Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 161

November 18, 2013

Bartender, Cashier, Cook, Janitor, Security Guard, Waiter, by Bryan Caplan

By itself, malemployment is compatible with the human

capital model. How? Graduates are "malemployed" because they

failed to acquire marketable job skills in school. This could mean that malemployed graduates

failed to learn and retain the curriculum; recall that on the National

Assessment of Adult Literacy, over 50% of high-school grads and almost 20% of college

grads have less than Intermediate literacy and numeracy. Or it could mean that malemployed graduates

learn an irrelevant curriculum; recall that over 40% of high school coursework

and over 40% of college majors score "Low" in usefulness. When a B.A. bartender asks, "Why oh why can't

I get a better job?," the human capital model bluntly answers, "Because despite

your credentials, you didn't learn how to do

a better job."

The signaling model weaves a rather contrary tale. Malemployment reflects an arms race in the

labor market - workers' never-ending struggle to outshine each other. Rising education automatically sparks

credential inflation: The amount of education you need to convince employers to

hire you automatically rises too. In an

everyone-has-a-B.A. dystopia, an aspiring janitor might need a master's in

Janitorial Studies to land a job scrubbing toilets. When a B.A. bartender asks, "Why oh why can't

I get a better job?," the signaling model answers, "Because too many competing

workers have even more impressive credentials than you do."

If both human capital and signaling allow for malemployment,

why raise the issue? Because the two stories

diverge on one crucial point: Does the labor market reward workers for education

they do not use? Human capital says no; signaling says

yes. Take bartenders with B.A.s. On the plausible assumption that college does

not transform students into better bartenders, the human capital model predicts

that B.A.s will fail to raise bartenders' income. The signaling model, in contrast, predicts

the opposite: Bartenders with B.A.s will outearn bartenders without B.A.s. Why?

Because bars, like all businesses, want intelligent, conscientious,

conformist workers - and a B.A. signals these very traits. So given a choice, bars favor applicants with

B.A.s despite the irrelevance of the academic curriculum to the job.

[...]

however, we must zero in on occupations with little or no plausible connection

to traditional academic curricula. Despite

many debatable cases, there are common occupations that workers clearly don't learn in school. Almost no one goes to high school to become a

bartender, cashier, cook, janitor, security guard, or waiter. No one goes to a four-year college to prepare

for such jobs. Yet as Table 4.6 shows,

the labor market comfortably rewards bartenders, cashiers, cooks, janitors,

security guards, and waiters for both high school diplomas and college degrees.

Occupation

H.S. Premium

College Premium

bartender

+61%

+62%

cashier

+171%

+30%

cook

+17%

+25%

janitor

+35%

+12%

security guard

+60%

+29%

waiter

+135%

+47%

High school premium = [(median earnings for high school

graduates)/(median earnings for high school drop-outs] -1.

College premium = [(median earnings for college

graduates)/(median earnings for high school graduates)] -1.

Source: Supplementary data for The College Payoff, supplied by author

Stephen Rose.

None of these occupations are weird outliers. True, most bartenders, cashiers, cooks,

janitors, security guards, and waiters lack college degrees. Yet in the modern economy, all are common

jobs for college grads. More work as

cashiers (48th most common job for college grads) or waiters (50th)

than mechanical engineers (51st).

More work as security guards (67th) or janitors (72nd)

than network and computer systems administrators (75th). More work as cooks (94th) and

bartenders (99th) than librarians (104th). I selected Table 4.6's occupations to minimize

controversy. Human capital purists could

insist that college provides useful training for electricians, real estate

agents, or secretaries. But even the

staunchest fans of human capital theory struggle to say, "College prepares the

next generation of cashiers and janitors for their careers" without smirking.

I borrow this example from Vedder et al, p.28: "We

jokingly predict that colleges will offer a master's degree in Janitorial

Studies within a decade or two and anyone seeking employment as a janitor will

discover no one will hire unless proof of possession of such a degree is

presented."

How Staggering is the Briggs-Tabarrok Effect?, by Bryan Caplan

A new study, coauthored by a libertarian-aligned economist, has foundHere is Tabarrok's summary* of the study's results:

strong evidence that the spread of gun ownership around the United

States is a threat to public health...Tabarrok and his coauthor, Justin Briggs, put together a bunch of

data on gun ownership and suicide. After controlling for a series of

potentially confounding factors, Tabarrok and Briggs ran a series of

regressions to establish any links between guns and suicides.

Their results were staggering.

Using a variety of techniques and data weNote the lack of superlatives. So how "staggering" is this Briggs-Tabarrok Effect?

estimate that a 1 percentage point increase in the household gun ownership rate

leads to a .5 to .9% increase in suicides.

To answer, you need to know two additional facts.

1. The total number of suicides in the U.S. is roughly 40,000 per year (38,285 for 2011).

2. There are about 310 million people in the United States.

Thus, the Briggs-Tabarrok effect says that depriving 3,100,000 people of their guns (a 1 percentage-point decrease in the gun ownership rate) would save about 200-360 lives (.5*40,000=200; .9*40,000=360). In ratio form, the Briggs-Tabarrok effect says that to prevent a single suicide, 8,600 to 15,500 people - the vast majority of whom are not suicidal - must lose their guns.

Is that a good deal? A standard $7M value of life implies a critical value of gun ownership between $452 and $814 per person per year. If the marginal person's value of gun ownership is less than that, gun deprivation passes the cost-benefit test. If the marginal person's annual value of gun ownership exceeds that, gun deprivation fails the cost-benefit test. Note that this is not a value per gun; it is a value per person of having any guns.

If, like me, you've never held a gun, this might sound like a no-brainer. How could anyone value gun ownership so highly? If that's what you think, though, you really need to get out of your Bubble. About 40% of American households own guns. Self-defense aside, firearms are the foundation for several of the most popular hobbies in America - shooting and hunting for starters. Anyone who rails against "gun nuts" can hardly deny that many folks adore gun ownership.

Not convinced? The Briggs-Tabarrok story implies that you can unilaterally cut your family's suicide rate by getting rid of your family's guns. (The same does not hold, of course, for your family's murder rate). So suppose every gun owner in America were fully aware of the Briggs-Tabarrok Effect. How many of these gun owners would get rid of their guns in order to avoid an extra 0.01% chance of suicide for each person with access to their guns? How many would deem such a risk "staggering"? If you say, "Not many," you are conceding that most gun-owners value their guns more than a tiny risk to those they hold dear.

But is a pure cost-benefit approach to gun suicides even appropriate? Probably not. Everyone makes fun-but-risky choices - on diet, lifestyle, and sex for starters. The risks you take affect not only you, but the people who care about you. Many are far riskier than the Briggs-Tabarrok Effect. Yet almost thinks it's wrong to use cost-benefit analysis to veto these personal decisions: "My body, my choice." So why single out gun owners for welfare-enhancing persecution?

If you personally know a lot of gun owners, the Briggs-Tabarrok Effect should concern you. Accessible guns probably do slightly increase the chance that someone you care about will kill himself. So be more cautious and spread the word. But if you don't personally know a lot of gun owners, you should mind your own business. Gun owners reasonably discount sermons about "staggering" risks from people who utterly fail to appreciate their hobby. Want to help people? Focus your nudging on risky activities prevalent among the people you personally know. You'll sound less intolerant, be more persuasive, and do more good.

* Beauchamp accurately quotes Tabarrok's initial claim that "A 1% increase in the household gun ownership rate leads to a .5 to .9% increase in suicides." Tabarrok revised his post after I emailed him for clarification.

(23 COMMENTS)

November 14, 2013

Hobbesian Misanthropy in The Purge, by Bryan Caplan

Suppose a random person is living on a desert island without hope of

rescue. Call him the Initial Inhabitant, or I.I. Another random person

unexpectedly washes up on shore, coughing up water. Call him the New

Arrival, or N.A. While N.A. is helplessly gasping for air, what does

I.I. do? Just to make the story interesting, let's suppose that N.A. is

much bigger than I.I.

Thomas Hobbes' prediction, on my reading, is that I.I. will immediately pick up a rock and murder N.A....

Preemptive

murder may seem paranoid. But here's the Hobbesian logic: If I.I.

waits for N.A. to catch his breath, N.A. will be strong enough to

overpower him if he so desires. It's therefore in I.I.'s interest to

kill N.A. before N.A. becomes a threat.In my view, the Hobbesian prediction is crazy. Virtually no one

alone on a desert island would choose the route of preemptive murder.

Yes, it's possible that N.A. will catch his breath and then

attack. But it's far more likely that N.A. will catch his breath and

say, "Boy, am I glad to see you. At least I'm not alone." And I.I.

will say the same thing back. Two normal humans in a Hobbesian scenario

become fast friends, not mortal enemies.

The recent movie The Purge almost perfectly matches my Hobbesian thought experiment. [Warning: spoilers!] In the movie, the United States adopts an annual holiday ("the Purge") featuring a twelve hour period of utter lawlessness. People can murder each other free of all legal interference and consequence. The result isn't quite as awful as Hobbes would predict, but it's close. Most people hide in their homes, but at least 10% of the population in a nice neighborhood whips out knives and guns and goes huntin'. Young men, bizarrely, are not overrepresented. Women and the middle-aged seem equally eager to join the sick, twisted fun.

I'm not a hard sci-fi guy. But I do place great artistic value on emotional truth. The Purge has none. A single-digit percentage of young males probably do harbor murderous urges, but that's about the size of it. And even young males with homicidal tendencies usually need intense social pressure to overcome their (a) natural squeamishness, and (b) natural cowardice. Trying to murder alert, well-armed strangers in their own homes is very dangerous even if you feel the urge to do so - a truism that the plot bears out ad nauseum.

The only remotely plausible non-defensive murder attempt in the movie is when Ethan

Hawke's daughter's age-inappropriate boyfriend tries to bushwhack him. All the remaining violence is ludicrous or worse. At the end of the movie, middle-aged neighbors of both sexes cackle with glee at the thought of murdering a harmless housewife, her teenage daughter, and tween son. If that's not misanthropic paranoia, nothing is.

What would really happen if we had the Purge tomorrow? 95%+ of the population would hunker down. 5% of young males would initially run amok... until a few hundred were shot dead on national t.v. by well-armed home- and business-owners. Remember: In the typical modern American riot, many of the targets are easily identifiable when the dust settles, so they can't aggressively defend themselves from anonymous rioters. Under the rules of the Purge, however, nervous targets could safely play, "Shoot first, ask questions later." Young men hoping to "release the Beast" would soon release the Jackrabbit instead.

In any case, imagining a Purge tomorrow is a worse-case scenario because it leaves so little time to adjust. Given one year's warning, private security services, motivated by the power of reputation rather than legal obligation, would energetically fill in for absent government police. After a shockingly peaceful Purge, fair-minded observers might even proclaim a small victory for anarcho-capitalism. Not that it would make any difference. Mainstream observers would quickly drone, "Move on, nothing to see here."

(9 COMMENTS)November 13, 2013

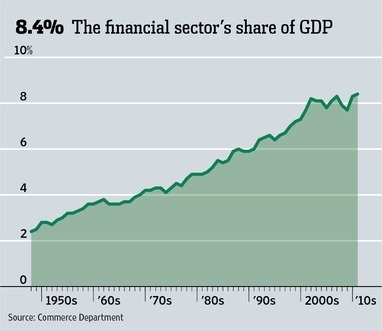

Would Buy-and-Hold Cut Finance Down to Size?, by Bryan Caplan

My question: Suppose buy-and-hold investment strategies were near-universal. To be more specific, suppose 90% of all investment dollars were used to robotically purchase the market basket, then hold these assets until retirement. In this scenario, would the finance sector dramatically shrink?

Intuitively, it seems like it should. The thick market for buy-and-hold dollars would drive management fees below index funds' already low rates. And if almost no one tries to time the market, it's very hard for sophisticated insiders to get rich. There aren't enough fools left for the "greater-fool" strategy to be amount to a large share of GDP. In such a world, it would be hard for the value-added of finance to exceed a few percent of GDP.

Of course, if you're the only active trader left in a buy-and-hold world, finance could be very lucrative indeed. Just adjust your portfolio every morning when you read the newspaper and you'll clean up. But in my scenario, there are still plenty of competing active traders. They only control 10% of the dollars. But that leaves an army of financial sophisticates competing to fleece a relatively small pool of suckers.

Still, finance is not my area. Am I missing something important? If so, what?

P.S. I am well-aware that buy-and-hold was very rare in the 40s, 50s, and 60s. My conjecture is that finance's share of GDP skyrocketed despite the rise of buy-and-hold investing.

(3 COMMENTS)

November 12, 2013

Why Nations Fail: A Contrarian Take, by Bryan Caplan

...one of the most over-rated books I've ever read. It's fatallyI've yet to read Why Nations Fail. I'm not endorsing Smith's view, just sharing it. I will say, however, that several prominent economists have told me the same thing off the record. If you've read the book, please share your thoughts.

unrigorous, equally destitute of formal theory and econometrics. A naïve

view of the beneficence of democracy has long since been ripped apart

by public choice economics,

yet Acemoglu and Robinson revive it in the crudest form. People good,

elites bad. The book is somewhat persuasive via selective anecdotes if

you're willing to swallow its bizarre terminology, e.g., "inclusive

economic institutions" means protection of property rights, even though

property rights consist precisely in the right to exclude

others. All in all, I tend to think development economics peaked with

the empirical work of Jeffery Sachs in the 1990s, and it's been downhill

from there. Daron Acemoglu, in particular, has been a disaster for the

field. Honest empirical work on the democracy => growth causal link

suggests that the effect is basically nil.

But Acemoglu and Robinson's tendentiously fact-packed and conceptually

confusing tome has given development economists a pretext for taking a

more politically correct view.

(16 COMMENTS)

Unz Debate Analysis, by Bryan Caplan

(5 COMMENTS)

November 11, 2013

The Learning of the Wise, by Bryan Caplan

Now, you know, I'm laboring under a disadvantage in this debate because not only am I not a trained economist, I've never even taken a class in economics.The subtext is that Unz had better things to do than study yet another dubious subject. Many of my fellow economists would have jumped on his admission: "Unz begins by telling us that he knows nothing about economics - and then proceeds to prove it." But we economists should be more circumspect. Most of us ignore psychology, sociology, political science, history, education, philosophy and other subject matters relevant to our research. Some economists even revel in their ignorance; they can't pronounce the words "psychology" or "sociology" without scare quotes or sneer italics.

I've never even opened an economics textbook. I personally don't claim to really understand most economics. I'm not convinced everybody else understands economics that well either.

If pressed, most of these monodisciplinary economists would echo Unz: They don't study other subjects because their time is valuable, and the expected value of broadening their horizons is low. If other subjects had useful lessons to teach, economists would have already heard about them, right?

The obvious retort to such economists is: Do psychologists and sociologists have little learn from us? Every self-respecting economist must respond, "Bite your tongue; psychologists and sociologists have plenty to learn from economics." Once you admit that every field other than economics suffers from complacent groupthink, though, you really have to ask yourself, "Is economics any better?"

How would you find out? There are two obvious routes.

1. Seek out other economists who have seriously explored other fields. Yes, this suffers from selection bias - the economists who seriously explore other fields tend to be sympathetic to those fields. But such explorers remain useful guides. When you visit France, you want the author of your tourist book to be a Francophile.

2. See for yourself. Branch out to other subjects and see what you learn.

My claim: Both of these routes will quickly reveal ideas worthy of your consideration. Forty hours of reading - one week's work - will suffice. You'll encounter a lot of junk along the way. But you won't return to your intellectual home territory empty-handed. You will learn a lot even if you study subjects that seem phony and corrupt. Why? Because in the midst of phoniness and corruption, there are always dissident voices eager to speak out. Seek them and you shall find them. Once you give the dissidents a fair hearing, of course, you may start to see their targets in a more sympathetic light.

Anyone can say, "I never studied X because I wasn't convinced it would be worth my time." If someone genuinely seeks wisdom, though, they will set a much lower bar. Like: "I studied X because I wasn't convinced that it wasn't worth my time." Or: "I studied X because I thought there was a 10% chance X was right." Or: "I studied X because I was mortally afraid of overlooking whatever nuggets of truth X contains." If you really want to understand the world, you have to value your time less and your learning more. Study every subject that seems vaguely relevant. If a field has a bad reputation, see for yourself whether its reputation is deserved. And even if a field deserves its bad reputation, seek out honorable exceptions.

Should everyone adopt this demanding standards? Of course not. But if you're a consumer of ideas, you need not settle for thinkers who proudly declare that they have

better things to do than become deeply knowledgeable about the topics they

discuss. Wisdom does not come cheap, but the marketplace of ideas is full of thinkers who eagerly pay the full price. Such thinkers will often freely admit that they've spent years of their lives studying ideas of little value. (I know I have!) If you're a consumer of ideas, however, you shouldn't worry about how much time the wise have wasted, but how much the wise have learned.

(13 COMMENTS)

November 5, 2013

The Decline of Creative Destruction, by Bryan Caplan

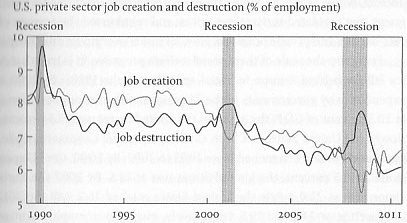

At first glance, this confirms a quarter-century of steadily declining creative destruction - falling job creation and job destruction. On closer look, though, there was little trend until the small recession of the early 2000s. Since then, however, creative destruction has relentlessly fallen.

Striking fact: The rate of job destruction during the Great Recession used to be perfectly normal! We experienced it as a calamity because job creation not only kept falling, but dipped below expectations.

Anyone seen this diagram over a longer time horizon? For other countries? Inquiring minds want to know.

(19 COMMENTS)

November 4, 2013

Play and Exit, by Bryan Caplan

Lesson 1: To keep the game going, you have to keep everyone happy. The most fundamental freedom in all true play is the freedom to quit. In an informal game, nobody is forced to stay, and there are no coaches, parents, or other adults to disappoint if you quit. The game can continue only as long as a sufficient number of players choose to continue. Therefore, everyone must do his or her share to keep the other players happy, including the players on the other team.Play, in short, is kids' earliest encounter with the sacred principle, "If you don't like it, you can quit." And in play as in work, the right to quit has a huge influence on behavior even though the right is rarely exercised. Under normal circumstances, the mere threat to quit is enough to elicit civilized behavior from all participants.

This means that you show certain restraints in an informal game beyond those dictated by the stated rules, which derive instead from your understanding of each player's needs. You don't run full force into second base if the second baseman is smaller than you and might get hurt, even though it might be considered good strategy in Little League (where, in fact, a coach might scold you for not running as hard as possible). This attitude is why children are injured less frequently in informal games than in formal sports, despite parents' beliefs that adult-directed sports are safer. [1] If you are pitching, you pitch softly to little Johnny, because you know he can't hit your fastball... But when big, experienced Jerome is up, you throw your best stuff, not just because you want to get him out but because anything less would be insulting to him...

To be a good player of informal sports you can't blindly follow rules. Rather, you have to see from others' perspectives, to understand what others want and provide at least some of that for them. If you fail, you will be left alone. In the informal game, keeping your playmates happy is far more important than winning, and that's true in life as well.

(7 COMMENTS)

Vivek Wadhwa Responds, by Bryan Caplan

Bryan, feel free to post what

you like. I am in favor of legalizing all the workers who are in the US and

bringing in people that the country needs. I do not advocate open borders. I

believe in exporting prosperity, not importing poverty.You can blame me for the defeat,

but the consensus at the event by the people I spoke to was that what lost the

day was the image that our opponents planted of 20 million Haitians begging on

the streets of NYC. You didn't refute that or answer the question about how we

would provide medical assistance and schooling to these people when we can't

even look after our existing population. No one--including me--bought your

analogies or arguments. You were smug, arrogant, and resorted to silly

analogies. Your views on the minimum wage show that you are out of touch with

the hardships that people in this country suffer.

Also you would not open up your

home doors to the poor or be happy if someone with lesser skills was given your

job because they were ready to work longer hours and accept a lower salary. It

is easy to preach.

Please do add these comments to

your post.

Regards,

Vivek

(89 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers