John Podlaski's Blog, page 5

December 21, 2024

Pics from 50+ Years Ago in a Country 10,000 Miles Away.

December 7, 2024

The ambush of Team Rock Mat

Find out the tragic story of Team Rock Mat, a US Marine Corps recon unit in Vietnam that had a strange encounter in the jungle one night in May 1970. There are a thousand ways to die in Vietnam…this was one of them. Don’t miss this 5 1/2-minute video.

I never saw a tiger in the bush, but we’ve been routed by wild Boers, Cobra snakes, pythons, rock apes, and water buffalos while on patrol or in our night defensive position. What about you?

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

December 1, 2024

The Pentagon Papers

With the Pentagon Papers revelations in 1971, the U.S. public’s trust in the government was forever diminished. What did they contain? If you are a Vietnam Veteran, this should upset you. Read this eye-opening account:

This article is part of a special report on the 50th anniversary of the Pentagon Papers.

Brandishing a captured Chinese machine gun, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara appeared at a televised news conference in the spring of 1965. The United States had just sent its first combat troops to South Vietnam, and the new push, he boasted, was further wearing down the beleaguered Vietcong.

“In the past four and one-half years, the Vietcong, the Communists, have lost 89,000 men,” he said. “You can see the heavy drain.”

That was a lie. From confidential reports, McNamara knew the situation was “bad and deteriorating” in the South. “The VC have the initiative,” the information said. “Defeatism is gaining among the rural population, somewhat in the cities, and even among the soldiers.”

Lies like McNamara’s were the rule, not the exception, throughout America’s involvement in Vietnam. The lies were repeated to the public, to Congress, in closed-door hearings, in speeches and to the press. The real story might have remained unknown if, in 1967, McNamara had not commissioned a secret history based on classified documents — which came to be known as the Pentagon Papers.

By then, he knew that even with nearly 500,000 U.S. troops in theater, the war was at a stalemate. He created a research team to assemble and analyze Defense Department decision-making dating back to 1945. This was either quixotic or arrogant. As secretary of defense under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, McNamara was an architect of the war and implicated in the lies that were the bedrock of U.S. policy.

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara addressed reporters at a news conference on Sept. 7, 1967. Two months earlier he had created the task force that would compile and write the Pentagon Papers. Credit…Associated Press

Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara addressed reporters at a news conference on Sept. 7, 1967. Two months earlier he had created the task force that would compile and write the Pentagon Papers. Credit…Associated PressDaniel Ellsberg, an analyst on the study, eventually leaked portions of the report to The New York Times, which published excerpts in 1971. The revelations in the Pentagon Papers infuriated a country sick of the war, the body bags of young Americans, the photographs of Vietnamese civilians fleeing U.S. air attacks and the endless protests and counterprotests that were dividing the country as nothing had since the Civil War.

The lies revealed in the papers were of a generational scale, and, for much of the American public, this grand deception seeded a suspicion of government that is even more widespread today.

Officially titled “Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force,” the papers filled 47 volumes, covering the administrations of President Franklin D. Roosevelt to President Lyndon B. Johnson. Their 7,000 pages chronicled, in cold, bureaucratic language, how the United States got itself mired in a long, costly war in a small Southeast Asian country of questionable strategic importance.

They are an essential record of the first war the United States lost. For modern historians, they foreshadow the mind-set and miscalculations that led the United States to fight the “forever wars” of Iraq and Afghanistan.

The original sin was the decision to support the French rulers in Vietnam. President Harry S. Truman subsidized their effort to take back their Indochina colonies. The Vietnamese nationalists were winning their fight for independence under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh, a Communist. Ho had worked with the United States against Japan in World War II, but, in the Cold War, Washington recast him as the stalking horse for Soviet expansionism.

American intelligence officers in the field said that was not the case, that they had found no evidence of a Soviet plot to take over Vietnam, much less Southeast Asia. As one State Department memo put it, “If there is a Moscow-directed conspiracy in Southeast Asia, Indochina is an anomaly.”

But with an eye on China, where the Communist Mao Zedong had won the civil war, President Dwight D. Eisenhower said defeating Vietnam’s Communists was essential “to block further Communist expansion in Asia.” If Vietnam became Communist, then the countries of Southeast Asia would fall like dominoes.

This belief in this domino theory was so strong that the United States broke with its European allies and refused to sign the 1954 Geneva Accords ending the French war. Instead, the United States continued the fight, giving full backing to Ngo Dinh Diem, the autocratic, anti-Communist leader of South Vietnam. Gen. J. Lawton Collins wrote from Vietnam, warning Eisenhower that Diem was an unpopular and incapable leader and should be replaced. If he was not, Gen. Collins wrote, “I recommend re-evaluation of our plans for assisting Southeast Asia.”

In 1957, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, center, visited San Francisco, arriving on U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s private plane. Six and a half years later, the U.S. backed a coup that left Diem dead. Credit…Associated Press

In 1957, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem, center, visited San Francisco, arriving on U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s private plane. Six and a half years later, the U.S. backed a coup that left Diem dead. Credit…Associated PressSecretary of State John Foster Dulles disagreed, writing in a cable included in the Pentagon Papers, “We have no other choice but continue our aid to Vietnam and support of Diem.”

Nine years and billions of American dollars later, Diem was still in power, and it fell to President Kennedy to solve the long-predicted problem.

After facing down the Soviet Union in the Berlin crisis, Kennedy wanted to avoid any sign of Cold War fatigue and easily accepted McNamara’s counsel to deepen the U.S. commitment to Saigon. The secretary of defense wrote in one report, “The loss of South Vietnam would make pointless any further discussion about the importance of Southeast Asia to the Free World.”

The president increased U.S. military advisers tenfold and introduced helicopter missions. In return for the support, Kennedy wanted Diem to make democratic reforms. Diem refused.

A popular uprising in South Vietnam, led by Buddhist clerics, followed. Fearful of losing power as well, South Vietnamese generals secretly received American approval to overthrow Diem. Despite official denials, U.S. officials were deeply involved.

“Beginning in August of 1963, we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts …,” the Pentagon Papers revealed. “We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans.”

The coup ended with Diem’s killing and a deepening of American involvement in the war. As the authors of the papers concluded, “Our complicity in his overthrow heightened our responsibilities and our commitment.”

Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated, and the Vietnam issue fell to President Johnson.

He had officials secretly draft a resolution for Congress to grant him the authority to fight in Vietnam without officially declaring war.

Missing was a pretext, a small-bore “Pearl Harbor” moment. That came on Aug. 4, 1964, when the White House announced that the North Vietnamese had attacked the U.S.S. Maddox in international waters in the Gulf of Tonkin. This “attack,” though, was anything but unprovoked aggression. Gen. William C. Westmoreland, the head of U.S. forces in Vietnam, had commanded the South Vietnamese military while they staged clandestine raids on North Vietnamese islands. North Vietnamese PT boats fought back and had “mistaken Maddox for a South Vietnamese escort vessel,” according to a report. (Later investigations showed the attack never happened.)

Testifying before the Senate, McNamara lied, denying any American involvement in the Tonkin Gulf attacks: “Our Navy played absolutely no part in, was not associated with, was not aware of any South Vietnamese actions, if there were any.”

McNamara, center background, testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 20, 1966. “We should be proud of what we are doing out there for the people of South Vietnam,” he told the committee. Credit…Henry Griffin/Associated Press

McNamara, center background, testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 20, 1966. “We should be proud of what we are doing out there for the people of South Vietnam,” he told the committee. Credit…Henry Griffin/Associated PressThree days after the announcement of the “incident,” the administration persuaded Congress to pass the Tonkin Gulf Resolution to approve and support “the determination of the president, as commander in chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression” — an expansion of the presidential power to wage war that is still used regularly. Johnson won the 1964 election in a landslide.

Seven months later, he sent combat troops to Vietnam without declaring war, a decision clad in lies. The initial deployment of 20,000 troops was described as “military support forces” under a “change of mission” to “permit their more active use” in Vietnam. Nothing new.

As the Pentagon Papers later showed, the Defense Department also revised its war aims: “70 percent to avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat … 20 percent to keep South Vietnam (and then adjacent) territory from Chinese hands, 10 percent to permit the people of South Vietnam to enjoy a better, freer way of life.”

Westmoreland considered the initial troop deployment a stopgap measure and requested 100,000 more. McNamara agreed. On July 20, 1965, he wrote in a memo that even though “the U.S. killed-in-action might be in the vicinity of 500 a month by the end of the year,” the general’s overall strategy was “likely to bring about a success in Vietnam.”

As the Pentagon Papers later put it, “Never again while he was secretary of defense would McNamara make so optimistic a statement about Vietnam — except in public.”

Fully disillusioned at last, McNamara argued in a 1967 memo to the president that more of the same — more troops, more bombing — would not win the war. In an about-face, he suggested that the United States declare victory and slowly withdraw.

And in a rare acknowledgment of the suffering of the Vietnamese people, he wrote, “The picture of the world’s greatest superpower killing or seriously injuring 1,000 noncombatants a week, while trying to pound a tiny backward nation into submission on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed, is not a pretty one.”

Johnson was furious and soon approved increasing the U.S. troop commitment to nearly 550,000. By year’s end, he had forced McNamara to resign, but the defense secretary had already commissioned the Pentagon Papers.

In 1968, Johnson announced that he would not run for re-election; Vietnam had become his Waterloo. Nixon won the White House on the promise to bring peace to Vietnam. Instead, he expanded the war by invading Cambodia, which convinced Daniel Ellsberg that he had to leak the secret history.

Daniel Ellsberg and Patricia Marx, his wife, center, at the Watergate hearings. Nine months before the Watergate break-in, the so-called plumbers had ransacked the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, in search of incriminating files. Credit…Mike Lien/The New York Times

Daniel Ellsberg and Patricia Marx, his wife, center, at the Watergate hearings. Nine months before the Watergate break-in, the so-called plumbers had ransacked the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, in search of incriminating files. Credit…Mike Lien/The New York TimesAfter The New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers on Sunday, June 13, 1971, the nation was stunned. The response ranged from horror to anger to disbelief. There was furor over the betrayal of national secrets. Opponents of the war felt vindicated. Veterans, especially those who had served multiple tours in Vietnam, were pained to discover that Americans officials knew the war had been a failed proposition nearly from the beginning.

Convinced that Ellsberg posed a threat to Nixon’s re-election campaign, the White House approved an illegal break-in at the Beverly Hills, Calif., office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, hoping to find embarrassing confessions on file. The burglars — known as the Plumbers — found nothing, and got away undetected. The following June, when another such crew broke into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate complex in Washington, they were caught.

The North Vietnamese mounted a final offensive, captured Saigon and won the war in April 1975. Three years later, Vietnam invaded Cambodia — another Communist country — and overthrew the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime. That was the sole country Communist Vietnam ever invaded, forever undercutting the domino theory — the war’s foundational lie.

Elizabeth Becker is a former New York Times correspondent who began her career covering the Cambodia campaign of the Vietnam War. She is the author, most recently, of “You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War.”

This article originally appeared in the New York Times on June 9, 2021. Here’s the direct link: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/09/us/pentagon-papers-vietnam-war.html

*****

So, what percent of everything you hear from government officials today do you believe to be TRUE? Leave your comments below.

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 24, 2024

Scrounging during the Vietnam War

American Ranger Advisors and ARVN Ranger units were snubbed by their “old school” parent units and often treated like “Bastard Children” when it came to dishing out supplies and other necessities. As a result, the BDQ Advisor usually became the unit scrounger to finagle needed supplies for their camps and their inhabitants. Keith Nightingale was one of them—read how he managed in this role.

By Keith Nightingale

Key to any BDQ (Referred to as Biêt–Dông–Quân or BDQ, a significant number of Ranger-qualified officers and NCOs served as advisors to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam Ranger units) advisor’s success and comfort was the ability to scrounge. The Rangers were usually located in semi-isolated sites with minimal amenities such as housing, food and protection from the elements. Add to that minimal supporting weapons, adequate ammo, barrier material and overhead cover. In many cases, the ARVN Ranger wives and kids co-located with their husbands, making the conditions even more barren. Hence, each BDQ team usually developed an informal scrounge capability for whatever was direly needed that the ARVN Army would not/could not provide. My experience is just a microcosm of all Ranger advisors.

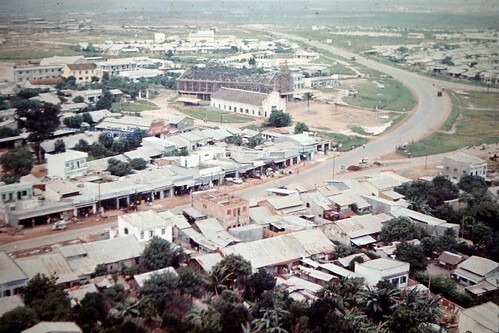

Located on a bare hill in Xuan Loc, with a full complement of Rangers, wives, kids and dogs and minimal close-in defense capabilities, our “accommodation” was a GP Medium tent with sufficient holes to make it an observatory. The floors were mud, and the cots were from WWII. We were plush compared to the Vietnamese. Candles were the illumination, water a scarce commodity and fortifications of the barest nature. Rain was a continuous challenge.

Lt Nightingale, Deputy Advisor, was anointed as the Czar of Scrounge. After overcoming culture shock in my first-week in-country, I was tasked with “finding stuff.” This meant a Japanese jeep ride into Bien Hoa and Long Binh to develop an acquisition system.

I kept a journal as I visited each US org, did some minor BS’ing to determine what they had in excess and what they needed/wanted. In many cases, each had what others did not and I could make a trailer resolve the issue, in turn, getting a cut. By evening, a good haul would be collected at an Army buddy’s place in Long Binh.

I would call the battalion via landline and request X Vietnamese 2 ½ ton trucks to haul the usual tarps, wood, tin, med equipment, ammo, and weapons parts. The trucks would bring Ranger wife manufactured VC flags and Montagnard bows which were prime trading material.

Often, this is all that was needed to close a trade. At Ranger Hill, a thriving industry grew.

Then, time provided ideas and experiences. I visited the Philco-Ford offices at their storage yard at Saigon Port. After working my way through several factotums- speaking Vietnamese was a shock and a plus-I got to the man with the power of the pen. He was a short guy with a lot of energy and a cowboy hat. Clearly a cut to the chase guy. I explained the dire circumstances of the unit, the lack of interest by anyone in the chain and my abject desperation. He pulled out two ice-cold “33” beers from his office fridge and pulled out a sheaf of papers. He wrote authorizations for pallets of 2x4s, galvanized tin, nails, a 10KW generator with a mile of light sets, sacks of cement and several thousand sandbags. He looked me in the eye and told me to have 12 trucks at the yard at 0800 in the morning with this paper. He also suggested I visit the PDO yard next to his. The Senior Advisor was certain I was deep into the Black market which I assured him was not the case and the battalion commander was incredulous but said the trucks would be there-which they were.

The PDO yard, however, was Christmas all the time. The yard was a vast storehouse of everything the US Army didn’t want, couldn’t use or was mis-sent for re-shipping. I became very proficient with a large forklift, which separated GP Mediums, Kitchen Fly, and GP Small tents- vastly superior to the present Ranger hootches. This would be my perennial Go-to place after operations throughout the year. A long row of Conex containers held weapons-allegedly malfunctioning or broke. I found neither to be the case much………..50 cals with timing gauges, M60s, M79s, M16s, magazines, tripods, and mortars, both 81 and 4.2. A double-wide held a radio repair facility run by a Vietnamese.

We had a cup of café sua where I explained our situation, gave him 20 MPC and he “gifted” me six functioning PRC 25s-a major upgrade from the PRC 10s. I would personally accompany this sensitive loot back to Xuan Loc to ensure no diversions. Soon, Ranger Hill had lights, a decent tent city, barbed wire and sandbagged positions, a quality ops bunker, vastly more firepower and a team house duplex for the advisors and the battalion commander.

Tet struck and we rarely were back. Regardless, now as Senior Advisor, I had my deputy undertake the same tasks to better our lives throughout III Corps as we wandered with the whims of the General Staff. We usually had lights and more firepower than most.

#####

Keith has contributed almost a dozen posts to this website. To read more of his work, go to the top right of this post and click on the magnifying glass, type in “Keith Nightingale”, and hit enter for a drop-down menu.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 19, 2024

The Moving Wall Schedule for 2025

We are delighted to share The Wall That Heals national tour schedule for 2025 with you. Our three-quarter scale replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial along with a mobile Education Center begins its 30th tour season on March 6, 2025, in Sebring, Florida. During the 2025 tour, we will bring The Wall to 31 communities across the country. At every stop, we’ll pay tribute to the 58,281 men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice in Vietnam and honor the more than three million Americans who served in the U.S. Armed Forces in the Vietnam War. In addition to educational exhibits, our mobile Education Center will display the photos of service members whose names are on The Wall that list their home of record within the area of a visit. The Center will also display photos of Vietnam veterans from the local area honored through VVMF’s In Memory program, which honors veterans who returned home from Vietnam and later died.

The Wall That Heals 2025 Tour dates include:

Sebring, Fla. (March 6 – 9)

Kissimmee, Fla. (March 13 – 16)

Baton Rouge, La. (March 20 – 23)

Corpus Christi, Texas (March 27 – 30)

Laredo, Texas (April 3 – 6)

D’Iberville, Miss. (April 10 – 13)

Whiteville, N.C. (April 24 – 27)

Roxboro, N.C. (May 1 – 4)

Johnson City, Tenn. (May 8 – 11)

Liberty, S.C. (May 15 – 18)

Shaler Township, Pa. (May 23 – 26)

Warren, Ohio (May 29 – June 1)

Troy, N.Y. (June 5 – 8)

Claremont, N.H. (June 26 – 29)

Farmington, Maine (July 3 – 6)

Montgomery Township, Pa. (July 10 – 13)

Antioch, Ill. (July 17 – 20)

St. Louis County, Mo. (July 24 – 27)

Buckner, Mo. (July 31 – August 3)

Nevada, Iowa (August 7 – 10)

Emporia, Kan (August 14 – 17)

Spokane, Wash. (August 28 – 31)

Ellensburg, Wash. (September 4 – 7)

Port Townsend, Wash. (September 11 – 14)

Independence, Ore. (September 18 – 21)

Orange, Calif. (October 2 – 5)

Clovis, Calif. (October 9 – 12)

American Canyon, Calif. (October 16 – 19)

Wylie, Texas (October 30 – November 2)

Athens, Ala. (November 6 – 9)

Crystal Springs, Miss. (November 13 – 16)

*For the most up-to-date schedule, please visit https://www.vvmf.org/The-Wall-That-Heals/

We hope to see you out on the road in 2025!

Sincerely,

The VVMF Team

November 16, 2024

How America Fought Chinese Troops in Vietnam

During the Vietnam War, did you know that U.S. troops fought against Chinese soldiers? Check out this short article to learn more.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident (August 1964) and the arrival of US combat troops (1965) triggered an escalation in Chinese support. This came mainly in the form of equipment and construction. In 1965, Beijing sent several thousand engineering troops to North Vietnam to assist in building and repairing roads, railways, airstrips, and critical defense infrastructure. Between 1965 and 1971, more than 320,000 Chinese troops were deployed in North Vietnam. The peak year was 1967 when there were around 170,000 Chinese in the communist state. Their work on military installations meant that Chinese troops were susceptible to American bombing runs. An estimated 1,000 Chinese were killed in the North in the late 1960s. Beijing also supplied Hanoi with large amounts of military equipment, including trucks, tanks, and artillery.

This is a largely untold story of how Chinese intervention in the Vietnam War played out. Why did US troops battle directly against Chinese special forces and advisors in the war? How did it happen? Exactly how much artillery, money, and supplies did China send? Many people know about the Soviet Union’s involvement in the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 1970s, but not many people know about China’s role. Please watch this eighteen-minute video to learn more.

Source I read directly from throughout this video:

https://www.jstor.org/journal/chinaqu…

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/China_i….

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archiv…

I’m your average infantryman Chris Cappy from Task & Purpose. Thank you for watching!

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 9, 2024

CHEESE SANDWICH AND WARM COKE-HOW THE WAR PLAYED

Keith Nightingale shares a story with readers showing how an infantry company commander tried to maintain morale while his unit was unnecessarily pushed by battalion to continue daily contact with an enemy that was inflicting casualties. Good happens to those who try to do good to others.

By Keith Nightingale

Jack and the company had been on an extended sweep for more than ten days on a four-day log cycle. The operational area had been a blend of A Shau dense jungle and scrub Kunai grass. They had almost daily contact with six KIA and 15 WIA. The area was deemed to be “rich” with NVA engagement opportunities-a situation Higher seemed to love, the company less so.

It was the height of the dry season and the captain had tried to keep the unit near streams through that was not always possible. Battalion always was pushing for ambush sites along the mountain’s edges where it abutted the long sloping ground into the occupied plain. All the ambush positions had been distinctly lacking in water.

Troops were laden with five-quart and three canteens in addition to basic loads considerably more than basic. No one wanted to run out of ammo in light of the recent history. Additional Claymores were also humped as they were invaluable for mechanical ambushes-not requiring human overwatch-a major plus.

Battalion had opted to cancel a scheduled log day as the company had several running engagements and it didn’t want to break meaningful contact. The S4 had arranged for a C ration airdrop through the canopy as well as an ammo package dump. This was done by a canopy-level hover of several Hueys kicking out the loads in the deep canopy. The drop site was enroute to a further objective so it was believed to be a much better idea than having a formal log day PZ on open ground.

Several of the ration boxes were caught in the high canopy, limiting the availability of an already less than full supply. The captain and Jack had collected all the dropped supplies. Batteries were in quantity as well as the following days secure codes and opskeds. The limited recovered rations meant that every meal had to be shared between two men. No large sundry packs meant no books, M&M’s, snuff or cigarettes-all of which were major morale items.

Some red nylon mail sacks were dropped but only half of those for the unit. The NCO’s distributed these after Jack had organized them all by platoon. He received two letters. One was from his mother where she described his dad’s recent tractor accident putting him in a leg cast necessitating her hiring help to compensate on the farm. The other was from a funeral home advertising pre-need plans featuring cremation. Jack thought it altogether appropriate.

The captain directed a lottery amongst the command group for the chow. All boxes would be placed label down in a square. Members would be dealt a playing card face up. The highest value card chose a box and was allowed to extract one item from the box, returning it to its place. Once all hands had a pick, all cards were redealt and the system repeated. No person was allowed to take more than one can at a time. The small sundry pack in each box was extracted and placed in a pile.

In this manner, all the cans were selected. The captain spread the sundry packs evenly so everyone got at least one. The residual would be kept by the FO as a future reward for good service as determined by the captain. Within an hour, the company was ready to move out.

Jack had all ration boxes stacked in the center of the perimeter. He placed a thermite grenade on top with a 15 minute fuse on a blasting cap underneath. Det cord was wrapped around the can. The grenade pin was extracted and the top contained by the first inch of an empty fruit can. The blasting cap would release the fruit can causing a wide dispersion of thermite, incinerating anything useful. Jack would light this just as the unit moved out.

Shortly, the order to move out was given and men began to ruck up and face south. The ground was irregularly sloped under the canopy which greatly increased the difficulty in walking, one leg always higher than the other. Now fully loaded with water, rations and ammunition, the line of green moving men was lost in the individual thoughts used to neutralize the environment in whatever personal way was comfortable in a very uncomfortable situation.

Hunger began to have a mental effect on the unit as time passed. Men could be having heated whispered arguments as they fought over sharing a pecan roll or Ham and Eggs, Chopped, water added. Even Ham and Limas were consumed without complaint. The lack of smokeless tobacco became a significant morale issue, especially in the nightly NDP (Night Defensive Position).

The captain, well aware of this as he walked the perimeter developed a plan for the following day. In time, around noon, they came to a relatively large creek that converged with another. He ordered a perimeter for a one-hour halt. He directed that a smoke break be held en masse. Out came the out of business tobacco firms four cigarette packs from the sundry packets and whatever waterproof cigarettes were still being hoarded. This ensued a lot of almost laughter and a visible rise in morale. Very quickly, almost everyone was smoking, talking in low tones and smiling. Even the non-smokers took an opportunity to assuage the hunger and enjoy the novel moment. In the bush, a little can mean a lot.

Eventually, by Day Ten, battalion recognized it could squeeze no more blood out of the stone and directed a movement to a log LZ. Ironically, this location consumed almost an entire day over rough terrain to achieve. When they did arrive, it did not improve morale.

It was a large densely packed Kunai grass meadow. There was minimal shade which could be barely achieved under the taller grass stands or artificially created under a poncho liner. The air was dead still with density currents clearly rising across the open areas. An LZ had to be cut in the center which was extremely painful work.

The dense stalks had to be macheted to ground level. This meant the cutters had to expose their arms to the razor-sharp grass edges and do so in full sun. The NCO’s ensured that every man work for 15 minutes and then be relieved. It was much like the slaves in the Indies cutting cane but on a short rotation. At the end of a session, the cutter staggered back to his patch of semi-shade and collapsed on the ground. Very quickly, water was almost non-existent and what they had, was decidedly warm.

Overhead, the command chopper rotated awaiting a cleared area. Several times, Long Distance received guidance to adjust the perimeter as well as complaints about the “fuckin tent city” below. Within an hour, the LZ was cleared and the battalion commander landed, hands on hips surveilling the unit. The Huey had kicked up a large cloud of straw, grass and dust which enveloped everyone, adding to the caked dirt already packed between sweat streams. The updraft had blown away a number of the hasty poncho shelters which tore loose and floated all over the ground.

Shortly, four birds landed with the log resupply for the company as well as an advertised A ration meal from the base camp. The troops lined up with the anticipation of hungry wolves with the command group eating last as the battalion commander and captain held a meeting.

Finally, at the end of the line, Jack approached the line of marmites, eager for his share. The pork steaks with mashed potatoes were gone as well as the ice cream. The First Sergeant gave Jack a cardboard box instead which he took back to the shade of a Kunai clump. He opened the box. It was a sandwich with two slices of cheddar cheese and no mayonnaise or dressing. There was also a pony size can of warm Coke. A Louisiana chain gang lunch.

Jack hastily consumed it and threw down the box and can in disgust. He made a mental note that this war was really fucked up.

*****

Keith Nightingale has contributed several articles to this website. To read more of his work, click on the magnifying glass at the top right of the page, type “Keith Nightingale,” and enter to see a drop-down menu. To return to this page, use the “back arrow key” at the top left of the page.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 2, 2024

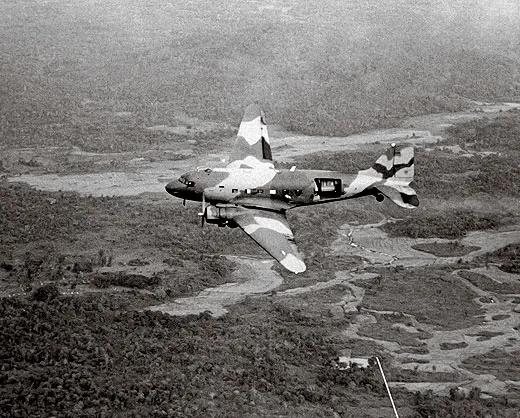

Douglas A-1 Skyraider: Spads and Sandys in Vietnam

An anomaly in the Space Age, the A-1 Skyraider was a prop-powered attack aircraft developed during World War II for naval operations. It’s first flight was in 1945, but it did not see combat until the Korean War. While jets ruled the skies over Vietnam, the A-1 had a unique impact in both attack roles and search and rescue. We take a look at this amazing aircraft that could get low and slow like no others of the time.

All pilots are terrified of fire.

It takes discipline not to think about it unduly. You’re tearing through the sky in a flimsy metal tube filled with an unsettling volume of profoundly flammable aviation gasoline or jet fuel. If something goes wrong, there’s just no place to go.

The A-1 Skyraider was developed in World War II and saw combat service in both Korea and Vietnam. Image: Senior Airman Kathryn R.C. Reaves/U.S.A.F.

The A-1 Skyraider was developed in World War II and saw combat service in both Korea and Vietnam. Image: Senior Airman Kathryn R.C. Reaves/U.S.A.F.Burning to death in flight is a phobia common to all aviators. On the 1st of September, 1968, Lt. Col. William Atkinson Jones III came face-to-face with that very primal fear. The unnatural way he faced that fear earned him the Medal of Honor.

Behind Enemy LinesAn F-4 Phantom pilot had been brought down 20 miles northwest of Dong Hoi in North Vietnam. Now helpless and alone amidst a rugged karst formation and surrounded by enraged North Vietnamese troops equipped with heavy anti-aircraft systems, this beleaguered U.S. Air Force pilot prepared to die. Then he heard it.

A Douglas A-1E Skyraider carrying a BLU-72/B FAE (Fuel/Air Explosive) bomb under the right wing during take-off on September 29, 1968. Image: U.S.A.F.

A Douglas A-1E Skyraider carrying a BLU-72/B FAE (Fuel/Air Explosive) bomb under the right wing during take-off on September 29, 1968. Image: U.S.A.F.1968 was the middle of the Space Age. The U.S. military operated the most advanced jet combat aircraft in the world. However, this was something different. What this helpless pilot heard was the deep, throaty rumble of a Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone radial engine. That sound would have been right at home in the skies over Europe during World War II.

To that downed American pilot, the growl of that massive piston-driven engine was the sound of angels singing.

That particular big Wright radial was perched on the nose of a Douglas A-1 Skyraider piloted by Lt. Col. Bill Jones. Everyone called the Skyraider the Spad after the famed French fighter of WWI fame. When assigned to combat search and rescue duties, the Skyraider was called Sandy. Sandys would fly cover while a Jolly Green Giant helicopter recovered the downed pilot.

An A-1 Skyraider takes off from Da Nang Air Base on a combat mission, circa 1964. Image: U.S.M.C./CC BY 2.0

An A-1 Skyraider takes off from Da Nang Air Base on a combat mission, circa 1964. Image: U.S.M.C./CC BY 2.0Jones’ Sandy was part of a rescue package deployed to try to snatch this downed American pilot out of the jaws of death. While they had radio contact with the isolated aviator, they did not yet have his exact location. Everything else turned on that piece of information.

Jones dove his heavy strike aircraft down on the deck and began looking for trouble. Suddenly the North Vietnamese defenders opened up with a ZSU-23-2 twin-barrel 23mm antiaircraft gun. AAA (anti-aircraft artillery) was the alpha killer of airplanes on low-level strike missions. Several rounds struck Jones’ Skyraider, and the cockpit filled with smoke.

Napalm and bombing runs by Skyraiders on NVA digging trenches around the Khe Sanh Combat Base in February/March 1968. Image: U.S.M.C./CC BY 2.0

Napalm and bombing runs by Skyraiders on NVA digging trenches around the Khe Sanh Combat Base in February/March 1968. Image: U.S.M.C./CC BY 2.0This is where most normal pilots, even the steely-eyed sort, would have passed the reins off to a wingman and returned to base. However, Lt. Col. Jones knew what was riding on this. Minutes counted. If the NVA got to this downed aviator before the Jolly Green Giant rescue helicopter did, the Phantom driver would spend the rest of the war in a prison camp…or worse.

With his plane damaged and smoke filling the cockpit, Lt. Col. Jones wheeled the big plane around and made another pass.

This time he zeroed the pilot as well as the nearby ZSU that had shot up his airplane. Arming his weapons, Jones made two runs against the AAA position, slathering it with 20mm cannon and rocket fire.

This Republic of Vietnam Air Force A-1 Skyraider delivered napalm in this strike against North Vietnamese positions. Image: U.S.A.F.

This Republic of Vietnam Air Force A-1 Skyraider delivered napalm in this strike against North Vietnamese positions. Image: U.S.A.F.On his second pass, nearby NVA guns pounded his big airplane mercilessly. One round detonated the Yankee Extraction System rocket located behind his headrest. This rocket-assisted ejection device subsequently burned inside the cockpit, filling the space with searing flames. Jones blew the canopy off of his airplane, which made the fire briefly worse. However, his ejection system was spent. Now there was no way for the badly burned pilot to egress his aircraft.

Jones had not been able to notify the rest of his team of the downed pilot’s location. The battle damage had destroyed his radios. Now desperately burned, Jones wracked his stricken plane over and firewalled the throttle. He successfully landed his big airplane and was rushed to surgery.

Before he would allow the surgical team to put him under, Lt. Col. Jones insisted on relating a detailed description of the downed pilot’s location from the operating table. This information was radioed back to the rescue package that was working the area. The downed pilot was successfully recovered later that day.

Anatomy of the SkyraiderThe Douglas A-1 Skyraider first flew on March 18, 1945, but it was not operational by the end of WWII. The Skyraider was designed to be a carrier-based, single-seat, long-range, high-endurance torpedo/dive bomber. Prior to entering active service with the U.S. Navy, Japan formally surrendered and ended the Second World War. While the Skyraider never faced off against Japanese aircraft carriers, these attributes turned out to be ideal for close air support in the skies above Vietnam.

A fire department water truck was used to clean the 6th Special Operations Squadron Skyraider aircraft at Pleiku Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, 1967. Image: U.S.A.F.

A fire department water truck was used to clean the 6th Special Operations Squadron Skyraider aircraft at Pleiku Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, 1967. Image: U.S.A.F.In 1946, the Skyraider’s designation was changed to AD-1. During the course of development, engineers stripped the airframe of every piece of unnecessary equipment in a successful effort to give it a long loiter time. In the process, they faired over the bomb bay but mounted a total of 14 external hard points on the wings along with one on the centerline. This gave the Douglas aircraft the capability of carrying a breathtaking array of ordnance.

In addition to being powerful, the Wright engine was rugged. The big 18-cylinder air-cooled radial engine proved exceptionally resistant to battle damage.

U.S. Navy Douglas Skyraider attack plane on patrol from USS Boxer (CV-21) in September 1951. The ship was en route to the Korean combat area. Image: NARA

U.S. Navy Douglas Skyraider attack plane on patrol from USS Boxer (CV-21) in September 1951. The ship was en route to the Korean combat area. Image: NARADouglas eventually produced versions of the Skyraider that carried two, three or four aircrew members. Variants were capable of night attack operations and electronic warfare missions.

The entire production run of 3,180 aircraft progressed through seven major variants. The U.S. Navy and U.S. Marines used the Skyraider during the Korean War. As the United States entered the Vietnam War, the Navy employed the Skyraider as a medium attack aircraft while the Douglas A-3 Skywarrior held the role of carrier-based strategic bomber.

A Douglas AD-4 Skyraider during a flight demonstration at the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Image: Max Lonzanida/U.S. Navy

A Douglas AD-4 Skyraider during a flight demonstration at the Military Aviation Museum in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Image: Max Lonzanida/U.S. NavyAs the new jet-powered A-6 Intruder was delivered, the US Navy phased out the rugged old Skyraider. Many of the Navy’s Skyraiders were transferred to the Republic of Vietnam. The South Vietnamese Air Force used the Skyraiders extensively in ground attack roles.

The United States Air Force also adopted the plane during the Vietnam War. The U.S.A.F. frequently used the A-1 in the Sandy role to recover lost pilots.

The last Skyraiders were phased out of the active U.S. inventory in 1973. However, their legacy lives on.

AD-6/A-1H Skyraider Technical SpecificationsLength38′ 10″Wingspan50′PowerplantWright R-3350-26WA Duplex-Cyclone 18-cylinder radial engineMaximum Speed280 knots/322 mphRange1,316 milesArmament4xAN/M3 20mm cannon with 200 rounds per gunOrdnance15 external hardpoints with a total capacity of 8,000 poundsA-1 Skyraiders at WarThe pilots who flew the Skyraider adored the plane for its rugged construction and forgiving flight characteristics. The grunts and downed aviators who were supported by it veritably worshipped the machine. In a world of fast-moving attack jets, it was the lumbering Skyraider that most reliably brought the pain.

During the Korean War, a Skyraider waits to be launched from the port side catapult on the U.S.S. Leyte (CV-42). Also shown are an F4U Corsair and an F9F Panther. Image: NARA

During the Korean War, a Skyraider waits to be launched from the port side catapult on the U.S.S. Leyte (CV-42). Also shown are an F4U Corsair and an F9F Panther. Image: NARAThroughout the Korean War, Marine and Navy Skyraiders were workhorses in ground attack roles. While newer jet aircraft were the darlings of many, it was the Skyraider that was able to fly long missions, loiter extended periods over the battlefield and deliver large quantities of ordnance. While the aircraft were rugged, the pilots paid a heavy price to support their countrymen and allies on the ground. More than 100 Skyraiders were lost in combat.

On July 26, 1954, a pair of Skyraiders splashed two Chinese Lavochkin La-11 “Fang” fighters during an international incident near Hainan Island, China. Chicom fighters launched an unprovoked attack against a DC-4 Skymaster civilian airliner operated by Cathay Pacific Airways. During a search for survivors, Skyraiders shot down the La-11 fighters.

Young naval aviator John B. McKamey standing on the wing of a Douglas A-1 Skyraider in 1951. In 1965, McKamey was shot down in Vietnam and spent nearly eight years as a prisoner of war. Image: U.S. Navy

Young naval aviator John B. McKamey standing on the wing of a Douglas A-1 Skyraider in 1951. In 1965, McKamey was shot down in Vietnam and spent nearly eight years as a prisoner of war. Image: U.S. NavyWhile the ground attack capabilities of the Skyraider were frequently demonstrated in Vietnam, they also picked up air-to-air kills. A pair of North Vietnamese MiG-17 fighters were downed on June 20, 1965, by Lt. Clint Johnson and Lt. Charles Hartman. These were the first gun kills of the war.

On August 5, 1964, Lt. Richard Sather was shot down while flying as part of Operation Pierce Arrow. He was the first Navy pilot lost during the war. In October 1965, to commemorate the 6 millionth pound of ordnance dropped over Vietnam, Cmdr. Clarence Stoddard of VA-25 dropped a Navy surplus toilet along with the rest of his standard combat load.

Legacy of the A-1 SkyraiderEntering the Vietnam War, the U.S. Navy already had the A-6 in development. The Air Force, however, did not have a clear upgrade path.

An A-1 Skyraider is flanked by a pair of A-10 Thunderbolt IIs in an aerial demonstration at a 2017 airshow in Boise, Idaho. Image: Airman 1st Class Mercedee Schwartz/U.S. Air National Guard

An A-1 Skyraider is flanked by a pair of A-10 Thunderbolt IIs in an aerial demonstration at a 2017 airshow in Boise, Idaho. Image: Airman 1st Class Mercedee Schwartz/U.S. Air National GuardWhile the Skyraider performed well during the conflict, losses were heavy — many due to ground fire. Taking the hard-won lessons to heart, the Air Force began the process of developing dedicated close air support aircraft. The initial proposal indicated a need for increased survivability and additional ordnance delivery. By 1970, the Air Force requirements were updated to include all weather and anti-tank capabilities. The result was the Fairchild A-10 Thunderbolt II.

During Vietnam, more than 250 of the A-1 planes — and too many pilots — were lost. However, the number of downed pilots, soldiers and Marines saved by the Skyraider is so great as to be uncountable.

An A-1 Skyraider sits on the flight line at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. The Skyraider provided close-air support in Korea and Vietnam. Image: Senior Airman Nicholas Ross/U.S.A.F.

An A-1 Skyraider sits on the flight line at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. The Skyraider provided close-air support in Korea and Vietnam. Image: Senior Airman Nicholas Ross/U.S.A.F.Lt. Col. Jones was promoted to Colonel and awarded the Medal of Honor. Sadly, he died in a Virginia aircraft accident before the MoH presentation. His widow accepted the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon at the White House on August 6, 1970.

Lt. Col. William Jones’ complete disregard for his personal safety at the controls of his A-1 exemplifies the American warrior ethos — and the capabilities of the humble Skyraider.

This article is featured in volume 13: Weapons of the Vietnam War Digital Magazine

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

October 26, 2024

Steinbeck’s Dispatches From Vietnam

Did you know that famed author John Steinbeck spent over a year in Vietnam during the war? In 1966, the author of The Grapes of Wrath met a new working class: Hueys, Hercs, and Spooky. His wit is evident in some of the posts. Here are a few excerpts from his book:

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson asked John Steinbeck to visit South Vietnam and report to him personally on U.S. operations. (Steinbeck’s third wife, Elaine, and Lady Bird Johnson had been friends at college, and the Steinbecks were frequent visitors to the White House.) Steinbeck was reluctant to go to Vietnam on behalf of the president, but when the Long Island daily Newsday suggested that he travel throughout Southeast Asia as a roving reporter, he accepted. By that time, his two sons were serving in the Army. Between December 1966 and May 1967, Steinbeck wrote 86 stories for the newspaper. Those columns—collected in a book by the University of Virginia Press titled Steinbeck in Vietnam—were the last work to be published during Steinbeck’s lifetime.

December 31, 1966, Saigon: Remember how the lordly jet cuts its engines at 35,000 feet and floats gently toward the earth like Mark Twain’s polyhedron on lonely pinion? Well, that’s not the way you land in Saigon. Your friendly pilot pulls the plug and scuttles down like Walter Kerr leaving the theater or water making an exit from a bathtub. I guess he figures that the quicker he gets in, the less chance he has of taking a hit from a [Viet Cong] crossbow.

[Ca. January 1967/Vietnam]

Did you know that the airport at Saigon is the busiest in the world, that it has more traffic than O’Hare field in Chicago and much more than Kennedy in New York—Well it’s true. We stood around—maybe ten thousand of us all looking like overdone biscuits until our plane was called. It was not a pretty ship this USAF C-130. Its rear end opens and it looks like an anopheles mosquito but into this huge anal orifice can be loaded anything smaller than a church and even that would go in if it had a folding steeple. For passengers, the C-130 lacks a hominess. Four rows of bucket seats extending lengthwise into infinity. You lean back against cargo slings and tangle your feet in a maze of cordage and cables.

Before we took off a towering sergeant (I guess) whipped us with a loud speaker. First he told us the dismal things that could happen to our new home by ground fire, lightning or just bad luck. He said that if any of these things did happen he would tell us later what to do about it. Finally he came to the subject nearest his heart. He said there was dreadful weather ahead. He asked each of us to reach down the paper bag above and put it in our laps and if we felt queasy for God’s sake not to miss the bag because he had to clean it up and the hundred plus of us could make him unhappy. After a few more intimations of disaster he signed off on the loud speaker and the monster ship took off in a series of leaps like a Calaveras County frog.

Once airborne, I got invited to the cockpit where I had a fine view of the country and merciful cup of black scalding coffee. They gave me earphones so I could hear directions for avoiding ground fire and the even more dangerous hazard of our own artillery. The flight was as smooth as an unruffled pond. And when we landed at Pleiku I asked the God-like sergeant why he had talked about rough weather.

“Well, it’s the Viets,” he said. “They have delicate stomachs and some of them are first flights. If I tell them to expect the worst and it isn’t, they’re so relieved that they don’t get sick. And you know I do have to clean up and sometimes it’s just awful.”Report this ad

January 7, 1967/Pleiku

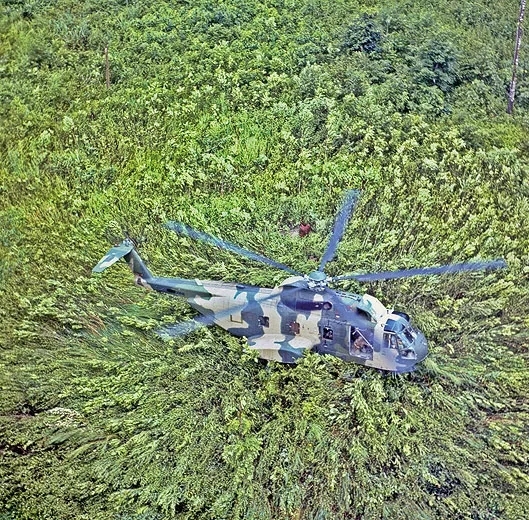

In my opinion the chopper is the greatest invention since the wheel. In eight days I have covered areas and put down in places it would have taken many months to visit on foot and that would be the only way to travel since there are few roads, and many of these are impassable, and what railroads there once were are cut and mangled by the fighting. I think I have traveled in every kind of chopper we have save one, or rather two. There is a single-place bubble I’ve missed because I can’t fly the thing, and I haven’t been on the giant Sky Crane, which looks like a huge dragonfly or praying mantis and which can take in its arms anything it can grip.

It has transported a complete operating room with surgery continuing during flight. Eventually, when we have enough of them, the Crane will be of major logistical importance.

January 7, 1967/Pleiku

I wish I could tell you about these pilots [10th Cavalry, Huey helicopter]. They make me sick with envy. They ride their vehicles the way a man controls a fine, well-trained quarter horse. They weave along stream beds, rise like swallows to clear trees, they turn and twist and dip like swifts in the evening.

I watch their hands and their feet on the controls, the delicacy of the coordination reminds me of the sure and seemingly slow hands of [Pablo] Casals on the cello…. You will gather that we are now in V.C. country, where every tree may open fire and often does. Maj. Thomas dips into a stream bed cascading down a twisting canyon and you realize that low green cover you saw from high up is towering screaming jungle so dense that noonday light fails to reach the ground. The stream bed twists like a snake and we snake over it, now and then lofting like a tipped fly ball to miss an obstruction or cutting around a tree the way a good cow horse cuts out a single calf from a loose herd.

February 2, 1967/Saigon

Soon after I arrived in South Vietnam, I became aware of the constant presence of slow, low-flying, fixed wing, single engine airplanes that coast and cruise about, circling and quartering. And it wasn’t long before I began to hear about the F.A.C. or Forward Air Controllers.

They are among the bravest and the most trusted and admired men in this shattered country, and to the enemy, the F.A.C. must be about the most feared. I had heard many stories of their duties and their accomplishments and just a day ago I was allowed to fly with one on three separate and different missions, and it was an experience I will not soon forget.

As usual it was an early trip through the roiling traffic of Saigon to the 120th Helicopter Operations at Tan Son Nhut Airport. It gets light late this time of year. At 0710 it was still dawn. Then there was the quick and businesslike chopper trip to My Tho in the Delta district. At breakfast I met my pilot, Maj. William E. Masterson, called “Bat” of course, the Forward Air Controller for the Seventh ARVN Division, a strong good looking officer with a very knowing and humorous eye. He was a B-52 pilot who volunteered for FAC. Indeed, I may be wrong, but I believe all FAC pilots are volunteers.

Our aircraft was an O-1 “Bird Dog,” a single-engine, propeller driven, fixed wing Cessna which moves at 90 to 100 knots and has two seats, one behind the other. It is the same aircraft you see all over America, a slow, dependable job with fixed landing gear, fairly safe if its single engine is properly maintained. Our craft carried four rockets on the wing tips, two M-16 carbines, hand operated and mainly for self-defense in case of a forced landing, and a number of smoke bombs for signaling and marking.Report this ad

We had no parachutes. They would take up too much room and flying as low as the FAC fly—anywhere from 200 to 2,000 feet, you couldn’t get out in time anyway. We did wear the armored vests which are said to take the sting out of small arms fire.

Major Masterson, Bat, said, “They don’t shoot at us much because we can call in an air strike in a few minutes and snipes just don’t want to take the chance. But if we should get hit, I’ll set down easy if I can and then we pile out and hit for cover with the M-16s and wait for rescue.”

I was pretty clumsy getting into the back seat with the thick vest on, and butter-fingered getting the belt and shoulder straps tight. There was no fooling around. The prop soared and brought the oil up to pressure. On the edge of the airstrip a ground man pulled out the pins from the rockets arming them and passed the pins in to me.

The little ship danced down the runway and jumped into the air. I had earphones and a mouthpiece for communication. Our first mission was visual reconnaissance, called naturally VR, and it is unique and fascinating work. Each FAC man has a sizable piece of real estate for which he is responsible. He flies over it every day and sometimes several times a day. He gets to know his spread like the back of his hand and he looks at it so closely that he is aware of any change, even the smallest.Report this ad

I asked what Bat looked for. “Anything,” he said, “absolutely anything.” We were flying at about 500 feet. “See that little house down there? The one right on the river edge.”

“I see it.”

“Well, I know four people live there. If there were six pairs of pants drying on the bushes, I’d know they had visitors, and maybe V.C. visitors. Look at the next place—see those two big crockery pots against the wall? I know those pots. If there were three or four, I’d investigate. Oh! Oh!” he said and swung suddenly in over the paddies away from the river. About ten water buffalo were grazing, standing in the watery field. Our bird dog swung low and the beasts raised their heads at us.

“V.C. transport,” said Bat. “See, how thin they are? They’re working them hard at night.” He made notes on the detailed map on his lap. “We’ll flare tonight and maybe catch them moving.”Report this ad

“Tell me some other things you look for,” I asked.

“Well, there are so many things I don’t know where to start. Too many water plants torn loose. Lines in the mud on the canals or the riverside where boats have landed, trails through the grass that have been used since yesterday. Too many people in one place or not enough people where they should be. We spotted a flock of Charleys because one pair of blue jeans was hanging on a peg in a house where there shouldn’t be blue jeans. Sometimes it’s too much smoke coming from a house at the wrong time. That means they’re cooking for strangers. I can’t begin to tell you all we look for. But sometimes I don’t even know what it is I’m seeing. I just get a nervous feeling, and I have to circle and circle until I work out what it is that’s wrong. You know how your mind warns you and you don’t quite know how.”

“Like extrasensory perception?”

“Yes, I guess something like that,” he said.

We followed the river down to the sea and then moved along the beach south and eastward to where the Marines had recently landed. Their beachhead was manned and we turned inland and swept right and left until we found the advance force moving painfully through the flooded muddy country, all mangrove swamp and nastiness. Masterson talked to the ground. “I can’t see anything up ahead,” he told the weary command. “But don’t take my word. You know how they can hide.”Report this ad

“Don’t we just!” said the ground. We swung back toward the river quartering the country like the bird dog we are named for. On a canal ahead, a line of low houses deep in the trees was slowly burning, almost burned out. “Ammunition dump,” said Bat. “We got it yesterday. Must have been quite a lot from the secondary explosion we got. Have to go back to refuel now. We’ll have a bite of lunch and then we’ve got a target, I think a real good one.”

Not very long afterwards we dipped down on the little airstrip as daintily as a leaf and taxied in. I handed the pins out the window and the ground man stuck them into the holes that disarmed the rockets. And then we drifted to a fueling place and I edged my way out of my seat. The ground was a little wavy under my feet.

February 25, 1967/Saigon

It was my last night and I had reserved it for a final mission. Do you remember or did I even mention Puff, the Magic Dragon? From the ground I had seen it in action in the night but I had never flown in it. It was not given its name by us but by the V.C. who have experienced it. Puff is a kind of crazy conception. It is a C-47—that old Douglas two-motor ship that has been the workhorse of the world since early on in World War II.

The one I was to fly in was celebrating its 24th birthday and that’s an old airplane. I don’t know who designed Puff but whoever did had imagination. It is armed with three six-barreled Gatling guns. Their noses stick out of two side windows and the open door. And these three guns can spray out 2,800 rounds a minute—that’s right, 2,800. In one quarter-turn, these guns fine-tooth an area bigger than a football field and so completely that not even a tuft of crabgrass would remain alive. The guns are fixed. The pilot fires them by rolling up on his side. There are cross hairs on his side glass. When the cross hairs are on the target, he presses a button and a waterfall of fire pours on the target, a Niagara of steel.

These ships, some of them, are in the air in every area at night and all night. If a call for help comes, they can be there in a very short time. They carry quantities of the parachute flares we see in the sky every night, flares so bright that they put an area of midday on a part of the night-bound earth. And these flares are not mechanically released. They are manhandled out the open door by the flare crew. I knew the technique but I have never flown a night mission with Puff. I had reserved it for my last night in South Vietnam. We were to fly at dark and hoped to be back by midnight.Report this ad

I went by chopper to the field where the Puffs live, met the pilot and his crew and had supper with them. Our mission was not general call. A crossroad area had been observed to be used after dark recently by Charley, who was rushing supplies from one place to another for reasons best known to Charley. We were to be directed by one of the little F.A.C. planes I spoke of in an earlier letter.

Because it was hot and no wind in prospect, I wore only light slacks and a cotton shirt. We flew at dusk and very soon I found myself freezing. Puff is not a quiet ship, her door is open, her gun ports open, her engines loud and everything on her rattles. I did not wear a headset because I wanted to move about, so one of the flare crew, a big man, had to offer me an extra flight suit and he said it in pantomime. I accepted with chattering teeth and struggled into it and zipped it up. Then they fitted me with a parachute harness and showed me where my pack was in case of need. But even I knew that flying at low altitude, if the need should arise, there wouldn’t be much time to get out even if I were young and clever.

Forward of the guns and aft by the open door were the racks where the flares stood, three feet high, four inches in diameter. I think they weigh about 40 pounds. Wrestling 200 or 300 of them out the door would be a good night’s work. The ship was dark, except for its recognition lights and a dim red light over the navigator’s table.

They gave me ear plugs. I had heard that the sound of these guns is unique, so I put the rubber stoppers in my ears but they were irritating so I pulled them out again and only hoped to get my mouth open when we fired.

There was a line of afterglow in the western sky, only it was not west the way Puff flies. Sometimes it was overhead, sometimes straight down. Without an instrument you couldn’t tell up from down but my feet were held to the steel floor by the centrifuge of the turning, twisting ship. Then the order came and a flare was thrown out and another and another. They whirled down and the brilliant lights came on. We upsided and looked down on the ghost-lighted earth. Far below us almost skimming the earth, I could see the shape of the tiny skimming FAC plane inspecting the target and reporting to our pilot. We dropped three more flares, whirled and dropped three more. The road and the crossroads were very clearly defined on the ground and then there was a curious unearthly undulating mass like an amoeba under a microscope, a pseudo-pod changing in shape and size as it moved. Now Puff went up on its side. I did know enough to get my mouth open. The sound of those guns is like nothing I have heard. It is like a coffee grinder as big as Mt. Everest compounded with a dentist’s drill. A growl, but one that rocks your body and flaps your eardrums like wind-whipped flags. And out through the door I could see a stream, a wide river of fire that seemed to curve and wave toward the earth.

In May 1967, Steinbeck returned to the United States and told President Johnson what he’d seen. A second debriefing, to Johnson’s cabinet, is archived at the Department of Defense. Steinbeck returned to New York and on December 20, 1968, died of heart failure. Though he originally supported the war, Steinbeck “changed his mind totally about Vietnam” during his stay, said the author’s wife in an interview after his death.

*****

This article originally appeared in the SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE in August 2012. Here’s the direct link: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/steinbecks-dispatches-from-vietnam-3883122/

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

October 23, 2024

Truths and Myths of the Vietnam War

This documentary features videos and topics guaranteed to keep you riveted from beginning to end. If you are a Vietnam Vet, this is our future legacy! It is a must-watch for all!

This forty-eight-minute film is about the truths and myths of the Vietnam War. It was produced by veterans who served in the war. They want you to learn about the war and have provided information here for your consideration, much of it not recorded in other films or mentioned in schools or universities. We owe it to these veterans to listen to what they say about the war they served in. They consider this film to be their enduring legacy for future generations.

https://youtu.be/GjwyCaiJ0lE?si=GsQ_MkX1efGDkk2O

If you are a Vietnam Vet, how does it make you feel to be one of the 30% still alive?

If you want to read more about dispelled myths, check out these other posts on my website (use the back arrow at the top left of the page to return here:

Vietnam War – Common Myths Dispelled

4 Vietnam War Myths Civilians Still Believe

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!