John Podlaski's Blog, page 12

August 25, 2023

‘People Feel Expendable’—Military Could Lower Suicide Rate With Focus on Quality of Life

By ANNE MARSHALL-CHALMERS

Many of my readers have children in the military. This is an eye-opening report of the current conditions. It’s a lot different from when we served and combat doesn’t have to be the stresser to consider suicide. I think this is important enough for everybody to read and share.

Active-duty service members and veterans thinking of harming themselves can get free crisis care. Contact the Military Crisis Line at 988, then press 1, or access online chat by texting 838255.

In the summer of 2022, Craig Bryan, a psychologist, listened as a young service member explained why some days life didn’t seem worth living. The man in his early 20s didn’t point to combat-related trauma or the burden of physical injury. He felt depleted from his job in finance, specifically processing reimbursements for his fellow service members.

As Bryan recalls, the young man with dark hair, a thin frame, and a cautious way of speaking recounted how the software used by the Defense Department often resulted in errors or long delays. As a result, service members would come to his desk to yell about their lack of payment, and when he tried to correct the problems, the software would cause his computer to crash. Rebooting took 20 minutes, and it was not uncommon for the upset individual to complain to the man’s supervisor, who would later shout at him for poor performance.

The service member often stayed up working until midnight (only to oversleep for morning exercise, which resulted in more reprimanding) and said that when he thought about his future, he drifted into hopelessness.

Psychologist Craig Bryan speaks to a room of David Grant USAF Medical Center mental health care providers at Travis Air Force Base, California, in 2022. Bryan, a leading national expert on military suicide, taught advanced skills training for the providers during a two-day session. Photo by Lan Kim, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

“What’s the point of any of this?” Bryan recalls him saying. That triggered alarms in Bryan’s head. “When I heard that I was like, Holy shit, this kid’s at risk for suicide.”

Bryan didn’t think work stress alone might result in suicide. But the young service member appeared depressed. If he were to break up with a partner or lose a loved one, that would only push him closer toward risk. Easy access to a gun would multiply the risk further.

Another concern: his age. About half of the military suicides on Defense Department property involve people 25 years old or younger.

This young man was one of nearly 3,000 individuals across nine military installations interviewed for a report released earlier this year by the Suicide Prevention and Response Independent Review Committee, which formed at the direction of Congress under Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin in the spring of 2022.

Bryan, who deployed to Iraq in 2009 as a psychologist in the Air Force and is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral health at Ohio State University, was one of 10 committee members who developed a 115-page report listing dozens of recommendations to improve service member well-being and reduce the persistent suicide problem. Since the 2001 launch of the war on terror, suicide rates have roughly doubled in the military.

After several months of talking with service members, their families, mental health providers, and others, Bryan started to view active-duty suicide as “death by a thousand paper cuts,” he says.

Those “paper cuts” range from a chronic shortage of behavioral health providers to a lack of computers for service members who must complete online training, delays in paychecks and reimbursements, and no air conditioning in sweltering barracks—complaints Bryan and his colleagues heard repeatedly.

“There were just barriers, I would say, to successful living,” says Rebecca K. Blais, a psychologist who served on the committee and says she was “struck” by the volume of daily stressors. Eliminating some of them, the committee argues, could help the mental state of service members, making them more resilient to whatever active duty throws at them. And while adding computers and improving housing may sound like an easy lift—especially considering the Defense Department’s $1.77 trillion budget—those familiar with how the military bureaucracy operates aren’t hopeful this report will result in significant, lasting change.

Graphic by Keith Pannell, courtesy of the U.S. Army.

“We know a lot about the problem—we know what we need to do,” says M. David Rudd, a psychology professor at the University of Memphis who has researched military suicide for more than three decades. “I think the probability is it won’t be done.”

Rudd blames the military mindset. The Defense Department should overhaul what defines “military readiness,” he says, calling it the most critical step in suicide prevention. Rather than evaluating command staff based on their training schedules, physical fitness scores, and marksmanship performance, he says, there should also be accountability for the mental fitness of the people in their units.

“Everybody views that as not related to military readiness,” he says, adding that military culture should shift to a more comprehensive view on military readiness that includes the toll of daily stressors, such as struggling to buy groceries. (A 2018 RAND Corporation report found that roughly 26% of active-duty service members are food insecure.) “If somebody can’t get paid, that impairs military readiness. You just don’t have people who think that way. That’s just not the way commanders think.”

And, many of the findings in the SPRIRC report aren’t new, Rudd says. Over the last 15 years, several reports across the services have detailed ways the Defense Department could tackle suicide—but the findings have so far failed to spark deep, sustained action.

“If the recommendations that have been repeatedly raised by multiple groups are not implemented, there is little reason to expect that suicides among military personnel will drop,” the SPRIRC report reads.

A plan to implement many of the SPRIRC’s recommendations is past the June due date set by Austin, but a Defense Department spokesperson says it’s coming.

‘Not Everyone Who Dies by Suicide Has a Mental Health Condition’Prior to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, civilian suicide rates were far higher than those in the military when comparing age groups. That flipped about five years into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Rudd says. In 2021, a “Costs of War” research paper out of Brown University estimated nearly 32,000 active-duty personnel and veterans of the post-9/11 wars died by suicide—significantly more than the 7,057 service members killed during combat in that same time frame.

Military officials recommend reaching out to people who may be having difficulties and then helping them get to resources, such as the suicide helpline if they are at risk for suicide. Photo illustration by Joshua J. Seybert, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

Despite millions of dollars of DOD research on the topic, the problem lingers. In the first quarter of 2023, the Army recorded 49 suicides, compared to 37 in the same time frame in 2022—according to the DOD’s most recent quarterly suicide report. The Marine Corps also reported an increase.

Outside military installations, suicide in America has surged in the last two decades, particularly among teens and young adults. The demand for mental and behavioral health services far outpaces available providers, a challenge that the military and Veterans Affairs face, as well.

At many installations, service members have to wait four to six weeks between psychotherapy sessions, reducing treatment efficacy and prolonging symptoms, according to the SPRIRC committee. The report lists ways to remedy this—many of which have been issued in the past—including expediting hiring and eliminating budget and statutory limitations that hinder the Defense Department’s ability to increase pay.

But Blais says it’s important to recognize suicide as a complex tangle of factors.

Capt. Anthony Priest, behavior health officer with 1st Signal Brigade, speaks with Company B, 304th Expeditionary Signal Battalion-Enhanced, in South Korea in 2022, about suicide. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army.

“I think one of the conceptions that people often have is that people who die by suicide have a diagnosable mental health condition,” she says. “And that’s certainly not the case.”

Mental health can falter when everyday problems compound, and that can also trigger verbal abuse between service members and their families, Blais says.

“Military service members are trained to survive anything and with the fewest amount of resources possible,” she says. “That is part of what they need to be able to do. But what we were seeing on installations is that they were doing that day to day when it wasn’t required.”

When three junior sailors killed themselves in April 2022 while serving on the same aircraft carrier, investigators found daily stress contributed. They were assigned to the USS George Washington, a ship that was in a years-long “midlife overhaul” at Huntington Ingalls Industries-Newport News Shipbuilding in Virginia. A Navy investigation released in May found that thousands of sailors who have worked and lived on the ship since 2017 endured a poor quality of life, despite more than two dozen complaints to the inspector general between 2020 and 2022 addressing uninhabitable living conditions, safety violations, mistreatment of sailors on the basis of gender and sexual orientation, and the mishandling of sexual assault allegations.

While no direct correlation was found among the deaths of the three sailors, the report details the unpleasantness of daily life. For instance, sailors often parked miles away without enough parking at the shipyard and endured an up to two-hour commute by bus in traffic jams—a slog that drained morale.

Living quarters for the hundreds of sailors lodging on the ship were often without WiFi or reliable cell phone service—lifelines in modern society. The parents of one of the deceased soldiers told NPR that their son often tried to sleep in his car, or he would occasionally break rules and drive eight hours to visit home, only to return to the ship sleep-deprived and weary.

‘It Makes People Feel Expendable’Programs that boost morale, improve mental health, and decrease suicide rates do exist. The Defense Department’s own research has identified several effective therapies that help prevent suicide. But, “there’s no plan to roll them out” and embed them as staples of the Military Health System, Bryan says.

The Army’s Holistic Health and Fitness program shows promise. Early data reflects a 37% reduction in suicides between 2019 and 2022 in units that have implemented it, according to an article in Army Times. But the SPRIRC committee found it’s not unusual for such successes to operate in a silo or when leadership changes within units, the program to fade away.

More than a decade ago, a task force with the same charge as SPRIRC—which issued many of the same recommendations—highlighted the need for a “positive command climate” and leadership that’s held accountable for the entire well-being of service members, not just the physical aspect of health.

U.S. Navy sailors assigned to the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis distributed pamphlets to raise awareness for suicide prevention at the floating accommodation facility, in Newport News, Virginia, in 2021. Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Thomas Pittman, courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

Blais, the psychologist, says there’s evidence of a recent change in how leaders are selected in the Army. The Battalion Command Assessment Program focuses not only on physical and cognitive requirements for effective leadership, but also integrates assessment of written and verbal communication skills, feedback from peers and subordinates, and results of interviews with psychologists. She’d like to see all branches adopt that model, she says. As it is now, the promotion system rewards people who’ve been in the military a long time and may be good at the mission side of the armed forces, but not necessarily at the leadership required to keep service members healthy.

“One of the things that we heard, for example, is we would ask commanders, ‘How do you address your service members when someone dies by suicide?’” she says. “And it’s like, ‘Well, we don’t talk about it. We don’t want to draw attention to it.’ And it wasn’t malicious, but they’re just like, ‘If we tell people it’s going to happen, then it’s going to happen more.’ And as a psychologist, it’s like, ‘No, that makes people feel like they’re expendable and that they don’t matter.’”

‘We’re Not Saying People Shouldn’t Have Guns’While nearly two dozen recommendations ranked as the top priority, only a handful related to limiting access to guns drew heated debate online, including one that proposed prohibiting the sale of guns and ammunition to troops younger than 25 years old on Defense Department property.

When The New York Post reported on the proposal, readers derided a “woke” military and the violation of the Second Amendment.

Defense Department data indicates about 66% of active-duty suicides, 72% of reserve suicides, and 78% of National Guard suicides involve firearms. Citing a policy change that required Israeli military personnel to store their military-issued weapons in armories over the weekend and how that led to a 40% reduction in the Israeli military’s suicide rate, SPRIRC offered policy proposals that also attempt to limit access to personal guns.

When she helped to craft recommendations, Blais reviewed data that indicated it was not uncommon for men between the ages of 18 to 24 to have recently gone through a breakup, get drunk, and then tried to kill themselves.

If that gun is harder to reach for? “At the worst, they would have a really bad hangover the next day,” Blais says. “We’re not saying that people shouldn’t have guns. We’re just saying that we might want to be more thoughtful about where guns are, where they’re located, who has access to them, and where.”

Graphic by David Smith, courtesy of the U.S. Marine Corps.

Rudd likens the controversy to seat belts. Though the initial requirement of seatbelts ignited rally cries of lost freedom, eventually the federal government realized the safety benefits were too great to ignore. Since suicides are often hard to predict, he says, “steps to improve safety have a positive impact, just like seatbelts.”

The report also recommends screening for excessive alcohol use and displaying alcohol less prominently in military exchanges.

In March, the Defense Department announced a few of the SPRIRC’s recommendations would be adopted immediately as a task force worked through a more permanent, thorough plan. Those recommendations included expediting the hiring of behavioral health providers, screening for excessive alcohol use during primary care appointments, and improving the scheduling of behavioral health appointments.

In April, the Defense Health Agency began a pilot program that allows service members to book several behavioral health appointments at once—rather than having to schedule a follow-up after each visit—with the hope that the program will expand across the Military Health System, a Defense Department spokesperson tells The War Horse.

In an emailed statement, Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, a Democrat from New York who serves on the Armed Services Committee, says she expects the Defense Department to take this report “seriously.” She’s pushed the military for years to ease career stressors and strengthen mental health services.

“I will be watching for real progress,” she says.

Bryan is watching too.

Though it’s been months since he sat in a conference room listening to that young, stressed-out service member, he finds himself thinking about him often.

He remembers the young man looked crumpled, exhausted—like someone under so much pressure, with such minimal relief, that he couldn’t picture his future as anything but grim.

“He is an exemplar of how institutional factors and quality of life matters are so important for understanding the emergence of suicidal thinking and suicidal behavior,” Bryan says.

This War Horse investigation was reported by Anne Marshall-Chalmers, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Jasper Lo, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

This article originally appeared on THE WARHORSE website on 8-24-2023. Here is the direct link:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 22, 2023

Lima Charlie Show Special

From Lima Charlie via LinkedIn

With school about to begin we thought it was a great idea to put together our first series of “Writer’s Block”! Please join us this Wednesday evening at 6 PM (est) on 105.3 FM, 1440 AM, or webrradio.com. You will hear from Sam Baker, John Podlaski, and Brian O’Hare; three of our nation’s finest authors who have all served in the military!

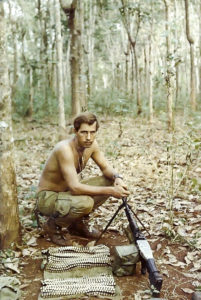

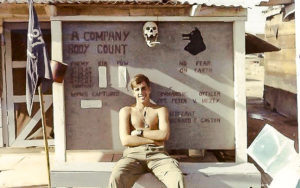

Below is John Podlaski. He is a Vietnam Veteran and a writer of several books. Please check out John’s website for further information: https://lnkd.in/gVHvGxSb

August 19, 2023

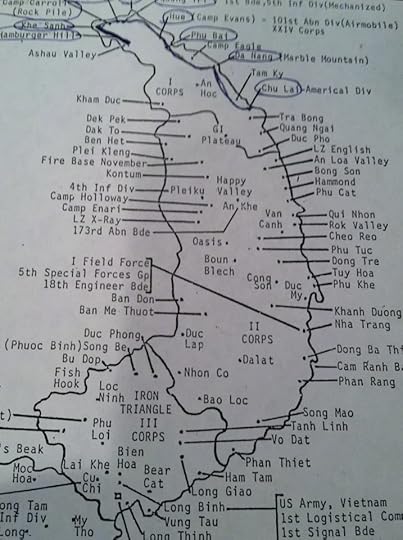

WHAT WAS THE CONCEPT BEHIND FIRE BASES IN VIETNAM?

A firebase in Vietnam, wherever in Vietnam, would be well-known to whoever habituated one anywhere. There were several thousand firebases during the conflict, manned by many units and many men, but they were all the same. Similar to the 19th-century fort concept, fire support bases in Vietnam could reinforce each other across long distances with powerful effects. Read the article to learn more about these firebases.

Vietnam was a non-linear war. There were no front lines with enemies on one side and friendlies on the other. Tactical problems could become very complex, with the enemy potentially in any or all directions. It was vital to be able to observe and fire 360 degrees all-around.

Although atypical of most 20th-century warfare, those conditions were not necessarily unique to military history. Perhaps the closest American experience was the Indian Wars of the 19th century—with isolated forts established to control certain areas and provide security to overland travel routes and civilian settlements in the sector.

One solution to the Vietnam War tactical problem was the fire support base (or firebase). Most 19th-century forts were isolated and had to be self-sufficient. Thanks to 20th-century technology, the firebases used by the allies in Vietnam could communicate with each other instantly and could be resupplied and reinforced by air.

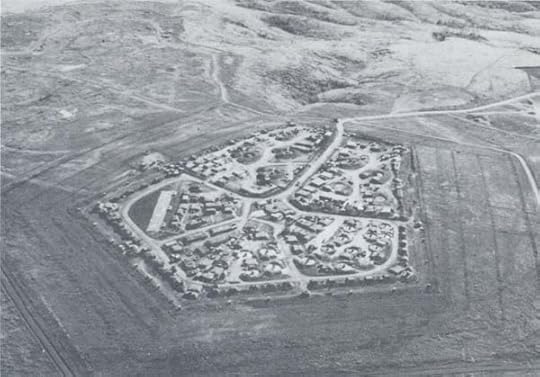

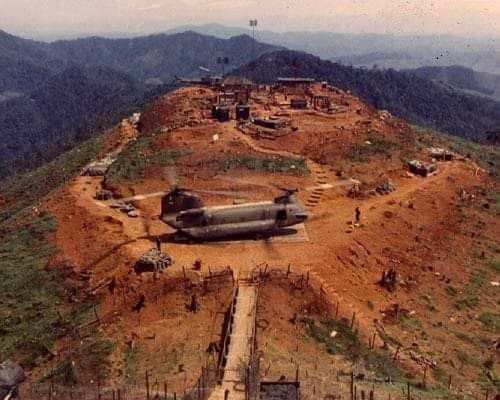

WHAT WAS A FIREBASE?The fire support base was a combined infantry-artillery position that sometimes included armor. Depending on the planned duration of the position, firebases could be dug-in heavily and reinforced with engineer assets.

Perhaps the greatest strength of the firebases was their ability to cover each other with mutually supporting fires over great distances. It is a long-standing principle of firepower that massing fires is the most effective way to use artillery.

Through the 19th century, the only way to mass fires was to physically group the guns together on the ground. Between World Wars I and II, improved communications combined with innovative advances in fire direction control techniques made it possible to mass fires instantly on enemy targets from many widely-dispersed guns.

Firebases could reinforce the fires of their own internal guns with the guns of any or all other firebases within artillery range. It was a powerful multiplier effect.

HOW WERE FIREBASES SET UP?

HOW WERE FIREBASES SET UP?The size, composition, and positional duration of a firebase depended on the planning factors of mission, enemy, terrain, and troop availability. Some firebases were very large and held positions for months or longer. Other firebases were relatively small and remained in position for days or weeks. A smaller firebase might consist of a company of infantry with a two-gun artillery platoon in the center of the position. A larger firebase might consist of two or three infantry companies, or possibly an entire battalion.

The artillery would consist of an entire six-gun battery. Instead of being positioned in the normal staggered line, the guns were deployed in a star position, with the base piece at the center and the other five guns forming the points of the star to provide rapid and effective fire in any direction. Smaller firebases with two or four howitzers deployed their guns when possible in square or triangle formations.

Firebases on flatter terrain were usually round, and those on ridges generally were rectangular due to terrain. Most larger firebases contained a helicopter landing pad for resupply and medical evacuation. When a firebase deployed forward, the guns often were moved by air.

FIREBASES USED IN ATTACK AND DEFENSEThe firebases were not merely passive defensive positions. Infantry patrols aggressively pushed out from the perimeter, day and night, but usually stayed within the guns’ maximum effective range fan—roughly 11,000 meters for 105mm howitzers and 14,000 meters for 155mm howitzers. When a patrol made contact, it could call for fire support not only from the guns of its own firebase but those of any other firebase in range.

The firebases, of course, invited attack. One gun inside the firebase usually fired illumination rounds to deprive attackers of the cover of darkness. Other guns delivered fires where needed outward from the perimeter. Firing close to friendly troops could be complex because of the large bursting radius of HE ammunition. The solution to that problem was the M-546 Antipersonnel Round for the 105mm howitzer. Popularly called the “Beehive Round,” it fired 8,000 steel flechettes, triggered by a time fuze set to detonate just outside the perimeter. A green star cluster hand flare fired just before the Beehive warned troops on the perimeter to take cover.

Between 1961 and 1973, U.S. and allied forces established more than 8,000 fire support bases in Vietnam; only a small fraction existed at any given time.

Some of the war’s fiercest battles were fought over firebases, including Firebase Ripcord in Thua Thien Province (July 1-23, 1970); Firebase Mary Ann in Quang Tin Province (March 28, 1970); and Firebase Gold in Tay Ninh Province (March 21, 1967). Neither the VC nor the NVA ever managed to overrun a U.S. forces firebase.

For more information about the firebase battles mentioned above, go to the magnifying glass (search key) at the top of this page and type in the name of one of the firebases for a link to that article.

For more on firebases, please refer to another article on this website: https://cherrieswriter.com/2022/03/26/hill-of-angels/

This article originally appeared on History.net. Photos added by Admin. of this website. Here’s the direct link:

What Was the Concept Behind Fire Bases in Vietnam?

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 12, 2023

I’ll Be Your Wingman

He should have been part of that flight. Instead, his best friend volunteered to take it and died along with two other pilots when their jets collided in mid-air. The author’s message in this article lifts others up in memory of lost comrades. Highly recommended. A read you should not miss.

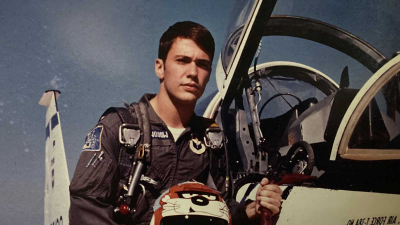

by Dan Woodward

I Was a Pilot. They Were My Brothers. I Can Still Feel Them.

IMPACT minus 2 hours and 1 minuteYou could always identify the schedulers. They were the ones who ran from room to room attempting to fill flight sorties when instructor pilots had canceled for some reason or another. That morning was no different.

“Hey, Dan,” Tom said with a mix of hope and pleading in his voice, standing square in front of my desk waving a binder to emphasize the importance of the moment. “Could you help me fill a four-ship? The brief is in 27 minutes. My guest help just dropped.”

I looked up from my desk where I was completing paperwork from a student check ride.

A T-38 Talon four-ship formation flies over the Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup on July 27, 2022, in Sacramento, California. “It was a great jet nicknamed ‘The White Rocket.’ … But it was also unforgiving and unpredictable with the unprepared at the controls,” writes Dan Woodward. Photo by Senior Airman Frederick A. Brown, courtesy of the U.S. Air Force.

I liked Tom. Like almost everybody in the squadron, he was about 25 years old, lean, and newly married, with a lifetime of great dreams ahead of him. His hair was dark brown, accentuating dark brown eyes, an ever-present five o’clock shadow, and smooth olive skin.

Figuratively, we were brothers. Both Air Force instructor pilots flying advanced T-38 trainers. It was a great jet nicknamed “The White Rocket.” Very fast and able to bend a pretty sharp turn in blower, a term we used for the afterburners which added a real kick of thrust. But it was also unforgiving and unpredictable with the unprepared at the controls.

Tom flashed me a used-car salesman grin. I gave him a look that said “knock it off” and his smile grew quickly even.

“What the hell, Tom?” I asked. “Twenty-seven minutes to a four-ship brief?”

“I know,” he said, “but Maj. Ski just dropped. I gotta fill this sortie. Strong student.”

Ski had a reputation for doing this.

I knew the drill. I had been a scheduler as well, and this was my job and Tom knew it. I had the white space on my schedule, and he knew that, too.

“OK, Tom, OK. I’ll fill the seat. But, do me a favor, ask Tony, too. He’s a stick hog, and I really want to catch a workout over lunch.”

Tony sat next to me in this office. He really was a stick hog, meaning he would grab a flight every chance he got. He was also a good friend and a pilot training classmate of mine. We received our wings the same day.

Six-foot-two and around 200 pounds, he was a gregarious guy that you always felt was just a step away from giving you a bear hug that would crush you like a grape. Like Tom, Tony was my brother.

Tony was also finishing paperwork from a check ride, so Tom dutifully stepped to his desk and unloaded the same pleading request to Tony, adding something about me taking the sortie, if he could not. As expected, Tony the stick hog took the sortie, and Tom headed out the door after tapping my desk and saying he had it covered.

“Great,” I said.

It was the last time I would see Tom.

Twenty minutes later, Tony walked by my desk. He looked like he was on his way to benchpress a refrigerator. That’s how he always looked to me. It was the last time I would see Tony, too.

IMPACT minus one hour and 38 minutesAdditional paperwork complete, I popped up from my desk, grabbed my workout bag and headed through the length of the squadron. It smelled a little like a locker room and looked like a beehive, as students and instructors hurried in and out of flight rooms and the life support area where parachutes, helmets, masks, and G-suits—designed to keep you conscious when G-forces pushed the blood to your feet—were stored. The operations desk and flying supervisor had the usual 10 or so people ready to go, and a solid hundred sorties for the day were posted across a monstrous scheduling board in four-minute increments.

I walked past J Flight where Tom and Tony were briefing the four-ship. I didn’t give it a thought. I put one foot in front of the other.

I popped out the squadron door and headed for my car, walking past Tony’s giant, ancient Cadillac or Chrysler or whatever it was. All I knew was that it was old and enormous and sounded like an old man with bad knees when Tony fired it up. I hopped in my car and headed for the gym.

IMPACT minus 58 minutes“Heat check,” the student blurted into his mask-integrated microphone.

“Two, three, four,” came the response, indicating the formation was ready to taxi. You did not screw this part up. You sounded good and you looked good when you taxied in front of God and country and, most importantly, the other guys in your squadron. If you didn’t, everyone would shit on you.

“Heat 21 flight, cleared to taxi to runway 31 center, wind 330 at 10, altimeter 29.98,” ground control transmitted.

“Heat 21, 29.98,” came the student’s response.

About this time, I headed out of the gym after changing and started my usual run around the base. It would take around 40 minutes, then another 20 or so for a shower and quick slide back into my flight suit before heading to the squadron.

Everything was on track that day, until it was not.

“Why,” a statue dedicated in 1967 to service members, stands in front of the Placer County offices in Auburn, California, which Dan Woodward visits often. Photo courtesy of the author.

The formation executed an eight-second interval launch with lead accelerating to 300 knots, while the additional three jets accelerated to as much as 450 knots in blower to join the formation, with three-foot wingtip separation.

Another buddy of mine was lead for the moment, and he took the formation through the Pickwick departure corridor en route to the Pickwick military operating area. Leveling at 14,000 feet, the formation was cleared by Memphis Center for Pickwick high and low military operations, meaning the flight could use every foot from 8,000 to 23,000 feet.

They started to climb.

IMPACT minus 19 minutesAnything still could have changed at this point, but it didn’t.

I headed out of the gym, freshly showered and getting mentally ready for my late afternoon check flight. I pulled into the squadron parking lot and hopped out of my car, walking past a giant mural painted on the squadron exterior that said simply, “Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.” We really did live that way.

Through the squadron doors, I returned to the beehive, walking the length of the building to my desk. There, I pulled out a bagged lunch from my side drawer and swallowed a peanut butter and jelly sandwich by practically unhinging my lower jaw from my upper jaw like a snake. After all, why waste time eating when all that did was get in the way of the mission? Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.

I glanced at Tony’s desk. His flight jacket was draped over his chair. Plexiglass covered his desk and protected a dozen or so dollar bills presented by students following their first flight, and another dozen or so patches from student classes he had flown with. The lights flickered as they did from time to time, and in that chair, for an instant my gregarious brother sat, and then he was gone.

IMPACTPhysics is a profoundly unforgiving mistress. For every action there is a reaction. Military aviation marries you to this reality and all others in the natural world. Tony knew this. We all did. But it didn’t make things easier when physics turned on you.

He pitched up and pulled right and then down to the buffet, where the jet told him he was demanding all it had. As number three in the four-ship, he was responsible for taking his aircraft and the number four aircraft back to the lead element, solving the complicated geometry of closing two jets on another two jets at 400 knots as they maneuvered 4,000 feet away.

This was a tactical rejoin, a basic building block in creating a combat aviator. Spread wide to facilitate clearing and radar coverage for enemy jets in the future, flight lead had decided to bring the formation back to three-foot wingtip separation to practice other skills.

Crossing behind lead at nearly 500 knots, Tony pitched to the outside of the turn, and, needing additional closure to expeditiously join, he reversed and pulled hard back to the inside.

His wingman, the number four aircraft in the formation, could not respond quickly enough and pulled to match Tony’s pull too late to clear the flight path. Both aircraft exploded on impact, with Tony’s jet smashing his wingman into unrecognizable debris behind the front cockpit. Tony, Tom, and Will, Tony’s student, touched the hand of God, and chaos brutally shoved itself into the lives of everyone they knew.

Dan Woodward pictured near the end of his pilot training. One of his classmates, Tony, would later die in a T-38 trainer crash. Photo courtesy of the author.

This story goes on, but last night I asked Tony to help me with clarity and brevity, so he took my pen. Did I mention he was a stick hog?

I sat at my desk and the lights flickered. I looked at my friend Dan. He had just eaten a peanut butter and jelly sandwich and was wondering what was going on as the squadron went into lockdown.

I would not be back, but I would always be around. Dan would always remember me, and Tom and Will too. He was our brother. I would never tell him that, but he knew it.

He would meet my mom, pack my clothes, meticulously build my service dress, pay my bills, place a new medal on my uniform, and drive my car home for the last time. I would not thank him, but he knew I would if I could.

Someday when the leaves were changing in his life, and the time was right with brothers and sisters he knew forever but met only briefly, a question long buried would come to the surface.

Why? Why them and not me? Why that day? Why that way?

Here is what I told him.

You were not to blame. You could not know what rested in the future, and in the future, you must not dwell on the pain of the past.

You can disrupt the ripples in a pond, but you cannot stop them. Be at peace with it. I am. I took the flight. You did not give it to me.

Your life gives value to mine. You lived on for a reason, and I want nothing more than to see that reason fulfilled.

When you walked by J Flight, you put one foot in front of the other. Keep doing that.

For every action there is a reaction. React toward the light and away from the dark. I do not need you closer to me. Not yet.

My friend, lift up those around you. Inspire them. Speak for me. Act for me. Laugh for me. But do not cry for me. There is no time for that, because you never know when you too will touch the hand of God.

I got up from my desk and walked over to Dan. He sat there still confused by the commotion of the moment unfolding around him. I gave him a hug and crushed him like a grape. I always wanted to do that. He would be fine.

The lights flickered, and I was gone. But always around.

IMPACT plus one secondTumbling end over end, the remaining intact portion of the number four aircraft plummeted toward earth with Vince strapped to his ejection seat. He pulled the ejection seat handgrips and the rocket shot him clear of the wreckage, but the seat was damaged on impact and failed to automatically deploy his chute. He was fighting physics to the death, tumbling and spinning like a top; earth and sky blended together in a whirlwind of terror. After 17,000 feet in free fall, Vince managed to break free of the seat and got a full chute 400 feet above the ground. Physics had toyed with him.

The lead two ships transitioned to a highly maneuverable chase formation and descended slowly, careful to remain well clear of any falling wreckage. The senior instructor transmitted details back to the operations supervisor, triggering the implementation of a mountain of checklists. Support aircraft were launched with full fuel loads, and would rotate on station over the crash site for as long as daylight permitted.

Three were lost, one miracle was found, and the remaining four in the formation were changed forever.

IMPACT plus 48 hoursThe parking lot was empty, except for Tony’s car. Sunday morning was always quiet. I parked nearby and carried a cardboard box into the squadron. I had a key.

There were ghosts here. I could feel them. My brothers.

I walked into my flight room and over to Tony’s desk. You could not think about an act like this. You just did it.

I pulled the plexiglass off his desk and collected his patches and dollars and a few other things. I took his flight jacket from the chair and dropped it into the box. I sat at his desk, violating every possible measure of privacy, opening drawers and dropping their contents onto his jacket. I paused at a picture of him receiving his wings. For good luck, tradition held that they would be broken by the recipient, that day. I wondered if he had done that.

This was my job. I was Tony’s summary court officer, under orders to account for everything: pay his bills, resolve his issues, and serve as the Air Force representative to his mom and family. I would do this job perfectly. I owed it to Tony. Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.

I left the squadron and its ghosts as I found it, quiet, reflective, and alone, and went to Tony’s car. I had located his keys the day I was placed on orders, and I opened the door, tossed the box onto the passenger’s seat, and fired it up. True to form, it sounded like an old man with bad knees.

I drove the car from the squadron for the last time.

IMPACT plus 96 hoursTony’s dress blue uniform was back from the cleaners. Everything except his wings would be new. Those would stay.

I measured everything. “That looks about right” would not work here. It took 10 minutes for each “U.S.” lapel insignia as I moved the two needle-like pins back and forth with barely a thread’s difference and lined everything up perfectly with a ruler. Someone else could do this as well. I didn’t care. This was my job.

The extent to which I had violated every measure of his privacy was now nearly complete. His lease was broken and paid, his electric and trash bills paid, his laundry washed and cleaned. The packers were scheduled for one week from Friday. We would ship his car.

I met his mom in Tony’s home. I wore my flight suit and my black-and-gold squadron neck scarf. She liked the scarf and I made certain there would be one in Tony’s shipment. We walked the place largely in silence, and she gave occasional instructions about shipping his things. I took mental notes.

That day, I received a small plastic bag with the items Tony had with him when physics severed his dreams from reality. I cried alone. If you really had to cry, you did it alone. I was a man and a pilot. Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way.

IMPACT plus 5 daysThe memorial service was held in the base chapel. Three were lost, one miracle survived, and thousands more lives were changed forever. I sat in one of the last pews and listened to every word. I prayed when I was told. This would help with closure for some, and for others, it would push things deep inside where they might never emerge. Or maybe they would.

IMPACT plus 61 yearsI love this place. Sequestered in the Adirondack Mountains of middle New York, the tranquility is cathartic and deep. The leaves are changing and falling at the same time, leaving a patchwork quilt of red, amber, and gold on brilliant green lawns and on the limbs above. This place is old, like me, with mountains worn smooth and gentle from years of battles with the forces of nature. The woods are deep and the trails inviting, with overgrown and hanging limbs often forming arches of natural magnificence.

In the mornings, I wander these trails, eventually returning to be with friends who years before I had met in this place to talk about lives of service. These talks often exposed life’s five great emotional conflicts: life versus death, living versus dying, truth versus deception, love versus hate, and peace versus war.

Within all these talks, my friends helped bring me the answer to the question of “why.” Why them and not me? Why that day? Why that way?

Among my friends were the poet, the artist, the journalist, the warrior, the scientist, the quiet, the conflicted, the wounded, the scarred, and the searching. I was in the last of this group, but like most, I dabbled in them all from time to time.

This morning, I awake early and set out on a path that is new to me. I travel alone. This path seems to insist on it.

Pausing at a pond, smooth and calm in the gentle breeze, I toss a stone into the depths. The ripples take their own course, and can never be stopped.

Crossing a small stream, I walk up a gentle slope into a narrow arched cathedral of a trail. Sunbeams flicker as I walk under the canopy of leaves, shuffled by the gentle breeze.

In the woods are a lifetime of memories: My mom takes with joy a bouquet of dying dandelions, and my dad takes my first pitch. My brothers and sister bring me confidence and my soul mate brings me purpose. Her huge brown eyes gleam with love and I stop for a moment and take her hand.

I had commissioned her into the service and retired her as a general. All points in between had been a blessing. We shared hopes and dreams and fulfilled most. The photos of our life were photos of inseparable love, and our “selfies” through the years showed growing lines on our faces that favored the smile over the pained. I was grateful for that. Every day a gift; all of life a wonder. How fortunate I had been.

I cup a falling tear from her and place it in my pocket. “One foot in front of the other,” I whisper.

There too, are decades of brothers and sisters who served with me in war and peace and who were everything in life. Among them is my gregarious Tony.

I step toward him to give him a hug. “Get away or I will crush you like a grape,” he says.

“Message received,” I say. “What are you doing here, Tony?”

“Waiting for you. It took you long enough.”

“Sorry,” I say. “If I had known you were waiting, I would have hurried things along.”

“Would not have wanted that,” he says emphatically. “You set your own pace. That was the right thing to do.” He pauses. “Do you remember what I told you that day?”

I know exactly what he is referring to. That day in the Adirondack Mountains when I struggled to find the words to finish my story—our story.

I say, “Like it was yesterday.

“You said I wasn’t to blame, and that I shouldn’t dwell on the past. You said that you took the mission, that I didn’t give it to you. You asked me to make the most of the life I’d been given, and to keep putting one foot in front of the other. Then you asked me to lift up those around me, and to inspire them, and to speak for you, act for you, and laugh for you.

“My life’s been great, Tony. I did the best I could. I wish I could have shared it with you.”

“Ripples in a pond,” he says. “I am at peace with it.”

“You did better than most and not as good as some. You dwelled on the pain of the past, but it was deep. You were at peace, but it was still inside you. You gave value to my life and you put one foot in front of the other. You stayed in the light, and my friend, most importantly, you lifted up those around you and inspired them; and you spoke, acted, and laughed for me. I also felt the tears. I wished they weren’t there, but I understood when they came. I missed you, brother.”

“Ripples in a pond,” I reply.

He nods.

“Lead, Follow, or Get Out of the Way,” he says. “I’ll take lead.”

“Right. OK, I’ll be your wingman.”

He turns and quietly calls over his shoulder, “Heat check.”

“Two,” I respond.

He starts up the hill. A gentle breeze shuffles the leaves and the sunbeams flicker, and I am gone. But always around.

Editors Note: This article first appeared on The War Horse in April 2023, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to their newsletter[image error]

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 5, 2023

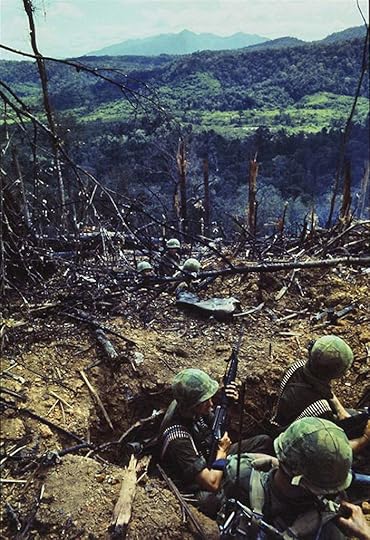

A FIGHT TO REMEMBER: THE 4TH INFANTRY DIVISION AT DAK TO

The legendary elite units, often the focus of battle tales popular with the public, are not the only ones that make vital contributions in combat—as the battle of Dak To shows. The 4th Infantry Division, although often overlooked, made key contributions during that battle. Read more about their involvement:

By DANA BENNER

In accounts of the November 1967 battle of Dak To, one of the largest and longest battles of the Vietnam War, the center of attention is often the elite 503rd Infantry Regiment (Airborne) of the 173rd Airborne Brigade, assigned prior to the battle to the 4th Infantry Division. Seemingly forgotten is the fight waged by the division’s “leg” (non-airborne infantry), engineer, and artillery units.

That’s a sore spot for some veterans who were at Dak To.

“The 173rd were good soldiers and they did their fair share; they certainly did no more than the many other ‘non-elites’ did, like the 4th Division grunts, the artillery and others,” said Steve Stark, an artillery liaison specialist assigned to the 6th Battalion, 29th Field Artillery Regiment, 1st Brigade, at Dak To, in an article by Tim Dyhouse for VFW Magazine.

The 4th Infantry Division—nicknamed the Ivy Division for the pronunciation of the unit’s number in Roman numerals, IV—was led by Maj. Gen. William Peers. It comprised the 1st, 2nd (Mechanized) and 3rd battalions, 8th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Glen Belnap, and the 1st and 3rd battalions, 12th Infantry Regiment, under Lt. Col. John Vollmer. Supporting the missions at Dak To were 15 artillery batteries in the division.

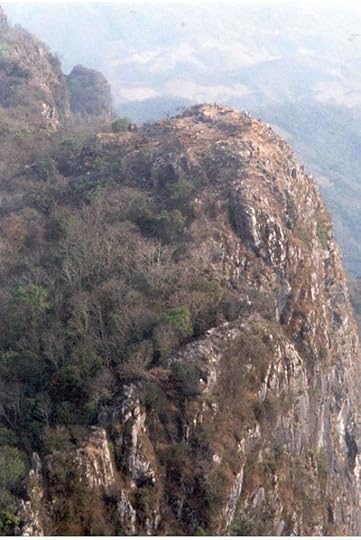

The battle was a collection of fights waged simultaneously against the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong from Nov. 3 to Nov. 23 on several hills near the Central Highlands town of Dak To in Kontum province, close to the point where the borders of Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam meet. In the most high-profile fight, the 173rd Airborne battled for control of Hill 875. However, units of the 4th Infantry Division were the first to make contact with the enemy when they fought the NVA on Nov. 3 and 4 around Hill 1338. (Hills were numbered based on their height in meters.)

The Dak To area, with its thick jungle and steep mountain ridges, was a particularly hellish location for a battle. Tangled thickets of vines and thorns lay in the valleys between the ridges—all of them full of snakes, leeches and enemy fighters.

Within this tangled mess, the North Vietnamese had established a base camp, designated Base Area 609, linked by the Ho Chi Minh Trail to a command center in Hanoi. Countering the communist presence in the area were camps where small contingents of U.S. Special Forces, the Green Berets, trained and assisted militias of local hill tribes organized as Civilian Irregular Defense Groups. These CIDG camps were constantly attacked by NVA and Viet Cong forces.

The 4th Infantry Division had overall command of Kontum province and Pleiku province to the south as well as the northern portion of Darlac, the province below Pleiku. Spread over such a large territory, the division could send to Kontum province only one mechanized battalion (a unit that transports infantry to the battlefield in armored tracked vehicles): the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry (Mechanized).

Communist Gen. Nguyen Chi Thanh developed the strategy used by the North Vietnamese at Dak To. / Alamy

Communist Gen. Nguyen Chi Thanh developed the strategy used by the North Vietnamese at Dak To. / AlamyTo get to Dak To from Pleiku city, U.S. troops followed Route 14 north through Kontum city and then turned west on Route 512.

“North of Dak To, Route 14 rapidly deteriorated as it approached a CIDG camp at Dak Seang,” wrote Allay Sandstrum in “Three Companies at Dak To,” a chapter in Seven Firefights in Vietnam.

“Still farther to the north, the road became so poor that another camp at Dak Pak had to rely solely on an aerial lifeline.”

The NVA’s objective was simple: Sweep all American forces and Army of the Republic of Vietnam troops from the Central Highlands. If the North Vietnamese succeeded, they would have a clear path into South Vietnam for attacks on cities and U.S.-ARVN military installations as part of a planned Tet Offensive in early 1968 that the communists hoped would deliver devastating blows all across the country.

Under a strategy developed by Gen. Nguyen Chi Thanh, the NVA would first isolate and destroy brigade-size or smaller American units positioned at or near Dak To. Those engagements, Thanh believed, would slowly drain the strength of U.S. forces and compel American commanders to send in reinforcements from other areas, thus weakening the defenses in the locations they left and creating more openings for communist troops during the Tet Offensive.

To implement that strategy, the NVA planned to deploy its 24th, 32nd, 66th and 174th regiments from the NVA 1st Division, a total of about 6,000 men. Those units would use “hit and run” tactics, basically running in from Cambodia and Laos to do as much damage as possible and then retreat back across the border, out of range of American firepower.

The North Vietnamese forces were under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Hoang Minh Thao and political officer Col. Tran The Mon.

By the end of October 1967, bits and pieces of information trickling into U.S. officials from the CIDG camps and reconnaissance patrols indicated the communists were preparing for something. Intelligence sources revealed that the NVA’s 1st Division was moving the bulk of its forces from the Cambodian border and remote locations in the Central Highlands toward Kontum province. This large-scale transfer of troops forced the Americans to counter the NVA’s move, like playing a deadly game of chess.

On Oct. 28, the 4th Infantry Division replaced its mechanized battalion with the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, using foot soldiers to more effectively locate the enemy. Long-range reconnaissance patrols reported enemy movement toward Dak To from the southwest.

The 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division, commanded by Col. Richard Johnson, moved its headquarters to Dak To, closer to the action, and brought in the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment, to strengthen its forces. The recon teams, with the aid of airborne surveillance devices, kept track of enemy movements and spotted recently established base camps loaded up with ammunition caches.

Lt. Gen. William Rosson, commanding general of U.S. forces in the central South Vietnam region, called in the airborne troops of the 4th Battalion, 503rd Infantry, airlifting the men to Dak To from Phu Yen province on the coast. That boosted U.S. strength to three battalions totaling around 4,500 men as of Nov. 1.

As American combat units moved into place, the 4th Infantry Division also brought in Company D, 704th Maintenance Battalion; Company B, 4th Medical Battalion; 1st Platoon, 4th Military Police Company; communications personnel from the 124th Signal Battalion and an attached engineer platoon from the 299th Engineer Battalion. All of the elements for sustained combat were in place. The only thing missing was up-to-date intelligence on enemy activities.

Good fortune shone upon U.S. forces when a North Vietnamese sergeant in the 66th Regiment, Vu Hong, surrendered in the village of Bak Ri, near Route 512, north of Dak To. Hong said his 50-man unit had been selecting firing positions for mortars and 122 mm rocket launchers. He also said five regiments were converging on Dak To and the CIDG camp at Ben Het, just west of Dak To.

The plan, as Hong relayed it, called for a southwest to northeast attack. The NVA 32nd and 66th regiments, with the support of the NVA 40th Artillery Regiment, were to spearhead the assault. The NVA 66th Regiment was southwest of Dak To, and the 32nd Regiment moved from the southwest to Dak To to prevent an American counterattack that could come from the base. The NVA 24th Regiment would set up northeast of Dak To, in Tan Canh, and act as a blocking force to prevent American forces from escaping. The 174th Regiment was to stand by as a reserve unit.

With the new intelligence in hand, Lt. Col. James Johnson, commander of the 4th Battalion, 503rd Infantry, ordered his men to set up a firebase at the Ben Het CIDG camp. The NVA, perhaps surprised by the fast response of U.S. forces, pulled back to defensive positions and waited. The NVA 66th Regiment moved to high ground southwest of Ben Het. Johnson, seeing an opportunity to stop the NVA in its tracks, moved the 503rd Infantry to meet the enemy. Holding the high ground, the North Vietnamese waited.

At the same time Belnap, the commander of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, sent companies B and C to the southwest, and Vollmer, leading the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry, deployed his A and B companies, which were airlifted to Ngok Ring Rua Mountain south of Dak To. The 12th Infantry Battalion would set up a firebase, and the 8th Infantry Battalion was to establish a position along the trail to the Dak Hodrain River Valley and stop the flow of enemy traffic to that area.

The Americans intended to launch an offensive strike on the North Vietnamese before the enemy troops could fully dig in for their offensive. Units of the two 4th Infantry Division battalions initiated contact, in separate encounters, with troops of the NVA 32nd Regiment on Nov. 3 and 4 just south of the Dak To CIDG camp.

Thanks to artillery and air support, U.S. casualties were relatively light. Companies B and C of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, got into position along the main trail to the Dak Hodrain River Valley with no resistance. They quickly moved to establish a patrol base for search-and-destroy missions on Hill 785.

On the morning of Nov. 4, while moving toward Hill 882, Company A, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, came under automatic weapons fire from an enemy platoon. Taking defensive positions, the Company A soldiers returned fire, pinning down the enemy. At the same time artillery and airstrikes were called in, eliminating the threat. On Nov. 5 companies A and D, 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, swept Hill 882, with no further direct contact. However, as the Americans approached Hill 843, they came under fire from communist B-40 rockets and 60 mm mortars.

Arriving on Hill 843, the two companies dug in. Throughout the night and early morning of Nov. 7 and 8, the NVA fired rockets and mortar rounds into the American position. On the morning of Nov. 8, Company A moved to take Hill 724, while Company D remained in place to secure the position at Hill 843.

When Company A neared a small knoll, the North Vietnamese opened up with machine guns and automatic rifle fire, pinning the Americans in place—a bad situation that worsened when the NVA sent rockets and 82 mm mortar fire into the position.

Company A was reinforced by Company D, which moved north to flank the enemy. The NVA turned its fire toward the new threat, pinning down the arriving company but allowing Company A to break contact and maneuver to aid Company D. Under heavy automatic fire accompanied by continuous rocket and mortar attacks, the two companies linked up and slowly moved forward. In the afternoon of Nov. 8, they made a final rush, took the knoll and dug in.

At 8 p.m., the NVA attempted to take the knoll back. A fierce battle ensued, with the NVA infantrymen again supported by rockets and mortars. The North Vietnamese breached the American perimeter but were pushed back by the combined efforts of the defenders, as well as artillery and airstrikes. One of the airstrikes, called in by an Air Force strike coordinator embedded with the two infantry companies, hit within 50 feet of the companies’ positions. By late evening the enemy’s attack ceased, though constant suppressive fire lasted through the night.

The two American companies suffered 21 soldiers killed and 81 wounded.

Company A, which had borne the brunt of the fighting, was pulled out on Nov. 10 and replaced by companies B and C of the 8th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion. Early on Nov. 11, Company B secured a landing zone for medevacs, while Companies C and D resumed the battalion’s fight to seize Hill 724. The hill was taken without any major contact.

Company B moved out to join the other two companies. As it neared the perimeter of companies C and D, the NVA, lying in wait, launched a fierce attack. Rockets and mortar rounds rained down on the perimeter as waves of North Vietnamese fighters hurled themselves at the American defenders, engaging all three companies. The weary Americans called in artillery and air support, which drove back the NVA. The battle lasted two hours. It was later determined that Companies B, C and D of the 3rd Battalion, with the aid of artillery and air support, had beaten back two battalions of the 32nd NVA Regiment. When the shooting stopped, the 8th Infantry had suffered 18 killed and 118 wounded.

While the 8th Infantry was fighting running battles near the Dak Hodrain River Valley, the 12th Infantry troops were busy in the Ngok Ring Rua Mountains where they were airlifted on Nov. 3.

At 3:52 p.m., on Nov. 3, the 12th Infantry’s Company B, 3rd Battalion, ran into an NVA platoon firing from an extensive bunker and trench system laid along a trail. The American infantrymen needed to breach the NVA bunker defenses so they could set up a firebase that would be used for an attack on nearby hills.

After getting a fix on the enemy position, Company B broke contact and called in artillery support from the 4th Infantry Division’s Battery B, 6th Battalion, 29th Field Artillery.

After the artillery peppered the area with 105 mm shells, Company B moved forward. Its troops were soon greeted by B-40 rockets and 60 mm mortar fire. The company pulled back and again called in artillery and air support, which was supplied by 40 aircraft.

Early in the morning of Nov. 4, Company B’s 3rd Platoon attempted to knock out the bunker. Suddenly the platoon was attacked, cut off from the rest of the company and pinned down with rocket and mortar fire. After heavy fighting, two squads from 1st Platoon fought their way to their entrapped colleagues. At 2 p.m., 3rd Platoon was able to link up with the rest of Company B. Artillery and airstrikes were called in again. The bombardment knocked out the bunker, and on Nov. 5, Company B was finally able to move forward and secure the position.

From Nov. 6 to 14, the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry, fought to clear enemy positions on the hills of the Ngok Kon Kring Ridge, which overlooked the Dak To base. In attacks on hills 1124, 1089 and 1021 the battalion found heavily fortified bunkers and trench complexes, an indication the enemy intended to stay. The Americans were repeatedly hit with fire from machine guns, B-40 rockets and 60 mm mortars. Despite heavy fighting, the hills were taken.

On Nov. 16, Companies A and C of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry, advanced on Hill 1338. Running into a heavily entrenched NVA force firing rockets and mortars, they called for artillery and air support. Artillery shelling and surgical strikes from U.S. Air Force fighter-bombers pounded the target throughout the night. On the morning of Nov. 17, Company C attempted another advance and was again met with intense fire, despite the heavy bombardment of the previous night.

While Company C continued its slow advance, Company A positioned itself to the southwest and established a firebase. Hill 1338 was finally taken and secured as darkness fell. A search of the area on Nov. 18 revealed that the two companies had fought their way through an extensive defensive system of trench lines, bunkers and firing positions.

The 3rd Battalion turned its attention to hills 1262 and 1245 in battles waged Nov. 19-21. As the Americans pressed ahead, the enemy began a withdrawal but continued to fight intense delaying battles. Despite heavy fighting, the Americans were able to clear and secure Ngok Kon Kring Ridge.

During these multiple engagements, Army intelligence operatives detected structures that looked like a North Vietnamese headquarters area, just a short distance from the Cambodian border and safe havens on the other side. That area, known as “Dogbone Hill,” was a convenient place to fire mortars and rockets into the American base at Dak To.

The 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, was chosen to attack Dogbone Hill in an operation that consisted of Companies A, C and D, an attached engineer platoon and a small command group.

After Dogbone Hill was blasted by artillery and airstrikes, the 1st Battalion units were helicoptered to the hill, quickly occupied the area and established a fortified defensive position, a speedy accomplishment that brought praise from Peers, the 4th Infantry Division commander.

The withdrawing North Vietnamese were moving west toward Cambodia, U.S. intelligence reported. The 4th Infantry Division command countered with moves to thwart the escape. On Nov. 14, B and C Companies of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, established a position on Hill 762 to block an NVA exit through the Dak Sir Valley, south of Dak To.

On Nov. 15, companies B and D of the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry, established a position on Hill 530. The American occupation of hills 762 and 530 put a blocking force at the intersection of three key escape routes leading to Cambodia: the Dak Hodrai, Dak Sir and Dak Romao valleys, all south/southwest of Dak To.

Those American-held hills were used to conduct extensive search-and-destroy operations, but there were few contacts with the enemy. Were the NVA forces hiding or had they managed to escape?

The answer came on Nov. 17 when the NVA assaulted the 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry, firebase on Dogbone Hill. The North Vietnamese hit the base with fire from automatic weapons, 82 mm mortars and 122 mm rockets. This NVA attempt to break free from the trap set by American positions on the hills surrounding Dak To lasted 10 days. In that time more than 500 enemy rounds landed on or around Dogbone Hill. On Nov. 19, a Company C patrol attacked the retreating enemy. The NVA disengaged and fled the area. An inspection of the site revealed a large number of weapons and more than 2 tons of rice.

All of the American objectives were achieved, but at what cost? The Battle of Dak To claimed 376 Americans killed and 1,441 wounded. Of the 3,200 paratroopers deployed by the 173rd Airborne 27 percent were either killed (208) or wounded (645), with the rifle companies suffering 90 percent of the unit’s casualties.

The heavy combat throughout November strained not only the fighting forces of the 4th Infantry Division but also the doctors and nurses in the division’s 4th Medical Battalion. The medical staff in the field treated about 1,200 wounded American and ARVN soldiers during the weeks of continuous battle and managed to keep them alive while waiting for the evacuation helicopters to arrive.

“Every wounded soldier reached the 71st Evac Hospital at Pleiku alive,” stated William J. Shaffer, executive officer of Company B, 4th Medical Battalion, in Dyhouse’s article for VFW Magazine.

The legendary elite units, often the focus of battle tales popular with the public, are not the only ones that make vital contributions in combat—as the battle of Dak To shows.

Dana Benner holds a master’s degree in heritage studies. He teaches history, political science and sociology at the university level. Benner served more than 10 years in the U.S. Army. He lives in Manchester, New Hampshire.

This article appeared in the October 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine: https://www.historynet.com/dak-to-4th-infantry/?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=fb_vtm&fbclid=IwAR1qjfaQw0J3TIZLYLWXXWuc9KZ4v7xB49Tohb3vPglLhiu2x-HNTVcC4kM

Video/Song by Big & Rich depicting the battle of Dak To:

To read more about the Dak To battles on my website, click below for two more articles:

Invisible Enemy: Battle of Dak To

https://cherrieswriter.com/2017/01/03/12-major-battles-of-the-vietnam-war/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 3, 2023

30 Best Vietnam War Blogs and Websites

Jul 31, 2023

The best Vietnam War blogs from thousands of blogs on the web and ranked by traffic, social media followers & freshness.

Here are the 30 Best Vietnam War Blogs you should follow in 2023

1. Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund is the nonprofit organization that founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1982. VVMF’s mission is to honor and preserve the legacy of service in America and educate all generations about the impact of the Vietnam War and its era. Get deeper insights into the Vietnam War and the veterans in the blog.

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund is the nonprofit organization that founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1982. VVMF’s mission is to honor and preserve the legacy of service in America and educate all generations about the impact of the Vietnam War and its era. Get deeper insights into the Vietnam War and the veterans in the blog.

Explore informative articles about artifacts in our permanent collection, topics & subjects related to military history, and Commonwealth connections. The Pennsylvania Military Museum is a community gathering place dedicated to exploring and showcasing Men & Women of Pennsylvania’s contributions to military innovation.

Explore informative articles about artifacts in our permanent collection, topics & subjects related to military history, and Commonwealth connections. The Pennsylvania Military Museum is a community gathering place dedicated to exploring and showcasing Men & Women of Pennsylvania’s contributions to military innovation.

Sons and Daughters In Touch is an all-volunteer non-profit organization committed to ‘locating, uniting, and supporting’ the now-grown children of American servicemen who perished during the Vietnam War. Here you will find all their latest announcements, event reports, and official news updates.

Sons and Daughters In Touch is an all-volunteer non-profit organization committed to ‘locating, uniting, and supporting’ the now-grown children of American servicemen who perished during the Vietnam War. Here you will find all their latest announcements, event reports, and official news updates.

The Waging Peace in Vietnam exhibit and its companion book show how the GI movement unfolded, from the numerous anti-war coffeehouses springing up outside military bases, to the hundreds of GI newspapers giving an independent voice to active soldiers, to the stockade revolts and the strikes and near-mutinies on naval vessels and in the air force.

The Waging Peace in Vietnam exhibit and its companion book show how the GI movement unfolded, from the numerous anti-war coffeehouses springing up outside military bases, to the hundreds of GI newspapers giving an independent voice to active soldiers, to the stockade revolts and the strikes and near-mutinies on naval vessels and in the air force.

Read blog entries written by Joe Campolo, Jr., author of The Kansas NCO Trilogy. A Vietnam War Veteran, Joe writes about the war and his many experiences including War stories, Fishing stories, sharing Rare photos & Press clippings. The blog also features guest writers from time to time presenting their unique experiences.

Read blog entries written by Joe Campolo, Jr., author of The Kansas NCO Trilogy. A Vietnam War Veteran, Joe writes about the war and his many experiences including War stories, Fishing stories, sharing Rare photos & Press clippings. The blog also features guest writers from time to time presenting their unique experiences.

The website is of the HISTORY channel, a cable television channel that broadcasts historical documentaries and reality shows. The website features a wide variety of content, including articles, videos, timelines, interactive maps, and quizzes. It also offers a streaming service that allows users to watch full episodes of HISTORY shows. The Vietnam War lasted about 40 years and involved several countries. Learn about Vietnam War protests, the Tet Offensive, the My Lai Massacre, the Pentagon Papers, and more.

The website is of the HISTORY channel, a cable television channel that broadcasts historical documentaries and reality shows. The website features a wide variety of content, including articles, videos, timelines, interactive maps, and quizzes. It also offers a streaming service that allows users to watch full episodes of HISTORY shows. The Vietnam War lasted about 40 years and involved several countries. Learn about Vietnam War protests, the Tet Offensive, the My Lai Massacre, the Pentagon Papers, and more.

POLITICO is the global authority on the intersection of politics, policy, and power. It is the most robust news operation and information service in the world specializing in politics and policy, which informs the most influential audience in the world with insight, edge, and authority. Read the latest news, headlines, analysis, photos, and videos on Vietnam War.

POLITICO is the global authority on the intersection of politics, policy, and power. It is the most robust news operation and information service in the world specializing in politics and policy, which informs the most influential audience in the world with insight, edge, and authority. Read the latest news, headlines, analysis, photos, and videos on Vietnam War.

Folklife Today is a blog for people interested in folklore, folklife, and oral history. We feature brief articles on folklife topics, highlighting the unparalleled collections of the Library of Congress. These collections include songs, stories, traditional arts, cultural expressions, and oral histories of people from all over the country and the world.

Folklife Today is a blog for people interested in folklore, folklife, and oral history. We feature brief articles on folklife topics, highlighting the unparalleled collections of the Library of Congress. These collections include songs, stories, traditional arts, cultural expressions, and oral histories of people from all over the country and the world.

At Atlas Obscura, our mission is to inspire wonder and curiosity about the incredible world we all share. We are a global community of explorers, who have together created a comprehensive database of the world’s most wondrous places and foods. The Vietnam War category on Atlas Obscura features a variety of sites related to the war. Learn more about the ‘Vietnam War’ on Atlas Obscura.

At Atlas Obscura, our mission is to inspire wonder and curiosity about the incredible world we all share. We are a global community of explorers, who have together created a comprehensive database of the world’s most wondrous places and foods. The Vietnam War category on Atlas Obscura features a variety of sites related to the war. Learn more about the ‘Vietnam War’ on Atlas Obscura.

News and Information from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Read more on the stories, celebrations interviews, and other activities undertaken by the U.S Department of Veteran Affairs on the account of National Vietnam War Veterans Day here. Stay tuned for even more inspiring events.

News and Information from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Read more on the stories, celebrations interviews, and other activities undertaken by the U.S Department of Veteran Affairs on the account of National Vietnam War Veterans Day here. Stay tuned for even more inspiring events.

Together We Served is the largest U.S. Military Veteran website where Veterans reconnect with those they served with and create a record of their military service. The aim is to reconnect servicemen and women with those they served with and provide a secure and familiar online environment for Members to share in the camaraderie of others who served. Read stories about heroes of the Vietnam War in the blog.

Together We Served is the largest U.S. Military Veteran website where Veterans reconnect with those they served with and create a record of their military service. The aim is to reconnect servicemen and women with those they served with and provide a secure and familiar online environment for Members to share in the camaraderie of others who served. Read stories about heroes of the Vietnam War in the blog.

The Unwritten Record is the National Archives and Records Administration’s blog dedicated to special media holdings. The blog features information on fascinating finds, new accessions, preservation projects, and rediscoveries across the agency’s non-textual holdings.

The Unwritten Record is the National Archives and Records Administration’s blog dedicated to special media holdings. The blog features information on fascinating finds, new accessions, preservation projects, and rediscoveries across the agency’s non-textual holdings.

The Hill is a top US political website, read by the White House and more lawmakers than any other site — vital for policy, politics, and election campaigns. Get the latest Vietnam War news brought to you by the team at The Hill.

The Hill is a top US political website, read by the White House and more lawmakers than any other site — vital for policy, politics, and election campaigns. Get the latest Vietnam War news brought to you by the team at The Hill.

John is a published author of six books, three of which chronicle his experiences as an infantry soldier in Vietnam during 1970 / 1971. In this blog, you’ll find over 500 Vietnam War-related personal narratives, photos, videos, movies, artwork, war book reviews, and favorite music of the time.

John is a published author of six books, three of which chronicle his experiences as an infantry soldier in Vietnam during 1970 / 1971. In this blog, you’ll find over 500 Vietnam War-related personal narratives, photos, videos, movies, artwork, war book reviews, and favorite music of the time.

Founded by Tara Ross, a retired lawyer and a former Editor-in-Chief of the Texas Review of Law & Politics. Read about her research and view on various subjects related to the Vietnam War, she has also talked about various martyrs, brave soldiers and more in the blog.

Founded by Tara Ross, a retired lawyer and a former Editor-in-Chief of the Texas Review of Law & Politics. Read about her research and view on various subjects related to the Vietnam War, she has also talked about various martyrs, brave soldiers and more in the blog.

Read all featured articles on topics pertaining to the Vietnam War in this segment. Discover insightful, piercing commentary that sheds light on forgotten but important aspects of the war. The Vietnamese Magazine is an independent and non-profit online magazine that focuses on Vietnam’s politics.

Read all featured articles on topics pertaining to the Vietnam War in this segment. Discover insightful, piercing commentary that sheds light on forgotten but important aspects of the war. The Vietnamese Magazine is an independent and non-profit online magazine that focuses on Vietnam’s politics.

Process – the blog of the Organization of American Historians, The Journal of American History, and The American Historian – strives to engage professional historians and general readers in a better understanding of U.S. history. On the following page, you can read articles and stories about the Vietnam War.

Process – the blog of the Organization of American Historians, The Journal of American History, and The American Historian – strives to engage professional historians and general readers in a better understanding of U.S. history. On the following page, you can read articles and stories about the Vietnam War.

Fold3® provides convenient access to military records, including the stories, photos, and personal documents of the men and women who served. The records at Fold3 help you discover and share stories about these everyday heroes, forgotten soldiers, and the families that supported them. Stay updated and read about the war records, stories, photos, and more on Vietnam War here.

Fold3® provides convenient access to military records, including the stories, photos, and personal documents of the men and women who served. The records at Fold3 help you discover and share stories about these everyday heroes, forgotten soldiers, and the families that supported them. Stay updated and read about the war records, stories, photos, and more on Vietnam War here.