John Podlaski's Blog, page 7

September 11, 2024

“SO FREEDOM WILL LAST “

By Les Davenport·

Away from home, in a faraway land.

His duty has called him…he knows the command.

To say he’s not afraid..would just be a lie.

But for the love of his country, he’s willing to die.

He remembers his family, the laughter the joy.

He remembers the school days, when only a boy.

But being a soldier, he walks a new road.

He weathers the bad times, the rain and the cold.

Oh it isn’t for money to do such a task. Then why would he do it, the critics will ask.

Yet we see the flag flying, meaning liberty to all.

But Freedom isn’t cheap…for many will fall.

Like those before him, in wars of the past…he asks not for glory. But that Freedom will last

So what can we do for this Freedom to stay?

Let’s call on the brethren..they know how to pray.

Say “Father in Heaven ” We’re calling on you…you have all the answers. You know what to do.

Our young men are dying…..as those in the past.

God bless our dear soldiers….SO FREEDOM WILL LAST.

Les Davenport 2012

September 8, 2024

This ‘Puerto Rican Rambo’ Went On 200 Combat Missions in Vietnam

Otero Barreto survived five tours in Vietnam between 1961 and 1970. During that time, he volunteered for 200 combat missions and earned 38 total commendations, including three Silver Stars, five Purple Hearts, five Bronze Stars, five Air Medals, and four Army Commendation Medals. Read his story here:

By Jon Simkins Military Times

Eloy Otero-Bruno and Crispina Barreto-Torres welcomed a son into the world on April 7, 1937, in the small municipality of Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, just west of the island’s capital of San Juan.

When they gave him a name inspired by his father’s admiration for America’s first president, the family certainly had no inkling that little Jorge would one day be something of an American icon in his own right, a status earned after becoming one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War.

Jorge Otero Barreto joined the Army in 1959 after pursuing biology studies in college. Less than two years later, he embarked on his first deployment, one of five such tours he would make to the embattled nation between 1961 and 1970 as a member of the 101st Airborne, 82nd Airborne, and 25th Infantry Division, among others.

Over the course of five deployments, Otero Barreto volunteered for approximately 200 combat missions — a lofty number that eventually earned him the moniker “The Puerto Rican Rambo,” after the fictional death-dealing character made famous by actor Sylvester Stallone.

One particular award was the result of actions on May 1, 1968, when the platoon sergeant, along with men from the 101st Airborne Division, nestled into positions designed to pin down a North Vietnamese regiment in a village near the deadly city of Hue.

In the early morning hours, Otero Barreto and his men came under a heavy bombardment and faced waves of charging enemy soldiers desperate to rid themselves of the incoming Americans.

U.S. troops managed to repel the first two enemy assaults, killing 58 in the process and forcing the assailants to limp back to the village.

Instead of awaiting a third assault, Otero Barreto opted to lead a counter-attack. But shortly into their advance, the first platoon came under a barrage of machine guns, small arms, and rocket-propelled grenade fire from enemy spider holes and bunkers strewn across the platoon’s fire sector.

The Puerto Rican Rambo wasted no time getting to work.

Otero Barreto sprinted to the nearest machine gun bunker and quickly killed the three men manning the position.

Gathering the rest of his squad, he moved through three more fortified enemy bunkers, dashing from one to the next until all that remained was a trail of destruction.

The assault by Otero Barreto, which allowed the rest of Company A’s platoons to maneuver into advantageous positions and overrun the enemy, would earn him one of his three Silver Stars.

Otero Barreto, now 85, would later retire as an E-7 (sergeant first-class). And while the eventual conclusion of Vietnam would mark the end of his extensive combat career, it would not be the last of his many lifetime achievements.

In 2006, Otero Barreto was named the National Puerto Rican Coalition’s Lifetime Achievement Award recipient. Since then, veterans’ homes and museums have been named in his honor, and in 2011, the city of his hometown recognized him when it named the Puerto Rican Rambo its citizen of the year.

Read more about Otero Barreto via one of his Silver Star citations here:

https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/113830

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 1, 2024

Native Americans in the Vietnam War

T. C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa, 1946–1978), On Drinkin’ Beer in Vietnam, 1971. Lithograph on paper, 48 × 76 cm. Collection of Museum of Contemporary Native Art.

This print depicts the artist and his friend from home, Kirby Feathers (Ponca), at a Vietnamese bar. Though stationed just miles apart, they only met once in Vietnam. Cannon was conflicted by his service; a mushroom cloud—a symbol of that conflict—appears in the background. Cannon was a member of the Kiowa Ton-Kon-Gah, or Black Leggings Warrior Society.

Approximately 42,000 American Indians—one of four eligible Native people compared to about one of twelve non-Natives—served in the armed forces during the war in Vietnam (1964–1975). Many were drafted, but many volunteered, often citing family and tribal traditions of service as a reason.

Native Americans served valiantly in the Vietnam War as they have in all of the United States’ conflicts.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Department of Defense did not keep records on the numbers of Native Americans who served in the armed forces, but scholars estimate that as many as 42,000 Native Americans served in the Vietnam War. Unrecognized by the Department of Defense or service branches, these Native American servicepeople were sometimes mislabeled as whites, Latinos, or even Mongolians. Although exact numbers are impossible to verify, some studies find that Native Americans were more likely to serve in combat units. One assessment of 170 Native Vietnam veterans found that 41.8 percent of those surveyed served in infantry units, while nearly another quarter served in airborne or artillery units. Several sources insist that 232 Native Americans died in the Vietnam War and are listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC.

Courtesy of Harvey Pratt

Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho, b. 1941) holds a Naga knife—a Southeast Asian knife used for cutting through vegetation—during the camouflage and evasion portion of ambush training for his service in Vietnam in 1963.

Motives for Service

Native Americans enlisted or accepted induction into the military during the Vietnam War for a variety of reasons. Patriotism and concern for democracy’s survival in the Cold War inspired many Native Americans in the same ways that these motivations affected members of all races and ethnicities in the United States. Other sources of inspiration may have been more specific to Native communities’ traditions and cultures. Historically, in Native societies, most men share the collective responsibility of protecting the tribe or community from outside aggression. Native American beliefs commonly insist that military service and the experience of combat steels young men, transforming them into future leaders. Proximity to danger, violence, and death, these traditional views maintain and implant wisdom, acumen, and respect in those who pass the test of combat. Furthermore, in some Native communities, traditional practices require that men demonstrate martial and religious prowess to be considered full-fledged members of the nation.

During the Vietnam War, young Native Americans surely heard stories of their fathers’ and grandfathers’ service in the world wars and Korea, and they viewed the conflict in Southeast Asia as their opportunity to demonstrate prowess and earn the esteem of their elders and peers. Moreover, some Native societies traditionally afforded young, unmarried men little social prestige within the tribal community. For young men in these environments, military service offered an opportunity to escape their hometown and return as an independent and mature member of the tribe or community.

Potawatomi Traveling Times

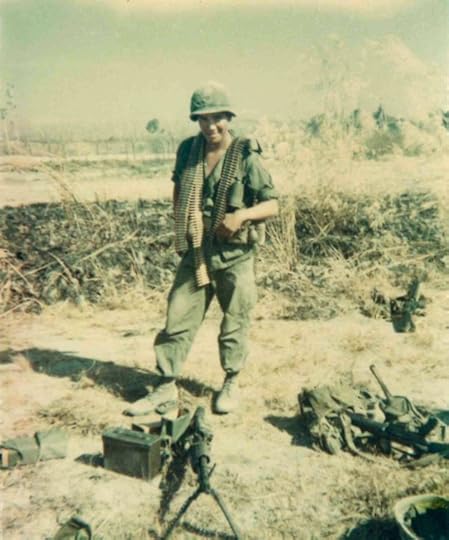

Ernie Wensaut (Forest County Potawatomi, b. ca. 1945) checking his gear before a patrol mission near the Cambodian border in the highlands of Vietnam in March 1967. A member of Company C, 2nd Battalion, 10th Infantry, 1st Division (also known as the “Big Red One”), Wensaut was an M-60 machine gunner whose weapon, nicknamed “The Pig,” fired 500 to 600 rounds per minute.

Additionally, some Native Americans may have enlisted or accepted induction because they believed they owed service to the United States due to treaties that their nations had concluded with the Federal Government in the past. These individuals likely acknowledged that the United States repeatedly broke its treaty promises with Indian nations, but members of these nations may have remained committed to upholding the alliances their ancestors had made with the United States. Lastly, there surely were some Native Americans who volunteered for military service during the Vietnam War to escape poverty and the lack of opportunities in the cities, small towns, and Indian Reservations where they lived.

“Indian Scout Syndrome”

In Vietnam, Native American servicepeople faced racist attitudes held by non-Native officers and enlisted men. Some scholars have labeled this prejudice “Indian Scout Syndrome.” This racist caricature, which existed long before the Vietnam War, assumed that Native Americans possessed superior senses and an instinctive understanding of nature. Therefore, all Indians were natural scouts, trackers, or snipers. This stereotype sometimes led to higher numbers of Native Americans being assigned to the most dangerous duties in combat units, such as having to “walk point” or go on reconnaissance patrols. Some Native Americans embraced this warrior image and volunteered for the most dangerous missions.

Sergeant Billy Walkabout, a Cherokee from Oklahoma who served as an Army Ranger with the 101st Airborne Division, was the most decorated Native American serviceman in the Vietnam War. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroic combat actions outside of Hue in November 1968. Although numerous Native Americans, such as Walkabout, took pride in the warrior ethos, many Native Americans likely fell victim to a different type of discrimination.

Accounts from Vietnam reveal that some officers assigned Native Americans to the most mundane and menial tasks as a result of stereotypes that regarded Indians as untrustworthy, lazy, or stupid. Anxieties prompted by cultural and racial differences between the Americans and Vietnamese even found their way into the Vietnam-era parlance used by service people. Firebases were colloquially known as “Fort Apaches,” and former Communists who chose to collaborate with the South Vietnamese or Americans were “Kit Carson Scouts.” The phrase “Indian Country” referred to remote areas in the Vietnamese jungles and mountains infested with the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese. Patrols in “Indian Country” likely meant ambushes and booby traps, and since these encounters happened far from urban areas, media reporters, and high-ranking officers, the normal rules of engagement sometimes were believed to be suspended.

In one study, some Native American veterans expressed dismay that atrocities they had witnessed in Vietnam’s “Indian Country” mirrored crimes the United States government had committed against their own people. To some observers, the war in Southeast Asia resembled a foreign invasion in which outside militaries targeted civilians, stole land, and resettled survivors in refugee camps. Meanwhile, some Native servicepeople expressed sympathy for indigenous Montagnard peoples, who wished to maintain their independence, practice their traditional lifestyles, and remain outside of the conflict. Native American cultures often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat

Native American societies often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat.

Cultural Attitudes and Practices in War

These practices existed long before the 1960s—there are accounts of similar rituals during World Wars I and II—but Native Americans continued these traditions during and after the Vietnam War. Numerous nations require veterans to perform ceremonial and religious functions at powwows and tribal gatherings. In many cases, older males count coups or recount stories of martial prowess to reinforce tribal solidarity, language, history, and identification with the homeland. Other ceremonies mark the transition from war to peace and vice versa. The Navajo, for example, have been known to perform a dance ceremony called the “Enemy Way” for members of the tribe on their departure and return from war. This ceremony reenacts a traditional story as a means of suspending the rules prohibiting violence before the warrior departs, and it restores the rules of peacetime upon the warrior’s return. Navajos and Cherokees employ similar ceremonies intended to exorcise the demons of war from those reentering the peaceful community. In other nations, medicine men or shamans perform rituals to help individuals heal the scars of combat or protect loved ones at the front. Elders and parents often provide gifts and tobacco and say prayers to ensure protective medicine watches over warriors when they are away. Although servicepeople in the Vietnam War departed and returned at different times, evidence suggests that Native American communities continued to employ traditional ceremonies throughout this era. The practice of certain rites and traditions may have become more widespread after the war as a result of the hardships suffered by Native service people in Vietnam.

Courtesy Donna Loring

Donna Loring, 1966.

Loring (Penobscot, b. 1948) served in 1967 and 1968 as a communications specialist at Long Binh Post in Vietnam, where she processed casualty reports from throughout Southeast Asia. She was the first female police academy graduate to become a police chief in Maine and served as the Penobscots’ police chief from 1984 to 1990. In 1999, Maine governor Angus King commissioned her to the rank of colonel and appointed her his advisor on women veterans’ affairs.

Native American veterans of the Vietnam War stand in honor as part of the color guard at the Vietnam Veterans War Memorial. November 11, 1990, Washington, D.C. (Photo by Mark Reinstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Coming Home and Recovery

Several studies have found that Native Americans suffered from the physical and psychological traumas of combat at higher rates than other servicemembers following the Vietnam War. Poor employment prospects on reservations and in rural areas, combined with inadequate access to medical and psychological care, exacerbated the problems many Native veterans faced. A widespread reluctance to speak with outsiders or admit to shameful behavior or conduct encouraged some Native American veterans to forego programs designed to help them cope with the traumas of combat. Several sources indicate that alcoholism and substance abuse among Native American Vietnam veterans was widespread, especially during the first two decades following the conflict.

The United States government failed to devote special attention to the plight of Native veterans until the 1980s. Despite these difficulties, the Vietnam War inspired many Native American veterans to reconnect with their cultures and reinvigorate their communities. The war and emergence of social justice movements politicized Native veterans in new ways, and many veterans became active in tribal governments and cultural associations. During the decades following World War II, the Federal Government slowly eliminated many aspects of tribal sovereignty during a process named Termination. The goal of Termination was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society by breaking up the reservations. Native Americans resisted these infringements on their rights by strengthening tribal governments, protesting injustice, battling these policies in courts, and restoring tribal customs, languages, and education. Historians have labeled this period of Native activism the Red Power movement. Many Native activists who took part in the 1970s Red Power movement were Vietnam veterans, including a large number of the American Indian Movement (AIM) protestors who organized the Wounded Knee standoff against federal law enforcement agencies in 1973. This violent occupation and standoff resulted in a 71-day siege and the death of two protestors.

Most Native Vietnam veterans, however, affected positive change through peaceful methods. They took on prominent roles in tribal councils on reservations or became participants in cultural or social justice organizations in towns and cities. Some of the most prominent of these voluntary associations are known as warrior societies, which were established by many nations and tribes throughout the United States and Canada during the 1970s and 1980s. In many nations, such as the Kiowa, Comanche, Lakota, Chippewa, and Cheyenne, certain tribal functions can only be performed by veterans. Vietnam veterans have fulfilled and continue to serve in these leadership roles in the present day.

National Native American Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located at The Highground in Neillsville, Wis.

This post originally appeared on THE UNITED STATES 50TH VIETNAM WAR COMMEMORATION website: https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/assets/1/7/NativeAmerican_Posters_FINAL.pdf

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 25, 2024

PROFILES IN COURAGE: ROBERT L. HOWARD

The last time someone received a second Medal of Honor was in World War I, and it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another two-time recipient in our lifetime. But if anyone were going to come close to receiving multiple Medals of Honor, it would have been U.S. Army Col. Robert L. Howard. During his 54 months of active combat service in Vietnam, he was wounded an astonishing 14 times and received eight Purple Hearts and four Bronze Stars.

He was also nominated for the Medal of Honor three times in 13 months, the only soldier ever to receive three nominations. Two of those were downgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star because his actions took place in Cambodia, where the United States wasn’t technically at war. He would be awarded the medal on his third nomination, forever changing his life and career.

Alabama-born Howard enlisted in the Army in 1956 and would spend the rest of his working life serving his country. Some 36 of those years would be spent in the Army, first as an enlisted Special Forces soldier, then as a Special Forces officer. He was a Staff Sergeant when he was sent to Vietnam as part of the secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) in 1967. It was the first of five tours in Vietnam.

In December 1968, he was on a rescue mission looking for six missing American soldiers. It was a mixed American-South Vietnamese Hatchet Force based in Kon Tum. It was a platoon-sized force that would be inserted by helicopter into the soldiers’ last reported location. As they moved to the landing zone, his force began taking ground fire and casualties. Immediately upon landing, he took three men to secure a perimeter. The incoming fire caused him to fall.

His three men were killed immediately. Two companies of enemy troops completely surrounded the LZ. One of the helicopters had been shot down. They had to fight their way out of the drop zone and made a move for the high ground. Howard pushed his way to the front of the unit, but before he could warn his lieutenant about enemy fire from their flanks, they were ambushed – and had walked right into it.

Howard had been hit by a grenade, his weapon destroyed. When he came to, his platoon was in disarray, and he was left temporarily blinded. When his vision returned, he realized his hands were wounded, and the enemy troops were burning the Americans with a flamethrower. Howard got up and pulled his lieutenant down the hill. As he moved, he acquired a sidearm from an unhurt-friendly soldier just as the North Vietnamese came running out of the bush.

He killed two of the attacking enemy soldiers before he was hit yet again. One of the rounds hit the rifle magazines on his belt, causing them to explode. Out of ammunition, he returned to the landing zone, now a casualty collection point. He ordered that every wounded soldier in the field be treated while every unharmed soldier rallied to his position. In the melee, he’d seen soldiers watching his comrades being shot up by the enemy and not even firing their weapons. He told the men who had watched without fighting that they were going to establish a perimeter and that they were either going to fight or die.

“I want you to get every live person we’ve got that’s able to fight,” he told a wounded medic through gritted teeth. “I want to talk to them right now.”

He located three strobe lights and assembled them in a triangle around their position, got on the radio, and called in an airstrike on their position, hoping the incoming aircraft could avoid hitting the friendlies inside the strobes. They fought for four hours without help before Air Force pilots 20 minutes away volunteered to make a rescue attempt. Before the airmen could arrive, the North Vietnamese made another desperate charge. Howard was forced to order an airstrike on his own position.

The incoming air power was so intense the fire from the assault struck close to his feet. But as the airstrike receded, the sound of helicopters replaced it. The Air Force was able to extract what was left of his platoon. Of the 37 troops who went into the landing zone that day, only six walked out. Howard was the last man on the helicopter, waiting until everyone else had been evacuated first.

For his gallantry and the reorganization of his battered platoon, Robert L. Howard received the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon in a White House ceremony on March 2, 1971. He would become one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War and would serve until 1992. In his post-military career, he would work with veterans in Texas. Howard died on December 23, 2009, and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

This article originally appeared on the Together We Served Website. Here is the direct link:

https://army.togetherweserved.com/army/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=DispatchesArchive&type=NewsArticle&ID=1570*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 17, 2024

FIREFIGHTS AND COURAGE

What goes through an infantry officer’s head during a firefight? Fear and indecision can get everyone killed, a soldier must overcome it and trust in his training. Here’s one platoon leader’s take on it.

By Robin Bartlett

John Wayne, who never served in the military but is revered by all branches of the service, may have said it best: Courage is being scared to death but saddling up anyway.

Courage under fire is something all grunts (infantrymen) thought about in Vietnam. My firefights, as a combat infantry platoon leader, came in a variety of forms: a skirmish with one or two enemy soldiers walking down a trail or a short but ferocious ambush initiated by our own soldiers or the enemy, often resulting in the immediate death of those ambushed. There were times when I was engaged in a firefight during a helicopter combat assault into a hot LZ. My worst firefights were those that occurred at night. This may have been an attack against our dug-in company’s NDP (night defensive perimeter) by an enemy using mortars and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). Night fights meant fear, chaos, and confusion because of the darkness and uncertainty of enemy movement. The enemy were masters of night fighting, and on at least one occasion, we defended our firebase against a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) force. In this battle, “Sappers” would try to penetrate the perimeter wire and throw satchel charges into command bunkers.

A firefight of any type was horrific, with men often wounded or killed. It was my worst nightmare. On patrol in the deep jungle, encountering an enemy force with bullets flying overhead, I found myself pressed to the ground and unable to see more than 5-10 meters in any direction. The experience could be paralyzing and traumatic. My first instinct was to give orders to attack the enemy, but equally important was securing my position and placing men in defensive positions to the front, flanks, and rear to guard against being overrun. The next challenge was calling our Forward Observer (FO) and requesting artillery support when unsure where I was on the ground. The FO had preplanned artillery concentrations marked on my map, but exactly how close I was to those concentrations was always a big question in my mind. I asked that the first shot be a smoke round and listened to where it landed, praying it was not on top of me. Then I gave adjustment instructions to the FO based on where I heard the round land, always adding extra distance to be safe.

When an ambush resulted in wounded soldiers, I knew my men wondered what my priorities would be. Would I give orders to continue an aggressive attack, or would I call for a medevac and make saving lives my top priority? These decisions were critical as my men also thought, “what if I was the next one to be wounded?”

For me, tunnel vision, adrenalin pumping through my body, intense sweating, and the need to make fast decisions while facing the terror of the moment all happened at once. I prayed that the orders I gave would not put my men in harm’s way, get them killed, or further complicate an already perilous situation. Then, suddenly, my training kicked in, and I gave orders, directing my men to move and provide covering fire while my medic and I pulled a wounded man to safety. I called the FO and dropped rounds on the target with devastating explosions while screaming at my men to take cover and keep their heads down.

In the deep jungle, Cobra helicopter gunship support was of no help. They could not find or see us on the ground. Popping smoke would only get hung up in the canopy. So, I told my medic to start working on the wounded man while I called for a medevac, giving coordinates for the best estimate of where I was. For me, sometimes, contrary to how platoon leaders were taught, the first priority was always taking care of severely wounded men in danger of bleeding out.

We chopped down trees to open a hole in the canopy. When we heard the medevac circling the area, I spoke with the pilot on the radio and fired a star cluster, like a Roman Candle, through the hole in the canopy, praying the pilot or door gunners would spot us. We tied a smoke grenade to the end of a long pole, popped it, and held it high over the hole in hopes the chopper would spot the colored smoke and come in to hover.

The medevac came in fast and dropped a jungle penetrator (steel cable with a seat at the bottom). The wounded man would sit on the seat and be hauled up. If the man was too gravely wounded, the helicopter would drop a stretcher, and we tied the man into it. Again, the helicopter would swoop in, drop the hook, and haul the man to safety. “Only then could we breathe easier as it was a short flight to the battalion aid station and lifesaving attention.

The dead were dead. They weren’t going anywhere. After the fight, everyone needed to recover from the adrenaline coursing through our bodies, leaving us drained and utterly exhausted. Eventually, I would wrap each of the dead in a poncho and attach a death card to his boot, along with one dog tag. I wrote the man’s name, rank, and serial number on the card and indicated the map coordinates where he had died. Sometimes, we had to carry the dead for miles before we could reach the open ground where a helicopter could land. The incoming helicopter brought water, ammunition, C-rations, and we loaded the dead onboard for their long trip home. This was the hardest job I had to do as a platoon leader: going through the man’s pockets, securing personal effects, wrapping him in a poncho, and tying cord around his body so it would not come loose in the rotor wash. But this was my job and mine alone.

What I learned about courage in a firefight was to use all the weapons at my disposal and to aggressively attack the enemy position with as much firepower as I could bring to bear. This included our own weapons: M16s, machine guns, and grenade launchers, and calling for added support from artillery and Cobra helicopter gunships. I tried not to take unnecessary risks with my men and gave them what I hoped were orders that were the best I could make. And I gave priority to getting my severely wounded soldiers medevaced from the battlefield as quickly as possible.

There was never a minute that I wasn’t afraid in a firefight, but I reached deep down inside, trusted my training, and found the grit to do what had to be done. Firefights were the worst experiences of my life, and some have stayed with me to this day. I look back on those moments and take comfort in the fact that I did not freeze; I directed my men to attack and kill the enemy without unreasonable risk; and I was usually successful in evacuating my severely wounded men.

In The Duke’s own words: I was scared to death but saddled up anyway!

This article appeared in DISPATCHES, the Summer 2024 Edition, from the MWSA website.

*****

Robin Bartlett has contributed several articles to this website. If you want to read more of his work, go to the top of this page, click on the magnifying glass in the top right corner, then type “Robin Bartlett” and hit enter. A drop-down menu will provide direct links to each article. To return, click on the back arrow at the top left of the page.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

August 9, 2024

July 2, 1967 – A day I’ll never forget

During a routine patrol, his squad was caught in an ambush. He was wounded, and the event might have saved his life. Here’s one instance when volunteering in the military paid dividends. Read what happened.

By Lee Campbell

I arrived in Vietnam in early March 1967 and was assigned to the 2nd platoon, Charlie Company, 4th Battalion, 12th Infantry, 199th Light Infantry Brigade. As an RTO, I carried the PRC-25 radio for the squad leader to communicate with the platoon and company RTOs. I called in our coordinates, popped smoke grenades in LZs to guide resupply and dust off choppers to our locations, and called in our coordinates for artillery fire missions.

On July 2, Charlie Company’s Second Platoon was on the last day of a three-day search and destroy patrol near Bien Hoa, South Vietnam. My job was to follow our squad leader, Sgt. Curtis G. McHendry, who we called Sgt. Mac. We had humped pretty much from shortly after daylight to near dark every day, and we were exhausted. As the platoon set up their NDP (Night Defensive Position), my squad started out for a location about 500 yards away to ambush a trail running adjacent to a wooded section.

When we came upon a deep stream, I volunteered to swim across and secure the ropes on the other side. This stream was about fifteen yards across, and swimming with a rope and boots on was much more difficult than I initially thought. I went under a couple of times and struggled across without drowning. The first guy to cross on the ropes brought my radio.

Once everyone crossed the stream, we found ourselves next to a thick wooded area on our right. We followed it for thirty minutes before coming to an open area and stopped for a short break. We set up a small twenty-foot diameter perimeter, with Edward “Piggy” Miller, our M-60 machine gunner, positioned closest to the wooded area and in the twelve o’clock position. “Piggy” was his nickname, but I always called him Miller. He and I were close friends in Vietnam. Two other guys in our squad carried ammo for the M-60 and dropped next to him. The following two positions were set at a clock’s four and eight o’clock positions. Sgt. Mac and I were together in a spot furthest away from the stream and wooded area and more in the circle’s center.

Edward “Piggy” Miller

The old rice paddy we sat in was dry; a border dike was to our rear, about twenty-five yards away. According to our map, we were only about a half mile from the Company CP on the other side of the large wooded area.

Sgt. Mac was an E-6 staff sergeant who was a good squad leader and a nice guy. I liked him. I just turned twenty-two, Sgt. Mac was closer to thirty but appeared older. The other nine guys were all between nineteen and twenty-two. I remember Daniel Toro, who carried the M-79 grenade launcher, Bernie Ford, Tommy Donahue, and Robert McClamroch, all infantrymen. The remaining four guys were all new; I don’t remember their names. We were all trying to get rid of the leeches we picked up while crossing a second shallower and only knee-deep stream en route to this position. Some, like me, attempted to dry out, rest a little, and eat a dinner of C- Rations before it darkened and we moved to our ambush location. My boots lay on the ground while my wrinkled feet dried in the humid air.

Suddenly, we came under intense fire from the wooded area. Sgt. Mac and I were pinned down, bullets impacting all around us. I immediately knocked my radio on its side and slid it between us and the woods so we had something to hide behind. I had my steel pot helmet on, but Sgt. Mac lost his in the scramble to melt into the ground.

PFC Lee Campbell, RTO

Sgt. Mac immediately took the radio handset to call the Second Platoon Leader, Lt. Gene Krupp, for help but got no response. Then, I tried for several moments but couldn’t reach anybody either. While continuing my efforts, Sgt. Mac was yelling, “Miller, get the machine gun firing.”

There was very little return fire from our squad as everybody remained pinned down for several minutes. The incoming rounds were passing so close to my head that I could smell them burning and heard them crackling as they passed overhead. The sound was like bacon frying in a skillet. I was still calling for help on the radio, and Sgt. Mac was hollering at Miller when an enemy burst hit us both.

Sgt. Mac yelled, “Oh my God, I’m hit, I’m hit.”

I told him I was hit, too!

I was shot through my left elbow. The round went in from the inside and out the back. Sgt. Mac was shot through his right foot. The fire remained intense for some time.

The next thing I remember is hearing the M-60 and the other guys finally returning fire. Several minutes later, and just as suddenly, the enemy fire stopped.

Now that the short skirmish appeared over, I examined my radio and found three direct hits, which explained why we couldn’t reach anybody.

Just then, Daniel Toro crawled over to our position and informed us that Miller was killed in the initial burst. It was Daniel who took over the machine gun and began returning fire. While talking, he assessed our wounds – bandaging my arm and helping Sgt. Mac to remove his boot. Toro’s equipment was hit four times (his steel pot helmet, canteen, the heel of a boot, and gun belt), but he was not wounded.

Sgt. Curtis G. McHendry

Just then, the rest of Second Platoon and our new platoon medic, George Hauer, came crashing through the foliage and into the clearing. This was Hauer’s first combat experience. He went straight to Miller and determined that he had died instantly. Hauer had just replaced Second Platoon medic Jim Rothblatt, who was transferred to the mortar platoon and Company CP, where he was promoted to Senior Medic. A helicopter gunship arrived and fired rockets and mini-guns into the suspected enemy positions. When a medevac helicopter touched down, Toro returned and helped me get Sgt. Mac to the chopper, which landed thirty yards away.

The medic on board helped Sgt. Mac onto the chopper. I shared my supplies, M-16, and ammo with the guys and hopped onto the chopper. It took off, leaving my bullet-riddled boots and radio lying in the field.

Sgt. Mac and I were seated side by side on the helicopter, with Miller’s body lying at our feet. His face was contorted as if he were trying to holler out, a single, bloody hole was centered in his forehead, and his stomach was so swollen that he looked nine months pregnant. It was a short chopper ride to the Tan Son Nhut Airbase. We landed at the heliport, where a Jeep ambulance truck was waiting.

The truck had a medic in the back, who helped get Miller’s body inside and then assisted Sgt. Mac as he climbed in. As I started to step up into the back of the ambulance, the medic motioned me away and closed the door. Thinking that he wanted me to walk around and get in the passenger seat, I started around the right side of the ambulance, and it pulled away.

The round that went through my arm must have severed some nerves because I wasn’t hurting all that bad. The underside of my arm was numb from the elbow through my left hand. Anyway, there I was, standing alone on the helipad with no boots on and my bandage loose and streaming almost to the pavement.

By this time, it was getting dusky dark. I looked around, and there was a building maybe twenty-five yards away. A soldier had exited earlier and was now walking toward me. He was an Air Force Major who had watched everything unfold.

He asked, “Son, weren’t you supposed to be in that ambulance?”

I answered, “Yes, sir, I’m shot and need to get to the hospital.” I raised my arm to show him my blood-soaked bandage.

He said I should wait right where I was and hurried back to the building. Less than five minutes later, a green sedan pulled up. The rear window rolled down, and an Air Force Major General peered out. “Get in the car, son; we’re taking you to the hospital,” he said.

I opened the back door and started to climb in, but hesitated when I saw the general sitting there. He told me to get in the front passenger seat.

All I could think of was how dirty my fatigues were; blood was still leaking from my elbow and dripping onto the leather seat. I felt bad that the driver of the spit-shinned limo had to clean it up after I got out.

The general and I chatted nonstop until arriving at the 3rd Field Hospital in Saigon. The emergency entrance was dark, and no one was around. “Wait here; I’ll be right back,” the general growled.

3rd Field Hospital, Saigon

A minute later, the doors swung open, and four medical staff came running out with a wheelchair and stretcher. The general wished me well before I was rushed inside.

They took me to a curtained-off area to examine my arm and scheduled me for surgery. Then, one of the attendants pulled back the side curtain, and Miller lay there on a gurney.

He asked me if I knew him. When I nodded that I did, he wanted to know all about him. I told them everything I knew. They closed the curtain, which was the last time I saw Miller.

I went to the shower room and stood under the hot water for thirty minutes, my first shower in four months. I had the surgery and slept all the next day and night and woke up the following morning with my arm in traction and a Purple Heart pinned to my pillow. The guy beside me said they tried to wake me but couldn’t.

When the nurse came and took the bandage off, I saw the entrance and exit wounds were stuffed full of bloody gauze; each wound was an oval gash about five inches long and three inches wide. They had to leave the incisions “open” to drain and avoid infection. The next day, they told me they were flying me to Camp Drake in Tokyo, Japan, for a few weeks of therapy. I was happy because it meant I was out of “the field” and Vietnam for a few weeks.

I flew in a hospital plane to Tokyo with my arm still in traction. They scheduled me for surgery to close the wounds. The surgeons used thin strands of twisted wire about an inch apart instead of stitches. After a few days, I was doing o.k., but the therapy was seriously unpleasant.

I was bored and volunteered as a clerk in one of the offices when I wasn’t having therapy. That decision led to an opportunity that may have saved my life. I worked there for a few weeks before I got my orders to return to the 199th Infantry Brigade in Vietnam. The sergeant in charge offered me an opportunity to get my MOS changed from 11B Infantry to 71B Clerk. I took him up on his kind offer. I arrived back at the 199th Brigade Main Base at the end of July.

I was assigned to work as a clerk for the Brigade S-1, Major Edward Kelly III. The S-1 office was still in a tent on a wooden platform and part of “Tent City .” I worked there for a few weeks before moving into the new Brigade Headquarters building, a single-story wooden building on a concrete slab. The Brigade HQ building was connected by a wooden covered ramp to the Tactical Operations Command (TOC) building. The TOC building was heavily sandbagged on all sides and on the roof in case of mortar or rocket attacks. A short time later, Major Kelly was reassigned and named the Executive Officer (XO) for 4th/12th. His replacement, Major John Musser, was my boss for the rest of my tour. Ironically, when the sergeant who worked in S-1 rotated out, his replacement was Sgt. Mac, who had just returned from Japan.

In late January 1968, I only had about six weeks left in-country and was finally beginning to believe I would make it home after all. Then TET happened! We dug in and sandbagged three-man defensive positions at each of the four corners of the Brigade HQ building – “our last line of defense.”

The TET Offensive began in the early morning of January 31, 1968. The North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and the Viet Cong (VC) launched a series of well-coordinated attacks on cities, towns, and large military bases all over South Vietnam. Our 199th base camp came under heavy 122mm rocket, mortar, and crew served weapons fire before waves of Viet Cong and NVA from the 274th & 275th main force regiments attacked the camp. After three days of heavy fighting, we counted over nine hundred enemy bodies around the perimeter.

In early March 1968, I returned to the 90th Replacement Battalion for out-processing and went to Bien Hoa Airbase to catch my flight home. There, I joined hundreds of other celebrating soldiers who also survived their tours in Vietnam.

#####

Lee Campbell lives in Johnson City, Tennessee. He retired as a PGA Golf Professional and is a Life Member of the PGA of America. He was diagnosed with Multiple Myeloma August 1, 2023 and later Plasma Cell Leukemia from exposure to the herbicide Agent Orange in Vietnam (57-years later). He is currently in Cycle-11 of a Chemo Treatment Program at the VA here in Johnson City. In the next couple of months he will be going to the Nashville, TN VA Hospital at Vanderbilt for a Stem Cell Transplant.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 2, 2024

She was America’s first woman POW in Vietnam — and was never found

Dr. Eleanor Ardel Vietti was last seen alive on May 20, 1962. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency)

By Claire Barrett

In the dense jungle terrain in Darlac Province, near the provincial capital of Ban Me Thuot, South Vietnam, American doctor Eleanor Ardel Vietti had found her calling to heal.

Yet that same calling led her to become America’s first female prisoner of war in Vietnam. To this day, Vietti remains the only American woman POW whose fate remains unknown.

According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, 1,244 Americans are still unaccounted for in Vietnam.

Fifty-nine women civilians who worked for U.S. governmental agencies and other various organizations such as the Red Cross and the Peace Corps were killed during the war.

Called to service, Vietti, alongside the Christian and Missionary Alliance and tribal nurses, worked to treat those afflicted with leprosy within South Vietnam’s largest ethnic minority, the Montagnards — a French phrase for “mountain people.”

Within Montagnards communities, the rates of the disease could reach a staggering 30 percent, among the highest in the world.

However, amid escalating tensions between guerrilla factions under Ho Chi Minh and South Vietnamese forces and their foreign advisors, the U.S. State Department cautioned all American expats to leave the country.

Targeted attacks against the Montagnards were also on the rise, but despite that and government warnings, Vietti and other missionaries — notably, Daniel Gerber, a member of the Central Mennonite Committee, and Rev. Archie E. Mitchell — believed they were in no inherent danger and continued their work within the Leprosarium compound.

The night of May 20, 1962, was one of the last nights Vietti and the two men were ever seen alive.

That evening, twelve armed guerrilla fighters descended on the colony, tying up Archie Mitchell and Gerber, and ordering Vietti out of her house. Vietti and the other two captives were bound and taken away. With no ransom demands ever made, it remains unclear why the three prisoners were taken.

Mitchell, incidentally, was the lone survivor of the 1945 Japanese balloon bombing attack off the coast of Oregon that killed his first wife, Eloise, and five neighborhood children. The Japanese strike was the only successful enemy attack on mainland America during World War II.

It seems likely that the Viet Cong raid was aimed at obtaining hospital equipment, with Rev. T. Grady Mangham, director of the Christian and Missionary Alliance, telling the New York Times in 1962, “I rather think they were in need of medical supplies.”

Since that evening Vietti’s status remains “Unaccounted For,” with the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency concluding, “The three missionaries were forced to march south, and were eventually executed while in Viet Cong custody. The exact locations and circumstances surrounding their deaths are unknown.”

Rumors remain about their status, with jungle tribesmen through the years claiming that they spotted a white woman with two white men. These assertions have never been substantiated.

Since 1994, the official position within the U.S. government has been that no American captured during the war remains alive.

This article originally appeared in the Military Times on 5/27/24. Here’s the original link:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

July 27, 2024

What did you do in Vietnam?

There wasn’t a safe place anywhere in Vietnam during the war, and every person who served there was at risk of injury or death. In this war, 10% of the military actually patrolled through the jungles and rice paddies in search of the enemy. The rest supported their efforts in the field and mostly spent their nights in highly defended camps. Any inefficiency of these units would have caused a major problem for those living outside the wire. Infantry soldiers referred to them as inferior and called them REMFs. Many Vietnam Veterans know of Marc Leepson. This is what he has to say.

By Marc Leepson

On July 10, 1969, I walked out of an administration building at Fort Myer in Arlington, Virginia. I had just finished the paperwork that processed me out of the Army. I was a civilian for the first time in two years. I felt damn good. I also felt very lucky.

On July 11, 1967, the day I was drafted into the Army, I felt a lot of things, but lucky was not one of them. As I slogged through eight weeks of basic training, the drill instructors rarely missed an opportunity to tell us draftees that we would be headed for infantry Advanced Individual Training at the notorious Fort Polk in the swamps of Louisiana, before going straight to Vietnam—where we’d be lucky to survive our first week.

My good luck began after basic training when I received orders for clerk school. It continued after I arrived in Vietnam on Dec. 15, 1967. After four days at the giant Long Binh Replacement Station near Saigon, I got orders to report to the 527th Personnel Service Company in Qui Nhon, a port on the coast of central South Vietnam—a safe area in the rear. After coming home from the war, I wound up with a great assignment: company clerk for an Army unit in Washington, D.C., where I went to college.

Other than thanking my lucky stars that I survived the war, I don’t recall reflecting much about my service in Vietnam that fine July day 50 years ago when I left the Army. I was just happy to be back in civilian life and have my military service in the rearview mirror. I took a temporary full-time job and then started graduate school. Life was good.

But not completely. Like nearly every other Vietnam veteran coming home to a bitterly divided country, I quickly figured out that hardly anyone wanted to hear about the war from those who had served in it. So I did what nearly all of us returning veterans did: I shut up about it and went about my business. I finished graduate school, got married, screwed around for a couple of years and then embarked on a writing career at age 28 in 1974.

Fire support base in I-Corps

Fire support base in I-CorpsIt wasn’t until the late ’70s that I felt comfortable talking about the Vietnam War and my role in it. Well, mostly comfortable. Although I had mixed feelings about the war, I felt pride in having served my country. But I also felt that pride diminished by the sense that people who didn’t serve, and even some veterans, let it be known in subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) ways that my service as a rear-echelon soldier was inferior to that of “combat veterans.” To this day, I feel demeaned by the assumption that those of us who weren’t in combat units are some sort of second-class veterans. It’s as though there is a two-tier war veteran caste system, with former rear-echelon folks as the untouchables.

When people ask what I did in the Vietnam War, I tell them that I was drafted, then got lucky—that I was a clerk in a personnel company and that only one guy in my unit was killed the year I was there. Most people respond kindly and say, “You served. That’s a good thing.” Or words to that effect. That goes for nearly all of my fellow Vietnam veterans.

Typical hootch in a base camp surrounded by bunkers and layers of sandbags

Typical hootch in a base camp surrounded by bunkers and layers of sandbagsBut—and it’s a significant “but”—I continue to hear “combat veteran” all the time. I admire and respect every Vietnam veteran who served in the combat arms. My feelings have nothing to do with their sterling service. But using “combat veteran” obliquely demeans the service of all of us clerks, cooks, truck drivers and other rear-echelon types. I realize that most people who use that term don’t intend to minimize or mock the wartime service of hundreds of thousands of other veterans, but that’s exactly what it does.

I was astonished to see British journalist Max Hastings go out of his way in his recent, big history of the war, Vietnam: An Epic Tragedy 1945-1975, to deride the service of anyone who wasn’t humping the boonies in Vietnam. How else to interpret this snarky, condescending sentence in which he sums up all rear echeloners’ war service:

“Maybe two-thirds of the men who came home calling themselves veterans—entitled to wear the medal and talk about their PTSD troubles—had been exposed to no greater risk than a man might incur from ill-judged sex or ‘bad shit’ drugs.”

Ken Burns’ much-ballyhooed 18-hour, 2017 Vietnam War documentary all but dismissed the service of men in noncombat units. The show offered hours and hours of grunts fighting but gave only a few minutes to rear-echelon people.

I understand that infantrymen could have negative feelings about us rear echeloners, but we were doing the jobs the military asked us to. And in Vietnam, contrary to Hastings’ ridiculous generalization, you were in danger no matter where you were. In addition to the GI killed in my unit while I was there—Stephen Allsopp, blown up on guard duty in 1968—three other men from the 527th Personnel Service Company lost their lives in Vietnam during the war. As did thousands of others not in the combat arms.

Although there are no official statistics, the best estimate is that 75 to 90 percent of those who served in Vietnam were in support units. That’s more than 2 million men and women who came home without the label “combat veteran.”

My suggestion to fellow veterans and those who never put on the uniform: Please consider dropping “combat veteran” from your vocabulary and replace it with “war veteran.” Or “Vietnam War veteran.” Or “Iraq War veteran” or “Afghanistan War veteran.”

While you’re at it, I wouldn’t mind a “thank you for your service.”

Marc Leepson is a journalist, historian and the author of nine books, most recently, Ballad of the Green Beret: The Life and Wars of Army Staff Sergeant Barry Sadler . He edited the Webster’s New World Dictionary of the Vietnam War and is arts editor, senior writer and columnist for The VVA Veteran , the magazine published by Vietnam Veterans of America.

This article was published in the October 2019 issue of Vietnam.

By Chuck Barone:

Patton said it best. “Every single man in the army plays a vital role. So don’t ever let up. Don’t ever think that your job is unimportant. What if every truck driver decided that he didn’t like the whine of the shells and turned yellow and jumped headlong into a ditch? That cowardly bastard could say to himself, ‘Hell, they won’t miss me, just one man in thousands.’ What if every man said that? Where in the hell would we be then? No, thank God, Americans don’t say that. Every man does his job. Every man is important. The ordnance men are needed to supply the guns, the quartermaster is needed to bring up the food and clothes for us because where we are going there isn’t a hell of a lot to steal. Every last damn man in the mess hall, even the one who boils the water to keep us from getting the GI shits, has a job to do.”

Thank you for your service, brother! And thank you for this great article.

<><><>

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 20, 2024

H Troop 17th Cav Vietnam Tribute

I recently received the following email and video from a young man honoring his father-in-law’s memories. The video blew me away and is put together professionally. Please read his short email and then watch his YouTube film…I sat through the entire video, my senses captivated by what I saw and heard. I’m sure you’ll feel the same.

“Mr. Podlaski,

I just listened to your story on the Echoes of the Vietnam War podcast and am currently browsing your website. Wonderful, powerful stuff and I thank you immensely for sharing and for what your story has grown to. I cannot imagine how many fellow vets you may have helped along the way.

Anyway, I see you have a page on your site where you are accepting tribute videos from fellow Vietnam Veterans with pics and videos they brought home from their tours. Well, I humbly submit one (amateur at best) here for your review and for that alone I am honored to be able to share. This video is the culmination of the last few years of talks with my father-in-law (Al) late into the evening about his experiences in Vietnam and even getting to go to a few reunions with his fellow troopers who are still able to meet once a year and share the bond face to face.

I am forever grateful to my father-in-law for letting me into some very private, life-changing moments in Vietnam and for his buddies with whom I’ve had some powerful conversations. Even 50 years later, just lending an ear with a lot of humility and genuine interest was often all it took for me to be welcomed and get a glimpse of their experiences.

This all began with Al’s sharing the memories he held in two bins in his attic. I was so interested in the Vietnam soldier’s experience, a remarkably unique human experience, that I was all in. I listened. I took pictures of his “stuff”. Over the years, other troopers shared their photos with me. It was overwhelming – in a very good way. I was trying to think of a way to help “preserve” their hard-earned memories and at the same time to actually give something back in return, not only for what they have done for our country, but for what they endured when they returned home, and also for what they have done by letting me into their private H Troop family.

And so, with only pictures of pictures on an iPhone and no idea what would come next, I figured the best way forward was to get these pics into a slideshow. I played with iMovie on my phone and knew this could be something special. After learning how to add the music of your era to help narrate their story, and many, many errors, revisions, and edits … here it is:

From the draft to basic training, to Vietnam, and home again. Although this is a thank you specifically to the men of H Troop, I hope my “thank you” and “welcome home” messages come across loud and clear to ALL our Vietnam veterans. It’s about 1 hour and 41 minutes long and includes twenty-one songs, tons of pictures, a few letters home, a few short interviews, and a bunch of 8mm video footage (some pretty rough but I love it). The last few minutes include a tribute to those who died in Vietnam while serving in this fine outfit.

Thank you very much. I hope this video does justice to your memories, both good and bad.

It’s been an honor.

Highest regards,

Scott Fedigan

Auburn, NY”

*****

Thank you for taking the time to view this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 13, 2024

Vietnam Lost Films – The Beginning

In 1965, enemy soldiers attacked US air bases in Vietnam and caused much destruction. Johnson sent more troops to help defend these bases, and soon after, the military shifted its strategy from defense to offense. This film begins with the first wave of soldiers arriving in the country, followed by Operation Rolling Thunder as planes roared across the skies and into North Vietnam. Infantry soldiers had successfully patrolled around these bases and, up until then, provided security for those inside. In November, the US military finally took the war to the enemy, planning an attack on a known enemy sanctuary in the mountains of the Central Highlands. The American soldiers soon found themselves outnumbered in the Ia Drang Valley, and soldiers on both sides died in this first major battle of the war.

By the end of 1965, 185,000 U.S. troops were in Vietnam, and it was no longer just South Vietnam’s war.

This film documents the early part of the Vietnam War in the words of Americans who served there. It features home movies and rare archival footage – some had never been seen before. See the war as it was never seen before and witness what our military endured and overcame.

WARNING: GRAPHIC SCENES – VIEWER DISCRETION IS ADVISED!

To read more about the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley, check out this prior post on my website:

Battle of Ia Drang Valley

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!