Adam Tooze's Blog, page 13

October 2, 2022

Chartbook #157: The bond market massacre of September 2022.

One week on from the shock announcement of the UK’s mini-budget, the pound sterling has recovered to the levels it was at before the panic. The UK, however, is far from out of the woods. Sterling may have rebounded, but the gilt market – the UK Treasury market – is on life support from the Bank of England. With interest rates surging, mortgage lending is drying up. The UK economy is heading towards a recession. And it is not just the UK that is under stress. On the other side of the Atlantic too, tremors are running through the US Treasury market, the foundation of the dollar system.

From a week of turmoil in the UK financial markets, we have learned four things.

(1) We are reaching the point in the monetary tightening cycle in which things begin to break. Truss and Kwarteng are clearly counting on the Bank of England to offset the shock to markets by raising rates. And yields have certainly surged as UK bonds have sold off.

Here is a chart of the price of the 30 year UK government bond

— Jens Nordvig

Fixed income is a misnomer… pic.twitter.com/lvxfq9MEGY(@jnordvig) September 27, 2022

But rather than restoring equilibrium, the spectacular collapse in the price of long-dated UK bonds (and the associated rise in yields) exposed a dangerous trigger mechanism in the UK financial system. The problem was the stress unleashed in the pension sector by rapidly rising rates. As interest rates surged, pension funds that hold hedging bets against the possibility that interest rates will fall – so-called liability-driven investment strategies – faced calls to post more capital. As Toby Nangle, formerly a multi-asset fund manager, identified in an excellent Financial Times article in July this year.

… £1.5 trillion of assets held by UK pensions … have been hedged in so-called LDI trades. LDI (Liability Driven Investment) helps to match pension funds’ liabilities (future payments to pensioners) with the schemes’ assets.

As Nangle explains in exemplary style:

The Pensions Regulator estimates that every 0.1 percentage point fall in UK gilt yields increases a conservative measure of UK scheme liabilities by £23.7bn. In the decade to December 2020, long-dated, 25-year gilt yields fell by more than 3.5 percentage points and scheme liabilities increased by £960bn (about 40 per cent of GDP). Pension schemes can’t control wild swings in their liabilities’ value. But they are not completely helpless. They can invest their assets so that they become relatively indifferent to bond market gyrations, and this is where LDI comes in. As bond prices determine the valuation of pension liabilities, moving pension assets into bonds will effectively hedge the volatility of liabilities. The problem is that few pension schemes are well-funded enough to make this trade. Instead, schemes invest a portion of their assets in liability-matching bonds and a portion in growth assets — corporate credit, equities, property. They then hedge the risks of that strategy with derivatives, using bond assets as collateral. The hope is that growth assets will deliver decent returns and make them fully funded while the derivatives will desensitise them to future interest rate swings. The results have been good, but have also left pension funds as counterparties to enormous quantities of leverage in the financial system

That risk was starkly exposed when rates shot up. Added to which, since UK pension funds invest not only in UK gilts but also in foreign bonds, as the pound sterling plunged they faced margin calls on foreign exchange derivatives. When funds try to meet those margin calls they need to raise cash fast. Under normal circumstances UK gilts, like US Treasuries are a safe piggybank of liquidity. But in a fire sale they lose value too. As one market participant observed:

“Gilts are a source of liquidity. Now, the thing is that your gilts are also losing money. So basically, your derivatives are getting worse and worse and worse, and your gilts are getting worse. So, the whole thing is getting really bad. Whatever you want to post for collateral is getting worth less,

These trigger mechanism do not appear to have been on the Bank of England’s radar. This raises once again the nagging question of what the key people in central banks and financial regulators – not just in the UK but around the world – choose not to know about the inner-workings of vital financial markets.

(2) Global bond markets interact in subtle, non-mechanical ways. I underestimated this effect in a newsletter last week where I flippantly declared the UK gilt market too small to matter. In fact, at a time of general nervousness, the spasm in the UK market rippled around the world. The EU felt the impact.

EU side now very concerned about contagion risks UKG's fiscal actions pose to financial stability in the Eurozone

— Mujtaba Rahman (@Mij_Europe) September 29, 2022

Plenty of Euro area banks and insurance firms are exposed to UK gilts

This is serious. EuropeanCommission is very worried. IMF is worried. White House is worried

And so too did the US. As one market participant observed: “At the start of the week we were seeing moves in US Treasuries that could only be explained by what was happening in the UK.” In part this sensitivity of US markets is explained by deteriorating liquidity. As Bloomberg reports:

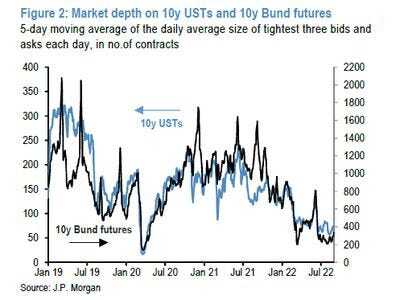

Liquidity in the Treasury market is extremely low at the moment. Liquidity conditions for rates markets this year resemble the conditions seen in the pandemic and the period after the Lehman crisis, JPMorgan data show.

In what the FT dubbed a “volatility vortex”, falling liquidity – fewer participants in the market – leads to higher volatility, which leads to a further withdrawal from the market by major players, which further reduces liquidity, and so on.

In this precarious situation, the news from London had an outsized impact.

As Bloomberg reported Bob Miller, head of Americas fundamental fixed income at BlackRock Inc., the world’s biggest asset manager:

“You can see the footprints of the Gilt market all over the US Treasury market in the past week … The signal value from the price action in the US bond market is being significantly degraded by non-domestic factors.”

Analysts at JPMorgan highlight the fact that US investors have been intently focused on the state of the global market. As Tracy Alloway writes on Bloomberg

average volatility of US rates during Asian and European trading hours has also increased this year.

As one market particpant remarked to Alloway:

“The global nature of the current inflation backdrop, coupled with the emerging globally synchronized policy tightening that is underway, has resulted in much more frequent instances of US rates responding to new information from policy developments abroad … This has led to increased volatility of US rates in non-US trading hours.”

This raises the question of whether there are vulnerabilities in the US market akin to those exposed in the UK. It is hardly reassuring that sales of new Treasury bonds have drawn lack lustre demand and that some market participants were even talking of a ‘buyers’ strike’. And one might ask whether it is truly reassuring when Janet Yellen as Treasury Secretary is forced to affirm that:

“We haven’t seen liquidity problems develop in markets — we’re not seeing, to the best of my knowledge, the kind of deleveraging that could signify some financial stability risks … With the United States moving faster than many other countries, we’re seeing upward pressure on the dollar and downward pressure on many other foreign currencies … To me, these kinds of developments — which represent a tightening of financial conditions — are part of what’s involved in addressing inflation. … I think markets are functioning well.” She added, “The overall environment is one of high inflation in many advanced economies. Central banks are addressing it in almost all countries — other than China — but operating at different speeds and different paces.”

The sensitivity of the US market to the UK, raises the question of the overall fragility of global debt markets. Last week tremors were running through euro government bond markets including the German Bund market. The fear is that as central banks end the long period in which they systematically supported bond markets, deep cracks will be exposed. And that was rather confirmed by events in the course of the week.

(3) If it was as shock in the UK that echoed around the world, it is also true that the Bank of England’s intervention on Wednesday helped to calm the situation. Early on Wednesday the yield on the US 10-year Treasury rose above 4% for the first time since 2010. Then when the Bank of England moved in, the market abruptly changed direction.

Far more nakedly than in 2020, the Bank of England’s hurried interventions in September 2022 have exposed the forces that truly propel central bank intervention in the current dispensation. The policy of asset purchases may look like expansionary macroeconomic policy – a resumption of QE or a coordination of monetary with fiscal policy. They may look like impressive demonstrations of the power of central banks. But they are, in fact, crisis-driven defensive reactions to the spasms of leveraged, market-based finance. What is at stake is not fiscal dominance – the central bank following the lead of the elected government – but financial dominance. The central bank is being forced to act by financial market stress.

— Ed Conway (@EdConwaySky) September 28, 2022

NEW

On the @bankofengland intervention:

Am told the BoE were responding to a “run dynamic” on pension funds – a wholesale equivalent of the run which destroyed Northern Rock.

Had they not intervened, there would have been mass insolvencies of pension funds by THIS AFTERNOON.

By Tuesday 27 September, major players in London were screaming for the Bank of England to act:

A senior executive at a large asset manager said they had contacted the BoE on Tuesday warning that it needed “to intervene in the market otherwise it will seize up”

But the Bank was not yet ready to act. That changed on Wednesday 28th.

“If there was no intervention today, gilt yields could have gone up to 7-8 per cent from 4.5 per cent this morning and in that situation around 90 per cent of UK pension funds would have run out of collateral,” said Kerrin Rosenberg, Cardano Investment chief executive. “They would have been wiped out.”

For the Bank of England it was a shocking pivot. Rather than selling gilts from the portfolio accumulated during the response to the 2020 crisis – Quantitative Tightening – the BoE reversed itself. It began buying long-dated bonds at a rate of up to £5bn a day for 13 working days. As the FT reported:

The bank stressed that it was not seeking to lower long-term government borrowing costs. Instead it wanted to buy time to prevent a vicious circle in which pension funds have to sell gilts immediately to meet demands for cash from their creditors. That process had put pension funds at risk of insolvency, because the mass sell-offs pushed down further the price of gilts held by funds as assets, requiring them to stump up even more cash. “At some point this morning I was worried this was the beginning of the end,” said a senior London-based banker, adding that at one point on Wednesday morning there were no buyers of long-dated UK gilts. “It was not quite a Lehman moment. But it got close.”

(4) Talk of markets at that point become euphemistic and we must ask, beyond the need for “systemic stability”, who are the principal and immediate beneficiaries of these interventions? Who exactly is being bailed out when the Bank of England steps in? The answer is not clear cut. Is it pension policy holders? The economy at large that is spared a catastrophic financial crisis? Or is it BlackRock Inc., Legal & General Group Plc and Schroders Plc who manage LDI funds on behalf of pension clients? The very fact that we cannot give a confident answer to these questions, suggests that we are dealing with a system riven with conflicts of interest. And this poses the question of reform. Does it really make sense to perpetuate a system in which disastrous financial risks are built into the profit-driven provision of basic financial products like pensions and mortgages? Yes the central bank can act as the fire brigade, but why do we such a dangerous situation as normality. Why do the smoke detectors fail again and again? And why is the house not more fire proof? It is time to ask who benefits and who pays the cost for continuing with this dangerously inflammable system.

Amongst the costs this system imposes should be counted the sheer uncertainty it generates. As I hit send on this newsletter – the flight map tells me we are 35,000 feet up, somewhere over Azerbaijan – the CDS on Credit Suisse debt have surged to 2009 levels and the chief economist of the IIF is warning of dollar funding stress. None of us can know what the coming week has in store for us.

But before anyone starts wittering on about irreducible, metaphysical uncertainty, let us be clear. This is nothing of the sort. The hazards that we face in the global financial markets are entirely human-induced, macro-risks. They are the results of a contradictory, incoherent and hazardous profit-driven system, which the status quo underwrites.

****

I love writing this newsletter. It goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, there are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

To join the supporters club, click here:

September 30, 2022

Ones & Tooze: Britain’s Economic Freefall

The economic news from Britain could hardly be worse. In the weeks since Liz Truss became prime minister, the British pound has fallen to historic lows, financial markets lost $500 billion, and the IMF has issued warnings. Adam and Cameron explain what happened and where things go from here.

Also: India’s economy is surging but why hasn’t New Delhi been able to match Beijing’s economic success of the past few decades?

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

September 27, 2022

Chartbook #156 Project Fear 3.0 – or the gatekeepers and the Tories

As of this morning, sterling is hovering precariously above the historic lows it has plumbed in recent days. UK bonds continue under pressure. Meanwhile, the drumbeat of criticism goes on. Open the FT this morning and it reports that.

The IMF has launched a biting attack on the UK’s plan to implement £45bn of debt-funded tax cuts, urging the government to “re-evaluate” the plan and warning that the “untargeted” package threatens to stoke soaring inflation.

Janet Yellen, US Treasury secretary, said the US was “monitoring developments very closely”. S

Moody’s, the credit rating agency, offered critical commentary

Ray Dalio, the billionaire founder of hedge fund Bridgewater, said the UK was “operating like the government of an emerging country”.

Larry Summers, former US Treasury secretary, on Monday called the policy “utterly irresponsible”

Raphael Bostic, president of the Atlanta branch of the Federal Reserve, who this week warned that the UK’s plan increased economic uncertainty and raised the odds of a global recession.

Summarizing it all, Jason Furman, former economic adviser to Barack Obama, and a vigorous presence on Twitter wrote:

“I can’t remember a more uniformly negative reaction to any policy announcement by both economists and financial markets than the UK’s policy.”

What puzzles me about all these remarks, is not the criticism as such. Any reasonable person should regard a 45 billion pound tax give away for better-off Brits as a travesty. What I am curious about is how the critics of the UK government imagine themselves to be positioned in relation to Truss, Kwarteng and co.

It is one thing to write about your enemy with a view to diagnosing what their project might be. Trying to figure out what they are up to, is important for purposes of realism. What might be their plan? What should we expect next? That is the spirit of my Guardian piece.

The risk in this approach is that you over-interpret your enemy and ascribed to them too much intentionality. In the case of my Guardian article, the title, as usual overstates the point.

I am not sure that Kwarteng and team intended to produce a crisis that will supercharge their drive to slash public spending. But cutting government spending is clearly their plan. They have effectively said as much. And we should expect them to exploit the situation to pursue that goal and be braced for that.

The important point is that in diagnosing your enemy the point is not to correct their behavior. The point is to defeat them.

You are engaged not in a pedagogic exercise, but in reconnaissance. The point is to expose who they are and what they are up to. The point is to help those of us who are opposed to them to be clearer in our judgements and tactics.

It is quite a different thing to write about the Truss government and the mess it is making as though you imagine that your criticism will make a difference, as though the aim of the game is persuasion and improvement. What I wonder do all these highly esteemed sources of economic expertise imagine their exchanges with Downing Street to be about? Who do they think they are talking to? Who, in fact, would imagine sitting down with these people to talk at all? How could you keep a straight face?

This a government of Tory hardliners trying to define the third iteration of post-Brexit Tory identity – May, Johnson, Truss. This is a government that thinks nothing of putting the Northern Irish agreement in play. When they gave away 45 billion to those on top incomes, they were under no illusions. They knew what they were doing. They know it will increase inequality. No harm in that as far as Truss is concerned. Will this drive interest rates up? Of course it will. They appear to relish that too.

So what, given who Truss, Kwarteng et al are, what is the purpose of the drumbeat of opprobrium?

The most plausible reading is that it is a return to the agenda of Project Fear – the campaign of elite consensus-building and intimidation that helped to stop the Scottish independence bid in 2014, but failed miserably to cow the Brexiteers in 2016. The fire and brimstone that was promised in 2016 did not arrive. Perhaps now, six years on, the markets are delivering the long overdue punishment. As in 2016, negative remarks from the great and the good across the pond can’t hurt (though that is debateable in the British context).

But, if that is the objective, you have to ask yourself two things.

Will the intimidation actually work? Isn’t it, in fact, more than likely that Truss’s government will survive the shock, at least in the short run. The UK institutions of monetary and fiscal sovereignty, sterling’s residual status as a reserve currency, the high-functioning markets in gilts will see them through, once again. They are not actually a fragile EM on the edge of regime change. They do not have the constitutional and political issues of the eurozone or the redenomination risks that haunt Italy to deal with.

If you are expecting the markets to deliver the coup de grace and bring the Tories down in flames, I fear you will be disappointed once again. And crying wolf has a price. They may even emerge emboldened, as Johnson did from 2016.

Or, on the other hand, imagine that the intimidation does work. What if the Tories do turn tail and retreat from their policy and return to a more reasonable path. Who are you if you want that? The median British homeowner and voter?

The trade offs for the British population who will suffer the consequences of this policy are all too real. But to adopt this path of “least harm”, is profoundly unpolitical. It imagines that a Tory government, or any other government for that matter, is in the business of pursuing some utilitarian maximum and are open to persuasion about how best to do that. They clearly are not. So why would anyone who wants so see the back of this discredited mob, shed any tears over the fact that they seem bent on crashing the UK housing market? It will hurt, but is there any surer way to bring about their end?

It is a tough choice. Advocating catastrophe is a difficult position to be in. It does not come naturally to policy people who believe in solutions.

In any case, I fear that most of the commentary does not, in fact, seriously weigh this dilemma at all. That is because it is not, in fact, engaged in the fight for the future of the UK. It does not matter very much to Janet Yellen or Larry Summers, one way or another, whether Labour or the Tories rule in Britain. They have bigger fish to fry.

The most straight forward logic is the functional and crassly economistic logic invoked by Bostic. Market instability is bad. Why? Because instability cause uncertainty. Uncertainty is bad for global investment and if it is bad for investment it is bad for growth.

That is, indeed, a reason for central bankers, of the most unpolitical variety, to worry. The reassuring thing, presumably, is that the UK is not large enough to matter very much. Perhaps the UK situation will even serve a useful function in demonstrating to Meloni and her crew the risks of misbehaving.

Beyond this kind of truly economistic logic, what is at play is something that is not so much political as to do with hegemony – the struggle over the overarching ideas that govern and frame political choices. In this mode, what the critics of the UK are performing is the role of gatekeepers, a function, which is at the heart of elite economic policy discourse.

There are global norms of reasonable policy to uphold. Nowadays these include an overriding concern for inflation, but also a rather prim concern for inequality. Both those concerns rule out the kind of flagrant give-aways that Kwarteng and Truss are so openly indulging in. Seen in this light, Project Fear is best seen not so much as an actual act of intimidation as rather a ritualistic discourse through which the guardians of norms reassure themselves and the rest of the world of who is in charge, and what the rules are.

The commentators position themselves as physics teachers overseeing a public lesson in physics. There is gravity. The UK is defying that law. It will crash land. Regardless of the politics it is the laws of economics that need to be respected.

In fact, as recent UK history demonstrates all too clearly, the world of social and economic life is more malleable than that. It is not law-like in any simple sense, but shot through with contradictions, conflicts, double standards, hypocrisy, insanity and malice, all of which the gatekeeping and the gatekeepers with their tidy-minded logic help to obscure and, in so doing, to perpetuate.

To be trapped between hegemonic opprobrium and the deep-blue nightmare of the Tories is a horrible spot to be. Where is the alternative? Clearly the answer ought to be the Labour Party. But what have they chosen to do? Their answer to this moment of national crisis is to position themselves as the party of “sound money”, in other words as the best student in an introductory class in macroeconomics co-taught by the IMF, Janet Yellen and Larry Summers. The tactical temptation is obvious. What will be the strategic price they pay?

******

I love writing this newsletter. It goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, there are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

To join the supporters club, click here:

Chartbook #155 The UK, not keeping calm and how you can’t unburn toast.

I don’t normally write much about the UK – my relationship with the country and its politics will never recover from Brexit. But the current turmoil calls for an exception. Sterling’s collapse is of historic dimensions.

Source: FT

I did a short piece for the Guardian on trying to make sense of the crisis.

Like my comrade Daniela Gabor I fear this is headed towards austerity.

besides the obvious 'they're completely nuts' take, there is also the possibility that Truss mini-budget is a Trojan Horse for massive attack on the welfare state. https://t.co/U1IDMj29Ap

— Daniela Gabor (@DanielaGabor) September 26, 2022

In 2010 Greece served the Cameron administration as a boogyman. Now the Truss team has actually managed to manufacture something akin to a bond market crisis.

As the excellent Toby Nangle put it in the FT:

“Nothing in gilt markets in the past 35 years — not the UK’s ejection from the Exchange Rate Mechanism, 9/11, the financial crisis, Brexit, Covid or any Bank of England move — compares with the price moves in reaction to the chancellor’s mini-Budget”.

As bond markets sell off UK yields have accelerated past those for Greece and Italy.

The UK’s five-year bond yields are now above those of *Italy and Greece*.

— George Eaton (@georgeeaton) September 26, 2022

We are witnessing an almighty collision between ideology and reality. https://t.co/MZBWAudEvG pic.twitter.com/iSj93eCKCx

And it is the reaction pattern that is so disturbing. For the exchange rate to fall as yields rise ought to be a matter of real concern.

Rising yields usually boost a currency, so what's going on in the UK is unusual by G10 standards. It means yields are up due to a fiscal risk premium, which is what is weighing on the Pound. Last time this happened was for Italy in 2011/12, when rising BTP yields weighed on Euro. pic.twitter.com/pZZDYrUHDY

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) September 26, 2022

Now, if the UK were actually a well-run emerging market, rather than an atrociously governed advanced economy, it would have foreign exchange reserves, which the Bank of England in extremis could use to stabilized the exchange rate – admittedly a freaky scenario. But, of course, advanced economies like the UK don’t hold substantial reserves.

1974: 10bln reserves for 28 bln annual imports (4 months)

— steve_wen

2022: 80bln reserves for 654 bln annual imports (1.5 months) pic.twitter.com/4UEWteCMP9(@Swen_2017) September 26, 2022

So some normally sober voices have even discussed the possibility of opening Fed swap lines.

In trying to make sense of what on earth the tories are up to, you end up having to read conservative commentators. This substack by Ryan Bourne @MrRBourne is extremely useful. h/t @duncanweldon

What Bourne’s analysis reveals is that while Truss and Kwarteng see a positive role for supply-side reform and tax cuts and assign the Bank of England the task of keeping inflation in check – the Reaganite policy-assignment. They have no positive vision for the role of public expenditure. So it becomes the residual that must be cut to meet the budgetary constraint. This is the key reversal of the policy consensus since the 1990s.

As a guide to the Tory mind, I have also found the blow by blow commentary by @KateAndrs at the Spectator useful

I’ll admit that it was surprise to discover that Kwarteng has a PhD from Cambridge in economic history. This write up of his work by George Parker in Liverpool and Chris Cook was really interesting.

Some of the economic problems facing Kwarteng, however, are ones he has been considering for some time. His doctoral thesis, titled “Political Thought of the Recoinage Crisis”, is a survey of commentary from the late 17th century around the government of William III’s decision to reissue England’s coinage in 1695-6. Modern concerns over the rising cost of coffee echo the views of Sir Isaac Newton, who then held leading roles at the Royal Mint. Kwarteng cited him noting that a devaluation-induced rise in commodity prices was “Equipollent [equivalent] to a tax upon all other Estates” and tended “to make the Nation weary of the War, and uneasy under the Government”. Recommended Martin Wolf Kwarteng is risking serious economic instability The historical context of Kwarteng’s analysis makes it hard to draw many conclusions about his current views: one of the critical monetary problems at the time was people melting down, shaving or exporting coins for their silver. He certainly does not seem to endorse the position of pamphleteers he cites who feared the monetary monopoly of the then new BoE would cause another civil war. But the thesis does show how comments from his allies over the weekend blaming speculation by “City boys” for the weakness of sterling have a long heritage. Kwarteng notes that, even then, at the very start of London’s financial revolution: “None believed that the interest of the goldsmith and banker was anything but inimical to the wider good of the nation”.

Kwarteng is also the author of an epic history of money and power, in which he reveals his deep unease with fiat money.

Daniel Drezner summarized the plot in the New York Times. For Kwarteng

The history of money is one of oscillation between “periods of monetary chaos,” when governments issue fiat currency, and “periods of relative order,” when currencies are linked to gold. The bulk of “War and Gold” is devoted to observing that things seemed much, much better during eras when currencies were tied to gold. In his introduction, Kwarteng explicitly says he is not advocating a return to the pre-1914 gold standard. Rather than echoing Rand Paul, Kwarteng writes more like a Tory nostalgic for the solidity of Robert Peel in 19th-century England or the Eisenhower era in 20th-century America.

This is a dramatic vista no doubt. Meanwhile, in the autumn of 2022, the UK under Kwarteng as Chancellor now faces the prospect of a recession ahead. The main question is how severe that recession might be.

Critical to this will be the housing market. Real estate prices in the UK are chronically overinflated and this is the flywheel on middle-class and upper class wealth. Practically all mortgages in the UK have adjustable rates with fixed-rate being offered for at most 2-5 years. So the huge hike in interest rates is going to feed through to households in a dramatic way.

Estimated number of mortgages reaching end of fixed rate period by initial fixed rate

— Neal Hudson (@resi_analyst) September 26, 2022

– lots of caveats but suggests around 300,000 per quarter at the moment, peaking at around 375,000 in Q2 next year pic.twitter.com/rUjzEAp9ET

The shock to UK households will be huge.

If mortgage rates rise to 6%—as implied by markets’ current expectations for Bank Rate—the average household refinancing a 2yr fixed rate mortgage in the first half of 2023 will see *monthly* repayments jump to £1,490, from £863. Many simply won’t be able to afford this (1/2) pic.twitter.com/hkoZCcSfjJ

— Samuel Tombs (@samueltombs) September 26, 2022

For a country that has long been lingering in a painful stagnation, it is a grim prospect indeed.

As Martin Wolf pointed out in a powerful critique of the Truss program, what the UK desperately needs is an increase in investment. The kind of drama unleashed in recent weeks in no way helps.

The UK will no doubt get over this shock. But the damage is done. As Toby Nangle puts it, in terms that could hardly be more English, “You can’t unburn toast.”

If all these moves magically reverses over the next few days (ahem) they are STILL going have serious effects on stress tests for years and years to come.

— Toby Nangle (@toby_n) September 26, 2022

Your 'stress scenario' of +150bps over 3mths may have looked reasonable. No longer.

You can't unburn toast.

****

I love putting out the newsletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, there are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

What is Kwasi Kwarteng really up to? One answer: this is a reckless gamble to shrink the state

Markets have delivered a devastating judgment on Kwasi Kwarteng’s tax-cutting mini-budget. The pound has collapsed to historic lows. And investors have sold UK government debt, driving the price of bonds down and the effective interest upwards at a rate not seen since the currency crises of the 1950s. The combination of the two is particularly worrying because it signals what some fear could become a comprehensive loss of confidence in the pound and UK assets.

You might ask how it could be otherwise. How did the government expect the markets to react when it followed a giant energy crisis-fighting package, roughly costed at £150bn, with a further £45bn in tax cuts that primarily benefit the rich? It also delivered this news at a time when inflation is running faster than at any point since the 1970s and flouted the need for vetting by the Office for Budget Responsibility. What did it expect?

Astonishingly, in the bubble of Downing Street, the answer seems to have been applause. Apologists for Liz Truss and Kwarteng insist that they are embarking on a new era of supply-side reform, in which taxes are set with a view to incentivising entrepreneurship and reviving the growth rate. If this contributes to inflationary pressure in the short term, it is the job of the Bank of England to counter that with higher interest rates.

Read the full article at The Guardian

Slouching Towards Utopia by J Bradford DeLong — fuelling America’s global dream

An economic history of the last century recalls a period that improved and redefined the lives of billions — yet also enabled war and environmental destruction

Read the full article at Financial Times

September 23, 2022

Chartbook #154 Who is going to vote for Italy’s right-wing coalition?

Many of us had hoped that it would not come to this.

In Sunday’s elections in Italy, triggered by the premature fall of Mario Draghi’s government, the right-wing coalition of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, Matteo Salvini’s Lega and Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli D’Italia, seem set to score a decisive victory. The center-left party PD is not polling badly. It will likely come in second in terms of share of the vote. But without an effective coalition, it is doomed to defeat.

Leading in the polls by a decisive margin are the Fratelli d’Italia, who emerged as champions of the hard-right from the fall of Berlusconi’s last government in the midst of the Eurozone crisis. Founded in December 2012, the Fratelli reconstitute what was once the neo-fascist movement. This traces its origins to the MSI, established in 1946 by survivors of Mussolini’s Salo Republic. In 2018 the Fratelli scored just 4.4 percent of the national vote. On Sunday they may well score six times that share. In the autumn of 2022, a hundred years on from the fascist seizure of power, Italy’s first woman Prime Minister is likely to be Giorgia Meloni, who in her youth hailed Mussolini as a great leader .

Compared to 2018 it seems that the Fratellli will gain their success largely by bleeding the electorates of the other conservative parties. According to the polls, they will likely take 44 percent of the vote cast for the Lega in 2018 and 38 percent of the Forza Italia vote. They will take a far smaller share from 5Star.

Source: Cluster17

5Star is bleeding voters in every direction, to the Fratelli but also to the PD.

Clearly, for many of us, the prospect of Meloni’s victory is a distressing one and it begs the question of who is voting for this party and why the center-left seems set to do so badly.

Recording the latest Ones and Tooze podcast on the upcoming Italian election, I realized that though there was plenty of analysis of the history of the Italian far-right and the figure of Giorgia Meloni, I had not seen any polling data in the English-language media showing us who was expected to vote for them, or any of the other contenders.

It is all very well to have the overall polling numbers, but to get a sense of what is actually motivating electoral currents you want to know how men and women of different ages in different parts of the country with different occupations, education and income level are going to vote.

Drawing a blank in the English-language media I put out a call on twitter and got a series of extremely useful replies from twitter friends. Thank you in particular to @tommsabb @ericvautier @jtbrowe @FulvioLorefice & @antoniofocella

****

A set of data from Corriera Della Sera paint the basic picture.

There are slight differences between women and men in party preference, with women slightly preferring the older parties of the right i.e. the Lega and Forza Italia. Men slightly prefer the PD and the Fratelli. But the big difference on gender lines is that a far larger share of women declare themselves undecided or uncertain about whether they will vote at all.

With regard to age it is striking that it is the center-left PD that does relatively well with the youngest voters. The PD also scores particularly well with those over 65, voters whose preferences were shaped before the break of 1992, when the Cold War party system collapsed. The prospective votes for 5Star are heavily weighted towards the youth vote. By contrast, Fratelli d’Italia does relatively poorly with both younger and older voters and concentrates its support amongst the middle-aged. This tendency is even more pronounced for the Lega.

On the educational axis a pattern emerges that is visible in many modern democracies and has been highlighted by Thomas Piketty. Amongst those with University degrees the center-Left PD will likely score more votes than the Fratelli and the Lega put together. Liberal progressive politics has become the domain above all of better educated Italian voters. The Fratelli achieve relatively similar support across all educational levels whereas the Lega sees a clear bias towards the lowest levels of qualification.

And this is confirmed when we look at occupational data. The center-left PD does best with the liberal professions, white-collar workers and teachers. It does badly with workers and the unemployed. The Lega vote is heavily tilted towards workers, whereas 5Star scores highly amongst the unemployed. What brings the Fratelli their likely success is that they do relatively well across all occupations, scoring poorly only amongst students.

The social analysis group Cluster17 offers a slightly different breakdown of occupations, which highlights in even more stark form, the differences suggested by the Corriere data.

Source: Cluster17

According to Cluster17 the center left will score a miserable 9 percent amongst workers as against 29 percent amongst retirees and 34 percent amongst managerial and professional voters. The Lega reverses this pattern, scoring twice as well amongst workers as amongst the electorate at large. But it will be the Fratelli that will score the largest share of Italian working-class votes. Since workers make up 30 percent of the electorate this pattern strongly favors the right-wing coalition. All told the three-party right-wing coalition will likely capture 58 percent of Italian workers’s votes this year.

The pattern implied by the occupational data is strongly confirmed by data regarding income. Support for the center-left PD increases monotonously with income. Those on over 5000 euros per month are almost three times as likely to vote for the PD as those on under 1000. The reverse is true for 5Star. 5Star will likely take 28 percent of the lowest income group, twice its overall vote share. The Lega’s vote is strongest in the 1000-1500 bracket. Once again, the Fratelli stand out for the fact that their vote share varies relatively little across income classes.

Source: Cluster17

So, apart from not attracting the votes of students and pensioners, the occupational and income data do not really give us a clear view of the far-right Fratelli voters. Meloni who is herself from a working-class background and a tough suburb of Rome will do well with working-class voters, but that does not mean that she will do particularly badly with other social groups.

So what does motivate those who will cast their vote for the Fratelli? The answer is to be found most clearly on the side of culture and beliefs.

One fundamental divide within the Italian electorate is drawn on grounds of religion.

Source: Cluster17

Italy is a society in which a quarter define themselves as non-believers. 20 percent are practicing Catholics. And half identify with Catholicism but do not practice.

The Center-left scores by far the best amongst those who describe themselves as non-believers. 5 Star, likewise, does relatively well with non-believers (27 percent of the total). The Lega and Berlusconi’s Forza D’Italia do far better with practicing Catholics than with any other group. The Fratelli does best with those who declare themselves to be religious but are not practicing, which is also the largest segment of Italian society – 52 percent. Conversely, three of the right-wing coalition parties scores very poorly amongst the non-believers.

To dig deeper, Cluster17 divides the Italian population into a series of socio-cultural segments.

Source: Le Grand Continent

These groupings are defined by three different cleavages:

(1) Pro-migrant, pro-EU and anti-authoritarian v. voters who are anti-migrant, eurosceptic and authoritarian in cultural attitudes.

(2) Voters who favor or oppose redistribution between classes and between North and Southern Italy.

(3) Religious v. secular.

One can distinguish the different cluster of social and cultural attitudes by asking a series of questions, such as for instance: Should illegal immigrants be banned from access to Italian hospitals? This is a view that is popular with authoritarians and identitarians and opposed by progressive-radicals, but also by social catholics and social democrats.

Source: Le Grand Continent

What emerges from this elaborate exercise is an image of the kinds of social and cultural milieu which give their support to each of the Italian parties.

Source: Le Grand Continent

The upshot of this analysis it that the relative weakness of the left is due to the fact that it only appeals strongly to three social-cultural clusters: progressive-radicals, social democrats and social-christians. These groups tend to be older or younger, under-representing middle aged groups. They tend to be highly educated. The three bases of support for the PD are united in their opposition to identitarian policies, but are split on religion. The PD’s opposition to radical reform makes it difficult for them to capture any of the popular vote that is opposed to the identitarian politics of the right, but is attracted by the anti-systemic message offered by 5Star.

The strength of the Fratelli, by contrast, lies in their ability to mobilize support from 5 distinct conservative clusters ranging from moderate conservatives to identitarians and authoritarians (whose vote the Fratelli split with the Lega). Strikingly where the Fratelli score most strongly are not with modern radicals of the right, but with traditionalist. They also score heavily with anti-welfarists (anti-assistanat).

The upshot of this analysis is that the surge in support for the Fratelli does not mark a break with the pattern that was already established in 2018. The basic rearrangement of social identity and voting was already established in the decades since the end of the Cold War. By 2018 Italian workers had drifted into the right-wing camp. What Meloni has done is to take votes above all from her right-wing rivals and to bind together a wide range of right-wing and conservative opinion in a camp that refused any compromise with Draghi’s cross-party government. 5Star still takes a lot of the lower-income and youth vote that might otherwise be available to the left. That leaves the PD as a predominantly upper-middle class party that represents the educated and higher-income classes but has no chance of building a viable majority.

****

I love putting out the newsletter for free to thousands of readers around the world. But what sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, press this button and pick one of the three options.

Several times per week, paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

There are three subscription models:

The annual subscription: $50 annuallyThe standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly – which gives you a bit more flexibility.Founders club:$ 120 annually, or another amount at your discretion – for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions, please consider signing up for the Founders Club.Several times per week, as a thank you, all paying subscribers to the Newsletter receive the full Top Links email with great links, reading and images.

Ones & Tooze: Is Italy on the Verge of Returning to Fascism?

In today’s episode hosts Cameron Abadi and Adam Tooze preview the upcoming Italian election and the rise of Giorgia Meloni. Her party, Brothers of Italy, is leading in the polls and has a lineage that connects it directly to former Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini. They also examine the current appeal of far-right rhetoric in Italy and the long term implications a Meloni government would have on the country’s economy.

In the second segment the two dissect the economic history of Australia, from its beginnings as British penal colony to its more recent decades-long run of positive growth.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

September 16, 2022

Ones & Tooze: Can Ukraine Win the War Yet Lose Their Economy?

In this episode hosts Cameron Abadi and Adam Tooze take a look at how Ukraine’s war against Russia is straining the country’s finances and the increasing pressure the US and EU will face to save the country from financial collapse. In the second segment, in the wake of the passing of Queen Elizabeth II, the two examine the UK’s financial relationship with its monarchy and how it’s evolved over the centuries.

Find more episodes and subscribe at Foreign Policy

September 12, 2022

Chartbook #150: Why “cheap Russian gas” was a strategic snare but not the secret to German export success.

Right now German grand strategy is in the crosshairs of criticism. Germany is faulted for having appeased Putin. It is faulted for having neglected the Bundeswehr and on top of that, the Federal Republic is facing an energy crisis like none other in its history. Gas deliveries from Russia have been severely curtailed if not halted altogether, exposing the dependence of German energy consumers – both households and industry – on pipelined gas from the East. Critics of German strategy point out that the risks of dependence on Putin should have been obvious at least since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. And despite that, the share of Russian gas in German consumption continued to increase not decrease. At the same time, Germany phased out its nuclear reactors and failed to accelerate the energy transition, leaving itself even more vulnerable.

As the cold weather of the autumn and winter approaches, Berlin faces not just an acute functional problem, but something akin to a legitimation crisis, a situation which I analyse at some length in the speech I was honored to give in memory of Willy Brandt in Berlin last week.

The video (in German) is here:

It is easy, and not just with hindsight, to find fault with German strategy in recent years – (whether Germany’s failings are really more egregious than those of neighbors like France and the UK, is a matter for another post). But if you really want to land a knock out blow on the German success story you do not simply argue that they got things wrong with Nord Stream 2. You argue that the entire image of German economic success that has overshadowed Europe in the last twenty years, is a mirage sustained by reliance on cheap Russian gas.

If the recent success of Germany Inc and the social market economy that rests on it, are, in fact, owed to naive deals with Putin, it would force us to rewrite the history of Europe in the last quarter century.

The idea that cheap Russian gas is the secret sauce behind German export success circulates widely in forums like twitter often in explicitly anti-German form. It can also be found in casual throwaway lines, such as the comment by Zoltan Pozsar quoted recently by Rana Foroohar of the FT.

“war means industry”, be it hot war or economic war, and growing industry means inflation. This is the exact opposite of the paradigm we’ve experienced for the last half century, during which “China got very rich making cheap stuff . . . Russia got very rich selling cheap gas to Europe, and Germany got very rich selling expensive stuff produced with cheap gas.”

Schadenfreude aside, there is an obvious appeal to such a narrative. Hubris gets its comeuppance. The unctuous narrative of German superiority through hard work, clean government and frugal living, is turned on its head.

But, is it true? When you start digging, it is striking how little evidence is offered for the “cheap Russian gas” thesis. Of course, high gas prices are currently crushing German businesses and BASF is screaming that the survival of the chemical industry in Germany is in question. Talk of deindustrialization stalks the land.

But it shouldn’t be surprising that BASF is talking its book. And the fact that a historic spike in energy prices causes problems for energy-intensive industries in Germany does not prove that low energy costs obtained by backroom deals with the Kremlin are responsible for the existence of the industry in the first place, or its competitive success in recent year. The influence of the industry and its short-sighted cost-cutting no doubt helped to create an infrastructural dependency, but that tells us little or nothing about sources of competitive advantage before 2022.

As Daniel Gros pointed out in August, if cheap gas from Russia had been a major factor in Germany’s recent economic development you would expect the country to have a high level of gas-intensity in GDP. The opposite is the case. Germany’s gas-intensity of economic activity is about half the global average.

It is less surprising to find that the German economy was quite efficient in its use of gas when you realize that since 2008 gas costs in Germany have been far above those in the US and marginally above the European average. Thank you to André Kühnlenz for this handy graphic.

The long-term view might also be very interesting. For years (2006 to 2013 after Schröder), Germany even had a higher natural gas price than the European market price… pic.twitter.com/wwm8hOzS1N

— André Kühnlenz (@KeineWunder) September 12, 2022

You can pull the European data from Eurostat here.

It is true that German gas prices are “cheap” compared to what businesses pay in Japan, where all gas has to be imported in the form of LNG. But compared to the bonanza in the United States, German gas prices have never been anything other than expensive.

Admittedly, the aggregate data compiled by Eurostat will not capture the kind of premium deal that a customer like BASF can command from its favored collaborator GAZPROM. So, let us allow that German industry may on average achieve somewhat better prices than the European average, how much difference could this possibly make to the competitive position of its exporters?

First of all let us remind ourselves of the structure of German exports.

Unsurprisingly, German comparative advantage is not generally in sectors where cost is the dominant factor. But, cost is always one element in a deal. However high the quality of German goods, the price matters. So, how big an issue are energy costs for Germany’s industries, not in an extreme year when gas prices have gone through the roof, but in the normal times before 2020 when Germany racked up its triumphs as the export champion of the world?

Figures for energy intensity are very revealing.

Source: VCI

For German manufacturing industry as a whole, energy costs amounted to 5.8 percent of gross value added. In the leading export sectors like motor vehicles and engineering the share was 3 percent. Though gas and electricity are indispensable and you cannot operate industrial processes without them, like other essential inputs such as protein and calories, greater and greater efficiency mean that energy accounts for a small and diminishing share of industrial costs.

Nonferrous metals was the most energy-intensive sector in Germany. It accounted for about 6 percent of exports. Chemicals, where energy costs accounted for 14-19 percent of gross value added, was responsible for roughly 10 percent of exports.

Obviously, with current energy prices at their shocking levels, both those sectors, along with the paper industry are under intense pressure. The situation of the chemicals industry, where gas is used not only for energy production but also as a feedstock, is particularly difficult. But in more normal times, even if we allow that Germany benefited from discounts on Russian gas, how much difference is that likely to have made to sectoral competitiveness on global markets, let alone German industrial export performance overall. What are in play are at most a few percentage points of value added.

Interestingly, in 2015 the well-respected Frauenhofer Institute did a series of in-depth studies on the sensitivity of production and employment in German industry to energy prices. At the time the question that concerned them was the impact of removing the privileges provided to export-exposed industrial companies in Germany’s electricity pricing system. This is interesting not because it directly addresses the question of Russian gas, but because it allows us to gauge the amount of support provided to Germany’s most favored industrial sectors by exemption from electricity levies. The result of the Frauenhofer study was surprising mainly because the estimated impact was so small. All told the economists suggested that raising industrial electricity prices to the level paid by household and small businesses might cost 4 billion in exports and 15,000-45,000 jobs, of which at most 35,000 would be in manufacturing industry. In light of that fully worked out macroeconomic assessment, how large would we expect the effect of a putative “cheap Russian gas”-subsidy to be.

Taking energy costs as a whole in relation to gross value added across the entire economy, Germany before the crisis was certainly in a somewhat favorable position relative to its European neighbors, but by no means in a league of its own. And it enjoyed that position not because of lower energy costs but because of greater efficiency in the use of energy.

Try one last thought experiment. In light of the chart above, do low energy costs help explain the success of UK manufacturing in recent years? Or, if you prefer the comparison, does Italy’s heavy reliance on Russian gas, second only to that of Germany, explain the performance of its exports since the early 2000s? Neither question suggests a plausible narrative and we should avoid drawing simplistic conclusions in the German case as well.

In the genre of Fin-fiction, the story of German exporters suffering their comeuppance at the hands of bad king Putin, is more a morality tale than convincing economic analysis.

German energy policy has been a disaster. There is no reason to pile on with exaggerated claims about the economic significance of cheap Russian energy imports.

This thread by Miłosz Wiatrowski-Bujacz makes the point very well:

As @adam_tooze points out, we are repeatedly confronted with the narrative about how “DE owes its economic success to cheap RU gas”. It’s an intuitively attractive one (I myself uttered these words on several occasions), but it (partly) collapses under closer scrutiny – thread

— Miłosz Wiatrowski-Bujacz (@wmilosz) September 12, 2022https://t.co/NLx8GPoQqs

Adam Tooze's Blog

- Adam Tooze's profile

- 767 followers