Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 147

May 14, 2014

The Improvident Rich, by Bryan Caplan

When Forbes compared its list of the wealthiest Americans inHT: David Levey

1982 and 2012, it found that less than one tenth of the 1982 list was

still on the list in 2012, despite the fact that a significant majority

of members of the 1982 list would have qualified for the 2012 list if

they had accumulated wealth at a real rate of even 4 percent a year.

They did not, given pressures to spend, donate, or misinvest their

wealth. In a similar vein, the data also indicate, contra Piketty, that

the share of the Forbes 400 who inherited their wealth is in sharp decline.

(3 COMMENTS)

May 13, 2014

Myth of the Rational Voter: The Animated Series, Part 2, by Bryan Caplan

(0 COMMENTS)

May 12, 2014

The Cartoon Introduction to Climate Change, by Bryan Caplan

Still, this book feels like a missed opportunity. He spends so much time on the climate science that he has little time left for the economics. Perhaps as a result, Bauman neglects many economic insights that climate activists sorely need to hear. Especially:

1. We can use cost-benefit analysis to put climate change in perspective. Multiple leading economists have done cost-benefit analysis of climate change, and as far as I've heard even high estimates are a small percentage of global GDP. Maybe I've heard wrong, but why didn't Bauman review the point estimates and confidence intervals of the main studies?

2. Cost-benefit analysis is sensitive to discount rates. The graphic format seems like a great way to teach this vital yet off-putting issue. I immediately picture multiple variants on the Wheat and Chessboard Problem. But the book avoids the topic.

3. Insurance is NOT a no-brainer. Yes, insurance sounds wonderful; that's Social Desirability Bias for you. But economics tells us that the desirability of insurance depends on the coverage and the cost. That's why most economists (including famed behavioral economist Matt Rabin) consider extended warranties the height of stupidity. Instead of exposing readers to these inconvenient truths - and possibly trying to surmount them - Bauman repeats the cliche that "It's a good idea to buy insurance, just in case." Then he adds, "It turns out that our best insurance policy is to reduce emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases," without any cost-benefit analysis to speak of. Not good.

4. Leading techno-fixes really do look vastly cheaper than abatement. (see here, here, and here for starters) Bauman has two pages on geoengineering, but hastily dismisses it as not "terribly realistic." [UPDATE: In the comments, Bauman points out that the "not terribly realistic" claim applies to the idea that geoengineering is a "painless cure-all," not geoengineering per se. My bad.] But why are eighteen-mile garden hoses less "realistic" than making a serious dent in the world's expected 250% increase in fossil fuel consumption by 2100?

5. National emissions regulations can have perverse global effects. If relatively clean countries switch to clean energy (via command-and-control regulations, cap-and-trade, pollution taxes, or green norms), fossil fuels don't vanish. Instead, their world price falls - encouraging further consumption in relatively dirty countries. The net effect? I was hoping Bauman would tell us, but he didn't even raise the issue.

6. Expressive voting is a big deal. A lot of green activism is clearly expressive - focused on showing commitment rather than improving outcomes. When I was a kid, our family routinely drove to the recycling center to drop off a few bottles. Bauman really should have explained Brennan and Lomasky's expressive voting model - not to dismiss reformism, but to alert readers to the danger of loudly sacrificing to "help the planet" without verifying the effectiveness of the sacrifice.

As usual, I genuinely liked this Cartoon Introduction. I was entertained and enlightened. But economics offer many lessons that environmentalists need to hear - and Bauman largely fails to teach them these vital lessons.

(5 COMMENTS)

May 11, 2014

Exploring Elitist Democracy: The Latest from Gilens and Page, by Bryan Caplan

While this body of research is rich and variegated, it can loosely be divided into four families of theories: Majoritarian Electoral Democracy, Economic Elite Domination, and two types of interest group pluralism - Majoritarian Pluralism, in which the interests of all citizens are more or less equally represented, and Biased Pluralism, in which corporations, business associations, and professional groups predominate) Each of these perspectives makes different predictions about the independent influence upon U.S. policy making of four sets of actors: the Average Citizen or "median voter," Economic Elites, and Mass-based or Business-oriented Interest Groups or industries.The dependent variables are straight out of Gilens' earlier work:

Gilens and a small army of research assistants gathered data on a large, diverse set of policy cases: 1,779 instances between 1981 and 2002 in which a national survey of the general public asked a favor/oppose question about a proposed policy change. A total of 1,923 cases met four criteria: dichotomous pro/con responses, specificity about policy, relevance to federal government decisions, and categorical rather than conditional phrasing. Of those 1,923 original cases, 1,779 cases also met the criteria of providing income breakdowns for respondents, not involving a Constitutional amendment or a Supreme Court ruling (which might entail a quite different policy making process), and involving a clear, as opposed to partial or ambiguous, actual presence or absence of policy change.As far as I can tell, the interest group preferences are also straight out of Gilen's earlier work:

For each of the 1,779 instances of proposed policy change, Gilens and his assistants drew upon multiple sources to code all engaged interest groups as "strongly favorable," "somewhat favorable," "somewhat unfavorable," or "strongly unfavorable" to the change. He then combined the numbers of groups on each side of a given issue, weighting "somewhat" favorable or somewhat unfavorable positions at half the magnitude of "strongly favorable or strongly unfavorable positions.This coding is the project's main leap of faith. When Gilens measured the relative influence of voters of different income levels, he had public opinion data for each income level. For interest groups, in contrast, Gilens and assistants impute opinions. Still, I don't have a better idea. If we run with their approach, what do we find?

First, middle-class Americans' preferences are highly correlated with rich Americans' preferences - but not interest groups' preferences:

It turns out, in fact, that the preferences of average citizens are positively and fairly highly correlated, across issues, with the preferences of economic elites (see Table 2.) Rather often, average citizens and affluent citizens (our proxy for economic elites) want the same things from government. This bivariate correlation affects how we should interpret our later multivariate findings in terms of "winners" and "losers." It also suggests a reason why serious scholars might keep adhering to both the Majoritarian Electoral Democracy and the Economic Elite Domination theoretical traditions, even if one of them may be dead wrong in terms of causal impact. Ordinary citizens, for example, might often be observed to "win" (that is, to get their preferred policy outcomes) even if they had no independent effect whatsoever on policy making, if elites (with whom they often agree) actually prevail.Second, each theory looks good in isolation:

But net interest group stands are not substantially correlated with the preferences of average citizens. Taking all interest groups together, the index of net interest group alignment correlates only a non-significant .04 with average citizens' preferences! (See Table 2.) This casts grave doubt on David Truman's and others' argument that organized interest groups tend to do a good job of representing the population as a whole. Indeed, as Table 2 indicates, even the net alignments of the groups we have categorized as "mass-based" correlate with average citizens' preferences only at the very modest (though statistically significant) level of .12.

When taken separately, each independent variable - the preferences of average citizens, the preferences of economic elites, and the net alignments of organized interest groups - is strongly, positively, and quite significantly related to policy change. Little wonder that each theoretical tradition has its strong adherents.Third, average citizens lose almost all apparent influence if you do multiple regression:

These results suggest that reality is best captured by mixed theories in which both individual economic elites and organized interest groups (including corporations, largely owned and controlled by wealthy elites) play a substantial part in affecting public policy, but the general public has little or no independent influence.Check out the multiple regression results:

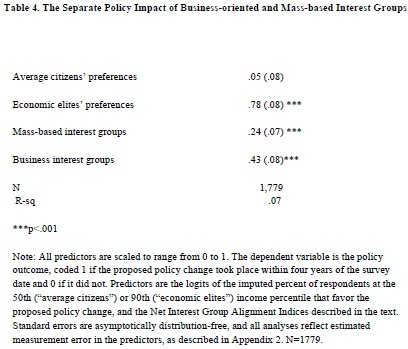

Fourth, if you break interest groups into "business" and "mass" categories, the former have more power than the latter:

The influence coefficients for both mass-based and business-oriented interest groups are positive and highly significant statistically, but the coefficient for business groups is nearly twice as large as that for the mass groups. Moreover, when we restricted this same analysis to the smaller set of issues upon which both types of groups took positions - that is, when we considered only cases in which business-based and mass-based interest groups were directly engaged with each other - the contrast between the estimated impact of the two types of groups was even greater.Punchline regressions:

Conclusion:

By directly pitting the predictions of ideal-type theories against each other within a single statistical model (using a unique data set that includes imperfect but useful measures of the key independent variables for nearly two thousand policy issues), we have been able to produce some striking findings. One is the nearly total failure of "median voter" and other Majoritarian Electoral Democracy theories. When the preferences of economic elites and the stands of organized interest groups are controlled for, the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.Gilens and Page's latest paper is hardly the final word. Their results for interest groups hinge on their own coding - an inherently opaque process. Still, they offer novel evidence on big questions. They've definitely got my attention. They deserve yours, too.

The failure of theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy is all the more striking because it goes against the likely effects of the limitations of our data. The preferences of ordinary citizens were measured more directly than our other independent variables, yet they are estimated to have the least effect.

Nor do organized interest groups substitute for direct citizen influence, by embodying citizens' will and ensuring that their wishes prevail in the fashion postulated by theories of Majoritarian Pluralism. Interest groups do have substantial independent impacts on policy, and a few groups (particularly labor unions) represent average citizens' views reasonably well. But the interest group system as a whole does not.

(6 COMMENTS)

May 10, 2014

Me, Gilens, and Salon, by Bryan Caplan

I find Gilens' results not only intellectually satisfying, but hopeful.Now these posts have inspired an amusing Salon profile of me, written by the New America Foundation's Michael Lind. While Steven White's 2007 profile of me for Generation Progress showed deeper understanding and better eye for detail, Lind's summary of my views is largely accurate and rather flattering. Lind:

If his results hold up, we know another important reason why policy is

less statist than expected: Democracies listen to the relatively

libertarian rich far more than they listen to the absolutely statist

non-rich. And since I think that statist policy preferences rest on a

long list of empirical and normative mistakes, my sincere reaction is to

say, "Thank goodness." Democracy as we know it is bad enough.

Democracy that really listened to all the people would be an

authoritarian nightmare.

Can Caplan fill the philosophical void left by Nozick's defection

from libertarianism? I think he can. In what follows I will make the

case for what might be called Caplanism, recognizing that Caplan himself

might not be consistent enough to follow the logic of his own thinking

to its conclusions. (Marx claimed he was not a Marxist).The great contribution of Caplanism to libertarian thought and argument is the observation that democracy, if sufficiently corrupted by the rich,

might -- just might -- be tolerable. Let us call this equivalent of

Kant's Categorical Imperative or the Maximin Principle of John Rawls Caplan's Tolerability Principle.That

libertarianism is incompatible with democracy is an empirical

observation on which libertarians can agree with progressives, centrists

and non-libertarian conservatives. After all, in every modern

democracy, including the U.S., government tends to account for somewhere

between 35 and 50 percent of GDP on such "national socialism" (to use

Caplan's terms) as universal health care, minimum public pensions and

public education.

Money can't buy publicity like this:

Caplanism represents a great philosophical breakthrough for the

Koch-subsidized intelligentsia of the libertarian right. Caplanism

allows libertarians to embrace both Pinochet's Chile and the United

States, without contradiction, on the grounds that in both Pinochet's

Chile and today's United States the preferences of the rich have trumped

those of the majority.Caplanism also frees libertarian scholars

like Caplan himself from being embarrassed about the fact that almost

all of them are paid, directly or indirectly, by a handful of angry,

arrogant rich guys who fund anti-government propaganda because they

think they are overtaxed. Caplanism allows the subsidized libertarian

intelligentsia to declare, "Yes, we are indeed spokesmen for plutocracy --

and a good thing, too, because a plutocratic democracy is the only kind

of democracy worth having!"For all of these reasons, I believe

that Bryan Caplan deserves to be studied as one of the most

representative thinkers of our money-dominated era. Our squalid age of

plutocratic democracy has found a thinker worthy of it.

Yes, it would have been nice if Lind talked more about where I go wrong, and he gratuitously insults many fellow libertarians. But as a firm believer in the adages "All publicity is good publicity," and "Don't look a gift horse in the mouth," I'm not only pleased, but grateful.

May 9, 2014

"Hollowing Out": A Global Perspective, by Bryan Caplan

The key graph:

Discussion:

What parts of the global income distribution registered the largest gains between 1988 and 2008? As the figure shows, it is indeed among the very top of the global income distribution and among the 'emerging global middle class', which includes more than a third of the world's population, that we find most significant increases in per-capita income. The top 1 per cent has seen its real income rise by more than 60 per cent over those two decades. However, the largest increases were registered around the median: 80 per cent real increase at the median itself and some 70 per cent around it. It is between the 50th and 60th percentiles of global income distribution that we find some 200 million Chinese, 90 million Indians and about 30 million people each from Indonesia, Brazil and Egypt. These two groups - the global top 1 per cent and the middle classes of the emerging market economies - are indeed the main winners of globalization.So has the global economy "hollowed out"? A pessimist would say so. Yet a more balanced view is that 80% of the global population has done great over the last two decades - and the remaining 20% are not so much "losers" as "nonwinners" or "marginal winners".

The surprise is that those in the bottom third of global income distribution have also made significant gains, with real incomes rising between over 40 per cent and almost 70 per cent. The only exception is the poorest 5 per cent of the population, whose real incomes have remained the same. This income increase at the bottom of the global pyramid has allowed the proportion of what the World Bank calls the absolute poor (people whose per-capita income is less than 1.25 PPP dollars per day) to go down from 44 per cent to 23 per cent over approximately the same 20 years.

But the biggest losers (other than the very poorest 5 per cent), or at least the 'nonwinners', of globalization were those between the 75th and 90th percentiles of global income distribution, whose real income gains were essentially nil. These people, who may be called a global upper middle class, include many from former communist countries and Latin America, as well as those citizens of rich countries whose incomes stagnated.

Milanovic then insightfully breaks down the distribution by country:

Who are the people in the global top 1 per cent? Despite its name, it is a less 'exclusive' club than the US top 1 per cent: the global top 1 per cent consists of more than 60 million people, the US top 1 per cent only 3 million. Thus, among the global top 1 per cent, we find the richest 12 per cent of Americans (more than 30 million people) and between 3 and 6 per cent of the richest Britons, Japanese, Germans and French. It is a 'club' that is still overwhelmingly composed of the 'old rich' world of Western Europe, Northern America and Japan. The richest 1 per cent of the embattled euro countries of Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece are all part of the global top 1 percentile. The richest 1 per cent of Brazilians, Russians and South Africans belong there too.Fascinating stuff. My main thought: Milanovic's results are a Rorschach test for sheer misanthropy. If you like human beings - as I do now - you'll look at Figure 4 and say, "Wow, living standards are swiftly growing for most of mankind - especially the poor." If you dislike human beings - as I did in high school - you'll look at Figure 4 and say, "Horrors, living standards are stagnant for the 80th percentile, but the super-rich are making out like bandits."

To which countries and income groups do the winners and losers belong? Consider the people in the median of their national income distributions in 1988 and 2008. In 1988, a person with a median income in China was richer than only 10 per cent of the world's population. Twenty years later, a person at that same position within Chinese income distribution was richer than more than half of the world's population. Thus, he or she leapfrogged over more than 40 per cent of people in the world.

For India the improvement was more modest, but still remarkable. A person with a median income went from being at the 10th percentile globally to the 27th. A person at the same income position in Indonesia went from the 25th to 39th global percentile. A person with the median income in Brazil gained as well. He or she went from being around the 40th percentile of the global income distribution to about the 66th percentile. Meanwhile, the position of large European countries and the US remained about the same, with median income recipients there in the 80s and 90s of global percentiles...

Who lost between 1988 and 2008? Mostly people in Africa, some in Latin America and post-communist countries. The average Kenyan went down from the 22nd to the 12th percentile globally, the average Nigerian from the 16th to 13th percentile.

20/20 hindsight: No one should be like I was in high school.

(2 COMMENTS)

Myth of the Rational Voter: The Animated Series, by Bryan Caplan

Please enjoy... and promote!

(6 COMMENTS)

May 7, 2014

Meant for Each Other: Open Borders and Western Civilization, by Bryan Caplan

Meant for Each Other: Open Borders

and Western Civilization

The

Institute for the Study of Western Civilization has a powerful statement on its

webpage: "Western civilization has remade the world. Most of the West's

inhabitants live lives of which their ancestors could only dream: doubly long,

rich in diet, teeming with comforts and diversions, and, most of all, endowed

with the gift of liberty--not just for a privileged few, but for the many."

Reading

this passage, I found myself, as Keynes told Hayek, "not only in agreement, but

in deeply moved agreement."

Unfortunately, the Institute's fine words embody a major oversight: In

the current world, Western civilization still only belongs to the privileged

few. Most of the world's inhabitants are

not born in Western nations - and Western nations' laws make it almost

impossible for more than a tiny minority to immigrate to prosperity and

freedom.

My

position: The world's nations - including of course the United States - should

abolish their immigration laws. Anyone

willing to pay for transportation should be able to travel here legally, anyone

willing to pay for housing should be able to live here legally, and anyone who

finds a willing employer should be able to work here legally.

If I can't

sell you on this radical open borders position, though, I won't get mad. Instead, I'll be an economist, trying to

bargain you into as much deregulation of immigration as you can stomach.

Why should

we grant foreigners the rights to travel, live, and work where they want? The same reason we should grant these rights

to women, blacks, and Jews: They're human beings and they count. Is this asking too much? No.

I'm not proposing that we give foreigners

homes or jobs. I'm proposing that we allow

foreigners to earn these worldly

goods from willing native landlords and employers. Under current law, housing and employment discrimination

against foreigners isn't just legal; it's mandatory. Why?

Because the foreigners chose the wrong parents. How horrible is that?

Of course,

plenty of horrible-sounding things are actually good. Like amputating a leg with gangrene. Are immigration restrictions like that? Maybe.

So let's consider the leading complaints about immigration. For each complaint, I answer two

questions. First, how real is the

problem? Second, assuming the problem is

real, are there cheaper and more humane remedies than lifelong exile from

Western civilization?

The leading

complaint is probably that mass immigration leads to poverty. Virtually every economist who's thought about

this reaches the opposite conclusion: Open borders would massively enrich the

world. A typical estimate is that free

migration would DOUBLE global GDP. Why? Because the status quo traps most of the

world's labor in dysfunctional economies where people produce at a fraction of

their full potential. Moving a Haitian

to the U.S. easily increases his output by a factor of twenty. Hard to believe? How much could you produce in Haiti?

Would a

massive influx of foreign labor drive down native

living standards? It depends on what the

native does. Immigration of workers who

produce what you produce hurts

you. Immigration of workers who produce

what you consume helps you.

New immigration

is like new technology. Driverless cars will

be bad for taxi drivers, but enrich everyone else. The net effect, as the history of Western

civilization plainly shows, is clear-cut: Mass production is the mother of general

prosperity. Still worried? There's a cheaper and more humane remedy than

keeping foreigners out: Charge them an admission fee or surtax, then use the

proceeds to help displaced native workers.

The second

most popular complaint is that mass immigration is a massive burden on taxpayers. Milton Friedman himself famous declared, "You

cannot simultaneously have free immigration and a welfare state." The social science, however, tells a

different story: The average immigrant pays about as much in taxes as he uses

in benefits.

If this

seems hard to believe, consider two things.

First, other countries have already paid for adult immigrants'

education, so we don't have to. Second,

a lot of government services - most obviously defense and debt service - can be

consumed by a larger population for no extra charge. Still worried? There's a cheaper and more humane remedy than

keeping foreigners out: Make them eligible to work but not collect benefits.

Another

complaint, which I suspect has great resonance at the Institute for the Study of Western

Civilization, is that immigrants harm our culture. The data on English fluency is fairly clear:

While many first-generation immigrants are not fluent, second-generation

immigrants almost always are.

Broader

measures of culture are harder to pin down, but I'll say this: Western culture already

dominates the global marketplace.

Nationalists around the world use cultural protectionism to "level the

playing field," but most local cultures keep losing. The obvious reason: Western culture is

better, so people around the world choose it when it's on the menu. Part of the reason it's better, I hasten to

add, is the West's openness to

awesomeness. Anything good can join

the Western bandwagon. That's why Arabic

numerals are a triumph of Western civilization.

My

challenge to the fans of Western culture: Given its current global success, imagine

how much more dominant Western

culture would be if people around the world were free to vote with their feet

for whatever culture they prefer. Still

worried? There's a cheaper and more

humane remedy than keeping foreigners out: Admit anyone who passes a cultural

literacy test.

A final

common complaint is that immigrants will vote for bad policies - transforming

our country into one of the dysfunctional societies they fled. Here, the data do show that the foreign-born

are more economically liberal and socially conservative; they are, in a word,

less libertarian. But the difference is

moderate, and the foreign-born have very low voter turnout anyway. Furthermore, there is good evidence that

ethnic diversity reduces native

support for the welfare state. This is a

standard story about why the U.S. welfare state is smaller than Europe's: We're

a lot more diverse, and people don't like supporting outgroups. The net

political effect of immigration, then, is unclear. The data, moreover, show little effect. For every California, there's a Texas. Still worried?

There's a cheaper and more humane remedy than keeping foreigners out:

Admit them to live and work but not to vote.

I won't

sugarcoat things. Free migration is a

radical change. But radical change in

the direction of human freedom is as Western as Shakespeare. Freedom of religion was a radical

change. Abolition of slavery was a

radical change. Ending Jim Crow was a

radical change. Before they were tried,

people feared that such radical changes would destroy Western

civilization. After the changes were

tried, though, people realized that state religion, slavery, and mandatory

discrimination were never compatible

with Western civilization's commitment to individual freedom.

Imagine how

you would react if the world's governments denied you the right to live and work where you please because you chose

the wrong parents. Does that sound like

the glory of Western civilization to you?

I think not. Western civilization

cannot realize its full potential as long as Western governments require discrimination against most of

mankind. Open borders will bring Western

civilization to the world by bringing the world to Western civilization. Open borders and Western civilization are meant

for each other.

(28 COMMENTS)

May 5, 2014

My Moment with Gary Becker, by Bryan Caplan

In 1992, Gary Becker won the Nobel prize in economics for one big idea: "Economics is everywhere." He saw economics in discrimination; employers hire people they hate if the wage is right. He saw economics in crime; crooks rob banks because that's where the money is. He saw economics in education; students endure years of boring lectures because they're fascinated by higher pay after graduation. Perhaps most important, Becker saw economics in the family. Human beings plan their families on the basis of enlightened self-interest. Parents look at the world, form roughly accurate beliefs about the costs and benefits of kids, and make babies until they foresee that another would be more trouble than he's worth.

I'm a devotee of Gary Becker. Once when I was visiting the faculty club at the University of Chicago, he unexpectedly sat down for lunch. I barely stopped myself from blurting out, "Oh my God, you're Gary Becker!" Still, my idol doesn't always get things right. One pillar of his family economics is the assumption that the fewer kids you have, the better they'll be. Becker matter-of-factly speaks of the "quality/quantity trade-off." A central lesson of behavioral genetics, as we've seen, is that the trade-off is often illusory. Parents who believe otherwise base their family plans on misinformation. Is this merely one admittedly large oversight on Becker's part, or has the ability of enlightened self-interest to explain the family been oversold?

That lunch with Becker was an intellectual highlight of my life. A draft of Donohue and Levitt's "more abortion, less crime" paper was circulating. As soon as Becker heard the main idea, his economic genius started running around like a jackrabbit. My recollection is that he was skeptical, because he expected abortion to change the timing of births rather than their total number. Whatever Becker said, though, just being in his presence was awesome. Death sucks, and it's got to stop.

(2 COMMENTS)

May 4, 2014

Three Graphs About Trying and Failing, by Bryan Caplan

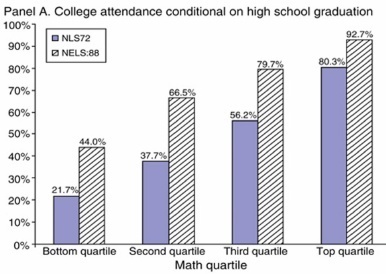

First, check out your probability of trying college if you finish high school.

Notice: By 1992, college is the default choice for most of the achievement distribution. Almost half of high school grads in the lowest quartile of math performance - and two-thirds in the second-lowest quartile - try college.

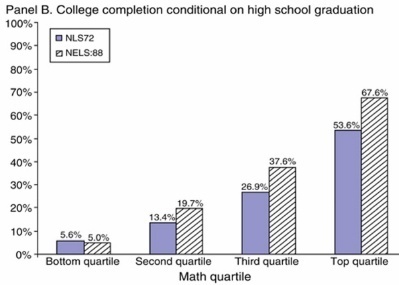

Next, look at the probability of finishing college if you try college. To get credit for finishing college, you have to graduate within eight years of

your cohort high school graduation. For the class of 1972, that's 1980;

for the class of 1992, that's 2000.

Probability

of success for the bottom half of the distribution started low in

absolute terms: about one-quarter for the bottom quartile, and one-third

for the second quartile. Over time, though, the bottom's success rates have gone from worse to awful: Barely 10% of those who try college manage to

get over the finish line.

Last, let's multiply the preceding probabilities together to get the the probability of finishing college if you finish high school.

Notice: Although kids in the bottom quartile became much more likely to try college, they became no more likely to finish. The fruits of effort for the second quartile are also underwhelming. How can this be? Because the probability of finishing college if you try college actually fell for the bottom three-quarters of the distribution! This is the fruit of America's

college-for-all mania.

Will I tell my kids to go to college? Sure. Does this make me a big hypocrite? Not at all. I shall follow the same principle I commend to others: Encourage high academic achievers to go to college, and urge the rest to do something else. More specifically: Push college for the top quartile, tolerate it for the third, discourage if for the second, and decry it for the first.

To be clear, this is prudential advice aimed at individual students, not a public policy recommendation. From a social point of view, I'd only push college on the top 5%. Unless, of course, the student loves learning enough to attend classes unofficially. The more of these rare unicorns on campus, the merrier.

(11 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers