John Podlaski's Blog, page 8

June 15, 2024

OPERATION WANDERING SOUL

Named “Operation Wandering Soul”, the plan was simple: undercut the morale of an enemy you cannot see, so they cease to be an effective fighting force without the need for direct engagement. In this way, the U.S. military hoped to defeat the enemy and force their surrender before a shot had even been fired. Read what this was all about.

By Jerry Glazer

A failed attempt to dupe a determined enemy. The Vietnam War produced many schemes besides the apparent use of military strength. The U.S. concocted several unknown, if not strange, tactics to influence the outcome of the conflict.

One lowered the admission standards of recruits to keep the flow of replacements. Another became the flagrant spraying of the toxic chemical Agent Orange. Both came with terrible consequences. Another incorporated the use of urine detectors to hunt down hidden North Vietnamese. The machine proved ineffective because the contraption usually pointed to U.S. service members in the field. Still, one more, and perhaps the most bizarre, embraced the use of loudspeakers to influence the enemy that ghosts of their dead comrades wanted them to change their allegiances.

To manifest Viet Cong and North Vietnamese defections, the Army Psychology Operations Battalion (PSYOP), with the help of the Navy, orchestrated a propaganda campaign labeled Operation Wondering Soul. The unit broadcast tapes of weird and scary sounds combined with ghostly voices imitating the North Vietnamese dead.

The Vietnamese held the belief the dead must rest in their home soil, or their souls would eternally wander in pain and suffering. They also believed the dead would appear again on the anniversary of their demise. The Vietnamese honored their dead by returning to the place of their eternal rest to contact their spirit. The premise of Operation Wandering Soul rested on the idea the North Vietnamese would fear the loud jungle broadcasts of ethereal sounds and voices of the wandering dead.

Army engineers developed recordings of eerie noises and spooky voices portraying slain Viet Cong and North Vietnamese soldiers. The U.S. went so far as to use actual South Vietnamese troops to record the speech for authenticity. The recordings, dubbed the Ghost Tapes, included Buddhist funeral music and the voices of crying young girls. “Come home, Daddy!” the voices pleaded. There were other recordings of men screaming warnings, “Go home and reunite with your loved ones or suffer the wrath of the dead.”

In Firebase Cunningham (photo courtesy Paul Mannix)

The tapes repeatedly broadcasted over loudspeakers during the night close to North Vietnamese combat positions. The tactic attempted to keep the enemy from restful sleep. “My body is gone. I am dead to my family,” the loudspeakers blared. “Tragic, how tragic! My friends, I have come back to let you know I am dead, and I am in hell! Friends, you are still alive; go home! Go home before it is too late!” It went on like this until daybreak.

The overall success of Operation Wandering Soul and the Ghost Tapes produced dismal results. First, the North Vietnamese knew the sounds and voices were recordings. Moreover, they revealed the location of the broadcasters upon which the enemy immediately directed an attack.

The U.S. failed to understand the North Vietnamese were fighting for self-determination from foreign domination. As Ho Chi Minh repeated more than once, they would fight until the last person could hold a weapon. It happened in a previous prisoner exchange where the North Vietnamese stripped the garments provided by the Americans and crossed into the hands of their compatriots naked rather than show any comfort. The action proved a point missed by the U.S. military.

As Ho Chi Minh said, “You can kill ten of us for every one of you, and in the end, you will tire of the loss first.” And indeed, as the U.S. pulled out after eleven years, had given everything and gained nothing, it proved Ho Chi Minh’s prophesy.

Operation Wandering Soul became a failed attempt to win a war against a fierce and determined enemy who would rather die than surrender. And yet, we must wonder if our politicians learned anything from the experience. American history proved they did not.

So, did it work? Ultimately, it is hard to say. But one of the recordings, somewhat prosaically dubbed “Ghost Tape Number 10,” survives to this day. Listening to it, you can see how unsettling it would be to hear these sounds if they appeared from nowhere in the deepest jungle.

JERRY GLAZER

JERRY GLAZERAs the leader of a Special Ops team, I learned the hard way that the Vietnam War was built on lies and deceit. We had as much to fear from the hardened American units as we did from the enemy.

I was one of the more fortunate ones who returned alive, but every soldier has been wounded. I was awarded 3 medals for bravery and meritorious service awards, but PTSD, regret, and guilt followed me home.

When I returned from Vietnam, I recounted these bizarre stories: the humor and absurdity of basic training and combat. My friends and family members were intrigued and in awe of its insanity. And it was then that I put my thoughts on paper, and my passion for writing had begun…… Watch for the upcoming launch of my book, Vietnam Uncensored: 365 Days in a Nightmare.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 8, 2024

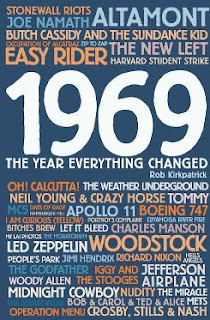

What I Missed in 1969

After fifty-five years, a Marine wrote an interesting poem during a writing workshop with a group of vets in Boulder, Colorado. The group was a mixed-gender/mixed-war (Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan) group. The group found the Vietnam Vet’s piece extraordinary, and Rachel Amaru sent it to me. Check this out!

When I think back to what I missed by spending the entire year of 1969 in Vietnam, it may not be what you think. Nothing back in the U.S. really existed for me. As far as I was concerned, nothing else concerned me other than what I saw in front of me. But later, I got curious.

In the early 1980s, I looked back to see what had happened and asked myself if the event meant anything to me.

In January, Richard Nixon became my Commander-in-Chief.

As for me, I didn’t care.

In February of that year, the Saturday Evening Post ended publication after over 140 years.

I didn’t care.

In March, I had my 20th birthday. We celebrated it by dodging nineteen 122mm rockets into our position.

I had already accepted my own death, so I didn’t care.

In April, Charles De Gaulle stepped down as the President of France.

At that point, I really didn’t care.

In May, John Lennon and Yoko Ono did their “Bed In” to protest the war.

Yes. You got it. I didn’t care.

In June, Judy Garland overdosed on drugs.

Nope. I didn’t care.

On July 20th, while taking a break outside of a small Vietnamese village, one of my guys turned on his handy dandy transistor radio to Armed Forces Radio, and we heard the announcer say that Neil Armstrong had just set his feet on the Moon.

I kind of cared.

In August, something happened in someplace called Woodstock, New York. I didn’t even know what had happened. About three years later, I decided to look up what had happened at Woodstock.

When I found out, I certainly didn’t care about that.

In September, I lost two of my good friends in a battle that we took part in on Que Son Mountain.

Nobody else cared, but I did.

In October, we got back to our home base. Twenty-six guys from our company didn’t make it back with us.

Hell, yes, I cared about that!

In November, I started thinking, “I just might survive this war.”

I finally started to care.

At the end of December, I boarded what we called a “Freedom Bird,” and we all applauded as the wheels left the ground. Then, we all became quiet and spent the rest of the journey in silence, trying to fathom what had happened over the last thirteen months.

We didn’t know how to care.

Fifty-five years later, in a small town in Colorado, I looked at my wife, my children, and my three grandchildren.

And I finally realized how much I care.

After all I missed way back then, I finally came to see how much I had gained. I have been taught how to care again. I learned how desperately I needed to feel compassion again and rediscover what true hope is. There was an old poem I remember reading some years ago. I don’t know the exact words, but it went something like this:

“Let me live in such a way, In some self-forgetful way,

Even when the world says ‘nay,’ I might live for others.

Though scarred, battered, and suffering filled my past.

May I live with love and hope, to humbly live for others.”

Steve Sisson, USMC

Vietnam 1968-1969

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 2, 2024

The French Foreign Legion, the Waffen SS, and Vietnam

Many believed that thousands of former Nazi Waffen SS soldiers joined the French Foreign Legion after World War II and fought against the Viet Minh at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. How did they escape being tried for war crimes? Was this France’s way of condemning them to death? Here are two different points of view. Did you know this?

By Georgy_K_Zhukov, December 11, 2012

Following the myths and legends about Nazis recruited by the French Foreign Legion to fight in Indochina, Eric Meyer’s new book is based on the real story of one such former Waffen-SS man who lived to tell the tale. The Legion recruited widely from soldiers left unemployed and homeless by the defeat of Germany in 1945. They offered a new identity and passport to men who could bring their fighting abilities to the jungles and rice paddies of what was to become Vietnam. These were ruthless, trained killers, brutalized by the war on the Eastern Front, their killing skills honed to a razor’s edge. They found their true home in Indochina, where they fought and became a byword for brutal military efficiency.

An estimated 35,000 Germans served during the eight-year conflict that ended 70 years ago when a disastrous defeat at the battle of Dien Bien Phu on May 7, 1954, brought about the fall of France‘s colonial empire in Indochina.

The French Foreign Legion was involved in the decisive battle of Dien Bien Phu in then French Indochina 70 years ago. The battle occurred in a remote valley in northeastern Vietnam and marked the end of French influence in Southeast Asia. The French garrison at Dien Bien Phu included legionnaires, Frenchmen, Algerians, Moroccans, enlisted Vietnamese, and other troops. The battle was a significant moment in the First Indochina War.

To start with, Germans have always made up an important component of the Foreign Legion – a popular saying is that the Legion is only as good as its worst German recruit – and in the wake of the World Wars, they were an especially high component, with recruitment happening straight from the POW camps. 50,000 German recruits actually sound about right for Indochina since roughly 150,000 Legionnaires served between 1945 and 1954, with a peak strength of 36,312, and while the anonymity makes exact figures hard to find, up to 60 percent is reported to have been Germanic (which would include Dutch, Austrians, and some Swiss/Belgians though) depending on the source! That’s a LOT of Germans, so 50,000 cycling through Indochina over nine years sounds feasible.

The origin of the idea that the FFL was rife with Nazi war criminals on the run, though, mostly comes from reports by the Vietminh after Dien Bien Phu, claiming that many of the German captives were Waffen-SS veterans. There are many reasons, however, why this ought to be treated with doubt and why almost every serious scholarship on the Legion these days rejects it, although more than a few picked it up and ran with it back in the ’50s and ’60s.

For starters, the Vietminh never substantiated their claims. It is quite possible they simply made it up, or perhaps they just assumed all Germans were Nazis on the run. Also, keep in mind the fact that the majority of their captives from Dien Bien Phu died over the next few months might have made them less than willing to document their claims and, in the process, demonstrate how terribly they were treating the POWs – during the conflict 26,000 French prisoners died in their care, 11,000 were released in August 1954.

There are other documented factors, though. In 1945-46, as the French recruited from POW and Displaced Person camps, they actually did screen candidates to some degree. German recruits especially were given enhanced scrutiny, but all recruits were required to strip and be inspected for the tell-tale blood-type tattoo that would have denoted membership in the Waffen-SS. Even having a scar in the spot where the tattoo might have been could be cause for rejection by the recruiter. This initial wave certainly would have had a fair number of Wehrmacht vets (enlisted only – officers were excluded), but only a small number of Waffen-SS who managed to sneak in somehow.

WWII Nazi Waffen SS unit tatoos

However, even members of the Wehrmacht would have made up only a small portion of the soldiers captured at Dien Bien Phu. While there would have been a larger proportion during the initial campaigning in Indochina, that first wave of recruits had finished their term of enlistment years before the disaster at Dien Bien Phu. The Legion was recruiting about 10,000 men a year, many of them certainly Germans, but by the 1950s, with the average age of a Legionnaire in the very early 20s, most German recruits were young men simply trying to escape the bleak situation in their home country, and the extent of their involvement with the Nazi party being their membership in the Hitler Youth as children.

So that’s the sum of it. The French recruited heavily in Germany, as they knew it was prime pickings for the Legion, but they explicitly excluded members of the Waffen-SS. It is certainly possible that there were non-SS war criminals who managed to sneak in and start a new life, but it was not with French knowledge, as they did their best to prevent it. As for how the Germans were accepted in the Legion… very well! As I said at the start, the Germans were viewed as the heart of the Legion, and more than a few officers were eager to see their return in great numbers in 1945.

*****

The following is reported by The Highlander eighteen years ago.

Because people are fascinated by the idea that former Waffen SS men

fought in the French Foreign Legion, I thought I would write out some

of the details to while away a sleepless night.

Many British people condemn the Irish Republic for remaining neutral

in WWII and I have no doubt that many Irish people had their own views about that, especially the large numbers of Irishmen who signed up under the British Colours and later returned home to be harrassed for “selling out”. Whether they were politically motivated, like the

Irishmen who fought in the Spanish Civil War, or people who could see

the likelihood of Ireland being invaded when Germany overran half a

dozen countries on the Continent and then turned their eyes towards

Britain, or whether they simply felt it might be an adventure and a

way to earn some money, the Irish volunteers formed an important part

of Europe’s resistance against the Nazis.

Not many people are aware that after World War II, large numbers of

Waffen SS soldiers joined the French Foreign Legion to go to

Vietnam and continue fighting the Ho Chi Minh and other Communist

terrorists that America had previously funded.

The SS, in particular, had been imbued by the Nazi leadership with the

the idea that Russian Communism was the greatest threat to Europe and their decision to join the Foreign Legion was often motivated by their belief that the Communists had to be fought on all fronts, including Vietnam. Their circumstances at that time, including avoiding the Nuremberg Trials and War Crimes Commissions, meant that they were looking for any opportunity to avoid being tried, jailed, and, in many cases, executed as war criminals.

Many opted to find their way to France, often on foot, to enlist in

the French Foreign Legion. The Legion was, no doubt, well aware of the

background of these droves of Germans who were willing to continue to fight and die, but it also desperately needed the experience and

expertise of these war-hardened veterans of countless battles. Not

even their former adversaries could deny that the Waffen SS was perhaps the most efficient, fanatical, well-trained and well-lead

fighting force ever created.

One cannot blame the French for this decision, as France urgently needed help. During WWII, Ho Chi Minh helped fight the Japanese in Indochina to secure independence for Tonkin as the colony of Vietnam was then called from France. (The U.S. actually provided arms, advisors, and even commandos to the Communist terrorist to help him achieve his goal.) However, France announced that French troops would return to take back control of Tonkin once the Germans had surrendered in Europe and an the incredible episode at that time saw the British, who, once they realized that the Americans were filled with Republican zeal in liberating and handing back many Asian countries to their original inhabitants actually moved into South Vietnam and released Japanese prisoners of war to help them suppress a growing Vietnamese movement to get the British out before the French arrived, much to American rage. The Americans bitterly said that SEAC (South East Asia Command) actually stood for “Save England’s Asian Colonies” and refused to offer more than minimal support.

However, the Americans themselves were not above taking back a slice of the pie (The Philippines), and they did their best to secure Hong Kong before the British could return to make it an American Protectorate.

With its unique window on China and deepwater naval facilities, Hong Kong was the plum of windows into Communist China. The Americans were foiled by the fact that Hong Kong’s Governor-General and his staff had survived Japanese captivity, and when they arrived, they found the British flag flying over Government House and the staff busily getting the island back to normal. End of America’s attempted Hong Kong grab.

The importance of Hong Kong can be seen in the fact that when the

Americans got more deeply into Vietnam, they pressured the British to join them. The British refused, pointing to Vietnam’s incredible history of driving out invaders, but did offer their spying facilities in Hong Kong, which the Americans found to be invaluable. The favor was returned during the Falklands War, when the Americans supplied

British planners with data from overflying satellites above the region, allowing the British to trump most of the moves made by Argentina; again, a little-known fact.

In fact, the Australians did decide that prosecuting the war was vital

to Australia’s defense interests, having had a bad shock during WWII

when the Japanese seemed to be on the verge of invading northern

Australia.

Also, again, a little-known fact, some of Britain’s SAS fought in

Vietnam, along with US special forces, used Australian uniforms as

cover to get mainland Asia experience in jungle fighting.

They apparently proved invaluable to the Americans as they were

already experienced in jungle fighting following Indonesia’s attempts

to grab (then British) Borneo after the Dutch were forced to leave

Indonesia, previously known as Java.

It was seeing the SAS in action that later prompted the Americans to

create their Delta force, which is modeled on the SAS and which

frequently trains and sometimes fights (Tora Bora, Afghanistan)

alongside them, as the Falklands proved that special forces can

achieve much better results than regular troops who lack their

unique skills.

Returning to the SS, we should also remind ourselves that a defeated

enemy can be extremely useful in victory, no matter how evil they may seem. For example, there was a terrific row in the US when the

American public found out that most of the Gestapo were now working

for the Americans, as were some of the various former Nazi police

forces. The reason? They knew where all the bodies were buried, who the good guys were, and who the bad guys were. The same mindset was at work when Churchill’s orders to store the Wehrmachts’ weapons close to the prison camps, in case the Wehrmacht was needed to help the Allies stop the Russians from advancing through Germany to the Atlantic coast in an attempt to take over Europe.

So, the French decision to hire the Waffen SS was not nearly as

unbelievable as one might think. Especially as most were rabidly

anti-Communist and welcomed the chance to get back into the fight

instead of going to jail and possibly execution.

Rallying his countrymen, Ho Chi Minh began attacking French garrisons

and committing atrocities that provoked the French to bombard

Haiphong. The Foreign Legion was expected to shoulder the burden in

Vietnam, as De Gaulle needed regular French troops to return home to

prevent a Communist revolution in his own country.

This allowed the SS volunteers to continue fighting the same

enemy in a different uniform. German (and, it should be noted, many other nationalities who were members of the Waffen SS) paratroopers and Partisan Jaeger (guerilla hunters) all flocked to fight the enemy once again.

While the jungle was a long way from the Eastern Front, the Soviet

cell structure, guerilla strategy, and overall operating methods were

followed by the Viet Minh (as the Viet Cong was then called), and the

Germans had long since learned the most effective means of dealing

with this type of warfare.

They ruthlessly matched the terrorists “bomb for bomb, bullet for

bullet, and murder for murder.” Just as in WWII, the SS let the

partisans know in advance; “for every one of us killed, we kill ten of

yours!” It was brutal, it was ruthless, but it worked.

When a convoy absolutely had to get through, when a French fort was

being besieged when a target deep in Viet Minh territory needed to be

neutralized, it was the SS that was called upon time after time. In

units of up to 300, they were armed, given orders, and sent on suicide

missions, although they often returned with few, if any, casualties of

their own.

They took death to the Viet Minh freedom fighters and beat them at

their own game. After passing through seemingly peaceful villages of

rice pickers, a few men with light machine guns would drop into

ditches along the side of the road to await the villagers’ reaction after the troops had passed out of sight. If they continued picking rice, they would be left alone. If they immediately began scurrying around, sending messengers into the jungle to alert nearby guerillas, or

attempted to follow the Legionnaires, hoping to shoot a few in the

back, they were instantly mowed down.

Another trick was to lie in ambush along a heavily used enemy trail

waiting for a small group of Viet Minh to come jogging past. As they

traveled spaced apart in a single file line, a skilled sniper with a

silencer-equipped rifle could take out the whole group by starting

with the one last in line and moving up, the ones in front never

hearing those behind hit the ground.

Sometimes, the Viet Minh would try to hit and run, escaping afterward

by lying on their backs submerged in shallow rice paddy canals,

breathing through reeds. A few grenades tossed in the water put an end to that.

Knowing that the terrorists usually operated within a 20-50 mile

radius of their own village, effective use could be made of the

civilian population to curtail attacks. For example, when traveling

through a dangerous sector, the wives and children of known local

guerilla leaders would be taken hostage and held at gunpoint until the

next village was reached, where a new batch of hostages was taken.

Once, the Viet Minh threatened to kill one French hostage every ten

minutes until a particular fort surrendered. After half a dozen

soldiers had been mutilated and murdered in plain view of the fort,

the SS showed up.

They had rounded up the families of some of the Communists known to be taking part in the siege and frog-marched them to the fort,

threatening to retaliate in kind. The fort was freed.

On another occasion, some terrorists were captured who knew the

location of French P.O.W.s but refused to talk. Knowing that time was

of the essence, the SS stripped the first prisoner and wrapped a cord of

slow-burning fuse around the man’s feet and legs, ending at his

testicles, where a detonator was attached. The fuse burned an inch-wide path up the terrorist’s body and blew his testicles off.

After seeing this, the second man to be stripped told the Legionnaires

what they needed to know, reputedly in three different languages, to

ensure they understood. The P.O.W.s were freed.

The Viet Minh were being fought with the same tactics they used and

they did not like it. The SS was able to blow up bridges and destroy

countless tons of food and other war materiel, eliminating thousands of

troops and sow fear and confusion behind enemy lines as they traveled

at will. The Germans were so successful that the Viet Minh began to

avoid them at all costs, and actually printed “Wanted” posters of some

of the SS commandos, offering up to 200,000 piasters for their

capture.

As in Russia, the Germans in Viet Nam were always outnumbered,

sometimes 20 or 30 to 1, but they always succeeded in out-marching,

out-fighting and out-terrorizing the Vietnamese. With a few more

divisions or a little more time, the SS was well on their way to ending

Communism in Tonkin in the 1950’s.

However, the election of a socialist Prime Minister of France, Léon

Blum, who vowed to rid the French Foreign Legion of the SS and did so,

Many were held back by the French High Command, who knew they had a good thing going with the former Waffen SS and were loath to kiss them goodbye.

Eventually, because the French General Henri Navarre refused to

believe that little men on bicycles could drag heavy artillery up high

mountains to overlook a small village in northern Vietnam called Dien

Bien Phu; he decided to make Dien Bien Phu the center of a fresh

attempt to drive the Communists into nearby Laos without drawing up

any strategic plan to achieve this laudable aim.

A cavalryman, Colonel Christian de Castries, was put in command and

correctly anticipating a defensive struggle as the village lies on the

floor of a deep valley, now overlooked by hills hiding Viet Minh

artillery, the little men on bicycles having proved General Navarre

wrong; dug in for self-defense as he could see that the defeat of the

French was inevitable, and the village was the ideal spot for a

massacre of the French, which would effectively end the war.

The French had committed 10,800 troops, with more reinforcements

totaling nearly 16,000 men to the defense of a monsoon-affected

valley surrounded by heavily wooded hills that had not been secured.

Artillery, as well as ten M-24 light tanks and numerous aircraft, were

committed to the garrison as well. The garrison comprised French

regular troops (notably elite paratroop units plus artillery), Foreign

Legionnaires, Algerian and Moroccan tirailleurs, and locally recruited

Indochinese infantry.

The Viet Minh moved 50,000 regular troops into the hills surrounding

the valley, totaling five divisions, including the 351st Heavy Division,

made up entirely of heavy artillery. Artillery and AA guns, which

outnumbered the French artillery by about four to one, were moved into camouflaged positions overlooking the valley, and the French came under sporadic Viet Minh artillery fire for the first time on January 31, 1954, and patrols encountered the Viet Minh in all directions. The

battle had been joined, and the French were now surrounded.

After a battle lasting 209 days, during the last 54 days of which the

garrison was actually under constant attack, overseen by one of the

greatest generals the world has ever seen, General Giap, all French

resistance collapsed.

On May 8, the Viet Minh counted 11,721 prisoners, of whom 4,436 were

wounded. This was the greatest number the Viet Minh had ever captured: one-third of the total captured during the entire war. The prisoners were divided into groups. Able-bodied soldiers were force-marched over 250 miles to prison camps to the north and east. Hundreds died of disease on the way. The wounded, counted at 4,436, were given basic triage until the Red Cross arrived, removing 838 and giving better aid to the remainder. The remainder was sent into detention.

The prison camp was even worse. The survivors of the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu, many of them SS Legionnaires, were constantly starved, beaten, and heaped with abuse, and many died. Of the remaining 10,863 prisoners, only 3,290 were repatriated four months later. The Viet Minh made tremendous political capital out of the number of SS men found fighting for the French, and sympathy for the French in the rest of Europe and elsewhere sank to nil.

When the French pulled out, American advisors moved in, and soon after did the first US troops. We know the rest but for the French, the

news that the famous Foreign Legion had been defeated led directly to

the African colonies of Tunisia and Morocco gained independence by

1956, while in the “Jewel in the French Crown,” Algeria’s War of

Independence started six months later, resulting in independence on

July 5, 1962.

I know this has been a long and exhausting read and that I have

glossed over many of the details, but I thought it would give you all

some insights into why our world is as it is today.

Without the SS, Vietnam would have been lost much earlier, and

although the Americans were underwriting the French at the time of

Dien Bien Phu by as much as 80% of their costs and supplying support

help, including bombing runs against the Viet Minh, the chances are

that the American effort in Vietnam would not have gone much further

than helping the French evacuate. But, thanks to the SS and the Legion

keeping the war alive; by the time it did end, the Americans were so

obsessed with the idea that losing Vietnam meant opening up all of

Asia to a Communist takeover, that it took over the war and, like the

French lost it.

Vietnam, called An Nam (southern province) by the Chinese, fought a

500-year war against China to become free. When the French took over, it was the last Asian country still governed by the principles of

the great Chinese philosopher Kong Fu Tze, whom we call Confucius. The language is complicated, using eleven tones in contrast to Mandarin’s four tones.

The people are small and slight but well made, with women that many

think are the most beautiful in Asia and men who do not understand the meaning of ‘defeat.’ They created a new world standard for

toughness and cleverness by first defeating China, then France, and

finally, the greatest power the world has ever seen, the United States.

As citizens of small countries, Ireland and Scotland, beset so often

by enemies throughout history, one has to admire the Vietnamese.

I compiled this from several sources, so any errors and omissions are

mine.

So there you have it. What say you?

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

May 25, 2024

ATTACK ON LZ GRANT

LZ Grant was an isolated outpost of the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division, acting as a tactical control point and logistical supply area for the maneuver elements of the 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry. Located one kilometer from the Cambodian border in Tay Ninh Province, RVN, it was near a trail down which the North Vietnamese Army funneled supplies and personnel to fight in South Vietnam.

Nui Ba Den is the famous mountain in Tay Ninh province (III Corps), and is seen for miles around. The Americans had a base on top which was later overrun during a battle of their own.

At 03:30 on 23 February 1969, a force from the VC 1st Battalion, 95th Regiment attacked Grant. The attack was repulsed, with the VC losing sixteen killed and two captured.

Then, at half past midnight on March 8, 1969, the North Vietnamese Army struck LZ Grant, announcing the battle when a 122mm rocket with a delay fuse arched across the sky and slammed into the sandbagged command bunker. The big projectile sliced through three layers of sandbags and detonated inside. The battalion operations officer was outside the bunker checking on the readiness of the base defense when the rocket hit. He raced back and found it demolished. Looking through the smoke and dust, he could see LTC Peter L. Gorvad dead in his chair at the map board.

Five Americans from D Company, 2nd Battalion, 12th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, comprised a listening post on the east side of the LZ beyond the second or third row of wire. Situated in a large depression in the ground, ten to twelve feet in diameter, they held their position when the onslaught began. Just before daylight, they decided to try to make it back to the LZ. They got halfway back when they ran into NVA soldiers. Outnumbered, PFC Charles D. Snyder and PFC Larry E. Evans were hit with very heavy fire and killed. The other three made a mad dash to the LZ, running in a crouched position, and made it.

At the entrance of the LZ, enemy Bangalore torpedoes blew a hole in the gate as B-40 rockets screamed in from hidden spots, and mortar fire rained down on the landing zone. The NVA launched a human wave assault, sending masses of soldiers through the ruptured gate. Another D Company member, 1LT Grant H. Henjyoji, leaped out of his bunker with an M16 rifle to confront the enemy. He was killed almost immediately.

The rifle company that defended the camp fought so well that most of the Claymore mines ringing the camp were not needed or fired. Air strikes and Spooky gunships peppered the NVA as they charged, and the camp’s defenders lowered their artillery pieces and fired point-blank into the on-rushing enemy.

At least six enemy soldiers made it through two rings of concertina barbwire to die less than thirty feet from the guns of the Cavalry troopers. None made it through the final defense. At 6:15 AM, the enemy withdrew. U.S. losses were fourteen killed in action and thirty-one others wounded. PAVN losses were 157 killed, two captured, and twenty-three individual and ten crew-served weapons captured.

LZ Grant in 1970

The lost Americans included Gorvad, Snyder, Evans, and Henjyoji; also CPT John P. Emrath, 1LT Peter L. Tripp, CPT William R. Black, SGT Walter B. Hoxworth, CPL Vincent F. Guerrero, SP4 John R. Hornsby, SP4 Thomas J. Roach, PFC Glenn R. Stair, Akron, PFC Roy D. Wimmer, and SP4 Gordon C. Murray.

Two days later, at 01:45 on 11 March, a PAVN/VC force assaulted Grant again, supported by mortar and rocket fire, before breaking contact at 03:30. The 2/12th Cavalry lost fifteen killed, while the enemy forces sustained sixty-two killed and two captured.

Click on the link below to read the actual “After Action Report,” which goes into extensive detail:

https://cipher100.net/NonImagePDF/LZGrant.pdf

[Taken from coffeltdatabase.org, virtualwall.org, and “GIs Hurl Back Charge by N. Viet Battalion.” Pacific Stars & Stripes, March 10, 1969; “Gentle Warrior.” The Oregonian, May 28, 2000; and information provided by Bob Jones at 12thcav.us]

Here’s a short eleven-minute video showing those bases overrun by enemy soldiers during the long war. Most were unknown to this website administrator, but I am familiar with the later attacks. Nevertheless, those who fought there will never forget.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

May 18, 2024

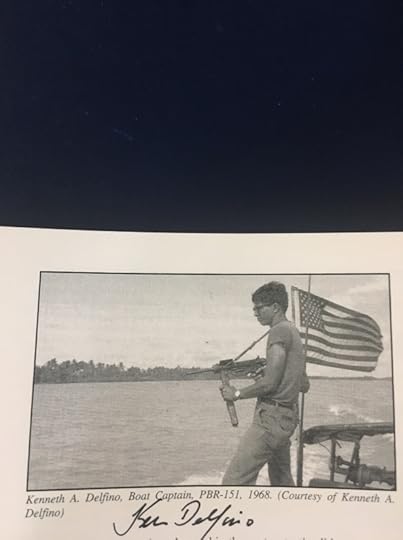

As If It Were Yesterday!

On the outbreak of the Tet Offensive, one Navy Boat Captain recalls those events that transpired during the first two days in a Saigon suburb. Read his story here:

By Ken Delfino

WHUMP! WHUMP! WHUMP! The sound of distant explosions interrupted the reverie of my dreams…BLANG! Boy, that one was closer! WHUMP! BOOOM!!!

“Delfino, wake up! Delfino, get the hell up!”

Who is this yelling at me I wondered as I groggily tried to wake… it’s just another mortar attack and…WHUMP! BOOM! BOOM! B-r-a-a-a-a-a-k! B-r-a-a-a-a-k! The staccato of semi and fully-automatic weapon fire shook the cobwebs out of my brain as I realized this was not our normal monthly visit by “Five-Round Charlie.”

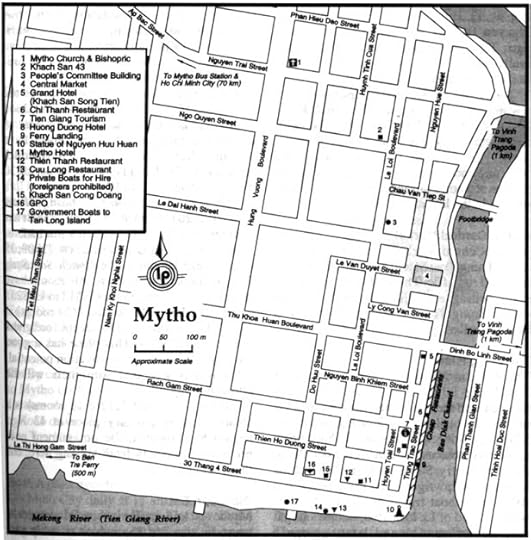

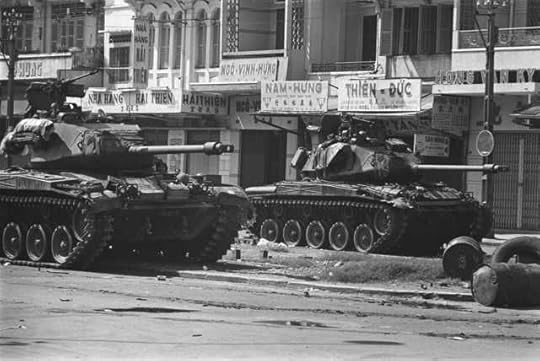

It was around 0430 on January 31, 1968, in My Tho (me taw), the capital of Dinh Tuong Province, about 45 miles south of Saigon. My Tho was the headquarters of the United States Navy’s River Squadron 53, comprised of patrol boats (PBRs) of River Divisions 531, 532, and 533 and a SEAL team. It also served as headquarters for the Vietnamese Army’s 32nd Ranger Battalion and 7th Army Division.

Two of the three river patrol divisions were stationed in the town and rotated with the third off an LST (WWII Landing Ship, Tank) at the mouth of the Ham Luong or Co Chien Rivers. I was a crewmember of PBR 152, River Division 533, and we were on our “in-town” rotation this month. Each crew of four was housed in a room in a requisitioned hotel renamed Carter Billet, and we were a block east of some of the 7th ARVN HDQ buildings. Around the corner and across the street on Avenue Le Loi was the Khach-San Victory (Victory Hotel) Our squadron headquarters and officer country were housed there. From there, it was eight blocks south on Le Loi to the piers where our boats were. When mortars started falling, the ‘off-duty’ crews scrambled to the docks to disperse the boats until the attack ended.

On the evening of January 30, some fellow sailors and I visited the Philippine Civic Action Group (PHILCAG) villa. This was a medical detachment assigned to the province hospital in My Tho. I had met them earlier in the year, and we had received occasional invitations to come over for some ‘home-cooking’ of tasty Filipino dishes…and hard-to-come-by San Miguel beer!

When mortar attacks began, the Filipinos had their own procedures: the “duty half” of the team got dressed and rushed down to the hospital to await civilian casualties. Their villa was about half a mile from our headquarters at an intersection we called “The Y.” It was the entrance to My Tho on the main highway from Saigon.

With January 30 being the evening of the Lunar (Tet) New Year in South Vietnam, there were several Vietnamese among the guests that evening. The party continued until several of us were reminded we had patrols and other assignments the following day. We wished each other “Cung chuc may man” (Happy New Year) and returned to our bases. I had several San Miguel beers and had forgotten that since I had cut back on my drinking while in-country, it didn’t take as many to put me under!

As my boat captain, BM1 Jim Hicken, and fellow crewmates tried to raise me from the stupor, they gave up and placed the other three mattresses against my bunk between the street and me. Then, they took off to get 152 underway.

WHUMP! WHUMP!…. ah, it’ll stop, I thought…. KABAAAAM!!!!!!… The building shook…crap was flying all over the place. That, along with the close sounds of automatic weapons, immediately woke me! I dressed quickly; flak jacket…helmet, or beret??? I chose my black beret for quicker recognition by our guys, grabbed my M-14 and extra magazines, and bolted outside. It was still dark…I yelled up at the sentry on the roof of our building to call over to the Victory to let him know I was coming. There was no response…it wasn’t until later that day that I heard that the water tank on top of our building had taken a direct hit, and the sentry was not up there.

GMG2 Glen “Slayer” Slay’s recollection of that morning was the water cascading down in front of his glassless window and chunks of debris. He saw what was happening and found a very shaken sentry. He grabbed his gear and went to the docks to get his boat underway. They cleared the docks just as a mortar hit the dock itself!

I ran to the corner of our alley and Le Loi and took two steps into the street before I heard the unmistakable sound of a .50 caliber machine gun being loaded! I ducked back and yelled, “Delfino, coming over!”…the response was, “Who won the Series?” to which I responded, “St. Louis!” and I was cleared to cross the street and enter the Victory grounds. I went to the galley, got a cup of coffee, filled my pockets with chow, and tried to find out what was happening.

The TOC was a beehive of activity as report after report came in about attacks on all province capitals, Saigon, nearby towns of Ben Tre, and another squadron base at Vinh Long. After looking at the markings of activity on the map around the city, the first thing I needed to get was more ammo! We had a shuttle that went between the TOC and the base, and after finding the driver, I jumped in, and we took off.

While passing the second intersection, we took fire from the west, and I wondered if it was nervous Viets or VC? It was still too dark to tell foes from nervous friendlies. We made it to the base, and I stocked up on more ammo and wondered what I would do. All the boats had been deployed, and extra base personnel jumped at the opportunity to fill in a spot…as someone had filled mine on 152.

The driver was GMG3 Jose Garza, another 533 guy ordered to serve as the shuttle driver until relieved. Our adrenaline was pumping, and here we were, two sailors who were like ducks out of water! A call came in for the shuttle, and Jose had to return. I told him to wait and went back into the armory. I knew there was an M-3 “Burp Gun,” and if I was going to be Jose’s shotgun driver, I wanted a weapon that was easy to use in a vehicle and had knockdown power. I grabbed the M-3 and the five magazines. I also grabbed a blooker (an M-79 grenade launcher) and a belt of 25 grenades…just in case.

We returned to the hotel to pick up the passengers, and the city was lit by dawn. The gunfire was very heavy and too close for comfort. We knew the ARVN had set up a tank perimeter but did not know how far from the base. I stayed with Jose, and at around 1000 hrs., I asked him to go to the hospital to check on the PHILCAG team.

We arrived, and I spotted MAJ Manason, the senior officer. I asked how the team was doing, and he told me that the off-duty team was trapped in their quarters! Jose and I returned to the TOC and found CDR Sam Steed, the squadron commander and ranking officer. He had been to the villa several times, and when I told him I wanted to get some volunteers to get the team out, he said, “DO IT WITH WHATEVER YOU NEED!.” With his support, we returned to the base to round up a couple more guys. Two sailors were available, fellow 533 sailor GMG2 Rich Wies and base armorer GMG3 Dennis Keefe. “I have a mission, and we need some support,” I started. Halfway through my explanation, Rich and Dennis turned around, picked out the weapons they wanted, and stuffed their pockets with ammo…Dennis took an M-16, and Rich picked a Winchester Pump. We piled into the shuttle truck and headed back up Le Loi. Just past Carter Billet, we turned left and headed two blocks.

Later, we were in front of a large school that no longer had a roof and whose façade was pockmarked with bullet holes punctuated by black-rimmed holes from cannon fire. At the end of the street, we had to make a right and go two blocks to the team’s quarters.

The ARVN tanks were parked, engines running, and I asked for the senior ARVN officer. I told him in Vietnamese about the Filipino medical team and asked him to move his tanks to give us cover fire if we got in trouble. “NO, I CAN’T!” He did not want to jeopardize his tanks for an impromptu mission! We were on our own!

Wanting a quick egress, Jose turned the truck around and backed it down the street toward the “Y” as Keefe, Wies, and I hugged the buildings. Bodies and debris were everywhere… on the roads, sidewalks, and blasted buildings. We passed the first block and hoped the ARVN officer had let the other roadblock know we would be crossing. We took no fire from the street.

We proceed…one more block to the “Y” and the villa. Wies was on point, and Keefe covered the intersection ahead of time. We reached the walls of the villa compound, and I immediately went for the bomb shelter only to find it full of Vietnamese civilians!!! Had the team gotten out? The door was closed, so maybe they were still inside.

I tapped on the front window rather than take a chance that rounds would be fired through the door if I knocked on the front door. I tapped and yelled, “Myrna! Myrna!” trying to get a response from LT. Myrna Milan. Three shots rang out. I ducked and turned to see Wies’ shotgun barrel smoking…it was aimed at upstairs windows across the street…” Just keeping ’em honest and their heads down!” he yelled.

“I got you covered”…I banged on the window again, yelled Myrna’s name much louder, and saw the curtain move and her face appear in the window.

“Let’s go! We’re getting you guys out of here now!” She disappeared, and in less than a minute, the front door opened, and she, CAPT Leonora Gumayagay, and a sergeant appeared. We escorted them around the corner, loaded them into the truck, and took off for the hospital.

When we arrived, they were aghast to find that another sergeant was missing! He had gone back upstairs to destroy the radio so it couldn’t be used in a counterattack, so we had to go back to get him!

Garza, Keefe, Wies, and I looked at each other…nothing was said, and we all piled back into the truck and headed back. Once again, the ARVN officer would not move a tank, but this time, he did have a fire team cover us to the next intersection…but not all the way to the” Y.”

On this trip, I took a closer look at some of the VC bodies and noticed a couple that were much larger and did not have the harsher VC features…I deducted they may have been Chinese. They were all wearing black and had blue armbands. The stench of burning flesh was overpowering and something one doesn’t forget.

My memory’s a bit fuzzy here, but SGT Salvador was the commo man, and he was very relieved and grateful that we came back to get him. We got him out and back to the hospital. We were happy that not one of the team members was lost.

After grabbing some chow and water, we decided we needed another vehicle to patrol the inner perimeter in two vehicles. We found a blue jeep with USAID markings sitting unattended. Someone hot-wired it, and it returned to the base, where a coat of OD green was applied, and a mount for an M-60 was added. Navy markings were added, and we were set.

Around 1500, we were in the vicinity of the soccer field, which was across the street from the previously mentioned school. Adjacent to the field were two Army jeeps with one US WIA. They were waiting for a DUST-OFF to come and pick him up. There was a helo pad on the west side of town, but units of the 9th Infantry Division had not yet cleared out the VC that had taken over that area.

We decided to take a break and wait to see the Medevac. As the helo was flaring out to land, the window in the announcer’s booth across the field suddenly flung open. Not knowing if a VC was in there with a B-40 rocket, we immediately took the booth under fire…the army sergeant waved off the chopper, and they took off.

We escorted the soldiers down to the docks and called in a PBR to take him to the Army hospital at Dong Tam, just five miles east of us. VC still had the road cut off to Dong Tam.

I returned to the TOC and gave CDR Steed and my XO, LT Bob Moir an update on the Filipinos. After hearing the report, CDR Steed told me to invite them to stay at the TOC so they’d at least have some military protection instead of the hospital where there was none. Officers doubled up in their quarters and bunked in rooms whose crews were on patrol.

It wasn’t until around 1600 that I returned to my room and noticed a massive hole in the street in front of the Carter. This round had hit and jarred me out of my stupor. We had a deuce-and-a-half stake truck parked across the street, and the entire side was shrapnel…as well as the wall protecting the first floor…MY FLOOR of the billet!

As darkness started to fall, we learned more about what had happened. It was a guess that up to three battalions of Viet Cong had hit the town (later determined to be accurate). Still, it was repulsed by an immediate counterattack by the 7th ARVN on the north and west, the 32nd Rangers on the east, and our SEAL team wandering through town doing what they had to do to help stem the attack. The 9th Infantry counterattacked from the west toward the ARVN positions, but that five-mile area was to be contested for a few more days. The immediate threat to the city’s heart (7th ARVN HDQ and our TOC) had been stopped. Still, we all were anticipating a counterattack when darkness fell. The daylight revealed several buildings with holes in their roofs where mortars had hit.

After picking up the Filipinos and settling them at the TOC, we decided not to stay in the Carter. Instead, we picked a building across the street from the TOC that gave us a decent field of fire over the western approach to the TOC, which was a block away. We supplied ourselves with water, food, and plenty of ammo and grenades and settled in for the night.

Though night had fallen, the battle raged on. Twinkling lights in the sky indicated either helicopters or fixed-wing aircraft. Several times, green tracers of the enemy would reach for the lights only to receive a return of thousands of rounds from a Spooky gunship. Artillery rounds from Dong Tam landed only a few miles away as they supported operations in progress. Gunfire could be heard in the streets, but beyond the perimeters set up by the Vietnamese.

I started dozing off into that mode known as ‘combat sleep’. Your body is relaxed, but your mind can separate imminent from possible threats. You aren’t really asleep, but you can recharge.

When morning came, battles were still raging nearby, but the offense had been pushed beyond mortar range of us. A LOT of credit goes to SEAL Team 2 and the Vietnamese 32nd Ranger Battalion, whose immediate reactions helped protect the base and keep the VC away from our HDQ until the 7th ARVN was able to set up their perimeter.

Ken Delfino Crewmember PBR 152;

Boat Captain, PBR 151

River Division 533, RIVRON 5 TF-116 9/66-7/68

Epilogue

That morning…that day…that week will live with me forever. I’ve always wondered what happened to my Filipino friends and my “team”…those guys who did not hesitate to step forward. Since 2002, I have had the opportunity to meet up with Jose, Rich, and Dennis. A few years ago, with tremendous help from the former PHILCAG Chief of Staff, I received a letter verifying the mission from COL Myrna Milan Delena, Philippine Army (RET). Through her, I discovered that COL Leonora Gumayagay is in Las Vegas and COL Estela Casuga is in Daly City…where I went to elementary school and lived after returning from Viet Nam and until the late ‘70s. I spoke with Nora (we called her Mom), and I will attempt to contact Estela.

People have told me I should write a book, but I don’t know if I’d enjoy it — let alone have it sell! I greatly thank President Fidel Ramos, GEN Jose Magno, Jr., and Ms. Stella Marie J. Braganza, who helped me locate members of the Dinh Tuong team.

So this small segment of my life is dedicated to my brothers-in-arms with whom I patrolled the Long Tau, Soi Rap, Co Chien, My Tho, and Ham Luong Rivers for 22 months…to my young friends at Millbrook High School in Raleigh, NC (Kim, Sara, Kevin, Chris, Courtney, John, Caitlin, Lauren, Megan, Gessica, Nikki and Alicia) who have been able to pull forgotten memories out of the recesses of my mind…to Dr. Lindy Poling, who created the Lessons of Vietnam class at Millbrook…to Ralph Christopher, who told our MyTho story in his book “Duty…Honor…Sacrifice”…to Rich, Jose, Dennis (RIP), and the members of the Dinh Tuong PHILCAG Medical team for a bond that will never be broken…and to my wife Melba, who stood by my side and understood the frustration, anger, and need for revenge that raged through the core of my body and mind after the September 11, 2001 attacks by those Muslim extremist murderers.

This story was written for you…just as it was…. as if it were yesterday!

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

May 11, 2024

STUNNING COURAGE: A CAVALRY COMPANY’S FEROCIOUS BATTLE TO CLEAR NVA BUNKERS

The soldiers in Company D, like these troopers from another unit in the 1st Cavalry Division, were hit with a hailstorm of bullets and mounting casualties. (Robert Hodierne).

More than 20 platoons of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) waged a bitter fight against the NVA bunkers. The battle was largely forgotten except by those who survived. Read about it here:

After darkness fell on Dec. 17, 1966, the dead and wounded of Delta Company lay in an open area between North Vietnamese Army bunkers and hedgerows. In daylight, it had been a no man’s land where anyone who moved was shot. Pfc. Michael Noone was shot three times—once in the leg and twice in the torso. The bullets broke his ribs and knocked his stomach out of the body cavity. Giant red-and-black biting ants, dubbed “blood ants” by American soldiers, crawled over him, feasting. He used his one good arm to slowly pick them off and bite them in self-defense.

Under the light of flares, NVA soldiers crept out to execute the wounded and scavenge the dead. One approached Noone and peered over him. A flare went off, and the enemy soldier ducked until the light receded, then got up and looked Noone directly in the eyes. The American feigned death. The NVA scavenger put his rifle down and picked Noone up by the pistol belt. Unfamiliar with the hook attachment, the North Vietnamese soldier struggled to remove it. As he fiddled with the belt, the ants bit him, and he immediately dropped Noone to the ground. After searching for the American, he left him for dead. Noone was one of the lucky ones.

Seven hours earlier, at 1:38 p.m. Noone’s Company D, along with companies A and B of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Brigade (Airborne), 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), were told to prepare for helicopter pickups. The troopers were going into a valley north and west of Landing Zone Uplift, 8 miles south of Bong Son in Binh Dinh province in South Vietnam’s central coastlands. The area was called 506 Valley, named for the “highway” that ran through it.

The Dec. 17 battle in the valley involved all of 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment; two companies of 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment; a platoon of 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment; and elements of 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry Regiment, for a total of more than 20 1st Cav infantry platoons.

In number of U.S. casualties, the Battle of 506 Valley ranks among the top battles of the Vietnam War, yet rarely appears in histories of the war and is not well known except by those who survived. During the fight, 34 soldiers in the 1st Cavalry Division were killed and 81 wounded, according to the division historian’s report after the battle. More than half of those killed were assigned to Delta Company, which suffered 18 deaths, all but one in 2nd and 3rd platoons, the company’s highest one-day death toll of the entire war. Delta had 12 men wounded.

U.S. troops head for their helicopters, as did companies A,B,C and D of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, when ordered to helicopter pickup zones the afternoon of Dec. 17, 1966, after another unit of the 1st Cavalry Division ran into a large force of the North Vietnamese Army. (Bettman/Getty Images)

U.S. troops head for their helicopters, as did companies A,B,C and D of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, when ordered to helicopter pickup zones the afternoon of Dec. 17, 1966, after another unit of the 1st Cavalry Division ran into a large force of the North Vietnamese Army. (Bettman/Getty Images)Company D, initially the battalion’s combat support company (reconnaissance, mortars and weapons), had recently been reorganized into a line infantry company, although 1st Platoon continued to be used as the battalion’s recon unit. A six-man long-range reconnaissance patrol team from 1st Platoon was sent out two days before Dec. 17 to identify NVA activity in the valley.

Recon team member Spc.4 Larry Nolen was concealed in an observation position behind thick bamboo and elephant grass. Sweat dripped down his nose as he sat motionless and waited. Eighteen NVA soldiers, carrying mortar tubes and base plates, approached the recon team, which watched the NVA moving cautiously across the American front.

An NVA scout, walking parallel to the line of march, approached the team’s positions, checking for the possibility of ambush. He pushed the bamboo concealment back with the barrel of his AK-47 assault rifle and looked Nolen right in the eye from 3 feet away. Pretending not to see Nolen, the scout let the grass spring back into place. Nolen shot him dead. The team’s position was “blown.”

A running firefight ensued. “The NVA headed for the cover of a nearby tree line and the LRRP team ran down-slope towards a possible pickup zone near a small village,” recalled Spc. 4 Steven Chestnut, a member of Delta’s recon platoon, in an interview with this article’s author.

Before the team could reach the pickup zone, it was surrounded by the larger enemy force. One recon trooper was shot in the elbow. His bone fragments wounded team leader Sgt. Curtis Smith in the lower leg. The team was in trouble and needed help. Two heavily armed black CH-47 Chinook helicopters arrived at 1:15 p.m. and hosed down the NVA, driving the enemy out.

A few miles away, the opening act of the 506 Valley engagement was well underway. The first round of fighting began when Company C, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, was on a morning patrol using an XM-2/E63 personnel detector, a backpack-size sensor, and a tube that samples the air to detect ammonia concentrations, a characteristic of sweat and urine. The “people sniffer” led Company C to an estimated platoon-size NVA force in the hills above the 506 Valley, and a fight between the two forces began about 10:03 a.m.

The NVA fled down the hill toward a village, leaving behind equipment, including a radio switchboard, implying the presence of a much larger force. The 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry’s aerial scouts in H-13 Sioux scout helicopters were deployed to find the enemy. At 1:34 p.m., they reported the NVA forces were dug in around the village. The squadron’s ground platoon was then flown in on Hueys. The platoon immediately ran into a buzz saw of fire from AK-47 assault rifles and machine guns in NVA bunkers. Significant casualties forced the cavalrymen to pull back.

Lt. Col. George D. Eggers Jr., commanding 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, and responsible for operations in the area, realized the enemy force was much larger than estimated. At 1:38 p.m., he told the battalion operations officer, Maj. Leon D. Bieri, to order all 1st Battalion companies to the nearest helicopter pickup zone and prepare to join the fight. Companies A, C, and D were to attack from the north, and Company B would be inserted to the east to cut off an enemy escape. Elements of 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, and 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry, were already deployed from west to south.

Delta Company hurried to its pickup zone. On Dec 17, the company was commanded by its executive officer, 1st Lt. Chester Cox, an airborne Ranger acting for the commanding officer, Capt. Barnett, who was on leave. At 3:40 p.m., the 2nd Platoon, led by 1st Lt. Paul Prindle, and the 3rd Platoon, led by 2nd Lt. Timothy Feiner, helicoptered to a landing zone near Thach Long (2); the numeral indicated the village was the second one in the valley with the same name. Delta secured the landing zone for the battalion’s Company C, then moved southeast. Within 15 minutes, Delta made contact.

One of the Delta Company men in the fight was Spc. 4 Jack Deaton, a married, 22-year-old airborne volunteer who arrived in Vietnam on Sept. 1, 1966. Shortly before the 506 battle, Deaton confided to Spc. 4 Michael Anderson, the platoon medic, and other platoon members that he had received a letter from a close relative expressing the wish that he would be killed in Vietnam. He did not elaborate.

Deaton was upset, and his buddies were concerned about him. Caustic letters were common, but for someone to wish death to a combat infantryman was extreme. Deaton’s buddies wondered: “Had someone in Deaton’s life become a hard-core anti-war activist, or worse a North Vietnamese sympathizer? Had he said something unwise that fueled such sentiment?” Deaton would not say. With that letter in his pocket, a pall hung over him on Dec. 17.

Staff Sgt. Joe Musial, on the radio, in Company D, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), learns that the rest of his company is pinned down on the Bong Son plain of the central coastlands in February 1967. Just a couple of months earlier, in December 1966, Company D, 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, found itself in a similar predicament in the same region. (Robert Hodierne)

Staff Sgt. Joe Musial, on the radio, in Company D, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), learns that the rest of his company is pinned down on the Bong Son plain of the central coastlands in February 1967. Just a couple of months earlier, in December 1966, Company D, 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, found itself in a similar predicament in the same region. (Robert Hodierne)In a comprehensive account of the 506 Valley battle, 1st Lt. Steven Schopp of the 1st Cavalry Division History Detachment, described how events unfolded: Delta Company had formed an assault line facing a hedgerow. Feiner’s 3rd Platoon was on the right or south end. Prindle’s 2nd Platoon was on the left, north end. The NVA was positioned just beyond a second hedgerow. “But no one was aware of that,” Schopp noted. “The enemy positions were of the cleverest camouflage, impossible to detect.”

Delta passed the first hedgerow and was out in the open again, not 10 feet from the second hedge, when “the enemy at last revealed their presence with a fusillade of bullets,” Schopp wrote. “The surprise was effective. Delta was now in the open with no place to turn except over more open ground.”

The first enemy burst downed Pfc. Timothy Ewing and Deaton. The NVA found Deaton still alive and “put another burst in him,” Schopp recorded, adding that squad leader Sgt. William Cook was fatally wounded. Spc. 4 Michael Anderson, the medic, moved to Ewing, who was still alive, but his lung had been punctured, and he was having trouble breathing. Anderson tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. “Just then, an enemy bullet hit across his hand,” Schopp stated. “Anderson continued his job all afternoon and into the night. It was nearly one o’clock the next morning when he stopped to patch his own wounded hand.” He was unable to save Ewing.

Meanwhile, Pfc. Roger Hattersley was pinned down as “enemy bullets kept churning the dirt on both sides of him,” Schopp wrote. “He fired all his ammo from there and then ran in the open to where Deaton was lying, picked up 200 rounds, and ran back.” Hattersley shot up three-fourths of that ammo and then charged the bunker, killing at least one NVA soldier. The American was hit in the right shoulder but made it back to safety and was later medevaced.

The killing continued unabated. The chaos of battle reigned. Explosions rent the battlefield, bullets crack, and men yell and moan.

Feiner’s 3rd Platoon was bogged down as close as 20 feet from the NVA bunkers and “spider holes,” rounded one-man foxholes. The interlocking fire from NVA positions, almost impossible to see, picked off platoon members one by one.

At the same time, Prindle’s 2nd Platoon approached the bunker line. As Pfc. Eleazar Trevino started through a small hole in the hedgerow; he was struck by a sniper bullet, according to Schopp’s account. Spc. 4 James Jeffers, close behind, moved toward his wounded comrade, but Trevino motioned him back.

Someone shouted, “Stay back; there are snipers all over.” Platoon Sgt. Rogue Perpetua Jr. and Pfc. Angel Luna went through another opening in the hedgerow. “Perpetua spotted a machine gun bunker and charged for it,” Schopp relates. “He was right on top of it when he was hit.” The sergeant’s helmet had 11 bullet holes in it. Luna was killed by a sniper as Perpetua fell.

Cox, the lieutenant serving as Delta’s commanding officer, also was shot. Platoon Sgt. Donald Leemhis, attempting to reach him, was shot through the neck. He fell dead next to Cox, already dead. Close by medic Pfc. Alton Kennedy, a private first class, was treating the wounded and dragging them “out of the fire-swept field,” Schopp wrote. “Kennedy made two trips, braving the bullets despite pleas for him to stay back. He couldn’t bring himself to ignore the pitiful plaintive cries of, ‘Medic, help, Oh God, help!’ Moving out again, Kennedy was wounded on his third trip. His fourth was his last. Kennedy gave his life to save others.”

Pfc. Richard Rock, a radio telephone operator in 2nd Platoon, emerged from the hedgerow. Rock was the second non-airborne trooper to show up in his platoon when the 1st Brigade (Airborne) began filling its ranks with non-airborne infantry units in late 1966.

He became known as “NAP2,” for “non-airborne person No. 2.” Staff Sgt. Harry Forsythe, considered a “tough” noncommissioned officer, often teased Rock about cowardice: “NAP2, if I see you run away in a firefight, I’m going to fill your back with holes.”

Coming out of the hedgerow, Rock witnessed Perpetua getting shot in the head. Soldiers on all sides of him were being hit and falling. Running to a clump of bushes in front of him, Rock observed bullets hitting the ground. They could only have been coming from the trees. Rock shrugged off his radio, rolled over, and fired three-round bursts into the trees, emptying 12 magazines. He then ran to the nearest dead trooper to get more ammo. “I saw so many wounded and thought, ‘somebody has to do something to help these poor guys,’” Rock said in an interview with this article’s author. “Realizing that all the NCOs were dead or wounded, I concluded that somebody was me.”

Bullets were snapping around Rock. He patched up two troopers who were badly wounded, then fired his M16 rifle at a bunker to no effect. Seeing an M79 grenade launcher and ammo on the ground, he ran and grabbed the weapon, then stood up to shoot over the bush in front of him. His hurried first “blooper” sailed about 4 feet over the bunker. The enemy machine gun chattered. His next shot hit the corner of the bunker opening. On the third shot, he stood up, again exposing himself. Yet he took his time, aimed carefully, controlled his breathing and trigger pull, and sent a round through the bunker opening, silencing the machine gun.

Feiner and Forsythe attempted to bring in artillery, but neither could pinpoint his location on a map because they were enveloped in a thick jungle and couldn’t see the hills that would have established their position. They did a position estimate and called in smoke to confirm, but the smoke rounds were too far away and could not be seen because of the dense jungle. Their position estimate was incorrect by 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) to the east. It almost didn’t matter because Delta Company’s closeness to the NVA positions and the large number of helicopters in the air ruled out artillery fire for fear of hitting U.S. troops.

Rock continued to patch up the wounded. He retrieved weapons for those who could hold one, gave each man a sector to watch, and said, “Kill anything that moves.”

Picking up the wounded by the collar, he dragged them to a safe area, making multiple trips back and forth while under fire.

A staff sergeant in the 1st Cavalry Division takes stock of his situation. After the Dec. 17 fight, survivors returned to the battlefield to assess the losses and see if there were men who could be saved. (Robert Hodierne)

A staff sergeant in the 1st Cavalry Division takes stock of his situation. After the Dec. 17 fight, survivors returned to the battlefield to assess the losses and see if there were men who could be saved. (Robert Hodierne)Helicopter rocket artillery roared in but had only a momentary effect on the bunkers and wounded some of the Delta GIs. It was called off. During the battle, two helicopters were shot down, and seven were damaged so severely that they could no longer fly.

Prindle, near the left side of the Delta line, was blocked by a barbed wire fence. As Prindle reached out to cut the barbed wire, Rock saw the lieutenant’s watch casing disappear from his left wrist. The bullet left the base of the watch and the band intact. Undeterred, Prindle reached out again to cut the wire. This time a bullet hit in the front of his helmet, passed around the inside and blew an exit hole out the back, briefly knocking him unconscious.

Like a fighter recovering from a knockdown, Prindle jumped up, grabbed a machine gun, and yelled, “Let’s go!” He, Rock, and Spc. 4 Calvin Brown headed toward a bunker to rescue soldiers lying out in no man’s land. Prindle fired the machine gun directly into the bunker while Rock and Brown went to get Trevino and a wounded medic. After that successful attempt, Prindle continued to use the machine gun to attack bunkers and suppress enemy fire long enough to allow for the rescue of other wounded. When his gun slowed from overheating, he found another barrel to replace the original and returned to the fight.

About three hours into the battle, Rock heard Forsythe’s voice rise in the distance: “Hey Rock, are you still alive?” Rock yelled back, “Yeah, why?” The sergeant asked, “Are you gonna run away?” Rock answered, “Why?” Forsythe’s response: “If you do, I wanna go with you.” Despite the circumstances, Rock had to laugh.

After sunset, Delta Company and other elements of the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, were consolidated at a landing zone about a half mile northwest of the battle area. Wounded men needed to be medevaced. Flying conditions were terrible, with poor visibility, a low ceiling, and hostile groundfire. While green tracers converged on him, Feiner bravely pointed two flashlights in the air to guide the medevac choppers.

Later, a wounded man arrived from the jungle. Struggling to speak, he said there were still men alive in the killing zone. First Sgt. Gene Helgeson assembled a medical team to look for anyone who might still be alive. The volunteers included Capt. Edward Wagner, the battalion surgeon, Spc. 5 Donattis de Baitis, and Spc. 4 James Ennis, both combat medics.

NVA soldiers were still plentiful in the area. The Schopp report describes what happened next: “Helgeson’s team crept around, looking for American wounded, treating them and pulling them back for evacuation. There can be no doubt that Helgeson and crew put life back into men who otherwise would have surely died from their wounds.”

Having spent hours lying wounded and alone, faced with marauding North Vietnamese and fending off insects, Noone was near despair. He remembers seeing someone quietly approaching him in the dark and fearing that it was yet another NVA soldier. But a shadowy figure grabbed his wrist and whispered, “This one’s still alive.” The shadowy figure was Wagner, in a precarious situation for a battalion surgeon just out of medical school.

Helgeson’s team carried Noone back to the landing zone, where he was treated and kept alive. It was not possible to bring in medevac choppers because of fog, so he was evacuated at the first opportunity the next morning. The medevac helicopter sped at maximum power to the hospital, where the staff immediately took Noone into surgery. Giant ants still infested his body and clothing. The surgeons sprayed anesthetic gas to knock out and disperse the ants before they could work on Noone. He was given last rites twice before his eventual recovery at a hospital in Japan.

Pfc. Michael Noone, shot three times in the battle and almost left for dead, survived his encounter with the giant “blood ants” and recovered at the 106th General Hospital, Kishine Barracks, Yokohama, Japan. (Michael Noone collection)

Pfc. Michael Noone, shot three times in the battle and almost left for dead, survived his encounter with the giant “blood ants” and recovered at the 106th General Hospital, Kishine Barracks, Yokohama, Japan. (Michael Noone collection)By the end of the day on Dec. 17, Delta Company’s fighting force had been reduced to half its size. Only 35 of 62 men in the 2nd and 3rd platoons were alive and functioning.

The acting commanding officer, Cox, was killed, as were all of the platoon sergeants and most of the other noncommissioned officers.

Deaton, the soldier with the wish-you-would-be-killed letter in his pocket, was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star with a “V” device for valor. The accompanying citation stated: “Several men in the platoon were felled during the opening volley of fire… Standing up in the fire-swept field, Specialist Deaton led his men straight at the startled enemy force…In the exchange of intense close-in fire, Specialist Deaton was mortally wounded.”

The remnants of Delta were attached to Charlie Company, where they spent the night being tormented by snipers. Spc. 4 Carlisle Mahto from Bravo Company shot 10 snipers out of the trees using a starlight night scope, which magnified light from stars and the moon to illuminate the area viewed.

That night, most of the NVA had dispersed in small groups and headed into the mountains. The battalion searched the village and surrounding area. By Dec. 19, a total of 95 NVA bodies had been found.

The next morning, Prindle was told to report to a helicopter that had just landed. The lieutenant in battle-worn clothes found a major wearing clean, starched fatigues, directing him to get in the chopper. A high-ranking officer wanted to see Prindle, perhaps for an award. Prindle cursed and told the major: “I’m not leaving my men. They’ve just been through hell.” He turned and walked away.

In the following days, the 1st Battalion, 12th Cavalry, pursued the NVA into the mountains. Intelligence gathered from prisoners indicated they were with the 7th and 9th battalions of the NVA 18th Regiment. The 506 Valley battle and subsequent pursuit left the regiment in disarray. It was unable to carry out existing orders to participate in coordinated attacks on nearby LZ Bird and LZ Pony on Dec. 23. Instead, the NVA ordered the 22nd Regiment to attack LZ Bird on Dec. 27. Much of LZ Bird was overrun by the North Vietnamese, but ultimately the attack was repelled. The NVA also was unable to launch effective attacks against LZ Pony.