John Podlaski's Blog, page 6

October 19, 2024

Pulling Rank

Second Lt. Marvin Wolf overcame obstacle after obstacle to make sure 150 enlisted men got home from a combat tour in Vietnam on a C-141 plane like this one he photographed years later. (Photo by the author.)

My Men Had Served a Year in Hell. I Was Getting Them Home, Come Humid Hell or High Water.

General Becker shook my hand, said nice things about me, administered an oath in which I swore to support and defend the Constitution of the United States, then pinned a gold bar on my right collar while Major Phillips, my boss, pinned crossed infantry rifles on the left.

Ten days later, I got orders reassigning me to Fort Benning, Georgia. My combat tour in Vietnam was over.

I said my goodbyes and hopped a Huey to Camp Holloway, Pleiku. In the morning I reported for shipment and learned that I would be among 150 men returning. It was due in an hour. As the only officer in this group, I was handed a packet of orders and put in charge of getting every man in the group through the Military Airlift Command system. My first command!

The mere presence of a second lieutenant returning to the States raised questions. Wartime demands on the officer ranks had accelerated promotion cycles. Unless they were killed or court-martialed, second lieutenants became first lieutenants after one year. And they never deployed to Vietnam without at least six months of active duty.

A year later, when they rotated home, all were first lieutenants.

My troops included three warrant officers, all pilots. They decided that I must be on emergency leave, then asked “Do you have some kind of family emergency?”

I called everyone together in a semicircle next to the runway and explained that I was newly commissioned, that I had been a buck sergeant and had arrived in Vietnam with the advance party of the First Air Cav in August 1965 as a PFC.

One man said, “Well, if you got a battlefield commission and you were in the Cav for more than a year, why ain’t you wearing the CIB?”

I replied that the Combat Infantryman Badge is awarded to men with an infantry MOS assigned to an infantry brigade for at least thirty days of combat. That meant that they were paid in that unit, were promoted there—were in every sense a member. I had spent months in the field with infantry units, but I was never assigned to one. My job was not fire and maneuver but shooting photos and gathering news material.

We sat on our bags in silence, waiting for our ride home.

And waiting. There was no shade; as the sun rose it became uncomfortably warm, I told one of the senior sergeants to find water for everyone, then go lay on some lunch. I told another to find a shady area big enough to protect everyone from the sun.

That guy returned in ten minutes with a place; I told him to take the men there.

Somebody had to be near the runway when our plane landed; I appointed myself; the pilots joined me for reasons of their own.

At noon, we ate bologna sandwiches and drank bottled water.

At 3:00 p.m. an Air Force sergeant told me that our aircraft would land in a few minutes. I sent one of the pilots to get the troops; they returned just as a big C-141 slid onto the runway a mile distant.

We waited while it taxied in. Then 150 newbies stumbled, blinking and sweating, into the nightmarish heat, humidity, and stink of burning human feces that was everyday Vietnam. They got into buses and drove off.

After a few minutes, the pilot, a captain, appeared and headed for the operations building. I stepped into his path.

“Lieutenant Wolf, sir,” I said, self-consciously. “When can I load my men?”

He dodged around me, calling over his shoulder, “We’re not taking you.”

I was probably the junior officer in all four armed forces and the Coast Guard, but I had spent much of the previous year as an even more junior enlisted man, cajoling very senior officers to allow me to do things or go places they had already refused to allow. There was a fine art to knowing how hard to push, when to stop, and who could be pushed.

But I was not afraid of any Air Force captain.

I ran after the pilot.

“What the hell do you mean, you’re not taking us?”

He regarded me warily, as though he feared I might bite him.

“We don’t have enough fuel,” he said, moving off as fast as he could.

Not enough fuel? Literally thousands of 55-gallon drums of jet fuel were stacked along the edge of the runway. “Not enough fuel” was Air Force for “I want to go home before the shooting starts.”

Two minutes later, I vented my spleen to an Air Force lieutenant colonel. More carefully than I would have spoken to his Army counterpart, I explained that my men had served a year in Hell, that they had waited all day to go home and we expected to be on that C-141 when it took off.

“He’s right about the fuel—those drums belong to the Army,” replied the colonel. “But hold on. Cool down while I talk to the pilot. He’ll take you and your men, I promise.”

Ten minutes and a phone call later it was worked out: our plane would refuel at Cam Ranh Bay before heading back to The World.

As I counted noses, loading my men on the plane, the pilot glared at me.

Flight time to Cam Ranh Bay was 20 minutes. We landed in driving rain and parked in the fueling area. The co-pilot, also a captain, came back to say that refueling would commence as soon as everyone was off the aircraft.

Marvin Wolf receives the Air Medal from Maj. Charles Siler in 1966. Photo courtesy of the author.

I looked out: The fueling crew was in wet-weather gear, but there was no structure, no trees, no trace of shelter for half a mile. And the sky was falling.

“It’s raining very hard,” I said.

“Air Force regulations,” he said.

“I am not going to get these men soaking wet on their last day in Vietnam,” I replied. “JP4 isn’t that volatile. In the Cav, we refuel Hueys with their engines running—and we’ve never had a fire. And it’s so wet out there that there’s zero chance of an accidental fire!”

I was bluffing: We did refuel Hueys with engines running, but only with the crew chief standing by with a fire extinguisher.

“Air Force regulations,” replied the captain. “Get your men off the plane. They have to be at least a hundred feet away before we can start refueling.”

“Hell, no,” I said. “Excuse me. I apologize. Hell no, Sir.”

The standoff continued for an hour. My men seemed to be enjoying it just a little more than standing out in the rain.

“Be reasonable, Lieutenant. Flight regulations say that a crew can’t be awake more than a limited number of hours, including the time we’re flying. So, if we don’t leave in the next hour, we can’t go. We’ll have to log sack time here, and they’ll have to find you a new crew. We may all have to spend the night here.”

“Boo hoo,” I replied. “Nobody’s got a change of uniform. I’m not sending my guys out to get soaked and then make them fly home in wet clothes.”

The co-pilot stormed off. Then one of my pilots came up with a face-saving solution: Our guys would stand under the C-141’s massive wings, sheltered from the rain, while refueling proceeded. One helicopter pilot would stay with each group to ensure that nobody lit a cigarette.

I went forward to the cockpit and made my pitch. The pilot’s face lit up—he wouldn’t have to spend the night in a combat zone.

Thirty minutes later, tanks topped, we soared up through thick clouds still heavy with rain and into the sky.

After a while, one of the sergeants came over to say that he’d chatted up the loadmaster and found out what was eating our pilots: The usual route for outbound flights was Travis-Honolulu-Manila-Pleiku, with a crew change in Manila. Manila to Pleiku is only about 1,600 miles round trip, well within a C-141’s range. But outward bound between Honolulu and Manila, the autopilot malfunctioned. Before the pilots knew it, they were a thousand miles off course. Instead of Manila, they landed at Andersen AFB, Guam. That’s three times the distance from Manila to Pleiku, too far to fly roundtrip without refueling. The crew of our plane was based in Guam, and that’s where the original crew waited.

Wolf grew frustrated over the supposed dilemma of refueling the C-141 that would take his men home. He had even photographed an air-to-air refueling of the hulking transport planes, like this one, during his days as an Army combat correspondent. (Photo by the author.)

And, because the pilot had never planned to haul us to Guam, there was no food aboard. The crew had box lunches, but we wouldn’t eat again till Guam.

I couldn’t believe there was no chow available in Cam Ranh Bay. We would have been OK with C rations. But the pilots didn’t ask; loading food might have caused a delay that would cost them a night in a combat zone.

About an hour out of Guam, I asked the pilot, as nicely as I could, if he’d radio ahead to lay on a mess hall and transportation.

The pilot shooed me out of the cockpit.

Andersen AFB was a B-52 base and boasted some of the world’s longest runways. We landed around midnight and taxied for a long time, then stopped. Through the window, I saw nothing but darkness until a blue pickup truck pulled up. The pilots and crew got off, trotted over to the truck and sped off into the night.

And left us on a pitch-black runway somewhere on an enormous base.

After ten or fifteen minutes, I realized that pilot had taken his revenge on an uppity infantry lieutenant.

I told everyone to take their valuables, leave everything else, and get off. The sergeants put the troops in a column of twos. I grabbed one of the helicopter pilots and told him to bring up the rear and make sure nobody got lost, then moved to the head of the column. We walked the white runway line toward a distant speck of flashing light that I guessed must be the tower.

Half an hour later, I burst into Flight Operations ready to kill. By ancient tradition, “rank among lieutenants is like virtue among ladies of the night.” So, when the duty officer turned out to be an Air Force first lieutenant, I got right in his face.

I told him I wanted buses for my men and a mess hall to serve them. And I wanted them now.

The lieutenant showed no surprise that a wild man was making demands and ranting about chickenshit REMF pilots who’d leave a planeload of hungry and exhausted soldiers just out of the war zone sitting on a runway miles from anywhere in the middle of the night. In five minutes, my guys were boarding buses to a mess hall. I watched as each one pulled out. I was about do Tail End Charlie on the last bus when the Flight Operations lieutenant appeared.

“Let ’em go,” he said. “They’re my responsibility now. Come with me.”

He took me to the Officer’s Club, where I ordered a steak and all the trimmings. I ate it and ordered another—and he wouldn’t let me pay for either one. Before my plate was empty, half a dozen B-52 pilots had surrounded our table, all trying to buy me drinks. And all anxious to hear about what the receiving end of an Arc Light was like.

Arc Light was a B-52 strike. Here on Guam, flight crews rose at two o’dark, briefed at 0300 and an hour later were at 40,000 feet. They flew 2,500 miles nonstop, refueled in the air, and proceeded to grid coordinates somewhere over Vietnam, to a target they never saw. When their computer said so, each B-52 dropped eighty-four, 500-pound and four 750-pound bombs; together the four planes in a typical Arc Light obliterated an area over a half a mile wide and more than a mile long. Each bomb blasted out a crater fifteen feet deep and fifty wide.

Then they turned and flew another 2,500 miles nonstop back to Guam.

All without ever seeing their target.

Now these B-52 pilots had an actual Air Cav infantry officer in their midst, and they were anxious to find out what effect their bombs had on our targets.

I had twice witnessed Arc Light strikes, both from a Huey three or four miles out and at about 4,000 feet—safe, yet close enough to hear the blasts and see a giant brown zipper opening in the green jungle with concentric shockwaves radiating out from each bomb blast. Here and there were flashes of dark orange. An enormous pall of smoke and dust rose from the impact area.

Once I landed to observe the aftermath of a strike. Hours after the last bomb fell, the air was thick with smoke from a multitude of fires. Human body parts covered with flies, a moonscape of craters and uprooted trees and great gashes opened in the earth to expose parts of a tunnel complex below.

All this I shared with the B-52 pilots. Then they wanted to know if their bombs were effective, if it was helping our efforts. I said that nothing we faced in South Vietnam could withstand that kind of bombing and that their accuracy was spectacular—but these strikes were only as effective as our intelligence. I did not say that often our intelligence was mostly guesswork.

Two hours later, reunited with my men, we were airborne, bound for Honolulu. Everybody soon fell asleep—except me. I was trying to anticipate the next thing that could go wrong. Then I realized that it already had: Guam is American soil. If that jerk-off pilot hadn’t abandoned us, we could have saved the hour that would be required to go through Customs at Travis AFB.

I went up to the cockpit to introduce myself to the pilot, a cheerful, apple-cheeked captain, and asked him how long we would be in Hawaii.

“Depends on how quickly they refuel us,” he said, pleasantly. “Anything over ninety minutes, and you’ll need a fresh aircrew.”

“Say that’s what happens—how long a layover?”

“Four or five hours at least. Maybe more.”

“Then could we at least get Customs out of the way in Honolulu?”

“You didn’t go through Customs at Andersen?”

I shook my head.

“Well, that was stupid,” said the pilot. “Yeah—if they send us to bed, I’ll have base ops call Customs and make that happen.”

I revised my opinion of the Air Force upward. A little.

As I turned to go, the co-pilot, a first lieutenant, piped up.

“You’re on emergency leave, right?”

“No, nothing like that,” I replied and turned to go again.

“But you’re not in any kind of trouble?” he asked.

“No, ” I replied, dreading what I knew was coming.

“Then, how come you’re still a second john?” asked the lieutenant.

“I was commissioned eleven days ago.”

“In Vietnam? Really! How did that happen?”

Before I could catch it, a tiny sigh escaped. “Kind of a long story.”

“It’s quite a way to Honolulu and when the autopilot’s working, we don’t have that much to do up here,” said the captain, smiling, interested.

“My wife made fresh coffee,” added the lieutenant. “By the way—how come you’re not wearing a CIB—you’re infantry, right?”The cockpit was quieter than the passenger compartment; one could converse in normal voices. Before answering, I looked into the night. A brilliant half-moon hung high against an indigo blanket glowing with more stars than I had believed existed. Below us, a silent symphony of lightning illuminated an endless sea of clouds. A vast electrical storm, beautiful beyond imagination.

And darkness was upon the face of the deep and the spirit of God hovered over the face of the waters. The words from Genesis popped into my mind. I realized that one part of my life was over; another just beginning. It was scary yet exhilarating. I sat down between the pilots.

“Maybe I will have some coffee,” I said. “About the CIB—it’s a long story.”

“Flying time is eight hours, so you might as well start,” said the co-pilot.

I took a long breath. “A couple of years ago I was working in a camera store, and then my driver’s license got suspended….”

This War Horse Reflection essay was written by Marvin Wolf edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Abbie Bennett wrote the headlines.

Here is the link to the actual article: https://thewarhorse.org/soldier-overcomes-obstacles-to-get-troops-home-from-vietnam/?mc_cid=ac56894a2e&mc_eid=9693ec6f98

Marvin J. Wolf

Marvin J. WolfMarvin J. Wolf served 13 years on active duty with the U.S. Army, including eight years as a commissioned officer. He was one of only 60 enlisted and warrant officers to receive a direct appointment to the officer ranks while serving in Vietnam. Wolf has authored more than 20 books, including three about the Vietnam War: “They Were Soldiers,” “Abandoned In Hell,” and “Buddha’s Child.” He lives in Asheville, North Carolina, with his adult daughter and a neurotic, five-pound Chihuahua.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

October 12, 2024

A Vietnam War Nurse

Join Sarah Blum, a former Vietnam War nurse, in a thirty-three-minute podcast as she talks about her military training and time before and after Vietnam.

In this episode, we dive into the incredible journey of Sarah Blum, a former military nurse who served during the Vietnam War. From her early days as a serious child with an old soul to her experiences in one of the most challenging environments imaginable, Sarah shares her powerful story of resilience, strength, and advocacy for women veterans.

Sarah Blum, Vietnam War Military Nurse and Author

Sarah Blum served as a military nurse during the Vietnam War, stationed at the 12th Evac Hospital beside the Hobo Woods. She is the author of “Warrior Nurse, Healer: PTSD and Healing” and “Women Under Fire: Abuse in the Military.” Her experiences have shaped her into a strong advocate for women veterans, particularly those who have faced sexual assault in the military.

Key Points Discussed:Childhood and Early Influences:

Sarah reflects on her early years, growing up during WWII and developing a sense of independence and strength from a young age. She shares memories of playing with a simple yet cherished baby doll and coach, and how these experiences shaped her character.Pursuit of Nursing and Military Career:

From creating a career booklet at nine years old to joining the military in response to the Vietnam War, Sarah outlines her path to becoming a nurse and the challenges she faced, including height restrictions and initial rejections by different branches of the military.Experiences in Vietnam:

Sarah provides a harrowing account of her time at the 12th Evac Hospital, where she dealt with constant casualties and extreme conditions. She describes the intense pressure, the emotional toll, and the unrelenting demands of her role.Impact of Military Service:

Reflecting on how her service impacted her personally and professionally, Sarah discusses the resilience and strength she gained, as well as the stories and experiences that fueled her advocacy work and writing.Advice for Women in the Military:

Sarah offers candid advice to women considering joining the military and those already serving. She emphasizes the importance of self-care, awareness of the challenges they might face, and the necessity of maintaining personal power and resilience.Resources Mentioned:

“Warrior Nurse, Healer: PTSD and Healing” by Sarah Blum-launch date-March 6, 2025“Women Under Fire: Abuse in the Military” by Sarah Blum www.womenunderfire.net” Sarah Blum’s book, Women Under Fire, is a stunning revelation of sexual abuse in the U.S. Armed Forces. As Blum’s book makes scathingly clear, this criminal activity–demeaning, degrading and despicable–is far too prevalent in each of the armed services. Action is needed—comprehensive, effective and swift—before sexual abuse rips out the very heart of the military.” (Lawrence Wilkerson, Colonel, US Army (Retired), former chief of staff to Secretary of State Colin Powell, and Distinguished Visiting Professor of Government and Public Policy at the College of William and Mary).Sarah

Healing Wounds: A Vietnam War Combat Nurse’s 10-Year Fight to Win Women a Place of Honor in Washington, D.C. Kindle Edition by Diane Carlson Evans (Author), Bob Welch (Author), Joseph Galloway (Foreword) Format: Kindle Edition 4.7 4.7 out of 5 stars 880 ratings 4.5 on Goodreads 1,489 ratings See all formats and editions Featured in Kristen Hannah’s new book The Women What is the price of honor? It took ten years for Vietnam War nurse Diane Carlson Evans to answer that question—and the answer was a heavy one. In 1983, when Evans came up with the vision for the first-ever memorial on the National Mall to honor women who’d worn a military uniform, she wouldn’t be deterred. She remembered not only her sister veterans, but also the hundreds of young wounded men she had cared for, as she expressed during a Congressional hearing in Washington, D.C.: “Women didn’t have to enter military service, but we stepped up to serve believing we belonged with our brothers-in-arms and now we belong with them at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. If they belong there, we belong there. We were there for them then. We mattered.”

Quotes:

“I was alone on the street from the time I was three. In 1942, my dad was in WWII, and he bought me a baby doll and a coach. It was glorious to me.” “Imagine being a sensitive young nurse in the worst area hospital in Vietnam, working 16-20 hours a day regularly, standing in the blood of wounded soldiers.”Where you can find Sarah Blum: https://www.facebook.com/sarah.l.blum.1

Here is the link to the original interview, including transcripts: https://dogtagdiaries.captivate.fm/episode/female-vietnam-veteran

Be sure to follow or subscribe to Dog Tag Diaries wherever you listen to podcasts:

https://dogtagdiaries.captivate.fm

If you wish to read more about nurses in Vietnam, go to the magnifying glass at the top right of this page. Click it and type in ‘NURSES’ – a drop-down menu will list other posts on this website. To return to this page afterward, use the back arrow at the top left.

*****

You aren’t alone.

If you’re thinking about hurting yourself or having thoughts of suicide, contact the

Veteran crisis line: Dial 988 then press 1, chat online, or text 838255.

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

October 5, 2024

Booby Trap Ville – 1969

Have you ever had a “close call” and cheated death? This is one soldier’s story during the Vietnam War. He should have died on this mission, but a booby trap malfunction saved his life. Now, the event continues to haunt him in his dreams. Read what happened.

The name “Boobytrap Ville” sounded like the title of a B movie or, even worse, an army training film. It wasn’t either one. It was a real place and had earned its name purely by reputation (plus, its Vietnamese name was hard to pronounce.) In 1969, it’s what we called the village just outside the perimeter of FSB Sandy. Many a life and limb had been lost there whenever any army unit passed by or tried to pass through the village. All previous attempts to clear or secure the area had failed, including the latest attempt we all heard about when a platoon leader and his radio operator were blown to bits while on patrol outside the village and before they could take their first step toward its interior. The very dangerous condition of Boobytrap Ville was a significant problem because of its close proximity to the 101st Airborne Artillery installation (FSB Sandy.)

To make things worse, there must have been some good political or social reason not to just level the small town with an air strike of a few dozen 500lb. bombs or something equivalent. After all, it was known to be a virtual beehive of VietCong activity. Ok, “ours was not to reason why…,” but the fact remained that the village was extremely dangerous, and something had to be done about that. However, it was to be done, and civilian houses, livestock, and other private properties were to be left intact.

As fate would have it, company A/1/501 (101st Airborne) was called upon to secure the village. Making certain areas safe, secure, and free from Vietcong activity had always been our job. That part was nothing new. However, this particular “sweep” would be much more dangerous than usual because of all the boobytraps. Not one of us was looking forward to it. On the contrary… the place was a real nightmare, even in broad daylight.

The task of finding and disarming all the boobytraps one by one was not only way too dangerous but also would have taken about a year and probably caused several U.S. casualties. The village was known to have boobytraps by the hundreds in every direction. When we were first told about having “volunteered” to clear Boobytrap Ville, and before I had seen the place, I envisioned something similar to the file footage I’d seen on the evening TV. News back in the world.

That footage used to scare the shit out of me. (…the one where the large log with sharp wooden spikes sticking out from it swings down out of the tree tops with “…enough force and size to wipe out a whole squad of men.”) You could watch it coming at you for a second or two, but you couldn’t get out of the way. The ground was not low enough, and diving to either side was diving into a sea of pungi sticks. To me, having a few seconds to think before you die, and with no possible escape route, had to be the most miserable ending I could think of. A plane crash would be just as bad, but you could always hope the pilot would straighten things out… right up to the last second. At the very least, you might have time to say a prayer.

The operation to clear Boobytrap Ville was a big deal. As we prepared to enter the village and go to work, a couple of News crews from the States appeared with cameras rolling. Our CO at the time was one of those who rarely even made it out to the field, but he was there when the cameras started. Part of me was thinking that the REMF bastard had volunteered us for something impossible (again) to get a silver star or something for himself. Fortunately, another part of me was taking a strong stance at being whatever part of the third platoon I was supposed to be. We were all a little more scared than normal. There were a thousand crude ways to die in this village. Also, there was something terribly unfair about the boobytraps in general. Your assailant might be miles away. He might even be dead already.

Excuse our dust

We warned the village people that A 1/501 was coming in and that we would pretty much destroy every suspicious thing we discovered. There was supposed to be no one home when we came knockin’. If we encountered any humans, our first assumption would be that they were the enemy. That was the deal.

Even though our company commander was a glory seeker, we were fortunate to have an intelligent platoon leader. I had pictured us getting blown away one at a time until some honcho realized how futile the whole thing was and finally called it off. Our platoon leader had a much better plan (thank goodness.) He got on the horn (radio) and ordered all the Bangalore torpedoes in the battalion inventory to be choppered out to our location at the entrance to the village “… before we take one more step!”

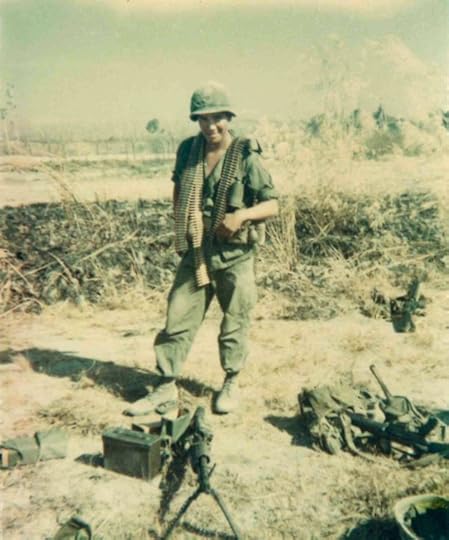

[ A Bangalore Torpedo is basically a ten-foot metal tube about three inches in diameter that are filled with a solid explosive material (TNT). They’re made to be linked or screwed together so that you can easily assemble a 25 or even a 50-yard pole of dynamite and shove it out in front of you. When the assembled shaft of explosives is detonated remotely via blasting cap and det cord (detonation), bingo, you have a fairly safe path to walk. You just do it again at the end of that short, safe path. ]

The Bangalores would be perfect for getting through the thick underbrush in the broad area that skirted the village. That’s where most of the booby traps were thought to be. They (the Bangalores) did a good job at not only clearing a clean path about 5 feet wide but also exposing countless hidden booby traps of every sort which were attached to bushes and trees. Some were detonated by the blast, some were not. After each explosion of a Bangalore assembly, we could clearly see where and how we would have died if not for the use of the “torpedoes.”

There were hundreds of pungi sticks protruding up out of the dirt. They had been hidden under the thick brush, but once all the vegetation had been blown away, we could see that there was a method to the placement of the deadly little (8 or 10-inch) bamboo spikes. Always in groups, they each pointed outward from, seemingly, one central point. If you followed them backward to see where the point was that they radiated from, you might find an entrance to a one or two-man underground bunker or “spider-hole.” The placement of the pungi sticks was crude and ingenious. The VC defending that spider hole didn’t even have to be a good shot. If he could just lob a grenade or fire close enough to make a man “hit the dirt,” that man would be impaled on at least one or two of the very pointed and dried-out bamboo steaks, which, by the way, were known to have been treated with some kind of poison. (Pig manure was commonly used for that poison because it would cause terrible infections.) I noticed, too, that sometimes there was not a “prize” bunker to be found near every grouping of pungi sticks. In those cases, the pungi-sticks were there to augment the threat of a certain boobytrap. If whatever explosive and shrapnel didn’t kill the person who triggered the trap, there was still a good chance that he and others would be maimed or killed when they hit the ground by reflex and impaled themselves on the pungi-sticks that had been stuck in the dirt surrounding the explosive device.

Some of the boobytraps weren’t meant to explode. I found something like a potato chip that could be buried to its rim in the dirt with steel spikes anchored to a flat piece of wood at the bottom. The top ends of the spikes were sharpened and had jagged barbs on them. Before the Bangalores blew it off, there had been some kind of camouflaged cover on the can. I could see that it was meant to be stepped on and that since the tips of the spikes were about halfway down in the can, your foot could pick up a little speed due to gravity before the spikes pierced your boot and foot. That trap probably wouldn’t kill you, but it would take you out of the war for a long time.

(Photo by Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)

(Photo by Rolls Press/Popperfoto via Getty Images/Getty Images)It got to be interesting after a while, finding unoccupied VC bunkers and having one of our smallest tunnel-rat-type guys crawl in and check for weapons and other trophies. We always looked for the next one once we knew what to look for. It could be the trap door entrance to a spider-hole if you saw what looked like a buried picture frame on the ground somewhere behind a group of pungi sticks. There would probably be a handle made of wire just beneath the dirt used to camouflage the square wood frame. Knowing this information would later, very nearly cost me my life. Meanwhile, we found a few weapons and many useless trinkets in several spider-holes to include: one each type, a nice white ladies bra. Go figure.

Of course, we stayed on the blown-up paths we had created with the Bangalores and other secured areas that had been checked by mine sweepers. However, we slowly eliminated all the boobytraps and generally cleared the whole village of anything useful to the VC, either offensive or defensive.

Don’t go there!

On about the third day of the operation, I was in place on a defensive perimeter that we’d set up for an incoming re-supply chopper. That meant little, except that getting my share of mail and rations would be … later. A short while after the chopper departed, we dissolved the hasty perimeter we’d set up, and I wandered over to where the mail was. I had a letter waiting for me from my wife, so I plopped down to read it a few times. I’d chosen a spot to sit where another guy was already reading his mail. That way, I’d hoped to borrow some of his “Do not disturb” atmosphere so I could read in peace. When we’d both finished our letters, he reminded me that we’d better go and get our food because if we waited any longer, we’d be stuck with the shitty(est) meals. He knew where the boxes of C-rations were, so I followed him up the slight rise out of the village and towards the flat sandy area where the chopper had landed and off-loaded our mail and supplies. I remember asking him if the sandy path we were using had been cleared, and I took his word for it, “Yeah, …it’s clear.”

We had walked no more than twenty yards or so when, to our delight, we ran upon what appeared to be a wooden frame half buried in the sand. It even had a bit of the wire handle exposed. We knew no one else had spotted it yet and quickly went into action, trying to gain entrance to the spider-hole below. He pulled the frame off of the hole using its wire handle. The frame was filled with just sand (in this instance), which was held in the frame by a woven bamboo mat. The whole thing was about a foot-and-a-half wide rectangular wooden structure. Most of them were usually beveled so that they wouldn’t fall in the hole they were meant to hide. This one didn’t seem to have that bevel. In fact, it looked poorly constructed compared to the others I’d seen. I noticed that one end of the wire handle of the lid looked shiny and new, though, which I took somehow to be a plus. However, the hole beneath the framed lid was mostly sand-filled. We were both there on our hands and knees, digging under where the frame had been and around it, looking for a way to get in. About five seconds later, the thought occurred to me that maybe the lid had been tossed there from the hole …which must be close by… and perhaps occupied… and a gook might be aiming his weapon at me right now. Before that thought was even complete, I started scanning the ground around me…weapon in hand. A small bush right next to my right leg held the only evidence of anything abnormal. A piece of dark gray plastic (as in an old garbage bag) had apparently been caught by the bush when the wind had blown it across the flat sandy plain. Perhaps it had even been blown from the re-supply chopper. Just because it was the only odd bit of interest, I lifted up part of it that was flapping loose. It was stuck, not just in the bush, but in the sand as well. In fact, there was a lot of it, and now I was sure something was wrapped up inside it that was meant to be hidden. I tugged at it and tore it open until I could see something inside.

To my utter shock, I was staring into the fuse assembly of the most deadly boobytraps I’d seen. It was made from a large U.S. (155) artillery round. Upon detonation, it would have easily disintegrated anyone within 15 or 20 yards and critically wounded those beyond. At the moment, it was no more than 10 inches from the tip of my nose. The (newish looking) wire “handle” of the wood frame had just been pulled out of the fuse when my partner hoisted the frame from the depression on the path. It wasn’t really a handle at all. By design, pulling that wire was supposed to detonate the boobytrap.

The framed mat and wire part of the boobytrap were meant to have been stepped on. That’s why it was on the path and why there was a small football-sized hole in the sand beneath it. Stepping on the mat and pushing it into the hole was supposed to yank the shiny end of the wire woven into the mat right out of the fuse on that artillery round. That’s all it took to trigger the explosion, and that wire had just been pulled. We hadn’t stepped on the triggering device, but just the same, we had yanked the wire loose when we were inspecting the frame and mat just seconds ago.

I’m sure we reported that boobytrap and its location to the proper authorities just before I went back to the perimeter and got sick. A cold sweat came over me, and I just sat there dazed beyond belief that I was still alive. The thing just didn’t go off. I couldn’t believe it. I had made a dumb mistake and was just sitting there, completely alive, wishing I hadn’t been so fatally stupid. It was a terrible “plus and minus” feeling, and even when I thought I’d shaken it off, it went no further than the back of my mind. The nightmares would last for years to come.

I didn’t even get angry with the guy who’d said the area had been cleared. It’s challenging to shout and swear when all the muscles in your throat are tied in a knot. Also, it’s difficult to muster or express rage on your knees. I had just made a deadly mistake, and yet, for some reason, the great judge in the sky found a reason to suspend my death sentence. That incident and others like it made me think that perhaps there was some purpose for me. The event did not add anything to the false sense of invincibility I carried around by default. I had no new feeling of divine protection. To be sure, I was as thankful as can be that such a critical moment had passed, and I was still breathing, but from then on, caution became an even bigger priority. It was nice to think that maybe God didn’t want me dead yet, but then there was the reality that 5 minutes later, I was still a fair target for the NVA or the Vietcong. I preferred to think of the experience as possibly my last and most final warning. Anyway, after that, I felt that if I ever got in a position where I needed to ask God for a second chance… he’d probably just laugh and say, “Remember that 155 round?” Yes lord… I remember.

As far as memories go, I have to admit that there are some memories of Vietnam that I can summon up, which are pleasant enough to drift me off into sleep land. That particular memory, though, always made me jump out of whatever relaxed state of mind I could achieve. For years after Vietnam, the thought of that 155-round boobytrap and actually remembering what its fuse looked like would cause physical tremors. At the same time, mentally, I could picture myself being sprayed across the sand like a blown-up can of red paint. Today, I can say, “Man, that was close!” However, they don’t quite describe the true nature of what happened. I can’t think of just one other time when a booby trap in Vietnam didn’t go off when it was supposed to. There’s just no such thing.

Other major mind-quaking events happened in that village. My life being spared is the first one that comes to mind. On the very first day of the operation, while we were waiting for the Bangalores, a good friend of mine who came out to the field on the same day that I did was hit in the leg by a piece of shrapnel from a boobytrap. That was before we had even entered the village.

Another thing that bothered me at the time was watching our Vietnamese scout slapping a little kid who we found wandering around at the edge of the village. He was yelling at the kid in Vietnamese, so I had no idea what the anger was all about. I had the utmost respect for our scout, but I felt like he was talking tougher to this little kid than he did to most any other of the adult VC prisoners we’d taken. I was about to stick my nose in and find out what they were talking about when the yelling stopped, and the little kid went (crying) into the very thick hedgerow at the edge of the village and pulled out a couple of hand grenades and an old SKS rifle with a few bullets. He had been working for the VC as a lookout.

He’d have probably worked for our side on another day. Kids like him found ways to make a good living by doing favors for (probably) both sides. They knew how to smile and con you into buying a hot can of stolen coke for a dollar or more, depending on how thirsty you looked. They always knew where to find cigarettes and other luxury supplies and would go to the nearest village and get them for you… for a nominal service charge. The kid with the weapons was taken prisoner. He was probably only about 11 years old.

A couple of days after the start of the operation, we encountered a very old man in the village. Again, I couldn’t understand the questions our scout asked the old guy, but he was not allowed to go free. His reasons for staying in the village after everyone had been warned to leave must have held at least a little suspicion. We detained and lightly restrained the old man and sat him in the shade where he could wait for someone “official” from the rear who would come out and question him further.

The “interrogator” arrived by chopper (l.o.h.) an hour later. He was from MACV, according to the patch on his shoulder, and looked so white and pudgy and pasty-faced that I figured it was the first time he’d ever been out of his air-conditioned office. He had a Vietnamese assistant/interpreter, although I soon heard he spoke a little Vietnamese himself. I witnessed his interrogation method for a minute, but it was cruel. The interrogator had an ammo can full of what looked like very soapy water and a blue washcloth. The old man was held down flat on his back on the ground, and each time the interrogator would ask him a question, the man would just seem to grunt or moan. Then the interrogator would drench the washcloth in the soapy solution and cover the old man’s mouth and nose, forcing him to inhale pure soap suds… or whatever else was in that solution. I don’t think they learned anything from the old man. In fact, I believe that after they gave up on the interrogation, the man died. It may have been a day or two later, but it wasn’t because of old age.

Epilogue:

Even today I still wonder why that place had more boobytraps than any other area or village in the I Corps. I have a guess, but it’s only based on things I’ve learned over the years since the war. From all I have heard about the massive underground tunnel systems the VC and NVA had in place, I could easily conclude that Boobytrap Ville must have been covering for some kind of underground hub, supply depot, or even a hospital complex. The bunkers we had found seemed to be in a pretty tight circle around the village, yet there was not that much (visible, at least) to protect. Before we cleared the place, there was no direction you could enter the village without risk of being blown to bits. If the bunkers had an armed man in them, no direction was left uncovered. Obviously, they were serious about protecting this place, but for why? None of us found any tunnels, but at the time, we didn’t know how to look for something beyond the inside of the bunkers and spider holes. I’ve seen a film showing that many of these spider-holes had a hidden entrance to an extensive tunnel system. I think that the village we called Booby Trap Ville might have been a VC version of the grand central station. Ya think?

We found many bunkers and boobytraps in that village and completely destroyed each one. After about a week, the place was safe to walk through for the first time anyone could remember. The 101st Airborne Division commander handed out a few medals in an impact awards ceremony a few days after the operation was completed.

Mark Orr

3rd Platoon

A/1/501

This story was obtained from http://www.lzsally.com

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 28, 2024

The Ballad of Charlie Papasan

A poem that tells a clever story of an incident during the Vietnam War.

Now a lot of strange stories have come out of Vietnam,

But sure none as bizarre as the tale of old Charlie Papasan.

It was way back in sixty-eight, not long after Tet,

Near some lush rice paddies, that me and Charlie met.

They sent us out to recon a hill called three-O-four,

But little did we suspect just what lay in store.

You see, that hill was empty except for one dead tree,

But hunkered down behind it was one toothless old VC.

Attired in black pajamas, not a hair left on his head,

This old Charlie Papasan already looked half dead.

He had a single shot rifle, it was dated nineteen and ten.

He`d fought the French and then the Japs and then the French again.

I guess old Charlie`d `bout had enough, having seen a lot in his days,

And like most old goats, he was kinda set in his ways.

So on that hill he sat above his paddy field.

Surrounded by our unit, he still refused to yield.

So we called him on the bullhorn: yelled, “Papasan, come on down,

We don`t want to hurt you, so don`t be screwin’ around.”

Then out of the barrel of his rifle, came old Papasan’s reply,

And we all sucked some mud as he let his bullets fly.

He answered us with a shot, the first one of the day,

But it was not to be the last, as we scrambled out of the way.

Now this went on for hours as we kept our faces to the ground.

We couldn`t even return fire as Papasan shot his rounds.

Our squad leader crawled to the phone and asked what he should do:

He reported we were under fire, had bit off more than we could chew.

HQ called back on the horn, said the word was “No Abort”

Our gung-ho looey said, “Can Do”, and called for air support.

So they sent in the flyboys to napalm that old VC

And they dropped tons of firecrackers targeting that old tree.

We waited for the smoke to clear and when it finally did,

There was old Charlie Papasan; still behind that stump he hid.

So they called in Special Forces, the Rangers, and Berets,

But old Charlie Papasan kept them pinned down for days.T

hen they tried offshore bombardment from every ship in the fleet

But all their shells missed Papasan by at least a hundred feet.

Then they sent for gunships and they came a spittin’ flame

But Papasan behind his tree just took more careful aim.

We watched in stunned disbelief as each Huey bit the dust

Brought down by old Papasan and his rifle lined with rust.

Finally our old Sarge just couldn`t take no more.

I saw him crawl off through the brush, and wondered what the hell for.

Then in a minute he was back and I knew where he`d had to go.

‘Cause here came Sarge a-leading Papasan’s water buffalo.

Sarge had out his .45 pointed at the dumb critter’s head.

He yelled, “Papasan, come on down, or your goddamn cow is dead!”

Now Sarge he`d done two tours; he was wise to the ways of the bush.

He knew Papasan would hurt no cow, if shove ever came to push.

So a thousand armed Americans encircling that hill and tree

All held their breath as one and sat waiting there to see.

Finally that ancient rifle came rolling down that hill.

Hands high, out came Papasan yelling, “NO KILL, NO KILL!”

Well, what happened to old Papasan, I guess you`d like to know,

Did we shoot the tough old bastard or did we let him go.

Well, we all looked at Sarge and this is what he`d done:

He traded Charlie that buffalo for that rusted out old gun.

So that old man just walked away with his water buffalo

Back to his lush rice paddies where you reap just what you sow.

And as I turned to look at Sarge I saw a sad look on his face.

He looked down at that rifle and said, “I`ll never understand this place.”–

Author Unknown –

Furnished by Wayne Hastings

B/1/501

Photo by Kenneth Lampert, Pixels

Originally posted on the LZSally.com website.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 21, 2024

Vietnam War Nurse Lou Eisenbrandt: A Story of Service, Healing, and Resilience

My friend Tim Hageman hosts an informational podcast called “Behind the Line,” which honors the selfless dedication of First Responders and Military Veterans. “We want to recognize the men and women who serve and protect our communities and our Nation and give them a platform to share first-hand accounts and real-life stories.”

The Behind The Line podcast values the dedication, sacrifices, and service of First Responders and Military Veterans.

In this episode of the Behind the Line podcast, Tim welcomes Lou Eisenbrandt, a Vietnam War nurse who served from 1967 to 1970, one of the 7,000 nurses who provided care during the war. Lou shares her journey from growing up in Mascoutah, Illinois, to joining the United States Army, and her experiences in Vietnam, including the rigorous training, adjusting to the military culture, and serving as an emergency room nurse treating severe injuries.

She also discusses the emotional challenges of dealing with wounded soldiers, the significance of holding hands with dying soldiers, and her struggle with Parkinson’s disease linked to Agent Orange exposure. Lou reflects on her return home, the societal reception of Vietnam War veterans, her multiple visits back to Vietnam, and her published works that capture her remarkable journey.

This episode is a heartfelt and insightful exploration of the courage, dedication, and resilience of the ‘Angels of Mercy.’

#####

ADMIN: I had an earlier article about Lou on this website four years ago. If you are interested in reading more about her, then please click on the following link:

A VETERAN’S STORY: One Vietnam nurse, mending and remembering

If you would like to watch more of Tim’s podcasts, please visit:

https://www.behindthelinepod.com/

Tim would like to hear from you if you are a military veteran with a story. Please contact him via his website.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 11, 2024

“SO FREEDOM WILL LAST “

By Les Davenport·

Away from home, in a faraway land.

His duty has called him…he knows the command.

To say he’s not afraid..would just be a lie.

But for the love of his country, he’s willing to die.

He remembers his family, the laughter the joy.

He remembers the school days, when only a boy.

But being a soldier, he walks a new road.

He weathers the bad times, the rain and the cold.

Oh it isn’t for money to do such a task. Then why would he do it, the critics will ask.

Yet we see the flag flying, meaning liberty to all.

But Freedom isn’t cheap…for many will fall.

Like those before him, in wars of the past…he asks not for glory. But that Freedom will last

So what can we do for this Freedom to stay?

Let’s call on the brethren..they know how to pray.

Say “Father in Heaven ” We’re calling on you…you have all the answers. You know what to do.

Our young men are dying…..as those in the past.

God bless our dear soldiers….SO FREEDOM WILL LAST.

Les Davenport 2012

September 8, 2024

This ‘Puerto Rican Rambo’ Went On 200 Combat Missions in Vietnam

Otero Barreto survived five tours in Vietnam between 1961 and 1970. During that time, he volunteered for 200 combat missions and earned 38 total commendations, including three Silver Stars, five Purple Hearts, five Bronze Stars, five Air Medals, and four Army Commendation Medals. Read his story here:

By Jon Simkins Military Times

Eloy Otero-Bruno and Crispina Barreto-Torres welcomed a son into the world on April 7, 1937, in the small municipality of Vega Baja, Puerto Rico, just west of the island’s capital of San Juan.

When they gave him a name inspired by his father’s admiration for America’s first president, the family certainly had no inkling that little Jorge would one day be something of an American icon in his own right, a status earned after becoming one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War.

Jorge Otero Barreto joined the Army in 1959 after pursuing biology studies in college. Less than two years later, he embarked on his first deployment, one of five such tours he would make to the embattled nation between 1961 and 1970 as a member of the 101st Airborne, 82nd Airborne, and 25th Infantry Division, among others.

Over the course of five deployments, Otero Barreto volunteered for approximately 200 combat missions — a lofty number that eventually earned him the moniker “The Puerto Rican Rambo,” after the fictional death-dealing character made famous by actor Sylvester Stallone.

One particular award was the result of actions on May 1, 1968, when the platoon sergeant, along with men from the 101st Airborne Division, nestled into positions designed to pin down a North Vietnamese regiment in a village near the deadly city of Hue.

In the early morning hours, Otero Barreto and his men came under a heavy bombardment and faced waves of charging enemy soldiers desperate to rid themselves of the incoming Americans.

U.S. troops managed to repel the first two enemy assaults, killing 58 in the process and forcing the assailants to limp back to the village.

Instead of awaiting a third assault, Otero Barreto opted to lead a counter-attack. But shortly into their advance, the first platoon came under a barrage of machine guns, small arms, and rocket-propelled grenade fire from enemy spider holes and bunkers strewn across the platoon’s fire sector.

The Puerto Rican Rambo wasted no time getting to work.

Otero Barreto sprinted to the nearest machine gun bunker and quickly killed the three men manning the position.

Gathering the rest of his squad, he moved through three more fortified enemy bunkers, dashing from one to the next until all that remained was a trail of destruction.

The assault by Otero Barreto, which allowed the rest of Company A’s platoons to maneuver into advantageous positions and overrun the enemy, would earn him one of his three Silver Stars.

Otero Barreto, now 85, would later retire as an E-7 (sergeant first-class). And while the eventual conclusion of Vietnam would mark the end of his extensive combat career, it would not be the last of his many lifetime achievements.

In 2006, Otero Barreto was named the National Puerto Rican Coalition’s Lifetime Achievement Award recipient. Since then, veterans’ homes and museums have been named in his honor, and in 2011, the city of his hometown recognized him when it named the Puerto Rican Rambo its citizen of the year.

Read more about Otero Barreto via one of his Silver Star citations here:

https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/113830

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

September 1, 2024

Native Americans in the Vietnam War

T. C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa, 1946–1978), On Drinkin’ Beer in Vietnam, 1971. Lithograph on paper, 48 × 76 cm. Collection of Museum of Contemporary Native Art.

This print depicts the artist and his friend from home, Kirby Feathers (Ponca), at a Vietnamese bar. Though stationed just miles apart, they only met once in Vietnam. Cannon was conflicted by his service; a mushroom cloud—a symbol of that conflict—appears in the background. Cannon was a member of the Kiowa Ton-Kon-Gah, or Black Leggings Warrior Society.

Approximately 42,000 American Indians—one of four eligible Native people compared to about one of twelve non-Natives—served in the armed forces during the war in Vietnam (1964–1975). Many were drafted, but many volunteered, often citing family and tribal traditions of service as a reason.

Native Americans served valiantly in the Vietnam War as they have in all of the United States’ conflicts.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Department of Defense did not keep records on the numbers of Native Americans who served in the armed forces, but scholars estimate that as many as 42,000 Native Americans served in the Vietnam War. Unrecognized by the Department of Defense or service branches, these Native American servicepeople were sometimes mislabeled as whites, Latinos, or even Mongolians. Although exact numbers are impossible to verify, some studies find that Native Americans were more likely to serve in combat units. One assessment of 170 Native Vietnam veterans found that 41.8 percent of those surveyed served in infantry units, while nearly another quarter served in airborne or artillery units. Several sources insist that 232 Native Americans died in the Vietnam War and are listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC.

Courtesy of Harvey Pratt

Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho, b. 1941) holds a Naga knife—a Southeast Asian knife used for cutting through vegetation—during the camouflage and evasion portion of ambush training for his service in Vietnam in 1963.

Motives for Service

Native Americans enlisted or accepted induction into the military during the Vietnam War for a variety of reasons. Patriotism and concern for democracy’s survival in the Cold War inspired many Native Americans in the same ways that these motivations affected members of all races and ethnicities in the United States. Other sources of inspiration may have been more specific to Native communities’ traditions and cultures. Historically, in Native societies, most men share the collective responsibility of protecting the tribe or community from outside aggression. Native American beliefs commonly insist that military service and the experience of combat steels young men, transforming them into future leaders. Proximity to danger, violence, and death, these traditional views maintain and implant wisdom, acumen, and respect in those who pass the test of combat. Furthermore, in some Native communities, traditional practices require that men demonstrate martial and religious prowess to be considered full-fledged members of the nation.

During the Vietnam War, young Native Americans surely heard stories of their fathers’ and grandfathers’ service in the world wars and Korea, and they viewed the conflict in Southeast Asia as their opportunity to demonstrate prowess and earn the esteem of their elders and peers. Moreover, some Native societies traditionally afforded young, unmarried men little social prestige within the tribal community. For young men in these environments, military service offered an opportunity to escape their hometown and return as an independent and mature member of the tribe or community.

Potawatomi Traveling Times

Ernie Wensaut (Forest County Potawatomi, b. ca. 1945) checking his gear before a patrol mission near the Cambodian border in the highlands of Vietnam in March 1967. A member of Company C, 2nd Battalion, 10th Infantry, 1st Division (also known as the “Big Red One”), Wensaut was an M-60 machine gunner whose weapon, nicknamed “The Pig,” fired 500 to 600 rounds per minute.

Additionally, some Native Americans may have enlisted or accepted induction because they believed they owed service to the United States due to treaties that their nations had concluded with the Federal Government in the past. These individuals likely acknowledged that the United States repeatedly broke its treaty promises with Indian nations, but members of these nations may have remained committed to upholding the alliances their ancestors had made with the United States. Lastly, there surely were some Native Americans who volunteered for military service during the Vietnam War to escape poverty and the lack of opportunities in the cities, small towns, and Indian Reservations where they lived.

“Indian Scout Syndrome”

In Vietnam, Native American servicepeople faced racist attitudes held by non-Native officers and enlisted men. Some scholars have labeled this prejudice “Indian Scout Syndrome.” This racist caricature, which existed long before the Vietnam War, assumed that Native Americans possessed superior senses and an instinctive understanding of nature. Therefore, all Indians were natural scouts, trackers, or snipers. This stereotype sometimes led to higher numbers of Native Americans being assigned to the most dangerous duties in combat units, such as having to “walk point” or go on reconnaissance patrols. Some Native Americans embraced this warrior image and volunteered for the most dangerous missions.

Sergeant Billy Walkabout, a Cherokee from Oklahoma who served as an Army Ranger with the 101st Airborne Division, was the most decorated Native American serviceman in the Vietnam War. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroic combat actions outside of Hue in November 1968. Although numerous Native Americans, such as Walkabout, took pride in the warrior ethos, many Native Americans likely fell victim to a different type of discrimination.

Accounts from Vietnam reveal that some officers assigned Native Americans to the most mundane and menial tasks as a result of stereotypes that regarded Indians as untrustworthy, lazy, or stupid. Anxieties prompted by cultural and racial differences between the Americans and Vietnamese even found their way into the Vietnam-era parlance used by service people. Firebases were colloquially known as “Fort Apaches,” and former Communists who chose to collaborate with the South Vietnamese or Americans were “Kit Carson Scouts.” The phrase “Indian Country” referred to remote areas in the Vietnamese jungles and mountains infested with the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese. Patrols in “Indian Country” likely meant ambushes and booby traps, and since these encounters happened far from urban areas, media reporters, and high-ranking officers, the normal rules of engagement sometimes were believed to be suspended.

In one study, some Native American veterans expressed dismay that atrocities they had witnessed in Vietnam’s “Indian Country” mirrored crimes the United States government had committed against their own people. To some observers, the war in Southeast Asia resembled a foreign invasion in which outside militaries targeted civilians, stole land, and resettled survivors in refugee camps. Meanwhile, some Native servicepeople expressed sympathy for indigenous Montagnard peoples, who wished to maintain their independence, practice their traditional lifestyles, and remain outside of the conflict. Native American cultures often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat

Native American societies often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat.

Cultural Attitudes and Practices in War

These practices existed long before the 1960s—there are accounts of similar rituals during World Wars I and II—but Native Americans continued these traditions during and after the Vietnam War. Numerous nations require veterans to perform ceremonial and religious functions at powwows and tribal gatherings. In many cases, older males count coups or recount stories of martial prowess to reinforce tribal solidarity, language, history, and identification with the homeland. Other ceremonies mark the transition from war to peace and vice versa. The Navajo, for example, have been known to perform a dance ceremony called the “Enemy Way” for members of the tribe on their departure and return from war. This ceremony reenacts a traditional story as a means of suspending the rules prohibiting violence before the warrior departs, and it restores the rules of peacetime upon the warrior’s return. Navajos and Cherokees employ similar ceremonies intended to exorcise the demons of war from those reentering the peaceful community. In other nations, medicine men or shamans perform rituals to help individuals heal the scars of combat or protect loved ones at the front. Elders and parents often provide gifts and tobacco and say prayers to ensure protective medicine watches over warriors when they are away. Although servicepeople in the Vietnam War departed and returned at different times, evidence suggests that Native American communities continued to employ traditional ceremonies throughout this era. The practice of certain rites and traditions may have become more widespread after the war as a result of the hardships suffered by Native service people in Vietnam.

Courtesy Donna Loring

Donna Loring, 1966.

Loring (Penobscot, b. 1948) served in 1967 and 1968 as a communications specialist at Long Binh Post in Vietnam, where she processed casualty reports from throughout Southeast Asia. She was the first female police academy graduate to become a police chief in Maine and served as the Penobscots’ police chief from 1984 to 1990. In 1999, Maine governor Angus King commissioned her to the rank of colonel and appointed her his advisor on women veterans’ affairs.

Native American veterans of the Vietnam War stand in honor as part of the color guard at the Vietnam Veterans War Memorial. November 11, 1990, Washington, D.C. (Photo by Mark Reinstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Coming Home and Recovery

Several studies have found that Native Americans suffered from the physical and psychological traumas of combat at higher rates than other servicemembers following the Vietnam War. Poor employment prospects on reservations and in rural areas, combined with inadequate access to medical and psychological care, exacerbated the problems many Native veterans faced. A widespread reluctance to speak with outsiders or admit to shameful behavior or conduct encouraged some Native American veterans to forego programs designed to help them cope with the traumas of combat. Several sources indicate that alcoholism and substance abuse among Native American Vietnam veterans was widespread, especially during the first two decades following the conflict.

The United States government failed to devote special attention to the plight of Native veterans until the 1980s. Despite these difficulties, the Vietnam War inspired many Native American veterans to reconnect with their cultures and reinvigorate their communities. The war and emergence of social justice movements politicized Native veterans in new ways, and many veterans became active in tribal governments and cultural associations. During the decades following World War II, the Federal Government slowly eliminated many aspects of tribal sovereignty during a process named Termination. The goal of Termination was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society by breaking up the reservations. Native Americans resisted these infringements on their rights by strengthening tribal governments, protesting injustice, battling these policies in courts, and restoring tribal customs, languages, and education. Historians have labeled this period of Native activism the Red Power movement. Many Native activists who took part in the 1970s Red Power movement were Vietnam veterans, including a large number of the American Indian Movement (AIM) protestors who organized the Wounded Knee standoff against federal law enforcement agencies in 1973. This violent occupation and standoff resulted in a 71-day siege and the death of two protestors.

Most Native Vietnam veterans, however, affected positive change through peaceful methods. They took on prominent roles in tribal councils on reservations or became participants in cultural or social justice organizations in towns and cities. Some of the most prominent of these voluntary associations are known as warrior societies, which were established by many nations and tribes throughout the United States and Canada during the 1970s and 1980s. In many nations, such as the Kiowa, Comanche, Lakota, Chippewa, and Cheyenne, certain tribal functions can only be performed by veterans. Vietnam veterans have fulfilled and continue to serve in these leadership roles in the present day.

National Native American Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located at The Highground in Neillsville, Wis.

This post originally appeared on THE UNITED STATES 50TH VIETNAM WAR COMMEMORATION website: https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/assets/1/7/NativeAmerican_Posters_FINAL.pdf

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 25, 2024

PROFILES IN COURAGE: ROBERT L. HOWARD

The last time someone received a second Medal of Honor was in World War I, and it’s unlikely we’ll ever see another two-time recipient in our lifetime. But if anyone were going to come close to receiving multiple Medals of Honor, it would have been U.S. Army Col. Robert L. Howard. During his 54 months of active combat service in Vietnam, he was wounded an astonishing 14 times and received eight Purple Hearts and four Bronze Stars.

He was also nominated for the Medal of Honor three times in 13 months, the only soldier ever to receive three nominations. Two of those were downgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross and Silver Star because his actions took place in Cambodia, where the United States wasn’t technically at war. He would be awarded the medal on his third nomination, forever changing his life and career.

Alabama-born Howard enlisted in the Army in 1956 and would spend the rest of his working life serving his country. Some 36 of those years would be spent in the Army, first as an enlisted Special Forces soldier, then as a Special Forces officer. He was a Staff Sergeant when he was sent to Vietnam as part of the secret Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group (MACV-SOG) in 1967. It was the first of five tours in Vietnam.

In December 1968, he was on a rescue mission looking for six missing American soldiers. It was a mixed American-South Vietnamese Hatchet Force based in Kon Tum. It was a platoon-sized force that would be inserted by helicopter into the soldiers’ last reported location. As they moved to the landing zone, his force began taking ground fire and casualties. Immediately upon landing, he took three men to secure a perimeter. The incoming fire caused him to fall.

His three men were killed immediately. Two companies of enemy troops completely surrounded the LZ. One of the helicopters had been shot down. They had to fight their way out of the drop zone and made a move for the high ground. Howard pushed his way to the front of the unit, but before he could warn his lieutenant about enemy fire from their flanks, they were ambushed – and had walked right into it.

Howard had been hit by a grenade, his weapon destroyed. When he came to, his platoon was in disarray, and he was left temporarily blinded. When his vision returned, he realized his hands were wounded, and the enemy troops were burning the Americans with a flamethrower. Howard got up and pulled his lieutenant down the hill. As he moved, he acquired a sidearm from an unhurt-friendly soldier just as the North Vietnamese came running out of the bush.

He killed two of the attacking enemy soldiers before he was hit yet again. One of the rounds hit the rifle magazines on his belt, causing them to explode. Out of ammunition, he returned to the landing zone, now a casualty collection point. He ordered that every wounded soldier in the field be treated while every unharmed soldier rallied to his position. In the melee, he’d seen soldiers watching his comrades being shot up by the enemy and not even firing their weapons. He told the men who had watched without fighting that they were going to establish a perimeter and that they were either going to fight or die.

“I want you to get every live person we’ve got that’s able to fight,” he told a wounded medic through gritted teeth. “I want to talk to them right now.”

He located three strobe lights and assembled them in a triangle around their position, got on the radio, and called in an airstrike on their position, hoping the incoming aircraft could avoid hitting the friendlies inside the strobes. They fought for four hours without help before Air Force pilots 20 minutes away volunteered to make a rescue attempt. Before the airmen could arrive, the North Vietnamese made another desperate charge. Howard was forced to order an airstrike on his own position.

The incoming air power was so intense the fire from the assault struck close to his feet. But as the airstrike receded, the sound of helicopters replaced it. The Air Force was able to extract what was left of his platoon. Of the 37 troops who went into the landing zone that day, only six walked out. Howard was the last man on the helicopter, waiting until everyone else had been evacuated first.

For his gallantry and the reorganization of his battered platoon, Robert L. Howard received the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon in a White House ceremony on March 2, 1971. He would become one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam War and would serve until 1992. In his post-military career, he would work with veterans in Texas. Howard died on December 23, 2009, and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.

This article originally appeared on the Together We Served Website. Here is the direct link:

https://army.togetherweserved.com/army/servlet/tws.webapp.WebApp?cmd=DispatchesArchive&type=NewsArticle&ID=1570*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 17, 2024

FIREFIGHTS AND COURAGE

What goes through an infantry officer’s head during a firefight? Fear and indecision can get everyone killed, a soldier must overcome it and trust in his training. Here’s one platoon leader’s take on it.

By Robin Bartlett

John Wayne, who never served in the military but is revered by all branches of the service, may have said it best: Courage is being scared to death but saddling up anyway.

Courage under fire is something all grunts (infantrymen) thought about in Vietnam. My firefights, as a combat infantry platoon leader, came in a variety of forms: a skirmish with one or two enemy soldiers walking down a trail or a short but ferocious ambush initiated by our own soldiers or the enemy, often resulting in the immediate death of those ambushed. There were times when I was engaged in a firefight during a helicopter combat assault into a hot LZ. My worst firefights were those that occurred at night. This may have been an attack against our dug-in company’s NDP (night defensive perimeter) by an enemy using mortars and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). Night fights meant fear, chaos, and confusion because of the darkness and uncertainty of enemy movement. The enemy were masters of night fighting, and on at least one occasion, we defended our firebase against a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) force. In this battle, “Sappers” would try to penetrate the perimeter wire and throw satchel charges into command bunkers.