Bryan Caplan's Blog, page 159

December 20, 2013

Some Explanations for the Curious Absence of Socially Conservative Economics, by Bryan Caplan

1. There's more socially conservative economics than meets the eye.

The first is that social conservatives actually do make such2. Belief in homo economicus conflicts with religious conviction.

arguments, even if the phrase "negative externalities" isn't deployed

with quite the frequency Caplan would like... Indeed, the entire corpus of

socially-conservative intellectual efforts, from 1970s-era

neoconservatives like Richard John Neuhaus and James Q. Wilson down to

the present era, is shot through with arguments that are, if not purely

economic, at least heavily informed by economic questions.

But note that very few of the writers and intellectuals I've just3. Academic stigma.

mentioned are practicing economists: They're political scientists,

sociologists, journalists, and so forth... So maybe the question is, why don't social

conservatives become economists? Probably it has something to

do with their frequent religio-philosophical commitments: Social

conservatives are not uniformly religious, but they tend to be

religion-friendly in ways that make an uneasy fit with the homo economicus assumptions that undergird so much of the work of the economics profession, left and right.

The simplest explanation for "the curious absence of sociallyAll good points, but Ross' response makes me realize that I should have given the original puzzle more context. The absence of socially conservative economics is odd because - unlike all the other disciplines Ross names - economics has intellectual rules that weigh heavily in social conservatives' favor - especially textbook analysis of economic efficiency.

conservative economics" the same reason that there aren't many social

conservatives in any academic field: Because social conservatism is

considered uniquely socially disreputable in elite culture, in

ways that libertarianism and economic conservatism are not. (A thousand

conversations: "Are you a Republican?" "Yes, but socially liberal,

fiscally conservative, don't worry!")

Efficiency analysis rejects the view that policy decisions are merely a matter of distribution - of who gets their way and who doesn't. Instead, efficiency analysis insists that - distribution aside - some outcomes are more efficient than others. How do economists measure efficiency? Simple: They count anything that anyone is willing to pay for.

Take illegal drugs. Efficiency analysis tells us to estimate the willingness to pay of everyone who gives a damn one way or the other. So in addition to the preferences of potential users, we must - at minimum - count the preferences of potential users' parents. If your parents' willingness to pay to stop you from using drugs exceeds your willingness to pay to use drugs, it is inefficient for you to get your way.

Non-economists could of course simply reject efficiency as the supreme normative standard. That's what I do. But most economists are very reluctant to explicitly adopt any other normative standard. This in gives social conservatives a great intellectual opportunity: Economics is a high-status academic game with established rules that genuinely allow social conservatives to win. Hence my puzzlement for the absence of socially conservative economics.

(10 COMMENTS)

December 18, 2013

What Are Cowenian Rights?, by Bryan Caplan

The reality is that when it comes to the future,Consider this a nudge to Tyler to spell out his actual view.

we can "see around the corner" only to a limited degree. The upshot is

that the rights of the individual -- when applicable -- should remain paramount,

and no I don't mean Caplanian libertarian rights. You can only rarely be

sure you will get such a great gain from violating rights, so why not do the

right thing instead? Science fiction inhabits the realm of fiction precisely because the building of

grand scenarios is denied to us, for the most part.

(8 COMMENTS)

How Big of a Deal Is Social Security?, by Bryan Caplan

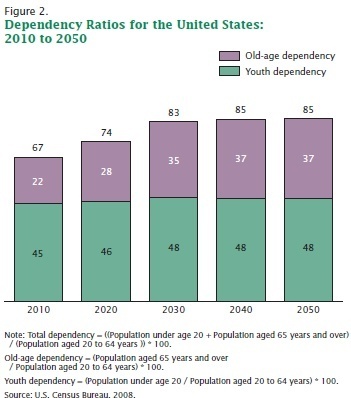

Social Security never was that big of deal. Lots of people get this and I'll just refer you to them.The issue, of course, is not whether the government can make Social Security solvent: lower benefits, higher taxes, or means-testing would all do the trick. The issue, rather, is how big these adjustments would have to be. And that, in turn, depends on how much the Aged Dependency Ratio will rise - the ratio of retirees to the working-age population. From the standard Census projection:

To my eyes, the basic numbers show that Social Security is, contrary to Karl, an enormous deal. Between 2010 and 2030, the Aged Dependency Ratio will rise 59%. Then it roughly stabilizes for the next two decades. Social Security has been in deficit since 2010, so without extremely unpopular cuts - or means-testing - fiscal balance will require combined Social Security tax rates to rise from 12.4% to about 20%. And that's heroically assuming no disincentive effects of the tax hike.

Needless to say, such a tax hike wouldn't make our heads explode. We'd live. But without major changes (by American standards), there will be a major fiscal crisis. The longer the U.S. delays, the worse the crisis will be when it arrives. And there is every reason to think that the U.S. political system will delay, delay, and delay again.

(11 COMMENTS)

December 16, 2013

The Curious Absence of Socially Conservative Economics, by Bryan Caplan

This is a classic "dog that didn't bark" situation. What can we learn from conservative economics' failure to launch?

For starters, note that social conservatism is now the main source of intellectual conflict between libertarians and conservatives. The simplest explanation for the absence of socially conservative economics, then, is that economics doesn't provide any plausible arguments in favor of social conservatism.

But the simplest explanation has an obvious problem: Rationalizing social conservatism using Econ 101 is child's play. Just close your eyes, tap your heels three times, and say "Negative externalities." So-called "self-regarding behavior" clearly impacts your family - yet many people fail to take the interests of their family members into account when they engage in risky behavior. Think about how many people would drastically curtail their use of alcohol, illegal drugs, and casual sex if they deeply cared about their parents' feelings.

Also note that familial love often makes bargaining and punishment ineffective. Most people's parents quickly forgive their kids' broken promises - not to mention their heinous offenses. So why not use government to pick up the slack - to enforce the "family values" that the family itself is so often impotent to enforce?

Once government starts enforcing family values in the interests of intra-family harmony, it's easy to make parallel arguments at the level of the neighborhood, the region, the state, the country, and the world. If your "self-regarding behavior" can hurt your family members, it can other hurt your neighbors, fellow citizens, and humanity itself.

This remains true, by the way, when your fellow citizens have no decent argument for their view. In economic terms, widespread distaste for, say, gay marriage can have a massive social cost even if the only negative side effect of gay marriage is strangers' unreasoning disgust.

Normatively, of course, I am not a social conservative. But in purely economic terms, the case for socially conservative economics is surprisingly strong. The main reason I feel little need to critique economic arguments for social conservatism, in all honesty, is that almost no social conservative bothers to make the arguments. My question: Why don't they?

(31 COMMENTS)

December 15, 2013

Crusade, Denial, or Concerned Tolerance?: The Case of MSM and HIV, by Bryan Caplan

Reaction #1: Crusade. Guns cause suicides, suicides are bad, so guns must be banned. Anyone who disagrees is anti-science.

Reaction #2: Denial. Guns mustn't be banned, so either guns don't cause suicides, or suicides aren't bad.

The wise reaction, though, is what I call Concerned Tolerance.

Reaction #3: Concerned Tolerance. Guns cause suicides, and suicides are bad. But despite this risk, guns also have major upsides. Self-defense aside, shooting and hunting are two popular American hobbies. It's far from clear that the suicide risk outweighs these benefits. But perhaps gun-owners underestimate this risk. So let's politely publicize the Briggs-Tabarrok findings, then let individuals make their own choice. In many cases, informed individuals will take extra precautions (e.g. locking up their guns) rather than actual quitting their risky behavior.

Concerned Tolerance may seem like mere libertarian dogma, but the truth is that most non-libertarians rely on Concerned Tolerance most of the time - even for choices that are vastly riskier than gun ownership.

Like what? Consider male-on-male sex. It clearly raises your probability of dying from HIV. By how much? This impressive study by Susan Cochran and Vickie Mays (American Journal of Public Health, 2011) estimates the probability that men who have sex with men (MSM) will die of HIV-related causes. Since it is based on past deaths, it is quite possible that the risk has changed. But it's the best piece I could find on the topic, and you've got to start somewhere.

The sample:

We used data from a retrospective cohort of 5574 men aged 17 to 59The risk estimate:

years, first interviewed in the National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey III (NHANES III; 1988-1994) and then followed for

mortality status up to 18 years later. We classified men into 3 groups:

those reporting (1) any same-sex sexual partners (men who have sex with

men [MSM]; n = 85), (2) only female sexual partners (n = 5292), and (3)

no sexual partners (n = 197). Groups were then compared for all-cause

mortality, HIV-related mortality, suicide-related mortality, and

non-HIV-related mortality.

Compared with heterosexual men, MSM evidenced greater all-causeOf course, some MSM would have died of other causes during the sample period even if they never contracted HIV. But very few. If you assume that HIV-positive men would have died of other causes at the normal rate (6.6%), this still means that being an MSM raises your probability of HIV-related death by 12 percentage-points.

mortality. Approximately 13% of MSM died from HIV-related causes

compared with 0.1% of men reporting only female partners. However,

mortality risk from non-HIV-related causes, including suicide, was not

elevated among MSM.

Converting that figure into an annual estimate (12 extra percentage points over 18 years) implies a .63 percentage-point increase in the annual risk of death by HIV. That is an staggering risk. By way of comparison, Briggs and Tabarrok found that People Living in Households with Guns (PLHG) had .01 percentage-point increase in their annual risk of death by suicide. Thus, the risk of dying of HIV because you're an MSM is about 60 times greater than the risk of dying of suicide because you're a PLHG. If another research design found that Cochran-Mays overestimated by a factor of ten, the Cochran-Mays effect would still be over six times as large as the Briggs-Tabarrok

effect.

How should we react to Cochran-Mays' risk estimate? As usual, we've got three basic options: Crusade, Denial, or Concerned Tolerance.

Reaction #1: Crusade. Male-on-male sex is very dangerous, so let's pass and enforce draconian laws against it. Anyone who disagrees is anti-science.

Reaction #2: Denial. Male-on-male sex isn't dangerous. Cochran-Mays must be incompetent and/or liars. Or maybe male-on-male sex is dangerous, but people wouldn't engage in it unless the benefits outweighed the costs, so there's no need to study or publicize the risk.

Reaction #3: Concerned Tolerance. Male-on-male sex is very dangerous, and people could easily underestimate its risks. But despite this risk, male-on-male sex has major upsides. Some guys really love it; some would feel spiritually incomplete if they quit. So despite the massive risk of being an MSM, it's

far from clear that this risk outweighs these benefits. But

perhaps MSM underestimate the riskiness of their behavior. So let's politely publicize

the Cochran-Mays findings, then let individuals make their own

choice. In many cases, informed individuals will take extra precautions

(e.g. having fewer sexual partners) rather

than actual quitting their risky behavior.

As far as I can tell, the vast majority of modern Americans take a Concerned Tolerance approach to MSM. If they're right to do so here, why not across the board?

P.S. Please don't protest that "Sexual orientation is not a choice." I'm talking about sexual behavior, not orientation.

(0 COMMENTS)

December 13, 2013

Labor Economists vs. Signaling, by Bryan Caplan

Signaling has been one of economists' more successful intellectual

exports. After Spence and Arrow developed

the signaling model of education in the 1970s, the idea soon spread to

sociology, psychology, and education research.

While few experts are staunch converts, most grant that the idea is

plausible and the evidence suggestive. Yet

strangely, there is one body of experts that sees little or no merit in the

signaling model: labor economists, particularly those who specialize in

education.

In modern labor economics, human capital theory reigns

supreme. Most specialists see signaling

as an irrelevant distraction. Very few

would endorse anything approaching a 20/80 split in signaling's favor. A high-profile chapter in the Handbook of the Economics of Education

fairly represents labor economists' consensus: "Our review of the available

empirical evidence on Job Market Signaling leads us to conclude that there is

little in the data that supports Job Market Signaling as an explanation for the

observed returns to education."

This is a disquieting intellectual development. Economists have plenty of blind spots, but

they spend years studying economic

theory. So you would expect labor

economists to have a crisp grasp of the signaling model. Who else would better understand what

signaling predicts - or whether those predictions are correct? Yet after forty years of research, the

experts most-qualified to judge the signaling model turn out to be the

least-persuaded. If I denied I was

disturbed by labor economists' disdain, I'd be lying. If they're right, I'm wrong.

Where precisely do I part company from mainstream labor

economics? For the most part, I accept

their empirical evidence - especially when they rely on standard, transparent

statistical methods. My claim is that

mainstream labor economists have an interpretive double standard. When their evidence supports the human

capital model, they take the evidence at face value. When their evidence supports the signaling

model, they wrack their brains to avoid giving signaling an iota of credit.

Consider the sheepskin effect. Almost everyone senses that big payoffs for

graduation support signaling and undermine human capital. As long as the rewards for degree completion

were in doubt, labor economists took the sheepskin-signaling link for granted. Once evidence of large sheepskin effects

became undeniable, however, labor economists moved the goal posts. In theory, the sheepskin effect could stem purely from selection; maybe

students who finish their degrees would have been equally well-paid if they'd

dropped out a day before graduation.

Sure, the sheepskin effect survives standard ability corrections

unscatched. But human capital purists

can demur, "You didn't correct for weird not-yet-measured abilities." If labor economists consistently enforced

this unmeetable burden of proof, their field would vanish.

Or take the cross-national evidence. Signaling predicts that education will be

more lucrative for individuals than for countries. This is precisely what researchers typically

find. Yet few labor economists even

grudgingly admit, "Signaling wins this round."

Instead, they rush to figure out how they've erred. Maybe better data or fancier statistical

methods would help. No? Then the question's beyond us. Move along, nothing to see here. My point is not that the cross-national

evidence is strong enough to settle the human capital/signaling debate. All I'm saying is that if the evidence

supported human capital purism, labor economists would have spent less time

second-guessing the results and more time dancing on signaling's grave.

Labor economists don't merely misinterpret their own

evidence. They also ignore everyone else's evidence. Psychology, education, and sociology all have

useful insight for the human capital/signaling debate, but labor economists

rarely read their research - or even acknowledge its existence. It's classic Not Invented Here

Syndrome.

Case in point: Human capital says that education raises

income by imparting useful skills; signaling says education raises income without

imparting useful skills. To weigh the

two theories, then, you must investigate

what students actually learn and retain.

Psychologists and education researchers are clearly the go-to experts on

these matters. Yet labor economists

almost never go to these go-to experts.

If they did, they would hear lurid tales of a yawning chasm between learning

and earning - precisely as signaling predicts.

Labor economists' root problem, at risk of being

uncharitable, is that they fall in love with education years before they study

the evidence. When they meet human

capital theory, they're instant converts.

It tells them what they want to hear: Two things they love - education

and prosperity - go hand-in-hand. When

budding labor economists discover signaling, they rush to reject to it. Most latch on to one of the flimsy "signaling

doesn't make sense" arguments from chapter 1 - "Employers would just do IQ

tests instead," "You can't fool employers for long," "There's got to be a

cheaper way." By the time they examine

the scholarly research, it's hard for labor economists to give signaling a fair

shake.

To be fair, however, personal experience would cloud labor

economists' judgment even if love of education did not. Why?

Because the link between what academics learn in school and what academics

do on the job is eerily close. I call it

"intellectual incest." We sit in class,

learn some material, then get jobs teaching the very material we studied. Professors can even "acquire human capital"

by recycling our old professors' lecture notes!

The upshot: When academics reflect on our own lives, school almost

automatically seems "relevant." To see

the labor market clearly, professors would have to contemplate the alien career

paths of the vast majority students who never enter academia.

When I argue with mainstream labor economists, they grow

frustrated. "Is everything signaling? I have

trouble believing that workers can't find a cheaper way to certify their

quality," they ask. I'm tempted to

sarcastically reply, "Is everything human

capital? I have trouble believing that

studying Latin makes you a better banker."

My constructive answer, however, is: Of course everything

isn't signaling. Students definitely

learn useful job skills. School lasts

over a decade. It would be amazing if

students didn't learn something

useful before they left. My claim, as I keep

repeating, is that education is mostly

signaling. Given all the evidence, a

20/80 human capital/signaling split seems reasonable. I'm happy to debate the exact figure. Until labor economists renounce human capital

purism, though, I cannot take them seriously - and neither should anyone else.

Lange, Fabian, and Robert Topel. 2006.

"The Social Value of Education and Human Capital." In Hanushek, Eric, and Finis Welch, eds. Handbook

of the Economics of Education.

Amsterdam: North-Holland, p.505.

See list of references on Lange and Topel, p.493.

Lange and Topel, pp.492-495, is probably the

best-developed example of this denialism.

After conceding that, "The existence of diploma effects ranks among the

most persistent empirical findings in labor economics," they claim, "Those

least capable to profit from schooling drop out before the completion of degree

years." Lange and Topel then provide a

careful theoretical model of their story, but no zero empirical evidence.

(4 COMMENTS)

December 11, 2013

A Fortune Cookie for Ron Unz, by Bryan Caplan

Every atheist should read the Bible cover to cover - and every critic of economics should read Mankiw cover to cover.

(0 COMMENTS)

December 10, 2013

Ambition, by Bryan Caplan

Background: Labor economists routinely find that degrees from more selective colleges raise income more than degrees from less selective colleges. D&K replicate this result using standard control variables: your SAT score, high school GPA, etc. But then D&K add controls for (a) the average SAT of the schools you applied to, and (b) the number of applications you submitted. After adding these controls, the selectivity premium actually vanishes. In their latest paper, this is true if you measure selectivity by (a) your college's average SAT, (b) your college's net tuition, or (c) your college's Barron's Index.

D&K conclude that the selectivity premium is probably greatly exaggerated, at least on average. But I draw a much bigger lesson: D&K have (a) proposed very plausible measures of what we intuitively call "ambition," and (b) shown that ambition so measured has a huge effect on income. As far as I can tell, D&K's measures are much stronger than the other measures of "non-cognitive ability" (especially the NLSY's Locus of Control and Self-Esteem scores) that economists have been toying with over the last decade.

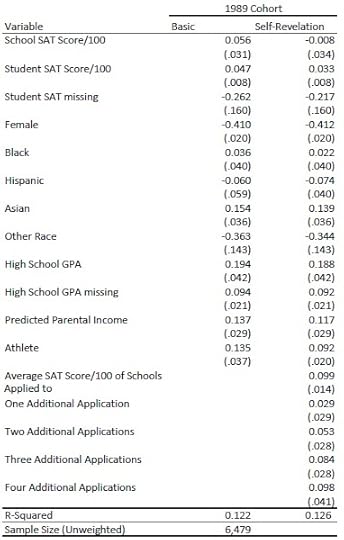

Here are D&K's log income results for their 1989 cohort. The "Basic" results don't control for their measures of ambition; the "Self-Revelation" results do.

D&K focus on the fact that, after controlling for ambition, the premium for attending a school with an average SAT 100 points higher goes from +5.6% to -0.8%. What's truly remarkable, though, is the size of the ambition premium. Applying to schools with an average SAT 100 points higher has a +9.9% premium. Applying to four additional schools has a +9.8% premium. Notice, moreover, that the payoffs for SAT scores and high school GPA only moderately decline after controlling for ambition; Dale-Krueger's measures capture something fairly novel about a young adult's character.

This presumably doesn't mean, of course, that you can greatly increase your income by mailing out lots of Hail Mary applications. Instead, it means that having the ambition to apply to lots of good schools greatly increases income.

To be fair, Dale and Krueger explicitly state that they're trying to control for ambition. But they remain focused on connection between ambition and the selectivity premium. Given the strength of their results, though, they should be pushing for a complete overhaul of the return to education literature. What is the effect of a year of education on income... controlling for ambition? What is the effect of education on unemployment... controlling for ambition? What is the college major premium... controlling for ambition? What happens to the sheepskin effect... controlling for ambition? Inquiring minds want to know!

(3 COMMENTS)

December 8, 2013

Econ as Incredulity, by Bryan Caplan

Most economists openly embrace the latter position, but secretly believe the former. The smoking gun: The typical economist has well-defined views on a wide range of issues, even though he is only familiar with a handful of empirical literatures. If economists really believed their official methodological position, they'd be agnostic on the vast majority of topics. They aren't.

How can economists resolve this tension? Hard-line Austrian economists want the profession to renounce empiricism and admit that economic knowledge is a priori. The main problem with this position is that even claims as elementary as "supply slopes up" and "demand slopes down" are not a priori true. Hard-line empiricists want the profession to remain utterly open-minded on every economic issue until they've reviewed the empirical evidence. The main problem with this position is that almost everyone who absorbs the "economic way of thinking" finds it to be incredibly clarifying and insightful. A good economist really can talk more intelligently about many topics he's never specifically studied than most non-economists who work on those topics full-time.

But if the "economic way of thinking" isn't a body of truths, how can it provide such large epistemic benefits? My answer: Economics provides clarity and insight by instilling selective incredulity. A trained economist knows when to say, "What?!," "Really?!?!," and "How can that be?!"

A few examples:

1. Living standards during the Industrial Revolution. Pure economic theory can't prove that a massive increase in production will make most people richer. But when someone claims that the Industrial Revolution made most people worse off, the economic way of thinking teaches us to be incredulous. "Mass production failed to increase mass consumption? How is that possible?!"

2 Working conditions during the Industrial Revolution. Pure economic theory can't prove that the rise of the factory made workers better off. But when someone paints the Industrial Revolution as a disaster for workers, economics trains us to ask questions like, "People moved to cities to get worse jobs than they had in agriculture?!," "Immigrants wrongly believed they were likely to find a better life in the New World?," and "Employers got rich paying workers far less than they were worth - and failed to provoke new entry?!"

3. The minimum wage. Pure economic theory can't prove that the minimum wage causes unemployment. But when someone denies this effect, a well-trained economist asks "The price of labor goes up by 20% and employers buy just as much? Come on." Or, "Gee, why stop at $12 per hour? Why not $1000 per hour?"

4. Public goods. Pure economic theory can't prove that public goods are under-supplied. But when someone claims that we can solve massive social ills by asking for donations, the economic way of thinking kicks in. "People enjoy the same benefit whether or not they contribute, but they still contribute on a massive scale?"

Economists' incredulity should be surmountable. Faced with our incredulous questions, economists should be ready to hear those we challenge say, "Yes, really! I understand your skepticism, but a very careful study of the evidence yields a surprising answer." The point of the economic way of thinking is simply to set the terms of the debate - to separate "Ordinary claims requiring ordinary evidence," from "Extraordinary claims requiring extraordinary evidence."

Critics may call this dogmatic. But it's no more dogmatic than scoffing at Bigfoot sightings. The reasonable reaction to Bigfoot really is to ask, "A whole species of larger-than-man North American primates exists, but none of these animals has ever been captured, dead or alive?!" And the reasonable reaction to protectionism really is to ask, "So we'll be richer if we prevent foreigners from selling us cheap stuff?"

Update: Comments enabled.

(2 COMMENTS)

December 5, 2013

Phase-In: A Demagogic Theory of the Minimum Wage, by Bryan Caplan

...to $5.85 per hour 60 days after enactment (2007-07-24), to $6.55 perRon Unz's proposed increase, similarly, has two steps. In his own words:

hour 12 months after that (2008-07-24), and finally to $7.25 per hour 12

months after that (2009-07-24)...

The initiative is targeted for the November 2014 ballot. If it passedWhat's the point of these byzantine time tables? Why not just immediately impose the minimum wage you actually want? On the surface, the steps seem like an implicit admission that sharply and suddenly raising the minimum wage would have the negative disemployment effects emphasized by its critics. The point of the steps, then, is to turn a dangerously sharp and sudden hike into a harmlessly slow and gradual hike.

early in 2015, the minimum wage in California will go up to $10 an hour;

early in 2016 it would be raised to $12 an hour. In other words, the

initiative in a couple of stages would raise the minimum wage of all

California workers to $12 an hour.

On reflection, though, this argument makes very little sense. Giving people more time to adjust to incentives normally leads to larger adjustments, not smaller. If you suddenly raise the gas tax, for example, there is very little effect on gas consumption. But if people expect the gas tax to go up years before the higher tax kicks in, many will buy more fuel-efficient cars, leading to a large behavioral response. Minimum wage hikes should work the same way: Employers' long-run response should exceed their short-run response. If minimum wage advocates want to minimize the disemployment effect, they should remember the old adage about ripping off a Band-Aid: One sudden pull and you're done.

On reflection, though, there is another major difference between employers' response to sharp-and-sudden versus slow-and-gradual minimum wage hikes: visibility.

If the minimum wage unexpectedly jumped to $12 today, the effect on employment, though relatively small, would be blatant. Employers would wake up with a bunch of unprofitable workers on their hands. Over the next month or two, we would blame virtually all low-skilled lay-offs on the minimum wage hike - and we'd probably be right to do so.

If everyone knew the minimum wage was going to be $12 in 2015, however, even a large effect on employment could be virtually invisible. Employers wouldn't need to lay any workers off. They could get to their new optimum via reduced hiring and attrition. When the law finally kicked in, you might find zero extra layoffs, because employers saw the writing on the wall and quietly downsize their workforce in advance.

If you sincerely cared about workers' well-being, of course, it wouldn't make any difference whether the negative side effects of the minimum wage were blatant or subtle. You'd certainly prefer small but blatant job losses to large but subtle job losses.

But what if you're a ruthless demagogue, pandering to the public's economic illiteracy in a quest for power? Then you have a clear reason to prefer the subtle to the blatant. If you raise the minimum wage to $12 today and low-skilled unemployment doubles overnight, even the benighted masses might connect the dots. A gradual phase-in is a great insurance policy against a public relations disaster. As long as the minimum wage takes years to kick in, any half-competent demagogue can find dozens of appealing scapegoats for unemployment of low-skilled workers.

Most non-economists never even consider the possibility that the minimum wage could reduce employment. Before I studied economics, I was one of these oblivious non-economists. But if minimum wage activists were as clueless as the typical non-economist, they wouldn't bother with phase-in. They'd go full speed ahead. The fact that activists' proposals include phase-in provisions therefore suggests that for all their bluster, they know that negative effects on employment are a serious possibility. If they really cared about low-skilled workers, they'd struggle to figure out the magnitude of the effect. Instead, they cleverly make the disemployment effect of the minimum wage too gradual to detect.

(19 COMMENTS)

Bryan Caplan's Blog

- Bryan Caplan's profile

- 374 followers