John Podlaski's Blog, page 10

December 16, 2023

Remembering Our Vietnam War Dead

This article originally appeared on the website “War Stories” on Memorial Day 2019. The author hits a home run with this analogy of the Vietnam War. He places readers into the heads of our Warriors, offering them a glimpse of what we endured after the war. And then, he reminds us all of what Memorial Day should be. Take a few minutes to read what he had to say.

By Spencer Matteson

“After a year I felt so plugged in to all the stories and the images and the fear that even the dead started telling me stories, you’d hear them out of a remote but accessible space where there were no ideas, no emotions, no facts, no proper language, only clean information. However many times it happened, whether I’d known them or not, no matter what I’d felt about them or the way they’d died, their story was always there and it was always the same: it went, “Put yourself in my place.”

― Michael Herr, Dispatches

Death is something we hide from. In our society, we pay people to do the job most of us would never do. We pay handsomely for others to tend to our dead. We only look at them after they’ve been cleaned up, dressed up, made presentable – in other words, made to look as if they’re still alive and sleeping peacefully. And if that’s not possible, we simply close the lid on them.

In war, soldiers don’t have that luxury. We who have been to war and are combat veterans were subjected to the extreme violence of the modern-day battlefield. We saw firsthand what M16s, hand grenades, artillery shells, bombs, napalm, and other means of killing we’ve invented can do to a healthy, young body. In addition to creating the mess in a firefight, we had to clean it up as well – all while dealing with the grief of losing good friends and fellow soldiers – men killed in unspeakable and grotesque ways. It was hard – physically, psychologically, and spiritually.

Many of us were unable to cope with it, were not able to get through it, and return to anything like a normal life. Thousands of Vietnam veterans ended their own lives rather than live with the memory of it. Others tried whatever they could to forget – alcohol and drugs usually, but in the long run that only messed them up worse. Still, others simply went insane and parted ways with reality. War in many ways is the “gift” that keeps on giving. It continues to claim victims years after the bullets have stopped flying and the bombs have stopped dropping. Many men die in war but don’t drop until years later. They are not remembered or honored on monuments, not mentioned in Memorial Day speeches, but they are war casualties nonetheless – the same as if they’d gotten a bullet through the head.

The hell that was served to the youth of my generation was that we were brought up in the era shortly after World War II. Our country was basking in the glory of a war well fought and won. A war fought with rectitude, for righteous reasons. We were weaned on John Wayne and Audie Murphy movies, given a glossed-over history of our country in school (and on television), and were totally convinced that we Americans were always the good guys and our government leaders were patriots and therefore would never lie to us. Vietnam made us question all that. We began to rethink everything we learned when we were growing up and in my case anyway, it was bitterly heartbreaking. I, like the majority of Vietnam Vets, was a volunteer. There were other reasons why I joined the army, but one of the main ones was to serve my country. Then I discovered my country wasn’t what I thought it was.

That our leaders would send us into an unwinnable war without a viable exit strategy and without any (or damn little) indoctrination as to why we were being sent I feel was part of the reason we lost. We weren’t motivated. We were simply told that communism was bad and we had to draw the line in Vietnam, domino theory, all of Asia would fall, etc., etc. Turns out the domino theory was dead wrong – after the war, Vietnam went into Cambodia, overthrew Pol Pot’s murderous, communist regime, and reinstalled the monarchy, which is to this day still in power – the exact opposite of the domino theory doctrine.

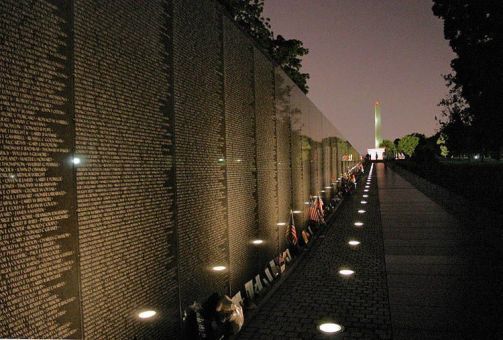

Regardless of what you thought about the Vietnam War, the fact is that 2,709,918 Americans served in Vietnam, representing almost 10% of their (very large) generation. 40% to 60% of those were either in combat, provided close support, or were regularly exposed to enemy attack. 58,318 names of American men and women who died in the war are etched on the black granite slabs of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. 11,465 of those on the wall were not yet 20 years old, still teenagers – 5 of them were just 16 years old. Kids.

It is fitting and important on this Memorial Day, that we take time out from our burgers and beer to remember the people who gave their lives for this country. To remember their deaths in all its raw ugliness. Remember that for every name on the wall, there was a family back home – wives, girlfriends, children, and friends affected by their death. Remember that it could have been you or someone in your family. Remember that our leaders sent tens of thousands of young men and women to their deaths in the prime of their lives. To remember that it can and will happen again – indeed, still is happening. Remember that unless we put an end to war, it will surely put an end to us all.

Put yourself in their place.

From the author:

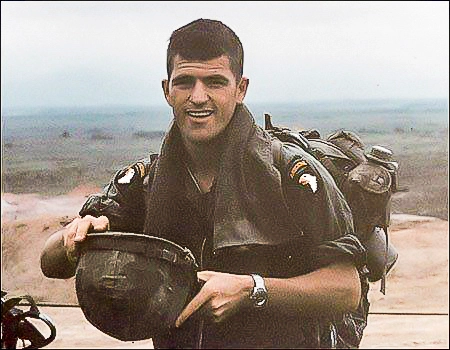

I spent a year and a day in Vietnam with the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division. I was in Charlie Company, 1st Batallion, 12th Cavalry Regiment (Airborne), from May 1966 to May 1967. Our base camp, Camp Radcliff was in the central highlands of Vietnam outside the small farming village of An Khe (now a town of over 50,000). We were on field operations almost continuously during the year I was there, with only a few short breaks. Our operations were in the provinces of the central coast and the central highlands. Of all the firefights and skirmishes I was in, this night a LZ Bird was the most intense and the most horrifying. I was 19 years old at the time and it has colored my entire adult life since. When I saw the inhumanity, brutality and ugliness of war up close, it turned me into a lifelong pacifist. I realized that though there are things worth fighting for, most of our wars are based on lies and started for reasons and ideas that are just plain wrong. If the human race is to survive, we need to find a way to get along together, or we’re all going to die together.

Here is the direct link to the article: https://warstoriesweb.wordpress.com/

*****

Admin: Readers, can you add to Spencer’s analogy?

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

December 15, 2023

End of the Year Book Sale

I’m excited to announce that my e-books will be promoted on @Smashwords as part of their End of Year Sale from December 15th until the 31st! My 3-short stories are FREE and my 3-Vietnam War books are reduced by 50%. Don’t miss out on this opportunity. https://www.smashwords.com/profile/view/jpodlaski

December 9, 2023

A Chunk of My Life Was Taken From Me. You Could Say I Had a Bad Attitude.

After completing our tours in Vietnam, many of us still had stateside duty assignments of a year or less to complete before ETS. Some had a difficult time “fitting in” with the pomp and formality of stateside military duty. Others struggled but complied. Some jobs were great, others not so much. Here’s what one man ‘fell into’ and ended up loving it.

by Ed Meagher

When I returned from Vietnam in February of 1969 I had a bad attitude—a very bad attitude.

I joined the Air Force to escape college and a broken heart (another story entirely). It turned out that the discipline, order, and focus the Air Force provided was exactly what I needed, and for the first 18 months, I thrived.

My first duty station was an aircraft control and warning site on the northwest coast of the island of Luzon in the Philippines—100 airmen and contractors on a cliff above the South China Sea. Though there was nothing to complain about, we did manage to grouse about the isolation.

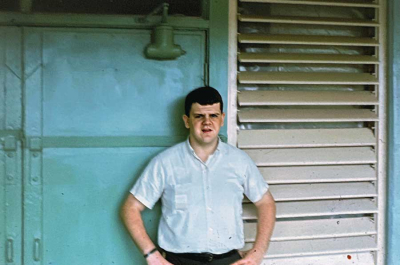

Ed Meagher in the Philippines in 1967. Photo courtesy of the author.

I found books and started a library (yet another story entirely). A mentor guided my reading, and I used the endless hours to devour books of every sort. The work I did was challenging and rewarding, and then I got to read sitting in a chair overlooking the South China Sea. I remember the feeling to this day—I was a kid who fell into a vat of chocolate and got to swim in it.

After seven months I transferred to Clark Air Base in Southern Luzon north of Manila. Despite tens of thousands of airmen and contractors and a far more hectic work schedule, I still found a quiet place to fall into books.

As I neared the end of my tour in the Philippines, I chose to go to Vietnam. To this day I have a difficult time talking about my time there. I was unprepared for the enormous responsibilities thrust upon me. The stakes were high, as high as they get. I wish I could have done better, been better. But I know I did the best I could at the time.

Still, I was different when I arrived at the Pentagon in 1969, and so was the world. Three years earlier, the radio had played Peter, Paul, and Mary, and hootenannies were still in fashion. Now, Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones blared from boom boxes, and it seemed like everyone had just returned from Woodstock.

Meanwhile, I’d spent a year in fear of death or dismemberment. I couldn’t lower my perception of the threat level around me, and I couldn’t explain my feelings to anyone. Everything felt trivial, everyone around me out of touch with reality.

Military life stateside was also far different than military life overseas where the attitude was, “Do your job, stay out of trouble, and don’t be a slob.” We’d been too busy with real military operations to tolerate “chickenshit.” It seemed to me my Pentagon assignment was built solely on unadulterated chickenshit.

It started my first day on the job after a month at home. I’d spent two and a half years in fatigues or flight utility uniforms, and no one cared how they looked on me or anyone else. Now I reported to duty in my dress uniform for the first time since it was issued in basic training. It was a little ragged—no name tag or ribbon rack, and my sister may not have sewn on my new rank correctly. I couldn’t find my dress shoes, so I wore my jungle boots. I also needed a haircut.

Ed Meagher loved the first 18 months of his Air Force career at Wallace Air Station on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, now Naval Station Ernesto Ogbinar. From there, Meagher headed to Vietnam. By the time he arrived at the Pentagon in 1969, he had resolved to leave the Air Force. Photo courtesy of the author.

Most importantly, I didn’t want to be there. A month’s vacation convinced me I was done with the Air Force. A huge chunk of my life had been taken from me. I’d missed all the major milestones of my generation. In general, as I believe I mentioned, I had a bad attitude.

As I walked across the massive concourse in the Pentagon, I felt like a polar bear at a beach resort. I noticed several glances and double-takes. Then I saw a newly minted second lieutenant walking directly toward me. I tried to angle away from him, but he was coming for me. He stopped me with a sharp “Sergeant” that I couldn’t ignore, then asked my name.

I answered without using “sir” or “lieutenant,” and he called me on it. He told me I was out of uniform, and I agreed with him. He waited for an explanation, and when I didn’t give him one, he asked. Point in my favor. After I explained, he told me that was no excuse. I told him he was making me late for a meeting with my new commanding officer, wished him a good day, and walked away. I believe I may have mentioned that I had a bad attitude.

It didn’t go a lot better when I reported in. I met with a first lieutenant who may or may not have been my boss. He was about to dismiss me for the day when the squadron chief master sergeant burst into the office in a fit. He’d heard about me, and he very insincerely apologized to the lieutenant for my appearance, for my imposition on his valuable time, and for my very existence. He saluted the lieutenant, then turned and growled at me, “In my office, Sergeant, now.”

The rest of the day didn’t go a lot better. As the chief ranted and raved over my hair and jungle boots, I struggled not to laugh. I’d been in the culture long enough to know to agree with whatever he said and say as little as possible in response.

I had 12 months left in my military career, and I didn’t know how I would survive it. That’s when one of my many undeserved good karma gifts arrived in the form of Hap Arnold.

I’d come to the Pentagon with a recommendation attached to my personnel record that the Air Force retain me. The service had spent a lot of money on my training, and I’d performed well for three years. As a result, I was assigned a retention counselor to convince me to reenlist for another four years. Hap was a retired Air Force chief master sergeant-turned-GS-11 Air Force civilian.

We hit it off when I noticed a Chicago Cubs banner in his office that said, “We’ll win the World Series next year.” We spent the first 15 minutes talking baseball. When we got down to business, I told him there was no way I was going to reenlist. He asked why and I vented for several minutes.

He listened quietly, then said, “Wow, I’m sorry to hear all that. How can I help?”

I told him how the Air Force had denied an off-base housing allotment, and that all my uniforms and baggage from Vietnam had been lost. Hap arranged for me to receive both the housing allotment and a uniform allotment. My biggest problem, though, was my assignment. I’d received a demeaning job with the worst possible schedule. He told me that might take a little while to fix, but he’d work on it as long as I lightened up on my bad attitude. We shook on it, and believe it or not, that is really the story I started out to tell.

A couple of weeks later I got a message to report to Hap’s office. We chatted for a few minutes, but it was clear from the look on his face that he had some good news for me. He had called in a favor; I was transferring to the Military District of Washington Command Post. That alone was an answered prayer, but Hap had more.

As Ed Meagher neared the end of his tour in the Philippines, he chose to go to Vietnam. To this day, he has a difficult time talking about that life-changing experience. Photo courtesy of the author.

He had gotten me assigned as the duty noncommissioned officer in charge of the entire Military District of Washington each weekend. It was an insignificant trash job that no one in their right mind would want, but he knew I would love it and I did. I worked 12-hour shifts Friday, Saturday, and Sunday nights from six p.m. to six a.m. No formations, no inspections, and no harassment. Just, “Do your job, stay out of trouble, and don’t look like a slob.” The transfer was immediate. When I reported for duty, I was most definitely “STRAC”—military slang for “a well-organized, well-turned-out warrior,” including a “high and tight” haircut.

The Military District of Washington is an artifact of the Civil War, formed to protect the capital. While it still serves that role, its duties are mostly ceremonial now. Most importantly, and for the purpose of this story, any active-duty service members who are not under orders from their command and find themselves in the Military District of Washington also find themselves under its command. I served as the single point of contact for any problems that arose during the weekend or for any active-duty servicemember who wandered into the Military District of Washington. And they did wander in, for several reasons, including to frequent one of the dozens of after-hour night clubs in the southwest quadrant of Washington where “blue laws” were unofficially relaxed.

Everything about these clubs was conveyed by word of mouth. Some were known for their music or dance bands, others for their class and decor. All were known for their booze, and many were known as strip clubs, or “titty bars.” These places attracted the most military personnel who came to the Military District of Washington.

My job was simple. By six p.m. on Fridays, we settled into a trailer with four phone lines. One was an open line to the command center. Another was a direct line to the military police office at Fort McNair in southeast D.C. The third was a line to the Metropolitan Police District Six front desk. The fourth line was the most interesting. It was a regular D.C. phone number that was very quietly given to the owners, bartenders, and bouncers of these illegal-but-tolerated after-hour clubs with the understanding that they’d call it for a resolution if there was ever an issue with a G.I.

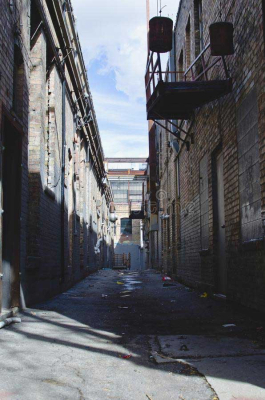

An alley in the southwest quadrant of Washington, D.C., in 1970, where “blue laws” were unofficially relaxed. Service members frequented the bars, nightclubs, and strip clubs here—and from time to time got into trouble. That’s when Ed Meagher, the duty noncommissioned officer in charge of the entire Military District of Washington each weekend, was called. Photo courtesy of the author.

The first calls came in around 10 p.m. Every call was unique, but in truth, they were the same: Pfc. or Sgt. or Lt. So and So had gone to a club, had several drinks, engaged in conversation with a lovely young lady, bought the young lady several glasses of champagne, and then suggested they continue the evening in a less public place. Often at this point, the lovely young lady would lose interest and head backstage, and the soldier, sailor, airman, or Marine would receive a bill that approached their monthly pay. Harsh words were exchanged, followed by various forms of martial arts. While these warriors displayed some courage and even skill, it always resulted in them being handcuffed to a wall in a closet or storage room in the back of a club, where inevitably this mysterious phone number was written on the wall.

That’s where I came in.

Two large, newly minted, temporary military police officers and I would head to this location. We first checked on the physical condition of our combatants. Most bouncers stopped short of great harm for fear of sending them to a hospital, and the ensuing, inevitable questions. If their injuries did not appear life-threatening, we moved on to the next phase. This involved collecting all the money the G.I. had in his possession.

I required them to turn their pockets inside out and take off their shoes and socks. I took the money, met the bar owner or manager, and offered whatever it was to settle their bills. There was no real negotiation; either they took it or I’d call the cops and let them sort it out. Since involving the police was a nonstarter, the negotiations ended, and we moved on to phase three—often the most difficult.

Dealing with still-drunk combatants who often outranked me and wanted a second round with the bouncer was never easy. Before I had them released from the club’s bracelets, I told them their best option was to go quietly back to our trailers to sort out this injustice. Most did, after some heated discussion, but every once in a while, I needed the muscle provided by our two young and eager military police officers.

Once back at the trailer, we sorted them into a holding cell, a cot, or a vomitorium in the back. At about five a.m. we woke them, and I told them I was just the greatest guy in the whole world and they could return to their units without any record of their indiscretions, or I could drive them in handcuffs to the stockade at Fort Myer to deal with the full force of the military justice system. Only one to my memory, a young Marine lieutenant, chose the second option.

This detail saved my military career. It filled all my needs at that point in my life. Strange as it may sound, I found it rewarding, and most importantly it got me over my bad attitude.

Admin: How did you fare after your tour of duty in Vietnam?

Ed Meagher

Ed MeagherEdward Meagher is a Vietnam service-disabled veteran who retired after 24 years in government, 26 years in the private sector, and four years in the U.S. Air Force. He served for seven years as the deputy assistant secretary and deputy CIO at the Department of Veterans Affairs. He lives in Great Falls, Virginia.

*****

This article originally appeared on THE WARHORSE website on May 3, 2023. Here is the link: https://thewarhorse.org/air-force-veteran-recalls-washington-detail-that-saved-him/

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

December 2, 2023

MY LAST ’NAM FLIGHT

photo courtesy of CHRISTOPHER GAYNOR

One soldier recounts his flight home from Vietnam. How many of you had a similar experience?

By Douglas Crow, retired

We were given a ride in the Jeep on the morning of April 5th, 1970 to Phouc Vinh Airport and we waited four hours to catch a flight to Bien Hoa.

While boarding the De Havilland C-4 Caribou, its engines idled with a low coughing moan. I took a seat while looking out the opposite window and saw a Navajo Cavalryman sitting there in the hot noon sun. Silently and without motion or seeming emotion he sat passively.

As the engines idled, I watched the shadow of the rotating propeller blades being cast on the runway. The crew chief, sweaty as usual and carrying a revolver slung low on his hip, brought the boarding plank up into the aircraft’s belly and with a loud whirring sound of a servo motor brought up the aft door. The chief mumbled something in his headset, walked to the front of the craft just behind the cockpit cabin entrance, strapped himself in and fiddled with a circular slide-rule in conjunction with a map.

The pilot looked all around for visual clearance then slowly moved the throttles forward and as I looked out the circular port windows, I could no longer discern the shadows of the propeller blades but only a faint, grey oval optical shadow. The engines coughed a little but rallied and slapped the air with determination. The pregnant bird began to move and a vibration growled and grated throughout the fuselage as the bird’s wheels rolled faster and faster over the corrugated, olive drab-painted, steel runway. The grass on the airfield was tan and dead. As the Caribou taxied down the ramp I thought about the Navajo Cavalryman and it suddenly dawned on me that any time I left a place or arrived someplace in Vietnam, I had always seen at least one American Indian in jungle fatigues.

It’s funny that I should have realized that so late in the year, but as I thought back over the times of traveling through in-country airports; the three-day R&R to Vung Tau, the Hawaii R&R, the battalion moves to and from Tay Ninh and Phouc Vinh, I suddenly recalled meeting, talking with, or seeing American Indians at practically all those locations and that seemed unusual to me.

The Caribou swung around at the end of the runway, its brakes squealing as it came to a stop. After checking an operations list and conversing over a microphone, the pilot thrust the throttles fully forward for the takeoff. The craft sat there lurching for a minute, straining all its power against the brakes, wings shifting back and forth. Watching all the loose rivets bob and bounce as the craft trembled with a tooth-tingling vibration made me question whether the rivets were attended to during the craft’s overhaul maintenance.

At last the brake was released and everyone in their side-by-side, single-line, orange polyester web seats seemed to be thrown almost on top of each other from force suddenly thrust upon us by the bird’s takeoff momentum. The aircraft seemed to struggle to get off the ground, like some frightened, waterfowl that had just been shot at. It rolled and rolled over the runway picking up more speed and with both engines thrumming with maximum power, the flight finally became airborne.

The Caribou is an over-wing aircraft and its round, port-like, windows are beneath the wings. The portion of the red nylon webbing bench I occupied happened to be positioned at the point where the wings joined the fuselage which gave me a full view out the port window, rendering the underside portion of the engine nacelle fully visible to me. We must have now been at an altitude of about 1500 feet or so and as we heard a servo motor groaning somewhere in the wings, the still-spinning wheels retracted themselves up through and into the bottom of the engine nacelles with the landing gear doors closing shut immediately thereafter.

At last, Phouc Vinh was behind and below us. Looking back, we could see the JAG and PIO buildings which seemed not all that far from the edge of the Camp Gorvad perimeter green-line bunkers and tower fortifications facing the vast rubber plantation stretching outwards toward a hazy horizon.

After an uneventful, short flight we were now in the approach landing pattern at Bien Hoa Airfield and in just 15 short minutes the Caribou’s wheels touched down on the airport’s runway with a barely audible and lightly felt screeching sound. As the aircraft rumbled up the ramp toward the terminal, the crew chief hurriedly unstrapped himself, hopscotched aft, and opened the rear exit ramp door. The door lowered with a slow but constant hydraulic moan as the horizon shimmered through the mirage-like heat rising from the runway. The craft slowed as the pilot cut the engines, and the prop blades swung ever slower until the sound of the engine’s valve lifters became discernible.

A procession of red-soiled, soldiers clad in jungle fatigues emerged through the Caribou’s aft ramp bay. Their postures were thrust forward because of their weighty packs as they set one foot in-front-of-the-other. Fixed eyes stared intently from beneath the heavy steel helmets and a PRC-25 radio antenna swung absurdly as an RTO (Radio Telephone Operator) made his way to the terminal. Finally, they were all lost to the throng milling about inside Bien Hoa terminal.

I must’ve sat at that terminal for an hour or so waiting for a bus to be transported to the Cavalry’s R&R DEROS Center. I finally boarded a bus, but got tangled up in misunderstood semantics and ended up in Long Binh for another hour or so before finally catching a bus ride and arriving at the R&R DEROS Center just before curfew. From then until late last night when boarding the “freedom bird,” my perceptions were a timeless blur of sleepless, hypnotic waiting.

THE FREEDOM BIRD

My entire military Vietnam out-processing phase had been blessed with artillery silence. There were tales I had heard from other soldiers about returnees being killed by enemy 122 rockets while they were waiting for or boarding their freedom birds, but I really didn’t know whether these stories were true or not. Admittedly, the fear those tales may have been true hung over me like an axe all year. Indeed, I think that’s probably why I never was really overwhelmed by “short timer’s fever” or never felt “short.”

At long last, we boarded the 707 passenger liner in our jungle fatigues and I broke out in a cold sweat as the bird whistled down the runway. Finally, the great silver bird roared off the runway and ascended to an altitude far out-of-range of enemy .51-caliber enemy guns or rockets in no time at all!

But nothing happened, thank God, and the whole planeload of GIs cheered and screamed uncontrollably as the craft flew over the Vietnam Coastline out toward the Pacific and homeward. I have really never had such a feeling of total relief and freedom in my life as I had during that departure. To really know that at last, the threat of some rocket with my name on it was once-and-for-all extinguished at that country’s shoreline was unforgettable. The lifting of that burden puts a whole new fresh breath into one’s life! WOW, just plain WOOOWW!

BACK IN “THE WORLD”

By 1982, after the end of my stateside military service at Fort Riley, Kansas, employment difficulties, marriage tensions, the ambient anti-war sentiments, and a general cultural dislike of anything military, it became apparent to me that I was having just way too many close-call, near-misses, and narrow escapes. In analyzing these incidents, it became shockingly clear that there was something of a self-destructive dynamic occurring within my being. And that I was engaging in subconscious attempts to end my life!

Despite my analysis, just the fact that I was apparently being controlled by a “death wish” was an overwhelming shock. It was as if there was some indiscernible, subconscious, hunter-killer submarine pursuing me. All I knew was that I had to quickly discover the source of this threat before it sent me to the deep six. Becoming conscious of my apparent classic case of “survivors’ guilt” substantially unnerved me and I knew I had to overcome it in short order before it overcame me.

Upon that realization, I immediately sought help from my family, mental health professionals in the private sector, the Veterans Administration, and Vet Center Counselors where I lived.

It heartens me to report that if it were not for my Creator, Family, Country and the VA in particular, I am certain, retrospectively, that I would have become yet another non-KIA statistic of that war. I credit my Maker, beloved father and mother together with the Veterans Administration for my recovery from that deadly, tumultuous interval. If it were not for these blessed positive elements available to me, I am convinced my physical and mental welfare would have been severely denigrated if not annihilated.

Douglas Crow had an earlier post published on my website titled “Close Calls”. You can find it here: https://cherrieswriter.com/2020/09/20/close-ones-during-the-vietnam-war/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or change occurs on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 25, 2023

A Memory I Can’t Forget

The author recreates an experience he had while serving in Vietnam. He was awestruck and helpless at the time. It is something he will never forget.

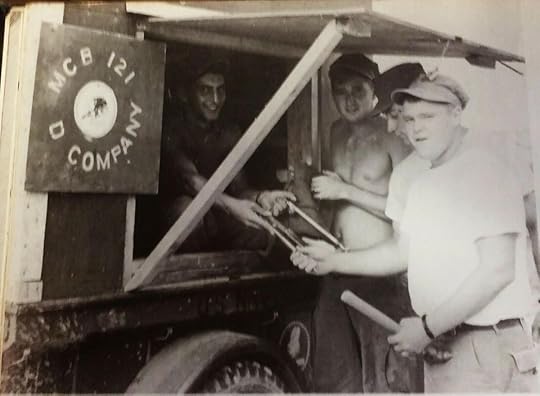

December 1967 at a bridge south of Phu Bai. We were building a creosote timber bridge to replace one that had been blown up by the VC. It was about 75 yards across the river and the Army Engineers had installed a temporary flotation bridge just below the bridge we were building. The traffic up and down Highway 1 would go down a ramp and slowly cross the bridge.

On top of the bridge where we worked, we were about 15 feet higher than the flotation bridge. About 100 feet upstream from where we worked an old rusty steel bridge still carried trains across the river. A little village was right there on both sides of highway one immediately north of the bridge. It wasn’t very large but approximately 100 villagers lived there. A platoon of South Vietnam Soldiers were also stationed nearby to protect the village and bridge.

I was on top of the bridge nailing decking on a section of the bridge when late in the afternoon, my Squad Leader told me to go into the village and see if I could purchase some cold drinks. I grabbed my web belt and buckled it and picked up my M-16 rifle.

Sometimes we were able to buy cold drinks in the village, they had a drink they claimed was Coca Cola but it didn’t taste much like it. It usually was flat tasting.

I walked into the village I had slung my rifle over my shoulder by the sling. I got to the old lady’s house that sold the cokes and she met me at the entrance. The house was small and had cardboard boxes flattened out and tacked on the outside. The roof was thatched with big leaves and they hung over by about a foot.

She inclined her head to me and then looked up and asked what I needed. I told her cold drinks and she said, “Aaah,“ and turned, disappearing back inside her house. She came back out with a canvas bag filled with cool drinks. I smiled and asked her how much I owed her. She told me and I gave her a 500 piaster note. A big grin split her face before she grabbed the money; her teeth were bright red. I thanked her and turned to leave and headed back to the river.

Suddenly I saw a half dozen Vietnamese soldiers emerge from between two huts. They were dragging a young Vietnamese boy between two of them while the others followed behind. I stood and watched them heading toward the river dragging this boy. He was terrified. Screaming and crying, and tried unsuccessfully to dig his heels in as they continued toward the river, the soldiers were stronger. They were all talking in Vietnamese and I couldn’t understand what they were saying. Curious, I followed closely behind.

As we neared the old railroad bridge the young boy tried to jerk away from his captors. One of them backhanded him savagely and the boy sagged between them. I didn’t like the way this was going. Some of the villagers had also gathered and stood back about twenty feet, most were crying and wringing their hands. One of them screamed at the boy’s captors, who then screamed back, silencing the group.

As I stood off to the side, I set the filled Coke bag down on the ground, slipped my weapon off my shoulder and raised it toward a firing position. One of the Vietnamese soldiers saw me, then quickly raised his own weapon and aimed it at me. He looked at me and shook his head, saying, “No No.“ He then switched his M-1 Carbine from safe to fire and waited to see what I’d do next.

Stunned, I reslung my weapon onto my shoulder and stood there watching in awe. An ARVN soldier brought a rope and tied it around the boy who groaned and began waking up. Two of them yanked him from the ground and carried the boy up onto the railroad bridge. They marched about twenty yards from shore and lowered him over the side, tying the rope so he was suspended just above the water.

He came to again and began crying and screaming, his body moved about frantically in attempts to free himself. The two Soldiers left the bridge and came down to join the others. Without a word, they lined up as a firing squad and prepared to fire at him.

I was now guarded by two of them. One pointed to the boy and said,” VC”. I shook my head in rebuttal and looked down to the ground. Suddenly, one of the soldiers fired and hit the boy in the leg. Seconds later, a multitude of shots followed. The screaming came in spurts and then became silent. I walked away as they reloaded. The ARVN soldiers continued to fire at his extremities until they were gone.

I was sick after watching them execute the young boy. As I neared the creosote bridge, I went behind a stack of boards and threw up, heaving until I could no more. When I looked back up towards the railroad bridge, I saw the body hanging there, only a torso swinging in the wind. The ARVN soldiers walked away celebrating.

For days I was sick over this and kept telling myself there was nothing I could have done to prevent this tragedy. And to this day, I can not get this experience out of my head. Just another day in Vietnam.

This article originally appeared on my Facebook Group page: I-Corps, Viet Nam June 28, 2019. If you are a Nam Vet and served in I-Corps, then consider joining this group.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 18, 2023

AS US TROOPS WITHDREW FROM VIETNAM IN 1972, THIS CITY REFUSED TO SURRENDER TO COMMUNIST INVADERS

Three U.S. advisers seek protection from incoming North Vietnamese artillery on April 3, 1972. The communist assault on the South, dubbed the Easter Offensive, triggered intense fighting in and around the town of An Loc, just 60 miles north of Saigon, inspiring acts of sacrifice and heroism among both South Vietnamese and American defenders. (AP photo)

Three U.S. advisers seek protection from incoming North Vietnamese artillery on April 3, 1972. The communist assault on the South, dubbed the Easter Offensive, triggered intense fighting in and around the town of An Loc, just 60 miles north of Saigon, inspiring acts of sacrifice and heroism among both South Vietnamese and American defenders. (AP photo)

During the Easter Offensive of 1972, these American advisers gave their all to save An Loc and prevent the fall of Saigon and ultimately South Vietnam.

Easter came early in 1972 and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) came with it. On March 30, “Holy Thursday,” three NVA divisions stormed out of Laos and across the DMZ. It was the first of multiple assaults that struck not only the northern provinces of South Vietnam but also Kontum in the Central Highlands and An Loc, only 60 miles north of Saigon.

North Vietnam was “going for broke,” committing its entire combat capability—14 divisions and 26 separate regiments, all with attached armor and heavy artillery units. Enemy forces numbered 130,000 troops and 1,200 tracked vehicles, primarily tanks. Aging Communist revolutionaries controlling Hanoi’s Politburo believed the time was right to achieve a decisive military victory, topple South Vietnam’s government, and embarrass the United States.

As U.S. military personnel continued to withdraw, American troop strength was brought down to 69,000. Only two U.S. combat brigades remained—their missions were restricted to guarding airbases and patrolling the surrounding areas. Although the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) listed 5,300 men as “advisers,” the only Americans fighting on the ground were a handful of men serving with provincial advisory teams and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) divisions and regiments.

As a result of Vietnamization, battalion advisers were only authorized in the Airborne Division, Marine Division, and selected Ranger units. There were also battalion advisers, mainly NCOs, with the ARVN field artillery battalions.

AMERICANS ON THE FRONT LINESThe term “adviser” was a misnomer. By 1972, advice was rarely solicited and when offered, rarely heeded. However, U.S. advisers often cajoled and encouraged their counterparts, particularly in dire situations when spirits were flagging. The presence of even a lone American adviser was a morale booster, as every ARVN soldier knew they would not be abandoned as long as one American was with them.

The advisers’ primary role was employing the massive air assets President Richard M. Nixon had sent to South Vietnam. U.S. air power proved decisive in blunting the 1972 enemy offensive. Advisers routinely exposed themselves to NVA fire while working with USAF forward air controllers, identifying lucrative targets and adjusting air strikes to ensure bombs were “on target.”

Americans who remained on the front lines, especially advisers with airborne and Marine battalions, suffered significant casualties. Adm. Chester Nimitz’s famous quote after World War II’s Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945 was equally applicable to the advisers who helped turn back the NVA offensive 27 years later: “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

Early in 1972, allied intelligence personnel were watching NVA build-ups in Laos and Cambodia but had no idea of the timing of a possible offensive. When it occurred, the ARVN Joint General Staff (JGS) and MACV were surprised by its scale and ferocity. With fighting raging in three areas, military officials were unable to determine the communist main attack. The focus of III Corps, the ARVN headquarters responsible for provinces surrounding Saigon, was on enemy attacks in Tay Ninh. These were diversionary operations, masking the movement of three NVA units: 5th VC Division, 9th VC Division, and 7th NVA Division. The 5th and 9th were VC in name only; they were manned and equipped by the North Vietnamese Army.

The situation grew more tenuous on April 5, 1972, when those divisions—36,000 troops organized into combined arms teams of infantry, armor, heavy artillery, and engineers—poured across the Cambodian border into Binh Long Province. The immediate threat to the government in Saigon was clear.

South Vietnamese paratroopers march north along National Route 13 (QL 13), the main road from Saigon, on April 8, 1972. The troops are heading to the provincial capital of An Loc to try to counter the gains made by the communists when they poured over the Cambodian border a few days earlier. (AP Photo)

South Vietnamese paratroopers march north along National Route 13 (QL 13), the main road from Saigon, on April 8, 1972. The troops are heading to the provincial capital of An Loc to try to counter the gains made by the communists when they poured over the Cambodian border a few days earlier. (AP Photo)

Maj. Gen. James F. Hollingsworth, commander of the Third Regional Assistance Command (TRAC), urged Gen. Nguyen Van Minh, III Corps commander, to reinforce An Loc, the provincial capital. Hollingsworth, a 1940 graduate of Texas A&M University, was one of Gen. George S. Patton’s outstanding tank commanders during World War II. He led from the front and during his service in three wars he was awarded three Distinguished Service Crosses (DSC), the nation’s second highest award for valor, four Silver Stars and six Purple Hearts, plus four Distinguished Service Medals and 38 Air Medals.

Known as “Holly,” he was also a Korean War veteran and had served a previous Vietnam tour as assistant division commander of the famed 1st Infantry Division. Advisers revered him and were grateful for the air support he was able to muster.

A CITY UNDER SIEGEThe district town of Loc Ninh, a few miles from the Cambodian border, fell on April 7 when the NVA overran it, killing or capturing nearly 1,000 soldiers. Two U.S. advisers were killed and seven were listed as missing in action. Only 100 ARVN defenders and one American, Maj. Tom Davidson, managed to escape the battle and make their way to An Loc, which was 15 miles south and obviously the enemy’s next target. The 5th ARVN Division defended An Loc with three infantry regiments, two ranger battalions, and provincial forces.

James F. Hollingsworth. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

James F. Hollingsworth. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

If An Loc was lost, there were no ARVN troops to stop an enemy move on Saigon. President Nguyen Van Thieu issued a directive that An Loc must be held at all costs. The well-publicized order caught the attention of the communists, challenging them to quickly capture it. The pivotal battle for An Loc and the heroism of U.S. advisers there was a microcosm of the fighting throughout South Vietnam in what the U.S. press now called the Easter Offensive.

On April 7, 1972, President Thieu convened a meeting of his key advisers and corps commanders to assess the military situation; it was a grim session. General Minh outlined his circumstances and requested more troops to reinforce An Loc, surrounded by the 5th and 9th VC Divisions. He also pointed out the 7th NVA Division had cut the main supply route, QL (National Route) 13, into the provincial capital, isolating the defenders.

Because of the enemy’s proximity to Saigon, the president made the unprecedented decision to commit the country’s last reserve, the 1st Airborne Brigade, to III Corps. He also directed the 21st ARVN Division move from the relatively quiet Mekong Delta region and join the battle in Binh Long Province.

By the afternoon of April 8, the 1st Airborne Brigade, augmented by the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion, was assembled south of An Loc, ready to fight. The 81st was originally activated as a reaction force during the days of cross-border operations into Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam. Now, it was employed as an elite infantry battalion. It was teamed with the Airborne Division because its advisers were part of the Airborne Division Assistance Team, also designated MACV Team 162. The brigade’s 2,000-plus paratroopers were tasked to open QL 13 into An Loc. Soldiers of the 7th NVA Division, 8,600 strong, had prepared extensive defensive fortifications along the vital supply route. The NVA easily stopped the 1st Brigade.

A ONE-MAN OPERATIONWith a stalemate occurring, Hollingsworth recommended a mission change: reinforce An Loc with the 1st Airborne Brigade and have the 21st ARVN Division clear QL 13. The paratroopers were needed because on April 13 the NVA kicked off an armor and infantry attack that threatened the town.

Late in the afternoon of April 14, the 6th Airborne Battalion, about 400 paratroopers, conducted a helicopter assault into an LZ near key terrain just south of An Loc. Two American advisers, Maj. Richard J. Morgan and 1st Lt. Ross S. Kelly, accompanied the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Dinh, in the first lift. The high ground, Hill 169 and an adjacent feature called Windy Hill, was needed for an artillery firebase. It would provide support for the 5th ARVN Division because all its guns had been destroyed by incoming fire.

South Vietnamese tanks move up Route 13, 40 miles north of Saigon, toward besieged province capital of An Loc,. (AP Photo)

South Vietnamese tanks move up Route 13, 40 miles north of Saigon, toward besieged province capital of An Loc,. (AP Photo)

Initially, the landing was unopposed. Yet the NVA reacted quickly and stopped the paratroopers from gaining the summits of the two hills. The advisers called in air strikes. Kelly, accompanying attacking troops, directed U.S. Army AH-1G Cobra rocket and machine gun fire to within 25 meters of his position, forcing the enemy to withdraw. It was a “danger close” call, but a necessary one.

As the high ground was taken, Morgan, the senior adviser with the battalion commander, suffered a severe leg wound. He needed immediate evacuation or would bleed to death. Fortunately, a U.S. Army Huey helicopter responded to Kelly’s request for a medevac. The pilots braved enemy mortar and artillery fire to rescue Morgan and five ARVN paratroopers who were also seriously wounded.

Kelly, a 1970 graduate of West Point with less than two years in the Army, was now the lone American responsible for the battalion’s desperately needed air support. The old Army expression “operating way above his pay grade” described Kelly’s circumstances.

The remaining battalions, the 5th, 8th, and 81st, plus the brigade headquarters, arrived on April 15-16. CH-47 Chinook helicopters brought in six 105mm howitzers and emplaced them on the high ground, secured by two rifle companies of the 6th Airborne Battalion. Maj. John Peyton, Morgan’s replacement, was in the airlift and joined Kelly on the afternoon of April 16. Peyton was only on the ground two days before he too was badly wounded and evacuated. Again, Kelly was a one-man operation.

The communists controlled much of An Loc in the early days of the offensive, forcing the South Vietnamese defenders into a small southern sector at the top of this aerial photo. (UPI Photo)

The communists controlled much of An Loc in the early days of the offensive, forcing the South Vietnamese defenders into a small southern sector at the top of this aerial photo. (UPI Photo)

The North Vietnamese commander was not about to allow an ARVN firebase to operate in his area of responsibility. Within 24 hours, NVA artillery fire destroyed all six howitzers and its stockpile of ammunition. The battalions airlifted in on the 15th and 16th were ordered to move into the town and join the 5th ARVN Division defenders who were fending off major NVA attacks. The 6th Airborne Battalion was left on its own. Two NVA regiments with eight tanks began to systematically isolate and destroy the 6th.

Kelly used every air sortie at his disposal to keep the numerically superior foe at bay. The communist commander was determined to annihilate them, regardless of the cost. By April 20, the 6th Battalion had fewer than 150 effective fighters. Seriously injured soldiers died for the lack of medical treatment. U.S. helicopters only flew medevac missions for wounded U.S. advisers—so the evacuation burden fell on the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) helicopter pilots, most of whom were sadly lacking fortitude.

WAITING FOR THE NVASupply shortages and the VNAF’s reluctance to fly caused morale to plummet. Having grown used to the robust support from the U.S. Army, the failure of the ARVN and VNAF to perform critically needed tasks was a shock to the paratroopers, including the battalion commander. Lt. Col. Dinh was psychologically overwhelmed and stayed in his foxhole, almost in a trance. Remnants of two rifle companies on the hills, less than 50 men, were forced off and escaped to An Loc. Eighty other paratroopers, who were not on the high ground, formed a tight perimeter and waited for the NVA.

Route 13 became a battlefield during the assault when U.S. advisers called in B-52 bombers. Here smoke rises from a bomb strike on May 19, 1972, as South Vietnamese troops fought to reach ARVN units and their American advisers farther north. (AP Photo)

Route 13 became a battlefield during the assault when U.S. advisers called in B-52 bombers. Here smoke rises from a bomb strike on May 19, 1972, as South Vietnamese troops fought to reach ARVN units and their American advisers farther north. (AP Photo)

Kelly began to work what little magic he had left. He coordinated with the brigade senior adviser, Lt. Col. Art Taylor, and his deputy, Maj. Jack Todd, for assistance to allow them to break out to the south, away from An Loc. Todd called Kelly at 7:30 p.m. and said three B-52 strikes were scheduled just after dark to hit the concentrations of North Vietnamese threatening the 6th Battalion. U.S. intelligence had a good “fix” on enemy locations. The bombers would drop “danger close,” meaning less than 1,000 meters from the friendlies, the minimum safe distance from B-52 bombs.

Kelly’s cajoling and the news of the upcoming bombing strikes snapped Dinh out of his depressed state. He made the difficult decision to leave the seriously wounded soldiers behind and prepared the men to move. When the first 500-pound bombs began to fall, 80 exhausted men headed to the southeast, away from the enemy. Kelly led while Dinh, farther back in the column, kept the troops moving. The shock of three successive B-52 strikes and rapidity of movement gave the bedraggled force some breathing space.

Throughout the night and into the next day, Kelly continued to serve as “point man” for the small group. On more than one occasion, he called in air strikes on pursuing enemy troops. When Kelly found a suitable pickup zone, the adviser used U.S. air strikes to seal off the area and protect the incoming helicopters.

Finally, VNAF helicopters arrived but they only touched down briefly and several hovered a few feet off the ground, making it impossible for the walking wounded to get aboard. They were not taking any enemy fire. Without warning, they “pulled pitch”—taking off with Kelly hanging on to one UH-1’s struts and leaving 40 soldiers on the ground.

Threats from the battalion commander failed to intimidate the pilots, who refused to land again. Fortunately, the corps commander and Hollingsworth forced the VNAF to return the next day, but they only retrieved half of the 40 men left behind. Those 60 rescued paratroopers became the 6th Airborne Battalion’s nucleus as reconstitution began immediately.

On Oct. 17, 1972, Kelly was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery. Without his personal example, forceful urgings, and timely orchestration of airstrikes, no one would have survived. His actions belied his rank and experience and his professionalism saved the day.

TRIAL BY FIREDuring the 6th Battalion’s ordeal, the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion was undergoing its trial by fire. It was lifted in on April 16, arriving with 450 soldiers and three U.S. advisers: Capt. Charles Huggins, senior adviser; Capt. Albert Brownfield, Huggins’ deputy; and Sgt. First Class Jesse Yearta, light weapons adviser. The unit was detached from the airborne brigade and directed to fight its way into An Loc and occupy positions in the northeastern sector of the town’s perimeter. The NVA had attacked several days earlier and gained a significant lodgment, almost to the center of the town. The communists had nearly reached the east-west thoroughfare that bisected An Loc, leading one American defender to report: “The bastards are almost to Sunset Boulevard.”

As the 81st moved off the LZ, Yearta was hit by artillery shrapnel but refused evacuation. An ARVN medic patched him up. Yearta, a hardcore soldier, continued the mission. At 36, he had come of age in the Cold War army and spent most of his career in airborne units. He was known as a “hard ass,” but the troops held him in high esteem because he was a fighter and genuinely concerned for their welfare. The Airborne Rangers of the 81st had an unbounded affection for Yearta.

On the night of April 22, the battalion was directed to launch a counterattack to eliminate enemy positions. Huggins was provided a Spectre gunship, a USAF AC-130 aircraft equipped with a 105mm cannon and twin 40mm Bofors guns, to assist the attackers. The Spectre had cutting edge technology sensors that allowed it to fire very near friendly forces, almost within the 50- meter bursting radius of the 105mm shells. A rolling barrage was planned with the troops following closely behind it.

A South Vietnamese soldier surveys the damage after the U.S. bombing. (AP photo)

A South Vietnamese soldier surveys the damage after the U.S. bombing. (AP photo)

Yearta volunteered to accompany the lead company so he could direct the Spectre’s fire. Not taking a chance that he might become separated from his radio operator, he carried his own AN-PRC 77 radio so he could maintain constant contact with the airplane. To ensure the Spectre gun crew could track the leading friendlies amid battlefield obscuration, Yearta continually fired small pen flares that the aircraft’s sensors easily identified. He adjusted both the 105mm cannon and the Bofor guns by constantly sending corrections, positioning himself almost within the blast area. The fire was so devastating the NVA was pushed back and original defensive positions were restored.

Later, Yearta was asked about the Spectre’s support that night. He replied in typical fashion, “Damn! They are good ol’ boys.” Yearta became a legend among the advisers for the pen flare episode and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his valor.

The siege of An Loc lasted 66 days and resulted in the destruction of three NVA divisions. It was ironic that the reconstituted 6th Airborne Battalion, still commanded by Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Dinh, broke the enemy’s grip on the town. On June 8, 1972, the 6th Airborne linked with the town’s defenders after fighting its way from the south. In mid-June, President Thieu declared the siege lifted and the 1st Airborne Brigade was sent to the northernmost province of Quang Tri to participate in a counteroffensive.

“THE BATTLE THAT SAVED SAIGON”The 1st Airborne Brigade and the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion paid a heavy price for their part in what some journalists called the “battle that saved Saigon.” From April 7 thru June 21, the 1st Airborne suffered 346 killed in action (KIA), 1,093 wounded, and 66 missing; the 81st lost 61 KIA and 299 wounded.

The An Loc campaign took its toll on MACV Team 162. Nineteen airborne advisers began the operation in April 1972. Of that number, 10 were wounded and one, Sgt. First Class Alberto Ortiz Jr., died from his wounds. He was the first of five airborne advisers killed during the Easter Offensive. One officer, Capt. Ed Donaldson, was wounded on April 7, evacuated, returned to duty in An Loc, and was wounded again, for which he required extended hospitalization.

Five battalion advisers with the 1st Airborne Brigade and the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their actions in An Loc. In addition to Kelly and Yearta, DSCs were awarded to: Capt. Michael E. McDermott, 5th Airborne Battalion; Capt. Charles R. Huggins, 81st Airborne Rangers; and 1st Lt. Winston A.L. Cover, 8th Airborne Battalion. For McDermott, it was his second DSC, the first being presented in 1967 when he was a lieutenant in the 101st Airborne Division. With two DSCs, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart, McDermott became one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam conflict.

Amid the rubble of An Loc, a monument to South Vietnamese soldiers stands almost undamaged on June 14, 1972, toward the end of the costly “battle that saved Saigon”—saved for the time being, at least. (AP Photo)

Amid the rubble of An Loc, a monument to South Vietnamese soldiers stands almost undamaged on June 14, 1972, toward the end of the costly “battle that saved Saigon”—saved for the time being, at least. (AP Photo)

An Loc was destroyed in the Easter Offensive. Only rubble and burned-out communist tanks remained. The town was rebuilt and today commerce flourishes. One would not know that a climactic struggle occurred there five decades ago; there is no evidence of the battle. Several cemeteries are located just south of An Loc where the remains of NVA soldiers are interred. At each cemetery, there is a large statue and plaque dedicated to the heroism and sacrifice of the communist “freedom fighters.”

After South Vietnam surrendered in April 1975, NVA soldiers desecrated the 81st Airborne Ranger cemetery in An Loc that the town’s citizens had meticulously tended to when the 1972 battle ended. Like other ARVN cemeteries, there is no trace of it today.

*****

During the 1972 Easter Offensive, John Howard served as senior adviser with the reconstituted 6th Airborne Battalion and 11th Airborne Battalion. On a 2011 trip to Vietnam, he returned to Tan Khai and An Loc. For further reading he recommends James H. Willbanks’ book, The Battle of An Loc and Dale Andradé’s book America’s Last Vietnam Battle.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of Vietnam magazine.

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

November 11, 2023

Veteran’s Day Special Report from WGN-TV

POSTED 9:00 PM, NOVEMBER 11, 2015 on WGN-TV, BY SARAH JINDRA, UPDATED AT 10:10PM, NOVEMBER 11, 2015

Click below to be redirected to the article and videos http://wgntv.com/2015/11/11/chicagos-welcome-home-to-vietnam-veterans/#ooid=VucWhzeDrfCjzWV-5qdj8f6ILvX2wkWqAbout a decade after the Vietnam War ended, cities across the country began hosting “Welcome Home” parades for Vietnam veterans. while fighting in the trenches of Vietnam, many young Americans saw things they didn’t want to see and did things they didn’t want to do.

The song “We Gotta Get Out of This Place,” by The Animals became their anthem. And they lived for the moment they got to get back on the plane and leave Vietnam.

“Oh my God, we survived. And when the plane took off, we all cheered. It was a big, big thing,” recalls Vietnam veteran, John Podlaski.

Podlaski is one of the lucky soldiers who made it out. He was finally able to take a deep breath and return to the country he served.

But he returned to protests and flag burning, aimed not just at the government for its involvement in the war, but at him too.

“It was a heck of an experience or account,” says Podlaski, “to see the tomatoes coming at you, raising their fists and they’re hollering at you. Everybody was kind of embarrassed. I don’t want to go out and show myself. To become a Vietnam vet, from that point on, it was kind of a secret. You kind of just took it in the closet and left it. You didn’t want anyone to know.”

Radio personality, Bob Leonard felt the same way when he came back from Vietnam.

“When I came home, people started spitting at me and calling me a baby killer,” says Leonard. “By about the 4th or 5th person who said baby killer and spit at me, I had had enough.”

Leonard grew out his hair and moved to Puerto Rico. For the next 16 years, he denied serving in Vietnam, even after moving back to the U.S. But that all changed in Chicago on June 13, 1986.

On that day, Leonard agreed to help host a “Welcome Home” parade for Vietnam veterans. Parade organizers in Chicago found out he was a Vietnam veteran and asked him to help host. He agreed and says that day changed his life.

“Everything changed,” says Leonard. “My whole mindset changed. From that point on, it was OK to be a veteran.”

While some veterans felt the parade was too little too late, 125,000 thought it was just what they needed to finally be thanked and to feel welcome home.

As Leonard hosted, Podlaski marched in the parade. He later wrote a book about his experience in Vietnam to help others understand what they went through. Watching the parade broadcast today is still emotional.

“A lot of people didn’t go,” says Podlaski. “It was 15 years too late. ‘Don’t welcome me home today, because I don’t wanna hear it.’ But for me, I was thrilled to death.”

During the parade broadcast, President Reagan made a statement to those watching, acknowledging the long overdue welcome home. “Clearly the welcome home received by many of our brave men and women who served in Vietnam was less than they deserved. And that’s putting it mildly. Today, however, Americans are making up for that.”

The scars of war, emotional and physical, were on display that day. As was the stark reminder, that some Veterans never even got to choose whether to attend a parade.

For more information on “Cherries,” by John Podlaski: https://cherrieswriter.wordpress.com/

And this is a link to our commercial-free hour-long documentary that aired on most Tribune stations beginning last weekend: http://salutingourvietnamveterans.com/

IF YOU ARE INTERESTED IN VIEWING THE PARADE, SEGMENTS ARE AVAILABLE ON YOUTUBE. HERE’S THE DIRECT LINKS:

PART 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KlOlHExChT8

PART 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9z5QMWVBHLs

PART 3: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uWRUJ0PeZ-w

PART 4: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9OpKzFJqRgU

PART 5: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u8mEG3Ffp7M

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

November 5, 2023

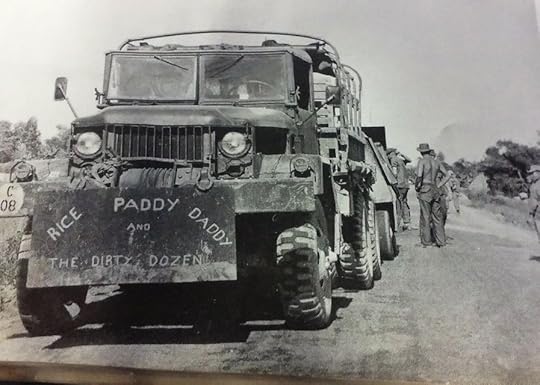

240th Assault Helicopter Company (Greyhounds) Reunion Opening Address

By Richard Toops, Greyhound 16

My friend, Richard Toops, sent me his opening speech from their last reunion. I thought it was great and have to share it with you all!

Well, for those of you who don’t know me…I am Richard Toops, Greyhound 16, and I think by now most of you know my wife, Trenda. We met on a blind date through my secretary when I worked for the Department of Commerce, and the last 47 years have been our happily ever after. We both have been looking forward to this Reunion and being with you all for a long time.

We will be having our Tribute for our 38 brothers on the last night of our Reunion. But tonight, I want to reminisce and have a Tribute of sorts to you brothers who are here tonight. John Podlaski, the man who wrote the Best Selling book “Cherries” said, “Helicopter crews were held in the highest regard and seen as “saviors” by us infantry soldiers…….at times, watching in awe and disbelief while pilots and crew braved enemy onslaughts to transport, rescue, supply, and protect those on the ground. Helicopter Crews were always there when needed – losing many of their own while performing in this role.”

Today I want to talk about our 240TH Assault Helicopter Company and these 3 words…… Brave …..Courageous….and Daring….. that exemplify great attributes. Miriam Webster Dictionary defines the word Brave as, “showing mental strength to face danger.” Courageous, “as firmness of mind and will.” And Daring, willing to seek out risks, bold, fearless, adventuresome”. We were BRAVE……. We were COURAGEOUS…… We were DARING……. Yes, guys, we are a lot of superlatives………the guys in this room all had someone shooting at them, and still did their job, look around your relatives and friends.

We were shot at, shot up, or shot down. In WWII the average battle time for a soldier was 14 days…..14 days believe it or not……Well, In Vietnam it was every single day…(365 days) ..26 times more risk….Every single day LIFE was hanging in the balance. But with all that, we were not concerned about ourselves, we were concerned about our crews, our brothers and our passengers. When one of our own was killed or wounded it broke our very being to the core. We cried, yelled, screamed, cursed, and then got drunk…..All we wanted to do was to try and forget for a while then get back out there and avenge our brothers.

We saw death more times than we care to remember. We saw death on both sides……… we experienced the enemy shooting at us, and by the grace of God did not get killed ourselves…. Some in this room crash landed in the jungle and waited to be rescued for what seemed like forever, while the bad guys continued trying to kill us. We had Engine failures, tail rotor failures, We had high freeks and low freeks, helicopter fires, hydraulic failures, and had to make running landings…………… We saw our buddies wounded, and heard them……screaming in agonizing pain, and saw them die in front of us. Death was with us every day.

Remember what it was like to fly ammo to a surrounded unit of the 25th Division and then hover above the trees, dumping the ammo boxes below as quickly as we could while we hunkered behind our chicken plates, or slide armor plates, trying to dodge bullets?

How about life and death choices we had to make, like flying a couple of Special Forces at the end of a ladder several miles in War Zone D because they were being shot at and there was no time to let them climb up the ladders into the helicopter.

At times we tried to fly with a NOGO WARNING. For those of you here that don’t know what NOGO is..NOGO means NOGO. (that’s a gauge on our instrument panel that said don’t go, your load is too heavy and crashing will be imminent). I remember one time we had 20 South Vietnamese troops aboard and we were trying to get them out of the bush at NHE BHE before the tides came in. Our NOGO was on. There was a single tree right in our path as we desperately tried to get enough lift to get up and over. We did… just grazing the top of the trees.

These are all true stories…and there are so many more I could talk about. Death, wounds, and more. Mentally and physically are just words now, but back then, they described our normal daily life in Vietnam. We were all so much younger then and could cope with it……. We made everyone think it anyway…. And I will say, when not flying, most of us did have fun. When we were not flying, we were a bunch of fun-loving guys, enjoying what we did. We Played cards till midnight, poker, hearts, and spades. We Told a lot of stories of our stateside adventures before Nam. (some true, some I questioned.) We drank a lot of Pabst Blue Ribbon, probably too much. But it made things we faced and dealt with, easier.

How many of you, after having a few drinks because you were not flying the next day, were woken up at 5 a.m. the next day and told you were flying? Headache City…I remember one time being the OD, “Officer of the Day”, and waking someone up in the morning to go fly only to get a 38 pointed at my face? In time we all knew who the guys were to be careful around. Then in the evening one of our guys would get his guitar out and we would sing late into the night. Bill Seaborn was the guitar playing/singer during our time. We were…….. a fun bunch. I would like to think I am still that young man in Vietnam but now I know as of three months ago, I am not…..I want to be that guy again, but I am not him…

We live on Cedar Creek Lake in Texas and this summer I was standing out on our dock at our house, and decided I would jump off the dock and into the water as my daughter and granddaughter had been doing for the 10th time this particular day. As I stood on our dock, I looked into the water, (which was only a foot or two below where I stood). The water was calm, and it looked refreshing, I started to jump, but suddenly I froze with the fear of jumping. My heart was beating fast and I was close to an anxiety attack……Simply put….I was scared of jumping into the water……..WHY?….WHY was I feeling this way? that which I had done all my life and most of the 30 years we had lived on the lake. Life and its fragile strings had caught up to me…… I was no longer a young Greyhound pup in Vietnam, but an old Greyhound ……dog… I was afraid,….. fearful…….I was embarrassed to even feel this way. I eventually told myself, afraid or not, I would jump, and jump I did. As I flew through the air I felt sick inside, I was still afraid. I hit the water and told myself I had made my last jump. I could not rid myself of the fear. Even in the days I spent in Vietnam except twice, I was never so fearful…Sometimes because we are Vietnam vets, people look at us and think we are big brave guys who are not afraid of anything. Well,….. I am not that…To be perfectly honest, I am just an old guy who is afraid to jump in the water. What had happened?….What happened to me? Fear…We all dealt with it in Vietnam, but we were younger then.

What is fear?….. It’s just being scared of something, which we younger Greyhounds realized and dealt with. Just like in Vietnam. Each of you out there handled fear over and over again. We were only concerned about our mission, but eventually fear grabbed us when we did not expect it. The rest of the time we were not concerned about fear, we had a job to do and that consumed our thoughts and our actions. We just went out every day doing our job.

Back to my original statement. Were we Brave, Courageous, and Daring? Heck yes, we were. Did we flaunt our superpowers to all, you bet! After all, we were the masters of the sky. We know among ourselves that we were all these things, whether anyone else accepted it or not…We were Brave, we were Courageous and we were Daring. ….. And best of all, we are still…….that bunch of fun-loving guys, but we have changed…..we are older now. We are no longer as indestructible as we once thought, now to keep us going, we need rest, we need pills, Dr visits, and hospital stays. …..we walk a bit slower, well maybe a lot slower…We are grumpy, ask our wives……We get tired, have aches and pains, and sometimes we don’t want to do anything. But guys, I know we are still who we were……. In our hearts and minds, we are still those Brave, Courageous, and Daring Soldiers of yesteryear.

I look out….I don’t see a bunch of old guys, I see Door Gunners, Crew Chiefs, and Pilots. One, our Door gunner, Buster Barker, (standup Buster) along with God saved my life. Buster, although severely wounded himself, under hostile fire, pulled Bill Seaborn and me out of a shot-down Huey in a Vietcong Basecamp before our Huey was hit again with 2 RPG rounds as it lay on the jungle floor……

This is what 240th door gunners do, they protect us, our Huey, and everyone else in it. Please stand up all you door gunners out there. (Clap).

When I looked out there, I do not see a bunch of old guys, I see our Crew Chiefs…….and folks these back seat guys breathed the life in our Hueys, every single day and at times, late into the night….they were getting our ships ready to fly. Will Rogers said he never met a man he didn’t like, well we pilots never met a crew chief we didn’t like. If we were flying it was because of the Crew Chief. During the missions, they flew with us and manned an M-60 Machine gun. When we were shot down, Jimmy Lance, our Crew Chief, (who is not here tonight) while severely injured…., and under hostile fire, crawled back in our Huey and shut it down to prevent a fire. and then helped Buster in getting Bill and me out of the Huey. (Stand up Crew Chiefs). (Clap)

When I look out there I don’t see a bunch of old guys, I see our pilots, ….The best America ever had..All flying for the mission, no matter what came their way; hot LZ, cold LZ, taking fire or not, it did not matter, mission first. Always going to finish the job. NO, was never an option. Our Aircraft Commander that day when we were shot down, Bill Seaborn, was my friend, he asked me to do something I had not done in months, wear my Chicken Plate on my chest, not under me as I had done for almost 6 months, I did not have to wear it but he was my friend and I listened, I feel like doing what Bill asked me to do that day also saved my life………… I am proud to be one of the pilots in this room.….Stand up guys….(Clap)…

The 240th Greyhounds…….We could go into a Pickup Zone or Landing Zone, not knowing what was there but ready to do our jobs. That’s brave. We could take fire From the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese Soldiers and shoot back with adrenaline flowing, that’s courageous. We could go into the firestorm of bullets and attempt to rescue our fellow soldiers, now that was absolutely daring.

We were everything that can be said about helicopter crews and more. Did we ask for it? Yes, we all volunteered for it. Did we expect any praise, no….we wanted it though if just for us…so we could feel needed…. feel like somebody special… But most of all we wanted it from our fellow crew members, and we got it tenfold. We channeled each and every move we made for us and our guys, our unit…..our brothers……in Vietnam we knew we only needed each other to survive…. All of us have a special bond.

No one will ever understand, except us. Not the world, not the civilians of the world. This is why these reunions are so important to us. Be proud of what you did guys, we were all these things. Everyone of You out there…..we were all Brave, Courageous and Daring…….you Know….. It’s great to be humble…. but all you relatives out there, these guys were heroes…the real deal….and always will be.

Guys, we can go back to eating humble pie when we leave Branson……but today, and during this reunion, we will relish who we were……. What we did……. Who we helped…….and who we saved. We were Brave, Courageous, and Daring………Flying through the skies of hell and back, all this from a base in Vietnam called Bearcat.

Be proud,……..you were the backbone and workhorse of the Vietnam War. Now…….going Back to my fearful water jump. I had fear as I looked in that water, I still do…but I am old now….but,…..I am so glad that when I look back on Vietnam I can be happy in knowing I could harness that fear like all of you did and do those Brave, Courageous, and Daring things that made us Greyhounds and MadDogs, and Kennel Keepers.

In wrapping up…. Friends……and Relatives out there, When these guys step on some dock and don’t jump in the water, just remember the days when they did even more dangerous things and didn’t bat an eye. When one of our guys was wounded which totaled several hundred guys during our 240th existence, we got mad and our hearts were wounded…… When one of our 38 who were killed, POW or MIA, ……… a part of us was lost forever on the battlefield, …..never to return.

Through it all we grieved, cried, cursed……in the end, they were still gone. We picked ourselves up and continued on, doing what we loved doing. Flying….yes but most of all still being Brave, ….Courageous ….and Daring …..in a helicopter called Huey.

Be proud of being a Greyhound, Maddog, and Kennel Keeper. We were………. and always will be the best to have ever flown……no questions about it….You, my fellow brothers, have earned it, and you deserve it.