Karen Brooks's Blog, page 10

May 8, 2013

Book Review: Deadline by Mira Grant

I ha ve to say at the outset that I was simply stunned by Mira Grant’s first novel in this series, Feed and, after the shocking conclusion, wondered how she could follow it up… well, she did. Deadline is another wild ride that takes the reader deeper into the post-apocalyptic, virus-ridden world where zombies, pharmaceutical companies and politicians rule.

ve to say at the outset that I was simply stunned by Mira Grant’s first novel in this series, Feed and, after the shocking conclusion, wondered how she could follow it up… well, she did. Deadline is another wild ride that takes the reader deeper into the post-apocalyptic, virus-ridden world where zombies, pharmaceutical companies and politicians rule.

Greif-stricken and believing he’s going mad after the horrifying death of his beloved sister, Shaun Mason is searching for a reason to both live and die. Aiding him in this quest are the remaining members of his blogging business. Together, they set out to uncover the real reason why Georgia had to die and what they find not only break’s Shaun’s heart and mind, but will leave the reader reeling.

Fast-paced, tautly plotted, this is speculative fiction at its meaty best. The underlying commentary on media, science, truth and how we both produce and consume them all is powerful and very gratifying – food for thought. Thoroughly enjoyed and highly recommend.

Book Review, Shift by Hugh Howey

After reading Wool, the first book I’d read by Hugh Howey and one that has critics and fans alike raving, I was hooked. Quite simply, the entire concept behind Wool, the sparse and heart-achingly gorgeous writing, the characters and what they endured and survived (or didn’t) had me wanting to read and know more by this author and about this world – our world in a future that we can only hope is never realized.

Imagine my delight when I discover that Shift is the prequel to Wool – this is the book that comes to explain the Silos, their purpose and the terrible choices that led what’s left of humanity there.

Written as parallel narratives – one from the point of view of Troy, a technician and leader in a Silo in the future and one from the perspective of Donald, a budding politician in contemporary times swept up in a tide of power, corruption and the assertion of a skewed morality that has deathly consequences, Shift is a commanding but sometimes difficult book. The writing is very good but lacks the elegiac flow that Wool often displayed.

Gaps and omissions mean that the reader is trusted to put some of the pieces of this comp;ex jigsaw together and, while many have no doubt succeeded, I was often left scratching my head and needing to reread sections to understand what I missed – how A plus B led to G. I confess, it didn’t always work and I am still wondering about aspects of the novel but not enough to go back.

I guess that’s another difference between Shift and Wool. In Wool, I really cared about the characters – I was invested so heavily in their futures and choices, I wept, cried aloud in fear, shouted for joy, even over the most simple of things. Here, I didn’t like them nearly as much and often felt indifferent when they exited the chapter or tale. I do wonder, however, if this was a deliberate strategy on the part of Howey for what is clear is the obejctivity that was required to create the world of Shift and Wool, the utter conviction in a moral code that doesn’t allow for detractors or questioning – to do so is weak and threatening and both must be eliminated.

So while Shift, by segueing back and forth, reveals the building of the Silos, the politicking and manipulations as well as the ethically fraught reasons behind them – what led to and the rationale for their being inhabited, it’s not always clear-cut or easy to unearth – but perhaps that’s the point. Certainly, towards the end of the book, once the notion of hierarchy within the silos and the way habits and idiosyncrasies are formed is established, characters who you can identify with and feel sympathy for, including some from Wool, emerge.

I look forward to the next installment to see how Howey will bridge the then and now and move into the future. His imagination is fierce and boundless, unlike the Silos, and his way of expressing possibility, seductive.

Book Review: The Snowman by Jo Nesbo

I didn’t simply read this book by Jo Nesbo and featuring his taciturn and apparently difficult to love detective, Harry Hole, I devoured it. I tucked myself on a chair one cold Sunday aft

ernoon and basically didn’t lift my head unless it was to put food or drink into it. I supped on words, a cracker of a plot and some wonderful characters.

Hole’s rel

ationship with Rakel is over. His reputation at work as a brilliant but unconventional and difficult detective looks set to ruin him. Enter a strange letter that is at once both threat and

dare and which invites Hole to guess who “made the Snowman”. In order to do that, Hole first has to work out exactly what the “snowman” (apart from the obvious) might be.

When a series of women disappear and, apart from one or two whose grisly remains are discovered in shocking circumstances, and their absence is linked to the building of a snowman, Hole begins to make the impossible connections – connections that span years, inconceivable unions and implausible motives. Joined in his hunt for the killer by a gung-ho female from Bergen who’s strong credentials compliment her zeal, Hole finds himself with a good team pitted against an intelligent and ruthless killer who, while he treats his female victims with cold brutality, with objectivity and scorn, is clearly acting out some terrible personal demons as well.

Like all Hole’s cases, this one becomes personal for the detective – only in ways he never could have imagined.

The prose in this book is at once poetic and awful. It conjures up such a frisson in the reader. I could feel my heart racing, my skin was creeping as I absorbed the story – from the beautiful descriptions of the falling snow, secret and gentle, to the God-awful blood bath that each murder and crime scene becomes. The tension builds and builds. Just as Hole has physically changed in this book – he is leaner, meaner, denuded of hair and spare flesh, there’s a sense in which this story is as well. It’s raw and terrifying.

While I guessed the killer not too far into the book, it didn’t spoil the plot or story for me, on the contrary, it enhanced the entire reading experience, which had me wondering, was this Nesbo’s intention? In that way, the reader is like the killer, watching Hole blunder, stumble in the dark and snow, alight on one possibility only to have it torn away. Knowing what Hole did not built the suspense in fabulous ways and did not take one shred of excitement or reading pleasure away from the conclusion or denouement.

I so enjoyed this book I immediately grabbed the Phantom and already know that I’m in for another reading treat (and scare!). Outstanding…

April 2, 2013

Blood of Dragons by Robin Hobb

The final book in The Rain Wild Chronicles, Blood of Dragons, concludes the epic journey of the dragons and their keepers and reveals the fates of some of the major characters whom we’ve grown to know, love and loathe over the course of four novels.

The future of Kelsingra hangs in the balance and with it, that of the newly formed Elderlings and their dragons. Mining the memories of the Elderlings past from the stone in the ancient city, it becomes apparent that only one thing can guarantee the dragons and their keepers have a future – a precious resource upon which everyone’s survival depends. But as time passes, the reason s Kelsingra was abandoned and the dragons nearly died out becomes apparent and hope for finding this resource swiftly fades.

s Kelsingra was abandoned and the dragons nearly died out becomes apparent and hope for finding this resource swiftly fades.

Close to home, treachery is afoot as certain Bingtown Traders make plans to descend on Kelsingra with a view to exploiting the wealth they believe litters the magical streets. In exotic and deadly Chalced, plots stir as the ruler formulates great plans for his survival, something that’s contingent upon dragon sacrifice and more.

The world Hobb has created here – one begun a long time ago with the Assassin’s Apprentice series, where the Rain Wilds are eluded to before being more fleshed out in the Liveship Traders series – is a beautiful haunting and dangerous place. Acid waters, rainforests and tree-dwellers, physical deformities, living ships that bond with their owners, never mind inept, narcissistic and deadly dragons as well as abused and abusive spouses all populate this magnificent and bleak world. The central characters are brought to life over the course of four books and, like the dragons who play such a pivotal role in their lives, slowly emerge from their cocoons to spread their wings and shine brightly when they’re needed or have the justice they’ve stealthily evaded forced upon them.

While some parts of the tale appear slightly rushed or brushed over (eg, the final battle over Chalced) others were given the time they deserved and the characters at the heart were satisfyingly completed. You know that’s the case when you can imagine them living beyond the last page and, as I closed the book, I could see such potential for the wondrous city of Kelsingra and the people who, along with the triumphant dragons, have chosen to call it home.

A fitting and delightful end to a complicated, sometimes slow-moving but, I felt, always gripping tale of survival, memory, power struggles and triumph against extraordinary odds. And dragons. We cannot forget the beautiful dragons.

The Wild Girl by Kate Forsyth

I’ve taken a bit of time between reading and reviewing this book, partly because I wanted to absorb the dark beauty of this stark, moving and occasionally horrifying tale, and partly because I’d no choice. I was rendered not just speechless by this marvellous novel but, for a time, wordless too as I sought ways to describe the richness of Forsyth’s work, the wonderful layers that make up the tale of Dortchen Wild, a gregarious young girl who grows up in the small kingdom of Hessen-Kassel during the Napoleonic Wars, living across a narrow lane from the then unknown Brothers’ Grimm. The beauty of the characters, the intimacy, joy and awfulness of the settings as well as the research and direct and subtle references to the forbidding stories the Grimm brothers themselves collected and retold, initially evaded me. It’s only now I can write about this amazing book. I was stunned by what Forsyth has done and urge anyone who loves the history of fairytales, history itself as well as a wonderful, page-turning novel about love, sacrifice, loss, family and the ties that cruelly and gently bind, to seek this one out at once!

Told from Dortchen’s point of view, the novel spans many years and many tribulations – poverty, war, and separation. The reader is given insight into the rise, and fall of the Wild and Grimm families’ fortunes as well as that of the rather stern ruler of Hessen-Kassell who is later replaced by a hedonistic relative of Napoleon.

Jakob and Williem Grimm are scholars who decide to collect what are fundamentally “old wives” and children’s tales for publication. Obsessed with preserving what’s a part of their country’s culture and past, they search for interesting variations and folk to relay the stories which they painstakingly record. Enter Dortchen, by now a teenager and a very able and imaginative crafter and re-teller of the old tales. It’s as a storyteller that Williem, a handsome if somewhat unhealthy figure, finally views his neighbour and little sister, Lotte’s playmate, Dortchen, through different eyes, seeing her for the beautiful young woman she’s become.

Jakob and Williem Grimm are scholars who decide to collect what are fundamentally “old wives” and children’s tales for publication. Obsessed with preserving what’s a part of their country’s culture and past, they search for interesting variations and folk to relay the stories which they painstakingly record. Enter Dortchen, by now a teenager and a very able and imaginative crafter and re-teller of the old tales. It’s as a storyteller that Williem, a handsome if somewhat unhealthy figure, finally views his neighbour and little sister, Lotte’s playmate, Dortchen, through different eyes, seeing her for the beautiful young woman she’s become.

Dortchen’s growth into womanhood is a wondrous and painful awakening into beauty, sexuality, responsibility and reality, the latter from which her friendship and passionate feelings for Williem Grimm and the stories that surround her have occasionally allowed her to escape. But reality catches Dortchen all too quickly and bleakly. Forbidden by her stern father from being courted by the impoverished Williem, Dortchen tries to accept what fate offers; but as a girl who loves stories, she also desires a different outcome. Alas, as she and Williem shift into different social circles and circumstances and people become obstacles that grow insurmountable, control of her destiny seems like something that belongs in one of Williem’s fairytales.

I don’t want to ruin the story for those who’ve not yet had the chance, but be warned, as I said above, this novel does not steer away from dealing directly with the darkest aspects of human nature – something which fairy and folk tales have always confronted – often (though not always) through allegory and metaphor. Whereas the Grimm’s were forced to moderate their collected tales for the market, here Forsyth let’s the human capacity for evil loose. Nightmares come to life in this book and it’s testimony to Forsyth’s skill and sensitivity towards her threatening subject matter that she deals with it unflinchingly and with rawness; it takes your breath away. I found myself dwelling on this part of the book and my emotions were thrown into a tumult. It may be because of personal history, but I also feel it’s because readers are able to empathise with Dortchen and the cruelty and paternal tyranny that’s inflicted upon her. It’s utterly shocking. And that’s before I discuss the casualties of war – not only those who lose their lives because of a game of politics thrones and power – but those who survive and simply endure its abuse and horror.

Against this darkness, however, a light shines in the form of love – that between siblings, friends and soul mates. No-one expresses yearning quite like Forsyth. She did it so beautifully in her first book, the wonderful The Witches of Eileann, she does it again in the sumptuous Bitter Greens but it’s here, in The Wild Girl, that it culminates into a palpable ache that reaches beyond the pages and into the reader’s soul.

Forsyth has undergone a great deal of research to write this book and come to some original and compelling conclusions about the tales and their tellers as well. The novel is peppered with some of the better and less known of the Grimm collection, so we’re given stories within stories and can draw our own comparison between the rich imaginative world of the women who pass them to the Grimms and Dortchen’s life as well.

Original, compelling, exquisitely written, this is a novel of epic and passionate proportions that offers readers so much and then even more. A book ostensibly about story-telling it’s also by a story-teller par excellence. I really think Forsyth is one of the finest writers of this generation and her work deserves the widest of audiences. She clearly takes so much pleasure and pride in what she does – but better still, she offers it in abundance as well.

Cannot recommend highly enough.

March 17, 2013

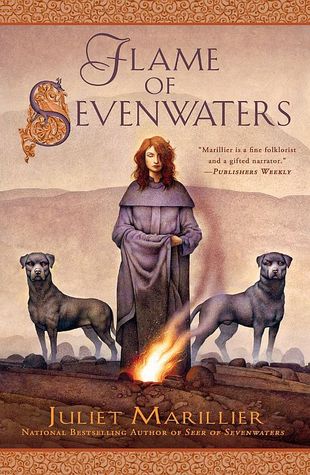

Book Review: Flame of Sevenwaters

What can I say? Oh. Wow. Talk about conjuring mixed emotions in the reader. I feel like either donning black and keening or dancing wildly through the room. I want to do the former because Flame of Sevenwaters is, I believe, the final book in this sublime series, and kick my heels up because it was so exquisitely beautiful.

This novel tells the story of Maeve, one of Lord Sean’s daughters who, in an earlier novel, Child of the Prophecy, was badly disfigured as the consequence of a fire ten years ago. Sent to live with her aunt and uncle to recover, she learns to accept her physical limitations. Cruelly twisted and maimed, Maeve’s hands are all but useless, but she proves her worth to the household in other ways, mainly by working with animals. Maeve has an uncanny knack of being able to calm and reassure even the most fractious of beasts. What Maeve appears to be unaware of is that her talent can also work with the humans who come into her sphere.

This novel tells the story of Maeve, one of Lord Sean’s daughters who, in an earlier novel, Child of the Prophecy, was badly disfigured as the consequence of a fire ten years ago. Sent to live with her aunt and uncle to recover, she learns to accept her physical limitations. Cruelly twisted and maimed, Maeve’s hands are all but useless, but she proves her worth to the household in other ways, mainly by working with animals. Maeve has an uncanny knack of being able to calm and reassure even the most fractious of beasts. What Maeve appears to be unaware of is that her talent can also work with the humans who come into her sphere.

When her uncle asks her to accompany a spirited, lovely and flighty horse, Swift, to Sevenwaters, Maeve reluctantly agrees, knowing her homecoming with be as much an emotional journey as it’s physical. In many ways, Swift’s nature functions as a mirror for Maeve’s and, in the horse’s doubts and transformation, Maeve’s is partially echoed.

Arriving back at Sevenwaters after such a long absence, she’s much changed. Forthright, loyal, brave and kind, Maeve’s mother particularly doesn’t know how to respond to the daughter she loves but whom she doesn’t understand. While her father appears to cope better, it’s really her young brother, Finbar, who seems to grasp Maeve’s needs and be able to read what she cannot articulate. Appearing at times stubborn and selfish and torn with self-doubt, Maeve’s struggles to be herself and live by her rules is also made clear.

Finding Sevenwaters on the brink of war, mostly brought about by the machinations of the lord of the Otherworld, Mac Dara, Maeve is at a loss to know how she can help. But other forces know how she can and they enlist her and her brother’s aid to resolve a dispute for power that’s long been brewing and for which Lord Sean’s family and his allies have been paying the price. But the cost of this power struggle between the fey is yet to be reckoned and not even Maeve may be prepared for the sacrifice that will be asked of her and those she loves.

I cannot begin to tell you how beautifully Marillier conjures this world and the people within it. Her prose is as lilting and haunting as the forest that encircles Sevenwaters. Her descriptions so evocative that you are transported into the stillness of the nemetons, the eerie Otherness of Mac Dara’s realm and the homeliness and memory-haunted halls of the castle.

Like all the novels in this series, there are tales within tales, stories that bind, reveal and conceal, and this novel is no exception. From the mouths of seers and seers in training come fables that function as thinly disguised lessons in life, relationships, love and choices as well as the future. Even the title of the book is a description, noun and verb. “Flame” is a role that can be fitted to more than a couple of the characters as they “flame” brightly at times. Indeed, the word ‘flame’ itself contains within it positive and negative attributes that evoke notions of destruction, cleansing, death, transformation and rebirth all at once. There is also the idea of power, steadiness, warmth and passion.

I really don’t want to give too much away, but there are two more points I’d like to make. In this novel particularly, Marillier does a simply lovely job of making her animals wonderful, steadfast and real characters. I adored the animals. Like the humans, I championed them, came to know and love them and wept copiously when they were in peril or worse.

This leads me to the other point. I cried almost non-stop throughout the final quarter of the book, pausing only to blow my nose, wipe my eyes (so I could continue reading) and absorb this magical novel. I admit, I was a compete sook, a wet-rag of emotion as I wept tears of sadness, joy, heartache and triumph. I went from sheer horror to exhilaration and was taken on such an emotional journey, all of which reminded me that, like Ciaran and the other seers who have featured throughout the series, I was in the hands of a master storyteller, someone who cares deeply about their tale and those who read it.

This was an experience I won’t fast forget and nor do I want to. But I do want to thank Juliet Marillier for creating such a beautiful world, populated by incredibly complex dark and light beings.

Parting is such sweet sorrow.

Book Review: The Tainted Coin

The last book available at present in the Hugh de Singleton series, The Tainted Coin, ups the ante from previous books in terms of plot and pace. A man is found brutally beaten and dying on the steps of St Andrew’s Chapel. His last words, uttered to Hugh, revolve around a coin, which is later found in his mouth. A Roman coin of some value, it prompts Hugh to search for its origins and to see if he can discover who killed this itinerant hawker.

Others, however, are determined to prevent Hugh and so once again, the surgeon/bailiff finds himself in danger. Assisted by the burly groom, Arthur, Hugh uncovers a kidnapped woman, a wi

ly and unscrupulous knight and the involvement of his old enemy, Sir Simon Trillowe. But when the moral Hugh performs a risky rescue and takes into custody (for his own safety)one of the knight’s cronies, he finds himself at terrible odds with his master, Lord Talbot.

Threatening to quit if Lord Talbot forces him to hand over the man he’s rescued, Hugh finds himself in a moral quandary and under threat of losing the livelihood and place he’s grown to love. But as the danger grows, Hugh is forced to confront new and old enemies and even his employer and the outcome is as unpredictable as his baby daughter, little Bessie.

Once more, setting and period are beautifully captured and the characters are brought to life with an economy of prose and purpose. In some ways, the story is fairly predictable, but I didn’t find this a flaw. Rather, I enjoyed learning how events unfolded and the motives of those involved. If anything, being a couple of steps ahead of Hugh made you champion him and his investigation more.

This is another delightful installment in a series of which I have grown so fond. It can either be read as a stand alone or as the latest book, either way, there are rewards aplenty for newcomers to Hugh’s remarkable and dangerous life and those who have followed his rise and minor falls. For lovers of medieval whodunits, history and just damn fine reads.

I know there’s a new book in the wings, soon to be published and I cannot wait.

March 10, 2013

Book Review: Unhallowed Ground by Melvin R Starr

Once I started reading this series featuring Hugh de Singleton by Melvin R Starr, I couldn’t stop. Searching for historical fiction that really captured a specific era (I was looking for the late 1300s, early 1400s) but was tight, well written and engaging proved harder than I initially thought – in that, I had already read so many good novels, it was hard to find new material . That was, until I stumbled upon Starr’s series.

. That was, until I stumbled upon Starr’s series.

The fourth book in the Hugh de Singleton series, the surgeon who becomes a bailiff to Lord Gilbert Talbot (he of the arching brow), Unhallowed Ground is probably grimmer and darker than the other books in one way and yet, in another, also has a delightful and quite charming parallel narrative as Hugh is no longer a bachelor and early in the book he receives some wonderful news that will change his and Kate’s lives.

The tale commences with the death of a character we’ve come to know and loathe from an earlier book, the violent and manipulative Thomas Atte Bridge. Discovered hanging from a tree at the crossroads, it’s first believed that the man committed suicide, only, Hugh and Thomas’ poor wife, don’t believe that to be the case.

But when Hugh’s investigation uncovers a ream of suspects, all of whom not only had good reason to do away with Atte Bridge, but are decent upstanding citizens as well, Hugh finds himself facing a serious moral dilemma. When his investigation uncovers a criminal prepared to harm more than a villain, but Hugh and his wife, the bailiff’s anger is roused and he stops at nothing to find out who’s the culprit and why they’re prepared to go to such lengths to stop him discovering their identity. Only this time, the answers are not what Hugh expects…

Against the backdrop of the investigation, life at the manor and within the surrounding village is gently drawn. The reader follows Hugh on his investigations and intellectual peregrinations as he tries to fathom who the most likely culprit might be. In this book, we are also given a peek into married life and the role of a new wife and doting husband – and it’s utterly charming but realistically drawn as well. Likewise, the travels that Hugh undertakes as he seeks the killer, the insights into professional roles and respect for skills, medical, surgical, carpentry, horsemanship etc. are also lightly but accurately drawn.

These books are like a time capsule into a world and time past, but as I say repeatedly in my reviews, without sacrificing story. The pace can be slow, but the writing is always elegant and the characters beautifully drawn. Another delightful read.

Book Review: A Trail of Ink by Melvin R Starr

The third book in the Hugh de Singleton series by Melvin R Starr is, thus far, my favourite. Commencing from where Book Two, A Corpse at St Andrew’s Chapel leaves off, it focuses on Hugh’s hunt for his former master, John Wyclif of Oxford’s missing books.

Thrown into life in medieval Oxford, a university town where the schism between “townies” and “gownies” is very real, Hugh must cope with the prejudices of those accorded the privileges that come with titles, even if it means remaining silent while one of these titled men steps out with the young woman to whom Hugh is fast losing his heart, the intelligent and sparkling Kate C axton.

axton.

Filled to the brim with characters of the villainous and noble kind (not of blood, but personality), trips to academic halls, taverns, castles and medieval roadways, murders, medicines and mayhem, the novel is also peppered with the hopeless attempts at romance and the flirting of Hugh. These clumsy efforts further endear him to the reader, but not to his rival for Kate’s affections, Sir Simon.

Soon, it’s not the missing books that Hugh has to worry about so much as himself.

Once again, Starr throws the reader into the violent, heady and slower pace of medieval life, describing clothes, meals, rites and faith with a deft but subtle touch that never detracts from the pace or story. Whether Hugh is being a surgeon, bailiff, detective or lover, he’s at all times believable and complete lovable.

A terrific addition to the series.

Book Review: A Corpse at St Andrew’s Chapel by Melvin R Starr

The second book in Starr’s series about Hugh de Singleton, surgeon and bailiff for Lord Gilbert Talbot, centres on solving the murder of the beadle of Bampton, Alan. Found outside St Andrew’s Chapel, Alan has had his throat ripped out and mysterious marks on his body. The coroner decides it was a wolf that killed him. Hugh, of course, isn’t convinced and so sets out to discover just who or what took the beadle’s life. Only, his investigations put his own at risk and, when he’s attacked late one night, he understands that the killer may be closer than he thinks…

In Hugh de Singleton, Starr has created the most unlikely of heroes. By his own admission, he’s not very handsome, athletic or even brave. Hugh nonetheless manages to be incredibly endearing, loyal and even, occasionally, funny (eg. He longs (in each book) to be able to arch his brow like his lord and fails). More than capable of negotiating with belligerent villagers or extracting what he wants from a lord who’s obviously glad to have his capable services, Hugh is also highly intelligent and patient. So is the story. Bringing the period (1365) to life with fabulous detail – but details that don’t detract from the story – and ambience, the daily life of a surgeon and bailiff and all the characters that make up local towns and villages and the laws, hierarchy and faith that bind them together are brought to life.

What are of particular interest with these books as well are the medical procedures, which are unpacked for the reader, sometimes in wince-worthy ways. Likewise, the food, the rituals and the expectations placed upon an individual due to their sex or roles are beautifully explored.

This is an easy and engaging read that should keep lovers of good historical fiction and mysteries more than satisfied.