Nate Silver's Blog, page 76

December 3, 2018

Politics Podcast: Something Seems Fishy In North Carolina

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The numbers of mail-in absentee ballots in North Carolina’s 9th Congressional District look strange, and some voters have submitted affidavits claiming that someone picked up ballots from their homes. Professor J. Michael Bitzer of Catawba College joins the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast to discuss the possibility of election fraud in the district.

The crew also reflects on how American politics have changed since the late President George H.W. Bush’s time in office and discusses two incidents of Senate Republicans breaking with President Trump in the past week.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

November 29, 2018

Emergency Politics Podcast: Cohen Is Now Cooperating With Mueller

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In their second Mueller-related podcast of the day(!), the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team reacts to news that President Trump’s former lawyer, Michael Cohen, pleaded guilty Thursday to lying to Congress about the details of a Trump Organization real estate deal in Russia. The plea formalized Cohen’s cooperation with special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into interference in the 2016 election and positioned Cohen as a potential star witness in the Russia investigation.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

November 28, 2018

How Much Does Climate Science Matter In A World Run By Politics?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): So the Friday after Thanksgiving, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with a dozen other federal agencies, published a hefty report on climate change that contained some pretty bad news: The U.S. and world face dire environmental consequences if immediate action is not taken.

But … that isn’t exactly a new finding. What seemed to be particularly noteworthy (other than the timing of the release, which came when many Americans, including reporters, are taking time off from work) was that it involved a number of federal agencies essentially contradicting every stance President Trump and his administration have taken on climate change.

You were on Friday’s press call, Maggie. What do you make of it?

maggiekb (Maggie Koerth-Baker, senior science writer): Yeah, it was interesting. I’d say there was a good 45 minutes of that press call that was different reporters trying different ways of asking the same questions: Why is this thing being released the day after Thanksgiving, when that wasn’t the original plan? What do you think of the president’s rejection of climate science? What does it mean when your report and the White House contradict each other?

And each time the people from NOAA and the National Climate Assessment would just kind of stonewall them. Back and forth — a question about the politics, a response about how the real news is the results of the research.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): And I’m guessing the leading questions from reporters in the vein of, “Why was this released the day after Thanksgiving?” have to do with the administration trying to tamp down coverage of the findings, right?

maggiekb: Yup. And the answer wasn’t very satisfying. They kept saying it was because they wanted the report to be out before a couple of big, upcoming scientific meetings where people will want to talk about the findings. But they never responded to the point that, you know, you could have accomplished the same thing by releasing it this week.

I think it’s obvious to most people, at this point, that the politics are important. At least as important as the scientific findings. Because we already know the science — “we” being the public, I mean. There’s not a lot in the assessment that is really going to surprise anybody who knows the basics of climate change. What matters most at this point is what we do with the findings. And if the political reality is that we’re ignoring it …

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): OK, let me ask a dumb question of the rest of you. Why would the White House let the report be released at all? Could they have just squashed it if they wanted?

clare.malone: I believe it is legally required for them to produce a report.

natesilver: See, that’s why I said it was a dumb question.

clare.malone: Lol, no!

maggiekb: Yeah, these assessments started because of an act of Congress. But it’s not a dumb question at all. I had to stop and think for a minute and remember that.

sarahf: I think it was smart of the Trump administration to not be visibly involved and to avoid the debacle the George W. Bush administration faced after a memo surfaced showing how they wanted to sow confusion about whether scientists agreed on the existence of global warming by changing the language they used to describe climate change.

clare.malone: Yeah, the Bush administration got in trouble with the way they tried to finesse scientific findings! In the lead-up to Trump’s inauguration, we wrote about the ways that previous administrations have fudged public releases of scientific data.

maggiekb: I think I’m mostly surprised the Trump administration hasn’t replicated what Canada did. Back in the early 2010s, the conservative government basically just blocked all federally funded climate scientists from talking directly to the press. There were several years where papers would come out but you couldn’t get interviews with any Canadian authors.

clare.malone: But political finessing works! I was honestly shocked by the findings here.

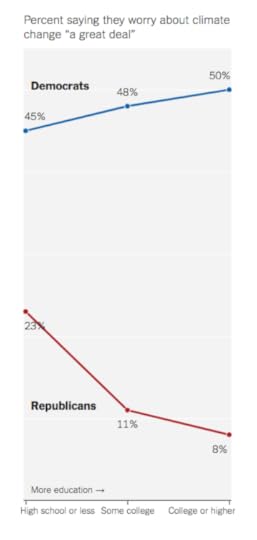

The New York Times

The idea that people with more education who are Republican are less inclined to be worried about climate change just seems so counterintuitive.

sarahf: I, too, was really surprised by that piece, Clare. The split between parties tracks with what we know about how divided Americans are by political party about climate change, with Republicans largely opposed. But do we think that some of education-based split within the GOP could be because Republicans with less education are more likely to live in rural parts of the country that are more directly impacted by climate change?

clare.malone: I don’t think the regionalism thing sounds exactly right, but what do I know!

I did buy the idea that college-educated Republicans might be more attuned to the ways that the issue was politicized, i.e., greater exposure to partisan news sources.

natesilver: OK, another dumb question: What degree of independence does NOAA have? Could Trump try to install a bunch of climate “skeptics” within leadership positions at the agency?

sarahf: Ha, remember how well Myron Ebell worked out as the head of the Environmental Protection Agency as part of Trump’s transition team, Nate?

maggiekb: Also not dumb, Nate. I honestly don’t know the answer to that. It seems like he certainly could nominate a skeptic if he wanted. The guy who is nominated for that role, Barry Myers, isn’t a climate skeptic to my knowledge, but he comes with a whole host of conflicts of interest. He owns AccuWeather and has spent years advocating for agencies to stop making publicly funded weather data available to the public except through companies like AccuWeather, who can repackage and sell it.

clare.malone: Whoa.

That’s a thing??

Big Weather?

maggiekb: Oh, yes.

But then, on the other hand, getting Myers confirmed doesn’t seem to have been a big priority for the administration, or he seems to have been met with significant resistance from Congress. This Washington Post story is from April, but he’s still in limbo.

clare.malone: Wow. Well now I’m woke to Big Weather.

maggiekb: You missed my spreadsheet of how many members of the Myers family are employed by AccuWeather or other companies that might represent a conflict of interest, Clare.

It gave me headaches.

clare.malone: Yeoman’s work, Maggie.

Here’s a question that’s very much related to this report: How much does the U.S. pulling out of the Paris Climate Agreement screw up world progress on this? A lot, right?

We’re sort of the big ole missing piece if you’re talking about the economic cooperation needed to forestall further damage, right?

maggiekb: I mean, climate change is an international issue. And our country is one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the world. The fact that we haven’t been part of the international, cooperative work on this in decades is, yeah, a big deal.

That’s before Paris, too, of course. This goes back to when we never ratified the Kyoto Protocol. But I think there’s a very good case to be made that American partisan politics — and the way that partisanship has settled around environmental issues — is a huge part of why we aren’t tackling climate change in a big way, globally.

sarahf: So does this report move the conversation forward for the U.S. because it was published by federal agencies, instead of, say, a group of scientists affiliated with the United Nations who published a report in October that also predicts catastrophic global consequences?

Or does it not really move the needle at all? And if it doesn’t, what does that mean for the U.S. if we don’t take action?

clare.malone: I honestly think I have an uncertain handle on how urgently the American public thinks about climate change.

I will say that the particular hellishness of the California wildfire stories seems potentially motivating for people.

I’m curious as to whether 2020 Democratic candidates will put climate change front and center.

maggiekb: Environmental stuff isn’t on the top of a lot of voters’ political priority lists, that’s for sure. It’s a thing we fret about, but not a major thing we vote on. Or tell people we’re going to vote on, anyway.

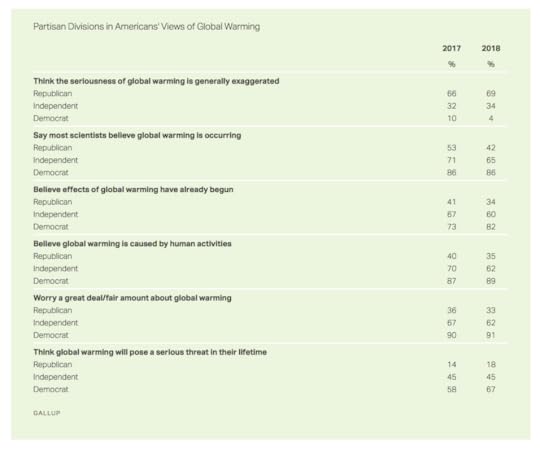

natesilver: The public is reasonably convinced that climate change is real and manmade.

Gallup

And in general, the public has become more convinced of this in recent years.

Trump may even have made people more concerned about global warming because public opinion often moves in the opposite direction of what the president believes, especially if the president is unpopular.

maggiekb: Oh, that’s an interesting thought that some people might disdain Trump strongly enough to get over doubts about climate change. But are there a lot of people who both dislike the president and weren’t already on board with climate science? I guess maybe some of the Republican #NeverTrumpers?

sarahf: Rep. Carlos Curbelo lost his re-election bid, but there is the House Climate Solutions Caucus, which he helped found. It has a number of Republican members and, according to that POLITICO article, the caucus apparently tripled in size after President Trump announced his decision to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris climate accord.

natesilver: I mean, there’s certainly a position, which was once pretty fashionable within the GOP, that climate change is real and manmade but that we need market-based solutions, more research and development for carbon-capture technologies, etc.

That was Romney’s position, right? Not that long ago.

maggiekb: God. I guess you’re right. It feels like a long time?

clare.malone: Maybe Sen. Romney will take it up again …

natesilver: Of course, Republicans may not have actually been interested in any substantive actions, including market-ish stuff like tradable permits. But there was at least lip service to the notion that climate change was real and the science was basically right.

sarahf: That’s right. Taxes on carbon have long been an incentive to get conservatives on board! But it increasingly feels like without immediate action, we’ve missed the point of no return if we take these reports at face value. So I guess my question is: What comes of this?

natesilver: What happens? The Democratic candidate for president makes a bigger deal of climate change than Clinton did in 2016. If he or she is lucky enough to win, they pass something through the House. But then it gets stymied in the Senate because the Senate has a built-in bias toward rural, agricultural states.

The nature of the Senate — not Trump — is the biggest barrier to U.S. action on climate change in the long run, in my opinion.

maggiekb: And what they propose is probably not as sweeping as it needs to be to really deal with the problem to begin with, if I can get climate hawkish here. And it’s probably for the same reasons that Nate just explained. We have a lot of forces in the U.S. that push our climate policy toward “not radical” solutions even as the problem becomes increasingly radical.

sarahf: I hate to echo what Clare said earlier, but it probably will take widespread hellishness like the California wildfires to spark the U.S. to take radical action, and even that might be naive.

natesilver: I mean, in some ways the climate change “debate” was a template for Trumpism. It involved a backlash against elites and empiricism, but the ultimate beneficiaries of the “populist” stance are not necessarily working-class voters so much as big, rich businesses.

Which is not to say that there aren’t some voters in some regions who would be hurt by efforts to mitigate climate change. There certainly would be, especially in the short run.

But it’s sort of a faux-populism where, conveniently enough, the populist stance also serves the interest of big, established businesses.

maggiekb: Unfortunately, I think you’re correct about the parallels here, which makes finding a solution to mitigate climate change hard. Also, fun cameos from misinformation campaigns!

Can’t forget those.

November 26, 2018

Politics Podcast: Is Trump’s Border Crisis Manufactured?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents fired tear gas at Central American migrants who ran toward the U.S.-Mexico border on Sunday. The agency also temporarily closed the border crossing near San Diego. The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew puts the current situation at the border in context and asks how much it is affecting American politics. They also preview the final U.S. Senate election of 2018, which is taking place in Mississippi on Tuesday. The race between Republican Cindy Hyde-Smith and Democrat Mike Espy is highlighting fault lines on race and geography in the South.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

November 20, 2018

Trump’s Base Isn’t Enough

There shouldn’t be much question about whether 2018 was a wave election. Of course it was a wave. You could endlessly debate the wave’s magnitude, depending on how much you focus on the number of votes versus the number of seats, the House versus the Senate versus governorships, and so forth. Personally, I’d rank the 2018 wave a tick behind both 1994, which represented a historic shift after years of Democratic dominance of the House, and 2010, which reflected an especially ferocious shift against then-President Barack Obama after he’d been elected in a landslide two years earlier. But I’d put 2018 a bit ahead of most other modern wave elections, such as 2006 and 1982. Your mileage may vary.

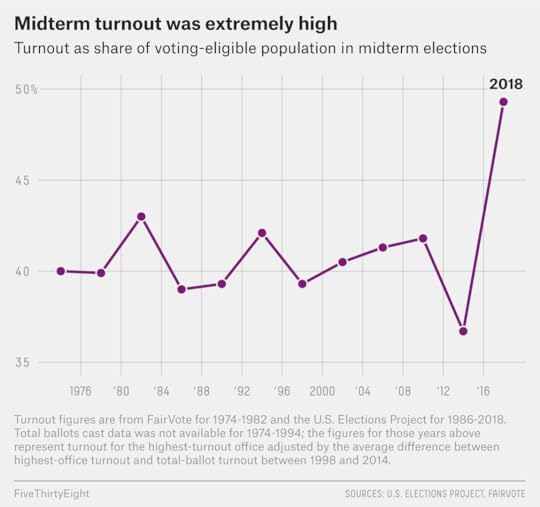

In another important respect, however, the 2018 wave was indisputably unlike any other in recent midterm history: It came with exceptionally high turnout. Turnout is currently estimated at 116 million voters, or 49.4 percent of the voting-eligible population. That’s an astounding number; only 83 million people voted in 2014, by contrast.

This high turnout makes for some rather unusual accomplishments. For instance, Democratic candidates for the House will receive almost as many votes this year as the 63 million that President Trump received in 2016, when he won the Electoral College (but lost the popular vote). As of Tuesday midday, Democratic House candidates had received 58.9 million votes, according to the latest tally by David Wasserman of the Cook Political Report. However, 1.6 million ballots remain to be counted in California, and those are likely to be extremely Democratic. Other states also have more ballots to count, and they’re often provisional ballots that tend to lean Democratic. In 2016, Democratic candidates for the House added about 4 million votes from this point in the vote count to their final numbers. So this year, an eventual total of anywhere between 60 million and 63 million Democratic votes wouldn’t be too surprising.

There isn’t really any precedent for the opposition party at the midterm coming so close to the president’s vote total. The closest thing to an exception is 1970, when Democratic candidates for the House got 92 percent of Richard Nixon’s vote total from 1968, when he was elected president with only 43 percent of the vote. Even in wave elections, the opposition party usually comes nowhere near to replicating the president’s vote from two years earlier. In 2010, for instance, Republican candidates received 44.8 million votes for the House — a then-record total for a midterm but far fewer than Barack Obama’s 69.5 million votes in 2008.

Democratic candidates for the House in 2018 received almost as many votes as President Trump in 2016

Opposition party’s total popular vote in midterm House elections as a share of the president’s popular vote in the previous election, 1938-2018

Popular vote

Election

house opp. party

For House Opp. party

for President in prev. election

Opp. party’s house vote as share of pres. vote

2018

D

60-63m

63.0m

95-100%

1970

D

29.1

31.8

92

1994

R

36.6

44.9

82

1950

R

19.7

24.2

81

1982

D

35.3

43.9

80

1958

D

25.6

35.6

72

1946

R

18.4

25.6

72

1962

R

24.2

34.2

71

2006

D

42.3

62.0

68

1998

R

32.2

47.4

68

2002

D

33.8

50.5

67

1990

D

32.5

48.9

66

1954

D

22.4

34.1

66

2010

R

44.8

69.5

64

1974

D

30.0

47.2

64

1938

R

17.3

27.7

62

2014

R

40.0

65.9

61

1978

R

24.5

40.8

60

1986

D

32.4

54.5

59

1966

R

25.5

43.1

59

1942

R

14.3

27.3

52

“The resistance” turned out voters in astonishing numbers, performing well in both traditional swing states in the Midwest — including the states (Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania) that essentially lost Hillary Clinton the presidential election in 2016 — and new-fangled swing states such as Arizona and Texas. Turnout among young voters was high by the standards of a midterm, and voters aged 18 to 29 chose Democratic candidates for the House by 35 points, a record margin for the youth vote in the exit-poll era. The Hispanic share of the electorate increased to 11 percent from 8 percent in the previous midterm, according to exit polls. To some extent, these are stories the media missed when it was chasing down all those dispatches from Trump Country. In a descriptive sense, this was a really big story.

In a predictive sense, what it means is less clear. Sometimes — as was the case in 2006, 1974 and 1930 — midterm waves are followed by turnover in the presidency two years later. But most presidents win re-election, including those who endured rough midterms (such as Obama in 2010, Bill Clinton in 1994 and Ronald Reagan in 1982). Nor is there any obvious relationship between how high turnout was at the midterm and how the incumbent president performed two years later. Democrats’ high turnout in 1970 presaged a landslide loss in 1972, when they nominated George McGovern.

This year’s results do serve as a warning to Trump in one important sense, however: His base alone will not be enough to win a second term. Throughout the stretch run of the 2018 midterm campaign, Trump and Republicans highlighted highly charged partisan issues, from the Central American migrant caravan to Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court. And Republican voters did indeed turn out in very high numbers: GOP candidates for the House received more than 50 million votes, more than the roughly 45 million they got in 2010.

But it wasn’t enough, or even close to enough. Problem No. 1 is that Republicans lost among swing voters: Independent voters went for Democrats by a 12-point margin, and voters who voted for a third-party candidate in 2016 went to Democrats by 13 points.

Trump and Republicans also have Problem No. 2, however: Their base is smaller than the Democratic one. This isn’t quite as much of a disadvantage as it might seem; the Democratic base is less cohesive and therefore harder to govern. Democratic voters are sometimes less likely to turn out, although that wasn’t a problem this year. And because Republican voters are concentrated in rural, agrarian states, the GOP has a big advantage in the Senate.1

Nonetheless, it does mean that Republicans can’t win the presidency by turning out their base alone, a strategy that sometimes is available to Democrats. (Obama won re-election in 2012 despite losing independents by 5 points because his base was larger.) In the exit polling era, Republicans have never once had an advantage in party identification among voters in presidential years. George W. Bush’s Republicans were able to fight Democrats to a draw in 2004, when party identification was even, but that was the exception rather than the rule.

There are usually more Democrats than Republicans

Share of respondents to presidential election exit polls who identify as a member of each party

Year

Democrats

Republicans

Independents

Advantage

2016

37%

33%

31%

D 4

–

2012

38

32

29

D 6

–

2008

39

32

29

D 7

–

2004

37

37

26

EVEN

2000

39

35

26

D 4

–

1996

40

35

22

D 5

–

1992

38

35

27

D 3

–

1988

37

35

26

D 2

–

1984

38

35

26

D 3

–

1980

43

28

23

D 15

–

1976

37

22

41

D 15

–

Source: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research

I don’t want to go too far out on a limb in terms of any sort of prediction for 2020. In fact, lest you think that the midterms were the first step toward an inevitable one-term Trump presidency, several facts bear repeating: Most incumbent presidents win re-election, and although Democrats had a strong midterm this year, midterm election results aren’t strongly correlated with what happens in the presidential election two years later. Moreover, presidential approval numbers can shift significantly over two years, so while Trump would probably lose an election today on the basis of his approval ratings, his ratings today aren’t strongly predictive of what they’ll be in November 2020.

But presidents such as Reagan, Clinton and Obama, who recovered to win re-election after difficult midterms, didn’t do it without making some adjustments. Both Reagan and Clinton took a more explicitly bipartisan approach after their midterm losses. Obama at least acknowledged the scope of his defeat, owning up to his “shellacking” after 2010, although an initially bipartisan tone in 2011 had given way to a more combative approach by 2012. All three presidents also benefited from recovering economies — and although the economy is very strong now, there is arguably more downside than upside for Trump (voters have high expectations, but growth is more likely than not to slow a bit).

Trump’s political instincts, as strong as they are in certain ways, may also be miscalibrated. Trump would hate to acknowledge it, but he got most of the breaks in the 2016 election. He ran against a highly unpopular opponent in Clinton and benefited from the Comey letter in the campaign’s final days. He won the Electoral College despite losing the popular vote — an advantage that may or may not carry over to 2020, depending on whether voters in the Midwest are willing to give him the benefit of the doubt again. Meanwhile, this year’s midterms — as well as the various congressional special elections that were contested this year and last year — were fought largely on red turf, especially in the Senate, where Trump may well have helped Republican candidates in states such as Indiana and North Dakota. The Republican play-to-the-base strategy was a disaster in the elections in Virginia in 2017 and in most swing states and suburban congressional districts this year, however.

At the least, odds are that Trump needs a course-correction, and it’s anyone’s guess as to whether he’ll be willing to take one. While there’s some speculation that Trump could move in a more bipartisan direction, that hasn’t really been apparent yet in his actions since the midterms, or at least not on a consistent basis. Instead, he’s spent the first fortnight after the midterms firing his attorney general, implying that Democrats were trying to steal elections in Florida, and bragging about how he’d give himself an A-plus rating as president. The next two years will less be a test of Trump’s willpower than one of his dexterity and even his humility — not qualities he’s been known to have in great measure.

November 19, 2018

Politics Podcast: Will Pelosi Be Replaced?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast crew discusses whether Rep. Nancy Pelosi will be re-elected as Speaker of the House, now that Democrats have won back the majority, and what the opposition to her says about the party. They also look at new election results out of Florida, Georgia and Arizona and reflect on the significance of the “year of the woman.”

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

November 15, 2018

Politics Podcast: How Our Forecasts Did In 2018

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

With the election more than a week in the rearview mirror, Nate sits down for a post-mortem installment of “Model Talk” on the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast. He looks back at where things went right and where things could be improved, along with the state of polling during the 2018 election. He also answers questions from listeners, including whether he will have to rebuild the model from scratch in 2020.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

November 14, 2018

Yes, It Was A Blue Wave. No, It Doesn’t Matter For 2020.

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): So we’re here today to talk about the midterm elections and the BLUE WAVE … or blue trickle? Which is it, team!?!

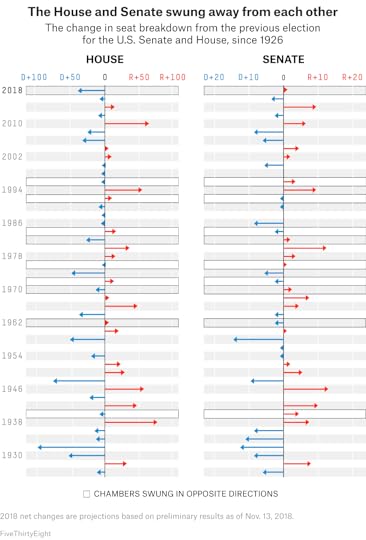

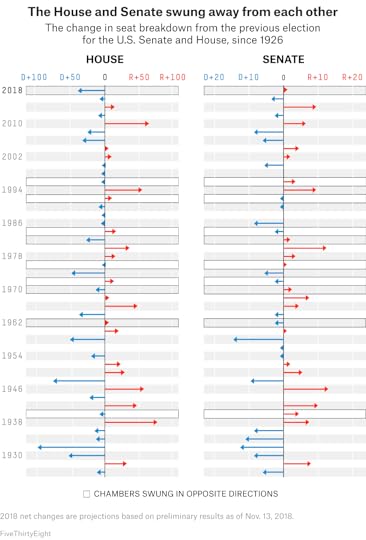

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): It was, by any historical standard, a blue wave. Democrats look like they’re going to pick up around 38 House seats, which would be the third-biggest gain by any party in 40 years (after Republicans in 2010 and 1994). The Senate moved in the opposite direction, but not by much, and it was a very difficult map for Democrats anyway.

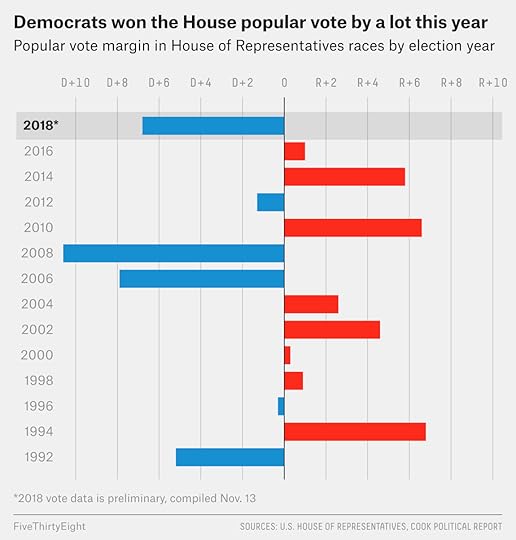

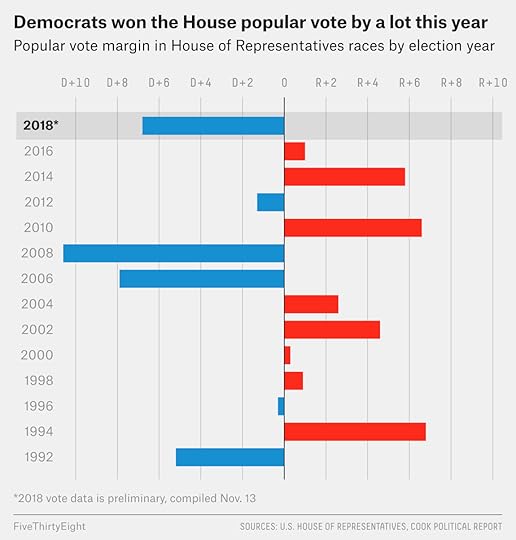

And Democrats won the House popular vote by 6.8 percentage points, according to preliminary data from the Cook Political Report. And Cook’s Dave Wasserman thinks continued vote-counting in California should bring Democrats to well over 7 points. That would be the third-highest popular vote margin of any election since 1992 (behind Democrats in 2006 and 2008).

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): The arguments that it ISN’T a blue wave are dumb. Can we end the chat now and get lunch?

sarahf: Haha, no. We’re here to tell readers why it’s dumb — although Nathaniel did do a pretty good job of convincing me.

nrakich: People seem to be defining “blue wave” as, “Did Democrats outperform expectations?”

They’re forgetting that expectations were already for a blue wave.

natesilver: What is the argument that it isn’t a blue wave? That Democrats didn’t win the Senate?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Fun chat.

nrakich: Democrats largely matched expectations in the House but fell a little bit short of them in the Senate and governor races.

clare.malone: Let’s step out of the numerical zone for a second, then, and engage with why some people are NOT interpreting it as a “blue wave.”

I think it says something about the political environment that Democratic voters wanted that overarching rebuke to President Trump.

I’m guessing a lot of people thought Democrats could win the Senate because they weren’t paying attention to politics that closely. Or more precisely, the electoral apportionment part of politics. I don’t blame regular people for that. Now, I think we can criticize media outlets …

natesilver: I think they’re arguing it’s not a wave because (1) the “split decision” narrative is very attractive if you’re of a both-sides mentality, (2) it takes a little bit of work to figure out why Democrats didn’t win the Senate (i.e., you have to look at the fact that the contests were all held in really red states), (3) Democratic gains are larger than they looked like they’d be at say 10:30 p.m. on election night, when these narratives were established.

nrakich: I understand why Democrats are disappointed, Clare. They lost the Senate! You’d rather win than lose! But we should educate them that a loss of two, maybe one, seats in the Senate was actually a remarkable feat for Democrats in this Senate map.

natesilver: Ehhhhhhhhhhhhhh

I think that’s going a little too far.

nrakich: Democrats were so overexposed that, in a different environment, Republicans could have taken 60 seats in the Senate and made it really hard for Democrats to take back the Senate in the next decade or more.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein has a good case complicating the idea of a blue wave:

On Tuesday, a divided America returned a divided verdict on the tumultuous first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. Rather than delivering a “blue wave” or a “red wall,” the election produced a much more divergent result than usual in a midterm.

Democrats made sweeping gains in the House, ousting Republicans in urban and suburban seats across every region of the country to convincingly retake the majority for the first time since 2010. …

But Republicans expanded their Senate majority across a belt of older, whiter heartland states.

It’s worth considering the idea that, yes, Democrats made gains. But the shift of white, working-class voters to the GOP that has been happening for a long time became clearer in 2016 and remained unchanged in 2018. A certain kind of voter — largely suburban — broke with Trump and the GOP, but Republicans look really strong in rural and white, working-class America.

natesilver: On the narrower point about the Senate — yeah, Democrats would have lost a bunch of seats in a neutral environment. But there was no reason to expect a neutral environment. The default is that the “out” (non-presidential) party does pretty well, especially under unpopular presidents.

So I think people who were like “Democrats are gonna lose six Senate seats” didn’t have the right prior.

nrakich: Sure, Nate, but I’m comparing it to a world in which Hillary Clinton won the presidency.

Although, frankly, Democrats still could have lost more seats with a Republican as president.

If Jeb Bush had won the 2016 election and the economy was still humming along, the generic congressional ballot might have been D+3, instead of D+9, and Democrats would have lost four or five Senate seats instead of two.

sarahf: Right, but this was supposed to be a rebuke on a president that has defied American norms! I guess I kind of find Brownstein’s argument in the piece that Perry shared convincing — the midterm elections didn’t wind up solidly in either party’s win column; rather it showed just how divided America remains.

nrakich: It was a rebuke!

It’s just that we’ve known that it was going to be that since early 2017. So it was already priced in in everyone’s minds.

sarahf: So does it mean that Democrats just can’t win in Missouri, Indiana and North Dakota (states where Democratic incumbents lost Senate contests last week) because those states are just too red now? Even though Democrats had a sweeping victory in the House, this year’s Senate map underscored some big electoral challenges that they will face moving forward — i.e., Democrats better hope the Midwest continues to move to the left, because I think we saw that the Sun Belt is still a ways away from shifting.

nrakich: Don’t think of what happened in the Senate in terms of gains and losses for Democrats. Instead, think of the raw number of seats they won: at least 24 out of the 35 Senate seats on the ballot this year (we still don’t know who won yet in Florida or the Mississippi special election).

Considering that 18 of the 35 Senate seats up this year were in red states, it’s impressive that Democrats took a majority of them.

sarahf: What I’m hearing is that despite losses in the Senate, Democrats did well under the circumstances. But I wonder what you all make of the fact that Democrats didn’t pick up a single rural district?

natesilver: The average tipping-point Senate seat was in an R+16 state. The average tipping-point House seat was R+8.

So that tells you something: Democrats had no problem winning in R+8-type districts, which is pretty good, but the R+16 is a bridge too far in a world of high partisanship (at least for their incumbents in the Senate). Their incumbency advantage was just too small.

sarahf: But then how do we explain Montana and West Virginia? Those are both very red states, R+17.7 and R+30.5, respectively, and both of the Democratic incumbent senators there won on Tuesday. Is it just because of a strong incumbency advantage? Or is it that both states have small populations and more elastic voters?

It’s hard for me to believe that a winning electoral strategy for Democrats is to not court voters in more rural, red states and just ride out incumbency as long as possible.

But it seems as if that might be where Democrats are headed? That partisanship matters more than ever and Democrats trying to win Arizona and maybe Texas are the future? (Although, I have to say Texas leans pretty Republican at R+16.9).

natesilver: I mean, some incumbents are certainly stronger than others. There’s still variation around a mean. But the mean is one where partisanship is strong and incumbency is weak.

clare.malone: Montana has a bit of that Western streak, so it favors its guy (perhaps another key distinction), and the incumbency advantage works better there. West Virginia has a pretty conservative Democrat in Joe Manchin and a guy with good name recognition in the state.

perry: I think the wave happened and that Democrats had a great night. I do think, at the same time, that the election reinforced some of the weaknesses of the Democratic Party. For instance, Barack Obama won Indiana in 2008, but Sen. Joe Donnelly lost there last week. Obama won Ohio in 2008 and 2012. And, yes, Sen. Sherrod Brown did win his re-election bid, but Democratic gubernatorial candidate Richard Cordray lost. It makes me think Ohio is starting to look more like a GOP state now (considering how easily Trump won there in 2016).

I would also say that Trump is the 2020 favorite in Iowa and Florida, considering his victories in 2016 and the GOP performance in those states last week: Republican incumbent Gov. Kim Reynolds won in Iowa, and it looks as though the Republican candidate will win in Florida’s Senate and gubernatorial races.

nrakich: Right. It can be a blue wave while still flagging danger spots for Democrats in future elections.

But for now, Democrats — relax and enjoy.

sarahf: I don’t know. The 2020 Senate map looks tough, though not as bad as this year’s, I realize.

clare.malone: I think on an emotional level, to bring it back to why people are having mixed reactions, the “blue wave” confirmed that there are deep divisions in the country that people have been hearing all about.

perry: I don’t think Democrats can relax and enjoy this, because I think the 2018 midterm results suggest that Trump could very much still win in 2020. That was obvious pre-election to me, but I’d say it’s even more obvious now.

clare.malone: Right? To us, maybe.

But not to a lot of people.

Also, I think Democrats got bummed that the candidates with emotional resonance didn’t win — Beto O’Rourke in Texas, Stacey Abrams in Georgia, and Andrew Gillum in Florida (both Abrams and Gillum are obviously still tbd, but it doesn’t look good for Democrats).

nrakich: And the only, like, Democratic “revenge” win was defeating Gov. Scott Walker in Wisconsin.

clare.malone: Right.

natesilver: Some of the bigger Democratic wins didn’t get called until later in the night. The Wisconsin governor was a big one. And then there are the Senate pickups in Nevada (called late) and Arizona (which didn’t get called until Monday).

nrakich: Agreed, Nate — there’s anchoring bias going on here. People’s narratives got baked at 10 p.m. on election night, when Democrats weren’t doing as well as they are now, and they’ve been slow to update them.

natesilver: Democrats also had a good night in Michigan, although Sen. Debbie Stabenow’s margin was a little closer than expected. And a very good night in Wisconsin.

perry: Yeah, the 2020 map looks better for Democrats than I expected in a few places. Pennsylvania looks really strong for them, and Arizona is probably a real 2020 swing state.

sarahf: Here’s a thought. There was a blue wave — but it was fueled by Democratic moderates.

Is that accurate? Was there perhaps some disappointment among Democrats who didn’t see as big of a progressive change as they’d hoped?

clare.malone: It’s interesting, Sarah. Because we do find some evidence that the swing-y voters in this election were people that used to vote more Republican.

natesilver: But, like, there’s a downside to the Trump coalition. Say there are maybe 22 or 23 states that are really, REALLY Trumpy, but then the median district is not.

In the Senate, that could actually work out super well for Trump. But it’s a problem for the Electoral College and for the House.

perry: On Sarah’s point, I’m not sure how easy it is to define who is a “moderate” or a “liberal” in today’s Democratic Party. Tammy Baldwin (she supports “Medicare-for-all”) is quite liberal, and she won. Democrat Lucy McBath made her candidacy for the House in Georgia increasing gun control and still won. Sherrod Brown of Ohio is fairly liberal. But Arizona Sen.-elect Kyrsten Sinema is more of a centrist.

The whole moderate-liberal thing is very complicated. Are we really talking about (1) a candidate’s policy position (i.e., do you support liberal ideas like “Medicare-for-all”?), or 2) a candidate’s posture (i.e., are you anti-establishment and branded in the style of Bernie Sanders, or are you pro-establishment and more like Clinton or Obama?)

sarahf: That’s true, Perry. Still, it’ll be interesting to see what governance looks like with this new Democratic House.

perry: I think the first bill in this new House will be some kind of election proposal: Try to limit gerrymandering, strengthen the Voting Rights Act, etc.

nrakich: That’d be a smart move for Democrats, Perry. If Democrats want to hold onto power, they need to start by addressing the structural factors that currently hold them back.

natesilver: Yeah, the ballot proposals were another bright spot for Democrats, and a lot of them were electorally oriented — i.e., make it easier for more people to vote.

That’s something that could pay dividends down the road. And also something that Democrats are likely to replicate in the years ahead, I’d think.

nrakich: Automatic voter registration in Michigan and ending felon disenfranchisement in Florida are two big ones for Democrats, I’d say.

Although we should caveat this by saying that those ballot measures won’t turn Michigan and Florida into safely blue states overnight. But they could add several thousand votes, which would be enough to tilt a close election — like we’re currently seeing in Florida, coincidentally.

perry: Proposals on voting measures unite Democrats. And I actually think some of the talk about House Democrats being divided is over-hyped. Because in an environment where it’s unlikely that major bills will be passed, does it really matter if some Democrats are in favor of “Medicare-for-all” while others are in favor of expanding Medicaid? Neither of those things will pass. Nor will Immigration and Customs Enforcement be abolished while Trump is in office.

sarahf: Perry brings up an interesting point. We’re about to enter an era of government where it’s likely no bills will be passed. How will Democrats hang onto their popularity among American voters going into 2020?

nrakich: Well, I wouldn’t say they’re popular exactly. Just more popular than Republicans at the moment.

According to exit polls, only 48 percent of 2018 voters had a favorable opinion of the Democratic Party, while 47 percent had an unfavorable opinion. Not great, but at least slightly better than how Republicans were viewed: 44 percent of voters had a favorable opinion, and 52 percent had an unfavorable opinion.

perry: I would make the case that politically, very little that the House Democrats do really matters, unless they impeach Trump, which I think they are unlikely to do.

The best thing the House Democrats can do is keep the focus on Trump — and things he does that are not popular.

clare.malone: Well, inevitably, they’ll get distracted from that task. They’ve got to nominate a single individual to run against Trump.

And I think a Democrat would also say that making the presidential election about Trump is a risky proposition. It’s not just a midterm in 2020.

sarahf: Right, Nancy Pelosi did her best to make the midterms about health care (and not Trump) after all.

perry: What the House Democrats should do and what the 2020 candidates should do are related but different tasks. The former can try to avoid doing anything too interesting, but the candidates have to say how they would govern as president, which will be more controversial.

sarahf: And I would think depending on how special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation unfolds, that could hurt Democrats in the polls. Although, it’s far too early to say at this point.

But OK, we’re getting away from the idea of the blue wave narrative. Let me see if I can recap: We all think a blue wave happened, yes? It just wasn’t as big as what we saw with Republicans in 2010, but it was still a blue wave. Does what happens in Florida or Mississippi shift this narrative again?

nrakich: I don’t think I’d say that, Sarah.

The popular vote is going to be more Democratic than it was Republican in 2010.

And as Nate tweeted the other day, when you account for how many seats Democrats gained in 2008 (a lot) and Republicans gained in 2016 (not many), the two parties’ net midterm hauls look about the same.

Here's one last way to look at it.

In the first two years with Obama as party leader, Republicans gained a net of +43 House seats (-21 2008, +1 special elections, +63 2010)

In the first two years with Trump, Dems are on pace for +45 (+6 2016, +1 special elections, +38 2018).

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) November 10, 2018

sarahf: So what you’re telling me is it’ll be like the 2016 presidential election: Democrats win the popular vote but not the Electoral College?

natesilver: I’m not really sure how much of a chance Bill Nelson has in Florida. If Mike Espy somehow wins the runoff in Mississippi, that would be … interesting? But that probably involves super low turnout and/or Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith committing more gaffes. It’d probably be a bit of a one-off scenario.

perry: If Democrats won Florida, that would shift the narrative, because it would make it seem more likely they could win Florida in 2020. But it shouldn’t shift the narrative — in theory, the Democrats can win Florida in 2020 regardless of whether Nelson wins Florida by half a point or loses it by half a point.

nrakich: If Nelson somehow wins Florida and Espy somehow wins Mississippi, I think you’re going to see Democrats’ ears perk up quite a bit.

But that’s pretty darn unlikely.

perry: If Espy won, that would just be weird. Trump is still going to win Mississippi — it would suggest that Hyde-Smith is just a bad candidate — which seems true, by the way.

natesilver: But, again, Democrats won most of the Senate races in swing states. Arizona, Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia (if it’s still considered a swing state), Wisconsin, Minnesota, etc. Florida is the only real exception.

And that’s the tip-off that it’s a wave election: You’re winning in the swing states and/or districts, that you lost in two years earlier.

sarahf: So the question I suppose moving forward and looking ahead to 2020 is just how lasting this “blue wave” will be. Will we see a shift back to the GOP in Midwestern states after some of them moved pretty far to the left in this last election? Because it does seem as though Democrats need to win in the Midwest to stand a chance in the Electoral College.

nrakich: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Remember what happened after the 2010 Republican wave. Obama won re-election. Waves aren’t predictive of future elections.

clare.malone: I think it’ll depend on who the Democratic presidential nominee is.

natesilver: It’s probably too early to look at, say, Trump’s approval rating and predict that means he’ll have a tough time getting re-elected. Approval ratings two years out aren’t really predictive at all.

With that said, he doesn’t seem to have any instinct to course-correct.

And what we know now is that his party performs basically how you’d expect them to perform based on the polls, which is to say, not good, when you’re sitting at a 42 percent approval rating.

nrakich: The big indicators I’m looking at for 2020 and where Democrats stand will be (a) the outcome of the Mueller investigation, (b) the state of the economy and (c) as Clare said, who Democrats nominate.

perry: I’m of the view that (a) and (c) are much less important than people think and that (b) is really important. But that’s best saved for another chat.

sarahf: For now, suffice it to say, the blue

Yes, It Was A Blue Wave

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): So we’re here today to talk about the midterm elections and the BLUE WAVE … or blue trickle? Which is it, team!?!

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): It was, by any historical standard, a blue wave. Democrats look like they’re going to pick up around 38 House seats, which would be the third-biggest gain by any party in 40 years (after Republicans in 2010 and 1994). The Senate moved in the opposite direction, but not by much, and it was a very difficult map for Democrats anyway.

And Democrats won the House popular vote by 6.8 percentage points, according to preliminary data from the Cook Political Report. And Cook’s Dave Wasserman thinks continued vote-counting in California should bring Democrats to well over 7 points. That would be the third-highest popular vote margin of any election since 1992 (behind Democrats in 2006 and 2008).

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): The arguments that it ISN’T a blue wave are dumb. Can we end the chat now and get lunch?

sarahf: Haha, no. We’re here to tell readers why it’s dumb — although Nathaniel did do a pretty good job of convincing me.

nrakich: People seem to be defining “blue wave” as, “Did Democrats outperform expectations?”

They’re forgetting that expectations were already for a blue wave.

natesilver: What is the argument that it isn’t a blue wave? That Democrats didn’t win the Senate?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Fun chat.

nrakich: Democrats largely matched expectations in the House but fell a little bit short of them in the Senate and governor races.

clare.malone: Let’s step out of the numerical zone for a second, then, and engage with why some people are NOT interpreting it as a “blue wave.”

I think it says something about the political environment that Democratic voters wanted that overarching rebuke to President Trump.

I’m guessing a lot of people thought Democrats could win the Senate because they weren’t paying attention to politics that closely. Or more precisely, the electoral apportionment part of politics. I don’t blame regular people for that. Now, I think we can criticize media outlets …

natesilver: I think they’re arguing it’s not a wave because (1) the “split decision” narrative is very attractive if you’re of a both-sides mentality, (2) it takes a little bit of work to figure out why Democrats didn’t win the Senate (i.e., you have to look at the fact that the contests were all held in really red states), (3) Democratic gains are larger than they looked like they’d be at say 10:30 p.m. on election night, when these narratives were established.

nrakich: I understand why Democrats are disappointed, Clare. They lost the Senate! You’d rather win than lose! But we should educate them that a loss of two, maybe one, seats in the Senate was actually a remarkable feat for Democrats in this Senate map.

natesilver: Ehhhhhhhhhhhhhh

I think that’s going a little too far.

nrakich: Democrats were so overexposed that, in a different environment, Republicans could have taken 60 seats in the Senate and made it really hard for Democrats to take back the Senate in the next decade or more.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): The Atlantic’s Ron Brownstein has a good case complicating the idea of a blue wave:

On Tuesday, a divided America returned a divided verdict on the tumultuous first two years of Donald Trump’s presidency. Rather than delivering a “blue wave” or a “red wall,” the election produced a much more divergent result than usual in a midterm.

Democrats made sweeping gains in the House, ousting Republicans in urban and suburban seats across every region of the country to convincingly retake the majority for the first time since 2010. …

But Republicans expanded their Senate majority across a belt of older, whiter heartland states.

It’s worth considering the idea that, yes, Democrats made gains. But the shift of white, working-class voters to the GOP that has been happening for a long time became clearer in 2016 and remained unchanged in 2018. A certain kind of voter — largely suburban — broke with Trump and the GOP, but Republicans look really strong in rural and white, working-class America.

natesilver: On the narrower point about the Senate — yeah, Democrats would have lost a bunch of seats in a neutral environment. But there was no reason to expect a neutral environment. The default is that the “out” (non-presidential) party does pretty well, especially under unpopular presidents.

So I think people who were like “Democrats are gonna lose six Senate seats” didn’t have the right prior.

nrakich: Sure, Nate, but I’m comparing it to a world in which Hillary Clinton won the presidency.

Although, frankly, Democrats still could have lost more seats with a Republican as president.

If Jeb Bush had won the 2016 election and the economy was still humming along, the generic congressional ballot might have been D+3, instead of D+9, and Democrats would have lost four or five Senate seats instead of two.

sarahf: Right, but this was supposed to be a rebuke on a president that has defied American norms! I guess I kind of find Brownstein’s argument in the piece that Perry shared convincing — the midterm elections didn’t wind up solidly in either party’s win column; rather it showed just how divided America remains.

nrakich: It was a rebuke!

It’s just that we’ve known that it was going to be that since early 2017. So it was already priced in in everyone’s minds.

sarahf: So does it mean that Democrats just can’t win in Missouri, Indiana and North Dakota (states where Democratic incumbents lost Senate contests last week) because those states are just too red now? Even though Democrats had a sweeping victory in the House, this year’s Senate map underscored some big electoral challenges that they will face moving forward — i.e., Democrats better hope the Midwest continues to move to the left, because I think we saw that the Sun Belt is still a ways away from shifting.

nrakich: Don’t think of what happened in the Senate in terms of gains and losses for Democrats. Instead, think of the raw number of seats they won: at least 24 out of the 35 Senate seats on the ballot this year (we still don’t know who won yet in Florida or the Mississippi special election).

Considering that 18 of the 35 Senate seats up this year were in red states, it’s impressive that Democrats took a majority of them.

sarahf: What I’m hearing is that despite losses in the Senate, Democrats did well under the circumstances. But I wonder what you all make of the fact that Democrats didn’t pick up a single rural district?

natesilver: The average tipping-point Senate seat was in an R+16 state. The average tipping-point House seat was R+8.

So that tells you something: Democrats had no problem winning in R+8-type districts, which is pretty good, but the R+16 is a bridge too far in a world of high partisanship (at least for their incumbents in the Senate). Their incumbency advantage was just too small.

sarahf: But then how do we explain Montana and West Virginia? Those are both very red states, R+17.7 and R+30.5, respectively, and both of the Democratic incumbent senators there won on Tuesday. Is it just because of a strong incumbency advantage? Or is it that both states have small populations and more elastic voters?

It’s hard for me to believe that a winning electoral strategy for Democrats is to not court voters in more rural, red states and just ride out incumbency as long as possible.

But it seems as if that might be where Democrats are headed? That partisanship matters more than ever and Democrats trying to win Arizona and maybe Texas are the future? (Although, I have to say Texas leans pretty Republican at R+16.9).

natesilver: I mean, some incumbents are certainly stronger than others. There’s still variation around a mean. But the mean is one where partisanship is strong and incumbency is weak.

clare.malone: Montana has a bit of that Western streak, so it favors its guy (perhaps another key distinction), and the incumbency advantage works better there. West Virginia has a pretty conservative Democrat in Joe Manchin and a guy with good name recognition in the state.

perry: I think the wave happened and that Democrats had a great night. I do think, at the same time, that the election reinforced some of the weaknesses of the Democratic Party. For instance, Barack Obama won Indiana in 2008, but Sen. Joe Donnelly lost there last week. Obama won Ohio in 2008 and 2012. And, yes, Sen. Sherrod Brown did win his re-election bid, but Democratic gubernatorial candidate Richard Cordray lost. It makes me think Ohio is starting to look more like a GOP state now (considering how easily Trump won there in 2016).

I would also say that Trump is the 2020 favorite in Iowa and Florida, considering his victories in 2016 and the GOP performance in those states last week: Republican incumbent Gov. Kim Reynolds won in Iowa, and it looks as though the Republican candidate will win in Florida’s Senate and gubernatorial races.

nrakich: Right. It can be a blue wave while still flagging danger spots for Democrats in future elections.

But for now, Democrats — relax and enjoy.

sarahf: I don’t know. The 2020 Senate map looks tough, though not as bad as this year’s, I realize.

clare.malone: I think on an emotional level, to bring it back to why people are having mixed reactions, the “blue wave” confirmed that there are deep divisions in the country that people have been hearing all about.

perry: I don’t think Democrats can relax and enjoy this, because I think the 2018 midterm results suggest that Trump could very much still win in 2020. That was obvious pre-election to me, but I’d say it’s even more obvious now.

clare.malone: Right? To us, maybe.

But not to a lot of people.

Also, I think Democrats got bummed that the candidates with emotional resonance didn’t win — Beto O’Rourke in Texas, Stacey Abrams in Georgia, and Andrew Gillum in Florida (both Abrams and Gillum are obviously still tbd, but it doesn’t look good for Democrats).

nrakich: And the only, like, Democratic “revenge” win was defeating Gov. Scott Walker in Wisconsin.

clare.malone: Right.

natesilver: Some of the bigger Democratic wins didn’t get called until later in the night. The Wisconsin governor was a big one. And then there are the Senate pickups in Nevada (called late) and Arizona (which didn’t get called until Monday).

nrakich: Agreed, Nate — there’s anchoring bias going on here. People’s narratives got baked at 10 p.m. on election night, when Democrats weren’t doing as well as they are now, and they’ve been slow to update them.

natesilver: Democrats also had a good night in Michigan, although Sen. Debbie Stabenow’s margin was a little closer than expected. And a very good night in Wisconsin.

perry: Yeah, the 2020 map looks better for Democrats than I expected in a few places. Pennsylvania looks really strong for them, and Arizona is probably a real 2020 swing state.

sarahf: Here’s a thought. There was a blue wave — but it was fueled by Democratic moderates.

Is that accurate? Was there perhaps some disappointment among Democrats who didn’t see as big of a progressive change as they’d hoped?

clare.malone: It’s interesting, Sarah. Because we do find some evidence that the swing-y voters in this election were people that used to vote more Republican.

natesilver: But, like, there’s a downside to the Trump coalition. Say there are maybe 22 or 23 states that are really, REALLY Trumpy, but then the median district is not.

In the Senate, that could actually work out super well for Trump. But it’s a problem for the Electoral College and for the House.

perry: On Sarah’s point, I’m not sure how easy it is to define who is a “moderate” or a “liberal” in today’s Democratic Party. Tammy Baldwin (she supports “Medicare-for-all”) is quite liberal, and she won. Democrat Lucy McBath made her candidacy for the House in Georgia increasing gun control and still won. Sherrod Brown of Ohio is fairly liberal. But Arizona Sen.-elect Kyrsten Sinema is more of a centrist.

The whole moderate-liberal thing is very complicated. Are we really talking about (1) a candidate’s policy position (i.e., do you support liberal ideas like “Medicare-for-all”?), or 2) a candidate’s posture (i.e., are you anti-establishment and branded in the style of Bernie Sanders, or are you pro-establishment and more like Clinton or Obama?)

sarahf: That’s true, Perry. Still, it’ll be interesting to see what governance looks like with this new Democratic House.

perry: I think the first bill in this new House will be some kind of election proposal: Try to limit gerrymandering, strengthen the Voting Rights Act, etc.

nrakich: That’d be a smart move for Democrats, Perry. If Democrats want to hold onto power, they need to start by addressing the structural factors that currently hold them back.

natesilver: Yeah, the ballot proposals were another bright spot for Democrats, and a lot of them were electorally oriented — i.e., make it easier for more people to vote.

That’s something that could pay dividends down the road. And also something that Democrats are likely to replicate in the years ahead, I’d think.

nrakich: Automatic voter registration in Michigan and ending felon disenfranchisement in Florida are two big ones for Democrats, I’d say.

Although we should caveat this by saying that those ballot measures won’t turn Michigan and Florida into safely blue states overnight. But they could add several thousand votes, which would be enough to tilt a close election — like we’re currently seeing in Florida, coincidentally.

perry: Proposals on voting measures unite Democrats. And I actually think some of the talk about House Democrats being divided is over-hyped. Because in an environment where it’s unlikely that major bills will be passed, does it really matter if some Democrats are in favor of “Medicare-for-all” while others are in favor of expanding Medicaid? Neither of those things will pass. Nor will Immigration and Customs Enforcement be abolished while Trump is in office.

sarahf: Perry brings up an interesting point. We’re about to enter an era of government where it’s likely no bills will be passed. How will Democrats hang onto their popularity among American voters going into 2020?

nrakich: Well, I wouldn’t say they’re popular exactly. Just more popular than Republicans at the moment.

According to exit polls, only 48 percent of 2018 voters had a favorable opinion of the Democratic Party, while 47 percent had an unfavorable opinion. Not great, but at least slightly better than how Republicans were viewed: 44 percent of voters had a favorable opinion, and 52 percent had an unfavorable opinion.

perry: I would make the case that politically, very little that the House Democrats do really matters, unless they impeach Trump, which I think they are unlikely to do.

The best thing the House Democrats can do is keep the focus on Trump — and things he does that are not popular.

clare.malone: Well, inevitably, they’ll get distracted from that task. They’ve got to nominate a single individual to run against Trump.

And I think a Democrat would also say that making the presidential election about Trump is a risky proposition. It’s not just a midterm in 2020.

sarahf: Right, Nancy Pelosi did her best to make the midterms about health care (and not Trump) after all.

perry: What the House Democrats should do and what the 2020 candidates should do are related but different tasks. The former can try to avoid doing anything too interesting, but the candidates have to say how they would govern as president, which will be more controversial.

sarahf: And I would think depending on how special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation unfolds, that could hurt Democrats in the polls. Although, it’s far too early to say at this point.

But OK, we’re getting away from the idea of the blue wave narrative. Let me see if I can recap: We all think a blue wave happened, yes? It just wasn’t as big as what we saw with Republicans in 2010, but it was still a blue wave. Does what happens in Florida or Mississippi shift this narrative again?

nrakich: I don’t think I’d say that, Sarah.

The popular vote is going to be more Democratic than it was Republican in 2010.

And as Nate tweeted the other day, when you account for how many seats Democrats gained in 2008 (a lot) and Republicans gained in 2016 (not many), the two parties’ net midterm hauls look about the same.

Here's one last way to look at it.

In the first two years with Obama as party leader, Republicans gained a net of +43 House seats (-21 2008, +1 special elections, +63 2010)

In the first two years with Trump, Dems are on pace for +45 (+6 2016, +1 special elections, +38 2018).

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) November 10, 2018

sarahf: So what you’re telling me is it’ll be like the 2016 presidential election: Democrats win the popular vote but not the Electoral College?

natesilver: I’m not really sure how much of a chance Bill Nelson has in Florida. If Mike Espy somehow wins the runoff in Mississippi, that would be … interesting? But that probably involves super low turnout and/or Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith committing more gaffes. It’d probably be a bit of a one-off scenario.

perry: If Democrats won Florida, that would shift the narrative, because it would make it seem more likely they could win Florida in 2020. But it shouldn’t shift the narrative — in theory, the Democrats can win Florida in 2020 regardless of whether Nelson wins Florida by half a point or loses it by half a point.

nrakich: If Nelson somehow wins Florida and Espy somehow wins Mississippi, I think you’re going to see Democrats’ ears perk up quite a bit.

But that’s pretty darn unlikely.

perry: If Espy won, that would just be weird. Trump is still going to win Mississippi — it would suggest that Hyde-Smith is just a bad candidate — which seems true, by the way.

natesilver: But, again, Democrats won most of the Senate races in swing states. Arizona, Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia (if it’s still considered a swing state), Wisconsin, Minnesota, etc. Florida is the only real exception.

And that’s the tip-off that it’s a wave election: You’re winning in the swing states and/or districts, that you lost in two years earlier.

sarahf: So the question I suppose moving forward and looking ahead to 2020 is just how lasting this “blue wave” will be. Will we see a shift back to the GOP in Midwestern states after some of them moved pretty far to the left in this last election? Because it does seem as though Democrats need to win in the Midwest to stand a chance in the Electoral College.

nrakich: ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Remember what happened after the 2010 Republican wave. Obama won re-election. Waves aren’t predictive of future elections.

clare.malone: I think it’ll depend on who the Democratic presidential nominee is.

natesilver: It’s probably too early to look at, say, Trump’s approval rating and predict that means he’ll have a tough time getting re-elected. Approval ratings two years out aren’t really predictive at all.

With that said, he doesn’t seem to have any instinct to course-correct.

And what we know now is that his party performs basically how you’d expect them to perform based on the polls, which is to say, not good, when you’re sitting at a 42 percent approval rating.

nrakich: The big indicators I’m looking at for 2020 and where Democrats stand will be (a) the outcome of the Mueller investigation, (b) the state of the economy and (c) as Clare said, who Democrats nominate.

perry: I’m of the view that (a) and (c) are much less important than people think and that (b) is really important. But that’s best saved for another chat.

sarahf: For now, suffice it to say, the blue

November 12, 2018

Politics Podcast: A Post-Midterms 2020 Draft … Live!

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Live from the 92nd Street Y in New York, the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast team ranks the politicians that seem most likely to win the 2020 Democratic presidential primary in the wake of the 2018 midterm elections. The crew also reacts to the latest tallies from races where ballots are still being counted.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN App or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with occasional special episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers