Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 157

January 14, 2014

The Discipline of Dismissal, by Bryan Caplan

Tyler has some dismissive observations about the practice of dismissal:

One of the most common fallacies in the economics blogosphere -- and elsewhere -- is what I call "devalue and dismiss." That is, a writer will come up with some critique of another argument, let us call that argument X, and then dismiss that argument altogether. Afterwards, the thought processes of the dismisser run unencumbered by any consideration of X, which after all is what dismissal means. Sometimes "X" will be a person or a source rather than an argument, of course.

The "devalue" part of this chain may well be justified. But it should lead to "devalue and downgrade," rather than "devalue and dismiss."

I'm tempted to object, "Thank goodness for dismissal, because most ideas and thinkers are a waste of time." But on reflection, Tyler's overly optimistic. Dismissing ideas often requires rare intellectual discipline. Psychologists have documented our assent bias: Human beings tend to believe whatever we hear unless we make an affirmative effort to question it. As a result, our heads naturally accumulate intellectual junk. The obvious remedy is to try harder to "take out the trash" - or refuse to accept marginal ideas in the first place.

The deeper problem: People are bad at Transfer of Learning, so dismissing an idea in general terms does not prevent it from swaying your judgment in individual cases. Few adults deny the power of supply and demand in general terms. But when they think about labor markets, many remain crude Marxists: "Working conditions are terrible! Let's pass a law!" The problem continues throughout the knowledge pyramid: A person can recognize that supply and demand govern the labor market, but remain a crude Marxist when he talks about labor in the 19th-century or Third World.

The upshot is that full-fledged dismissal requires puritanical intellectual discipline. This discipline is not always a virtue. If your principles are poisonous, inconsistency dilutes the damage. But right or wrong, whole-hearted ("whole-minded"?) dismissal is, contra Tyler, in short supply.

(10 COMMENTS)

January 11, 2014

Sitting on an Ocean of Hypotheticals, by Bryan Caplan

David senses a weakness in my "Sitting on an Ocean of Talent":

But I don't think people's opposition to more immigration is that different from how they would react to those who would prevent them from getting at precious resources. Exhibit A is oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Region (ANWR.) For years, the federal government has locked up that resource, not allowing it to be drilled. Assuming that it is locked up forever, the foregone gains are about 30% of Bryan's hypothetical trillion dollars.

[...]

But the point is: that's not what people are doing. People are treating that locked-up pool of oil much the same way they're treating that locked-out ocean of talent. They're passively accepting the government's limits and, in both cases, many people favor them.

My reply: I deliberately didn't use oil as an example because many smart people think there is a powerful reason to leave untapped oil reserves untouched: negative externalities, especially from air pollution and climate change. I focused on a purely hypothetical substance - Leonium - to fix ideas and bypass pre-existing ideological commitments. Otherwise I'd be basing one controversial position (pro-immigration) on an unrelated controversial position (pro-drilling) - rarely a good pedogogical or rhetorical idea.

January 8, 2014

How Rival Is Your Marriage?, by Bryan Caplan

If all their goods are rival (like food), the answer is "Their standard of living stays the same." $50,000 times two divided by two equals $50,000.

If all their goods are non-rival (like Internet access), the answer is "Their standard of living doubles." They pool their money and buy a $100,000 lifestyle for both of them.

In the real world, of course, couples are rarely at either pole Most goods are in fact semi-rival. Consider housing. If you share your home with a spouse, you don't have as much space for yourself as a solitary occupant of the same property. But both of you probably enjoy the benefits of more than half a house. If a couple owns one car, similarly, both have more than half a car. Even food is semi-rival, as the classic "You gonna eat that?" question proves.

Mathematically, married individuals' utility looks something like this:

U=Family Income/2a

a=1 corresponds to pure rivalry: Partners pool their income, buy stuff, then separately consume their half. a=0 corresponds to pure non-rivalry: Partners pool their income, buy stuff, then jointly consume the whole.

There's little doubt that aeven built into the official poverty line. That's why I say that being single is a luxury. My question: Where does a typically lie in the real world? Feel free to discuss variation by social class and nationality. Please show your work.

P.S. If you know of academic references on this exact question, please share.

(20 COMMENTS)

January 7, 2014

What's Wrong With IVs? [wonkish], by Bryan Caplan

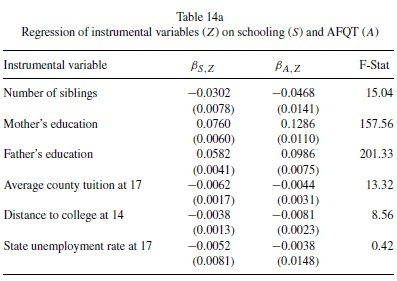

[M]ost of the candidates for instrumental variables in the literature are also correlated with cognitive ability. Therefore, in data sets where cognitive ability is not available most of these variables are not valid instruments since they violate the crucial IV assumption of independence. Since few data sets have measures of cognitive ability, this finding calls into question much of the IV literature. Notice that the local unemployment rate is not strongly correlated with AFQT. However, it is only weakly correlated with college attendance.Check it out:

(2 COMMENTS)

January 6, 2014

Sitting on an Ocean of Talent, by Bryan Caplan

How would Americans react when they learn they're sitting on an ocean of Leonium?

First, elation. A trillion dollars of precious Leonium has fallen like manna from heaven - or, to be more precise, risen like manna from the underworld.

Second, frustration. At first blush, the only way to get this Leonium is to demolish the Empire State Building, a structure of great economic and cultural value. The Leonium won't come easy.

Third, ingenuity. Great minds around the world start brainstorming, desperately trying to figure out a way to gain the Leonium without losing the Empire State Building. People propose hundreds of ideas - even individuals in no position to personally profit if their ideas prevail.

Fourth, tenacity. Great minds don't despair if the first hundred Leonium extraction proposals are clearly flawed. Instead, they keep hunting for alternatives - and sifting through old proposals in search of a glimmer of hope. Most individual innovators eventually give up, but there's always a new wave of creativity, drawn to the problem by dreams of eternal glory and endless riches.

During this brainstorming process, a few naysayers fret about the distributional consequences of success: "Only the

rich will benefit." "Only the owners of the Empire State Building will profit." "Unprecedented longevity will undermine government retirement

programs." "Nursing homes will lose jobs." But most people scoff

at such parochial and misanthropic negativity. Getting Leonium is a great benefit for mankind, period.

Now consider: Economists already know how to extract many trillions of dollars of additional value from the global economy. How? Open borders. Under the status quo, most of the world's workers are stuck in unproductive backwaters. Under free migration, labor would relocate to more productive regions, massively increasing total production. Standard cost-benefit analysis predicts that global GDP would roughly double. In a deep sense, we are sitting on an ocean of talent - most of which tragically goes to waste year after year.

When people accept this analysis, though, they rarely display elation, frustration, ingenuity, or tenacity. The standard reaction, instead, is naysaying. "First World workers will lose." "Only the rich will gain." "They'll all go on welfare." "Our culture will be destroyed." "The immigrants will increase crime." The underlying attitude is not frustration at the difficulty of realizing mankind's full potential, but sheer apathy. People look for reasons not to open borders - no matter how enormous its potential social benefits.

My point: Apathy in the face of unrealized multi-trillion dollar gains is absurd. People wouldn't be apathetic if a trillion dollars worth of Leonium were under the Empire State Building. Instead, people would be constructive - earnestly searching for ways to surmount every impediment to success - natural or social, real or imagined.

I can understand concerns about immigration. I can understand complaints about immigrants. What I can't understand is indifference to the mind-boggling potential benefits of immigration. The knowledge that we're sitting on an ocean of talent should haunt great minds day and night. They should pace around their offices telling themselves, "There's got to be a way to unlock these wasted trillions of dollars of human potential. There's just got to be a way." They should publicly propose and debate solutions, always on the look-out for any idea that "just might work." Keyhole solutions should be on the lips of every intellectually engaged human being.

A massive pool of humanity trapped in the Third World is no less urgent or engaging than a massive pool of Leonium under the Empire State Building. So why are people's reactions to the two scenarios so different? I say anti-foreign bias clouds our judgment. Psychologically normal humans underestimate the benefits of dealing with foreigners. On a gut level, they see foreigners as a threat. So their response to the promise of open borders is "Why bother?" - even though the common sense reaction is "Oh my God - we're sitting on an ocean of talent!"

(23 COMMENTS)

January 5, 2014

Self-Help: The Obvious Remedy for Academic Malemployment, by Bryan Caplan

A substantial fraction -- maybe the majority -- of PhD programs really shouldn't exist.

But

of course, this is saying that universities, and tenured professors,

should do something that is radically against their own self-interest.

That constant flow of grad students allows professors to teach

interesting graduate seminars while pushing the grunt work of grading

and tutoring and teaching intro classes to students and adjuncts. It

provides a massive oversupply of adjunct professors who can be induced

to teach the lower-level classes for very little, thus freeing up

tenured professors for research.

It's hard to see any alternative

to fix the problem, however. The fundamental issue in the academic job

market is not that administrators are cheap and greedy, or that adjuncts

lack a union. It's that there are many more people who want to be

research professors than there are jobs for them...

Unfortunately, I'm

essentially arguing that professors ought to, out of the goodness of

their heart, get rid of their graduate programs and go back to teaching

introductory classes to distracted freshman. Maybe they should do this.

But they're not going to.

All true, but why would anyone look to the beneficiaries of the status quo to solve this - or any other - social ill? The obvious agents of change - here and elsewhere - are the victims of the status quo. And who are the victims of the academic Ponzi scheme? Grad students in low-ranked departments in fields with few non-academic career options.

How on earth can a powerless grad student at a dead-end department remedy the problem of academic malemployment? One career at a time. If you can't get into a department that offers you good job prospects, find something else to do with your life. This is precisely what the title of Megan's article ("Can't Get Tenure?

Then Get a Real Job") suggests, even though her article strangely fails to

follow through.

Of course, a hard-core paternalist could object, "Students are clearly too overconfident to effectively use this simplistic remedy." And a hard-core neoclassical economist could sigh, "People make risky choices all the time. Why should we single out dead-end Ph.D.s for persecution?" But the wise response, as usual, is two-fold.

First, stop using tax money to subsidize foolish decisions. Whatever you think about government subsidies for education, there's no reason for taxpayers to pay to train students for nigh-mythical jobs in French poetry.

Second, show concerned tolerance. Loudly identify the risks that many grad students fail to take seriously. Point out the malcontent of earlier cohorts that took the road the next generation is contemplating. Remind them that the economics Ph.D. is an atypically sweet deal, even at lower-ranked schools. Then leave them alone.

(10 COMMENTS)January 3, 2014

Is Average Over?: Two Equivocal Graphs, by Bryan Caplan

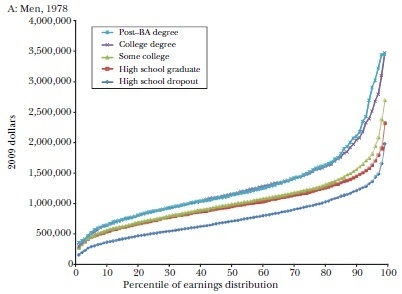

Graph #1 is from 1978:

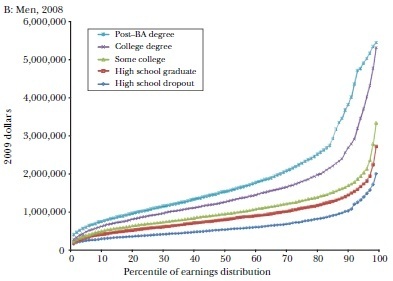

Graph #2 is from 2008:

What's equivocal? Although the 2008 graph definitely has more inequality, the 2008 labor market consistently offers more continuous rewards for achievement. In 1978, "some college" was rarely more lucrative than "high school only," and "post-BA degree" was rarely better than "college degree." The two lines virtually overlap until the 80th percentiles. In 2008, in contrast, the marginal payoff for jumping up a single educational category is visible throughout the entire distribution.

Think about it this way: In 1978, there were effectively only three educational levels. By 2008, there were clearly five. If "average is over" means moves toward bimodality - as Tyler has often claimed in personal conversation - then 1978 fits his story better than the world of today.

(3 COMMENTS)

Tell Me How It Feels to Be a Bad Student, by Bryan Caplan

Why then do we hear so little about the plight of the bad student? The obvious answer: Bad students rarely grow up to be writers or public speakers. (Enlightening counter-example: Comedians). Indeed, bad students rarely grow up to read blogs or comment on them.

"Rarely," however, does not mean "never." My request: If you were ever a bad student, please tell us how it felt. How would you compare it to other sorrows you've experienced? The more details, the better. It is time for your voice to be heard.

(34 COMMENTS)

January 2, 2014

The Orange Moon, by Bryan Caplan

When I returned home, I told my best friend, Adam, what I'd seen.

Me: In Nevada, I saw an ORANGE moon!

Adam: Once I saw a PURPLE moon!!

A few months later, there was an orange moon in Northridge. I quickly pointed it out to Adam.

Me: Now do you believe that I saw an orange moon in Nevada?

Adam: I sure do!

Me: So did you really see a purple moon?

Adam: Nope.

What was Adam's initial motivation? There are two main possibilities:

1. Competitiveness. Adam didn't want to feel like I was better than him by virtue of my special experiences.

2. Poetic justice. Adam thought I was lying, so he "punished" me by telling me an even bigger lie.

When I reflect on this story, I see a major mechanism for the birth of tall tales, urban legends, mythology, and religious miracles. I see Big Foot, the Loch Ness Monster, alien abductions, and much much more. You don't have to believe that anyone is consciously thinking, "And now to fabricate and publicize an absurd lie! Bwa ha ha!" Adam wasn't acting strategically; he was acting impulsively. He heard a crazy story, and his deeply human reaction was to spit back a crazier story to put me in my place.

If I'd pressed him, no doubt Adam would have invented detail after detail: Where he saw his purple moon, the precise shade of purple, the time of year, and so on. And given the frailty of human memory, it's quite conceivable that my childhood friend now sincerely "remembers" seeing a purple moon. Multiply all this by the distortions of hearsay, exemplified by the telephone game, and it's amazing - if not miraculous - that common sense skepticism ever managed to arise, survive, and even thrive.

(5 COMMENTS)

Will on Somin on Judicial Review, by Bryan Caplan

Political ignorance, Somin argues, strengthens the case for judicial

review by weakening the supposed "countermajoritarian difficulty" with

it. If much of the electorate is unaware of the substance or even

existence of policies adopted by the sprawling regulatory state, the

policies' democratic pedigrees are weak. Hence Somin's suggestion that

the extension of government's reach "undercuts democracy more than it

furthers it."An engaged judiciary that enforced the Framers' idea of government's "few and defined" enumerated powers

(Madison, Federalist 45), leaving decisions to markets and civil

society, would, Somin thinks, make the "will of the people" more

meaningful by reducing voters' knowledge burdens. Somin's evidence and

arguments usefully dilute the unwholesome democratic sentimentality and

romanticism that encourage government's pretensions, ambitions and

failures.

Yep.

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers