John Podlaski's Blog, page 2

September 6, 2025

Emotional speech honors Vietnam War veterans

The following speech includes a call to action to each of us. Please heed the advice given.,

By John Stewart

Recently, I spoke at a very special sunrise service honoring Vietnam War veterans from across Nebraska.

You may be asking yourself why I am writing about an event in another state. I want the people of Citrus County to fully understand the difficulties faced by Vietnam War veterans. And perhaps my words below will be of help to anyone in need here.

In 1985, a group of military veterans from World War II and the Korean War formed the Nebraska Vietnam Veterans Reunion (NVVR). As time and the age of personnel passed, the 20-member managing committee became increasingly dominated by Vietnam War veterans and their family members.

The purpose of NVVR was simply to have Vietnam War veterans a reunion avenue for sharing and healing. However, it was now coming to an end due to the age of the committee members, with no one else stepping forward to continue the program.

The sunrise service followed a day-before banquet attended by approximately 650 Vietnam War veterans and family members from across the state. The planned keynote speaker, Nebraska’s governor, was forced to cancel his banquet appearance due to other commitments. Scrambling to find a replacement, I was contacted and agreed to substitute for the governor.

In my 30 years of being heavily involved with the support of veterans, from an emotional stance this was the most difficult task I have ever done.

Recovery, honor, and trustThe main subject of my speech was recovery. I spoke about the difficulties we faced when coming home from the Vietnam War after experiencing the horrific actions of combat and returning to be insulted by those demonstrating against that war, despite the fact that we were in need of recovery.

But while in combat in Vietnam, I said we had two other words that were nearly as important to us as recovery upon return: honor and trust.

A perfect example of honor was in our young soldiers. Of those killed in Vietnam, 61 percent were 21 years old or younger, while thousands of them were only 18 years old.

Imagine you had just graduated from high school, and you are still three years away from being able to vote and drink alcohol legally. You may have never had a driver’s license. Then, you are drafted into the Army and spend eight weeks learning how to use a rifle and a pistol, a machine gun, a grenade and a bayonet.

Then told to go and serve and kill people … while serving with honor.

Those 18-year-old kids may not have been able to put it into words, but they quickly learned what honor was to be. They were doing their best to fulfill their mission and defend and protect their fellow soldiers. Even if risking their own life was necessary.

And for those 18-year-olds, the second important word came into their lives: trust.

They realized their brothers trusted them to do their mission, even if under heavy fire, and their lives were at risk.

Teenager or not, honor and trust were also two words every single one of us, regardless of age, lived by while serving alongside our brothers-in-arms in Vietnam. However, after thinking about it, I said a third word is necessary to describe us in Vietnam: courage.

Serving with courageWhen one of our brothers-in-arms was killed, it was horrific, and we did what soldiers have to do. We cried but crammed our anguish and sorrow way down deep inside into our own secret box and we closed the lid tight so we could carry on doing our job … with courage.

But then, one day, we who survived and fought with courage and honor and trust finally came home. But, for many of us upon return, the war never ended. And that word, recovery, came into the forefront.

It is difficult for some people to understand our mental status when on Thursday we could have been in a firefight or watching a village burn or watching friends die, and on Sunday our tour was over, and we were flown out to find ourselves at LA International Airport watching Americans protest our service and sacrifices and calling us baby killers.

We needed recovery from our nightmares.

Many of us committed suicide at some point after returning to that horrific welcome home. And there were a lot of suicides. It is difficult to obtain accurate figures of how many of us did so, but the Veterans Administration (VA) and National Library of Medicine did issue reports covering the 1979 through 2019 suicides of veterans of the Vietnam War era. The number was rather unbelievable.

To put it into perspective, if every citizen of Inverness and Ocala died today, it would be less than the number of veteran suicides in VA’s report. Over 94,000 were in that report. And there are many more years of suicide numbers not included in it.

I often wonder how many of those veterans could have been saved if they had been welcomed home and provided adequate recovery programs.

I told the crowd there were probably some in the banquet room who needed recovery and, fortunately, did reach out for help. However, some of us present may not have sought recovery upon return from the hell of Vietnam due to our post-traumatic stress. I followed that by stating there are probably several reasons why we did not do so.

How could we possibly tell some stranger about the atrocities we had faced?

How could anyone who had not been there understand what we had been through?

We killed people or saw others who did so. We saw our friends get killed or wounded. We held them in our arms and cried. We were shot, blown up, and maimed.

We came home and were told not to wear our uniforms in public because it was dangerous. Uniforms we wore and served with courage, honor, and trust.

We came home and were cursed at, spit on, and humiliated for our service.

And we suffered.

Many of us went looking for comfort in a bottle, in a needle, became homeless, considered committing suicide … or actually did it.

We needed recovery and honor, but many did not receive it, and many of us did not seek help.

Getting the help we needI was one of them and told my own story. I’ll not repeat it here because once was enough in discussing my difficulties and an extremely close moment in my life of nearly committing suicide. I used my story last night to encourage those in need of help to get it as I did.

After my speech, veteran after veteran and family member after family member came up to me to tell their own story of sacrifice, service, and suffering. Many were in wheelchairs, or using strollers or canes, missing both legs, an arm, an eye, or suffering from other injuries after being wounded in Vietnam.

Many were without any physical injuries, but obviously suffered from what I could readily see were mental health issues.

My most emotional moments occurred when multiple spouses of veterans came up to me and said their husbands needed help with their PTSD, never went to get it, and after my speech, I told them they would go get help. Their hugs will never be forgotten.

I held my tears back as best I could, but it was difficult until I returned home and began writing this article immediately. And, as I sit here with keyboard in hand, in all honesty, tears are rolling down my face from my experiences these past few days during this last reunion.

There is no actual number of how many Vietnam War direct-combat veterans reside in Nebraska, just as it is not found in Florida or throughout America. Florida has approximately 423,000 Vietnam-era veterans, according to the Florida Department of Veterans’ Affairs in March 2025. It is challenging to find an exact number for combat veterans, specifically, as statistics often refer to the broader “Vietnam-era” designation.

Regardless of the number, I am certain that many who served in combat or simply in uniform at other locations during that turmoil are now in need of help. For those reading this article in that situation, here are possible avenues to achieve it:

Visit your church and speak with a minister. Ask for help to recover.

Go to the Veterans Service Office (VSO). They will help you get to available VA recovery support programs. In Citrus County, you have the best VSO I’ve seen over the past 30 years.

Go online at VA.gov where you will find an enormous number of methods to achieve recovery.

Use your cellphone and dial 988, then press 1 for 24/7, confidential crisis support. By the way, that crisis line is also for military family members.

Whatever method you choose, if you need help, follow my example. Go get recovery.

I hope and pray that if there are some in Citrus County’s thousands of veterans experiencing problems and needing help, they will take my advice.

A special messageA few minutes before I departed for home from my speech that night, ironically, I received a forwarded email that I believe says in its entirety what America should have said to the Vietnam War veterans upon their return. I read it to the audience and have extracted a portion of that email for you below.

It is from Anne Zimbler, World Airways flight attendant, 1970-73.

“What many of you may not know is how much your cabin crews cared about you. It would have been unprofessional for us to have shown you the tears we held until you deplaned in Vietnam. We worried about you and said silent prayers for your safe return. We cherished our time with you and tried to make you as comfortable as possible. Most flight attendants, from the many airlines that flew military charters during that era, would tell you we truly treasured our military passengers.

“… on behalf of the cabin crews who brought you home, we thank you for your bravery, dignity, and service. We will always remember your faces and the many conversations some of us had with you on those long trips over the Pacific. In our minds, you remain young men who served your country and graced our lives for a moment in time, many years ago, during a difficult period in our shared history.

“You are still, and will always be, our heroes … welcome home.”

To my brothers-in-arms, as I sit here in tears, I echo Anne’s final comment.

Welcome home.

John Stewart is a retired Air Force Chief Master Sergeant and disabled Vietnam War veteran. In 2016, he was inducted into the Florida Veterans Hall of Fame. His columns are sourced from public, government, and private information, and the content is checked for accuracy as best as possible. However, you have the responsibility to verify the contents before taking any related action.

*****

Anne Zimbler recently contributed an article to this website. Read it here: https://cherrieswriter.com/2025/08/16/the-freedom-bird/

Here is the direct link to the article on Citris County Chronicle: https://www.chronicleonline.com/lifestyle/veterans/emotional-speech-honors-vietnam-war-veterans/article_f6d41212-f9ab-538b-92fe-b588f7488cbf.html

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 30, 2025

Bronco Pilot gives his life to save his observer.

The story of the Bronco pilot who died after ditching his OV-10 to save his observer, who couldn’t eject because his parachute was shredded by the explosion of a North Vietnamese SA-7.

By Dario Leone

Jul 10 2023

Captain Bennett elected to ditch in the Gulf of Tonkin, although he knew that his cockpit area would very likely break up on impact. No pilot had ever survived an OV-10 ditching.

The OV-10 was a twin-turboprop short takeoff and landing aircraft conceived by the US Marine Corps and developed under a US Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps tri-service program. The first production OV-10A was ordered in 1966, and its initial flight took place in August 1967.

The Bronco’s missions included observation, forward air control, helicopter escort, armed reconnaissance, gunfire spotting, utility and limited ground attack. The USAF, however, acquired the Bronco primarily as a forward air control (FAC) aircraft. Adding to its versatility is a rear fuselage compartment with a capacity of 3,200 pounds of cargo, five combat-equipped troops or two litter patients and a medical attendant.

The first USAF OV-10As destined for combat arrived in Vietnam in July 1968. A total of 157 OV-10As were delivered to the USAF before production ended in April 1969.

On Jun. 29, 1972, Captain Steven L Bennett, a USAF FAC, was flying an OV-10 Bronco on an artillery adjustment mission near Quang Tri City, South Vietnam. A Marine gunfire spotter occupied the rear seat of the lightly armed reconnaissance aircraft.

According to Air Force Historical Support Division, after controlling gunfire from US naval vessels off shore and directing air strikes against enemy positions for approximately three hours, Captain Bennett received an urgent call for assistance. A small South Vietnamese unit was about to be attacked by a much larger enemy force. Without immediate help, the unit was certain to be overrun. Unfortunately, there were no friendly fighters left in the area, and supporting naval gunfire would have endangered the South Vietnamese. They were between the coast and the enemy.

Capt Steven L Bennett, Medal of Honor recipient, Vietnam

Capt Steven L Bennett, Medal of Honor recipient, VietnamCaptain Bennett decided to strafe the advancing soldiers. Since they were North Vietnamese regulars, equipped with heat-seeking SA-7 surface to air missiles (SAMs), the risks in making a low-level attack were great. Captain Bennett nonetheless zoomed down and opened fire with his four small machine guns. The troops scattered and began to fall back under repeated strafing.

As the twin-boomed Bronco pulled up from its fifth attack, a missile rose up from behind and struck the plane’s left engine. The explosion set the engine on fire and knocked the left landing gear from its stowed position, leaving it hanging down. The canopies over the two airmen were pierced by fragments.

Captain Bennett veered southward to find a field for an emergency landing. As the fire in the engine continued to spread, he was urged by the pilot of an escorting OV-10 to eject. The wing was in danger of exploding. He then learned that his observer’s parachute had been shredded by fragments in the explosion.

Captain Bennett elected to ditch in the Gulf of Tonkin, although he knew that his cockpit area would very likely break up on impact. No pilot had ever survived an OV-10 ditching. As he touched down, the extended landing gear dug into the water. The Bronco spun to the left and flipped over nose down into the sea. His Marine companion managed to escape, but Captain Bennett, trapped in his smashed cockpit, sank with the plane. His body was recovered the next day.

For sacrificing his life, Captain Bennett was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. The decoration was presented to his widow by Vice President Gerald R. Ford Aug. 8, 1974.

A US Air Force North American OV-10A Bronco firing a smoke rocket in the area north of Saigon in February 1969 to show where the North American F-100D Super Sabre should drop its bombs. The F-100 was assigned to the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron, 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing, at Bien Hoa air base. Photo credit: U.S. Air ForceDario Leone

A US Air Force North American OV-10A Bronco firing a smoke rocket in the area north of Saigon in February 1969 to show where the North American F-100D Super Sabre should drop its bombs. The F-100 was assigned to the 531st Tactical Fighter Squadron, 3rd Tactical Fighter Wing, at Bien Hoa air base. Photo credit: U.S. Air ForceDario LeoneDario Leone is an aviation, defense and military writer. He is the Founder and Editor of “The Aviation Geek Club” one of the world’s most read military aviation blogs. His writing has appeared in The National Interest and other news media. He has reported from Europe and flown Super Puma and Cougar helicopters with the Swiss Air Force.

Here’s the link to the original article:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 24, 2025

My Father’s Vietnam

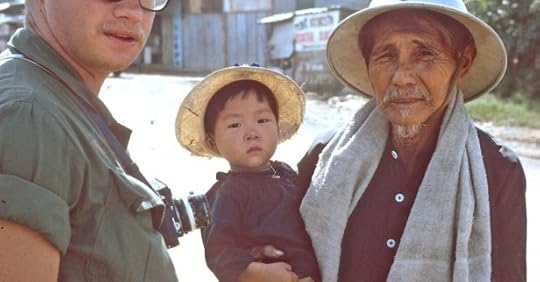

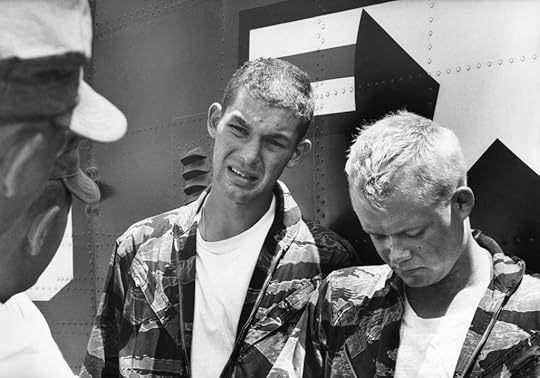

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999

In 1999, one former combat soldier from the Army’s Fourth Infantry Division in Vietnam sent a package to his son comprised of words and photos regarding his time during the war. Check out the photos and read what his son had to say about the package.

BY JON MEACHAM

Thirty years after everything happened–and 31 years since he had first set foot in Southeast Asia–my father, a soldier of the Fourth Infantry Division, wrote me a letter. It was 1999, and the note came with a set of recently rediscovered photographs he and his friends had taken with an old 35-mm Minolta in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. There were images of impossibly young men, their helmets heavy on their heads, carrying M-16s, smoking cigarettes, and trying to look happy–itself a form of bravery. There were pictures of the lush landscape and of villagers going about their business, drawing water and sitting, watching, some blankly, all warily.

My father’s words, though, were the most poignant part of the package. “I thought you might like to have these,” he wrote me. “You are the historian, and I know you will preserve them. I remember the brutal heat, the more brutal humidity, the chop-chop-chop of the helicopter blades, and elephant grass that could cut men up like a knife. And I remember many things that I have never told you or anyone. Those are the demons that I will always bear. South Vietnam, for me, is a place I’ve never really left.”

Neither, truth be told, has America. As I watched Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s illuminating 10-part documentary The Vietnam War, I thought often of my father and, inescapably, of his “demons.” He hinted from time to time about harrowing firefights with enemy soldiers but offered no details. The numbers tell a grim story: from 1966 to ’70, 2,500 fellow members of what’s known as the “Ivy Division” died; 15,000 were wounded. For my father and so many other veterans, the battles never genuinely ended. Over the decades, casualties of this perpetual war included emotional stability, peace of mind, marriages, and, more broadly, America’s sense of virtue and of self-confidence.

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999 Courtesy Jon Meacham

The power of Burns and Novick’s documentary lies in its remarkable capacity to tell the story of the struggle in terms both particular and universal. This is part historical narrative, part cultural exploration, and part therapy–the last made even more effective by its subtlety. Burns and Novick take us from the corridors of power in Washington, Hanoi, and Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) to rice paddies and jungles and POW prisons. Driven by Burns’ characteristic devices–curated music, limited but effective interviews, and powerful still and moving imagery–The Vietnam War may have an even larger cultural impact than his landmark Civil War project of 1990. (Colin Powell, then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, gave President George H. W. Bush videotapes of that documentary to watch in the run-up to the Gulf War. In his audiotape diary, the President recounted how the moving accounts of the travails of ordinary soldiers helped reinforce his determination to avoid a long land war in the Middle East.) I’ve always thought about what it would have been like for veterans of the cataclysm of 1861–65 to experience Burns’ treatment of their war. With the new documentary, we don’t have to wonder, for the warriors of the Vietnam era, many now in their 70s, will relive those momentous, disorienting days.

Vietnam and Watergate were decisive events in the erosion of trust in the government with which we still live, and both Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon admitted in private what they would not say in public. “The great trouble I’m under–a man can fight if he can see daylight down the road somewhere,” Johnson told Senator Richard Russell in a tape-recorded conversation in March 1965, early in the journey. “But there ain’t no daylight in Vietnam.” During the ’68 campaign, Nixon was more honest with his aides than with voters–and soldiers: “I’ve concluded that there’s no way to win the war,” Nixon said. “But we can’t say that, of course. In fact, we have to seem to say the opposite, just to keep some degree of bargaining leverage.” The war would last another seven years.

Jere Meacham on patrol in Vietnam with other members of the U.S. Army’s Fourth Infantry Division. He sent the images to his son in 1999. Courtesy Jon Meacham

Hal Kushner, a medic, held in captivity for five years by the Viet Cong, is among the film’s memorably affecting figures. His voice catching, tears coming, Kushner describes his 1973 release: “There was an Air Force brigadier general in Class A uniform. He looked magnificent. I looked at him, and he had breadth; he had a thickness that we didn’t have. He had on a garrison cap, and his hair was plump and moist, and our hair was like straw. It was dry, and we were skinny. And I went out and I saluted him, which was a courtesy that had been denied us for so many years. And he saluted me, and I shook hands with him, and he hugged me–he actually hugged me. And he said, ‘Welcome home, Major. We’re glad to see you, Doctor.’ The tears were streaming down his cheeks.”

In the film, Kushner tells this story with Ray Charles’ “America the Beautiful” playing softly in the background. To write about it risks making the presentation of Kushner’s release seem hokey, but it is not. Far from it. To me, the Kushner sequence is perhaps the most powerful moment in the entire series, not least because of the newly freed POW’s sense of dimension and size. The magnificence of the officer who greeted him, the “breadth” and “thickness” and the “plump” and “moist” hair: it’s as though the scraggly and sapped Kushner saw the general as the embodiment of the old America, invincible America, victorious America–an America that didn’t really exist anymore, or at least not in Southeast Asia.

Picture taken in the Central Highlands in South Vietnam 1968-69. Courtesy Jon Meacham

One cold winter morning after Christmas 1984–I was 15, the same age my son is now–my father and I took a trip to Washington. Like a lot of other veterans, he had been skeptical of the plans for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, thinking the unusual design in a gently sloping hill in the shadow of the monuments to Lincoln and Washington suggested a lack of respect. Seeing it changed his mind. He said nothing as we walked along the wall of the dead. Coming to the years of his service, he stopped, searching for a familiar name. He found it, and it was within reach. He ran a finger over the letters, turned, stepped back, and we moved on.

In his letter to me with the photographs of Vietnam 15 years later, my father was relatively terse about his thoughts in-country. “I wanted,” he wrote, “to get back to life.” My father is dead now, but for the warriors who remain among us, Ken Burns has at last charted a path back toward life, and toward home.

Meacham is the author of Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush.

This appeared in the September 25, 2017, issue of TIME.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 16, 2025

The Freedom Bird

Anne Zimbler is a former flight attendant of World Airways. She contacted me after reading an earlier post on my website about some of us not remembering our flight back to the World, and thought this note could help us remember.

This is her email message:

John, although not a day passes, that something I see or hear does not bring back memories of my time with World Airways and the Military Charters we flew, reading posts on your website gave me gifts I had not appreciated in some years.

I hope the information I provide below helps some of your readers with what they may have forgotten. I would like you to read it before publishing to see if you think my words will be helpful or not. If not, please do not feel any obligation to include it on your website.

Thank you for your help on this, and thank you for your service in Vietnam. There are not enough people who remember what happened during those years, nor were there enough people who showed or spoke their gratitude after our Vietnam Veterans returned home. I am sorry for that.

I have been reading some of the posts on the article “Freedom Bird:” Why Can’t I Remember the Ride Home?” I was surprised to learn that many Vietnam Vets have neither memories of their flights home, nor the routes they took to make it back to the “World.”

In my early to mid-twenties, I flew for World Airways to and from Vietnam, and on R&R Flights from Vietnam to Thailand, Japan, the Philippines, Australia, Hong Kong, and Hawaii.

For those of you who have lost track of the trajectory of your homeward-bound flights from Vietnam, the information below may be helpful. These routes were flown by World Airways, so if you flew on other airlines over and back, the routes might have varied a bit.

We would have picked you up for your first leg home in Saigon, Bien Hoa, or Cam Ranh Bay if you were Army or Air Force, or Da Nang if you were a Marine. Many of you boarded our planes in fatigues, as you had just landed on military transports that brought you to one of the major air bases mentioned above.

Your first leg with us took you to Yokota AFB, Japan (just outside Tokyo) for a fuel stop and crew change. Your next leg went “North Pac” to the West Coast of the United States. Most of these flights were non-stop; however, occasionally we could not catch the Jet Stream and had to stop in Anchorage, Alaska, making your trip to the West Coast a little longer.

If we were able to catch the Jet Stream, you would go non-stop to either Travis AFB, just outside San Francisco, Oakland International Airport, or McChord AFB, just outside Seattle. From Travis or Oakland International, you went to either Oakland Army Depot or San Francisco International Airport for your flight home. This, of course, depended on your military orders. Again, based on your military orders, from McChord, you went to either Fort Lewis or SEA TAC International Airport for your flight home to your loved ones.

Either way, your time with World Airways ended somewhere on the West Coast of the United States, and you flew on a commercial flight to your home and family.

What many of you may not know is how much your cabin crews cared about you. It would have been unprofessional for us to have shown you the tears we held until you deplaned in Vietnam. We worried about you and said silent prayers for your safe return. We cherished our time with you and tried to make you as comfortable as possible. Most flight attendants, from the many airlines that flew military charters during that era, would tell you we truly treasured our military passengers.

Here is a quote from Willow Carter, 74, taken from Conde Nast Traveller website:

On the military charters, practically all the men were on their way to Vietnam. For a while, I had terrible anxiety, thinking that I was taking these young men to die. Then I realized: if it wasn’t me, it would be someone else, so I was determined to make their trip as comfortable as possible.

In closing, and on behalf of the cabin crews who brought you home, we thank you for your bravery, dignity, and service. We will always remember your faces and the many conversations some of us had with you on those long trips over the Pacific. In our minds, you remain young men who served your country and graced our lives for a moment in time, many years ago, during a difficult period in our shared history.

You are still, and will always be, Our Heroes.

Anne,

World Airways Flight Attendant, 1970 to 1973

If you want to read more about the FREEDOM BIRD FLIGHTS, check out these additional posts on my website:

Vietnam “Freedom Bird” – Why can’t I remember the ride?

Southern Californian Remembers Life as a Pan Am Stewardess in Vietnam

MY LAST ’NAM FLIGHT

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update is posted on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 9, 2025

Technicians Couldn’t Restart a Downed Helicopter, Then the General Called a Forgotten Combat Veteran

Truth or fiction? Either way, this is one hell of a story that shows practical experience is sometimes better than being school smart.

When a team of the military’s brightest technicians can’t restart a legendary UH-1 Huey helicopter, they openly mock the one man called in to help: an elderly veteran in a faded jacket. They see a relic from a bygone era, a man hopelessly out of touch with their world of digital diagnostics and complex schematics. His quiet talk of the machine having a “soul” is met with condescending laughter and outright dismissal. What begins as a simple technical failure becomes a powerful public reckoning, proving that the deepest knowledge isn’t always found on a screen, and that true legends command a respect that technology can never replace.

This short video is worth watching…

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update is posted on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

August 2, 2025

America…Vietnam…Italy

Imagine you are touring Italy and a stranger joins you at your table during lunch. After some small talk, he wants to share his Vietnam War experience with you. He has to tell his story, and you listen intently for the next two hours. Later, his memories will need to be paid forward.

How the traces of the Vietnam War never end.

By David Gerstel.

Two of the men in this story I never met. The third was a stranger who introduced himself in Sarnano. His name was Joe. We had drinks at an outside bar under a large umbrella in the medieval village, which I was

visiting as part of a slow food tour and introduction to Le Marche. We began with bruschetta, focaccia, and triangles of pecorino cheese with honey that ran to the edges of a black Japanese slate. I took notes on thin napkins. Our conversation lasted more than two hours, and he was sitting silently when I left, continuing to drink an excellent Rosso Piceno wine.

We discussed Sarnano’s history and character. I thought he was moving in the direction of an invitation to dinner, which I was expected to pay for. After the second glass of wine, he changed the conversation to the story of his life. Joe said, concentrating on the table, “The journalist Mark Jury died at the end of August of this year. I did not know him or The Vietnam Photo Book, but had seen his photographs in magazines long ago. “Vietnam”, Jury is quoted as saying in the NY Times obituary by Clay Risen, “caught up with me.” Our lives were touched by the news of his death and the reference to the passing in 2016 of Michael Herr, the author of Dispatches.

Joe: “I was at sea, east of Suez on an American Export Line vessel, the steamship Exemplar, in the summer of 1965. It was the India run, and we spent more time in Calcutta than New York, berthed at the Kidderpore Locks for so long that some crew had apartments and wives. This was my second or third India voyage after a year on passenger ships and time in the Med. My parents received a letter from the local Selective Service office. It would have to wait until the voyage ended. At 23 years old, I was a merchant marine officer on voyages to countries that few Americans cared about.

“The India ship paid off in New York on a Thursday, cash in our pockets, a great deal of cash. By law, we were paid in US dollars at the end of a voyage. Seamen are wards of the government, along with Indians. The government does not think much of either group.

“The letter was short. I could sail on ships to Vietnam or be drafted into the army. They had no reference. Door number 1, door number 2. I chose the first because the pay was better.

“The subway brought me to the operations manager’s office of the company in Lower Manhattan, from which you could see Miss Liberty. I waved to her every time we headed up the Hudson River to the company’s piers in Hoboken. Francis Xavier O’Bryn glanced at the letter with the government stamp and the signature of a clerk who decided the fate of men and boys he would never meet beyond their zip codes. He said there was a ship to Vietnam on Saturday. Two days between voyages. No time for a Broadway play. I went to the doctor to be vaccinated.

“We loaded at Hoboken and went coastwise to Philadelphia, Savannah, New Orleans, Beaumont, Texas for ordnance, tanks and bulldozers, beer and peaches, air conditioners and china dishware, condoms

and medical supplies, coffins; the necessities and accessories of war. Our voyage was going to take 6 to 7 months. I don’t remember if we went through the Panama Canal or around the Cape of Good Hope. It was a long way to the sound of cannons.

Michael Herr, author of Dispatches PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL HERR

“Ships were in high demand and short supply that year. Every available freighter was chartered for Vietnam. The companies were going to make a fortune. Any mate, engineer, or seaman who could walk found a ship. Some had sailed in the Atlantic convoys to England and Russia from 1941 to the surrender of Germany. All the deck officers on my ship had unlimited master’s licenses and could have been in command. The crew was experienced with a few like me, young. Vietnam was a birthday cake with candles and gift wrapping. The North Vietnamese had no submarines and no aircraft to sink merchant ships. We were all going to make it through.

“Some Captains never drank, others never stopped. I sailed with one who was falling down drunk for six months without a day off, and every officer took the ship away at least once. Johnny Walker Red Label scotch was a dollar and a half, duty-free. In Saigon, the Captain closed the ventilators and ports to his cabin for fear of VietCong hand grenades. Never mind that the temperature reached 120 F and there was no air conditioning. We laughed. In that moment, we loved the war.”

Mark Jury: According to his biography, he joined the army to become a combat photographer. He had no restrictions and went where he wanted, from the Continental Palace in Saigon to triple canopy jungle and rice fields, hot landing zones, search and destroy missions, and the Brown Water Navy. He took great and terrible photos, saw combat, and too many bodies. He ran towards the sound of gunfire. It took ten years for him to feel the effects of Vietnam. Then he began to drink and broke down.

Mark Jury – His stark photographs captured the Vietnam experience

Michael Herr: Late in 1967, according to the New York Times, he persuaded the editor of Esquire, Harold Hayes, to send him to Vietnam. It was shortly before Khe Sanh, one of the war’s bloodiest battles, and the Tet Offensive, a North Vietnamese campaign against targets in the South. Writing for a monthly magazine, Herr was an oddity in the press corps; one soldier asked if he would be reporting about what they were wearing, and the American commander, General Westmoreland, wondered if his assignment was to produce articles that were “humorous.” Yet he struggled. “The problem with Vietnam is that if your body came back, your mind came back too. Within 18 months of coming back, I was on the edge of a major breakdown. It hit in 1971, and it was very serious. Real despair for three or four years; deep paralysis. I split up with my wife for a year. I didn’t see anybody because I didn’t want anybody to see me.” It was writing Dispatches that brought it on, the memories and people asking about Vietnam. What he had seen went into the book, and there was nothing left. The first question is always: How many did you kill?

Joe: “I stayed in Vietnam for three years, back and forth across oceans. For the most part, it was easy, waiting to be discharged, watching the sunrise, and doing the job. That left time to lend a hand and fly supplies to fire support bases on C-130s from Da Nang, join the Koreans on sweeps through rubber plantations, be ambushed on the streets of Saigon and Cholon, or be killed in a cargo hold 50 feet below the freighter’s steel deck.

“Once or twice, I went out with American troops, pretending to be a warrior. We ran the river to Saigon under machine gun fire. None of it seemed real and I wanted more, a speaking role in the movie. I was a participant in the great adventure, excited and exhausted. I carried a union card with benefits.

“Vietnam was a roulette game. The bowl was dark and the hooded croupier dressed in black. All the segments on the spinning wheel were shadowed. The gamblers stood around, played with their cigarettes, gum, and weapons, and listened to rock and roll. You were not surprised when the ball stopped. It was continuous play, and your bet came up before the sun. No one wanted to win but you had to play. The newspapers at home had casualty lists bordered by thick black lines, but papers were not delivered to the casino. The notices were never read. Death was an empty space on the field.”

Jury and Herr wrote other books, but their lives were built in Vietnam. The tragedy, the legacy, even the laughter, was Vietnam.

Joe: “My war ended and other mates replaced me. I was back on the India run, done what the government said was my duty in the South China Sea, and carried the same germs of the disease that afflicted Jury and Herr. But I was unsure if it was Vietnam or dysentery from bad shrimp in Bombay at the Chinese restaurant near the Gateway to India that caused the pain. I worked the ship.”

In Vietnam, you learned caution and courage, deeply buried the dread that settled like fog in low valleys. Yesterday was gone and you forgot the day ahead. Some men wrote home every day, others never. They thought luck was with them. Until it wasn’t. Personal items were put into a cardboard box with a tag; socks and sweets were divided among the other men.

You did not realize when you came home that Vietnam was a finishing school for the remainder of your life. You weren’t smart enough for that. It made you different, tougher, more afraid and less. You pushed boundaries because Vietnam had none. You saw what men could do.

Joe: “Years later I left the sea and went far from the watery part of the world, work on the land carrying freight. Vietnam came with me. The infection continued to grow, invisible to an X-ray. Eventually, it would show a darkness on the negative held to light, but the terror on the edges was missed.”

Joe kept speaking, unwilling, unable to stop. I asked him why he was telling me all this. His answer was, “Because I will not see you again. Maybe the drinks and I needed to talk after I saw Jury’s obituary and read about Herr because I am tired and you are here, and there is no one else. Bad luck for you. And you are paying.” I was the audience and stenographer.

He said a few participants in Vietnam were fortunate and able to speak, Jury through his camera, Herr on a typewriter. Others had someone to listen to or say get over it, deal with it, and move on. Joe’s war was replayed in his car, at the stream where he fished, at breakfast in a diner with bacon and eggs, a baseball game on a windy day, in bed. There was remission from time to time.

Awareness came slowly; he changed jobs and cities, and abandoned friends. His wife left with the children, saying his war was behind her. Eventually, he bottomed out, gave up the companionship of men, and drifted away and downward. He had his devils, and together they visited his youth in the eastern seas, needing no guide or compass. The difficulty was returning.

He had to find a simpler world and so came to Italy, recalled from his days at sea, retreated to a village built on a rock one thousand years ago, and met a tourist in the historic center.

I had a room at the Hotel Terme off the Piazza della Libertà, which has tall trees and many benches, the statue of a priest paid for by a doctor in Toronto, and a bathing pool for birds. It is a peaceful spot. There is a memorial carved from Carrara granite that names the Sarnano men dead in the Nazi war. From the restaurant in the hotel, I ordered dinner, asking that it be brought to my room with a liter of wine.

My travels continued and I came back to Sarnano after two months. I had seen Ascoli Piceno, Urbino, the wonderful bronze horses in Pergola, and many other towns and villages. Asking for Joe, the bar owner said he had died in a fall, an accident late at night on the steep turning steps to the Piazza Alta

and the Chiesa di Santa Maria. I knew it was not accidental. He died of wounds.

It was a year before I understood what Joe had spoken about under a setting sun beneath the Sibillini mountains. I make an effort now to remember him, as well as Jury, Herr, and the others who lived that time. Joe’s life and memory have been paid forward, a good thing. I wish it could be more.

A quote on the internet, “Not everyone who lost his life in Vietnam died there, not everyone who returned from Vietnam ever left there.” Amen to that.

For Roni and Florence

David Gerstel is an American expat who has lived for many years in Sarnano, a small town nestled among the hills of the Province of Macerata, in the Italian region of Marche. It’s the middle of nowhere, but the center of everything.

dgerstel@securenet.net

This article originally appeared in THE AMERICAN, the transatlantic magazine July – August 2025/ Here’s the direct link:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update is posted on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 26, 2025

Why is it called The Wall That Heals?

This is an email I recently received from the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund:

It’s a question asked every year, and the answer is often difficult to put into words. It is a transformative experience, and when you witness our three-quarter scale traveling replica and Education Center arrive in a community, the answer becomes quite clear.

Inside the 53-foot trailer that becomes the Education Center is our three-quarter scale Wall replica, which carries the more than 58,000 names of service members who died or were missing in action during the Vietnam War. The 58,000 names are inscribed on 140 panels that span 375 feet, and in that space, something miraculous happens: it becomes a place of healing.

The Wall That Heals brings the power and purpose of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial to our hometowns. Each site becomes sacred ground, and while we are there, it is always open, always welcoming, and always healing. Here, veterans find a comforting space to remember, honor, and grieve. Families get a chance to visit their loved ones. Communities and younger generations can witness the service and sacrifice of their hometown heroes.

The transformation, from open ground to hallowed ground, is made possible by you. Your support keeps this symbol of honor, remembrance, and healing on the road, reaching those who need it most.

We hope you can visit us on the road and experience the impact of your support. Here is the schedule for the rest of 2025:

CITY HOST OPENING CLOSING

St. Louis County, MOThe Wall That Heals – St. Louis County, MO7/24/257/27/25Buckner, MOThe Wall That Heals – Buckner, MO7/31/258/3/25Nevada, IAMain Street Nevada8/7/258/10/25Emporia, KSThe Wall That Heals Emporia8/14/258/17/25Spokane, WAWA State Fallen Heroes Project8/28/258/31/25Ellensburg, WAKittitas County Rotaries9/4/259/7/25Port Townsend, WAAmerican Legion Post #26 & Hadlock VFW Post 74989/11/259/14/25Independence, ORVeterans & Independence OR The Wall That Heals 20259/18/259/21/25Orange, CAThe Wall That Heals – Orange 202510/2/2510/5/25Clovis, CAThe Wall That Heals Central Valley10/9/2510/12/25American Canyon, CACity of American Canyon10/16/2510/19/25Wylie, TXThe Wall That Heals – Wylie Host Committee10/30/2511/2/25Athens, ALAthens State University11/6/2511/9/25Crystal Springs, MSMS Patriots and The City of Crystal Springs11/13/2511/16/25To view additional posts about THE WALL, go to the top right of this page, click on the magnifying glass, and type THE WALL. Several articles will appear in a scroll-down menu. After reading a post, simply click on the back arrow at the top left of this page to return to the list.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update is posted on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 18, 2025

One Ride with Yankee Papa 13

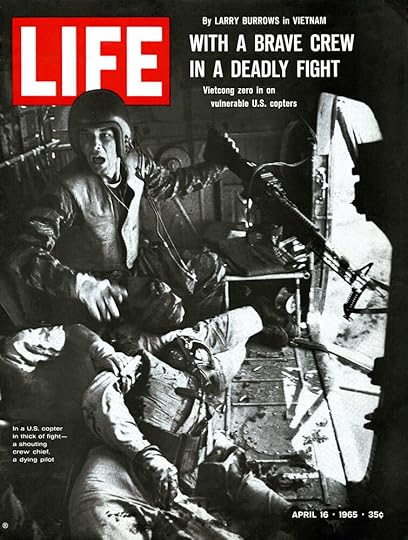

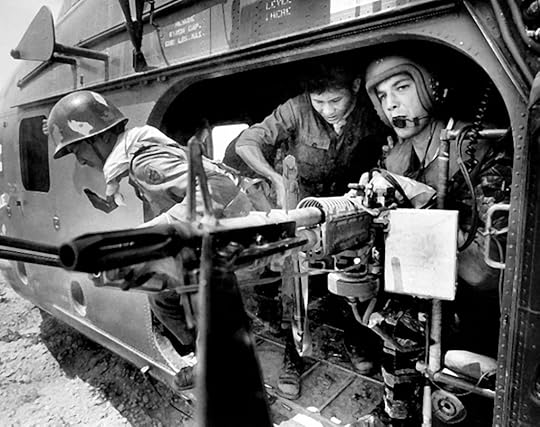

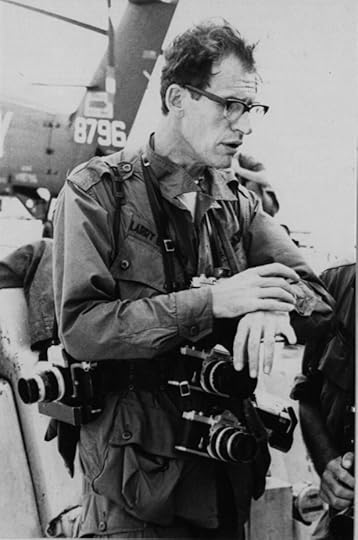

The photo is part of a photo essay by photographer Larry Burrows. The photos and the story were published under the title “One Ride with Yankee Papa 13”. It was published in Life Magazine in April 1965.

Written By: Ben CosgroveIn the spring of 1965, within weeks of 3,500 American Marines arriving in Vietnam, a 39-year-old Briton named Larry Burrows began work on a feature for LIFE magazine, chronicling the day-to-day experience of U.S. troops on the ground and in the air amid the rapidly widening war. The photographs in this gallery focus on a calamitous March 31, 1965, helicopter mission; Burrows’ “report from Da Nang,” featuring his pictures and his personal account of the harrowing operation, was published two weeks later as a now-famous cover story in the April 16, 1965, issue of LIFE.

Over the decades, of course, LIFE published dozens of photo essays by some of the 20th century’s greatest photographers. Very few of those essays, however, managed to combine raw intensity and technical brilliance to such powerful effect as “One Ride With Yankee Papa 13,” universally regarded as one of the greatest photographic documents to emerge from the war in Vietnam.

Here, LIFE.com presents Burrows’ seminal photo essay in its entirety: all of the photos that appeared in LIFE are here. (Note: In a picture from the article, Burrows mounts a camera to a special rig attached to an M-60 machine gun in helicopter YP13 a.k.a., “Yankee Papa 13.” At the end of this gallery, there are three previously unpublished photographs from Burrows’ 1965 assignment.]

Burrows, LIFE informed its readers, “had been covering the war in Vietnam since 1962 and had flown on scores of helicopter combat missions. On this day, he would be riding in [21-year-old crew chief James] Farley’s machine, and both were wondering whether the mission would be a no-contact milk run or whether, as had been increasingly the case in recent weeks, the Vietcong would be ready and waiting with .30-caliber machine guns. In a very few minutes, Farley and Burrows had their answer.”

The following paragraphs, lifted directly from LIFE, illustrate the vivid, visceral writing that accompanied Burrows’ astonishing images, including Burrows’ own words, transcribed from an audio recording made shortly after the 1965 mission:

“The Vietcong dug in along the tree line, were just waiting for us to come into the landing zone,” Burrows reported. “We were all like sitting ducks and their raking crossfire was murderous. Over the intercom system one pilot radioed Colonel Ewers, who was in the lead ship: ‘Colonel! We’re being hit.’ Back came the reply: ‘We’re all being hit. If your plane is flyable, press on.’

“We did,” Burrows continued, “hurrying back to a pickup point for another load of troops. On our next approach to the landing zone, our pilot, Capt. Peter Vogel, spotted Yankee Papa 3 down on the ground. Its engine was still on and the rotors turning, but the ship was obviously in trouble. “Why don’t they lift off?’ Vogel muttered over the intercom. Then he set down our ship nearby to see what the trouble was.

“Twenty-year-old gunner, Pfc. Wayne Hoilien was pouring machine-gun fire at a second V.C. gun position at the tree line to our left. Bullet holes had ripped both left and right of his seat. The plexiglass had been shot out of the cockpit and one V.C. bullet had nicked our pilot’s neck. Our radio and instruments were out of commission. We climbed and climbed fast the hell out of there. Hoilien was still firing gunbursts at the tree line.”

Not until YP13 pulled away and out of range of enemy fire were Farley and Hoilien able to leave their guns and give medical attention to the two wounded men from YP3. The co-pilot, 1st Lt. James Magel, was in bad shape. When Farley and Hoilien eased off his flak vest, they exposed a major wound just below his armpit. “Magel’s face registered pain,” Burrows reported, “and his lips moved slightly. But if he said anything, it was drowned out by the noise of the copter. He looked pale, and I wondered how long he could hold on. Farley began bandaging Magel’s wound. The wind from the doorway kept whipping the bandages across his face. Then blood started to come from his nose and mouth, and a glazed look came into his eyes. Farley tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but Magel was dead. Nobody said a word.”

In his searing, deeply sympathetic portrait of young men fighting for their lives at the very moment America is ramping up its involvement in Southeast Asia, Larry Burrows’ work anticipates the scope and the dire, lethal arc of the entire war in Vietnam.

Six years after “Yankee Papa 13” ran in LIFE, Burrows was killed, along with three other journalists, Henri Huet, Kent Potter, and Keisaburo Shimamoto, when a helicopter in which they were flying was shot down over Laos in February 1971. He was 44 years old.

Helicopter gunner James C Farley shouts to the rest of the crew as the fatally wounded copilot lies beside him. Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13. Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The fatally wounded pilot in the photo was not the pilot of the helicopter Farley was assigned to. He’s actually the copilot of another copter, “Yankee Papa 3″. When Farley’s helicopter spotted a downed helicopter and landed near it, Farley and the photographer ran over to the downed helicopter and found the wounded copilot. The photo was taken inside the downed helicopter. Farley and the copilot are the ones in the photo above. Farley also examined the pilot, who was bleeding and not moving. He came to the conclusion that he was dead. In fact, he was alive. The copilot and another marine from YP3 were taken back to Farley’s copter. Two more marines from YP3 made it to Farley’s copter on their own. Later on, another copter landed near YP3 and rescued the wounded pilot, who survived.

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Vietnam War, LIFE Magazine, Yankee Papa 13 Larry Burrows Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Henry Frank Leslie Burrows (29 May 1926 – 10 February 1971), known as Larry Burrows, was an English photojournalist. He spent 9 years covering the Vietnam War.

Here is the link to the original Life Magazine article:

Sudden Death in Vietnam: ‘One Ride With Yankee Papa 13’

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 12, 2025

Distentio

I recently received this Vietnam War poem from my Facebook friend and author, William Paul Beau Gruendler. I thought it was quite good and wanted to share it with you.

Distentio is a Latin term that translates to “a stretching” or “a distention.” It refers to the act of being stretched or expanded and can also indicate a state of being stretched apart. (Apologies to HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW)

The shades of night were falling fast

As through an Old Man’s hourglass

passed

A youth, who penned,

in marker, black,

His helmet with the

Latin crack:

“Distentio”!

His brow indifferent

beneath,

His bayonet still

in its

sheath.

He’d had some

college, so he sung

In accents of that

unknown tongue,

“Distentio!”

Downhill the shrapnel

split the air.

Artillery? What did he

care?

Above, the spectral

gunships roared,

But from his lips

escaped a bored,

“Distentio!”

Intel had cut the

troops no slack.

“Beware the human

wave attack!”

Thus were the

peasants poised to kill.

A voice replied, far up

the hill:

“Distentio!”

“We’re calling jets,”

the sargeant said;

“So stack those

sandbags overhead,

And dig in deep;

prepare to fight!”

Now hear a voice

o’ercome with fright:

“Distentio!”

“Dear John,” the

girlfriend’s letter said,

“For all I know, you

might be dead.”

A tear stood in his

bright blue eye,

He’d answered her but

with a sigh:

“Distentio!”

At break of day, from

heavenward

As MEDEVAC came

chopping toward

The ruins of that

landing zone

A voice cried, though

it were a groan:

“Distentio!”

A soldier, by cadaver

hound,

Half-buried in the clay

was found,

Still perched upon his

quiet head

That helmet scrawled

with black and red:

“Distentio!”

This morning, under

cold gray skies,

Alone, an old man

tries to rise.

He feels he hears a cry from

far,

As from the clouds

the Muse of War:

“Distentio!”

*****

If you are interested in helmet artwork during the Vietnam War, then follow the link to check out that post on my website: https://cherrieswriter.com/2018/08/27/helmet-cover-graffiti/

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update appears on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

July 5, 2025

U. S. Casualties in the Vietnam War by Branch of Service

Here’s another breakdown of U.S. casualties sustained during the Vietnam War. I have also added links to other posts on this website, which contain additional information at the end of this article.

The following chart was found on the following website: National Archives and Records Administration / Defense Casualty Analysis System

Casualty TotalArmyAir ForceSpace ForceMarines NavyKilled in Action40,93427,0471,080011,5011,306Died of Wounds5,2993,6105101,486152Missing in Action – Declared Dead1,085261589098137Captured – Declared Dead116452501036TOTAL HOSTILE DEATHS47,43430,9631,745013,0951,631Missing – Presumed Dead1231180032Other Deaths10,6637,14384101,746933TOTAL NON-HOSTILE DEATHS10,7867,26184101,749935TOTAL IN-THEATER DEATHS58,22038,2242,586014,8442,566Killed in Action – No Remains575173206010294Missing in Action – Declared Dead – No Remains69120133907477Captured – Declared Dead – No Remains523270310Non-hostile Missing – Presumed Dead – No Remains91860032Non-hostile Other Deaths – No Remains3326930037196TOTAL – NO REMAINS1,7415615820219379WOUNDED – NOT MORTAL153,30396,802931051,3924,178NUMBER SERVING WORLDWIDE8,744,0004,368,0001,740,0000794,0001,842,000NUMBER SERVING SOUTHEAST ASIA3,403,0002,276,000385,0000513,000229,000NUMBER SERVING SOUTH VIETNAM2,594,0001,736,000293,0000391,000174,000The following information is from www.lzsalley.com (101st Airborne)

9,087,000 military personnel served on active duty during the Vietnam Era (28 February 1961 – 7 May 1975)

8,744,000 personnel were on active duty (worldwide) during the war (5 August 1964-28 March 1973)

3,403,100 (including 514,300 offshore) personnel served in the SE Asia Theater (Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, flight crews based in Thailand, and sailors in adjacent South China Sea waters).

2,594,000 personnel served within the borders of South Vietnam ( I January 1965 – 28 March 1973)

Another 50,000 men served in Vietnam between 1960 and 1964

Of the 2.6 million, between 1 and 1.6 million (40-60%) either fought in combat, provided close combat support, or were at least fairly regularly exposed to enemy attack.

7,484 women served in Vietnam, of whom 6,250 or 83.5% were nurses.

The peak troop strength in Vietnam was 543,482 on 30 April 1969.

1,736,000 were US Army

391,000 were US Marines

293,000 were US Airmen

174,000 were US Sailors (this figure includes the US Coast Guard)

Casualties:

Hostile deaths: 47,359

Non-hostile deaths: 10,797

Total: 58,156 (including men formerly classified as MIA and Mayaguez casualties.

Highest state death rate: West Virginia–84.1. (The national average death rate for males in 1970 was 58.9 per 100,000).

WIA: 303,704 – 153,329 required hospitalization, 50,375 who did not.

Severely disabled: 75,000, 23,214 were classified 100% disabled. 5,283 lost limbs, 1,081 sustained multiple amputations.

Amputation or crippling wounds to the lower extremities were 300% higher than n WWII and 70% higher than in Korea. Multiple amputations occurred at the rate of 18.4% compared to 5.7% in WWII.

MIA: 2,338

POW: 766, of whom 114 died in captivity.

Draftees vs. volunteers:

25% (648,500) of the total forces in-country were draftees. (66% of U.S. armed forces members were drafted during WWII)

Draftees accounted for 30.4% (17,725) of combat deaths in Vietnam.

Reservists KIA: 5,977

National Guard: 6,140 served; 101 died.

Ethnic background:

88.4% of the men who actually served in Vietnam were Caucasian, 10.6% (275,000) were black, 1.0% belonged to other races.

86.3% of the men who died in Vietnam were Caucasian (including Hispanics)

12.5% (7,241) were black.

1.2% belonged to other races

170,000 Hispanics served in Vietnam, 3,070 (5.2%) of whom died there.

34% of blacks who enlisted volunteered for the combat arms.

Socioeconomic status:

76% of the men sent to Vietnam were from lower middle/working class backgrounds

75% had family incomes above the poverty level

23% had fathers with professional, managerial, or technical occupations.

79% of the men who served in ‘Nam had a high school education or better.

63% of Korean vets had completed high school upon separation from the service)

Winning & Losing:

82% of veterans who saw heavy combat strongly believe the war was lost because of a lack of political will.

Nearly 75% of the general public (in 1993) agreed with that.

Age & Honorable Service:

The average age of the G.I. in ‘Nam was 19 (26 for WWII)

97% of Vietnam-era vets were honorably discharged.

Pride in Service:

91% of veterans of actual combat and 90% of those who saw heavy combat are proud to have served their country.

66% of Viet vets say they would serve again, if called upon.

87% of the public now holds Viet vets in high esteem.

Helicopter crew deaths accounted for 10% of ALL Vietnam deaths. Helicopter losses during Lam Son 719 (a mere two months) accounted for 10% of all helicopter losses from 1961-1975.

Other posts on this website cite casualties by age, race, country, category, year, state, enlisted vs. officer, married vs. single, and civilian contractors.

Fatal Casualties of the Vietnam War

Vietnam War Casualties #2

Casualty Lists of the Vietnam War

#####

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!