John Podlaski's Blog

October 18, 2025

Before he was a hero on 9/11, he was a hero in Vietnam

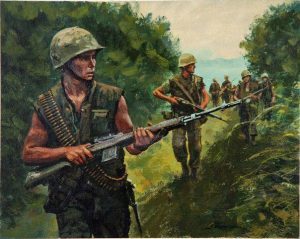

Photo: U.S. Army 2nd Lt. R.C. Rescorla, Platoon Leader of 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division – Ia Drang Valley, South Vietnam. November 16, 1965.

My friend, Donald Healy, shared this post on LinkedIn with me. Many of you are already familiar with this story, while for others, it may be a first. It’s never too late to honor our heroes!

By Robert Batemen

Rick Rescorla knew his history. The native of England knew how stories of the past, recent or distant, could move people. Be it the English victory at Agincourt in 1415 or the British victory at Rorke’s Drift in the Zulu War of 1879, his tales of individuals surmounting incredible odds could lift people that last small bit to keep fighting. To survive. To win. He wrote and sang songs to puff up morale and calm nerves. We know because his singing was captured on a reel-to-reel tape in a ramshackle officers club at the U.S. base at An Khe in 1966. The percussion heard on the recording was outgoing harassment and interdiction fire.

It is almost 60 years now since Rick showed his courage at Ia Drang, where the U.S. Army waged its first big battle with North Vietnamese troops, and exactly 24 years since he braved the fire in New York when the city was hit by the deadliest terrorist attack in history.

On 9/11 Rick died doing what he did best: rallying the troops — the employees of Morgan Stanley Dean Witter at the World Trade Center. When Tower Two collapsed around him at 9:59 a.m., 73 minutes after the first plane flew into the Twin Towers, Rick, head of security at the largest financial institution in the building, had already sped the evacuation of more than 2,000 employees. Only three had not safely exited, and he was going back in to get them.

Thousands of civilians in New York lived because of Rick, just as soldiers in Ia Drang lived because of him.

Rick was in Vietnam at the beginning of combat operations in 1965, just as he was in New York at the start of another war in 2001. The children of those saved by Rick will pass the story on to their own children, and Rick’s memory will be preserved.

My first memory of Cyril “Rick” Rescorla is at a reunion of Ia Drang veterans in 1996. I was a young captain, commanding a company in the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, at Fort Hood, Texas, and being invited to this reunion was a great honor. Rick was one of the most famous veterans of our battalion. When retired Lt. Gen. Hal Moore, who as a lieutenant colonel commanded the 1st Battalion of the 7th at Ia Drang, says a man is “the best combat platoon leader I ever saw,” that sort of thing rather sticks. Induction into the Officer Candidate School Hall of Fame is another point toward immortality.

The November 1965 fighting at Landing Zones X-Ray and Albany in the Ia Drang Valley immediately became front-page news because of the high casualty rate. Both formally and informally, the battles profoundly affected the ways American forces would fight throughout the rest of the war. It validated the concept of “air assault” (transporting troops to the battlefield in helicopters), which then became the overarching American tactical concept for the use of infantry in Vietnam.

The dual battles at Ia Drang were immortalized by Gen. Moore and my friend journalist Joe Galloway, who was on the ground from day one, in their 1992 book We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, which become a New York Times bestseller. On the book’s cover is a photo of Rick taken by Associated Press journalist Peter Arnett, who also covered the battle.

Heroism at Ia DrangRescorla, born in Hayle, Cornwall, England, served in the British Army, then became a member of the Rhodesian paramilitary police and later joined the U.S. Army to help fight the Communists in Southeast Asia. After Officer Candidate School, he was assigned to the 7th Cavalry Regiment and led the men of 1st Platoon, Bravo Company, 2nd Battalion.

On Nov. 14, 1965, Moore’s 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, air-assaulted into the remote Ia Drang Valley, less than 10 miles from the Cambodian border. The troop drop stirred up a hornets’ nest. Hours later, Lt. Rescorla’s Bravo Company was ordered to the center of that area to support Moore’s battalion. Moore’s men were surrounded by more than 2,000 soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army.

As Rescorla’s troops landed at LZ X-Ray, the lieutenant ordered his men to set up a new defensive perimeter, 50 yards behind the previous one, and dig deep foxholes. They rigged grenades and booby traps in front of them. They carefully emplaced their machine guns and piled up ammunition.

Then they waited overnight. Rescorla sang songs to steady the men. At 0400, grenades and booby traps began to erupt in front of Bravo, but the company was primed. The NVA assaulted four times, attacking in human waves. In the first rush, an attack by as many as 300 NVA was stopped cold.

Around 0630, the North Vietnamese launched a heavier attack. Rescorla and his men continued to pump rounds into the clumps of bodies nearest their holes. At 0655 they commenced a “mad minute” of firing. Ultimately, the 2½ hour predawn attack failed.

In daylight, Rescorla took a patrol through the silenced battlefield, policing up the area. After his men left the perimeter, they came under heavy machine-gun fire, and Rescorla gave the command “Fix bayonets!” Arnett just happened to be nearby and snapped the photo that would become a book cover. Rescorla lobbed a grenade at an enemy gunner and wiped out a nest of NVA.

On Nov. 17, the rest of the 2nd Battalion, which had arrived on foot, began a tactical march to a new landing zone, Albany, for a helicopter pickup. On the march, the battalion came under another NVA attack, and Rick’s platoon was again deployed in relief. Rick, the sole remaining officer platoon leader in Bravo Company, led the initial reinforcement into the Albany perimeter

“We Were Soldiers”As the helicopter carrying Rick descended into Albany under heavy fire, the pilot was hit and started to lift up. Rick and his men jumped the remaining 10 feet, bullets flying at them, and made it into the beleaguered perimeter.

Leading 1st Platoon, Rick yelled, “Come on, let’s let them have it!” according to Lt. Larry Gwin, whose book Baptism recounts the same events.

“I saw Rick Rescorla come swaggering into our lines with a smile on his face, an M-79 on his shoulder, his M-16 in one hand, saying: “Good, good, good! I hope they hit us with everything they got tonight — we’ll wipe them up,” Gwin wrote. “His spirit was catching. The troops were cheering as each load came in, and we really raised a racket. The enemy must have thought that an entire battalion was coming to help us because of all our screaming and yelling.” But it was just Rescorla and a few of his men.

Dozens of wounded Americans lay at Albany, awaiting medevacs throughout the night. Brave aviators risked everything for the wounded in Albany. Rick, inside the perimeter, disciplined the men, admonishing no more firing. “As dawn broke over the Albany battlefield on Friday, November 18, a profound shock awaited the Americans who had survived the night,” wrote Moore and Galloway in We Were Soldiers Once…and Young. “To this point no one had a clear picture of the extent of the losses suffered by the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry…. Rescorla described the scene as a “long, bloody traffic accident in the jungle.”

In the movie We Were Soldiers, based on the book, Moore went outside the perimeter, found the body of one of his lieutenants and brought it back. That part was true. Moore would bring every man out. But the part about Moore finding an NVA bugle was not true. It was Rick who found that bugle on a dying enemy soldier forward of his lines during a sweep at LZ Albany.

“We returned to [Camp] Holloway and for a while we were buoyed up with the fact that we had survived,” Rick said. “All gloomy memories were shoved below the surface.” The bugle can still be seen at the infantry museum at Fort Benning.

After those two swirling fights, in which Rescorla’s men defeated forces estimated at five or six times their own size, company commander Capt. Myron Diduryk approached the lieutenant and asked him (not told, asked) if he would mind if the entire company adopted the nickname of Rick’s 1st Platoon, “Hard Corps.” Thus Rick, whose radio call sign in the platoon was One-Six, became “Hard Corps One-Six” on the company and battalion networks.

There is no easy or simple way to describe the life of Rick Rescorla. The men who knew the 26-year-old second lieutenant in Vietnam mostly knew him for only a year and then did not see him for decades. Those who knew him longer offer a host of descriptions: poet, romantic, playwright, a man truly addicted to song, academic, intellectual, raconteur, Cornishman, dedicated father, a man known for his fierce loyalty to those he felt deserved it, whether superiors, peers or subordinates.

Everyone who knew Rick, regardless of what they remembered about him, could agree on one thing: Rick Rescorla was, always, the baddest son of a bitch in the valley.

Following his tour in Vietnam, Rescorla spent a year teaching at Fort Benning in Georgia and then got out of the Army — sort of. He joined the Army Reserve, advancing to colonel before he retired in 1990. Along the way, Rick picked up a master’s degree and a law degree. In 1985, he took a corporate security position with Dean Witter.

At the Ia Drang reunion in ’96, I had mostly tried to keep my mouth shut and let the veterans of combat talk to each other. But Rick was having none of that. Drawing me out, he learned of my own inclinations: history, academia, writing, even acting, all very nontraditional for your standard airborne infantry Ranger. As one who aspired to someday become a historian, I sat and had a good scotch while he told me his stories, which I was writing down in an untutored oral-history kind of way. Later, I asked him to inscribe my copy of We Were Soldiers Once…and Young.

Rick ordered a fresh glass of single-malt scotch, took my book, borrowed my pen and walked over to the other side of the room where he sat, facing away, seemingly looking into the distance…though the distance was a wall just a few feet away.

Leadership in ActionThe secret to Rick’s successes, in battle and in life, was his instinctive ability to be a leader. And like the best leaders, it was not because of any military rank he ever wore, in the British Army, the Rhodesian paramilitary police or the U.S. Army. He was a leader because he understood men. He knew, in his bones, what some who reach far higher ranks never do learn.

What he knew is simple: When things drop in the pot, when lives are at stake and the danger is real, people want to believe that the one they are following is something more than they are themselves. Smarter. Stronger. Not as afraid as they are at that moment. Rick, adept at suppressing his own fear when it mattered, inspired other men to greatness. When he entered the maelstrom, his people followed.

After terrorist hijackers flew a plane into Tower One of the World Trade Center on 9/11, Rick was told by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which managed the towers, to “shelter in place.” Rick replied, “Bugger that!” (a very, very…very impolite term when used by a Brit) and initiated an evacuation of his entire company. In other places chaos reigned, but not where Rick was in command.

Rick had been training employees for such an attack since 1993, when a truck bomb exploded in the structure’s basement. Even before then, Rick had realized the building’s allure as a target for terrorists. In 1990, he had arranged a meeting with a security official at the port authority to discuss the building’s vulnerability, but the authority didn’t take any action, according to a New Yorker story in 2002.

In the 1993 attack, Rick safely evacuated all of his company’s employees from the building. He immediately began pushing to beef up security at Dean Witter, which merged with Morgan Stanley in 1997. He recommended fail-safe lighting and smoke extractors and made sure that they were installed in the emergency stairwells. Employees had to go through regular evacuation drills, in an orderly and organized way. Rick got that much past corporate.

In 2001, Rick’s office was on the 44th floor. His company had more than 2,000 employees on 22 floors, and as always, Rick felt responsible for each one of them. Two by two, just as he had trained them, the employees of Dean Witter Morgan Stanley exited down the stairwells.

Here is a number: 2,684. That was the number of employees that Rick successfully evacuated. That does not include the thousands of others who made it down those stairwells because Rick coordinated a professional, disciplined and military-like evacuation of his people. Those additional numbers will never be known.

But Rick knew that three employees were unaccounted for and he went back in for them. Rick was last seen on the 10th floor, heading up. He would leave nobody behind.

The last time I saw himThe last time I saw Rick was earlier in 2001, when I was teaching military history at West Point. Gen. Moore had been invited to address the cadets in the military history courses, and the department turned to me for advice on what to give him as a memento. They knew Moore was writing the introduction to my next book and that he was the honorary colonel of my regiment. What do you give the man who has everything?

I knew that Rick lived in New Jersey and worked in Manhattan, about 50 miles from West Point. I also knew that Rick was a rare attendee at the regiment’s reunions, which are held every year.

He came to see friends, but he was really fairly reluctant to drop into the “old soldier” mode and retell stories long rehashed. He had only seen Moore a few times since Vietnam. I knew this, and I knew Rick had been fighting cancer. I got on the phone and invited Rick and his new wife, Susan, to West Point for Moore’s address to the cadets.

When the day arrived, we planned a small dinner, just 12 people or so, on post at the Hotel Thayer, before the West Point ceremony. When Rick and Susan came in, which was a surprise to Moore, I watched as confusion, recognition and joy flashed in quick succession across the general’s face. Later, at the ceremony, Moore gave the assembled cadets his wisdom about war. These cadets, who would be lieutenants, then captains, then majors, soaked it up.

Rick and Susan were sitting in the front row. I had not realized, until Rick explained to me later, that Susan knew little of his military story at the time. They had met only a few years earlier. Both divorcees, they found something in each other that worked and had married just a year before. And since Rick had retired from the Army Reserves in 1990, there really was no reason for him to say much about that part of his past. So he never did.

He never mentioned the bestselling book, the Peter Arnett photo, the movie. To Susan, her Rick was the head of security at a major investment thingamabob. He had a soul with a sense of humor miles deep. Soldier? No, that was just something he once did sort of casually.

Susan wondered why this West Point event was such a big deal. In addition to the thousand cadets, the faculty had come out in force, and the crowd far exceeded the seating room of the capacious auditorium. Moore talked about war. Not nice platitudes, but the dirty bits that we usually don’t talk about. How to take normal, decent, young American boys into hell, and then out of it, alive. Moore never did mince his words.

At the end of his address, Moore said something that stunned Susan: “And now I want to introduce you to the best combat leader I ever saw, Rick Rescorla, Hard Corps One-Six, 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry.”

The foundations shook as the cadets and the officers and every single person who could cram into Eisenhower Hall that night leapt to their feet in the sort of applause that makes “thunderous” an entirely inadequate word. Rick stood up.

He just gave a short wave and sat down again.

Susan was awestruck. That was her Rick. Her goofball. Her poet and romantic. Always surprising.

“Head For the Storm,” he wroteI look back on the Ia Drang reunion of 1996, when I first met Rick and he autographed my copy of We Were Soldiers Once…and Young. He returned the book to me after several minutes of reflection; the scotch he had poured was mostly gone. Later, discreetly, I looked at the inscription:

To: Captain Bob Bateman

Old Dogs and Wild Geese are Fighting

Head for the Storm, As you faced it Before

For where there is the Seventh, There’s Bound to be Fighting

And when there’s no Fighting, It’s the Seventh no More

Best Regards,

Rick Rescorla, Hard Corps One-Six

A poet, as always. And as always, much more. After Rick’s death, his memory inspired me to compose an ode of my own for him:

So after you read this, Get your canteen cup

And fill it with mead, or scotch or rotgut

Then pour it right out, on the ground, on the floor

For the heart of the Seventh, Rescorla’s no more

This article was published on the Military Times website on 9/11/25. Here is the link: https://www.militarytimes.com/veterans/military-history/2025/09/11/before-he-was-a-hero-on-911-he-was-a-hero-in-vietnam/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update appears on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

October 11, 2025

19 Brutal Realities Soldiers Faced in the Jungles of Vietnam

@Back in Time Today

By Samuel Cole

The Vietnam War thrust American soldiers into one of the most challenging battlefields in military history. From 1955 to 1975, troops battled not only enemy forces but also the unforgiving jungle environment itself. The physical and psychological toll was immense, creating challenges unlike any war before it. These 19 realities paint a vivid picture of what our soldiers endured in those distant, dangerous jungles.

1. Constant Humidity That Rotted Everything © CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website

© CherriesWriter – Vietnam War websiteSoldiers’ bodies never fully dried in Vietnam’s oppressive jungle climate. Humidity levels regularly exceeded 90%, creating the perfect breeding ground for fungal infections that attacked feet, groins, and armpits.

Weapons rusted overnight despite constant cleaning. Clothing rotted on soldiers’ backs, and leather boots disintegrated after just weeks in the field. Food spoiled quickly, and ammunition had to be wiped down daily.

The moisture seeped into everything – radios failed, maps dissolved, and morale deteriorated as troops fought a losing battle against nature itself.

2. Leeches Dropping From Trees © Newsweek

© NewsweekBlood-sucking leeches became an everyday horror for jungle patrols. These parasites would fall from overhead vegetation or lurk in streams, attaching themselves to any exposed skin without warning. Soldiers learned to check their bodies constantly, especially after wading through water.

Removing them improperly caused infection, as their heads could break off under the skin. Veterans recall burning them with cigarettes or using salt packets from rations to force them to detach.

Some men reported pulling dozens from their bodies after a single day’s march, each leaving behind wounds that could become infected in the tropical climate.

3. Booby Traps Around Every Corner © Reddit

© RedditThe Viet Cong transformed the jungle into a deadly obstacle course with ingenious and terrifying traps. Punji sticks – sharpened bamboo stakes smeared with excrement – waited in hidden pits to impale unwary soldiers. The contaminated tips almost guaranteed infection.

Trip wires triggered explosives fashioned from unexploded American bombs or grenades. Some traps used bent saplings that, when triggered, would swing nail-studded boards into patrol paths at chest or face level.

Walking point (first in line) was considered one of the most dangerous jobs, with point men often having the shortest life expectancy in a unit.

4. Venomous Snakes Hiding Everywhere © Bird Watching HQ

© Bird Watching HQVietnam’s jungles housed over 140 snake species, dozens deadly venomous. The bamboo pit viper, nicknamed “three-step snake,” earned its name from the belief that victims could only take three steps before dying from its potent venom.

King cobras, growing up to 18 feet long, could deliver enough venom to kill an elephant. Soldiers slept with extreme caution, often keeping boots on and checking sleeping bags thoroughly.

Medics carried antivenin, but in remote areas, snake bites often proved fatal before evacuation was possible. Many units reported more casualties from wildlife encounters than from enemy contact during certain operations.

5. Relentless Mosquitoes Carrying Disease © History Collection

© History CollectionMosquitoes swarmed by the millions in Vietnam’s wetlands, making life miserable around the clock. Beyond the maddening buzz and constant itching, these insects carried deadly diseases like malaria, dengue fever, and Japanese encephalitis.

Malaria alone affected over 40,000 American troops during the conflict despite preventative medications. Soldiers slathered themselves with military-issued repellent containing high concentrations of DEET, which irritated skin but provided limited protection.

Mosquito nets became precious commodities, though using them while on patrol was impossible. Many veterans recall the psychological torture of lying awake, listening to the endless whine of mosquitoes waiting to strike.

6. Monsoon Rains That Never Seemed to End © PennLive.com

© PennLive.comFor months each year, monsoon seasons transformed the battlefield into a waterlogged nightmare. Torrential downpours could dump 12 inches of rain in a single day, turning jungle paths into knee-deep mud rivers and filling foxholes with water.

Operations slowed to a crawl as helicopters couldn’t fly in the storms and visibility dropped to near zero. Soldiers developed immersion foot (trench foot) from constantly wet conditions, causing painful skin deterioration that could lead to amputation if untreated.

The psychological impact was equally devastating – the constant drumming of rain on helmet and jungle canopy drove some men to breaking points during extended patrols.

7. Invisible Enemy Using Guerrilla Tactics © Chris Burgess – Medium

© Chris Burgess – MediumAmerican soldiers trained for conventional warfare found themselves battling phantoms. Viet Cong fighters melted into the jungle after ambushes, leaving bewildered troops firing at shadows.

The enemy used underground tunnel networks spanning hundreds of miles to appear and disappear at will. These narrow passages, barely wide enough for small-framed Vietnamese fighters, contained hospitals, sleeping quarters, and weapon caches.

Specialized “tunnel rats” – usually smaller soldiers armed only with pistols and flashlights – volunteered for the terrifying job of clearing these dark labyrinths. The psychological strain of fighting an enemy who seemed to materialize from nowhere created constant anxiety among troops.

8. Immense Heat That Drained Strength © Grunge

© GrungeDaytime temperatures regularly soared above 100°F with humidity making it feel even hotter. Soldiers carrying 70+ pounds of equipment suffered heat exhaustion and heatstroke during long patrols, sometimes requiring emergency evacuation.

Water discipline became critical, with men rationing limited supplies while their bodies demanded more. Some patrols required three gallons per man daily just to prevent dehydration, an impossible amount to carry.

The heat turned simple tasks into exhausting ordeals. Men lost 10-15 pounds in their first weeks in-country as their bodies struggled to adapt to the punishing climate while maintaining combat readiness.

9. Devastating Psychological Toll © Kent Stolt – Medium

© Kent Stolt – MediumThe jungle environment created a perfect breeding ground for psychological breakdown. The constant threat of ambush, booby traps, and wildlife dangers kept soldiers in a perpetual state of hypervigilance that drained mental reserves.

Sleep deprivation compounded these effects. Many men developed thousand-yard stares – a blank, unfocused gaze indicating severe psychological trauma – after extended combat tours.

Unlike previous wars with clear front lines, Vietnam offered no safe zones where soldiers could truly relax. The knowledge that danger could come from any direction at any moment created anxiety disorders that many veterans still battle decades later.

10. Insects That Invaded Everything © War History Online

© War History OnlineBeyond mosquitoes, Vietnam’s jungles teemed with insects that made life miserable. Fire ants swarmed over sleeping soldiers, delivering painful bites that caused welts and allergic reactions. Giant centipedes with venomous bites hid in boots and equipment.

Enormous spiders, some with leg spans exceeding 6 inches, dropped from trees onto unsuspecting troops. Termites and beetles devoured wooden rifle stocks and equipment.

Most maddening were the tiny biting midges that could penetrate standard mosquito netting. These insects were so small that repellent proved ineffective, leaving men with clusters of itchy welts that frequently became infected in the humid conditions.

11. Contaminated Water Sources © New York Daily News

© New York Daily NewsFinding safe drinking water became a constant struggle in Vietnam’s jungles. Streams and rivers carried parasites, bacteria, and chemical contaminants that caused severe intestinal illnesses. Soldiers often had to choose between dehydration or risking dysentery.

Water purification tablets gave water a chemical taste that many couldn’t stomach, leading some men to drink untreated water out of desperation. This frequently resulted in painful bouts of diarrhea that weakened troops during critical operations.

Some veterans recall filtering water through t-shirts to remove visible parasites before adding purification tablets – a crude but necessary measure when supplies ran low during extended patrols.

12. Flesh-Eating Bacteria and Infections © Grunge

© GrungeMinor cuts and scrapes quickly turned life-threatening in Vietnam’s bacteria-rich environment. Jungle ulcers – painful, expanding infections that ate away flesh – developed from the smallest injuries. Without prompt medical attention, these infections could reach bone or cause sepsis.

Antibiotics became as valuable as ammunition on long patrols. Medics fought constant battles against tropical diseases that had no counterparts in American medicine.

The combination of constant moisture, heat, and abundant microorganisms meant that even properly dressed wounds often festered. Many soldiers carried extra socks not just for comfort but because foot infections could render a man unable to walk within days.

13. Dense Vegetation Limiting Visibility

The jungle canopy created a perpetual twilight even at midday, with visibility often limited to just a few yards. Triple-canopy forests blocked sunlight completely in some areas, forcing soldiers to use flashlights during daylight hours.

Moving through dense undergrowth required machetes to clear paths, slowing movement to a crawl and announcing positions to nearby enemies. The limited visibility created perfect conditions for ambushes and made it nearly impossible to spot booby traps before triggering them.

Calling in air support proved difficult when troops couldn’t see landmarks or even the sky. Many soldiers developed claustrophobia from the constant feeling of being enclosed by the suffocating vegetation.

14. Disorienting Jungle Sounds © AUSA

© AUSAThe cacophony of wildlife created a sonic battlefield that challenged soldiers’ sanity. Nights brought deafening choruses of insects and frogs that could mask the sounds of approaching enemies. Troops struggled to distinguish between natural jungle noises and human movement.

Monkeys screeching overhead sometimes mimicked human screams, causing false alarms and frayed nerves. The constant background noise made communication difficult, with hand signals replacing verbal commands on many patrols.

Some veterans report that the sudden, unnatural silence when wildlife detected danger became the most terrifying sound of all – an almost certain indicator that enemy forces were nearby.

15. Inadequate Equipment for Jungle Warfare © Pew Pew Tactical

© Pew Pew TacticalEarly in the conflict, American troops arrived with equipment designed for European battlefields, not tropical jungles. Standard-issue boots fell apart in wet conditions, and heavy cotton uniforms took days to dry when soaked.

M16 rifles initially jammed frequently in muddy conditions, leading to fatal consequences during firefights. Soldiers often carried captured AK-47s, which proved more reliable in jungle environments.

Radio equipment struggled in humid conditions and dense vegetation limited range. Many units improvised solutions – wrapping equipment in plastic, modifying uniform items, and developing unofficial gear protocols that contradicted official military guidelines but kept them alive.

16. Endless Mud That Swallowed Everything © Reddit

© RedditVietnam’s jungles featured a particularly sticky clay mud that clung to everything it touched. During monsoon seasons, this mud could reach thigh-deep on jungle paths, making each step an exhausting struggle that burned precious calories and energy.

Vehicles became hopelessly stuck, forcing troops to abandon mechanical transport and proceed on foot. The mud’s suction could literally pull boots off soldiers’ feet during marches.

Beyond the physical challenge, the constant mud created psychological fatigue as men gave up hope of ever feeling clean or dry. Veterans often cite the mud as one of their most vivid and unpleasant memories of the war.

17. Limited Medical Evacuation Options © Task & Purpose

© Task & PurposeWhen soldiers were wounded in dense jungle, reaching medical care became a life-or-death race against time. Helicopter evacuations required clearing landing zones by cutting down trees – a process that could take hours while casualties bled out.

In many areas, wounded men had to be carried for miles through hostile territory before reaching extraction points. The physical toll of carrying stretchers through jungle terrain exhausted even the strongest soldiers.

During poor weather conditions, medevac helicopters couldn’t fly at all, forcing field medics to perform emergency procedures with limited supplies. Many veterans recall the haunting sound of wounded comrades calling for medics in areas too dangerous for immediate evacuation.

18. Exhausting Physical Demands © Grunge

© GrungeSoldiers in Vietnam carried loads exceeding 70 pounds while navigating some of the world’s most challenging terrain. The physical toll was immense – climbing steep jungle-covered mountains in sweltering heat while remaining alert for enemy contact.

A typical infantry load included weapon, ammunition, grenades, mines, food rations for several days, entrenching tool, poncho, canteens, first aid supplies, and communications equipment. Some men lost up to 30% of their body weight during extended operations.

The energy demands were so high that the military increased standard rations to 3,600 calories daily – still insufficient for the workload. Many veterans describe the constant physical exhaustion as their most persistent memory.

19. Isolation From the Outside World © CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website

© CherriesWriter – Vietnam War websiteDeployed deep in remote jungles, many soldiers went weeks or months without contact from home. Mail delivery to forward bases was unreliable, with letters often arriving in bundles after long delays or not at all.

The psychological impact of this isolation proved devastating. Men missed births of children, deaths of family members, and important life events, creating a disconnection from their previous lives.

News from America came through Armed Forces Radio or heavily censored military newspapers, offering limited perspective on the growing antiwar movement. Many soldiers describe feeling they were fighting in a different universe, completely cut off from the world they were supposedly defending.

Can you add to this list? Leave a comment below.

*****

This article originally appeared on the Back in time today website on October 10, 2025. Here’s the direct link: https://backintimetoday.com/19-brutal-realities-soldiers-faced-in-the-jungles-of-vietnam/

If you want to read more about what soldiers faced in Vietnam, then check out this earlier post: https://cherrieswriter.com/2017/04/26/mother-nature-vs-the-infantry-soldier-in-vietnam/

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

October 4, 2025

The Hanoi Pick-up you Didn’t Hear About

I apologize for the format of this post. I recently found it in a format that I couldn’t convert to properly copy to this website. I hope it wasn’t much of an inconvenience, and you were able to finish the story.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 27, 2025

Buddies

‘I received the following email and song about Vietnam Brothers from the author and wanted to share it with you:

Good evening. My name is Jim Lyons and I live in West Des Moines, Iowa. Forgive the intrusion, but I just read about you and your book.

I’m retired and one of my hobbies is writing songs, jingles, and doing some voiceover work. We’re the same generation, but I was not in Viet Nam. Had friends who were.

The things I write are mostly for fun and some yuks. However, because of my friends, I wrote one serious song; “Buddies”. It’s about two guys before, during, and after their Nam experience, My pals liked it and could relate in various ways. I thought I would send it to you and hope you might like it. Even though I wasn’t there, it was written from the heart. Thanks for listening.”Click below to listen to the song. Lyrics are included below for your reference, in case you’d like to follow along. Enjoy!

BUDDIES

Got out of high school back in ‘65

Lookin’ for adventure, and lovin’ life

We each got a letter, and I’ll be damned

They both said “Greetings from your Uncle Sam”

Looked each other and realized

Our country was callin’, no fear in our eyes

After sixteen weeks down in Leonard Wood

We were trained and ready and lookin’ real good

We played war when we were boys

But the guns we use now sure ain’t no toys

We’ve been buddies through thick and thin

No one could beat us, we’d always win

Got home once more, before we went off to war

Kissed our moms goodbye and our spirits soared

Spent time with our sweethearts and our GTO’s

Gave the cars to our brothers when we had to go

On down to the station to catch the bus

Some hippie guy there was really makin’ a fuss

Said I’d sneak up north before I’d go to war

So I used my boot to help him out the door

We played war when we were boys

But the guns we use now sure ain’t no toys

We’ve been buddies through thick and thin

No one can beat us, we’d always win

Thirty days later and man oh man

Headed to the jungles of Viet Nam

Got off that plane and walked straight into hell

Damn scared and shakin’, but we hid it well

Months in the delta, danger in the air

The enemy was hidin’ and we didn’t know where

Somehow we managed to remain alive

Stayin’ on the backside of the Claymore mines

We fought through that hell for a solid year

Then the orders came through, said “You’re outta here”

Made it back to the world, life shoulda been good

But things didn’t go the way we thought they would

I could tell you needed help

Didn’t know where to start

Watchin’ you struggle tore my heart apart

When you fight those demons every single day

A little bit of help would go a long long way

When I tried to help, you just walked away

We played war when we were boys

But the guns we use now sure ain’t no toys

We’ve been buddies through thick and thin

No one can beat us, we’d always win

It’s been five years and I’ve become a Dad

Wanted you to know about the joy I had

Looked high and low, and now I know

I lost my buddy a long time ago

As I stand here lookin’ down at your stone

I swear to God I never felt so alone

They say the war is over, that’s just not true

The fight goes on and on to those closest to you

It’s been a long time since Viet Nam

Now we fought through Iraq and Afghanistan

We lost a lot of buddies along the way

They gave everything they had for the USA!!!

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 19, 2025

The Missing and the Dead

A story for National POW/MIA Recognition Day. My friend, Betsy, wrote this article about a fellow Detroiter.

By Betsy Alexander, Historical Education Coordinator

Operation Crazy Horse was a search and destroy mission which commenced May 15, 1966, the action centered on and around LZ Hereford in Binh Dinh Province, South Vietnam.

Charlie (or C) Company, 1st Battalion (Airborne), 12th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division were flown into LZ Hereford the night of May 16 from LZ Gold to back up A and B Company, who had already been engaged by the VC a few times; early on the 17th they all met up. Charlie Company spent a sobering day dodging occasional stray gunfire while retrieving the bodies and belongings of Bravo Company’s 2/8th Cavalry dead.

The next few days were spent nearby creating LZ Milton and clearing more space for a second copter to land on LZ Hereford, which was saddle-shaped and very difficult to secure. The perimeter of the cleared landing area was dense five-foot tall, razor-sharp elephant grass ending at the hill’s steep precipice, which contained heavy vegetation all the way down to the valley floor.

Around 1:40pm on May 21, Day 6 of Operation Crazy Horse, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd platoons of Charlie Company were ordered to sweep the valley area surrounding LZ Hereford as the 9th NVA Regiment and the 97th VC Regiment were still lurking. The decision was made by 1st Battalion Commander LTC Rutland Beard to hold back only C Company’s 20-man mortar platoon on the LZ to provide fire support from above as the rest descended the steep hill. This also meant that until helicopters arrived to take the men to another LZ, the platoon would be completely alone and unguarded in active VC territory. The request by C Company’s CPT Don Warren to have at least one rifle squad stay behind for protection was also met with a strong negative from Beard. Warren departed to tell acting mortar platoon leader SSG Robert Kirby the news: they would be left on their own for a minimum of 45 minutes, perhaps longer. The captain and his three rifle platoons then started their hillside descent, and Beard departed in his helicopter.

Kirby tried to arrange his 20 men on the hill as best possible. With that sparse number they could not spread themselves out in the usual perimeter arrangement. Only a U-shaped defensive position could be achieved which left their top side completely exposed.

The men were in foxholes in groups of two, some battle-tested and some newly arrived in Vietnam. Their ranks included one newbie medic, SP4 David Crocker and Kirby’s all-important radio telephone operator SP4 John Spranza. Keeping his eye on the untested young guys in the back was SFC Louis Buckley, Jr., a “respected, competent leader” from Detroit. Buckley and one of the new guys, PFC Wade Taste started to clean up the area in anticipation of their departure.

There were two men on LZ Hereford who were outsiders to C Company. The first was the 2nd Platoon’s PSG Edward Shepherd, who was there only to hitch a ride to An Khe for his promotion board hearing, and he counted down the minutes to departure. Ironically, the second was Look magazine’s senior editor, Sam Castan who was there to shoot and “write a story about death” in Vietnam.

Around 2:15pm, SP4 Charles Stuckey and SP4 Paul Harrison spotted movement and let loose with their M-16s into the elephant grass – then all hell broke loose. Hundreds of VC rushed them and opened fire with AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades. Spranza was able to radio for immediate artillery back-up even though he was shot five times, including through his head, in the space of 10 minutes. The rest of C Company heard the artillery fire far above and tried to maneuver back up the hill to the LZ, but it was very slow-going through the dense jungle vegetation.

Reports diverge at this point: Some say that battalion HQ ordered A Company Huey’s to fly in for an emergency attack and medical evacuations, but their rescue efforts were stymied by “heavy fog that had rolled in over LZ Hereford.” Other accounts have battalion executive officer, Major Otto Cantrell, “circling above Hereford in his OH-13 observation helicopter, and Colonel Beard watching the battle from his command-and-control Huey” unable to determine who was VC versus C Company, so no immediate action was taken by Beard on Kirby’s requested artillery. “Heavy fog” or “observed from directly above”; which was it?

In any event, no one came to the unguarded men’s rescue fast enough.

Within minutes, 14 of the Charlie Company Mortar Platoon were dead: PFC Robert Lee Benjamin; SP4 Daniel Gibson Post; PFC Joel Tamayo; PFC Henry Benton; PFC Clarence Ray Brame; PFC Wade Taste; SP4 David Stephen Crocker; SP4 Austin Leon Drummond; SP4 Paul James Harrison; PFC Harold Mack, Jr.; SP4 A. V. Spikes; PFC Lonnie Clifford Williams; PFC James Francis Brooks, Jr.; and SGT Charles A. Gaines.

2nd Platoon’s PSG Edward Shepherd who was there waiting for a ride was also dead.

Look photojournalist Sam Castan had run into the elephant grass where a group of VC fatally shot him in the head; Look ran his “death” story.

Badly wounded, SP4 Spranza, SGT Kirby, SPC Isaac Johnson, and SPC Charles Stuckey all were able to crawl into various hiding places or play dead and barely survived the ordeal.

PFC Robert Roeder was the only member of the platoon who somehow escaped injury. Once all of the ammo and weapons he could find were completely exhausted, ha ran deep into the elephant grass and managed to elude the VC until help arrived. As he was the only living person available who knew the platoon’s men and wasn’t hospitalized, he had the sickening responsibility of trying to visually identify his dead brothers’ remains.

SFC Louis R. Buckley, Jr. was the only member of the platoon listed as Missing in Action. He had reportedly run southwesterly into the elephant grass when the shooting first started, and eyewitnesses stated they saw “blood on his shoulder and arm.” A search immediately after the incident did not locate him, finding only his abandoned pack.

SFC Buckley’s status with the DPAA (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency) is listed as unaccounted for, and in the analytical category as Active Pursuit. He’s memorialized on the Courts of the Missing at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (Punchbowl), and his name is inscribed along with his fallen comrades on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, DC. SFC Buckley is also remembered with a cenotaph at Arlington National Cemetery.

Louis Buckley, Jr. was born May 20,1943 in Detroit and lived in the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects. He had just turned 23 years old the day before he went missing. Louis’ parents, Elsie and Louis Sr. are both deceased, but his two brothers, Rick and Corey Buckley still await any new leads or information about “Bucky’s” disappearance.

Corey Buckley described his big brother as very nice, well-liked, and friendly; he loved boxing and had an enviable jazz record collection. He recalled Louis attending Detroit’s Bishop Elementary School and thought that Northeastern was his High School. Louis also knew Diana Ross and some of the other Motown artists quite well as their mother, and Mary Wilson of the Supremes’ mother, were best friends. These were neighbors, classmates, and buddies that would congregate at the famed Brewster Recreation Center in the early 1960s to talk music, boxing and their futures.

As with the rest of the mortar platoon, Louis ended up at Fort Benning, Georgia for his artillery training before shipping out. While in Georgia, he met and married his wife, Elizabeth. She gave birth to his son, Reginald Louis Buckley, on April 8, 1966, 43 days before his disappearance. His first tour of duty included Germany, but it was his second tour that landed him in Vietnam.

Both of Louis’ brothers supplied DNA to the DPAA in the hopes of them someday finding a match. The military officially declared him, along with thousands of others, as PFOD (presumptive finding of death) in January of 1978, but there has been nothing tangible to report to the family since the afternoon he went running into the elephant grass. They are still haunted by the idea of the search immediately after the attack, not knowing how thorough it was or if any other searches have happened in the subsequent 59 years. The brothers are now both in their seventies and as Corey shared, “It’s just the not knowing…”

SFC Louis Buckley, Jr. (5/20/1943 – 5/21/1966)

SFC Louis Buckley, Jr.

SFC Louis Buckley, Jr.There are still 1,566 Vietnam War MIAs as of this writing (9/18/2025)

Credits: Thank you to Corey Buckley; Michael Christy, HistoryNet.com; Doug Warden, CharlieCompanyVietnam.com; Marty Eddy, National League of POW/MIA Families; DPAA.mil

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update appears on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 13, 2025

The Nam

My friend, Joe Campolo, recently published this article on his website. It is true in every way.

Every war is different, and every war is the same. ∼ Anthony Swofford

Vietnam veterans often refer to Vietnam as “The Nam” when discussing their experiences during the war. This tells us that the Vietnam they remember was almost a living thing; an entity if you will, as much as a place.And it was, in fact, an entity. As the war moved along, things were constantly changing, regarding politics, missions, goals and tactics. This ever-changing dance card meant that what was true one day, was not true the next. What you did according to orders one day, was not according to orders the next. Who your ally was one day, may have been your enemy the next. It was confusing and chaotic.

Vietnam veterans often refer to Vietnam as “The Nam” when discussing their experiences during the war. This tells us that the Vietnam they remember was almost a living thing; an entity if you will, as much as a place.And it was, in fact, an entity. As the war moved along, things were constantly changing, regarding politics, missions, goals and tactics. This ever-changing dance card meant that what was true one day, was not true the next. What you did according to orders one day, was not according to orders the next. Who your ally was one day, may have been your enemy the next. It was confusing and chaotic.

So, what year you served in Vietnam, and even what month of that particular year influenced your perspective of that experience.And where you were in Vietnam also contributed to the myriad of experiences to be had over there. Those in the coastal regions had a far different view, than those further inland. And those along the Northern DMZ, had a much different perspective than those in the Central Highlands, and those in the Mekong Delta, and visa versa.

So, what year you served in Vietnam, and even what month of that particular year influenced your perspective of that experience.And where you were in Vietnam also contributed to the myriad of experiences to be had over there. Those in the coastal regions had a far different view, than those further inland. And those along the Northern DMZ, had a much different perspective than those in the Central Highlands, and those in the Mekong Delta, and visa versa.

And what you did in the Nam, varied greatly, even with those having the same MOS (duty classification) in different parts of the country and different times.And of course Vietnam was a crazy place in its own right; a foreign country which had been at war for decades. “The Nam” was a little, and in most cases a lot different for all of us who served there, especially compared to any other place we had ever seen or heard of. But our collective memories help define those experiences, as to where we were, what we did, who we were, what we saw….and who we are now.It was “The Nam”.***

And what you did in the Nam, varied greatly, even with those having the same MOS (duty classification) in different parts of the country and different times.And of course Vietnam was a crazy place in its own right; a foreign country which had been at war for decades. “The Nam” was a little, and in most cases a lot different for all of us who served there, especially compared to any other place we had ever seen or heard of. But our collective memories help define those experiences, as to where we were, what we did, who we were, what we saw….and who we are now.It was “The Nam”.***Joe’s website includes Nam stories, fishing tales, and guest writers who share experiences with us. Please take the time to check him out. https://namwarstory.com/2025/07/the-nam/#comment-25589

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update appears on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 6, 2025

Emotional speech honors Vietnam War veterans

The following speech includes a call to action to each of us. Please heed the advice given.,

By John Stewart

Recently, I spoke at a very special sunrise service honoring Vietnam War veterans from across Nebraska.

You may be asking yourself why I am writing about an event in another state. I want the people of Citrus County to fully understand the difficulties faced by Vietnam War veterans. And perhaps my words below will be of help to anyone in need here.

In 1985, a group of military veterans from World War II and the Korean War formed the Nebraska Vietnam Veterans Reunion (NVVR). As time and the age of personnel passed, the 20-member managing committee became increasingly dominated by Vietnam War veterans and their family members.

The purpose of NVVR was simply to have Vietnam War veterans a reunion avenue for sharing and healing. However, it was now coming to an end due to the age of the committee members, with no one else stepping forward to continue the program.

The sunrise service followed a day-before banquet attended by approximately 650 Vietnam War veterans and family members from across the state. The planned keynote speaker, Nebraska’s governor, was forced to cancel his banquet appearance due to other commitments. Scrambling to find a replacement, I was contacted and agreed to substitute for the governor.

In my 30 years of being heavily involved with the support of veterans, from an emotional stance this was the most difficult task I have ever done.

Recovery, honor, and trustThe main subject of my speech was recovery. I spoke about the difficulties we faced when coming home from the Vietnam War after experiencing the horrific actions of combat and returning to be insulted by those demonstrating against that war, despite the fact that we were in need of recovery.

But while in combat in Vietnam, I said we had two other words that were nearly as important to us as recovery upon return: honor and trust.

A perfect example of honor was in our young soldiers. Of those killed in Vietnam, 61 percent were 21 years old or younger, while thousands of them were only 18 years old.

Imagine you had just graduated from high school, and you are still three years away from being able to vote and drink alcohol legally. You may have never had a driver’s license. Then, you are drafted into the Army and spend eight weeks learning how to use a rifle and a pistol, a machine gun, a grenade and a bayonet.

Then told to go and serve and kill people … while serving with honor.

Those 18-year-old kids may not have been able to put it into words, but they quickly learned what honor was to be. They were doing their best to fulfill their mission and defend and protect their fellow soldiers. Even if risking their own life was necessary.

And for those 18-year-olds, the second important word came into their lives: trust.

They realized their brothers trusted them to do their mission, even if under heavy fire, and their lives were at risk.

Teenager or not, honor and trust were also two words every single one of us, regardless of age, lived by while serving alongside our brothers-in-arms in Vietnam. However, after thinking about it, I said a third word is necessary to describe us in Vietnam: courage.

Serving with courageWhen one of our brothers-in-arms was killed, it was horrific, and we did what soldiers have to do. We cried but crammed our anguish and sorrow way down deep inside into our own secret box and we closed the lid tight so we could carry on doing our job … with courage.

But then, one day, we who survived and fought with courage and honor and trust finally came home. But, for many of us upon return, the war never ended. And that word, recovery, came into the forefront.

It is difficult for some people to understand our mental status when on Thursday we could have been in a firefight or watching a village burn or watching friends die, and on Sunday our tour was over, and we were flown out to find ourselves at LA International Airport watching Americans protest our service and sacrifices and calling us baby killers.

We needed recovery from our nightmares.

Many of us committed suicide at some point after returning to that horrific welcome home. And there were a lot of suicides. It is difficult to obtain accurate figures of how many of us did so, but the Veterans Administration (VA) and National Library of Medicine did issue reports covering the 1979 through 2019 suicides of veterans of the Vietnam War era. The number was rather unbelievable.

To put it into perspective, if every citizen of Inverness and Ocala died today, it would be less than the number of veteran suicides in VA’s report. Over 94,000 were in that report. And there are many more years of suicide numbers not included in it.

I often wonder how many of those veterans could have been saved if they had been welcomed home and provided adequate recovery programs.

I told the crowd there were probably some in the banquet room who needed recovery and, fortunately, did reach out for help. However, some of us present may not have sought recovery upon return from the hell of Vietnam due to our post-traumatic stress. I followed that by stating there are probably several reasons why we did not do so.

How could we possibly tell some stranger about the atrocities we had faced?

How could anyone who had not been there understand what we had been through?

We killed people or saw others who did so. We saw our friends get killed or wounded. We held them in our arms and cried. We were shot, blown up, and maimed.

We came home and were told not to wear our uniforms in public because it was dangerous. Uniforms we wore and served with courage, honor, and trust.

We came home and were cursed at, spit on, and humiliated for our service.

And we suffered.

Many of us went looking for comfort in a bottle, in a needle, became homeless, considered committing suicide … or actually did it.

We needed recovery and honor, but many did not receive it, and many of us did not seek help.

Getting the help we needI was one of them and told my own story. I’ll not repeat it here because once was enough in discussing my difficulties and an extremely close moment in my life of nearly committing suicide. I used my story last night to encourage those in need of help to get it as I did.

After my speech, veteran after veteran and family member after family member came up to me to tell their own story of sacrifice, service, and suffering. Many were in wheelchairs, or using strollers or canes, missing both legs, an arm, an eye, or suffering from other injuries after being wounded in Vietnam.

Many were without any physical injuries, but obviously suffered from what I could readily see were mental health issues.

My most emotional moments occurred when multiple spouses of veterans came up to me and said their husbands needed help with their PTSD, never went to get it, and after my speech, I told them they would go get help. Their hugs will never be forgotten.

I held my tears back as best I could, but it was difficult until I returned home and began writing this article immediately. And, as I sit here with keyboard in hand, in all honesty, tears are rolling down my face from my experiences these past few days during this last reunion.

There is no actual number of how many Vietnam War direct-combat veterans reside in Nebraska, just as it is not found in Florida or throughout America. Florida has approximately 423,000 Vietnam-era veterans, according to the Florida Department of Veterans’ Affairs in March 2025. It is challenging to find an exact number for combat veterans, specifically, as statistics often refer to the broader “Vietnam-era” designation.

Regardless of the number, I am certain that many who served in combat or simply in uniform at other locations during that turmoil are now in need of help. For those reading this article in that situation, here are possible avenues to achieve it:

Visit your church and speak with a minister. Ask for help to recover.

Go to the Veterans Service Office (VSO). They will help you get to available VA recovery support programs. In Citrus County, you have the best VSO I’ve seen over the past 30 years.

Go online at VA.gov where you will find an enormous number of methods to achieve recovery.

Use your cellphone and dial 988, then press 1 for 24/7, confidential crisis support. By the way, that crisis line is also for military family members.

Whatever method you choose, if you need help, follow my example. Go get recovery.

I hope and pray that if there are some in Citrus County’s thousands of veterans experiencing problems and needing help, they will take my advice.

A special messageA few minutes before I departed for home from my speech that night, ironically, I received a forwarded email that I believe says in its entirety what America should have said to the Vietnam War veterans upon their return. I read it to the audience and have extracted a portion of that email for you below.

It is from Anne Zimbler, World Airways flight attendant, 1970-73.

“What many of you may not know is how much your cabin crews cared about you. It would have been unprofessional for us to have shown you the tears we held until you deplaned in Vietnam. We worried about you and said silent prayers for your safe return. We cherished our time with you and tried to make you as comfortable as possible. Most flight attendants, from the many airlines that flew military charters during that era, would tell you we truly treasured our military passengers.

“… on behalf of the cabin crews who brought you home, we thank you for your bravery, dignity, and service. We will always remember your faces and the many conversations some of us had with you on those long trips over the Pacific. In our minds, you remain young men who served your country and graced our lives for a moment in time, many years ago, during a difficult period in our shared history.

“You are still, and will always be, our heroes … welcome home.”

To my brothers-in-arms, as I sit here in tears, I echo Anne’s final comment.

Welcome home.

John Stewart is a retired Air Force Chief Master Sergeant and disabled Vietnam War veteran. In 2016, he was inducted into the Florida Veterans Hall of Fame. His columns are sourced from public, government, and private information, and the content is checked for accuracy as best as possible. However, you have the responsibility to verify the contents before taking any related action.

*****

Anne Zimbler recently contributed an article to this website. Read it here: https://cherrieswriter.com/2025/08/16/the-freedom-bird/

Here is the direct link to the article on Citris County Chronicle: https://www.chronicleonline.com/lifestyle/veterans/emotional-speech-honors-vietnam-war-veterans/article_f6d41212-f9ab-538b-92fe-b588f7488cbf.html

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 30, 2025

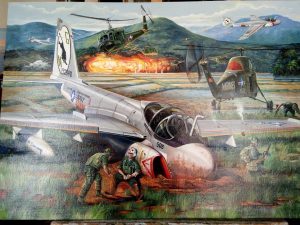

Bronco Pilot gives his life to save his observer.

The story of the Bronco pilot who died after ditching his OV-10 to save his observer, who couldn’t eject because his parachute was shredded by the explosion of a North Vietnamese SA-7.

By Dario Leone

Jul 10 2023

Captain Bennett elected to ditch in the Gulf of Tonkin, although he knew that his cockpit area would very likely break up on impact. No pilot had ever survived an OV-10 ditching.

The OV-10 was a twin-turboprop short takeoff and landing aircraft conceived by the US Marine Corps and developed under a US Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps tri-service program. The first production OV-10A was ordered in 1966, and its initial flight took place in August 1967.

The Bronco’s missions included observation, forward air control, helicopter escort, armed reconnaissance, gunfire spotting, utility and limited ground attack. The USAF, however, acquired the Bronco primarily as a forward air control (FAC) aircraft. Adding to its versatility is a rear fuselage compartment with a capacity of 3,200 pounds of cargo, five combat-equipped troops or two litter patients and a medical attendant.

The first USAF OV-10As destined for combat arrived in Vietnam in July 1968. A total of 157 OV-10As were delivered to the USAF before production ended in April 1969.

On Jun. 29, 1972, Captain Steven L Bennett, a USAF FAC, was flying an OV-10 Bronco on an artillery adjustment mission near Quang Tri City, South Vietnam. A Marine gunfire spotter occupied the rear seat of the lightly armed reconnaissance aircraft.

According to Air Force Historical Support Division, after controlling gunfire from US naval vessels off shore and directing air strikes against enemy positions for approximately three hours, Captain Bennett received an urgent call for assistance. A small South Vietnamese unit was about to be attacked by a much larger enemy force. Without immediate help, the unit was certain to be overrun. Unfortunately, there were no friendly fighters left in the area, and supporting naval gunfire would have endangered the South Vietnamese. They were between the coast and the enemy.

Capt Steven L Bennett, Medal of Honor recipient, Vietnam

Capt Steven L Bennett, Medal of Honor recipient, VietnamCaptain Bennett decided to strafe the advancing soldiers. Since they were North Vietnamese regulars, equipped with heat-seeking SA-7 surface to air missiles (SAMs), the risks in making a low-level attack were great. Captain Bennett nonetheless zoomed down and opened fire with his four small machine guns. The troops scattered and began to fall back under repeated strafing.

As the twin-boomed Bronco pulled up from its fifth attack, a missile rose up from behind and struck the plane’s left engine. The explosion set the engine on fire and knocked the left landing gear from its stowed position, leaving it hanging down. The canopies over the two airmen were pierced by fragments.

Captain Bennett veered southward to find a field for an emergency landing. As the fire in the engine continued to spread, he was urged by the pilot of an escorting OV-10 to eject. The wing was in danger of exploding. He then learned that his observer’s parachute had been shredded by fragments in the explosion.

Captain Bennett elected to ditch in the Gulf of Tonkin, although he knew that his cockpit area would very likely break up on impact. No pilot had ever survived an OV-10 ditching. As he touched down, the extended landing gear dug into the water. The Bronco spun to the left and flipped over nose down into the sea. His Marine companion managed to escape, but Captain Bennett, trapped in his smashed cockpit, sank with the plane. His body was recovered the next day.

For sacrificing his life, Captain Bennett was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. The decoration was presented to his widow by Vice President Gerald R. Ford Aug. 8, 1974.

A US Air Force North American OV-10A Bronco firing a smoke rocket in the area north of Saigon in February 1969 to show where the North American F-100D Super Sabre should drop its bombs. The F-100 was assigned to the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron, 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing, at Bien Hoa air base. Photo credit: U.S. Air ForceDario Leone

A US Air Force North American OV-10A Bronco firing a smoke rocket in the area north of Saigon in February 1969 to show where the North American F-100D Super Sabre should drop its bombs. The F-100 was assigned to the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron, 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing, at Bien Hoa air base. Photo credit: U.S. Air ForceDario LeoneDario Leone is an aviation, defense and military writer. He is the Founder and Editor of “The Aviation Geek Club” one of the world’s most read military aviation blogs. His writing has appeared in The National Interest and other news media. He has reported from Europe and flown Super Puma and Cougar helicopters with the Swiss Air Force.

Here’s the link to the original article:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 24, 2025

My Father’s Vietnam

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999

In 1999, one former combat soldier from the Army’s Fourth Infantry Division in Vietnam sent a package to his son comprised of words and photos regarding his time during the war. Check out the photos and read what his son had to say about the package.

BY JON MEACHAM

Thirty years after everything happened–and 31 years since he had first set foot in Southeast Asia–my father, a soldier of the Fourth Infantry Division, wrote me a letter. It was 1999, and the note came with a set of recently rediscovered photographs he and his friends had taken with an old 35-mm Minolta in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. There were images of impossibly young men, their helmets heavy on their heads, carrying M-16s, smoking cigarettes, and trying to look happy–itself a form of bravery. There were pictures of the lush landscape and of villagers going about their business, drawing water and sitting, watching, some blankly, all warily.

My father’s words, though, were the most poignant part of the package. “I thought you might like to have these,” he wrote me. “You are the historian, and I know you will preserve them. I remember the brutal heat, the more brutal humidity, the chop-chop-chop of the helicopter blades, and elephant grass that could cut men up like a knife. And I remember many things that I have never told you or anyone. Those are the demons that I will always bear. South Vietnam, for me, is a place I’ve never really left.”

Neither, truth be told, has America. As I watched Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s illuminating 10-part documentary The Vietnam War, I thought often of my father and, inescapably, of his “demons.” He hinted from time to time about harrowing firefights with enemy soldiers but offered no details. The numbers tell a grim story: from 1966 to ’70, 2,500 fellow members of what’s known as the “Ivy Division” died; 15,000 were wounded. For my father and so many other veterans, the battles never genuinely ended. Over the decades, casualties of this perpetual war included emotional stability, peace of mind, marriages, and, more broadly, America’s sense of virtue and of self-confidence.

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999 Courtesy Jon Meacham

The power of Burns and Novick’s documentary lies in its remarkable capacity to tell the story of the struggle in terms both particular and universal. This is part historical narrative, part cultural exploration, and part therapy–the last made even more effective by its subtlety. Burns and Novick take us from the corridors of power in Washington, Hanoi, and Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) to rice paddies and jungles and POW prisons. Driven by Burns’ characteristic devices–curated music, limited but effective interviews, and powerful still and moving imagery–The Vietnam War may have an even larger cultural impact than his landmark Civil War project of 1990. (Colin Powell, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, gave President George H. W. Bush videotapes of that documentary to watch in the run-up to the Gulf War. In his audiotape diary, the President recounted how the moving accounts of the travails of ordinary soldiers helped reinforce his determination to avoid a long land war in the Middle East.) I’ve always thought about what it would have been like for veterans of the cataclysm of 1861–65 to experience Burns’ treatment of their war. With the new documentary, we don’t have to wonder, for the warriors of the Vietnam era, many now in their 70s, will relive those momentous, disorienting days.

Vietnam and Watergate were decisive events in the erosion of trust in the government with which we still live, and both Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon admitted in private what they would not say in public. “The great trouble I’m under–a man can fight if he can see daylight down the road somewhere,” Johnson told Senator Richard Russell in a tape-recorded conversation in March 1965, early in the journey. “But there ain’t no daylight in Vietnam.” During the ’68 campaign, Nixon was more honest with his aides than with voters–and soldiers: “I’ve concluded that there’s no way to win the war,” Nixon said. “But we can’t say that, of course. In fact, we have to seem to say the opposite, just to keep some degree of bargaining leverage.” The war would last another seven years.

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999. Courtesy Jon Meacham

Hal Kushner, a medic, held in captivity for five years by the Viet Cong, is among the film’s memorably affecting figures. His voice catching, tears coming, Kushner describes his 1973 release: “There was an Air Force brigadier general in Class A uniform. He looked magnificent. I looked at him, and he had breadth; he had a thickness that we didn’t have. He had on a garrison cap, and his hair was plump and moist, and our hair was like straw. It was dry, and we were skinny. And I went out and I saluted him, which was a courtesy that had been denied us for so many years. And he saluted me, and I shook hands with him, and he hugged me–he actually hugged me. And he said, ‘Welcome home, Major. We’re glad to see you, Doctor.’ The tears were streaming down his cheeks.”

In the film, Kushner tells this story with Ray Charles’ “America the Beautiful” playing softly in the background. To write about it risks making the presentation of Kushner’s release seem hokey, but it is not. Far from it. To me, the Kushner sequence is perhaps the most powerful moment in the entire series, not least because of the newly freed POW’s sense of dimension and size. The magnificence of the officer who greeted him, the “breadth” and “thickness” and the “plump” and “moist” hair: it’s as though the scraggly and sapped Kushner saw the general as the embodiment of the old America, invincible America, victorious America–an America that didn’t really exist anymore, or at least not in Southeast Asia.

Picture taken in the Central Highlands in South Vietnam 1968-69. Courtesy Jon Meacham

One cold winter morning after Christmas 1984–I was 15, the same age my son is now–my father and I took a trip to Washington. Like a lot of other veterans, he had been skeptical of the plans for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, thinking the unusual design in a gently sloping hill in the shadow of the monuments to Lincoln and Washington suggested a lack of respect. Seeing it changed his mind. He said nothing as we walked along the wall of the dead. Coming to the years of his service, he stopped, searching for a familiar name. He found it, and it was within reach. He ran a finger over the letters, turned, stepped back, and we moved on.

In his letter to me with the photographs of Vietnam 15 years later, my father was relatively terse about his thoughts in-country. “I wanted,” he wrote, “to get back to life.” My father is dead now, but for the warriors who remain among us, Ken Burns has at last charted a path back toward life, and toward home.

Meacham is the author of Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush.

This appeared in the September 25, 2017, issue of TIME.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 16, 2025

The Freedom Bird