John Podlaski's Blog, page 4

March 29, 2025

What was it Like to Serve in Vietnam and Afterward

My fellow Vietnam Vet and author, Robert Kuhn, discusses his service in Vietnam and what it was like afterward. It’s well worth reading.

An interview with Robert KuhnI recently hired a professional beta reader named Gabriella Michaelis to help me with my new book, Jean’s Heroic Journey. (Who, by the way, I highly recommend to any author/ writer seeking professional author services.) I was so impressed with her work that I asked her to work her magic on my older book, Rucksack Grunt, as well. Once again, she did a fantastic job critiquing the book. As it turned out, apparently, the book piqued her interest not only in the experiences that I detail in my memoir, but she also wanted to delve more deeply into my views of the Vietnam War as a young soldier and now an old veteran. She very politely and tactfully asked me some problematic probing questions about what it was like. So, I thought I’d present our Q&A exchange in an interview format as follows.

Gaby: I know that I might be asking some very personal and/or uncomfortable questions, but please know it’s not to be rude or disrespectful. It’s really because I’m curious about how you fully experienced all of these incredible, sometimes harrowing things that the average person doesn’t usually go through in their lives, especially not at 18/19 years old. At that age, I just graduated high school and went to university during a time of peace, comfort, and stability.

Bob: I am just as intrigued by you, a talented woman from a much younger generation who has a sincere interest in learning about the Vietnam War and us veterans. I welcome your questions and doubt that they will be inappropriate, but thank you for that sentiment. You can ask anything you want to. I’ll decline if necessary.

Gaby: How might you have felt fighting so far away from home ?

Bob: SCARED! Extreme fear that you learn to manage. Extreme homesickness and loneliness that you don’t learn to manage. But still, at the same time, some great camaraderie and friendships developed.

Gaby: You’ve described some terrifying moments in your book. What went through your mind aside from the fear? Did you miss home? Your family? Or were you so scared that you mostly just hoped to survive?

Bob: Yes, I certainly did miss my friends, family, and home so much of the time. But during those moments of intense fear, I can’t say that home and family were the first things that popped into my mind. But instead, a sudden defensive posture of reacting and doing whatever was necessary to defend and protect myself and my buddies. I’d have to say that eliminating the enemy threats and survival would have been foremost in our minds in those moments.

Gaby: It is genuinely impressive to know that you’ve lived through a historic event that I’ve either only read about in history books or seen a Hollywood-esque version of in the movies. I know from reading your book that it certainly was a difficult time for you guys, to say the least. You not only had to fight the enemy but also an extreme climate. It sounded like you simultaneously battled nature as well.

Bob: First, let me say that I don’t want to give the impression that it was all dire hardship and adversity 100% of the time. That would be inaccurate. We all have some humorous stories, good times, and good friends to talk about as well.

But even if just a minority of the time was frightfully perilous, that was still incredibly indelible on a young mind. Most of us were too young to be thrown into the war machine. War is a dreadful thing.

I describe a Vietnam tour as a mess of extremes. Extreme heat, extreme humidity, along with extreme monsoon rains. Extreme fear, extreme exhaustion, extreme sadness, extreme homesickness, and extreme anger were some of the emotions and state of mind.

As I wrote in my introduction, “Some had it bad and some not so bad. We all served.”

Gaby: During your time in Vietnam, were you aware of the politics behind it?

Bob: Keep in mind that I was just a 19-year-old kid. How much do teenagers really know about and understand politics? I was raised by the World War II generation. We were taught right from wrong, good -vs- evil, and so forth. The TV cowboy shows we loved to watch had the good, clean-cut guys wearing white hats against the underhanded, sneaky, bad cattle rustlers and stagecoach robbers. Superman and the other superheroes always fought for what was right. It was a pretty black-and-white concept. World War II was clearly presented as a good vs evil war. Our good American soldiers fought against the evil German Nazis and Japanese imperialists. The American public trusted our government and unanimously supported the war and jubilantly supported and honored the returning warriors.

All of that changed during the “1960s” and “1970s, ” especially among the college students and draft-age war protestors who didn’t trust the government and certainly didn’t want anything to do with that war or the draft. Eventually, populism turned against the Vietnam War and then wrongly against us warriors who were fighting the war as ordered, all of which I was certainly aware of.

Probably a more direct answer to your question regarding my awareness of politics is to state one of the government’s reasons for getting involved in that decades, if not centuries-old war. It was called the “domino theory.” If we let Vietnam fall to communism, then it was just a matter of time until the other neighboring countries in the region would fall like dominos to communism, and eventually, there would be a worldwide threat. The government presented the case as a typical good vs evil plot. Democracy and freedom vs communism. The theory was that we had to fight the evil over there BEFORE it arrived here at home in our own country. That seemed reasonable and honorable to me. So, that was a political belief I vaguely held when I went to Vietnam.

Was it all a lie? Maybe. I don’t know. Were there more nefarious corporate greed, war machines, lying government scenarios acting out behind the scenes? I don’t know. At the time, I had no clue about such a thing and never gave it a second thought. However, I will throw this out for consideration: Communism didn’t spread like wildfire, and the dominos didn’t fall. Just a thought.

I could go so much deeper into this subject now, all these years later. The controversial Gulf of Tonkin incident, the Pentagon papers leak, and so forth impacted public opinion of the war, but I believe your curiosity is more about my state of mind back then. So, let’s move on to the next question.

Gaby: I don’t mean any disrespect, of course, but it does make me curious – at this point, did you feel the war was worth all of the horrible, scary things you went through? Did you know what you were fighting for, or was it mostly a sense of duty that you meant to fulfill and get back home in one piece as soon as possible without contemplating the purpose of the war too much?

Bob: That’s a good question. The honest answer is that I didn’t contemplate the purpose of the war so much at the time. Other than, as I said, in the back of my mind, I held onto the belief that we were fighting against communism and saving the Vietnamese people from it, but like I said, those thoughts were in the back, not the forefront. However, just like here at home, not everyone agreed with that thinking. I have heard other guys ridicule such notions while we were there in the country. However, I chose to hold onto those sorts of beliefs to attempt to maintain some sanity, which, to a certain degree, failed in the end. I attribute that failure not only to being exposed to war but also to the country’s lack of support and disdain for the war and for us as returning soldiers.

The bottom line for me is that I did my duty to the best of my ability and just wanted to survive and return home again.

Gaby: Were you aware while there that the war was winding down? How much of that sort of news did you receive or know about? Did the military leaders keep you informed?

Bob: During my time there, we were isolated from the news, especially as infantrymen. For the most part, we didn’t have access to much news besides what we received in our letters from home. Which really wasn’t the focus or purpose of the letters. But we were all aware of the war protests and marches at home that had occurred before our tours of duty began and were still ongoing. I’ve heard it stated that the military is a microcosm of society. I believe that was especially true at that time in history because a large portion of the Army comprised civilian draftees. Even though the divisive political unrest occurred thousands of miles away, it still had an effect on the troop’s morale and attitudes. However, to answer your question, I can’t say that knowing about such things translated into equating those events to the timing of the war ending. The war seemed never-ending. But to me personally, I knew my tour would eventually end one way or another. The American’s part in the war continued winding down for another year after my tour ended.

Gaby: I respectfully understand if my questions are too sensitive, painful, or personal for you to answer. My questions are purely out of personal curiosity. I was wondering about your sense of what kind of impact the war made and what your reflections might be now that you look back on it. Was it worth it?

Bob: I’ve generically addressed much of this question already, so I’ll focus on just the part of the impact on me personally.

The short answer is LIFE ALTERING. For me personally, as a young man of 18-19 years old, it was a life-altering trauma. Life-long, I should say.

Two years after our troops left South Vietnam in 1975, I watched the fall of Saigon on TV. That had a huge impact on me. I felt immense sadness and anger while contemplating all of the efforts and sacrifices that our government and military demanded of us for all those years. It was a hard gut punch feeling that I had back then when Saigon fell.

In addition, coming home to an unwelcoming society that called us murderers and rapists, and baby killers was an unforgivable ignorance that was prevalent here at home in our country. They unfairly ignored that we were called upon to serve our country, which is what we did. That horrific attitude probably caused as much damage to our psyches as the war experience itself did.

Some veterans handle the war effects and memories better than others. For me, the war experience unwantedly became a part of my essence. Not a day goes by when it does not intrude into my thoughts.

“Was it worth it?” There it is! A question that I should decline to answer. On a national level, I don’t know the answer, and stating a controversial opinion really serves no purpose, so I’ll leave that part up to the macro geopolitical gurus. However, personally, I feel that my service was absolutely worth it. Even though I’ve had to deal with a fair amount of ongoing physical and emotional adverse fallout from it throughout my lifetime (all veterans do), for me, the benefit outweighs all of that.

“How do I view my service when I reflect on it?” That all depends on the decade. In the early years after the war, I was angry and bitter. Still, as I aged and as a society, for the most part, has reversed its travesty injustice against military veterans, my view has definitely improved. Most of the country now recognizes and has tried to reconcile and make amends, not necessarily for the war, but for the veterans. I am not one to say, “Too little, too late.” I welcome the change. It took many years to get to this point but I am proud to have served.

Last Veterans Day, my grandson, as part of his class project, nominated me to be inducted into their school’s “Hall of Heroes.” I was reluctant to participate, but I saw a valuable opportunity to show the younger generation that it was an honor to have served our country, so I decided that I should be present as an example for the kids. I pray that they are never called to go to war but rather experience peaceful patriotism instead.

I am struggling to adequately describe what a fantastic experience it was to do my duty that day (for the kids) and stand proudly front and center on the fifty-yard line with six other veterans of various ages (I was the old guy!) We were each called up individually to stand next to the master of ceremony speaker as he read a short bio clip of our military service. It was quite an experience to be honored in front of a high school football stadium crowd. I’d like to add that the event wasn’t during a football game but was solely a Veterans Day event for which the audience turned out.

I’m looking forward to attending this year’s Veterans Day ceremony to support the next batch of veteran inductees, although I’m glad I’ll be doing so from the bleacher seats this time.

I would encourage other veterans to step up and be recognized if they have an opportunity.

Gaby: I welcomed the opportunity.to speak with you about all of this, and I appreciate your candid answers to my questions and curiosities. It’s an honorable feat to have served your country. Thank you.

Bob: It was my pleasure to interview with you. Thank you, Gaby.

Gabriella Michaelis, author and up-and-coming editor extraordinaire.

If you are interested in reading more of Mr. Kuhn’s work, check out his earlier submissions on my website and my book review of RUCKSACK GRUNT:

https://cherrieswriter.com/2021/06/27/am-i-a-real-vietnam-veteran/

PTSD is an Honorable War Wound!

MY BOOK REVIEW OF RUCKSACK GRUNT:

Book Titles N – R*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 23, 2025

The First Tear

Perry Walker served in the Marine Corps from 1966 to 67 in Vietnam. He wrote a short story (poem) about his first experience with a PTSD counselor. I’m sure many of us can relate. Check it out!

by Perry Walker

The outer office was small, the white door melded into the woodwork almost unnoticeably. The walls are almost bare except for a large clock, it’s ticking loudly, reminding one of tapping at the door. The hands long, stretching out, seeking the black numerals to no avail. Beside the quiet door, a fish tank, its inhabitants lazily moving to and fro, constantly moving, yet going nowhere. Their large eyes unblinking, staring forward almost as in a trance. To my right, the entry door. Large, unyielding.

I felt my palms, wet with perspiration. My mind, racing with fear, anxiety, and questions. The clock on the wall, the ticking louder now. The door, my only escape, seems larger, more opposing, more intimidating. What question will he ask, what memories will he stir, what pain will he bring.

I gently rock, my padded chair squeaking in protest. My eyes darting around the room, yet always back to the door. The clock pounding now, yet yielding no time. The fish, hanging there, frozen in time. The dark door, my only egress to safety. That damn door, larger now, mocking me, that damn door.

The silhouette of a man, “beckons me”. The room is larger, darker, warmer. The silhouette sat back, a dark bookcase framing his body. My eyes flicked left to his accomplishments hanging dryly on the wall. Then to the right is a clock quietly staring back at me. And now to my rear, dark, foreboding almost hanging above me, looking down as a predator might, was the door. I felt my body begin to “buzz”, my hands wet as I wring them together and the ringing in my ears almost deafening.

I stared at the floor waiting for the silhouette to speak. I lost focus as my eyes began to well with tears. What memories, what visions so long buried would he evoke.

I felt my lips start to quake, my eyes darting around the room trying vainly to seek escape. “I understand you served in Viet Nam?”

My eyes stopped searching. My hands stopped wrenching. I froze. The silhouette asked again “I understand you served in Ve” A disembodied voice, soft at first, unsolicited,

“Yes, yes I did”

“What brings you here today?”

I’m staring at the floor, my eyes begin to water and my mouth is dry and quivering. I hear the voice again. Even softer than before. “I didn’t do enough”

The silhouette, “you didn’t do enough of what?”

The quiet voice, “I didn’t do enough, they died anyway.” Then I felt the first tear as it fell upon my hand.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

Goat Patrol

by Gary Jacobson © 2002

In Vietnamese jungles darkening lush

Seven soldiers from their company thrust

Set up a “goat” ambush under starry twilight

That did the seven bedight

Along a road Vietcong traveled late at night

Moving supplies and fighting men

Along a network trail called Ho Chi Minh

Alongside a trail lying deep and still

O’er rock and o’er rill.

In blackened midnight coat,

Set seven men on ambush goat

Lying in a prone foxhole

Their whole existence in a scooped out bowl.

Feeling the weight of a war full of cares

They set out trip-flares

To warn

The seven warriors forlorn

When Charley in fevered night did roam

Journeying into fragrant night far from home.

The soldiers positioned a claymore mine

To cover with blistering hell the trail-line

Then made themselves hidden to wait in the meantime

Setting back, waiting to ruin Charley’s whole day

To shove back at him this hateful fray

This death on soldier’s minds for an eternity will play.

Under paling light of midnight moon

Dreaming sweet thoughts of death and doom

I slept dark and dreary

Till before my eyes weary,

Came an apparition vaguely bleary

Of hateful war passing dimly..

Hazy night swum by ever so slowly,

As I sweat crazily

Tossing

Turning

When suddenly the sleeping night exploded!

Yellow lightning sparkled!

The trip flare set to warn of danger burst

Leaving beleaguered soldiers foreboding worst.

Sparking automatic rifle fire hot and furious

As my sleeping senses recoiled

As thunder in my beleaguered head roiled

As the whole night around me boiled,

The jungle night filled with things moving

Scrabbling quick-time helter-skeltering.

Specters of death riding midnight air

Filling anguished souls with fearing despair.

Malevolence arousing a seeping anger seething

VC like a bee hive madly swarming.

Only half awake I alligator crawled

Past my line like one possessed slithered

Wriggling on my belly like a reptile

My M-16 cradled in crossed arms style,

Yards from my hole,

The devil seeking my soul,

Crawling like a June bug exceeding fast

With determination I had bypassed

Our prone foxhole’s security

Straight into the mouth of Hell in a Hurry,

Straight into killing zone’s fury

Crawling twenty yards, maybe more,

Into the mouth of VC guns roar.

Straight for the Vietcong I was heading

My frontal assault mounting

At those graciously,

Most welcoming,

Vietcong

Until a bell sounded in my head, DING DONG!

I still hear that hatefully awful sound

VC bullets pocking ground

All round.

Quite suddenly I awoke…

And when I awoke,

I thought someone had played a cruel joke.

My buddies with the sincerest deep felt caring

Started yelling, Started swearing

Get your a__, uh, er, newbie self back

What you doing you sad sack,

At the Vietcong making a frontal attack?

Boy, you’re not where you belong!

Unless you want to sing death’s discordant song!

Well of that night I lived to laugh and tell,

How I almost tripped to hell

Tho still when I listen soft for a spell,

I can hear the devil’s fevered knell.

Next time… You’ll be mine…

For Me and the Vietcong

Are just waiting for you to again step wrong…

So I’ll get you yet! On that Sky Trooper, your bottom dollar bet!

March 15, 2025

The Sweetest Sound (a poem)

The author served as a line Grunt and Scout/Sniper in Nam. I’m enclosing a poem he wrote about his Dust-off. May God always hold in his loving hands the living and dead of those aircrews, for if it were not for them, he would not be here today.

The Sweetest Sound*

Not songs of choice nor lover’s voice will ever compare

To the sweet sound of rotor blades as they beat through thick, humid air

I am a Vietnam vet. I served in the Infantry

The word Grunt refers to men like me

I have seen war at its worst and men at their best

Sadly, I’ve wrapped brothers in ponchos and sent them to their final rest

Now, many years later, as I lie here in bed

The visions come back to race through my head

The scars on my body will forever remain

As I touch them, once again, I feel the pain

Once again, I find myself on the ground

With blood, my blood, all around

As I lay there in unconscionable pain and fear

Came the sweet sound of rotor blades as my Dust-Off drew near

When, at long last, I reach my final day

I will look back on my life and say

I’ve heard beautiful songs of choice and the sweetness in my lover’s voice,

And yet, these cannot compare

To the sweet, sweet sounds of rotor blades

As they beat through thick, humid air.

*By Ernie Smiling Hawk, approval to use obtained from Jim Van Doren

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 9, 2025

“ALL GAVE SOME, SOME GAVE ALL”

My friend Jack McEncroe contacted me in response to a question I posed on my website: “Why did Vietnam Vets return home differently?” He included a speech he gave when the Vietnam Veterans Moving Wall visited in Kellispell, MT a few years ago, which he feels answers it. A must read…

I am humbled and honored to be standing here surrounded by magnificence. Yes, the magnificence of the Flathead Valley but, more poignantly this morning, I am speaking of the magnificence of some of your friends and neighbors. This morning we are addressing the magnificence of sacrifice, the magnificence of duty, honor, country, the magnificence of freedom, and the magnificence of those who keep us free.

Maya Lin was a 21-year-old graduate student when she captured all of this magnificence in her vision. Her vision became a reality and it is now known as The Vietnam Veterans Memorial or reverently referred to simply as “The Wall”. It is the most often visited Memorial in Washington DC. In 2015 alone, approximately 5.6 million people visited what all Americans should think of as sacred ground.

Allow me to transport you back in time to a period of perceived bliss in America when we first learned of Television, Rock’n Roll, Disneyland, American Bandstand, Elvis, and Camelot. The Korean War was behind us and clear skies were ahead. Nobody locked their doors, the news was the actual news, neighbors helped neighbors, children were to be seen and not heard, and respect for authority, self sufficiency, and manners were the law of the land. I know, I thought the same thing, what the hell happened? The ’60s happened and it was during the early ’60s that most Americans first learned of a place called Vietnam.

In the mid-’60s Vietnam became the focus of every American family. America was becoming increasingly involved in a war there, and for all able-bodied young American men our opportunity was now.

Yes, there was a draft but contrary to popular belief, 2/3 of those who served in Vietnam were volunteers, as once again young Americans banded together and became brothers-in-arms. We fought for one another and mission accomplishment and, for that opportunity, we are eternally grateful. I am convinced that the most often heard prayer from those going into combat for the first time is “Please, God, don’t let me let my buddies down”. It is never about self but rather about those next to us and, most importantly, those entrusted to us.

The challenges were many as this was a war like no other. The enemy was often unrecognizable, your allies during the day became your enemy every night, there were no front lines, the climate was horrible, every creature that slithered, bit, sucked, or stung inhabited this place. One would not be dry, clean, or safe for a year or more, and it seemed everyone, including those you were trying to liberate and protect, was trying to kill you. Yes, the challenges were many, but none were too tough that they would not be overcome.

Please keep in mind that the military does not start wars, politicians do. Our President made a decision and our military and the youth of America were once again called to action. Our job is to fight and win, and win we will. Sadly, most national politicians are weak and beholden to benefactors instead of honor and principle. They undermine those they send into battle and this was no exception as they constantly revised The Rules of Engagement to your detriment. They left you more vulnerable and, in fact, actually protected the enemy. Another challenge to be overcome, and overcome it you did.

However, unbeknownst to you, the ’60s culture was sowing its seeds of deceit and destruction back home and, sadly, that is a challenge America has never overcome. There were many legal and honorable deferments to military service and I am not referring to them in any way when I speak of the rebellious culture that came of age in the later ’60s.

This was a culture spawned in academia and promoted by a suddenly compliant media, draft dodgers—- also known as cowards disguised as war protesters—- and self-serving politicians. This cabal of dissidents has affected everything in America for the last 50 years and, in my humble opinion, is the ideological foundation for many of America’s problems today. This same culture still manifests itself today when the self-anointed privileged find themselves in the minority. Imagine The Vietnam Veteran’s disgust when some of this trash was actually elected to national public office years later.

I briefly described for you the conditions our young men and young nurses faced in combat on the ground, but I have just scratched the surface. The filth, mud, swamps, rice paddies, tunnels, booby traps, poison punji sticks, mines, mortars, rockets, grenades, creatures, Agent Orange, and stifling weather made for miserable conditions but were no match for our magnificent young Americans.

Please remember my earlier reference to the fact that there were no front lines. Terror and devastation could come from any direction, including below, in the form of tunnels and underground facilities, 24 hours a day every day. Imagine the horror our young nurses, fresh from Nursing School, witnessed every minute of every day. This horror was inflicted on our young fighting men, many of whom were the same age or just slightly younger than the nurses treating them. Yet, our young fighting men prevailed and defeated the enemy in every major battle they were involved in.

In World War II, the average days of actual combat that our ground troops faced in a year was 44. In Vietnam, the average days of actual combat our ground troops faced in a year was 240. Whether you were on the ground, in the air, or on ships at sea, excellence was required 24 hours a day every day. I tell you this only to underscore the aforementioned and often unrecognized magnificence of our Vietnam Veterans.

Allow me to repeat, our young fighting men won every major battle they were asked to win and that included the devastating defeat they handed the enemy in TET 1968. Surprised? We were too when we came home to hear that Walter Cronkite, “the most trusted man in America”, had reported otherwise. In other words, he was not telling the American people the truth. This major and convincing defeat of the enemy was somehow reported as a politically convenient stalemate.

It was paraphrased that Cronkite spoke for “many Americans” when he declared, upon return from the battlefield at Hue during TET of 1968, that the bloody war in Vietnam was destined to “end in a stalemate.” The term “Many Americans” of yesteryear is analogous to today’s “unnamed but well-connected sources”. This is a convenient way for politicians and the media to deceitfully promote their hidden agenda, which is never good for America or Americans.

I have described the hell hole our young men and women found themselves in 7300 miles from here. I have shared their undeniable accomplishments, their magnificent valor and, in the case of the men and women whose names are on this sacred Wall behind me, they gave all they had to give for all of us.

Recreating the fabricated and politically charged homeland the Vietnam Veteran returned to is impossible unless you experience it through their eyes. We can, however, try to imagine the confusion and frustration a returning Veteran might experience in hearing that the majority of his countrymen believed he lost a war that he knew we won! He was falsely accused of being a baby killer, labeled a misfit, told by superiors not to wear his uniform due to the animosity of his countrymen, and he was even unwelcome in some Veterans’ circles.

Vietnam Veterans found that their Country had been fed lies and its thought process was poisoned by academia, the media, the aforementioned cowards, and the likes of the John Kerrys, Tom Haydens, and Jane Fondas of the world. In short, they were made to feel unwelcome in the very Country they had risked everything for. They faced a citizenry who had been deceived by this cabal of cowardly dissidents, lying media, and opportunistic politicians. Another challenge and another victory. We turned to our Band of Brothers and to like-minded patriotic Americans. Together we have prospered in every way imaginable.

I have shared a brief overview of the conditions our Vietnam Veterans faced. For those fortunate to return home, they returned to a far different America than they left, and they returned far different Americans than those who left 12 or 13 very long months earlier.

For the living, this Wall behind me and that beautiful Wall in Washington, DC, validates the Vietnam Veteran’s sacrifice, initiates the closing of the healing loop, and says “well done”.

For those whose names are on The Wall, that healing is never ending for our Gold Star Families. These magnificent men and women gave all of their tomorrows for all of our todays. Let me repeat that: These magnificent men and women gave all of their tomorrows for all of our todays. Yes, we really are a grateful nation, but there are no words that adequately express our gratitude for their sacrifice and that of their family and friends. We are eternally in your debt.

I ask all of our Gold Star families to please stand if able and remain standing. I ask all of the Vietnam Veterans to stand if able and remain standing and, if not able, please raise your hand.

Today provides us an opportunity, an opportunity many Americans never embraced. Today we are here together, surrounded by this aforementioned magnificence. Yes, ALL GAVE SOME, SOME GAVE ALL.

Today is a gift, a gift from God, and through Him a gift from those on The Wall, a gift from our Vietnam Veterans, and a gift from all of our Veterans. Today is one of those gifts, and another opportunity to say thank you, welcome home, well done.

God Bless all of our Gold Star Families, God Bless all of our Veterans, God Bless our generous sponsors and all of you for joining us this morning, and God Bless the greatest Country on earth, The United States of America.

Jack McEncroe, Captain, U.S.M.C.

So, your thoughts…

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

March 2, 2025

Left Behind

Why must the government keep so much information classified for so long? This family is still getting the runaround for a loved one lost during the Vietnam War. It’s lengthy, but well worth reading.

The tragic story of an American spy plane with the radio call sign Baron 52 began like so many other midnight missions over Indochina.

Shortly after 11 p.m. on Feb. 4, 1973, the plane left a Thai air force base with a crew of eight whose mission was to eavesdrop on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, North Vietnam’s shadowy, serpentine jungle artery for moving soldiers, tanks, arms and supplies south.

At 1:25 a.m., the flight crew of the EC-47Q radioed Moonbeam, an airborne command and control center, that several artillery rounds were fired at the plane over southern Laos, but it was not hit. Fifteen minutes later, the flight crew reported that the plane was taking on heavy anti-aircraft fire. It was the last time anyone heard from Baron 52 before the converted cargo plane fell out of the sky and landed in the dense Laotian jungle.

But this was no routine shootdown. Only eight days earlier, the United States and its South Vietnamese allies had signed the Paris Peace Accords with North Vietnam and the Viet Cong. A key part of the pact was that the North Vietnamese would return hundreds of U.S. prisoners of war—and the first POWs were set to be released in seven days. The last thing the Americans needed was an international incident to complicate or even nix the deal.

“From the beginning, it was embarrassing to the U.S. because the peace treaty was signed and American prisoners were about to be released—and then all of a sudden there’s a spy mission over the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” recalled former New Hampshire GOP Sen. Bob Smith, who was vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs in the early ’90s.

President Richard Nixon announced the preliminary approval of a peace treaty aimed at ending U.S. involvement in Vietnam on Jan. 23, 1973, four days before the agreement was signed. (White House photo)

The downing of the reconnaissance plane set off a series of events shrouded in mystery, intrigue, alleged coverups and never-ending questions that remain unanswered today, even as the U.S. gets ready to mark the 50-year anniversary of the ignominious fall of Saigon to Vietnamese communists on April 30, 1975.

To shine a light on the vexing case, The War Horse spent the past two months reviewing hundreds of military and government documents—many of them once top secret and now declassified, or simply gathering dust on archival shelves and never publicized before.

The tale that emerges from the documents, oral histories and video testimonies is one of bureaucratic intransigence and inattention—and one American family’s half-century quest for accountability and truth. The story also drives home the magnitude of the gnawing pain of the families of the nearly 1,600 Americans still listed as “unaccounted for” from the Vietnam War.

CIA’s Secret WarWhat made the aftermath of Baron 52’s fiery demise even more mysterious was that landlocked Laos during the Vietnam War was the “black hole” of Indochina. The technically neutral country was where the CIA had directed a secret war from the early ’60s to prevent the spread of communism in Southeast Asia by countering the influence of the Pathet Lao, a political and military organization allied with North Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

Baron 52 was shot down in Laos about 20 miles from the border of South Vietnam. The bare area at right is the site of the crash after it was excavated in early 1993, the 20th anniversary of the shootdown. (Graphic by Hrisanthi Pickett of The War Horse)

An aggressive search for Baron 52 involving a flock of U.S. planes was launched 15 minutes after its flight crew didn’t check in with Moonbeam at two a.m. But it took two days to locate the plane in a mountainous region of Laos, about 20 miles from the border of South Vietnam. From the air, search crews reported, it appeared that the plane had fallen to earth, bounced once, landed upside down and burned.

On Feb. 9, a Sikorsky HH- 3E Jolly Green Giant helicopter lowered three Air Force parajumpers and a communications specialist to investigate the crash site after at least one missile was fired at the helicopter. While two of the parajumpers set up a security perimeter, the other two men examined the wreckage. They found the bodies of three members of the flight crew, still strapped into their seats in their fire-resistant Nomex flight suits. And the team found another body partially underneath the fuselage.

The wreckage of Baron 52 was spotted by U.S. Air Force search-and-rescue crews two days after the spy plane crash-landed in a mountainous region of southern Laos. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force)

But there was no sign of the other four crew members in the main cabin: the navigator and the so-called backenders who operated the sophisticated eavesdropping equipment. The search-and-rescue team determined that all the equipment had been destroyed in the fire. But in part because team members feared booby traps, they didn’t enter the fuselage to sift through the wreckage to look for evidence of the backenders’ demise, such as shredded pieces of Nomex suits. And because one of the mission’s two helicopters was running low on fuel, the search-and-rescue team spent only about 40 minutes on the ground and was able to retrieve the remains of only one of the pilots, 1st Lt. Robert Bernhardt.

Officers at the Front DoorA couple of days later and half a world away on New York’s Long Island, Sgt. Joseph Matejov’s 15-year-old sister, Mary, the sixth of 10 children of Stephen and Mary Matejov, was home sick from school when she peered out the window and spotted two uniformed Air Force officers walk up to the front porch and ring the doorbell.

She had seen similar scenes at the movies and immediately knew something terrible had happened to her fun-loving brother Joe. She told the officers her mother wasn’t home, so they waited in their car for her to return.

“I didn’t even know he was over in Vietnam,” said Mary Matejov Salzinger, a retired nurse who now lives in Portland, Oregon. “I only knew that he was based in Thailand and that I was glad the war had ended without him having to go to Vietnam.”

The Matejov clan in the front yard of their home in East Meadow, N.Y., circa 1969. Top row (left to right): Steve, John, and Joe. Middle row: Kate, Anne, and parents Mary and Stephen. Front row: Theresa, Judy, Mary, Jim, and Mike. (Photo courtesy of Matejov family)

The news of the fiery crash shattered the Matejov family, but a letter from Col. Francis Humphreys, commander of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing, based in Ubon, Thailand, offered some hope.

“I feel that there is a possibility that one or more crew members could have parachuted to safety,” Humphreys wrote to Joe’s parents on Feb. 13.

But the Matejovs’ hopes were crushed when they received a letter dated Feb. 24 from Humphreys saying he had reluctantly concluded that all eight men were killed in the crash.

“A careful review of all available facts has been made and there is no reasonable doubt that there were no survivors,” Humphreys wrote. “Due to the severity of the crash, the apparent total destruction of the aircraft, the intense fire and the fact that no contact of any kind was established with any member of the crew, the decision was made to declare your son killed in action.”

‘Conclusive Evidence of Death’The decision was questioned from the start. Many of the U.S. airmen at the Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base felt there wasn’t enough evidence to declare the men in the back of the plane dead because Air Force regulations authorize commanders to make a killed-in-action determination only when “conclusive evidence of death” is obtained at any time during the search.

Then, on Feb. 28, the U.S. State Department sent a to its embassy in Vientiane, the Laotian capital, making it clear who should be included on the POW lists being provided to the political wing of the Pathet Lao and the International Committee of the Red Cross. The telegram listed the names of the eight Baron 52 crew members—but it said they “should not be included.”

Sgt. Joe Matejov and his mother, Mary, in front of their Long Island home during a leave after he enlisted in the Air Force after high school. At right is Joe and his father, Stephen, who retired as an Army major after earning a Silver Star for valor in the Korean War. (Photos courtesy of Matejov family)

The Air Force quietly encouraged the Matejovs and the families of the other backenders to hold funerals to help bring about some closure. But the service for Joe, who had turned 21 three days before Baron 52 went down, did little to ease the family’s grief.

The pain felt unbearable when the family watched the joyful, emotional televised scenes on airport tarmacs showing the children, sisters, brothers and wives of returning POWs greeting the men over the next several weeks.

John Matejov, 13 months younger than his brother, felt like he lost part of his soul. Joe and John had been inseparable. The duo had always shared a bedroom and, after they became rambunctious teenagers, would often climb out the bedroom window in the middle of the night to create minor mischief in East Meadow, the sleepy suburban town where they grew up.

After the funeral, the family tried hard to get back to their lives. Some of the Matejov kids went off to college, others to the military.

The oldest sibling, Steve, had joined the Navy, and John the Marines, following in the footsteps of their father, a West Point graduate who earned a Silver Star for valor in the Korean War. After the Baron 52 crash, Theresa went to West Point to begin her Army career.

Sgt. Joseph Matejov was nicknamed Kiwi by his Air Force colleagues because he was admired for his “spit and polish.” Kiwi Shoe Polish is a global brand originally developed in Australia. (Photo courtesy of Matejov family)

“We closed our ranks and began a new life as best as we could,” John said.

Then, one summer morning in 1978, investigative journalist Jack Anderson dropped a bombshell.

“Pentagon officials realized this within days of the crash, yet the Air Force never told the families of these men that their loved ones were probably alive,” Anderson reported.

The families of the backenders were shocked. Joe’s mom ripped the “My country right or wrong” bumper sticker off her car. And the Matejovs and other relatives of the backenders began writing members of Congress, questioning the accuracy of military reports and confronting Pentagon officials.

Eventually, the military released the details of the intercept Anderson’s staff had dug up. The documents showed that a U.S. reconnaissance plane flying along the coast of South Vietnam had picked up a communique about six hours after the crash of Baron 52. “Presently Group 210 has four pirates,” a communist soldier reported. “They are going to the control of Mr. Văn. They are going from 44 to 93. They are having difficulties moving along the road.”

In the following months, as all 591 American POWs were gradually released, numerous Air Force officials continued to express serious doubts that the decision to declare the entire crew of Baron 52 dead was the right one.

Even Humphreys seemed to be hedging his bets, conceding in an April 7 letter to Matejov’s family that his decision was partially based on “a certain amount of conjecture in trying to visualize the events as they took place.”

April 1973 letter from Col. Francis Humphreys to Sgt. Joe Matejov’s parents.

Air Force Col. Lionel Blau had been one of the first to ring the alarm in mid-February 1973. Then a captain who was the operations officer with the 6994th Security Squadron, Blau had the high-level security clearances to examine the intercept and photos of the plane wreckage. He thought Humphreys needed to know exactly what he knew.

“I went in and simply told the colonel, ‘Please do not make that decision yet until we can get straightened out what this [intercept] is about,’” Blau said in a 2023 interview with John Bear, a Colorado researcher and host of the Stories of Sacrifice podcast who volunteers much of his free time to use his forensic genealogy skills to track down the remains of MIAs from past wars through DNA testing.

“I remember very well standing in front of Col. Humphreys and telling him that we had information that indicated that our four guys were still alive, and that I would be glad to show it to him if he would get a top-secret” clearance, Blau told Bear. “And he said, ‘I had one, but I don’t have it now, and I don’t want one.’”

Undeterred, Blau then asked Humphreys to at least let him show him how the plane actually landed in the jungle.

“It did not come in nose first, I told him,” Blau said, contradicting the assessment of the search-and-rescue team that the World War II-vintage EC-47Q plummeted to the ground vertically. “And he said, ‘I’ve flown them, and once they start spinning, nobody’s going to get out. I said, ‘Colonel, that plane was not spinning.’ It came in straight [and horizontally]. The frontenders were still flying that airplane when it came in. And he said, ‘Nope.’ I said, ‘There is no way that they were all KIA at that site.’ He absolutely refused to listen to me.”

A few days later, Humphreys recommended to his higher-ups that all eight Baron 52 crew members be declared killed in action.

The Four-Page MissiveFirst Lt. Michael Moore might have been killed as well. He was originally on the flight manifest. But at the last minute he took an emergency leave to fly back to Sacramento, California, to be with his wife, Betty, who was having a biopsy for suspected thyroid cancer, according to the Moores’ daughter, Heather Moore Atherton, who lives in nearby Rocklin.

Lt. Bernhardt, the only Baron 52 crew member whose remains were retrieved from the crash site by the search-and-rescue team, took Moore’s place.

After returning from the war, Atherton said, her father struggled for decades with depression, and she always suspected “it was more than just survivor’s guilt.”

Two years after he died in 2017 at age 69 of kidney disease caused by Agent Orange poisoning, Atherton and her mom had a locksmith crack open his safe and discovered the source of his darkness in the safe’s internal chamber.

Moore had left behind a four-page missive about the events surrounding Baron 52 that she found disturbing, said Atherton, who shared her dad’s note with The War Horse, the first time it has ever been made public.

Lt. Michael Moore bared his soul in 2008, but kept his written thoughts about the tragic crash of Baron 52 locked in a safe.

Before her dad flew back to Thailand, he was relieved to find out his wife didn’t have cancer. But the feeling of relief was short-lived. When Moore stopped at a post exchange in the Philippines on the way back to Thailand, he was shocked to pick up a newspaper and learn about the crash.

The 361st Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron posed for a group photo at the Ubon Royal Thai Air Base in April 1973, two months after Baron 52 was shot down. First Lt. Michael Moore, in the Tom Cruise sunglasses, is the second from the right in the second row. (Photo courtesy of Heather Moore Atherton)

And when he arrived back at the base, he found the rank and file in open revolt because they thought the Air Force had taken too long to reach the crash site and believed some of the men may have either parachuted out of the plane or survived the crash and walked away from it.

Some members of Sgt. Matejov’s squadron, Moore wrote, were refusing to fly because they believed the Air Force had made the decision to leave men behind out of political expediency.

When Humphreys presented Moore with a report on the crash that concluded all eight were killed, he was asked to sign it. He refused because he considered it “inaccurate and speculation at best,” contrary to intelligence reports and “a serious betrayal of these men and effectively a ‘death warrant’” for them, he wrote in the missive.

But the commander told Moore it was a “direct order,” so he eventually gave in and signed the report.

“I was forced into becoming a part of the conspiracy to cover up the fact that some crew members bailed out,” he wrote.

Missing Cargo DoorAtherton, who believes her father wrote the words in 2008, said finding the note inspired her in 2020 to join the Matejov family’s decades-long fight to have Joe declared MIA rather than KIA. That, the family says, would allow U.S. POW/MIA officials to treat the case more seriously and investigate the many remaining questions.

John Matejov, a Wyoming resident who had taken over the all-consuming family battle after his mother died of a stroke in 2010, had declared himself “done” just months before Atherton introduced herself over the phone a decade later. But her intense interest in the case inspired him to keep going.

First Lt. John Matejov, pictured here in 1986 when he was stationed with the 27th Marine Regiment in Twentynine Palms, California, says his family “closed our ranks and began a new life as best we could” after his brother Joe’s spy plane was shot down over Laos in February 1973. (Photo courtesy of Matejov family)

In a 1989 Air Force oral history project, Chief Master Sgt. Ronald Schofield, the communications specialist on the search-and-rescue team, said he had changed his mind and no longer believed all of the Baron 52 crew members had perished in the crash. His conversion came when he remembered that the cargo door was missing from the plane when he searched the wreckage.

“These aircraft flew with the doors on. If that aircraft had crashed with the door on, there would have been a little bit of it left at the top,” Schofield said. “There was absolutely nothing. It was gone. It looked like it had been kicked off.”

Roger Shields, the deputy assistant secretary of defense for POW/MIA Affairs at the time, told The War Horse that the shootdown of Baron 52 had jolted U.S. officials involved in POW issues because it indicated the likelihood of U.S. service members being captured after the ceasefire was already in place.

“I had not encountered an intercept from the enemy that so closely described a loss that we knew had occurred,” Shields said from his Florida home. “It was unique.”

He insisted “there was no pressure from the defense secretary or from me—or anybody who had the authority to speak for the department—to declare those men dead,” he said. But he acknowledged that “some individuals in DOD may have tried to apply pressure by speaking for themselves.”

“If anything,” he added, “it could be said that I was the source of pressure in the other direction, with me telling the secretary of the Air Force: ‘I don’t think you’ve made a good decision.’”

But Shields said he was reluctant to get involved because he was outside the chain of command. “It wasn’t my call,” he said.

Jubilant American POWs cheer as an Air Force C-141 Starlifter took off from Hanoi’s airport on March 28, 1973. (Photo by Air Force Sgt. Robert N. Denham)

The POW/MIA issue reached a crescendo in the early ’90s when the Clinton administration moved to end the punishing U.S. trade embargo against Vietnam and establish diplomatic relations with its former enemy. As part of that process, the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs held hearings for 14 months beginning in November 1991.

Massachusetts Democratic Sen. John Kerry, a Vietnam vet who had turned against the war, chaired the committee. New Hampshire Sen. Smith, like Kerry, was a Navy vet who served in Vietnam, and was the vice chairman.

Kerry was allied with Arizona GOP Sen. John McCain, who spent more than five years in the Hanoi Hilton as a POW after his Navy plane was shot down in 1967. Both men were determined to forge a new relationship with Vietnam to heal the wounds of the past.

That left Smith as a counterforce. He became a passionate advocate for the families of service members missing in action, calling for full transparency and government accountability.

When Smith asked Robert Destatte, a senior analyst at the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, about the “four pirates” intercept, he claimed it had nothing to do with Baron 52. He said as far as the agency could tell, the “pirates” had been captured near Vinh, a city near the coast in North Vietnam that is about 240 miles away from the Baron 52 crash site.

Destatte said the intercept happened at a time when there were at least three South Vietnamese army helicopters down in an area where captured prisoners would have been routed through Vinh.

“And in fact, a personal friend of mine who was a pilot in the [South] Vietnamese Air Force is aware of a friend of his who was the pilot of one of those helicopters. He is aware that the friend, in fact, was captured with his crew and moved to North Vietnam,” Destatte said at the hearing.

It was the only time the Matejovs heard about that theory from anyone in the Defense Intelligence Agency.

Tracking Down Mr. VănBear, the Colorado researcher, believes he might have unraveled the mystery surrounding Mr. Văn with the help of some trusted intelligence sources.

The linguists who translated the radio transmission in February 1973 might have assumed it originated in the Vinh area because the 210th AAA Regiment was historically assigned there, Bear said. Scrolling through a Vietnamese website dedicated to documenting the history of the Ho Chi Minh Trail, Bear discovered that the regiment also fought in the general area of the Baron 52 crash site.

In Vietnam, Văn is an extremely common middle name for males. But it is rarely a given name (which comes last in the Vietnamese order).

The unusual name made it easier for Bear to track down the name of Lương Khánh Văn, who was a political officer of the North Vietnamese army’s 377th Air Division, which oversaw the 210th AAA Regiment, according to CIA records declassified in 2009. Bear found Văn and his division listed on the Ho Chi Minh Trail website.

On Feb. 15, 1973, 10 days after Baron 52 was shot down, the 210th was just south of the crash site near the town of Attapeu in Laos, according to the CIA document.

The reference to “44” in the intercept could have been a reference to Binh Tram 44, which was only about 15 miles from the crash site, Bear said. Binh trams were self-contained military units that oversaw a specific segment of the Ho Chi Minh Trail and were responsible for, among other things, logistical support and air defense.

Americans and Laotians joined forces in early 1993 to excavate the Baron 52 crash site.

A Tooth, Four RevolversA joint U.S.-Lao group in 1993 conducted an excavation of the Baron 52 crash site around the 20th anniversary of the shootdown. Among other items, the excavators found five lap belt buckles (only three in the locked position), a tooth, three dog tags, and four of the crew’s service revolvers.

The initial report on the excavation said 23 bone fragments were discovered, but that number varied wildly in follow-up reports. Unexplained discrepancies were a continual problem in the Baron 52 documents examined by The War Horse. And the scientists at the U.S. military’s Honolulu laboratory ultimately admitted that they couldn’t say with “100 percent certainty” that the bone fragments were “of human origin,” let alone perform a successful DNA analysis on them.

The diggers also found about two dozen V-rings from at least seven parachutes, but the Matejovs and their lawyers have pointed out that Col. Blau and other members of Joe Matejov’s 6994th Security Squadron have told them they almost always carried extra parachutes.

In a November 1992 survey at the crash site in advance of the excavation, U.S. officials found a dog tag belonging to Matejov on the ground. But crash experts said that meant little because the backenders often chose not to wear their tags, flying “sanitized” in case they were ever captured. Even if Matejov was wearing his dog tag that night, experts said, it could easily have fallen off when the plane turned upside down after impact.

Despite the lack of DNA evidence, the Air Force recommended that the bone fragments be buried in one coffin at Arlington National Cemetery in 1996.

A controversial tombstone erected in 1996 at Arlington National Cemetery, contains the names of all eight Baron 52 crew members. (Photo by Heather Moore Atherton)

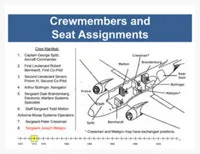

A large tombstone was erected with all eight names on it: Capt. George Spitz, aircraft commander; 1st Lt. Severo Primm III, co-pilot; 1st Robert Bernhardt, co-pilot; Capt. Arthur R. Bollinger, navigator; Sgt. Dale Brandenburg, electronic warfare systems specialist; Staff Sgt. Todd Melton, linguist; Sgt. Peter Cressman and Sgt. Joseph Matejov, airborne Morse systems operators.

As far as the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency was concerned, all of the men had now been “accounted for.”

Sen. Smith and some close relatives of the backenders strenuously objected to the collective funeral and burial, arguing that the controversy over Baron 52 was still very much alive.

John Matejov said his mom initially refused to attend the event. But her children convinced her to be there to honor the other families.

Over the objections of the Matejov family, the U.S. Air Force in 1996 held a collective funeral for the eight Baron 52 crew members. (Photo courtesy of Matejov family)

No Crater at Crash SiteFor years, the Matejovs had begged the Air Force to hold a hearing rather than a funeral. And the family got its wish in 2016 after John Matejov appealed to Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel in a letter during the Obama administration.

Four attorneys working pro bono and Ralph Wetterhahn, a famed plane crash investigator, showed up to present their case for changing Joe’s status from KIA to MIA. The Matejovs were told the two-hour hearing, attended by all of Joe’s siblings, couldn’t be recorded and that Wetterhahn couldn’t show a short video depicting how he believes Baron 52 landed in the jungle because the Pentagon didn’t have the right software to play it.

Wetterhahn had gotten involved in the Baron 52 case when John Matejov hired him about 15 years ago. After investigating the crash through documents and other records, Wetterhahn decided the case was so egregious that he offered to work for free.

A former fighter pilot in Vietnam, Wetterhahn says the Air Force was dead wrong to conclude that the plane had plummeted vertically and hit the ground nose first.

Scrutinizing photos taken from the air during the 1993 excavation, he said, it was obvious the plane came in horizontally on top of the triple-canopy jungle and skipped like a stone on water, flipping over and getting most of its wings sheared off before coming to rest about 400 yards from the point of initial impact.

If the plane had plunged vertically and hit the ground, it would have left a small crater and the plane’s nose would have been crushed. Neither happened, he said.

The cushioned landing would have allowed the backenders to survive the crash and take off on foot, he concluded.

Wetterhahn told The War Horse that declaring all the crew members KIA was a conclusion of convenience to wrap up the case quickly. “They all needed to be dead,” he said.

Mary Matejov Salzinger, a sister of Sgt. Joe Matejov, keeps mementos and photos of her brother’s military service in a drawer in the family room of her home in Portland, Oregon. (Photo by Mike Frankel of The War Horse)

Captured Alive, Died in Captivity?Just weeks before the 2016 hearing, attorney Tony Onorato had discovered new evidence through a sweeping document search that he and the Matejovs thought might swing the Air Force their way.

The documents, found at the Sam Johnson Vietnam Archive at Texas Tech University, suggested that the Defense Intelligence Agency still had “as yet unspecified information that some U.S. Air Force personnel lost in February 1973 had been captured alive and had died in captivity.”

The documents were written by Sedgwick Tourison, a former Defense Department intelligence officer who in the ’90s had exposed a headline-grabbing scandal about hundreds of South Vietnamese soldiers who were sent to North Vietnam on spy missions for the U.S. in the early 1960s, only to be abandoned for decades in enemy prison camps.

Tourison discovered that in February 1974 the Defense Intelligence Agency was maintaining a separate MIA accounting system from the Pentagon and had listed the status of the Baron 52 backenders as KK, the code for “died in captivity.” The Pentagon listed Matejov and the other Baron 52 backenders as BB, the code for “killed in action—body not recovered.”

“There is no explanation…that some had been captured alive and then may have been killed, information totally inconsistent with the Air Force’s official version,” wrote Tourison, who did extensive research for the Senate committee.

See a slideshow the Matejovs’ attorneys presented to POW/MIA officials during a 2016 hearing.

Shields, the former top POW/MIA official at the Pentagon, told The War Horse he was aware of the separate accounting systems.

In fact, he said he encouraged DIA staffers that he relied on for intelligence relating to prisoners and MIAs “to follow for their own use their perceptions of an individual’s status even if it were contrary to the official, formal status.”

The new evidence, however, made no difference. Eight months after the hearing, John Matejov got a call from a three-star Air Force general saying the secretary of the Air Force had declined the family’s request to change his brother’s status from KIA to MIA.

All the family’s efforts “landed us right back at the starting line,” Matejov said. “It was the same experience for my mom and dad back in the 1970s.”

‘No Man Left Behind’Many of the key sources who could directly answer the numerous lingering questions surrounding the saga of Baron 52—including Humphreys, Tourison and Schofield—died in the past two decades. The War Horse reached out several times to the Pentagon public affairs office, asking if it could provide a media spokesperson for this story. But we received no response.

One of the major questions is why it took 20 years for the U.S. military to return to the crash site. Initially, the area was deemed too hostile to launch another search operation that would risk more American lives. But even after the Royal Lao government and the Pathet Lao signed a peace treaty and agreed to a ceasefire on Feb. 21, 1973, the U.S. failed to successfully negotiate with the new coalition government to return to the site to meticulously sift through the wreckage of Baron 52 and retrieve more of the crew’s remains.

Mary Matejov Salzinger holds a poster created by the National League of Families to call attention to “unaccounted for” service members from the Vietnam War. (Photo by Mike Frankel of The War Horse)

“To this very day, I am more than ever convinced that the government I had once believed in had literally abandoned Joe in a most egregious manner that totally contradicted the ethos of ‘no man left behind,’ ‘fullest possible accounting,’ and honor,” John Matejov said. “Our family finds itself aligned with so many other families who, I now know, share this very same shameful realization.”

Smith, the former senator, said he sympathized deeply with Matejov because he also felt the same frustrations as vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee—a panel that was created through legislation he wrote.

The Pentagon needs to come clean on the Baron 52 case, Smith said, arguing that it makes little sense to keep so much information classified for so long.

“Unfortunately, there are still dozens of cases like Baron 52,” Smith said.

“Fifty-two years later, we’re still screwing around with these families. Why do they have to pry everything out of the government? Why can’t they just give them all the information all at once? Let them read it, and let them make up their minds.”

Since 1973, the remains of more than 1,000 Americans who died in the Vietnam War have been identified and returned to their families so they can be buried with full military honors, according to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

Of the nearly 1,600 Americans still “unaccounted for” from the divisive war, hundreds of bodies are deemed to be “nonrecoverable.” And the agency says it only rarely determines that new leads on MIA cases are strong enough to bring a case back to active status.

This War Horse investigation was reported by Ken McLaughlin, edited by Mike Frankel, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Ken McLaughlin

Ken McLaughlinKen McLaughlin is a freelance writer based in Scotts Valley, California, who spent 35 years at the San Jose Mercury News, where he was a reporter, editorial writer and editor. He’s written extensively about politics, marine science, Vietnam, immigration, and race and demographics. He has a master’s in journalism from Stanford University and taught aspiring science writers for a decade at UC Santa Cruz.

This post was originally featured on THE WARHORSE website February 2, 2025. Here is the original article:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

February 22, 2025

RISKING IT ALL FOR AN ENEMY OFFICER

Do you think it was crazy to risk four crew members, two passengers and a perfectly good aircraft and fly into a HOT LZ in an attempt to save a wounded enemy’s life. This pilot did, and this is his story:

By Robert B. Robeson, LTC, USA (Retired)

“If a man hasn’t discovered something that he will die for, he isn’t fit to live.”–Martin Luther King Jr.

It was Sunday, March 7, 1970, at our 236th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance) headquarters at Red Beach in Da Nang, South Vietnam where my flight crew of four was on 24-hour standby duty. I’d recently been promoted to unit commander as a captain the previous month. Combat action had been quiet that morning in our area of operation and no medevac missions had yet been received.

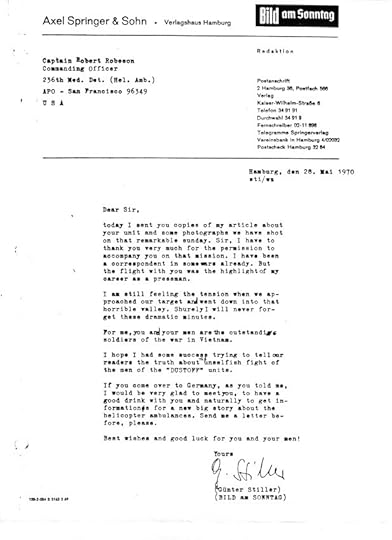

After returning from chapel service, a half-block away in The Viking compound, I’d had lunch and then returned to my hootch across from operations to get out of the blazing sun. At about 1:00 p.m., Gunter Stiller, a West German chief reporter for the Bild am Sonntag Berlin newspaper was driven up to our operations building by a U.S. Marine bodyguard in a Jeep, along with the newspaper’s German photographer.

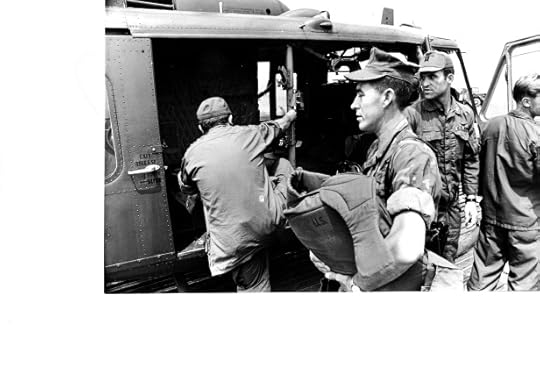

Bild am Sonntag Chief Reporter Gunter Stiller climbs into the “hell hole” on right side of the Huey’s jet engine, while his Marine bodyguard is directed to the left side “hell hole,” by Captain Robeson. Flight medic, SP5 Tom Franks, gets ready to close pilot’s door.

Stiller introduced himself and said he had permission and a recommendation from both U.S. and Vietnamese authorities to do a story on our unit because of the heavy action we’d been involved with in the past few months. He asked for permission to accompany us should a mission be called in during the following few hours. I told him that if we did receive one, his request to accompany us would depend on how many patients we’d have to evacuate, since three additional bodies might create a weight dilemma with a full load of fuel in high heat conditions. I also informed him that I had no problem if the three of them wanted to risk their lives along with us.

Then, in an effort to be frank and forthright, I mentioned that I’d had seven aircraft shot up by enemy fire and had been shot down twice in my first eight months in-country, which included around 850 medevac missions for over 2,200 patients. I emphasized that in our line of work, in a dangerous and bloody combat environment, our flight crews always had the opportunity to make a name for ourselves…postumously. Stiller, short and nearly bald, confirmed that he still wanted to fly with us and began interviewing me, taking notes and asking questions about our mission, unit personnel and how many patients we’d evacuated.

About a half-hour later, our operations specialist knocked on my hootch door to inform me that an infantry full-colonel wanted to talk to me on our landline phone. As Stiller listened to my side of the conversation, and his photographer was busy taking pictures, this colonel explained that an infantry company was in heavy contact with what was believed to be a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalion-sized force sixty kilometers northwest of Da Nang. He said these U.S. troops were surrounded in a remote V-shaped valley in dense jungle. During the fighting our soldiers had seriously wounded and captured an enemy officer.

“Captain,” the colonel said, “I’m told the landing zone (lz) is insecure and really tight, they’re taking a lot of small arms fire, but this guy isn’t going to make it unless you can get to him in a hurry. Having to guard him and deal with his wounds is compounding the problems our guys are having in continuing to fight in their outnumbered position. And you’ll probably need to take along a hoist because they say there may not be enough room to land.”

Since the safety of the lz couldn’t be guaranteed by our ground force, and the patient was an enemy soldier, we both understood (though it was left unstated) that no one could order me to fly the mission. As aircraft commander, it would be my call alone. If I agreed to go, I’d have to risk seven souls: our four crew members, three passengers, plus an expensive and critical aircraft. Although I’d always had a stubborn desire for living longer, I told the colonel we’d do our best to evacuate this officer.

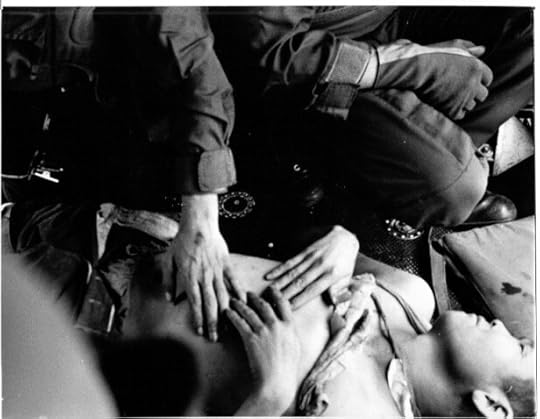

That’s when my biblical upbringing in the home of a Protestant minister caused me to reflect on what caring for others meant regarding his teaching and fatherly guidance as I grew up. My role in Vietnam combat was ultimately attempting to save as many lives as possible, even when it involved a wounded foe. The fact that North Vietnam had never signed the Geneva Convention Rules of War agreement, as the U.S. had, it was still my responsibility as a medevac pilot and unit commander to ensure any prisoner of war received humane treatment and medical care to the best of my ability. Other military branches, such as the Marines, Special Forces, infantry and artillery personnel, had different roles to fulfill that required them to seek, find and finish the enemy in a kill or be killed scenario. Our mission was supposedly to be as “noncombatants.”

We flew unarmed helicopters. If a landing zone was considered insecure we’d request gunship cover in an attempt to protect both us and our patients. Sometimes they weren’t available and we’d have to go in alone by ourselves. And often having gunships along wasn’t always enough to keep us from being shot up or shot down. Since the other side wasn’t bound by the same international warfare restrictions as we were, it was mostly open season on medevac aircraft and personnel. The large red crosses on our birds could often turn into major targets and aiming points if the enemy so chose…and they chose a lot. That’s why so many of our evacuation missions were reminiscent of the Wild West on steroids. Taking ground fire and confronting death in close combat on a daily basis, for our flight crews and patients, was as common as a pencil point breaking. Our unit personnel still acknowledged, among ourselves, that “grunts” on the ground had it the toughest of all due to how they were forced to live and endure “humping the boonies,” day after weary day, in every kind of weather, terrain and environmental circumstances imaginable.

As our crew and three potential passengers were driven, in a 3/4-ton truck, down to our flight line above the beach on the southern shore of Da Nang Harbor, I thought about our potential patient lying out in the jungle in a life-threatening situation. Although he undoubtedly had loved ones up north who cared whether he lived or died I had to admit, at that precise moment, that I felt he had less in common with me than almost anyone else in the world.

While the rest of my crew got the aircraft ready for flight, I directed our passengers to one side for a quick briefing.

“Listen,” I began, “I want you to be aware about what’s going on out there and that our troops on the ground are surrounded by a much larger ‘bad guy’ force. There’s always the possibility that we could be shot up or shot down. The colonel said this is supposed to be a jungle-covered V-shaped valley we’ll have to go down into that won’t give us much maneuvering room. If we run into trouble, and find ourselves down in that kind of terrain, there’ll be no idea of how long it might be before help arrives,” I added, emphatically. “And if we’re forced to use a hoist to get this guy out, we’re going to be exposed to whoever is out there while hovering 100-150 feet in the air for five or more minutes, like some dangling target in a shooting gallery. Just so you understand.”

That’s when Stiller’s photographer handed Gunter one of his cameras. Apparently risking his life along with us wasn’t any longer one of his main priorities after my truth session.

“Let’s go,” Stiller said, hanging the camera around his neck and heading for our aircraft. “Where do you want my Marine friend and I to sit?”

I told them they needed to take seats in the “hell holes” on each side of our UH-1H “Huey,” jet engine compartment. There wasn’t time to explain how these two canvas seats facing outward got their names. I’d already provided enough negative possibilities for them to contemplate.

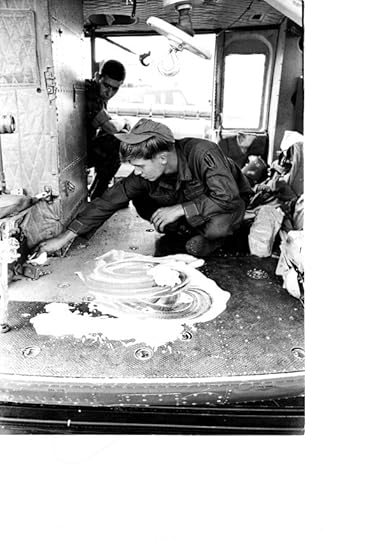

As we climbed to altitude over Hai Van Pass north of the harbor, I said my usual silent prayer for our safety, for the grunts on the ground…and even for my enemy counterpart. I didn’t want to risk our lives and aircraft for a dead man. If he lived, he’d be my responsibility until we could deposit him at the Special Forces Hospital in Da Nang. That was based on the premise we weren’t going to get ourselves “hosed-down” or blown away in the process.

Two “Black Cat,” AH-1G “Cobra,” helicopter gunships, that were stationed on the east side of Da Nang at Marble Mountain Airfield along China Beach and the South China Sea, caught up with us en route. Our operation specialist had called them to cover us. My copilot coordinated with them and the infantry radio-telephone operator (RTO) at the pickup site over our FM radio. When we finally arrived over the deep and steep V-shaped valley, I realized that both fighting forces had chosen a lousy location to get into a brawl.

When we were about thirty seconds out from their eight-digit ground coordinate, our gunships asked the ground troops to “pop” a series of colored smoke so they’d know where all of our “friendlies” were located and where not to direct their fire. I’d already asked them to make one low-level pass using their mini-guns and rockets to let the enemy know these escorts would be taking names and packing plenty of firepower if they decided to interrupt and engage our patient extraction in progress.

CW2 Sandy Letcher (now deceased) provides last minute information to Captain Robert Robeson before liftoff to evacuate captured and seriously wounded NVA officer. CW2 Tim Yost is in the process of starting the helicopter.

After this initial gunship run, and once they’d swung around up the valley to get ready to lead us in, Tim asked the RTO to pop another smoke exactly where our patient was located and where they wanted us to land. It would also show us which way the wind was blowing. I’d been circling above the valley rim waiting for this final approach moment to begin.