John Podlaski's Blog, page 9

April 13, 2024

Association looking for Canadians who served during the Vietnam era

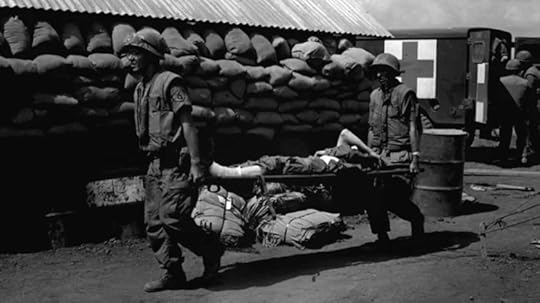

The Canadian Vietnam Veterans Memorial Association which erected a CVVM monument in Windsor is looking for Canadians who served in the Vietnam War to be honored in July 2025. (KEITH TRACY SUBMITTED PHOTOS)

If you are a Canadian or have dual citizenship and served in the Vietnam War, you are wanted! Read this article for more information.

By Linda May

The Canadian Vietnam Veterans Memorial Association Chapter 1 is searching for perhaps as many as 40,000 Canadians, or people with dual citizenship, who served during the Vietnam era.

The CVVMA is responsible for a memorial — known by veterans as The North Wall — at Assumption Park on Riverside Drive in downtown Windsor, Ontario near the Ambassador Bridge.

Originators of the memorial included Americans Rick Gidner, the late Ed Johnson, and Chris Reynolds. They wanted to express their appreciation to the Canadians with whom they served.

People — especially those with Canadian citizenship who served in Vietnam or during the era — are invited to attend the 30th annual memorial service and rededication of the Canadian Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Sunday, July 6, 2025.

The Canadian Vietnam Veterans Memorial Association that erected a CVVM monument in Windsor is looking for Canadians who served in the Vietnam War to be honored in July 2025.(KEITH TRACY SUBMITTED PHOTOS)

The Canadian Vietnam Veterans Memorial Association that erected a CVVM monument in Windsor is looking for Canadians who served in the Vietnam War to be honored in July 2025.(KEITH TRACY SUBMITTED PHOTOS)Taking place right now is the “Be Counted” effort, a quest to find more Canadians who served in the U.S. military. The accurate number of those who were Canadian citizens at the time of enlistment or draft is unknown to the organizers, but they want as many as possible to be recognized, counted, and be welcomed home. Proof of service and discharge, and Canadian citizenship is required. See canadiansinvietnam.com.

Keith Tracy of Windsor, a U.S. Army veteran who was assigned to Germany as an intelligence specialist after he enlisted in 1964, is working with genealogist CJ Scott in doing the research and data collection. They have heard from people all over Canada and the United States who want to be part of the 2025 event.

Tracy said there are 171 Canadians on the memorial who died in Vietnam, and two more names will be added soon. Seven are still missing in action and are unaccounted for.

One of the names of the deceased is Greg Rindy, a Canadian-born man who attended Roseville High School. His sister Pam Reed said he arrived in Vietnam in April 1968 and was killed in action two weeks later. He is buried at Cadillac Memorial Gardens.

Canadian veterans typically did not talk a lot about their service in Vietnam.

“Technically, back in day, it was illegal for Canadians to join, but because of the close relationship between Canada and the U.S., this has kind of been overlooked. It’s really not something that was enforced,” Tracy, a retired welder and truck driver, said. “Canadians served in the Civil War, if you want to go back that far. There are Canadians who are in the U.S. military today.”

Tracy thought he was pretty much alone in his U.S. military service until he began finding neighbors and friends who were Vietnam veterans. Then he became acquainted with others because of the memorial.

“I just put my uniform aside,” Tracy said. “Like most Canadians, the only people who really knew we served were the family members. I didn’t belong to any Legion at the time. I just moved back into civilian life.”

He said that the memorial is supported by Royal Canadian Legions across the region but it took about a dozen years after the controversial and divisive war ended for the vets to be accepted.

There is unity and mutual respect now.

“The North Wall Riders Association was established after the memorial was built,” Tracy said.

That’s a group of motorcycle riders dedicated to supporting veterans functions, raising awareness of veterans, and supporting military service members.

“There was a small group who formed up the riders who came to us asking if they could use our symbol as part of their identification and we said yes,” Tracy said. “They’ve been a great organization throughout the years and supported veterans issues across the board, helping veterans in need and raising money. They are a separate unit to us and do their own thing. The Legion supports us and allows us to use their facilities for meetings.”

The CVVMA started collecting photos of the 173 people named on the monument. That led to the “Be Counted” project to see how many Canadian vets they could find. They got some good local and national publicity on their efforts.

“Six weeks later we were bombarded with information from people all across Canada and the United States. We just want to get as many as we can since we are also going to be going into the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War. A lot of people in Canada never got any recognition. You know how hard it was for American Vietnam veterans, well, it was the same for Canadians. They just went home to their areas and closed the door. This is an important part of Canadian history. Come July 6 of next year we’ll publish the information we get,” Tracy said.

Tracy guessed 2,000 people might show up at the memorial for the celebration.

“We have family members who want to come. Some of the veterans have passed away. We have calls and emails from grandchildren who know all about their grandfathers’ service and just want to represent,” he said.

“We realize we are not going to reach 40,000 but we hope we get a good portion to come to Windsor and get a proper welcome home,” he said. “I know guys personally whose family didn’t know they served until three or four years ago because they just didn’t talk about it. A lot of guys in this country (Canadians) really did a lot of good stuff over there from all ranks and all branches of the service — from ground troops to pilots. It’s a history that needs to be saved.”

Tracy was a consultant on a book published last fall, “Canada’s Lost Sons of the Vietnam War,” by Jason B. Collins.

“We have never had a negative response over this and that tells me that the people out there don’t want memories to be lost,” he said.

An inscription on the memorial reads: “As long as we live, you shall live. As long as we live, you shall be remembered. As long as we live, you shall be loved.”

Eastpointe resident and Vietnam-era vet Mike Schneider said eight Canadians representing CVVMA came to the Vietnam Veterans of America Michigan State Council to enlist the help of VVA chapters to find Canadians and Canadian-Americans who volunteered or were drafted into service.

“There were six Canadians from Michigan who died in Vietnam,” Schneider said.

Their biographies are recorded in books that travel with the Michigan Vietnam Veterans Traveling Memorial circulated by VVA Chapter 154 of Clinton Township.

“The guys who wanted that memorial had trouble getting it put somewhere. They tried to do it in Ottawa, and they finally got the mayor of Windsor to say, yes, you can put it there. When it was dedicated in 1995, there was a giant amount of people there, tons of motorcycles, and a lot of our guys went over for the celebration,” he said.

There has been an annual service every July since 1995 to honor those who died or went missing. Please help to spread the word!

*****

This article originally appeared in the Macomb Daily newspaper on April 6, 2024.

For more information about Canadians who fought in the Vietnam War, please read my earlier article on this website: https://cherrieswriter.com/2015/11/13/lost-to-history-the-canadians-who-fought-in-vietnam/

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

April 6, 2024

Creative Solutions to Overcome the Drawbacks of Gun Trucks in Vietnam

Jackie Edwards contacted me after reading my earlier article about Gun Trucks in Vietnam (Link included at the end of this article) and thought it would be interesting to write about the ingenuity of Gun Truck crews to overcome early limitations. This is what he wrote:

As he was awarded a Bronze Star for Valor more than 50 years after saving comrades during a firefight, a Vietnam veteran from South Carolina acknowledged the ingenuity of gun truck crews with whom he had worked to help keep vital supply lines open during the war. Sergeant Deyo had been responsible for maintaining and operating the four homebuilt trucks in his company, and while his team deterred attacks on numerous occasions, one fierce ambush left two of his gunners wounded. Vietnam gun trucks were important assets in protecting military convoys from ambushes and attacks, however, they also had several drawbacks, including vulnerability to small arms fire, susceptibility to breakdowns, and high fuel consumption. Gun trucks were already improvised and makeshift vehicles adapted by desperate soldiers, so it was natural for their homebuilt designs to evolve. Throughout the war, creative solutions were continually implemented to address weak spots and further enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of gun trucks.

Protecting Essential Supply Lines

Protecting Essential Supply Lines

From procuring and preparing vehicles for shipping in advance of deployment to conveying vital supplies to individual units, the US Army Transportation Corps provided an essential service during the Vietnam war. As well as large numbers of vehicles, huge amounts of other supplies including construction materials, maintenance tools and personal items for soldiers were transported across extensive air and sea routes to ports in Vietnam. Once vehicles and supplies arrived at the coastal towns of Cam Ranh Bay and Qui Nhon, they needed to be safely delivered to troops throughout the region, and the concept of gun trucks evolved out of this requirement. The winding roads to remote areas were in poor repair making driving very difficult, but as the cargo trucks slowly made their way down primitive tracks, they were also extremely vulnerable to attack.

To protect themselves, the transportation corps began to improvise shields against bullets initially in the form of wooden sides and sand bags. However, these provided little defense, and added unnecessary weight to the trucks which caused frequent breakdowns and significantly reduced fuel mileage.

Upgrades to Improve Mobility

The initial designs of the trucks were quite primitive, and desperate but resourceful soldiers used whatever materials that were available to them at the time. While the first gun trucks were converted from 2.5-ton vehicles built from pre-cut steel plating, they struggled on dirt roads riddled with potholes and often experienced mechanical problems. After a few months, switching to five-ton trucks addressed these issues by bringing more power and better handling. In addition, gun truckers made other smaller upgrades to the design of the vehicles to improve their efficiency. As well as causing rear suspension failures and other breakdowns the added weight of sandbags and two-by-four timber mounts had increased fuel consumption so these were eventually replaced with more sophisticated armor made from reinforced steel. To enhance overall performance, soldiers modified the technical components of the gun trucks with engine upgrades, improved suspension systems, and the installation of more powerful batteries to support the vehicle’s increased electrical demands.

As better materials became available, spare parts, extra features, and even weapons were scrounged by resourceful soldiers from the Air Force and other supportive services in Vietnam.

Customized Designs Support Enhanced Gun Mounts

As well as enhancing the 5-ton trucks’ armor with double-walled gun boxes made from steel, soldiers also focused on improving the firepower of gun trucks. This allowed vehicles to respond more effectively to enemy threats and contributed to overall mission success. Gun trucks were increasingly under fire but the larger vehicles offered more room for reinforced gun mounts and ammunition, and crews began to install additional machine guns, grenade launchers, and other weapons to bolster the vehicle’s offensive capabilities. Once the four-man crew was picked for each truck, a former Lieutenant Colonel remembers how commanders left the men to customize vehicles according to their own designs, adding extra features and machinery to create a more effective weapons platform to protect the convoy. Although only M60s were authorized for use on the trucks, crews used creative methods such as bartering to obtain other weapons, including the heavier M-2.50 caliber machine gun, the M134 minigun, and the M02.50-cal Browning, any of which could be added to the cab.

While painting the trucks black created an ominous and intimidating aesthetic, the dark color also offered effective camouflage and glare reduction which in turn boosted the operational security of individual missions.

By recognizing the limitations of gun trucks in Vietnam, the implementation of creative solutions focused on armor, mobility and fuel efficiency could significantly overcome these drawbacks and enhance the effectiveness of gun trucks in providing convoy security and battlefield support. Through the integration of technology, innovative design, and operational tactics, soldiers addressed the challenges of gun truck design, making them more resilient, versatile and ultimately capable of meeting the demands of modern warfare. These efforts not only increased the survivability and effectiveness of the gun trucks but also reflected the resourcefulness and adaptability of the soldiers in the face of challenging and dynamic combat conditions.

Here is the link to my original article about Gun Trucks:

Gun Trucks of the Vietnam War

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 30, 2024

Bernard Fisher Landed his Plane in the Middle of a Battle to Rescue a Downed Pilot

On March 10, 1966, a Special Forces camp in the Ashau Valley was surrounded and on the verge of being overrun. Air Force A1-E Skyraiders were sent to help end the siege. When one plane is shot down and rescue forces not readily available, one pilot took it upon himself to rescue his fellow pilot. Read his story:

It’s hard to know where to begin telling Bernard Fisher’s military story. No one could have predicted that a kid who joined the Navy at 18 to fight in World War II would eventually receive the Medal of Honor as an Air Force fighter pilot in Vietnam. No one would have guessed it would take the same man 57 years to receive his bachelor’s degree. That’s the extraordinary life of Col. Bernard F. Fisher.

[image error]

A native of San Bernardino, California, Fisher joined the Navy in 1945 at the end of World War II. When his time in the Navy ended in 1947, he attended Boise State Junior College and then transferred to the University of Utah—but he didn’t get to finish his degree. He joined the Idaho National Guard around the same time he began his higher education. In 1951, the same year he was supposed to graduate from college, he was commissioned in the United States Air Force.

To be clear, Bernie Fisher had done the classwork, and he earned a degree. He just never received it. It’s hard to blame him for not following up on a piece of paper. Fisher was ready to start training for one of the coolest jobs in the military: Air Force fighter pilot. He flew for the North American Air Defense Command until 1965 when he volunteered to go to South Vietnam and fly A-1E/H “Spad” Skyraiders for the 1st Air Commando Squadron.

Between July 1965 and June 1966, Fisher flew 200 combat sorties in the skies over Vietnam. The U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force used A-1 Skyraiders to provide close air support to ground forces, conduct interdiction missions, and perform search and rescue operations. The close-up nature of its missions meant it was particularly susceptible to ground-based anti-aircraft fire, so 200 combat missions was no small feat. No mission illustrated this kind of danger better than what happened on March 10, 1966. Fisher took off from Pleiku Air Base to make strafing runs against North Vietnamese forces assaulting a Special Forces camp in the A Shau Valley. The camp was surrounded by 2,000 enemy troops and cut off from its airstrip. Time was of the essence, as the special operators and their Civil Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) allies were in danger of being overrun. When he arrived in the area, it was under dense cloud cover, but other A-1s were loitering overhead.

[image error]

Fisher, his wingman, and two other pilots broke through the clouds to begin making their attack runs. The clouds and terrain made the strafing runs dangerous for the pilots, however. It limited their maneuverability and forced the aircraft to operate within range of enemy gun placements. One of the A-1s, piloted by Maj. Dafford Wayne” Jump” Myers took damage from those guns and began to go down. Myers bellied the plane down on the camp’s 2,500-foot airstrip, jumped from his plane, and retreated to the cover of an embankment nearby.

The enemy was just 200 meters from Myers, and the nearest helicopter was 30 minutes away. With 2,000 NVA soldiers surrounding the base, there was nothing the Special Forces could do to help the downed pilot. That’s when Bernard Fisher’s voice came over the radio. He told aircraft controllers he would land his two-seater Skyraider on the airfield and pick Myers up. While the Air Force warned him against that course of action, his fellow Skyraiders began giving him the cover he needed to land on the debris-strewn strip. It wasn’t an easy landing. Debris on the runway damaged his tail section, and despite the cover provided by the other pilots, he still took 19 rounds to his fuselage. He landed and taxied the entire length of the runway.

.[image error]

But none of the enemy attacks were enough to deter or prevent him from taking off once Myers had hopped in the backseat. With his charge picked up, Fisher gained enough speed to take off once more, with Myers safely along for the ride.

When Bernard Fisher returned to the United States in 1967, he received the Medal of Honor from President Lyndon B. Johnson for his daring rescue and his dedication to his fellow pilots. After the war, Fisher returned to flying interceptor missions in North America and Germany, retiring from the Air Force in 1974. But his story doesn’t end there.

In 2008, the University of Utah finally awarded Bernard Fisher his diploma in recognition of his academic and military achievements. Bernard Fisher died on August 16, 2014, at age 87. According to Fisher’s son, Bradford, Myers reportedly called Fisher every year on March 10 to wish him well. When Myers died in 1992, his daughter continued the tradition for 22 more years.

This article was originally featured in the TOGETHER WE SERVED Dispatches newsletter, March 2024. Here’s the link:

https://armydocuments.togetherweserved.com/newsletter/129/newsletter.html#article1

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 24, 2024

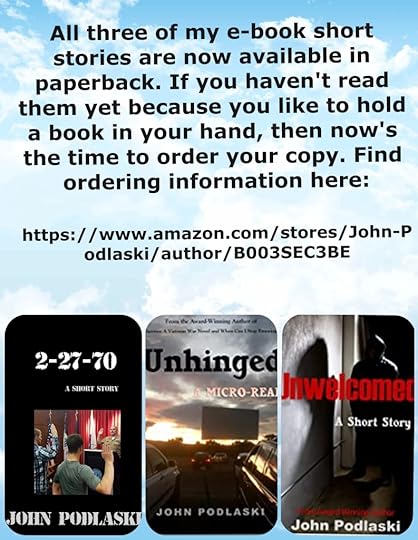

My E-Books are Now Available in Paperback

March 23, 2024

The Day the Marines Asked the Army for Help

On an October day in 1966, the sun rose in the west, a man was seen biting a dog, Hades reported ice storms—and the U.S. Marines asked the U.S. Army for help. Read what this was all about…

Okay, the first three things didn’t happen. But on that day when a man did not bite a dog, Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt, commander of the III Marine Expeditionary Force at Da Nang, Vietnam, called on Maj. Gen. John Norton, commander of the 1st Calvary Division (Airmobile) at An Khe, Vietnam, for help recovering four USMC H-35 Choctaw helicopters that had been shot down.

This is what happened next.

By MARVIN J. WOLF

On an October day in 1966, the sun rose in the west, a man was seen biting a dog, Hades reported ice storms—and the U.S. Marines asked the U.S. Army for help.

Okay, the first three things didn’t happen. Normally, the Marine Corps is the most self-sufficient of the armed services: Their infantry units, down to the squad, are larger than similar Army units; they can take more casualties but continue to fight effectively. The Corps has its own air element, both to establish air supremacy over the battlefield and for close support.

The CH-47 Chinook is a multipurpose helicopter that was often used to sling load heavy weapons, cargo, fuel in rubber tanks, and all sorts of military equipment. Photo courtesy of the author.

Nevertheless, on that day when a man did not bite a dog, Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt, commanding the III Marine Amphibious Force at Da Nang, Republic of Vietnam, called Maj. Gen. John Norton, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) at An Khe, Republic of Vietnam, to ask for help recovering four USMC H-34 Choctaw helicopters that had been shot down.

Powered by a gigantic piston engine, the Choctaw was big and heavy. Neither the Marines nor the Navy had anything that could lift it and carry it to a secure location for repair. The Marines had therefore developed a system for retrieving a salvageable H-34: They inserted a rifle company of some 200 Marines to provide security for a recovery team. The latter included mechanics to disconnect the downed bird’s heavy transmission from its engine, then disconnect the heavy engine from the airframe. After shrouding the transmission in a net of heavy rope, a USMC H-37 helicopter—also powered by a piston engine—would hover down and fly away with the transmission. It would return and take the engine. And then return again and lift out the rest of the aircraft.

Slow, to be sure. But that was the Marines dealing with their own problem.

Now no less than four H-34s had been shot down on the warm October morning in question. Four infantry companies were deployed to protect them. Lt. Gen. Walt had an entire infantry battalion of 800 fighting men tied up on guard duty, and he wasn’t happy about it. He asked Maj. Gen. Norton if he had a helicopter that could lift out an intact H-34.

Maj. Gen. Norton, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) at An Khe, Republic of Vietnam. Photo courtesy of the author.

Maj. Gen. Norton’s chief of staff called the information officer and suggested he dispatch one of his photographers to document this rare event. Maj. John Phillips, the information officer, was authorized no photographers. He had five information specialists, and one of them might have been able to handle a camera. But since he was not authorized a photographer, he was also not authorized a camera.

Fortunately, Maj. Phillips also had me. I, too, was an information specialist—then 62 days past my DEROS—date estimated return from overseas—and serving as institutional memory for a smart but very green information officer and his replacement crew. I’d spent the first six months of my Vietnam tour in the field taking combat photos with my own cameras while also teaching the other information specialists the rudiments of news photography. But by October 1966, those men had rotated home.Maj. Gen. Norton dispatched two CH-47 Chinooks so that if one was shot down the other could recover it. By mid-afternoon, I was on one of them.

At Da Nang our pilots consulted the weather gods and the Marines, calculated the maximum load that they could safely lift and fly away with, and came up with a plan: We would wait until sundown, when the air began to cool and become a little denser, providing more lift to rotor blades. And each aircraft would pump out all but 1,000 pounds of fuel. The math said that we could then lift and fly with an H-34 slung beneath us.

The first pickup went off flawlessly. I was dropped near the CH-34, positioned myself to take good photos of the Marine hook-up crew as they attached the rope net to our hovering Chinook, and then photographed the liftoff and fly-away.

The other Chinook landed and I got back on. As we headed for the second pickup, the flight engineer, a staff sergeant, beckoned to me. “Sarge, are you comfortable firing Ma Deuce?” he said. “Just in case?”

Ma Deuce was the WWI vintage M2 .50-caliber machine gun mounted in the left window. I spent my first three years in the Army as an infantryman and had fired Ma Deuce a few times. In Vietnam, the only way I could accompany troops into the field on a Huey with all seats full was to replace one of the door gunners. Months earlier I graduated from the Air Cav’s ad hoc door gunner school and then flew more than 100 combat missions as a door gunner, mostly in a Huey. But I had never fired Ma Deuce from a moving helicopter.

“I need to be on the deck talking to the pilots so they can make the pickup,” he added.

“Sure,” I replied. I moved to the window and checked that the gun was ready to fire, that there was a smooth path for the ammo to climb from its box into the feeding slot, and that the gun moved smoothly vertically and horizontally.

A mortar platoon is delivered to the battlefield by a CH-47 Chinook. Photo courtesy of the author.

In minutes we were descending toward the pickup.

With the flight engineer prone on the deck, peering through a tiny window and chatting with the pilots through his headset, I took up a watch, scanning the ground, near and far. Nothing dangerous in sight except 200 Marines.

I felt our ship slowly rising, taking the slack out of the cable connected to the hook by which the recovered bird was tethered. Then we began a slow left turn to align the centers of gravity of both aircraft.

Not 50 yards away, a man in“black pajamas” and a straw hat covered with sod stood up in his spider hole. He raised a 57 mm recoilless rifle to his shoulder and took aim. I lined up my sights and fired a short burst. My bullets landed short and skipped over his head

He fired.

Our Chinook shuddered. A fist-sized hole appeared 10 feet away on my side of the fuselage. Its twin appeared on the other side. The one on my side was a hand’s span from the engine. That’s the only reason my life didn’t end in a flaming explosion.

Before I could fire again, several Marines swarmed the man in black pajamas. Meanwhile, the flight engineer jumped up, whipped off his field jacket, pulled a Bowie knife from his belt, and cut an arm off the jacket. A roll of green duct tape appeared from somewhere.

Our pilots released the cable and the H-34 fell away.

I noticed that there was an inch of hydraulic fluid sloshing around on the deck.

Hydraulic fluid, I knew, was very flammable.

A badly damaged Chinook (on the ground) is recovered by a First Air Cav CH-53 Flying Crane. The Chinook was repaired and returned to service. Photo courtesy of the author.

In half a minute, the flight engineer found the severed hydraulic line, stuffed his jacket down it, and then taped it shut.

In the cockpit, our pilots were cursing aloud and struggling with the controls. I peeked and was astonished to see both pilots with hands on the controls.

Flying a big helicopter like a CH-47 requires the assistance of hydraulics to move external control surfaces. Without them, it’s like trying to handle an 18-wheeler going full speed on an interstate without power steering or power brakes. Except that a helicopter requires maneuvering in three dimensions, not two. So our pilots worked together, announcing each maneuver and together pulling or pushing the appropriate pedal or stick.

After a long, slow, flight we landed safely at Da Nang. Trailing the pilots, I walked around the bird, shooting photos and listening to them talk.

Apparently, the 57 mm recoilless had fired a HEAT round—high explosive, antitank. It was designed to pierce through the thick armor of a tank. The HEAT round had a soft nose that collapsed on impact to shape a charge that could pierce through the armor. All this, of course, in the blink of an eye.

A CH-47 Chinook based at the Army’s First Cavalry Division base, known as the “Golf Course,” lifts off with a 105 mm howitzer on a sling. At the bottom left is the gun crew. Photo courtesy of the author.

Our Chinook was not armored. A rifle bullet easily pierced the thin aluminum hull. So the HEAT round punched a hole in one side, flew across the interior, then punched a second hole in the other side before exploding. Exploding outside our aircraft.

The paint outside the exit hole was pitted and scorched.

We were very, very lucky.

And one more thing: Our aircraft was one of the first 100 delivered by Vertol, a division of Boeing. Upon delivery, Army pilots flew several test flights and decided that the hydraulic system, although built to original specifications, was inadequate. Rather than tear it out and replace it, Vertol installed a second system, designed to act in tandem with the first. The HEAT round had severed one hydraulic line, but quick action by our flight engineer limited the loss of fluid. With great effort, our pilots controlled our flight and landed safely. Without that second system, we would have been doomed to crash.

The second Chinook recovered the remaining Marine helicopters. Mission accomplished. By morning our Chinook had been repaired. Both aircraft returned safely to An Khe.

Lt. Gen. Walt was kind enough to send a letter of thanks to every man who flew the mission.

You’re welcome, Jarheads. Any time.

Marvin J. Wolf

Marvin J. WolfMarvin J. Wolf served 13 years on active duty with the U.S. Army, including eight years as a commissioned officer. He was one of only 60 enlisted and warrant officers to receive a direct appointment to the officer ranks while serving in Vietnam. Wolf has authored more than 20 books, including three about the Vietnam War: “They Were Soldiers,” “Abandoned In Hell,” and “Buddha’s Child.” He lives in Asheville, North Carolina, with his adult daughter and a neurotic, five-pound Chihuahua.

This article originally appeared on The Warhorse website on March 20, 2024. Here’s the direct link: https://thewarhorse.org/veteran-recalls-an-exception-when-us-marines-needed-army-aid/?mc_cid=9c5c7b677b&mc_eid=9693ec6f98

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 16, 2024

Identifying the Fallen

Ever wonder how the government can identify military MIA’s of our past wars? The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) is an incredible asset in the identification of recovered remains of American service members unaccounted for from our nation’s wars. The following is a DOD article on how they work.

Identifying the Fallen, Past & Present: Here’s How DOD’s Only DNA Lab Works Jan. 10, 2024 | By Katie Lange , DOD News.

Over the past several decades, most people have come to understand what DNA is – generally, it’s defined as the carrier of a person’s distinct genetic information. Since DNA was first used in forensic science in the late 1980s, it has opened doors for criminal investigators and genealogists to solve cases that have been cold for decades. For the U.S. military, it’s been essential in carrying out the age-old motto, “no one left behind.”

Today, the identification of fallen and missing service members comes down to DNA. The Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, which is part of the Defense Health Agency’s Armed Forces MedicalExaminer System, is the DOD’s only human remains testing laboratory. It performs DNA tests on service members who’ve died in current operations, as well as those who have been missing for decades. The lab works in tandem with the Armed Forces Repository of Specimen Samples for the Identification of Remains, which maintains millions of blood samples from folks who’ve served over the past 32 years.

Next-Gen Methods Help to Clear Cold Cases

The DNA Identification Lab — known as AFDIL — has two main missions, the largest of which is past accounting. This section’s nearly 100 analysts support the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency by providing DNA tests that support the identification of remains of service members who died in previous conflicts such as World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. The process begins out in the field. DPAA-trained anthropologists and archaeologists are sent to locations across the world to find the remains of service members where they were last reported to be. “It could be on the side of a mountain. It could be in a rice paddy. They do all of that recovery, then the remains go back to the DPAA labs,” explained Dr. Tim McMahon, AFMES’ DNA Operations director. “They will then start to sort those using anthropological methods.

The samples those experts procure are then sent to AFDIL, where analysts use an extensive set of tools to process them. One of those pieces of technology is called next-generation sequencing. For a long time, McMahon said the lab wasn’t able to test unknown service members from World War II and Korea whose bodies had been chemically treated during the embalming process because those chemicals didn’t fit with conventional testing methods. But now, thanks to advancements in next-generation sequencing generated by AFDIL, the lab can get results from chemically treated, highly degraded samples. “[A lot of] those bones have been in the environment for 80 years,” McMahon said. “When we extract that bone, we get bacterial DNA, fungal DNA, parasitic DNA, and the very degraded human DNA.”

A lot of the samples we receive have been exposed to a lot of really nasty environmental conditions. Sometimes they’re covered in jet fuel. Sometimes they’ve been burned, buried, or lost in salt water,” explained Katelin Hollowell, a DNA analyst for the past accounting mission. “All of those things factor into how much DNA is present in the sample and can be recovered.” With next-gen sequencing, analysts take the damaged DNA and bind it with human mitochondrial DNA RNA, which are ribonucleic acid probes that have a metal molecule bond to them. Then, using magnets, the laboratory can pull the damaged human DNA/mtDNA-RNA probe away from the non-human DNA. The mtDNA-RNA probes are used like bait to perform a process called enrichment.

“These probes are relatively human-specific, so they will bind predominantly to human [mitochondrial] DNA,” McMahon explained. “It allows us to enrich — or pull — that human DNA out of a vast pool of bacterial, fungal, and parasitic DNA that is commingled with our sample.”

McMahon said when they started the next-gen sequencing in 2016, they were able to do four samples a month with a 24% success rate. Now, they’re processing more than 100 samples a month with a 65% success rate.

“We’re still the only laboratory in the world that can do this,” the director said, although he made it clear that the lab is happy to share its cutting-edge methods with others across the country and world.

“We publish everything. We provide our results in our standard operating procedures if people ask for them,” McMahon said. “There’s no need for anyone to reinvent the wheel. The same work that we do for our fallen military members, if we can assist the local jurisdictions in returning these unknown human remains or cold case type scenarios to their loved ones, we want to get that stuff out there.”

Once scientists have been able to process a readable DNA sample from the remains, they’ll compare it to DNA from the families of missing persons. McMahon said the lab uses three genetic tests on DNA — mitochondrial DNA tests, which trace maternal ancestry; autosomal short tandem repeat tests, which can verify family connections (mother, father, brother, or sister); and Y chromosome short tandem repeat tests, which trace paternal lineage from male offspring. This means that the tests scientists can run will depend on the family member who donated his or her DNA for comparison. For example, if a sister of a service member donated her DNA, it would only get tested twice. If a service member’s brother donated, his DNA would be tested three times.

“Because they had the same mother, [that brother] has the same mitochondrial DNA as the missing service member,” McMahon explained. “Because they shared the mother and father, we can use that nuclear or autosomal short tandem repeat to determine that they’re siblings. And then, because he shared the same father, that brother has the same Y chromosome as the missing service member. So, a brother, we’d have to test three times.”

Crucial For Comparison: Familial DNA References

How, exactly, do experts get DNA from family of missing service members? Those samples can be acquired in one of two ways. The first is through genealogical searches, which are conducted by service casualty office representatives to find family members of missing persons. Once family members are identified, those representatives send them a kit to do a cheek swab to donate their DNA. The families then forward those samples to the DNA Lab for analysis.

The second way samples are collected is through DPAA-hosted regional family member updates, which are held a few times a year for families of missing service members.

“The family member updates are where family members of our missing heroes get briefings from their service casualty officers, DPAA representatives, and AFDIL,” McMahon said. “I interact with the families by giving a DNA update, and then we will actually collect references in person from eligible family members.”

The samples are then entered into a family reference database. McMahon said the database currently maintains DNA from relatives of 92% of the original 8,157 service members missing from Korea and from relatives of 86% of the original 2,641 Vietnam-era missing service members. For World War II, he said, it’s a little more complex.

“If you take the original 73,678 World War II missing, AFDIL has family reference samples on file for 17% of the missing service members,” McMahon said. However, he clarified that they have a higher percentage of family references for specific battle sites. “At the Battle of Tarawa, there are 486 service members still missing in action. For those 486, active recoveries are going on in Tarawa, and I have an 88% coverage of references.”

For service branch representatives, getting to know the families of the missing is part of the job. “I’ve talked to these families a lot over the years, so I know a lot of them,” said Allen Cronin, the past conflicts branch chief for Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations, which leads the effort to identify service members for the Air Force. When a missing service member is positively identified, representatives such as Cronin notify the families and work with them on their wishes for their loved one’s burial. They also travel with DPAA and DNA Lab experts to the families’ homes to present the details of how experts came to their conclusions.

“There are a lot of questions that some [family members] have, and I can’t answer them. I’m not a scientist – I don’t do DNA,” said Cronin of his role as a service casualty representative. “So, I ask the director next door [at the AFMES DNA Lab] if I can take the person who made the identification with me. Then, sitting there with the family, I don’t have to say, ‘Well, I’ll go back and see if I can get the answer.’ They’re going to get the answer right there.”

According to the DPAA, in the fiscal year 2023, the agency recovered the remains of 127 service members: 88 from World War II, 35 from Korea, and four from Vietnam. Nearly 81,000 American service members remain missing.

Identifying Our Current Fallen

The DNA Identification Lab’s second mission is current-day operations, which supports AFMES forensic pathology investigations division work in identifying service members and civilians who die in current theaters of operation, during training, or on land under federal exclusive jurisdiction.

For AFMES, any case that comes up after 1991 is considered a current-day operation. That’s when DNA began to be more commonly used to identify people in the U.S. It’s also the year the first Gulf War occurred. There have been no missing service members since. All military personnel and deployable contractors since 1991 have a DNA blood reference card on file with the Armed Forces Repository of Specimen Samples for the Identification of Remains. McMahon said they log about 200,000 new cards a year and have more than 9 million cards on file.

“They’re used for the identification of that service member if they’re killed in a current theater of operation or training accident,” McMahon said. However, because the cards are considered a medical record and are maintained for 50 years from the date of collection, They can be used otherwise, as well.

For example, if we have a retired service member who passes away and the local jurisdiction can’t do fingerprint or dental [identification], and there are no living relatives to provide a DNA reference, AFDIL may be able to assist in the best interest of the service member,” McMahon continued. “If their crime lab develops a DNA profile from those unknown human remains and sends it to me, I can pull the card. I will process it here to make the comparison. If they match, I will issue them what we call a ‘believe to be’ report with a statistic. But we do not release the DNA profile information.”

Analysts say the current-day samples are fresher and better quality than most of the DNA samples tested in past accounting. They’re more like those tested in a crime lab.

“They’re usually easier to process and get a quick turnaround time of ID, which is what the families want,” said Miranda Frady, a DNA analyst for current-day operations. “It’s streamlined. We have a process that works for us, and we try to get those out as quickly as possible to the medical examiner.”

Frady, who has been at the DNA lab for a decade, said the work is incredibly rewarding.

“These loved ones have given the ultimate sacrifice, so it’s very important for me to be able to bring that information back to their families,” she said. “I play a small part in helping to provide some closure for them.” Current-day analysts also help with peacetime losses, such as the 1952 crash of an Air Force C-124 on Mount Gannett, Alaska. That joint mission is known as Operation Colony Glacier. It involves a team of service members and civilians who travel to the wreckage every June to conduct search and rescue operations.

“We’ve been doing recoveries there since 2012,” McMahon said. “Our [current day] DNA section has assisted the medical examiners with identifying 47 of the 52 missing.” “We also help military law enforcement agencies, other federal agencies, and military hospitals,” Frady explained. “In the event of a mass fatality or something like that, we can provide DNA testing.”

Short film relating to the annual Colony Glacier search and rescue efforts:

https://d34w7g4gy10iej.cloudfront.net/video/2206/DOD_109044303/DOD_109044303-1280x720-3000k.mp4Quality Control is Key

While Frady, Hollowell, and their colleagues work on DNA samples, other analysts, such as Ashley Doran-Roth, do behind-the-scenes work in quality control to make sure the lab’s instruments and reagents – the chemicals and kits needed to test samples — are working properly so successful identifications can continue.

“If something breaks down, we have to go and fix it,” Doran-Roth said. “We’ve got to make the reagents, label them, deliver them to the labs, and track everything.” She said the day-to-day for QC analysts often changes based on what’s going on in the world and what types of samples are being tested the most.

“For example, when 9/11 happened, [the lab] helped a lot with identifications there. So, we have to … figure out, ‘OK, we have more of this type of sample. We need to do these kinds of reagents,'” she explained.

The overall mission at the DNA Lab is some of the most important work that can be done for service members and their families – bringing closure when it’s needed. “We all work together — I think that’s the important thing,” Doran Roth said. “Even though we’re in different sections, we’re all intermixed, and we all help each other to do this common mission, which is to bring home our service members.”

This article originally appeared in both the Vietnam Veterans of America, Chapter 154, February 2024 monthly newsletter titled, “THE BOOCOO NEWS” and the DOD website:

If you want to read more about Digital Archaeology and locating MIA’s from the Vietnam War, read this: https://kjzz.org/content/1871136/asu-professor-using-new-tool-find-missing-us-soldiers-vietnam-war-digital-archeology

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 9, 2024

Welcome Home

As a veteran, how do you feel when a stranger approaches and says WELCOME HOME or THANK YOU FOR YOUR SERVICE when out in public? Here’s one man’s take on it:

By Robin Bartlett

The phrase ‘thank you for your service’ started to be used in the late ‘90s. It became even more popular in recognition of the heroism on the part of firefighters, police, and first responders in the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11th and the War on Terror that followed. The saying is commonly used today to greet all veterans and active-duty soldiers as well as politicians and first responders. It is the “phrase du jour” for Veterans Day (originally Armistice Day) honoring those who served in the military, and Memorial Day (originally Decoration Day) honoring those who made the ultimate sacrifice in defense of their country.

But some veterans, especially Vietnam veterans, feel that the phrase is overused, and may even find it offensive. These men interpret the words as meaningless sentiments such as “Have a nice day” and react with a quiet, modest “thank you” all the while thinking they have no true understanding of the meaning of those words.

If you were a combat veteran in Vietnam, humped the boonies for a year, and placed your life on the line every day in service to your country, you often believe your actions deserve more respect than what is so commonly communicated by thank you for your service. Many Vietnam veterans believe that saying those words alleviates the civilian guilt for not having served. A common belief within my group is while I was humping the jungle and eating C-rations in that God-forsaken country, you were eating french fries in the food court at the mall.

An Uneasy ThanksAccording to a Cohen Veterans Network poll commissioned in November 2019, 49% of veterans don’t actually like to be thanked and are uneasy with the expression thank you for your service.

Here is a quote from my book with permission given by Robert Flournoy from a Facebook post, Reflections of an Artillery Forward Observer with an Air Cav Rifle Company:

“Many of us arrived in Oakland 12 hours after leaving a fire base, some after walking point on a patrol, still wearing the red dirt of that duty, and were on the streets in civies a few hours later with some travel pay to make their way back to Ohio, Alabama, or New Jersey. And when the hugs and tears of our families were done with, we would look around, somewhat bewildered, with a head full of “what now?” Ensuing nights filled the mind with sounds of popping flares, and hammering of an M-60, the constant boom of artillery and the whop whop whop of Hueys coming and going, left us dazed and confused to have left all that behind so suddenly. Many of us sank into silence, most tried to explain our experience to uncomprehending parents, and spouses. So many sought the solace of fellow vets at the local VFW or Legion Hall, usually accompanied by liquor which too frequently led to loud, aggressive behavior. How many of us wanted to go back? Back to the jungle, to the fire bases that we hated, but where likeminded men with singular purpose treated us like brothers, silent respect and understanding hanging over us like a warm blanket. Our homecomings were, all too frequently, the beginnings of frustration and despair.

Yet, most just moved on, putting it all behind us. Regardless of how we handled the homecoming, there was never a welcome home feeling from our country much less from the people who never served. We didn’t look for it, expect it, or even think about it. It was a non-issue. So, Vietnam vets became an obscurity in the landscape of America, an awkward presence that most vets acknowledged with their own silence. But, decades later, when old ghosts started creeping out of their closets, and the wisdom of age made its way into their reflections, combat veterans from the Vietnam war began remembering their experiences in softer toned colors, instead of the garish bright reds and oranges that they brought home with them. A kind gentleness emerged as they sought their brothers from long ago. The greeting “welcome home” emerged not as a resentful “we never got a proper welcome”, but simply as a soft nod of the head to those who made it back so long ago. Two simple words that belong exclusively to them and their kin; brothers who know – as only they can know. Those men own the words, another right shoulder patch seen only by those who also wear one there.”

Vietnam vets are a special breed. We come in many shapes and colors. You will notice more and more of us these days as Vietnam veterans begin to walk in the boots of their WWII and Korean brothers. Some proudly wear ball caps denoting the unit in which they served with pins showing their decorations. Our hair is going grey. We have wrinkles on our faces, and some suffer from the ravages of age, battle wounds, PTSD, the scourge of toxic burning and Agent Orange. But as our numbers gradually decrease, just as our brothers in previous wars have faded, we ask only for a few kind words of acknowledgment that we served to protect the freedoms and life you now enjoy.

A Game changerWhen you meet us, I encourage you to greet us with a phrase that shows you truly care and have a deeper understanding of those of us who served in our war. There is nothing wrong with saying thank you for your service and it is sincerely appreciated by most veterans. But if you want to tell us that you honor our sacrifice, bring lumps to our throats and tears to our eyes, say Welcome Home and watch the reaction. It’s a game-changer. How do you feel about it? Leave your comments below.

ADMIN: PERSONALLY, I LIKE “THANK YOU FOR YOUR SACRIFICE” WHICH COVERS NOT ONLY MY SUFFERING IN VIETNAM BUT ALSO WHAT I HAD TO ENDURE AFTER MY RETURN HOME.

Robin Bartlett has contributed earlier articles to this website. See below:

The Trail – A short video

Helicopter Combat Assaults:

https://wordpress.com/post/cherrieswriter.com/22329

Here’s my book review of Robin’s book, VIETNAM COMBAT: FIREFIGHTS AND WRITING HISTORY:

Book Titles V – Z

If you wish to visit Robin’s website, here’s the address to his blog:

https://robinbartlettauthor.com/blog/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 2, 2024

THE VIETNAM INTERVIEW: A DATE WITH CHRIS NOEL

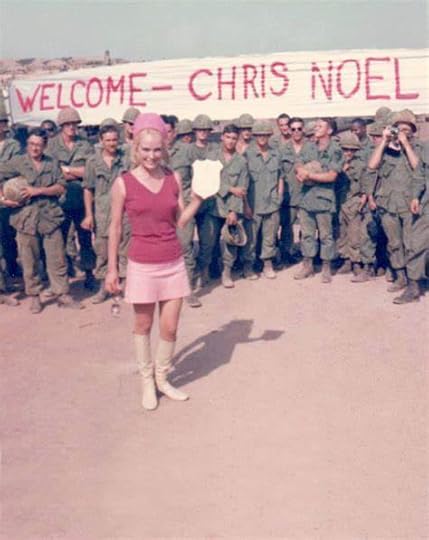

During the Vietnam War, Chris Noel, an American actress and radio personality, played a significant role in boosting the morale of American military personnel. She visited Vietnam eight times, entertaining troops and providing emotional support.

Chris Noel’s dedication to lifting the spirits of soldiers during a challenging time is truly commendable. Her impact extended beyond entertainment, as she brought comfort and a sense of connection to those serving far from home. How many of you remember her?

When Hollywood turned stridently against the Vietnam War and the men who fought it, Chris Noel stuck with the GIs – and she’s still with them. Don’t miss the current-day video with Chris at the end of this article as she looks back to those days gone by.

By CLAUDIA GARY AND DAVID T. ZABECKI

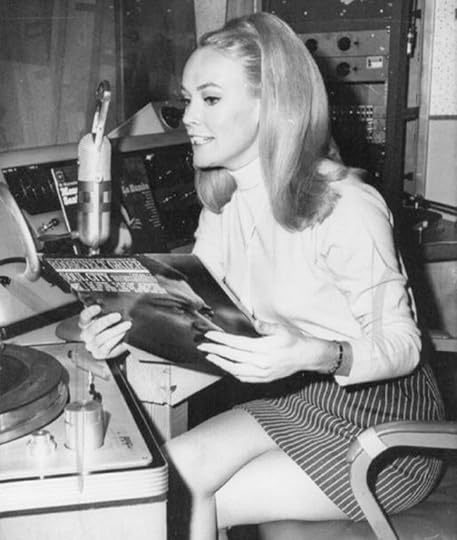

A model turned actress in the early 1960s, Chris Noel was a young blonde bombshell with several movies and TV guest appearances under her belt when she first started entertaining the troops in Vietnam. She received the Distinguished Vietnam Veteran Award in 1984 from the Veterans Network for her work during the war. In an interview, Noel recalls her life-altering experiences and her ongoing efforts in support of Vietnam veterans.

Vietnam: Tell us a little about your Hollywood career before Vietnam.

Chris Noel: When I first went to Hollywood, I was put under contract to Universal for one month, and then they fired me. Their head of casting said I had the worst voice in the world, and said to “send that girl back where she came from, she’s atrocious.” So I cried a lot, until three weeks later I was under contract to MGM. In the first film I did I played the girlfriend opposite Steve McQueen, in Soldier in the Rain. Jackie Gleason and Tuesday Weld were in the film. I guest-starred in almost all of the television shows of that year. I did a lot of beach movies and motorcycle movies, and just a little bit of everything.

And before Hollywood?

When I was in Florida as a young girl, at the age of 16, I was on the cover of Good Housekeeping magazine with a little baby, posing as a young mother. I was also the Kodak girl. There were wonderful posters that were done on the beach with me in a hammock, and with a beach ball, and that sort of thing. But I just knew that I had to do something more with my life, so I went to New York. A television writer did an article where they picked the three top women in television commercials and three top guys, and I was one of the three girls. Then I was also one of the Rheingold [beer] girls in New York, and on the cover of the New York Post and New York Mirror. But I always wanted to go to California.

What was the turning point for you?

The 1965 Christmas tour that I made with California’s Governor Pat Brown and various celebrities. That year, my boyfriend was over in Vietnam with Bob Hope. Then I had the opportunity to go to the VA hospitals. When I went into the gangrene ward of double and triple amputees, I was stunned. I remember the very first guy I saw there said something really nasty to us. Then Sandy Koufax took and threw a ball to a guy who had only one arm, and he reached up and caught the ball. He was laughing, and the other guys were laughing. I thought, “Wow, I have to find a way to learn to make them happy.” My girlfriend and I sang “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,” and we were absolutely terrible, but it was kind of cute. When I walked out of the ward, I was still very, very stunned. Those moments changed my life and made me realize that I had to make a difference.

How did you get the disk jockey job with Armed Forces Radio?

My boyfriend came back from his tour and he had to put in Reserve time. He was at the Armed Forces Radio and Television Service in Hollywood, and he found out that they were looking for someone to put on the radio. So I called, made my appointment, went in and did my interview—and they chose me. I started off doing a show called Small World with George Church III. I became really popular. The colonel called me in one day, and said, “Well, Chris, I hate to tell you this, but you’ve been fired.” I said, “Fired? What did I do wrong?” And he said, “Well, you’ve been fired, but you’ve been hired to do your own show.” It was pretty exciting. They came up with the name, A Date With Chris. They would record it to be put on 33-1/3 records, which would be sent to all the outlets throughout the free world.

Did you ever meet Adrian Cronauer?

During the Vietnam War, several people had a radio show for the U.S. troops there. Adrian Cronauer was not the original. I met Adrian back here after his movie was done.

What did you think about your radio show being called America’s answer to Hanoi Hannah and Saigon Sally?

Something that just blew me away was when Hanoi Hannah stated that she really didn’t know how the GIs all felt about her until she got a video of the movie Good Morning, Vietnam! Isn’t that weird? I never really knew what Hanoi Hannah looked like until 2007, when CSPAN was showing an interview with her. It was fascinating. I had heard just a tiny bit of her voice a couple of times in Vietnam, but usually, I was so busy that I wasn’t really tuned in to her.

How did you get on Bob Hope’s tour?

After I started my radio show, I knew that the holidays were coming and Bob Hope would be going back over again. I asked, “Is there any way that you could get Bob Hope to let me go with him to Vietnam?” The answer came back: No, I wasn’t considered a big enough star to go with him. But a few weeks later I got a telegram from the Pentagon asking if I would go over and entertain the troops.

How was your first trip to Vietnam?

The first time I went over was in December 1966. I was very excited, but I didn’t have the foggiest idea of what to do, because all I knew was how to be an actress on radio and television. I took a portable record player with batteries and a little record case. I think I had the top 100, or maybe only the top 50 songs. They said, “You’re going to be there at Christmas time, so take some kind of Santa Claus outfit.” I was only being paid $200 a week by MGM, so I didn’t have a lot of money. I went to Hollywood Boulevard and I saw a little silver miniskirt and a little silver top, and that’s what I bought for my Santa Claus outfit.

They sent me to one of the bases to get my shots, and I had to stand in this line, just like all the guys. I had never been anywhere outside of the United States except one time to Mexico. When we landed in Vietnam and I walked down the steps at Tan Son Nhut, it was stifling. They took my suitcase and we got into a van. The windows were open, but there was mesh on the windows, which they said was to keep grenades out.

What was it like being on Bob Hope’s 25th Anniversary show in Cu Chi on December 25, 1966?

My escort officer said to me: “Chris, Bob Hope is going to be doing a show on Christmas Day. How would you like to be in his show?” I wasn’t very far away from Cu Chi, so they just helicoptered me in. When I first got there so many cameras were clicking, it sounded like a field of locusts. We went to this tent, and they had fans going, makeup artists, and hairdressers. Some GI had given me a poem, something about the Night Before Christmas, only it all had to do with the Vietnam War. It was that whole poem I did onstage.

I kept hearing all of these show business people complaining—they complained about everything! They complained about how hot it was—“I can’t go out there if I’m sweating like this,” and “You must do something better with my hair.” I’m sitting there thinking, my gosh, I can’t stand these people! They’re all just prima donnas. They don’t have the foggiest idea of what it’s really like over here. They’re in air conditioning as much as they can, and they’ve got the best of everything, and all they do is complain!

How was it to work with “Colonel Maggie,” Martha Raye?

I had been up north for several days and was back in Saigon, and I was very, very tired. I was so happy to think that I was actually going to have a bed, and could lie down behind a closed door. When I got to the hotel I remember being told that Martha Raye was there. I walked in, and there was Martha with three Green Berets. Someone introduced us and we talked for just a second, and she said, “Get it together, girl, you’re having dinner at the camp with the boys.” I said: “I just got here! I’m not going to eat any dinner, I’m not doing anything!” She said: “Oh, yes, you are! You get it together because you’re having dinner with the boys.”

When we first got to Camp Goodman, we walked into a mess hall that had a kind of platform and a very long table. Nobody else was in the room—just four of us. The food was brought in to us. I was talking a little bit, and then the captain sitting next to me very meanly looked at me and said: “What are you doing here? We all know what Maggie is doing here, but what is it that you’re doing here?” I looked at him and was almost speechless. I said: “I’m doing the same thing Maggie is. I’m here because I care. I was asked to be here.”

Then a lieutenant who was there, Ty Herrington, said, “Miss Noel, would you like to see our camp?” I felt as if he was on a white horse saving me, and I said, “Oh, yes, yes!” He took me around and showed me the camp a bit, and then he opened the door to his room. There was a picture of a woman in a silver frame. I said, “Oh, that must be your wife!” And he said, “My mother wishes she were.” Shortly after that day, he became my escort officer. After a couple of more tours, we fell in love and we got married. As it turned out, the woman in his picture was his wife! He had lied to me.

Some big acts were restricted to base camps for security, but you sometimes went alone to the more isolated firebases. What was that like?

I’m so thankful that I was able to have that opportunity—to just drop down out of the sky in a helicopter, and to see the guys come out of the boonies, exhausted, and already with that stare in their eyes. I feel really blessed that I could be there for a few moments with them, just to sign some pictures, to say hello, just to let them know that, yes, people do care about you. Along with Maggie and a few female war correspondents, I was one of the only women who ever traveled the entire scope of South Vietnam. I really think I got to have one of the most incredible experiences, to see that it wasn’t the same war for everybody.

You kept doing this even though the Viet Cong had a $10,000 bounty on your head and you had a fear of heights?

I didn’t think they’d ever really get me. I felt really protected. And once I started getting into those helicopters, I just loved it. What’s weird is that now, when I get into helicopters, I freak. Back then, one time the hydraulic system went out in a helicopter and we went down…that was scary.

Did your helicopter ever come under fire? Were there any close calls on the ground?

I only remember one very serious time in a helicopter, while trying to leave a mountaintop. Being in places that were being mortared—maybe three times. And groundfire—maybe twice.

You are a hero to GIs, but in show business, openly supporting the troops was the equivalent of professional suicide. How did you keep doing the hard right over the easy wrong?

Whenever I talk to young people, I always leave them with one thought: Do the right thing. Actually I never really thought of it that way, but when I started hearing it a lot—“do the right thing”—I realized that that’s how I went along in my life, just always trying to do the right thing. I cannot imagine anybody having grown up in this country ever betraying it. Yet I’ve met so many people who are somewhat like that. And I’ve had to endure their conversations and sit there politely, and excuse myself when the time was up.

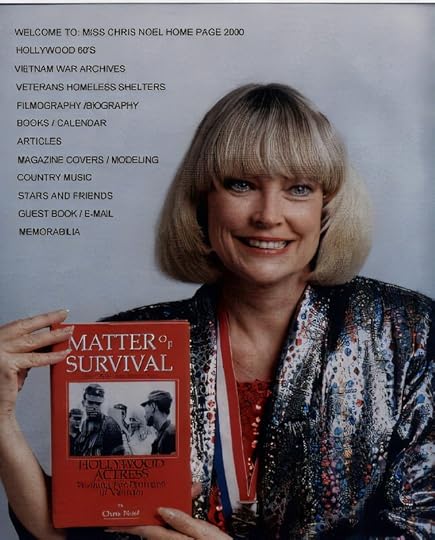

Your book A Matter of Survival is subtitled The War Jane Never Saw. How could you and Jane Fonda, coming from the same Hollywood culture, see things so differently?

I went to see a psychiatrist in New York who was doing work with PTSD, and I was just hoping that maybe she could help me because I really needed some help from somebody. Something came up about Jane Fonda. The doctor looked at me and asked, “How can you possibly even consider yourself in the same breath? She was born with a silver spoon, and you weren’t. Why would you even bring her up? You don’t have anger against her, you just have anger, period, and your own hostility. You’re just using her as a catalyst.”

I was in a pretty fragile state as it was, and I thought to myself, “Man, then if I have these thoughts that are so misdirected, are you trying to say to me that all these thousands and thousands of men and women who know the truth about Jane Fonda and feel the same way that I do—that we’re all screwed up? That she was fine, but we’re all the ones who are screwed up?”

Did you ever meet with Jane Fonda?

Yes. In the 1970s a girlfriend said, “Come on, I’m going to this event—Jane Fonda is talking, at Warner Brothers Studio.” They had it set up in a big room. She was talking, and I was thinking, “I can’t believe I’m here listening to all of this.” So finally, I stood up and told her: “I don’t even know where you’re coming from. How can you say these things? You know, you went over to the enemy side in the Vietnam War, and I didn’t. I stayed with our troops, which I felt was the honorable thing to do. How can you live with yourself, having done what you did? And how can you be saying today all the things that you’re saying about our government and the oil industry? I can tell you right now, that I’m married to an independent oil producer, and it’s costing him more money to get the oil out of the ground than he’s getting for it. He’s losing everything that he owns and he’s going under. And I’m sitting in this room, listening to these disgusting things that you’re saying. You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

She said: “You and I need to talk. Would you come up afterward? Because you and I just need to talk.” Well, that went nowhere. Everybody in the room looked at me like I was some kind of lu-lu.

You married Ty Herrington, whom you met in Vietnam, but that went terribly wrong?

Ty Herrington was a very charming, good-looking guy. I was madly in love with him, and it was so incredibly romantic. I was this Hollywood star, and he was this warrior. He was able to slip out of Vietnam a couple of times. I met him on R&R in Hawaii.

Then we decided to get married, but things started happening right before we got married, things that scared me. I realized that something was very, very wrong—but I went ahead and married him anyway. It was a horrible mistake. He used to put a gun to my head, and a knife to my throat, and he used to strangle me until I passed out. He would get this look in his eyes. I was scared, but I didn’t know how to get out from underneath it.

We moved to Nashville because he had a contract with Monument Records. They recorded him singing “When the Green Berets Come Home” and “A Gun Don’t Make a Man”—isn’t that something? I was able to get him to go see a psychiatrist once. The psychiatrist told me that he was a paranoid-schizophrenic manic-depressive and that he was very dangerous. Then one day he put a gun to his head and he was gone.

You have remained a tireless supporter of Vietnam vets, with projects such as the Vetsville Cease Fire House you founded in 1993 in Florida to help homeless veterans.

I was living in Palm Beach at the time and married to a lawyer. I would go to United Way meetings and talk about the fact that we needed to do something for homeless vets. People would laugh at me: Here’s this movie actress talking about homelessness—what does she know? All they seemed to care about were all the people coming in from other countries. They didn’t care anything at all about the homeless vets. I finally concluded that none of these people were going to do anything but make fun of me and I would just have to do it all by myself. I woke up one day and said: “That’s it, today’s the day I’m going to do it.” By the end of that week, I had a house in Riviera Beach, the roughest area in the entire town. At our opening ceremony, a neighbor walked over to see what was happening. Then he offered me the use of a house he owned that was right next to ours, and he wouldn’t take any money for it. Within about five months he went into foreclosure and lost all of his property. I went to the bank and made a deal to buy his two houses. So now I had three houses there. That’s how it all began, and then it expanded.

And now this project of yours has grown beyond Palm Beach?

Pretty soon we were in three cities, and I had people calling me from different places in the country, wanting me to help them. I don’t take government money. I did in the beginning—I applied for grants, and I did get them, but I don’t have any grants anymore. I just work really hard and have a fundraiser and do a mail-out to try to raise some money to keep the program going.

We are now in another muddled war that the American people are turning increasingly sour on. But so far they haven’t turned against the GIs sent to fight it. Why do you think it’s different this time?

I don’t think it’s different this time. I think they’re just keeping their mouths shut. I have found that if you ask anybody who tells you they were against the war in Vietnam, they will all deny having said anything bad about the GIs. Not one person has admitted to spitting on a GI or calling them names. I think that’s because the Vietnam vets suffered so greatly from the attacks against them, and there was so much emphasis on the reality of PTSD. But I believe that people still have the same thoughts that they had during the Vietnam War.

The only difference is that now it’s become so politically incorrect to say anything negative about the warrior—but they don’t really support the warrior. They’re not the ones who are sending letters over; they’re not saying great things about them. They just pretend that they support the troops but not the war. They may not admit it, but deep in their souls that’s the way they feel. They’re not going to invite GIs to dinner, or invite them over to their home when they come back, or be really good friends with them, or go to any of the veteran functions. Anyway, that’s my personal opinion. I really don’t think it’s changed.

So many of those fighting this war are children or, in some cases, grandchildren of Vietnam veterans. What more can be done to ensure we take better care of these new veterans?

Just keep fighting for them. Just keep fighting for the veterans’ issues. Keep fighting to make Walter Reed a better hospital—with more doctors. Sometimes our vets are fortunate, and they get a really good doctor; at other times, they are not so fortunate.

What enduring lessons did you gain from your experience during the Vietnam War?

I just think that war is hell, no matter who is fighting or where the wars are. But I think sometimes you have to have war to have peace. I mean, I’m just a retired movie actress. What do I know? I just keep fighting for what is my truth, trying to make it a better world for as many people as I come in touch with. I try to give the best of myself whenever I’m around other people and try to be the best person I know how to be.

Claudia Gary is senior editor of Vietnam magazine. David T. Zabecki is senior military historian for Vietnam and all of World History Group’s other magazines. For more about Chris Noel and her work, see www.chrisnoel.com.

This article originally appeared in THE VIETNAM WAR MAGAZINE on 6/12/08. Here’s the direct link:

The Vietnam Interview: A Date with Chris Noel

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

February 24, 2024

WHAT IT WAS REALLY LIKE AS A MEDIC IN THE VIETNAM WAR

BY NATASHA LAVENDER

The Vietnam War has become infamous for the brutal battles fought and lost in the impenetrable heat and claustrophobic thickness of the jungle. Following American soldiers into the line of fire, hoping to prevent them from becoming yet more casualties, were their medics. It’s estimated that 10,000 Army Medics and Navy Corpsmen served in Vietnam during the war.

Medics trained alongside other troops, but their job in the field was to patch up their comrades when the bullet, grenade, or shell with their name on it found its target. Without body armor or even bulletproof helmets, medics were in as much danger as their comrades — and sometimes more. While soldiers could hunker down during bombardments, the medic ran towards the enemy to find the wounded, often with little more than a few bandages, some morphine, and a pair of blunt scissors, and little to no medical training.

Even when the guns were silent, medics were in charge of soldiers’ general health, treating them for diseases from malaria to foot rot and unwelcome souvenirs picked up at brothels. This is what it was really like as a medic in the Vietnam War.

SOME MEDICS SIGNED UP BUT OTHERS WERE DRAFTED

According to official United States government statistics, 1,857,304 men were drafted through the Selective Service during the Vietnam War (specifically between August 1964 and February 1973.) After completing basic training in bases around the U.S., some were assigned as combat medics and transferred for ten weeks of medical training, often to Fort Sam Houston in Texas. Most had no previous medical experience. The assignment was simply the luck — or bad luck — of the draw.

Other people who became medics volunteered. Beating the army to the punch and signing up instead of waiting to be drafted gave you more control over which area you worked in. Some volunteer medics saw the job as a way to serve their country, while others believed it would be an opportunity to get medical training they otherwise couldn’t afford, as Vietnam combat medic Rafael Matos wrote in The New York Times.

Becoming a medic was also an option for conscientious objectors who had been drafted. You had to apply for conscientious objector status when signing up for the draft. If your application was denied, and you still refused to fight, you could be sent to military prison, as Vietnam combat medic Ben Sherman found out. Fortunately, his captain felt that having a soldier who refused to fight would not be ideal in a battle situation and persuaded the Pentagon to issue Sherman conscientious objector status and assign him as a medic.

MEDICS WERE BOTH DIFFERENT AND SIMILAR TO OTHER SOLDIERS

Like other soldiers, combat medics were trained in fitness drills, firearms (unless they were conscientious objectors), and how not to get shot. Medical training lasted ten weeks and revolved around triaging battle wounds.

Vietnam combat medic Stephen Dunn recalled learning “how to give shots, bandage and carry the injured, apply tourniquets and morphine.” Fellow Vietnam combat medic Roger Buchta said medics also learned how to treat shock and administer an IV, as well as basic anatomy. After that, the medics worked at base clinics until receiving their orders to deploy to Vietnam.

Unlike in other wars, Vietnam medics carried weapons. According to We Are the Mighty, most had an M16A1 rifle, a .45 caliber pistol, and grenades. Like the infantrymen, they didn’t have body armor or bulletproof helmets.