John Podlaski's Blog, page 13

July 1, 2023

HOW A SEARCH FOR MISSING COMRADES IN VIETNAM LED TWO INFANTRY COMPANIES STRAIGHT INTO AN ENEMY INFERNO

The rugged scenery of the Central Highlands became the scene of numerous bloody battles during the war.

A LRRP team was missing. Two companies are out searching for their missing brothers in the highlands of Vietnam and walk right into a trap set by the NVA. The odds are overwhelming and one platoon is overrun. The number of dead and wounded continue to climb. Do any survive?

Soldiers of the U.S. Army 4th Infantry Division move through a clearing in the Central Highlands of Vietnam near the Cambodian border in 1967, leaving behind the remains of a fallen comrade who lies where he fell, covered by a poncho. (AP Photo/Johner)

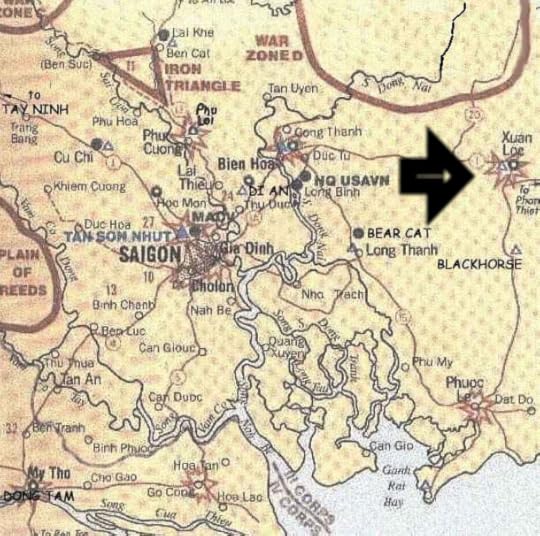

Assuming command of the 4th Infantry Division in early January 1967, Maj. Gen. William R. Peers understood that his new assignment in the Central Highlands was something of an economy-of-force operation. The 4th was to monitor the Cambodian border, sound the alarm whenever the North Vietnamese Army returned in strength, and respond accordingly.

Lt. Gen. Stanley Larsen, then the commander of I Field Forces responsible for the Highlands, recommended using spoiling operations to keep the North Vietnamese off balance. “If you ever let him get set,” Larsen had cautioned Peers’ predecessor, Maj. Gen. Arthur Collins Jr., “you’re going to pay hell getting him out.”

A Viet Cong detachment rushes into battle in January 1967. North Vietnam employed both conventional and irregular forces against American troops. The Central Highlands was a hotbed of enemy activity. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

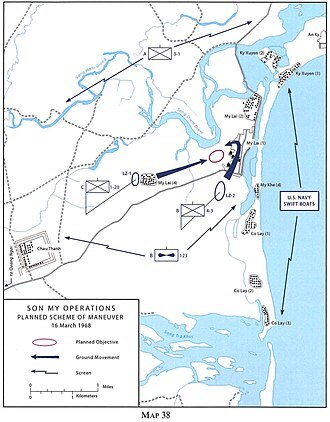

A Viet Cong detachment rushes into battle in January 1967. North Vietnam employed both conventional and irregular forces against American troops. The Central Highlands was a hotbed of enemy activity. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)Collins initiated Operations Paul Revere IV and Paul Revere V (later renamed Sam Houston), the latter just two days before he turned the division over to Peers, as part of the 4th’s ongoing efforts to observe and counter enemy infiltration in the Highlands. Collins warned Peers that the North Vietnamese were constructing a “fortified redoubt” in the Plei Trap Valley—a rugged stretch of jungle between the Se San and Nam Sathay Rivers in western Pleiku Province.

At first, Peers found little evidence to support those suspicions. By February, however, aerial sightings, long-range reconnaissance patrols, and communications intelligence had detected signs of enemy activity in the Plei Trap. That activity was likely connected to Gen. Chu Huy Man’s plans for a winter-spring offensive. A veteran of the Viet Minh war against the French and commander of the Communist B3 (Central Highlands) Front, Chu intended to attack west of the Nam Sathay to disrupt Operation Sam Houston and prevent the Americans from destroying his rear areas and supply caches.

Responding initially with B-52 strikes, Peers based Col. James Adamson’s 2nd Brigade between the Plei Trap and Pleiku City and pushed two of its battalions across the Nam Sathay on Feb. 12. Adamson would soon tangle with elements of Col. Nguyen Huu An’s battle-tested 1st NVA Division west of the river, prompting Peers to recall his 1st Brigade from Phu Yen Province on the coast. Commanded by Col. Charles A. Jackson, the 1st assumed responsibility for the area between the two rivers, while Adamson was to continue working west of the Nam Sathay to the Cambodian border.

An M60 machine gun is brought into action against communist forces near the Cambodian border in 1967. The 2nd Platoon used M60s to defend themselves against an enemy blocking force. (AP Photo)

An M60 machine gun is brought into action against communist forces near the Cambodian border in 1967. The 2nd Platoon used M60s to defend themselves against an enemy blocking force. (AP Photo) Men of the 4th Infantry Division clear a landing zone for helicopters amid the dense foliage of the Central Highlands in 1967. (AP Photo)

Men of the 4th Infantry Division clear a landing zone for helicopters amid the dense foliage of the Central Highlands in 1967. (AP Photo)Over the next few weeks, the two brigades made regular contact with North Vietnamese regulars. Smaller skirmishes sometimes developed into much larger fights. While operating east of the Nam Sathay on March 12, the 2nd Battalion, 35th Infantry attacked a bunker complex, but could not eliminate the enemy position despite air and artillery support. The daylong battle cost the battalion 14 killed and 46 wounded. Abandoning the complex that night, the North Vietnamese left behind 51 dead, though another 200 may have been killed in the fighting.

Four days later, the 2nd Brigade shifted to the Plei Doc, a heavily jungled area that abutted the Cambodian border south of the Plei Trap. When the brigade lost radio contact with a long-range reconnaissance patrol (LRRP) team late on March 21, Adamson ordered Lt. Col. Harold Lee’s 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry to retrieve the missing men. Lee, recognizing the urgency of the mission, dispatched two companies the following morning.

Breaking camp early on the 22nd, Company A—led by Capt. William Sands, a hardnosed Citadel graduate—moved west-southwest along a ridgeline, flanked by Company B to the south. Company A had only maneuvered a short distance through the dense vegetation when Sands halted the four-platoon column and instructed his 1st Platoon to move forward and join the 2nd Platoon up front. The 3rd and 4th Platoon were to remain in a column formation behind the two lead platoons.

Slipping out of the company column, the 1st Platoon moved abreast of the 2nd Platoon around 7:30 a.m. “The First Platoon was to the left of us, probably fifty to one hundred yards,” noted Sgt. Ron Snyder, a squad leader in the 2nd Platoon. “We barely got lined out, when the First Platoon was hit.” Snyder hit the ground as the roar of enemy rifle and automatic weapons fire reverberated across the jungle.

Struck in the groin, a young soldier wailed in agony while a torrent of fire sliced through the 1st and 2nd Platoons from hidden positions along the ridgeline in front and to the left of Company A. The two lead platoons, trapped in what appeared to be the kill zone of a large enemy ambush, were being cut to pieces.

“I would say within the first four or five minutes, we had 27 killed and 45 wounded,” recalled medic John “Doc” Bockover. “I heard ‘medic’ and started running like hell to the front. There were NVA all around us.” While Bockover raced to treat the wounded, North Vietnamese troops swept around the pinned-down platoons, most likely in an attempt to outflank and encircle the entire company.

A U.S. Air Force F-100 Super Sabre drops bombs on an enemy position near a rural outpost. Air support played a vital role in saving the lives of the men of Company A as gunships and fighter bombers rained U.S. firepower on the enemy. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

A U.S. Air Force F-100 Super Sabre drops bombs on an enemy position near a rural outpost. Air support played a vital role in saving the lives of the men of Company A as gunships and fighter bombers rained U.S. firepower on the enemy. (Bettmann/Getty Images)Sands, moving with the company command group behind the 2nd Platoon, requested artillery fire and attempted to organize a defensive perimeter. He also radioed Company B on the battalion radio net. “You got to get down here!” he shouted over the radio. “We are taking heavy casualties and don’t know how long we can hold out!”

Sands was adjusting artillery fire when a rocket-propelled grenade slammed into the command group. He was killed instantly. 1st Sgt. David McNerney, a tough career man on his third tour of duty in Vietnam, assumed command of the company and calmly rallied the shaken men.

Lee had spoken to Sands earlier in the battle and had directed Company B, commanded by Capt. Robert Sholly, to move at once to assist Company A. Company B, however, was already en route. Sholly had heard gunfire that morning. When he could not raise Sands over the radio, he immediately placed his four platoons online and headed west-northwest.

The sounds of battle grew louder as Company B made its way through the underbrush, hurried along by Sholly. Suddenly a pair of machine guns raked the 4th Platoon on the left flank of the company line. Pinned down in a bamboo field, the platoon returned fire. They could not silence the enemy machine guns nor the shadowy snipers perched in the trees above them. The North Vietnamese, later identified as a battalion from the 95B NVA Regiment, had positioned a blocking force between the two companies to prevent them from linking up.

North Vietnamese commander Gen. Chu Huy Man is pictured trekking through the jungles of the Central Highlands in this undated photo. Enemy activity in the Plei Trap Valley was likely connected to his plans for a winter-spring offensive. (U.S. Army)

North Vietnamese commander Gen. Chu Huy Man is pictured trekking through the jungles of the Central Highlands in this undated photo. Enemy activity in the Plei Trap Valley was likely connected to his plans for a winter-spring offensive. (U.S. Army) Artillery fire helped shatter the North Vietnamese assault. (AP Photo/Kim Ki Sam)

Artillery fire helped shatter the North Vietnamese assault. (AP Photo/Kim Ki Sam) David McNerney. (U.S. Army)

David McNerney. (U.S. Army)Worried he would not reach Company A in time, Sholly instructed his 2nd Platoon to flank the enemy force from the right. He hoped this would relieve some of the pressure on the 4th Platoon. Forming up quickly, the 2nd Platoon dashed forward and leapt into a dry creek bed approximately five feet wide and four feet deep. The bed provided a measure of cover. However, as the platoon prepared to scramble out of it to continue the assault, the startled troopers were met with a heavy volley of automatic weapons fire from enemy soldiers hidden on the opposite bank.

SP4 Victor Renza, one of two machine gunners in the 2nd Platoon, was setting up his M60 machine gun when a single rifle round whistled past his ear with an audible crack. Renza’s legs suddenly went limp, and he slumped back down into the creek bed without firing a shot. The color had drained from his face, and he could feel his heart thumping loudly. Convinced he had been targeted by an enemy sniper, Renza grabbed the M60 and, together with his assistant gunner, crawled along the bed in search of a new position for the gun.

The 2nd Platoon responded with M16s and M60s and was quickly drawn into a costly shooting match with the enemy blocking force. Stalled on the flanks, Sholly attempted to press ahead with the two platoons in the center of the Company B line, but the North Vietnamese refused to budge. “We could not see out of the brush and bamboo, so we were at a disadvantage,” he explained. “We set up fire in the trees but could not break the tie.” The advance had ground to a halt and the company had taken casualties. Facing the prospect of an even tougher fight, Sholly pulled his command post back and called on supporting arms.

Victor Renza. (Victor Renza)

Victor Renza. (Victor Renza)Meanwhile Company A had been split into two separate perimeters. As the North Vietnamese maneuvered on its flanks, past pockets of pinned-down troopers from the 1st Platoon, they bumped into the 3rd Platoon as it moved forward to link up with the 1st. Firing from the hip, machine gunners from the 3rd and a handful of grunts armed with M16s succeeded in slowing the enemy advance.

Though no longer in any immediate danger of being overrun, Company A needed firepower—particularly close-in artillery fire, to shatter the North Vietnamese assault. McNerney recognized as much. After taking over command of the company from the late Sands, he skillfully adjusted artillery fire in support of the company to within 20 meters of friendly positions.

The storm of incoming artillery shook the surrounding jungle. “I can’t begin to tell you how many rounds landed around or on us,” Pfc. Tom Carty observed. “The artillery came screaming in and then exploded with a deafening roar. Shrapnel was hitting everyone and cutting vegetation like a weed eater. It didn’t seem like the artillery would ever stop.” He added, “Round after round after round of artillery came screaming in, exploding, and sending hot deadly metal in all directions, killing [North Vietnamese] and U.S. soldiers without discrimination.”

Soldiers of the U.S. Army 4th Infantry Division move through a clearing in the Central Highlands of Vietnam near the Cambodian border in 1967, leaving behind the remains of a fallen comrade who lies where he fell, covered by a poncho. (AP Photo/Johner)

Soldiers of the U.S. Army 4th Infantry Division move through a clearing in the Central Highlands of Vietnam near the Cambodian border in 1967, leaving behind the remains of a fallen comrade who lies where he fell, covered by a poncho. (AP Photo/Johner)Gunships and fighter bombers hammered the enemy as well, and before long the sheer weight of American firepower began to ease some of the pressure on the embattled company.

Flying overhead in a UH-1B Huey helicopter, WO1 Don Rawlinson of the 4th Aviation Battalion asked Company A for a visual aid so that he could align his approach. McNerney, aware that Rawlinson’s overloaded bird carried desperately needed supplies, climbed a tall tree under intense enemy fire and tied a bright orange identification panel to the highest branch he could find to mark the company’s location. Rawlinson spotted the panel and hurriedly searched for a landing spot. “My God!” he yelled to his copilot as the chopper cruised in. “Can you believe someone climbed up there in that tree and did that?”

McNerney clambered up the tree although he had been knocked to the ground and injured by an enemy grenade earlier in the morning. Throughout the battle, he offered words of encouragement to the troops, checked in on the wounded, and at one point helped clear a landing zone for helicopters. For his extraordinary leadership and remarkable bravery, McNerney was awarded the Medal of Honor at a ceremony held at the White House in September 1968.

As the battle raged around Company A, the number of dead and wounded continued to increase. Bockover treated a wounded radioman and then moved with a squad leader from the 4th Platoon to aid a recent replacement who was lying against a tree, covered in blood.

Chunks of flesh and bone had been ripped from his face, and he was having difficulty breathing. As Bockover prepared to perform an emergency tracheotomy so that the wounded man could breathe, the soldier gazed up at his squad leader and asked if he had finally earned a Combat Infantryman Badge, a highly coveted decoration signifying that the wearer had participated in ground combat. Heartbreakingly, when his squad leader replied that he had done enough to earn a CIB, the man inhaled one final time and then died.

The personal gear of U.S. soldiers belonging to a company of the 4th Infantry Division lies collected in a landing zone in the Central Highlands in 1967. As in our story, this company was nearly annihilated but was saved by air support and artillery. (AP Photo/Hong)

The personal gear of U.S. soldiers belonging to a company of the 4th Infantry Division lies collected in a landing zone in the Central Highlands in 1967. As in our story, this company was nearly annihilated but was saved by air support and artillery. (AP Photo/Hong) An infantryman is comforted by a fellow soldier after witnessing the deaths of his comrades in the Central Highlands in 1967. (AP Photo)

An infantryman is comforted by a fellow soldier after witnessing the deaths of his comrades in the Central Highlands in 1967. (AP Photo)To the south and east of Company A, Sholly summoned all manner of fire support to destroy or dislodge the enemy force blocking Company B’s advance. Sholly pounded the North Vietnamese with 105mm and 155mm guns, fighter bombers, and several flights of A1-E Skyraiders loaded with napalm. Bolstered by this support, Company B was able to maintain freedom of maneuver and establish a more defensible position.

“Saying the platoons were able to consolidate their positions is a cold and distant description of what really went on,” Sholly acknowledged in his book, Young Soldiers, Amazing Warriors. “Each man was looking for targets, moving and shooting, throwing grenades, trying to look out for his buddies, calling for more ammunition, and hearing that hated call for ‘medic.’”

COMBAT BADGEEstablished on Oct. 27, 1943, the Combat Infantryman Badge or CIB was awarded to any U.S. Army soldier or Special Forces member below the rank of colonel who used his infantry skills in battle. Troops who did not see combat but who met the standards during specialized training could receive the Expert Infantryman Badge.

Combat Infantryman Badge. (Historynet Archives)

Combat Infantryman Badge. (Historynet Archives)The cumulative impact of concentrated American firepower softened up the enemy blocking force. By early afternoon Company B was moving west-northwest again, carrying its dead and wounded. The firing tapered off as the North Vietnamese, battered by air strikes and artillery fire and fought to a standstill by Company A, withdrew from the battlefield.

Companies A and B eventually linked up later that afternoon. Taking command of both companies, Sholly met with McNerney, who informed him that Sands had been killed. Sholly, after lamenting the loss of his friend, advised McNerney that a perimeter large enough to accommodate two companies would have to be completed before nightfall. Company A would take up positions in the center of the perimeter. For the remainder of the day, the exhausted troopers evacuated the dead and wounded and dug fighting positions.

Fought for the most part at close range, the battle in the Plei Doc cost the 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry 27 killed and 48 wounded. Company A suffered the lion’s share of the losses, including 22 dead. The missing LRRP team was never found.

Adamson praised the performance of the battalion without considering the number of North Vietnamese killed in the fighting. “That evening at about 2300, General Peers asked me for an enemy body count—I said I had no idea,” Adamson admitted. “He said Saigon wanted to know. Later I received a call from Swede [Stanley] Larsen by secure radio asking the same question. I was to provide a number. I said ‘150.’ The next day we found about 45 bodies and had the body count previously given withdrawn and ‘45’ reported in its place.”

Officially, the 4th Infantry Division reported 136 enemy killed. Whatever the final number—and it was almost certainly higher than 45, given the North Vietnamese practice of removing their dead from their battlefield—Company A had survived the deadly ordeal. Many credit McNerney. “I know that God saved us,” wrote SP4 Willis Nalls of the 2nd Platoon, “but Top’s bravery was what got us out of that firefight.” While undoubtedly a critical factor, McNerney’s heroism alone would not have been enough to save the company without the courage and determination of the young “grunts” holding the line.

Men at this U.S. base in the Central Highlands near the Cambodian border rely on the protection offered by sandbags, logs, and bunkers for defense. North Vietnamese forces launched constant attacks, including repeated mortar barrages, to harass American troops and gain control over the contested region. (AP Photo)

Men at this U.S. base in the Central Highlands near the Cambodian border rely on the protection offered by sandbags, logs, and bunkers for defense. North Vietnamese forces launched constant attacks, including repeated mortar barrages, to harass American troops and gain control over the contested region. (AP Photo)In May, Companies A and B moved into the remote Ia Tchar Valley in western Pleiku Province. On the morning of May 18, while investigating a well-worn trail near the Cambodian border, a platoon from Company B was ambushed and surrounded by a large enemy force. Company A received orders to reinforce its stricken sister company, even as some of its soldiers privately feared that the battle had all the makings of another March 22, only this time in reverse.

That night Company A stumbled around in the dark for hours searching for the “lost platoon.” Overrun and all but wiped out, the platoon was eventually found the following morning. “Those two days [March 22 and May 18] created a bond and a brotherhood between the two companies that has lasted for over 50 years,” said Renza, one of the “lost platoon” survivors. “When we got to them [Company A] in March, they were so happy to see us. We didn’t know who was coming for us. But when they found me on May 19, after the North Vietnamese had overrun us the day before, I couldn’t believe it was those same guys we’d gone to help in March. I know that they were determined to get to us.”

Warren Wilkins is the author of books and magazine articles about the Vietnam War and is a frequent contributor to Vietnam magazine.

From History dot com. This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of Vietnam magazine.

https://www.historynet.com/central-highlands-search-rescue-vietnam/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 24, 2023

Miracle in the Sky

Here’s a notable story about an F-4E Phantom which tangled with a North Vietnamese MIG-21 during a mission in the skies over North Vietnam. It was truly a miracle!

By David Craighead (Clive 04)

Aircrew: 1Lt Wesley Zimmerman, Aircraft Commander

1Lt David “Bubba” Craighead, Weapons Systems Operator

Aircraft: F-4E, tail # 70-321

Unit: 4thTFS, 366TFW, Takhli, RTAFB, Thailand

Flight Location: Pack 6, North Vietnam

Our mission that day was to fly MigCap Patrol for another group of fighters flying from Ubon, RTAFB, Thailand. They would be releasing chaff over the Hanoi area in order to create a chaff corridor for the main F-4 strike force which would be 20 minutes behind us. Our route would take us north over Laos and then east across North Vietnam and into the Hanoi “Downtown” area. The strike target for this mission was the Gia Lam Air Base Communication Control Buildings which housed the main communication system for the North Vietnamese Air Force. I am sure the North Vietnamese were well aware of the American tradition of fireworks on the 4th of July because they expended as many weapons against our force that day as we had seen previously on a single mission.

Our chaff force consisted of sixteen F-4’s and as we set our eastern course for Hanoi, we were told by Red Crown that the MiGs were getting airborne in preparation for our arrival. From as far as 60 miles west of Hanoi, we began receiving heavy AAA barrages including radar-controlled 85mm & 100mm cannon fire. As we approached the Hanoi area and crossed the Red River into the flatlands, our flight was targeted by the surface-to-air missile crews and we became the subjects of the SAM firings. Many SAMs were fired at or towards our chaff force. At this time, our plane received minor damage to the right-wing aileron. The damage was only to the sheet metal portions of the aileron and we continued inbound with the fighter force, figuring no Master Caution light, then no problem.

We concluded our inbound course and performed a group 180* turn to a west heading in order to exit the area. Shortly thereafter, Clive 03, our element leader, made a radio call for us, Clive 04, to “break right, Migs attacking”. A break turn is a maximum performance turn in order to negate an immediate attack from an adversary aircraft. In our instance, Clive 03 had spotted our airplane being attacked by a couple of MiG-19s with 30mm cannons blazing away at us. In fact, the 30mm rounds did hit the vertical stabilizer area of our plane. The “break” turn was a complete 360* turn with us again heading west on our exit heading. But we were now separated from the balance of the chaff force and easily highlighted by their GCI as a single plane by the enemy radar. We had lost visual contact with Clive 03. Shortly thereafter, a MiG-21 snuck into our six-o’clock position and fired his two heat-seeking Atoll missiles at the tailpipes of our F-4E. The missiles scored a hit on our tail section resulting in heavy damage. We were two 1LTs over the Hanoi area taking a ride in what was now a heavily-crippled F-4E. All gauges, navigation gear, radios, and electronic systems were inoperative. The engines continued to churn but at a reduced capability. The cockpit intercom remained OK and we were both talking pretty fast!!

Wes and I had flown together as a team for quite a while and we had briefed this situation at each preflight briefing. In addition, we were roommates and routinely discussed different scenarios of what could happen when flying into the Hanoi area. There was no panic in the cockpit as we agreed to turn to the southwest in order to overfly the least-populated areas of North Vietnam and Laos, so upon our probable ejection, we would have a better chance of not being captured.

At this time, a most unlikely event occurred: Off our left wing at about 1,500ft was the MiG-21 that had just shot his missiles at us! We were certainly glad his cannons, if he had any, were not loaded that day so he was Winchester after firing his two Atoll missiles. He stayed there flying formation with us for quite a while and obviously wondered why this F-4E was still airborne. We were wondering the same thing, but certainly not complaining. He stayed in formation with us for what seemed like a long time.

At this time, we could see Clive 03 in the distance closing in on us. The MiG-21 was directly between us and Clive 03. We were thankful we were not alone now and tried in vain to radio Clive 03 and tell him to shoot down this MiG-21 that was on our wing. MiGs are small and hard to see and being focused on our F-4E, Clive 03 never saw the MiG-21. The MiG pilot became aware of Clive 03, probably by his GCI, and made a rapid 180* turn back to the east, leaving Clive 03 to escort us to the nearest friendly area and to a successful recovery and landing should that be possible. Wes and I had begun preparing ourselves for ejection as we stowed stuff away into the zippered pockets of the G-suit and navigated toward the southwest. With Clive 03 leading us, we were just now starting to believe that #321 would continue flying. Numerous hand signals were traded with the crew of Clive 03 and we knew he was leading us to Nakhon Phenom (NKP) air base in Thailand. Although not home to the F-4s, NKP was a primary emergency recovery base and would serve us well if we made it that far.

We did not know our fuel status and did not attempt air-to-air refueling knowing our system would not operate properly. The flight across North Vietnam and Laos into Thailand was untimed but it was a fairly long time to wonder if landing would be possible. Wes had been careful with the airplane, not making any stressful flight moves, since the missile attack, and I knew he was having some difficulties with the control of the aircraft. Clive 03 escorted us to the NKP approach area and then he went ahead to land first, knowing our landing would shut down the airfield and he was already at Bingo fuel (or worse). NKP had a jolly-green rescue helicopter orbiting in their bail-out area and we could see him at our 2 o’clock position. As we continued our approach to the NKP runway, we were caught up in the jetwash from Clive 03 and determined we must make a 360* turn in order to make a safer landing.

As we began this turn out of traffic towards the bail-out area, we joked that the jolly-green figured he had some business coming his way! So we continued the 360-degree turn and got lined up for a long straight-in approach. We were out of utility hydraulics and used the emergency gear system and got the gear down-and-locked indication, that was good. Our next obstacle was the unknown of at what speed would be necessary for #321 to continue safe flying to the landing. NKP had the cable-arresting system and we planned to land so as to hook up with the approach-end barrier cable. The tail hook was down, we had the cockpits cleaned up for ejection and we were barreling down to the runway. Wes was fighting the aircraft control and I noticed he had the stick pegged far to the right as we maintained 220 knots airspeed. He proved he was an expert pilot as we touched down at 220 knots, the tail hook caught the cable and pulled the plane to a gentle halt.

As the hook released from the cable, the plane rolled into the grass infield and came to a halt. We both made a normal but swift exit from the cockpits and saw the damage for the first time, happy that she stayed airborne.

Photo 1: Craighead left, Zimmerman right, tail hook and cable are visible

Clive 03 gassed up and flew back to Takhli. Wes and I were at NKP with just our flight suits and a few bucks on us, since we had left all personal effects back at Takhli and now needed to hitchhike back to Takhli. It took us 3 days with a puddle-jumper to Utapao and another puddle-jumper to Takhli.

We arrived back at Takhli and resumed flying our sorties. The very next day, they scheduled me for my “mid-tour” check ride, what a bad joke! News and photos of this event traveled around the airbases and we were awarded numerous flight awards by the USAF. Wes was awarded the Koren Kolligian Award for the most outstanding flight safety event of 1972.

We were both transferred to Holloman AFB, NM in December 1972. Wes went on to fly commercial for Continental Airlines and fly F-16s in the Utah ANG. He’s now retired and living in Layton, Utah. I left the Air Force in 1976 and built a custom-homebuilding business in San Antonio, TX.

I again was able to see F-4E #70-321 in May 1974 in a hangar at Eglin AFB, FL. She was being cannibalized for her parts and it is doubtful she ever flew again after that time. On this one day, she took hits from SAM particles, 30mm cannons & heat-seeking missiles, what a fine beast!!

Photo 2: view of the damage

Photo 4: Good ol’ #321 is being towed away

This view begs the question why didn’t the Atoll missiles

continue their flight into the engine tailpipes?

Photo 6: Craighead inspecting the damage, Zimmerman at far right

Photo 3: lost

Photo 7: Craighead & Zimmerman on 26 October 1972, shaking hands after last mission

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 17, 2023

Our Second language in the Military

My friend, Neil Doc Keddie, posted this short piece on our Facebook group page – Brothers of the Nam. I found it hilarious and want to share it with you.

Warning: Rated for Mature Audiences. Lots of Foul Language.!!!!

F*&k!!!! Yes, you heard me right. Certainly, we all knew how to cuss and swear before entering the service. But once we reached Basic Training, we began to see it and use it like it was a second language, which, of course, it was. For many of us, the words and especially the phrases were something that before we had no idea existed. No longer were we a group of trainees. Now we were “every Swinging Dick.” Before we were in the service we used to gather in groups to talk and socialize, but now we were a “Cluster-Fuck, and that “one round would get us all.” Certainly Basic and AIT were like beginning courses, but once we landed in-country, we became fluent. F&*K was no longer just a declarative word, now it became every part of speech there was. So much so that we could make an entire sentence with just that word –so it was all at once noun, verb, adverb, adjective, exclamation mark – indeed the whole works.

Cussing became secondary in nature. I can remember pulling Sick Call at the Aid Station on Firebase Arsenal and taking care of a guy who was suffering from a case of “Jungle Rot.’ Apparently, this was not his first time suffering from it as he wanted to know if we could give him some of the “Shit” that he had used before. The Doc and I looked at each other and then at him and asked “shit?’ Yes, he said that “Super Shit” that he had rubbed on it before. Oh! we said, “The SUPER shit” In fact he really wanted some of the “Super Fantastic Shit.” So, while he sat there, I turned around, grabbed a tube of ointment, got a label, and wrote “Super Fantastic Shit” Use 3 F&*KING times a day.

While we were there we even came up with words that seemed rather far-fetched. While talking with one of the Medics one evening he began to tell the Doc and me about a movie that he had recently seen in which the female lead had “big-assed titties.” “Big-assed Titties? we asked —“Exactly what are those? I forget how he described them now, but it was funny to hear.

One of the great parts of Battalion Training was the fact that for a few days, there was a reunion of the Medics. One of the things that were always good fun was all of us getting together to pull “Battalion Sick-Call” in the morning. On one occasion we had a “Cherry” who we gave the job of writing up the “complaint” of those who came for treatment. We started getting charts that read “rash on balls,” boil on ass” and “pain in dick.” It was funny to read but we had to caution him that these charts were part of the patients’ permanent records and would go with them wherever they went.

Of course, the day finally arrived when we got to go home. In so many cases, we were out of the bush and back on the block in just a few hours. There was no time to detox before we returned to our homes and families, and this posed a problem. It was difficult to get back to speaking in a civilized manner. I found myself saying things like “Could you pass the fu-fu-fu, could you pass the mashed potatoes,” or “What’s on the fu-fu-fu-what’s on TV. After a couple of weeks my mother pulled me aside and asked, “when did you pick up that stutter?” I came up with some lame excuses, but it was a challenge to get back to my old primary language.

You can kind of tell by the photo below that the three of us were accomplished speakers of our new language.

What other examples can you think of? Leave them in the comment section below.

Taken on FB Birmingham. 1970–Doc Gardner, Doc Probst and Me–Doc

If you are interested in seeing more about the slang terms used in Vietnam, then check out the most popular post on my website: https://cherrieswriter.com/2014/02/13/military-speak-during-the-vietnam-war/

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 10, 2023

Baptism by Fire: Becoming a Marine in Practice and by Name

This is one Marine’s story that talks about that defining moment when he considered himself a Marine and fully understood the meaning of Semper Fidelis: Always Faithful. Do any of you feel the same?

Ask any Marine if they can remember the first day they actually became a Marine and you likely will be told it was boot camp graduation day. Whether it was Parris Island or San Diego, only when the senior officer in the graduation program proclaims the graduates “Marines” did the title apply. For officers, it would be a similar graduation from Officer Candidate School when their second-lieutenant butter bars were pinned to their uniforms.

The designation could not come at any time before that, and no matter how well the recruits or officer candidates did at the various stages of training that preceded graduation day, if they didn’t graduate, they were not Marines.

Ron Winter inside a hooch in Quang Tri, South Vietnam, four months and more than 100 missions into his tour. Photo courtesy of the author.

But as many Marines will also tell you, there are other defining moments in the journey to becoming a Marine veteran that eclipse the boot camp experience. These include the baptism by fire, when Marines enter combat for the first time and learn how they will react when the enemy shoots directly at them.

For me, that moment came on June 1, 1968, during an initial assault as we inserted troops into an area south of Khe Sanh where the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) was building a road under the cover of a triple-canopy jungle. I responded appropriately and survived, yet while that was a personal milestone, there was something missing. Even if I couldn’t articulate it, I felt it.

Two more months would pass before I filled in that gap, even though those two months included my first medevacs, reconnaissance team insertions and emergency extractions, and night flights into hot zones—the gamut of missions that helicopter crews face in war.

During the summer of 1968, the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 9th Marine Regiments operated in northernmost I Corps and along the , and opened new firebases south of Khe Sanh near the Laotian border, including landing zones Torch, Robin, and Loon. By mid-August, I had completed nearly 100 missions as a door gunner in CH-46 Sea Knight helicopters in squadron HMM-161 (military helicopter transport squadron), many in that area.

Although my baptism by fire had occurred two months earlier in this same area, and it now was August, this day was different. While the initial assault in June had been the responsibility of the 4th Marine Regiment, later in the summer, elements of the 1st and 3rd Regiments also operated in the area. I could only tell which regiment we carried if the Marine infantrymen had written their unit identification on their packs, which they often did.

The reception we would receive when entering a hot zone was a toss-up, as the NVA was sly and often changed tactics. At times, they opened fire on the lead aircraft—“birds,” as we referred to them—and at other times, they waited for later arrivals who might be lured into thinking the zone was free of the enemy and might possibly be caught off guard by a burst of hostile fire.

Ron Winter stands at his post next to a .50 caliber machine gun inside a Marine CH-46D helicopter between missions in June 1968. Photo courtesy of the author.

On this particular day, they chose to open fire right away. I flew starboard (right) gunner in the fourth aircraft in the flight, and I had a brief-but-ever-so-appreciated advance warning of what waited for us. The crews in the earlier flights had pinpointed the enemy positions in a gully flanked by two ridges on the northern side of the zone.

As soon as the target section came into sight, I opened up with my Browning M-2 (Ma Deuce) .50 caliber machine gun. We usually flew with 100-round boxes of ammo attached to the side of the machine gun with a bungee cord. At a rate of 500 rounds per minute, I emptied the first box in slightly more than 12 seconds.

I should point out here that in the years after Vietnam when I met grunts at veterans events, they often said they hated being forced to sit in a helicopter waiting to land, unable to join in, while the enemy, the gunners, and the crew chief were firing. It was strange for us, too, because we rarely saw those grunts again or heard what they encountered on the ground, or whether our fire had been effective in giving them sufficient time to find cover and turn their fire on the enemy.

Regardless of which unit we worked with, any assault was nerve-wracking for those who wanted to fight but—due to safety concerns—had to sit quietly until we landed and lowered the ramp. This probably explains the actions of a grunt sitting right next to my machine gun that day in August.

When I ran out of ammo in the 100-round box, instead of loading another 100-round box, I reached into a much larger box below the gun mount, grabbing one end of a 500-round ammo belt.

As I reloaded, I noticed the grunt stand and turn toward me. I cocked the .50 and began firing—all this happening in mere seconds—as he grabbed the ammo belt and began to feed the machine gun with a smoothness that instantly spoke of long experience. Out the corner of my left eye, I also saw the crew chief grab his M-14 rifle, switch it to fully automatic, and start firing out the hatch on the starboard side of the aircraft, a few feet forward from my station.

Marines from Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, take five on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in northern Laos, in February 1969, as part of Operation Dewey Canyon. Photo courtesy of the author.

The crew chief and I were about the same size—five foot seven inches or so, less than 150 pounds—and the recoil from the M-14 threw him back a couple of steps each time he fired. But he charged right back to the hatchway and opened up again, oblivious to the force of the recoil. In retrospect, it was kind of funny, but no one was laughing then. We kept firing, and I expended another 200 rounds or so. I ceased firing as we settled into the zone and the crew chief opened the rear ramp using his remote control.

I watched as the grunts charged out to take up their assigned positions in what was a quickly expanding perimeter. But just as he was to turn in the direction of the battle, the grunt who had been feeding my machine gun stopped, looked back for an instant, and flashed “Thumbs up” to me, accompanied by the biggest grin I could have imagined. Then he was gone.

In that instant, for the first time, I truly felt like a member of the Marine air-ground team. I didn’t know the Marine sitting next to my position, but he instantly reacted, and we each did our part in the brief but intense firefight. And he obviously was grateful to have a part in the action rather than sitting still, enduring what we referred to as the “pucker factor.” Much later, I realized that a similar scenario could have occurred with myriad other participants, but this moment was our time on center stage.

A CH-46 helicopter from HMM-161 hovers over Fire Support Base Lightning, a forward artillery base manned by troops of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, in February 1969. The Fire Support Base was carved out of the wilderness to support U.S. Marine operations in the A Shau Valley adjacent to the Laotian border. Photo courtesy of the author.

I have heard it said that the entire course of our lives can change in an instant, and decisions we make in that time can affect everything we do thereafter. The time spent in that firefight was two minutes—tops—yet it caused a sea change in my feelings about my role in the war we were fighting.

I’m not talking about philosophical issues here, or weighty concerns about the justification for America’s involvement in Vietnam. I am talking about the simplest of factors: two Marines, side by side, helping each other stay alive for the foreseeable future, which could be less than another minute. Nearly a year and ultimately more than 300 missions after that firefight, I returned home, went back to school, and tried to reenter society. But the America I returned to, and I hope that grunt made it, too, was not welcoming, and I endured my share of physical and emotional abuse.

Lance Cpl. Ronald Winter aboard the USS Princeton, LPH-5, in May 1968, en route to Quang Tri, South Vietnam, with Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 161. Photo courtesy of the author.

In the first half of a 20-year journalism career, I was mocked and denied promotions, advancement, and pay raises by people who had never served their country and despised those of us who had. Not everyone, of course, but enough to make an impact on my life.

But regardless of what I faced in the years after Vietnam, I never forgot that moment when two Marines seamlessly took the fight to the enemy—a team that was created on the spot but worked as though we had been practicing forever—and did the job that was required. I often passed that moment on to acquaintances who needed a boost, and who needed to remember what it was like back in “The Nam.”

During my journalism career, I developed a reputation for calmness under deadline pressure, and occasionally, when asked about it, I would simply say, “No one is shooting at me.”

The success and teamwork of that moment helped me be successful in later endeavors, and the reward was far better than any medal because, from that moment on, I knew without question that I had truly joined the brotherhood of Marines, and the expanded brotherhood of combat veterans from all services. And for the first time, I fully understood—not by definition, not superficially, but deep inside me—the meaning of Semper Fidelis: Always Faithful.

Ronald Winter

Ronald WinterRonald Winter is a Marine Corps Vietnam veteran and author, including the recently released Victory Betrayed: Operation Dewey Canyon. He joined the Marine Corps in January 1966 and served four years on active duty, including 13 months in Vietnam, flying more than 300 missions as an aerial gunner. He was awarded 15 air medals, combat aircrew wings, the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry, and numerous other decorations. Winter later earned degrees in electrical engineering and English literature, and spent 20 years as a print journalist, earning numerous awards for investigative reporting, as well as a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video and changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

June 3, 2023

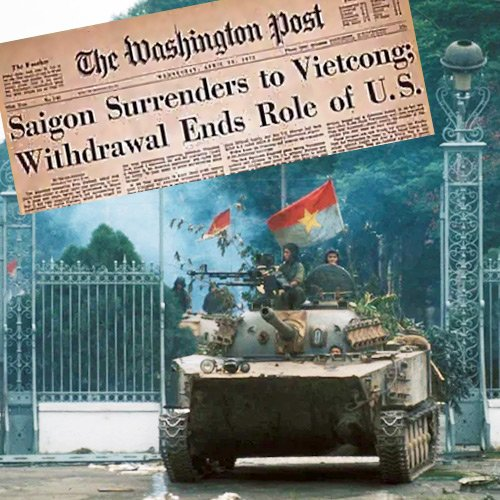

Mauled in Laos – Operation Lam Son 719

A bungled raid into Laos by the South Vietnamese Army in early 1971 exposed grave deficiencies in its operational abilities. The ARVN retreated from Laos before their targeted deadline and had already sustained almost 50% casualties. Only U.S. airpower prevented complete disaster.

WARNING, THIS IS A RATHER LONG AND DETAILED ARTICLE

By John WalkerThe South Vietnamese rangers huddled in their trenches and bunkers at landing zone Ranger North throughout the day of February 19, 1971, as mortar shells crashed inside the perimeter. The deadly shells sent geysers of dirt toward the low-hanging, gray sky over eastern Laos. To counter the encroaching North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars, U.S. Cobra gunships and F-4 Phantoms took turns rolling in to blast enemy positions. The 5,000 enemy soldiers laying siege to the hilltop base outnumbered the rangers 10 to 1. By the 11th day of Operation Lam Son 719, U.S. air support was the only thing that separated life from death for the beleaguered troops of the 39th Ranger Battalion at Ranger North.

At dusk, a regiment of the NVA 308th Division began a steady mortar bombardment of the base. Fanatical NVA regulars, who were supported by Soviet-built PT-76 and T-54 tanks, charged the perimeter repeatedly and eventually broke through. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out in several places. The rangers suffered from a severe shortage of antitank weapons and were not experienced with those they had. The air swarmed with U.S. supply and medevac helicopters, as well as aerial rocket artillery. The ground around the hilltop base lit up periodically with flames from napalm canisters dropped by Phantoms that roared down on the jungle. UH-1 “Huey” helicopters zipped onto the smoke-shrouded hilltop bearing supplies and, when possible, removed wounded while the Cobras pumped rockets at NVA caught in the open. NVA soldiers desperately tried to knock the Hueys from the sky with their AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades, and heavy antiaircraft machine guns.

Dawn on February 20 revealed the contorted bodies of hundreds of dead NVAs both on the hillsides and within the perimeter. Crews of U.S. helicopters alighting on the hilltop did their best to keep back panicked rangers who tried to grab their skids, threatening to overload their fragile airships. In the fighting over a three-day period, the force of 500 rangers on the hilltop base had dwindled to 323.

It was clear that afternoon that the Rangers could not hold off the NVA. It also was clear that U.S. air units could not evacuate their allies under such intense fire. With no other option, the ranger commander ordered his men to fight their way out toward Ranger South just over three miles away. What followed was a running battle in the frantic retreat to Ranger South. Only 109 able-bodied survivors and 92 wounded made it to safety by nightfall. As for the NVA casualties, they lost at least 600 men, and perhaps substantially more. It was a scenario repeated at several other firebases established to support the South Vietnamese raid to temporarily sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail and disrupt NVA offensive operations.

A U.S. tank covers South Vietnamese troops as they prepare to enter Laos in early February 1971. The ambitious raid was conceived partly as a test of how the South Vietnamese would fare in a ground operation without American advisers.

A U.S. tank covers South Vietnamese troops as they prepare to enter Laos in early February 1971. The ambitious raid was conceived partly as a test of how the South Vietnamese would fare in a ground operation without American advisers.By 1970, with the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Southeast Asia finally underway, it was apparent the long-standing American policy of supposedly respecting the neutrality of the bordering Indochinese countries of Laos and Cambodia while fighting a localized war of attrition inside South Vietnam had been a profound strategic blunder. As early as 1960, North Vietnamese ground forces, who established the Ho Chi Minh Trail as their principal route for funneling communist troops, weapons, and supplies into South Vietnam had invaded and occupied large portions of Laos and Cambodia. The restriction confining the ground war to South Vietnam did not apply to American aerial bombing; indeed, North Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail were bombed extensively for years, yet the bombing campaign was not decisive in determining the war’s outcome. Since 1966, over 630,000 North Vietnamese soldiers, 100,000 tons of foodstuffs, 400,000 weapons, and 50,000 tons of ammunition had traveled south through the maze of gravel and dirt roads, footpaths, and river transportation systems that crisscrossed southeastern Laos and linked up with a similar logistical system in neighboring Cambodia known as the Sihanouk Trail.

Following Prime Minister Lon Nol’s overthrow of Cambodia’s Prince Norodom Sihanouk on March 18, 1970, though, the new pro-American Lon Nol regime denied the use of the port of Sihanoukville to communist shipping. This was an enormous strategic blow to North Vietnam since 80 percent of all military supplies that supported its effort in the far south had moved through this port. Lon Nol also ordered the NVA and Viet Cong (VC) out of Cambodia. The VC were South Vietnamese communist insurgents, fighting mostly as irregulars under the banner of the National Liberation Front and under North Vietnamese control.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail began in North Vietnam and ran through Laos into northern Cambodia, with spurs branching into each of almost two dozen bases along the border. The eastern sector of the Laotian panhandle had long been home to many vital logistical installations and base areas. The main hub of the entire complex in this sector of the trail was Base Area 604, sited in and around the district town of Tchepone, Laos, roughly 24 miles west of the Laos-Vietnam border. After the Cambodian government’s closure of the port of Sihanoukville, Base Area 604 became even more vital to the North Vietnamese war effort.

The next largest supply base was Base Area 611 in Muong Nong Province, south and east on Route 914 from Tchepone. It was much closer to the Vietnamese border and was located on the western fringe of the AShau Valley, where it entered Laos. In late 1970, expecting an attack on Laos, the North Vietnamese created a field command—the B-70 Corps commanded by General Le Trong Tan, its nucleus the 304th, 308th, and 320th Divisions—specifically to fight in Laos and had substantial capacity to reinforce their original dispositions.

A further blow to the communist logistical system came in spring 1970 when U.S. and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces crossed the border into Cambodia in strength and attacked NVA/VC base areas during the controversial Cambodian incursion. That allied offensive into Cambodia is sometimes portrayed as a strategic failure, but it was not. Though hugely unpopular in the United States, the operation was in fact the key event needed to sever the enemy’s lines of communication and logistics in Cambodia, ease the American withdrawal program from the theater, and showcase the success of the Vietnamization program while also boosting the morale of ARVN soldiers.

The South Vietnamese established fire bases manned by Army rangers to prevent ambushes against the main column traveling west on Route 9.

The South Vietnamese established fire bases manned by Army rangers to prevent ambushes against the main column traveling west on Route 9.The Cambodian incursion was a success by any measure. The allies seized enough weapons and ammunition to arm 55 battalions of an enemy main-force unit, killed 11,363 enemy soldiers, and captured over 2,000 soldiers. But the Allies failed to locate the military and political headquarters of the NVA/VC forces, and they also failed to encounter large enemy concentrations because the enemy had withdrawn deeper into Cambodia. Military activity increased after the operation in both northern Cambodia and southern Laos as the North Vietnamese attempted to establish new infiltration routes and base areas.

After the near destruction of the enemy’s logistical system in Cambodia, U.S. headquarters in Saigon determined the time was favorable for a similar campaign into the Kingdom of Laos (the coalition government of Laos had come to an agreement with influential North Vietnamese sympathizers that prevented them from objecting to communist operations inside their country). If such an operation were to be carried out, it would have to be done quickly while American military assets were still available in South Vietnam. Such an operation might create severe supply shortages that would be felt by NVA/VC forces for at least one year, and possibly two, thus giving the United States and its ally a respite from enemy offensives in the vital northern provinces for a year or more.

The allies discovered signs of increased NVA logistical activity in southeastern Laos, an activity that heralded just such an offensive. Communist offensives usually took place near the conclusion of the Laotian dry season (from October through March) after logistics units had pushed supplies through the system. One U.S. intelligence report estimated that 90 percent of NVA material coming down the trail at that time was being funneled into the three northernmost provinces of South Vietnam to prepare for offensive action. This buildup was alarming to both Washington and the American command in Saigon and prompted the perceived necessity for a preemptive attack to disrupt any attempted communist offensives.

On December 8, 1970, in response to a request from the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, a highly secret meeting was held at Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) headquarters in Saigon to discuss a possible ARVN attack into southeastern Laos, across the border from I Corps in northern South Vietnam. The group’s findings were sent to the Joint Chiefs in Washington. By mid-December, U.S. President Richard Nixon had become intrigued by the idea of offensive actions in Laos and had begun efforts to convince General Creighton Abrams, supreme MACV commander in South Vietnam, and members of his own cabinet of the efficacy of such an attack. Nixon was well aware that another border crossing would severely inflame public opinion, but he and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were overly optimistic and believed a clear-cut ARVN victory would trump any political consequences. As promised, Nixon had begun the systematic withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam, lowering U.S. troop strength there to around 157,000 men by early 1971. (Nixon assumed office in January 1969 and troop withdrawals began in the summer of that year.)

On January 7, 1971, they authorized MACV to begin detailed, highly secret planning for an attack against Base Areas 604 and 611 in lower Laos. On the American side, they assigned the task to Lt. Gen. James Sutherland, commander of the U.S. XXIV Corps, who was given only nine days to submit it to MACV for approval. The operation would eventually comprise four distinct phases. During the first phase, the U.S. 45th Engineering Group would seize, rebuild, and secure Route 9, the main road leading east to and into Laos; the 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) would reoccupy the abandoned Khe Sanh Combat Base, which would become the logistical hub and airhead of the ARVN part of the operation; and, in an operation dubbed Dewey Canyon II, the 101st Airborne Division would conduct diversionary operations into the AShau Valley near the Cambodian border, long a communist stronghold.

A North Vietnamese armored vehicle moves along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Hanoi’s initial response to the raid was gradual because it believed North Vietnam was in danger of being attacked either across the demilitarized zone or from the sea by an amphibious landing.

A North Vietnamese armored vehicle moves along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Hanoi’s initial response to the raid was gradual because it believed North Vietnam was in danger of being attacked either across the demilitarized zone or from the sea by an amphibious landing.The second phase entailed a three-pronged ARVN armored/infantry attack west along Route 9 across the border into Laos, pushing for the town of Tchepone, the perceived nexus of Base Area 604. Total American air, artillery, and logistical support—but no U.S. advisers or ground troops, who were now prohibited by law from entering Laos—would support the South Vietnamese incursion. The column’s advance along Route 9 would be protected by a series of leapfrogging, heliborne infantry assaults on both sides of the highway, where rapidly erected ARVN firebases and landings zones would cover the northern and southern flanks of the road-bound main column. The operation’s third phase called for search and destroy missions within Base Area 604 and, it was hoped, against Base Area 611 if conditions permitted. Then, ARVN forces would retire, either going back along Route 9 or southeast to Base Area 611, through the part of the AShau Valley that jutted into Cambodia, and across the border.

Because of the South Vietnamese military’s notorious carelessness regarding security precautions and the uncanny ability of communist agents to uncover detailed information, the planning phase lasted only a few weeks, divided between the American and South Vietnamese high commands. At the operational levels, it was limited to the intelligence and operational staff of the ARVN I Corps, whose commander, Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, would command the operation, and Sutherland’s XXIV Corps. MACV and the South Vietnamese Joint Chiefs of Staff briefed Lam in Saigon just days before the operation’s start. His operational area was restricted to a corridor no wider than 15 miles on both sides of Route 9 and penetration no deeper than Tchepone.

In the highly politicized South Vietnamese military’s command structure, where the support of key political figures was of paramount importance in the promotion to and retention of command positions, the issues of command, control, and coordination proved problematic. Lt. Gen. Le Nguyen Khang, South Vietnamese Marine Corps commander and protégé of Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, whose Marines were scheduled to participate in the incursion, outranked Lam, who was supported by President Nguyen Van Thieu. The same situation applied to Lt. Gen. Du Quoc Dong, commander of ARVN airborne forces also scheduled to participate. Rather than take orders from Lam, both commanders remained in Saigon and delegated their command authority to subordinate officers, which certainly did not bode well for the success of the incursion. They dubbed the operation Lam Son 719 after the village of Lam Son, the birthplace of the legendary Vietnamese patriot Le Loi, who defeated an invading Chinese army in 1427. The numerical designation came from the year 1971, and the main axis of the attack was Route 9.

The attempt at secrecy jeopardized logistical and communications preparations that required lengthy lead time, and a combined tactical command post was not established until the operation was well underway. Most units did not learn about their planned participation until January 17. The Airborne Division received no detailed plans until February 2, less than a week before the campaign was to begin. Some of the best and most experienced units, the paratroopers and Marines, had always deployed in their own areas of operation as separate battalions and brigades and had no experience cooperating in combined unit operations. The U.S. 101st Airborne Division’s assistant commander later said, “Planning was rushed, handicapped by security restrictions, and conducted separately and in isolation by the Vietnamese and the Americans.” U.S. helicopters, artillery, and supplies were moved at the last minute into the Khe Sanh Combat Base, where an entirely new airstrip had to be constructed. Because there were few possible locations for attacks in Laos, and the North Vietnamese were already expecting some kind of activity in the area, any attempt at secrecy failed.

On their own, for the first time without American advisers, South Vietnamese generals faced their biggest test yet. Lam Son 719 was ARVN’s largest, most complex, and most critical operation of the war. The lack of time for adequate planning and preparation, as well as the absence of any real discussion of military realities and the true capabilities of the ARVN, might prove decisive. Nixon gave his final approval for the mission on January 29 and the following day Operation Dewey Canyon II began (it was hoped the 101st Airborne’s feints into the AShau Valley might draw NVA attention away from what was going on at Khe Sanh). On the morning of January 30, as well, armored and engineer elements of 1st Brigade, U.S. 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) headed west on Route 9 while the brigade’s infantry units were helilifted directly into Khe Sanh. They did not notify the government of Laos in advance of the intended operation; Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma learned of the invasion of his country only after it was underway (the same had been true of the Cambodian incursion a year earlier).

South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu.

South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu.Tactical airstrikes set to precede the incursion to suppress suspected antiaircraft positions had to be suspended for two days due to poor weather. After a massive preliminary artillery bombardment and 11 B-52 Stratofortress missions, the incursion began on February 8, 1971. Spearheaded by M-41 light tanks and M-113 armored personnel carriers, a 4,000-man ARVN armor and infantry task force, comprising the 1st Armored Brigade, the 1st and 8th Airborne Battalions, and the 11th and 17th Cavalry Regiments, crossed the border and advanced six miles westward unopposed along Route 9.

To cover the northern flank, the 39th Ranger Battalion was helilifted into Ranger North while the 21st Ranger Battalion air assaulted into Ranger South. Meanwhile, the 2nd Airborne Battalion established FSB 30 while the 3rd Airborne Brigade Headquarters and 3rd Airborne Battalion moved into FSB 31 (both north of the road as well). These outposts were to serve as tripwires for any communist advance into the zone of the ARVN incursion. South of Route 9, units of the crack 1st ARVN Infantry Division simultaneously combat assaulted landing zones Blue, White, Don, and Brown, and FSBs Hotel, Hotel 2, Delta, and Delta 1, to establish the southern flank of the advance.

Lam Son 719 was underway. Although intelligence reports showed the terrain along Route 9 in Laos was favorable for armored vehicles, in reality, it was a neglected, 40-year-old, unevenly surfaced, single-lane dirt road with high shoulders on both sides that left no room for maneuver. The entire area was filled with huge bomb craters, undetected earlier by aerial reconnaissance, because of dense grass and bamboo. Tracked vehicles, jeeps, and trucks were, therefore, restricted almost entirely to the road, which threw the burden of reinforcement and resupply onto U.S. aviation assets. American helicopter units thus became the essential mode of logistical support, a role made increasingly more dangerous by regular low cloud cover and unremitting antiaircraft fire.

The mission called for the central column to advance down the valley of the Se Pone River, a relatively flat area of brush interspersed with huge swaths of jungle, dominated by heights to the north and the river and more mountains to the south. From the second day forward, the column was exposed to fire from the heights as NVA gunners fired down from preregistered machine-gun and mortar positions. U.S. Army helicopter pilots flying gunship and resupply missions—and later when they attempted to rescue ARVN troops from besieged hilltop firebases—encountered savage, accurate antiaircraft fire. The NVA’s favorite antiaircraft weapon, among others, was the 12.7mm Soviet-made heavy antiaircraft machine gun, which fired 600 rounds per minute and could damage an aircraft at elevations up to 3,000 feet. The highly accurate weapon helped bring down of hundreds of American helicopters during the war.

The ARVN column secured Route 9 as far as the village of Ban Dong, known to the Americans as A Luoi, 12 miles inside Laos approximately halfway to Tchepone. By February 11, A Luoi had become ARVN’s central firebase and command center for the operation. The plan now called for a quick ground thrust to secure Tchepone, but South Vietnamese forces found themselves stalled at A Luoi while awaiting overdue orders from Lam to continue. Abrams and Sutherland flew to Lam’s forward command post at Dong Ha to speed up the timetable. After the commanders’ meeting, Lam decided to first extend the 1st ARVN Infantry Division’s line of outposts south of Route 9 farther westward before the projected advance, which took another five days.

U.S. artillerymen near the Laotian border fire mortars into Laos in support of the advancing South Vietnamese. American helicopter units supplied the South Vietnamese throughout the operation.

U.S. artillerymen near the Laotian border fire mortars into Laos in support of the advancing South Vietnamese. American helicopter units supplied the South Vietnamese throughout the operation.Hanoi’s response to the incursion was gradual because North Vietnamese leaders believed their country was in danger of being attacked, either by an allied ground assault north across the Demilitarized Zone or a U.S. Marine amphibious landing off their eastern coast. When Hanoi’s leaders realized they were not going to be invaded, units of the B-70 Corps were ordered toward the Route 9 front. The 2nd NVA Division moved up from south of Tchepone and moved east to help meet the ARVN threat, while other units marched to the area from the AShau Valley. By early March, the North Vietnamese had massed some 36,000 soldiers in the area, giving them a numerical superiority of two to one over ARVN’s 17,000 men. The NVA committed elements of five infantry divisions (2nd, 304th, 308th, 320th, 324B) along with all their armor and artillery support, all the logistical units operating in the area, an engineer regiment, six well-camouflaged antiaircraft battalions, and six sapper battalions.

The NVA had massed its combat power for a larger purpose than defending its critical supply route. They were determined to seize an opportunity to fight a decisive battle on advantageous terms, destroy a large ARVN force, and thoroughly discredit and disrupt Vietnamization. The NVA opted to isolate the northern ARVN bases first, pounding those outposts with round-the-clock mortar, artillery, and rocket fire, as well as fierce antiaircraft fire against supporting air units. Although ARVN firebases were equipped with artillery, their guns were outranged by the enemy’s Soviet-supplied 130mm and 152mm pieces, which simply stood off and pounded ARVN positions at will. Massed ground attacks backed by artillery and armor would then finish the job.

While the NVA assault on Ranger North raged, Thieu visited I Corps headquarters and was notified of the attacks on the ranger bases and the overall major increase in enemy activity that made an advance on Tchepone questionable. Thieu advised Lam to postpone the main column’s advance on Tchepone and instead have the 1st ARVN Division, south of Route 9, begin a push southwest in the direction of Tchepone.

The North Vietnamese next shifted their attention to Ranger South. The outpost’s 400 ARVN troops and the survivors from Ranger North fought bravely for two days to hold the post, after which Lam ordered them to fight their way three miles southeast to FSB 30. Another casualty of the campaign, though an indirect one, was South Vietnamese General Do Cao Tri, III Corps commander and ARVN hero of the Cambodian fighting a year earlier. Ordered by Thieu to take over for the overmatched Lam, Tri died in a helicopter crash on February 23 while en route to his new command. That same day, FSB Hotel 2, south of Route 9, came under an intense infantry attack and was evacuated the next day.

FSB 31 was the next ARVN position to come under heavy enemy pressure. Dong, the Airborne Division commander, had opposed deploying his elite paratroopers in static defensive positions because he believed it stifled their usual aggressiveness. When vicious NVA antiaircraft fire made resupply and reinforcement of FSB 31 almost impossible, Dong ordered elements of the 17th Armored Squadron to advance north from A Luoi to reinforce the base. The armored force never arrived, however, because of conflicting orders from Lam and Dong, who halted the armored advance a few miles south of FSB 31. On February 25, the NVA pounded the base with artillery fire and then launched a conventional ground attack. Smoke, dust, and haze at first prevented observation by an American forward air control (FAC) aircraft, which was flying above 4,000 feet to avoid antiaircraft fire. When a Phantom was shot down not far away, the FAC left the area to direct a rescue operation, leaving the defenders with no one to direct fire support. NVA troops and tanks overran the base, capturing 3rd ARVN Brigade’s commander, while losing about 250 men killed and 11 tanks lost. The ARVN paratroopers suffered 155 killed and over 100 captured.

U.S. strategic and tactical bombers pulverized the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the Laotian panhandle before the mission got under way.

U.S. strategic and tactical bombers pulverized the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the Laotian panhandle before the mission got under way.A bit farther east, FSB 30 lasted almost another week. Although the steepness of the hill on which the base was situated prevented armor attacks, NVA artillery barrages were extremely effective, and by March 3 all the base’s 11 howitzers had been put out of action. ARVN armor and infantry from the 17th Cavalry moved north in a relief attempt, and within days, North and South Vietnamese tanks fought the first armored battles of the war. In the five days between February 25, the day FSB 31 fell, and March 1, three major engagements took place. With the help of U.S. airstrikes, the ARVN destroyed 17 PT-76 Soviet-built tanks and six T-54s at a loss of three of its five M-41 tanks and 25 M-113 armored personnel carriers. On March 3 the ARVN relief column encountered an NVA battalion without supporting armor, and with the assistance of B-52 strikes killed 400 North Vietnamese soldiers.

During each of the enemy’s attacks upon FSB 30 and the ARVN relief column, communist ground forces suffered heavy losses from B-52 and tactical airstrikes, armed helicopter attacks, and various forms of ground fire. In each instance, however, the NVA attacks were pressed home with competence and determination that both impressed and profoundly shocked those that observed them. The NVA lost over 1,130 soldiers killed in the battle.

With their main column stalled at A Luoi and the rangers and paratroopers fighting for their lives, Thieu and Lam now launched an airmobile assault upon Tchepone itself. The Tchepone area was sparsely populated; the war had evacuated or destroyed most of the nearby villages and towns. There was not much of military importance within the deserted town of Tchepone; most of the NVA’s supplies and other war material had been moved to caches in nearby forests and mountains west and east of the town proper. A particularly large, lightly defended cache was located just west of Tchepone, but the ARVN was unable to reach it. But because the Tchepone road junction was near the center of NVA logistical activity in the vital Laotian panhandle area, the ghost town had become a political and psychological symbol of great importance, more than an object of military value.

American commanders and news media had focused on Tchepone as Lam Son 719’s main objective. If ARVN forces could occupy at least part of the city, therefore, Thieu would have a political excuse for declaring a victory, of sorts, and withdrawing his forces to South Vietnam, as well as gaining political capital for the upcoming fall elections and saving his elite units from destruction. Thieu’s orders called for an assault on Tchepone, not with the main armored column, but with elements of the crack 1st Infantry Division now deployed south of Route 9. The occupation of vacated firebases south of the road would be taken over by South Vietnamese Marine Corps units stationed back at Khe Sanh as the operational reserve.

To Thieu’s credit, with the main ARVN column still miles away at A Luoi, the air assault on Tchepone caught the North Vietnamese off guard. It began on March 3 when one battalion from 1st Division was helilifted into two firebases, Sophia and Lolo, and landing zone Liz, all south of Route 9. Eleven helicopters were shot down and another 44 were damaged. Three days later, in the biggest helicopter assault of the war, 276 Hueys, protected by Cobra gunships and fighter aircraft, lifted two more battalions into landing zone Hope, 21/2 miles north of Tchepone. They lost only one helicopter to antiaircraft fire and an entire regiment of the ARVN’s best soldiers, several thousand men, was now on the ground in and around Tchepone. The NVA had not anticipated the move and could not react quickly enough to stop it; they did, however, hit the four bases, notably Lolo and Hope, with long-range artillery barrages.

North Vietnamese ground troops break through the perimeter of a ranger firebase during Lam Son 719. The communist attackers were supported by Soviet-built PT-76 and T-54 tanks.

North Vietnamese ground troops break through the perimeter of a ranger firebase during Lam Son 719. The communist attackers were supported by Soviet-built PT-76 and T-54 tanks.Not far from Tchepone were several large storage areas still stocked with weapons, ammunition, medical supplies, rations, and equipment. Other areas nearby were used for troop replacement and training. ARVN soldiers scoured Tchepone and the surrounding area for almost a week, methodically destroying everything in sight or using artillery, tactical air, or gunships to destroy depot areas. Several thousand NVA soldiers (ARVN claimed 5,000), mostly rear area troops or troops in rest areas, were killed and another 69 were captured. Almost 4,000 captured enemy weapons were airlifted out and returned to South Vietnam and several thousand tons of enemy equipment were destroyed.