Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 156

January 26, 2014

Liability, Disclaimers, and Adverse Selection, by Bryan Caplan

Suppose the law says that parking garages are liable for whatever damages occur on the premises. However, there's a big loophole: Garages can disclaim liability by posting a big "ENTER AT YOUR OWN RISK" sign. What happens?

Non-economists usually conclude that every parking garage will post the sign to save money. But if you remember the economics of adverse selection, this is a puzzling conclusion. After all, which garages will be most eager to disclaim? The garages that do a terrible job of protecting their customers' property. So what should customers conclude about the first garage that avails itself of its right to disclaim? That the firm is a "lemon" so they should park their cars elsewhere. If firms anticipate this inference, even high-risk garages have a clear incentive not to disclaim.

In the real world, of course, we see firms disclaiming liability all the time. Why on earth would they do so despite adverse selection?

One possibility is that customers systematically underestimate the risk of damage, but firms don't. This is surely true in some cases, but it contradicts a vast literature on the psychology of risk showing that people often overestimate risks.

The better explanation is that real-world liability systems are incredibly inefficient. Suppose the typical lawsuit costs the defendant $100,000 but only enriches the plaintiff by $10,000. With a .1% accident risk, a firm's expected liability is $100, but a customer's expected damages are only $10. A firm that disclaimed liability and cut the price of parking by $30 would make customers $20 richer and itself $70 richer.

What about the adverse selection problem? The more inefficient the legal system, the easier adverse selection is to solve. Suppose that in the preceding example, the first firm to waive liability has double the normal risk. Waiving liability would alert customers to this unpleasant fact. But as long as the the firm cuts the price of parking by more than the customer's expected $20 damages, disclaimers enrich both sides.

Regulators are usually loathe to allow disclaimers. Imagine how the U.S. government would react if an employer bypassed worker safety and discrimination laws with a "WORK AT YOUR OWN RISK" sign at the employee's entrance. If pressed to justify their reluctance, regulators would probably respond, "Disclaimers would effectively gut the law." They're probably right. The upshot, though, is that the laws regulators are so eager to preserve are absurdly wasteful. If virtually every firm disclaims despite the adverse selection problem, the liability regime must be very inefficient indeed.

(1 COMMENTS)

Non-economists usually conclude that every parking garage will post the sign to save money. But if you remember the economics of adverse selection, this is a puzzling conclusion. After all, which garages will be most eager to disclaim? The garages that do a terrible job of protecting their customers' property. So what should customers conclude about the first garage that avails itself of its right to disclaim? That the firm is a "lemon" so they should park their cars elsewhere. If firms anticipate this inference, even high-risk garages have a clear incentive not to disclaim.

In the real world, of course, we see firms disclaiming liability all the time. Why on earth would they do so despite adverse selection?

One possibility is that customers systematically underestimate the risk of damage, but firms don't. This is surely true in some cases, but it contradicts a vast literature on the psychology of risk showing that people often overestimate risks.

The better explanation is that real-world liability systems are incredibly inefficient. Suppose the typical lawsuit costs the defendant $100,000 but only enriches the plaintiff by $10,000. With a .1% accident risk, a firm's expected liability is $100, but a customer's expected damages are only $10. A firm that disclaimed liability and cut the price of parking by $30 would make customers $20 richer and itself $70 richer.

What about the adverse selection problem? The more inefficient the legal system, the easier adverse selection is to solve. Suppose that in the preceding example, the first firm to waive liability has double the normal risk. Waiving liability would alert customers to this unpleasant fact. But as long as the the firm cuts the price of parking by more than the customer's expected $20 damages, disclaimers enrich both sides.

Regulators are usually loathe to allow disclaimers. Imagine how the U.S. government would react if an employer bypassed worker safety and discrimination laws with a "WORK AT YOUR OWN RISK" sign at the employee's entrance. If pressed to justify their reluctance, regulators would probably respond, "Disclaimers would effectively gut the law." They're probably right. The upshot, though, is that the laws regulators are so eager to preserve are absurdly wasteful. If virtually every firm disclaims despite the adverse selection problem, the liability regime must be very inefficient indeed.

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on January 26, 2014 21:09

January 25, 2014

Schooling Ain't Learning, But It Is Money, by Bryan Caplan

Lant Pritchett is enjoying justified praise for his new

The Rebirth of Education: Schooling Ain't Learning

. His central thesis: schooling has exploded in the Third World, but literacy and numeracy remain wretched.

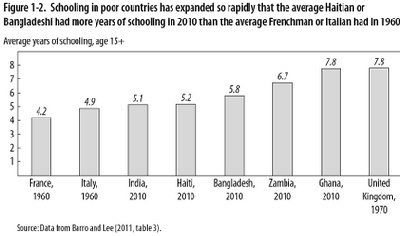

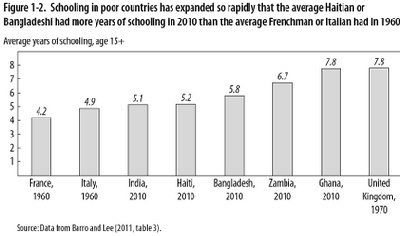

The average Haitian and Bangladeshi today have more schooling than the average Frenchman or Italian in 1960:

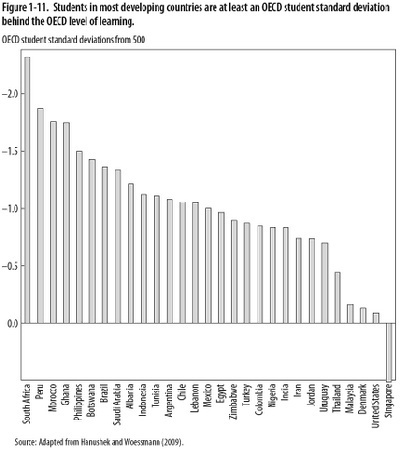

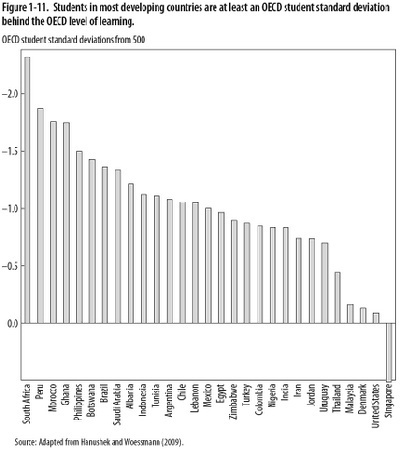

On international literacy and numeracy tests, however, the average student in the developing world still scores far below the average student in the developed world. Gaps of one standard deviation plus are typical:

Solid work. But there's an amazing fact that Pritchett largely ignores in this book. Despite the woeful failure of Third World schools to teach basic skills, Third World employers still greatly value educational attainment. In fact, credentials pay more in the developing world than they pay in the developed world! Psacharopoulos and Patrinos provide a thorough survey of the evidence. Quick (and conservative!) estimates say that the education premium averages 10.9% in low-income countries versus just 7.4% in high-income countries:

Pritchett's omission is striking because he's also famous for pointing out and trying to explain the fact that education is much more lucrative for individuals than nations. His leading explanations are (a) rent-seeking, and (b) signaling. My postcard version:

How does the signaling model better fit the facts? Simple. Although Third World schools fails to teach literacy and numeracy, they still rank students. Indeed, Pritchett emphasizes that one of the main problems with international test scores is that weaker students tend to drop out sooner, creating an illusion of learning in the data. What Pritchett doesn't emphasize, though, is that employers can profit from this selection attrition by preferring more educated workers. Signaling!

Prtichett earnestly wants to bring literacy and numeracy to the world's poor. It's a worthy aim. But his evidence teaches us much deeper and more general lessons about the economics of education. Once you grasp how little its schools teach and how much employers pay, the signaling story is hard to escape for the Third World. And if signaling matters enormously there, shouldn't we expect it to matter enormously everywhere?

(1 COMMENTS)

The average Haitian and Bangladeshi today have more schooling than the average Frenchman or Italian in 1960:

On international literacy and numeracy tests, however, the average student in the developing world still scores far below the average student in the developed world. Gaps of one standard deviation plus are typical:

Solid work. But there's an amazing fact that Pritchett largely ignores in this book. Despite the woeful failure of Third World schools to teach basic skills, Third World employers still greatly value educational attainment. In fact, credentials pay more in the developing world than they pay in the developed world! Psacharopoulos and Patrinos provide a thorough survey of the evidence. Quick (and conservative!) estimates say that the education premium averages 10.9% in low-income countries versus just 7.4% in high-income countries:

Pritchett's omission is striking because he's also famous for pointing out and trying to explain the fact that education is much more lucrative for individuals than nations. His leading explanations are (a) rent-seeking, and (b) signaling. My postcard version:

1. The rent-seeking story: Education successfully teaches socially wasteful job skills.Pritchett's latest evidence heavily tips the scales against rent-seeking. The rent-seeking story posits that Third World schools are teaching students to cleverly manipulate a corrupt, zero-sum political system. The reality, though, is that Third World schools don't even teach students how to read, write, add, or subtract - much less file a legal brief or sue a competitor.

2.

The signaling story: While education teaches few useful job skills,

strong academic performance convinces the labor market that you've got

the Right Stuff.

How does the signaling model better fit the facts? Simple. Although Third World schools fails to teach literacy and numeracy, they still rank students. Indeed, Pritchett emphasizes that one of the main problems with international test scores is that weaker students tend to drop out sooner, creating an illusion of learning in the data. What Pritchett doesn't emphasize, though, is that employers can profit from this selection attrition by preferring more educated workers. Signaling!

Prtichett earnestly wants to bring literacy and numeracy to the world's poor. It's a worthy aim. But his evidence teaches us much deeper and more general lessons about the economics of education. Once you grasp how little its schools teach and how much employers pay, the signaling story is hard to escape for the Third World. And if signaling matters enormously there, shouldn't we expect it to matter enormously everywhere?

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on January 25, 2014 21:12

January 23, 2014

Predicting the Popularity of Obvious Methods, by Bryan Caplan

Imagine a Question in social science.

The Question can be analyzed using an Obvious Method - a simple, standard approach that social scientists have used for decades.

The Question has a Welcome Answer - an answer that the typical social scientist wants to hear.

What determines the popularity of the Obvious Method?

Here's my simple cynical theory:

1. If the Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Obvious Method will be popular.

2. If the Obvious Method fails to yield the Welcome Answer, the Obvious Method will be unpopular.

If #2 holds, then:

3. If a Non-Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Non-Obvious Method will be popular.

4. If no Non-Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Question will be unpopular.

My model clearly doesn't explain everything. Some academics really do love methodological sophistication for its own sake. But I still think my model explains a lot of question-by-question variation in researchers' methodological finickiness.

Do you see what I see? Please offer disconfirming as well as confirming examples.

(1 COMMENTS)

The Question can be analyzed using an Obvious Method - a simple, standard approach that social scientists have used for decades.

The Question has a Welcome Answer - an answer that the typical social scientist wants to hear.

What determines the popularity of the Obvious Method?

Here's my simple cynical theory:

1. If the Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Obvious Method will be popular.

2. If the Obvious Method fails to yield the Welcome Answer, the Obvious Method will be unpopular.

If #2 holds, then:

3. If a Non-Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Non-Obvious Method will be popular.

4. If no Non-Obvious Method yields the Welcome Answer, the Question will be unpopular.

My model clearly doesn't explain everything. Some academics really do love methodological sophistication for its own sake. But I still think my model explains a lot of question-by-question variation in researchers' methodological finickiness.

Do you see what I see? Please offer disconfirming as well as confirming examples.

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on January 23, 2014 21:11

Mandela and Communist Villainy, by Bryan Caplan

Bill Keller in the NYT:

Are we really supposed to believe that Mandela didn't know about these bloodbaths? If he somehow managed to remain oblivious for decades, he'd be a fool, not a hero.

If Mandela had merely allied with the South African Communist Party - as he repeatedly lied - you could say, "His actions were no worse than the U.S. wartime alliance with the Soviet Union." But he wasn't a Communist ally. He was a member of the SACP's Central Committee.

But isn't it great that Mandela didn't act like a Communist once he gained power? Sure. Yet that doesn't make him a "hero" any more than Deng Xiaoping. Utterly villainous systems are often reformed by moderately villainous people. We should be thankful for these reformist villains. But that's no reason to forget what they really are.

(14 COMMENTS)

But Mandela's Communist affiliation is not just a bit of history'sI'm puzzled. How can a "hero" join a movement that murdered millions of innocents? How can a "hero" remain in a movement that continued to murder millions of innocents? Because that is precisely what Mandela did. At the time Mandela joined, the Soviet Union, Soviet satellites, and Maoist China had already murdered tens of millions via execution, terror-famine, and draconian slave labor camps. After Mandela joined, Communist movements around the world continued this villainous tradition, and Maoist China took it to new heights.

flotsam. It doesn't justify the gleeful red baiting, and it certainly

does not diminish a heroic legacy, but it is significant in a few

respects.

Are we really supposed to believe that Mandela didn't know about these bloodbaths? If he somehow managed to remain oblivious for decades, he'd be a fool, not a hero.

If Mandela had merely allied with the South African Communist Party - as he repeatedly lied - you could say, "His actions were no worse than the U.S. wartime alliance with the Soviet Union." But he wasn't a Communist ally. He was a member of the SACP's Central Committee.

But isn't it great that Mandela didn't act like a Communist once he gained power? Sure. Yet that doesn't make him a "hero" any more than Deng Xiaoping. Utterly villainous systems are often reformed by moderately villainous people. We should be thankful for these reformist villains. But that's no reason to forget what they really are.

(14 COMMENTS)

Published on January 23, 2014 10:19

January 22, 2014

Correction on Mandela, by Bryan Caplan

Yesterday, I wrote:

To be fair, if I were a Communist, I would probably maintain that Mandela wasn't a "real" Communist. Real Communists feign democratic credentials to gain power, then rush to take over the interior ministry and the military, ban the opposition, and impose totalitarianism. Still, the fact remains that Mandela was not merely allied with the SACP; he was a member of its central committee. And he lied about it, making him a bona fide crypto-Communist.

My bad.

(2 COMMENTS)

While I'm convinced that Mandela was never a Communist, his priorities were thoroughly Leninist: "The point of the uprising is the seizure of power; afterwards we will see what we can do with it."Today, however, I've learned that multiple reputable sources, including the South African Communist Party and the African National Congress itself, recently confirmed that Mandela was indeed a Communist. His Long Walk to Freedom was deliberately falsified to hide this truth.

To be fair, if I were a Communist, I would probably maintain that Mandela wasn't a "real" Communist. Real Communists feign democratic credentials to gain power, then rush to take over the interior ministry and the military, ban the opposition, and impose totalitarianism. Still, the fact remains that Mandela was not merely allied with the SACP; he was a member of its central committee. And he lied about it, making him a bona fide crypto-Communist.

My bad.

(2 COMMENTS)

Published on January 22, 2014 21:06

January 21, 2014

Mandela: Reckless But Lucky, by Bryan Caplan

I've heard ugly rumors about Nelson Mandela for years. Was he a Communist - or a terrorist? His recent death inspired me to learn more. Alex Tabarrok nudged me to start with Mandela's autobiography, which presumably puts his career in the most favorable possible light.

By the standards of anti-colonial revolutionaries, Mandela comes off very well. He writes no eulogies to murderous hatred, and voices no yearnings for collective revenge. Yet I still have to condemn Mandela as criminally reckless man who knowingly played Russian roulette with forty million lives. Here's how Mandela describes his successful campaign to move the African National Congress onto the path of violence:

Soon after turning to violence, Mandela covertly tours post-colonial Africa, looking for funding. As far as I can tell, he fails to ask his hosts a single morally serious question. Any of the following would qualify: "So, how did independence turn out? What was the body count? Have the people really been 'liberated'? Or have the tyrants merely changed nationality?" While I'm convinced that Mandela was never a Communist, his priorities were thoroughly Leninist: "The point of the uprising is the seizure of power; afterwards we will see what we can do with it."

You could say, "Mandela acted justly because he knew that, once in power, he would rule well." This seems like a stretch given how little intellectual energy he put into peacetime policy analysis. But even if Mandela knew that he would make an excellent president, he was far from sure to land the job. He could easily have died of old age, or been shunted aside by a rival politician promising blood. Or Mandela's buddies in the South African Communist Party could have taken advantage of the revolutionary situation to do what Communists do best: Stab their social democratic allies in the back and assume totalitarian power.

Toward the end of his autobiography, Mandela makes a striking admission: The ANC's turn to violence was about image, not results. In 1990, the ANC weighed whether to suspend armed struggle. Mandela:

Fortunately, Mandela was able to win without stepping over

millions of corpses. But he knowingly took this risk - and repeatedly

pushed his luck. He turned down a long list of reasonable compromises, hoping

that the ruling regime would submit to his ultimatum: "One man, one

vote - or civil war." He romanticized violence to gain leverage, but never worried that this romance would turn ugly. Does the fact that Mandela won his game of Russian roulette make his reckless tactics any more excusable?*

Needless to say, Mandela's opponents were awful, too. But no one's nominating them for sainthood. The harsh reality is that Mandela was a politician. Like virtually all politicians, he measures up poorly against the standards of common decency. Seek your heroes elsewhere.

* Was Mandela's course any more reckless than, say, George Washington's? It's unclear - but that's another telling point against the

American Revolution and its slaveholding philosophers of freedom.

(0 COMMENTS)

By the standards of anti-colonial revolutionaries, Mandela comes off very well. He writes no eulogies to murderous hatred, and voices no yearnings for collective revenge. Yet I still have to condemn Mandela as criminally reckless man who knowingly played Russian roulette with forty million lives. Here's how Mandela describes his successful campaign to move the African National Congress onto the path of violence:

This was a fateful step. For fifty years, the ANC had treated nonviolence as a core principle, beyond question or debate. Henceforth, the ANC would be a different kind of organization. We were embarking on a new and more dangerous path, a path of organized violence, the results of which we did not and could not know.Mandela is well-aware that in modern warfare, innocents routinely perish:

The killing of civilians was a tragic accident, and I felt a profound horror at the death toll. But as disturbed as I was by these casualties, I knew that such accidents were the inevitable consequence of the decision to embark on a military struggle. Human fallibility is always a part of war, and the price for it is always high.Yet he never faces the obvious moral dilemma: Why on earth are you endangering innocent lives if you have no strong reason to believe the consequences will be very good? Mandela's path is especially culpable because he was a voracious reader, but obsessed over a single political question: winning. A typical passage:

I was candid and explained why I believed we had no choice but to turn to violence. I used an old African expression: Sebatana ha se bokwe ka diatla (The attacks of the wild beast cannot be averted with only bare hands). Moses [Kotane] was an old-line Communist, and I told him that his opposition was like that of the Communist Party in Cuba under Batista. The party had insisted that the appropriate conditions had not yet arrived, and waited because they were simply following the textbook definitions of Lenin and Stalin. Castro did not wait, he acted - and he triumphed.Throughout his career, Mandela conspicuously ignores the mountain of historical evidence on the godawful overall consequences of violent revolution. He doesn't just ignore the blood-soaked history of various Communist revolutions, decades earlier and continents away. He also ignores the blood-soaked history of contemporary African independence movements. (See here, here, and here for starters).

Soon after turning to violence, Mandela covertly tours post-colonial Africa, looking for funding. As far as I can tell, he fails to ask his hosts a single morally serious question. Any of the following would qualify: "So, how did independence turn out? What was the body count? Have the people really been 'liberated'? Or have the tyrants merely changed nationality?" While I'm convinced that Mandela was never a Communist, his priorities were thoroughly Leninist: "The point of the uprising is the seizure of power; afterwards we will see what we can do with it."

You could say, "Mandela acted justly because he knew that, once in power, he would rule well." This seems like a stretch given how little intellectual energy he put into peacetime policy analysis. But even if Mandela knew that he would make an excellent president, he was far from sure to land the job. He could easily have died of old age, or been shunted aside by a rival politician promising blood. Or Mandela's buddies in the South African Communist Party could have taken advantage of the revolutionary situation to do what Communists do best: Stab their social democratic allies in the back and assume totalitarian power.

Toward the end of his autobiography, Mandela makes a striking admission: The ANC's turn to violence was about image, not results. In 1990, the ANC weighed whether to suspend armed struggle. Mandela:

... I defended the proposal, saying that the purpose of the armed struggle was always to bring the government to the negotiating table, and now we had done so...So not only did Mandela resort to violence without any strong reason to believe it would lead to good consequences. In hindsight, he wasn't even convinced that violence made much difference. But on his own account, the idea of violence had great appeal. Imagine the horrors the ANC's glorification of bloodshed could have inspired if, say, Mandela had been assassinated by hard-line supporters of apartheid the day after his election.

This was a controversial move within the ANC. Although MK [the armed branch of the ANC] was not active, the aura of the armed struggle had great meaning for many people. Even when cited merely as a rhetorical device, the armed struggle was a sign that we were actively fighting the enemy. As a result, it had a popularity out of proportion to what it had achieved on the ground.

Fortunately, Mandela was able to win without stepping over

millions of corpses. But he knowingly took this risk - and repeatedly

pushed his luck. He turned down a long list of reasonable compromises, hoping

that the ruling regime would submit to his ultimatum: "One man, one

vote - or civil war." He romanticized violence to gain leverage, but never worried that this romance would turn ugly. Does the fact that Mandela won his game of Russian roulette make his reckless tactics any more excusable?*

Needless to say, Mandela's opponents were awful, too. But no one's nominating them for sainthood. The harsh reality is that Mandela was a politician. Like virtually all politicians, he measures up poorly against the standards of common decency. Seek your heroes elsewhere.

* Was Mandela's course any more reckless than, say, George Washington's? It's unclear - but that's another telling point against the

American Revolution and its slaveholding philosophers of freedom.

(0 COMMENTS)

Published on January 21, 2014 21:01

Colonialism and Anti-Colonialism: Blame Nationalism for Both, by Bryan Caplan

Some historians argue that colonialism was an outgrowth of nationalism. Once the people in the leading industrial powers started to strongly identify as British, French, German, American, or Japanese, they fell in love with the idea of planting their national flags all over the map. Hence, "empire."

Other historians argue that anti-colonialism was an outgrowth of nationalism. Once people in Asia and Africa started to strongly identify as Indian, Malaysian, Egyptian, Algerian, or Angolan, they fell in love with the idea of replacing the foreign flags on the map with their own. Hence, "national liberation."

A thinly-veiled political agenda usually stands behind these claims. Most people nowadays agree that colonialism was bad. So if nationalism leads to colonialism, that's a mark against nationalism; but if nationalism leads to anti-colonialism, that's a mark in favor of nationalism. Lingering fans of colonialism naturally reverse these scoring rules.

So who's right about the connection between nationalism and colonialism? As far as I can tell, both sides are right. Nationalism inspired many of the world's mightiest countries to attack and annex the world's economic laggards. But this in turn exposed the inhabitants of the colonies to the idea of nationalism. Before long, native thinkers were marketing their locally-made variants - and calling for national liberation. Once the colonial powers lost the stomach for draconian repression, the anti-colonial movement swiftly triumphed.

If nationalism inspired two incompatible movements, how should we evaluate it? You might just call it a wash: Nationalism giveth, and nationalism taketh away. But this shoulder shrug overlooks two mountains of bodies. The first mountain: All the people killed to establish colonial rule. The second mountain: All the people killed to overthrow colonial rule. It is perfectly fair to blame nationalism for both "transition costs."

Surprising implication: Regardless of the relative merits of colonial versus indigenous rule, the history of colonialism makes nationalism look very bad indeed. Why? Because colonial rule didn't last! So if you're pro-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral wonders, followed by another high transition cost. And if you're anti-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral horrors, followed by another high transition cost. Two dreadful deals, however you slice it.

But don't you either have to be pro-colonial or anti-colonial? No. You can take the cynical view that foreign and native rule are about equally bad. You can take the pacifist view that the difference between foreign and native rule isn't worth a war. Or, like me, you can merge these positions into cynical pacifism. On this view, fighting wars to start colonial rule was one monstrous crime - and fighting wars to end colonial rule was another. Nationalism is intellectually guilty on both counts, because it is nationalism that convinced people around the world that squares of multi-colored cloth are worth killing for.

(12 COMMENTS)

Other historians argue that anti-colonialism was an outgrowth of nationalism. Once people in Asia and Africa started to strongly identify as Indian, Malaysian, Egyptian, Algerian, or Angolan, they fell in love with the idea of replacing the foreign flags on the map with their own. Hence, "national liberation."

A thinly-veiled political agenda usually stands behind these claims. Most people nowadays agree that colonialism was bad. So if nationalism leads to colonialism, that's a mark against nationalism; but if nationalism leads to anti-colonialism, that's a mark in favor of nationalism. Lingering fans of colonialism naturally reverse these scoring rules.

So who's right about the connection between nationalism and colonialism? As far as I can tell, both sides are right. Nationalism inspired many of the world's mightiest countries to attack and annex the world's economic laggards. But this in turn exposed the inhabitants of the colonies to the idea of nationalism. Before long, native thinkers were marketing their locally-made variants - and calling for national liberation. Once the colonial powers lost the stomach for draconian repression, the anti-colonial movement swiftly triumphed.

If nationalism inspired two incompatible movements, how should we evaluate it? You might just call it a wash: Nationalism giveth, and nationalism taketh away. But this shoulder shrug overlooks two mountains of bodies. The first mountain: All the people killed to establish colonial rule. The second mountain: All the people killed to overthrow colonial rule. It is perfectly fair to blame nationalism for both "transition costs."

Surprising implication: Regardless of the relative merits of colonial versus indigenous rule, the history of colonialism makes nationalism look very bad indeed. Why? Because colonial rule didn't last! So if you're pro-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral wonders, followed by another high transition cost. And if you're anti-colonial, nationalism led to a high transition cost, followed by ephemeral horrors, followed by another high transition cost. Two dreadful deals, however you slice it.

But don't you either have to be pro-colonial or anti-colonial? No. You can take the cynical view that foreign and native rule are about equally bad. You can take the pacifist view that the difference between foreign and native rule isn't worth a war. Or, like me, you can merge these positions into cynical pacifism. On this view, fighting wars to start colonial rule was one monstrous crime - and fighting wars to end colonial rule was another. Nationalism is intellectually guilty on both counts, because it is nationalism that convinced people around the world that squares of multi-colored cloth are worth killing for.

(12 COMMENTS)

Published on January 21, 2014 13:55

January 20, 2014

Why So High? Economics and the Value of Life, by Bryan Caplan

Economists are widely-seen as heartless. Their use of the phrase "value of life" is often seen as damning confirmation of this heartlessness. Nice people say, "You can't put a value on a human life" and change the subject!

What's striking, though, is that when you successfully cajole non-economists to put a dollar value on a human life, their numbers are vastly below the economic consensus. Economists' standard estimate is around $7,000,000. Non-economists' usually say under $1,000,000. Their reasoning varies, but I've heard garbled versions all of the following:

1. People can't pay more than they have, and most people have well under a million dollars.

2. People earn around $40,000 per year after taxes, and most have under 25 years left to work. So if you multiply annual earnings by remaining working life, most lives are worth under a million.

3. People need most of their income to live. So if you measure the value of life by people's willingness to pay to stay alive, it's probably no more than $10,000 per year.

Why are economists' numbers so much higher? Part of the reason is that economists detect blatant flaws in all three of the popular approaches:

Flaws with #1: When people bid for a house, their willingness to pay is emphatically not limited by their current possessions. Credit markets allow them to borrow against future earnings. When we estimate people's willingness to pay for their own lives, we should perform an analogous exercise. Maximum willingness to pay is limited by the present discounted value of everything people will EVER own - their time emphatically included.

Deeper flaw: Willingness to accept is just as valid a measure as willingness to pay. For small purchases, these numbers are fairly similar. But for large purchases, they differ dramatically. (Of course if you take this caveat too seriously, economics comes close to endorsing the view that every life is infinitely valuable, since most people will not agree to die for any sum).

Flaws with #2: This approach ignores opportunity cost. You shouldn't just include the value of the time people choose to sell. You should also include the value of the time people choose not to sell. In other words, if you're going to apply this method, you should measure potential earnings, not actual earnings.

Flaws with #3: It's simply not true that people in the First World "need most of their income to live." People can physically survive while couch surfing, eating beans and rice, and working three jobs. And if this austere lifestyle is their only way to stay alive, most submit to it. This is a key lesson of every horrific war of the twentieth century.

If you make economists' recommended refinements, all three popular value of life approaches yield much higher answers. But they're probably still short of $7,000,000. How do economists get to their preferred answer? By using a totally different metric: Willingness to pay (or accept!) for a small change in the probability of staying alive. Something like:

4. How much would you pay to reduce your probability of death by 1 percentage-point? Alternately: How much someone have to pay you to increase your probability of death by 1 percentage-point?

$70,000 is a very reasonable answer to questions like this. Once you buy that idea, simply multiply by 100 to get a $7,000,000 value of life.

But why is approach #4 superior to refined versions of approaches #1, #2, and #3? Truth be told, superiority is not clear-cut. The strongest defense of approach #4, though, is that human beings rarely choose between certain death and a giant pile of money. Instead, they face an endless series of choices between a small probability of death and a modest pile of money. So approach #4 is the best way to quantify the value of life decisions we encounter in the real world.

This remains true even if we know with certainty that one person will die as a result of a choice. Only individuals value stuff. So if each person faces a 1% chance of death, summing the cost each person assigns to his own 1% risk makes sense.

Or does it? Parting thought: Almost everyone - economists and non-economists alike - strangely neglects a big part of the value of life: The value people place on the lives of the people they care about. Human beings worry about each other, and most who die are missed.

Yes, Social Desirability Bias leads us to exaggerate how much we care about strangers and casual acquaintances. But we plainly genuinely care about family and friends. So economists shouldn't just ask how much you'd pay to reduce your risk of death by 1 percentage-point. They should instead ask how much everyone including yourself would pay to reduce your risk of death by 1 percentage-point. Unless you're a total jerk, $7,000,000 a life is probably a serious understatement.

(12 COMMENTS)

What's striking, though, is that when you successfully cajole non-economists to put a dollar value on a human life, their numbers are vastly below the economic consensus. Economists' standard estimate is around $7,000,000. Non-economists' usually say under $1,000,000. Their reasoning varies, but I've heard garbled versions all of the following:

1. People can't pay more than they have, and most people have well under a million dollars.

2. People earn around $40,000 per year after taxes, and most have under 25 years left to work. So if you multiply annual earnings by remaining working life, most lives are worth under a million.

3. People need most of their income to live. So if you measure the value of life by people's willingness to pay to stay alive, it's probably no more than $10,000 per year.

Why are economists' numbers so much higher? Part of the reason is that economists detect blatant flaws in all three of the popular approaches:

Flaws with #1: When people bid for a house, their willingness to pay is emphatically not limited by their current possessions. Credit markets allow them to borrow against future earnings. When we estimate people's willingness to pay for their own lives, we should perform an analogous exercise. Maximum willingness to pay is limited by the present discounted value of everything people will EVER own - their time emphatically included.

Deeper flaw: Willingness to accept is just as valid a measure as willingness to pay. For small purchases, these numbers are fairly similar. But for large purchases, they differ dramatically. (Of course if you take this caveat too seriously, economics comes close to endorsing the view that every life is infinitely valuable, since most people will not agree to die for any sum).

Flaws with #2: This approach ignores opportunity cost. You shouldn't just include the value of the time people choose to sell. You should also include the value of the time people choose not to sell. In other words, if you're going to apply this method, you should measure potential earnings, not actual earnings.

Flaws with #3: It's simply not true that people in the First World "need most of their income to live." People can physically survive while couch surfing, eating beans and rice, and working three jobs. And if this austere lifestyle is their only way to stay alive, most submit to it. This is a key lesson of every horrific war of the twentieth century.

If you make economists' recommended refinements, all three popular value of life approaches yield much higher answers. But they're probably still short of $7,000,000. How do economists get to their preferred answer? By using a totally different metric: Willingness to pay (or accept!) for a small change in the probability of staying alive. Something like:

4. How much would you pay to reduce your probability of death by 1 percentage-point? Alternately: How much someone have to pay you to increase your probability of death by 1 percentage-point?

$70,000 is a very reasonable answer to questions like this. Once you buy that idea, simply multiply by 100 to get a $7,000,000 value of life.

But why is approach #4 superior to refined versions of approaches #1, #2, and #3? Truth be told, superiority is not clear-cut. The strongest defense of approach #4, though, is that human beings rarely choose between certain death and a giant pile of money. Instead, they face an endless series of choices between a small probability of death and a modest pile of money. So approach #4 is the best way to quantify the value of life decisions we encounter in the real world.

This remains true even if we know with certainty that one person will die as a result of a choice. Only individuals value stuff. So if each person faces a 1% chance of death, summing the cost each person assigns to his own 1% risk makes sense.

Or does it? Parting thought: Almost everyone - economists and non-economists alike - strangely neglects a big part of the value of life: The value people place on the lives of the people they care about. Human beings worry about each other, and most who die are missed.

Yes, Social Desirability Bias leads us to exaggerate how much we care about strangers and casual acquaintances. But we plainly genuinely care about family and friends. So economists shouldn't just ask how much you'd pay to reduce your risk of death by 1 percentage-point. They should instead ask how much everyone including yourself would pay to reduce your risk of death by 1 percentage-point. Unless you're a total jerk, $7,000,000 a life is probably a serious understatement.

(12 COMMENTS)

Published on January 20, 2014 07:54

January 18, 2014

Drowning Redheads is Wrong Even Though Water is Wet, by Bryan Caplan

Suppose we lived in a society split between the following intellectual package deals:

Package #1: Water is wet, so we should drown redheads.

Package #2: Water isn't wet, so we shouldn't drown redheads.

What would happen if a lone voice of common sense emerged to say, "Water is wet, but we shouldn't drown redheads"? No doubt he'd be attacked from both sides. Believers in Package #1 would shake their heads and say, "Once you admit that water is wet, you'd have to be a fool to oppose the drowning of redheads." Believers in Package #2 would say, "Once you admit we shouldn't drown redheads, how can you continue to maintain that water is wet?" Believers in Package #2 might even accuse you of being a troll: "You're feigning sympathy for redheads in order to lure us into the absurd view that water is wet."

This scenario captures the way I felt when Noah Smith tweeted:

Package #1: IQ is real, so we should exclude immigrants with below-average IQ.

Package #2: IQ is fake, so we shouldn't exclude immigrants with below-average IQ.

When I talk about ("harp on") IQ research, then, my support for open borders is understandably hard for Package #2 folks to take at face value. At the same time, my support for open borders makes it hard for Package #1 folks to believe that I genuinely grasp the realities of IQ.

As I've argued repeatedly, though, both popular packages are silly - scarcely better than the imaginary packages about the wetness of water and the drowning of redheads. In particular:

1. You don't need an above-average IQ to be a valuable member of society. See here, here, and here for starters.

2. Even if you aren't a valuable member of society, Third World exile is not a morally permissible response. See here, here, and here for starters.

That's my story and I'm sticking to it.

(16 COMMENTS)

Package #1: Water is wet, so we should drown redheads.

Package #2: Water isn't wet, so we shouldn't drown redheads.

What would happen if a lone voice of common sense emerged to say, "Water is wet, but we shouldn't drown redheads"? No doubt he'd be attacked from both sides. Believers in Package #1 would shake their heads and say, "Once you admit that water is wet, you'd have to be a fool to oppose the drowning of redheads." Believers in Package #2 would say, "Once you admit we shouldn't drown redheads, how can you continue to maintain that water is wet?" Believers in Package #2 might even accuse you of being a troll: "You're feigning sympathy for redheads in order to lure us into the absurd view that water is wet."

This scenario captures the way I felt when Noah Smith tweeted:

When challenged to explain his suspicions, Noah added:I strongly suspect @bryan_caplan of being an opponent of immigration, and his "open borders" thing of being a false flag/satire/troll.

-- Noah Smith (@Noahpinion) January 17, 2014

I see where Noah's coming from. Our society is split between the following intellectual package deals:@ModeledBehavior @bryan_caplan Hmm, I'll have to check it out. Are there any other immigration advocates who harp on IQ all the time?

-- Noah Smith (@Noahpinion) January 17, 2014

Package #1: IQ is real, so we should exclude immigrants with below-average IQ.

Package #2: IQ is fake, so we shouldn't exclude immigrants with below-average IQ.

When I talk about ("harp on") IQ research, then, my support for open borders is understandably hard for Package #2 folks to take at face value. At the same time, my support for open borders makes it hard for Package #1 folks to believe that I genuinely grasp the realities of IQ.

As I've argued repeatedly, though, both popular packages are silly - scarcely better than the imaginary packages about the wetness of water and the drowning of redheads. In particular:

1. You don't need an above-average IQ to be a valuable member of society. See here, here, and here for starters.

2. Even if you aren't a valuable member of society, Third World exile is not a morally permissible response. See here, here, and here for starters.

That's my story and I'm sticking to it.

(16 COMMENTS)

Published on January 18, 2014 07:38

January 17, 2014

The Prudence of the Poor, by Bryan Caplan

Ari Fleisher in the WSJ:

Cochrane would have been on much firmer ground if he'd said, "While the poor do have below-average IQs, they have more than enough brains to see consequences of single parenthood." If he said that, I'd agree. But this revised position still neglects the possibility that people who foresee bad consequences of their behavior will fail to exercise self-control. As a result, they predictably make imprudent decisions when their choices have pleasant short-run effects - even if the long-run results are predictably awful.

The empirics on the poor's lack of self-control are not as abundant as the empirics on the poor's low IQ. But the empirics are out there. And even if there were no empirics at all, it would be very surprising if low self-control failed to sharply reduce income in a high-tech society.

Does this undermine Cochrane's claim that "[H]elping the poor to realize" is pretty hopeless as a policy

prescription"? At first glance, no. When someone has low intelligence, it's hard to make him realize stuff; when someone has low self-control, it's hard to make him act on what he realizes.

On further reflection, though, there are multiple ways to make people "realize." The most popular - and, I suspect, the one Cochrane dismisses - is publicly-funded nagging. An alternative route to realization, though, is simply cutting government subsidies for imprudent behavior.

Such cuts have two effects. First, cutting subsidies for imprudent behavior makes the imprudence even more blatant than it already was. Second, cutting subsidies for imprudent behavior makes the behavior's unpleasant consequences happen sooner, potentially deterring even the highly impulsive. As Scott Beaulier and I put it:

(4 COMMENTS)

Given how deep the problem of poverty is, taking even more money fromJohn Cochrane demurs:

one citizen and handing it to another will only diminish one while doing

very little to help the other. A better and more compassionate policy

to fight income inequality would be helping the poor realize that the

most important decision they can make is to stay in school, get married

and have children--in that order.

"[H]elping the poor to realize" is pretty hopeless as a policyBut why on earth should we believe that the poor are "smart"? There is overwhelming evidence that the poor have substantially below-average IQs. And even without these empirics, it would be very surprising if low cognitive ability failed to sharply reduce income in high-tech societies.

prescription. They poor are smart, and huge single parenthood rates do

not happen because people are just too dumb to realize the consequences,

which the see all around them.

Cochrane would have been on much firmer ground if he'd said, "While the poor do have below-average IQs, they have more than enough brains to see consequences of single parenthood." If he said that, I'd agree. But this revised position still neglects the possibility that people who foresee bad consequences of their behavior will fail to exercise self-control. As a result, they predictably make imprudent decisions when their choices have pleasant short-run effects - even if the long-run results are predictably awful.

The empirics on the poor's lack of self-control are not as abundant as the empirics on the poor's low IQ. But the empirics are out there. And even if there were no empirics at all, it would be very surprising if low self-control failed to sharply reduce income in a high-tech society.

Does this undermine Cochrane's claim that "[H]elping the poor to realize" is pretty hopeless as a policy

prescription"? At first glance, no. When someone has low intelligence, it's hard to make him realize stuff; when someone has low self-control, it's hard to make him act on what he realizes.

On further reflection, though, there are multiple ways to make people "realize." The most popular - and, I suspect, the one Cochrane dismisses - is publicly-funded nagging. An alternative route to realization, though, is simply cutting government subsidies for imprudent behavior.

Such cuts have two effects. First, cutting subsidies for imprudent behavior makes the imprudence even more blatant than it already was. Second, cutting subsidies for imprudent behavior makes the behavior's unpleasant consequences happen sooner, potentially deterring even the highly impulsive. As Scott Beaulier and I put it:

What do these behavioral findings have to do with the poor? Take the case of single mothers. On the road to single motherhood, there are many points where judgmental biases plausibly play a role. At the outset, women may underestimate their probability of pregnancy from unprotected sex. After becoming pregnant, they might underestimate the difficulty of raising a child on one's own, or overestimate the ease of juggling family and career. Policies that make it easier to become a single mother may perversely lead more women to make a choice they are going to regret.As far as poverty policy goes, I suspect that Cochrane and I are on the same austerian page. My fear is that he's discrediting the correct conclusion with implausible justifications. The Chicago descriptive view that everyone is "smart" has little to do with the Chicago prescriptive view that government is way too big. Indeed, as Donald Wittman has shown, it's hard to argue that government is way too big unless you're willing to insult the intelligence of a great many people. I'm happy to bite that bullet. Cochrane should do the same.

A simple numerical example can illustrate the link between helping the poor and harming them. Suppose that in the absence of government assistance, the true net benefit of having a child out-of-wedlock is -$25,000, but a teenage girl with self-serving bias believes it is only -$5000. Since she still sees the net benefits as negative she chooses to wait. But suppose the government offers $10,000 in assistance to unwed mothers. Then the perceived benefits rise to $5000, the teenage girl opts to have the baby, and ex post experiences a net benefit of -$25,000 + $10,000 = -$15,000.

(4 COMMENTS)

Published on January 17, 2014 02:44

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.