Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 152

March 13, 2014

1896: Immigration and The Atlantic, by Bryan Caplan

In 2013, The Atlantic sympathetically profiled the open borders movement. Quite a change from this piece the magazine ran in 1896, when nearly open borders still prevailed. The author, Francis Walker, begins with admirable clarity:

1. "Complete exhaustion of the free public lands."

(0 COMMENTS)

When we speak of the restriction of immigration, at the present time, we haveWalker's view, perhaps surprisingly, is that open borders continued to enjoy popular support:

not in mind measures undertaken for the purpose of straining out from the vast

throngs of foreigners arriving at our ports a few hundreds, or possibly

thousands of persons, deaf, dumb, blind, idiotic, insane, pauper, or criminal,

who might otherwise become a hopeless burden upon the country, perhaps even an

active source of mischief...

What is

proposed is, not to keep out some hundreds, or possibly thousands of persons,

against whom lie specific objections like those above indicated, but to exclude

perhaps hundreds of thousands, the great majority of whom would be subject to

no individual objections; who, on the contrary, might fairly be expected to

earn their living here in this new country, at least up to the standard known

to them at home, and probably much more. The question to-day is not of

preventing the wards of our almshouses, our insane asylums, and our jails from

being stuffed to repletion by new arrivals from Europe; but of protecting the

American rate of wages, the American standard of living, and the quality of

American citizenship from degradation through the tumultuous access of vast

throngs of ignorant and brutalized peasantry from the countries of eastern and

southern Europe.

The first thing to be said respecting any serious proposition importantly toFriends of immigration often point out that nativists today make the same arguments they made a century ago. Nativists typically respond that times have changed. Walker shows that even the "times have changed" argument is over a century old:

restrict immigration into the United States is, that such a proposition

necessarily and properly encounters a high degree of incredulity, arising from

the traditions of our country. From the beginning, it has been the policy of

the United States, both officially and according to the prevailing sentiment of

our people, to tolerate, to welcome, and to encourage immigration, without

qualification and without discrimination. For generations, it was the settled

opinion of our people, which found no challenge anywhere, that immigration was

a source of both strength and wealth. Not only was it thought unnecessary

carefully to scrutinize foreign arrivals at our ports, but the figures of any

exceptionally large immigration were greeted with noisy gratulation.

It is, therefore, natural to ask, Is it possible that our fathersWhat exactly has changed?

and our grandfathers were so far wrong in this matter? Is it not, the rather,

probable that the present anxiety and apprehension on the subject are due to

transient causes or to distinctly false opinions, prejudicing the public mind?

The challenge which current proposals for the restriction of immigration thus

encounter is a perfectly legitimate one, and creates a presumption which their

advocates are bound to deal with. Is it, however, necessarily true that if our

fathers and grandfathers were right in their view of immigration in their own

time, those who advocate the restriction of immigration to-day must be in the

wrong? Does it not sometimes happen, in the course of national development,

that great and permanent changes in condition require corresponding changes of

opinion and of policy?

1. "Complete exhaustion of the free public lands."

Fifty years ago, thirty years ago, vast tracts of2. Falling agricultural prices.

arable laud were open to every person arriving on our shores, under the

Preemption Act, or later, the Homestead Act. A good farm of one hundred and

sixty acres could be had at the minimum price of $1.25 an acre, or for merely

the fees of registration. Under these circumstances it was a very simple matter

to dispose of a large immigration. To-day there is not a good farm within the

limits of the United States which is to be had under either of these acts... The immigrant must

now buy his farm from a second hand, and he must pay the price which the value

of the land for agricultural purposes determines. In the case of ninety-five

out of a hundred immigrants, this necessity puts an immediate occupation of the

soil out of the question.

There has been a3. The rise of unions.

great reduction in the cost of producing crops in some favored regions where

steam-ploughs and steam-reaping, steam-threshing, and steam-sacking machines

can be employed; but there has been no reduction in the cost of producing crops

upon the ordinary American farm at all corresponding to the reduction in the

price of the produce. It is a necessary consequence of this that the ability to

employ a large number of uneducated and unskilled hands in agriculture has

greatly diminished.

Still a third cause which may be indicated, perhaps more important than eitherWalker predictably paints open borders as a form of charity:

of those thus far mentioned, is found in the fact that we have now a labor

problem... There is no country of Europe which has not for a long

time had a labor problem; that is, which has not so largely exploited its own

natural resources, and which has not a labor supply so nearly meeting the

demands of the market at their fullest, that hard times and periods of

industrial depression have brought a serious strain through extensive

non-employment of labor. From this evil condition we have, until recently,

happily been free. During the last few years, however, we have ourselves come

under the shadow of this evil, in spite of our magnificent natural resources.

For it is never to be forgotten that self-defense is the first law of natureAnd he charmingly ends with intra-white racism:

and of nations. If that man who careth not for his own household is worse than

an infidel, the nation which permits its institutions to be endangered by any

cause which can fairly be removed is guilty not less in Christian than in

natural law. Charity begins at home; and while the people of the United States

have gladly offered an asylum to millions upon millions of the distressed and

unfortunate of other lands and climes, they have no right to carry their

hospitality one step beyond the line where American institutions, the American

rate of wages, the American standard of living, are brought into serious peril.

The problems which so sternly confront us to-day areThe most striking feature of the essay: It moves back and forth between sounding totally dated and entirely modern. All the specific economic conditions - the focus on land, farming, and unions - sound totally dated. Yet the fundamental philosophy - the misanthropy, national socialism, the effort to paint immigrants as charity cases - sound entirely modern. It's almost as if immigration restriction - then as now - is merely a solution in search of a problem.

serious enough without being complicated and aggravated by the addition of some

millions of Hungarians, Bohemians, Poles, south Italians, and Russian Jews.

(0 COMMENTS)

Published on March 13, 2014 20:42

March 12, 2014

Being Sendhil Mullainathan, by Bryan Caplan

Harvard's Sendhil Mullainathan has a remarkable life story. From a profile in Forbes:

great life."

But despite Sendhil's early years in a small Indian village traveling by oxcart, his essay never mentions the global poor. They're undeniably part of "everyone." Yet First World governments do nothing to "ensure that they have a fair opportunity to find a great life." In fact, First World governments go out of their way to forbid the global poor to accept job offers from willing First World employers. The predictable result: The global poor earn a tiny fraction of their true value in the global marketplace.

Rather than mention the billions of people on Earth who have genuinely been denied a "fair opportunity to find a great life," Sendhil bemoans the fate of relatively poor Americans. Yet the only evidence he presents that relatively poor Americans lack fair opportunity is their low income and high incarceration rate.

Again, I find this hard to understand. If Sendhil described the plight of relatively poor Americans to his childhood friends in India, would they sympathize? I doubt it. Instead, they'd shake their heads and say, "They had the great fortune to be born in America, and this is what they do with their lives? Shame on them for squandering a golden opportunity."

I have enormous respect for what Sendhil has done with his life. He's certainly come a lot further than I have. Still, if I were him, I would have written a very different essay on inequality. Here is me, being Sendhil Mullainathan:

I moved to America when I was seven, but I'm still shocked by Americans' moral blindness. You overflow with high-sounding rhetoric about "equality of opportunity for all." You wring your hands, telling each other, "We've got to do more." The truth, though, is that the American government - like all First World governments - could greatly increase the opportunities of the truly poor by simply leaving them alone.

Billions of human beings on this planet are destitute. But most could swiftly escape poverty by moving to the First World and getting a job from a willing employer. Why don't they? Because it's illegal - and contrary to what you've heard, enforcement is draconian. When the truly poor try to solve their own problem, the American government calls them criminals. Talk about blaming the victim.

Some economists - like my colleague George Borjas - fret that mass low-skilled immigration will make life even harder for low-skilled Americans. The evidence is weaker than they claim. But even if they were right, I find it impossible to sympathize. Low-skilled Americans are wealthy by global standards. Not only can they legally work in one of the world's best job markets. Their incomes, education, and health care have been heavily subsidized, and they've been been shielded from global labor competition for a century. By any objective standard, they have fantastic opportunities. Unfortunately, they largely squander them.

To be fair, the War on Drugs has hit the American poor especially hard. We should end the drug war, and pardon everyone imprisoned for drug-related offenses. But don't kid yourselves. The main thing that stands between low-skilled Americans and success is a lack of the can-do spirit exemplified by immigrants - legal and illegal.

If Americans really believe in equality of opportunity, they must reverse their priorities. Their overriding priority should be ending their international version of the Jim Crow laws. Instead of focusing on doing more for relatively poor natives who fail to capitalize on their amazing opportunities, Americans should focus on doing less to absolutely poor foreigners whose opportunities - though improving - are abysmal. Frankly, we should put all petty domestic disputes aside until everyone is free to take a job anywhere.

Some will no doubt condemn me, an immigrant, for base ingratitude. America let my family in. I should reciprocate by supporting the long-standing choices of the American people.

I beg to differ. If America practiced the equality of opportunity it preaches, my family wouldn't have needed government permission to immigrate. We could have moved from India to America with the same freedom that Californians move to Nevada. Now that I'm here legally, I'm going to tell you the truth - not pander to nativist prejudices that could easily have trapped me in the Third World - and continue to trap billions today.

I love living in this country. It's not just the standard of living. On an individual level, most Americans are famously nice people. Collectively, though, their behavior is atrocious - and Americans with a "social conscience" are often even worse. We don't need a bigger, better War on Poverty to become a just society. We just need to stop requiring discrimination against all the people without the good fortune to be born here.

Needless to say, Sendhil Mullainathan bears no responsibility for what I wish he would say. But I really wish he would join me in saying it. In case I've changed his mind, Sunday is Open Borders Day...

(0 COMMENTS)

Given Sendhil's history, I was frankly surprised by his recent New York Times piece on inequality. His high-level principles are plausible enough: "We should try to ensure that everyone has a fair opportunity to find aBorn in a small farming village in India, Mullainathan lived there

for seven years while his father moved to the U.S. to go to graduate

school. On his fifth birthday, his father sent him a three-piece suit.

On the way, via oxcart, to have his photo taken, his uncle and

grandfather spent the whole time arguing about whether the vest went

over or under the jacket. In the photo a beaming Mullainathan proudly

wears the vest on top.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1980, Mullainathan left high school

without graduating and went to Clarkson University, and then on to

Cornell, where he took graduate-level courses in math and computer

science.

great life."

But despite Sendhil's early years in a small Indian village traveling by oxcart, his essay never mentions the global poor. They're undeniably part of "everyone." Yet First World governments do nothing to "ensure that they have a fair opportunity to find a great life." In fact, First World governments go out of their way to forbid the global poor to accept job offers from willing First World employers. The predictable result: The global poor earn a tiny fraction of their true value in the global marketplace.

Rather than mention the billions of people on Earth who have genuinely been denied a "fair opportunity to find a great life," Sendhil bemoans the fate of relatively poor Americans. Yet the only evidence he presents that relatively poor Americans lack fair opportunity is their low income and high incarceration rate.

Again, I find this hard to understand. If Sendhil described the plight of relatively poor Americans to his childhood friends in India, would they sympathize? I doubt it. Instead, they'd shake their heads and say, "They had the great fortune to be born in America, and this is what they do with their lives? Shame on them for squandering a golden opportunity."

I have enormous respect for what Sendhil has done with his life. He's certainly come a lot further than I have. Still, if I were him, I would have written a very different essay on inequality. Here is me, being Sendhil Mullainathan:

I moved to America when I was seven, but I'm still shocked by Americans' moral blindness. You overflow with high-sounding rhetoric about "equality of opportunity for all." You wring your hands, telling each other, "We've got to do more." The truth, though, is that the American government - like all First World governments - could greatly increase the opportunities of the truly poor by simply leaving them alone.

Billions of human beings on this planet are destitute. But most could swiftly escape poverty by moving to the First World and getting a job from a willing employer. Why don't they? Because it's illegal - and contrary to what you've heard, enforcement is draconian. When the truly poor try to solve their own problem, the American government calls them criminals. Talk about blaming the victim.

Some economists - like my colleague George Borjas - fret that mass low-skilled immigration will make life even harder for low-skilled Americans. The evidence is weaker than they claim. But even if they were right, I find it impossible to sympathize. Low-skilled Americans are wealthy by global standards. Not only can they legally work in one of the world's best job markets. Their incomes, education, and health care have been heavily subsidized, and they've been been shielded from global labor competition for a century. By any objective standard, they have fantastic opportunities. Unfortunately, they largely squander them.

To be fair, the War on Drugs has hit the American poor especially hard. We should end the drug war, and pardon everyone imprisoned for drug-related offenses. But don't kid yourselves. The main thing that stands between low-skilled Americans and success is a lack of the can-do spirit exemplified by immigrants - legal and illegal.

If Americans really believe in equality of opportunity, they must reverse their priorities. Their overriding priority should be ending their international version of the Jim Crow laws. Instead of focusing on doing more for relatively poor natives who fail to capitalize on their amazing opportunities, Americans should focus on doing less to absolutely poor foreigners whose opportunities - though improving - are abysmal. Frankly, we should put all petty domestic disputes aside until everyone is free to take a job anywhere.

Some will no doubt condemn me, an immigrant, for base ingratitude. America let my family in. I should reciprocate by supporting the long-standing choices of the American people.

I beg to differ. If America practiced the equality of opportunity it preaches, my family wouldn't have needed government permission to immigrate. We could have moved from India to America with the same freedom that Californians move to Nevada. Now that I'm here legally, I'm going to tell you the truth - not pander to nativist prejudices that could easily have trapped me in the Third World - and continue to trap billions today.

I love living in this country. It's not just the standard of living. On an individual level, most Americans are famously nice people. Collectively, though, their behavior is atrocious - and Americans with a "social conscience" are often even worse. We don't need a bigger, better War on Poverty to become a just society. We just need to stop requiring discrimination against all the people without the good fortune to be born here.

Needless to say, Sendhil Mullainathan bears no responsibility for what I wish he would say. But I really wish he would join me in saying it. In case I've changed his mind, Sunday is Open Borders Day...

(0 COMMENTS)

Published on March 12, 2014 21:21

Optometry Challenge, by Bryan Caplan

Give me one good reason why basic eye exams can't already be done by a robot.

Written while waiting for a human with an M.D. to repeatedly ask me "Better like this... or like that?"

(25 COMMENTS)

Written while waiting for a human with an M.D. to repeatedly ask me "Better like this... or like that?"

(25 COMMENTS)

Published on March 12, 2014 07:31

March 11, 2014

Value of Self-Rated Health Bleg, by Bryan Caplan

Social scientists and medical researchers often ask people to rate their own health. The General Social Survey, for example, asks respondents to place themselves on a four-step scale:

I'm tempted to just ballpark it at 10% of annual full-time income per step on a four-point scale, but if anyone's proposed anything more sophisticated, I want to know about it.

Thanks in advance.

(4 COMMENTS)

Would you say your own health, in general, isQuestion: Do you know of any researchers who try to place a dollar value on self-rated health? I'm well aware of research on the dollar value of (a) a year of life, and (b) quality-adjusted life years. What I'm looking for is research that specifically puts a dollar value on a step of self-rated health.

excellent, good, fair, or poor?

I'm tempted to just ballpark it at 10% of annual full-time income per step on a four-point scale, but if anyone's proposed anything more sophisticated, I want to know about it.

Thanks in advance.

(4 COMMENTS)

Published on March 11, 2014 12:23

March 10, 2014

What Does Public Schooling Teach Us About Predatory Pricing?, by Bryan Caplan

Public schools provide education free of charge. The result, unsurprisingly, is overwhelming market dominance. Almost 90% of school-age kids attend public school. Most people think this is a great thing. Maybe they're right, maybe they're wrong. Either way, though, public schooling can teach us quite a bit about predatory pricing.

Predatory pricing is one of the simplest business practices to explain: Sell at a loss until you bankrupt your competitors. When you think about it, public schools apply this predatory strategy to an extreme degree. They don't just sell education at a loss. They "sell" education for free!

What can we learn from this epiphany? First and foremost, predation is a lot less effective than you'd think. After practicing predation to the utmost degree, public schools have only captured 90% of the market.

This is particularly striking when you realize that public schools - unlike normal businesses - can afford to practice predation indefinitely. When a normal business practices predation, competitors naturally wonder, "How long can the predator keep this up?" For private schools, in contrast, there is no light at the end of the tunnel. They keep serving 10% of the market even though they know in their bones that public schools' predatory pricing will continue without interruption.

A further lesson: In popular nightmares, predation works because its effects are lasting. Sell at a loss, kill each and every one of your competitors, and no rival will dare to challenge you for many a moon. Once you realize that public schools currently practice extreme predatory pricing, though, it's hard to take popular nightmares seriously.

Try this thought experiment. Public schools suddenly lose all their tax funding. (This could result from a voucher system, or just hard-core austerity). Now that schools have to cover their expenses with tuition, how long will public schools retain their 90% market share? If predation really had lasting effects, you'd expect competitors to remain scarce and scared for years, safeguarding public schools' incumbent advantage. In practice, though, I suspect that almost everyone - regardless of ideology - would expect public schools to lose at least half of their market share over the following decade. Driving the competition out of business with insanely low prices is not akin to salting the earth so nothing ever grows there again. Not even close.

Bottom line: The example of public schools should deter any normal business from pursing a predatory strategy. If permanently giving your product away for free only yields a 90% market share, what's the best that could happen if a normal business temporarily sold for 10% below cost? Customers should hope firms will be cocky enough to try predation. The long-run monopoly prices are sheer speculation - and the short-run discounts are undeniable. Unless, of course, your tax dollars are funding the discounts.

(2 COMMENTS)

Predatory pricing is one of the simplest business practices to explain: Sell at a loss until you bankrupt your competitors. When you think about it, public schools apply this predatory strategy to an extreme degree. They don't just sell education at a loss. They "sell" education for free!

What can we learn from this epiphany? First and foremost, predation is a lot less effective than you'd think. After practicing predation to the utmost degree, public schools have only captured 90% of the market.

This is particularly striking when you realize that public schools - unlike normal businesses - can afford to practice predation indefinitely. When a normal business practices predation, competitors naturally wonder, "How long can the predator keep this up?" For private schools, in contrast, there is no light at the end of the tunnel. They keep serving 10% of the market even though they know in their bones that public schools' predatory pricing will continue without interruption.

A further lesson: In popular nightmares, predation works because its effects are lasting. Sell at a loss, kill each and every one of your competitors, and no rival will dare to challenge you for many a moon. Once you realize that public schools currently practice extreme predatory pricing, though, it's hard to take popular nightmares seriously.

Try this thought experiment. Public schools suddenly lose all their tax funding. (This could result from a voucher system, or just hard-core austerity). Now that schools have to cover their expenses with tuition, how long will public schools retain their 90% market share? If predation really had lasting effects, you'd expect competitors to remain scarce and scared for years, safeguarding public schools' incumbent advantage. In practice, though, I suspect that almost everyone - regardless of ideology - would expect public schools to lose at least half of their market share over the following decade. Driving the competition out of business with insanely low prices is not akin to salting the earth so nothing ever grows there again. Not even close.

Bottom line: The example of public schools should deter any normal business from pursing a predatory strategy. If permanently giving your product away for free only yields a 90% market share, what's the best that could happen if a normal business temporarily sold for 10% below cost? Customers should hope firms will be cocky enough to try predation. The long-run monopoly prices are sheer speculation - and the short-run discounts are undeniable. Unless, of course, your tax dollars are funding the discounts.

(2 COMMENTS)

Published on March 10, 2014 22:00

March 9, 2014

Blame the Republicans, by Bryan Caplan

When I blame people for their problems, Democrats and liberals are prone to object at a fundamental level. One fundamental objection rests on determinism: Since everyone is determined to act precisely as he does, it is always false to say, "There were reasonable steps he could have taken to avoid his problem." Another fundamental objection rests on utilitarianism: We should always do whatever maximizes social utility, even if that means taxing the blameless to subsidize the blameworthy.

Strangely, though, every Democrat and liberal I know routinely blames one category of people for their vicious choices: Republicans. Watch their Facebook feeds. You'll see story after story about how Republicans - leaders and followers - shirk their basic moral duties. Republicans ignore their duty to help the less fortunate. Republicans ignore scientific evidence on global warming. Republicans lie to foment war. The point of these claims is not merely that Republican policies have bad consequences, but that Republicans are blameworthy people.

The underlying logic is rarely stated, but it snaps neatly into my framework of blame. Why are Republicans blameworthy? Because there are reasonable steps they could have taken to avoid being what they are. Instead of ignoring their duties to help the less fortunate, Republicans could show basic humanity. Instead of ignoring scientific evidence on global warming, Republicans could calmly defer to the climatological consensus. Instead of lying to foment war, Republicans could tell the truth.

Are these "reasonable" alternatives? Sure. This is clearly true for the Republican rank-and file. Since one vote has near-zero chance of noticeably changing political outcomes, political virtue is effectively free. Asking the typical Republicans to reverse course on global warming isn't like asking him to unilaterally give up his car. It's like asking him for a one-penny donation. Totally reasonable.

The same goes for Republican leaders. Yes, a successful Republican politician who broke ranks with his party would probably lose his job. But he could easily find alternative employment that didn't require him to spurn the poor, scoff at climate science, and make up stories about WMDs. Stop heinous activity, keep your upper-middle class lifestyle. Quite reasonable.

I'm tempted to dispute (some of) liberals' underlying factual claims here. But I won't. Instead, I'll just point out that blaming Republicans is incompatible with any fundamental rejection of the notion of blame. Blaming Republicans is incompatible with the determinist rejection of blame: If Republicans, like all humans "just can't help what they do," how can you blame them for scoffing at the IPCC? Blaming Republicans is incompatible with the utilitarian rejection of blame: If we should always do whatever maximizes social utility, blaming Republicans is just an irrelevant excuse for public policies that fail to take Republicans' feelings into account. Blaming Republicans is an existence theorem; if blaming Republicans is justified, blaming people is sometimes justified.

Personally, I strongly favor blaming Republicans. I think 80% of the blame heaped on Republicans is justified. What mystifies me, however, is the view that Republicans are somehow uniquely blameworthy. If you can blame Republicans for lying about WMDs, why can't you blame alcoholics for lying to their families about their drinking? If you can blame Republican leaders for supporting bad policies because they don't feel like searching for another job, why can't you blame able-bodied people on disability because they don't feel like searching for another job?

Democrats and liberals who expand their willingness to blame do face a risk: You will occasionally sound like a Republican! But why is that such a big deal? Maybe you'll lose a few intolerant hard-left friends, but they're replaceable. By taking a reasonable step - broadening your blame - you can avoid the vices of moral inconsistency and moral nepotism. To do anything less would be... blameworthy.

(1 COMMENTS)

Strangely, though, every Democrat and liberal I know routinely blames one category of people for their vicious choices: Republicans. Watch their Facebook feeds. You'll see story after story about how Republicans - leaders and followers - shirk their basic moral duties. Republicans ignore their duty to help the less fortunate. Republicans ignore scientific evidence on global warming. Republicans lie to foment war. The point of these claims is not merely that Republican policies have bad consequences, but that Republicans are blameworthy people.

The underlying logic is rarely stated, but it snaps neatly into my framework of blame. Why are Republicans blameworthy? Because there are reasonable steps they could have taken to avoid being what they are. Instead of ignoring their duties to help the less fortunate, Republicans could show basic humanity. Instead of ignoring scientific evidence on global warming, Republicans could calmly defer to the climatological consensus. Instead of lying to foment war, Republicans could tell the truth.

Are these "reasonable" alternatives? Sure. This is clearly true for the Republican rank-and file. Since one vote has near-zero chance of noticeably changing political outcomes, political virtue is effectively free. Asking the typical Republicans to reverse course on global warming isn't like asking him to unilaterally give up his car. It's like asking him for a one-penny donation. Totally reasonable.

The same goes for Republican leaders. Yes, a successful Republican politician who broke ranks with his party would probably lose his job. But he could easily find alternative employment that didn't require him to spurn the poor, scoff at climate science, and make up stories about WMDs. Stop heinous activity, keep your upper-middle class lifestyle. Quite reasonable.

I'm tempted to dispute (some of) liberals' underlying factual claims here. But I won't. Instead, I'll just point out that blaming Republicans is incompatible with any fundamental rejection of the notion of blame. Blaming Republicans is incompatible with the determinist rejection of blame: If Republicans, like all humans "just can't help what they do," how can you blame them for scoffing at the IPCC? Blaming Republicans is incompatible with the utilitarian rejection of blame: If we should always do whatever maximizes social utility, blaming Republicans is just an irrelevant excuse for public policies that fail to take Republicans' feelings into account. Blaming Republicans is an existence theorem; if blaming Republicans is justified, blaming people is sometimes justified.

Personally, I strongly favor blaming Republicans. I think 80% of the blame heaped on Republicans is justified. What mystifies me, however, is the view that Republicans are somehow uniquely blameworthy. If you can blame Republicans for lying about WMDs, why can't you blame alcoholics for lying to their families about their drinking? If you can blame Republican leaders for supporting bad policies because they don't feel like searching for another job, why can't you blame able-bodied people on disability because they don't feel like searching for another job?

Democrats and liberals who expand their willingness to blame do face a risk: You will occasionally sound like a Republican! But why is that such a big deal? Maybe you'll lose a few intolerant hard-left friends, but they're replaceable. By taking a reasonable step - broadening your blame - you can avoid the vices of moral inconsistency and moral nepotism. To do anything less would be... blameworthy.

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on March 09, 2014 21:08

March 6, 2014

40 Years on the Status Treadmill, by Bryan Caplan

The General Social Survey has spent four decades asking Americans about their self-perceived status:

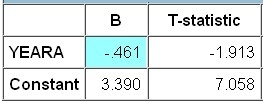

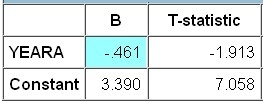

If you correct for rising income and education, though, status has noticeably fallen. Translation: People today need higher levels of achievement to feel superior to other people. See what happens as soon as you adjust for log family income, years of education, and attained degrees:

Magnitudes? The last equation implies that from 1972-2012, achievement-corrected status fell by .14. That's larger than the status gain people get when their income doubles.

Is this all obvious? To me, yes. But lately several economists I know have challenged me when I claimed that status is basically a zero-sum game. For America during my lifetime, they seem to be wrong - and I'm here to collect a little of their status. :-)

(4 COMMENTS)

If you were asked to use one of four names for your socialDuring this period, Americans experienced substantial absolute gains in income and education. Yet average status actually has a slight downward trend. Here's what you get if you regress status on year. (yeara=year/1000)

class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class (=1), the

working class (=2), the middle class (=3), or the upper class (=4)?

If you correct for rising income and education, though, status has noticeably fallen. Translation: People today need higher levels of achievement to feel superior to other people. See what happens as soon as you adjust for log family income, years of education, and attained degrees:

Magnitudes? The last equation implies that from 1972-2012, achievement-corrected status fell by .14. That's larger than the status gain people get when their income doubles.

Is this all obvious? To me, yes. But lately several economists I know have challenged me when I claimed that status is basically a zero-sum game. For America during my lifetime, they seem to be wrong - and I'm here to collect a little of their status. :-)

(4 COMMENTS)

Published on March 06, 2014 21:03

March 5, 2014

Poverty: The Stages of Blame Applied, by Bryan Caplan

What do my stages of blame imply about real-world poverty policy?

1. As I've argued in detail here,

poor healthy adults in the First World are largely undeserving. Indeed, few are even objectively poor; just look at the many luxuries the American poor typically enjoy.

2. People who used to be

healthy adults in the First World are also largely undeserving. As long as they were healthy enough to work for a

couples of decades, the vast majority could have easily saved enough

(or purchased enough insurance, annuities, etc.) to protect themselves from unemployment, accidents, sickness, old age, and other perennial troubles.

3. Genuinely poor

children in the First World are deserving. But the people who bear

primary moral responsible for their plight are their parents, not strangers.

"Don't have children until you are ready to provide for them" is a simple,

effective way to greatly reduce the risk you and your children will live in

poverty.

4. In the First World, people who develop severe health problems early in life are often deserving. I say "early in life" for reasons explained in #2, above, and "often" because many people with severe health problems are self-supporting or can rely on their families for help.

5.

Although #3 & #4 are not morally responsible

for their plight, this hardly implies that total strangers are morally responsible. So the strong duties to "cease and remedy" don't apply. To make even a plausible case for forcing strangers to help them, you have to show that the benefits heavily outweigh the costs. This is harder than it sounds; see e.g. small estimates of the effect of health care on health outcomes.

6. Unlike First Worlders, poor

Third Worlders - adults as well as children - are usually deserving. Why? Because most will remain absolutely poor even if they are models of bourgeois virtue.

7.

Third World poverty exists for multiple morally blameworthy reasons.

The fact remains, however, that most of the Third World's poor could escape poverty if First World governments respected their basic human right to sell their labor to willing First World employers.

8. First Worlders who support immigration restrictions are therefore morally responsible for Third World poverty, and are obliged to

cease their support for immigration restrictions and remedy the harm

they have done.

9. This does not mean, however, the First Worlders are collectively morally responsible for Third World poverty. While most First Worlders support the status quo or worse, a sizable minority are politically inactive or even oppose immigration restrictions. Forcing the latter group to help the Third World poor (e.g. via foreign aid) is unjustified unless the benefits heavily outweigh the costs, which they probably don't.

In sum: The stages of blame, combined with basic facts about poverty, are deeply consistent with a radical libertarian critique of the status quo. Modern social democracies force their citizens to help their countrymen even though the latter are largely undeserving - and often not really poor. The most that could be justified is a rump welfare state that helps poor children and people who develop severe health problems early in life. At the same time, social democracies deliberately and massively increase global poverty by banning employment contracts between citizens and foreigners.

Like it or not, much-maligned U.S. Gilded Age poverty policies - minimal government assistance combined with near-open borders - were close to ideal. And the broadly-defined poverty policies of much-beloved post-war social democracies are morally perverse - enforcing absurdly inflated moral duties toward poor citizens while slandering poor foreigners as criminals for using the most realistic strategy they have to avoid poverty: getting a job in the First World.

(20 COMMENTS)

1. As I've argued in detail here,

poor healthy adults in the First World are largely undeserving. Indeed, few are even objectively poor; just look at the many luxuries the American poor typically enjoy.

2. People who used to be

healthy adults in the First World are also largely undeserving. As long as they were healthy enough to work for a

couples of decades, the vast majority could have easily saved enough

(or purchased enough insurance, annuities, etc.) to protect themselves from unemployment, accidents, sickness, old age, and other perennial troubles.

3. Genuinely poor

children in the First World are deserving. But the people who bear

primary moral responsible for their plight are their parents, not strangers.

"Don't have children until you are ready to provide for them" is a simple,

effective way to greatly reduce the risk you and your children will live in

poverty.

4. In the First World, people who develop severe health problems early in life are often deserving. I say "early in life" for reasons explained in #2, above, and "often" because many people with severe health problems are self-supporting or can rely on their families for help.

5.

Although #3 & #4 are not morally responsible

for their plight, this hardly implies that total strangers are morally responsible. So the strong duties to "cease and remedy" don't apply. To make even a plausible case for forcing strangers to help them, you have to show that the benefits heavily outweigh the costs. This is harder than it sounds; see e.g. small estimates of the effect of health care on health outcomes.

6. Unlike First Worlders, poor

Third Worlders - adults as well as children - are usually deserving. Why? Because most will remain absolutely poor even if they are models of bourgeois virtue.

7.

Third World poverty exists for multiple morally blameworthy reasons.

The fact remains, however, that most of the Third World's poor could escape poverty if First World governments respected their basic human right to sell their labor to willing First World employers.

8. First Worlders who support immigration restrictions are therefore morally responsible for Third World poverty, and are obliged to

cease their support for immigration restrictions and remedy the harm

they have done.

9. This does not mean, however, the First Worlders are collectively morally responsible for Third World poverty. While most First Worlders support the status quo or worse, a sizable minority are politically inactive or even oppose immigration restrictions. Forcing the latter group to help the Third World poor (e.g. via foreign aid) is unjustified unless the benefits heavily outweigh the costs, which they probably don't.

In sum: The stages of blame, combined with basic facts about poverty, are deeply consistent with a radical libertarian critique of the status quo. Modern social democracies force their citizens to help their countrymen even though the latter are largely undeserving - and often not really poor. The most that could be justified is a rump welfare state that helps poor children and people who develop severe health problems early in life. At the same time, social democracies deliberately and massively increase global poverty by banning employment contracts between citizens and foreigners.

Like it or not, much-maligned U.S. Gilded Age poverty policies - minimal government assistance combined with near-open borders - were close to ideal. And the broadly-defined poverty policies of much-beloved post-war social democracies are morally perverse - enforcing absurdly inflated moral duties toward poor citizens while slandering poor foreigners as criminals for using the most realistic strategy they have to avoid poverty: getting a job in the First World.

(20 COMMENTS)

Published on March 05, 2014 21:06

March 4, 2014

Poverty: The Stages of Blame, by Bryan Caplan

I've repeatedly argued that there's a connection between (a) how deserving the poor are, and (b) how the poor ought to be treated. Unfortunately, as soon as I make this deliberately vague claim, many readers rush to ascribe specific, silly views to me. To preempt future misinterpretations, I now sketch my view in greater detail.

1. Claims about desert and poverty are meaningful. Asking, "Does he deserve to be poor?" can be rude, but that doesn't mean the answer is "No."

2. A person deserves his problem if there are reasonable steps the he could have taken to avoid the problem. Poverty is a problem, so a person deserves his poverty if there are reasonable steps he could have taken to avoid his poverty.

3. Common sense can usually resolve whether reasonable steps to avoid poverty were available to a particular person. A good rule of thumb: If you wouldn't accept an excuse from a friend, you shouldn't

accept it from anyone.

4. The fact that a person deserves his poverty does not imply that it is morally wrong to help him.

5. However, the fact that a person deserves his poverty is (a) a strong moral reason to give him low priority when weighing how to allocate help, and (b) a strong moral reason not to force a stranger to help him.

6. The fact that a person does not deserve his poverty does not imply that it is morally wrong not to help him.

7. However, the fact that a person does not deserve his poverty is (a) a strong moral reason to give him high priority when weighing how to allocate help, (b) an extra moral reason for individuals morally responsible for his poverty to cease and remedy their wrongful behavior, (c) a moral reason to force these morally responsible individuals to cease and remedy their wrongful behavior, and (d) a plausible though not totally convincing moral reason to force strangers to help the deserving person if the benefits heavily outweigh the costs.

Coming soon: What these claims imply about government policy and personal behavior.

HT: Bill Dickens for spurring me to clarify my position.

(5 COMMENTS)

1. Claims about desert and poverty are meaningful. Asking, "Does he deserve to be poor?" can be rude, but that doesn't mean the answer is "No."

2. A person deserves his problem if there are reasonable steps the he could have taken to avoid the problem. Poverty is a problem, so a person deserves his poverty if there are reasonable steps he could have taken to avoid his poverty.

3. Common sense can usually resolve whether reasonable steps to avoid poverty were available to a particular person. A good rule of thumb: If you wouldn't accept an excuse from a friend, you shouldn't

accept it from anyone.

4. The fact that a person deserves his poverty does not imply that it is morally wrong to help him.

5. However, the fact that a person deserves his poverty is (a) a strong moral reason to give him low priority when weighing how to allocate help, and (b) a strong moral reason not to force a stranger to help him.

6. The fact that a person does not deserve his poverty does not imply that it is morally wrong not to help him.

7. However, the fact that a person does not deserve his poverty is (a) a strong moral reason to give him high priority when weighing how to allocate help, (b) an extra moral reason for individuals morally responsible for his poverty to cease and remedy their wrongful behavior, (c) a moral reason to force these morally responsible individuals to cease and remedy their wrongful behavior, and (d) a plausible though not totally convincing moral reason to force strangers to help the deserving person if the benefits heavily outweigh the costs.

Coming soon: What these claims imply about government policy and personal behavior.

HT: Bill Dickens for spurring me to clarify my position.

(5 COMMENTS)

Published on March 04, 2014 20:37

The Principal Doctrines of Epicurus: Friendliness, Social Intelligence, and the Bubble, by Bryan Caplan

The Principal Doctrines of Epicurus

is a 3rd-century outline of Epicurean philosophy. This bullet point is so consistent with my posts on friendliness, social intelligence, and the Bubble that I feel compelled share it.

(2 COMMENTS)

He who desires to live

in tranquility with nothing to fear from other men ought to make

friends. Those of whom he cannot make

friends, he should at least avoid rendering enemies; and if that is not in his power,

he should, as much as possible, avoid all dealings with them, and keep them aloof,

insofar as it is in his interest to do so.

(2 COMMENTS)

Published on March 04, 2014 08:26

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.