Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 148

May 2, 2014

Demagoguery Explained, by Bryan Caplan

In Merriam-Webster, a demagogue is "a political leader who tries to get support by making false claims and

promises and using arguments based on emotion rather than reason."

In the Oxford Dictionary, he's "a political leader who seeks support by appealing to popular desires and prejudices rather than by using rational argument."

In the Wiktionary, he's a "political orator or leader who gains favor by pandering to or exciting the passions and prejudices of the audience rather than by using rational argument."

In your calmer moments, though, it's tempting to dismiss the concept. In practice, isn't a "demagogue" just a political opponent with a silver tongue? Isn't "demagoguery" simply rhetoric that hits political nerves you wish would stay eternally numb?

But before you ditch the whole concept, let me propose the following refinement: Demagoguery is the politics of Social Desirability Bias.

The heart of Social Desirability Bias: Some types of claims sound good or bad regardless of the facts. "Helping people" sounds good. "Acquiring luxuries" sounds bad. "Saving American jobs" sounds good. "Cheap nannies for upper-middle class families" sound bad. "Supporting our troops" sounds good. "Sympathizing with the enemy" sounds bad. "Raising the minimum wage" sounds good. "Measuring disemployment effects" sounds bad.

Any competent philosopher can construct cases where what sounds good is bad and what sounds bad is good. For instance: The minimum wage, good as it sounds, would be bad if it sharply increased unemployment of low-skilled workers. But when our competent philosopher runs for office, he has a clear incentive to keep his doubts to himself. If X sounds good, saying "Hooray for X" is a much easier way to win over an audience than "Sure X sounds good, but let's calm down and consider the possibility that X is in fact bad."

It's possible, I grant, that X's only sound good when those X's are good. If so, we can safely ignore Social Desirability Bias. To test this optimistic view, I propose the following thought experiment:

Imagine we do vastly more X. Could you then publicly declare, "We're doing too much X" without cringing?If government spent ten times as much on terminally ill children, would you feel comfortable announcing, "Government is wasting money on terminally ill children"? If government spent ten times as much on war heroes, would you feel comfortable shouting, "Government gives too much to war heroes"? Don't want to say such things ever ever ever? Then the policy views you and your fellow citizens cherish are probably infected by Social Desirability Bias.

The same goes for the Panglossian view that "X sounds bad" solely

because "X is bad." Imagine we increased our anti-terrorism efforts

ten-fold. Would that remove the stigma from saying, "Let's relax our

anti-terrorist efforts"? Not bloody likely.

What then is demagoguery? Embracing Social Desirability Bias to gain power. Making a career out of praising what sounds good and attacking what sounds bad.

What's the alternative? Conscientiously searching for and publicizing the many disconnects between what's pleasing to the ear and what's true.

You could object that no public enemy of Social Desirability Bias could succeed in politics. While I tend to agree, that realization should terrify you. Social Desirability Bias is a severe mental shortcoming, but to succeed in politics you have to feed it rather than starve it.

I know these claims sound bad. But if you reject them because they sounds bad, you are only proving my point.

(5 COMMENTS)

May 1, 2014

What If Firms Could Opt Out of Sexual Harassment Law?, by Bryan Caplan

My best guess: Small, for-profit firms would soon opt out, given the chance. They have little reason to worry about bad publicity, and the laws are quite inefficient: workers rarely value the right to sue their employer for harassment more than their employers value immunity to such lawsuits. To maintain worker morale, most such firms would loudly declare an internal policy against sexual harassment: "Here at the Widget Corporation, we strongly oppose sexual harassment. But from now on we're going to handle the problem internally."

Larger firms that fret about their public image, in contrast, would wait and see what happens. Over the course of 5-10 years, though, they'd probably opt out too - and cry that their callous competitors forced their hand.

The main hold-out, I suspect, would be non-profits - especially universities. Their main customers, after all, are parents - and few parents want to send their kids to a school that leaps at the chance to evade sexual harassment laws. Internally, moreover, universities are full of people who are ideologically committed to things as they are. Pragmatic administrators would be loathe to cross them.

Of course, I could be wrong. So tell me: What would happen if firms could opt out of sexual harassment law?

(13 COMMENTS)

April 28, 2014

Ayn Rand in the Happy Lab, by Bryan Caplan

They do not want to own your fortune, they want you to lose it; they do not want to succeed, they want you to fail; they do not want to live, they want you to die; they desire nothing, they hate existence, and they keep running, each trying not to learn that the object of his hatred is himself.I couldn't help but recall this passage while reading psychologist Sonya Lyubomirsky's new The Myths of Happiness . Lyubomirsky ran an experiment where (a) participants were given a task, (b) a performance rating, and (c) their partner's performance rating. The catch: The so-called "performance ratings" had nothing to do with performance. They were randomly assigned to measure subjects' response to social comparison. Lyubomirsky:

After they were finished, we created a small deception by leading each volunteer to believe that he or she had performed very poorly on this task (that is, that they received an average rating from judges of 2 out of 7), but also to believe that the second volunteer had performed even worse than they had (receiving a disappointing rating of only 1). By contrast, a second group of volunteers were led to believe that they had performed extremely well (having obtained an average score of 6 out of 7), but that their peer had performed even better (receiving an outstanding score of 7)...At first, the findings seem banal:

To analyze the data, I divided my participants into those who, before performing, reported being very happy and those who reported being relatively unhappy. When I examined the "before" and "after" data of my very happy participants, I found that those who learned that they had performed very poorly reported feeling less positive, less confident, and more sad after the study was over. Their reaction to ostensible failure was perfectly natural and not at all surprising. By contrast, the very happy participants who learned that they had performed extremely well (a 6 out of 7) subsequently felt better on all dimensions, and, notably, learning that someone did even better did not dilute the pleasure of their ostensible success.Then things turn Randian:

The results for my unhappiest participants, however, were dramatic. Their reactions, it appears, were governed more by the reviews they had given their peers than by their own feedback. Indeed, the study paints a stark and quite unpleasant portrait of an unhappy person. My unhappiest volunteers reported feeling happier and more secure when they received a poor evaluation (but heard that their peer did even worse) than when they had received an excellent evaluation (but heard that their peer did even better). It appears that unhappy individuals have bought into the sardonic maxim attributed to Gore Vidal: "For true happiness, it is not enough to be successful oneself... One's friends must fail."Rand's positive theory of happiness is largely wrong, as she could have readily discovered by carefully attending to her own bitter experiences. But lets look on Rand's bright side. Outlandish though they seem, empirical psych supports some of her most Manichean accusations.

(14 COMMENTS)

April 27, 2014

Cowen and Crisis Reconsidered, by Bryan Caplan

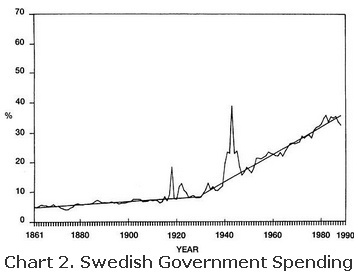

The ratchet effect becomes much stronger in the twentieth century thanTyler's words swiftly changed my mind. The Swedish case seemed devastating... so devastating I never bothered to check the data. Last night, however, GMU prodigy Nathaniel Bechhofer informed me that the key facts were right in Econlib's own Concise Encyclopedia of Economics . Gordon Tullock's article on "Government Spending" provides the shocking Swedish statistics:

before. Furthermore most forms of governmental growth probably would

have occurred in the absence of war. The example of Sweden is

instructive. Sweden avoided both World Wars, and had a relatively mild

depression in the 1930s, but has one of the largest governments,

relative to the size of its economy, in the developed world. The war

hypothesis also does not explain all of the chronology of observed

growth. Many Western countries were well on a path towards larger

government before the First World War. And the 1970s were a significant

period for government growth in many nations, despite the prosperity and

relative calm of the 1960s.

Yes, Sweden stayed out of the actual fighting during the two world wars. But you'd never know it from their budget! Sweden spent almost as much avoiding the war as the combatants spent participating.

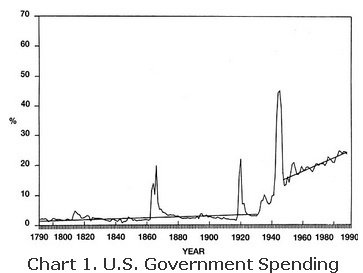

For the sake of comparison, check out the U.S. numbers for the same era. World War II led to a 25 percentage-point spike in government's share of GNP in Sweden, versus 35 percentage-points for the U.S.:

Of course, the history of Sweden is not final proof that Higgs was right all along. But the seemingly devastating Swedish counter-example is a red herring. The Swedes didn't fight, but they were still terrified, and they still turned to government to save them.

(0 COMMENTS)

April 25, 2014

George R.R. Martin's Pacifist Tendencies, by Bryan Caplan

I'd go further, but I'm clearly not just reading my own views into his stories.You're a congenial man, yet these books are incredibly

violent. Does that ever feel at odds with these views about power and

war?The war that Tolkien wrote about was a war for the

fate of civilization and the future of humanity, and that's become the

template. I'm not sure that it's a good template, though. The Tolkien

model led generations of fantasy writers to produce these endless series

of dark lords and their evil minions who are all very ugly and wear

black clothes. But the vast majority of wars throughout history are not

like that. World War I is much more typical of the wars of history than

World War II - the kind of war you look back afterward and say, "What

the hell were we fighting for? Why did all these millions of people have

to die? Was it really worth it to get rid of the Austro-Hungarian

Empire, that we wiped out an entire generation, and tore up half the

continent? Was the War of 1812 worth fighting? The Spanish-American War?

What the hell were these people fighting for?"

There's only a few wars that are really worth what they cost.

HT: Zac Gochenour

(3 COMMENTS)

"The 'liquidity trap' only is a mental constraint in the heads of central bankers.", by Bryan Caplan

April 24, 2014

Too Many, by Bryan Caplan

There are however some exceptions to the human exception. The oddest and broadest: It is socially acceptable to say the words, "There are too many people." In most of American society, similarly, it is socially acceptable to say, "There are too many immigrants." It can also be OK for either men or women to say, "There are too many men here."

Other exceptions to the human exception?

(22 COMMENTS)

April 23, 2014

Talking to Mark Krikorian, by Bryan Caplan

1. Mark has good manners and radiates little anger. Immigration opponents would be more influential if they emulated him.

2. Fortunately, such emulation is highly unlikely to happen. The Occupy Wall Street people would rather alienate receptive audiences than wear suits and cut their hair. Anti-immigration people would rather alienate receptive audiences than be polite and control their tempers.

3. Lawyers' classic strategy is, "When the facts are against you, argue the law. When the law is against you, argue the facts. When the facts and the law are against you, change the subject." Mark argues like a lawyer.

Exhibit A: I made strong claims about the likely effect of open borders on total production and average living standards. Mark never disputed my claims. But neither did he say anything like, "The overall economic benefits of immigration are indeed astronomically positive. But the downsides are even more astronomical."

Exhibit B: Mark began by claiming that open borders would clearly and massively expand the size of government. But when I raised the view - voiced by many leftist European social scientists - that immigration undermines the welfare state by reducing social cohesion, Mark did not demur. Instead, he said that reducing social cohesion is very bad.

Exhibit C: Mark rightly rejected the "Jobs Americans Won't Do" (JAWD) argument. I agreed, then pointed out how to repair the argument. Namely: While sufficiently high wages could indeed persuade Americans to do virtually any job, employers respond to higher wages by hiring fewer workers. Call this the "Jobs that Won't Be Done At All if Only Americans Can Do Them" (JTWBDAAIOACDT) argument. If nannies earned $30,000 a year, for example, most families that now have nannies would do without. Mark's response was basically, "Who cares if upper-middle class families have nannies?"

Exhibit D: Mark pointed to California to demonstrate that high immigration leads to a bloated welfare state. When I asked about high-immigration, low-welfare Texas, he didn't respond.

4. Can I honestly say I'm any less lawyerly? Yea. I'm happy to admit that the evidence on the immigration-welfare state connection is mixed. I'm happy to point out the flaws in the JAWD argument. Indeed, I'm happy to deliver an opening statement that I know most Americans would find unpersuasive, if not frightening. Why? Because I think my opening statement is true. Getting people to the right conclusion for the wrong reasons is not good enough for me - and getting anyone to the right conclusion for the right reasons is good in itself.

5. I would like to have lunch with Mark and one of the illegal immigrants I know. I'd open the conversation with, "Why do you want the government to force this person to leave the country?" Would Mark really tell him, "Sorry, your presence undermines our patriotic solidarity, so you have to go"? Or what?

6. If Mark brought me to lunch with an unemployed low-skilled native, I really would tell him, "Sorry you lost your job, but foreigners have as much a right to work as you do." It needs to be said.

7. The debate would have been better if we cross-examined each other instead of delivering opening statements. Some questions I wish I'd had time to ask:

a. How much would open borders have to raise living standards before you'd reconsider? Doubling GDP clearly doesn't impress you. What about tripling? A ten-fold increase?

b. Suppose the U.S. had a lot more patriotic solidarity. In what specific ways would it be better to live here?

c. Aren't there any practical ways you could unilaterally adopt to realize their benefits? Are you using them?

d. Do you really think low-immigration parts of the U.S. are nicer places to live? If so, why aren't more natives going there? Why don't you?

e. Doesn't patriotic solidarity often lead people to unify around bad ideas? Think about the Vietnam War or Iraq War II. If so, why are you so confident that we need more patriotic solidarity rather than less?

f. I'm sincerely puzzled. How exactly is discriminating against blacks worse than discriminating against foreigners?

g. Suppose you were debating a white nationalist who said, "I agree completely with Mark, except I value racial solidarity rather than patriotic solidarity." What would you say to change his mind? Would you consider him evil if he didn't?

h. Suppose you can either save one American or x foreigners. How big does x have to be before you save the foreigners?

i. In what sense is letting an American employer hire a foreigner is an act of charity?

j. Suppose the U.S. decided to increase patriotic solidarity by refusing to admit Americans' foreign spouses: "Americans should marry other Americans." Would that be wrong?

8. Mark denies being "anti-immigrant." We wouldn't call a morbidly obese man "anti-food" for going on a diet. Why is he "anti-immigrant" because he wants fewer immigrants?

Simple: Because we subject complaints about human beings to stricter scrutiny than complaints about inanimate objects. If someone said there were "too many" blacks, Jews, or gays in America, everyone would identify them as anti-black, anti-Semitic, or homophobic. When Mark says there are too many immigrants, we rightly label him as anti-immigrant.

9. Though anti-immigrant, I doubt Mark actively hates them. What I sense, rather, is strong yet polite distaste for foreigners. He's like a husband who makes nice with his mother-in-law, yet groans whenever he finds out she's visiting. The key difference: Mark is hypersensitive. The husband feels fine once his mother-in-law is out of his house, but Mark's distaste for foreigners is so intense that he wants them out of his entire country.

(13 COMMENTS)

America Should Open Its Borders: My Opening Statement for the Reason Immigration Debate, by Bryan Caplan

America Should Open its Borders

Under

current U.S. law, it is illegal for a foreigner to work for a willing American

employer or rent from a willing American landlord without government

permission. For most foreigners, this

permission is impossible to obtain. As a

result, hundreds of millions who want to move here are stuck in their birth

countries. Most would-be immigrants are

desperately poor, but could easily work their way out of poverty if they were here.

I say

America should open its borders to them all.

Every other country should do the same.

But given America's illustrious open borders tradition, it is fitting

that we lead the way. My case for open

borders comes down to two claims: One moral, one empirical.

The moral

claim: Immigration restrictions are

unjust. Letting people work for

willing employers and rent from willing landlords is not charity. It's basic decency. And even though foreigners wickedly chose the

wrong parents, they're clearly people.

The empirical

claim: Being just to foreigners would

cost us less than nothing. When

people immigrate here to work, they simultaneously enrich themselves and

us. Though a high-skilled worker

enriches us more than a low-skilled

worker, the typical low-skilled worker is far better nothing - and there's plenty

of room for everyone.

Let's start

with our laws' injustice. Imagine the U.S.

made it illegal for blacks, women, or Jews to take certain jobs or live in

certain neighborhoods. You wouldn't

merely object. You'd be appalled. Whatever your specific moral views, you know

it's wrong to prohibit a black, woman, or Jew from accepting a job or renting a

home.

My

question: How is mandatory discrimination against foreigners against less wrong

than mandatory discrimination against blacks, women, or Jews? The leading rationale is that "we should take

care of our own first." That might be a

good argument against sending foreigners welfare checks. But it's an Orwellian argument for stopping

immigrants from working or renting here.

Minding your own business when two strangers trade with each other is

not a form of charity.

This is not

a weird libertarian point. The fact that

I never put Krazy Glue in the locks of the Center for Immigration Studies does

not make me one of its donors.

Friends of

immigration restrictions often compare nations to families. I'll accept their analogy. I love my children more than I love the rest

of you put together. This is a good

reason to worry that I'll treat you

unjustly if there's ever a conflict of interest. But it's no excuse for me to treat you unjustly. "I want my beloved son to get this job" does

not justify slashing rival candidates' tires the morning of the final

interview. The same goes for immigration

policy. Your love for Americans may tempt you to treat foreigners unjustly,

but it's no excuse for treating them unjustly.

We should

refrain from unjust actions even if they're in our self-interest. In the zombie apocalypse, you shouldn't eat

me because you're hungry and I'm wimpy.

Yet in the real world, fortunately, justice usually pays. Becoming a violent criminal is a poor path to

prosperity. So were Jim Crow laws. What about immigration laws?

This brings

me to my second big claim: Being just to foreigners would cost us less than

nothing. Everyone has his problems. Opponents of immigration spend most of their

time staring at foreigners to find fault.

But if you pick a random would-be immigrant - even a random illiterate peasant

- and calmly weigh his positives and negatives for us, the sum is

positive.

To see why,

you need a little labor economics. Hard

fact: Immigration laws trap people in countries where workers produce far below their potential. When Haitians move to the United States,

their wages easily increase twenty-fold.

That's not +20%. It's plus

+2000%. The reason isn't that American

employers are nicer than Haitian employers.

The reason is that Haitians produce vastly more in America than they do

in Haiti. Think about how little you could contribute to the world

economy if you were stuck in Haiti.

How much

would total production rise under open borders?

Every economist who asks the question reaches an astronomical

answer. A typical estimate is that

global free migration would double

global production. If the U.S. alone opened

its borders, the global effect would naturally be smaller, but the national

effect would be even larger.

How is

vastly higher production in your self-interest?

The obvious reason: More stuff produced means more stuff consumed. This is not trickle-down economics; it is

Niagara Falls economics. Production is

what distinguishes the rich world of today from the wretched world of the past. If half the workforce suddenly retired, it

would be bad for you.

Production

always has its naysayers. When

driverless cars arrive, you can count on people to complain that they're

putting truck-drivers out of work. But

by this logic, we'd be richer if law-makers in the 19th-century

banned the tractor. The fundamental truth

of economic growth: While innovation often hurts immediate competitors, it is the fountainhead of rising prosperity.

Doesn't

immigration hurt workers by increasing the supply of labor? It's complicated, because immigration also

increases labor demand. After all,

workers buy stuff. To grasp

immigration's full effect, keep both eyes on production. Trapping Mexican farm workers on primitive

Mexican farms starves them and us. It's

far better if they move here and enrich themselves by putting better and

cheaper food on our tables.

Like

driverless cars, immigration can impoverish some Americans while enriching the

rest. As a native-born research

professor, I ought to know. Thanks to an

immigration loophole, about half the people in my occupation are foreign-born. Closing that loophole would give my career a big

shot in the arm. Most labor economists similarly

find that lower immigration helps native high school dropouts.

How can I

concede this yet insist that illiterate foreigners are far better than nothing?

Because unlike Mark, I don't look at a

would-be immigrant and ask, "Is there any possible downside?" Instead, I ask, "Is his net effect positive?" Every innovation

is bad for someone, but innovation is still a good thing. Every immigrant is bad for someone, but immigrants

are still good thing.

Why must I

be so radical? In part, because this is

a matter of basic human rights. We don't

have to give foreigners welfare or let them vote. But treating fellow human beings like

criminals for working without government permission is unconscionable.

What

cements my radicalism, though, is that doing the right thing would cost us less

than nothing. If you think production

leads to poverty, open borders should terrify you. Otherwise, the sooner America opens its

borders, the better.

(0 COMMENTS)

April 22, 2014

Crazy Immigration, by Bryan Caplan

This seems like a crazy policy. Imagine the chaos of six billion people migrating in unison! Yet strangely, analogous policies are already on the books, and the system works so well few complain about it.

Consider: Under current U.S. law, over three hundred million people are free to move to my home town of Oakton, Virginia. Population: About 34,000. Thus, the population of Oakton could legally increase by a factor of almost 9000. Under the status quo, moreover, there is no waiting period. If everyone in the United States decides to move to Oakton today, they're free to do so.

How come no one's worried about the swamping of Oakton? Part of the reason, of course, is that there's no pent-up demand to live in Oakton. The deeper reason, though, is that housing markets would peacefully regulation migration even if the whole country suddenly decided Oakton was an earthly paradise.

If demand for living in Oakton suddenly spiked, the market provides a short-run and a long-run solution. In the short-run, a demand spike leads to higher rents and housing prices, discouraging relocation without depriving anyone of the right to relocate. In the long-run, these higher real estate prices provide an incentive for construction firms to build more housing. As a result, housing prices would gradually decline from their temporary high - and the population of newly-popular Oakton would gradually swell.

Over the course of a decade or two, market forces could easily transform Oakton into a metropolis a hundred times its current size. There's plenty of room to do so: Oakton has over 25% of the land area of Manhattan. Is such a population growth realistic at the national level? Yes. If the continental U.S. had the population density of suburban Oakton, its total population would be about ten billion - more than the current population of the planet.

True, as I've explained before, most people on earth don't want to immigrate anytime soon. Due to diaspora dynamics, immigration from a country starts out low, then gradually snowballs. It took about a century of open borders with Puerto Rico before half its people moved here. My point, though, is that housing markets provide the necessary incentives for massive yet orderly migration. These markets already quietly guide internal migration. They are quite able to do the same for external migration. Let them come, and we will build it - for the market price.

(6 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers