Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 154

February 18, 2014

My Cato Address to Students for Liberty, by Bryan Caplan

Welcome

Students for Liberty! I'm so happy to see all of you in the world's

greatest cathedral of liberty.

It didn't

look like this 23 years ago, when I interned for Cato. In 1991, Cato fit in one mid-sized house,

plus an annex across the parking lot. I

worked for Tim Lynch and Doug Bandow.

And I was also assigned a special task by David Boaz - throwing obsolete

paperwork out of the file cabinets. As a

result, I was greatly amused by an E.J. Dionne's footnote in Why

Americans Hate Politics , "My thanks to Ed Crane and David Boaz of

the Cato Institute for letting me read through their excellent files of

clippings on libertarianism... To their credit, the libertarians save

everything and not just the flattering stuff." The files that Dionne

perused had actually been cleaned out years earlier... by me!

While a

great deal has changed at Cato since my internship, I'm pleased by how much has

stayed the same. I still remember David

Boaz telling me that Cato aims to be "libertarianism with a human face." My first-hand experience tells me that Cato

lives up to this ideal: Promoting liberty with civility and a smile.

Ideally, of

course, it's mutual civility and smiles.

But unilateral friendliness still beats the alternative. Selling radical ideas is hard, but selling

them with a chip on your shoulder is virtually impossible. And in all honesty, there is plenty of truth

in the stereotype of the hostile, insulting libertarian. Yea, that was me.

If you

don't like the stereotype, denying its roots in the facts is pointless. It's far better to undo the negative stereotype

by violating it - and politely policing our own. Private police, mind you! Students for Liberty has been doing yeoman work on this

count. From my first Students for

Liberty Conference, I've been amazed by the social intelligence of the next

libertarian generation. I'm not sure how

you're pulling it off, but please please please keep up the good work.

If you have

any interest in nudging government policy in a more libertarian direction, Cato

is the most valuable connection in the world.

Cato publishes on virtually every policy-related topic you can imagine:

economic policy, social policy, foreign policy, you name it. And it continues its long-standing big-tent

approach. Cato hosts every flavor of

libertarianism from the most moderate to the most extreme - not to mention

liberal and conservative fellow travellers.

What counts is sound reasoning and a positive attitude - not orthodoxy.

Hard-core

libertarians occasionally grumble about Cato's moderation. What they tend to forget is that Cato is

trying to sell libertarian ideas to people who aren't already buying them. Under the circumstances, avoiding "extremes"

of anger and impatience is just common sense and common decency. But that's not enough. It's also important to make a wide range of

views feel part of a shared endeavor. I'm

as extreme a libertarian as they come, but I'm still delighted to have

moderates around. If I'm not persuasive

to moderate libertarians, I need to improve.

In a perfect

world, Cato's worldly mission would already be accomplished. Your job, as the next generation, would just

be writing the history of statism's welcome demise. As it turns out, though, the world remains

light-years from libertarian ideals - and some relatively libertarian countries

- especially the United

States - have spent the last decade and a

half back-sliding. And enormous,

flagrant violations remain even in the self-styled "free world." Unless you're lucky enough to be borne in a

rich country, the world's governments legally exclude you from the best labor

and housing markets. A few years ago, I

asked my readers to distinguish

the status quo from the Jim Crow laws, and I've yet to hear a decent

answer.

The

persistence of statism is bad news for liberty, but good news for your careers

and your free time. There is an enormous

amount of work and play for libertarians in public policy, academia,

journalism, the arts, and - if you can stomach it - politics. Some of it is intellectual, but even more of

it is salesmanship. Gandhi was right:

You must be the change you wish to see in the world. All of us can, like Cato, nudge the world in

a freer direction with good arguments and good cheer. This is, to put it mildly, an uphill

battle. But when I'm standing in the

cathedral of liberty with the next generation of the liberty movement, I can't

help but feel optimistic.

February 17, 2014

Ballparking the Marital Return to College, by Bryan Caplan

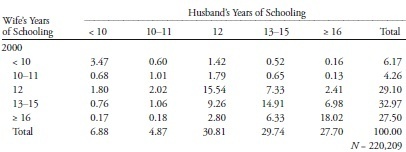

The most obvious explanation for this omission is that the spousal education gradient is weak. But the opposite is true. Here's a revealing table from Schwartz and Mare's "Trends in Educational Assortative Marriage from 1940 to 2003" (Demography, 2005).

Assume you're going to marry someone. Then if you only have a high school diploma, your probability of marrying a college grad is about 9% for both men and women. With a 4-year college degree, in contrast, your probability of marrying a college grad is roughly 65%. Quite a difference.

Of course, this pattern probably isn't entirely causal. But a large causal effect is highly plausible. Indeed, there are two credible causal channels: convenience and compatibility. Convenience: If you're a college grad, you're more likely to meet fellow college grads. Compatibility: If you're a college grad, you're more likely to hit it off with whatever college grads you happen meet.

Now suppose that only half of the raw probability difference is causal. This still means that if you finish college, you're a full 28 percentage-points ([65-9]*.5) more likely to marry a college grad than a high school grad. You could even say that the average college grad who plans to eventually marry can expect to enjoy the financial benefits of 1.28 sheepskins, rather just one. As long as the gender earnings gap continues, this marital return is larger for women than for men. But given modern women's high employment rates, the marital return is clearly a big deal for men, too.

Why is the marital return so rarely discussed by either economists or laymen? Probably because talking about the marital return is self-defeating. The more you talk about it, the more you sound like a gold-digger - and the more you sound like a gold-digger, the less marriageable you become! The thoughtful response to the evidence, though, is neither denial nor gold-digging. Instead, the evidence underscores an age-old adage: Don't marry for money; go where the rich people are and marry for love.

(1 COMMENTS)

February 14, 2014

Lenin the Prohibitionist, by Bryan Caplan

"Death is preferable to selling vodka!" Lenin declared prior to the revolution. True to his prohibitionist principles, he held fast to that conviction after seizing power. Even with vodka's counterrevolutionary threat subsiding, Lenin's ruling Sovnarkom, or Council of People's Commissars... nationalized all alcohol production facilities and existing alcohol stocks. In 1919, Sovnarkom forbid distilling "by any means, in any quantity and at any strength" - punishable by confiscation of all property and a minimum of five years in Siberian labor camps.Lenin the prohibitionist poet:

"Whatever the peasant wants in the way of material things we will give him, as long as they do not imperil the health or morals of the nation," Lenin famously declared late in life. "But if he asks for ikons or booze - these things we will not make for him. For that is definitely retreat; that is definitely degeneration that leads him backward. Concession of this sort we will not make; we shall rather sacrifice any temporary advantage that might be gained from such concessions."If, like me, you have zero sympathy for prohibition, Schrad's sordid tale of Russia's collective drunken stupor over the last century will give you second thoughts. At the same time, though, Schrad's account will give pause to even the most ardent prohibitionist. The unintended consequences of Russia's periodic crackdowns on alcohol were straight out of an econ textbook: bootlegging, adulteration, poisoning, corruption, and violence galour. Russian alcoholism is terrifying and sickening - yet Russian prohibition is even worse.

P.S. If you see me at Students for Liberty this weekend, please say hi. I'll probably be eating at the Bistro at the Grand Hyatt tonight around 7 PM if you'd like to join me.

(6 COMMENTS)

February 12, 2014

What Bad Students Know that Good Economists Don't, by Bryan Caplan

Over the last two months, I've read virtually everything ever written on this puzzle. All of the compelling stories converge on a single factor I've emphasized for years: The return to trying to get a degree is far lower than the return to successfully getting a degree. Why? Because marginal students routinely fail to graduate. The single best paper on this theme: "The Education Risk Premium" by Janice Eberly and Kartik Athreya.

Eberly and Athreya begin by spelling out the puzzle:

When measured by the ratio of hourly wages of skilled to unskilled workers, the college premium increased by nearly 20% between 1980 and 1996 (see Autor, Katz, and Krueger (1998)). However, enrollment did not respond substantially. Over the period 1979-2005, even though the fraction of young adults (29 years and younger) with a college degree rose by 9 percentage points (23% to 32%), the increase in male enrollment accounted only for one percentage point (Bailey and Dynarski (2009)).Quick version of their solution: Expected returns heavily depend on graduation rates - and graduation rates heavily depend on students' pre-existing academic ability.

The presence of failure risk generates asymmetric changes in the net return to college investment: those with low failure risk see a large increase in expected returns, but are inframarginal because they will enroll under most circumstances. Those with high failure risk see a much smaller increase in expected returns, and hence remain largely inframarginal.Let me illustrate. Suppose you're at the 90th-percentile of high school graduates, so your probability of graduating college if you enroll is around 90%. When the college premium ascends from 50% to 70%, your expected premium goes from 45% to 63%. In plain English, the payoff goes from very good to excellent. Either way, enrollment is a no-brainer.

If instead you're at the 25th-percentile of high school graduates, your probability of graduating college if you enroll is around 20%. When the college premium ascends from 50% to 70%, your expected premium goes from 10% to 14%. In plain English, the payoff goes from really crummy to crummy. Either way, non-enrollment is a no-brainer... especially when you dwell on the fact that colleges don't refund drop-outs' tuition, much less the earnings and work experience they forfeited to attend.

Eberly and Athreya simulate college enrollment under a range of assumptions about the college premium and the completion probability. The right-most column shows the overall fraction of each cohort of kids

that enrolls in college as a function of the college premium. Here is wisdom:

Notice the massive fall-off as the failure probability rises from 50% to 66%. With failure probabilities of 80% or so, even massive premia understandably fail to motivate. For students in the bottom quartile of academic ability, paying a year's tuition is almost as foolish as buying 10,000 lottery tickets. As Eberly-Athreya explain:

[W]ell-prepared enrollees face low failure risk and so already receive a high rate of return from college under any skill premium in the approximate vicinity of the current one. Similarly, the ability of the skill premium to meaningfully alter mean returns for the ill-prepared is minimal. The only remaining question is then: how large is the set of marginal households? The answer provided by the model is: not very big.My favorite feature of Eberly-Athreya: Their story readily generalizes to other weighty life choices widely seen as "no-brainers." Conventional wisdom condemns dropping out of high school. After all, standard estimates say that finishing high school raises your income by 50%. For good students, it's easy money. For stereotypical "bad students," though, it's hard money - or a waste of money. Why? Because when bad students attend high school, their probability of graduation - and their expected return - remains fairly low.

The same holds for marriage. The economic benefits of stable marriage are massive. But as Charles Murray explains, the probability of stable marriage varies widely by social class. Divorce rates for the working class are about four times as high as for professionals. Marginal brides and grooms therefore face a high probability of marital failure - and can reasonably fear that marriage will make them worse off despite its palpable benefits.

To be fair, Eberly and Athreya are not the first or only education researchers to highlight the chasm between ex ante and ex post returns to education. But as far as I can tell, no one makes the logic clearer. If anyone taunts, "So your kids should go to college, but other people's kids shouldn't," the honest answer is "Don't shoot the messenger - or his kids." The numbers don't lie: College is a great investment for great students, a mediocre investment for mediocre students, and a bad investment for bad students.

* This is seriously inflated by ability bias, but over half of the effect looks causal.

(6 COMMENTS)

February 11, 2014

Evolutionary Psychology on Crusonia, by Bryan Caplan

Two questions:

1. What fraction of castaways pair bond over the next ten years?

2. If the castaways are unexpectedly rescued and return to their home country, what fraction of pair bonds remain together over the following ten years?

Please show your work.

(4 COMMENTS)

February 10, 2014

The Futility of Quarreling When There Is No Surplus to Divide, by Bryan Caplan

Option A: Date

Option B: Be Friends

Option C: Stop Seeing Each Other

Person #1's preference ordering is: {A, C, B}. In English, #1 most prefers to date, and least prefers to just be friends.

Person #2's preference ordering is: {B, C, A}. In English, #2 most prefers to just be friends, and least prefers to date.

In popular stereotypes, Person #1 is male, and Person #2 is female. But role reversal is probably common, too.

Given these preferences, anything other than C naturally leads to bad feelings. Person #1 resents being stuck in "the friend zone." Person #2 resents Person #1's view that being friends is an imposition or probationary situation. It's easy to see how they might angrily quarrel with each other, with Person #1 harping on his superiority to whoever Person #2 dates, and Person #2 pointing out that Person #1 should be grateful for their friendship. The fight could get really ugly, as in the web comic "The Friend-Zoner vs. Nice Guy."

On reflection, though, this quarreling is the epitome of futility. Sure, argument has been known to change preferences. But these preferences? Is #1 really going to argue #2 into feeling attracted to him when she's not? Is #2 really going to argue #1 out of his feelings of yearning and rejection? Extremely unlikely. Quarreling is ultimately a form of bargaining. With preference orderings {A, C, B} and {B, C, A}, the only mutually beneficial bargain is ceasing to deal with each other. And since either person can instantly and unilaterally jump to C by saying, "So long, have a nice life," what's the point of quarreling to get there?

If you're deeply economistic, you'll naturally ask, "Why not consider Option D: side payments?" "If you agree to just be friends, I'll do your laundry" or "If you agree to date, I'll pay for every meal." But in many cases - if not most - offering or accepting side payments feels so degrading that neither side can accept it. Option D is off the table because the parties' expanded rankings are {A, C, B, D} and {B, C, A, D}.

Needless to say, people have imperfect information about other people's preferences. Indeed, people have imperfect information about their own preferences. Yet in many real world relationships, preferences are fairly obvious - and my analysis applies.

I suspect that many non-economists will dismiss this whole approach as "overly analytical." I beg to differ. Widespread futile quarreling is a strong sign that emotional approaches have failed. The only way out is to calm down and admit that bad matches aren't anyone's fault. When two people want incompatible things, they should politely say goodbye and move on with their lives. Almost everyone can see this by the time they're 40. With economics by your side, you can attain this enlightened state at once.

(9 COMMENTS)

What the Swiss Vote Really Shows, by Bryan Caplan

In my view immigration has gone well forBut there's a major problem with Tyler's story: Swiss anti-immigration voting was highest in the places with the least immigrants! This is no fluke. In the U.S., anti-immigration sentiment is highest in the states with the least immigration - even if you assume that 100% of immigrants are pro-immigration.

Switzerland, both economically and culturally, and I am sorry to see this

happen, even apart from the fact that it may cause a crisis in their relations

with the European Union. That said, you can take 27% as a kind of

benchmark for the limits of immigration in most or all of today's wealthy

countries. I believe that as you approach a number in that range, you get

a backlash.

The natural inference to draw, then, is the opposite of Tyler's: The main hurdle to further immigration is insufficient immigration. If countries could just get over the hump of status quo bias, anti-immigration attitudes would become as socially unacceptable as domestic racism. Instead of coddling nativism with gradualism, we can, should, and must peacefully destroy nativism with abolitionism.

(11 COMMENTS)

February 9, 2014

A Question of Organizational Literacy, by Bryan Caplan

Please show your work.

(11 COMMENTS)

February 8, 2014

Bias and Bigness Bleg, by Bryan Caplan

Why do so many regulations exempt firms with small numbers of employees (typically 50 or less) - and so few regulations exempt firms with large numbers of employees?

Please show your work.

(19 COMMENTS)

February 6, 2014

How Rival Marriage Is, by Bryan Caplan

If you share your home with a spouse, you don't have as much space forThen I asked:

yourself as a solitary occupant of the same property. But both of you

probably enjoy the benefits of more than half a house. If a

couple owns one car, similarly, both have more than half a car. Even

food is semi-rival, as the classic "You gonna eat that?" question

proves.

Mathematically, married individuals' utility looks something like this:

U=Family Income/2a

a=1 corresponds to pure rivalry: Partners pool their income, buy stuff, then separately consume their half. a=0 corresponds to pure non-rivalry: Partners pool their income, buy stuff, then jointly consume the whole.

There's little doubt that aeven built into the official poverty line. That's why I say that being single is a luxury. My question: Where does a typically lie in the real world? Feel free to discuss variation by social class and nationality. Please show your work.In the comments, ce advised me to look into "Equivalence Scales." Bill Dickens subsequently did the same. When I finally followed through, I found that my blog post successfully reinvented the wheel, functional form included. From Buhmann et al., "Equivalence Scales, Well-Being, Inequality, and Poverty" (Review of Income and Wealth, 1988):

Concern with equivalence scale issues has led the authors to undertake an informal survey of equivalence scales in use in different countries...My equation, which sets S=2 for a married couple without kids, is just a special case of (1). More importantly, though, Buhmann et al. review a large literature that actually estimates e (my a). There are four distinct empirical strategies:

The scales we have assembled can be represented quite well by a single parameter, the family size elasticity of need. We assume that economic well-being (W) or "adjusted" income, can be equated to disposable income (D) and size (S) in the following way:

The equivalence elasticity, e, varies between 0 and 1; the larger it is the smaller are the economies of scale assumed by the equivalence scale.

(1) Expert Statistical (STAT)The results heavily depend on which of the four methods you use. After reviewing the extant literature (which hasn't grown too much since), Buhmann et al. reach the following rough values:

In this case the scales are developed only for statistical purposes-that is, in order to count persons below or above a given standard of living - minimum adequacy, for example. The Bureau of Labor Statistics family budgets are a good example, or the scales used by OECD or the European community to count the low income population.

(2) Expert Program (PROG)

The second type of expert scale is focused on defining benefits for social programs-the Supplementary Benefits scale, or the Swedish "base amount" are examples of scales use to calculate benefits under social protection programs. The U.S. poverty line was initially developed for statistical purposes but over the years had come to serve also as a guide to the adequacy of program benefits.

(3) Consumption (CONS)

In this case the effort is to measure utility indirectly through the revealed preferences of consumer spending constrained by disposable income. The equivalence scales contained in the 1982 article in this journal by Van der Gaag and Smolensky [1982] which are shown in Line 19 of Table 2 are of this variety.

(4) Subjective (SUBJ)

Here the goal is to measure directly the utility associated with particular income levels for families of given characteristics. Different questions related to evaluation of own income (IEQ), to minimum income needed by others to get along (MIQ) or what money buys (PIE) are used to elicit these scales.

SUBJ - a scale with an elasticity of 0.25Notice: The subjective (asking people) and consumption (looking at spending behavior) approaches both give small answers, implying low rivalry of consumption. Government statisticians' approaches, in contrast, both give substantially bigger answers, implying moderate-high rivalry of consumption. Assuming married couples share equally, these elasticities imply that couple's effective per-capita consumption ranges from Family Income/1.19 (for e=.25) to Family Income/1.65 (for e=.72).

CONS - a scale with an elasticity of 0.36

PROG - a scale with an elasticity of 0.55

STAT - a scale with an elasticity of 0.72

Who cares? Imagine two singles: One earns $60,000 per year; the other earns $40,000 per year. Here's happens to their effective consumption if they marry and share equally:

Method

Effective Consump.

High-Earner's Gain

Low-Earner's

Gain

SUBJ

$84,090

$24,090

$44,090

CONS

$77,916

$17,916

$37,916

PROG

$68,302

$8,302

$28,302

STAT

$60,710

$710

$20,710

As you'd expect, the low-earning spouse makes out like a bandit. The surprise: The high-earning spouse gains as well - for all four ways to estimate real-world rivalry. If consumption were 100% rival, in contrast, the high-earner would lose $10,000 - precisely the amount the low earner gains.

To be sure, the magnitude of the high-earner's gain depends heavily on which of the four methods you use. Is there any reason to prefer one method to the others? Yes. People have ample first-hand experience with household management, so the subjective approach is probably better than deferring to government statisticians' opinions. And looking at actual consumption behavior is probably better than asking people what they think.

So how rival is your marriage? If you're a typical couple, simply plug in your total family income, divide by 1.28, and you're done. Thus, if one partner outearns the other by 50%, share-and-share-alike marriage raises the high-earner's effective consumption by about 30%, and the low-earner's effective consumption by about 100%. To quote Keanu, "Woh."

Note: These calculations deliberately ignore all the evidence that marriage makes family income go up via the large male marriage premium minus the small female marriage penalty. So the true effect of marriage on economic well-being is probably even more massive than mere arithmetic suggests. Why then are economists - not to mention poverty activists - so apathetic?

(6 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers