Karen Brooks's Blog, page 9

August 11, 2013

Book Review: The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Rachel Joyce

I don’t know quite why I picked up this book. I think at first both the title and the cover really appealed but it was the blurb that sold me. Once I started, I couldn’t put it down. It’s one of those books that within a few lines you know you are going to love.

This is the tale of Harold Fry, recently retired and seemingly waiting for his life to be over. Each day is much like the last as he and his wife, Maureen (who you initially dislike) simply co-exist, going through the motions and habits by which they’ve survived the last couple of decades. Strangers in a not so strange land. That is, until one day Harold receives a letter that changes his life.

Learning that an old friend, Queenie Hennessy, is dying of cancer, Harold writes back to her, uncertain what to say or how, but making a fairly ordinary attempt. Leaving the house to pos t it, he suddenly becomes aware of the world around him, not in an epiphanic kind of way, just a gradual unfolding that is calm but no less wondrous for this. Deciding he’s enjoying walking, the sounds, sighs and smells, he doesn’t post the letter at the first post box, but walks to the next, wanting to prolong the experience, then the next and so on until he makes a decision: bugger posting the letter, he will walk to Queenie who is in palliative care over 600 miles away and express the sentiments he struggled to write in person.

t it, he suddenly becomes aware of the world around him, not in an epiphanic kind of way, just a gradual unfolding that is calm but no less wondrous for this. Deciding he’s enjoying walking, the sounds, sighs and smells, he doesn’t post the letter at the first post box, but walks to the next, wanting to prolong the experience, then the next and so on until he makes a decision: bugger posting the letter, he will walk to Queenie who is in palliative care over 600 miles away and express the sentiments he struggled to write in person.

And so, without fanfare or warning or preparation, Harold’s pilgrimage begins. Each shuffle, step, bunion, blister, meal, shelter, and companion, heralds a type of transformation or awakening, but also a reaffirming. But it’s who Harold meets along the way, the manner in which his journey is both understood and misrepresented by various people, that provides another kind of trial, a rest of endurance for Harold – not all of which he passes.

Written mainly from Harold’s point of view, we are also given access to Maureen’s perspective of her husband’s perambulations and the attention they receive and the impact all of this has on her. Absence doesn’t make the heart grow fonder so much as as alter, reignite and reconsider.

Distance from home and from his wife of many, many years allows Harold to reflect upon and view his life, past and current, differently – it gives him perspective and more. Likewise for his wife and thus the reader begins to understand how and why Harold came to be who and where he is and why his pilgrimage is not only a journey to find and say goodbye to an old friend, but himself.

Poetically told, incredibly moving, The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry is like a modern fable of disconnection and reconnection, aging, youth, the power of the media, love, friendship and self-discovery. Funny at times, capable of biting satire and stirring insights into the human condition, this is a marvellous novel that, like a few I have read lately, is original and lingers in the heart and mind long after the last page.

Simply lovely.

Book Review: The Summer That Never Was by Peter Robinson

Reading one of Peter Robinson’s Inspector Banks books is like wearing a pair of comfortable shoes or slippers – it feels good, comfortable, and is always reliable in terms of character, plot and pacing. So it is with The Summer That Never Was, a story that allows regular readers of the series a rare insight into Bank’s childhood and adolescence and the forces and pe oplethat shaped him.

oplethat shaped him.

One of the most significant of these was the mysterious disappearance of his close friend, Graham Marshall, who at fifteen years of age, while in the middle of his newspaper run, vanished and was never found. The impact of this on Banks and the gang he mixed with is profound. When bones are discovered nearby over 25 years later, and are identified as Graham’s, Banks cuts short his Greek isle idyll to not only bury his friend and to a degree, past, but uncover who killed his mate and, more importantly, why. But the case is not in his jurisdiction, not that this prevents Banks getting involved. When reputations begin to crumble and egos clash, and Banks discovers links to some of the biggest names in crime, he also understands that this isn’t just about the murder of a young man years before, but something deeper, darker and, as events unfold, more deadly as well.

Parallel to this case is one Annie Cabot is in charge of – the kidnapping and ransom of a minor sport’s celebrity’s step-son. Suspicious from the beginning, Annie fails to follow rules and thus opens the door for tragedy to step in… But is it Annie’s fault? Or is something more sinister operating here as well?

A page-turner par excellence, The Summer That Never Was is a trip down a Banks kind of memory lane, nostalgia tinged with ever-present danger reminding readers that the past can return and in ways that make its presence felt.

A terrific read. As usual.

Book Review: The Impossible Lives of Greta Wells by Andrew Sean Greer

I bought this book after it came up as a recommendation on Amazon. Having not long finished Life After Life by Kate Atkinson, the blurb and reviews (which linked it to Atkinson’s work and The Time Traveller’s Wife, which I also loved) sealed the deal for me. I’d never heard of the author, Andrew Sean Greer, but after reading Greta Wells story, I will be se eking out his other novels… But for the moment, I want to savour this one.

eking out his other novels… But for the moment, I want to savour this one.

This is a simply lovely, haunting book that tells the story of Greta Wells, a young woman in New York in 1985 whose beloved twin brother, Felix, is dying of the scourge of the 1980s on, AIDS. Tha

t is never articulated, but it is evident. Greta lives with her doctor partner, Nathan, and her eccentric aunt, Rita, lives downstairs. Grieving for her brother, she

is sent to a specialist who recommends she has ECT and so she does and the impossible happens – Greta is flung into not one other version of her life, but two – 1919 and 1941.

In these two other periods, the dead come back to life, possibilities are within reach and tragedy can yet unfold. Segueing between three lives (she returns to the novel’s present as well) and maintaining awareness of all three, Greta learns that perhaps she can become the woman she always thought she could be… Only, she discovers, who you are is also contingent on the time you’re born in and the choices available to you and though Greta understands the choices she and her other selves should make, never mind her brother and other characters, life isn’t that simple…especially not when a war has just concluded, another is unresolved and where a plague strikes down those you love.

I can see why this book has been compared to Atkinson and TTTW, it shares some of the tropes and themes but, Greer himself uses Alice in Wonderland, Dorothy and Neverland as analogies and there is a sense in which these are far more apt. There is something both mythical and magical (as well as tragic and triumphant) about Greta’s lives. She is like Alice down the rabbit hole or consuming food and drink that alters her perspective. She is Dorothy, whisked away from certainty and the known to the unfamiliar and dangerously marvellous. While she time travels and thus carries with her knowledge and awareness of the future that can be earth-shattering and life changing in the macrocosmic sense, this story isn’t concerned with that. On the contrary, Greta cares only for the way larger issues (war, sexuality, disease, prejudice, ethnicity,love, fidelity, truth) impacts upon those she loves and her immediate lives – the microcosmic – and, in that sense, there is a veracity to this book despite its fantastical premise and the massive suspension of disbelief the author requires of the reader. It is one we happily make because the characters and their story – which is personal, yes, but also ripples outwards to envelop us all – are worth investing in and their concerns are that which we all ponder and try to realize in varying degrees.

Written in lilting, lovely prose, the philosophical musings of Greta touch on eternal questions of love and life and purpose. What do we deserve? Are we all entitled to happiness? Is context everything? Can we alter these things and should we even if we can?

This is a book that lingers in the heart and soul long after you put it down. So glad I read it and I recommend it to anyone who enjoys a damn fine and meaningful read. I didn’t want it to finish.

August 8, 2013

Book Review: Watching You by Michael Robotham

I w as so thrilled when Michael Robotham’s latest book, Watching You, the seventh in the Joseph O’Loughlin series downloaded on my Kindle. The only thing that disappointed me about this fast-paced, edge of your seat, nail-biting and every other cliché I can conjure instalment, was that I finished it in one sitting. I simply could not put it down. Damn. Damn. Damn.

as so thrilled when Michael Robotham’s latest book, Watching You, the seventh in the Joseph O’Loughlin series downloaded on my Kindle. The only thing that disappointed me about this fast-paced, edge of your seat, nail-biting and every other cliché I can conjure instalment, was that I finished it in one sitting. I simply could not put it down. Damn. Damn. Damn.

The novel begins with Marnie Logan, a young, married woman with two children whose husband, Daniel, disappeared without a trace over a year ago. Grieving for her husband, Marnie (who has her own demons past and present to deal with) tries to cope. Depressed, she’s been seeing her neighbour, Joe O’Loughlin on a professional basis for quite some time. What she hasn’t revealed to him is that throughout most of her life she’s had the uncomfortable sensation of being watched – it’s nothing tangible, just a flash in the corner of her eye, a light touch, like cobwebs, upon her shoulders; the uneasy sensation that nothing you do is private.

It’s not until she finds an incomplete birthday present that Daniel was working on for her birthday, a scrapbook of memories, DVD of interviews and images of people from her past, that things begin to go awry. Far from being the celebration Daniel intended, there are people he interviews who are either terrified of Marine and what she did to them, or curse her to an early grave. When Marnie, confused and upset, turns to Joe to explain what’s going on, he turns to his buddy, Vincent Ruiz for help.

Just in time, it seems, for Marnie is going to need some friends, particularly when a shady character she’s involved with turns up dead and the last number he called and the last person he’s known to have seen, was her.

Denying all knowledge and proclaiming her innocence, everyone can see she is lying, but what is Marnie hiding? When her history starts to unfold, not even Joe is prepared for what he discovers…

Yet again, Robotham has written a tautly paced, beautifully written novel that is full of surprises, even when you think you’ve predicted the outcome. The characters are expertly drawn and so believable. You invest in each and every one – whether it’s a cynical cop, a concerned psychiatrist, Marnie or her terrific kids. And, of course, there is always Joe and Vincent – their dialogue snaps, their observations (about crime scenes, individuals, the world) crackle. Humour laces the novel despite its heavy themes as does the importance of family and trust. But this novel is also about the ways in which we watch each other and what can be drawn from observation alone. It’s not enough – it’s never enough, and though scopophilia (the (erotic) love of looking) reveals a great deal (usually about the voyeur), it can only ever offer facades, a partial picture of who a person is – not that this prevents decisions, reckless, dangerous ones, being made on that basis. The book is also about the dangers posed by judging a person too quickly on their appearance or on unreliable information, on the basis of what is seen alone. Like an ice-berg, the novel demonstrates that it’s the seven-eights we don’t see that carry the burden, the weight, that offer context and explanations.

All very well and good if there is time, but for Marnie, Joe, Vincent and everyone else, time is about to run out….

Another gripping, fantastic novel from one of the greats in the psychological thrillers/crime genre.

Damn… now I have to wait for his next one…

Five out of five plus!

August 7, 2013

Book Review: The White Princess by Philippa Gregory

The latest Philippa Gregory book, The White Princess, is the fifth in her “Cousins War” series and follows the fortunes of Elizabeth of York after Richard III, her lover, has been killed and Henry VII (father of King Henry VIII) has ascended the throne. Forced to marry Henry and prove her family’s loyalty to the new dynasty, Elizabeth struggles with what’s required of her. Comparing her husband to Richard, she finds him wanting – and with reason.

As the first of the Tudors and a foreigner in all but name, Henry has to prove himself worthy of the crown – in terms of his leadership but also his blood. There are those loyal to the House of York who perc eive him as a usurper and for the duration of his reign, plot to overthrow him. Claimants in the form of the princes in the tower (Edward and Richard – Elizabeth’s younger brothers who disappeared, believed murdered by Richard III) crop up everywhere – particularly Richard – and folk rally to their side. Scotland, Ireland, France – all collude to overthrow the king. Thus, Henry, raised abroad and under the thumb of his ambitious mother, Margaret Beaufort, sees threats and enemies everywhere, including in the shape of his beautiful wife, who is also the heart of the York clan. This affects not only his relationship with his wife and children, but with his court and people.

eive him as a usurper and for the duration of his reign, plot to overthrow him. Claimants in the form of the princes in the tower (Edward and Richard – Elizabeth’s younger brothers who disappeared, believed murdered by Richard III) crop up everywhere – particularly Richard – and folk rally to their side. Scotland, Ireland, France – all collude to overthrow the king. Thus, Henry, raised abroad and under the thumb of his ambitious mother, Margaret Beaufort, sees threats and enemies everywhere, including in the shape of his beautiful wife, who is also the heart of the York clan. This affects not only his relationship with his wife and children, but with his court and people.

Covering at least a dozen years of Henry’s reign and Elizabeth’s marriage to him, I found Gregory’s interpretation of Henry’s insecurity and the possible reappearance of Prince Richard, the Duke of York, interesting. Told from the first person point of view of Elizabeth, you get the sense of strong female bonds, of what women were forced to endure and how often they had to bite their tongue or compromise their morals for their own sake and that of those they love and seek to protect. Elizabeth lacks her mother’s fire (perhaps she observed and learned), but does retain an inner strength in Gregory’s rendition. Though, there were many times you wanted to slap her. How she could love a man like Henry – selfish, needy, paranoid and a “mummy’s boy” beggars belief – especially in the way he is represented in this novel.

That was the least attractive aspect of this book – the portrayal of Henry. He had no redeeming qualities whatsoever – insightless, fickle, demanding – a complete arse, actually.

Nonetheless, Gregory does have a compelling writing style and even when you’re most fed up with characters and the repetition of phrases and ideas continues (occasionally too much and this is a flaw in the book), you are drawn into this world of religion, politics and royalty, and the burgeoning romance at its centre, and it’s Elizabeth who takes you with her on a journey into the privy rooms, court and bedrooms of the greatest in the land. The words unfold, poetic at times, sharp at others, and yes, repetitive too, but Elizabeth’s world and the pressures under which she must operate and find her place are well drawn.

I didn’t enjoy this book as much as I have some of the others and that’s because there was a sense in which Gregory kept telling the same story over and over, emphasising the same characteristics and foibles and concerns of the main individuals as well. There wasn’t so much character growth in this novel as diminishment. That being the case, it was hard to invest in them. Knowing the history and the conclusions to the story of great historical figures does not take away from the reading pleasure of historical fiction, on the contrary, it can enhance it as you seek to uncover how the author reads the times and people involved, the hues in which she paints them. Whereas Gregory has been unsurpassed with some of her books, in this one, she is – perhaps aptly – too black and white – thus the White Princess fades into a snowy backdrop that, ultimately, disappoints more than it gratifies.

Nonetheless, I did mostly enjoy the book and will look forward to the conclusion.

Rated 3.5 out of 5.

May 24, 2013

Book Review: The Golden Egg, Donna Leon

The twenty-second book in the Inspector Brunetti series, The Golden Egg starts slowly and unfolds at a pace fitting to its autumnal Venetian setting. The weather is turning and people are gradually retreating indoors, retiring from an outside life to an inside one and turning inwards and thus reflective, which is a good way to describe this gem of a book. It’s highly reflective – of character, human nature, identity, community and what makes family.

Asked to investigate a minor infringement among shop-keepers and their shopfronts in a sestiere as a favour for his boss, Brunetti does so unwillingly. But when his wife Paola asks him to look into the death of a kind, disabled man who worked at their dry-cleaners in the same region, a man who no-one seemed to notice much or care about, Brunetti uncovers a nest of secrets, cruelty and lies.

I wasn’t sure at first what to make of this book. It was quiet, with very little drama at one level and yet, in the telling of Brunetti’s discoveries about the man with no identity, only a mother who refuses to cooperate with the police, a tragic tale begins to emerge – one in which family is at the very heart. Of course, one of the delights of Leon’s novels is that family features in every single one – Brunetti’s. Regular readers have come to love Paolo, the children, and the ways in which the Bruntettis come together over meals and deal with the vagaries of adolescence, work and life. In this novel, the reader can’t help but compare the comfort and love the Brunettis offer each other, even when angry, tired and hurt, with what the Inspector finds; how “family” can be something that bonds and binds but also something that imprisons and ruins.

I wasn’t sure at first what to make of this book. It was quiet, with very little drama at one level and yet, in the telling of Brunetti’s discoveries about the man with no identity, only a mother who refuses to cooperate with the police, a tragic tale begins to emerge – one in which family is at the very heart. Of course, one of the delights of Leon’s novels is that family features in every single one – Brunetti’s. Regular readers have come to love Paolo, the children, and the ways in which the Bruntettis come together over meals and deal with the vagaries of adolescence, work and life. In this novel, the reader can’t help but compare the comfort and love the Brunettis offer each other, even when angry, tired and hurt, with what the Inspector finds; how “family” can be something that bonds and binds but also something that imprisons and ruins.

Deeply emotional and psychological, this novel plumbs some nasty depths in its quiet, understated way. Once more, Leon features the watery streets of Venice, the food, the quirky characters, but hovering in the background and shifting to the foreground at times is the idea of facades, of “shop-fronts” if you like – how we present one version of ourselves, wear a mask, and it’s only when you bother to seek what lies behind that you may be shocked at what you find. It’s also about communication – the failure we sometimes have to ask the questions we should, to “see” through language as much as with our eyes and how this can shape and break community.

In a languorous, but genuinely awful way, through patient and persistent communication/interrogation (which is always so gentle), the façade that was built around the disabled man is slowly torn down. While I guessed most of what was going on well before it was revealed, I didn’t see the final, terrible disclosure. Nor does Brunetti.

It’s testimony to Leon’s wonderful prose and story-telling abilities that, along with the Inspector, we reel at what is found, at the capacity for enduring revenge and cruelty that people are capable of and the legacy of “family.”

This is another crime book, but the subtleties and emotions that are explored make it so much more as well.

Book Review: Wine of Violence by Priscilla Royal

Still on my medieval history binge, this book, by Priscilla Royal was recommended to me by a friend. The short novel set in 1270, tells the story of Sister Eleanor, the newly appointed prioress of a monastery that houses both monks and nuns in one of the only orders that allowed such co-mingling during the Middle Ages.

Blessed with a quick mind and youth, the new prioress encounters not just resistance form the older monks and nuns who can’t reconcile her age and attractiveness with her abilities and who resent the of imposition of someone favoured by the king upon them, she also has a dead body to deal with.

Blessed with a quick mind and youth, the new prioress encounters not just resistance form the older monks and nuns who can’t reconcile her age and attractiveness with her abilities and who resent the of imposition of someone favoured by the king upon them, she also has a dead body to deal with.

Having only arrived a few days before, Sister Eleanor is tasked with bringing to justice the murderer of a popular and elderly monk, a dear friend of the former prioress and a man above suspicion or, so everyone believed until he’s found not only with his throat cut, but with his genitals severed.

The first of many bodies, Sister Eleanor finds herself sorely tested and not even the arrival of a new, young monk, Brother Thomas, promises aid. However, Thomas is more than he appears and in him, Sister Eleanor has both a friend and an ally.

What I really liked about this book, apart from its portrayal of cloistered life in the Middle Ages, was the frank and unabashed way it deals with sexuality among a brother and sisterhood. Sexuality and friendship. Accepting that those of the same se also found love and could (and could not) reconcile it with their teachings, the novel explores what it might have been like and levels of tolerance and intolerance.

As a crime book, however, it wasn’t as strong. While the murders were interesting and the red herrings well cast, when the murderer finally confesses everything holding a knife over a prospective victim, I felt a bit like I was reading Crime Writers 101. I thought this was what you don’t do – have explanations delivered neatly by the villain at the nth moment. This mechanism has been spoofed so often in film, books and TV, for a moment, I thought it was a joke here as well. Alas, it wasn’t. It cast the remainder of the book in a different light and I found myself feeling cross and disappointed.

However, as a novel that explores the human heart, needs and desires and the way these intersect with faith, I found it quite rewarding.

Book Review: Bombproof by Michael Robotham

Hang on to the edge of your page, because this is one helluva ride.

Robotham’s books need to c ome with a health-warning: inclined to induce insomnia. I read Bombproof in one sitting, staying up to watch the sun sneak through the blinds and hear the birds begin to bloody well sing. Serves me right for starting it so late at night. A shorter novel than some of Robotham’s others, it’s also an incredibly fast-paced book that follows the extraordinary mis-adventures of the gorgeously named Sami Macbeth, the “unluckiest person” in the world. Not a criminal, not a terrorist and certainly not a murderer, poor Sami is mistaken for all three and faces the hefty and deadly consequences of such labels.

ome with a health-warning: inclined to induce insomnia. I read Bombproof in one sitting, staying up to watch the sun sneak through the blinds and hear the birds begin to bloody well sing. Serves me right for starting it so late at night. A shorter novel than some of Robotham’s others, it’s also an incredibly fast-paced book that follows the extraordinary mis-adventures of the gorgeously named Sami Macbeth, the “unluckiest person” in the world. Not a criminal, not a terrorist and certainly not a murderer, poor Sami is mistaken for all three and faces the hefty and deadly consequences of such labels.

Falling into one scrape after another, Sami finds himself embroiled in a plot to sabotage evidence in a major case. When his involvement goes horribly wrong, resulting in the blowing up of a passenger train in the London underground and the grisly death of his accomplice, Sami find himself being hunted by the entire metropolitan police, the criminal elements in the city and his face plastered all over the media.

With nowhere to run, nowhere to hide, Sami turns to the one person who can help: *sound the trumpets*. Enter, stage right, Vincent Ruiz. Grizzled, retired and with better things to do than hunt a terrorist loser, there’s nonetheless something about Sami that appeals to Vincent. Maybe it’s his underdog status, maybe it’s the fact all the poor bastard wants to do is find his sister, or maybe it’s because despite the best minds in the business being focused on capturing Sami, they appear to have missed the most important clues of all…

A great read that really pulls no punches when exposing the role of the media in constructing heroes and villains, Bombproof is for those who love a terrific crime tale, a swift and spine-chilling thriller and /or are fans of Robotham’s work or , like me, all three. No doubt, Bombproof is an explosive read(Sorry, terrible, but I couldn’t resist).

May 23, 2013

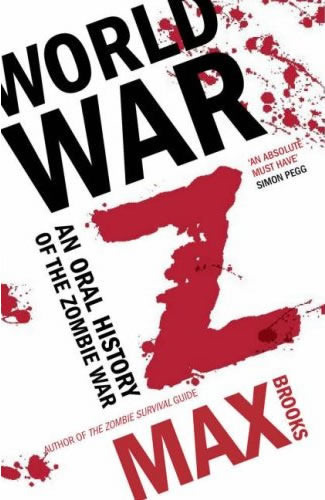

Book Review: World War Z by Max Brooks

For quite a while now, people whose reading judgement I trust have been saying to me “you must read this book.” Instead of encouraging me to rush out and immerse myself in whatever narrative is being recommended, a kind of reluctance, an inertia to do as I am bid, creeps over me. This occurs for two reasons: one, I’m afraid that the suggested book will fall short of my growing expectations and that I’ll be disappointed. This leads to the second reason which is, how do I tell someone who loved the book so much they wanted me to share the experience that it fell short? Will it be the end of a friendship, the end of exchanging novel ideas?; the exclusion from the all-important book-sharing club? Will my friend think less of me if I don’t like it as much as he or she did? I find these notions always beset me when I am told I “must” read a particular book. That I am often far from disappointed when I finally do doesn’t seem to matter, the apathy/fear hits me time and time again and makes me procrastinate about starting the new title.

I am a damn fool. If I’d listened to those who told me I must read World War Z by Max Brooks a couple of years ago and since sooner, I could have had the incredible, exhilarating, heart-wrenching, fist-clenching, teeth-grinding, anxiety-provoking experience reading it was much, much earlier.

Would I have wanted that? Hell. Yeah.

I may as well get it out of the way upfront; World War Z was not what I expected. I knew it was a “zombie story” and, having read and loved Mira Grant’s Newsflesh trilogy (again, a recommended “must-read” that  didn’t disappoint me one iota) and being absolutely enthralled by the Walking Dead Compendium by Robert Kirkman et. Al (and TV show), I shouldn’t have stereotyped Brooks’ novel (no relation BTW) as a lighter-weight version of what had already been done magnificently – but I did. More fool me. Admittedly, seeing shorts for the Brad Pitt film fuelled that notion and, while I love that type of full-scale action-adventure in my film, I desire something a little more intelligent, psychological, challenging and probing in my zombie novels.

didn’t disappoint me one iota) and being absolutely enthralled by the Walking Dead Compendium by Robert Kirkman et. Al (and TV show), I shouldn’t have stereotyped Brooks’ novel (no relation BTW) as a lighter-weight version of what had already been done magnificently – but I did. More fool me. Admittedly, seeing shorts for the Brad Pitt film fuelled that notion and, while I love that type of full-scale action-adventure in my film, I desire something a little more intelligent, psychological, challenging and probing in my zombie novels.

Enter World War Z – from stage right left and every other conceivable direction. I finally bought it and began reading it… Well. This book grasped me by the imagination, throat and soul and didn’t let me go. To call it remarkable is to undersell it. Brooks’ work is an erudite, humane, political, emotional and psychological reckoning of what happens when humanity turns on itself – when the enemy is already dead and killing fellow humans who might not agree with your religion, ideology, culture, sexual preferences or anything else, simply adds to their ranks and places the future of the planet at greater risk.

Let me explain without spoilers. The book is set ten years after a decade-long war with zombies has all but finished and is basically the remnants (the humanity component) of a report that was commissioned by an organisation to record for posterity what occurred in the lead up to mass infection, during the outbreak and consequently. The lead investigator has taken it upon himself to include unique stories from all the people and countries he visits, much to the chagrin of his boss who feels that history wants facts only. But, as the investigator (who is largely absent from the novel) states: “what’s history without humanity?” Indeed.

So, World War Z is what’s been left out of the official report. As such, it’s a collection of very personal accounts and opinions, a memory bank if you like, of a huge variety of people. From an astronaut stranded in a space station, to a marketeer looking to profit from fear, to Japan, China, Uruguay, Russia, the United States, Mexico, and many, many other countries big and small; from veterans, to teachers to blind gardeners and everything in between, this other report is the voices of those who aren’t normally heard. It’s a testimony, their testimonies of what they feared, endured, survived and their memories of the times and those who didn’t. It’s what they were forced to do to simply survive, to recognise what they could either raise or lower themselves to do when everything, absolutely everything is at stake.

It’s also about how individuals from different cultures, backgrounds, ages and occupations, with different needs, wants and desires, respond to a threat that has never before been imagined or experienced.

I found this way of writing, the whole concept behind this book, utterly extraordinary. While the threat of zombies underpins the action and is the narrative drive, it’s also about so much more. Brooks manages to inhabit every character, no matter who they are, where they’re from or how brief their story. There’s a gravitas and respect for what’s being shared, what’s being exposed and this is felt in every word and page. I didn’t want this to end and yet, I did. It’s harrowing, amazing, thrilling and above all, it’s humane.

Now I am joining the ranks of those who say, “you must read this book”. It doesn’t matter if you think you “like” zombies or not. In this instance, it’s irrelevant. If you’re reticent like I was to start with, I do understand but all I can do is urge you to ignore this feeling so you don’t have any regrets – the regret I didn’t “know” this book sooner.

For now, I am going to read it again.

May 8, 2013

Book Review: Blackout by Mira Grant

Book Three in the Newsflesh trilogy, while a terrific read that ticks many of the boxes, didn’t leave me as impressed or as satisfied as the first two in the series. The plot is strong, the characters very good and their motivations mostly sound and plausible. Whereas Deadline was very much a quest cum road trip, Blackout uses many of the same tropes and subsequent ideas but, whereas they came across as original and compelling in the second book, in Blackout, you have a feeling of situations and outcomes repeating themselves. This also happens with manyexplanations. For example, the number of times Shaun has to justify the fact he is or is not going mad regarding Georgia is far too many. We get it. Likewise, with the explanations regarding the impact the virus had on Georgia’s eyesight and the differences between one way of imagining her and another. There was barely a description or reference to eyes that didn’t go over familiar ground and it became irritating and redundant and in the end infected the pace of the story.

Three in the Newsflesh trilogy, while a terrific read that ticks many of the boxes, didn’t leave me as impressed or as satisfied as the first two in the series. The plot is strong, the characters very good and their motivations mostly sound and plausible. Whereas Deadline was very much a quest cum road trip, Blackout uses many of the same tropes and subsequent ideas but, whereas they came across as original and compelling in the second book, in Blackout, you have a feeling of situations and outcomes repeating themselves. This also happens with manyexplanations. For example, the number of times Shaun has to justify the fact he is or is not going mad regarding Georgia is far too many. We get it. Likewise, with the explanations regarding the impact the virus had on Georgia’s eyesight and the differences between one way of imagining her and another. There was barely a description or reference to eyes that didn’t go over familiar ground and it became irritating and redundant and in the end infected the pace of the story.

In terms of story, however, the plot is good and the science and cunning of desperate men and women well-handled. Still searching for answers to Georgia’s death and the whole infection, Shaun and his crew stumble upon secrets, lies and possible truths including the greatest one of all, one that will test their credibility beyond limits. Fortunately, it didn’t test the reader and we accept the “truth” of this grave new world and the horrors contained within.

Like other books in this genre, the Newsflesh trilogy and Blackout in particular reveal that the monsters we live with are not necessarily those who manifest as such: that, in fact, the monstrous is within us all and it’s often down to the choices we make whether or not this aspect of our selves is given reign.

Overall, a good conclusion to a great series.