Nate Silver's Blog, page 75

January 14, 2019

Politics Podcast: Julian Castro’s Path To The 2020 Nomination

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Julian Castro, a former mayor of San Antonio mayor and a former secretary of housing and urban development, announced his candidacy for president on Saturday. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team debates what his seemingly long-shot path to the Democratic nomination could look like. The crew also lays out a rubric for evaluating candidate strengths and weaknesses and discusses the political situation that has kept the government partially shut down for a record amount of time.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Why Harris And O’Rourke May Have More Upside Than Sanders And Biden

Graphics by Rachael Dottle

Last week, we introduced a method for evaluating Democratic presidential contenders, which focused on their ability to build a coalition among key constituencies within the party. In particular, our method claims there are five essential groups of Democratic voters, which we describe as:

Party Loyalists, who are mostly older, lifelong Democrats who care about experience and electability.

The Left.

Millennials and Friends, who are young, cosmopolitan and social-media-savvy.

Black voters.

And Hispanic voters, who for some purposes can be grouped together with Asian voters.

The goal is for candidates to form a coalition consisting of at least three of the five groups.

I certainly wouldn’t claim that this is the only way to evaluate the field; rather, it’s part of what we hope will be a fairly broad toolkit of approaches that we’ll be applying as we cover the Democratic candidates at FiveThirtyEight over the course of the next 18(!!) months.1 Furthermore, in reality, the various ideological and demographic constituencies within the Democratic Party are more fluid than this analysis implies. Nonetheless, it has influenced my thinking — the coalition-building model has made me more skeptical about the chances for Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar, for instance, but more bullish about Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke and Cory Booker. In this article, I’ll go through a set of 10 leading contenders and map out their potential winning coalitions; we’ll tackle some of the long-shot candidates later on this week.

Let’s start with the man who has led most polls of the Democratic field so far, former Vice President Joe Biden. One lesson from the 2016 Republican primary might be to approach the polls with more humility. If a candidate is ahead in the polls for a sustained period of time — as Trump was for much of late 2015 and early 2016 — maybe we journalists ought to give a certain amount of credit to that, rather than just chalking it up to high name recognition or becoming overly wedded to some theory about how voters are “supposed” to behave.

With that said, there are some trouble signs for Biden. He performs worse among those voters who are paying the most attention to the primary, suggesting that his high name recognition compared to most other candidates is a significant factor in his lead.

And I’m not sure it’s going to be very easy for Biden to expand his coalition beyond the 25 percent or so that he’s getting in polls now. Presumably many of those voters are Party Loyalists, a group for whom he’s a good fit. Biden also has strong ratings among black voters, perhaps in part as a result of his being Barack Obama’s vice president — although his handling of the Anita Hill hearings and hawkish stance on criminal justice issues could give him problems among black voters if his record is subjected to greater scrutiny.

But where does Biden go after that? Could he gain support from The Left? Maybe a bit, but his dalliances with economic populism are more rhetorical than substantive; Biden’s voting record, and it’s a long one, is fairly centrist on economic policy. Could he win over Hispanic voters? Perhaps, as Hispanics sometimes back establishment-friendly nominees (like John Kerry in 2004), but Biden’s home state, Delaware, doesn’t have very many Hispanic voters (it has quite a few African-Americans, by contrast) and I’m less willing to give credit to a politician who hasn’t historically had to develop a relationship with a minority constituency. Still, a (Hillary) Clintonian constituency of Party Loyalists, black and Hispanic voters is probably Biden’s best bet.

When I originally conceived this article, I’d planned on splitting the Democratic electorate into three rather than five groups, which I’d roughly thought of as “white Hillary Democrats,” “white Bernie Democrats” and “nonwhite Democrats.” You can probably see why I abandoned that framework. One of the problems with it is that it groups blacks, Hispanics and other racial minorities together when (as in 2008) they sometimes gravitate toward different candidates.

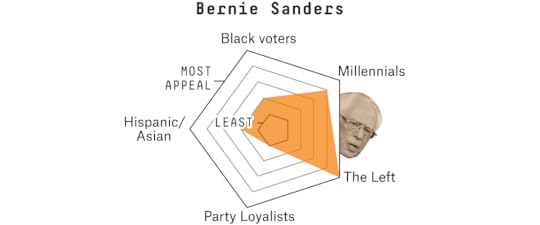

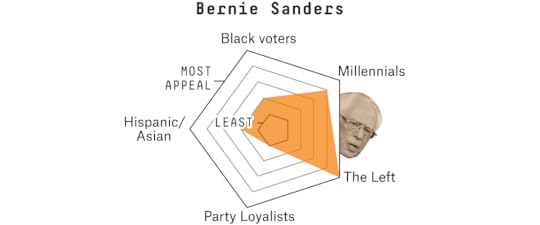

But another problem is that what I had thought of as “white Bernie voters” is also really two different groups: Voters who belong to The Left and those who belong with the Millennials and Friends group. In 2016, Sanders got slightly more than 40 percent of the Democratic vote nationally, which corresponds to winning clear majorities of those two groups, plus making some inroads with younger black and Hispanic voters later on in the campaign. This year, he’s polling at a little less than 20 percent. The most obvious interpretation is that, while Sanders has held on to much of his support on The Left, millennials were mostly just looking for an alternative to Clinton, and they are now considering abandoning Sanders for younger, flashier alternatives such as Beto O’Rourke and Kamala Harris.

So how does Sanders form a winning coalition? He probably does need the millennials to return to his camp, which might happen if the field narrows and his major competition is, say, Joe Biden — but it would be trickier against a Beto or a Harris or a Cory Booker. (Hence the Beto-Bernie wars.) And finding a third coalition partner is even trickier. Party Loyalists are liable to be bitter over his treatment of Clinton in 2016 and over the fact that Sanders is not actually a Democrat. Even groups such as unions — important bridges between The Left and the establishment — have been hesitant to support Sanders’s candidacy.

As for black and Hispanic voters, maybe Sanders can hope that his weak performance among those groups in 2016 was more a matter of Clinton’s strengths than his own liabilities. Sanders’s favorability ratings are reasonably good among black and Hispanic voters, in fact. But a recent survey of influential women of color found very little support for Sanders — and in contrast to four years ago, he’s now running in a field that will likely contain a number of black and Hispanic candidates. Overall, Sanders looks like a candidate with a high floor but a low ceiling, and one who would probably benefit from the field remaining divided for as long as possible.

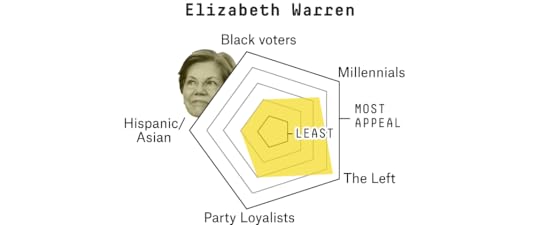

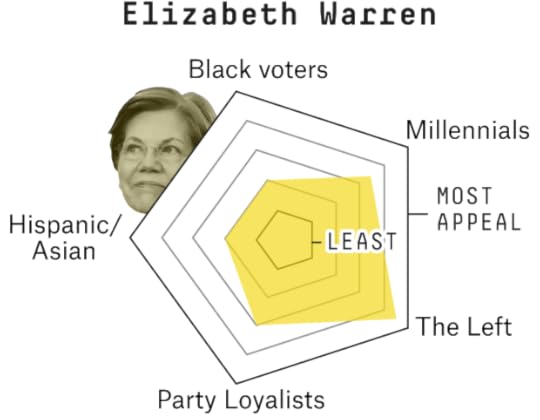

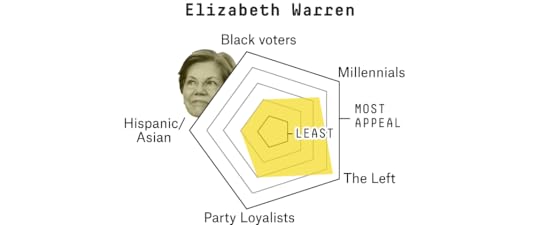

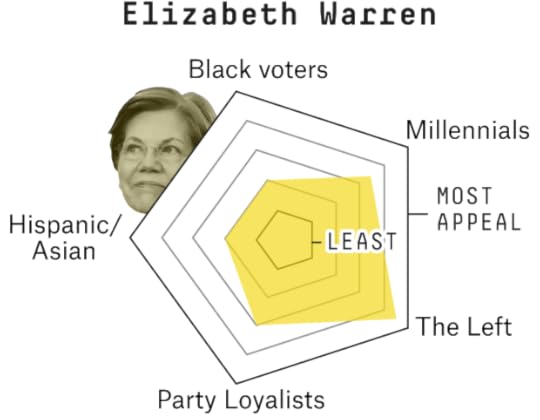

Warren has somewhat similar problems to Sanders, including having to build a relationship with black and Hispanic voters after being elected from an extremely white state — and having already made a misstep on issues of racial identity when she took a DNA test to “prove” she had Native American ancestry.

But she potentially has a higher ceiling because she’s more likely to win support from Party Loyalists, given that she’s a Democrat rather than an independent, and that she doesn’t have baggage from 2016. She’s also ever-so-slightly to Sanders’s right in a way that places her closer to the median Democratic voter.

The most likely winning coalition for Warren, in fact, probably involves the three predominately white groups: The Left, Party Loyalists and Millennials and Friends. (One of the things that helps her with millennials is that Warren has a bigger and better social media presence than you might assume.) Her path is tricky; she probably needs Sanders to founder. And that’s before getting into the gender dynamics surrounding her campaign and whether misogyny might hurt her chances. But she has a head start, having been the first of the big names to take official steps toward running and having hired key staffers in Iowa and elsewhere, which could give her more time to figure out a winning approach.

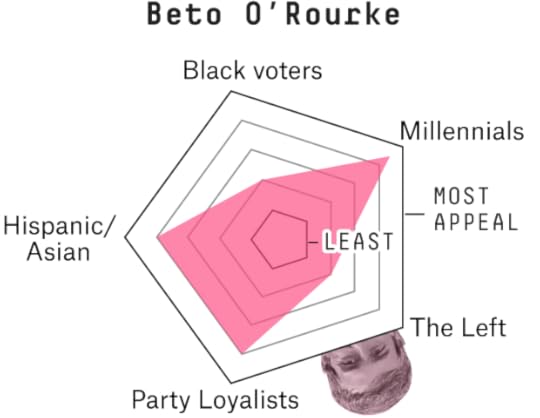

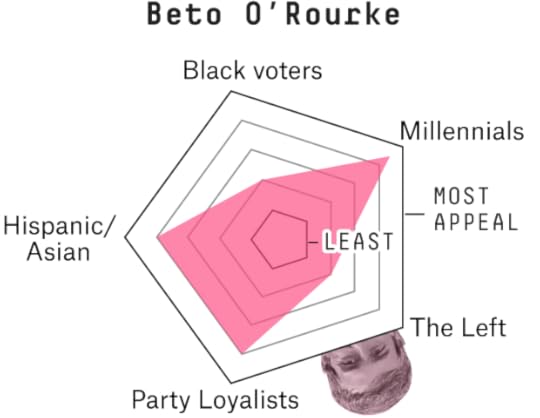

O’Rourke has one of the more obvious three-pronged coalitions: He’d hope to win on the basis of support from Millenials and Friends, Party Loyalists and Hispanics. The groups might support him for somewhat different reasons, and O’Rourke won’t win any of them without a fight, but he has a clearer path than the other Democrats we’ve mentioned so far.

O’Rourke really did help to motivate a surge in young voter turnout in his Texas Senate race last year; voters aged 18-29 were 16 percent of the electorate in 2018 as compared to 13 percent in the previous midterm in 2014. And overall turnout was up 80 percent as compared with 2014. O’Rourke won young voters overwhelmingly, whereas in 2014, Democratic nominee David Alameel had actually lost that group to Republican incumbent John Cornyn. O’Rourke also has one of the better social media presences among the Democratic contenders.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party establishment has been encouraging O’Rourke to run, presumably because they see him as electable and potentially able to raise gargantuan sums of money for the party. Electability is a fuzzy concept, and one should be careful not to let “electable” become a synonym for “good-looking white guy” and vice versa. With that said, O’Rourke’s performance in Texas was quite strong relative to the partisanship of the state — even though he lost to Ted Cruz (by just under 3 percentage points), it was the best performance for a Democrat in a high-profile statewide Texas race in years. His policy views are a bit squishy, but that could also be an advantage of a sort — the same could be said of Obama in 2008 and Trump in 2016.

There’s liable to be a Big Discussion at some point about Beto’s authenticity among Hispanic voters. O’Rourke has a , Beto, but his given first name is Robert and he doesn’t actually have any Hispanic ancestry. With that said, he represented a district in El Paso that is almost 80 percent Hispanic, and he beat an incumbent Hispanic Democrat to first win the seat in 2012. He also won 64 percent of the Hispanic vote against Cruz (who is Cuban-American2), which is pretty good in a state where the Hispanic vote can be more conservative than in other parts of the country. (Alameel won just 47 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2014, by contrast.)

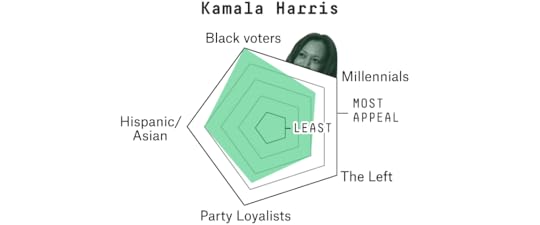

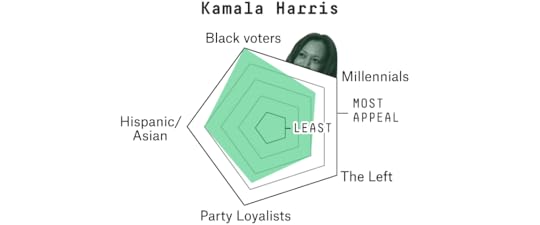

The candidate who looks best according to the coalition-building model is probably not O’Rourke, however. Instead, it’s California Sen. Kamala Harris, who potentially has strength with all five groups.

Harris, who is of mixed Jamaican (black) and Indian descent, was easily the top choice in the survey of influential women of color that I mentioned earlier. So while I don’t automatically want to assume that nonwhite candidates will necessarily win over voters who share their racial background — it took Obama some time to persuade African-Americans to vote for him in 2008 — Harris seems to be off to a pretty good head start. And her coalition not only includes black voters, but also potentially Asian and Hispanic voters. Harris did narrowly lose Hispanic voters to Sanchez, a Hispanic Democrat, in 2016 (while winning handily among Asian voters). But her approval ratings among Hispanic voters are high in California, a state where the group makes up around a third of the electorate.

If black voters and the Hispanic/Asian group constitute Harris’s first two building blocks, she’d then be able to decide which of the three remaining (predominately white) Democratic groups to target to complete her trifecta. And you could make the case for any of the three. Harris polls better among well-informed voters, which could suggest strength among Party Loyalists. She’s young-ish (54 years old) and has over 1 million Instagram followers, which implies potential strength among millennials. (And remember, Democratic millennials highly value racial diversity.) Harris’s worst group — despite a highly liberal, anti-Trump voting record — might actually be The Left, the whitest and most male group, from which she’s drawn occasional criticism for her decisions as a prosecutor and a district attorney.

Overall, however, this is a strong position for Harris. As Slate’s Jamelle Bouie points out, it may actually be a strategic advantage to be a black candidate in this Democratic primary in 2020.

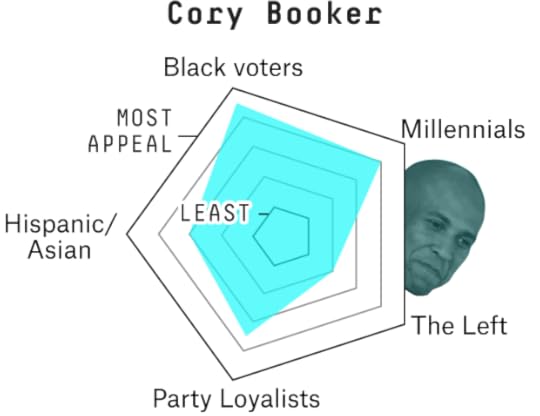

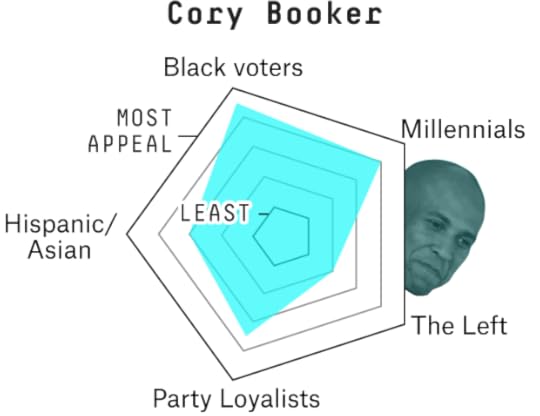

If Harris rates strongly by this system, then it might follow that New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who is also black, would look strong as well. Indeed, Booker may be somewhat overlooked by the pundit class. He’s been pretty explicit about the fact that he’s eventually going to run for the nomination. And he scored strong favorability ratings in a recent survey of Iowa voters, although he isn’t yet many voters’ first choice.

With that said, there are a couple of areas in which Booker could fall a bit short of Harris. New Jersey doesn’t have as many Hispanic or Asian voters as California does (and Booker isn’t part Asian, as Harris is). And if The Left has some problems with Harris, it’s liable to have a lot of problems with Booker, who many leftists see as being too close to Wall Street and to big business. Winning on the basis of a coalition of black voters, Party Loyalists and Millennials and Friends is certainly plausible for Booker, but he doesn’t have quite as many options as Harris does.

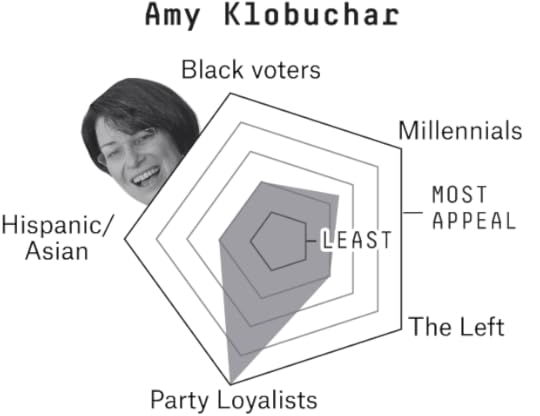

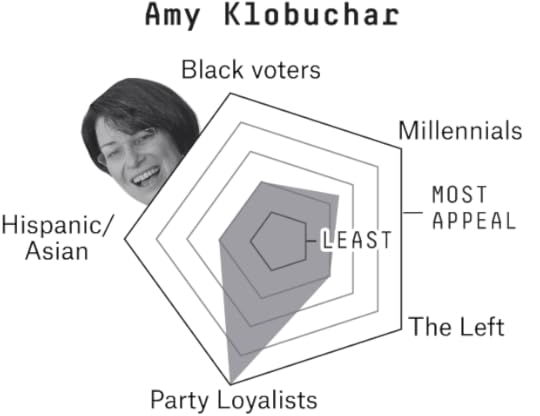

As I said earlier, I don’t think this five-corners metric is the only way to judge the candidates. And there are other heuristics by which Klobuchar, the Minnesota senator, might be better positioned. For instance, if Democrats are looking for a candidate who forms the best contrast to Trump, she has a pretty good case, as a woman from the Midwest who comes across as temperamentally moderate and without a lot of Trumpian bombast.

But I’m not quite sure how she builds a winning coalition. Klobuchar is potentially a near-perfect choice for Party Loyalists, who are liable to see her Midwestern moderation as being highly electable, especially after she won her Senate race by 24 percentage points last year in a state where Trump nearly defeated Clinton. Beyond that, though? Minnesota is a pretty white state, so Klobuchar doesn’t have a lot of practice at appealing to black, Hispanic or Asian voters. Her voting record is fairly moderate — she’s voted with Trump about twice as often as Booker has, for example — so she’s not an obvious fit for The Left. Millennials, perhaps? Her social media metrics so far are paltry — she has just 140,000 Twitter followers, for example — although (not totally unlike Warren) she has a goofy relatability that could translate well to Instagram and so on.

Klobuchar’s chances probably depend more on “The Party Decides” view of the primary than the more voter-centric vision I’ve presented here. In that view, party elites and Party Loyalists are leading indicators for how the rest of the party will eventually vote. One can imagine Klobuchar gaining traction if she performs well in Iowa, for instance. That’s a lot of “ifs,” however, whereas other candidates would seem to have more straightforward paths.

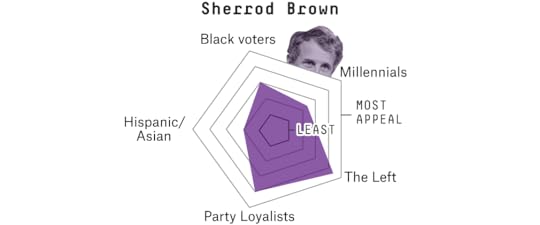

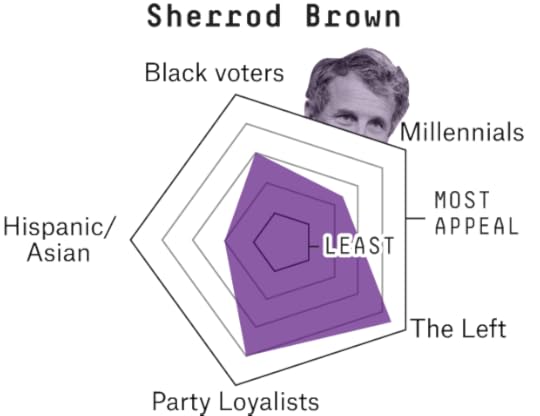

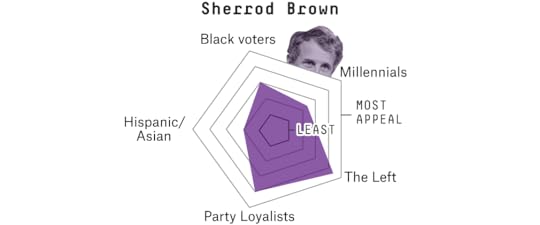

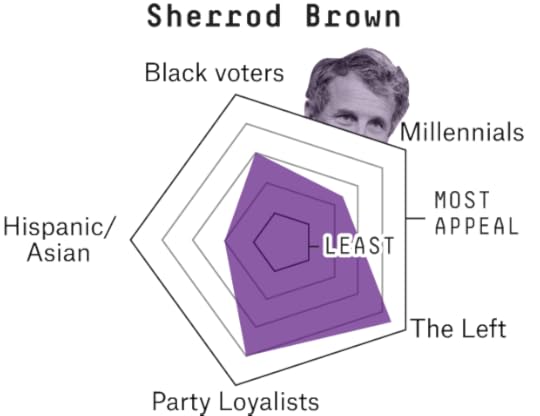

Another Midwestern senator, Ohio’s Sherrod Brown, in some ways has a more obvious route toward building a coalition. Like Klobuchar, he can make some good arguments about electability, having been elected three times in an increasingly red state, potentially making him an appealing choice to Party Loyalists. But he’s also a tried-and-true economic populist, who would be able to build alliances with The Left, and he’s reportedly a top choice among labor unions.

Where Brown might pick up the third group for his coalition is harder to say. Ohio has a reasonably large black vote, so he may be able to appeal to African-American voters. His limited social media presence and rumpled demeanor wouldn’t seem to make him a natural fit for millenials, although rumpledness didn’t stop Sanders from gaining traction with millennials four years ago. Domestic violence allegations against Brown, stemming from his divorce in 1986, have historically not moved the needle against him in his Ohio campaigns but could be a concern to younger voters, especially younger women, if they’re litigated on the national stage.

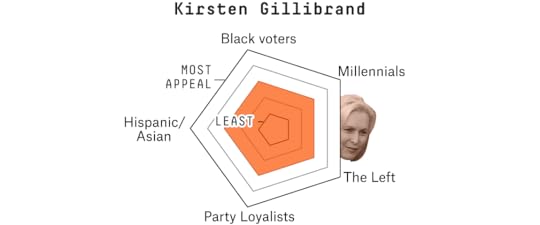

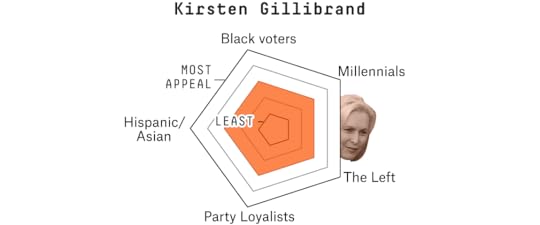

Gillibrand, who looks increasingly likely to run, sometimes gives the impression of having conducted an analysis like the one you’re reading in this article and taking a color-by-number approach to the Democratic primary. But it can come out a bit awkwardly. On the one hand, Gillibrand has the lowest Trump Score of any senator, meaning that she has opposed Trump more often than any other Democrat in the upper chamber. On the other hand, she once took relatively conservative stances on gun control, immigration and other issues when serving in Congress as a representative from upstate New York. On the one hand, she uses leftist and feminist terms such as “intersectional” to describe how she sees the future. On the other hand, she has ties to Wall Street (as many New York Democrats do).

Gillibrand’s most natural path might be to start with Party Loyalists and build out a coalition from there. But her calls for Sen. Al Franken to resign — issued after several women accused him of groping them — reportedly triggered a backlash among some donor-class Democrats, who [warning, editorial comment ahead] apparently don’t care how stupid they look for blaming a woman for a man’s #MeToo problems.

With all that said, Gillibrand potentially has a reasonably high ceiling. In New York state, she has high favorability ratings among nonwhite voters and an especially large gender gap in how voters view her. So if she isn’t getting a lot of buzz among white male Democratic pundits, you should be a little bit wary about concluding that the lack of buzz is representative of the broader Democratic coalition.

We’re getting toward the end of what you might consider the top couple of tiers of Democratic candidates. And I’m not quite sure whether to consider Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio and former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, as one of the frontrunners or as more of a long-shot candidate. In the recent Selzer/Des Moines Register poll of Iowa, almost two-thirds of likely Democratic caucusgoers didn’t have an opinion about Castro either way. And neither his tenure as mayor nor his job as HUD Secretary necessarily required him to weigh in on the major issues of the day. So for better or worse, he’s starting out with a relatively blank slate and a malleable policy platform.

Castro does have the advantage of being potentially the only Hispanic candidate in the race. He’s a good speaker, having given the keynote address at the 2012 Democratic convention. And he’s been relatively explicit about his desire to run — he may even officially declare his intentions in the next few days. A coalition of Hispanics, Party Loyalists (if he can persuade party elites about the importance of the Hispanic vote) and Millenials and Friends might be Castro’s best option. As it happens, that’s also O’Rourke’s coalition, so the two Texans could represent a problem for one another.

There’s about an 80 percent chance that the Democratic nominee will be one of the 10 candidates I just mentioned, according to betting markets. Still, that does leave some room for a long shot, and there are literally dozens of other Democrats who are contemplating a presidential bid. There are also some candidates, such as Georgia’s Stacey Abrams, who don’t seem especially likely to run, but who could be formidable if they did. We’ll cover some of those other Democrats in “lightning round” fashion in a third and final installment of this series later this week.

Why Kamala And Beto Have More Upside Than Joe And Bernie

Last week, we introduced a method for evaluating Democratic presidential contenders, which focused on their ability to build a coalition among key constituencies within the party. In particular, our method claims there are five essential groups of Democratic voters, which we describe as:

Party Loyalists, who are mostly older, lifelong Democrats who care about experience and electability.

The Left.

Millennials and Friends, who are young, cosmopolitan and social-media-savvy.

Black voters.

And Hispanic voters, who for some purposes can be grouped together with Asian voters.

The goal is for candidates to form a coalition consisting of at least three of the five groups.

I certainly wouldn’t claim that this is the only way to evaluate the field; rather, it’s part of what we hope will be a fairly broad toolkit of approaches that we’ll be applying as we cover the Democratic candidates at FiveThirtyEight over the course of the next 18(!!) months.1 Furthermore, in reality, the various ideological and demographic constituencies within the Democratic Party are more fluid than this analysis implies. Nonetheless, it has influenced my thinking — the coalition-building model has made me more skeptical about the chances for Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden and Amy Klobuchar, for instance, but more bullish about Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke and Cory Booker. In this article, I’ll go through a set of 10 leading contenders and map out their potential winning coalitions; we’ll tackle some of the long-shot candidates later on this week.

Let’s start with the man who has led most polls of the Democratic field so far, former Vice President Joe Biden. One lesson from the 2016 Republican primary might be to approach the polls with more humility. If a candidate is ahead in the polls for a sustained period of time — as Trump was for much of late 2015 and early 2016 — maybe we journalists ought to give a certain amount of credit to that, rather than just chalking it up to high name recognition or becoming overly wedded to some theory about how voters are “supposed” to behave.

With that said, there are some trouble signs for Biden. He performs worse among those voters who are paying the most attention to the primary, suggesting that his high name recognition compared to most other candidates is a significant factor in his lead.

And I’m not sure it’s going to be very easy for Biden to expand his coalition beyond the 25 percent or so that he’s getting in polls now. Presumably many of those voters are Party Loyalists, a group for whom he’s a good fit. Biden also has strong ratings among black voters, perhaps in part as a result of his being Barack Obama’s vice president — although his handling of the Anita Hill hearings and hawkish stance on criminal justice issues could give him problems among black voters if his record is subjected to greater scrutiny.

But where does Biden go after that? Could he gain support from The Left? Maybe a bit, but his dalliances with economic populism are more rhetorical than substantive; Biden’s voting record, and it’s a long one, is fairly centrist on economic policy. Could he win over Hispanic voters? Perhaps, as Hispanics sometimes back establishment-friendly nominees (like John Kerry in 2004), but Biden’s home state, Delaware, doesn’t have very many Hispanic voters (it has quite a few African-Americans, by contrast) and I’m less willing to give credit to a politician who hasn’t historically had to develop a relationship with a minority constituency. Still, a (Hillary) Clintonian constituency of Party Loyalists, black and Hispanic voters is probably Biden’s best bet.

When I originally conceived this article, I’d planned on splitting the Democratic electorate into three rather than five groups, which I’d roughly thought of as “white Hillary Democrats,” “white Bernie Democrats” and “nonwhite Democrats.” You can probably see why I abandoned that framework. One of the problems with it is that it groups blacks, Hispanics and other racial minorities together when (as in 2008) they sometimes gravitate toward different candidates.

But another problem is that what I had thought of as “white Bernie voters” is also really two different groups: Voters who belong to The Left and those who belong with the Millennials and Friends group. In 2016, Sanders got slightly more than 40 percent of the Democratic vote nationally, which corresponds to winning clear majorities of those two groups, plus making some inroads with younger black and Hispanic voters later on in the campaign. This year, he’s polling at a little less than 20 percent. The most obvious interpretation is that, while Sanders has held on to much of his support on The Left, millennials were mostly just looking for an alternative to Clinton, and they are now considering abandoning Sanders for younger, flashier alternatives such as Beto O’Rourke and Kamala Harris.

So how does Sanders form a winning coalition? He probably does need the millennials to return to his camp, which might happen if the field narrows and his major competition is, say, Joe Biden — but it would be trickier against a Beto or a Harris or a Cory Booker. (Hence the Beto-Bernie wars.) And finding a third coalition partner is even trickier. Party Loyalists are liable to be bitter over his treatment of Clinton in 2016 and over the fact that Sanders is not actually a Democrat. Even groups such as unions — important bridges between The Left and the establishment — have been hesitant to support Sanders’s candidacy.

As for black and Hispanic voters, maybe Sanders can hope that his weak performance among those groups in 2016 was more a matter of Clinton’s strengths than his own liabilities. Sanders’s favorability ratings are reasonably good among black and Hispanic voters, in fact. But a recent survey of influential women of color found very little support for Sanders — and in contrast to four years ago, he’s now running in a field that will likely contain a number of black and Hispanic candidates. Overall, Sanders looks like a candidate with a high floor but a low ceiling, and one who would probably benefit from the field remaining divided for as long as possible.

Warren has somewhat similar problems to Sanders, including having to build a relationship with black and Hispanic voters after being elected from an extremely white state — and having already made a misstep on issues of racial identity when she took a DNA test to “prove” she had Native American ancestry.

But she potentially has a higher ceiling because she’s more likely to win support from Party Loyalists, given that she’s a Democrat rather than an independent, and that she doesn’t have baggage from 2016. She’s also ever-so-slightly to Sanders’s right in a way that places her closer to the median Democratic voter.

The most likely winning coalition for Warren, in fact, probably involves the three predominately white groups: The Left, Party Loyalists and Millennials and Friends. (One of the things that helps her with millennials is that Warren has a bigger and better social media presence than you might assume.) Her path is tricky; she probably needs Sanders to founder. And that’s before getting into the gender dynamics surrounding her campaign and whether misogyny might hurt her chances. But she has a head start, having been the first of the big names to take official steps toward running and having hired key staffers in Iowa and elsewhere, which could give her more time to figure out a winning approach.

O’Rourke has one of the more obvious three-pronged coalitions: He’d hope to win on the basis of support from Millenials and Friends, Party Loyalists and Hispanics. The groups might support him for somewhat different reasons, and O’Rourke won’t win any of them without a fight, but he has a clearer path than the other Democrats we’ve mentioned so far.

O’Rourke really did help to motivate a surge in young voter turnout in his Texas Senate race last year; voters aged 18-29 were 16 percent of the electorate in 2018 as compared to 13 percent in the previous midterm in 2014. And overall turnout was up 80 percent as compared with 2014. O’Rourke won young voters overwhelmingly, whereas in 2014, Democratic nominee David Alameel had actually lost that group to Republican incumbent John Cornyn. O’Rourke also has one of the better social media presences among the Democratic contenders.

Meanwhile, the Democratic Party establishment has been encouraging O’Rourke to run, presumably because they see him as electable and potentially able to raise gargantuan sums of money for the party. Electability is a fuzzy concept, and one should be careful not to let “electable” become a synonym for “good-looking white guy” and vice versa. With that said, O’Rourke’s performance in Texas was quite strong relative to the partisanship of the state — even though he lost to Ted Cruz (by just under 3 percentage points), it was the best performance for a Democrat in a high-profile statewide Texas race in years. His policy views are a bit squishy, but that could also be an advantage of a sort — the same could be said of Obama in 2008 and Trump in 2016.

There’s liable to be a Big Discussion at some point about Beto’s authenticity among Hispanic voters. O’Rourke has a , Beto, but his given first name is Robert and he doesn’t actually have any Hispanic ancestry. With that said, he represented a district in El Paso that is almost 80 percent Hispanic, and he beat an incumbent Hispanic Democrat to first win the seat in 2012. He also won 64 percent of the Hispanic vote against Cruz (who is Cuban-American2), which is pretty good in a state where the Hispanic vote can be more conservative than in other parts of the country. (Alameel won just 47 percent of the Hispanic vote in 2014, by contrast.)

The candidate who looks best according to the coalition-building model is probably not O’Rourke, however. Instead, it’s California Sen. Kamala Harris, who potentially has strength with all five groups.

Harris, who is of mixed Jamaican (black) and Indian descent, was easily the top choice in the survey of influential women of color that I mentioned earlier. So while I don’t automatically want to assume that nonwhite candidates will necessarily win over voters who share their racial background — it took Obama some time to persuade African-Americans to vote for him in 2008 — Harris seems to be off to a pretty good head start. And her coalition not only includes black voters, but also potentially Asian and Hispanic voters. Harris did narrowly lose Hispanic voters to Sanchez, a Hispanic Democrat, in 2016 (while winning handily among Asian voters). But her approval ratings among Hispanic voters are high in California, a state where the group makes up around a third of the electorate.

If black voters and the Hispanic/Asian group constitute Harris’s first two building blocks, she’d then be able to decide which of the three remaining (predominately white) Democratic groups to target to complete her trifecta. And you could make the case for any of the three. Harris polls better among well-informed voters, which could suggest strength among Party Loyalists. She’s young-ish (54 years old) and has over 1 million Instagram followers, which implies potential strength among millennials. (And remember, Democratic millennials highly value racial diversity.) Harris’s worst group — despite a highly liberal, anti-Trump voting record — might actually be The Left, the whitest and most male group, from which she’s drawn occasional criticism for her decisions as a prosecutor and a district attorney.

Overall, however, this is a strong position for Harris. As Slate’s Jamelle Bouie points out, it may actually be a strategic advantage to be a black candidate in this Democratic primary in 2020.

If Harris rates strongly by this system, then it might follow that New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker, who is also black, would look strong as well. Indeed, Booker may be somewhat overlooked by the pundit class. He’s been pretty explicit about the fact that he’s eventually going to run for the nomination. And he scored strong favorability ratings in a recent survey of Iowa voters, although he isn’t yet many voters’ first choice.

With that said, there are a couple of areas in which Booker could fall a bit short of Harris. New Jersey doesn’t have as many Hispanic or Asian voters as California does (and Booker isn’t part Asian, as Harris is). And if The Left has some problems with Harris, it’s liable to have a lot of problems with Booker, who many leftists see as being too close to Wall Street and to big business. Winning on the basis of a coalition of black voters, Party Loyalists and Millennials and Friends is certainly plausible for Booker, but he doesn’t have quite as many options as Harris does.

As I said earlier, I don’t think this five-corners metric is the only way to judge the candidates. And there are other heuristics by which Klobuchar, the Minnesota senator, might better positioned. For instance, if Democrats are looking for a candidate who forms the best contrast to Trump, she has a pretty good case, as a woman from the Midwest who comes across as temperamentally moderate and without a lot of Trumpian bombast.

But I’m not quite sure how she builds a winning coalition. Klobuchar is potentially a near-perfect choice for Party Loyalists, who are liable to see her Midwestern moderation as being highly electable, especially after she won her Senate race by 24 percentage points last year in a state where Trump nearly defeated Clinton. Beyond that, though? Minnesota is a pretty white state, so Klobuchar doesn’t have a lot of practice at appealing to black, Hispanic or Asian voters. Her voting record is fairly moderate — she’s voted with Trump about twice as often as Booker has, for example — so she’s not an obvious fit for The Left. Millennials, perhaps? Her social media metrics so far are paltry — she has just 140,000 Twitter followers, for example — although (not totally unlike Warren) she has a goofy relatability that could translate well to Instagram and so on.

Klobuchar’s chances probably depend more on “The Party Decides” view of the primary than the more voter-centric vision I’ve presented here. In that view, party elites and Party Loyalists are leading indicators for how the rest of the party will eventually vote. One can imagine Klobuchar gaining traction if she performs well in Iowa, for instance. That’s a lot of “ifs,” however, whereas other candidates would seem to have more straightforward paths.

Another Midwestern senator, Ohio’s Sherrod Brown, in some ways has a more obvious route toward building a coalition. Like Klobuchar, he can make some good arguments about electability, having been elected three times in an increasingly red state, potentially making him an appealing choice to Party Loyalists. But he’s also a tried-and-true economic populist, who would be able to build alliances with The Left, and he’s reportedly a top choice among labor unions.

Where Brown might pick up the third group for his coalition is harder to say. Ohio has a reasonably large black vote, so he may be able to appeal to African-American voters. His limited social media presence and rumpled demeanor wouldn’t seem to make him a natural fit for millenials, although rumpledness didn’t stop Sanders from gaining traction with millennials four years ago. Domestic violence allegations against Brown, stemming from his divorce in 1986, have historically not moved the needle against him in his Ohio campaigns but could be a concern to younger voters, especially younger women, if they’re litigated on the national stage.

Gillibrand, who looks increasingly likely to run, sometimes gives the impression of having conducted an analysis like the one you’re reading in this article and taking a color-by-number approach to the Democratic primary. But it can come out a bit awkwardly. On the one hand, Gillibrand has the lowest Trump Score of any senator, meaning that she has opposed Trump more often than any other Democrat in the upper chamber. On the other hand, she once took relatively conservative stances on gun control, immigration and other issues when serving in Congress as a representative from upstate New York. On the one hand, she uses leftist and feminist terms such as “intersectional” to describe how she sees the future. On the other hand, she has ties to Wall Street (as many New York Democrats do).

Gillibrand’s most natural path might be to start with Party Loyalists and build out a coalition from there. But her calls for Sen. Al Franken to resign — issued after several women accused him of groping them — reportedly triggered a backlash among some donor-class Democrats, who [warning, editorial comment ahead] apparently don’t care how stupid they look for blaming a woman for a man’s #MeToo problems.

With all that said, Gillibrand potentially has a reasonably high ceiling. In New York state, she has high favorability ratings among nonwhite voters and an especially large gender gap in how voters view her. So if she isn’t getting a lot of buzz among white male Democratic pundits, you should be a little bit wary about concluding that the lack of buzz is representative of the broader Democratic coalition.

We’re getting toward the end of what you might consider the top couple of tiers of Democratic candidates. And I’m not quite sure whether to consider Castro, the former mayor of San Antonio and former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, as one of the frontrunners or as more of a long-shot candidate. In the recent Selzer/Des Moines Register poll of Iowa, almost two-thirds of likely Democratic caucusgoers didn’t have an opinion about Castro either way. And neither his tenure as mayor nor his job as HUD Secretary necessarily required him to weigh in on the major issues of the day. So for better or worse, he’s starting out with a relatively blank slate and a malleable policy platform.

Castro does have the advantage of being potentially the only Hispanic candidate in the race. He’s a good speaker, having given the keynote address at the 2012 Democratic convention. And he’s been relatively explicit about his desire to run — he may even officially declare his intentions in the next few days. A coalition of Hispanics, Party Loyalists (if he can persuade party elites about the importance of the Hispanic vote) and Millenials and Friends might be Castro’s best option. As it happens, that’s also O’Rourke’s coalition, so the two Texans could represent a problem for one another.

There’s about an 80 percent chance that the Democratic nominee will be one of the 10 candidates I just mentioned, according to betting markets. Still, that does leave some room for a long shot, and there are literally dozens of other Democrats who are contemplating a presidential bid. There are also some candidates, such as Georgia’s Stacey Abrams, who don’t seem especially likely to run, but who could be formidable if they did. We’ll cover some of those other Democrats in “lightning round” fashion in a third and final installment of this series later this week.

January 10, 2019

The 5 Corners Of The 2020 Democratic Primary

Graphics by Rachael Dottle

Over the long course of the Republican presidential nomination process in 2015 and 2016, we frequently featured a diagram called “The Republicans’ Five-Ring Circus.” The chart was based on the idea that the GOP essentially consisted of five different constituencies: the establishment wing, the moderate wing, the tea party, libertarians and Christian conservatives. Each presidential candidate’s goal was to dominate his or her constituency or “lane” (for example, Rand Paul would have been looking to win libertarians, or Jeb Bush to win establishment voters), and then unify with the other constituencies to claim the Republican nomination.

Except it didn’t exactly work out that way. Donald Trump, a candidate who didn’t fit neatly into any of the lanes, won instead.

In retrospect, President Trump had a fair amount in common with the tea party movement — we sometimes placed him there in the chart, and sometimes put him outside of the five circles entirely. But he was really running as more of a mix of a tea party populist on issues such as immigration1 and a Northeastern moderate on economic policy. (In Pennsylvania, for instance, Trump did just as well with self-described moderate voters as with conservatives.) Problematically, our five-ring circus chart didn’t even consider the possibility of candidate who overlapped between the moderate wing and the tea party wings of the GOP. Trump also won over a significant number of evangelical voters, even though he had not exactly abided by a “family values” lifestyle, nor did he make a particular priority of issues such as abortion.

So for the 2020 Democratic nomination, we’ve resolved to entertain multiple hypotheses about the contest simultaneously. Perhaps the party will decide, and so we should be looking at how much support each candidate has from party elites. Perhaps the candidate most dissimilar to Trump will win, and so we should be evaluating the candidates based on that criteria. Perhaps the primary is just so hard to forecast that you might as well look at the polling, crude as it might be. (It has more predictive power than you might think.)

We’ll see. But we nonetheless think that (despite its mixed success in 2016) the coalition-building model is also a useful tool, especially if we make a few tweaks to how we applied it four years ago.

Just as with the Republicans in 2016, the concept this time around involves considering five key groups of Democratic voters. Here are those groups:

Party Loyalists

The Left

Millennials and Friends

Black voters

Hispanic voters (sometimes in combination with Asian voters)

You’ll notice that these groups aren’t mutually exclusive. A 26-year-old Latina who identifies as a democratic socialist would belong to groups 2, 3 and 5, for example. There might be modest tension between some of the groups — for instance, between Party Loyalists and The Left — but it’s possible to imagine candidates who appeal to voters in both of those constituencies. (Ohio’s Sherrod Brown or Massachusetts’s Elizabeth Warren might appeal to both The Left and Party Loyalist voters, for example.) Indeed, whichever candidate wins the Democratic nomination is going to have at least some buy-in from all five groups, even if some groups don’t buy in beyond considering the nominee the lesser of two evils against Trump.

So rather than thinking about “lanes,” we’re taking a more pluralistic approach with the Democrats. Candidates don’t have to pick any one group; rather, their goal is to build a majority coalition from voters in (at least) three out of the five groups. There are a lot of ways to do this: If you’re choosing any three from among the five groups, there are 10 possible combinations to pick from,2 and all of them plausibly form winning coalitions. In 2016, for example, Hillary Clinton assembled a coalition of Party Loyalists, black voters and Hispanic voters, largely ceding the other two groups to Bernie Sanders, but still winning the nomination with room to spare.

The other difference from how we handled the Republicans four years ago is that, with the exception of The Left, none of these groups are explicitly ideological in nature. That’s not to say that they don’t have somewhat different priorities; millennials might place more of an emphasis on the environment than the other groups do, for example. But these groups encompass a mishmash of ideology and identity. They’re chosen because they represent the dividing lines in recent Democratic Party primaries — but they don’t necessarily span a clear spectrum from left to right.

One obvious question you might have before we proceed further: Why aren’t women one of the groups? The answer is that women represent almost 60 percent of the Democratic primary electorate3 and so they’re a major portion of all of these groups. In fact, women are likely the majority of all of these groups, with the possible exception of The Left, which skews male. So when you think of a default voter from one of these groups, you should probably think of a woman.

Since this is really my first major foray into analyzing the 2020 Democratic presidential derby — I’ve had a lot of thoughts percolating about the candidates, but haven’t really put them to paper before — I’m going to take some time with it. In this article, I’ll lay out the five groups, how they’ve voted in the past, and what they might be looking for this time around. Next week, we’ll follow up with another couple stories that lay out my thoughts on individual candidates — although the big honkin’ graphic you see below provides some teasers about how some potential contenders measure up.

As a final warning, while you’ll see plenty of polling and other empirical evidence cited in this analysis, it definitely reflects a mix of art and science. It’s early, and there isn’t all that much hard data yet. Some patterns from past nominations will hold and others will not. Unavoidably, some of this is going to look silly a year from now (and probably even a few weeks from now). Just know that if I missed something that gives Minnesota senator Amy Klobuchar an obvious appeal to Hispanic voters, or that allows New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu to rise from relative obscurity to win the nomination, everyone else back when I was writing this probably did too.

Group 1. Party Loyalists

Demographic profile: Mostly older, white and upper-middle class. And mostly women. Many are politically active and count themselves as members of the #Resistance. As a rough guide, Party Loyalists probably represent around 30 percent of the Democratic electorate; in the Illinois Democratic primary in 2016, for example,4 about 30 percent of voters selected “experience” or “electability” as their top candidate quality and voted for Clinton rather than Sanders.

What they value in a candidate: These voters are capital-D Democrats who care about the fate of the Democratic Party and generally go along with what party elites want. They tend to trust established brands, although they also care a lot about electability.

Ideological preferences: On economic policy, Party Loyalists can span a reasonably wide range, but they’re certainly more liberal than left — that is, while they may favor substantial changes to the system, they don’t want to completely remake the American economy. With that said, the Democratic Party’s platform has shifted to the left overall, and Party Loyalists aren’t the type to buck the consensus on, say, a higher minimum wage. On social and cultural issues, Party Loyalists hold conventionally liberal attitudes, being strong supporters of abortion rights and gay marriage and gun control — but being older and mostly white, they sometimes regard the other groups as too radical on issues related to race.

Who they supported in recent Democratic primaries: Party Loyalists supported Hillary Clinton in 2016 and for the most part also supported Clinton in 2008, although with a fair number of defections to Barack Obama. But they’re usually on the winning side of the primaries; they supported John Kerry in 2004 and Al Gore in 2000.

Group 2. The Left

Demographic profile: Going by membership statistics in the Democratic Socialists of America, this is the most male and the whitest of the five Democratic groups, although it’s becoming more diverse, especially among younger voters. A fair number of voters in The Left are independents rather than Democrats. They’re mostly college-educated, though not necessarily wealthy. The Left is probably somewhere around 25 percent of the Democratic electorate. In the Illinois Democratic primary in 2016, for example, 27 percent of voters said that Clinton’s positions were not liberal enough, while 24 percent said the same in Ohio.

What they value in a candidate: This is the most ideologically driven of the Democratic groups. Most obviously, they want candidates who they think will pursue left-wing economic solutions, e.g. higher taxes on the wealthy, Medicare-for-all and free college tuition, perhaps as part of a “Green New Deal.” In a broader sense, The Left thinks the status quo is broken and that capitalism doesn’t work at all or at least needs to be managed with much more government intervention — so they prefer candidates who they think will upset the apple cart over those who merely promise to reform existing institutions. The Left doesn’t trust the establishment’s instincts on “electability” and considers Clinton’s nomination to have been a debacle.

Ideological preferences: See above on economic policy. On social policy, there are quite a few divisions within this group, with some (mostly younger and urban) left-wing voters holding more liberal and “intersectional” views on issues related to race and immigration and other (mostly older and rural) voters being more “populist” and even taking conservative stances on some of these issues. On foreign policy, The Left favors a smaller military and can be more isolationist than the other Democratic-leaning groups, and it is also suspicious of free-trade agreements.

Who they supported in recent Democratic primaries: They supported Howard Dean in 2004 and Bernie Sanders in 2016. It’s less clear what they did in 2008; some voters in The Left may have preferred John Edwards initially, and then would have been lukewarm toward both Clinton and Obama.

Group 3: Millennials and Friends

Demographic profile: By one definition, millennials were born between 1982 and 2004, meaning that they’ll be somewhere between 16 years old (and thus not yet eligible to vote) and 38 years old in 2020. Although youth turnout can vary from election to election, that will likely make them somewhere on the order of 30 percent of the Democratic primary electorate in 2020. Age is not always among the most important characteristics in predicting voting behavior, but there was a huge, glaring exception in 2016, with Sanders winning overwhelmingly among millennials but Clinton dominating among baby boomers. Apart from being young, this is the most racially diverse of the Democratic groups. Many think of themselves as independents rather than Democrats. By “Millenials and Friends,” I mean that there are some Democratic voters, especially in urban areas, who are too old to be millennials (they’re the “friends”) but whose cosmopolitanism makes them fit in better with the millenials than with any of the other groups.

What they value in a candidate: It isn’t entirely obvious, as the candidates they’ve been attracted to in different cycles (Sanders in 2016, Obama in 2008) don’t necessarily have an enormous amount in common with one another. But it’s safe to say that young voters prefer “change” candidates to the status quo, which would usually translate to younger rather than older politicians. As you might expect, this group’s media consumption habits are way different than those of older voters: Voters under 30 are about twice as likely to get their news online as through the television. And they turn out less reliably than older voters. So candidates hoping to win this group must be able to be able to attract and hold these voters’ attention via social media.

Ideological preferences: On average, millenials care about racial justice, access to education and environmental issues more than older Democratic voters do. Younger voters view socialism much more favorably than older ones do, but the story is more complicated than millennials simply being further to the left: Younger voters5 also have more favorable views of libertarianism than older ones do, for example. Put another way, millenials are less wedded to the dominant political philosophies and labels of the previous generation and are willing to consider a fairly wide range of alternatives to replace them.

Who they supported in recent Democratic primaries: They preferred Sanders in 2016 and Obama in 2008. Most millennials weren’t old enough to have voted in 2004, but Dean overperformed among those who did.

Group 4. Black voters

Demographic profile: Black voters represented 19 percent of people who voted for Democratic House candidates in 2018, according to the national exit poll — so conveniently enough (since we have five groups) they’re about one-fifth of the Democratic electorate. Black voters are poorer and younger than other Democrats on average, and about 60 percent of black voters in Democratic primaries are women.

What they value in a candidate: After sometimes fractious racial politics in the Democratic Party of the 1980s and 1990s, in recent years there’s been an implicit alliance between black voters and the Democratic Party establishment. That’s served the interests of both groups fairly well; of the five voting blocs I’ve mentioned here, black voters were the only ones to back the winning candidate in both 2008 (Obama) and 2016 (Clinton). They were also a key part of John Kerry’s winning coalition in 2004. Thus, like Party Loyalists, black voters have traditionally been pragmatic and have placed a high emphasis on electability, preferring candidates whose mettle has been tested. Even Obama had to overcome initial skepticism as he didn’t poll that well among black voters in 2007 and 2008 when the campaign first began. However, there’s an emerging generational split among African-Americans, as black voters under 30 narrowly backed Sanders over Clinton in 2016 despite overwhelming support for Clinton among older black voters.

Ideological preferences: Black voters have traditionally been more religious and more socially conservative than other Democrats, having been relatively slow to support gay marriage, for example. They’re generally liberal on economic policy, although there’s sometimes tension among black voters about candidates (such as Sanders) who are seen as emphasizing economic justice rather than racial justice. Again, however, there are important generational divides within the black community. Groups such as Color of Change have been more willing to endorse platforms that emphasize both social (e.g. voting rights and criminal justice) and economic (e.g. the minimum wage) priorities.

Who they supported in recent Democratic primaries: Black voters backed Kerry in 2004, Obama in 2008 and Clinton in 2016.

Group 5. Hispanic voters, sometimes in conjunction with Asian voters

Demographic profile: OK, a bit of explanation here. I’ve gone back and forth on whether to group Hispanic and Asian voters together. The case for doing so: Both groups are made up predominantly of relatively recent waves of immigrants to the U.S. and their descendents; Hispanic and Asian voters tend to be concentrated in the same states as one another (e.g. California); they prioritize similar issues (see below); voters in both groups are younger than average and have historically had low rates of voter registration and turnout; and Hispanics and Asians mostly voted similarly in recent Democratic primaries (backing Clinton in both 2008 and 2016). The case against: On average, Asian-Americans live in better economic circumstances than Hispanics (although there’s a lot of variation) and the two groups can sometimes split when there are black or Asian candidates on the ballot, as in the California Senate race in 2016, when Asian voters went overwhelmingly for Kamala Harris while Hispanics narrowly backed Loretta Sanchez. All things considered, Hispanic voters and Asian voters are likely to have correlated preferences, but in a field with a dozen or more candidates, it’s possible they won’t vote the same way. Hispanic voters are around 15 percent of the Democratic primary electorate and Asian voters are around 5 percent, so together, they make up about 20 percent of the vote, or roughly the same share as black voters.

What they value in a candidate: Because Hispanic and Asian voters were a small fraction of the electorate until recently, it’s hard to come to as many historically driven conclusions about their preferences. But Hispanic voters put a major emphasis on economic issues and generally favor a relatively high degree of government intervention in the economy (as do Asian voters). In that sense, they tend to be fairly pragmatic and solutions-driven voters, especially on pocketbook issues. And although immigration is important to these voters, issues related to health care, education and the economy consistently rate as higher priorities in surveys of both Hispanic and Asian-American voters.

Ideological preferences: As among black voters, there are important generational divides among Hispanics and Asians. For instance, many older Hispanic Democrats describe themselves as “moderate” or “conservative.” (For a long time, especially after George W. Bush performed comparatively well with Hispanic voters in 2004, the conventional wisdom was that they were center-right “family values” voters). Younger Hispanics tend to be more liberal, especially on social issues, by contrast. But both older and younger Hispanics have a highly negative view of the Republican Party and of Trump. Asian-American voters are similar to Hispanics in many respects, although they tend to be a bit more liberal on social issues. Both Hispanics and Asians favor a bigger government that provides more services.

Who they supported in recent Democratic primaries: Hispanic and Asian voters predominately backed Clinton in both 2008 and 2016. Hispanics were also an important part of Kerry’s coalition in 2004.

Next week, I’ll analyze individual candidates in more detail. But you can probably predict which candidates do relatively well according to this heuristic and which have a more challenging path. It’s easy to identify three or four groups within the party that Harris or Beto O’Rourke might have a lot of natural appeal to, for example. It’s harder to do the same for someone like Sanders.

January 7, 2019

Politics Podcast: Elizabeth Warren’s Path To The 2020 Nomination

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts became the most high-profile person to announce an exploratory committee to run for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew discusses her paths to winning — and losing — that contest. The team also looks at the political repercussions of the second-longest government shutdown in recent history.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

December 24, 2018

Politics Podcast: Our 2018 Politics Awards

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In this year-end installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew looks back on the year in politics and hands out awards for things like the worst politicking of 2018 and most surprising election result. They also make journalistic resolutions for the coming year.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

December 21, 2018

Emergency Politics Podcast: Mattis Is Out, Shutdown Is On (?)

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In an emergency installment of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew discusses Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis’s resignation and the looming government shutdown. Both events strain President Trump’s relationship with the congressional GOP and create uncertainty in Washington.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

December 19, 2018

How Should The Next Congress Deal With President Trump?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): We discussed last week how President Trump didn’t seem too keen on compromising with Democratic House and Senate leadership — or at least his meeting with House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer did not go well — but how do we expect Congress to navigate their relationship with Trump?

For instance, do we think Sen. Lamar Alexander’s retirement will give us another Bob Corker or Jeff Flake in the Senate (AKA a Republican senator not afraid of speaking out against Trump)?

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): If Corker and Flake means anti-Trump rhetoric but pro-Trump voting, I don’t expect Alexander to follow that pattern. I don’t think he will bash Trump in speeches.

sarahf: But he represents the loss of another old school Republican willing to reach across the aisle?

perry: Corker and Flake very, very rarely voted with Democrats. It was more a question of their rhetoric.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Just at a very high level here, I guess I’ll be That Guy who says the GOP is more likely to break with Trump than the conventional wisdom holds.

Granted, that’s sort of a weasel-worded statement, because “what the conventional wisdom holds” could mean a lot of different things.

But Republicans had a bad midterm and Trump has a lot of fires to put out. The GOP (either collectively or individually) might decide it’s in their strategic best interest to create some distance from Trump.

perry: I think I agree with that. But it could take many forms beyond Flake-Corker style tactics. Maybe Sens. Mitt Romney or Cory Gardner distance themselves from Trump.

Or maybe we see more examples of where the Senate rebukes Trump, like they did last week in a vote calling for the end of U.S. military assistance to Yemen and blaming Saudi crown prince Mohammed bin Salman for the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi. (The Trump administration has been circumspect about its views on whether Mohammed played role in the killing, perhaps because of the strong relationship between the Saudi leader and Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner).

ameliatd (Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, FiveThirtyEight contributor): Break with Trump on what, though? We just saw Senate Republicans downplay the news that Trump directed Michael Cohen to make illegal campaign contributions last week.

I guess I wonder what “distancing” means, given that House Democrats’ investigations into something like Trump’s finances could mean that potentially damaging information will made public. Do you mean “distancing” on those issues? Or policy? Or something else?

perry: Breaking with Trump is very issue dependent. On foreign policy, you have already seen that happen. On Robert Mueller and the special counsel’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, I’m not as sure.

natesilver: That’s fair enough. And it’s not like we should expect Republicans to break with Trump on issues of economic policy, to the extent that his agenda is fairly well-aligned with theirs.

ameliatd: It seems like with foreign policy — like last week’s Yemen vote — that Senate Republicans are following up on their previous criticism of Trump for his rhetoric and actions (or inaction), in this case their outrage over the murder of Khashoggi. The vote is significant, but it’s not out of line with their past positions.

sarahf: I was surprised that the Senate voted to stop sending military aid to Yemen. But I do think we have some evidence that the Senate is willing to oppose Trump when it comes to his stances on Russia. For example, they’ve pushed back when Trump has stalled sanctions on Russia. Although, the administration has also at times passed tougher sanctions without congressional prodding.

natesilver: I do wonder what would happen if Trump really did try to push an infrastructure bill through the Democratic-controlled House — or a tax bill that would remove the SALT limitation. Those things could be popular for Trump and things the Democratic House would go along with, but still opposed by the Republican Senate.

perry: I think I disagree with Nate. I expect 90 percent of Republicans to basically go along with anything Trump does on virtually any issue, whether that’s Mueller, Russia, etc.

I think the number of GOP critics will go up, but it will still be tiny — like maybe five senators and 12 House members or something.

natesilver: We’re mostly talking about what happens if things in the Mueller investigation nexus escalates? How do Republicans react, say, if Trump pardons a family member? Or tries to fire Mueller?

perry: Exactly.

So I’m saying if he pardons Paul Manafort, his one-time campaign chairman, you have will 10 Republicans in the Senate who complain and 43 who make up excuses and basically defend it.

Do you see that math differently?

ameliatd: Pardons are tricky because the only way to rebuke Trump is basically the nuclear option — impeachment.

natesilver: Is a Manafort pardon a nuclear event?

ameliatd: I think a pardon of a family member could be a nuclear event. (Although even that has happened before! See Roger Clinton.) Manafort … depends more on how and when it happens.

perry: I think a Manafort pardon would be covered by the press as a big event, with the “Never-Trump” Republicans slamming him and suggesting that Trump is violating the rule of law. ameliatd: There have been other high-profile, unpopular pardons related to special counsel investigations — like the pardons that ended Iran-Contra — and I’d see a Manafort pardon falling in that category. Would Trump be criticized? Yes, of course. But it’s not unprecedented and I’m not convinced it would rise to the level of impeachment.

natesilver: Perry, I guess my thinking is that the generic backbench Republican senators, say, John Thune — who’s not quite a backbencher but pretty average in other respects — weren’t necessarily on the Trump Train to begin with.

So what if they have another train to board? Maybe the Pence train?

perry: That what I was trying to draw out. I don’t see someone like John Thune breaking with Trump pre-election.

And you do. That’s interesting.

I might be wrong.

natesilver: I don’t think this would necessarily happen until mid-to-late 2020, but as a matter of theory, couldn’t there be the cut-your-losses-and-save-the-Senate-because-Trump’s-gonna-lose train?

sarahf: Right, I think you could envision a larger defection among the GOP if the conventional wisdom became aligning with Trump will cost you re-election.

Granted, that hasn’t really panned out so far.

perry: I see folks in swing states like Susan Collins, Gardner and Martha McSally, taking shots at Trump. But a lot of the Trump-skeptical Republicans in the House lost in November. natesilver: But in 2016 Trump defined the (not-actually-that-long) odds and won, so there was a a bit of a perception that he walked on water. But 2018 ought to have disabused anyone of that notion.

The other thing is … the number of Republican retirements was very high in 2018, and there’s already reporting about how there might be a lot of retirements before 2020.

On the one hand, that makes Trump’s life easier, because it means (although it costs the GOP seats in Congress) that some of his critics are out of power. On the other hand, maybe that means there’s a lot of internal dissension within the GOP ranks that lurks not-so-far beneath the surface.

perry: I think the actual state of politics and where politicians think the state of politics is are different things. It might be a good idea for congressional Republicans to align less with Trump. back away from Trump. Will they? I doubt it.

ameliatd: So what would create the impetus for a larger defection? A bombshell from Mueller? Something else?

perry: I think it all boils down to re-election.

So if Trump’s numbers dip really, really low, like Bush’s 2008 levels, that changes everything. I’m not sure what Mueller finds matters, barring some really, really clear Trump-emailing Putin-style collusion.

natesilver: A Mueller report that proved (or credibly alleged) actual collusion with Russia. Pardoning a family member. Firing Mueller.

perry: Those three I think would generate huge pushback. Which is why I don’t think he’ll do the other two. The first is, of course, not up to Trump.

ameliatd: I agree with you, Perry, that Mueller’s findings may not resonate, unless there is a very clear and damaging takeaway and the report is made public.

natesilver: And then there’s a fourth, longer-term risk: a recession, which could send Trump’s approval rating tumbling into the low-mid 30s. In which case, Republicans might decide that a lot of the non-collusion investigations stuff looked like a compelling reason to distance themselves from Trump, too.

sarahf: Yeah, I think a potential recession would create more distancing from Trump. We’ve already seen some pushback regarding his stances on trade and tariff agreements within the party.

perry: I think one other potential move against Trump is a real primary challenger, with real support.

Do we see that happening?

sarahf: Ha, that’s what I was going to ask. I mean I always forget about it, but Jimmy Carter was primaried by Ted Kennedy in his re-election bid. So it has happened!

natesilver: I guess I see a primary challenge as being more an effect than a cause.

ameliatd: Isn’t that somewhat dependent on the other things happening, i.e. damaging information about Trump comes out or he does something wildly unpopular like firing Mueller, making a viable primary challenge possible?

natesilver: Like, there’s going to be some type of primary challenge to Trump, because someone’s going to want to get media attention and sell books.

But I don’t think a Kasich primary challenge would greatly affect anything.

(To take one of the more obvious names.)

ameliatd: Nobody tell Kasich that.

perry: Do you think a candidate will actually declare and run against Trump?

Larry Hogan went to this anti-Trump GOP conference I attended last week. He would be an interesting challenger, for sure.

natesilver: A scenario where Trump’s approval rating is 32 percent or something though — in which case, his approval rating among Republicans might be “only” 75 percent or something — might present the risk of a more formidable, Kennedy vs. Carter type of challenge.

perry: I agree with Nate that a real primary challenge is more an effect than a cause, but I also think such a challenge might still have an actual effect.

sarahf: That certainly would be something! But it does seem as if heading into 2019, both Democrats and Republicans have to ask themselves what will they have to show voters by 2020, especially if they can’t expect to pass a lot of legislation.

ameliatd: Well, that’s where the Democrats’ House investigations could be important.

sarahf: Do you think Democrats run the risk of having those investigations backfire?

ameliatd: I think they run the risk of taking on too much, producing too much, and sort of drowning in their own findings.

perry: I think Democrats will pass some bills in the House in the next two years, demonstrating they have an agenda. But all such bills will be blocked. They will also investigate Trump, but won’t move to impeach him without really clear evidence of collusion.

natesilver: To argue against myself a bit here, obviously one thing Republicans will be saying is that they’re key to preventing Democratic overreach — and that all Democrats do is endlessly investigate the president instead of focusing on policy. So that would align them more closely with Trump.

sarahf: I can totally see that happening.

natesilver: But maybe Democrats will be more disciplined than Republicans assume — they’ll be pretty careful about what they investigate, and how. That Pelosi seems to have tamped down any calls for impeachment is a sign that she knows what she’s doing, and different from what my expectations would have been a year ago if you’d told me that Democrats would win 40 House seats.

ameliatd: The Democrats’ investigations are from … the Democrats. So they have a higher bar to clear, in terms of establishing that they’re not just investigating Trump for the sake of investigating Trump. But Mueller’s investigation has credibility because it’s not political. (At least, insofar as anything today has credibility.)

perry: I tend to assume Mueller will find more and that what he finds will have more credibility, and that Democrats know that.

ameliatd: But the Democrats also know that Mueller doesn’t have the same goals they do.

There is a lot the Democrats might want to make public that simply isn’t relevant to Mueller’s task of finding criminal wrongdoing and then prosecuting it.

perry: I don’t know that the public will be able to assess whether “they’re investigating too much” unless it rises to the level of impeachment, which I think is a red line.

ameliatd: But impeachment itself is kind of a fuzzy line. Was directing Michael Cohen to make illegal campaign payments an impeachable offense? Maybe. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to lead to serious talk of impeachment.

perry: The most interesting question I have for Democrats is whether they’ll work on bipartisan policies with Trump. For instance, there is a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill in the Senate right now. It contains policy goal Democrats agree with, but it also gives Trump a win and portrays him as caring about black people, even though the GOP largely ignores black voters. Arguably, the Mitch McConnell approach (don’t work with the other party’s president on much of anything) does have some virtues, politically.

natesilver: In a weird way, it does give Democrats some leverage. They need to have policy gains that are really worth something, because the political benefit of cooperating with Trump is not obvious.

ameliatd: It’s really stunning to me that the criminal justice reform bill is moving forward now, of all times. But I don’t think the Democrats would agree to that particular legislation if they had more leverage — it’s just not far-reaching enough.

perry: So you all think that Democrats will add liberal measures to any compromise bill, knowing full well that Republicans won’t agree, therefore, effectively killing the bill?

ameliatd: I mean, what do they have to lose by doing that? It seems like they have a lot to lose by not doing that.

perry: Democrats tend to be the party of government and getting things done. I will be curious if they can stomach McConnell-style opposition.

sarahf: If Democrats adopt that approach, one risk is it feeds the narrative that all Democrats do is investigate the president and not focus on policy solutions.

And arguably, they really can’t afford to do that — at least as far as health care is concerned.

Many of them ran on a health care platform!

ameliatd: I am very interested to see what they’ll do on health care.

Particularly after that Texas judge issued a ruling striking down the entire ACA last week.

A lot of legal experts think that ruling won’t hold up on appeal, but it brings health care back into the conversation in a very dramatic way.

perry: Do Democrats: 1. Pass a Medicare-for-all bill through the House 2. Pass some kind of Medicare-for-some bill 3. Or basically do nothing but defend Obamacare?

A very liberal health care bill could give Trump something to run against in 2020.

natesilver: Perry, I’m not sure that option 2 makes sense. Either you pass option 1, to lay down a marker, or you say, “We don’t control the Senate, so let’s not bother right now.”

The thing is …. I think Medicare-for-all is going to become sort of a litmus test for Democrats in the primary anyway. So they’re going to have to “own” that policy, in some way or another.

The question is whether individual Democratic members from swing districts will want to own it when there isn’t a chance of actually passing it. If there isn’t, Pelosi will probably not bring it to the floor.

perry: Well, do they bring to floor if it can pass the House?

It will have no chance in Senate, but I think the progressive wing of the party wants a vote in the House on single payer over the next two years.

sarahf: I think you’re right, Perry. And if they have the votes, they’d pass it even though it dies in the Senate. I’m just not sure that enough Democrats from swing districts will go for it. Currently, the idea only seems to be supported by the progressive wing of the party and not the more centrist faction, which also grew considerably in 2018.

But, by the same logic, if these representatives from swing districts have nothing to show their constituencies regarding health care after two years, what do they really have to lose by backing a more progressive plan in the first place?