Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 155

February 5, 2014

AMA Highlights, by Bryan Caplan

Hi Bryan,

There has been a lot of talk online recently on the merits of a Basic

Income Guaranty or Negative Income Tax. I have two questions:

Would you endorse something like a BIG?Why do you think the idea is so appealing to both libertarians and socialists? Should proponents in each group be worried that the idea appeals to their ideological opponents?[-]BryanCaplan[S]As a replacement for the status quo, maybe. As an addition, no.

Libertarians like it because they think it will be a replacement. Socialists like it because they think it will be an addition.

And:

Bryan,

What do you think about the viability of Bitcoin as money? If Bitcoin,

or some crypto-currency, gets widely adopted as money what do you see as

the most important economic ramifications?

It's

done 10x better than I expected, but I still don't expect it to be more

than a niche financial instrument. It's long been noted that people

around the world continue using their national currencies even in the

face of 20 or 30% inflation because national currencies are more

convenient and focal. Also, I expect regulators to crack down if

Bitcoin becomes much of a threat.

But hopefully I'm wrong!

And:

You have written:

Economists' consensus estimate is that open borders would roughly

double world GDP, enough to virtually eliminate global poverty (Clemens

2011).

This was huge news to me and I completely agree with your assessment:

What I can't understand is indifference to the mind-boggling potential benefits of immigration. The knowledge that we're sitting on an ocean of talent

should haunt great minds day and night. They should pace around their

offices telling themselves, "There's got to be a way to unlock these

wasted trillions of dollars of human potential. There's just got to be a

way."

My question is: Are there other libertarian policies

that would result in similarly-massive benefits as open borders if

implemented? If so, what are they?

After

open borders, the biggest policy change would be for Third World

countries to fully open their doors to international investment. Work

by van Reenen and many others shows that multinational corps in the 3rd

World are vastly better-run than local firms. If multinationals could

freely compete, they would quickly raise productivity. Back of the

envelope calculate is that if all firms on earth were managed at

multinational levels, global GDP would go up by 25-50%. Most of the

benefit, of course, would be in the Third World.

And:

Thank you for doing this AMA!

Do you believe that philosophy plays an important role in economics? For instance, you have promoted Michael Huemer's The Problem of Political Authority. Do the ethical arguments put forward by Huemer have any bearing on your work in or your views regarding economics?

[-]BryanCaplan[S]Every

economist who gives policy advise is implicitly relying on philosophy.

Unfortunately, most economists want to rely on philosophy without

really reflecting on it, so they're usually just crude utilitarians

(with a heavy bias toward the status quo and democratic fundamentalism).For my own part, I start with a strong presumption of liberty, but

admit that we should override this presumption when the benefits of

violating liberty heavily outweigh the costs. (See http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2010/08/how_far_does_th.html) So economics ends up being a vital servant of political philosophy, but nothing more.

And:

(8 COMMENTS)With

the drought in Southern California is it possible the state is over

populated? Meaning we have to halt immigration into the south west?

No. Just raise the price of water!

February 4, 2014

Diasporas, Swamping, and Open Borders Abolitionism, by Bryan Caplan

The third big thing we know [about immigration] is that the costs of migration are greatly eased by the presence in the host country of a diaspora from the country of origin. The costs of migration fall as the size of the network of immigrants who are already settled increases. So the rate of migration is determined by the width of the [income] gap, the level of income in countries of origin, and the size of the diaspora. The relationship is not additive but multiplicative: a wide gap but a small diaspora, and a small gap with with a large diaspora, will both only generate a trickle of migration. Big flows depend upon a wide gap interacting with a large diaspora and an adequate level of income in countries of origin.Diasporas scare Collier. Why? Because diasporas have the potential to snowball. In economic jargon, there "may be no equilibrium."

For a given income gap, migration would only cease to accelerate if the diaspora stopped growing. Since migration is constantly adding to the diaspora, it will only cease to grow if there is some offsetting process reducing the size of the diaspora.Since Collier is a nationalist at heart, the prospect of snowballing diasporas horrifies him. If everyone in Sudan moves to the U.S., it dilutes American identity - and eventually destroys Sudanese identity.

If you're a pragmatic cosmopolitan, however, Collier's diaspora story makes open borders abolitionism suddenly look reasonable. If immigration were based solely on income gaps, any country that opened its borders would be swiftly swamped by hundreds of millions of migrants. The cost of adhering strictly to the principle of free migration could be high for the native population. Maybe everything will be fine in the long run. But in the short run, there will be shantytowns, begging, poor sanitation, and much ugliness.

On Collier's account, in contrast, flinging the borders wide open wouldn't lead to a mass exodus. Instead, migration would start small, then gradually accelerate to very high levels. First a few adventurous Sudanese come. Then they write home, attracting a larger second wave. This in turn gives courage to a still larger third wave. Eventually, most of Sudan migrates; diasporas feed on themselves. But the process takes decades, giving U.S. business plenty of time to prepare for all the new customers and employees. In the end, the migrants' remittances and repatriates turn their depopulated Old Country into a quaint tourist and retirement community like Puerto Rico.

Nationalists will rankle at this picture. Nations die in slow motion, and open borders abolitionists rejoice? But I fail to see the problem. "Nations dying" is merely a metaphor. People living - and dying - in wretched poverty is a harsh reality. Open borders saves the people and lets the metaphors fend for themselves.

(14 COMMENTS)

Ask Me Anything Tonight, by Bryan Caplan

HT: Michael Tontchev for setting this up.

P.S. Please post your questions on reddit, not the EconLog comments.

(8 COMMENTS)

February 3, 2014

Obituary Hypothetical: What If Mengele Cured Cancer?, by Bryan Caplan

Twins were subjected to weekly examinations and measurements of their physical attributes by Mengele or one of his assistants.

Experiments performed by Mengele on twins included unnecessary

amputation of limbs, intentionally infecting one twin with typhus or

other diseases, and transfusing the blood of one twin into the other.

Many of the victims died while undergoing these procedures. After an experiment was over, the twins were sometimes killed and their bodies dissected.

Nyiszli recalled one occasion where Mengele personally killed fourteen

twins in one night via a chloroform injection to the heart. If one twin died of disease, Mengele killed the other so that comparative post-mortem reports could be prepared.

Mengele's experiments with eyes included attempts to change eye color

by injecting chemicals into the eyes of living subjects and killing

people with heterochromatic eyes so that the eyes could be removed and

sent to Berlin for study.

His experiments on dwarfs and people with physical abnormalities

included taking physical measurements, drawing blood, extracting healthy

teeth, and treatment with unnecessary drugs and X-rays.

Many of the victims were sent to the gas chambers after about two

weeks, and their skeletons were sent to Berlin for further study. Mengele sought out pregnant women, on whom he would perform experiments before sending them to the gas chambers. Witness Vera Alexander described how he sewed two Gypsy twins together back to back in an attempt to create conjoined twins. The children died of gangrene after several days of suffering. [footnotes omitted]

After World War II, Mengele escaped to South America. He died a free man in 1979. My hypothetical: Suppose, contrary to fact, that Mengele's experiments led straight to a cure for cancer. How should his obituary be revised?

In my view, barely at all. An obituary is a prime opportunity to fulfill Lord Acton's maxim to "suffer no man and no cause to escape the undying penalty which history has the power to inflict on wrong." A man like Mengele, who repeatedly tortured and murdered innocents, is beyond redemption. Any upside of his atrocities should be (a) mentioned only after enumerating his monstrous crimes, and (b) framed ironically. I.e., "Through a strange quirk of fate, the Nazi doctor who spend his career taking innocent lives indirectly saved millions."

So what? Most obituaries for world leaders take the opposite approach. Instead of vetting their records for capital crimes, and putting any such crimes front and center, the typical piece focuses on leader's "legacies." Thus, most obituaries for Deng Xiaoping emphasize that he dismantled Maoism and put China on the path of rapid development. Never mind the half century Deng spent in the Communist Party as Mao's loyal and murderous henchman. (And even if you discount this as Deng's misspent youth and middle age, what about his key role in the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989?!) I can see an obituary saying, "Deng was less evil than Mao, the greatest mass murderer of the 20th century." But to affirmatively praise Deng because, in his old age, he "only" killed people who defied his authority?

You could object that, by my standards, almost every world leader is a monster. That's not far from the truth. But either way, you've got to bite a bullet. You can condemn almost every world leader for their crimes - or condition your condemnation of Mengele on the medical usefulness of his experiments.

(17 COMMENTS)

February 2, 2014

Meet James Schneider, by Bryan Caplan

James is a man of many talents. He was a math whiz even by Princeton standards, so we often came to him, hat in hand, for help with our homework. But I was much more impressed by his voracious reading. James reads it all, especially economics, history, medicine, psychology, biography, and literature. He has self-taught himself French and Spanish - and often refuses to read popular English novels except in translation. Years after graduation, I learned that James had written several unpublished novels. After I convinced him to share his drafts, his novels - often centered in Princeton - became some of my personal favorites. I often quote this passage from his Flight Into L.A. to poetically illustrate my Iron Laws of Pedagogy:

He [an art history professor] rambled on about how Rembrandt captured the "soul state" of each of his figures, and then he made an analogy to Beethoven's music. He extended the analogy for several minutes not realizing that nobody in the class knew anything about Beethoven. Three weeks into summer vacation most students won't remember anything about Rembrandt.During graduate school, James focused on applied economic theory. Since then, however, he has worked in two Real World industries: economic consulting and health insurance. As a result, James has transformed himself into the single best-informed health economist I have ever met. He knows theory, he knows empirical research, and he knows the on-the-ground details of how the U.S. health industry actually works. He is almost done with his first non-fiction book, The Seven Deadly Sins. The topic: behavioral health economics. I'll save the contents for him to blog, but I claim a little credit for inspiring his chapter ("Pride") on climbing Mount Everest.

James, like me, is a tireless debater. While we are of one mind on many issues, you'd never know it from listening to us converse. I could spend several posts summarizing our recurring disagreements, so let me just hit the highlights.

We've spent years debating Robin Hanson's medical skepticism. Though Jim is well-aware that medicine is often overrated, he's a lot more optimistic than Robin about medicine's contribution to human well-being. We've spent years debating consequentialism. While James is no bullet-biter, he's a lot more consequentialist than I am. At least he's a moral realist, though!We've spent years debating the Szaszian view of mental illness. James may demur, but I think I've gradually pulled him quite a ways in my direction.We've spent years debating the value of mathematical economics. In graduate school, you could chalk this up to the fact that James was great at math econ and I wasn't. But he (almost) never pulled rank on me. Instead, he insisted that I failed to appreciate pure theory's full intellectual payoff.

We've spent years debating the role of psychology in economics. I take The Seven Deadly Sins as a major concession to my position, but James may interpret matters differently...

For the past twenty one years, James has been one of the great joys in my life. He's one of those old-fashioned scholars who's read so widely and thought so deeply he can improve your thinking on almost any topic. I've often felt disappointed that he isn't my full-time colleague. The good news, though, is that after seventeen years, we're colleagues again. So please join me in welcoming EconLog's latest guest blogger. Prepare to be enlightened, challenged, and amused.

(3 COMMENTS)

January 31, 2014

Gochenour-Nowrasteh on the Political Externalities of Immigration, by Bryan Caplan

The latest Cato working paper from my co-author Zachary Gochenour and my former student Alex Nowrasteh concludes that - at least in the United States - both sides are wrong. Yes, most of the European evidence supports the view that immigration paves the way for austerity:

[I]ncreasing diversity could be a concern for the political supporters of the welfare states of Europe: in 2000, over 50 percent of the European population was concerned about immigrant abuse of the welfare, with those living in nations with higher social expenditures convinced that immigrants are more likely to abuse welfare [7]. A Norwegian survey about the political feasibility of introducing a minimum income found that 66 percent of Norwegians initially favored the scheme. However, merely mentioning that non-Norwegians residing in the country would receive the same benefi�ts reduced support for the program to only 45 percent [5]. In Sweden, increased immigrant population share led to less support for redistribution among native Swedes according to surveys conducted every election year by the Swedish National Election Studies Program [12]. Furthermore, some authors have suggested that immigration has given new life to political parties that bundle anti-welfare policies with xenophobic policies [18]. [see the paper for cites]If you look at the fifty United States, however, immigration has no detectable effect on TANF/AFCD, K-12 education, or Medicaid spending. This is true for both per capita and total spending:

These �findings are consistent and robust. No e�ffect was found for immigrant population share or diversity on TANF benefi�ts levels available per family of bene�ficiaries or the total spent on the program. Likewise, there was no e�ffect for total or per-pupil K-12 spending or for total or per-capita Medicaid spending. Therefore, these �findings lend no support to the idea that immigration or the resulting immigration driven increases in diversity is linked to higher public spending by any of these measures.You might think the TANF result is driven by immigrants long eligibility lag, but that's not it:

Limited TANF eligibility for immigrants could help explain the lack of native reaction to increased immigration and diversity. However, data from the GSS suggests that the median American thinks the government provides too much assistance to immigrants. In reality, the programs have stricter eligibility requirements than before: the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation (welfare reform) and Illegal Immigrant Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Acts (IIRIRA) of 1996 restricted non-citizen eligibility for TANF. Prior to 1996, non-citizens were generally eligible for the same welfare benefi�ts as citizens but welfare reform and the IIRIRA barred TANF for new immigrants for �five years after their entry. After the �five year bar, states were allowed discretion in allowing non-citizens access to TANF. As of 2010, 34 states and Washington, D.C. allowed lawful permanent residents who have been in the U.S. for more than �five years to draw on TANF. Many states restored portions of the welfare bene�fits limited by welfare reform. Because of these laws and a diminishing poverty rate among immigrants, 4 percent of immigrants were using TANF in 1995 but only 1 percent were in 2009 [36]. [see the paper for cites]What's going on? The simplest story is that immigration has two roughly offsetting political effects: Although immigrant voters are a little more pro-welfare state, their very presence makes native voters a little more anti-welfare state. Gochenour-Nowrasteh explore other stories at the end of the paper. Read the whole thing.

P.S. If your economics or public policy department wants to hire an excellent assistant professor, Gochenour is on the market this year.

(15 COMMENTS)

January 29, 2014

I'm Too Busy Fighting Tyranny to Feed My Family, by Bryan Caplan

After a while, though, you start to wonder about John. How does he hold down a job? You soon discover that John lost his job years ago - and hasn't bothered to find another. Anytime John gets a little money, he spends it on bus tickets, computer upgrades, and other activist paraphernalia. As a result, his children are hungry and ragged. When criticized, John angrily responds, "I'm too busy fighting tyranny to feed my family."

I think you'll agree that John is a terrible human being. Why? Because his priorities are demented. Political activism is a luxury. Before you engage in this luxury, you must satisfy your basic responsibilities to provide for yourself and your family.

Now if John's activism had a high probability of drastically changing the world for the better, his behavior might be defensible. Maybe it was OK for von Stauffenberg to endanger the lives of his five children to overthrow Hitler and end World War II. But if John is merely a run-of-the-mill political junkie, one voice out of millions, letting his children go hungry for the cause is inexcusable.

Why bring this up? When I point out that would-be immigrants are trying to save themselves and their families from hellish Third World conditions, my critics often respond, "They ought to stay home and try to fix their broken political systems!" In other words, my critics are admonishing the global poor to heed the example of John the feckless activist.

Thus, suppose Jacques the desperate Haitian father has an opportunity to escape to Miami, where he can shine shoes and send money home to feed his kids. Instead, he chooses to let his kids go hungry so he stays in Port-au-Prince and fights tyranny with political leaflets and soapbox speeches. Noble? No more than John. The righteous man knows that meeting his family responsibilities is more important than playing Don Quixote.

The case against activism is even stronger if, as usual, the activist is deeply confused. Knowing that your country's policies are awful doesn't magically tell you how to improve them. In the real world, activists who successfully "stand up to tyranny" often end up making bad situations worse. Indeed, triumphant activists routinely give new meaning to the word "tyranny." See Lenin, Hitler, and Mao for starters.

When critics of immigration urge desperately poor people to stay home and fix their political systems, they're doubly obtuse. Not only are they urging people to neglect their basic responsibilities in favor of the luxury of political activism. They're urging people who know virtually nothing about policy or politics to "get involved" - and quite possibly make their countries even worse.

What should humble people born into Third World misery do? Stay the course. Do your best to provide for your family. Keep trying to escape to the First World and get the best job you can. Remember that activism is a luxury if you know what you're talking about - and a pestilence if you don't. The people who follow this advice aren't just fulfilling their basic responsibilities. They're doing far more to improve their homelands than the vast majority of political junkies ever will.

(2 COMMENTS)

Self-Harm is a Luxury, by Bryan Caplan

Differences in prices or in response to prices are a second potential reason for education-related differences in health behaviors. This shows up most clearly in behaviors involving the medical system. In surveys, lower income people regularly report that time and money are major impediments to seeking medical care. Even given health insurance, out-of-pocket costs may be greater for the poor than for the rich--for example, their insurance might be less generous. Time prices to access care may be higher as well, if for example, travel time is higher for the less educated.In other words, self-harm is a luxury. I've made parallel points for crime and staying single before.

A consideration of the behaviors in Table 1 suggests that price differences are unlikely to be the major explanation, however. While interacting with medical care or joining a gym costs money, other health-promoting behaviors save money: smoking, drinking, and overeating all cost more than their health-improving alternatives. It is possible that the better educated are more responsive to price than the less educated, explaining why they smoke less and are less obese. But that would not explain the findings for other behaviors which are costly but still show a favorable education gradient: having a radon detector or a smoke detector, for example. Still other behaviors have essentially no money or time cost, but still display very strong gradients: wearing a seat belt, for example.

More detailed analysis of the cigarette example shows that consideration of prices exacerbates the education differences. A number of studies show that less educated people have more elastic cigarette demand than do better educated people. Prices of cigarettes have increased substantially over time. Gruber (2001) shows that cigarette prices more than doubled in real terms between 1954 and 1999; counting the payments from tobacco companies to state governments enacted as part of the Master Settlement Agreement, real cigarette taxes are now at their highest level in the post-war era. Yet over the same time period, smoking rates among the better educated fell more than half, and smoking rates among the less educated declined by only one-third. For these reasons, we do not attribute any of the education gradient in health behaviors to prices. [footnotes omitted]

(1 COMMENTS)

January 28, 2014

In Praise of Passivity, by Bryan Caplan

Voters, activists, and political leaders of the present day are in the position of medieval doctors. They hold simple, prescientific theories about the workings of society and the causes of social problems, from which they derive a variety of remedies-almost all of which prove either ineffectual or harmful. Society is a complex mechanism whose repair, if possible at all, would require a precise and detailed understanding of a kind that no one today possesses. Unsatisfying as it may seem, the wisest course for political agents is often simply to stop trying to solve society's problems.Why doesn't this support the status quo? Because "trying to solve society's problems" is the status quo! This orientation is both counter-productive and immoral:

Now, one might think that, if we were completely ignorant, our policies would be as likely to increase as to reduce the problem; but as long as we have some relevant knowledge and understanding, and we are aiming at a reduction in the problem, we should be at least slightly more likely to alleviate the problem than to exacerbate it. Thus, even if the government does not know what will solve or alleviate the problem, the government can and should at least make an educated guess, and then implement that guess.As always, Huemer carefully qualifies his position, and anticipates, refines, and replies to all the obvious criticisms. Still, he could have made his case more concisely. His position is essentially a generalization of my case for pacifism. My postcard version:

There are at least four reasons why this is wrong. First, any government policy that imposes requirements or prohibitions on citizens automatically has certain costs. One cost is the reduction of citizens' freedom. Another is the suffering on the part of those who violate the law and are subsequently punished by the legal system. A third is the monetary cost involved in implementing the policy. Thus, in the case of laws against recreational drug use, individuals are denied the freedom to do as they wish with their own bodies; those who violate the laws and are caught suffer for months or years in prison; and all taxpayers suffer the costs of enforcing the drug laws.

Second, there is a kind of moral presumption against coercive interventions. Laws are commands backed up by threats of coercive imposition of harm on those who disobey them. Harmful coercion against an individual generally requires some clear justification. One is not justified in coercively harming a person on the grounds that the person has violated a command that one merely guesses has some social benefit. If it is not reasonably clear that the expected benefits of a policy significantly outweigh the expected costs, then one cannot justly use force to impose that policy on the rest of society.

A third, related point is that when the state actively intervenes in society-for example, by issuing commands and coercively harming those who disobey its commands-the state then becomes responsible for any resulting harms, in a way that the state would not be responsible for harms that it merely (through lack of knowledge) fails to prevent. Imagine that I see a woman at a bus stop opening a bottle of pills, obviously about to take one. Before I decide to snatch the pills away from her and throw them into the sewer drain, I had better be very certain that the pills are actually something harmful. If it turns out that I have taken away a medication that the woman needed to forestall a heart attack, I will be responsible for the results. On the other hand, if, due to uncertainty as to the nature of the drugs, I decide to leave the woman alone, and it later turns out that she was swallowing poison, I will not thereby be responsible for her death. For this reason, intervention faces a higher burden of proof than nonintervention. Similarly, if, due to uncertainty as to the effects of anti-drug laws, the government were to simply leave drug users alone, the government would not thereby be responsible for the harms that drug users inflict upon themselves. But if the government maintains anti-drug laws, and these laws impose enormous cost on society, the government is morally responsible for those costs.

Fourth and finally, a policy made under conditions of extreme ignorance is not equally likely to be beneficial as harmful; it is much more likely to be harmful...

1. The short-run costs of war are clearly high, and are largely borne by innocents.

2. The long-run benefits of war are highly uncertain.

3. It is wrong to impose high costs on innocents unless the benefits are highly likely to greatly outweigh the costs.

Huemer could have just generalized my argument. Something like:

1. The short-run costs of government coercion are clearly high, and are largely borne by innocents.

2. The long-run benefits of government coercion are highly uncertain.

3. It is wrong to impose high costs on innocents unless the benefits are highly likely to greatly outweigh the costs.

Read the whole piece, and don't miss the quotable conclusion. Yes, "Marx's failure to improve society should have been about as surprising as the failure of George Washington's doctors to cure his infection by draining his blood."

(0 COMMENTS)

January 27, 2014

Pritchett on Private vs. Government Schools, by Bryan Caplan

Whereas formerly only the elite may have gone to private schools, there has been a massive proliferation of private schools, especially in Asia and Africa. These budget-level private schools are producing better learning outcomes, often substantially better, than publicly controlled schools - even for the same students - and often at much lower costs.But:

This isn't to say that across the board, private schooling is better than that available in government-run schools; in general, the evidence that private schools outperform government schools in well-functioning systems is weak. In the United States, where there has been the opportunity to do the most rigorous experimental studies, most researchers agree that the private sector edge in learning is nothing like a full effect size [1 standard deviation], almost certainly not even a tenth of an effect size, and some legitimately dispute whether the private sector causal impact is even positive.Yet the fact remains:

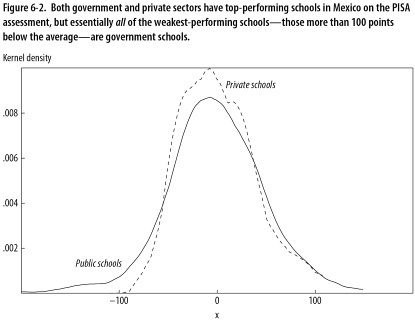

Broader than just the success of specific interventions inside government schools is the observation that even in low-performing government systems one finds excellent schools, but also, even nearby and even operating under apparently exactly the same conditions, terrible schools... The problem is not that government schools cannot succeed, for in nearly all developing countries some of the very best schools are government schools. The problem is, as the LEAPS study authors emphasize, "when government schools fail, they fail completely"...Case in point: In Mexico, "essentially all of the weakest-performing schools - those more than 100 points [2 standard deviations] below the average - are government schools."

My main objection: I strongly suspect that private schools have a big cost advantage over public schools even when they don't have much of a learning advantage. This effect is easy to miss in the First World because there is relatively little demand for cheap adequate private education when there's free adequate government education. But religious schools strongly suggest that private education for the masses can be provided at WalMart prices. And if parents were paying their own money, WalMart pricing would probably dominate.

(9 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers