Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 149

April 20, 2014

Social Desirability Bias: How Psych Can Salvage Econo-Cynicism, by Bryan Caplan

Economists have a long-standing defense mechanism against this mountain of evidence: Behaviorism. Milton Friedman told us you can't believe what people say. Many of us still believe him. But this position isn't just self-refuting; it's absurdly dogmatic. Virtually every person alive professes noble aims, so economists invoke the methodological principle that "Words count for nothing"? If that's our best response to ubiquitous empirical evidence, the world is right to dismiss us as a cult.

Fortunately, there is a far more compelling response... with one big catch: Economists have to outsource their intellectual defense to psychologists. Like economists, psychologists are deeply skeptical about mere words. They too hold a cynical view of human nature. To defend it, though, they don't rely on half-baked philosophy of science. Instead, they carefully measure and compare the divergence between what people say and what they do.

The fruit of psychologists' toil, as I've mentioned before (here, here, and here for starters), is the sprawling literature on Social Desirability Bias. To re-summarize:

Why is the psychologists' approach so superior to the economists'? Simple. Economists reject all-pervasive testimony on lame methodological grounds. Psychologists, in contrast, aggressively cross-examine this all-pervasive testimony, and empirically expose its all-pervasive perjury. Despite what they say, people really are selfish, businesses really are greedy, students really are lazy, and workers really are materialistic. Econo-cynicism has a firm basis in psychological fact.Social desirability bias is the tendency of respondents to

answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others. It

can take the form of over-reporting "good behavior" or under-reporting

"bad," or undesirable behavior. The tendency poses a serious problem

with conducting research with self-reports, especially questionnaires.

This bias interferes with the interpretation of average tendencies as

well as individual differences.Topics where socially desirable responding (SDR) is of special

concern are self-reports of abilities, personality, sexual behavior, and

drug use...Other topics that are sensitive to social desirability bias:

Personal income and earnings, often inflated when low and deflated when high.Feelings of low self-worth and/or powerlessness, often denied.Excretory functions, often approached uncomfortably, if discussed at all.Compliance with medicinal dosing schedules, often inflated.Religion, often either avoided or uncomfortably approached.Patriotism, either inflated or, if denied, done so with a fear of other party's judgement.Bigotry and intolerance, often denied, even if it exists within the responder.Intellectual achievements, often inflated.Physical appearance, either inflated or deflatedActs of real or imagined physical violence, often denied.Indicators of charity or "benevolence," often inflated.Illegal acts, often denied.

Of course, a "firm basis in fact" is hardly the same as "unvarnished truth." Some deviations from narrow self-interest handily survive cross-examination. Voting really is largely unselfish, workers really do obsess about nominal pay, and managers sincerely hate firing anyone. The point, though, is that the economic way of thinking is on much stronger empirical ground than economists themselves have managed to demonstrate. Though we've often belittled psychology, it's ably served us for decades. Perhaps if economists give psychologists some much-deserved credit for Social Desirability Bias, they'll be more eager to vouch for the value of what we do.

(2 COMMENTS)

April 18, 2014

Tuesday Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

The Center for Immigration Studies' masthead reads, "Low-Immigration, Pro-Immigrant." I've dissected this before, but here's a further thought. Imagine telling your spouse, "I love your mother, but I want her to visit as rarely as possible." Can you even say it aloud without laughing? What you really mean is, "Your mother's insufferable, but as long as she's here, I'll try to be nice to her."

That's what the CIS slogan amounts to: Immigrants are insufferable, but as long as they're here, we'll try to be nice to them.

(1 COMMENTS)

April 17, 2014

Tourists Welcome, by Bryan Caplan

Yes, visas and other regulations on tourism are well-established. Their chief rationale, however, is to prevent tourists from mutating into immigrants. From the State Department:

The required presumption under U.S. law is that every visitor visa applicant is an intending immigrant until they demonstrate otherwise. Therefore, applicants for visitor visas must overcome this presumption by demonstrating:Requiring "evidence of funds to cover expenses" seems designed to prevent tourists from going on welfare or begging in the streets. All the other requirements, though, ultimately reflect a single goal: preventing foreigners from getting U.S. jobs. As long as they run around spending money on hotels, restaurants, and Disneyland, great! But we don't want them to take jobs and start producing stuff for us.

• That the purpose of their trip is to enter the United States temporarily for business or pleasure;

• That they plan to remain for a specific, limited period;

• Evidence of funds to cover expenses in the United States;

• That they have a residence outside the United States as well as other binding ties that will ensure their departure from the U.S. at the end of the visit.

The populist view, as you're well-aware, is that immigrant workers are "taking jobs" that rightfully belong to natives. But you could just as easily accuse tourists of "taking stuff" - hotel rooms, restaurant meals, Disneyland tickets - that rightfully belong to natives. Selling stuff to foreigners is mutually beneficial? Then why isn't producing stuff for natives mutually beneficial, too?

To explain this odd double standard, I once again accuse misanthropy. We readily welcome foreign money. Money, after all, can be exchanged for goods and services. But foreign people? Of what possible use are they? Just think of all the bad things a person might conceivably do or be. Shudder.

An economist might claim that the very fact that an immigrant lands a paying job is a strong sign that they're useful to somebody. He could even insist that immigration drastically raises foreigners' wages by drastically raising their productivity. But that's just market fundamentalism. Move along, nothing to see here...

(2 COMMENTS)

April 16, 2014

I've Won My TARP Bet, by Bryan Caplan

In response, I publicly offered the following bet:SEC. 134. RECOUPMENT.

Upon the expiration of the 5-year period beginning upon the date of the enactment of this Act, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, in consultation with the Director of the Congressional Budget Office, shall submit a report to the Congress on the net amount within the Troubled Asset Relief Program under this Act.

In any case where there is a shortfall, the President shall submit a

legislative proposal that recoups from the financial industry an amount

equal to the shortfall in order to ensure that the Troubled Asset Relief

Program does not add to the deficit or national debt. (emphasis mine)

If the Director of the OMB's 2013 report says that a shortfall exists, IThe OMB's 2013 report is now in. You can download all 510 pages here, then turn to page 39:

win. Otherwise, I lose. The stakes: I will make up to five $100 bets

at even odds.

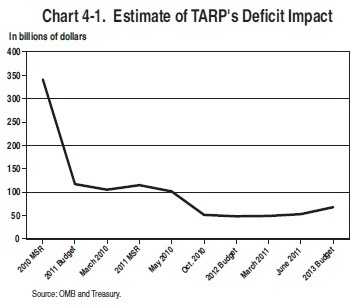

As of December 31, 2011, total repayments and income on TARP investments were approximately $318 billion, which is 77 percent of the $414 billion in total disbursements to date. The projected total lifetime deficit impact of TARP programmatic costs, reflecting recent activity and revised subsidy estimates based on market data as of November 30, 2011, is now estimated at $67.8 billion.Graphically:

This is actually more pessimistic than the OMB's previous update, which also had me on track to win:

Compared to the 2012 MSR estimate of $46.8 billion, the estimated deficit impact of TARP increased by $21 billion. This increase was largely attributable to the lower valuation of the AIG and GM common stock held by Treasury.If you don't wish to download a 510-page pdf, try the CBO's 8-page summary of the OMB report, combined with the CBO's slightly different (but still negative) estimates of TARP's budgetary costs.

TARP was passed on October 3, 2008. Since the CBO's report is dated May 23, 2013, you could argue that I am declaring victory a few months prematurely. However, the CBO report also explains that this is the 2013 TARP report:

Originally, the law required OMB and CBO to submit semiannual reports. That provision was changed by Public Law 112-204 to an annual reporting requirement. OMB's most recent report on the TARP was submitted on April 10, 2013.None of TARP's cheerleaders accepted my bet, even though their announced beliefs seemingly implied that betting me would be taking candy from a baby. As far as I can tell, the only people who clearly accepted my bet were EconLog readers Michael K and Rick Stewart. Steve Roth somewhat ambiguously accepted, so I leave payment to his conscience.

HT: Philip Wallach at Brookings for reminding me about the bet.

(2 COMMENTS)

April 15, 2014

Try Harder or Do Something Easier?, by Bryan Caplan

You could say, "Open the restaurant and work like mad, because the odds are against you." Slogan: Try Harder.

Or you could say, "Don't open the restaurant, because the odds are against you." Slogan: Do Something Easier.

Neither recommendation is crazy. But as the probability of failure rises, the case for Do Something Easier gets stronger and stronger. Why tell your friend to work his fingers to the bone when he's probably going to fail anyway?

This is especially true on the plausible assumption that people are more likely to heed advice about one-time discrete decisions than day-to-day continuous decisions. Saying "Marry her" is more likely to sway behavior than "Be good to your wife every day" - and saying "Do Something Easier" is more likely to sway behavior than "Try Harder."

Why then are advisers so reluctant to say "Do Something Easier"? Because Try Harder sounds better - and most advisers would rather sound good than genuinely help their advisees.

This analysis clearly applies to starting a business or choosing an occupation. But it works equally well for educational decisions. Suppose a kid at the 30th percentile of the high school distribution asks you if he should go to college. You know that kids at the 30th percentile have a dismal dropout rate. Should you respond with Try Harder or Do Something Easier?

In our society, "Try Harder" is the socially acceptable - nay, socially mandatory! - slogan. Don't tell kids to give up on their dreams; tell them to work for their dreams. On reflection, though, this just exposes advisers' vanity: They'd rather sound helpful than be helpful. Do you really imagine that chanting "Try Harder" will induce weak students to devote themselves to their studies, day in, day out? No? Then urging weak students to "Try Harder" barely differs from "Make an expensive investment that will fail at its normal high rate."

To be fair, most weak students will ignore you even if you urge them to Do Something Easier. But some will probably listen to you - and refrain from making a very bad bet.

What about the tiny minority of weak students who would have blossomed in college? Obsession with this group is the height of pious folly. Suppose you convince a lot of people to stop buying lottery tickets. Should you lose sleep over the likelihood that - but for your advice - one of your advisees would have won the jackpot? Of course not. "Advice that works on average" is also known as "good advice."

Say it with me: Risk of failure is a reason not to try. Not a decisive reason, but a reason nonetheless - and the higher the risk of failure, the stronger the reason. True, if you have no alternatives, you may as well try your best and hope for the best. But would-be restaurant owners and would-be students always have alternatives. And as long as you have alternatives, willingness to Do Something Easier in the face of crummy odds is not cowardice. It is good economics - and common sense.

(15 COMMENTS)

Smoking, Social Desirability Bias, and Dark Matter, by Bryan Caplan

For most goods, the two show broadly the same pattern: with smallWhy is tobacco dark matter? Social Desirability Bias!

errors, what people profess to buy grosses up to what is really being

sold in the country. But tobacco is a big exception. Less then half of

the recorded cigarette purchases shows up in the Living Cost and Food

Survey. In the US equivalent, the ratio is not even 40%.

The mismatch between what smokers say in surveys and what they do in

practice is a classic example of the difference between "stated

preferences" and "revealed preferences".

Social engineers love stated preferences. Opponents of big

supermarkets, too, always have a survey at hand, indicating that the

vast majority of residents in their areas would never set foot in a

discounter. But once it is there, it flourishes.

There is nothing schizophrenic about this behaviour. When asked

whether you would shop in a big supermarket in your area, of course you

respond something like "No! Small, local shops are much more charming and personal"

- because that is the socially acceptable thing to say. When you smoke,

saying that you want to quit makes you at least a repentant sinner.

Now ask yourself: Is voting more like a national product account - or a consumer expenditure survey?

(1 COMMENTS)April 14, 2014

Civil Disobedience: King versus Huemer, by Bryan Caplan

In no sense do IThe obvious question: If the law is unjust, doesn't consenting to punishment simply compound the injustice? The subtler challenge: "Evading" or "defying" just laws could easily lead to "anarchy" in a pejorative sense. But why on earth is King so pessimistic about the social effects of "evasion" or "defiance" of unjust laws? Indeed, if the laws are really so awful, you'd expect every violation to make the world a little bit better.

advocate

evading or defying the law, as would the rabid segregationist. That would lead to anarchy.

One who

breaks an unjust law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the

penalty. I

submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust, and who

willingly

accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the conscience of the community

over its

injustice, is in reality expressing the highest respect for law.

Perhaps King's underlying story is a variant of the Noble Lie. Something along the lines of:

1. People often mistakenly think that a law is unjust.

2. If people feel free to evade or defy laws they think are unjust, they will break many just laws, with awful consequences.

3. However, if people feel obliged to accept the legal punishments for breaking all laws regardless of their justice, they will reflect seriously on the justice of the law, drastically reducing their chance of mistakenly breaking an unjust law.

4. Therefore, it is good if people don't feel free to evade or defy laws they deem unjust.

Assuming I have successfully reverse engineered King's underlying position, it has two major flaws.

First, it neglects a simple alternative to promoting the Noble Lie that evading or defying unjust laws is wrong. Namely: Promoting the Noble Truth that people should painstakingly investigate the justice of a law before breaking it.

Second, this story neglects the very existence of moderately virtuous people who are willing to resist unjust laws if and only if the personal cost is low. If such people feel free to evade or defy unjust laws, they'll break them, making the world more just. However, if they don't feel free to evade or defy unjust laws, they'll obey them, preserving the injustice of the status quo.

Philosopher Michael Huemer's new essay on jury nullification presents a more compelling position on civil disobedience: Don't merely feel free to break unjust laws; strive to prevent their enforcement. He begins with one of his trademark hypotheticals.

Imagine that you are walking down a public street with flamboyantly-dressed friend, when you are accosted by a gang of gaybashing hoodlums. The leader of the gang asks you whether your friend is gay. You have three alternatives: you may answer yes, refuse to answer, or answer no. You are convinced that either of the first two choices will result in a beating for your friend. However, you also know that your friend is in fact gay. Therefore, how should you respond?Huemer's point obviously still applies if the hoodlums directly interrogate the gay man. Lying is usually wrong, but not when your audience plans to savagely beat you for telling the truth. Even a juror who explicitly promises to enforce the letter of the law can rightfully renege:

This is hardly an ethical dilemma. Clearly, you should answer no. No person with a reasonable and mature moral sense will have difficulty with this case. Granted, it is usually wrong to lie, but the importance of avoiding inaccurate statements pales in comparison to the importance of avoiding serious and unjust injury for your friend. The case illustrates a simple and uncontroversial ethical principle: it is prima facie wrong to cause another person to suffer serious undeserved harms. This is true even when the harm would be directly inflicted not by oneself but by a third party.

Three ethical principles governing the obligation of promises seem relevant here. To begin with, it is normally permissible to break a promise when necessary to prevent serious and undeserved harms to another person. For instance, suppose you have promised to pick a friend up from the airport, but on the way, you encounter an injured accident victim in need of medical assistance. It would be permissible, if not obligatory, to assist the accident victim, even though doing so will prevent you from picking up your friend. And this is true regardless of whether your friend will be understanding about your failure to pick him up.Returning to the gaybashing hypothetical:

Second, a promise prompted by a threat of unjust coercion is typically not ethically binding. If a gunman threatens to shoot you unless you promise to pay him $1,000, that promise will have no moral force. Thus, if you escape the gunman after making the promise, you have no moral obligation at all to deliver $1000 to him. The same goes for unjust threats against third parties: if a gunman threatens to shoot your neighbor unless you promise to pay $1,000 to the gunman, that promise, too, is invalid. If the neighbor escapes after you have made the promise, you have no obligation at all to hand over the money.

Third, even when a promise is initially valid, it is permissible to break the promise if doing so is necessary to forestall a threat of unjust harm from the person to whom the promise was made. The promisee in such a case has no valid complaint, since it is his own threatened unjust behavior that makes it necessary to break the promise. For example,

suppose I have voluntarily promised to lend you my rifle next weekend. Before the week-end arrives, you credibly inform me that you intend to use the rifle to murder several people. In this case, I should not still lend you the rifle. It is not merely that my prima facie

obligation to keep the promise is outweighed by the need to prevent several murders. Rather, your threat of unjust harm completely cancels any obligation I would have had to keep my promise to you.

Imagine that the gang leader not only asks whether your friend is gay but also asks you to swear that your answer on this point will be truthful. You reasonably believe that refusal to swear will result in a beating for your friend. This case is scarcely more difficult than the original case. Clearly, you should swear to tell the truth and then immediately lie to the gang. In doing so, you do not wrong the gaybashing gang or anyone else. The gang would have no valid complaint against you for your breaking of your promise, since it is their own unjust coercive threat that forced you both to make the promise and to break it.What about the specter of "anarchy" - the fear that people will cavalierly dismiss as "unjust" any law that frustrates their desires? Huemer finds this a poor argument against jury nullification.

Suppose you are on a jury in a trial in which the defendant is accused of violating an unjust law, and you are considering a nullification vote. Your motivation is not racist, and you know that it isn't. You know that your motivation is the injustice of the law. It is difficult to see how the fact that some racist juries have voted to acquit defendants who should have been punished negates the very strong reason that you have, in this case, to acquit the defendant. The fact that others have done A for bad reasons does not make it wrong for one to do A for good reasons.Huemer's critique readily extends to civil disobedience more generally. The fact that people often break just laws is a lame argument for obeying unjust laws. The proper remedy for abuse is greater investment in moral reasoning, not blind obedience to unjust laws or masochistic submission to unwarranted legal punishment. King was right to oppose blind obedience. But his advocacy of masochistic submission to unjust punishment is barely better.

Consider again the example of the gang of hoodlums. Suppose that you are just about to lie to the gang, when it occurs to you that many people have lied for bad reasons. In fact, surely there have been more cases of corrupt lying in human history than there have of morally justified lying. It would be absurd to suggest that this historical fact somehow negates the reason that you have for lying in this case, or that you are morally bound to always tell the truth merely because more lies have been harmful than have been beneficial.

(22 COMMENTS)

April 13, 2014

Divorce and Motivated Reasoning in the WaPo, by Bryan Caplan

Psychologist Tom Gilovich has suggested that someone who

wants to accept a hypothesis tends to ask, "Can I believe it?" In contrast, someone who wants to reject it

tends to ask, "Must I believe it?"

I immediately thought of Gilovich's insight while reading Scott Keyes' op-ed on divorce in the Washington Post.

"Can I believe it?":

No-fault divorce has been a success. A 2003 Stanford University study

detailed the benefits in states that had legalized such divorces:

Domestic violence dropped by a third in just 10 years, the number of

husbands convicted of murdering their wives fell by 10 percent, and the

number of women committing suicide declined between 11 and 19 percent. A

recent report

from Maria Shriver and the Center for American Progress found that only

28 percent of divorced women said they wished they'd stayed married.

"Must I believe it?":

While some studies show that children of divorced parents do experience

worse life outcomes -- including diminished math and social skills, a

higher chance of dropping out of school, poorer health, and a greater

likelihood of divorce themselves -- Stanford sociologist Michael

Rosenfeld points out that there is no way to test definitively whether

children of divorced parents were already more likely to experience such

outcomes.

And as Stephanie Coontz, a historian and the author of "Marriage, a History," explains, what's most critical is the high-conflict environment that kids grew up in before their parents separated.

How fortunate that there is a "way to test definitively" whether domestic violence and female suicide would have fallen if divorce laws hadn't been liberalized!

"Must I believe it?" continued:

Would making divorce less accessible encourage

partners to stay together, as conservatives hope? Probably not. Waiting

periods and mandatory classes "add a new frustration to already

frustrated lives," Rosenfeld notes. In other words, a cooling-off period

isn't cooling anybody off.

"Can I believe it?" continued:

More

problematic, these roadblocks "could easily exacerbate the situation

and harm kids," Coontz says, noting that divorcees are "more likely to

parent amicably if they haven't been locked into a long separation

process."

Keyes' double standard vexes me even though I think (a) government should play no role in marriage, and (b) twin and adoption evidence shows little or no effect of divorce on kids' adult outcomes. All of the following still remain highly plausible:

a. There are a lot of so-so marriages.

b. The cost of divorce affects the divorce rate for couples in so-so marriages.

c. Most kids of couples in so-so marriages strongly prefer for their families to stay together.

Oh, and if liberalized divorce has been so great, why did this happen? Don't tell me what you can believe. Don't tell me what you must believe. Just tell me what makes sense to you.

(3 COMMENTS)April 11, 2014

Kids and Happiness: The State of the Art, by Bryan Caplan

1. Parental age

[S]ome investigators have compared young and old parents with their respective childless peers. This research has demonstrated that middle-aged and old parents are either as happy or happier than their childless peers, whereas young parents are less happy than their childless peers.2. Child age.

[P]arents of younger children experience lower well-being than parents of older children. We propose that these differences are primarily explained by the relatively greater negative emotions, greater sleep disturbances, and lower marital satisfaction experienced by parents of young children (cf. Bird, 1997), as well as by the enhanced feelings of closeness, connectedness, and basic evolutionary need satisfaction experienced by parents of relatively older children3. Parental gender.

[P]arenthood is consistently linked to greater well-being among men but not among women in part because fathers experience relatively more positive emotion (e.g., Larson et al., 1994; Nelson et al., 2013) and mothers experience more negative emotion (e.g., Ross & Van Willingen, 1996; Zuzanek & Mannell, 1993).4. Parental marital status.

[The research] can be interpreted in at least three ways, which are not necessarily mutually exclusive: (a) Becoming a parent magnifies the happiness gained from marriage (e.g., Aassve et al., 2012), (b) not having a partner to share the experience of child rearing diminishes the well-being gains and heightens the stress from having children (e.g., Nelson et al., 2013, Study 1), or (c) unhappy parents are more likely to become single through divorce, separation, or failure to attract a long-term partner.5. Residence.

Both cross-sectional and transition-to-parenthood studies have shown that noncustodial parents report lower levels of well-being than custodial parents... This work suggests that the stress of not having one's own children at home and missing out on the pleasures of parenting may outweigh the stress of taking active care of one's children.My main disappointment with the state of the literature: There's still little evidence on the effect of parenting style on parental happiness.

Although a large literature explores the implications of parenting style and parenting behaviors for child outcomes (e.g., Darling & Steinberg, 1993), very few studies examine how parenting style--and an intensive versus relaxed style in particular--might relate to the parents' own well-being.Unfortunately, this excellent article will probably get little media attention because it lacks a sensational punchline. But if you really want to know what researchers know about kids and happiness, "The Pains and Pleasures of Parenting" is the piece to read.

(8 COMMENTS)

April 10, 2014

Crude Self-Interest: Why Kids Go to College, by Bryan Caplan

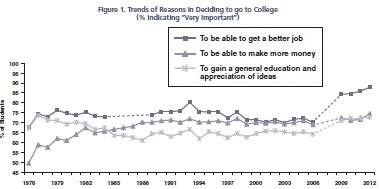

Incoming students persist in putting a premium on job-related reasons to go to college. Continuing to rise is the importance of going to college in order to get a better job, which rose two percentage points this year to an all-time high of 87.9%, up from 85.9% in 2011 and considerably higher than its low of 67.8% in 1976 (see Figure 1). In the minds of today's college students, getting a better job continues to be the most prevalent reason to go to college.The long-run picture:

Also at an all-time high as a reason to go to college is "to be able to make more money," moving from 71.7% in 2011 to 74.6% in 2012. This is now the fourth-ranked important reason to go to college, surpassing "to gain a general education and appreciation of ideas," which is now at 72.8%. A related finding is that is "being very well off financially" as a personal goal rose to an all-time high in 2012, with 81.0% of incoming students reporting this as a "very important" or "essential" personal goal, up from 79.6% in 2011.

Yes, you could object, "Over half the students also care deeply about getting a 'general education and appreciation of ideas.'" But remember Social Desirability Bias. Saying you're in college for the money sounds bad. Saying you're in college for the ideas sounds good. Yet the ugly answer has generally been more popular. If you make even a moderate adjustment for Social Desirability Bias, crude self-interest wins by a landslide.

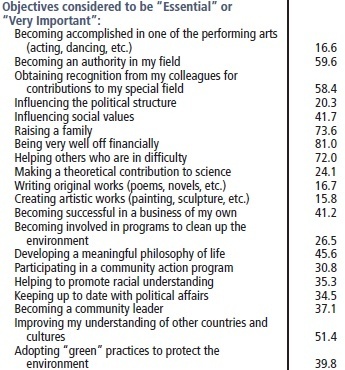

Not convinced? Switching from vague generalities to specifics is a helpful remedy for Social Desirability Bias. Look at the results from this broader list of students' college objectives:

"Being very well off financially" sounds less noble than anything else on the list, yet it remains the top response. Idealistic motives like "influencing the political structure," making original scientific or artistic contributions, or just "influencing social values" sound lovely, but most respondents don't even pretend they're priorities. The only flowery objective that commands widespread assent - "Helping others who are in difficulty" - is also conveniently empty.

Like most professors, I'm not fond of careerist students. I prefer to teach classes full of kids who love ideas for their own sake. Indeed, there are few things I treasure more. But let's not fool ourselves. Economists who assume that college attendance is driven by students' greed are largely correct.

(15 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers