Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 160

December 1, 2013

Evil in Plain Sight, by Bryan Caplan

It is of course possible that seemingly innocent actions today will lead to mass horrors. Maybe you'll adopt an orphan who grows up to assassinate a world leader, precipitating World War III. But the future is unlikely to damn us for such actions. We don't curse the name of Princip's mother; how was she to know that her son would bring a continent to ruin? As long as the chain of inference from our choices to disaster is long and complex, posterity will give us a pass.

No, the evil for which our descendents will condemn us, if any, will be evil in plain sight. Slavery is a perfect example. Anyone with eyes and a conscience was capable of grasping the wrongness of extorting labor through threats of torture and death, right? Yet American Southerners saw slavery with their own eyes, day after day, and yawned - merely because they knew that their fellow white Southerners were yawning with them.

So what present-day practices plausibly qualify as evil in plain sight? Each of the three leading ideologies of our day - liberalism, conservatism, and libertarianism - suggests an answer. For liberalism: the way we treat animals. For conservatism: the way we treat fetuses. For libertarianism: the way we treat foreigners.

1. Treatment of animals. This Thanksgiving, Americans ate tens of millions of turkeys because they taste good (if well-prepared). We could have eaten vegetables, but we didn't feel like it. Few of us have the steel to kill a turkey face-to-face; instead, we outsource the butchery to professionals long-inured to animal suffering. And of course, such behavior is hardly reserved for the holidays. In our society, even self-styled "vegetarians" regularly consume meat. Under the circumstances, then, it's easy to imagine our descendents viewing us with moral horror.

2. Treatment of fetuses. The United States alone has roughly a million legal abortions a year. If those pregnancies came to term, we would condemn subsequent "termination" as heinous murder. But perform the termination a few weeks earlier, and most of us nonchalantly shrug. The vast majority of these abortions could be avoided - and a life saved - if the mothers endured nine months of discomfort and inconvenience, then put the babies up for adoption. And the best evidence says that women denied abortions soon end up at the same depression and anxiety levels as comparable women who get abortions. Fetuses don't feel pain or think? You can say the same about any healthy adult under anesthesia, but we condemn their murder nonetheless. If the fact that an anesthetized adult is only temporarily unable to feel pain or think is morally significant, why doesn't the same go for fetuses?

Agree or disagree, it is not hard to imagine our descendents finding these arguments convincing, and damning us for evil in plain sight.

3. Treatment of foreigners. If the NYPD bombed Harlem to kill one rampaging murderer, we'd condemn the NYPD agents as murderers. But if the USAF bombs a town in Afghanistan to kill one rampaging murderer, we forgive the bombers - or cheer them on. If the state of Alabama made it a crime for blacks to take white collar jobs, we'd damn them as racist monsters. But if the entire U.S. government makes it a crime for Mexican citizens to take any U.S. job whatsoever, we accept and justify the policy. What's the difference between "fighting crime" and "fighting terrorism"? Between "Jim Crow" and "protecting our borders"? The mere fact that the victims are foreigners, so up is down and wrong is right. Or so our descendents might conclude.

It's quite possible, of course, that our descendents will be as indifferent to the treatment of animals, fetuses, and foreigners as we are. Maybe more so. And even if we were absolutely certain that they would condemn us, that foreknowledge is far from a conclusive argument. Maybe we're right and they're (going to be) wrong.

So why even discuss the views of future generations? To jolt us out of our comfortable conformity. When slavery was popular, it was easy to blithely support it. Foreknowledge that slavery was going to be unpopular would have been Drano for clogged minds. Vividly imagining such a future would have had a similarly clarifying effect. Once intellectually deprived of social support, antebellum Southerners would have been ready for honest moral argument.

The same goes for us. We too can ready ourselves for honest moral argument by dwelling on a future that condemns us. How then would you respond to future generations who condemned our treatment of animals? Of fetuses? Of foreigners?

(35 COMMENTS)

Do-It-Yourself vs. the Minimum Wage, by Bryan Caplan

The logic, as best as I can tell, is that manufacturers sell to a global market. So when manufacturing labor costs go up, factories readily move abroad, implying relatively elastic labor demand (unless, of course, the minimum wage rises all over the world). The service sector, in contrast, sells to a local market. So when service labor costs go up, local customers suck it up and pay more, implying relatively inelastic labor demand.

A nice argument. There is indeed one reason to expect labor demand to be more elastic for manufacturing than services. However, there is another equally compelling reason to expect the opposite: do-it-yourself. In a modern economy, higher manufacturing costs rarely lead consumers to make their own electronics, clothes, or furniture. The fall in quality would be too steep. But higher service costs frequently lead consumers to cook their own meals, mow their own grass, or clean their own homes. The quality's lower, but still quite tolerable.

So what happens when the minimum wage goes up? In manufacturing, there's little substitution into do-it-yourself, so labor demand is relatively inelastic. In services, in contrast, there's a lot of substitution into do-it-yourself, so labor demand is relatively elastic. Precisely the opposite of the Unz view.

If you want to know the actual effect of the minimum wage, of course, you have to combine these two effects. Which effect - global market or do-it-yourself - predominates in the real world? I honestly don't know. Unlike Unz, though, I don't say this because I've never opened an economics textbook. I say this because I've searched for research on the topic, yet failed to find any. If you know of any relevant evidence, I'm all ears.

(0 COMMENTS)

November 30, 2013

Illusory Bubbles, by Bryan Caplan

How should Bitcoin be priced? If there is a 95% chance that it will

soon be worthless and a 5% chance that it will soon hit $1000, then $30

seems like a relatively fair price. That allows for a substantial

expected gain ($50 minus interest costs would be the risk-neutral

price.) But Bitcoin is very risky, so investors need to be compensated

with an above average expected rate of return.

Now consider a point in time where the asset is selling at $30, and

investors have not yet discovered whether it will eventually reach

$1000. Should you predict that the price is a bubble? Yes and no. It

is likely to eventually look like it was a bubble at $30.

Indeed 95% of such assets will eventually see their price collapse.

That's "statistically significant." It's also significant in a

sociological sense. Those that call "bubble" when the price is at $30

will be right 95% of the time, and hence will be seen as having the

"correct model" of bubbles by the vast majority of people. Those who

denied bubble will be wrong 95% of the time, and will be seen as being

hopelessly naive by the average person. And this is despite the fact that in all these cases there is no bubble, as by construction I assumed the EMH was exactly true.

Conclusion:

I predict that eventually the price of Bitcoins will fall sharplyOf course, this story is a lot easier to believe for weird new assets like Bitcoin than for familiar old assets like the entire U.S. housing stock - especially when investors actually wrote down their probability distributions. (1 COMMENTS)

(from some level of which I am not able to predict) and people will

vaguely recall:"Wasn't Scott Sumner the guy who denied Bitcoins was a bubble? What an idiot."

Why Buildings Aren't Taller, by Bryan Caplan

UrbanWhat gives?

economics studies the spatial distribution of activity. In most urban

econ models, the reason that cities aren't taller is that, per square

meter of useable space, taller buildings cost more to physically make.

(Supporting quotes below.) According to this usual theory, buildings

only get taller when something else compensates for these costs, like a

scarce ocean view, or higher status or land prices.Knowing this, and wondering how tall future cities might get, I went

looking for data on just how fast building cost rises with height. And I

was surprised to learn: within most of the usual range, taller

buildings cost less per square meter to build.

Perhaps

the above figures are misleading somehow. But we know that taking land

prices, higher status, and better views into account would push for

even taller buildings. And a big part of higher costs for heights that

are rare used could just be from less learning due to less experience

with such heights. So why aren't most buildings at least 20 stories

tall?Perhaps tall buildings have only been cheaper recently. But the Hong

Kong data is from twenty years ago, and most buildings made in the last

years are not at least 20 stories tall. In fact, in Manhattan new residential buildings have actually gotten shorter.

Perhaps capital markets fail to concentrate enough capital in builders'

hands to enable big buildings. But this seems hard to believe.Perhaps trying to build high makes you a magnet for litigation, envy,

and corrupt regulators. Your ambition suggests that you have deeper

pockets to tax, and other tall buildings nearby that would lose status

and local market share have many ways to veto you. Maybe since most tall

buildings are prevented local builders have less experience with them,

and thus have higher costs to make them. And many few local builders are

up to the task, so they have market power to demand higher prices.Maybe local governments usually can't coordinate well to build

supporting infrastructure, like roads, schools, power, sewers, etc., to

match taller buildings. So they veto them instead. Or maybe local

non-property-owning voters believe that more tall buildings will hurt

them personally.

Further proof, by the way, that the Tiebout model is wildly over-optimistic.

(3 COMMENTS)November 27, 2013

Means-Testing and Behavioral Econ, by Bryan Caplan

For dogmatic neoclassical economists, this settles the question. But no one should be a dogmatic neoclassical economist. Empirically, the equivalence remains an open question. Behavioral economics has repeatedly shown us that framing matters; people may simply fail to mentally equate "marginal benefit reduction" with "marginal tax increase." This is especially plausible when the marginal benefit reduction happens far in the future, and the benefit formula is poorly defined in any case.

Take me. Conceptually, I know that my future Social Security benefits have something to do with how much I pay in Social Security taxes. Yet when I weigh whether to pursue extra income, I've honestly never considered this effect. In my mind, I round that eventual gain down to zero.

Of course, if means-testing gets adopted before my retirement, my rounding down to zero will turn out to be justified. But as far as I can tell, most people round down to zero - even if they plan to retire long before means-testing is likely to be adopted.

On what basis do I say "As far as I can tell"? Simple: I've never heard anyone - even a fellow economist - claim to factor extra Social Security benefits into a personal cost-benefit calculation. Indeed, the only time the issue even comes up is in discussions of public policy. Many people, in contrast, openly discuss how taxes affect their behavior.

While I believe in the power of introspection, I'd definitely like to supplement my introspection with careful empirical research on this topic. Yet Google Scholar seems oddly empty of articles on the topic. Question: Is there any scholarly evidence - pro or con - that I'm missing? If so, please share.

(13 COMMENTS)

November 25, 2013

Rising Male Non-Employment: Supply, not Demand, by Bryan Caplan

My friend and coauthor Larry Summers touched onBut this story is hard to reconcile with one of my all-time favorite Tyler Cowen Assorted Links, "Why the poor don't work, in the words of the poor":

this a year and a bit ago when he was here giving the Wildavski lecture. He was

talking about the extraordinary decline in American labor force participation

even among prime-aged males-that a surprisingly large chunk of our male

population is now in the position where there is nothing that people can think

of for them to do that is useful enough to cover the costs of making sure that

they actually do it correctly, and don't break the stuff and subtract value when

they are supposed to be adding to it.

Each year, the bureau asksPoor men are admittedly more likely than poor women to say they don't work because they can't find a job. Yet only 20% of men below the poverty line in 2012 said this. This is a far cry from explaining steadily rising male non-employment year in, year out. While I am very open to concerns about involuntary unemployment, the long-term story really does seem to be that most non-employed men (a) produce output worth more than the minimum wage, but (b) prefer idleness to their market wage.

jobless Americans why it is they've been out of work. And

traditionally, a only a small percentage of impoverished adults actually

say it's because they can't find employment, a point that New York

University professor Lawrence Mead, one of the intellectual architects

of welfare reform, made to Congress in recent testimony.

In 2007, for instance, 6.4 percent of adults who lived under the

poverty line and didn't work in the past year said it was because

they couldn't find a job. As of 2012, the figure had more than doubled

to a still-small 13.5 percent. By comparison, more than a quarter said

they stayed home for family reasons and more than 30 percent cited a

disability.

(4 COMMENTS)

November 24, 2013

Hoxby vs. Dale-Krueger on the Selectivity Premium, by Bryan Caplan

There's a sizable literature on the topic, but the single most famous paper is Dale and Krueger's 2002 QJE piece, "Estimating the Payoff to Attending a More Selective College." (summaries here and here) While delving into this literature, I came across a harsh critique of Dale-Krueger in Caroline Hoxby's survey article on the topic:

Finally, Dale and Krueger (2002) compute lower rates of return but their estimates are based on an identification strategy that is much less credible. They compare students who gained admission to approximately the same menu of colleges. They compare the earnings of those who, from within the same menu, chose a much more-selective college and a much less-selective college. However, since at least 90 percent of students who have the same menu similarly choose the more-selective college (s) within it, the strategy generates estimates that rely entirely on the small share of students who make what is a very odd choice. These are students who know that they could choose a much more-selective college and who have already expressed interest in a much more-selective college (they applied), yet, they choose differently than 9 out of 10 students. Almost certainly, these odd students are characterized by omitted variables that affect both their college decision and their later life outcomes.Soon afterwards, though, I learned that Dale and Krueger's 2011 working paper directly replies to Hoxby:

Hoxby (2009) mistakenly reports that only 10 percent of students in the C&B sample used in Dale and Krueger (2002) did not attend the most selective college to which they were admitted. However, similar to the results for the sample used here, the correct figure is 38 percent.And:

Finally, it is possible that our estimates are affected by students sorting into the colleges they attended from their set of options based on their unobserved earnings potential. About 35 percent of the students in each cohort in our sample did not attend the most selective school to which they were admitted. Our analysis indicates that students who were more likely to attend the most selective school to which they were admitted had observable characteristics that are associated with higher earnings potential. If unobserved characteristics bear a similar relationship to college choice, then our already-small estimates of the payoff from attending a selective college would be biased upward.Several people I know thought the 2002 Dale-Krueger paper oversold its results; while some measures of selectivity didn't pay, others did. The new paper, though, is almost unequivocal: Once you correct for pre-existing ambition, its hard to find any measure of selectivity that pays.

Overall, the evidence for a financial payoff of selectivity is a lot weaker than I expected. This finding is admittedly puzzling from a signaling point of view, because it seems like more selective educations send a stronger message to the labor market. But the finding is equally puzzling from a human capital point of view, because it seems like more selective educations do more to hone students' skills. Hmm.

(5 COMMENTS)

November 21, 2013

Gun Grabbing: A Reversal of Fortune, by Bryan Caplan

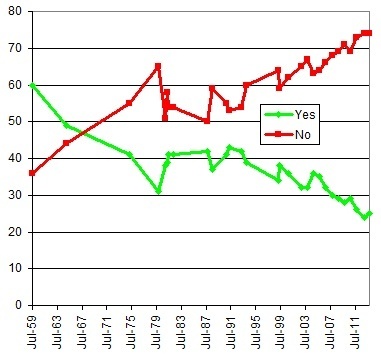

What about the possession of pistols and revolvers -- do you think there should be a law which would forbid possession of this type of gun except by the police or other authorized person?The question was slightly changed over the years. Since 1980 it's been:

Do you think there should or should not be a law that would ban the possession of handguns, except by the police or other authorized persons?The current breakdown is just what Europeans would expect of Cowboy Nation. Only 25% of Americans say "Yes, should be" - versus 74% who say, "No, should not be." But if you think this reflects a long-standing American tradition, you're dead wrong. Back in 1959, the breakdown was 60% yes, 36% no. Support for gun-grabbing fell almost non-stop during the ensuing decades, with just one odd reversal in 1979. The full survey history, 1959-2013:

Gun rights activists might be tempted to invoke the Whig theory of history: Evidence and argument have slowly but surely won the day. But as a general rule, I don't see the slightest reason to believe such stories. More and better outreach? Also hard to believe. During my 18 non-libertarian years, I heard occasional anti-gun propaganda but no pro-gun propaganda.

What's a better story?

(20 COMMENTS)

November 20, 2013

Koyama on Working Conditions During the Industrial Revolution, by Bryan Caplan

My memory was not 100% accurate as the best estimate for

male working hours in London in England in 1830 (when working hours were at

their absolute longest) is actually 3356 rather than 3000. This estimate is from Voth's use of court

data in order to reconstruct how individuals used their time (2001). By 1870 other estimates put it at 2755.

Working hours in excess of 3000 hours

per year are seen as extraordinarily long in comparison to more recent episodes

of industrialization so 4000 in the US still seems unrealistic (though it is

not that much greater than the highest upper bound some historians have

estimated). Of course, the point is

that workers seemed to prefer working long hours in factories and using their

wages to buy newly available consumption goods (cotton underwear which could be

washed easily must have drastically increased consumer surplus relative to

scratchy woolen underwear) rather than working in agriculture (where wages were

lower and hours probably also long at least during some periods of the year).

In the UK and by extension the US, if a household had an able bodied adult male

able to work then normally they would not be desperately poor (Robert Allen's

wage series show that real wages in English and the US were perhaps 2 or 3 times

southern European wages and people were

able to survive there). One reason why

perceptions of poverty increased in England during the early 19th century (in

addition to the point that it was just more concentrated and hence visible) was

to due with the social dislocation associated with urbanization (much higher

rates of illegitimacy, more single earner households etc.). Families without male earners were indeed

desperately poor and reliant on very young children working and these

households became more common during Industrialization.

(10 COMMENTS)

November 19, 2013

The Economic Illiteracy of High School History, by Bryan Caplan

Every now and then, though, I question the accuracy of my memory. Could my history textbooks really have been so awful? The other night, overcome by nostalgia, I decided to check. Ray Billington's American History Before 1877 was one of our two main texts. I flipped straight to the section on early industrialization and learned the following:

The Plight of the Worker. The rise of the factory system placed such a gulf between employers and employees that the former no longer took a personal concern in the welfare of the latter. As competition among manufacturers was keen and the labor supply steadily increasing through foreign immigration, they were able to inflict intolerable working conditions on laborers. Hours of labor were from thirteen to fifteen a day, six days a week, while wages were so low after the Panic of 1837 that a family could exist only if all worked. Hence child labor was common. Factories were usually unsanitary, poorly lighted, and with no protection provided from dangerous machinery. Security was unknown; workers were fired whenever sickness or age impaired their efficiency. As neither society nor the government was concerned with these conditions, the workers were forced to organize to protect themselves.The good news: My memory turns out to be quite accurate. The bad news: Billington's economic illiteracy is more severe than I thought. The more economics you know, the worse he seems. Misconceptions this awful have to be addressed sentence-by-sentence - and sarcasm cannot be avoided.

The rise of the factory system placed

such a gulf between employers and employees that the former no longer

took a personal concern in the welfare of the latter.

First problem: The main determinant of wages and working conditions is workers' marginal productivity, not "personal concern." Are we really supposed to believe that implicit employer charity was a large fraction of employee compensation during the pre-modern era?

Second problem: Personal concern clearly plays some role in modern businesses (see here and here for starters). Today's firms exhibit a much larger "gulf" between employers and employees than could possibly have existed in the first half of the 19th century. Are we really supposed to believe that personal concern was important in the pre-modern period, disappeared in the 19th century, then returned in the 20th?

Third problem: Keynesian economists emphasize that wage fairness norms lead to labor surpluses, also known as "unemployment." So the overall effect of greater personal concern on workers' well-being is unclear. Mediocre jobs you can actually get are far better than great jobs you can't get.

As competition

among manufacturers was keen and the labor supply steadily increasing

through foreign immigration, they were able to inflict intolerable

working conditions on laborers.

"Keen competition" should make it harder, not easier, for employers to pay workers less than their marginal productivity. And if conditions were so "intolerable," why did immigrants keep pouring in? Why did agricultural workers keep moving to the factories?

Hours of labor were from thirteen to fifteen a day, six days a week, while wages were so low after the Panic of 1837 that a family could exist only if all worked.

The second sentence is absolutely absurd. Did every family in 1837 that failed to employ every family member (babies included?) starve to death? Victims of the Irish potato famine - which began a full eight years later - might immigrate to such hellish conditions, but no one else would.

Billington's sloppy language also makes his claim that the typical workyear exceeded 4000 hours per year very hard to believe. One of GMU's economic historians tells me that 3000 hours per year is a much more reasonable figure.

Hence child labor

was common.

Compared to growing up on a 19th-century farm?

Factories were usually unsanitary, poorly lighted, and

with no protection provided from dangerous machinery.

No protection at all? So smiths didn't wear gloves? Construction workers didn't wear boots?

Security was

unknown; workers were fired whenever sickness or age impaired their

efficiency.

Automatic firing for sickness? Wouldn't this lead to high turnover costs, especially considering the unsanitary conditions?

Automatic firing for age? So 19th-century firms had no deadwood at all? Wow.

As neither society nor the government was concerned with

these conditions, the workers were forced to organize to protect

themselves.

Aren't workers part of "society"? If conditions were really as bad as Billington says, how could workers find the spare time to organize? And if workers were "forced to organized," how come most workers didn't organize? While we're on the subject, what about the idea that successful unionization has a negative employment effect for workers - especially workers who aren't in the union?

Even more aggravatingly, Billington barely mentions the consumers of early factory production. The rise of mass production implies the rise of mass consumption. "Plight of the workers" indeed.

So what should history textbooks say about these matters? This: Working conditions during the early Industrial Revolution were bad by modern standards, but a major improvement by the standards of the time. Factory work looked good to people raised on backbreaking farm labor - and it looked great to the many immigrants who flocked to the rising centers of industry from all over the world. This alliance of entrepreneurs, inventors, and workers peacefully kickstarted the modern world that we enjoy today.

And what of the "workers' movement"? A halfway decent textbook would emphasize that it wasn't quantitatively important. Few workers belonged, and they didn't get much for their efforts. Indeed, "workers' movement" is a misnomer; labor unions didn't speak for most workers, and were often dominated by leftist intellectuals. A fully decent textbook would discuss the many possible negative side effects of labor market regulation and unionization - so students realize that the critics of economic populism were neither knaves nor fools.

The Big Picture: Industrialization was the greatest event in human history. Critics then and now were foolishly looking a gift horse in the mouth. Until every student knows these truths by heart, history teachers have not done their job.

(17 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers