Nate Silver's Blog, page 70

March 22, 2019

Does A Biden-Abrams Ticket Make Sense For Biden Or Abrams?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): On Thursday, political Twitter was abuzz with the news that former Vice President Joe Biden (a still undecided 2020 Democratic contender) was considering launching his campaign with Stacey Abrams, a rising star in the Democratic Party who narrowly lost Georgia’s governor race last year, as his vice president pick.

The news has both been criticized as a tokenization of Abrams and celebrated as a strategic move for maybe both of them, but what do we make of it?

And setting aside some of the thorny issues this raises for Biden, how common is it to launch a presidential campaign with a vice president already picked?

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): I don’t recall an obvious precedent for this. In 2016, Sen. Ted Cruz said he would make Carly Fiorina his vice presidential pick if he won the GOP nomination, but that was a last-ditch move in April 2016 when it was clear he was going to lose the Republican primary.

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): Not common.

But maybe this is a case where the norm — picking your VP later in the presidential season — isn’t necessarily the most logical practice. Under current norms announcing a VP so early looks like a desperate ploy for media attention (and not an unsuccessful one), but it also raises an interesting question: Why not pick a VP early so that voters have time to make a more informed decision? Political scientist William Adler has written on the perils of picking a running mate early, but maybe that is a norm that should change.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Yeah, the “desperate ploy” thing seems a little circular to me. It’s a desperate ploy because the media decides it’s a desperate ploy? There’s not really any objective basis for that statement, though, insofar as I can tell.

It’s an unusual ploy, though, which means it’s hard to characterize when candidates have used it, since it’s so rarely been tried.

For Cruz, it was a desperate ploy, I suppose, because his chances of winning the primary were quite small at that stage.

sarahf: Right, so because most campaigns aren’t launched with both a president and VP pick out the gate, what would incentivize Biden to do that even if it risks coming across as hamfisted?

natesilver: Well, one incentive is Stacey Abrams. I don’t think this is really a discussion if, I don’t know, Biden is running with California Rep. Eric Swalwell as his running mate or something. Abrams, on the other hand, is high-profile, talented, could be a very effective surrogate and could obviously help him with black voters.

I don’t know why she’d be eager to do it, though.

perry: There is a charitable way to view this. The Democratic Party in some ways is more a a coalition of groups than a movement based on ideology. It includes whites/non-whites, liberals/moderates, women/men, young/old in a way that the GOP does not. (Put another way, the GOP is more homogenous.) And a Democratic ticket is always a bit of an attempt to build a coalition. So Biden signaling early on that he respects the party’s younger, non-white, female and more liberal people is a good thing for him to do. And also, Biden was on a coalition ticket before and played the lesser role, while Barack Obama represented the non-white, younger part of the party. I don’t necessarily begrudge him for now wanting to be in the lead role.

julia_azari: One of the first things I saw this morning was about a one-term pledge associated with the Abrams idea. This sounds like it would be effective but has some … off-ramps in practice.

sarahf: I understand the advantage this poses for Biden, but why Abrams would prefer this to launching her own campaign (maybe she’s concerned the field is too large) or running for the Senate in Georgia (Georgia is still a very red state) is less clear to me.

perry: Would Abrams consider being Biden’s VP if he was the nominee in June 2020?

Yes. So in some ways, we are just moving up the timetable. It seems like she wants to be president, and this is a pretty direct way to get there.

natesilver: Well, maybe. But shouldn’t she preserve the option of being someone else’s VP? Or more to the point … running herself?

sarahf: Right, like if I’m Abrams, why not shop around for another ticket if being VP is an attractive next stop for me.

Why commit now? What does she have to gain?

perry: But is Biden actually saying that they are running on a joint ticket from Day 1? Or is he saying that he will pick Abrams no matter what, unless she is otherwise occupied?

If it’s the latter, then on some level, Abrams is a free agent, except for not running for the Senate in 2020.

Biden met with Abrams last week, but at least according to Abrams’s camp, Biden did not formally request to run on the same ticket. Lest we forget, people close to Biden floated something like this with Elizabeth Warren in 2015.

So I get the sense people close to Biden, if not Biden himself, are trying to figure out how to present him in a way that acknowledges that that the party is no longer one of old white guys, even as Biden is an older white man.

julia_azari: The vice presidency is a weird place for a rising star — former House speaker Paul Ryan (and the other half of the Romney-Ryan presidential ticket in 2012) was somewhat unusual in that regard. In modern politics, the VP nominee has often been either someone plucked out of more obscurity (such as Sarah Palin) or someone who has already retired from Congress.

natesilver: And Abrams has quite a bit to lose by committing to Biden, I think. If Biden flops — and there’s a 75 to 80 percent chance he won’t be the nominee, per prediction markets — she could wind up being this weird footnote in a Fiorina kind of way.

perry: But announcing a presidential ticket early could be a good idea. What if Warren or Kamala Harris or Beto O’Rourke or Bernie Sanders came out with a running mate too? That’s not the worst idea, to me.

It would give voters (and me) a sense for how they’re trying to balance the different parts of the Democratic Party.

julia_azari: Yeah, that was my point earlier. It’s not a bad idea on the merits, but because Biden has taken some stances that have negatively impacted black Americans, it sends weird signals in context.

But also everything is weird this year.

perry: Right, the reason this is getting covered as a bit token-ish is, of course, because of Biden’s past. A spokesman earlier this month said that Biden still believed his stance of opposing busing was right. This is also the man who was chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee that oversaw Anita Hill’s testimony in the early 1990s.

natesilver: Yeah. Look, right now there are three white guys who are leading candidates (Beto O’Rourke, Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden) and a couple of others who have an outside chance to win. Any of those white guys could find Abrams to be a rather intriguing choice, for racial/gender balancing and for other reasons. A Beto/Abrams ticket could be sort of the modern equivalent of Clinton/Gore, for instance, doubling down on a young ticket of “outsiders.”

Bernie/Abrams is kind of an interesting ticket, too, especially since he hasn’t always done great with African-American voters. So why lock yourself into Biden?

julia_azari: Yeah, but why lock yourself into being a VP at all?

sarahf: I guess because you and your advisors think Biden has a reasonable chance of winning so why pass at the chance?

perry: Abrams has to figure out: Would Biden actually listen to her? Does he respect her? Or is this just him picking a black person who’s also a woman and a younger person as window dressing?

julia_azari: The role of VP has a lot of ambiguity.

You can be a serious governing partner or you can go to state funerals that the president doesn’t want to attend.

And it can be hard to carve out your own political identity afterward. Just ask Presidents Al Gore and Hubert Humphrey. :wink:

sarahf: To the earlier point about why we’re having this conversation … say it was Sanders and not Biden, do you think the reactions would be similar here?

natesilver: I’m not convinced that the reactions are Biden-specific. Maybe there’s more salience to Biden’s VP pick because he’s old and/or will potentially take a one-term pledge. But mostly it’s just very unusual to pick a VP in advance and that’s why it’s being scrutinized.

perry: Sanders has been somewhat clumsy in how he talks about race so I think the question of tokenism would be just as strong with him. That said, it would have the same advantages for Sanders — he would be reaching out to part of the party that he is not a part of.

natesilver: By the way — it’d also be a different situation if, like, we’re in November/December, Biden is now up to 36 percent in the polls, seems pretty likely to be the nominee, is running a much stronger campaign than in 1988/2008, and thinks Abrams could put him over the top. That makes a lot more sense for her, and maybe for him, too.

perry: She would also have a sense of what kind of campaign Biden is running.

Abrams has specific issues (namely voting rights) that she has been very passionate about that don’t fit neatly with the what I assume will be Biden’s approach: projecting bipartisanship and an appeal to Obama-Trump voters in the Midwest. Abrams would probably want to make sure Biden’s campaign would appreciate her speaking to those issues first.

That said, Biden has pretty high favorability with black voters, so I don’t know if he needs Abrams.

But OK, we agree that this is not great for Abrams, but probably is for Biden (if she said yes)?

sarahf: I’m not sure how Biden loses in this. It’s a question of what Abrams wants to do and if it’s smart for her.

natesilver: Keep in mind that Biden, again, has only a 20-25 percent chance to win (per prediction markets). That’s pretty unlikely. So it makes sense for him to take risks!

perry: So is this good for the Democratic Party if it happens?

The other candidates?

julia_azari: Well, it’s possible that all the candidates will pick running mates and then we’ll have 40+ people in the mix.

sarahf: Just think, we could launch a separate “theory of the case” series on VP picks!

julia_azari: I would contribute to that series.

natesilver: I think there might be a world in which there’s a shift in norms from naming the VP only after you’ve clinched the nomination. You do it at some point earlier in the process. I think that might serve the best interests of voters; depending on when the VP was announced, some voters would know in advance who the VP was instead of having to guess.

julia_azari: Yeah, I think that’s right, and these norms have shifted recently. I think John Kerry started the current norm of announcing a VP pick a bit before the convention.

natesilver: But does this particular instance make sense or advance the interests of the Democratic Party? I’m not sure. I don’t like the idea that — to be honest — Beto gets to run his own campaign, but Abrams (who has similar credentials in many respects) has to be the No. 2 to a different white guy.

That said, there’s one other issue we haven’t focused on much, which is that leaving the VP slot open could give you a lot of leverage in the event of a contested convention.

Or rather, filling it in advance could cost you that leverage.

julia_azari: Ooh the contested convention dream! (Please this time …)

natesilver:

Like, what happens if Biden has 40 percent of the delegates and — I don’t know — Julian Castro is in second place with 30 percent. Castro agrees to encourage his delegates to vote for Biden if he gets Biden’s VP spot, but Biden has to kick Abrams off the ticket first? How’s that work?

sarahf: It doesn’t.

julia_azari: It could even pose an issue in the less formal winnowing process between now and the convention.

perry: I don’t know if Biden is being presumptive (and acting like he is the frontrunner) or not. If he is assuming Abrams is not running for president or is not a strong candidate who could be polling ahead of him in a month, it is presumptive in that sense.

But I actually think this is a sign of Biden’s weakness as a candidate that he wants to get a younger, perhaps more dynamic figure running with him. And if I’m one of the other candidates, I might be happy that Biden and his advisers are already kind of nervous about being the older white man in the primary and feel like they need to add some juice.

natesilver: I suppose I’d posit a subtle distinction between being a sign of weakness and looking desperate.

Like, it can be Biden acknowledging that he has some challenges, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it would look bad to voters.

But again,if Abrams is such a strong candidate that she’d move the needle all by herself as a VP — and maybe she is — shouldn’t she run for the top of the ticket instead?

perry: Yes.

julia_azari: Biden picking Abrams at the normal time is acknowledging that he has some challenges. But IMO making a pick this early has a whiff of desperation and seeking attention.

But I have become a broken record or whatever the kids who don’t know what records are say now.

natesilver: People listen to CD’s now, Julia — not records.

julia_azari: Thank you, Nate, for the update to 1997.

natesilver: Beto and Abrams both performed very well as compared to the usual baselines in 2018, both in terms of coming so close to winning in a red state and getting a huge turnout. And I think Beto has had a good debut, all things considered. So Abrams should think about running too!

perry: I have in my head that there is only room for one black person to run and do well. That may be true, but the Democratic Party is about 20 percent black — so three black candidates in a field of 15-20 is fine.

And Abrams does have something special. She ran in 2018 and did really well, gaining a national following. She is a Southern black woman with a very distinctive narrative — she would be unique to this current field of candidates.

natesilver: Yeah, it’s hard to put my finger on, but I think she has a pretty different constituency than Harris and Booker. I’m not quite sure what Booker’s constituency is, by the way — I don’t mean that in a bad way, just that he’s one of the campaigns that could go in a lot of different directions.

julia_azari: She’s more outsider-y.

If anyone can come up with a better word for outsider-y please help.

perry: At the same time, Abrams will have to deal with the Democratic voters-as-pundits/electability experts asking “Can she win white voters in the Midwest?”, which is problem many of the female candidates face. Also, Abrams has maybe a 45 or 48 percent chance of being a senator?

That’s pretty good. She might think the Senate is boring, but it’s still a national platform.

natesilver: I’d say lower than that. Georgia is still a red state, albeit verging on purple, and she’s running against an incumbent, albeit not an especially scary incumbent.

One thing I would say: The candidates with relatively nontraditional credentials (Pete Buttigieg, Beto, even Andrew Yang!) seem to be doing fairly well so far. And that works for Abrams too, potentially.

julia_azari: This is a problem throughout the Democratic field, no? People from states that are still pretty red don’t have other pathways to advancement (I’m thinking Buttigieg, Beto and Julian Castro).

natesilver: Yeah, in a world where 75 percent of states are super polarized, you aren’t going to have a lot of Democratic senators/governors in red states, or a lot of Republican ones in blue states.

And the ones you do get are going to be the Charlie Baker/Joe Manchin types who are probably too centrist to run for their party’s presidential nominations.

So I do think you have to give credit to candidates who come close to winning office in these states, or who hold some lesser office.

julia_azari: Right. So geographic polarization has helped expand presidential fields, maybe?

natesilver: I do think that’s a trend. Voters and the media can vet over the next 15 months whether, say, Buttiigeg has the requisite experience and skills to become president. But I don’t think that he should be preemptively disqualified because obtaining higher office in his home state would be difficult.

sarahf: Which could make a national office like the presidency or vice presidency extra attractive. It’s just a matter of what Abrams’s decides to do. Speaking of which, how should Abrams treat this?

perry: I would be very surprised if Abrams committed to being Biden’s running mate this early.

He will face plenty of pressure to pick a woman and person of color if he is the nominee.

So Harris and Abrams, if they are not the nominee themselves, will be high on his list no matter what.

natesilver: It’s hard for me to imagine that Abrams lands in a spot where she’s willing to commit to running for VP, but not running for president.

March 21, 2019

Live From New York … It’s A 2020 Draaaaaft!

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

In a live taping of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast in New York City, the crew competes in a draft of the 2020 Democratic primary candidates. Nate, Clare, Micah and Galen make their arguments for who they think will win the Democratic nomination. They also play “Good Use of Polling or Bad Use of Polling” and give the media (and FiveThirtyEight) a report card for its coverage of the candidates one quarter of the way through the year.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 20, 2019

What Do We Know About Trump’s Re-election Chances So Far?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): With all eyes on 2020, much of the media attention has focused on the growing Democratic field, but what about President Trump’s re-election chances? How vulnerable is he to actually being unseated?

Because we’re in the business of making predictions, we want to avoid making definitive calls here, but let’s critically examine Trump’s re-election odds. What’s the case for Trump cruising to re-election? And what’s the case against betting on Trump?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): The case against Trump is that he’s pretty darn unpopular. The case for Trump is that the Democratic nominee might be pretty darn unpopular too.

sarahf: In other words, 2016 all over again.

natesilver: Yeah. A huge question is whether Clinton’s performance was unique to Clinton and her particular problems, or whether her position was closer to a “generic Democrat.” If it’s the former, Trump is an underdog. If it’s the latter, he might be the favorite.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Part of the question is whether you think Hillary Clinton was uniquely unpopular or that by 2020, Joe Biden or whoever the Democratic nominee is will be viewed by most Republicans and many GOP-leaning independents as an abortion-loving socialist who hates Midwestern voters and the police, no matter what that person’s actual views are. And, I guess, I take the second view — negative polarization will do a lot of the work in 2020 for Trump.

natesilver: I mean … without getting into the whole “electability” question, I think Biden might be able to avoid that particular characterization.

perry: But will the Biden-Abrams ticket be able to avoid that?

natesilver: Wait, are you breaking some news re: Stacey Abrams?

sarahf: Now if it’s Beto …

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): It’s the age-old question: Is a presidential election a referendum or a choice? If it’s a referendum on the current administration, Trump is in trouble. If it’s a choice between two parties, Trump has a good shot.

geoffrey.skelley (Geoffrey Skelley, elections analyst): To me, “It’s the economy, stupid.” If the economy remains on its present course, some econometrics models would suggest Trump is an even bet or even a favorite to win re-election.

perry: Yeah, I don’t think the economy will matter that much. i.e., wasn’t the economy great in 2018 and Republicans still lost their majority in the House?

nrakich: Maybe the economy right now isn’t relevant, but the economy in 2020 will be.

natesilver: The notion that a good economy helps incumbents is broadly right, but fundamentals models can be overrated, and some of them are badly designed.

If I’m Trump, I’d be a little scared that my approval rating is only at 41 or 42 percent when the economy is quite good.

perry: If the economy is terrible, will that hurt Trump? Sure. But is the reverse true? Could he lose with a great economy? I think so.

natesilver: I’m not an economic forecaster, but I know that the economy is mean-reverting, meaning that since it’s good now, it’s more likely to get worse than better.

And if Trump’s approval is at 41 or 42 percent with a good economy, where does that put him with a mediocre economy?

nrakich: He definitely has more downside than upside, IMO. Like, it’s harder to see things getting much better for Trump. But it could definitely get worse, if there’s a recession or if special counsel Robert Mueller’s report is really bad for him.

Right now, Trump looks like an even bet for re-election. But the status quo is probably his best-case scenario.

natesilver: I wouldn’t say it’s his best case. You could have 6 percent GDP growth! Who knows!

geoffrey.skelley: All this suggests to me that Trump’s re-election chances are tied to the economic news remaining positive. If that happens, I agree with Nathaniel that he’s a 50-50 bet. If we hit a recession or near-zero growth, I think that makes him an underdog.

natesilver: I’d guess it’s something like: 20 percent chance the economy gets really bad, 30 percent chance it gets worse but doesn’t go into recession, 30 percent chance it stays about the same, 20 percent chance it gets better. Something like that.

nrakich: One wild card could be a national security threat. If (god forbid) there is a terrorist attack or we get into another war, we can throw all this out the window.

sarahf: But regarding Trump’s status quo, how bad is it really? For the last two years, his approval rating has consistently hovered between the high 30s to the low-to-mid 40s. How important is a president’s approval rating this far out in determining whether he wins re-election?

natesilver: It’s a little early now. Actually, a lot early. Historically, presidential approval ratings at this point are only loosely correlated with what they’ll look like two years later. (Or a year-and-a-half later.)

However, Trump’s approval ratings have been bounded within a very narrow range, so maybe there’s more predictability.

nrakich: Fun fact: Trump’s approval rating right now is right around where Ronald Reagan’s was at this point in his presidency. (And he won re-election.)

natesilver: But Trump also isn’t doing the things that a president would normally do to improve his approval rating. Instead he’s doubling down on his base, which isn’t a winning strategy as the GOP base is smaller than the Democratic base.

If you incepted Trump’s brain and made him stop doing dumbass shit, he’d be a favorite for re-election, but I’m not sure the actual Trump is.

perry: I liked this piece (“Why Trump Will Lose in 2020”) from Rachel Bitecofer. Not necessarily because I agree with her prediction (I have no idea), but because it shifted the conversation around Trump’s re-election changes from the candidates to the voters:

“The surge won’t be uniform. Democrats will win big in more urban, more diverse, better-educated and more liberal-friendly states and will continue to lose ground in other states like Missouri. Although Mr. Trump may well win Ohio and perhaps even Florida again, it is not likely he will carry Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania in 2020. Look at the midterm performance of statewide Democrats in those states. And his troubles with swing voters, whom he won in 2016, will put Arizona, North Carolina and perhaps even Georgia in play for Democrats and effectively remove Virginia, Colorado, Nevada and New Hampshire from the list of swing states.”

The question here is, are voters fairly set on being anti- or pro-Trump already? Because your assumption about Trump’s chances are in part about:

How many swing voters there are.

Where they are located.

If t Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania are already lost for Trump.

natesilver: I suppose I think it’s premature to look at the Electoral College, and I’d take more of a top-down/macro than bottom-up/micro view at this point.

geoffrey.skelley: Yeah, a Democrat’s position in rural Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin could get worse.

Maybe Democrats nominate someone who is a bit too left-leaning for affluent whites in the suburbs.

natesilver: Overall, the Electoral College is more likely to help Trump — as it obviously did in 2016 — than to hurt him, but the Electoral College advantage bounces around a lot with relatively subtle shifts in coalitions. Obama overperformed in the Electoral College in 2008 and 2012, for instance.

Clinton was sort of stuck in between two things. She overperformed previous Democrats in the Sunbelt (e.g. Texas and Arizona), but not by enough to win those states. And she underperformed in the Midwest, where she came close in a lot of states but didn’t win.

sarahf: But to Perry’s question of whether voters are already set on a candidate, it seems to me that the answer is no, at least as far as the Democratic primary candidates go. Which raises another question I have about Trump’s re-election odds … what evidence do we have that voters aren’t taking Trump’s candidacy seriously?

I ask, as early polls seem to indicate that Democrats are taking his candidacy very seriously.

Two early polls have shown that a high percentage of Democrats are concerned about electability this year, prioritizing a candidate’s ability to defeat Trump over whether or not the candidate’s views closely align with their own.

natesilver: I think “voters/Democrats aren’t taking Trump seriously” is strawman BS, to be honest.

perry: Exactly.

natesilver: Like that’s a very clicky headline/tweet but Democrats are actually much more concerned with “electability” than in the past.

Is the media underestimating Trump’s chances? I don’t know. That’s plausible at least. Sometimes I wish we took a periodic survey of campaign reporters because the proxies that we sometimes use for “conventional wisdom,” e.g. prediction markets, don’t always track with what reporters and pundits think.

nrakich: Yeah, that’s an interesting question. If someone asked me, “Are Trump’s re-election chances overrated or underrated?” I wouldn’t know what to say — but mostly because I don’t know where they’re rated!

I think you’d find wide disagreement.

perry: It sounds as if we’d give Trump between a 47 and 53 percent chance of winning. How many political journalists do you think would disagree with that?

I’m guessing a fairly low number.

And how many voters would disagree? Again, I’d think a low number.

nrakich: I don’t know, I feel like most people on Twitter (disclaimer: Twitter is not real life) either assume he is a clear underdog or that he’s the favorite.

But it’s OK to just say we don’t know!

natesilver: There’s a difference between saying “We don’t know” and “The odds are about 50-50.”

Like, by default, incumbent presidents get re-elected, say, 70 percent of the time (it’s actually a bit complicated how to calculate this percentage and how far you go back in history and who counts as an incumbent and all that, but let’s leave that aside for now), so to say the chances are only 50-50 is actually saying something.

geoffrey.skelley: But if you look at incumbents historically, I think you could safely say Trump is one of the most endangered.

natesilver: That seems fair. Incumbents usually get re-elected, but Trump is a weaker-than-average incumbent.

nrakich: Right. My thought process goes something like this: Under normal conditions, the president would be a clear favorite. Good economy, elected incumbent. But then you clearly have to apply some kind of penalty since these aren’t normal conditions — Trump is pretty unpopular and lacks the discipline to expand his appeal.

But then how big is the penalty? I have no idea, and I don’t know how to calculate it objectively. So I just say, “I don’t know.”

sarahf: Well, some of what we’re seeing here about people underestimating Trump’s odds stems from what I think is also a strawman argument — Democrats will muck up their chances by nominating a candidate who is too far to the left.

natesilver: The evidence that nominating a far-left/far-right candidate hurts you is actually pretty robust. I don’t think that argument is a strawman.

Voters in 2016 thought Trump was closer to the center of the electorate than Clinton, by the way. He’s actually a data point in favor of that thesis.

geoffrey.skelley: Presumably, Trump will be perceived as more conservative in 2020, though?

natesilver: Yeah, voters will perceive him as more conservative now than they did in 2016, so that’s an opportunity for whoever the Democratic candidate is.

But Trump, obviously, will be scrambling to define that Democrat as left-wing.

geoffrey.skelley: Socialist this, socialist that. It might work.

sarahf: Fair, Nate. I just think we’re a ways from knowing who the 2020 Democratic nominee will be, and while they might be more to the left than, say, a Democratic candidate running in 2008, I’m not sure how “left-wing” they’ll actually be.

natesilver: Some mitigating factors: Some left-wing policy positions (e.g. the $15 minimum wage) are actually quite popular, and Democrats have a slightly larger base than Republicans do (contra the conventional wisdom) so a base-turnout strategy is actually more likely to work for a Democrat than a Republican (e.g. it worked for Obama in 2012).

The socialist label is potentially damaging, however.

perry: I will say, too much coverage in 2016 — and now — assumes there isn’t a set of voters who don’t really like what they are getting from Trump, but who really hate the Democrats. Trump’s approval rating is at 40 percent, but in some head-to-head polls he is in the high 40s — 47 to 49. That 8-point (or so) difference, I think, is people who are anti-Democratic and will be remain anti-Democratic no matter who the candidate is.

geoffrey.skelley: That gets at negative partisanship. It’ll help Trump up to a certain point — unless the bottom drops out (the economy tanks or the Mueller report is really damning or something else).

natesilver: Ehhhh, I don’t know that I’d put too much stock in the head-to-head polls against candidates that aren’t well defined.

My question is more: Could Trump get up to 43 or 44 percent approval? (Sure.) And could the Democratic nominee also be at like 43 or 44 percent favorability by November 2020? (Of course.) And then it comes down to the Electoral College. (Probably good for Trump.)

That’s sort of the path of least resistance to a second term for Trump. It’s not really all that difficult.

nrakich: Sure, but I think most people would agree that Trump has a path to re-election. The question is, are there more paths to him winning than him losing?

It kinda sounds like we’re saying there are more paths to him losing than winning.

perry: I just think people who voted for Trump once kind of knew what they were getting, and the ones that were driven mainly by hating the Democrats so much would probably vote for him again.

natesilver: I’m … not totally sure about that? I think a lot of people thought, “Why the hell not?” and took a chance on Trump. I think some of those people regret that choice.

I also think some people who voted against Trump will look at the economy and say, “That didn’t turn out so bad after all.” And vote for him. (If the economy remains good.)

geoffrey.skelley: And then we’re back at 48 percent to 46 percent with Howard Schultz getting much of the remainder, right?

natesilver: I was so happy that we got this far without mentioning Howard Schultz.

geoffrey.skelley: Apologies.

sarahf: But why do we think things would be so much worse for Trump if the economy tanks? Is it because voters who say they’re independent would defect en masse?

nrakich: All you have to do is break down his approval ratings a bit. In a YouGov poll this week, 25 percent of Americans said they strongly approve of his performance, and 16 percent said they somewhat approve. If the economy falters, a big part of Trump’s messaging for why he’s a good president will be gone, and those skeptical Trump approvers will no longer be Trump approvers.

geoffrey.skelley: And they’ll probably be independents and people who lean toward voting Republican.

natesilver: Trump’s position is precarious enough that even if that “the economy is the key to re-election” thesis is a little overrated — and I think it might be — any deterioration in his position based on the economy makes it very hard for him.

geoffrey.skelley: Exactly. In a recent CNN survey, his net approval was -9, but seven out of 10 Americans felt the economy was in good shape.

On Earth 3, where Marco Rubio is president (as opposed to Earth 2, where Clinton won), I have a hard time imagining his approval rating is that bad with the economy doing relatively well.

nrakich: The economy is the only reason Trump’s approval rating isn’t truly terrible.

Something — presumably his personality — is keeping his approval rating depressed relative to where a generic president would be.

natesilver: I really do think there’s a segment of people who don’t like the tweeting, think Trump is dishonest, sorta do care about the Mueller probe, maybe even think he’s a little racist, but also think all of that stuff is a little overhyped if, at the end of the day, the economy is good and the country isn’t fighting in any really destructive wars.

sarahf: OK, I think we all agree: Trump has a path to re-election. But it also seems as if we agree that Democrats are taking his re-election chances very seriously. So where does that leave us? What will you be looking at to better understand Trump’s re-election odds?

natesilver: To be honest, I’m not sure if we’ll learn anything that meaningful about Trump’s re-election odds for the next six months.

I guess we’ll learn the status of the Mueller report.

But it’s a bit too early to know what the economy will look like in 2020, and it will still be kinda early six months from now.

We also won’t know who the Democratic nominee will be.

nrakich: I’m looking at (a) the economy, (b) whether the Mueller report budges his approval rating (using that as a measure of whether it’s already baked in or if people can still be persuaded by Trump’s scandals), and (c) whether he shows any signs of changing his behavior to reflect the fact that it’s about to be an election year.

And I guess (d) who the Democratic nominee will be. But that’s still a year or more away.

geoffrey.skelley: Agreed on all points. Too many moving parts at this point in the “fundamentals” department, but people shouldn’t use them as an excuse to think Trump is doomed or sure to win.

perry: My assumption is that Trump’s approval will go up between now and Election Day, maybe up close to 45 percent (since there are lots of people who, in my view, are saying that they disapprove of Trump, but who will never vote for a Democrat, so they will gradually start say they approve of Trump, since they are going to vote for him.

But I don’t know if that uptick in Trump’s approval number will happen in the next six months or not.

I guess my view is that 96 percent or so of general-election voters have already decided if they are with Trump or not.

nrakich: I think that’s going a little far. There’s still the potential for a wave one way or another. Or even if people’s minds won’t change, whether they’re excited enough to turn out to vote could.

#EmbraceTheUncertainty

March 18, 2019

Politics Podcast: Which 2020 Candidates Have Had The Best Rollouts So Far?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The Democratic primary field is taking shape. In this episode of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew debates which candidates have done the best job of introducing themselves to voters in the early days of the contest. The team also takes stock of Republican defections from President Trump — on the recent national emergency declaration vote and other issues.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Is Beto O’Rourke Learning How To Troll The Media?

At 5:03 a.m. on Monday, Politico published a story on former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke’s “rocky rollout” to his presidential campaign, which launched last week.1

Roughly two hours later, O’Rourke’s campaign announced that it had raised $6.1 million in the first 24 hours after launch — more than any other Democratic candidate including Sen. Bernie Sanders, who raised $5.9 million.

Presumably, this was intentional on the O’Rourke campaign’s behalf. Having some good news in its pocket, it waited to announce its fundraising haul until a busier news cycle (Monday morning instead of Friday afternoon) and until the media narrative surrounding his launch had begun to overextend itself. O’Rourke’s $6.1 million in fundraising is important unto itself — more money allows a campaign to hire more staff, open more field offices, run more ads and compete in more states — but it sounded like an even bigger deal to journalists who had begun to hear whispers of fundraising totals that would fall well below that.

Indeed, I too had thought it was probably a bad sign for O’Rourke that he had not disclosed his fundraising on Friday when the 24-hour period ended, although I said that it would be a “good troll” if he had intentionally held off on announcing just to screw with media expectations:

It would be a good troll if the numbers were actually good and he delayed releasing them just to sort of draw the media offsides and fuck with their expectations, but I'm not really sure if his campaign has that gear.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) March 15, 2019

It could be more than a good troll, in fact, if it suggests that O’Rourke and his staff are learning to manage media expectations, something that had been a problem for the proto-campaign in its pre-launch phase. Expectations management is a key survival skill for a modern presidential candidate — one that could come in handy later on when the media is trying to interpret, for example, whether a second-place finish in the Iowa caucuses was a good finish for O’Rourke or a bad one.

For better or worse, the primaries are partly an expectations game, meaning that it’s not just how well you do in an absolute sense that matters, but how well you do relative to how well the media expects you to do. Historically, for instance, the candidates that receive the biggest bounce to their national and New Hampshire polls after the Iowa caucuses are those who most beat their polls in Iowa — and therefore most beat media expectations, which are usually closely tied to the polls — and not necessarily the actual winners. The canonical example of this dynamic is Sen. Gary Hart and former Vice President Walter Mondale in the 1984 Democratic caucuses in Iowa. Even though Mondale dominated the caucuses with 48.9 percent of the vote to Hart’s 16.5 percent, it was Hart who got the favorable headlines as the media had finally found an alternative to the boring, predictable Mondale “juggernaut.” The next week, Hart came from well behind in the polls to win the New Hampshire primary.

The expectations game is dumb — among other things, it gives the media too large a role in the primary process — and maybe both voters and the media have become more sophisticated to the point where it matters less than it once did. (Recent Iowa caucuses have not produced especially large bounces, for instance.) I wouldn’t be so sure about that, though. Keeping expectations in check was a big problem in the Democratic primaries in 2016 for Hillary Clinton, who had one of the more robust victories of the modern primary era but who didn’t (and still doesn’t) get a lot of credit for it.

Conversely, one of President Trump’s big strengths in the primaries was to completely dominate media coverage — a big advantage when you need to differentiate yourself in a field of 17 candidates — while keeping expectations low. Usually, more coverage and higher expectations go hand-in-hand; the more hype you get, the more the press expects you to perform well in debates, polls, fundraising and, ultimately, in primaries and caucus. But Trump had a knack for trolling the media and for hacking the news cycle to make sure that he remained the center of the conversation. It’s not that this necessarily required great skill on Trump’s behalf, but he was canny enough to know that the media’s behavior is fairly predictable and therefore easy to manipulate. Meanwhile, lots of folks in the media — and certainly us here at FiveThirtyEight — were way too willing to dismiss polls showing Trump well ahead of the Republican field from the summer of 2015 onward. A high volume of coverage but low expectations is the best of both worlds for a candidate in the primaries, and Trump got it.

O’Rourke is going to get a lot of media coverage — and he’s one of those candidates who, like past failed candidates such as then-Gov. Rick Perry in 2012 and Sen. Marco Rubio in 2016, but also like successful ones such as then-Sen. Barack Obama in 2008 and Trump in 2016 — simultaneously seems to be overrated and underrated by the press and never quite at equilibrium. I’ve learned the hard way that it’s particularly important to stay at arm’s length when evaluating candidates like these, to wait for polling data or fundraising data or other hard evidence on how well they’re doing, and to avoid reading too much into the media narratives surrounding them because they’re prone to shift on a whim. O’Rourke’s fundraising numbers — as the most tangible sign to date of how his campaign is performing — were a fairly big deal, but so was his campaign’s apparent awareness about the importance of managing expectations.

March 17, 2019

2019 March Madness Predictions

FiveThirtyEight

2019 March Madness Predictions

In-game win probabilities and chances of advancing, updating live.

How Our March Madness Predictions Work

Brian Burke’s Excitement Index / DonBest injury report / ESPN’s BPI / Sports-Reference.com

Jeff Sagarin’s ratings / Joel Sokol’s LRMC ratings / Ken Massey’s ratings / Ken Pomeroy’s ratings / Sonny Moore’s ratings (men, women)

The Details

We’ve been issuing probabilistic March Madness forecasts in some form since 2011, when FiveThirtyEight was just a couple of people writing for The New York Times. Initially, we focused on the men’s NCAA Tournament, publishing a table that gave each team’s probability of advancing deep (or not-so-deep) into the tournament. Over the years, we expanded to forecasting the women’s tournament as well. And since 2016, our forecasts have updated live, as games are played. Below are the details on each step that we take — including calculating power ratings for teams, win probabilities for each game and the chance that each remaining team will make it to any given stage of the bracket.

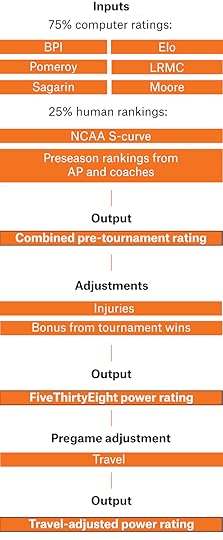

Men’s team ratings

Our men’s model is principally based on a composite of six computer power ratings:

Ken Pomeroy’s ratings

Jeff Sagarin’s “predictor” ratings

Sonny Moore’s ratings

Joel Sokol’s LRMC ratings

ESPN’s Basketball Power Index

FiveThirtyEight’s Elo ratings (described below)

Each of these ratings has a strong track record in picking tournament games. We shouldn’t make too much of the differences among them: They are all based on the same basic information — wins and losses, strength of schedule, margin of victory — computed in slightly different ways. We use six systems instead of one, however, because each system has different features and bugs, and blending them helps to smooth out any rough edges. (Those rough edges matter because even small differences can compound over the course of a single-elimination tournament that requires six or seven games to win.)

To produce a pre-tournament rating for each team, we combine those computer ratings with a couple of human rankings:

The NCAA selection committee’s 68-team “S-curve”

Preseason rankings from The Associated Press and the coaches

These rankings have some predictive power — if used in moderation. They make up one-fourth of the rating for each team; the computer systems are three-fourths.

It’s not a typo, by the way, to say that we look at preseason rankings. The reason is that a 30- to 35-game regular season isn’t all that large a sample. Preseason rankings provide some estimate of each team’s underlying player and coaching talent. It’s a subjective estimate, but it nevertheless adds some value, based on our research. If a team wasn’t ranked in either the AP or coaches’ polls, we estimate its strength using the previous season’s final Sagarin rating, reverted to the mean.

To arrive at our FiveThirtyEight power ratings, which are a measure of teams’ current strength on a neutral court and are displayed on our March Madness predictions interactive graphic, we make two adjustments to our pre-tournament ratings.

The first is for injuries and player suspensions. We review injury reports and deduct points from teams that have key players out of the lineup. This process might sound arbitrary, but it isn’t: The adjustment is based on Sports-Reference.com’s win shares, which estimate the contribution of each player to his team’s record while also adjusting for a team’s strength of schedule. So our program won’t assume a player was a monster just because he was scoring 20 points a game against the likes of Abilene Christian and Austin Peay. The injury adjustment also works in reverse: We review every team to see which are healthier going into the tournament than they were during the regular season.

The second adjustment takes place only once the tournament is underway. The FiveThirtyEight model gives a bonus to teams’ ratings as they win games, based on the score of each game and the quality of the opponent. A No. 12 seed that waltzes through its play-in game and then crushes a No. 5 seed may be much more dangerous than it initially appeared; our model accounts for this. On the flip side, a highly rated team that wins but looks wobbly against a lower seed often struggles in the next round, we’ve found.

When we forecast individual games, we apply a third and final adjustment to our ratings, for travel distance. Are you not at your best when you fly in from LAX to take an 8 a.m. meeting in Boston? The same is true of college basketball players. In extreme cases (a team playing very near its campus or traveling across the country to play a game), the effect of travel can be tantamount to playing a home or road game, despite being on an ostensibly neutral court. This final adjustment gives us a team’s travel-adjusted power rating, which is then used to calculate its chance of winning that game.

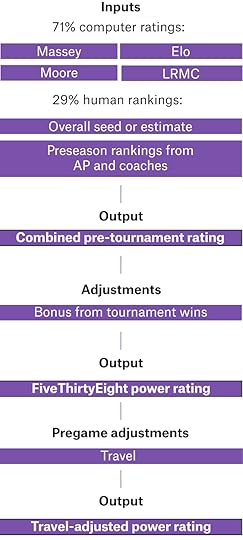

Women’s team ratings

We calculate power ratings for the women’s tournament in much the same way as we do for the men’s. However, because of the relative lack of data for women’s college basketball — a persistent problem when it comes to women’s sports — the process has a few differences:

Four of the six power ratings that we use for the men’s tournament aren’t available for women. But fortunately, two of them are: Sokol’s LRMC ratings and Moore’s ratings. We also use a third public system, the Massey Ratings, as well as

a version of FiveThirtyEight’s Elo ratings that we’ve built for NCAA women’s basketball.

Model tweak

March 17, 2019

The NCAA doesn’t publish 68-team S-curve data for the women. So we use the teams’ seeds instead, with the exception of the four No. 1 seeds, which the selection committee does list in order.

For the women’s tournament, there isn’t much in the way of injury reports or advanced individual statistics, so we don’t include injury adjustments.

Turning power ratings into a forecast

Once we have power ratings for every team, we need to turn them into a forecast — that is, the chance of every team reaching any round of the tournament.

Most of our sports forecasts rely on Monte Carlo simulations, but March Madness is different; because the structure of the tournament is a single-elimination bracket, we’re able to directly calculate the chance of teams advancing to a given round.

We calculate the chance of any team beating another with the following Elo-derived formula, which is based on the difference between the two teams’ travel-adjusted power ratings:

\(\Large \frac{1.0}{1.0+10^{-travel\_adjusted\_power\_rating\_diff*30.464/400}}\)

Because a team needs to win only a single game to advance, this formula gives us the chance of a team reaching the next round in the bracket. The probability of a team reaching a future round in the bracket is based on a system of conditional probabilities. In other words, the chance of a team reaching a given round is the chance it reaches the previous round, multiplied by its chance of beating any possible opponent in the previous round, weighted by its likelihood of meeting each of those opponents.

Live win probabilities

While games are being played, our interactive graphic displays a box for each one that shows updating win probabilities for both teams, as well as the score and the time remaining. These probabilities are derived using logistic regression analysis, which lets us plug the current state of a game into a model to produce the probability that either team will win the game. Specifically, we used play-by-play data from the past five seasons of Division I NCAA basketball to fit a model that incorporates:

Time remaining in the game

Score difference

Pregame win probabilities

Which team has possession, with a special adjustment if the team is shooting free throws

The model doesn’t account for everything, however. If a key player has fouled out of a game, for example, the model doesn’t know, and his or her team’s win probability is probably a bit lower than what we have listed. There are also a few places where the model experiences momentary uncertainty: In the handful of seconds between the moment when a player is fouled and the free throws that follow, for example, we use the team’s average free-throw percentage to adjust its win probability. Still, these probabilities ought to do a reasonably good job of showing which games are competitive and which are essentially over.

Also displayed in the box for each game is our “excitement index” (check out the lower-right corner) — that number also updates throughout a game and can give you a sense of when it’ll be most fun to tune in. Loosely based on Brian Burke’s NFL work, the index is a measure of how much each team’s chances of winning have changed over the course of the game.

The calculation behind this feature is the average change in win probability per basket scored, weighted by the amount of time remaining in the game. This means that a basket made late in the game has more influence on a game’s excitement index than a basket made near the start of the game. We give additional weight to changes in win probability in overtime.

We also add a bonus for games that spend a large proportion of their time with an upset on the horizon, weighted by how big the upset would be.

Model tweak

March 17, 2019

Values range from 0 to 10, although they can exceed 10 in extreme cases.

FiveThirtyEight’s Elo ratings

If you’ve been a FiveThirtyEight reader for really any length of time, you probably know that we’re big fans of Elo ratings. We’ve introduced versions for the NBA and the NFL, among other sports. Using game data from ESPN, Sports-Reference.com and other sources, we’ve also calculated Elo ratings for men’s college basketball teams dating back to the 1950s and for women’s teams since 2001. Our Elo ratings are one of the six computer rating systems used in the pre-tournament rating for each men’s team and one of four systems for each women’s team.

Our methodology for calculating these Elo ratings is very similar to the one we use for the NBA. Elo is a measure of a team’s strength that is based on game-by-game results. The information that Elo relies on to adjust a team’s rating after every game is relatively simple — including the final score and the location of the game. (As we noted earlier, college basketball teams perform significantly worse when they travel a long distance to play a game.)

It also takes into account whether the game was played in the NCAA Tournament. We’ve found that historically, there are actually fewer upsets in the tournament than you’d expect from the difference in teams’ Elo ratings, perhaps because the games are played under better and fairer conditions in the tournament than in the regular season. Our Elo ratings account for this and weight tournament games slightly higher than regular-season ones.

Because Elo is a running assessment of a team’s talent, at the beginning of each season, a team gets to keep its rating from the end of the previous one, except that we also revert it to the mean. The wrinkle here, compared with our NFL Elo ratings, is that we revert college basketball team ratings to the mean of the conference.

While we make no guarantee that you’ll win your pool if you use our system, we think it’s done a pretty job over the years. Hopefully, you’ll have fun using it to make your picks, and it will add to your enjoyment of both NCAA tournaments.

Editor’s note: This article is adapted from previous articles our March Madness predictions work.

Model Creator

Jay Boice A computational journalist for FiveThirtyEight. | @jayboice

Nate Silver Editor in chief. | @NateSilver538

Version History

1.4 Added women’s Elo model and started adjusting excitement index for upsets.March 17, 2019

1.3 Added live win probabilities and men’s Elo model.March 13, 2016

1.2 Added women’s forecast.March 17, 2015

1.1 Started accounting for strength of schedule when making injury adjustments; started using reverted Sagarin ratings as preseason ratings.March 15, 2015

1.0 Forecast launched for the 2014 tournament.March 17, 2014

Related Articles

2019 March Madness predictions

2018 March Madness predictions

2017 March Madness predictions

2016 March Madness predictions

2015 March Madness predictions

2014 men’s NCAA tournament predictions

March 14, 2019

Politics Podcast: Beto O’Rourke’s Path To The Democratic Nomination

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Former El Paso congressman Beto O’Rourke announced he is running for president on Thursday. In this episode of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew considers various arguments for why he could win — or lose — the Democratic nomination. He is entering an experienced field never having won statewide office, but his celebrity could allow him to gain traction in a campaign with 15-20 competitors.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 13, 2019

Joe Biden’s And Bernie Sanders’s Support Isn’t Just About Name Recognition

If you’re a longtime reader of FiveThirtyEight, you’ll know that the early stage of the presidential primary process is a tricky one for us to cover. It’s tempting to put a lot of emphasis on shiny objects with numbers attached — polls, endorsement counts, fundraising totals — especially given our reputation as a data-driven news site, but those numbers aren’t always so predictive. It’s perhaps equally tempting to lapse into punditry or theater criticism, on the theory that if the objective metrics aren’t especially reliable, you might as well go with your gut — but that can be equally if not more dangerous.

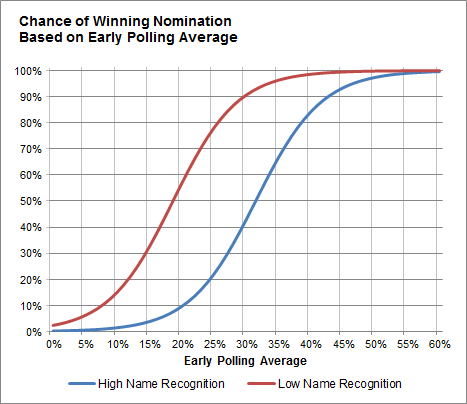

But on balance, I suspect that smart observers of the political process don’t give enough consideration to early polls, such as the CNN/Des Moines Register poll of Iowa caucus-goers (conducted by top-rated polling firm Selzer & Co.) that came out last weekend. As we documented in a three-part series back in 2011,1 the notion that early polling is meaningless or solely reflects name recognition — a popular view even among people we usually agree with — is wrong, full stop.

Other things held equal, for instance, a candidate polling at 25 percent in early polls is five or six times more likely to win the primary than one polling at 5 percent. It would be equally if not more wrong to say whoever leads in early polls is certain to win the nomination. (A candidate at 25 percent is still a sizable underdog relative to the field, for instance.) But I don’t hear anyone saying that. At least, I haven’t heard anyone saying it about the Democrats leading in the polls — Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders — so far this year.

It certainly is worthwhile to account for name recognition and to go beyond the topline numbers when looking at these polls, however. In particular, favorability ratings are useful indicators: Few voters have a firm first choice yet, so it’s helpful to know which candidates they’re considering, which ones they’ve ruled out, and which ones they don’t know enough about to have decided either way. When you look at those things, Biden’s numbers still look quite decent, even if he isn’t the sort of prohibitive front-runner that, say, Hillary Clinton was in 2016. Sanders’s numbers look a little weaker than Biden’s, but nonetheless pretty good. Both candidates have plenty of genuine support.

Let’s start with a simple exercise. In that 2011 series, I found that a decent heuristic for adjusting for name recognition is to divide the number of voters who have the candidate as their first choice by the number who recognize his or her name. For instance, a candidate with 20 percent first-choice support and 100 percent name recognition is roughly as likely to win the nomination as one with 10 percent first-choice support but just 50 percent name recognition.

When you do that with the Iowa poll, it … doesn’t really change much at all. The order of the candidates is exactly the same whether or not you account for name recognition, in fact. Candidates such as Kamala Harris and Beto O’Rourke do gain a little bit of ground relative to Biden and Sanders, but not much:

Accounting for name recognition doesn’t change much

Name recognition and first-choice support among 401 likely Democratic caucusgoers in Iowa, according to a March 3-6, 2019, Selzer & Co. poll

Candidate

First-choice support

Name recognition

Adjusted support*

Joe Biden

27%

96%

28%

Bernie Sanders

25

96

26

Elizabeth Warren

9

83

11

Kamala Harris

7

67

10

Beto O’Rourke

5

64

8

Amy Klobuchar

3

58

5

Cory Booker

3

66

5

Michael Bennet

1

25

4

Steve Bullock

1

26

4

Jay Inslee

1

26

4

Pete Buttigieg

1

28

4

Julian Castro

1

37

3

John Delaney

1

40

3

* First-choice support percentage divided by percentage of respondents who had heard of the candidate.

Candidates who got 0 percent support in the poll are not listed.

Source: Des Moines Register/CNN/Mediacom Iowa Poll

Look at favorability ratings instead, and the story gets a bit more complicated. The Selzer & Co. poll asked voters to rate each candidate on a scale from “very favorable” to “very unfavorable”; voters were also allowed to say they didn’t know enough about the candidate to rate them. We can translate the candidate ratings into a favorability score from 0 (very unfavorable) to 100 (very favorable) by calculating the average rating, throwing out voters who didn’t know or didn’t rate the candidate. To get a sense for which candidates are wearing well with the electorate, we can also compare favorability scores and name recognition against the previous version of the Iowa poll in December.

Biden and Harris have the best favorability ratings in Iowa

Favorability ratings and name recognition in the December and March Selzer & Co. Iowa polls

Name recognition

Favorability score*

Candidate

December

March

December

March

Biden

97%

96%

76.4

75.4

Harris

58

67

69.7

71.3

O’Rourke

64

64

73.5

68.4

Sanders

96

96

70.6

67.8

Warren

85

83

67.9

65.6

Booker

61

66

66.8

63.8

Castro

37

42

60.5

63.7

Brown

31

32

61.4

62.6

Klobuchar

46

58

70.4

62.2

Bennet

25

58.8

Swalwell

28

29

56.1

58.7

Inslee

18

26

55.6

57.8

Hickenlooper

33

36

60.7

56.6

Delaney

36

40

58.4

56

Gillibrand

44

50

62.3

55.5

Buttigieg

28

54.8

Gabbard

37

52.3

Bullock

19

21

50.9

47.6

de Blasio

50

43.3

Bloomberg

71

65

50.8

43.1

Yang

17

19

33.3

40.3

Schultz

58

24

* Favorability score = 100 points per “very favorable,” 67 points per “mostly favorable,” 33 points per “mostly unfavorable” and 0 points per “very unfavorable,” ignoring don’t knows and no opinions.

Source: Des Moines Register/CNN/Mediacom Iowa Polls

Biden has easily the best favorability score in the March Iowa poll, at 75.4. Remember, we’re not counting voters who didn’t rate the candidate, so he’s not advantaged by his high name recognition. The second-best favorability score belongs to Harris, however, at 71.3, and both her favorability score and her name recognition are improved from December — more evidence she’s had a strong rollout period. The third-best favorability score belongs to O’Rourke — although his numbers are down from December — with Sanders in fourth.

It’s true that this is just one poll — and not one with a huge sample size (401 Democrats) — but it generally squares with other polls that also measure favorability. If you look at the ratio of favorable to unfavorable ratings in those polls, Biden generally rates first, and then Harris, Sanders and O’Rourke appear in some order behind him, occasionally also joined by Cory Booker.

So it probably helps to distinguish the cases of Biden and Sanders. Biden leads the field by every polling-based metric: first-choice support, whether adjusted for name recognition or not, as well as in favorability ratings. He may not survive scrutiny if and when he officially declares for the race — he wasn’t a very good candidate when he ran for president in 1988 and 2008 — but he starts out with deep loyalty from a fairly broad spectrum of the Democratic base.

Sanders, conversely, has a high floor of support and a lot of enthusiasm behind him, but that’s tempered by having some Democrats — 25 percent in the Iowa poll — who have an unfavorable view of him. If that number holds at 25 percent — and the other 75 percent of Democrats would consider voting for Sanders — he shouldn’t have a lot of problems. Still, 25 percent is high, compared with the scores for candidates such as Biden, Booker and Harris, and Sanders will face a new type of scrutiny for him as one of the front-runners who is taking fire from all sides, instead of being in a two-candidate race as the underdog against Clinton.

It will also be important to track whether Sanders can hold onto or further improve upon the bounce in first-choice support that he’s received since officially entering the race last month. Before then, Sanders was generally polling in the high teens or low 20s, but he’s since bounced into the mid-to-high 20s in first-choice support.

That happens to be near an inflection point where a candidate goes from a weak front-runner to a more formidable one. As you can see from our 2011 analysis — with a chart that is decidedly not up to current FiveThirtyEight design standards — candidates who are only polling at 20 percent despite high name recognition in the early stage of the race are often paper tigers. But get up to 30 percent, and your chances of winning the nomination improve quite a bit. That’s the point at which you may be able to win causes and primaries with a plurality; Trump won lots of states in the early going in 2016 with a vote share in the low-to-mid 30s, for example.

Biden is also fairly close to this inflection point. In general, he’s been on the happy side of it, with first-choice support in the high 20s or low 30s. But it’s possible to imagine him either gaining support (as he generates more excitement) or losing support (as he gets more scrutiny) if and when he declares for the race. There’s also a relative lack of comparatively moderate candidates in the field so far; if O’Rourke has a strong debut, it could come at Biden’s expense, for instance.

To be clear, I don’t think you should be going solely or necessarily even mostly by the polls at this stage of the primary. There are lots of other quantitative and qualitative ways to evaluate the candidates; we think a multifaceted approach is best. There’s still a lot to be said for tracking measures of insider support such as endorsements, for instance, which despite having been a useless indicator in the 2016 Republican primary still have a strong track record overall. Those insider metrics are middling for both Sanders and Biden. In Sanders’s case, he’s off to a much better start in endorsements than four years ago, but is nonetheless behind Harris, Booker and Amy Klobuchar. It’s harder to evaluate Biden because he hasn’t entered the race yet; he does have some endorsements, but the sheer number of candidates running suggests that he doesn’t have the field-clearing power that Clinton did in 2016.

But at the very least, the polls aren’t reason to be dismissive of Sanders and Biden. If you think of a mental scale that spans the categories “bad,” “meh,” “pretty good,” “good” and “great,” Biden’s polling qualifies as good2 even if you do count for name recognition, and Sanders’s as pretty good (inching toward good in the most recent polls). Harris also belongs in the pretty good category on the basis of her strong favorability ratings, even though she doesn’t have as much first-choice support. Otherwise, the candidates’ polling is pretty underwhelming — O’Rourke is probably on the border of meh and pretty good, but the rest of the candidates are solidly into meh territory, or worse. Biden’s and Sanders’s positions aren’t spectacular, but most candidates would gladly give up their own path to the nomination for one of theirs.

CORRECTION (March 13, 2019, 2:45 p.m.): An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that 22 percent of Iowa Democrats had an unfavorable view of Bernie Sanders, according to a March Selzer poll. His unfavorable rating in that poll was 25 percent. It was 22 percent in a December version of the poll.

March 11, 2019

Politics Podcast: How Divided Are Democrats?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Democrats have been out of the wilderness and in control of the House of Representatives for a little over two months, and with that newfound power has come a greater focus on the divisions within the party. In this episode of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew looks at where the party’s fault lines are, and what those divisions could mean for the party going forward. The gang also dives into why some potential candidates, like Sen. Sherrod Brown of Ohio, decided not to run in 2020.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers