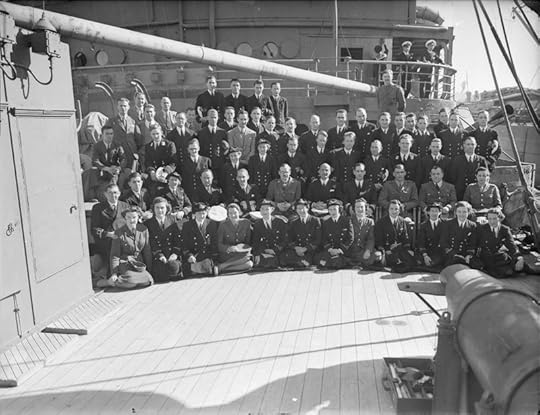

Officers of the cypher staff, including civilians and officers of the WRNS and the ATS, onboard HMS Bulolo for the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.

Meanwhile in Troon, the remainder of the ship’s section had undertaken some intensive training alongside the less experienced men of No. 2 Ship Signal Section destined for HMS Largs. Much of February and March was spent in Liverpool where the ship underwent a refit and when she returned to Greenock in the middle of the month Lieutenant Davis was notified of his promotion and posting to command No. 3 Ship Signal Section. He was replaced by Second Lieutenant F. E. J. Bishop from 47th Divisional Signals.[10] On 16 March, with the full signal section and a detachment from General Headquarters Reconnaissance Regiment (Phantom) HMS Bulolo sailed again, this time via Freetown, Durban and Aden to Adabiya at the northern end of the Gulf of Suez.

On 5 May Captain Kenworthy reported to General Headquarters Middle East in Cairo for a discussion about the future role of the signal section on Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. Reflecting the British force elements that would conduct the initial landing, attending the meeting were Brigadier R. T. O. Cary, Chief Signal Officer Eighth Army, Colonel J. B. Adams, Chief Signal Officer 13th Corps, and the commanding officer of 5th Divisional Signals, Lieutenant Colonel E. L. L. Vulliamy.

The planning for the Sicily landings was fraught with difficulty—principal British and American naval, army and air force commanders and their forces were spread across North Africa and the Middle East, and fighting in Tunisia continued into May 1943 occupying the staffs of the Eighth Army and the United States I Corps (later redesignated as US Seventh Army). There is no space here to expand upon the complexity of the planning for the operation or, indeed, the detail of plan or conduct of the landings. Suffice it to say that, on 10 July 1943 following airborne landings, two task forces would assault the island. The Western Task Force was largely American and the Eastern Task Force was largely British and Canadian. In the Eastern Task Force, the British 13th and 30th Corps would land at four groups of beaches, nicknamed Acid (North and South) and Bark (East, South and West (the western beaches being nicknamed Cent and Dime). The commanders for each landing would be embarked on a headquarters ship:

Acid—on beaches south of Syracuse in the Gulf of Noto—Force ‘A’, HMS Bulolo (Rear Admiral T. H. Troubridge DSO, commanding Force ‘A’; Lieutenant General M. C. Dempsey CB, DSO, MC, commanding 13th Corps; and Major General H. P. M. Berney-Ficklin CB, MC, commanding 5th Division).

Bark East—on the east of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘N’, HMS Keren.[11]

Bark South—on the end of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘B’, HMS Largs.

Bark West—on the west of the Pacino Peninsula—Force ‘V’, HMS Hilary.[12]

In his account of life as a junior Naval officer in the Mediterranean, Sub-Lieutenant F. Wade, who served as a cypher officer on HMS Bulolo in this period recalled:

‘Our masts bristled with radio and radar aerials. The forward cargo hold had been modified to house a complete interservice headquarters. The hull in this part of the ship had been strengthened to withstand a direct hit. The hold itself was divided into three decks. The lowest deck, where I would work, was given over to communications and housed army, navy and air force cypher and code rooms, and W/T receiving and transmitting rooms. The Main Signal Distributing Room was right in the centre. This was manned exclusively by naval personnel but from here messages were dispersed for all three services to the Operations Room on the next deck above…

The Operations or Support Control Room deck, as it was called, contained three signal filtering rooms, one each for Navy Ops, Army Intelligence and the RAF filter room, with the main Support Control Room in the centre. The main room was what I had always imagined a huge operations room to be. It was dominated by a large map of Sicily, about twenty feet square, parallel to the deck and raised off the floor like a huge table. Around it would stand the plotters moving little markers showing the disposition of the three forces. Large notice boards were mounted on the bulkheads, containing lists which constantly had to be updated. high above was a balcony which gave the senior officers a panoramic view of the place…

There was also an adjacent room behind a glass wall which served as the Fighter Control Room compartment. Our fighter aircraft cover was to be directed from here until a control centre could be set up ashore. Likewise, the generals would control their forces ashore from this room until they could land their own headquarters staff. It was estimated that these rooms would be used for three or four days after the assault, depending upon how well the landings went. The top deck contained rooms for the senior officers.’[13]

On 13 May GOC 5th Division visited, and work was put in hand to make the various changes to the operations room that he required. A few days later, operators from 5th Divisional Signals joined and after briefings they were sent to run equipment in the troopships, Reina del Pacifico and Duchess of Bedford. Exercises were conducted every day until 7 June when the staff of 5th Division joined the ship. The 13th Corps staff arrived the following day and there followed a series of exercises with the staff in message handling. A pigeon loft arrived onboard 10 June. On the final exercise communications proved satisfactory ‘more or less’ except for the pigeons, all but two of which were lost—‘on being tossed immediately assumed low level flying, apparently in search of LCTs on which they had been trained’.[14] On 23 June after a final ‘netting’ exercise all the Army outstation radios were closed down.

On 30 June HMS Bulolo sailed through the Suez Canal to Port Said, complete with a new compliment of pigeons, which being better settled performed well. Finally, on 5 July Bulolo sailed for Sicily with the Eastern Task Force and in the early hours of 10 July the landings commenced and during which Bulolo lay offshore south of Syracuse. By 11.00 hours that morning GOC 5th Division was ashore and on 15 July, with 13th Corps tactical headquarters now ashore, Army communications were closed down and Bulolo sailed for Syracuse harbour.[15] Two days later she sailed for Malta, her part in the operation over, and the men of the section enjoyed a day of shore leave. HMS Bulolo then returned to Alexandria.[16]

After a period of planning for an operation in the Aegean Sea that was ultimately cancelled (Operation Accolade—landings on Rhodes and the Dodecanese islands), HMS Bulolo and No. 1 Ship Signal Section sailed again, this time bound for Bombay (Mumbai) which she reached on 17 September, the first of two trips the ship made to south Asia.

1. (Back) The section was officially established, however, on 10 June as ‘Force Headquarters, Ship Signal Section’. The story here is derived largely from the section’s war diaries. See: The National Archives (TNA): WO 257/1 and WO 257/2.

2. (Back) In the early stages of the Second World War the term ‘combined’ was used to mean multi-service (today ‘joint’); it is used in that way here.

3. (Back) For a detailed account of the Dakar affair, including much detail on the requirement for and failure of the combined (joint) and Anglo-Free French communications see Marder, A. J. (2016). Operation Menace: The Dakar Expedition and the Dudley North Affair. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

4. (Back) HMS Largs was a former French Line banana boat, MV Charles Plumier seized at Gibraltar in 1940 and which had spent some time as an ocean boarding vessel. She became the home to No. 2 Ship Signal Section.

5. (Back) Captain Richard Lloyd Hamer DSO (13 January 1884-16 December 1951), commanded HMS Bulolo from October 1940 to December 1943. He had served throughout the First World War (Order of the Nile, Fourth Class) before retiring in 1923 and had been awarded the Royal Humane Society Bronze Medal in 1920. Recalled on the outbreak of the Second World War, he earned his DSO for a successful attack on a U-Boat while in command of the armed yacht HMS Viva II in June 1940. Lieutenant Colonel John Richard Hamer (19 December 1920-16 August 2011) was commissioned into Royal Signals in April 1942. He was mentioned in despatches in 1945 for his conduct in the North-West Europe Campaign with 56th Independent Infantry Brigade Signal Section. He retired in 1968.

6. (Back) Major Harold Kenworthy (17 June 1906-2 April 1987), Officer Commanding No. 1 Ship Signal Section, June 1942-September 1944.

7. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Kenneth Austen Davis (11 February 1912-6 June 1986). Later Officer Commanding No. 3 Ship Signal Section aboard HMS Hilary, for which he was mentioned in despatches for his conduct during the Normandy landings.

8. (Back) The assigned unit was No. 7 Army Air Support Control.

9. (Back) In most references Profumo’s military career during the war is glossed over, ignored, or incorrect. He proved to be a most able officer during Operation Torch, in the fighting in Tunisia and, for the remainder of the war, on the staff. Commissioned into the Royal Armoured Corps Territorial Army in July 1939 Profumo joined The Northamptonshire Yeomanry, a light tank regiment equipped with Guy armoured cars, and later came to specialise in air support operations. For his command of 7 AASC during the landings in North Africa he was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette (LG) 23 September 1943; 36180, p. 4222). On leaving 7 AASC in November 1943, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and joined the staff of Headquarters 15th Army Group (later renamed Allied Armies in Italy) as chief of the air liaison sub-section of the operations staff, responsible for the development of standard procedures for air support to the United States Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army. For his success in this he was made OBE in November 1944 (LG 21 December 1944; 36850, p. 5844. Recommendation: TNA: WO 373/72/93.) and awarded the United States Bronze Star Medal (LG 11 November 1947; 38122, p. 5353. Recommendation: TNA: WO 373/148/319.). Contrary to many accounts, Profumo did not take part in the D-Day landings but remained on the staff in Italy throughout 1944 and 1945.

10. (Back) Second Lieutenant (later Major) Frank Ernest John Bishop (20 September 1912-7 January 1981), wounded in action on 7 June 1944 (see Part 2) and posted to Combined Operations Headquarters.

11. (Back) HMS Keren was a liner, formerly the MV Kenya built in 1930 for the British India Company, converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry. She was not a true headquarters ship in the style of the others but had enough of a communications suite to allow command of the small naval and landing force (231st (Malta) Infantry Brigade).

12. (Back) HMS Hilary was a former British steam passenger liner, built in 1931. Like Largs, she began her war as an ocean boarding vessel before being converted into a Landing Ship, Infantry (Headquarters). She became the home of No. 3 Ship Signal Section.

13. (Back) Wade, F. (2005). A Midshipman’s War: A Young Man in the Mediterranean Naval War 1941-1943. Bloomington: Trafford Publishing. pp. 195-196.

14. (Back) Pigeons were kept aboard for nine months from May 1943 to January 1944, although they were used only during operation Husky. The pigeon service in the Mediterranean, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel J. A. Hollingworth, proved extraordinarily successful in almost every campaign across the theatre.

15. (Back) The section war diary (TNA: WO 257/1) contains a short report on the operation that includes the radio nets established and their performance.

16. (Back) For more detail on Operation Husky see the despatches:

‘The Conquest of Sicily from 10th July 1943 to 17th August 1943.’ LG 12 February 1948; 38205.

‘The Invasion of Sicily.’ LG 28 April 1950; 38895.