Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 158

January 1, 2014

Employment and the Return to Education: The Right Way to Count, by Bryan Caplan

People with more education don't just make more money if they have jobs; they're more likely to have jobs in the first place. As a result, the earnings premium now greatly exceeds the wage premium. Consider the following caricature approximation of modern male earnings:

(a) College grads with full-time jobs earn 70% more than high school grads with full-time jobs.

(b) 95% of college grads, but only 70% of high school grads, have full-time jobs. Everyone else receives $0 of income.

College grads in this scenario enjoy a 70% wage premium but a 131% earnings premium. This is easy to compute: 1.70*.95/.7=2.31, indicating that college grads earn 2.31 times as much as high school grads.

Ability bias aside, is this computation appropriate? It depends. If a college degree really reduced your probability of involuntary unemployment from 25% to 5%, then multiplying the wage effect and the employment effect is fine. College is your ticket out of a hellish situation.

But what if your unemployment is voluntary - in the sense that, given the market wage for people with your skills, you prefer not to work? Then multiplying the wage effect by the employment effect seems like double-counting. Yes, college raises what you actually earn by 131%, but it only raises what you're able to earn by 70%.

Not convinced? Suppose college graduates worked more solely because college speeds up your hedonic treadmill. After four years of high-achievement socialization, college grads feel like losers unless they earn at least $100,000 a year. High school grads, in contrast, feel perfectly satisfied with half that. Or suppose that colleges subtly indoctrinate women with the view that material success is much more important than maternal success. Why should merely shifting priorities from kids to cash count as a personal "benefit"? This is just the crude materialism economists are often mocked for espousing.

Now recall that official statistics distinguish between the employed, the unemployed, and those who are "out of the labor force." The lazy response to my point is to treat the officially unemployed as "involuntarily unemployed" and the officially "out of the labor force" as "voluntarily unemployed." So if college grads' employed/unemployed/out of the labor force breakdown is 95/3/2, and high school grads' breakdown is 70/10/20, the "correct" college earnings premium is 1.70*(95/98)/(70/80)=94% - more than 70%, but a far cry from 131%.

The diligent response, though, is to adjust official unemployment numbers for the "discouraged worker" and "prideful worker" effects. At least outside of deep recessions, I tend to think that the latter effect is larger. But either way, you've got to admit: Unless everyone without a job is involuntarily unemployed, counting the full employment gap as a "benefit" of education is not reasonable.

(2 COMMENTS)

(a) College grads with full-time jobs earn 70% more than high school grads with full-time jobs.

(b) 95% of college grads, but only 70% of high school grads, have full-time jobs. Everyone else receives $0 of income.

College grads in this scenario enjoy a 70% wage premium but a 131% earnings premium. This is easy to compute: 1.70*.95/.7=2.31, indicating that college grads earn 2.31 times as much as high school grads.

Ability bias aside, is this computation appropriate? It depends. If a college degree really reduced your probability of involuntary unemployment from 25% to 5%, then multiplying the wage effect and the employment effect is fine. College is your ticket out of a hellish situation.

But what if your unemployment is voluntary - in the sense that, given the market wage for people with your skills, you prefer not to work? Then multiplying the wage effect by the employment effect seems like double-counting. Yes, college raises what you actually earn by 131%, but it only raises what you're able to earn by 70%.

Not convinced? Suppose college graduates worked more solely because college speeds up your hedonic treadmill. After four years of high-achievement socialization, college grads feel like losers unless they earn at least $100,000 a year. High school grads, in contrast, feel perfectly satisfied with half that. Or suppose that colleges subtly indoctrinate women with the view that material success is much more important than maternal success. Why should merely shifting priorities from kids to cash count as a personal "benefit"? This is just the crude materialism economists are often mocked for espousing.

Now recall that official statistics distinguish between the employed, the unemployed, and those who are "out of the labor force." The lazy response to my point is to treat the officially unemployed as "involuntarily unemployed" and the officially "out of the labor force" as "voluntarily unemployed." So if college grads' employed/unemployed/out of the labor force breakdown is 95/3/2, and high school grads' breakdown is 70/10/20, the "correct" college earnings premium is 1.70*(95/98)/(70/80)=94% - more than 70%, but a far cry from 131%.

The diligent response, though, is to adjust official unemployment numbers for the "discouraged worker" and "prideful worker" effects. At least outside of deep recessions, I tend to think that the latter effect is larger. But either way, you've got to admit: Unless everyone without a job is involuntarily unemployed, counting the full employment gap as a "benefit" of education is not reasonable.

(2 COMMENTS)

Published on January 01, 2014 21:08

December 31, 2013

Tell Me What "Average Is Over" Looks Like , by Bryan Caplan

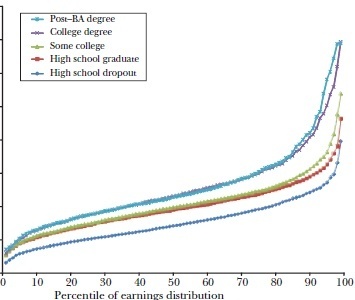

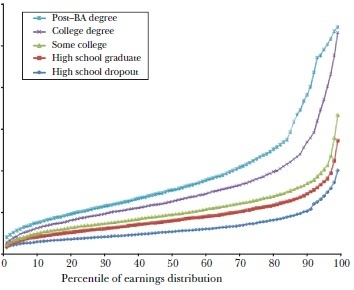

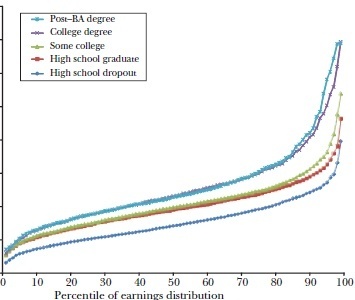

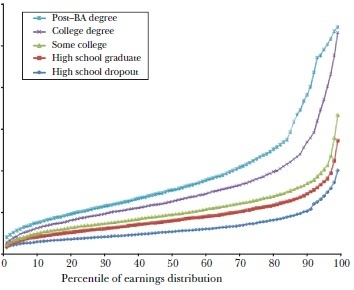

Here are two graphs of lifetime male income distribution broken down by educational attainment. One is for 1978, the other from 2008. I deliberately redact the years and dollar values to preserve the mystery.

Graph #1:

Graph #2:

Now you tell me: Without cheating by looking at the year, in which graph is "average over" - and why?

(3 COMMENTS)

Graph #1:

Graph #2:

Now you tell me: Without cheating by looking at the year, in which graph is "average over" - and why?

(3 COMMENTS)

Published on December 31, 2013 21:08

December 30, 2013

The Prideful Worker Effect, by Bryan Caplan

Both economists and laymen often claim that unemployment statistics paint an overly rosy picture of the labor market. Why? Because they refuse to count

discouraged workers

as "unemployed." To qualify as "unemployed," you have to look for a job. But especially during recessions, many workers who genuinely want jobs abandon their search because their efforts seem hopeless.

The next step: As soon as the discouraged workers tell the government they've stopped looking, they're officially converted from "unemployed" to "out of the labor force." This problem seems unusually important during the recent recovery - the unemployment rate is falling, but so is the labor force participation rate.

I have no doubt that the Discouraged Worker Effect is real and sizable. But almost no one discusses a potentially important offsetting effect. I call it the Prideful Worker Effect. Key idea: Some officially unemployed workers have unreasonably high expectations. They focus their job search on positions for which they are underqualified - and ignore lower-status but more realistic opportunities. Officially, they're "unemployed." In reality, though, we should probably consider them "out of the labor force."

Intuitively, I'm not an unemployed astronaut, because I'm not an astronaut at all. If I held out for a job as an astronaut, the statistician who codes me as "unemployed" turns my delusion into a folie a deux.

The Prideful Worker Effect, like the Discouraged Worker Effect, is a matter of degree. We could argue for hours about whether any particular individual belongs in either box. So it's no wonder that official statistics prefer bright lines, even if the bright lines are misleading. But vagueness has not prevented economists from trying to measure the prevalence of discouraged workers. Why not come up with some plausible measures of prideful workers, and see what we find?

(4 COMMENTS)

The next step: As soon as the discouraged workers tell the government they've stopped looking, they're officially converted from "unemployed" to "out of the labor force." This problem seems unusually important during the recent recovery - the unemployment rate is falling, but so is the labor force participation rate.

I have no doubt that the Discouraged Worker Effect is real and sizable. But almost no one discusses a potentially important offsetting effect. I call it the Prideful Worker Effect. Key idea: Some officially unemployed workers have unreasonably high expectations. They focus their job search on positions for which they are underqualified - and ignore lower-status but more realistic opportunities. Officially, they're "unemployed." In reality, though, we should probably consider them "out of the labor force."

Intuitively, I'm not an unemployed astronaut, because I'm not an astronaut at all. If I held out for a job as an astronaut, the statistician who codes me as "unemployed" turns my delusion into a folie a deux.

The Prideful Worker Effect, like the Discouraged Worker Effect, is a matter of degree. We could argue for hours about whether any particular individual belongs in either box. So it's no wonder that official statistics prefer bright lines, even if the bright lines are misleading. But vagueness has not prevented economists from trying to measure the prevalence of discouraged workers. Why not come up with some plausible measures of prideful workers, and see what we find?

(4 COMMENTS)

Published on December 30, 2013 21:05

December 29, 2013

How Bad Is White Nationalism?, by Bryan Caplan

White nationalism is one of the most reviled ideologies on earth. But what exactly is so awful about it? Menachem Rosensaft's piece in Slate quotes some leading white nationalists, but never really explains why this nationalism is worse than all other nationalisms.

As you'd expect, white nationalists dominate Rosensaft's comments. Several point out that he's is a staunch Zionist, and quip, "Nationalism for me but not for thee." I'm a staunch anti-nationalist, so I'm tempted agree with this critique but "level down" - to embrace the view that every form of nationalism is just as bad as white nationalism.

What's so bad about nationalism in general? Perverse moral priorities. Human beings are naturally biased in favor of the groups they identify with; psychologists call this "in-group bias." Once you recognize this human failing, your moral priority should be bending over backwards to treat out-groups justly. No nationalism I've ever heard of even tries to do so.* Instead, nationalisms embrace in-group bias - shouting and shoving to maximize their side's share of wealth, power, and especially status.** This brief exchange in The Painted Veil aptly boils down the iniquity of nationalist thinking:

1. Historical track record. Even if you only count Nazism and European colonialism, white nationalism has a massive body count. But several non-European nationalisms - especially Chinese and Japanese - are in the same bloody ballpark.

2. Expected track record. Given white nationalism's ongoing half century of pariah status, it seems unlikely to do much damage in the foreseeable future. For the time being, white nationalism looks about as dangerous as Luxembourgian nationalism.

3. Expected track record conditional on popularity. Even without white nationalism to urge them on, First World

governments continue to kill large numbers of innocent people in the Third World

to prevent statistically trivial harms. If white nationalism were an influential doctrine, it is reasonable to expect far worse treatment of Third World innocents. After all, white-majority countries still have greater military power than all other countries combined. Furthermore, since they have relatively prosperous economies, they could easily make their military dominance even more lop-sided. While there's a chance this could ultimately supplant even worse non-white tyrannies, the "transitional period" would be hell on earth. By this standard, non-white nationalism poses a considerably smaller - though still potentially apocalyptic - threat.

4. The viciousness of the advocates. Being unpopular doesn't make a moral theory more or less evil. But as I've argued before, we should expect people who support evil views despite unpopularity to be especially morally vicious. This prediction seem to fit the facts well. The average white nationalist really is angry and hateful. Indeed, it is very hard to locate white nationalists who are even civil to people who disagree with them. (Feel free to prove me wrong in the comments... or right, as the case may be). Reliable statistics on contemporary white nationalist violence are hard to find, but if you divide white nationalists' most visible crimes by their tiny population, their per-capita violent crime rate looks very high indeed.

So how bad is white nationalism? Back when white nationalism was popular, its sins were massive, but hardly unique. The doctrine currently does little harm because it's so rare. If however white nationalism regained popularity, it would be a cataclysmic disaster because white-majority countries have the firepower to wreck the havoc other nationalist movements can only fantasize about. Finally, white nationalists score as badly as you would expect in terms of moral character. Intellectually, their nationalism is no worse than hundreds of other nationalisms; but the kind of people willing to embrace white nationalism despite the stigma against it really do tend to be hateful, if not violent.

* If you've got a solid counter-example of a self-styled "nationalist"

movement whose top priority is (or was) treating out-groups justly, please

share in the comments.

** Doesn't this critique condemn the family as well? It would, if people

thought it morally praiseworthy to treat outsiders unjustly to

benefit their families. Fortunately, few parents consider it

morally praiseworthy for their kids to bully, cheat, and rob

non-relatives. Most of us recognize that we should strive to treat non-family members justly precisely because familial love tempts us to do otherwise.

(25 COMMENTS)

As you'd expect, white nationalists dominate Rosensaft's comments. Several point out that he's is a staunch Zionist, and quip, "Nationalism for me but not for thee." I'm a staunch anti-nationalist, so I'm tempted agree with this critique but "level down" - to embrace the view that every form of nationalism is just as bad as white nationalism.

What's so bad about nationalism in general? Perverse moral priorities. Human beings are naturally biased in favor of the groups they identify with; psychologists call this "in-group bias." Once you recognize this human failing, your moral priority should be bending over backwards to treat out-groups justly. No nationalism I've ever heard of even tries to do so.* Instead, nationalisms embrace in-group bias - shouting and shoving to maximize their side's share of wealth, power, and especially status.** This brief exchange in The Painted Veil aptly boils down the iniquity of nationalist thinking:

Businessman: What about support from Chiang Kai-shek? Where does he stand on this?On reflection, though, I should resist the intellectual temptation to equate all nationalisms. Nothing in my critique rules out moral distinctions between them. So how does white nationalism measure up on the most obvious metrics?

Townsend: He's a nationalist. He will stand on the side of the Chinese. That's why they call themselves "nationalists."

1. Historical track record. Even if you only count Nazism and European colonialism, white nationalism has a massive body count. But several non-European nationalisms - especially Chinese and Japanese - are in the same bloody ballpark.

2. Expected track record. Given white nationalism's ongoing half century of pariah status, it seems unlikely to do much damage in the foreseeable future. For the time being, white nationalism looks about as dangerous as Luxembourgian nationalism.

3. Expected track record conditional on popularity. Even without white nationalism to urge them on, First World

governments continue to kill large numbers of innocent people in the Third World

to prevent statistically trivial harms. If white nationalism were an influential doctrine, it is reasonable to expect far worse treatment of Third World innocents. After all, white-majority countries still have greater military power than all other countries combined. Furthermore, since they have relatively prosperous economies, they could easily make their military dominance even more lop-sided. While there's a chance this could ultimately supplant even worse non-white tyrannies, the "transitional period" would be hell on earth. By this standard, non-white nationalism poses a considerably smaller - though still potentially apocalyptic - threat.

4. The viciousness of the advocates. Being unpopular doesn't make a moral theory more or less evil. But as I've argued before, we should expect people who support evil views despite unpopularity to be especially morally vicious. This prediction seem to fit the facts well. The average white nationalist really is angry and hateful. Indeed, it is very hard to locate white nationalists who are even civil to people who disagree with them. (Feel free to prove me wrong in the comments... or right, as the case may be). Reliable statistics on contemporary white nationalist violence are hard to find, but if you divide white nationalists' most visible crimes by their tiny population, their per-capita violent crime rate looks very high indeed.

So how bad is white nationalism? Back when white nationalism was popular, its sins were massive, but hardly unique. The doctrine currently does little harm because it's so rare. If however white nationalism regained popularity, it would be a cataclysmic disaster because white-majority countries have the firepower to wreck the havoc other nationalist movements can only fantasize about. Finally, white nationalists score as badly as you would expect in terms of moral character. Intellectually, their nationalism is no worse than hundreds of other nationalisms; but the kind of people willing to embrace white nationalism despite the stigma against it really do tend to be hateful, if not violent.

* If you've got a solid counter-example of a self-styled "nationalist"

movement whose top priority is (or was) treating out-groups justly, please

share in the comments.

** Doesn't this critique condemn the family as well? It would, if people

thought it morally praiseworthy to treat outsiders unjustly to

benefit their families. Fortunately, few parents consider it

morally praiseworthy for their kids to bully, cheat, and rob

non-relatives. Most of us recognize that we should strive to treat non-family members justly precisely because familial love tempts us to do otherwise.

(25 COMMENTS)

Published on December 29, 2013 21:00

December 28, 2013

Grow the Respect Pie, by Bryan Caplan

I second David's praise for Noah's piece on respect. But why talk about "redistributing respect" rather than "showing more respect"? In econ jargon, why not increase the size of the respect pie instead of squabbling over the size of the slices?

Respect really is close to a free lunch. If you want to show more respect to workers at McDonald's, you don't have to compensate by snubbing bankers. Noah's praise of Japanese respect bears this out. Japan doesn't just have more equal respect; it has higher respect per-capita.

And while we're ratcheting up respect, why not push for more friendliness - and less misanthropy - as well?

(3 COMMENTS)

Respect really is close to a free lunch. If you want to show more respect to workers at McDonald's, you don't have to compensate by snubbing bankers. Noah's praise of Japanese respect bears this out. Japan doesn't just have more equal respect; it has higher respect per-capita.

And while we're ratcheting up respect, why not push for more friendliness - and less misanthropy - as well?

(3 COMMENTS)

Published on December 28, 2013 21:20

Who These Kids Are, by Bryan Caplan

Fab Rojas' response to my last post, reprinted with his permission.

I just read your post about the 10% of students who do nothing in a

college course. They don't attend, take exams or other appear in any

other capacity. I teach a lot of required classes and I'm the Director

of Undergraduate Studies at my department, so

I have a bit of experience working with these students.

My observation is that most "no-shows" fall into two categories.

First, many students have drug or alcohol problems. One of the realities

of college these days is that a large minority of students treat it is a

giant party. Unsurprisingly, many of these

students are unwilling or unable to participate in their

courses. Second, many students lack maturity. For whatever reason, they

simply can't follow through on plans, or deal with challenging classes.

A small fraction of "no-shows" do have legitimate reasons. A few

genuinely believed that they dropped the course. Others have very

serious personal challenges such as being the victim of sexual assault,

personal illness, or a severe family problem, like

having parents who are getting a divorce.

The instructors who read the blog may wonder how to distinguish

between these students. Physicians, or the campus health service, will

usually provide a note on letter head verifying illness. Many campuses

have "Student Advocate" offices for students who

are having genuine personal problems. They are usually happy to provide

verification, long as it doesn't violate confidentiality.Brief reply from Bryan: Very plausible, but you still usually need student myopia and/or perverse parental incentives to explain why these students fail to officially withdraw from their classes, saving many thousands of dollars.

(6 COMMENTS)

I just read your post about the 10% of students who do nothing in a

college course. They don't attend, take exams or other appear in any

other capacity. I teach a lot of required classes and I'm the Director

of Undergraduate Studies at my department, so

I have a bit of experience working with these students.

My observation is that most "no-shows" fall into two categories.

First, many students have drug or alcohol problems. One of the realities

of college these days is that a large minority of students treat it is a

giant party. Unsurprisingly, many of these

students are unwilling or unable to participate in their

courses. Second, many students lack maturity. For whatever reason, they

simply can't follow through on plans, or deal with challenging classes.

A small fraction of "no-shows" do have legitimate reasons. A few

genuinely believed that they dropped the course. Others have very

serious personal challenges such as being the victim of sexual assault,

personal illness, or a severe family problem, like

having parents who are getting a divorce.

The instructors who read the blog may wonder how to distinguish

between these students. Physicians, or the campus health service, will

usually provide a note on letter head verifying illness. Many campuses

have "Student Advocate" offices for students who

are having genuine personal problems. They are usually happy to provide

verification, long as it doesn't violate confidentiality.Brief reply from Bryan: Very plausible, but you still usually need student myopia and/or perverse parental incentives to explain why these students fail to officially withdraw from their classes, saving many thousands of dollars.

(6 COMMENTS)

Published on December 28, 2013 06:26

December 27, 2013

Who Are These Kids?, by Bryan Caplan

About 10% of my enrolled undergraduate students literally do nothing in my class. They attend zero lectures, do zero homework, and fail to show up for the midterm or the final. Yet when I'm handing out grades, the official roster confirms that they paid their tuition in full.

I understand dropping out. But if you're going to drop out, why not drop out officially, so you get a tuition refund? Under GMU rules, students can only get a 100% refund if they drop before the second week starts. But they can get a 67% refund during the next two weeks, and a 33% refund until the end of the first month. Do students who do no work during month #1 seriously fail to ask for a refund because they imagine they'll turn over a new leaf starting in month #2?

The obvious explanation, of course, is that it is the parents of these errant students, not the errant students themselves, who would pocket any refund. Students refuse to officially drop because they prefer to delay the day of parental wrath. To make this story work, however, either (a) students who do zero work must be pathologically myopic, or (b) parents of students who do zero work must be perversely forgiving.

Questions:

1. All my undergrad courses are upper division. Are students who do zero work even more common in intro classes?

2. Are pathologically myopic students and perversely forgiving parents really the whole story here? Or is something else going on?

Answers from students who did zero work in at least one class are especially welcome.

(20 COMMENTS)

I understand dropping out. But if you're going to drop out, why not drop out officially, so you get a tuition refund? Under GMU rules, students can only get a 100% refund if they drop before the second week starts. But they can get a 67% refund during the next two weeks, and a 33% refund until the end of the first month. Do students who do no work during month #1 seriously fail to ask for a refund because they imagine they'll turn over a new leaf starting in month #2?

The obvious explanation, of course, is that it is the parents of these errant students, not the errant students themselves, who would pocket any refund. Students refuse to officially drop because they prefer to delay the day of parental wrath. To make this story work, however, either (a) students who do zero work must be pathologically myopic, or (b) parents of students who do zero work must be perversely forgiving.

Questions:

1. All my undergrad courses are upper division. Are students who do zero work even more common in intro classes?

2. Are pathologically myopic students and perversely forgiving parents really the whole story here? Or is something else going on?

Answers from students who did zero work in at least one class are especially welcome.

(20 COMMENTS)

Published on December 27, 2013 14:15

Gifts, Efficiency, and Social Desirability Bias, by Bryan Caplan

Is cash the only efficient gift? Pure economic theory points to two contradictory answers:

1. Yes, because of the receiver's demonstrated preference. Suppose gift X costs $100. If you gave the receiver $100, would he still have spent the money on X? Almost certainly not, so he must prefer whatever he bought with the $100 to X.

2. No, because of the giver's demonstrated preference. Suppose gift X costs $100. The giver could have given $100 instead of X, but gave X instead. So he must prefer giving X to its cash equivalent.

When polled, economists on the IGM panel heavily favor some version of #2. Many even ridicule #1 as psychologically obtuse. Angus Deaton quips, "This is the sort of narrow view that rightly gives economics bad name." But neither side on the IGM even mentions a massive body of psychological research on Social Desirability Bias (SDB) that weighs heavily in #1's favor. Quick version: When lies sound better than the truth, human beings often lie.

Consider "I enjoy finding the perfect gift for all my friends and family" and "It's the thought that counts." Such statements sound great, but the power of SDB suggests that such protestations are often balderdash. Shopping for the perfect present for an uncle who drives you crazy does not fill your heart with a warm glow. Neither does getting CDs from your grandma who's never even heard of iTunes, much less your favorite bands.

Once you grasp SDB, economists' case for cash presents starts to sound a lot more plausible. Yes, non-pecuniary preferences argue against cash; but SDB suggests that a lot of professed non-pecuniary "preferences" are, in fact, lies. Why don't these liars jointly agree to stop exchanging (non-cash) presents? SDB once again! The first person who proposes an End This Miserable Charade Treaty sounds like a jerk.

Does this mean that the pro-cash economists are right? Not quite. The pro-cash economists are correct to see - and courageous to point out - a lot of gifty inefficiency. But SDB is only a tendency, not a universal law. Some people some of the time really do feel the spirit of Christmas. When they do, traditional gift-giving is efficiency-enhancing.

When is this most likely? Two obvious factors:

1. How much affection the donor and recipient truly feel for each other. Your kids, your spouse, and your go-to friends are probably very dear to you. Your second cousins, your brother-in-law, and the co-workers you never see outside the office probably aren't so dear.

Corollary: Giving presents to kids tends to be more efficient because kids (a) inspire more affection than adults, and (b) exhibit less SDB than adults. If giving a child a toy makes you feel good, and the kid smiles when he gets it, you probably gifted efficiently.

2. The kind of person you happen to be. If your Five Factor personality test says you're high in Agreeableness and low in Neuroticism, you probably savor both giving and receiving gifts far more than people low in Agreeableness and high in Neuroticism. Christmas is fun for the former, pain for the latter.

In adage form: Exchange gifts with your close family and friends, especially kids - and leave your favorite Grinches in peace.

P.S. None of this applies if you're giving the gift of economic literacy to your entire family at holiday dinner. Giving and receiving economic enlightenment is always a joy for all people at all times. :-)

(9 COMMENTS)

1. Yes, because of the receiver's demonstrated preference. Suppose gift X costs $100. If you gave the receiver $100, would he still have spent the money on X? Almost certainly not, so he must prefer whatever he bought with the $100 to X.

2. No, because of the giver's demonstrated preference. Suppose gift X costs $100. The giver could have given $100 instead of X, but gave X instead. So he must prefer giving X to its cash equivalent.

When polled, economists on the IGM panel heavily favor some version of #2. Many even ridicule #1 as psychologically obtuse. Angus Deaton quips, "This is the sort of narrow view that rightly gives economics bad name." But neither side on the IGM even mentions a massive body of psychological research on Social Desirability Bias (SDB) that weighs heavily in #1's favor. Quick version: When lies sound better than the truth, human beings often lie.

Consider "I enjoy finding the perfect gift for all my friends and family" and "It's the thought that counts." Such statements sound great, but the power of SDB suggests that such protestations are often balderdash. Shopping for the perfect present for an uncle who drives you crazy does not fill your heart with a warm glow. Neither does getting CDs from your grandma who's never even heard of iTunes, much less your favorite bands.

Once you grasp SDB, economists' case for cash presents starts to sound a lot more plausible. Yes, non-pecuniary preferences argue against cash; but SDB suggests that a lot of professed non-pecuniary "preferences" are, in fact, lies. Why don't these liars jointly agree to stop exchanging (non-cash) presents? SDB once again! The first person who proposes an End This Miserable Charade Treaty sounds like a jerk.

Does this mean that the pro-cash economists are right? Not quite. The pro-cash economists are correct to see - and courageous to point out - a lot of gifty inefficiency. But SDB is only a tendency, not a universal law. Some people some of the time really do feel the spirit of Christmas. When they do, traditional gift-giving is efficiency-enhancing.

When is this most likely? Two obvious factors:

1. How much affection the donor and recipient truly feel for each other. Your kids, your spouse, and your go-to friends are probably very dear to you. Your second cousins, your brother-in-law, and the co-workers you never see outside the office probably aren't so dear.

Corollary: Giving presents to kids tends to be more efficient because kids (a) inspire more affection than adults, and (b) exhibit less SDB than adults. If giving a child a toy makes you feel good, and the kid smiles when he gets it, you probably gifted efficiently.

2. The kind of person you happen to be. If your Five Factor personality test says you're high in Agreeableness and low in Neuroticism, you probably savor both giving and receiving gifts far more than people low in Agreeableness and high in Neuroticism. Christmas is fun for the former, pain for the latter.

In adage form: Exchange gifts with your close family and friends, especially kids - and leave your favorite Grinches in peace.

P.S. None of this applies if you're giving the gift of economic literacy to your entire family at holiday dinner. Giving and receiving economic enlightenment is always a joy for all people at all times. :-)

(9 COMMENTS)

Published on December 27, 2013 08:15

December 23, 2013

Farewell to Bart Wilson, For Now, by Bryan Caplan

Guest blogger Bart Wilson is signing off, for now. He's been one of my favorite experimental economists for the last decade, and I've been pleased to see him bring his unique perspective to EconLog over the past month.

Out of all Bart's posts, "The Error of Utilitarian Behavioral Economics" is probably my favorite. If poor decision-making is as ubiquitous as behavioral economists claim, why isn't stickK.com as big as Facebook? Bart points to an experimental resolution: People like being in control of their own lives - and gladly accept lower-quality outcomes to avoid being under other people's thumbs. Thus, while behavioral economics is usually seen as pro-paternalism (or at least, in Cass Sunstein's words, "anti-anti-paternalism"), experiments reveal two offsetting behavioral effects.

First, people often make systematically bad decisions.

Second, people value their right to make their own decisions - even if they know their decisions are systematically bad.

Farewell, Bart. While it's sad to see you go, we can all hope you don't stay away from the blogosphere for long.

P.S. I hear Bart has one last post in the works.

(1 COMMENTS)

Out of all Bart's posts, "The Error of Utilitarian Behavioral Economics" is probably my favorite. If poor decision-making is as ubiquitous as behavioral economists claim, why isn't stickK.com as big as Facebook? Bart points to an experimental resolution: People like being in control of their own lives - and gladly accept lower-quality outcomes to avoid being under other people's thumbs. Thus, while behavioral economics is usually seen as pro-paternalism (or at least, in Cass Sunstein's words, "anti-anti-paternalism"), experiments reveal two offsetting behavioral effects.

First, people often make systematically bad decisions.

Second, people value their right to make their own decisions - even if they know their decisions are systematically bad.

Farewell, Bart. While it's sad to see you go, we can all hope you don't stay away from the blogosphere for long.

P.S. I hear Bart has one last post in the works.

(1 COMMENTS)

Published on December 23, 2013 21:06

December 22, 2013

How to Work in France, by Bryan Caplan

From the Christmas newsletter of a good friend of mine who just got a post-doc in France. Reprinted with his permission. Names omitted to hinder bureaucratic retaliation.

In early March I got accepted for a position in [city redacted] France, and regardless of any considerations of career path and so forth, that was that; when life offers you the opportunity to live in the south of France, you do not say no. But many things made the transition to France a slow one. First, of course, I needed to finish my thesis and pass my defense. Then I needed to convince France to let me in, which required navigating a long and complex bureaucratic process. One example: I had to show France proof that I had completed my PhD, but [school redacted] was not willing to certify that until after their Fall Convocation... almost six months after my defense! That caused all sorts of stress. Another example: to get an apartment in France, you need to show proof that you have a French bank account, but to get a French bank account, you have to show proof of a permanent address in France. Cracking that Catch-22 was rather tricky. And a final example: since we were then residents of New York, the only place on the face on the Earth where we could apply for our French visas was the French consulate in New York City. In person. That this might be inconvenient does not, of course, bother the bureaucrats. In fact, after they process your visa application, which takes an unpredictable amount of time, you are supposed to pick it up in NYC, again in person. I came prepared with a pre-paid FedEx envelope, and asked if they could send our passports back to us using it, but they said no. In fact what they actually said was this: we don't provide that service, because too many people would want it. Rarely is the worldview of the bureaucrat stated so bluntly!

We're still not finished with the bureaucracy; it continued even after we arrived in France. I carry a folder with me that has copies of our passports and visas, our birth certificates, our marriage certificate, our rental agreement, my employment contract, my bank information, my vaccination records... you never know what paperwork a French bureaucrat is going to ask for, so it is best to be prepared for any eventuality. We have certified translations into French of many of these documents, up to and including my N.Y. driver's license. In order to open our bank account, we had to show proof that we had renter's insurance; why, none can say. Soon it will be time to begin on the bureaucracy for the renewal of our visas.

[...]

Because of the Catch-22 I mentioned before, we started in a vacation rental, which is ridiculously large for two people, and even more ridiculously expensive (and it was hard to convince them to write a long-term lease for us, too!). Now that we've got our bank account and renter's insurance and all of that, we can move to a proper apartment, and we plan to do so at the beginning of May.

(15 COMMENTS)

In early March I got accepted for a position in [city redacted] France, and regardless of any considerations of career path and so forth, that was that; when life offers you the opportunity to live in the south of France, you do not say no. But many things made the transition to France a slow one. First, of course, I needed to finish my thesis and pass my defense. Then I needed to convince France to let me in, which required navigating a long and complex bureaucratic process. One example: I had to show France proof that I had completed my PhD, but [school redacted] was not willing to certify that until after their Fall Convocation... almost six months after my defense! That caused all sorts of stress. Another example: to get an apartment in France, you need to show proof that you have a French bank account, but to get a French bank account, you have to show proof of a permanent address in France. Cracking that Catch-22 was rather tricky. And a final example: since we were then residents of New York, the only place on the face on the Earth where we could apply for our French visas was the French consulate in New York City. In person. That this might be inconvenient does not, of course, bother the bureaucrats. In fact, after they process your visa application, which takes an unpredictable amount of time, you are supposed to pick it up in NYC, again in person. I came prepared with a pre-paid FedEx envelope, and asked if they could send our passports back to us using it, but they said no. In fact what they actually said was this: we don't provide that service, because too many people would want it. Rarely is the worldview of the bureaucrat stated so bluntly!

We're still not finished with the bureaucracy; it continued even after we arrived in France. I carry a folder with me that has copies of our passports and visas, our birth certificates, our marriage certificate, our rental agreement, my employment contract, my bank information, my vaccination records... you never know what paperwork a French bureaucrat is going to ask for, so it is best to be prepared for any eventuality. We have certified translations into French of many of these documents, up to and including my N.Y. driver's license. In order to open our bank account, we had to show proof that we had renter's insurance; why, none can say. Soon it will be time to begin on the bureaucracy for the renewal of our visas.

[...]

Because of the Catch-22 I mentioned before, we started in a vacation rental, which is ridiculously large for two people, and even more ridiculously expensive (and it was hard to convince them to write a long-term lease for us, too!). Now that we've got our bank account and renter's insurance and all of that, we can move to a proper apartment, and we plan to do so at the beginning of May.

(15 COMMENTS)

Published on December 22, 2013 21:16

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers

Bryan Caplan isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.