Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 6

September 9, 2017

The East Coast Floods, 1953

As I work on my book about Royal Signals gallantry awards, the news is dominated by accounts of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Jose and Katia and the massive earthquake in Mexico. By coincidence, the section that I am writing is about the East Coast Floods of 1953.

[image error]

Canvey Island, 1953

On 31 January 1953, an extremely heavy storm coupled with a high spring tide led to a devastating natural disaster in the low-lying areas around the North Sea. Sea defences were breached, coastal areas were flooded and ships were lost. Over 2,500 people were killed—1,836 in the Netherlands, 307 in England, 19 in Scotland and 28 in Belgium; 361 people were killed at sea, including 133 on the Larne-Stranraer ferry m.v. Princess Victoria. This was one of the worst natural disasters to hit the region; the rescue work took many days and recovery took many months.

There were numerous acts of gallantry recorded over the period and British awards were made to civilians and military personal, including honorary awards to men of the United States Air Force stationed in East Anglia. These and the meritorious service awards that followed the rescue effort were spread over several editions of the London Gazette, including the Coronation Honours list; the honorary awards were not published. There were more British awards made in the aftermath of this disaster than for any other single, non-warlike event in British history.

Gallantry Awards

Ninety-five gallantry awards were made in connection with the floods (not including honorary awards).

The bulk of such awards to civilians were published, with citations, in an edition of the London Gazetted dated 28 April 1953. The list comprised 71 awards—three MBE (Civil Division), three George Medals, 17 British Empire Medals (Civil Division), 47 Queen’s Commendations for Brave Conduct, and one Queen’s Commendations for Valuable Service in the Air. In addition, an edition of the London Gazette dated 6 October 1953 recorded the awards, with citations, related to the sinking of m.v. Princess Victoria—a posthumous George Cross to the ship’s radio officer, four MBE (Civil Division) to ship’s captains who responded to the distress call, and two British Empire Medals (Civil Division) to Royal National Lifeboat Institution coxswains who also responded. The final awards were published in the London Gazette dated 17 November 1953—three British Empire Medals (Civil Division) to men who disposed of volatile explosives from a flooded factory on Bramble Island.

The awards to British Army and Royal Air Force personnel ‘in recognition of gallantry in connection with the East Coast Floods’ were published, without citations, in a single edition of the London Gazette dated 28 April 1953. The military citations reproduced below may be found in the National Archives in the series AIR 2; there are no surviving citations for the Queen’s Commendations.[1] A single award for gallantry to a petty officer of the Royal Navy was published, with citation, in the London Gazette dated 22 May 1953. For completeness, all of the military awards are recorded here:

MBE (Military Division)

Captain Charles Lee Bernard Beardmore, Royal Regiment of Artillery (Territorial Army)

This TA Officer on his own initiative reported for flood duty with his Regiment on 1st February and spent 32 hours in the Mablethorpe and Trusthorpe flood areas working continuously without sleep and with little food from Sunday morning 1st February until the evening of the following day. It is estimated that he was personally responsible for the evacuation of approximately 140 civilians.

On one occasion, he pushed a collapsible boat (which he himself took to Trusthorpe), full of evacuees, half a mile to shallower water, loaded them on his gun tractor and carried them to safety. On other occasions, he walked one mile through high flooded water for additional vehicles to evacuate civilians stranded in isolated farms. He also salvaged two civilian buses, filled them with evacuees and towed them to dry land.

His determination and resource under most trying conditions were an inspiration to all who saw him and especially to the man under his command.

Lieutenant John Garton Jones, The Royal Norfolk Regiment

On 31st January, 1953 a call was received from King’s Lynn for two 3 tonners for rescue work. Although there was no request for an Officer, Lieutenant Jones detailed himself to go out in charge of the two vehicles. The Lieutenant and his staff evacuated all invalid and aged persons from Diamond Street, King’s Lynn, where there had been deaths from drowning and the flood water was still high. In spite of a strong wind, extreme cold, approximately 3 ft. to 4 ft. of flood water underfoot, under-water obstacles and slime presenting unseen hazards, the Lieutenant and his squad did magnificent work. Lieutenant Jones himself went back again and again into houses where rescue work was very difficult and he rescued a number of persons whom he carried down difficult staircases and through deep water in the lower storey rooms. He set an example to civilians and others. Lieutenant Jones did not spare himself until the evacuation was completed and he himself was nearing the point of absolute exhaustion.

British Empire Medal (Military Division)

C/JX 154853 Petty Officer Samuel John Horlick, HMS Barsound

When HM Dockyard, Sheerness was flooded on the night of 1st February, 1953, a ship in dry dock was in danger of capsizing owing to the. flood waters pouring into her engine room. Petty Officer Horlick organised a party of five ratings and, securing a dinghy which was drifting nearby, boarded the ship. The party had already seen another ship capsize but, in spite of this, and fully aware of the risk they ran, Petty Officer Horlick led the party below by the aid of candle lanterns. He found where the water was flooding into the engine room and, working for nearly an hour in semi-darkness, the party succeeded in making the ship reasonably watertight. Petty Officer Horlick set a splendid example of courage and leadership and showed outstanding initiative and knowledge of what to do to ensure the safety of one of HM ships.

1447833 Sergeant Cornelius Eastham, Corps of Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers

Displayed initiative, courage and resource during the flooding at Landguard Point on the night of 31st January/1st February 1953.

Sergeant Eastman was awakened about midnight owing to the gale and flooding. Hearing cries coming from ‘B’ Block, Married Soldiers Quarters, he immediately proceeded in the dark, through three to four feet of turbulent and debris covered water to assist a soldier, his wife and two young children to get clear of their flooded quarter. He carried two young children back to his own quarter. Then hearing cries from ‘C’ Block he again set out and made his way to the quarter occupied by a sergeant and family. On arriving at the quarter he considered that that the prospect of getting the family back through the flood water to the higher ground was not practicable. He therefore remained with them for two hours until the water had somewhat subsided, and then assisted the family to ‘A’ Block, Married Soldiers Quarters.

22246831 Sergeant Thomas Stephenson, Royal Corps of Signals

Corporal T. Stephenson was driving the leading vehicle or the convoy of army vehicles which reported to the Civil Authorities on Canvey Island at approximately 0630 hrs. on 1st February 1953 for flood rescue work.

He parked his vehicle where directed and then spent the rest of the day on rescue work.

He was working in the most severely flooded area where bungalows had been flooded to a depth of about 3’6” to 5’. He spent from about 0700 hrs. until about 1800 hrs. without a break carrying old people and children who had been isolated by the floods to places of safety from which they could be evacuated. He had no previous knowledge of the area in which he was working and the sunken paths and deep ditches, filled in some places with water to a depth of 9’ constituted a very grave danger to which he paid no attention. He worked without any rest in this very dangerous area, often wading in water to a depth well above his waist without giving any thought to his own safety until ordered to stop when rescue work was made impossible by darkness.

22204308 Bombardier Claude Henry Turpie, Royal Regiment of Artillery

Displayed initiative, courage and resource during the flooding at Landguard Point on the night of 31st January/1st February 1953.

The quarter in ‘B’ Block was badly flooded and he and his family had to be assisted clear of the quarter and flood water. On reaching ‘A’ Block with his family he heard cries coming from the direction of the railings around the RAF Experimental Establishment, he thereupon proceeded through the flood water and saw a Corporal and his wife standing on a small wall, clinging to the railings. Knowing that a ditch was between him and the wall he found a plank and positioned it so that the Corporal and his wife could walk across it into water that was only two to three feet deep. Bombardier Turpie then heard cries coming from the railings and once more set out and found a woman and baby clinging to the railings. He carried her and the baby through the flood water which was turbulent and rat infested and with much debits floating about. Bombardier Turpie acted with courage and determination.

Queen’s Commendations for Brave Conduct

Wing Commander Charles Vivian Winn DSO, OBE, DFC, Royal Air Force

Pilot Officer Philip Jeremy Graham, Royal Air Force

Pilot Officer James Thomson Greenwood, Royal Air Force

Pilot Officer Trevor Charles Purling, Royal Air Force

2818008 Leading Aircraftwoman Julia Josephine Goodman, Women’s Royal Air Force

2812844 Leading Aircraftwoman Agnes Kirkland, Women’s Royal Air Force

2509086 Leading Aircraftman David William Martin, Royal Air Force

3513603 Aircraftman 2nd Class Keith Summerscales, Royal Air Force

[image error]

A Royal Signals Corporal at Canvey Island. Is this Corporal Stephenson?

Honorary Awards

The United States 3rd Air Force provided significant materiel and personnel to assist in dealing with the floods and several men acted most gallantry during the rescue efforts. In addition, seventeen Americans, military and civilian, were killed and a little under 70 families lost all their possessions.[2] The award of the George Medal to Airman 2nd Class Reis L. Leming was authorised on 20 February 1953 and presented on 15 April by the Home Secretary, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe. The remaining awards were authorised on 2 July 1953 and presented on 1 September 1953, again by Sir David Maxwell Fyfe.

MBE (Military Division)

Major Julian E. Perkinson, 47th Installation Squadron, United States Air Force

Major Parkinson [sic] received a telephone call informing him that the sea had gone over the wall in Hunstanton and that people living along the beach were in danger. He went to Hunstanton where he found the South Beach flooded and people on rooftops unable to get to safety. Major Parkinson immediately took command of the situation. He called the Royal Air Force Station, Sculthorpe, for rescue personnel, equipment and vehicles which could be used for rescue operations. Major Parkinson supervised the clearing of the road of civilian vehicles that had been flooded and were unable to be removed under their own power. The road was cleared to enable the rescue boats to be launched upon their arrival. In addition to disaster activities at Hunstanton, he organised and supervised rescue operations both at Heacham and Holme flood areas. Through his efforts the rescue activities were organised and co-ordinated so that the maximum use of equipment and personnel were possible. Many persons were rescued from the flood waters as a result of his initiative in taking charge of the overall situation. Major Parkinson directed the entire operation continuously from 7.00 pm on the 31st of January until he was relieved at 7.00 pm on Sunday the 1st of February.

George Medal

Staff Sergeant Freeman A. Kilpatrick, 3rd Communications Squadron, United States Air Force

On the evening of 31st January, 1953 Staff Sergeant Freeman A. Kilpatrick knowing that flood tides and winds above 85 knots were threatening to engulf the area of his house in Hunstanton, without regard for his own safety ventured out into the storm for the purpose of warning other families, both American and English, of the impending disaster. He placed his family on the second floor of his home then swimming in the raging water and debris, he rescued eighteen persons. He then swam back to his home to evacuate his wife, child and two English people to the roof of his home where they remained until the following morning when rescued. Through his efforts, other families were able to escape while he and his family were forced to suffer the worst of the storm during the night.

[image error]

Airman Second Class Reis L. Leming

Airman Second Class Reis L. Leming, 67th Air Rescue Squadron, United States Air Force[3]

On the beach at Hunstanton Airman 3rd [sic] Class Reis Leming saved over 27 people from the flood. He was wearing an American exposure suit and, swimming with a rubber dingy in tow, he picked up these people who had been isolated by the floods. After the third trip he, himself, collapsed because of exhaustion.

British Empire Medal (Military Division)

Airman First Class Jake J. Smith, 67th Air Rescue Squadron, United States Air Force

Airman Smith with complete disregard for his own personal safety and well-being, voluntarily displayed heroism above and beyond the call of duty. He was a rescue crew member of an amphibious track laying vehicle which was sunk by two large waves. He was stranded soaking wet on a rooftop himself for two hours. Later Airman Smith in helping to evacuate survivors, heard another airman calling for help and he plunged into the water and dragged the man, who had fainted, and the seven survivors on the life raft twenty yards to safety. Using a raft himself, he located three other survivors. Airman Smith continued searching for survivors in the icy waters for two hours until his Commanding Officer ordered him to rest. After resting an hour, Airman Smith again volunteered to go out in the flood waters to launch a stranded airborne life boat stuck on the railway track.

Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct

Airman First Class Jimmy Brown, 47th Air Police Squadron, United States Air Force

Technical Sergeant John J Germaine, United States Air Force

For rescuing persons trapped by the floods at Heacham, Norfolk, on the 31st of January, 1953.

[image error]

Sir David Maxwell Fyfe congratulating the men during the ceremony at the Home Office on 1 September 1953. The men are, from left to right—Technical Sergeant John J. Germaine, of Big Hollow, Deposit, New York, and Airman First Class Jimmy Brown, of Chattanooga, Tennessee, both of whom were awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct; Airman First Class Jake J. Smith, of Memphis. Tennessee, British Empire Medal; Staff Sergeant Freeman A. Kilpatrick, of Opelika, Alabama, George Medal; and Major Julian E. Perkinson, of Norfolk, Virginia, Honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire.

Awards for Meritorious Service

Civilian meritorious service awards relating to the floods were published as part of the Coronation Honours list in the London Gazette on 1 June 1953. All these awards are described as, ‘For services during the recent floods in the Eastern Counties.’ They comprised three CBE (Civil Division), 16 OBE (Civil Division), 28 MBE (Civil Division), and 90 British Empire Medals (Civil Division). Although the appointment or role of the recipients was recorded, there were no accompanying citations.

The meritorious awards to British Army and Royal Air Force personnel were published in a separate edition of the London Gazette dated 1 June 1953, also without citations, and comprised three OBE (Military Division), five MBE (Military Division), two British Empire Medals (Military Division) and one Queen’s Commendation for Valuable Service in the Air. There were no Royal Navy awards specifically for service during the floods.

1. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). (1953). Royal Air Force: Rescue Services (Code B, 67/33): Assistance to civil ministries: East Coast and Netherlands floods, 1953. AIR 2/11955.

2. (Back) For details of the support provided and for the citations for honorary awards see: TNA. PRO. (1953). Royal Air Force: Rescue Services (Code B, 67/33): Assistance to civil ministries: East Coast and Netherlands floods, 1953. AIR 2/11955.

3. (Back) Leming was also awarded the Soldier’s Medal, the broadly equivalent United States Army and Air Force award (the Airman’s Medal was not established until 1960). In August 1953, Leming went to the rescue of two holiday makers whose boat capsized off the beach at Hunstanton.

August 5, 2017

‘The Boche had beaten us, and the slaughter terrific.’

The graves of Lieutenant Colonel S J Somerville, the Commanding Officer, and Captain R D Miles, C Company, Brandhoek New Military Cemetery No. 3

Few of the 154 officers and men of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers who were killed immediatley prior to or during the attack on 16 August 1917 lie in marked graves—three-quarters are commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial, a substantially higher proportion that those killed on 1 July 1916 who are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial. There are four primary reasons for this: firstly, very few bodies could be recovered immediately after the action from the area over which the Battalion had attacked; secondly, the area was subjected to continued severe shelling and was not captured until over a month later, by which time many of the bodies were destroyed; thirdly, in early 1918 a narrow gauge railway was built over the area from which the attack was launched, and, fourthly—in consequence—few of the bodies were identified by name in the post-war battlefield clearance.

When the heavy rain began on 31 July 1917, the men of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers were at Watou, seven miles west of Ypres preparing for the forthcoming offensive. On 2 August, the Battalion was ordered forward with 13th Royal Irish Rifles and two battalions from 109th Brigade to take over a reserve position in the trenches from which 55th (West Lancashire) Division had attacked on the first day of the battle. This period in the line was short but exhausting, spent in muddy, partially destroyed and crowded trenches and, in the last few hours as the men began the move back west of Ypres, under gas attack. Miraculously, casualties were few but two men, James Greer from Rathfriland and Isaac Hague from Nottingham, would die of their injuries some days later.[1]

Although it was hoped to keep back the attacking battalions, the conditions made their use in the line prior to the attack inevitable and the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers returned to the line on 14 August, this time to the area of Pommern Redoubt, from which the attack would be launched two days later, and support trenches slightly farther back. That day saw one of the heaviest deluges of rain experienced during the battle and the Battalion moved in very difficult, tiring conditions that left the men soaked through and ill-prepared for the action to come. The following night Battalion Headquarters and all four companies assembled at Pommern Redoubt.

[image error]

The attack by 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, 16 August 1917

I am not going to describe the attack, suffice it to say that it failed. The thick wire diagonally across the Battalion’s path, the German defence in depth from reinforced concrete dugouts that withstood the preliminary and creeping barrages, the weather and its effect on the ground conditions (described in the war diary as ‘very much cut up by shell fire & very heavy to cross.’) and, most importantly, the weariness of the attacking troops all contributed to the failure. Having attacked at 4.45am, by mid-morning the survivors were back in the trenches that they had left only a few hours before. Captain Godson, formerly the Battalion’s Intelligence Officer and now on the staff of 108th Brigade, later wrote:

‘About 8.30am saw many of our men coming back, and then Germans in the Battery gun pits on Hill 35. Things looked bad, so I moved up to the front line… There I found chaos…of the 9th R. Ir. Fus. Col Somerville badly wounded (died soon afterwards), Capt Shillington badly wounded (died of wounds), 2nd Lt Miles badly hit (died of wounds afterwards), likewise Lt Trinder, a gallant Irishman. The Boche had beaten us, and the slaughter terrific.’ [2]

[image error]

Reverend Samuel Mayes

Most of the wounded were dealt with by Captain Burrows, the Medical Officer, assisted by the Chaplain, Samuel Mayes, in Plum Farm, 1,000 yards south-west of Pommern Redoubt. Burrows treated over 300 men in forty hours in appalling conditions under shell and machine-gun fire before they were evacuated to the three Casualty Clearing Stations near Brandhoek west of Ypres. The final casualty report would make grim reading.

Reverend Mayes compiled a very detailed list that recorded casualties by company. Predictably, most of those noted as ‘missing’ had been killed in action, and many of the men whom he recorded as wounded and who died on 16 August were to be declared ‘killed in action’ on that date.[3]

In addition to the three men who died (and an unknown number of wounded) in the days prior to the attack, the casualty tally for 16 August 1917 totalled 441 all ranks: 151 killed or died of wounds, 280 wounded, and 10 captured.

Of these 154 officers and men who were killed or died of wounds, 111 are commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial.

Thirteen officers and men were buried near the medical facility where they died.

Only 30 other men who took part in the attack on 16 August 1917 are buried in named graves and none of these graves are near where the men fell or where they were originally buried. In addition, I have found only two soldiers ‘Known Unto God’ who are recorded as being men of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers.

Plotted on the map below are the original burial locations of these 32 men. The map used was printed in 1918 and it shows the railway built over the area from which the attack was launched. Also marked is the area of the Battalion’s attack and Plum Farm where the Regimental Aid Post was located. Most of the bodies were recovered in 1919 but five were found in 1920 and two in 1921. Why some men are buried so far north of the Battalion’s attack is inexplicable given the context of the fighting. It should be noted that the date of the original burials are not known and, for some men, it is likely to be considerably after the action on 16 August. The serial numbers on the map correspond to those on this record of the burials.

[image error]

16 August 1917, Original Burials

The near destruction of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers on 16 August 1917 resulted in its irrevocable change. Few of its original members were still serving with it now. In September 1917, the Battalion was amalgamated with 2nd North Irish Horse and in 1918 an influx of English soldiers were welcomed into its ranks.

If you are visiting Ypres over this centenary period, consider visiting the cemeteries in which these few identified men of the Battalion lie—the attached casualty list provides the detail.

[image error]

9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, Casualty List, Battle of Langemarck, 16 August 1917

1. (Back) Hague is erroneously recorded in Blacker’s Boys as one of the casualties from the period immediately prior to the attack on 16 August.

2. (Back) Godson, E A. (No date). The Great War 1914-1918. Incidents, Experiences, Impressions, and Comments of a Junior Officer. Hertford: Self Published. p 19.

3. (Back) The original list may be found in the Royal Irish Fusiliers museum, Armagh.

July 16, 2017

Army Women 100

Dedicated to the women with whom I have had the privilege to serve, particularly those who have demonstrated their courage and endurance on operations in Northern Ireland, the Balkans, Sierra Leone, and Iraq. This is my contribution to #ArmyWomen100.

In January 1917, Lieutenant General Henry Lawson[1] submitted a report that recommended the recruitment of women to fill administrative jobs in France, releasing men for employment farther forward.[2] The Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps was formally instituted by Army Council Instruction No. 1069 on 7 July 1917.[3] The WAAC became Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps on 9 April 1918. At the end of the war its personnel were demobilised and the Corps was finally disbanded on 30 April 1920, although a small detachment remained attached to the Graves Registrations Commission in France until September 1921.[4]

On 25 March 1916, the Military Medal had been instituted for non-commissioned officers and men of the Army for ‘acts of bravery’.[5] Three months later, in a supplementary Royal Warrant of 21 June, the award was extended to women (British and foreign) for ‘bravery and devotion under fire’.[6] The first awards soon followed—to Lady Dorothie Feilding for her gallantry as an ambulance driver in Belgium (she had previously been awarded the French Croix de Guerre and would later be awarded the Belgian Ordre de Léopold II for her services) and to five nurses for their gallantry during the bombing of 33rd Casualty Clearing Station at Bethune, France on 7 August 1916.[7]

[image error]

Unit Administrator Margaret Gibson MM

The first Military Medal to Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps was awarded to Unit Administrator Margaret Gibson for her conduct on the night of 21/22 May 1918 when the town of Abbeville was bombed:

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during an enemy air-raid when in charge of a Q.M.A.A.C. camp which was completely demolished by enemy bombs, one of which fell within a few feet of the trench in which the women were sheltering. During the raid, Unit-Administrator Gibson showed a splendid example. Her courage and energy sustained the women under the most trying circumstances and undoubtedly prevented serious loss of life.’[8]

Sadly, Margaret Gibson MM did not survive the war; she died of dysentery on 17 September 1918 and is buried in Mont Huon Cemetery at Le Treport.

A total of 146 awards of the Military Medal have been to women between 1916 and the suspension of the award in 1993.[9] The most recent were to soldiers of the Women’s Royal Army Corps serving in Northern Ireland—Lance Corporal Sarah Warke in 1973[10] and Lance Corporal Diane Cooper in 1990.[11]

A less well-known award for gallantry and self-sacrifice during the years in which the QMAAC existed was the Medal of the Order of the British Empire. The Order had been instituted in 1917 and the medal had been used to reward industrial workers for acts of courage and self-sacrifice.[12] In December 1918 a Military Division of the Order was instituted and the medal became the principle reward for acts of ‘gallantry or self-sacrifice or distinguished service’ for the women of the Corps during the First World War. Of 510 military awards, 297 were awarded to women of the QMAAC, 22 to the WRNS, one to the WRAF, and two to drivers of the Women’s Legion serving with the Army Service Corps.[13]

Formed on 9 September 1938, the Auxiliary Territorial Service provide a vital component of the British Army, at home and overseas, during the Second World War and later in Palestine. In addition to a wealth of administrative roles, women served in technical trades and in anti-aircraft units. Their service was not without risk and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates over 900 women of the ATS who were killed in action or died during the war. The ATS was subsumed by the Women’s Royal Army Corps when it was formed on 1 February 1949.

During the Second World War, six women were decorated with the British Empire Medal for ‘gallant conduct in carrying out hazardous work in a very brave manner’—one for rescuing aircrew from a crashed and burning aircraft, two for gallantry in anti-aircraft units during air attacks, two for providing medical aid during an industrial accident, and one for rescuing a child from a dangerous canal.[14] In addition, five women serving with Home Forces were commended for brave conduct.

[image error]

Lance Corporal Margaret Richards GM

Notably, just after the war Lance Corporal Margaret Richards earned the first George Medal awarded to a female soldier of the British Army for he gallantry in treating injured soldiers following an explosion at an ammunition depot in Lincolnshire. Her citation recorded that she:

‘…was an inspiration to the men around her. Her cheerfulness and courage under dangerous and unpleasant conditions were outstanding and her efficiency undoubtedly assisted the Medical Officer to prepare the injured men expeditiously for the journey to hospital and was, therefore, in all probability instrumental in saving further loss of life.’[15]

For another project, I compiled a full list of all the awards to the Auxiliary Territorial Service.

Although not actually part of the British Army, it would be remiss to not mention the Women’s Transport Service (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry). The women of FANY had served gallantly in all theatres during the First World War. In the Second World War, in addition to providing women to the ATS and in a range of support activities, FANY proved an ideal organisation to support Special Operations Executive. It acted as a holding unit for many of the women recruited to work behind enemy lines and who suffered so grievously for their bravery—13 of the 55 female agents of SOE were captured and killed. The organisation can also claim some notable firsts: The first award of the George Cross to a woman was to Odette Sansom, who was betrayed and captured in France. Her citation concluded that: ‘During the period of over two years in which she was in enemy hands, she displayed courage, endurance and self-sacrifice of the highest possible order.’[16] The first posthumous award of the George Cross to a woman was to Violette Szabo, who was captured on her second mission and according to her citation: ‘She was then continuously and atrociously tortured but never by word or deed gave away any of her acquaintances or told the enemy anything of any value.’[17] Szabo was murdered in Ravensbrück concentration camp. She had previously served with the ATS but had left in 1942 when she became pregnant; her husband was killed in action later the same year. Two George Medals were also awarded to women of FANY who served with SOE, including the first award of the George Medal to a woman attached to the British Army. That first award was to New Zealand-born Nancy Wake,[18] for her gallantry in leading French maquisards. The second, an honorary award, was to the enigmatic Polish émigré Krystyna Giżycki, who served under the name Christine Granville.[19]

Serving alongside their male counterparts, the officers and soldiers of the WRAC continued the tradition of their forebears. The majority of the awards to the Corps for gallantry and for meritorious service came from the prolonged campaign in Northern Ireland. In addition to the Military Medals mentioned above, the first award of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal to a female soldier was to Acting Sergeant Jane Freeman in 1981.[20]

Since then women in the British Army have earned seven other Queen’s Gallantry Medals—four in Northern Ireland; one following a helicopter crash in Bosnia and Herzegovina; one for treating wounded soldiers following an explosion in Afghanistan; and one for clearing explosives following an industrial accident in the UK. Only three of those, however, were to soldiers of the WRAC. In late 1990 the process began to transfer women out of the WRAC and into the Corps to which they were attached; the WRAC was disbanded on 6 April 1992. In consequence, these four awards of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal were to soldiers of the Royal Logistic Corps and the Royal Army Medical Corps.

[image error]

Private Michelle Norris MC

Finally, a notable ‘first’. In Iraq on 11 June 2006, Private Michelle Norris, Royal Army Medical Corps, was serving as a medic with 1st Battalion, The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment when she treated a wounded soldier under fire during an intense engagement against insurgent forces. Her actions earned her the first Military Cross to be awarded to a woman.[21] To date, four such awards have been made, all for gallantry in Afghanistan—two to soldiers of the Royal Army Medical Corps and one to a sailor, Able Seaman Kate Nesbitt, a Medical Assistant serving with 1st Battalion, The Rifles.

There is no doubt that, 100 years after the raising of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps, as they take their rightful place at the forefront of military operations, the women of the British Army will continue to demonstrate courage of a high order and receive just reward.

1. (Back) Later Lieutenant General Sir Henry Merrick Lawson KCB.

2. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). (16 January 1917). Physical Categories and number of Men Employed out of the Fighting Area in France. WO 106/362.

3. (Back) The branch of the Adjutant General’s Department responsible for women was established on 19 February 1917. The formation of the new Corps was announced in the press soon afterwards, although speculation on the issue had appeared in the press prior to the Lawson’s report. See, for example: ‘Women for Army Work in France.’ (11 January 1917). The Guardian. p 4. Recruiting for the new Corps began in March 1917. For the Army Order see: TNA. PRO. (1917). Recruitment of women: early history of Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps. NATS 1/1300.

4. (Back) For an excellent history of the Corps in France see: Philo-Gill, S. (17 April 2017). The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps in France, 1917 – 1921: Women Urgently Wanted. Barnsley: Pen & Sword.

5. (Back) London Gazette 5 April 1916. Issue 29538, page 3693.

6. (Back) London Gazette 27 June 1916. Issue 29641, page 3643.

7. (Back) The Lady Dorothie Mary Evelyn Feilding, Monro Motor Ambulance; Matron Miss Mabel Mary Tunley RRC, Sister Miss Beatrice Alice Allsop, Sister Miss Norah Easeby, and Staff Nurse Miss Ethel Hutchinson, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service; and Staff Nurse Miss Jean Strachan Whyte, Territorial Force Nursing Service. See: London Gazette 1 September 1916. Issue 29731, page 8653. For details of the awards to the nurses of QAIMNS and the TFNS see: Scarlet Finders.

8. (Back) Unit Administrator Mrs Margaret Annabella Campbell Gibson. See: London Gazette 8 July 1918. Issue 30784, page 8029. The other awards to women of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry published in that Gazette were for bravery during a bombing attack on 18 May 1918 near St Omer.

9. (Back) For a complete account of these awards see: Gooding, N G. (18 August 2013). Honours and Awards to Women: The Military Medal. London: Savannah.

10. (Back) W/439979 Lance Corporal Sarah Jane Warke, Women’s Royal Army Corps. London Gazette 18 September 1973. Issue 46080, page 11116.

11. (Back) W0476512 Lance Corporal Diane Lesley Cooper, Women’s Royal Army Corps. London Gazette 10 May 1996 (to be dated 15 May 1990). Issue 54393, page 6549.

12. (Back) For a detailed history of the earliest version of the Medal of the Order see: Willoughby, R. (2012). For God and the Empire—The Medal of the Order of the British Empire 1917-1922. London: Savannah.

13. (Back) Women’s Royal Naval Service: London Gazette 9 May 1919. Issue 31331, page 5776. Woman’s Royal Air Force: London Gazette 3 June 1919. Issue 31378, page 7035. Queen Mary’s Auxiliary Army Corps & Women’s Legion: London Gazette 23 January 1920. Issue 31750, page 964.

14. (Back) From 1922, but particularly from the beginning of the Second World War, the British Empire Medal (prior to 1941 called the Medal of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire for Meritorious Service) could be awarded as a third level award for gallantry in certain circumstances. From 1958 crossed silver oak leaves on the ribbon denoted such an award. The medal ceased being awarded for gallantry when the Queen’s Gallantry Medal was instituted in 1974.

15. (Back) London Gazette 2 July 1948. Issue 38340, page 3825.

16. (Back) London Gazette 20 August 1946. Issue 37693, page 4175.

17. (Back) London Gazette 17 December 1946. Issue 37820, page 6127.

18. (Back) London Gazette 17 July 1945. Issue 37181, page 3676.

19. (Back) An honorary award granted on 23 January 1946.

20. (Back) London Gazette 14 April 1981. Issue 48583, page 5528.

21. (Back) London gazette 15 December 2006. Issue 58183, page 17359.

June 23, 2017

The George Cross

Why has there been so little reaction to the recent award of the George Cross to Dominic Troulan?

[image error]

The George Cross (Photo Dix Noonan Web)

Given the circumstances, it is not surprising that news coverage of the recent gallantry awards list has been dominated largely by those of the George Medal to Bernard Kenny and PC Keith Palmer for their gallantry and sacrifice in incidents at home in the United Kingdom. It is somewhat disappointing, however, that so little has been made of the astonishing and prolonged courage that earned Dominic Troulan the nation’s highest award for gallantry; particularly given the rarity of this prestigious decoration for ‘acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger.’[1]

Additionally, both the emphasis on the George Cross being a ‘civilian award’ and commentary about Troulan’s award being the first civilian award for 41 years ignore the reality behind the awards of the George Cross, George Medal and Queen’s Gallantry Medal.

The institution of the George Cross (and George Medal) was announced by King George VI in a radio broadcast on 23 September 1940 and the first awards soon followed. Although intended as an award for civilians in ‘all walks of life’—primarily those who responded with courage of the highest order during the blitz—it was also awarded to military personnel. Indeed, by the end of 1940, 12 of the first 16 awards were to members of the Armed Forces, as were 76 of the first 100. The number of submissions from the Armed Forces was such that the Committee responsible for determining awards[2] recommended that the number of submissions should be reduced to maintain the highest standard.[3]

Since its institution, there have been only 162 direct awards of the George Cross (which does not include the awards to the island of Malta and to the Royal Ulster Constabulary).[4] It may be surprising to note that only 50 awards have been made to civilians and, although some of the awards to military personnel have been for acts of gallantry without any military connection (for example, the recent award to Captain S J Shephard Royal Marines), the majority of awards to both military and civilian recipients (113) have been for acts of gallantry in warlike conditions or related to terrorist incidents. Over 50% of all awards have been posthumous.

See my analysis of awards of the George Cross.

See my register of recipients of the George Cross.

[image error]Dom Troulan spent the majority of his adult life in the Armed Forces, in specialist units either on or in direct support of operations. His actions on 21 September 2013 in the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi were against four determined terrorist adversaries from the Somali, militant, Islamist group al-Shabaab, who killed 67 people and wounded over 175 others. Troulan was armed and fought off the attackers on at least two occasions during his repeated forays into the mall. He and his repeated acts of bravery cannot be described accurately as ‘civilian’ and they provide an excellent example of how well suited is the George Cross (and George Medal and Queen’s Gallantry Medal) for recognising gallantry in such complex circumstances.

His citation is worth repeating in full:[5]

On 21 September 2013, a group of heavily-armed terrorists entered the Westgate Shopping Mall in Nairobi, Kenya and started to murder men, women and children indiscriminately. Dominic Troulan, a security consultant working in Nairobi, was contacted by a friend who asked him to go to the incident to try and locate the friend’s wife and daughter.

On arrival at the Mall, Troulan contacted the family by telephone and entered the Mall. He was armed with only a pistol while the area was dominated by terrorists armed with grenades and machine guns. Nevertheless, Troulan managed to bring the two women to safety.

Realising that large numbers of civilians remained trapped while the terrorists continued to kill indiscriminately, Troulan re-entered the Mall. Over the course of several hours, he went into the building at least a dozen times and on each occasion managed to bring many innocent civilians to safety. He was fired on twice by the terrorists but managed to force them back. By now, Troulan was exhausted, dehydrated and at the limit of his mental capacity. He was about to stop when a distress call was received from a woman who was trapped, injured and bleeding. Once again, Troulan entered the Mall and brought the woman to safety.

Despite the strain of his efforts, it should be noted that Troulan had the presence of mind to realise that the terrorists could be hiding among the survivors. Troulan enlisted help and searched the civilians once he had led them to safety, thus ensuring that no terrorists were hiding in their midst.

1. (Back) Royal Warrant of 24 September 1940. London Gazette 31 January 1941. Issue 35060, page 622.

2. (Back) The Selection Committee for the George Cross, George Medal and British Empire Medal.

3. (Back) Detailed discussions about many of the recommendations and the standard required (and the equivalence of the awards to military decorations and medals) may be found in the various files of the Committee in the National Archives in category AIR/2.

4. (Back) In addition to the direct awards, in 1940 living recipients of the Empire Gallantry Medal were required to exchange their awards for the George Cross and in 1971 the Royal Warrants for the Albert Medal and Edward medal were revoked and their living recipients invited to exchange their awards. Notably, there were 182 awards of the Victoria Cross during the Second World War and 15 awards since then. This does not include four awards of the Victoria Cross for Australia and one award of the Victoria Cross for New Zealand.

5. (Back) London Gazette 16 June 2017. Issue 61969, page 11774.

April 10, 2017

Certificates for Gallantry Awarded by 10th (Irish), 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) Divisions

I have always been interested in the gallantry certificates of the three divisions raised in Ireland, about which there is very little information in a single source. I would be very grateful for contributions that support or contradict my comments.

In addition to the array of British and foreign decorations and medals awarded for gallantry during the First World War, many British Army divisions awarded certificates that recognised brave conduct brought to the notice of the divisional commander.

The certificates were produced in various formats and were of varying quality—some were of simple design and printed locally, others were more ornate and printed in the United Kingdom. The numbers awarded are impossible to determine. Many were instituted before the Military Medal came into being in March 1916 and, as the Military Medal became widely and more frequently awarded, these certificates became less common. Nonetheless, they continued to be awarded, in some divisions, and in various formats, throughout the war and they often preceded the award of a gallantry medal or decoration for the same act. Details of awards may be found in unit and formation war diaries and in local newspapers but these records are inconsistent.

All three of the divisions raised in Ireland produced such certificates.

10th (Irish) Division

The first such certificate to appear was that of 10th (Irish) Division, which landed at Suvla Bay in August 1915. It is not clear when the certificate was instituted. From the phrasing of the text, it appears that it was used to inform the recipient that their act was worthy of formal recognition, for which a recommendation had been submitted. It is evident from the example below—awarded to Lieutenant J H Beverland Royal Army Medical Corps, 32nd Field Ambulance—that not all such recommendations were successful.[1] The printed card was inscribed:

[image error]

10th (Irish) Division gallantry certificate (mock up-awaiting original image)

A later example from Salonika (albeit for earlier actions in Serbia) is typewritten, with a slightly altered inscription. In this case, the recipient was recommended for a Serbian award.[2]

[image error]

10th (Irish) Division Gallantry Certificate

It is not known if similar awards were made for bravery in Palestine before the Division was reorganised and ceased by to be ‘Irish’.

16th (Irish) Division

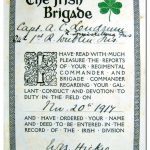

The ‘Parchment Certificate’ of 16th (Irish) Division was instituted by Major General Hickie in February 1916.[3] He announced it during his inspection of the battalions that had just returned from a period of instruction in the trenches alongside more experienced units. In one recorded instance on 17 February, after praising the performance of the 9th Royal Munster Fusiliers, he declared that whenever the name of a man came before him for having performed a meritorious deed he would have the fact recorded “…on a parchment sheet specially prepared in Dublin, so that a heritage worth preserving might be passed onto future generations to the glory of the Irish Brigades in France in 1916.”[4]

The first award was presented at a parade on 3 March 1916 to Corporal Patrick Hogan, ‘C’ Company, 8th Royal Munster Fusiliers, for his gallantry during a bombing attack on 21 February while the Battalion was attached to 33rd Division for instruction.[5] Corporal Hogan was killed in action on 29 June 1916 in another most gallant act ‘in an attempt to bring in a wounded man in daylight from no-man’s-land.’[6] [7]

It should be noted that the certificate—soon nicknamed the ‘Hickie Parchment’ or ‘Hickie’s Medal’— was awarded in large numbers and in addition to any other decorations or medals that might accrue, rather than instead of them.

The Parchment Certificate was produced in two versions. Although known as a ‘parchment’ both versions were produced on thick, high quality paper. The first was inscribed ‘The Irish Brigade’ in a pseudo-celtic script alongside a green shamrock. Underneath was space for the soldier’s name and unit and then, in plain, capitalised script, the text:

I HAVE READ WITH MUCH PLEASURE

THE REPORTS OF YOUR REGIMENTAL

COMMANDER AND BRIGADE COMMANDER

REGARDING YOUR GALLANT CONDUCT

AND DEVOTION TO DUTY IN THE

FIELD ON ___________________________

AND HAVE ORDERED YOUR NAME AND

DEED TO BE ENTERED IN THE RECORDS

OF THE IRISH DIVISION.

Note in the example below that the additional word ‘constant’ has been added in ink above the space before ‘devotion’.[8]

[image error]

16th (Irish) Division Parchment – Type 1

This first type was awarded from the institution of the Parchment in February 1916 to the early summer of 1917, including for bravery during the first actions at Loos in March and April 1916, at Guillemont and Ginchy in September 1916 and at Messines in June 1917.

From the autumn of 1916, the award of the Parchment was indicated by a hollow, dark green, felt diamond worn on the right upper sleeve of the uniform tunic.[9] It was known as the ‘Guinchy diamond’ and was first used in conjunction with the awards made for the fighting in September.

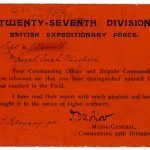

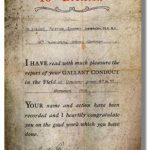

A second, more ornate version was awarded from the latter part of 1917, with earliest examples being known from the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August and the Battle of Cambrai; in the case of the latter for the actions on 20 November during the attack on Tunnel Trench. This second version was much the same as the first—it was 7 inches long by 4¾ inches wide—but it had an added meander border, at the top was inscribed the motto ‘Everywhere and Always Faithful’,[10] and the first letter of the main text was enlarged and decorated with an oak leaf design. This version was almost identical to that used by 29th Division from late-1917—it is not known which was the inspiration for the other.

[image error]

16th (Irish) Division Parchment – Type 2

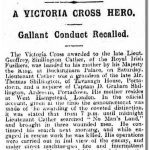

Almost destroyed during the German offensive in March 1918, 16th (Irish) Division returned to England and was reorganised and ceased to be an ‘Irish’ division. The gallantry certificate was retained but redesigned. Smaller and now titled ‘16th Division’ in red lettering between ornate scrolls, the soldiers name and unit were completed in ink beneath which the printed text read:

I HAVE read with much pleasure the

report of your GALLANT CONDUCT

in the Field ________________________

_____[Location and date of act]______

YOUR name and action have been

recorded and I heartily congratulate

you on the good work which you have

done.

[image error]

16th Division Parchment – Type 3

One soldier (probably uniquely) is known to have received all three versions of the Parchment. Private Ned Brierley earned his first award with 8th Royal Dublin Fusiliers at Ginchy on 9/10 September 1916; the second during the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1917 (actions which also earned him the Military Medal);[11] and the third, after having transferred to the Royal Engineers, with No. 3 Section, 16th Divisional Signal Company in support of 48th Infantry Brigade at Douvrin (coincidentally, not far from where Corporal Hogan had earned the very first award) when he repaired forward lines ‘under shellfire’ on 8 October and repaired a forward line to a trench mortar battery on 9 October.[12]

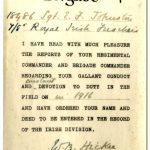

36th (Ulster) Division

The two certificates awarded by 36th (Ulster) Division were presented in a very different fashion to those for 16th (Irish Division). Somewhat surprisingly, given the impeccable organisation of 36th (Ulster) Division, the Certificate for Gallantry was not instituted until the spring of 1917. It was used primarily to reward men who had distinguished themselves during the attack on 1 July 1916 (and the preparatory period prior to it and in its aftermath). The first awards of the certificates were made to men of The Royal Irish Rifles dated 2 April 1917, nine months after the attack; they began to appear in newspapers at the end of the month.[13]

[image error]

36th (Ulster) Division Certificate – Type 1

This was the most ornate of any divisional certificate. Designed by the illustrator and painter Joseph William Carey and printed by Carey and Thompson Ltd., Royal Avenue, Belfast, the large certificate was replete with symbols linking the Division to the Ulster Volunteers and the Union with Great Britain. In front of a classical building stand two soldiers titled ‘An Ulster Volunteer 1800’ (the year of passage of the Acts of Union and the immediate aftermath of the defeat of the United Irishmen) and ‘An Ulster Volunteer 1914’; the latter dressed in wartime uniform and on his shoulder wearing the battle patch of 9th Royal Irish Rifles.[14] Between the columns on either end of the building are listed the units of 36th (Ulster) Division, with the infantry battalions, machine gun companies and trench mortar batteries on the left and divisional troops on the right, reflecting the Division’s organisation in late-1916/early-1917. On either side of the upper façade of the building is the Red Hand of Ulster within a shield and surmounted by a crown behind which is arranged the flags of the Allies. In the centre of the upper facade is a scroll split by the Royal Arms inscribed ‘For King, country and home’. Central to the certificate under the Division’s title, neatly and carefully hand written in ink, appear the number, rank and name of the soldier, his unit and the details of the act for which the certificate was awarded. At the very bottom of the certificate was inscribed ‘God save the King’.

The certificates appear to have been issued in batches by unit—for example, all the awards to 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers for 1 July 1916 are dated 25 August 1917.

Other actions in 1916 were also rewarded with retrospective certificates—for example, an award dated July 1917 for an act of gallantry near Messines on 4 October 1916.[15] There is no evidence that these certificates continued to be awarded immediately after actions later in 1917. There is evidence, however, that awards were made in retrospect from August 1918 and, indeed, after the war had ended, when they were presented to soldiers prior to demobilisation. For example: an award was made in August 1918 for gallantry during a raid just prior to the attack at Messines in June 1917[16] and an award was made in January 1919 for gallantry at Messines in August 1916.[17]

A second version of the certificate was produced in late-1918. In February 1918, 36th (Ulster) Division had undergone a significant reorganisation—six service battalions were disbanded and three regular Irish battalions joined the Division. In addition, men arrived from disbanded battalions in 16th (Irish) Division. Since late-1916 the Division had also received many English soldiers in reinforcement drafts. In consequence, the Division was an amalgam of Irish and English, Protestant and Roman Catholic, regular soldiers, special reservists, volunteers and conscripts. In May 1918, Major General Nugent left and was replaced by Major General C Coffin VC, DSO.

[image error]

36th (Ulster) Division Certificate – Type 2

The new certificate was very different to the first but it was also very elaborate. It was printed by Gale and Polden Ltd. in Aldershot—a company well known for its production of printed material of all kinds for the Army. The certificate, somewhat smaller than the original, is printed on stiff, cream paper in red, black and white. It has a cleverly designed, ornate border with symbols that reflect the make-up of the Division in 1918. In the top centre is the Red Hand of Ulster within a white shield, surrounded by a laurel wreath; in the bottom centre is a crowned, Irish-maiden harp surrounded by shamrock. In each of the four corners are the national plants of the nations of the United Kingdom—the shamrock, the leek, the thistle and the rose. Laurel leaves decorate the vertical borders and the top and bottom borders are inscribed ‘36th (Ulster) Division’ and ‘British Armies in France’, respectively. The centre of the certificate is given over to ornate script:

This Certificate is awarded to [name written in ink] for Gallantry and devotion to Duty displayed [location in ink] on [date in ink]

It is not known when the second type was instituted but, based on the available evidence, it may be concluded that these certificates were for actions in 1918 and were awarded in retrospect in a process that began after the war had ended and before demobilisation began in mid-January 1919 (possibly in conjunction with a process to issue some of the earlier type certificates for actions in 1916 and 1917). There is no record of posthumous awards being made. The earliest awards of this second type were for gallantry during the German offensive in March 1918. The earliest date on these certificates, which was in ink and always in the same style and hand as the details of the recipient, is 15 December 1918. Certificates were dated as late as February 1919. All were signed by Major General Coffin. There does not appear to be a correlation between the date of the action and the date on the certificate.

1. (Back) This award to Lieutenant John Herd Beverland, Royal Army Medical Corps, 32nd Field Ambulance, for gallantry at Gallipoli, dated 3 September 1915, is the only certificate of this type that I have seen.

2. (Back) This award to Major Michael John Furnell, Commanding Officer of 5th Royal Irish Fusiliers, was announced at a parade at Hortakoj Camp on 2 January 1916. The award was referred in the Battalion’s war diary as a ‘mention’. In addition to Major Furnell, Captain Edward Sidney Chawner Grune (attached from the Bedfordshire Regiment), Second Lieutenant Henry Erskine Sherrard, 5/11543 Sergeant Albert Buckler, and 5/12269 Corporal Robert Gibney were also ‘mentioned’; all except Sherrard subsequently received Serbian awards—see London Gazette 21 April 1917. Issue 30030, page 3285. Major Furnell had earned a similar certificate while serving as a Captain with 2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers in 82nd Brigade, 27th Division in Flanders in January 1915—see the gallery.

3. (Back) Major General William Bernard Hickie CB, General Officer Commanding 16th (Irish) Division, December 1915-February 1918. Later Major General Sir William Hickie KCB.

4. (Back) The account of the inspection and Hickie’s speech by the ‘Press Association’s Special Correspondent’ were syndicated to numerous newspapers, appearing on 19 February 1916. See, for example: ‘An Irish Battalion in France.’ (19 February 1916). The Belfast Newsletter. p 5.

5. (Back) Description of the award as ‘the first distinction conferred on a soldier of the Irish Brigade’: ‘Limerick Soldier Honoured’. (1 April 1916). The Weekly Freeman. p 5. The act is deduced from the Battalion war diary: The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO). (December 1915-November1916). War Diary, 8th Royal Munster Fusiliers. WO 95/1971/2

6. (Back) 8th War Diary Op. Cit.

7. (Back) 3682 Corporal Patrick Hogan; he has no known grave and is commemorated on the Loos Memorial, Panel 127.

8. (Back) Award to 18486 Sergeant Ernest F Johnston, 7th/8th Royal Irish Fusiliers, in 1916.

9. (Back) Wheeler-Holohan, V. (1920). Divisional and Other Signs. New York: Dutton. p 49.

10. (Back) The motto Semper et ubique Fidelis (Always and Everywhere Faithful) was bestowed on the Irish Brigade for its service to France by the Count de Provence (later Louis XVIII) in 1792. The motto of 16th (Irish) Division—Everywhere and Always Faithful—was adopted by Major General Hickie in December 1916, and in the Second World War was used by 38th (Irish) Brigade (Ubique et Semper Fidelis).

11. (Back) 20041 Private Edward Brierley, 8th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers. London Gazette 19 November 1917. Issue 30389, page 11963.

12. (Back) Earned as 313085 Sapper Edward Brierley, 16th Divisional Signal Company, Corps of Royal Engineers. See: TNA. PRO. (December 1915-May1919). 16th Divisional Signal Company War Dairy. WO 95/1966/1. His certificates may be found in The Royal Dublin Fusiliers Association Archive, Dublin City Library and Archive, 138-144 Pearse Street, Dublin.

13. (Back) See: ‘Certificates for Gallantry’. (30 April 1917). The Belfast News Letter. p 8—awards to 6915 Rifleman J Leckey, 16th Royal Irish Rifles, 18759 Sergeant James Shields, 14th Royal Irish Rifles, 19514 Corporal Wilfred Jonathan Gibson, 14th Royal Irish Rifles, and 16584 Rifleman William Heasley, 14th Royal Irish Rifles; all of whom appeared in a longer list the following day.

14. (Back) The battle patches were worn to distinguish between units. The inverted triangle was won by the units of 107th Brigade, a semi-circle was won by 108th Brigade and a rectangle by 109th Brigade. A complete depiction of these by Michael Chappell appeared in Military Illustrated in August 1991.

15. (Back) The award to 19117 Private Robert Harbinson, 10th Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. ‘…for great devotion to duty in the Spanbroek Sector as Stretcher Bearer on the night of 4th October, 1916. During enemy bombardment he rendered first aid to several men and dug out three men who were buried, being exposed to machine gun fire all the time.’ See: .

16. (Back) The award to 18397 Rifleman Robert Marks, 13th Royal Irish Rifles, ‘…for gallantry during a successful daylight raid on the enemy trenches near Wytschaete on 3rd June, 1916, when he went to the assistance of comrades in difficulty, helped to beat off the enemy, and returned with prisoners.’ See: ‘Ulster Division Certificate’. (21 August 1918). The Belfast News Letter. p 3.

17. (Back) The award to 43266 Lance Corporal William Harrison, 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, ‘…for his gallantry on patrol on 14 August, 1916, when four Germans were captured, and on 11 October, 1916, on which occasion he rescued two wounded men from the German wire.’ See: ‘News from Mid Derbyshire.’ (18 January 1919). The Courier. p 6.

April 1, 2017

Sacrifice – New Biographies Published

The Canadian Book of Remembrance showing the entry for Private Lawrence Manning

Three new biographies have been added to the Sacrifice project website:

Private Chester Covell Buck served briefly in England with 202nd (Sportsman’s) Battalion before being sent back to Canada unfit for further duty. He died in Ponoka Asylum Hospital, Alberta, on 7 December 1917 and was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery, Plymouth, Indiana.

Private Lawrence Eugene Manning served in France with 72nd Canadian Infantry Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders of Canada). Greatly affected by his experiences, he took his own life on 9 November 1919 and is buried in Salt Lake City Cemetery, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Second Lieutenant George Albert Ruffridge and Cadet Hugh Barker O’Leary of No. 80 Canadian Training Squadron were killed in a flying accident at Camp Bordon in Canada on 6 May 1918. Ruffridge was buried in Rosedale Cemetery, Montclair, New Jersey.

March 31, 2017

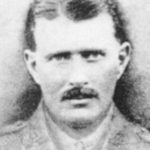

Cather VC

Geoffrey Cather’s Victoria Cross

One hundred years ago today at Buckingham Palace, King George V presented the Victoria Cross to the families of five recipients who had either died in the act or been killed since. Amongst them was Margaret Cather, the widowed mother of Lieutenant Geoffrey St. George Shillington Cather VC, the Adjutant of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, who had so gallantly died on 2 July 1916 while out rescuing men who had fallen in the attack at Hamel the previous day.[1] When she died in 1939 her effects were left to her other son, Dermot, who later presented the Victoria Cross to the Royal Irish Fusiliers museum, where it resides today.[2]

Geoffrey Cather’s Victoria Cross was announced in the London Gazette dated 9 September 1916:

For most conspicuous bravery. From 7 p.m. till midnight he searched ‘No Man’s. Land,’ and brought in three wounded men. Next morning at 8 a.m. he continued his; search, brought in another wounded man, and gave water to others, arranging for their rescue later. Finally, at 10.30 a.m., he took out water to another man, and was proceeding further on when he was himself killed. All this was carried out in full view of the enemy, and under direct machine gun fire and intermittent artillery fire. He set a splendid example of courage and self-sacrifice.

[image error]

Lieutenant Geoffrey St George Shillington Cather VC

Cather’s body was recovered on 3 July and buried at Hamel. His remains were not identified during the post-war concentration of graves and he is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

The other posthumous recipients honoured by the King that day were:

Major Cuthbert Bromley VC, 1st Battalion, The Lancashire Fusiliers. One of six recipients of the Victoria Cross earned by the 1st Battalion at Gallipoli during the landing at ‘W’ Beach on 25 April 1915. He was killed when the troopship HMT Royal Edward was sunk on 13 August 1915; Helles Memorial.[3]

Sergeant David Jones VC, 12th (Service) Battalion The King’s (Liverpool Regiment). At Guillemont on 3 September 1916, he took command of his platoon when the platoon commander was killed and held a captured position for two days and nights. He was killed in action on 7 October 1916; Bancourt British Cemetery.[4]

Commander Loftus William Jones VC, Royal Navy. The captain of HMS Shark, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Jutland but continued to fight his ship until it sank; Kviberg Cemetery.[5]

Major Stewart Walter Loudoun-Shand VC, 10th (Service) Battalion, The Yorkshire Regiment (Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own). Killed in action leading his men at Fricourt on 1 July 1916; Norfolk Cemetery, Becordel-Becourt.[6]

1. (Back) Robert Gabriel Cather (1859-4 January 1908) married Margaret Matilda Shillington (9 May 1865-7 November 1939) on 1887 at .

2. (Back) Dermot Patrick Cather (21 May 1894-26 March 1895); Captain, Royal Navy, served at the Battle of Jutland and throughout the First and Second World Wars.

3. (Back) London Gazette 15 March 1917.

4. (Back) London Gazette 26 October 1916.

5. (Back) London Gazette 15 September 1916.

6. (Back) London Gazette 9 September 1916.

March 14, 2017

Blacker’s Letters – ‘Finis’

When the last commanding officer of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers signed off the final page of the Battalion’s war diary on 9 June 1919 he did so with a Gallic flourish – ‘Finis’. That is the word that most readily comes to mind as I write this.

After 444 letters recording the thoughts and comments of Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Blacker, the identification of nearly 300 men and women to whom he referred, and many footnotes to explain events, the Blacker’s Letters project has ended. The project was made freely available to read via the project’s website and on social media.

Blacker’s Letters also contributed to the BBC project Voices 16, and I am very pleased that it has been web-archived by the National Library of Ireland and will be added to the web archive of the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland.

March 5, 2017

The Herald of Free Enterprise – 30th Anniversary

[image error]Today marks the 30th anniversary of the tragedy at Zeebrugge when the MV Herald of Free Enterprise, a roll-on roll-off ferry owned by Townsend Thoresen, capsized in shallow water as it left the harbour. On board was a crew of 80 and 459 passengers. In all, 193 passengers and crew perished in the incident.[1]

Inevitably, as seems to be the case in every such tragedy, others responded swiftly and with much courage to rescue the survivors and, over the coming days and months, to help treat the injured and traumatised passengers and crew. The selfless gallantry of crew-members, passengers and rescuers was rewarded with two George Medals, ten Queen’s Gallantry Medals, and two Queen’s Commendations for Brave Conduct. Less well known were awards in the Order of the British Empire to those who had assisted in the rescue and in helping the injured and bereaved; these included a number of honorary awards to Belgian citizens.

[image error]

Able Seaman ‘Ginge’ Fullen

One of the Royal Navy divers who took part in the rescue was Able Seaman Eamon ‘Ginge’ Fullen. When I was compiling For Exemplary Bravery, he wrote to me about his experience that day; it makes harrowing reading:

‘At the beginning of March we were alongside in Ostend very near to Zeebrugge. Most of the ship’s company had gone home on a long weekend back to England. I was on duty on board on 6th March, the night the ferry Herald of Free Enterprise went down. I was 19 years old and the only clearance diver on board. I had not seen one dead body before that night, by the end of it I was up to triple figures.

I remember getting driven and then flown over the capsized ferry and thinking ‘great, let’s get down there, this is it’. The diving dump was made and a few minutes later a call came that they needed a diver dressed in gear to climb down. Of the divers there was only one other British diver, an officer from my ship, Lieutenant Simon Bound, and from that moment we worked together. He dressed me in the diving set and weights, which is over 60 lbs. I had a dry-bag on and woolly bear (which keeps you warm, as you’re completely dry, or should be). I got positioned over the window, went on air, and proceeded to climb down. It was very awkward climbing over the lip with the heavy set and bad lighting. I then remember cutting quite a big gash in my dry-bag on a jagged piece of metal or glass and swearing profusely. The gash was in the leg and from then on I was wet and cold.

There were a lot of young people, young teenage girls, and I thought what a waste of a life. Something I remembered afterwards and never mentioned it to anyone—on that first stint retrieving the bodies and tying them on to be hoisted, we tied on a young lad of about seven or eight years. The other diver, who was German, said, ‘That’s awful, someone so young!’ and was clearly disturbed. I said a few words and tried to console him. I was swimming and retrieving the bodies but towards the end they were starting to sink. I had one body in my hand ready to tie on. I saw what looked like a small doll dressed in red clothes. I grabbed it and it was a little pretty blond haired girl, two years old or so, dressed in red—a red anorak coat, small red wellies on her feet and a little bobble hat still on her head. I lost my grip of her as the other body was getting hoisted. She floated away slightly and sank. I looked for her for a couple of minutes then forgot her and carried on with the job. I would have liked to have got that pretty little blond girl dressed all smartly in red, out of that cold dark place.

I was getting cold by now and I went for a cup of tea. We came back and helped load the bodies onto a tugboat. Rescuing the three lorry drivers made the whole night worthwhile. Other groups of divers were there now and I was very cold and nearly hypothermic. My suit was full of water and I was shaking with cold. They were going to send divers down the outside with the hope of hearing people maybe still alive. I was keen to dive and, even though I was extremely cold, I would have gone in again, although even then I remember saying I would not be able to do much. That would be the only thing now, with more experience, that I would not consider doing.

We returned to Ostend to find out our ship had sailed. We slept on a Dutch ship for a couple of hours and then returned to Zeebrugge to meet our ship when it came in. I don’t think I was brave or courageous, just somebody there who could do the job and think clearly.’[2]

[image error]

Gie Couwenbergh on his arrival back from the MV Herald of Free Enterprise

One of the Belgian divers involved in the rescue was Luitenant-ter-zee Gie Couwenbergh. He wrote:

‘I just happened to be at the right time at the right place. As duty commander of a NATO exercise I was responsible for the harbour of Zeebrugge for the night shift. I received a call telling me that a ferry had capsized just outside the fairway to Zeebrugge. I took it as part of our paper exercise but the caller repeated and added ‘This is a ‘NO PLAY’ message’. I could hardly believe it as there was a very calm sea, good visibility, cold, but no reason for a ferry to capsize. Anyway, I received more messages by phone and understood the scope of this incident. I had a message sent to all participating units and switched our office from ‘game’ to ‘real’ action. My car was outside the building and all my diving gear was still in it. I heard heli’s were underway from Koksijde SAR and I asked them to pick up three divers that I could contact in the Naval Base. Within minutes we were ready to be picked up and a few minutes later we were dropped on the Herald of Free Enterprise’s hull, still outside the water.

With the little light we had I could localize passengers and crew in the water some 15 metres below me, fighting for their lives. I went down a ladder we installed and started getting the people out. A team on the hull lifted them while I was attaching them in the water. This went on for a couple of hours. Weeks later we recovered the bodies from the wreck.’[3]

The gallantry awards were published in the London Gazette of 31 December 1987, ‘In recognition of bravery during the hazardous rescue operations after the capsize of m.v. ‘Herald of Free Enterprise’ off Zeebrugge on the night of 6th March 1987.’[4]

George Medal

Mr Andrew Clifford Parker (Passenger)

Head Waiter Michael Ian Skippen (Crewman—Posthumous)

Queen’s Gallantry Medal

Lieutenant Simon Nicholas Bound, Royal Navy (Rescue diver)

Seaman Leigh Cornelius (Crewman)

Luitenant-Ter-Zee 1ste Klas Guido Armand Couwenbergh, Belgian Navy (Rescue diver)

Luitenant-Ter-Zee 1ste Klas Alfons Maria Augustinus Cornelia Daems, Belgian Navy (Rescue diver)

Able Seaman Eamon Christopher McKinley Fullen, Royal Navy (Rescue diver)

Assistant Purser Stephen Robert Homewood (Crewman)

Mr Piet Lagast (Rescue diver)

Seaman William Sean Walker (Crewman)

Quartermaster Thomas Hume Wilson (Crewman)

Mr Dirk van Mullem (Rescue diver)

Queen’s Commendation for Brave Conduct

Chief Petty Officer Edward Gene Kerr (Rescue diver)

Chief Petty Officer Peter Frank Still (Rescue diver)

[image error]

Belgian Award Recients at Buckingham Palace, 8 March 1988

Other awards for meritorious service related to the incident, including awards to Belgian nationals, were made in the aftermath of the disaster, included:

Ordinary Officer of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire (OBE)

Commander John Birkett, Royal Navy[5]

Ordinary Member of the Military Division of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

Warrant Officer (Diver) Michael George Fellows DSC, BEM[6]

Ordinary Member of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

Chief Officer Malcolm Leonard Shakesby, MV Duke of Anglia[7]

Chief Welfare Officer Barbara Joyce Taylor, St. John and Red Cross Hospitals Welfare[8]

Honorary Knight Commander of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (KBE)

Mr Olivier Vanneste, Governor of West Flanders

Honorary Officer of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (OBE)

Captain Marc Claus, Director Belgian Pilotage Service

Honorary Member of the Civil Division of the Order of the British Empire (MBE)

Mr Rene van Havere, Zeebrugge Harbourmaster

Dr Daniel Dendooven, Cardiologist & Senior Doctor

Dr Geert Fransen, Cardiologist & Head Surgeon

Mrs Nadine de Gendt-Bruylandt, Nursing Director

Sister Agnes van Loo, Nursing Director

Secretary of State for Transport’s Award of Plate[9]

Mr Andre Pape, Master of the Tug Seahorse

Mr Henri Vermeersch, Master of the Tug Burgermeester van Damme

1. (Back) For a comprehensive description of the incident and details about the casualties and many of the survivors, see: Yardley, I. (2014). Ninety Seconds at Zeebrugge: The Herald of Free Enterprise Story. Stroud: The History Press.

2. (Back) Email Fullen to Metcalfe, 2013.

3. (Back) Email Couwenbergh to Metcalfe, 2013.

4. (Back) London Gazette 31 December 1987. Issue 51183, p 61.

5. (Back) London Gazette 31 December 1987. Issue 51171, p 5.

6. (Back) Ibid.

7. (Back) Ibid. p 15.

8. (Back) Ibid.

9. (Back) The tradition of awarding an inscribed silver plate to the master or senior officers of a ship involved in a rescue is long-standing. Other gifts, such as inscribed nautical instrument, gold watches and binoculars, or monetary payments to seamen were also common. Usually, they were presented by the Board of Trade or the Ministry of Transport (now the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills and the Deportment of Transport, respectively).

February 18, 2017

For Gallantry, Volume 1 – The Burma Gallantry Medal

The Burma Gallantry Medal, 1939-1945 Star, Burma Star and War Medal 1939-1945 awarded to Sepoy Nand Singh, 1st Battalion, The Burma Regiment. His award was for his gallantry during the attack on Aradura Spur on 29 May 1944 during the Battle of Kohima when he brought into action an abandoned machine gun and held off a heavy enemy counter-attack, during which he was wounded. (Photo © Dix Noonan Web.)

Following the partition of British Burma from British India in 1937, two new awards were introduced on 10 May 1940 the Order of Burma and the Burma Gallantry Medal.

The Burma Gallantry Medal was to be awarded to Governor’s Commissioned Officers, non-commissioned officers and other ranks of the Burma Army, Burma Frontier Force, Burma Military Police, Burma Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Force and Burma Auxiliary Air Force for ‘…an act of conspicuous gallantry’. This remained the case until 1945, when the Royal Warrant was revised to elevate to the award to the status of the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

This new book will begin a series of volumes that examine some of the United Kingdom’s lesser know gallantry awards. It will cover the status of Burma, its geography, people and armed forces prior to the Second World War and will examine the awards of the Burma Gallantry Medal in the context of the campaign in Burma from 1942 to 1945.

Publication date: 2017.

(For Gallantry, Volume 2 will lay out the awards of the Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry and For Gallantry, Volume 3 will examine the awards in the Order of the British Empire for Gallantry from 1958 to 1974.)

If you would like to contact Nick about the Burma Gallantry Medal project please use the contact form below.

[contact-form]