Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 150

April 8, 2014

The Impolitic Wisdom of Simon Kuznets, by Bryan Caplan

Kuznets, however, saw specifically his task as working out how to measure national economic welfare rather than just output. He wrote:Why didn't Kuznets' view prevail? Coyle:It would be of great value to have national income estimates that would remove from the total the elements which, from the standpoint of a more enlightened social philosophy represent dis-service rather than service. Such estimates would subtract from the present national income totals all expenses on armament...

With this aim, Kuznets was out of tune with his times. Welfare was a peacetime luxury. This passage was written in 1937, when his first set of accounts was presented to Congress. Before long, the president would want a way of measuring the economy that did indicate the total capacity to produce but did not show additional government expenditure on armaments as reducing the nation's output. The trouble with the prewar definitions of national income was precisely that as constructed they would show the economy shrinking if private output available for consumption declined, even if the government spending required for the war effort was expanding output elsewhere in the economy. The Office of Price Administration and Civilian Supply, established in 1941, found that its recommendation to increase government expenditure in the subsequent year was rejected on this basis. Changing the definition of national income to the concept of GDP, rather than something more like Kuznets's original proposal, overcame this hurdle.By the way, if you are unfamiliar with Kuznets' life story, it's fascinating. But so are the variants of the Kuznets Curve and his proto-Simonian population economics.

(5 COMMENTS)

The Righteous Scofflaw, by Bryan Caplan

Let's consider them in order of popularity.

1. Strong presumption. The most popular theory is probably that breaking the law is only justified under desperate circumstances. As Ilya explains:

Some believe that there is a very strong presumption that can only beThis story has an obvious problem: Most of its explicit proponents routinely break laws for trivial reasons. Just look at the fraction of drivers who occasionally exceed the speed limit - and picture how they'd react if a passenger morally condemned them for driving 56 mph in a 55 mph zone.

overcome by extremely powerful countervailing considerations. For

example, perhaps southern blacks were justified in violating Jim Crow

laws in the days of segregation, because of the severe harm that those

laws inflicted on them. But ordinary Americans today are not justified

in violating laws that harm them in more modest ways.

In any case, as one of my favorite challenges suggests, illegal immigration easily overcomes even a strong presumption in favor of obeying the law:

If anything is enough to overcome the strong presumption, it surely is a2. Weak presumption. The theory most consistent with people's concrete moral reasoning is that legality only marginally tips the scales of righteousness. Ilya:

situation where obedience forces you and your family into life-long

poverty and oppression that you did nothing to deserve, and violation of

the law does not in itself harm anyone. The strong presumption theory

might still condemn illegal immigrants who come from advanced liberal

democracies, such as Canada or Britain. Life in these countries is at

worst only modestly less happy and free than in the United States. But

the vast majority of illegal immigrants are fleeing far worse condition -

often even worse conditions than African-Americans endured in the Jim

Crow era.

Many people implicitly assume that there is only a relatively weak moralUnder the weak presumption, the propriety of illegal immigration is a true no-brainer:

presumption in favor of obeying the law. If obeying a law is

inconvenient and violating it is unlikely to harm anyone, they believe

that violation is morally justified. That explains why most people

believe it is morally permissible to violate the speed limit laws, so

long as you don't drive so fast as to seriously endanger other drivers

and pedestrians. Strict compliance with the speed limit would be

annoying and inconvenient, and make it harder for us to get to our

appointments on time. Ditto for violations of various federal

regulations that ordinary citizens and small businesses routinely run

afoul of. Obeying all of these laws to the letter would be costly and

inconvenient, and most people believe it is all right to violate them in

cases where there is no significant harm to others.

[I]llegal immigrants have a much stronger case for violating immigration3. No presumption. Ilya closes with the decidedly unpopular view that legality is morally irrelevant:

laws than native-born citizens do for their routine violations of the

speed limit and various petty federal regulations. For most illegal

immigrants, obeying the law would harm them a lot more profoundly than

merely making it harder to get to work on time. It would consign them to lives of poverty and oppression in the Third World, a harsh fate imposed on them through no fault of their own, merely because they were born on the wrong side of a line on the map.

Finally, it is worth noting that scholars such as A. John Simmons and Michael Huemer arguePart of me wishes that Ilya spent more time on the latter theory. After all, it's true. But Ilya made the right choice. Why struggle to sell Washington Post readers on a new philosophy of law when their pre-existing philosophies lead to the same conclusion?

that there is no presumption in favoring of an obligation to obey the

law at all. They hold that a moral obligation to obey a law requires

something beyond merely the fact that it was enacted by a government,

even a democratically elected one.

(8 COMMENTS)

April 6, 2014

The Ghetto of Talent, by Bryan Caplan

While removing social and legal barriers often fails to release superlative achievement, sometimes it does. The most dramatic case of all: What transpired when the barriers of Europe's Jewish ghettos came crumbling down. Murray:

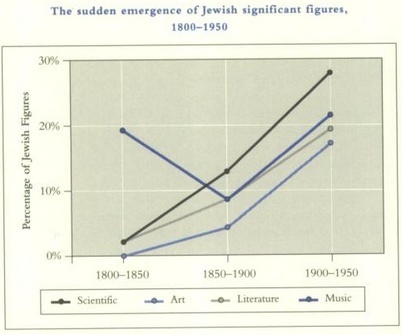

During the four decades from 1830 to 1870, when the first Jews to live in emancipation (or at least to live under less rigorously enforced suppression) reach their forties, 16 Jewish figures appear. In the next four decades, from 1870 to 1910, when all non-Russian Jews are living in societies that offer equal legal protection if not social equality, that number jumps to 40. During the next four decades until 1950 - including the years of the Third Reich and the Holocaust - the number of Jewish significant figures almost triples, to 114. The figure below shows how these numbers work out as percentages of all significant figures for the three half-centuries from 1850 to 1950:

As Murray elaborates elsewhere:

Disproportionate Jewish accomplishment in the arts and sciencesTo use Clemens, Montenegro, and Pritchett's terminology, Murray is essentially estimating the "place premium" for Jewish achievement. As long as Jews remained in literal ghettos, most of their creative abilities were invisible - and wasted. In order to live up to their full potential, the Jews had to physically and intellectually migrate. Some declined to do so even after they had the option. But the rest took to social integration like fish to water - and the results are staggering.

continues to this day. My inventories end with 1950, but many other

measures are available, of which the best known is the Nobel Prize. In

the first half of the 20th century, despite pervasive and continuing

social discrimination against Jews throughout the Western world, despite

the retraction of legal rights, and despite the Holocaust, Jews won 14

percent of Nobel Prizes in literature, chemistry, physics, and

medicine/physiology. In the second half of the 20th century, when Nobel

Prizes began to be awarded to people from all over the world, that

figure rose to 29 percent. So far, in the 21st century, it has been 32

percent. Jews constitute about two-tenths of one percent of the world's

population. You do the math.

(0 COMMENTS)

April 3, 2014

Water Runs Downhill, and School Is Boring, by Bryan Caplan

HSSSE asks two direct questions about boredom: "Have you ever been bored in class in high school?" and "If you have been bored in class, why?"These results barely change from year to year:

Two out of three respondents (66%) in 2009 are bored at least every day in class in high school; nearly half of the students (49%) are bored every day and approximately one out of every six students (17%) are bored in every class. Only 2% report never being bored, and 4% report being bored "once or twice."

Responses to the second question provide insight into the sources of students' frequent boredom; students could mark as many reasons for their boredom as were applicable. Of those students who claimed they were ever bored (98%), the material being taught was an issue: more than four out of five noted a reason for their boredom as "Material wasn't interesting" (81%) and about two out of five students claimed that the lack of relevance of the material (42%) caused their boredom. The level of difficulty of the work was a source of boredom for a number of students: about one third of the students (33%) were bored because the "Work wasn't challenging enough" while just over one-fourth of the respondents were bored because the "Work was too difficult" (26%). Instructional interaction played a role in students' boredom as well: more than one third of respondents (35%) were bored due to "No interaction with teacher."

Over four years of HSSSE survey administrations, student responses have been very consistent regarding boredom. In a pool of 275,925 students who responded to this question from 2006 to 2009, 65% reported being bored at least every day in class in high school; 49% are bored every day and 16% are bored every class. Only 2% reported never being bored.This is all very consistent with the Gates Foundation finding that boredom is the single most important reason why kids drop out of high school. And on reflection, the boredom is probably even worse than it looks. School is a sacred institution; you're not "supposed to" talk bad about it. As a result, many students probably succumb to Social Desirability Bias by downplaying their malcontent.

Students' reasons for their boredom are similarly consistent in the four-year aggregate as well. "Material wasn't interesting" was cited by 82% of respondents and "Material wasn't relevant to me" by 41% of respondents. Thirty-four percent of students said that a primary source of their boredom was "No interaction with teacher."

Doesn't fit your first-hand experience? Remember: If you're reading this blog, you're probably part of the small minority that actually enjoys academics. When you were bored in school, you were probably bored because the schoolwork was too easy. For most students, however, the problem is fundamental. Schoolwork bores them because they don't like the content.

(18 COMMENTS)

April 2, 2014

Is Welfare a Band-Aid for Nominal Wage Rigidity?, by Bryan Caplan

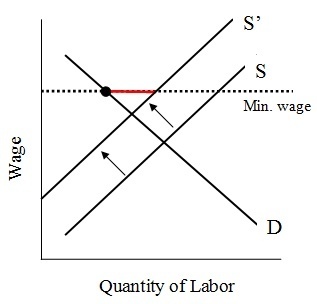

The minimum wage deprives the unfortunate workersDiagrammatically:

shown in red of their ability to support themselves. Given this

involuntary unemployment, the case for welfare is suddenly easier to

make. What happens if the government in its mercy puts the unemployed

on the dole?

The answer may surprise you. The supply of labor falls to S', of

course, because free money makes workers less eager to work. But unless

welfare is ample enough to push the market-clearing wage above the

legal minimum wage, welfare has no effect on the wage or quantity of hours worked! Why not? Because thanks to the minimum wage, jobs are rationed. There's still a line of eager applicants even if the marginal payoff for work declines.

With a binding minimum wage, the only clear-cut effect of welfare is to transform involuntary

unemployment into voluntary unemployment. That's why the red line

shrinks: Some - though not all - of the workers who craved a job at the

minimum wage now shrug, "Eh, now that I've got free money, why

interview?"

Figure 3: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage and Welfare

That's the simple analysis. Suppose, however, that if involuntary unemployment gets high enough, policy-makers cut the minimum wage. In this scenario, raising welfare makes the minimum wage less likely to fall. As a result, the social cost of welfare is higher than it looks on the surface. Yes, in the short-run, welfare merely "converts" involuntary unemployment to voluntary unemployment. In the long-run, though, welfare increases overall unemployment by making the collateral damage of the minimum wage more politically palatable.

The same principles applies if employers can gradually circumvent the minimum wage by requiring employees to work faster or harder. (Just picture labor demand rising because workers produce more per hour, and labor supply falling because workers suffer more per hour). The higher the rate of involuntary unemployment - the fraction of workers who want a job given current market conditions - the more appealing this circumvention becomes. When welfare converts involuntary unemployment to voluntary unemployment, it "sedates" the market's normal urge to undo the damage of the minimum wage.

Convinced? Now let's generalize to a much broader problem. Like most economists, I embrace standard New Keynesian models that blame mass unemployment on nominal wage rigidity. Workers' and managers' deep distaste for hourly pay cuts functions like an economy-wide morass of job-specific minimum wage laws. How does welfare interact with this nominal wage rigidity?

Once again, the short-run interaction is harmless. Workers who genuinely can't find a job because they've been priced out of the market receive some government money to help them make ends meet. Welfare converts desperate involuntary unemployment into merely unhappy voluntary unemployment.

In the long-run, though, welfare makes unemployment more likely to persist. When lots of unemployed workers are eager to work under current conditions, employers have the upper hand. This doesn't mean they can safely ignore workers' distaste for nominal wage cuts. But it does embolden employers to search for ways to cut compensation without incurring workers' wrath. When welfare makes unemployment more bearable, then, employers search less aggressively for ways to cut pay. As a result, full employment takes longer to return.

The upshot: Welfare is not a harmless band-aid for nominal wage rigidity. It's more like scratching a mosquito bite. In the short-run, welfare makes unemployed workers feel better. In the long-run, though, welfare makes workers more likely to stay unemployed. The reason isn't that welfare makes unemployment "fun." The reason, instead, is that welfare retards job creation by reinforcing nominal wage rigidity.

Economists have recently been debating the effect of denying unemployment checks to the long-term unemployed. Market-oriented economists tend to think that as soon as the checks stop coming, the unemployed get off their couches and find jobs. Old-style Keynesians tend to think the welfare cut-off will merely impoverish the unemployed - not get them back to work.

I say both sides are wrong. Holding wages constant, cutting unemployment benefits does nothing to make employers want to hire more people. But cutting unemployment benefits does corrode nominal rigidity, leading - by a slow and painful path - to higher employment. When the government cuts unemployment benefits, don't expect a sudden return to full employment. Instead, expect a gradual increase in job hunting, which in turn sluggishly drags wages back down to full-employment levels.

Many readers will conclude that the government should forget the long-run and keep sending unemployment checks. I beg to differ. Hazlitt was right: "Today is

already the tomorrow which the bad economist yesterday urged us to ignore." If unemployment benefits had not been extended to 99 weeks in 2009, the labor market could easily already be back to normal.

(2 COMMENTS)

April 1, 2014

Answering Arnold's Challenge, by Bryan Caplan

I still want to see an economist reconcile a belief in secularMy reconciliation:

stagnation with a belief in Piketty's claim that the return on capital

is going to exceed the growth rate of the economy on a secular basis.

Historically, the growth rate has usually been near-zero and interest rates have usually been high. Piketty's claim is simply that growth and interest rates will revert to their historic norm. Why is that so hard to believe?

Theoretically, interest rates are determined by many factors. Yes, expected economic growth is one such factor: When people expect to be richer in the future, they try to borrow against their future income. But this can easily be outweighed by time preference (see section VIII in my Week 2 micro notes). With stagnant income and slight time preference, interest rates will be positive even though economic growth is non-existent.

Either way, there's no puzzle.

Update: I interpreted Arnold's "secular stagnation" as a synonym for very low economic growth. But Arnold emailed me to say that he's using the phrase differently:

Original Summers explanation:

You could quote me as saying, "By secular stagnation, I

mean something more specific than just low economic growth. I interpret

Larry Summers as saying that real interest rates are permanently low, because

of a glut of savings relative to the demand for investment."

Secular stagnation refers to the idea that the normal, self-restorativeIn other words, I took "secular stagnation" as a claim about long-run growth, but Arnold was treating it as a claim about long-run demand. My apologies for any confusion, though other economists I know also interpreted "secular stagnation" as I did.

properties of the economy might not be sufficient to allow sustained

full employment along with financial stability without extraordinary

expansionary policies.

(3 COMMENTS)

March 31, 2014

You Don't Know the Best Way to Deal with Russia, by Bryan Caplan

The overconfident recommendation:

[T]he West should forcefully reassert NATO's willingness to defend itselfThe cursory recognition of countervailing considerations:

and make it clear that all members of the alliance share its complete

protection...

In particular, that means other NATO members sending at least a few

troops, missiles and aircraft to the Baltics (or to neighbouring

Poland), and making clear that bigger forces will follow if there is any

continued aggression from Mr Putin.

Why go that far? Plenty of people in the West would prefer to "wait andA litany of overconfident predictions:

see". The Balts have the promise of protection, they point out, so there

is only danger in provoking Mr Putin. Wishful thinkers say that having

made his point in Crimea, he will probably stop while he is still ahead.

Instead of ratcheting up tension, the West should provide "off-ramps"

that steer Russia towards détente. Other hard-nosed foreign-policy

"realists" argue that Russia has legitimate interests in its

near-abroad. It is madness, they say, to pick a fight when Russia and

the West have other business to be getting on with--Syria's civil war,

Iran's nuclear programme and China's growing power.

Notice: The Economist presents no empirics about past experiences with "standing up" versus "backing down." If it bothered to do so, it would find many supportive examples - plus many unsupportive counterexamples. World War II is the poster child for "standing up." World War I is the poster child for "backing down." The Korean War - standing up. The Vietnam War - backing down. Anyone who knows basic history can multiply such examples endlessly. International relations is inherently complicated. In hindsight, it's easy to explain how Serbian terrorism in 1914 led to North Korean Communist dictatorship in 2014. But who in 1913 even hinted at this possibility?In fact the opposite is true. The greatest provocation to Mr Putin is

to fail to stand up to him, and the least costly time to resist him is

now. Emboldened, Mr Putin could test NATO's resolve by changing the

facts on the ground (grabbing a slice of Russian-speaking Latvia, say,

or creating a corridor through Lithuania to Kaliningrad) and daring the

alliance to risk nuclear war. More likely he would try

destabilisation--the sabotage of Baltic railways; the killing of Russians

by agents provocateurs; strikes, protests and

anonymous economy-wide cyber-attacks. That would make life intolerable

for the Balts, without necessarily eliciting a response from the West.Either way, if the Balts begin to disintegrate, it would leave the

West with a much less palatable choice than it has today: NATO would

have to walk away from its main premise, that aggression against one is

aggression on all, or it would have to respond--and to restore

deterrence, NATO's response would have to be commensurately greater.

That in turn would pose the immediate threat of escalation.

Better to take steps today, so that Mr Putin understands he has nothing to gain from stirring up trouble.

This doesn't mean, of course, that empirical study of foreign policy is fruitless. Maybe an exhaustive study would reveal that standing up works better 55% of the time, and backing down works better 45% of the time. But unless you hide behind lame tautologies ("I favor smart standing up. That never fails!"), you're unlikely to reach a stronger conclusion.

You could object, "You can't galvanize resistance by saying there's a 55% chance you're right." Fair enough. But if that's all you can honestly claim, why are you so eager to galvanize resistance in the first place? Why are you so hasty to claim opposing experts haven't a clue? Maybe you should spend a few years publicly betting your opponents. There's no better way to prove to the world - and yourself - that your forecasts are genuinely better than chance.

Look in the mirror. You don't know the best way to deal with Russia. "Taking steps today" could work precisely as The Economist

hopes. It could lead Putin to double down. Crossing your fingers and

waiting for things to blow over might be a disaster. Then again, it

might work. Stranger things have happened. If you scoff, I'm happy to bet. But since you're claiming knowledge and I'm pleading ignorance, I want odds.

P.S. Not April Fools.

(0 COMMENTS)

March 30, 2014

The Market for Less, by Bryan Caplan

The market is often better at abetting good habits than it is atAt first glance, this is a powerful asymmetry. Indeed, in slogan form you might say, "There is no such thing as a 'market for less.'" But can this slogan really withstand critical scrutiny?

discouraging bad habits. Imagine an alternate world in which a lot of

people aspired to smoke more cigarettes but they had trouble sticking to

their preferred regimen. In this alternate world, the market might

offer yearly memberships that shipped people a carton of cigarettes

every week. Or, pharmacies might sell a membership pass, where you get a

free or discounted pack of cigarettes every day. These arrangements

would incur a fixed cost, but they would lower the incremental cost of

smoking additional cigarettes -- thus helping you to achieve your goal

of smoking more. However, it would be harder for the market to inflate

the future cost of cigarettes in the more likely event that you needed

help reducing your smoking. Imagine explaining to the local Quickie

Mart that higher cigarette prices would further your health goals. What

would happen if Quickie Mart obliged your strange request and promised

to inflate the price of cigarettes that they sold specifically to you?

When cravings struck, you would just buy your cigarettes at a different

store.

If you've had intermediate microeconomics, the simplest response is to say, "Raising the price of x relative to y is equivalent to lowering the price of y relative to x." So if you want to make tobacco more expensive relative to non-tobacco, you don't have to directly raise the price of tobacco. You could instead cut the price of everything else. Using James' "yearly membership" approach, a store like CostCo could (a) charge a high membership fee, (b) have cheap prices for everything except tobacco, and (c) have regular prices for tobacco - or simply not carry the vile weed.

If you learned your intermediate microeconomics well, however, you might fret about the income effect. The cheap prices for all non-tobacco products effectively enrich you. As a result, you might take your savings and spend it on tobacco, thwarting your personal self-control project. (For a single item, in contrast, this income effect would probably be trivially small).

Is there a substitute that avoids such income effects? Sure. Remember stickK.com? The logic is simple: Precommit to forfeit some money if you buy too much of the wrong thing. Want to smoke less? Fine. Commit to pay $100 for every pack of cigarettes you smoke - no matter where you buy it. Won't you try to wriggle free? Maybe. But you could also precommit to buy everything with credit cards and send your monitor copies of all your receipts.

The cleaner approach, though, is to base penalties on a periodic objective test. For fatty foods, you could base penalties on the difference between your actual and desired weight. For tobacco, you could base penalties on nicotine or Cotinine levels.

Most people will naturally whine that such tests are "inconvenient" or "intrusive." Yet this whining helps us ballpark the seriousness of the problem. If you aren't willing to do a weekly cheek swab to keep yourself on the straight and narrow, how much do you really care about your problem?

The honest answer for the average person, as far as I can tell, is "not much." StickK.com remains a niche service. The website brags that it has "$17,143,845 on the line" and takes credit for "2,502,250 cigarettes not smoked." By start-up standards, that's impressive success. By national or global standards, though, that's abject failure.

In the end, I come to the same conclusion as James: There's isn't much demand for self-control.

The market offers a lot of programs that could easily be tweaked to beHow can lack of demand be reconciled with all the excuses about lack of self-control? I once again point to the psychological literature on Social Desirability Bias.

commitment devices. The fact that the market doesn't offer these

commitment devices indicates that they probably aren't desired.

Part of the reason why people who spend a lot of time and money on

socially disapproved behaviors say they "want to change" is that that's

what they're supposed to say.Think of it this way: A guy loses his wife and kids because he's a

drunk. Suppose he sincerely prefers alcohol to his wife and kids. He

still probably won't admit it, because people

judge a sinner even more harshly if he is unrepentent. The drunk who

says "I was such a fool!" gets some pity; the drunk who says "I like

Jack Daniels better than my wife and kids" gets horrified looks. And

either way, he can keep drinking.

Cynical? Certainly. But when narrow-minded economic theory and broad-minded empirical psychology point in the same cynical direction, the cynics are probably on to something.

(7 COMMENTS)March 28, 2014

A British Perspective on American Signaling, by Bryan Caplan

In my second year as an assistant professor at Stanford

University, I was assigned the task of mentoring six freshmen. Each appeared on paper to have an incredible

range of interests for an eighteen-year-old: chess club, debate club, history

club, running team, volunteering with homeless shelters. I soon discovered that these supposed

interests were just an artifact of the U.S. college admission process, adopted

to flesh out the application forms and discarded as soon as they have worked

their magic.

(20 COMMENTS)

March 26, 2014

The Swamping that Wasn't: The Diaspora Dynamics of the Puerto Rican Open Borders Experiment, by Bryan Caplan

The third big thing we know [about immigration] is that the costs ofI recently stumbled on an excellent example. Puerto Rico came under U.S. rule in 1898. Six years later, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld Puerto Ricans' right to freely enter the United States (Gonzales v. Williams [1904]) Consider it open borders by judicial fiat.

migration are greatly eased by the presence in the host country of a

diaspora from the country of origin. The costs of migration fall as the

size of the network of immigrants who are already settled increases.

So the rate of migration is determined by the width of the [income] gap,

the level of income in countries of origin, and the size of the

diaspora. The relationship is not additive but multiplicative: a wide

gap but a small diaspora, and a small gap with with a large diaspora,

will both only generate a trickle of migration. Big flows depend upon a

wide gap interacting with a large diaspora and an adequate level of

income in countries of origin.

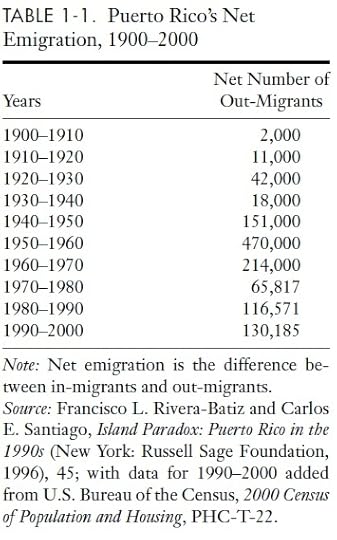

Did Puerto Ricans "swamp" in? Hardly. Instead, the Supreme Court's decision sparked a century-long chain reaction. Here's the data, courtesy of historian Carmen Whalen.

Notice: When there were only a few thousand Puerto Ricans in the entire country, open borders led to only modest migration. But decade-by-decade (with an understandable hiatus during the Great Depression), Puerto Rican migration snowballed. In the end, you get what you'd expect from open borders: More Puerto Ricans live in America than Puerto Rico. Yet this great transformation took decades.

Not convinced? You see similar diaspora dynamics if you break Puerto Rican immigration down by state:

Look. In 1950, there were only 4,040 Puerto Ricans in Florida - versus a quarter million in New York. Florida was far more like Puerto Rico in every way - except for the lack of Puerto Ricans. The result: The vast majority of Puerto Rican immigrants in 1950 chose to freeze in New York with their own kind than bask with the Anglos in the Florida sun. Florida eventually became Puerto Ricans' second-favorite state of residence - but only after the Puerto Rican population hit critical mass.

Since the historic 1904 Supreme Court decision, transportation costs have drastically fallen and wage gaps between the First and Third Worlds have grown. I'd expect open borders to work their magic more swiftly today than they did a century ago. But the basic point remains sound. Open borders wouldn't lead to instant "swamping." Instead, we'd see the Puerto Rican experience writ large.

(2 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers