Nick Metcalfe's Blog, page 15

September 4, 2014

Family Service in the First World War – Part 1 William Neill

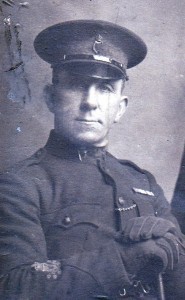

14577 Sergeant William Neill DCM

Sergeant William Neill DCM

It was the stories about my great-grandfather, William Neill, that led me to write Blacker’s Boys. I had been told that he had earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal at Ypres and I embarked on an attempt to separate family myth from fact. I have largely succeeded, with one exception—William Neill believed that he had been awarded a Bar to his Distinguished Conduct Medal but no record of that exists. During his post-war service with the Ulster Special Constabulary he wore a rosette on his ribbon bar, his obituary and his gravestone both state that he had a Bar, and my father’s memory of him was that his Bar was a source of great family pride. It is evident, however, that this second award was never made. Nevertheless, it must have been commonly agreed that he was entitled to it. He served in the USC alongside other former officers and soldiers of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers and it is hard to believe that a man of his considerable good reputation decided to award it to himself. How he came to believe that he had been awarded that Bar is now lost to history.

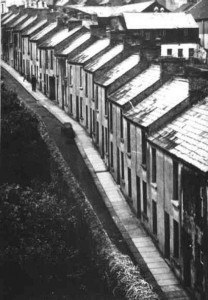

Taylor’s Court, Lurgan

William Neill was born on 1 June 1876 at Tullyherron, a townland in Donaghcloney parish near Waringstown.[1] He left school at 14 and began work with his father and siblings in a local mill.[2] The mills were the biggest employer in Lurgan; you can read more about linen in Northern Ireland here and about Lurgan here. On 27 August 1897, he married Emily Matthews, of Anne Street, Lurgan, at Shankill Parish Church.[3] They lived at Taylor’s Court. In the census of 1901 he described himself as a ‘yardhand’—for a period around this time he worked at the Lurgan Gas Light & Chemical Company at William Street. In 1911 he left Lurgan Gas Light—according to a letter of reference ‘to take a better job’—and went back to work in one of the town’s linen mills as a damask weaver, a highly skilled worker in this huge and important industry. In 1911 he, Emily, and their four young daughters were living at 28 James Street.[4] He and Emily would have one more child in 1913 and adopt another in 1922.

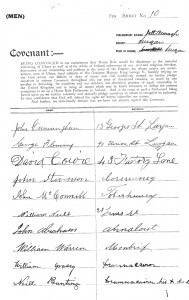

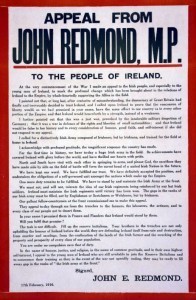

The political issue of the day was Home Rule—self-government exercised by an Irish Parliament in Dublin. There was considerable opposition in the northern, and largely Protestant, province of Ulster to any measure that would see an end to the Union and a shift in the balance of power and economic priorities away from Belfast. The signing of the Solemn League and Covenant, a pledge to ‘defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland’, was to become the focus of public opposition to the Home Rule Bill and 28 September was to be ‘Ulster Day’, when the Covenant would be signed across the province.[5]

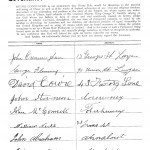

Ulster Covenant signed by William Neill

When the day came 237,368 men put their names to the Covenant, and 234,046 women signed the accompanying Declaration. Among them were the men and women of the Neill family, including William Neill, who signed at Lurgan Town Hall and Emily, who, with a number of other ladies from James Street, signed at Shankill Parochial Hall.[6]

William Neil also joined the Ulster Volunteer Force. Moves to arm a Unionist militia had begun as early as 1910 and by January 1913 the Ulster Unionist Council decided that the volunteers for such activities should be united into one body known as the Ulster Volunteer Force. The organisation of the force progressed quickly. Ulster was divided into fourteen divisions: the nine counties, Londonderry, and the four parliamentary constituencies of Belfast. Each of these was organised into a number of regiments and battalions—County Armagh, central to this story, raised five battalions. In addition to these, supporting units were formed to provide communications, transport, and medical facilities. Two units of light cavalry were raised—the Ballymena and Enniskillen Horse. William Neill joined ‘B’ Platoon in the 5th (Lurgan) Battalion.

The Home Rule Bill was passed on 25 May 1914. Fortunately, the day passed peacefully, as did the following 12 July when the Orange Order held its annual parades. But all was not well. Ireland was tense, and the men of the Ulster Volunteers paraded openly over the north of Ireland. Guns were landed for the Irish Volunteers—the nationalist counter to the Ulster Volunteer Force—on 26 July and the shooting of Irish nationalists by the British Army in Dublin that day inflamed the population. To many, war in Ireland seemed certain. Only the outbreak of war in Europe saved the situation.

It was evident that the Ulster Volunteer Force had the potential to become a formidable fighting force. After some discussion with Kitchener, Sir Edward Carson promised a division and on 3 September, at a meeting of the Ulster Unionist Council in Belfast, in a long and emotive speech Carson appealed to the men of the Ulster Volunteer Force: “Go and help to save your country and to save your Empire; go and win honour for Ulster and for Ireland.” For those members of the Ulster Volunteer Force responding to Carson’s call in Lurgan, recruiting began on 15 September. The official recruiting age was between nineteen and thirty-five (raised from thirty in late August) and William Neill, at thirty-seven years old, was over age. He was among the first to volunteer, however, and was duly attested.

Clandeboye Camp 1914

He enlisted into Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) and on Monday 21 September travelled with his friends and colleagues to Clandeboye near Newtownards, where the 2nd Brigade of the new Ulster Division was to be based (see the newspaper article in the photo gallery below). It was at Clandeboye that he was given the regimental number 14577. On 2 October, the County Armagh battalion was named the 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh).[7] His service follows that of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, with which he served for the duration of the war. He landed in France on 4 October 1915, initially as a Corporal in ‘C’ Company. Prior to the attack at Hamel on 1 July 1916 he joined the Battalion Transport and he became the Transport Sergeant on 24 August 1916. He served as the Transport Sergeant for the rest of the war—during the period holding the line at Messines from the autumn of 1916 through to the attack there in June 1917; at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1916, when the Battalion Transport Officer, Lieutenant James Stronge, was killed; at the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917; during the retreat from St Quentin in March 1918 and during the next phase of the German offensive at Ypres in April 1918; and in the Advance to Victory.

Lieutenant James Matthew Stronge

The death of James Stronge was a notable episode in William Neill’s life, an episode which would be talked about in the family for years to come. James Matthew Stronge was born on 10 January 1891 at Tynan Abbey, County Armagh, the son and heir of the 5th Baronet, Sir James Stronge. His family were staunch Unionists and Stronge was a member of the Ulster Volunteer Force. He enlisted into the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers on 14 September 1914 and was commissioned on 12 October. He was promoted to Lieutenant on 1 May 1915 and he served as the Battalion’s Transport Officer until he was killed in action at the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1917, aged 26. At the time of his death he had been married for a little over one month.

It is not known precisely where and when he was mortally wounded or killed but it was almost certainly on the route from Wieltje to the Battalion’s position, along Roeselarestraat, an old clinker brick road that was now a muddy, shell-torn lane, laid in part with corduroy track. It is known that Sergeant Neill called for volunteers to help him find Lieutenant Stronge—it may be surmised that he was actually present when he was mortally wounded or that knew that he had been badly wounded somewhere on the route to the Battalion’s forward position at Pommern Redoubt. It is not known whether he was dead when he was found but his body was brought to the rear by William Neill and four men. He was buried in Brandhoek New Military Cemetery Number 3. William Neill subsequently wrote to the Stronge family and described the events of that day, their son’s death and where he had been buried. In thanks, the family wrote back, sent him a silver framed photograph of James Stronge and invited him to visit. After the war William Neill visited Tynan Abbey on a number of occasions, at least once with my father.[8]

Sergeant William Neill was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in June 1918.[9] His citation does not indicate a specific act of gallantry:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has been with the battalion since its formation, and has rendered very valuable service as transport sergeant. His unfailing cheerfulness, coolness under fire and zealousness have been most marked.

The Battalion’s final actions involved the crossing of the Lys in October 1918 and its final day in action was 26 October. When the war ended the Battalion moved to Mouscron, where it remained until it was disbanded in June 1919. William Neill left Belgium in January 1919 for demobilisation and was at home in time to attend the ‘Welcome Home Banquet’ for the held at Portadown Town Hall on 30 January, at which the guests of honour were the prisoners of war repatriated in November and December 1918. He was transferred to the Class Z Reserve on 16 March 1919. In addition to the Distinguished Conduct Medal, he was awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal 1914-20 and the Victory Medal.

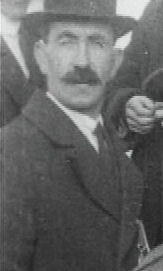

Sergeant William Neill DCM at the dedication of the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower, 21 November 1921.

When the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower was opened and dedicated on Saturday 19 November 1921, Sergeant William Neill DCM planted the tree on behalf of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers.[10] It is not often that one can identify relatives in news reels from this period, but this clip from British Pathé of the dedication of the Ulster Battlefield Memorial Tower, shows William Neill DCM in the final few seconds.

As if those who had suffered on the Western front had not had enough to contend with, they returned to Ireland at the dawn of a new era in Irish politics and conflict. Voting in the 1918 general election began on 14 December and the result was a shock to many. Sinn Féin candidates were elected in seventy-three constituencies. The Irish Unionist Party secured twenty-two seats, largely limited to Ulster, and the Irish Parliamentary Party won only six seats. After the election the Sinn Féin MPs chose to boycott the Westminster Parliament and formed the revolutionary parliament—Dáil Éireann. On the same day two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary guarding quarry explosives were ambushed and killed at Soloheadbeg in Tipperary by members of the Irish Volunteers. Thus began the Anglo-Irish War that would ultimately result in the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922 and the partition of Ireland.

The response by Unionists to the attacks of the Irish Republican Army in 1920 and 1921 was to form local militias across Ulster, based loosely on the pre-war Ulster Volunteer Force and manned by many former soldiers. In an effort to regulate these and to bolster the efforts of the police, the government agreed to the creation of the Ulster Special Constabulary as a reserve element of the Royal Irish Constabulary. This was achieved using existing legislation—the Special Constables (Ireland) Act, 1832. The Ulster Special Constabulary was divided into several categories, the most well known of which was the part-time ”B’ Specials’. There was also, however, a uniformed, regular cadre, the ‘A’ category. About half of the ”A’ Specials’ were assigned to duty in police barracks and acted as uniformed police, with the other half being formed into motorized platoons.

Head Constable William Neill DCM

Among those who joined the ‘A’ Specials was William Neill, who joined on 16 May 1922. He was allocated the number 7295 and was initially appointed as a platoon Sergeant. He was promoted to Head Constable at the end of the year and served in that capacity with 39th Platoon in Armagh. The ‘A’ and ‘C’ Specials (the latter were a non-uniformed reserve) were disbanded in March 1926 and on 17 April 1926, William Neill left the Ulster Special Constabulary. This was a difficult time but he found work with Lurgan Urban Council as a road construction foreman and his references from the officers of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers and the Ulster Special Constabulary are testament to his reputation.

At some time in this period the family moved to 40 Gilford Road, Lurgan and William Neill embraced the Elim Pentecostal Church; he became a lay-preacher. On Sunday 20 February 1955, as the family were waiting for a bus to take them to church, he felt unwell and decided not to go with them. He died at 9.30pm that night from a heart attack. He was 78 years old. He was buried at Lurgan New Cemetery on 23 February 1955.

Many of the images in the galley below have more detailed information. Thanks are due to my cousin, Gillian, for the images of William Neill’s medals and badges, the newspaper extracts and the photographs of him and his wife in later life.

","created_timestamp":"1312977226","copyright":"COPYRIGHT, 2009","focal_length":"10.1","iso":"100","shutter_speed":"0.016666666666667","title":"

","created_timestamp":"1312977226","copyright":"COPYRIGHT, 2009","focal_length":"10.1","iso":"100","shutter_speed":"0.016666666666667","title":"1. (Back) He was the sixth of the seven children of Gilbert Neill (born 1837), my great-great-grandfather, and Ellen Thompson (born 1833), who were married on 2 September 1864 in Magheralin Parish Church (The Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity, Magheralin). The other children were: Annie (born 1863), Thomas George (born 3 November 1865), Joseph (born 28 October 1867), Elizabeth Jane (born 21 August 1870), Moses (born 28 April 1873), and Hamilton (born 5 September 1884). William Neill was my father’s maternal grandfather.

2. (Back) Almost every member of my family in the generations up to my mother’s and father’s worked in the linen mills. On my father’s side they worked in the Lurgan area and on my mother’s side they worked in the mills in Hydepark, Mallusk in County Antrim.

3. (Back) The Church of Christ the Redeemer, Lurgan. This is the largest, non-cathedral Church of Ireland church in Ireland.

4. (Back) Elizabeth (known as Cissie) (born 12 August 1900), Olive (born 28 September 1902), Annie, my grandmother, (born 26 November 1907) and Marie (known as Miriam) (born 16 August 1910). A fifth child, Joseph (known as Joey), had been born on 22 September 1898 but had died on 20 March 1901. They would have one more child, May (Mary) (born 30 July 1913) and adopt another, Teddy (born 18 December 1922).

5. (Back) The Covenant was largely the work of James Craig MP, and was based on the Scottish Covenant of 1580/1581 and its successor covenants. Men signed the Covenant while women signed the accompanying Declaration.

The Covenant.

Being convinced in our consciousness that Home Rule would be disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive of our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship and perilous to the unity of the Empire; we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V, humbly relying on the God who our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn covenant throughout this our time of threatened calamity to stand by one another in defending for ourselves and our children our cherished position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a Parliament being forced upon us we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In such confidence that God will defend the right we hereto subscribe our names. And further, we individually declare that we have not already signed this Covenant.

The Declaration.

We, whose names are underwritten, women of Ulster, and loyal subjects of our gracious King, being firmly persuaded that Home Rule would be disastrous to our Country, desire to associate ourselves with the men of Ulster in their uncompromising opposition to the Home Rule Bill now before Parliament, whereby it is proposed to drive Ulster out of her cherished place in the Constitution of the United Kingdom, and to place her under the domination and control of a Parliament in Ireland. Praying that from this calamity God will save Ireland, we hereto subscribe our names.

6. (Back) The signatories of the Ulster Covenant may be found on the PRONI website.

7. (Back) When the battalions of 36th (Ulster) Division were named the County Armagh Battalion in 2nd Brigade was initially titled: 9th (Service) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) (County Armagh Volunteers). The suffix ‘…Volunteers’ was used for all of the battalions of the Ulster Division. The use of this suffix appeared once in the London Gazette—on 27 October 1914; the Gazette that appointed the first officers to the battalions of the Division—and never in the Army List. By November 1914 the word ‘Volunteers’ had been dropped from all of the battalion titles.

8. (Back) Lieutenant Stronge’s death meant that the title was inherited by Sir Walter Lockhart Stronge (6th Baronet), his father’s cousin, in 1928. The title passed then to the brother of the 6th Baronet in 1933 and in 1939 to the 8th Baronet, the Rt Hon Sir Charles Norman Lockhart Stronge. The 8th Baronet was born on 23 July 1884. A former officer in the Ulster Volunteer Force, Sir Norman Stronge had served as an officer in the 10th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers (Derry), with which he earned an MC and Croix de Guerre (Belgium) and was twice Mentioned in Despatches. By February 1918 he was Adjutant of that battalion and subsequently of the 15th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (North Belfast). He was wounded during the crossing of the Lys on 20 October 1918. He joined the Ulster Special Constabulary in 1921 as the Commandant of Coleraine District. He married in 1921 and moved to Tynan Abbey in 1939 when he succeeded to the Baronetcy. Elected MP for mid-Armagh from 1938 he became Speaker at Stormont in 1945 and served in that position until 1969. He became a Privy Councillor (Northern Ireland) 1946. He also served as HM Lieutenant County Armagh (1939), as a JP in County Londonderry and County Armagh, as High Sheriff of County Londonderry and as Honorary Colonel of the 5th Battalion, The Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria’s) from 1949-63. He was also President of the Northern Ireland Council of the Royal British Legion and Sovereign Grand Master of the Black Institution. He was made a Knight of the Order of St John of Jerusalem and a Commander of the Order of Leopold (Belgium), the latter in 1946. His son and heir was James Matthew Stronge. Born 21 June 1932, he was commissioned into the Grenadier Guards. On the resignation of his father, he was elected MP for mid-Armagh in 1969 and served until 1973. He was also a JP for County Armagh and a Reserve Constable in the Royal Ulster Constabulary. At 9.45pm on 21 January 1981 the family home, Tynan Abbey, was attacked by the Provisional IRA. 86 year-old Sir Norman Stronge and his 48 year-old son were both murdered in the library of the grand house, and the building, which had stood for 230 years, was destroyed by fire-bombs. Although fired upon by a patrol of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, the gunmen escaped. At the joint funeral Sir Norman’s coffin was borne by men of the 5th Battalion, The Royal Irish Rangers, and that of James Stronge by men of the RUC Reserve. They were buried in the family plot where Sir Norman’s wife had been laid to rest the previous year. The shell of Tynan Abbey stood empty until it was finally demolished in early 1999.

9. (Back) Award published in London Gazette 3 June 1918. Issue 30716, p 6481. Citation published in London Gazette 21 October 1918. Issue 30961, p 12361.

10. (Back) This ceremony is described in Blacker’s Boys Appendix 3; a revised and updated account will be the subject of a subsequent essay.

August 27, 2014

How Not to Self-Publish – The Totally Splendid Hotshot Author’s Survival Guide

Rosen Trevithick is a fabulous indie author who writes for adults (the ‘My Granny Writes Erotica’ series – very funny) and children (stuff about Trolls – also very funny). Her most recent book is about self-publishing. It is humorous and well-observed; it is a ‘must read’ for any aspiring or, indeed, established author thinking of self-publishing.

She very kindly let me appear as a guest on her blog about the book: How Not to Self-Publish – The Totally Splendid Hotshot Author’s Survival Guide

August 13, 2014

The Evolution of the Regular and Service Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918 – Part 1

Regimental Crest, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers)

During the course of my research when writing Blacker’s Boys, I was struck by how the homogeneous nature of the 9th (Service) Battalion changed as the war progressed. I also became aware that items of personal history—photographs, letters, diaries and so on—did not reside only in Northern Ireland but could be found elsewhere in the United Kingdom, in the home counties of the soldiers who joined the Battalion later in the war. In researching the history of the 7th and 8th (Service) Battalions, it has become clear that there is a paucity of primary source material immediately available in the museum in Armagh and I wondered if research into how the Battalions had evolved might point to a more likely source of information.

Additionally, one of the most common questions that I get asked by relatives of those who served with the Regiment is: “My (relative) joined the (name an English regiment). How did he end up in the Royal Irish Fusiliers?”

This essay will explain how each battalion of the Regiment evolved throughout the war years. I have divided it into five parts: Part 1 provides a short history of the Regiment from 1914 to 1918 and explains why there were insufficient Irish soldiers available to replace the casualties suffered in the major actions; Part 2 will examine the 1st and 2nd Battalions; Part 3 will cover the 5th, 6th, 5th/6th & 11th (Service) Battalions; Part 4 will examine the 7th, 8th & 7th/8th (Service) Battalions; and Part 5 will examine the 9th (Service) Battalion/9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion.[1] The reserve and garrison battalions will be covered in subsequent essays. I hope that this analysis will help others with their research and their understanding of the make-up of the Regiment during the First World War.

The Battalions of Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918

When war broke out in August 1914, the Royal Irish Fusiliers comprised two regular battalions, the 1st and 2nd, and two battalions of Special Reserve, the 3rd and 4th. By the end of 1914 the Regiment had raised five service battalions: the 5th and 6th in 31st Brigade, 10th (Irish) Division; the 7th and 8th in 49th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division and the 9th (County Armagh) in 108th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division. Meanwhile the 3rd (Reserve) and 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalions had been mobilised and were responsible for training new men and for holding trained soldiers, including the men of the Special Reserve, until they were required as reinforcements.

The 1st Battalion, in 10th Brigade, 4th Division (which initially had been held back in England) arrived in France to join the British Expeditionary Force on 23 August 1914, in time to fight in the Battles of Le Cateau, the Marne, the Aisne and at Armentieres. Having been recalled from India, the 2nd Battalion deployed to France in 82nd Brigade, 27th Division on 19 December 1914. Both battalions fought during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915.

The 5th and 6th Battalions sailed with the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in July 1915 and saw action at Gallipoli, suffering very heavy casualties. They were transferred to Salonika later in the year. The 2nd Battalion arrived in the Mediterranean in December 1915 and these three battalions saw action in Macedonia in 1916. In November that year the 5th and 6th were amalgamated to form the 5th/6th (Service) Battalion, which was joined in 31st Brigade by the 2nd Battalion. Both battalions fought in Allenby’s campaign in Palestine throughout 1917.

9th Royal Irish Fusiliers Battle Flash

The 9th (Service) Battalion (County Armagh) was next to deploy—it landed in France in early October 1915. It was followed by the 7th and 8th Battalions in February 1916. All three fought during the Battle of the Somme and suffered grievously—the 9th at Hamel on 1 July and the 7th and 8th at Guillemont and Ginchy in September. The 1st Battalion also took part in the attack on 1 July, north of Beaumont Hamel, and it was fortunate to have been relatively uncommitted before the attack foundered and suffered fewer casualties. In October 1916 the 7th and 8th were amalgamated to form the 7th/8th (Service) Battalion.

In September 1915, the 10th (Reserve) Battalion had been formed to support the 9th Battalion. At the same time, the 1st Garrison Battalion had been raised in Dublin and in February 1916 it sailed for India, where it remained until May 1917 when it joined the Burma Division. The 2nd Garrison Battalion was raised in Dublin in March 1916 and it deployed to Salonika in August. At the end of that year the 3rd (Reserve) Garrison Battalion was raised in Dublin as the reserve battalion for the 1st and 2nd Garrison Battalions.

In April and May 1917 the 1st Battalion took part in the Battle of Arras, taking heavy casualties. Both the 7th/8th and 9th Battalions fought at Messines in June 1917 and alongside each other during the Third Battle of Ypres on 16 August 1917, when they too suffered very heavy casualties. The major change to the structure of the Regiment in 1917 came in September when the 9th Battalion absorbed the disbanded 2nd North Irish Horse; it was retitled the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion. The 1st Battalion had joined the 9th in 36th (Ulster) Division in August 1917 and both fought during the Battle of Cambrai. The 7th/8th also fought at Cambrai, which would be its last major action.

This sketch by Corporal A V S Dunseith shows men of the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion. It is evident from their shamrock shoulder patches, the emblem of 16th (Irish) Division, that these were men who had joined from the disbanded 7th/8th Battalion.

When the infantry of the British Expeditionary Force was reorganised in February 1918, the 7th/8th Battalion was disbanded; the men being posted to the 1st and 9th Battalions. These two Battalions were mauled during the German offensive in March 1918 and again near Ypres in April 1918, being almost destroyed. Both were brought up to strength and took part in the Advance to Victory. The 5th/6th Battalion left Palestine for France in May 1918 and joined 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division in July. Meanwhile the 11th (Service) Battalion had been raised in England in June 1918. It joined the reconstituted 16th (Irish) Division in 48th Brigade but in August it was absorbed by the 5th/6th Battalion when it was transferred to 48th Brigade. The 5th/6th Battalion was the only Irish battalion in 16th (Irish) Division now and it remained there for the remainder of the war. The 2nd Battalion remained in Palestine, one of only three Irish battalions left in 10th (Irish) Division.

The reserve battalions were reorganised in April 1918. The 4th (Extra Reserve) and the 10th (Reserve) Battalion were absorbed by the 3rd and moved to England, where the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion remained for the rest of the war. At the end of the war the Regiment comprised:

1st Battalion – 108th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division

2nd Battalion – 31st Brigade, 10th (Irish) Division

3rd (Reserve) Battalion – West Riding Reserve Brigade, Territorial Force

5th/6th (Service) Battalion – 48th Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division

9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion – 108th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division

1st Garrison Battalion – Burma

2nd Garrison Battalion – Salonika

3rd (Reserve) Garrison Battalion – Tees Garrison

At the early stages of the war the 1st and 2nd Battalions had been brought up to strength and then sustained by recalled men of the Army Reserve and by some Special Reservists. Throughout the war the casualties suffered by all of the battalions during ‘routine’ operations in the line were replaced initially by Special Reservists and later by Irish recruits or by those soldiers of the Regiment who had recovered from wounds and sickness, all of whom were trained and held ready by the 3rd (Reserve), 4th (Extra Reserve), 10th (Reserve) and 3rd (Reserve) Garrison Battalions. The scale of the casualties suffered in the major actions—Gallipoli, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Messines, the Third Battle of Ypres, Cambrai, the German offensive in March and April 1918 and the Advance to Victory—were so severe, however, that the battalions could not be brought up to strength by Irish soldiers alone.

By the end of the war, all of the battalions of the Regiment had become, to a greater or lesser degree, an amalgam of Irishmen, men from elsewhere in the United Kingdom (and the Empire), regular soldiers, men of the Special Reserve and the Territorial Force, wartime volunteers and conscripts.[2] This, and the reduction in size of the Regiment to two regular and two service battalions, may be explained simply—recruiting in Ireland could not meet the demand for men as the war progressed.

Recruiting in Ireland

Following an initial surge of enthusiasm, recruiting levels dropped markedly across Ireland from mid-1915. It should be said that recruiting levels in the northern counties were more akin to those seen in Great Britain but, even there, the number of men who enlisted remained under the requirement. The problem was a significant one; it was the subject of numerous newspaper editorials and was frequently debated in Parliament.[3] Even at the early stages of the war when recruiting was at its height, men had to be found from outside Ireland.[4]

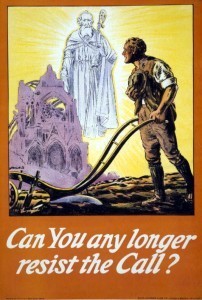

Those responsible for recruitment, at every level, did all that they could to increase the number of men coming forward—regiments sent men on recruiting marches around their traditional recruiting areas; newspaper articles and editorials exhorted men to enlist; notices and posters targeted potential recruits and those who could influence them; and much was made of Ireland standing for freedom and in opposition to tyranny.[5] It was not enough.[6]

Those responsible for recruitment, at every level, did all that they could to increase the number of men coming forward—regiments sent men on recruiting marches around their traditional recruiting areas; newspaper articles and editorials exhorted men to enlist; notices and posters targeted potential recruits and those who could influence them; and much was made of Ireland standing for freedom and in opposition to tyranny.[5] It was not enough.[6]

Six principal factors adversely influenced recruiting in Ireland.[7]

The demands of industry and agriculture. War-related or important industries employed a large number of men and some, for example ship building, precluded the widespread employment of women.[8] The war caused an initial downturn in the Irish based economy but, as it progressed, the linen industry refocused on war-related products, the Belfast shipyards became an important centre of the repair and conversion of war shipping, five national munitions factories were set up[9] (worked by men and women) and men and women were sent from Ireland to England to work in munitions factories there. Importantly, the demands on Irish agriculture increased as other sources of produce were closed. It should not be forgotten that the Irish famine, and its devastating impact, was within living memory for many, influencing men to stay and farm the land—their families’ livelihood.

The demands of industry and agriculture. War-related or important industries employed a large number of men and some, for example ship building, precluded the widespread employment of women.[8] The war caused an initial downturn in the Irish based economy but, as it progressed, the linen industry refocused on war-related products, the Belfast shipyards became an important centre of the repair and conversion of war shipping, five national munitions factories were set up[9] (worked by men and women) and men and women were sent from Ireland to England to work in munitions factories there. Importantly, the demands on Irish agriculture increased as other sources of produce were closed. It should not be forgotten that the Irish famine, and its devastating impact, was within living memory for many, influencing men to stay and farm the land—their families’ livelihood.

The scale of the casualties. The scale of the casualties suffered in the major actions became a noteworthy influence on recruitment across the United Kingdom. The first casualties from Ireland were notified within days of the deployment of the British Expeditionary Force. The first men of the Royal Irish Fusiliers to be killed in action were from the 1st Battalion—ten men were killed at Haucourt on 26 August 1914 in the early stages of the Battle of Le Cateau—and thereafter casualties mounted steadily. The major actions saw the greatest impact; the casualties from the Second Battle of Ypres, Gallipoli and, in particular, the Somme were considerable. It was not only the lists of those ‘killed in action’ that had an influence on the willingness of families to encourage their men-folk to volunteer, but the sight of the increasing number of men at home who had been grievously wounded.

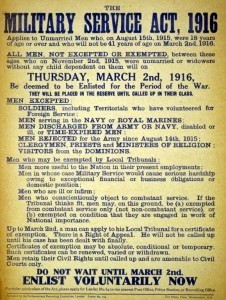

Home Rule and the rise of Irish nationalism. The Irish political scene—the issue of ‘Home Rule’—influenced almost every aspect of life in Ireland in the immediate pre-war years. Notwithstanding the support for military action against Germany voiced by John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party, Irish nationalists did not join the Army in the numbers (proportionally) seen in the northern Unionist population. The rise of more radical and militant Irish nationalism—particularly after the Easter Rising in 1916—increasingly, and adversely, influenced recruiting, particularly in southern counties. The politics of Home Rule influenced many aspects of recruiting in Ireland and shaped the Military Service Act, 1916. There was significant opposition to the imposition of conscription in 1918, with the proposal being opposed by Unionists and Nationalists alike.

Home Rule and the rise of Irish nationalism. The Irish political scene—the issue of ‘Home Rule’—influenced almost every aspect of life in Ireland in the immediate pre-war years. Notwithstanding the support for military action against Germany voiced by John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party, Irish nationalists did not join the Army in the numbers (proportionally) seen in the northern Unionist population. The rise of more radical and militant Irish nationalism—particularly after the Easter Rising in 1916—increasingly, and adversely, influenced recruiting, particularly in southern counties. The politics of Home Rule influenced many aspects of recruiting in Ireland and shaped the Military Service Act, 1916. There was significant opposition to the imposition of conscription in 1918, with the proposal being opposed by Unionists and Nationalists alike.

The influence of the Roman Catholic church. The Roman Catholic church was the most powerful single entity in the southern counties of Ireland. It was not united, however, in its support or opposition to the war effort. The plight of ‘Catholic Belgium’—and support for its protection and defence—and opposition to German militaristic expansion, sat contrary to the Church’s desire for peace. The call for peace had its greatest voice in the Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, the encyclical of Pope Benedict XV given on 1 November 1914. In addition, the position of many bishops and priests was as much about their politics as it was about their faith.[10] The attempt to impose conscription in Ireland in 1918 was vehemently opposed by the Roman Catholic church.[11]

The influence of the Roman Catholic church. The Roman Catholic church was the most powerful single entity in the southern counties of Ireland. It was not united, however, in its support or opposition to the war effort. The plight of ‘Catholic Belgium’—and support for its protection and defence—and opposition to German militaristic expansion, sat contrary to the Church’s desire for peace. The call for peace had its greatest voice in the Ad Beatissimi Apostolorum, the encyclical of Pope Benedict XV given on 1 November 1914. In addition, the position of many bishops and priests was as much about their politics as it was about their faith.[10] The attempt to impose conscription in Ireland in 1918 was vehemently opposed by the Roman Catholic church.[11]

The reorganisation of the reserve battalions. In April 1918 the reserve battalions of the Irish regiments underwent a major reorganisation.[12] They moved to England, were reduced in number and were re-brigaded. The reserve battalions of the Regiment will be the subject of another essay but, suffice it to say, this relocation and reorganisation did little to help increase the flow of Irish recruits to the battalions on the Western Front or in the Middle East when they were so desperately needed in the final year of the war.

No conscription. The reduction of willing volunteers seen across the rest of the United Kingdom resulted in a number of schemes to increase recruitment (and, importantly, the identification of men fit enough to serve) before the Military Service Act, 1916—conscription—was introduced.[13] None of these schemes were applied in Ireland and for myriad reasons, all of them political, the Military Service Act, 1916 did not apply to Ireland, or to Irishmen working in Great Britain who were not normally resident there. In April 1918, during the major German offensive in France and Flanders, the Act was amended to include Ireland but the level of opposition was such that no Irishmen were conscripted.

No conscription. The reduction of willing volunteers seen across the rest of the United Kingdom resulted in a number of schemes to increase recruitment (and, importantly, the identification of men fit enough to serve) before the Military Service Act, 1916—conscription—was introduced.[13] None of these schemes were applied in Ireland and for myriad reasons, all of them political, the Military Service Act, 1916 did not apply to Ireland, or to Irishmen working in Great Britain who were not normally resident there. In April 1918, during the major German offensive in France and Flanders, the Act was amended to include Ireland but the level of opposition was such that no Irishmen were conscripted.

The consequence of insufficient Irish soldiers to replace the casualties suffered by the battalions of the Royal Irish Fusiliers will be examined in the subsequent parts of this essay. Part 2—the 1st and 2nd Battalions—will be posted in the first week of September.

(Recruiting posters from the Library of Congress, all other images from the author’s collection.)

1. (Back) For those with a copy of Blacker’s Boys the material about the 9th (Service) Battalion/9th North Irish Horse) Battalion may be found in the introduction to Appendix 6.

2. (Back) More information about these different types of soldier may be found online in The Long, Long Trail.

3. (Back) A search of Hansard will reveal numerous questions and discussions on the level of recruitment in Ireland. See, here, for example:

4. (Back) Two examples: (a) Men from the Channel Islands were sent to Ireland and joined the Royal Irish Regiment, Royal Irish Fusiliers and Royal Irish Rifles in 16th (Irish) Division. (b) The north-east of England was a ripe recruiting ground in the early months of the war, particularly given that the coal mines were on a reduced working week. A number of regiments established recruiting offices in the region including The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, which began a successful recruiting drive there in December 1914. In order to balance numbers across 36th (Ulster) Division, a batch of these men were transferred to Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) on 30 June 1915 and joined the 9th Battalion.

5. (Back) Responsibility for recruiting lay with the Central Council for the Organisation of Recruiting in Ireland, which was created in 1914 and based at Great Brunswick Street in Dublin. It became the Department of Recruiting in Ireland in 1915 and the Irish Recruiting Council in 1918. Its principal roles were to produce guidance on how recruiting efforts were to be organised at county and local levels, (for example, in 1914 it published ‘Instructions for Voluntary Helpers’), and to organise the production of recruiting posters and patriotic literature. It also issued a certificate for enlistment for active service to all of the men recruited.

6. (Back) The number of Irishmen (i.e. those resident in Ireland) who volunteered during the course of the war is recorded as 134,202 men. This does not include men of the Army Reserve or Special Reserve mobilised in 1914. This figure is a little over 6% of the male population in 1914. The figure for English volunteers is 24%. Further analysis becomes difficult because of, for example, the emigration of men of recruiting age who had left Ireland in the years prior to the war, which was greater, proportionally, than for the rest of the United Kingdom.

7. (Back) Some of these were common to the rest of the United Kingdom, which also suffered a drop in recruits prior to the introduction of conscription

8. (Back) In Great Britain, men in these occupations were in two categories. ‘Badged’ men were in possession of a Badge Certificate issued by the Ministry of Munitions, the Admiralty or the War Office. They were issued with a brass badge indicating that they were ‘On War Service’. They were exempt from conscription. ‘Starred’ occupations (also known as ‘reserved occupations’, the more common term used during the Second World War) were those that were important to the war effort but the men in them had to apply to a Local Tribunal before 2 March 1916 for a ‘Certificate of Exemption’ in order to be exempt from conscription.

9. (Back) These were in Dublin (two—a National Shell Factory and a National Fuse Factory), at Bilberry in Waterford (cartridge cases), and a National Shell Factory in both Cork and Galway. Some commercial factories also had munitions contracts.

10. (Back) More on these factors may be found in the excellent MPhil thesis by J M Brennan: Irish Catholic Chaplains in the First World War.

11. (Back) Although individual clergy in other denominations opposed the war, the widespread opposition to involvement in the war effort voiced by the Roman Catholic church was not seen in the Church of Ireland or in the non-conformist churches.

12. (Back) The reserve battalions of the Irish regiments were never part of the re-organised Training Reserve formed from the reserve battalions of English, Scottish and Welsh regiments in September 1916.

13. (Back) See The Long, Long Trail: The Group Scheme and The Military Service Act, 1916.

July 28, 2014

Blacker’s Boys – New Updates Posted

Three new updates have been posted on the Blacker’s Boys website:

One of the new photographs: 41110 Private John Morrison (right) and his brother, Sergeant William James Morrison, a regular soldier who served with the 1st Battalion.

Update 16 – July 2014: Appendix 2 – Roll of Honour & Appendix 3 – Cemeteries & Memorials.

This amendment includes information on the new CWGC cemetery at Lidzbark Warminski, Poland, in which is commemorated one soldier of the Battalion who died there while held as a prisoner of war.

Update 17 – July 2014: Chapter 5 – The Roll of Officers.

This amendment provides new information about one officer and a new photograph of another.

Update 18 – July 2014: Appendix 6 – Roll of Warrant Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers & Other Ranks.

This update provides new information on a number of soldiers, including one who was previously unknown, and a number of new photographs.

All of these are free to read and download.

Thank you to all of those who have contributed to these updates. If anyone has any information that should be added to the history of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers, please get in touch.

July 27, 2014

The Antoni Paszkiewicz Project

Antoni Paszkiewicz

The Antoni Paszkiewicz project will examine the life and, in particular, the Second World War history of a young Polish man who was born in Vilno (now Vilnius, Lithuania) in 1921. During the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, he was arrested and imprisoned. Having been released to join ‘Ander’s Army’—the Polish Armed Forces in the East loyal to the Polish government-in-exile—he left Russia via Iran and Iraq in 1942. This army of Poles formed the basis of Polish II Corps, which fought in North Africa and Italy. Antoni Paszkiewicz subsequently joined the 1st (Polish) Independent Parachute Brigade. Following the war he settled in the United Kingdom.

This incredible story will be supported by a wealth of photographs that he took or bought as souvenirs on his travels, and other material, including his diary, provided by his family. It will take some time to examine all of the material, much of which is in Polish or Russian. I hope to have the first instalment published in autumn 2014.

Sunset over the Euphrates. One of many photographs taken by Antoni during his travels through Iraq in 1942.

This series of articles will eventually contribute to the Kresy-Siberia Virtual Museum.

For Gallantry, Volume 1 – The Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry

This is the first of two books projects that I am working on. The other is here.

For Gallantry, Volume 1 – The Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry

Following the successful introduction of the Colonial Police Long Service and Good Conduct Medal in 1934, an award to reward members of the Colonial Police Service for their meritorious service and gallantry was suggested, first in March 1935 and then again in November 1936, by Inspector General R G B Spicer CMG, MC of the Palestine Police Force. The Colonial Police Medal was instituted in 1938.

The Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry was awarded to ‘…those members of recognised Police Forces or of properly organised Fire Brigades in Our Colonies and its Territories…’. It became the Overseas Territories Police Medal in 2012 but for acts of gallantry it had been replaced de facto by the Queen’s Gallantry Medal in 1974.

This new book—a ‘prequel’ to For Exemplary Bravery, the history of the Queen’s Gallantry Medal—will describe in detail the debate around the institution of the Colonial Police Medal and it will examine the design of the medal and its varieties. Importantly it will provide histories of the various police forces across the British Empire and, later, the Commonwealth, whose members earned this medal for their gallantry in general policing duties and in the counter-insurgency campaigns in Palestine, Malaya, Kenya and Cyprus. At its heart will be a detailed register of all of the recipients of the Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry.

Publication date: mid-2016.

This Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry was awarded to British Sergeant Dennis Baily Richards, Palestine Police, in December 1947. Richards had served previously with the 15th/19th The King’s Royal Hussars. This group comprises: Colonial Police Medal for Gallantry; India General Service Medal 1908-35, with clasp ‘NORTH WEST FRONTIER 1930-31’; General Service Medal 1918-62, with clasps ‘PALESTINE’ and ‘PALESTINE 1945-48’. (Photo © Dix Noonan Web.)

(For Gallantry, Volume 2 will examine the awards in the Order of the British Empire for Gallantry from 1958 to 1974.)

If you would like to contact Nick about the Colonial Police Medal project please use the contact form below.

[contact-form]

From Hulluch to Tunnel Trench – the 7th and 8th (Service) Battalions, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918

This is the second of two books projects that I am working on. The other is here.

From Hulluch to Tunnel Trench – the 7th and 8th (Service) Battalions, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) 1914-1918

The 7th and 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers were raised as part of Kitchener’s second ‘New Army’ for service with 49 Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division. Recruited from counties Armagh, Cavan and Monaghan, with a contingent of men from the Royal Guernsey Militia, they arrived in France in early 1916.

The 7th and 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers were raised as part of Kitchener’s second ‘New Army’ for service with 49 Brigade, 16th (Irish) Division. Recruited from counties Armagh, Cavan and Monaghan, with a contingent of men from the Royal Guernsey Militia, they arrived in France in early 1916.

This new book, in the style of the well-received Blacker’s Boys, will describe the formation of the battalions, their first major action in France—the German gas attack at Hulluch near Loos in April 1916—to the attacks at Guillemont and Ginchy in September 1916; their amalgamation later that year; the successful attack at Messine in June 1916 and the horrific attack during the Battle of Langemarck on 16 August 1917; and the 7th/8th Battalion’s final action at Tunnel Trench during the Battle of Cambrai. The 7th/8th Battalion was disbanded in February 1918.

A section of map showing the scene of the attacks by the 7th and 8th Battalions at Guillemont & Ginchy in early September 1916 during the Battle of the Somme.

Like Blacker’s Boys, it is hoped that the text will be supported by detailed appendices covering casualties, rolls of the Battalions’ officers, warrant officers, NCOs and other ranks, and honours & awards.

The actions of these two fine Irish battalions have been almost forgotten due to the political and social landscape that developed in Ireland after the war. I wish to redress the balance.

If you would like to contact Nick about the 7th & 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers project, please use the contact form below. You might also like to visit the book’s Facebook page.

[contact-form]

July 24, 2014

The extraordinary adventures of ordinary girls: blog relaunch Socks for the Boys!

I have missed the unfolding story of Norah Hodgkinson who lived her teenage years through the Second World War. This new post summarises that which has unfolded so far and re-launches the blog. Alison, Norah’s great niece, reveals ‘how an ordinary diary – the sort of diary which usually garners little interest among historians and readers, a pocket diary which cannot be published as it is but which needs the stories coaxing out – is so much more than a list of everyday events.’ I’m looking forward to the next instalment.

From: The extraordinary adventures of ordinary girls: blog relaunch | Socks for the Boys!.

After a difficult  few months with very little time in which to write, I now have space ahead of me in which Norah’s story can unfold at the pace it requires.

few months with very little time in which to write, I now have space ahead of me in which Norah’s story can unfold at the pace it requires.

We are now well-acquainted with our feisty schoolgirl heroine. We have seen her at home – a loving daughter, a squabbling sister, living from the summer of 1938 in a brand new council house in a village in the English East Midlands. We have met most of her family: her gentle mother Milly, bellicose father Tom, her married sister Helen and little niece Jeannie, and older brothers Birdy and Frank. Read more.

The Heilsberg 39: The Dedication of the new Commonwealth War Cemetery at Lidzbark Warminski, Poland.

A soldier of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers has been commemorated in a new Commonwealth War Cemetery. A full report, video and slide show can be seen here: The Heilsberg 39.

Private John Ernest Partridge was born in London in 1899. He enlisted on 21 March 1917, aged 17, and was one of the large draft of men from The London Regiment that joined the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) on 6 April 1918. He was captured less than a week later on 12 April 1918 in the actions between Wulverghem and Kemmel.

Reported wounded, Private Partridge died of ‘general weakness’ at Heilsberg Prisoner of War Camp in East Prussia on 27 October 1918, aged 19. He was one of thirty-nine British soldiers who were buried in Heilsberg Prisoner of War Cemetery. Heilsberg, then a small town in East Prussia, is now Lidzbark Warmiński, Poland. The graves of these men, among a number of mass graves, could not be maintained and the men were commemorated on the Malbork Memorial, in Malbork Commonwealth War Cemetery. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission has now erected headstones in a new Commonwealth War Cemetery at Lidzbark Warmiński, which was dedicated on 16 May 2014.

President Obama, Flanders Field American Cemetery, and an American with 36th (Ulster) Division.

The recent visit by President Obama to Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial at Waregem in Belgium brought back memories of my own visit there a few years ago. The site of the cemetery is near where the US 91st Division attacked and captured the wooded area of Spitaals Bosschen. It is beautiful and it has a very different ‘feel’ to Commonwealth cemeteries. Well-spaced rows of white crosses surround the chapel, which stands in the centre of the six acre site. Inside the chapel, the altar and walls are marble and the furniture is of carved oak, stained to reflect the black altar. On either side are the Walls of the Missing, inscribed with the names of the 43 men who fell in Flanders and who sleep in unknown graves. Bodies of some of these men have been recovered since and identified; those names are marked with a rosette.

I was working on Blacker’s Boys, the history of the 9th (North Irish Horse) Battalion, Princes Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers), and, after months of research, I had identified that one of the Battalion’s officers was commemorated in the memorial chapel. The man I was looking for—Lieutenant Harold Sydney (Syd) Morgan, United States Army Medical Reserve Corps—was killed in action almost exactly 96 years ago.

Syd Morgan was born on 2 May 1890 at Winton, Pennsylvania to Welsh and English parents. He studied at Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California until 1912 (Phi Delta Theta) and at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, from which he graduated as a doctor in 1915. He practised at Bellview Hospital, New York. Following the entry of the United States into the war, he was commissioned as a Lieutenant on 9 August 1917 into the United States Army Medical Reserve Corps in New York. He arrived in France soon afterwards, posted first to United States Army Base Hospital Number 2 at Etretat before being posted to 36th (Ulster) Division in the British Expeditionary Force. This was a common practice; in order to provide the greatest experience to the medical officers of the American Expeditionary Force they were attached to British and Commonwealth hospitals and field ambulances, and as unit medical officers. The first American unit to arrive in France, in May 1917, was a base hospital and the first American casualty, in July 1917, was a medical officer. This article Yanks In The King’s Forces is worth reading and contains excellent photographs.

Morgan spent a short period with one of the Ulster Division’s field ambulances before joining the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers in 108th Brigade as the medical officer in February 1918. On 19 March he wrote to another American medical officer, with whom he had served before joining the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers:

As it happens, I am still with the worthy 9th, in reserve right now at Grand Seracourt (sic). Our tours in the line have been simple enough lately and casualties rare. It has been good sport, however, for the weather recently has been absolutely perfect, giving wonderful observation. I’ve seen plenty of Boche and have missed his machine-gun bullets successfully. One night the C.O. and I went all around the line about twelve o’clock, going out into the saps and wandering about in No-man’s Land. Incidentally a machine-gun turned near us and d___ near cut the grass between our legs. The Boche is quiet these days, however, and he hardly replies at all to the rather heavy strafing he gets night andd ay. One thing certain now is our guns are not afraid to speak. The best sight I have seen recently was watching the tremendous shell of a 12-inch howitzer flying off into space. It is very remarkable how one can see the shell for fully a minute or two from the moment it leaves the muzzle until it goes out of view.

The ‘Boche’ were not quiet for much longer. On 21 March 1918 the German offensive swept all before it and 36th (Ulster) Division fought a withdrawal action over a period of seven days from St Quentin to Erches. For his gallantry during this period Syd Morgan was awarded the Military Cross—one of 173 such awards to medical officers from the United States. His citation stated:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during the retirement from Grand Seraucourt on the morning of March 22nd. This officer was retiring behind the rearguard, and on approaching Artemps was told that some wounded were still lying in Grand Seraucourt. Although he knew that the enemy was already on the outskirts of the village he returned at once with some stretcher bearers and succeeded in bringing out the wounded. He thus at the commencement of the operations set a splendid example to his stretcher bearers of devotion and courage.

Having been withdrawn from the line on the night of 27 March, 108th Brigade was detached from the Ulster Division and ordered to a position south of Ypres near Wulverghem. During the second phase of the German offensive, the men of the 9th Royal Irish Fusiliers were again in the thick of the fighting. During the attacks and counter-attacks near Wulverghem on 12 April 1918 Morgan was tending to the wounded with two stretcher-bearers when he was hit on the leg. As he was being placed on a stretcher a shell killed him. He was buried nearby.

There is some evidence to indicate that his body was exhumed and taken to Flanders Field American Cemetery during the period of cemetery concentration after the war, but positive identification proved impossible. He is commemorated in the Flanders Fields Memorial Chapel and also on the City of San Diego and San Diego County Memorial Roll.