My Family in the First World War – Part 4: Robert Thompson

18/1141 Lance Corporal Robert Thompson

Robbie Thompson

My great-uncle Robbie was the eldest of the twelve children of Henry and Margaret Thompson, and the only one old enough to serve during the First World War.[1] He was born at Hyde Park, Mallusk in County Antrim on 25 December 1898 and enlisted, considerably underage, on 1 December 1915, a little less than a month short of his 17th birthday.

Robbie enlisted into The Royal Irish Rifles, the county regiment, intending to join the locally-raised 12th (Service) Battalion (Central Antrim), which was one of nine battalions of the Regiment in 36th (Ulster) Division.[2] By the time that he enlisted, the Ulster Division had completed its training and was in France, getting to grips with life in the trenches, and Robbie joined the 18th (Reserve) Battalion at Clandeboye near Newtownards, where he was allocated the regimental number 18/1141. The 18th (Reserve) Battalion had been formed in April 1915 from the depot companies of the 11th and 12th (Service) Battalions and had taken over the camp at Clandeboye, vacated when 108th Brigade moved to Seaford in Sussex, in July. It was here at Clandeboye that he completed his training.

It is not known when he arrived in France. Given the length of his training, the earliest that he would have travelled via England to a Base Depot in France was the summer of 1916—one of the reinforcements sent out to replace those lost when 36th (Ulster) Division had attacked at Thiepval and north of the River Ancre on 1 July. He was underage, however, and, if this was known, it is possible that he was held back until sometime in 1917, until after his 18th birthday.[3]

Rifleman Robert Thompson

Rifleman Thompson joined C Company, 15th (Service) Battalion, The Royal Irish Rifles (North Belfast) in 107th Brigade. Not knowing when he arrived in France, it is impossible to describe his experiences before March 1918. If he joined the Battalion in early 1917 he was fortunate indeed to survive the three major attacks by 36th (Ulster) Division that year: On 7 June at Messines the Battalion attacked in the second wave against the ‘Black Line’ and suffered 12 men killed and 93 wounded; on 16 August, during the Battle of Langemarck, 15th Royal Irish Rifles was in reserve and there were few casualties, although there had been heavy casualties in B Company caused by shellfire in the preparatory phases; during the Battle of Cambrai the Battalion was uncommitted until 22 November when it attacked the Hindenburg Support Line. This action continued until the evening of 24 November, often at close quarters against a determined enemy. The casualties were severe but are not enumerated in the Battalion’s war diary; 64 officers and men are known to have been killed in action.[4]

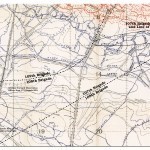

36th (Ulster) Division Sectors, March 1918

In 1918 Robbie Thompson found himself in a sector south-west of St Quentin near Grugies when 36th (Ulster) Division replaced French units there. By then he had been appointed a Lance Corporal in C Company. On 22 February there was a further reorganisation in the system of defence—from Blacker’s Boys:

‘…the manner in which defence was to be conducted was changed radically. Based on the German concept of ‘defence in depth’, the front was organised into three zones. The Forward Zone was essentially an outpost line in front of a line of supporting redoubts that would be held in enough strength to delay the enemy but from which its defenders would move back to the main line of defence — the Battle Zone — when attacked in strength. The Battle Zone, about two to three thousand yards back, comprised a series of well-built defence systems and redoubts that dominated the ground over which the enemy would attack. Reserves would also be available here to conduct local counter-attacks or to reinforce areas of particular threat. The third zone, the Corps Line, was to be set up in rear of the Battle Zone, but this was never achieved. The plan was a good one but, as would be proved, the troops were too thinly spread and insufficiently trained in it to make it effective.

In 36th (Ulster) Division’s area the ground was crossed by a series of ridges and valleys parallel to the front line. In the north, the outpost line lay on the same feature occupied by the enemy, and behind it lay the Grugies valley. This gave good cover from view and direct fire but provided a natural corridor along which the enemy could outflank the forward battalions. In addition, the front line of 14th (Light) Division on the right ran almost north-south, and the right flank was therefore weak and unlikely to hold if the villages of Urvillers and Essigny were captured. To the rear, the redoubts of the Forward Zone were on the next ridge, and farther back the redoubts of the Battle Zone lay on the low ridge along which ran the Essigny/Contescourt Road. The Ulster Division’s frontage was divided into three sectors, each allocated to a brigade. 108th Brigade was on the right, 107th Brigade held the centre and 109th Brigade was on the left.’

The men of 15th Royal Irish Rifles relieved 2nd Royal Irish Rifles in the Forward Zone on the night of 14/15 March. On 21 March the storm broke.

The exact dispositions of 15th Royal Irish Rifles and the detail of the action that took place on 21 March are difficult to determine—there is no official record of that period in the Battalion’s war diary.[5] The general dispositions may be deduced from the war diaries of Headquarters 107th Brigade, it’s two other battalions, the Division’s medium trench mortar batteries and 36th Battalion Machine Gun Corps (unfortunately it has not been possible to identify which company occupied each of the positions described below).

In the Forward Zone of 107th Brigade’s sector the ‘outpost line’ and the ‘line of resistance’ (see map) ran west-east, for 2,100 yards roughly along Auvergne Trench.[6] These lines, along the forward slope of a shallow ridge, were manned by two companies, with the four platoons of each company in strongpoints.[7] The role of the outpost line was to:

‘…keep the enemy’s front line, No-Man’s-Land and our own wire under constant observation by day and night from their own post to the next behind their own wire. All outposts will be wired round and alternative positions for each outpost prepared and used at different times to prevent the possibility of surprise by the enemy. The purpose of the outposts is to give warning of any enemy attack and to disorganise it in such a way as to give time to man the line of resistance. They are responsible that the post is held against small raiding parties. In the case of attack by a large force breaking through our line, they will fall back on their platoon in the line of resistance.’[8]

Positions Occupied by 15th Royal Irish Rifles on 21 March 1918

The Brigade Commander had identified four ‘points of tactical importance’. Two were in the line of resistance. The first of these was the higher ground south of Le Pire Aller on the left of the position.[9] The second was the plateau of slightly higher ground over the brigade boundary in 108th Brigade’s sector, which dominated his right flank. The platoons in the strongpoints along the line of resistance were ordered to hold ‘at all costs.’[10]

A third company was located on the reverse slop of the ridge, behind the line of resistance. It provided the ‘counter-attack company’, again with each of its platoons in strongpoints. The task of the counter-attack company ‘…in case of an enemy raid having effected a lodgement in our lines, is the immediate counter-attack by the two platoons nearest the lodgement.[11]

Behind the line of resistance was a shallow valley beyond which the ground rose again to the next line of defence. Here, one mile to the south-west of the line of resistance and 1,000 yards south of Grugies, was Racecourse Redoubt. The redoubt was centred on a fortified railway cutting—the third of the Brigade Commander’s points of tactical importance—and here were battalion headquarters, in a dugout in the cutting, and one company in the interlocking trenches of the fortified position around it.[12] The orders for those manning the redoubt were clear—they were to ‘…hold out to the last in case of a general attack in order to give time for the Battle Zone to be manned. It will on no account retire until orders are received from higher authority.’[13]

The defence of the Forward Zone was reinforced by 10 machine guns from B Company, 36th Battalion, Machine Gun Corps; two Stokes 3-inch mortars from 107th Trench Mortar Battery in the line of resistance; and two Newton 6-inch medium mortars from Y.36 Medium Trench Mortar Battery in Racecourse Redoubt.

From Blacker’s Boys:

Although there were some anticipatory British artillery barrages in the early hours, the night of 20/21 March was generally quiet. At 4.35am, however, the German offensive began with an intensive artillery barrage across the entire front. Employing guns and mortars firing high explosive, shrapnel and gas, it struck anything of importance, particularly communications, to a depth of two to four miles over a period of five hours. Between 6.00am and 9.40am the German infantry began its infiltration and advance.’

Lieutenant Colonel Claud George Cole-Hamilton CMG, DSO, KPM

The leading troops of the German 18th Army attacked 36th (Ulster) Division just after dawn. The enemy troops advanced in strength from the right flank along the valley behind the line of resistance—Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton,[14] the Commanding Officer of 15th Royal Irish Rifles wrote later; ‘…the front line was not attacked from the front at all, but from the rear.’[15] [16]

At 5.00am, after the order to ‘Man Battle Stations’ had been given, the Brigade Intelligence Officer, Lieutenant Cuming,[17] and the scouts had gone forward to Racecourse Redoubt. It was almost impossible for the companies and Battalion headquarters in the Forward Zone to convey what was happening because the heavy and well-planned artillery barrage had destroyed communications cable and telephone exchanges. Darkness at the early stages of the attack and the thick mist prevented visual signalling and the thick, foggy mist and the heavy shellfire compounded the problem for runners. Most importantly, communications between the forward battalions and their supporting artillery batteries were quickly lost.

At 8.00am Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton sent a message by a runner, who got it to brigade headquarters:

‘All communications forward and rear gone. Latest information from the line 6.45 a.m., received 7.45a.m. from Counter-attack Company says “Hostile artillery fire intense in this Sector. Casualties nil.” Very heavy shelling round redoubt. As far as known casualties 4 killed and one wounded. Fog still very thick.’[18]

At 8.20am Lieutenant Cuming sent more information, which was not received at brigade headquarters until 12.15pm, that described the enemy’s use of heavy gas and shell-fire in the morning and that the battalion headquarters of 15th Royal Irish Rifles had moved into the cutting in Racecourse Redoubt. Soon afterwards it was confirmed that the enemy was now attacking the Battle Zone. 15th Royal Irish Rifles had been cut off.

In his account about the attack at Racecourse Redoubt Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton wrote:

Captain John Hazelton Stewart DSO, MC

‘At about 9.30 a.m. all communications, both forward and to rear, had gone bust, so we knew nothing that was happening. At 10.15 a.m. our posts were driven in; at 10.30 a.m. fighting became heavy all round us—shortly after this, the left of the redoubt was overrun. This left us with only the portion of redoubt from Contescourt to Railway Cutting inclusive. The 2 platoons on the left had been all killed or captured also. From that or about 10.40 a.m. we had very close fighting, and were engaged by Flammenwerfer (4 attacks) knocked out finally by the Adjutant with Rifle Grenades, machine guns heavy and light, and Minenwerfers while the enemy infantry made several attacks over the open and along trenches with bombs. Every now and then, they seem to withdraw, and then we were heavily shelled – then the infantry would attack again.’[19] [20]

For his gallantry in the defence of the redoubt the Adjutant, Captain J H Stewart MC, was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Second Lieutenant Edmund De Wind VC

The Battalion’s final stand was made in this small section of trenches between the old French trench, Contescourt Alley, and the railway cutting, which proved, indeed, to be a point of tactical importance. One of the platoon commanders in the redoubt was Second Lieutenant Edmund de Wind.[21] For some time he held out in a section of the redoubt ‘practically single-handed’ and later, with two NCOs he ‘got out on top under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire, and cleared the enemy out of the trench’.[22] It was largely through his leadership and personal bravery that the redoubt was held for so long. He was killed in the afternoon and for his gallantry was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

That evening, at about 5.35pm, surrounded and with only 30 men unwounded, Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton took the decision to surrender. He wrote later:

‘It was a bitter moment, but I do not think we could have done more. The Officer in command of the Battalion who captured us told me he had taken over command as his C.O. had been killed, that a Battalion had been attacking us all day and a second had been sent up to help them or had been engaged for some time, so I think we did what we could to help the cause. I had only about 30 men left unwounded – only 60 all told were able to walk away and this included various oddments – Trench Mortar and Machine Gun Teams…’[23]

The casualties were severe and the Battalion was destroyed. Battalion headquarters, four rifle companies and the attached men of the trench mortar batteries and machine gun company had been killed or captured; many of those captured were also wounded; some of these wounded died soon after capture and were buried by the enemy. The war diary does not detail the total number of casualties but at least four officers and 70 other ranks were killed in action on 21 March or in the actions fought by the remnant of the Battalion before it was withdrawn from the line on the morning of 28 March.[24] Twenty-three men died subsequently in captivity.[25]

The war diary entry for 21/22 March recorded:

‘The diary now deals with the movements of the Battn details which consisted of Transport, personnel of Quartermaster’s Stores, personnel left out of action, other ranks arriving back from leave, from courses and from hospital together with a draft of some 100 O.R. which arrived to-day. The Battn itself was gone, killed, wounded and prisoners. Captain P.M. Miller, M.C. commanded the little party.’[26]

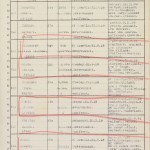

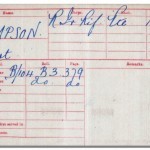

Friedrichsfeld POW Camp Register

Sometime during the fighting in the Forward Zone on 21 March, Lance Corporal Robbie Thompson was captured. There is no record of his journey into captivity but it is known that he was held at Friedrichsfeld bei Wesel prisoner of war camp north of Duisburg in the Rhineland. Friedrichsfeld was reputed to be among the better POW camps—you can read more about the camp here.

It was not until the prisoners had been repatriated in late 1918 that the full story about the gallantry of 15th Royal Irish Rifles at Racecourse Redoubt became known. The awards for gallantry for Edmund de Wind and those who had survived were published in May and October 1919 and in the ‘Prisoner of War Gazette’ in January 1920:

Victoria Cross[27]

Second Lieutenant Edmund de Wind (killed in action)

For most conspicuous bravery and self-sacrifice on the 21st March, 1918, at the Race Course Redoubt, near Grougie. For seven, hours he held this most important post, and though twice wounded and practically single-handed, he maintained his position until another section could be got to his help. On two occasions, with two N.C.O.s only, he got out on top under heavy machine-gun and rifle fire, and cleared the enemy out of the trench, killing many. He continued to repel attack after attack until he was mortally wounded and collapsed. His valour, self-sacrifice and example were of the highest order.

Bar to the Distinguished Service Order[28]

Lieutenant Colonel Claud George Cole-Hamilton CMG, DSO (Commanding Officer, captured)

Distinguished Service Order[29]

Captain John Hazelton Stewart MC (Adjutant, captured)

Bar to the Military Cross[30]

Captain James Edmund Smith Condon MC (OC D Company, captured)

Military Cross[31]

Lieutenant Robert Sprott (captured)

Sergeant Samuel Getgood DCM

Distinguished Conduct Medal[32]

15/1044 Sergeant Samuel Getgood (captured)

15/12170 Lance Corporal Charles Hubert Walker MM (captured & wounded)

Military Medal[33]

15/43219 Company Quartermaster Sergeant Harry Frank Beaconsfield Harris

17/878 Rifleman (Acting Lance Sergeant) John McClure Bill

41287 Lance Corporal Henry Collop

608180 Rifleman William Frank Davis

15357 Rifleman Thomas McClatchey

24033 Rifleman Frank James Price

10/16087 Rifleman Robert Watters

4434 Rifleman John Campbell (captured)[34]

Mention in Despatches[35]

Reverend William Frederick Morris MC, Army Chaplains Department (captured)

Private Robert Thompson, Ulster Home Guard

Robbie Thompson was repatriated to the United Kingdom in November 1918 and he returned to Hyde Park, where he went back to work in the local mill. On 12 June 1930 he married Emma McMullan Greer at Hyde Park Presbyterian Church. During the Second World War he served with the Ulster Home Guard. Robbie Thompson died at Hyde Park on 12 April 1969, aged 70, and is buried in Mallusk Cemetery.

Acknowledgement:

Nigel Henderson for the photographs from the Belfast Evening Telegraph.

1. (Back) Henry Thompson (born 21 July 1875) married Margaret White (born 20 September 1875) on 7 April 1898 at Carnmoney Parish Church. They had twelve children: Robert (born 25 December 1898), John (born 1 January 1900), Samuel, my grandfather, (born 28 May 1902), Ellen ‘Nellie’ (born 30 July 1903), Jane ‘Jeanie’ (born 15 September 1905), William (born 14 September 1907), Henry ‘Harry’ (born 29 June 1909), James (born 8 May 1911), Sarah Evelyn ‘Effie’ (born 2 July 1913), Margaret (born 23 June 1915), Emma (born 21 March 1918), and Eileen Robina ‘Ruby’ (born 12 December 1920).

2. (Back) The Royal Irish Rifles was the largest of the Irish infantry regiments; in addition to the two regular battalions, it raised 11 service battalions, a garrison battalion and nine reserve battalions. Of the nine battalions in 36th (Ulster) Division, four were raised in Belfast and formed 107th Brigade—8th (Service) Battalion (East Belfast), 9th (Service) Battalion (West Belfast), 10th (Service) Battalion (South Belfast) and 15th (Service) Battalion (North Belfast). Three were battalions of 108th Brigade—11th (Service) Battalion (South Antrim), 12th (Service) Battalion (Central Antrim), and 13th (Service) Battalion (1st County Down). One was in 109th Brigade—14th (Service) Battalion (Young Citizens); and the 16th (Service) Battalion (2nd County Down) (Pioneers) was the Division’s pioneer battalion.

3. (Back) Two reinforcement drafts, totalling 242 men, arrived in the Battalion on 7 February 1917. This is probably the earliest that he joined the Battalion.

4. (Back) This estimate is based on a study of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records. It is a low estimate and only includes those who were specifically identified as being from 15th Royal Irish Rifles. It does not include those who later ‘died of wounds’.

5. (Back) The period from 1 to 20 March is missing from the war diary. The subsequent entries, compiled by Lieutenant Andrew Newton-Anderson, the Assistant Adjutant, dealt with the Battalion’s ‘details’, i.e. those not present with the Battalion in the line.

6. (Back) The National Archives (TNA). Public Record Office (PRO) WO95/2502-1. 107th Brigade war diary. ‘From B.8.c.90.65 on the left to B.10.c.60.40 on the right.’ (Map 66cNW1.)

7. (Back) TNA. PRO. Op. Cit. The Brigade Defensive Scheme defined each type of defensive position:

Strong Point: ‘…a defended post organized for passive defense. It may or may not be wired all round. Its normal garrison is one platoon.’

Keep: ‘…a defended post wired all round, provided with rations water, ammunition and bombs for 48 hours and organized for protracted and passive defence. Its normal garrison is one platoon.’

Redoubt: ‘…a glorified keep whose normal garrison is one company.’

8. (Back) TNA. PRO. Op. Cit.

9. (Back) Le Pire Aller is now the junction of the D1 and D321 south-east of Gauchy.

10. (Back) TNA. PRO. Op. Cit.

11. (Back) Ibid.

12. (Back) Author’s note—I believe this to be D Company.

13. (Back) Ibid.

14. (Back) Lieutenant Colonel Claude George Cole-Hamilton (KStJ), CMG, DSO, KPM was born on 27 January 1869 at Killeshandra, County Cavan. He was commissioned into the 5th Battalion (Royal South Down Militia), The Royal Irish Rifles on 28 February 1900, promoted to Lieutenant on 18 October 1900 and to Captain on 31 March 1901. He volunteered for service in the South Africa War, where he commanded a mounted infantry company—he was mentioned in despatches (London Gazette 29 July 1902. Issue 27459, p 4851.) and made a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (London Gazette 31 October 1902 Issue 27490, p 6906.) ‘In recognition of services during the operations in South Africa’. On his return from South Africa he served with the 6th Battalion (Louth Militia) until it was disbanded in 1907. He then served with the 4th Battalion (Special Reserve) until he resigned his commission on 5 October 1912. On 9 February 1915 he was appointed Second-in-Command of 12th (Service) Battalion (Central Antrim) in 108th Brigade, 36th (Ulster) Division. He was promoted to Temporary Lieutenant Colonel on 3 August 1915, to command 8th Royal Irish Rifles in 107th Brigade and was appointed to command 15th Royal Irish Rifles on 9 September 1917. He was wounded in 1916 and in 1917 before being wounded, gassed and captured on 21 March 1918. For his wartime service he was thrice mentioned in despatches (London Gazette 25 May 1917. Issue 30093, p 5156; 24 May 1918. Issue 30701, p 6101; and 9 July 1919. Issue 31442, p 8708.), was made a Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (London Gazette 4 June 1917. Issue 30111, p 5459.), and earned a Bar to his DSO (London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1218.). He was repatriated from Germany on 14 December 1918. He subsequently served as the Chief Constable of Breconshire, for which he was awarded the King’s Police Medal (London Gazette 1 January 1936. Issue 34238, p 17.) He was appointed a Knight of the Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem in 1943 (London Gazette 21 June 1943. Issue 36069, p 2897.) He died on 6 January 1957, aged 87.

15. (Back) Public Record Office Northern Ireland (PRONI). D961 – Newton and Anderson papers. Lieutenant Colonel Cole-Hamilton’s account of the actions of 15th Royal Irish Rifles on 21 March 1918, written on 31 March 1918 while he was a prisoner of war.

16. (Back) The narrative in the war diary of the Divisional Trench Mortar Batteries also recorded that the ‘Centre Strong Point at Grugies was attacked in the rear…’ See TNA. PRO. WO95/2496-7.

17. (Back) Captain Arthur Eric MacMorrough Cuming MC, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers). He was awarded the Military Cross for his gallantry as 107th Brigade Intelligence Officer during the retreat from St Quentin. He was wounded on 21 October 1918 while serving with 1st Royal Irish Fusiliers and died of wounds on 26 October. He is buried in Terlincthun British Cemetery.

18. (Back) TNA. PRO. WO95/2502-1. Op. Cit.

19. (Back) PRONI Op. Cit.

20. (Back) Note: the left of the redoubt was to the north and north-west. Flammenwerfer – flamethrowers, Minenwerfer – trench mortars.

21. (Back) Second Lieutenant Edward de Wind was born on 11 December 1883 at Comber, County Down. He departed for Canada on 1 November 1911, where he worked in Edmonton for the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce. He enlisted into the Militia and served briefly with The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, before enlisting for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force on 16 November 1914. He served with the 31st Battalion, Canadian Infantry in France from September 1915 before joining an officer cadet battalion in April 1917; he was commissioned into The Royal Irish Rifles on 26 September 1917. He joined 15th Royal Irish Rifles as a platoon commander in late-1917. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Pozières Memorial. He is also commemorated on Comber War Memorial; his name is carved on a stone at the foot of a pillar at the west front of St Anne’s Cathedral in Belfast; he is named on two plaques in St Mary’s Parish Church, Comber; De Wind Drive, Comber is named after him as is Mount de Wind at the head of the Little Berland River, Willmore Park, Alberta. An Ulster History Circle Blue Plaque was unveiled in Comber in 2007.

22. (Back) Author’s note—I believe the NCOs were Sergeant S Getgood and Lance Corporal C H Walker MM.

23. (Back) PRONI Op. Cit.

24. (Back) This estimate is based on a study of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission records and I believe it to be accurate but it does not include those of the remnant of the Battalion that escaped on 21 March 1918 and who may have been wounded later and ‘died of wounds’ in hospitals in France or the United Kingdom.

25. (Back) Captured on 21 March 1918:

903 Rifleman William Agnew, died on 5 August 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

17/147 Rifleman William Walter Browne, died on 21 June 1918. Sarralbe Military Cemetery.

44818 Rifleman William Burrell, died on 21 November 1918. Selestat (Schlestadt) Communal Cemetery.

8/12665 Lance Corporal Ernest Edward Chubb, died on 12 April 1918. Niederzwehren Cemetery.

14/6615 Rifleman James Dooley, died on 28 June 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

12795 Rifleman Alexander Gillespie, died on 6 June 1918. Ham British Cemetery.

18/422 Lance Serjeant James Glenholmes, died on 20 September 1918. Niederzwehren Cemetery.

9/2635 Corporal Samuel Gribben, died on 26 October 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

44870 Rifleman Victor Ralph Howkins, died on 28 July 1918. Sarralbe Military Cemetery.

10/4311 Rifleman William McCullough, died on 1 May 1918. Cologne Southern Cemetery.

17/2247 Rifleman Ashley Albert Milne, died on 19 July 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

15656 Lance Corporal William Andrew Murdock, died on 20 July 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

43541 Rifleman William Thomas Page, died on 16 May 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

41200 Rifleman William Gregor Pigott, died on 21 September 1918. Veldwezelt Communal Cemetery.

13457 Rifleman Joseph Roy, died on 25 June 1918. Sarralbe Military Cemetery.

907 Rifleman Kennedy Scott, died on 6 June 1918. Roye New British Cemetery.

44360 Rifleman Lionel George Short, died on 31 May 1918. Avesnes-Sur-Helpe Communal Cemetery.

20/86 Rifleman Christopher Simpson, died on 24 October 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

13678 Serjeant Robert Swann, died on 12 April 1918. Sains-Du-Nord Communal Cemetery.

9/44895 Rifleman George Daniel Taylor, died on 22 June 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

15/3494 Rifleman George Tully, died on 25 August 1918. Hautmont Communal Cemetery.

Captured on 23 March 1918:

S/11695 Rifleman Archibald Larmour, died on 6 June 1918. Ham British Cemetery.

Captured on 27 March 1918:

47120 Rifleman Harry Treloggen, died on 1 July 1918. Berlin South-Western Cemetery.

26. (Back) TNA. PRO. WO95/2502-1. Op. Cit.

27. (Back) London Gazette 15 May 1919. Issue 31340, p 6084.

28. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1218.

29. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1218. (His first Military Cross had been awarded for his gallantry in 1917. London Gazette 1 January 1918. Issue 30450, p 47.

30. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1218. (His first Military Cross had been awarded for his gallantry as Officer Commanding D Company during the Battle of Cambrai. London Gazette 22 July 1918. Issue 13292, p 2533.)

31. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1220.

32. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1221.

33. (Back) London Gazette 20 October 1919. Issue 31608, p 12874.

34. (Back) London Gazette 11 February 1920. Issue 31775, p 1784.

35. (Back) London Gazette 30 January 1920. Issue 31759, p 1224.