Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 153

March 3, 2014

The Happiness of the Richest, by Bryan Caplan

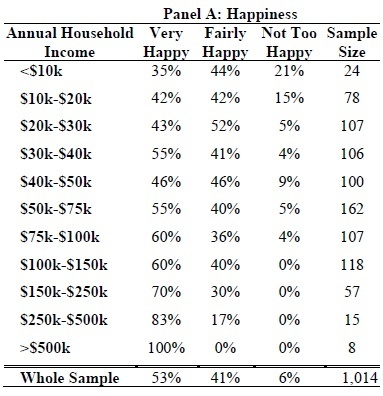

Yep, 100% of the respondents with family income over half a million a year were indeed very happy. Of course, there were only 8 such respondents. And in the same survey, happiness was virtually flat from $30k to $150k - roughly the 20th through 90th percentiles. Extreme Epiricureanism is both demonstrably false and approximately true.

P.S. David's thoughts about the ideological compatibility of happiness research and free-market economics make me realize I should have been clearer. Two points:

1. David is correct to observe that diminishing marginal utility of income/wealth is entirely compatible with a suitably internationalist free-market economics. If a dollar means more to a poor man than a rich man, using government to help relatively poor First Worlders at the expense of absolutely poor Third Worlders is morally perverse.

2. Still, the small effect of income/wealth on happiness throughout the income distribution remains ideologically inconvenient for free-market economists. A free-market economy is a fantastic tool for making people rich, but making people rich is a mediocre tool for making people happy.

(19 COMMENTS)

March 1, 2014

Ukrainian Prediction Challenge, by Bryan Caplan

The long-run benefits of war are highly uncertain. Some wars -Challenge: In the comments, go on the record and predict what will actually come of the emerging Ukrainian-Russian conflict. Only unconditional, falsifiable predictions count. No claims like: "Unless the EU acts..." "If Russia comes to its senses..." or "This will be a very different world." Make specific claims about what will actually happen by a specific date.

most obviously the Napoleonic Wars and World War II - at least arguably

deserve credit for decades of subsequent peace. But many other wars -

like the French Revolution and World War I - just sowed the seeds for

new and greater horrors. You could say, "Fine, let's only fight wars

with big long-run benefits." In practice, however, it's very difficult

to predict a war's long-run consequences. One of the great lessons of Tetlock's Expert Political Judgment is that foreign policy experts are much more certain of their predictions than they have any right to be.

In a year I'll revisit your comments and rank their accuracy with the benefit of hindsight.

(31 COMMENTS)

What Say You? The Intuitive Case Against the Minimum Wage, by Bryan Caplan

Question #1:

Name some other goods or services for which a government-mandated

price hike of 25 percent will not cause fewer units of those goods and

services to be purchased.

Beer? Broccoli? Bulldozers? Coffee? Haircuts? Natural gas?

Automobiles? Housing? Preventive health-care? Lawn-care service?

Tickets to the movies? Smart phones? Subscriptions to the New York Times?

Books by Paul Krugman? Professors of sociology? Assistant professors

of economics? Any of these products work for you? If none of these

work, surely you can name at least one other for which a

25-percent price hike will not cause fewer units of that product to be

purchased. Or does low-skilled labor just happen to be the one good or

service in the entire world for which a government-mandated 25-percent

rise in the price that its buyers must pay for it will not diminish

buyers' willingness to buy it?

Seriously, name just one other good or service for which you believe

that a government-mandated price-hike of 25 percent will not reduce the

quantity demanded of that good or service.

Question 2:

[B]ecause if Mr. Obama's full proposal is enacted the national minimum

wage will also from here on in be indexed to inflation, here's another

challenge to anyone who dismisses as unscientific or ideological the

standard economic argument against the minimum wage: name one other good

or service whose real price, according to economic theory, should never

fall relative to the prices of other goods or services?

The least-bad answers to Boudreaux's Question #1 that occur to me probably salt and soap. As Oskar Lange asked in 1937: "[W]ould a decline of the price of soap to zero induce them [the "well-to-do"] to be so much more liberal in its use?" By the standard of 1937, almost everyone in the First World is well-to-do today. For Question #2, I'm utterly stumped.

(22 COMMENTS)February 27, 2014

Wolfers Responds on Happiness, by Bryan Caplan

Interesting, fun, provocative, and well written. Your

math looks to be right to me.

Some thoughts:

1. I'm not sure that controlling for confounds necessarily

would reduce the causal effect of income. (My prior is similar to yours,

but I haven't thought through the issue enough).

2. I actually think 0.35 is pretty big. Said another

way, it's big enough that it can explain why people in Burundi are at 3.5/10 on

a happiness scale, and Americans are at 8/10. My interpretation is that

big gaps in happiness are easily explained by big gaps in income. So why

do we interpret things differently?

a. I think raising happiness by a standard deviation is

huge. Basically I see incredibly miserable people and incredibly happy

people all around me. Moreover, if you think there's measurement error in

happiness, then the standard deviation in measured happiness is even bigger

(and you are talking about raising someone's measured happiness by one measured

standard deviation).

b. The other way of saying this is that it doesn't matter

that the effect of income on happiness is "small": if there exist

massive disparatives in income, then a small coefficient can have a big effect.

And I think there exist massive disparaties in income (and these largely

explain the massive disparaties in happiness).

3. In my careful moments, I see my data as a shocking

refutation of whether money has no effect on happiness. In my

less-guarded moments, I see it as a refutation of whether money has little effect

on happiness.

4. Your final thought experiment ("an extra

$820,585" is clever). But it is just as interesting of a thought

experiment in the opposite direction: If I raised your income from $3,000

(roughly the average income in the US at the turn of the century) to $50k, I

would increase your happiness by one standard deviation. How many people

would move from being "depressed" to OK? (If, for argument's sake,

depressed = bottom 5% in 1900, then depressed = % of people with z-score less

than 1.6. Shift that distribution 1 standard deviation to the right, and

the proportion who are depressed = % of people with z-score 1 less than 1.6,

which is 0.5%. So we would nearly eliminate depression.)

But, as always, really interesting stuff, and great fodder

for the blog.

One more thought: The claim made by some that money matters

less than we think and hence we should focus less on it, always struck me as

important, and plausible, and one that my evidence is silent on.

J.

(6 COMMENTS)

February 26, 2014

Crude Materialism versus the Wolfers Equation , by Bryan Caplan

is the secret to happiness. You're estimating an equation of the form:

Happiness (in Standard Deviations) = a + b * ln(income)

How big should you expect b to be? Well, you'd probably think that

increasing income by 100% would increase happiness by at least a full

standard deviation. Since ln(2)=.69, doubling income corresponds to a .69

log-dollar increase. So you should expect to see something like:

Happiness (in Standard Deviations) = a + 1.44 * ln(income)

At the other extreme, suppose you're a hard-line

Epicurean who believes that human beings instantly acclimate to their

financial circumstances. Then you'd expect to find something like:

Happiness (in Standard Deviations) = a + 0 * ln(income)

Last week Justin Wolfers came to GMU to present the best available individual,

cross-national, and over-time evidence on income

and happiness. After exploring a wide range of data sets, he

gleefully presented the answer:

Happiness (in Standard Deviations) = a + .35 * ln(income)

As usual, Wolfers' work was both careful and thorough. But what does it

mean? Most people interpret Wolfers' findings as a shocking refutation of

everyone who thinks that money has little effect on happiness. Wolfers

largely embraced this take. But should he?

I think not. If you picture a continuum with Epicureanism at 0, and crude

materialism at 1, Wolfers stands at .24. According to his results, the

effect of income on happiness, though positive, is small.

Not convinced? Consider: Wolfers' result implies that to raise happiness

by one standard deviation, you have to raise income by 1/.35=2.86 log

points. How much is that exactly? In percentage terms, that's

(e^2.86)-1 - an increase of 1,640%. So if you currently earn

$50,000, Wolfers' coefficient implies you'd need an extra $820,585 per year

to durably increase your happiness by one lousy standard deviation. In

math, that's not "zero effect of income on happiness." But in

English, it basically is.

Still not convinced? Remember that Wolfers deliberately refrains from

controlling for confounding variables, so the true effect of income on

happiness is almost certainly even smaller than it looks.

The view that money has a major effect on happiness is ideologically convenient

for me. But it goes against first-hand experience, the wisdom of the

ages, and the rightly interpreted empirical evidence. So to hell with

ideological convenience.

February 25, 2014

The Singaporean Path to Cosmopolitanism, by Bryan Caplan

Only 4% of Singaporeans favour open borders, and just 24% are willing toFortunately, Singaporean elites are very pro-immigration, and the Singaporean electorate treats their elites with great deference. Hence the Singaporean government's official long-run plan:

admit immigrants "as long as jobs [are] available"; the comparable

numbers in the United States are 12.4% and 44.8%...

Foreigners now make up about 38 percent of the total population of 5.3 million. In 1990, that figure was 14 percent, when the total population was around 3 million.Contrary to popular mythology, Singapore is a democracy. It's conceivable that populist pressures will reverse Singapore's cosmopolitan course, as in Switzerland. But I'll bet against it. As immigration keeps rising, so will the social pressure against nativist complaining. Deprived of social support, nativist sentiment will atrophy as well. By the time Singaporean natives become a minority in their own country, nativist hold-outs won't lament "the country they lost." They'll be too busy pretending they were never nativists in the first place.

Last year, a government policy paper called for the population to

increase a further 30 percent by 2030, to 6.9 million, at which time

immigrants would account for nearly half of the island's population.

(11 COMMENTS)

How Welfare Hurts Walmart, by Bryan Caplan

As long as non-workers remain eligible for poverty programs, the answer is no. This is basic supply-and-demand. When the government offers free stuff to people with low incomes, the marginal benefit of work falls - and so does labor supply. When labor supply falls, hours of work go down, and wages rise. This could be very nice from the point of view of Walmart's workers. From the point of view of Walmart's stockholders however, it's bad.

Not convinced? Ask yourself: "If I ran Walmart, would I favor higher unemployment benefits?" Of course not. Why not? Because higher unemployment benefits make it easier to not apply for a job at Walmart. The same goes for any government program that makes idleness less unpalatable.

Once you grasp why standard welfare programs hurt Walmart, you are ready to search for counter-examples. Is there any government program that actually increases labor supply? Indeed there is: the Earned Income Tax Credit. To benefit from this program, you have to work. The more you work, the larger your tax credit. When the EITC goes up, the marginal benefit of work rises - and so does labor supply. This doesn't mean that Walmart is the sole beneficiary of the EITC; unless labor demand is perfectly inelastic, workers capture some of the program's benefits too. But from Walmart's point of view, a bigger EITC is better.

HT: Perry Metzger

(25 COMMENTS)

February 23, 2014

The Minimum Wage vs. Welfare: Band-Aid or Salt?, by Bryan Caplan

"In theory, I'm against it, because people should have the freedom toIs he right? Maybe. A key insight of welfare economics is that one inefficient policy can counter-act another inefficient policy. But does this insight apply in this particular case? Let's work through matters step by step.

contract at whatever wage they'd like to have. But in practice, I think

the alternative to higher minimum wage is that people simply end up

going on welfare.''

"And so, given how low the minimum wage is -- and how generous the

welfare benefits are -- you have a marginal tax rate that's on the order

of 100 percent, and people are actually trapped in this sort of welfare

state."

"So I actually think that it's a very out of the box idea -- but it's

something one should consider seriously, given all the other distorted

incentives that exist."

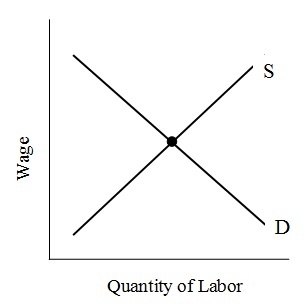

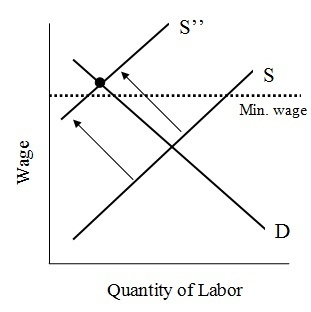

First, imagine laissez-faire. There's no welfare and no minimum wage. The low-skilled labor market looks just like this:

Figure 1: Low-Skilled Labor Market Under Laissez-Faire

There's no involuntary unemployment, and the big black dot reveals the wage and quantity of labor.

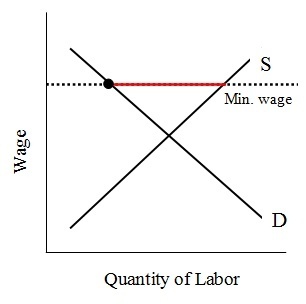

Now imagine adding a minimum wage - but no welfare - to the mix.

Figure 2: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage But No Welfare

The big black dot still reveals the wage and quantity of labor. Thanks to the minimum wage, though, there's now a lot of involuntary unemployment, marked in red. This is true despite the fact that the minimum wage increases the incentive to work. Why? Because the minimum wage also reduces the incentive to hire! Since a deal only happens if both demanders and suppliers of labor consent, the quantity of hours worked is the smaller of quantity demanded and quantity supplied.

Under laissez-faire, any able-bodied worker can get a job and stand on

his own two feet. The minimum wage deprives the unfortunate workers

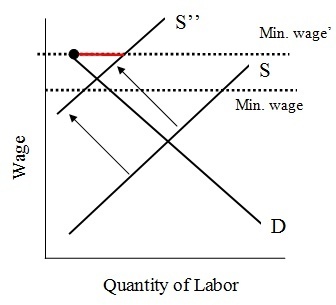

shown in red of their ability to support themselves. Given this involuntary unemployment, the case for welfare is suddenly easier to make. What happens if the government in its mercy puts the unemployed on the dole?

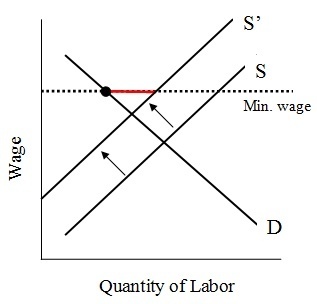

Figure 3: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage and Welfare

The answer may surprise you. The supply of labor falls to S', of course, because free money makes workers less eager to work. But unless welfare is ample enough to push the market-clearing wage above the legal minimum wage, welfare has no effect on the wage or quantity of hours worked! Why not? Because thanks to the minimum wage, jobs are rationed. There's still a line of eager applicants even if the marginal payoff for work declines.

The answer may surprise you. The supply of labor falls to S', of course, because free money makes workers less eager to work. But unless welfare is ample enough to push the market-clearing wage above the legal minimum wage, welfare has no effect on the wage or quantity of hours worked! Why not? Because thanks to the minimum wage, jobs are rationed. There's still a line of eager applicants even if the marginal payoff for work declines. With a binding minimum wage, the only clear-cut effect of welfare is to transform involuntary unemployment into voluntary unemployment. That's why the red line shrinks: Some - though not all - of the workers who craved a job at the minimum wage now shrug, "Eh, now that I've got free money, why interview?"

On Thiel's story, though, Figure 3 doesn't fit the contemporary labor market. He claims that welfare is now so generous that workers no longer desire minimum wage jobs. Diagrammatically:

Figure 4: Low-Skilled Labor Market With Minimum Wage and High Welfare

Notice: Sufficiently high welfare makes the minimum wage irrelevant. The market now clears at the intersection of the old demand curve D and the new supply curve S''. Since the intersection exceeds the minimum, the minimum has no effect. Thanks to welfare, employment is low. But whatever unemployment you see is voluntary.

OK, now we're ready to see if Thiel's story makes sense. Figure 4 roughly describes the world he thinks we're in. What would happen if, swayed by Thiel's argument, government raises the minimum wage to counteract welfare's disincentive effects?

Figure 5: Low-Skilled Labor Market With High Minimum Wage and High Welfare

The answer, as Figure 5 clearly shows, is utterly orthodox: wages rise, employment falls, and involuntary unemployment revives. How is this possible? Simple. Generous welfare benefits do nothing to vitiate the truism that the minimum wage simultaneously raises the incentive to work and cuts the incentive to hire. And as usual, a deal only happens if both demanders and suppliers consent. The market therefore goes to the intersection of quantity demanded and the new minimum wage, with unemployment shown in red.

The lesson: When the minimum wage causes involuntary unemployment, raising welfare can serve as a band-aid for the labor market. Workers deprived of the right to provide for themselves can subsist on government money. Yet when welfare convinces people to abandon honest toil, raising the minimum wage is no band-aid. Instead, raising the minimum wage salts the wounds. The reason, to repeat: While a higher minimum wage does indeed make workers more eager to work, it also automatically makes employers less eager to hire.

I have great respect for Peter Thiel, but his concession to minimum wage advocates is confused. While some inefficient policies can offset the effects of other inefficient policies, the minimum wage is not such a policy. It doesn't matter if welfare is high, low, or non-existent. The minimum wage causes unemployment by making marginal workers unprofitable to employ.

(8 COMMENTS)

February 20, 2014

Ambition Revisited, by Bryan Caplan

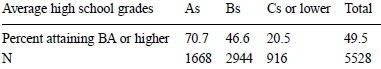

Exhibit A: Percentage of high school seniors who plan to get a BA who successfully do so.

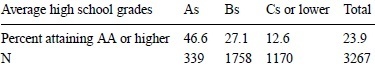

Exhibit B: Percentage of high school seniors who plan to get an AA who successfully do so.

The simplest reading of the evidence is that getting a BA is easier than getting an AA! After all, holding high school GPA constant, students are vastly more likely to complete the BA. Over two-thirds of A-students who plan to get a BA succeed; less than half of A-students who plan to get an AA succeed. This pattern extends all the way down to the weakest students.

A better interpretation, though, is that seniors who say they want a BA have a lot more ambition than their peers. As a result, they are - holding grades fixed - markedly more likely to achieve their goal despite its intrinsic difficulty. Seniors who say they only want an AA, in contrast, simultaneously aim low and fall short.

This probably doesn't mean that students can improve their prospects merely by mouthing the words, "I plan to get a BA." The reasonable interpretation, rather, is that people who place a high value on conventional success are much more likely to achieve it. A B student who says, "I want a BA" is as likely to cross his personal finish line as an A student who says, "I want an AA." And as far as I know, no estimate of the return to education properly adjusts for this factor.

(0 COMMENTS)

February 19, 2014

Desert versus Identity, by Bryan Caplan

[T]he son will not be made responsible for the evil-doing of the father,You can't judge a person for the actions of his father, sisters, neighbors, or people who share his hair color. Instead, you must judge him for what he has personally done. What moral truth could be more self-evident?

or the father for the evil-doing of the son; the righteousness of the

upright will be on himself, and the evil-doing of the evil-doer on

himself.

-Ezekiel 18:20

Yet in practice, human beings' adherence to this moral truth remains iffy. The main reason is clear: group identity. When people judge members of their own groups, they accept an endless list of lame excuses. When people judge members of other groups, they accept an endless list of ludicrous condemnations.

War crimes are a stark example. Suppose a soldier from group X plainly murdered ten innocent civilians from group Y. What do the people of X say? "It was war." "He just lost his buddy a month earlier." "If you've never been in that situation, you can't judge." "He was just following orders." "His officer should have seen it coming."

This absurd leniency reverses, of course, when members of group X judge some enemy Y's during wartime. Although the individual Y's plainly never hurt a fly, they deserve to die! "They started the

war; we're just finishing it." "They leave us no choice." "They would have done far worse to us." "What about the innocent X's the Y's killed?" Never mind if the specific Y's on the chopping block are powerless peons, hapless conscripts, or defenseless children. They brought their deaths on themselves by belonging to a team they are metaphysically unable to quit.

We see the same farce when people decide whether someone deserves his poverty. If the pauper belongs to group X, members of group X loathe to blame him. The pauper is routinely drunk? Well, that's an understandable response to an unjust society, bad upbringing, or despair. The pauper spends half his money on cable? Well, in our society cable's a necessity. He got fired because he could barely read or add? Our public schools failed him - even if his teachers reliably showed up and did their jobs - and the student was smoking in the boys' room.

If the pauper belongs to an out-group, in contrast, members of group X will fault him for the most absurd reasons. The best job he can get pays $1 a day? He should have gotten himself a better education. The government's teachers rarely even show up to class? That's what you get when you elect a government with crummy economic policies. His government is a dictatorship? That's what happens when you forget that vigilance is liberty's eternal price. What about the obvious fact that all of these problems - unlike alcohol and cable consumption - are largely or entirely outside the control of one impoverished individual? Blank-out.

Human beings evolved in small bands. Group identity - and group identity's tendency to corrupt our sense of justice - is in our DNA. Once you learn this harsh truth, though, you can, should, and must compensate for your immoral urges. Review your judgments of out-group members for draconian harshness. Review your judgments of in-group members - yourself included - for maudlin absolution. You won't make a lot of friends, but you will be a better person.

* Noah's family excepted, of course.

(6 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers