Nate Silver's Blog, page 74

January 28, 2019

How President Trump Is Like A Terrible Poker Player

I was playing poker in Atlantic City this weekend, so I’ve had poker on the brain as I’ve been thinking about President Trump’s tactics during the partial government shutdown, which ended on Friday after Congress passed a three-week continuing resolution to fund the government. What will happen at the end of the next three weeks is very much up in the air. But the way Trump has played his hand so far on the shutdown has a lot in common with how bad poker players tend to cost themselves money.

If you read the headline of this post, you may have assumed that it refers to Trump’s getting outmaneuvered on the shutdown by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. I do think Trump was outmaneuvered by Pelosi, but the analogy to poker is a little different from that. It has more to do with Trump’s overall strategy toward the presidency.

In general, the strategic goal of poker is to put your opponent to tough decisions. If you see one of those hands on TV where one player is thinking for several minutes about whether to call or fold on the river, that usually means the other player has played his or her hand well, putting the opponent in a no-win position by leaving just the right amount of doubt about whether it’s a bluff or a real hand.

As a corollary, good players play in such a way as to avoid putting themselves to tough decisions. Bad players, conversely, tend to paint themselves into corners. They’ll curse their luck when they suddenly realize that a hand they’d assumed was a winner might be no good. But more often than not, it reflects a mistake they made earlier in the hand, such as playing a weak hand that they should have folded to begin with.

Sound familiar? It sounds a lot like Trump, who didn’t have a lot of good choices on the shutdown. He could have:

Caved to Pelosi and agreed to reopen the government without a border wall. But that would have risked undermining perceptions that Trump is a strong negotiator and leader and risked disappointing his base.

Maintained the shutdown. But that was getting more costly by the day for Trump, as his approval ratings got worse and more and more Americans blamed him for the shutdown — and as federal workers went without paychecks and the entire air traffic system was on the verge of chaos.

Struck a deal with Democrats. But because Democrats had all the leverage — the shutdown was hurting Trump a lot more than it was hurting them — it would have had to be a far more generous deal than the one that presidential adviser/son-in-law Jared Kushner had cooked up, generous enough that it would entail serious policy concessions and perhaps lead to a backlash from his base.

Declared a national emergency to build a border wall — an option that very much remains on the table. But that would likely be extremely unpopular, would create a precedent that a future Democratic president could exploit, might not be held up by the courts, and would trigger at least some objections from other Republican lawmakers and perhaps also from parts of the military.

I tend to agree with my colleague Perry Bacon Jr. that conceding to Pelosi was Trump’s least-worst option. In fact, I think Trump probably would have been better off just conceding on the border wall completely, instead of kicking the can down the road for three weeks. But I’m far from certain of that conclusion. The point is that all of Trump’s options stunk, and like in the case of a bad player who limped into the pot with 7-2 offsuit (the worst hand in poker) and then got caught up in a huge pot with a bad hand, it was 100 percent Trump’s fault.

Nor was the shutdown a case where things unexpectedly took a rough turn for Trump.

It’s been obvious the whole time that it was liable to end in political (if not also literal) disaster. Trump was an unpopular president using an unpopular technique to push for an unpopular policy, and he was doing it just after Republicans had lost 40 seats to Democrats in the midterm elections while Trump tried to scaremonger voters on immigration. I can certainly think of lapses in presidential judgment that were more consequential in hindsight than the shutdown, but not all that many that were so obvious in advance.

And this isn’t the first time that Trump and Republicans have gotten themselves in trouble by picking a fight over an unpopular policy. GOP efforts to undo Obamacare were similar to the shutdown, since Republicans risked either passing a massively unpopular repeal bill or breaking a promise they’d made to voters in 2016. The dynamics over the Republican tax bill were also similar in several respects. Republicans ultimately passed their bill in that case, but they paid a price for it in the midterms in congressional districts with high state, local and property taxes, which can no longer be deducted beyond $10,000 under the new law. Confirming Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court after he was accused of committing sexual assault when he was in high school, when Republicans could have withdrawn his name and chosen a less controversial nominee, is another case in which Republicans had to choose from among several difficult options.

Related:

Part of this is just a way of saying that public opinion does have consequences: Sometimes it prevents you from passing unpopular policies, and sometimes you pass them but suffer electorally. And sometimes, it’s both: Republicans didn’t get their full Obamacare repeal, but health care was a huge issue in the midterm campaign nonetheless.

If Trump doesn’t believe the polls showing himself and his policies, such as the border wall, to be unpopular, then maybe that’s part of the problem. (There are a lot of ways to be bad at poker, but probably the most common one is to play too many hands because you overestimate your own abilities.) This being FiveThirtyEight, I feel obligated to point out that the notion that polls systematically underestimate Trump is on shaky ground. But if Trump thinks polls are fake news and if he hires advisers who encourage that perception, that could explain why he constantly puts himself in such politically untenable positions.

There’s something else about those bad poker players that I think might apply to Trump.

Some of them (not all by any means) actually do have decent people-reading skills. They can sometimes suss out, through body language and table talk, whether your hand is relatively strong or relatively weak and make better decisions on that basis. It’s almost never enough to overcome poor strategic and technical play; poker is mostly a mathematical game. But those talents can help to stem losses, especially at lower stakes where opponents are more likely to exhibit tells. The bad players have their fair share of winning days when they’re catching cards.

Trump, similarly, has gotten a long way on the basis of hustle and luck — he was lucky in several important respects to be elected president. There are some cases in which he has displayed solid (if unconventional) tactical instincts, from his negotiations with foreign leaders to his handling of the media to his belittling of his primary opponents. That’s not to say he always gets these decisions right or even does so anywhere near approaching a majority of the time. But he gets enough “wins” — he became president of the United States! — to sustain his ego and not prompt a lot of self-reflection.

But Trump has no sense for which battles to pick and seemingly little awareness of his own unpopularity and the consequences it has for the presidency. Moreover, although Trump sometimes seems to realize when he has gotten himself into a no-win position, he doesn’t recognize how often his own decisions are responsible for putting him there. The presidency is a long game, and a much harder one than being a real-estate developer or a reality television host. The scary possibility for Trump — and I do mean merely a possibility — isn’t that the chaos of the shutdown, coming on the heels of the midterms and as the Russia investigation still looms over him, is a new low for him. It’s that it’s the new normal.

January 24, 2019

Our 2020 Democratic Primary Draft: Episode 2

Warren, Castro, Gillibrand, Harris, Buttigieg, Gabbard … the list goes on and on. The number of candidates trying to become the 2020 Democratic presidential nominee is growing every week, and it can be difficult to tell who really has a shot at winning. With that in mind, we are back with another round of our 2020 draft. For the first-timers here, the goal is to predict who we think has the best chance of winning the nomination. Some on our panel take that prompt more seriously than others.

This time around, our usual FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team (Clare, Galen, Micah and Nate) gathered to debate their picks.

You can watch this episode above, and our first episode here.

January 23, 2019

Is The Media Coverage Of The Mueller Investigation A Problem?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Last Thursday, BuzzFeed published a story alleging that President Trump directed Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal attorney, to lie on the president’s behalf to Congress about the Trump Tower project in Moscow. Special counsel Robert Mueller’s office later issued a rare statement in response, saying that “BuzzFeed’s description of specific statements to the special counsel’s office, and characterization of documents and testimony obtained by this office, regarding Michael Cohen’s congressional testimony are not accurate.” That sparked a debate around the reporting behind the story. So, my opening question to all of you is: What are the repercussions of stories like BuzzFeed’s? Does it risk jeopardizing the legitimacy of the Mueller investigation while also eroding trust in the media?

meghan (Meghan Ashford-Grooms, senior editor): Media outlets have interpreted the special counsel’s statement differently. The original story by BuzzFeed was sourced to “two federal law enforcement officials,” and The Washington Post has written an article, also based on anonymous sourcing, reporting that the special counsel’s statement was meant to be “a denial of the central theses of the BuzzFeed story.” BuzzFeed continues to say that the statement is nonspecific about what the special counsel’s office claims is inaccurate, and the outlet stands by its reporting.

It’s pretty messy!

There is a pattern there, though …

sarahf: Is the pattern “Don’t rely solely on anonymous sourcing”?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): It’s also messy because the special counsel’s office may have been under pressure from the White House to reject the reporting. Which is not to say the special counsel’s office wouldn’t have issued the statement if investigators didn’t believe it. Clearly, if there’s an element in the story that doesn’t match the narrative they’re trying to tell, and there are lots of reasons why they might not want that out there in the ether. I do think, though, that it’s not entirely clear what happened — so, yeah, maybe we should talk about generalities more than specifics.

meghan: That makes sense, Nate. The BuzzFeed reporters may have gotten it right!

We don’t know at this point, but this hullabaloo has raised a lot of issues for journalism that have been around for a while. The main issue for me is the scoop war that seems to be playing out among reporters trying to figure out what Mueller knows and what he’s concluding from his investigation into whether Trump’s campaign coordinated with Russian officials attempting to influence the 2016 election.

natesilver: To Sarah’s question about sourcing, I’m someone who’s pretty skeptical of the media’s reliance on anonymous sources. I don’t think you could report this particular story without anonymous sources. But I do feel like the bar isn’t high enough. When a story relies on anonymous sources, the publication bar needs to be especially high.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): I don’t mind scoop wars. I think it’s worth being precise about what we think is off here. My biggest concern about the Russia stories is the rush to break news that will come out on its own anyway.

Think about all of the coverage speculating about when the special counsel investigation will end or trying to guess when Rod Rosenstein will resign. The end of the investigation will be public. That resignation will be public. Those are not things that we need reporters to unearth.

meghan: There are so many of those.

sarahf: Yeah, and it seems like by trying to get the inside scoop before news breaks, reporters end up making a bigger mess of it.

natesilver: There have been quite a few screw-ups on Russia-related stories. Maybe four or five that I can think of, offhand.

Most of those were stories that painted Trump in an unfavorable light, but there was also the infamous New York Times “FBI Sees No Clear Link To Russia” story, which was a massive error in the other direction.

meghan: One of the biggest issues I have with anonymously sourced stories, especially when one is challenged: The public, experts and other reporters can’t evaluate how strong the reporting is if they don’t know where it came from.

Perry and Nate, I’m curious about why there might be more screw-ups on this topic. Is it because the special counsel isn’t providing much information? And so reporters have to go digging?

natesilver: I think it’s partly because the special counsel’s office has been so circumspect in what they do reveal to the public, yeah.

But I also think it’s because there are probably pro- and anti-Trump factions within the Justice Department.

That was sort of the Times’s explanation for the “no clear link” story: The Trump folks in the FBI were selling this framing to us, and maybe we were too uncritical in buying it, although there was a grain of truth to it.

So you wonder, if the BuzzFeed story was wrong, was that because there were anti-Trump parts of the U.S. attorney’s office that were getting out over their skis on the story? Or, alternatively, were there pro-Trump forces who were deliberately trying to spin a false story to undermine trust in the press?

meghan: That’s really interesting, Nate, and suggests that knowing who is talking would be super valuable for readers. But, of course, finding a balance is tough. Most of those stories wouldn’t be published if anonymity weren’t granted. But I would then ask whether all of those stories are necessary.

sarahf: And that’s where we’re currently at with the BuzzFeed story? It could be that BuzzFeed did get it right, but the problem is that we don’t know and we won’t know for a while.

Which raises the question, then, of why rush to break this particular story?

perry: I think there are a few explanations for the mistakes in Russia stories specifically: 1) There are a lot of people competing on this story, so getting a scoop is hard and requires you to be aggressive, perhaps too aggressive. 2) The special counsel’s office is basically unwilling to confirm or deny most stories. 3) There are many different kinds of sources who are trying to play the media to their advantage here — the attorneys of the various players, the various factions at the Justice Department, congressional Democrats, the White House, etc.

sarahf: Perry’s third point is an interesting one that doesn’t seem to be talked about much in coverage of the investigation — this idea that maybe Michael Cohen and others aren’t necessarily the most credible sources? Or, at the very least, should be treated more skeptically because they’re motivated to portray their involvement in a certain light.

perry: Like, it’s clear to me that Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani is an unnamed source for many of these stories. And while he might have some information, he’s also obviously an interested party.

meghan: I did not realize that, Perry! And that’s one of the things that I don’t think most readers would understand either.

natesilver: BuzzFeed’s Ben Smith is a pretty interesting editor. He’s both a traditionalist in some ways (coming from the NYC tabloid world) and a bit radical in others, including on issues around transparency. For example, BuzzFeed was the publication that actually released the Steele dossier.

So one thing that’s disappointed me a little is that they haven’t been more transparent about their reporting process now that it’s been called into question.

(I should say here that I’m friends with Jonah Peretti, who is the CEO of BuzzFeed. I also know and like Ben.)

perry: I assume the universe of potential sources here is quite small. So being transparent is probably hard without getting people fired.

natesilver: But, hypothetically, if a source deliberately told BuzzFeed a tall tale, shouldn’t the source be outed?

To me, the story is that BuzzFeed claimed that Cohen was “directed” by Trump to lie to Congress and that there’s various evidence for this that will come to light. That’s the whole claim. The rest of it isn’t particularly new or interesting.

meghan: I learned a lot more about the BuzzFeed story from watching Smith and reporter Anthony Cormier talk about it on CNN over the weekend. One thing that really struck me about the sourcing was that Smith and Cormier seemed genuinely not to know anything more about the allegation that they reported other than that Trump “directed” Cohen to lie. Meaning: When CNN host Brian Stelter pushed them to clarify what “directed” meant, they said they didn’t know exactly what Trump might have said to Cohen about his testimony. This surprised me.

natesilver: So if you have two sources who swear up and down that this happened and you see those sources as credible, is that enough to publish?

meghan: For BuzzFeed, yes — although Smith and Cormier sidestepped questions about whether they had other sourcing for the story.

But I think that’s a tough question to answer without knowing … drumroll … who the sources are!

perry: The issue with this Cohen story is that no one could confirm BuzzFeed’s reporting, but it was still picked up throughout the media and given major billing. The amplification of a story like this is hugely important — I’m guessing more people heard about it on CNN or MSNBC or through other news outlets than those who read about it on the BuzzFeed website. I think basically every site, including us, does a fair amount of “x happened, according to x outlet.”

But maybe we should be more careful about that?

meghan: I totally agree, Perry. This is one aspect of the scoop war that feels different to me this time around: Stories pop up everywhere so quickly. And I think we should be more careful about that kind of amplification — because when news outlets talk about stories they haven’t confirmed themselves, wrong stories are spread much further and faster than they otherwise would.

sarahf: So maybe that’s the problem here. Getting a “scoop” doesn’t really work all that well when covering the Mueller investigation. It seems to risk undermining both the work of the investigation and the credibility of the journalists?

And maybe more importantly, it doesn’t actually help readers understand what the hell is going on?

natesilver: Yeah, I do think trying to single BuzzFeed out, or making it some kind of proxy war in the battle of traditional journalism vs. the internet (as this column by The New York Times’s Jim Rutenberg tries to do, for example), is dumb.

Lots of traditional news outlets, including The New York Times, have fucked Russia stories up.

perry: I think it depends a lot on the scoop. “The investigation will end on X day” is not that useful. Mueller will announce when the investigation is over. But here is a very useful Russia story based on unnamed sources. (It’s a piece that says, according to current and former administration officials, Trump has concealed details of his one-on-one conversations with Putin. That seems very important, both in terms of the Russia investigation, but also in terms of broader issues of U.S. foreign policy. And Trump was not likely to announce himself that he was concealing info from those meetings.)

natesilver: With that said, I do wonder as a reader, or even more so as a journalist who’s covering the political reaction to the story, how you’re supposed to assess the credibility of an anonymously sourced story.

I’ll put it like this: I’d certainly give more weight to something published in The New York Times or The Washington Post than something in any other publication that isn’t one of those two.

perry: One of the main ways I try to assess whether to trust anonymous sourcing is to look at the outlet, the reporter and whether the event happened in the past or is happening in the future (the future is hard to predict). I also look to see if other outlets would be able to corroborate the story.

And the BuzzFeed story had some of the things that make me inclined to trust a story — it was reporting on something that, if it happened, happened in the past, and something that other outlets may at some point be able to corroborate, plus BuzzFeed has broken big news before.

meghan: Having a low bar for anonymously sourced stories can create problems for the media, but I’m not sure it’s specific to the Mueller investigation. I think I’m more conservative on this question than other people: I take with a grain of salt most stories that are based on only anonymous reporting.

natesilver: Yeah, I think that’s basically right, Meghan. Also, one of the reporters on the BuzzFeed story, Jason Leopold, has had a history of stories that didn’t pan out. People were bringing up Leopold’s history on Twitter and I saw a lot of journalists defending him … “Oh, that was a long time ago, he’s been on very solid ground lately.” But precisely because the bar should be so high for anonymously sourced stories, maybe even a single instance of having majorly screwed up a story, even if it was 10 years ago, ought to pretty heavily weigh against someone.

meghan: I think this journalistic track record question is the most tricky thing in all of the responses to the BuzzFeed article.

As Perry said earlier, reporters are not perfect. And editing systems are never completely foolproof. But the internet means that mistakes never go away, so reporters who’ve had problems in the past should expect to see those reputation issues dragged up again and again if they continue to get in tough spots, especially if they work on important stories, like those about the special counsel’s investigation.

natesilver: As Rutenberg mentioned in his column (even though it actually contradicts his thesis!), even Woodward and Bernstein had a couple of medium-sized screw-ups.

perry: If I had written a story last Thursday saying that Kamala Harris was announcing her presidential run on Martin Luther King Day, according to two unnamed sources close to her campaign, would you really dispute that reporting?

I’m a generally reliable reporter on politics with some access to Harris’s team thanks to my previous work. You could rely on that kind of story with unnamed sources, right?

I’m just trying to draw us out here — are we opposed to all unnamed sources or just opposed to them in certain kinds of stories?

natesilver: But Perry … I guess I’d say the problem is sort of the reliance on anonymity, multiplied by the magnitude of the story.

Kamala Harris declaring she’ll run for president isn’t nothing, but it’s also not the president allegedly committing an impeachable offense.

perry: Yeah, that is what I was getting at, I don’t really care if unnamed sources are used for stories that are kind of routine, where the stakes are low.

natesilver: I mean, if the stories are routine, I guess one could ask why you need anonymous sources in the first place?

The Harris-declaring thing is maybe a weird exception because it was sort of an open secret.

meghan: I definitely don’t think editors should be so quick to greenlight anonymous sourcing in garden-variety types of articles.

perry: I think what I’m getting at is that some common sourcing practices on everyday politics stories are just bad. And maybe now we’re seeing this extended to a story where those kind of bad practices can cause real damage?

meghan: Totally.

natesilver: The other thing about the Mueller investigation is that the time frame is so long. If Harris hadn’t declared for president on Monday … well, people would have known right away that the stories that predicted she would were wrong and could react accordingly.

With the Mueller-Russia stuff, we’re going to have to wait months or years to know who’s right, if we ever do.

meghan: I also think reporters and editors are frustrated by the notion that whatever Mueller finds out won’t necessarily be made public. So the search for what he knows feels very IMPORTANT.

sarahf: What is the damage we think is caused by all this, though?

natesilver: In the long run — whatever Mueller finds, Trump and Giuliani are probably going to try to kick up a cloud of dust around it.

And that could include emphasizing false claims made about the investigation, or claims that didn’t live up to their billing, or stuff the media got wrong.

sarahf: And you think stories like this give them ammunition?

natesilver: For sure, yeah.

perry: So, as a journalist, I think the damage is not that the “fake news” crowd gets more ammunition. It’s that regular people — who are not necessarily predisposed to be anti-media — see journalists mess up and distrust us as a result.

Also, I think these screw-ups breed broader confusion. I’m a professional journalist covering the political fallout from the Russia investigation, and I am still confused about some elements of the story. That’s in part because many of the Russia stories that rely heavily on unnamed sources are also written opaquely and seem aimed more at showing that reporters have access to big sources rather than clarifying what is going on for the readers.

meghan: I think the media credibility impact is very important, but I also think the damage that can be caused by lazy sourcing practices is simply that wrong information can get out into the public, possibly on a topic that really matters, either because reporters get used by their sources or because the sources are wrong.

natesilver: Another thing that’s been a little … disappointing … is that in all the pushback I’ve seen against the BuzzFeed story, very little of it has been focused around anonymous sourcing.

Everyone is so dependent on it that they don’t want to call it out, I guess.

meghan: Yep.

perry: CNN, for example, can’t criticize unnamed sources in the Russia investigation because they’ve usually talked to them, too.

meghan: One of things that’s tough, because so many stories are written breathlessly and based on anonymous sourcing, is figuring out what’s important and what isn’t.

perry: That’s my biggest concern — the Russia story is very confusing to many readers, I think.

meghan: And it’s worse when outlets are reporting the same story differently!

perry: It is a complicated story, but I also think you have outlets more interested in scoops than clarity.

natesilver: But I think we need to evaluate the claim that the Russia stories are an example of left-wing bias or at least anti-Trump bias.

meghan: I think the answer is “yes,” Nate. My sense is that many journalists covering this story consider themselves part of a race to be the next Woodward and Bernstein — i.e., to take down the president.

perry: I don’t know. I think we would see some of the same excesses if a Democratic president were involved in a big scandal. Imagine if the Monica Lewinsky scandal happened today: I think there would be a rash of mistakes as people tried to scoop each other, as we are seeing on this story now.

natesilver: And at least one of the big screw-ups (again, the NYT “no clear link” story) was pretty helpful to Trump.

meghan: Chad is typing!

cwick (Chadwick Matlin, deputy editor): I’ve been lurking … and am now butting in to say that this affair shows me it’s more of a bias toward getting a scoop than a bias toward a liberal viewpoint.

No matter how good the editing structure, journalists are by their nature aggressive even when they know they need to be cautious. The role anonymous sources play in this kind of coverage is but one example of this scoop bias.

sarahf: Yes, and I think it’s these high-profile missteps that further this idea that the Mueller-Russia stories are part of a left-wing bias.

natesilver: I’ll put it like this: I’m not sure that left-wing bias is a factor, but I’m certainly not sure that it’s not not a factor. (Note the double negative there.)

sarahf: A healthy dose of skepticism is definitely missing from the conversation.

perry: I do think people assume the worst about Trump. But I do not think they would do the same for, say, President Jeb Bush, so this is not just about partisanship.

natesilver: Maybe that’s a good way to put it. Reporters are willing to believe the worst about Trump. So maybe it doesn’t take as much info from sources for reporters to say, “Let’s run with it,” because the story matches their priors.

Although, yeah, maybe their priors should be willing to believe stuff about Trump that they would not believe about Jeb Bush … or Obama.

perry: Like the idea of Trump asking Cohen to lie is not crazy, at all. Cohen has already suggested Trump wanted him to violate campaign finance laws.

natesilver: It’s not crazy at all. Although there’s a lot of middle ground between “directed” (BuzzFeed’s term) versus “encouraged” versus “hinted at,” etc.

sarahf: But that’s the rub. Without more evidence of what Trump did when, it doesn’t really help the reader understand any better what happened. Which is the problem with stories like this. Is that fair? That the rush to be first and get the scoop puts you at risk of not doing good journalism?

And as a result, also jeopardizing the credibility of the investigation?

perry: I mean, the credibility of the investigation is not really in the hands of journalists.

natesilver: Yeah. Although Trump will try to muddy the waters, depending on what the investigation says.

perry: But I think the credibility of the journalism overall does depend on how we cover big stories. And yes, the rush to get scoops is a potential danger to journalism, especially if it results in big misses.

meghan: I just feel bad for readers trying to figure out what is going on.

natesilver: But the whole reason the special counsel put out that statement was presumably so that their credibility would not be damaged. Keep in mind that they have their own narrative about Cohen, which (from his plea agreement) is that he lied to Congress about Trump Tower Moscow because of his overall loyalty to Trump … and not necessarily because he was directed to do so.

So that could have led to claims that the Mueller report was “underwhelming” or had “overpromised,” etc., even though it hadn’t been the Mueller investigation making the claim in the first place.

This is sort of a dumb analogy, but it’s a little bit like, when someone else puts out an election forecast that we think is really wrong, we’ll sometimes push back hard against it and be quite vocal and obnoxious about it, just because we don’t want anyone to confuse it for our forecast.

meghan: Insert joke about us being obnoxious here

January 22, 2019

Politics Podcast: Kamala Harris’s Path To The 2020 Nomination

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Sen. Kamala Harris of California announced Monday that she is running for president in 2020. In the latest installment of “The Theory of the Case,” the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew analyzes how she could win the Democratic nomination and why she might fall short. The team also reacts to the statement from the office of special counsel Robert Mueller saying that BuzzFeed’s report that President Trump directed Michael Cohen to lie to Congress is “not accurate.” Then the group takes a look at what the young left wants — and how it is trying to reshape the Democratic Party.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 19, 2019

Will Trump’s Compromise Help End The Shutdown? And Was It Even A Compromise?

Welcome to a special weekend-edition of FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, managing editor): Hey, everyone! We’ve convened here on a weekend(!) to talk about President Trump’s address to the nation on Saturday. Trump called the country together to make an offer to Democrats to try to end the partial government shutdown, now more than 28 days old.

Here’s Trump’s offer, summarized by Bloomberg News reporter Sahil Kapur:

President Trump outlines his offer:

• $800 million for “urgent humanitarian assistance”

• $805 million for drug detection technology

• 2,750 new border agents

• 75 new immigration judge teams

• $5.7 billion for a wall

• 3-year DACA protection for 700k

• 3-year TPS

— Sahil Kapur (@sahilkapur) January 19, 2019

So, the question in front of us: Is this offer likely to end the shutdown? And, more generally, is this a smart move politically by Trump, who’s seen his job approval rating erode as the shutdown has dragged on?

Let’s briefly start with that first question. What do you make of Trump’s offer? Will it bring about the end of the shutdown?

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): No.

micah: lol.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Nyet.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): It’s not at all likely to end the shutdown. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi bashed the proposal before the speech started (once reports came out with Trump’s offer). He didn’t consult Democrats before the proposal was released. It’s not clear he was even really trying to get Democrats to sign onto this.

sarahf: Yeah, what I don’t understand about the proposal is that it was negotiated without any Democratic input. It was just Vice President Mike Pence, Senior Adviser Jared Kushner and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell talking with fellow Republicans.

natesilver: I mean, there are some permutations where this is the beginning of the end of the shutdown, I suppose.

Those have to involve some combination of (i) Trump offering a better deal than what he’s offering right now, and (ii) public opinion shifting to put more pressure on Democrats.

micah: So is the best way to look at this address as basically a political ploy — an attempt to change the politics of the shutdown? (I don’t mean “ploy” in a negative sense.)

perry: I think that’s the only way to look at this.

natesilver: The real audience for the speech is likely the media. Because we’re the only people sick enough to actually waste our Saturdays watching this thing.

slackbot: I’m sorry you aren’t feeling well. There is Advil, Aleve and Tylenol in the cabinet in front of Nate’s office/Vanessa’s desk.

micah: lol

natesilver: lol, slackbot

Anyway, in theory, “we’re willing to compromise and Democrats” aren’t is a perfectly decent message. It’s BS in various ways (mostly because the compromise Trump is offering isn’t too good). But it’s a fairly conventional message — to sell a not-very-great compromise as being a good deal.

sarahf: Right now, Americans overwhelmingly continue to blame Trump and congressional Republicans for the shutdown. Saturday’s speech seemed like an attempt on his part to try and shift some of that narrative by outlining a proposal that definitely seemed like a compromise.

perry: And I think it has as few potential good effects for Trump. First, it may help keep Republicans on Capitol Hill aligned with him. They were getting leery of his wall-only strategy. This makes it easier for the party to unify around him.

Second, Trump’s proposal allows McConnell to hold a vote and suggest he and his chamber are trying to resolve the shutdown too, just like the House is doing.

Finally, I assume, when pollsters ask people about this proposal, it will be more popular than the wall itself. My guess is it will be near 50 percent support and perhaps higher. Most people I assume aren’t totally against any money for the wall and feel like Dreamers must have a path to citizenship or else.

sarahf: And I don’t know if it’s a good look for Democratic leaders like Pelosi to immediately come out the gate saying, “nope this doesn’t work.” Then again, they weren’t consulted in the making of the deal it sounds like, so maybe she’d be better off highlighting that.

natesilver: I did think it was weird that Trump opened the address with a sort of uncharacteristically gentle paean to the virtues of legal immigration, but then careened to talking about drugs and gangs and violence and some of the other stuff that doesn’t usually pass a fact check. If you actually wanted to portray an image of bipartisanship, you could skip most of that stuff. Or you could talk about how there were extremists on both sides — call out Republicans for X and Y reason.

micah: Well …

I do wonder if this could change the politics of the shutdown in more than one way, as Perry was getting at.

It could make Democrats look like the intransigent side, as you were all saying.

But, it could also shift the narrative towards more “border crisis” and less “wall.” And that’s better political ground for Trump. Polls show more people believe there is a crisis at the border than support a wall.

sarahf: Right, last week we looked at different pollsters who asked Americans what they thought of the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border. I was surprised by the number of Americans who thought it was a serious problem or a crisis. Fifty-four percent of respondents in a Quinnipiac poll said they believed there was a security crisis along the border with Mexico. And in a CBS News/YouGov poll, 55 percent said the situation was “a problem, but not a crisis.”

natesilver: It could shift things — although, again, it’s worth mentioning that the deal Trump offered isn’t really much of a deal at all.

In fact, it offers a bit less than what they floated last night.

That was my read too -& this is a crucial distinction Democrats are already seizing upon. WH officials last night said it was the Bridge Act-& confirmed that to other reporters today-but what Trump announced just now is NOT the Bridge Act, it's a more limited twist on it. https://t.co/CxX154n9As

— Jonathan Swan (@jonathanvswan) January 19, 2019

The DACA part itself is a compromise, but to get that compromise, Democrats have to give up something (wall funding) that they’re firmly opposed to.

Although, it probably is fair to say that the wall is also a compromise of sorts. As Trump actually emphasized. It’s not all that much wall. It’s certainly not a big concrete wall stretching the length of the border.

sarahf: I know! OMG, what a 180 from him on that!

And, as Democrats will be quick to point out, they were already working on their own legislation that would give $1 billion in funding for border security (but not a wall – to be clear).

natesilver: Right, and Trump hasn’t really made the case as to why a wall is necessary to stop the humanitarian crisis at the border.

The other thing is that … none of this is really new. This compromise, if you want to call it that, has been around for a long time. Democrats have rejected it because it doesn’t give them enough. They rejected better versions of this compromise before the shutdown began, in fact.

And Democrats have more leverage now than then because Trump needs the shutdown to end a lot more than they do — it’s hurting him politically.

micah: I guess my point is more that the convo may change.

perry: To put this bluntly, I think this speech had two audiences the media (so they will do “both sides” coverage) and Republicans (so they will stay loyal to Trump on this issue). I assume this speech will buy him at least of few days of that. And both of those, as Micah suggests, will help with the public opinion.

sarahf: I was kind of surprised that he made no mention of the thousands of furloughed government workers.

Like some kind of nod to their hardship. But nada.

perry: They’re all Democrats.

I’m joking, but that is what he thinks.

natesilver: The question is partly: will the press run with Trump’s frame?

micah: Nate, I don’t know if the media will run with it.

Probably?

The headline in the lower-third on CNN right now is “Pelosi rejects Trump’s proposal to end shutdown.”

perry: Trump may have bought himself at least another week to sustain this shutdown. Next week will be 1. Pelosi rejected Trump’s idea before he spoke, and 2. Senate holds vote and Democrats filibuster.

You all disagree?

micah: I think that’s right, Perry.

As we’re chatting, here’s Politico’s headline: “Trump’s bid to negotiate on wall met by Democratic rejection”

The Washington Post: “Trump offers to protect ‘dreamers’ temporarily in exchange for wall funds”

Dallas Morning News: “Trump seeks border wall funding in exchange for DACA protections to end shutdown”

natesilver: There’s at least some semi-intelligent understanding on the White House’s part of how media dynamics work.

At least parts of the speech play well into the media’s “both sides-ism.”

micah: NBC News: “Trump offers new shutdown deal, Democrats expected to reject it”

Los Angeles Times: “President Trump proposes to extend protections for ‘Dreamers’ in exchange for border wall funding”

ABC News: “Trump will extend ‘Dreamers,’ TPS protection in exchange for full border wall funding”

CBS News: “Trump proposes deal on immigration, Pelosi calls shutdown offer a ‘non-starter’”

natesilver: But the thing about that NBC headline is that the “new” part is pretty misleading.

perry: Those are great headlines for Trump. Considering the reality is closer to this:

Isn't this a kind of hostage-taking squared? First end the programs. Then shut the government. Then promise to temporarily restore the programs you've ended & reopen the govt you have closed, in return for the ransom of $ for a wall that 55-60% of country consistent opposes? https://t.co/PhsMABh6VC

— Ronald Brownstein (@RonBrownstein) January 19, 2019

micah: Yeah, at least in the very very early going, this seems like a good move by Trump.

natesilver: Keep in mind that media might feel a little chastened this week by the mess that’s become of the BuzzFeed story.

micah: Yeah, I was thinking that.

perry: I also think that keeping the Lindsey Graham’s of the world happy is something Trump cares about. The Republicans on the Sunday shows now have something to say. So do the Will Hurd’s.

micah: Very good point.

perry: Pelosi and Democrats, I would argue, were more unified than Republicans before this speech. But I wonder if some moderate Democrats start getting nervous now.

natesilver: The path here is like:

1. Trump and Republicans maintain some degree of message discipline for a week or so;

1b. Trump and Republicans don’t face too many defections from their own base;

2. Polling and other indications show that blame for the shutdown is shifting away from Trump and toward Democrats;

2b. There aren’t any strikes or planes falling from the sky that create a crisis and force an immediate end to the shutdown;

3. Trump offers Democrats a little bit — maybe quite a bit — more.

If all of that happens, maybe he gets a deal!

And no one of those steps is *that* crazy.

perry: So the fundamentals of this issue have not changed, you are saying, Nate?

natesilver: I don’t really think it changed anything.

perry: I agree.

natesilver: Except Trump made a chess move to advance the game instead of just sitting there petulantly staring at his opponent and watching his clock run down.

micah: “It gives him some more time” is a good read, I think.

natesilver: It was an extremely standard chess move, but at least it was a move!

sarahf: Well, I mean leading up to this speech there had been some speculation he’d declare a national emergency. And he didn’t do that.

So all things considered, I think this was a much smarter political move to make.

natesilver: Oh yeah, this is definitely better than that.

sarahf: Because I do think at this point Democrats have to say something other than, “we won’t support this.”

natesilver: It was, like, almost what a normal president with a competent group of advisors would do!

sarahf: Hahaha yeah

natesilver: But it will require a lot of follow through.

perry: I think Trump is aware that declaring a national emergency is a “loss.” He doesn’t want a “loss.” I don’t know how he gets a win. I actually think, this proposal, if it was passed, would very much irritate the right.

I will be curious how the right receives this idea.

perry: Ann Coulter attacked it hard.

natesilver: Coulter attacked it … although… you could almost say that’s helpful for Trump.

perry: Good point.

It makes it seem like more of a compromise if the right hates it.

natesilver: Now, if he loses the votes from several conservative Republicans in the Senate, then he’s screwed.

Or if he himself has second thoughts because Sean Hannity calls him tonight, he could screw himself.

perry: That’s an interesting question: Can Sen. Ted Cruz vote for this?

Can it actually pass the Senate?

micah: That is interesting!

perry: Because I assume part of the play here is for Republicans in the Senate to be seen doing something about the shutdown.

Would Sens. Susan Collins and Cory Gardner support this from the left-wing of the GOP? I think yes. But would Cruz, and some of the more hard-core immigration members on the more conservative wing of the party?

I assume yes, but I’m not sure.

micah: Wouldn’t you assume he cleared this with the Cruz’s of the world before unveiling it?

perry: I would not at all assume that.

micah: LOL.

That was a soft-ball.

perry: McConnell maybe.

sarahf: Yeah, I’m not picturing mass Republican defections here in the Senate … I guess just because McConnell seems to have been so heavily involved in negotiating this.

natesilver: Right, yeah

perry: Do we think any Democrats vote for it?

Doug Jones? Joe Manchin?

I assume no, right?

natesilver: Manchin maybe.

He voted to confirm Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, so it’s not exactly like he’s worried about stoking the ire of the Democratic base.

sarahf: But it does make you wonder why Trump ever listened to Mark Meadows and the Freedom Caucus in the first place getting into this mess.

Wouldn’t have $1.7 billion or whatever it was and no extension for DACA, TPS, etc. have been more popular for them?

I guess none of it went to the wall. So maybe not. No way to appease anyone!

natesilver: Right, the $1.7 billion didn’t specifically include border wall funding though.

perry: Another question: I think I’m a believer in the distraction theory, so would Trump have scheduled this speech if he knew Buzzfeed’s Michael Cohen story would be so heavily criticized?

micah: He sorta stepped on a pretty good news cycle for him.

Though Buzzfeed is standing by its reporting.

natesilver: Hmm. But the fact that he had a good news cycle probably means that today will be portrayed more favorably by the press.

So that gave him more incentive to do it.

perry: So you think the media, cowed by the coverage of the Cohen story, will cover this announcement more favorably than otherwise?

natesilver: The headlines we’re seeing are not “Embattled Trump desperately proposes already-rejected compromise in meandering speech,” but rather “Trump proposes new compromise and Pelosi rejects.”

micah: And you think the former is more accurate than the latter?

natesilver: I think “Trump again proposes already-rejected compromise in competent speech; Pelosi reiterates that she won’t agree” is roughly correct.

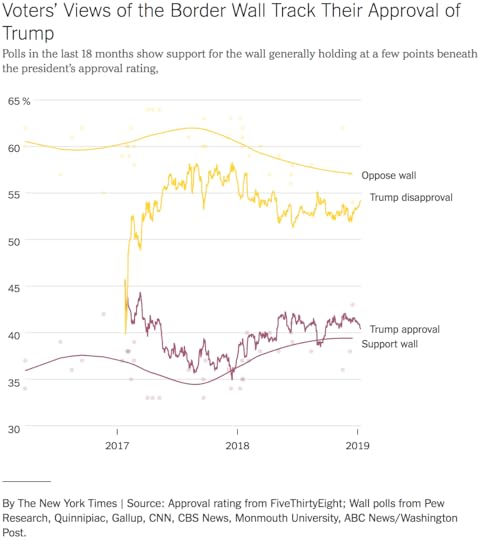

micah: The other thing maybe worth keeping in mind: The politics of the shutdown right now are really bad for Trump. Trump is unpopular, and the wall is even more unpopular. This is from our friends at The Upshot:

micah: And this is from us:

I guess what I’m saying is that it wouldn’t be too surprising if the politics of this improved for Trump after his speech, given where they are now. There’s plenty of room to improve.

Anyway … final thoughts?

perry: We know that presidential addresses generally don’t work. But Trump is making those political scientists look really smart.

sarahf: I think the fact that Trump didn’t consult Democratic leadership is a big ding against this proposal. But the fact that Trump did put forward some kind of compromise is something. It has the potential to change the politics around the shutdown.

It’ll be interesting to see what congressional Republicans actually put forward and what Democrats choose to counter with.

natesilver: I thought it was a bit weird at the end when Trump said this was just the start of negotiations on a much bigger immigration solution.

If this is just small potatoes stuff, Pelosi might ask, why do we need to keep the government shut down, when we’re going to have a much bigger discussion about immigration anyway?

That’s ultimately the question that Trump doesn’t really have a good answer for. Why do we need to keep the government shut down to have this negotiation?

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and Pelosi will need to be clear about that in their own messaging.

At the same … I wonder if they also want to float, maybe on background because it does sort of contradict the message of “no negotiations at all while there’s a shutdown,” some notion of what a real compromise would look like. e.g. the full DREAM Act.

Or my idea: Offer HR1, the Democrats’ election reform/voting rights bill, in exchange for the border wall.

perry: The one reason I have a hard time seeing any deal being cut: “the wall is a monument to racism” is a real view on the left and has real influence. That makes it much harder Democrats to sign off on any money for the wall.

natesilver: Also, Republicans would presumably never agree to HR 1. But it moves the Overton Window (sorry if that’s become an overused concept now) and frames the idea that Republicans are nowhere near offering a fair compromise.

If the wall is so important to Trump — and he’s often talked about it as his signature priority — a fair offer now that we have bipartisan control of government would be to give Democrats what’s literally their No. 1 priority (given that they named the bill HR1) as well.

(That’s Pelosi’s hypothetical argument, not me necessarily endorsing the deal as fair to Republicans.)

micah: Yeah, that kind of deal seems a looooooong ways off.

January 18, 2019

Emergency Politics Podcast: What If Trump Told Cohen To Lie To Congress?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In this emergency installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew reacts to a BuzzFeed News report that “President Donald Trump directed his longtime attorney Michael Cohen to lie to Congress about negotiations to build a Trump Tower in Moscow.” FiveThirtyEight contributor Amelia Thomson-Deveaux also weighs in on what information we still need in order to understand the allegation.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 16, 2019

Will The Shutdown Hurt Trump’s Re-election Chances?

The partial government shutdown is beginning to drag on President Trump’s approval rating, which is at its lowest point in months. As of early Wednesday evening, his approval rating was 40.2 percent, according to our tracking of public polling, down from 42.2 percent on Dec. 21, the day before the shutdown began. It’s his lowest score since last September. And Trump’s disapproval rating was 54.8 percent, up from 52.7 percent before the shutdown. His net approval rating, -14.6 percent, was at its lowest point since February 2018.

There shouldn’t be much doubt that the shutdown is behind the negative turn in Trump’s numbers. While there have been other newsworthy events over the past few weeks, such as turnover among Trump’s senior staffers and a wobbly stock market, the shift is well-timed to the start of the shutdown on Dec. 22. Trump’s approval ratings had been steady at about 42 percent for several months before the shutdown. Since then, they’ve been declining at a fairly linear rate of about half a point for every week that the shutdown has been underway, while his disapproval rating has increased by half a point per week. Trump’s increasingly negative ratings match polling showing Americans growing concerned about the shutdown and disliking Trump’s handling of it. In a Marist College poll that was released this week, for example, 61 percent of respondents said the shutdown had given them a more negative view of Trump, while just 28 percent said they felt more positively toward him.

So all of that sounds pretty bad for Trump. But will any of it really matter to Trump’s political standing, in the long run?

The glib answer is “probably not.” We’re a loooong way from the presidential election. And presidential approval ratings, as well as those for congressional leaders, typically rebound within a couple of months of a shutdown ending. A shutdown in October 2013 that caused a steep decline in ratings for congressional Republicans didn’t prevent them from having a terrific midterm in 2014, for instance.

Also consider the insane velocity of the news cycle under President Trump. If the shutdown were to end on Feb. 15, and special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on the Russia investigation were to drop the next day, would anyone still be talking about the shutdown?

Moreover, there hasn’t been that much of a shift, so far. In the context of the narrow historic range of President Trump’s approval ratings, which have rarely been higher than 43 percent or lower than 37 percent, a 2-point shift might seem relatively large. But it’s still just 2 points, when many past presidents saw there numbers gyrate up and down by 5 or 10 points at a time.

But I wonder if that answer isn’t a little too glib. There are some reasons for Trump and Republicans to worry that the shutdown could have both short- and long-term downsides.

For one thing, there’s no particular sign that the shutdown is set to end any time soon. And if the decline in Trump’s approval rating were to continue at the same rate that it has so far, it would take his political standing from bad to worse. By Jan. 29, for example, the day that Trump was originally set to deliver the State of the Union address before House Speaker Nancy Pelosi disinvited him from addressing Congress, his approval rating would be 39.3 percent, and his disapproval rating would be 55.9 percent. By March 1, at which point funding for federal food stamps could run out, his approval rating and disapproval rating would be 36.9 percent and 58.4 percent, respectively, roughly matching the lowest point of his presidency so far.

In addition, because this is already the longest shutdown in U.S. history, past precedent for the political impact of shutdowns may not be fully informative. There’s the possibility that the shutdown ends not with a whimper (with Trump caving or with he and Pelosi anticlimactically reaching a compromise) but instead with a literal or proverbial bang, such as the government bungling a response to a natural or man-made disaster.

A prolonged shutdown could also materially affect the economy, although there could be some catch-up growth later. A temporary decline in GDP or consumer confidence probably wouldn’t affect Trump’s re-election, although a long-term decline obviously would.

Despite those possibilities, I’d still put a lot of weight toward our historical priors, which contain relatively good news for Trump. With almost 22 months to go until the election, it’s too early for either approval ratings or economic data to be highly predictive of a president’s re-election chances. Furthermore, approval ratings tend to rebound after shutdowns, and in any event, the decline in Trump’s numbers hasn’t been all that large, yet.

Nonetheless, if I were hoping for Trump’s re-election, there are two indirect reasons that the shutdown and its fallout would worry me. One has to do with his relationship with the congressional GOP; the other with his strategic posture toward his re-election bid.

The shutdown may have frayed Trump’s relationship with Republicans in Congress

Republican leaders in Congress didn’t want the shutdown in the first place. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and former Majority Whip John Cornyn originally thought they’d talked Trump out of shutting down the government — “I don’t know anybody on the Hill that wants a shutdown, and I think all the president’s advisers are telling him this would not be good,” Cornyn told Politico on Dec. 18 — before Trump shifted strategies in response to right-wing pressure.

Meanwhile, two of the most vulnerable Republican senators — Colorado’s Cory Gardner and Maine’s Susan Collins — have called for an end to the shutdown. Another, North Carolina’s Thom Tillis, has called for a compromise with Democrats on the border wall and DACA, a deal that the White House rejected last year.

So it isn’t entirely surprising that Republicans in both the House and the Senate have starkly and sometimes sarcastically critiqued Trump’s shutdown strategy.

Congressional Republicans are not a group Trump can easily afford to lose. They have a lot of power to check Trump’s presidency, from modest measures such as treating his Cabinet nominations with more scrutiny to extreme ones like supporting his impeachment and removal from office. Obviously that’s getting way, way ahead of ourselves, and Trump’s approval ratings remain very strong among Republicans for now. That may constrain how much members of Congress push back against the president. But the conventional wisdom is arguably too dismissive of the possibility of an inflection point. Richard Nixon’s approval ratings had been in the low-to-mid-80s among Republican voters for years, but they suddenly fell into the 50s over the course of a few months in 1973. He resigned in August 1974.

The shutdown has prompted Trump to double down on his all-base, all-the-time strategy

But if Trump wants to get re-elected, his biggest problem isn’t what Republicans think about him; it’s what the rest of the country does.

The lesson of the midterms, in my view, was fairly clear: Trump’s base isn’t enough. The 2018 midterms weren’t unique in the scale of Republican losses: losing 40 or 41 House seats is bad, but the president’s party usually does poorly at the midterms. Rather, it’s that these losses came on exceptionally high turnout of about 119 million voters, which is considerably closer to 2016’s presidential year turnout (139 million) than to the previous midterm in 2014 (83 million). Republicans did turn out in huge numbers for the midterms, but the Democratic base — which is larger than the Republican one — turned out also, and independent voters strongly backed Democratic candidates for the House.

Plenty of presidents, including Obama, Clinton and Reagan, recovered from poor midterms to get re-elected. But those presidents typically sought to pivot or “triangulate” toward the center; we don’t know if the political rebound occurs if the pivot doesn’t. Instead, Trump has moved in the opposite direction. Despite some initial attempts at reaching out to the center, such as in passing a criminal justice bill in December and issuing trial balloons about an infrastructure package, Trump’s strategy of shutting down the government to insist on a border wall was aimed at placating his critics on the right, such as Rush Limbaugh and Ann Coulter, and members of the House Freedom Caucus.

Maybe Trump took some of the wrong lessons from 2016. Trump may mythologize 2016 as an election in which he was brought into the White House on the strength of his base, but that isn’t necessarily why he won. And even if it was, trying to duplicate the strategy might not work again:

Trump probably won’t face off against an opponent as unpopular as Hillary Clinton, by some measures the most unpopular candidate in general election history except for Trump himself.

He won’t necessarily be the preferred candidate for voters who are on the fence between Trump and his opponent. (In 2016, voters who disliked both Clinton and Trump went for Trump by 17 points.)

If he’s pursuing policies such as shutting down the government to demand a border wall, swing voters may no longer see Trump as a moderate, as (somewhat contrary to the conventional wisdom) they did in 2016.

Trump might or might not benefit from the same Electoral College advantage that he had in 2016.

And he probably won’t have an FBI investigation against his opponent reopened 10 days before the election.

Given that, perhaps 2018 is a better model for 2020 than 2016. In the midterms, voting closely tracked Trump’s approval ratings, and he paid the price for his unpopularity. According to the exit poll, midterm voters disapproved of Trump’s performance by a net of 9 percentage points. Not coincidentally, Republicans also lost the popular vote for the House by 9 percentage points.

There’s plenty of time for Trump’s numbers to improve, but for now, they’re getting worse. So while the shutdown’s consequences may not last into 2020, it has been another step in the wrong direction at a moment when presidents have usually pivoted to the center.

The Shutdown Is Hurting Trump’s Approval Rating. But Will It Hurt Him in 2020?

The partial government shutdown is beginning to drag on President Trump’s approval rating, which is at its lowest point in months. As of early Wednesday evening, his approval rating was 40.2 percent, according to our tracking of public polling, down from 42.2 percent on Dec. 21, the day before the shutdown began. It’s his lowest score since last September. And Trump’s disapproval rating was 54.8 percent, up from 52.7 percent before the shutdown. His net approval rating, -14.6 percent, was at its lowest point since February 2018.

There shouldn’t be much doubt that the shutdown is behind the negative turn in Trump’s numbers. While there have been other newsworthy events over the past few weeks, such as turnover among Trump’s senior staffers and a wobbly stock market, the shift is well-timed to the start of the shutdown on Dec. 22. Trump’s approval ratings had been steady at about 42 percent for several months before the shutdown. Since then, they’ve been declining at a fairly linear rate of about half a point for every week that the shutdown has been underway, while his disapproval rating has increased by half a point per week. Trump’s increasingly negative ratings match polling showing Americans growing concerned about the shutdown and disliking Trump’s handling of it. In a Marist College poll that was released this week, for example, 61 percent of respondents said the shutdown had given them a more negative view of Trump, while just 28 percent said they felt more positively toward him.

So all of that sounds pretty bad for Trump. But will any of it really matter to Trump’s political standing, in the long run?

The glib answer is “probably not.” We’re a loooong way from the presidential election. And presidential approval ratings, as well as those for congressional leaders, typically rebound within a couple of months of a shutdown ending. A shutdown in October 2013 that caused a steep decline in ratings for congressional Republicans didn’t prevent them from having a terrific midterm in 2014, for instance.

Also consider the insane velocity of the news cycle under President Trump. If the shutdown were to end on Feb. 15, and special counsel Robert Mueller’s report on the Russia investigation were to drop the next day, would anyone still be talking about the shutdown?

Moreover, there hasn’t been that much of a shift, so far. In the context of the narrow historic range of President Trump’s approval ratings, which have rarely been higher than 43 percent or lower than 37 percent, a 2-point shift might seem relatively large. But it’s still just 2 points, when many past presidents saw there numbers gyrate up and down by 5 or 10 points at a time.

But I wonder if that answer isn’t a little too glib. There are some reasons for Trump and Republicans to worry that the shutdown could have both short- and long-term downsides.

For one thing, there’s no particular sign that the shutdown is set to end any time soon. And if the decline in Trump’s approval rating were to continue at the same rate that it has so far, it would take his political standing from bad to worse. By Jan. 29, for example, the day that Trump was originally set to deliver the State of the Union address before House Speaker Nancy Pelosi disinvited him from addressing Congress, his approval rating would be 39.3 percent, and his disapproval rating would be 55.9 percent. By March 1, at which point funding for federal food stamps could run out, his approval rating and disapproval rating would be 36.9 percent and 58.4 percent, respectively, roughly matching the lowest point of his presidency so far.

In addition, because this is already the longest shutdown in U.S. history, past precedent for the political impact of shutdowns may not be fully informative. There’s the possibility that the shutdown ends not with a whimper (with Trump caving or with he and Pelosi anticlimactically reaching a compromise) but instead with a literal or proverbial bang, such as the government bungling a response to a natural or man-made disaster.

A prolonged shutdown could also materially affect the economy, although there could be some catch-up growth later. A temporary decline in GDP or consumer confidence probably wouldn’t affect Trump’s re-election, although a long-term decline obviously would.

Despite those possibilities, I’d still put a lot of weight toward our historical priors, which contain relatively good news for Trump. With almost 22 months to go until the election, it’s too early for either approval ratings or economic data to be highly predictive of a president’s re-election chances. Furthermore, approval ratings tend to rebound after shutdowns, and in any event, the decline in Trump’s numbers hasn’t been all that large, yet.

Nonetheless, if I were hoping for Trump’s re-election, there are two indirect reasons that the shutdown and its fallout would worry me. One has to do with his relationship with the congressional GOP; the other with his strategic posture toward his re-election bid.

The shutdown may have frayed Trump’s relationship with Republicans in Congress

Republican leaders in Congress didn’t want the shutdown in the first place. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and former Majority Whip John Cornyn originally thought they’d talked Trump out of shutting down the government — “I don’t know anybody on the Hill that wants a shutdown, and I think all the president’s advisers are telling him this would not be good,” Cornyn told Politico on Dec. 18 — before Trump shifted strategies in response to right-wing pressure.

Meanwhile, two of the most vulnerable Republican senators — Colorado’s Cory Gardner and Maine’s Susan Collins — have called for an end to the shutdown. Another, North Carolina’s Thom Tillis, has called for a compromise with Democrats on the border wall and DACA, a deal that the White House rejected last year.

So it isn’t entirely surprising that Republicans in both the House and the Senate have starkly and sometimes sarcastically critiqued Trump’s shutdown strategy.

Congressional Republicans are not a group Trump can easily afford to lose. They have a lot of power to check Trump’s presidency, from modest measures such as treating his Cabinet nominations with more scrutiny to extreme ones like supporting his impeachment and removal from office. Obviously that’s getting way, way ahead of ourselves, and Trump’s approval ratings remain very strong among Republicans for now. That may constrain how much members of Congress push back against the president. But the conventional wisdom is arguably too dismissive of the possibility of an inflection point. Richard Nixon’s approval ratings had been in the low-to-mid-80s among Republican voters for years, but they suddenly fell into the 50s over the course of a few months in 1973. He resigned in August 1974.

The shutdown has prompted Trump to double down on his all-base, all-the-time strategy

But if Trump wants to get re-elected, his biggest problem isn’t what Republicans think about him; it’s what the rest of the country does.

The lesson of the midterms, in my view, was fairly clear: Trump’s base isn’t enough. The 2018 midterms weren’t unique in the scale of Republican losses: losing 40 or 41 House seats is bad, but the president’s party usually does poorly at the midterms. Rather, it’s that these losses came on exceptionally high turnout of about 119 million voters, which is considerably closer to 2016’s presidential year turnout (139 million) than to the previous midterm in 2014 (83 million). Republicans did turn out in huge numbers for the midterms, but the Democratic base — which is larger than the Republican one — turned out also, and independent voters strongly backed Democratic candidates for the House.

Plenty of presidents, including Obama, Clinton and Reagan, recovered from poor midterms to get re-elected. But those presidents typically sought to pivot or “triangulate” toward the center; we don’t know if the political rebound occurs if the pivot doesn’t. Instead, Trump has moved in the opposite direction. Despite some initial attempts at reaching out to the center, such as in passing a criminal justice bill in December and issuing trial balloons about an infrastructure package, Trump’s strategy of shutting down the government to insist on a border wall was aimed at placating his critics on the right, such as Rush Limbaugh and Ann Coulter, and members of the House Freedom Caucus.

Maybe Trump took some of the wrong lessons from 2016. Trump may mythologize 2016 as an election in which he was brought into the White House on the strength of his base, but that isn’t necessarily why he won. And even if it was, trying to duplicate the strategy might not work again:

Trump probably won’t face off against an opponent as unpopular as Hillary Clinton, by some measures the most unpopular candidate in general election history except for Trump himself.

He won’t necessarily be the preferred candidate for voters who are on the fence between Trump and his opponent. (In 2016, voters who disliked both Clinton and Trump went for Trump by 17 points.)

If he’s pursuing policies such as shutting down the government to demand a border wall, swing voters may no longer see Trump as a moderate, as (somewhat contrary to the conventional wisdom) they did in 2016.

Trump might or might not benefit from the same Electoral College advantage that he had in 2016.

And he probably won’t have an FBI investigation against his opponent reopened 10 days before the election.

Given that, perhaps 2018 is a better model for 2020 than 2016. In the midterms, voting closely tracked Trump’s approval ratings, and he paid the price for his unpopularity. According to the exit poll, midterm voters disapproved of Trump’s performance by a net of 9 percentage points. Not coincidentally, Republicans also lost the popular vote for the House by 9 percentage points.

There’s plenty of time for Trump’s numbers to improve, but for now, they’re getting worse. So while the shutdown’s consequences may not last into 2020, it has been another step in the wrong direction at a moment when presidents have usually pivoted to the center.

Politics Podcast: Kirsten Gillibrand’s Path To The 2020 Nomination

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand announced Tuesday on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” that she is running for president. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team makes the case for why she will — and won’t — be the Democratic nominee in 2020.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

January 15, 2019

How 17 Long-Shot Presidential Contenders Could Build A Winning Coalition

Graphics by Rachael Dottle

It might seem obvious that having a wide-open field, as Democrats have for their 2020 presidential nomination, would make it easier for a relatively obscure candidate to surge to the top of the polls. But I’m not actually sure that’s true. Democrats might not have an “inevitable” frontrunner — the role that Hillary Clinton played in 2016 or Al Gore did in 2000. But that very lack of heavyweights has encouraged pretty much every plausible middleweight to join the field, or at least to seriously consider doing so. Take the top 10 or so candidates, who are a fairly diverse lot in terms of race, gender and age — pretty much every major Democratic constituency is spoken for by at least one of the contenders. After all, it was the lack of competition that helped Bernie Sanders gain ground in 2016; he was the only game in town other than Clinton.1

So as I cover some of the remaining candidates in this, the third and final installment of our “five corners” series on the Democratic field, you’re going to detect a hint of skepticism about most of their chances. (The “five corners” refers to what we claim are the the five major constituencies within the Democratic Party: Party Loyalists, The Left, Millennials and Friends, Black voters and Hispanic voters2; our thesis is that a politician must build a coalition consisting of at least three of these five groups to win the primary.) It’s not that some of them couldn’t hold their own if thrust into the spotlight against one or two other opponents. Instead, it’s that most of them will never get the opportunity to square off against the big names because the middleweights will monopolize most of the money, staff talent and media attention. Rather than pretend to be totally comprehensive, in fact, I’m instead going to list a few broad typologies of candidates that weren’t well-represented in the previous installments of this series.

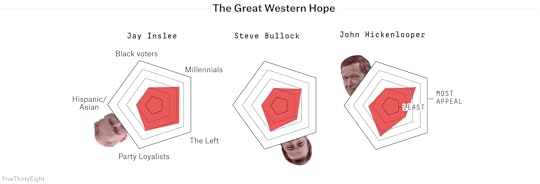

This type of candidate has been popular in the minds of journalists ever since Gary Hart’s failed presidential bids in 1984 and 1988 — but it never seems to gain much momentum among actual Democratic voters. In this scenario, a Western governor or senator (e.g. Hart, Bruce Babbitt or Bill Richardson) runs on a platform that mixes environmentalism, slightly libertarianish views on other issues (legal weed but moderate taxes?) and a vague promise to shake things up and bring an outsider’s view to Washington.

This platform makes a lot of sense in the Mountain West, but I’m not sure how well it translates elsewhere in the country. In theory, the environmental focus should have some appeal among millennials. (That particularly holds for Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, who would heavily focus on climate change in his campaign as a means of differentiating himself.) And Party Loyalists might get behind an outsider if they were convinced that it would help beat President Trump, but “let’s bring in an outsider to shake things up” was one of the rationales that Trump himself used to get elected, so it doesn’t make for as good a contrast in 2020 as it might ordinarily. The Left isn’t likely to be on board with the Great Western Hope platform, which tends to be moderate on fiscal policy. And while the states of the Mountain West have quite a few Hispanic voters, they don’t have a lot of black ones. It’s not that Inslee or former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper aren’t “serious” candidates — being a multi-term governor of medium-sized state is traditionally a good credential — but it’s also not clear where the demand for their candidacies would come from.

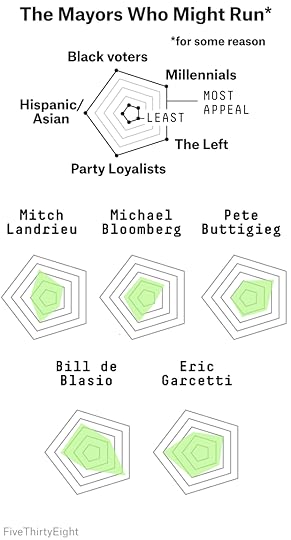

You might say something similar about the various mayors that are considering a presidential bid.What niche are the mayors hoping to fill, and are there actually any voters there?

Maybe in “The West Wing,” a hands-on problem solver from Anytown, USA, would make the perfect antidote to a Trumpian president. In the real world, Democrats think the country is in crisis under Trump, and there are a lot of candidates who have more experience dealing with national problems.