Nate Silver's Blog, page 69

April 4, 2019

When We Say 70 Percent, It Really Means 70 Percent

One of FiveThirtyEight’s goals has always been to get people to think more carefully about probability. When we’re forecasting an upcoming election or sporting event, we’ll go to great lengths to analyze and explain the sources of real-world uncertainty and the extent to which events — say, a Senate race in Texas and another one in Florida — are correlated with one another. We’ll spend a lot of time working on how to build robust models that don’t suffer from p-hacking or overfitting and which will perform roughly as well when we’re making new predictions as when we’re backtesting them. There’s a lot of science in this, as well as a lot of art. We really care about the difference between a 60 percent chance and a 70 percent chance.

That’s not always how we’re judged, though. Both our fans and our critics sometimes look at our probabilistic forecasts as binary predictions. Not only might they not care about the difference between a 60 percent chance and a 70 percent chance, they sometimes treat a 55 percent chance the same way as a 95 percent one.

There are also frustrating moments related to the sheer number of forecasts that we put out — for instance, forecasts of hundreds of U.S. House races, or dozens of presidential primaries, or the thousands of NBA games in a typical season. If you want to make us look bad, you’ll have a lot of opportunities to do so because some — many, actually — of these forecasts will inevitably be “wrong.”

Sometimes, there are more sophisticated-seeming criticisms. “Sure, your forecasts are probabilistic,” people who think they’re very clever will say. “But all that means is that you can never be wrong. Even a 1 percent chance happens sometimes, after all. So what’s the point of it all?”

I don’t want to make it sound like we’ve had a rough go of things overall.1 But we do think it’s important that our forecasts are successful on their own terms — that is, in the way that we have always said they should be judged. That’s what our latest project — “How Good Are FiveThirtyEight Forecasts?” — is all about.

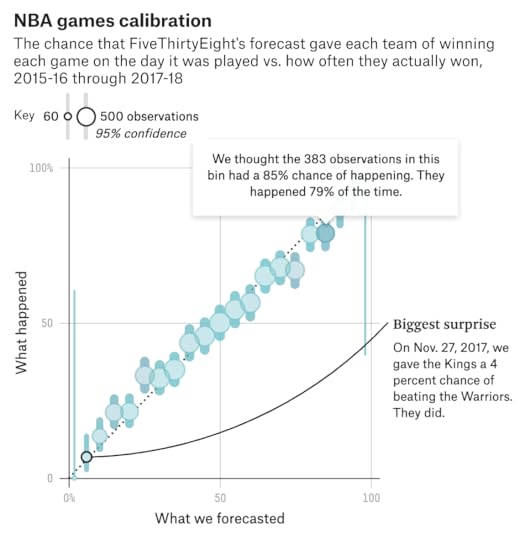

That way is principally via calibration. Calibration measures whether, over the long run, events occur about as often as you say they’re going to occur. For instance, of all the events that you forecast as having an 80 percent chance of happening, they should indeed occur about 80 out of 100 times; that’s good calibration. If these events happen only 60 out of 100 times, you have problems — your forecasts aren’t well-calibrated and are overconfident. But it’s just as bad if they occur 98 out of 100 times, in which case your forecasts are underconfident.

Calibration isn’t the only thing that matters when judging a forecast. Skilled forecasting also requires discrimination — that is, distinguishing relatively more likely events from relatively less likely ones. (If at the start of the 68-team NCAA men’s basketball tournament, you assigned each team a 1 in 68 chance of winning, your forecast would be well-calibrated, but it wouldn’t be a skillful forecast.) Personally, I also think it’s important how a forecast lines up relative to reasonable alternatives, e.g., how it compares with other models or the market price or the “conventional wisdom.” If you say there’s a 29 percent chance of event X occurring when everyone else says 10 percent or 2 percent or simply never really entertains X as a possibility, your forecast should probably get credit rather than blame if the event actually happens. But let’s leave that aside for now. (I’m not bitter or anything. OK, maybe I am.)

The catch about calibration is that it takes a fairly large sample size to measure it properly. If you have just 10 events that you say have an 80 percent chance of happening, you could pretty easily have them occur five out of 10 times or 10 out of 10 times as the result of chance alone. Once you get up to dozens or hundreds or thousands of events, these anomalies become much less likely.

But the thing is, FiveThirtyEight has made thousands of forecasts. We’ve been issuing forecasts of elections and sporting events for a long time — for more than 11 years, since the first version of the site was launched in March 2008. The interactive lists almost all of the probabilistic sports and election forecasts that we’ve designed and published since then. You can see how all our U.S. House forecasts have done, for example, or our men’s and women’s March Madness predictions. There are NFL games and of course presidential elections. There are a few important notes about the scope of what’s included in the footnotes,2 and for years before FiveThirtyEight was acquired by ESPN/Disney/ABC News (in 2013) — when our record-keeping wasn’t as good — we’ve sometimes had to rely on archived versions of the site if we couldn’t otherwise verify exactly what forecast was published at what time.

What you’ll find, though, is that our calibration has generally been very, very good. For instance, out of the 5,589 events (between sports and politics combined) that we said had a 70 chance of happening (rounded to the nearest 5 percent), they in fact occurred 71 percent of the time. Or of the 55,853 events3 that we said had about a 5 percent chance of occurring, they happened 4 percent of the time.

We did discover a handful of cases where we weren’t entirely satisfied with a model’s performance. For instance, our NBA game forecasts have historically been a bit overconfident in lopsided matchups — e.g., teams that were supposed to win 85 percent of the time in fact won only 79 percent of the time. These aren’t huge discrepancies, but given a large enough sample, some of them are on the threshold of being statistically significant. In the particular case of the NBA, we substantially redesigned our model before this season, so we’ll see how the new version does.4

Our forecasts of elections have actually been a little bit underconfident, historically. For instance, candidates who we said were supposed to win 75 percent of the time have won 83 percent of the time. These differences are generally not statistically significant, given that election outcomes are highly correlated and that we issue dozens of forecasts (one every day, and sometimes using several different versions of a model) for any given race. But we do think underconfidence can be a problem if replicated over a large enough sample, so it’s something we’ll keep an eye out for.

It’s just not true, though, that there have been an especially large number of upsets in politics relative to polls or forecasts (or at least not relative to FiveThirtyEight’s forecasts). In fact, there have been fewer upsets than our forecasts expected.

There’s a lot more to explore in the interactive, including Brier skill scores for each of our forecasts, which do account for discrimination as well as calibration. We’ll continue to update the interactive as elections or sporting events are completed.

None of this ought to mean that FiveThirtyEight or our forecasts — which are a relatively small part of what we do — are immune from criticism or that our models can’t be improved. We’re studying ways to improve all the time.

But we’ve been publishing forecasts for more than a decade now, and although we’ve sometimes tried to do an after-action report following a big election or sporting event, this is the first time we’ve studied all of our forecast models in a comprehensive way. So we were relieved to discover that our forecasts really do what they’re supposed to do. When we say something has a 70 percent chance of occurring, it doesn’t mean that it will always happen, and it isn’t supposed to. But empirically, 70 percent in a FiveThirtyEight forecast really does mean about 70 percent, 30 percent really does mean about 30 percent, 5 percent really does mean about 5 percent, and so forth. Our forecasts haven’t always been right, but they’ve been right just about as often as they’re supposed to be right.

April 3, 2019

Is There Still Room In The Democratic Primary For Biden?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Former vice president Joe Biden has consistently led in early primary polls, and in head-to-head polls against President Trump, but he still hasn’t entered the 2020 Democratic presidential primary (although he’s expected to declare in April).

But who wants Biden to run? He doesn’t seem to be regarded as a front runner by party activists or those already in the field, and now two women have alleged that Biden touched them inappropriately, resurfacing his history of being physical in his interactions with women. [Editor’s note: After this chat concluded, The New York Times published a report about two more women who described physical interactions with Biden that made them uncomfortable]

Is it possible that the stakes of running in the Democratic Party have shifted so much that Biden now poses too much of a liability?

meredithconroy (Meredith Conroy, political science professor at California State University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): It’s too early to say whether these sorts of stories about Biden, which have been circulating for years, are enough to sink his chances. But as FiveThirtyEight’s Clare Malone said on the politics podcast, the way Lucy Flores has told her story recasts the incident as a more serious allegation, and less as late night talk show fodder.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): A candidate who leads in the polls and has some major figures in the party clamoring for him to run is in a pretty good position to weather this kind of controversy, I think. Prominent female Democrats, like Nancy Pelosi, are even saying what has emerged over the last week is not disqualifying.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): I don’t quite know what to think. If you follow the reaction on Twitter, a lot of people think the accusations are a big deal for Biden. But, a lot of those people didn’t have Biden as one of their top choices to begin with.

The biggest outstanding question I have for Biden is — where are the “party elites” clamoring for him to run. He has three endorsements — granted, you might not expect him to have many since he isn’t running yet — but two of those are senators from Delaware (his home state) and one is California Sen. Diane Feinstein, who is not a bad endorsee but also not the voice of a new generation of Democrats, exactly.

sarahf: It seems as if we’re seeing a generational divide play out here. I thought this Politico headline captured it well: “’Friendly grandpa’ or creepy uncle? Generations split over Biden behavior.”

perry: I definitely think you are seeing people who were inclined to support a more moderate figure and people who are older defending him. Polls show Biden doing really well with older Democrats (age 50 and older) and not as well with young voters. People who are younger and more liberal seem more inclined to attack Biden, but I suspect they weren’t that excited to see him run in the first place.

meredithconroy: I was having this conversation with some friends (I’m fun at parties) about whether Biden tests the “Party Decides” thesis if he doesn’t get elite support, but still wins the nomination.

My thought is that he doesn’t necessarily need institutional support to win. He has enough name recognition and goodwill (even now) to run and win without endorsements. I’m also in the camp that in today’s social media environment, the process is candidate-centered and not party-centered, and therefore the “Party Decides” idea is moot, but that’s a conversation for another day.

natesilver: I don’t know, I think what former President Obama does, in particular, is important. A lot of Biden’s popularity among rank-and-file Democrats stems from his association with Obama. If Obama endorses, say, Kamala Harris instead, that would be a pretty huge deal. And I tend not to think that Obama would do that, at least not in the early stages, but the lack of support for Biden is something that voters might notice. Maybe.

My question is not so much whether Biden can find a constituency within the Democratic Party, but whether he can be a unifying figure. And that seems harder now. Maybe the Flores accusations are partly a proxy for larger, generational issues, which is not to say they aren’t serious unto themselves. Still, this is a part of the party deciding, if you will. And the fact that Biden doesn’t seem to be able to control the narrative is a negative for him.

perry: So they seem like two different issues. One, is this disqualifying for Biden as a candidate?

The second question is how this changes the nature of his campaign if he enters. I assume this guarantees that his first week or so as a candidate will be dominated by questions about how he treats women. And the overall campaign environment will be hard. Biden will have to be more disciplined –and he is not known for that.

natesilver: Just thinking out loud here: There’s also the case to be made that things get better for Biden if he runs. If you’re sitting on the sidelines, just one narrative can dominate the conversation about you, e.g. Elizabeth Warren and the DNA test. But once you start running, you generate other sorts of news and create more context.

meredithconroy: Right, once he is in, he’s able to fill in this vacuum. But the Democratic Party is increasingly the party of women’s rights and equality, so I do think his pitch is going to be harder to sell.

sarahf: Granted, this story is from January, but even then, there was a perception that no major candidate was waiting on Biden to decide before they decided to run themselves. Do we think that’s accurate? Or do we really think Terry McAuliffe and maybe Michael Bloomberg are sitting in the wings, still waiting?

natesilver: I’m sort of torn. Because it can both be true that Biden is much weaker than his clear No. 1 status in the polls would imply, and that he’s a little bit more formidable than sort of young-ish NYC/DC journalists might assume, and they’re the ones that drive a lot of the conversation.

perry: If you lead in every poll, isn’t that a sign people want you to run? And just in talking to older black voters, they tell me they do want Biden to run, because they feel like he is the person most likely to beat Trump. And they are really fearful of a second term for Trump. This is anecdotal, but it’s not irrelevant.

natesilver: He maybe has that electability argument going for him. The thing is that some of the other Democrats — notably, Bernie — have seen their poll numbers against Trump decline once they decided to run. And while Biden’s numbers are strong now, they’d presumably be set to decline as well.

But I do think there’s a question here of: “Who will older voters be comfortable with?” Beto and Buttigieg will do plenty well with moderates (as well as liberals who don’t think of themselves as part of the left) under the age of 50. But that’s not really Biden’s constituency, and who competes with him for older Democrats?

In the abstract, if there were similar accusations against Sanders or Beto, that would be a bigger problem, because they’re relying more on young voters, and young voters are much more likely to consider that type of behavior to be inappropriate.

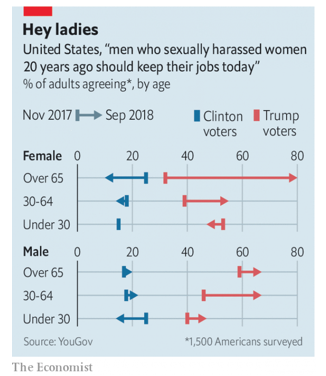

meredithconroy: I’m not so sure, Nate. A poll from the Economist late last year found that a sizable percentage of Democratic women over the age of 65 are less willing to tolerate sexual harassment from men. Biden could be in trouble with older women voters.

perry: But Biden is somewhat unique in that he appeals to both moderates and older people, and not just older-white-guy moderates. He is not ex-Gov. John Hickenlooper of Colorado (who is already in the race) or former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg or Sen. Michael Bennet of Colorado (both of whom are thinking about running). Those three are likely to find few voters outside of older, moderate white male Democratic voters. This means if Biden does not run, I think that’s not just good for Hickenlooper or other older white men. I think that’s good for almost everyone, particularly any candidate who’s looking to win the support of black voters, older voters and party loyalists.

sarahf: I think that’s right, Perry. That if Biden didn’t run, that’d be good for practically everyone. He really is the only candidate who fits the bill as a member of the establishment’s old guard. Which means if he didn’t run, there could be a pretty diverse coalition of support to split among the other candidates.

perry: But if Biden does run, I think that Bloomberg, former Gov. Terry McAuliffe of Virginia and Montana Gov. Steve Bullock in particular don’t have much of a path.

They probably didn’t have much of a path even if Biden didn’t run, but Biden does kind of take up the “electable man” lane, particularly with Mayor Pete, Beto and Booker also in that space.

Rep. Seth Moulton of Massachusetts and Rep. Tim Ryan of Ohio should be hoping Biden stays out.

Run, Joe, run! We need fewer candidates! Help us.

meredithconroy: Ha. Question: Is Biden more electable because he can win over aggrieved Republicans and moderates? That’s the story, right? That he is more broadly appealing than a liberal like Sanders or Warren.

natesilver: I do think there’s a fair amount of evidence that moderates over-perform candidates on the wings, other things held equal. So that part of Biden’s electability argument isn’t bad. He also has better favorables than any of the other Democrats for now, although that could very easily change.

sarahf: So say Biden runs … does that especially hurt Mayor Pete’s chances? Or Beto’s? Booker’s? Klobuchar’s? (Essentially, anyone who’s trying to run a platform that isn’t too far to the left.)

meredithconroy: Sarah, if you buy into the “white guy lane,” Biden definitely takes votes from the other white guys.

natesilver: I’m going to give a slightly counterintuitive view. I think the candidate who might be helped most by Biden not running — or hurt most if he does run — is Kamala Harris.

Biden’s popularity with black voters is a problem for her building a constituency.

I also wonder if some “party elites” might come off the sidelines for Harris if Biden were to decline to run.

perry: Harris is probably one of the most establishment-friendly candidates in the race, so big donors and people who backed Clinton in the 2016 primary would, I’m sure, prefer her over, say, Sanders. But don’t you think if Biden didn’t run, maybe there’s an argument that it would help Beto most?

natesilver: It’d help Beto, but there’s a pretty big generational divide between his support and Biden’s, I’d gather.

On the “party elites” side, I think it might push some older, moderate endorsers to back Beto.

But I think he might have to prove his case more to older voters.

perry: For the party-elite types who think a woman can’t win the general election (not a view I agree with but I hear it from a lot of rank and file voters), Biden not running is probably good for Beto.

But in terms of voters, Harris and Booker are probably helped a lot if Biden doesn’t run. They could get more of the non-Sanders vote and the black vote.

natesilver: I suppose it’s also possible that some ex-Obamaworld people are torn between Biden and Beto, so Biden not running could free up some staff talent and big donors, too.

perry: Are we sure it would not help Sanders?

natesilver: It could help Bernie, sure.

perry: Like if you are in second place and the person in first place removes himself from the race, that is good for you, right?

natesilver: Yeah, every other candidate’s chances go up. And Bernie is actually the second choice of a plurality of Biden voters. Although I do wonder if .

sarahf: Yeah, I’m curious how that changes as we get farther into the cycle.

natesilver: The dynamic I don’t like if I’m Bernie is if Biden doesn’t get in, which would probably help the party establishment settle on one (non-Bernie) candidate.

perry: After watching 2016 (when the GOP establishment failed to consolidate around an alternative to Trump), I’m more skeptical that will happen, but maybe Democrats are more disciplined than Republicans.

natesilver: I mean, you could certainly draw some parallels between Biden and Jeb Bush. Bush wasn’t off to a very good start, but he also froze party elite support, stopping it from going to other candidates. The flaw in that parallel is that Biden is polling at 30 percent instead of 10 percent or what have you.

meredithconroy: In 2016, I think the GOP party elite sat out because of a lack of good candidates. But in 2020 I think Democrats are sitting out because there are so many good candidates. So I think this year some party elites are frozen, waiting for Biden to decide.

natesilver: Part of me wonders whether Biden might go nuclear on Bernie, which could have a variety of effects. The Biden campaign is already (anonymously) blaming Sanders for the “handsy” stories, which seems a little weird because it seemed inevitable to me that those were going to become a topic of conversation anyway.

sarahf: But I guess as to the question of whether Biden could be a unifying force in the party — these allegations seem to undermine that idea. And point to the fact that he might be out of touch, or not the best representative of the direction the Democratic Party is moving. Do we think that’s a fair way to think about how these allegations impact Biden’s candidacy?

perry: If Trump’s approval had jumped to 48 percent after Attorney General William Barr issued a four-page letter on the Mueller report to Congress, this would be all different.

A lot of the force driving Biden’s potential candidacy is electability. And so if Trump looked really strong right now that would help Biden.

natesilver: That’s why I’m coming back to thinking Harris might be the long-term beneficiary of this. She probably has the best unify-the-party argument, at least among the people who are polling at more than 5 percent now. (Booker would be interesting, too, if his polling were livelier.)

perry: I’m not totally sure I think Biden’s situation as a candidate is that different than it was two weeks ago. Some parts of the party that already wanted him to go away are now saying that in public, but he still has strong poll numbers and is in good standing with the party’s elected officials (Pelosi).

Biden has not been eliminated by this controversy. But it has to have shown him that this will be a tough campaign if he enters. And he hasn’t entered yet, which tells me there must be some hesitancy on his part.

meredithconroy: Maybe the question (for another chat) is what kind of scandal rises to the level of hurting a candidate in the general election.

natesilver: Sure. It’s part of the process of the party deciding. Seeing who the party defends and who it doesn’t is important, as well as how capable candidates are at handling negative stories. But part of the process is also testing the candidate’s electability argument and looking for flaws that could cost them the general election.

The weird thing about the Biden story is that it’s very hard to see Trump, for obvious reasons, pressing back on Biden too much without it backfiring.

meredithconroy: You’d think so, right? But I think Republicans are happy to keep scandals like this Biden story in the news. The more that accusations against men that don’t seem to rise to the level of harassment are litigated online, the more conservative voters are mobilized against something that they find really fishy in American politics today, which is believing women to a fault. Or falsely accusing men.

natesilver: Yeah, that’s a fair point, Meredith. So maybe we are overlooking the possibility of a backlash to the backlash against Biden?

I don’t want to reveal too much because it was a private conversation, but I was talking to an older (male) Democratic friend this weekend and I’d guess he’s probably more likely to vote for Biden now than he was before. He was also very against how Democrats handled the Al Franken accusations. And Kirsten Gillibrand’s campaign seems to be totally flatlining in part because she spoke out about Al Franken and Bill Clinton.

meredithconroy: I absolutely think Franken looms large in the minds of Democrats. Aaron Blake at the Washington Post wrote on Monday that “there is a palpable sense that Democrats overreacted and that Franken was a victim of too high a standard.”

Democrats have become the party that voters trust more to handle incidents of sexual harassment and misconduct. A candidate who is known for being “handsy” with women, could jeopardize this.

natesilver: I think these accusations are likely to be more of a problem for Biden among party elites than among rank-and-file voters, but party elites are important, too.

From ABC News:

April 2, 2019

Why Trump Hasn’t Seen A Post-Mueller Boost In The Polls

The completion of Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election was widely portrayed as a turning point in Trump’s presidency. But so far it’s had little effect on his approval rating.

As of Monday night, Trump’s approval rating was 42.1 percent and his disapproval rating was 52.8 percent, according to FiveThirtyEight’s approval rating tracker, which is based on data all publicly-available polls. Those numbers are little changed from where they were – 41.9 percent approval and 52.9 percent disapproval – on Saturday, March 23, the day before Attorney General William Barr issued a four-page letter on the Mueller report to Congress. (The Mueller report itself has not yet been released to the public or to Congress, although Barr has pledged to release a redacted version of it by mid-April.)

Trump’s approval rating is little changed since the Barr letter

Trump approval and disapproval ratings in FiveThirtyEight polling average

Date

Event

Approve

Disapprove

March 1

Start of last month

42.0%

53.3%

March 21

Day before Mueller report filed to Barr

41.6

53.1

March 23

Day before Barr letter released

41.9

52.9

April 1

Current

42.1

52.8

While I’d urge a little bit of caution on these numbers – sometimes there’s a lag before a news event is fully reflected in the polls – there’s actually been quite a bit of polling since Barr’s letter came out, including polls from high-quality organizations such as Marist College, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal, Quinnipiac University and the Pew Research Center which were conducted wholly or partially after the Barr letter was published. Some of these polls showed slight improvements in Trump’s approval rating, but others showed slight declines. Unless you’re willing to do a lot of cherry-picking, there just isn’t anything to make the case that much has changed.

In writing about the Barr letter just after it came out, I ducked making any sort of prediction about its effect on Trump’s numbers, saying it might or might not approve his approval ratings. Truth be told, if I were forced to put money on one side or another, I’d probably have expected them to improve by more than a few tenths of a percentage point.

With the benefit of hindsight, though, maybe this shouldn’t have been any sort of surprise. There are at least six reasons for why you might not have expected to see much of a change in Trump’s numbers. Here they are – note that these aren’t mutually exclusive and aren’t listed in any particular order of importance.

Reason No. 1: The Muller report itself hasn’t been released, so voters are reserving judgment.

Let’s start with the obvious. In every poll, overwhelming majorities of the public — typically on the order of 80 percent — think the entire Mueller report should be released for public consumption. Relatedly, most voters don’t think that the four-page letter that Barr published is an adequate substitute: A Washington Post-Schar School poll found that just 28 percent of the public thought Barr had released enough material against 57 percent who thought he hadn’t.

Reason No. 2: Trump’s approval ratings have been bound within an extremely narrow range, so this is par for the course.

As my colleague Geoffrey Skelley pointed out last week, the range of approval ratings for Trump has been exceptionally narrow. Excluding the first week of his presidency when there weren’t many polls to choose from, his approval rating has never been higher than 44.8 percent or lower than 36.4 percent in our average. Major news events such as Trump’s decision to fire FBI director James Comey in May 2017 and the government shutdown in December 2018 and January 2019 have moved his numbers, but only by 2 or 3 percentage points at a time. Other stories that were the subject of extensive news coverage, such as Trump’s reaction to the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August, 2017, had little discernible effect on his ratings.

A lot of this is because of extremely high partisanship. If the overwhelming majority of Democrats disapprove of Trump’s performance no matter what and the overwhelming majority of Republicans approve of it no matter what, there isn’t much room for his numbers to swing around. But it may also be because Trump generates so much news that voters already have a lot to weigh. One additional story — even one that voters paid quite a bit of attention to1 — isn’t likely to tip the scales that much.

Reason No. 3: Voters don’t necessarily see the Mueller report as exonerating Trump.

The NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found that only 29 percent of Americans — mostly Republicans — thought that “information available so far from the Mueller report” cleared Trump of “wrongdoing.” Meanwhile, 40 percent of Americans said it did not clear Trump, while 31 percent weren’t sure.

That ambivalence seems appropriate given the scant and somewhat confusing details available to the public so far. One of the few direct quotes from the Mueller report in Barr’s letter said that the investigation “did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.” But another directly quoted passage, apparently referring to whether Trump obstructed justice, said that “while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.”

Other polls have tried to tease out a distinction between whether Trump was cleared of colluding with the Russian government, and whether he was cleared of obstructing justice. They found a slightly larger shift in public opinion on the collusion question — something consistent with the sections of the Mueller report that Barr cited, which gave Trump a cleaner bill of health on collusion than obstruction. At the same time, there are lots of ambiguities that the public has to wrestle with, such as whether Mueller’s finding that he “did not establish” that the Trump campaign coordinated with Russia is the same thing as clearing Trump, especially given the variety of previous reporting on alleged ties between Russia and associates of the Trump campaign.

It’s also possible — indeed, inevitable — that some voters are reacting in a partisan way. That is to say, Democrats are reluctant to revisit their priors on collusion (and Republicans on the possibility of obstruction). Nonetheless, taken in the aggregate, the public’s measured response seems fairly appropriate given what is known (not that much) about the Mueller report so far.

Reason No. 4: The public’s expectations for Mueller’s findings were modest, and consistent with what they’ve learned so far.

People don’t like to admit they’ve changed their minds to pollsters, so what were the public’s expectations for the Mueller report before it was filed?

There are several polls that asked voters about their expectations; unfortunately, none of them are all that recent, and they have somewhat inconsistent findings:

A HarrisX poll in September 2018 found that 39 percent of voters thought Mueller had “uncovered evidence of the Trump campaign colluding with Russian officials during the 2016 campaign,” compared with 36 percent who did not and 25 percent who were not sure.

A Suffolk University poll in December 2018 had 46 percent of the public saying that “Trump associates” had definitely colluded with Russia in 2016, compared with 29 percent who said definitely not and 19 percent who were not sure.

A Quinnipiac poll in July 2018 found that 39 percent of voters thought Trump had colluded with Russia as compared to 48 percent who did not. On a separate question about whether the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia, 46 percent said yes and 44 percent said no.

There are some wording differences in these polls — and only the HarrisX poll asked about the Mueller report’s findings specifically. Still, taken as a whole they reveal a fair amount of ambivalence and uncertainty about where Mueller would land. The data doesn’t particularly square with the idea, popular in critiques of how the media covered the Russia story, that there was a single dominant media narrative about Trump and Russia.

Reason No. 5: The Russia investigation isn’t a big priority for voters.

In addition to not seeing the Barr letter as hugely informative, most of the public didn’t care that much about Russia in the first place. A Gallup poll taken in October 2018 in advance of the midterms found that the Russia investigation ranked last in importance among 12 issues that Gallup asked about, with 45 percent of voters saying it was very important or extremely important to their vote for Congress. By comparison, 80 percent of voters said that about health care, the top-ranked issue.

Views on the importance of Russiagate were highly partisan: 66 percent of Democrats2said it was very or extremely important, as compared to just 19 percent of Republicans.3 That helps to explain why Russia got so much coverage on MSNBC and CNN, which have largely Democratic audiences. At the same time, if (a) only partisan Democrats cared very much about Russia and (b) those Democrats have plenty of other reasons to dislike Trump anyway and (c) they aren’t likely to be persuaded by the Barr letter besides that, you can see why the end of the investigation hasn’t moved the needle much in terms of Trump’s overall approval.

Reason No. 6: The public largely doesn’t trust the White House on Russia, and the White House’s attempts at spin may have backfired.

Given that the mainstream media headlines were initially quite favorable for Trump, it could have been a moment for the White House to demonstrate more magnanimity than usual, and to improve trust by appearing eager for the release of the full Mueller report.

Instead, as is often the case, the White House’s strategy in the wake of the Barr letter seemed largely aimed at pleasing their base and dunking on Democrats rather than winning over swing voters. Trump claimed that he’d had a “complete and total EXONERATION” when the quoted sections of the Mueller report explicitly did not exonerate him from obstruction claims. He and Republicans were sometimes cagey about how much of the Mueller report should be released, with Trump at one point seeming to suggest that the White House might as well not bother to release the Mueller report since Democrats wouldn’t believe it anyway. All of this came against a background where, according to a Suffolk University poll conducted last month before the Mueller report was filed, only 30 percent of the public had a lot of trust in Trump’s denial about collusion, as compared to 52 percent who had little or none.

And as we discussed on our podcast this week, the White House also picked some odd, unpopular issues to pivot toward. Another White House-led attempt to repeal Obamacare could be a political gift to Democrats, who won 75-23 in last November’s midterms among the 41 percent of voters who ranked health care as their top issue. The White House even found itself embroiled in a controversy about its proposed budget that would cut federal funding for the Special Olympics, the sort of thing that would sound like an April Fool’s Day joke if it wasn’t real.

Trump can still breathe a huge sigh of relief that the indictments are apparently finished, and that the Mueller report4 didn’t conclude that he’d colluded with Russia. As I wrote last month, that removes a considerable amount of downside risk from Trump’s portfolio. But he also hasn’t realized very much political upside from the investigation’s end so far.

The End Of The Mueller Probe Hasn’t Been A Game-Changer For Trump

The completion of Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election was widely portrayed as a turning point in Trump’s presidency. But so far it’s had little effect on his approval rating.

As of Monday night, Trump’s approval rating was 42.1 percent and his disapproval rating was 52.8 percent, according to FiveThirtyEight’s approval rating tracker, which is based on data all publicly-available polls. Those numbers are little changed from where they were – 41.9 percent approval and 52.9 percent disapproval – on Saturday, March 23, the day before Attorney General William Barr issued a four-page letter on the Mueller report to Congress. (The Mueller report itself has not yet been released to the public or to Congress, although Barr has pledged to release a redacted version of it by mid-April.)

Trump’s approval rating is little changed since the Barr letter

Trump approval and disapproval ratings in FiveThirtyEight polling average

Date

Event

Approve

Disapprove

March 1

Start of last month

42.0%

53.3%

March 21

Day before Mueller report filed to Barr

41.6

53.1

March 23

Day before Barr letter released

41.9

52.9

April 1

Current

42.1

52.8

While I’d urge a little bit of caution on these numbers – sometimes there’s a lag before a news event is fully reflected in the polls – there’s actually been quite a bit of polling since Barr’s letter came out, including polls from high-quality organizations such as Marist College, NBC News and the Wall Street Journal, Quinnipiac University and the Pew Research Center which were conducted wholly or partially after the Barr letter was published. Some of these polls showed slight improvements in Trump’s approval rating, but others showed slight declines. Unless you’re willing to do a lot of cherry-picking, there just isn’t anything to make the case that much has changed.

In writing about the Barr letter just after it came out, I ducked making any sort of prediction about its effect on Trump’s numbers, saying it might or might not approve his approval ratings. Truth be told, if I were forced to put money on one side or another, I’d probably have expected them to improve by more than a few tenths of a percentage point.

With the benefit of hindsight, though, maybe this shouldn’t have been any sort of surprise. There are at least six reasons for why you might not have expected to see much of a change in Trump’s numbers. Here they are – note that these aren’t mutually exclusive and aren’t listed in any particular order of importance.

Reason No. 1: The Muller report itself hasn’t been released, so voters are reserving judgment.

Let’s start with the obvious. In every poll, overwhelming majorities of the public — typically on the order of 80 percent — think the entire Mueller report should be released for public consumption. Relatedly, most voters don’t think that the four-page letter that Barr published is an adequate substitute: A Washington Post-Schar School poll found that just 28 percent of the public thought Barr had released enough material against 57 percent who thought he hadn’t.

Reason No. 2: Trump’s approval ratings have been bound within an extremely narrow range, so this is par for the course.

As my colleague Geoffrey Skelley pointed out last week, the range of approval ratings for Trump has been exceptionally narrow. Excluding the first week of his presidency when there weren’t many polls to choose from, his approval rating has never been higher than 44.8 percent or lower than 36.4 percent in our average. Major news events such as Trump’s decision to fire FBI director James Comey in May 2017 and the government shutdown in December 2018 and January 2019 have moved his numbers, but only by 2 or 3 percentage points at a time. Other stories that were the subject of extensive news coverage, such as Trump’s reaction to the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August, 2017, had little discernible effect on his ratings.

A lot of this is because of extremely high partisanship. If the overwhelming majority of Democrats disapprove of Trump’s performance no matter what and the overwhelming majority of Republicans approve of it no matter what, there isn’t much room for his numbers to swing around. But it may also be because Trump generates so much news that voters already have a lot to weigh. One additional story — even one that voters paid quite a bit of attention to1 — isn’t likely to tip the scales that much.

Reason No. 3: Voters don’t necessarily see the Mueller report as exonerating Trump.

The NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found that only 29 percent of Americans — mostly Republicans — thought that “information available so far from the Mueller report” cleared Trump of “wrongdoing.” Meanwhile, 40 percent of Americans said it did not clear Trump, while 31 percent weren’t sure.

That ambivalence seems appropriate given the scant and somewhat confusing details available to the public so far. One of the few direct quotes from the Mueller report in Barr’s letter said that the investigation “did not establish that members of the Trump Campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government in its election interference activities.” But another directly quoted passage, apparently referring to whether Trump obstructed justice, said that “while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.”

Other polls have tried to tease out a distinction between whether Trump was cleared of colluding with the Russian government, and whether he was cleared of obstructing justice. They found a slightly larger shift in public opinion on the collusion question — something consistent with the sections of the Mueller report that Barr cited, which gave Trump a cleaner bill of health on collusion than obstruction. At the same time, there are lots of ambiguities that the public has to wrestle with, such as whether Mueller’s finding that he “did not establish” that the Trump campaign coordinated with Russia is the same thing as clearing Trump, especially given the variety of previous reporting on alleged ties between Russia and associates of the Trump campaign.

It’s also possible — indeed, inevitable — that some voters are reacting in a partisan way. That is to say, Democrats are reluctant to revisit their priors on collusion (and Republicans on the possibility of obstruction). Nonetheless, taken in the aggregate, the public’s measured response seems fairly appropriate given what is known (not that much) about the Mueller report so far.

Reason No. 4: The public’s expectations for Mueller’s findings were modest, and consistent with what they’ve learned so far.

People don’t like to admit they’ve changed their minds to pollsters, so what were the public’s expectations for the Mueller report before it was filed?

There are several polls that asked voters about their expectations; unfortunately, none of them are all that recent, and they have somewhat inconsistent findings:

A HarrisX poll in September 2018 found that 39 percent of voters thought Mueller had “uncovered evidence of the Trump campaign colluding with Russian officials during the 2016 campaign,” compared with 36 percent who did not and 25 percent who were not sure.

A Suffolk University poll in December 2018 had 46 percent of the public saying that “Trump associates” had definitely colluded with Russia in 2016, compared with 29 percent who said definitely not and 19 percent who were not sure.

A Quinnipiac poll in July 2018 found that 39 percent of voters thought Trump had colluded with Russia as compared to 48 percent who did not. On a separate question about whether the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia, 46 percent said yes and 44 percent said no.

There are some wording differences in these polls — and only the HarrisX poll asked about the Mueller report’s findings specifically. Still, taken as a whole they reveal a fair amount of ambivalence and uncertainty about where Mueller would land. The data doesn’t particularly square with the idea, popular in critiques of how the media covered the Russia story, that there was a single dominant media narrative about Trump and Russia.

Reason No. 5: The Russia investigation isn’t a big priority for voters.

In addition to not seeing the Barr letter as hugely informative, most of the public didn’t care that much about Russia in the first place. A Gallup poll taken in October 2018 in advance of the midterms found that the Russia investigation ranked last in importance among 12 issues that Gallup asked about, with 45 percent of voters saying it was very important or extremely important to their vote for Congress. By comparison, 80 percent of voters said that about health care, the top-ranked issue.

Views on the importance of Russiagate were highly partisan: 66 percent of Democrats2said it was very or extremely important, as compared to just 19 percent of Republicans.3 That helps to explain why Russia got so much coverage on MSNBC and CNN, which have largely Democratic audiences. At the same time, if (a) only partisan Democrats cared very much about Russia and (b) those Democrats have plenty of other reasons to dislike Trump anyway and (c) they aren’t likely to be persuaded by the Barr letter besides that, you can see why the end of the investigation hasn’t moved the needle much in terms of Trump’s overall approval.

Reason No. 6: The public largely doesn’t trust the White House on Russia, and the White House’s attempts at spin may have backfired.

Given that the mainstream media headlines were initially quite favorable for Trump, it could have been a moment for the White House to demonstrate more magnanimity than usual, and to improve trust by appearing eager for the release of the full Mueller report.

Instead, as is often the case, the White House’s strategy in the wake of the Barr letter seemed largely aimed at pleasing their base and dunking on Democrats rather than winning over swing voters. Trump claimed that he’d had a “complete and total EXONERATION” when the quoted sections of the Mueller report explicitly did not exonerate him from obstruction claims. He and Republicans were sometimes cagey about how much of the Mueller report should be released, with Trump at one point seeming to suggest that the White House might as well not bother to release the Mueller report since Democrats wouldn’t believe it anyway. All of this came against a background where, according to a Suffolk University poll conducted last month before the Mueller report was filed, only 30 percent of the public had a lot of trust in Trump’s denial about collusion, as compared to 52 percent who had little or none.

And as we discussed on our podcast this week, the White House also picked some odd, unpopular issues to pivot toward. Another White House-led attempt to repeal Obamacare could be a political gift to Democrats, who won 75-23 in last November’s midterms among the 41 percent of voters who ranked health care as their top issue. The White House even found itself embroiled in a controversy about its proposed budget that would cut federal funding for the Special Olympics, the sort of thing that would sound like an April Fool’s Day joke if it wasn’t real.

Trump can still breathe a huge sigh of relief that the indictments are apparently finished, and that the Mueller report4 didn’t conclude that he’d colluded with Russia. As I wrote last month, that removes a considerable amount of downside risk from Trump’s portfolio. But he also hasn’t realized very much political upside from the investigation’s end so far.

April 1, 2019

Politics Podcast: What Will Biden Do?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

Former Vice President Joe Biden is leading Democratic primary polls, and all indications are that he intends to run for president in 2020. In this episode of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, the crew discusses the kinds of challenges his campaign could face and whether those might deter him.

Recently, former Nevada legislator Lucy Flores wrote in New York Magazine that Biden touched her shoulders, smelled her hair and kissed her head at a campaign rally for her lieutenant governor bid in 2014. She said he made her feel “uneasy, gross, and confused.”

The team also assesses why Trump’s approval rating has not improved since the attorney general said in a letter to Congress that special counsel Robert Mueller had not found evidence of a Trump-Russia conspiracy in his investigations into Russian influence in the 2016 election.

Also: The podcast team is heading to Texas for live shows in Austin and Houston in early May. Find more information on tickets here.

You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 28, 2019

Politics Podcast: Can Statistics Solve Gerrymandering?

More: Apple Podcasts |

ESPN App |

RSS

| Embed

Embed Code

The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering on Tuesday. The court is again considering whether lawmakers are allowed to draw district lines meant to dramatically benefit one party over another and — if not — how the courts should judge when lawmakers go too far.

In this episode of the FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast, mathematician Moon Duchin explains a statistical method for determining when maps become too partisan. On Tuesday, the justices discussed her proposed method, but we’ll have to wait to see whether they were convinced that it’s a potential solution.

This episode is part of our FiveThirtyEight On The Road series, which is brought to you by WeWork. You can listen to the episode by clicking the “play” button in the audio player above or by downloading it in iTunes , the ESPN app or your favorite podcast platform. If you are new to podcasts, learn how to listen .

The FiveThirtyEight Politics podcast publishes Monday evenings, with additional episodes throughout the week. Help new listeners discover the show by leaving us a rating and review on iTunes . Have a comment, question or suggestion for “good polling vs. bad polling”? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

March 27, 2019

Will The Results Of The Mueller Investigation Matter In 2020?

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

sarahf (Sarah Frostenson, politics editor): Special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election is at long last over. After nearly two years, we have a summary of Mueller’s report from Attorney General William Barr, and that summary, in a letter to Congress, says that the Trump campaign did not coordinate with Russia. What’s less clear is where Mueller landed on the question of obstruction of justice: Barr’s summary says that the special counsel didn’t reach a conclusion, and we still don’t have the report.

This means we can expect a political fight until the full report is released, but how should House Democrats proceed in light of what information we do have? And how this could affect the 2020 election?

nrakich (Nathaniel Rakich, elections analyst): I don’t think it will affect 2020. None of the Democratic candidates was really hammering the Trump-Russia thing. And it doesn’t seem to be a major focus with voters either. In a recent CNN poll, respondents were asked to name what issue will be the most important to them in deciding whom to support in 2020, but not a single respondent mentioned the Russia investigation. And as for the campaign trail, Elizabeth Warren recently said to reporters that she wasn’t getting questions on the Mueller report from voters during events in Iowa and New Hampshire.

sarahf: I don’t know if it’s quite fair to say that 2020 candidates haven’t hammered the Trump-Russia thing at all. Beto O’Rourke did accuse President Trump of collusion with Russia in the 2016 election in a speech he gave on Saturday (before Barr’s letter was public).

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Are you saying that it won’t affect the 2020 general election? Or the 2020 Democratic primary?

nrakich: The primary.

There’s more of a chance it affects the general election. But attitudes do seem pretty baked in at this point.

natesilver: On the primary, I tend to agree, although the counter-factual where Mueller finds some huge smoking gun … it seems like things might be different then. At the very least, Democrats would have to stake out a clearer position on impeachment.

It is somewhat telling that none of the 2020 candidates had made the special counsel investigation a particular focus of their campaigns. Maybe you have someone like Beto who has talked about it, or maybe even said a few things he might consider walking back, but it’s not like it’s “Beto O’Rourke, the Russia candidate.”

Eric Swalwell sort of has tried to run on that in the invisible primary, and there doesn’t seem to be much interest in his campaign.

And Michael Avenatti was sort of running on that basis before he encountered … uh … other problems. And there wasn’t much of an appetite for an Avenatti campaign either, with him polling at 1 percent or so back when he was included in surveys.

nrakich: Yeah. Democratic congressional candidates in 2018 won largely by running on bread-and-butter issues, like health care. The 2020 candidates understand that.

And speaking of health care, Trump may have already stepped on his good-news surge from the Mueller report by bringing up Obamacare repeal again.

natesilver: Yeah. I mean, there’s just sort of so much that Trump is putting into the washing machine that both good stories and bad ones sort of all come out in the wash. (I think I butchered that metaphor.)

It’s not crazy to think that the Affordable Care Act could be more consequential to 2020 than the Mueller report. I don’t think I think that, but it’s not crazy. Rank-and-file voters care a lot about health care.

sarahf: But don’t you think that if House Democrats continue to pursue an investigation-heavy agenda, they risk alienating voters?

natesilver: I mean, I think the Michael Cohen testimony was fairly effective for Democrats. It was pointed and dramatic, and it took a day, rather than dragging on for months.

nrakich: And there are other investigations of Trump going on, including those over allegations of campaign-finance and emoluments clause violations.

natesilver: So, like, Democrats have to pick their shots. And maybe the threshold is higher, post-Mueller. But I don’t get the notion that they can’t pick their shots fairly effectively. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi seems to have pretty good control of her caucus.

sarahf: But I guess that’s my question. Will the American public have the same appetite for those investigations? Or do Democrats risk their investigations being viewed in too partisan of a light?

nrakich: I just don’t know that it will matter one way or the other.

natesilver: Remember that the Mueller report itself has not been released. And even though I’m quite skeptical that what’s in the Muller report can be that much worse for Trump than what’s in Barr’s summary, it will affect public perceptions quite a bit if Republicans are slow to release the Mueller report.

sarahf: That’s true — that could work in the Democrats’ favor. (House Democrats have demanded the Justice Department turn over the full report by April 2.)

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): Some of the Democrats in Congress are suggesting that the party should broadly back off of Trump-related investigations (not just the Russia probe) and focus more on policy. I think that’s an important internal debate where there will be different views in the caucus. Some members from purple/red districts have never been that excited about an anti-Trump focus, and I assume that the Mueller report news from last weekend will push them even further in that direction.

nrakich: Perry, I would agree with that if I were advising a presidential candidate, but I’m not sure that it’s going to matter what Congress does.

natesilver: Part of me wonders whether House Democrats will investigate Trump more than they “should” in the sense of it being politically optimal just because they have a lot of time on their hands.

They can’t really pass much legislation that’s going to get through the Senate and through Trump. But they sure as hell can investigate.

nrakich: It’s pretty normal for the House to ramp up the investigations under divided government.

And just glancing at the data, it doesn’t seem that the party in control of the House at that time suffered political consequences for it later on.

The strength of the candidates at the top of the ticket is probably what’s going to dictate if those red-district Democrats keep their seats in 2020.

perry: I do think the “release the report” argument from Democrats is important. Media reports that Trump tried to stop or stall the investigation are different from an official Justice Department report saying it and giving lots of details.

I think the Democrats can only gain from the Mueller report’s release. I’m not saying that it will change anyone’s vote in 2020 necessarily, but it will be useful for the Democrats to have the details out there.

sarahf: But OK, what does this mean for Republicans? How will they use the investigation in 2020?

perry: One way to look at it is that the results of the investigation weren’t great news for someone like Maryland’s Republican governor, Larry Hogan, who has been hinting that he is open to challenging Trump in a GOP presidential primary.

Not that Hogan had much of a chance to begin with, but this closes one potential avenue for a GOP challenger to Trump.

nrakich: Yeah, basically the only prayer for Bill Weld or another Republican hopeful was for Trump to be indicted, AND the economy to tank, AND the pee tape mentioned in the Steele dossier to come out … it had to be a perfect storm.

natesilver: I do want to push back at something Perry said first. Clearly, Democrats would not gain from the report being released if it’s extremely skeptical about anything resembling collusion.

perry: I felt like Barr’s summary was already pretty skeptical, so it’s hard to imagine the full report being even more skeptical.

natesilver: I just think there’s a middle ground where Barr can probably spin things a bit, but if he spins too much, it’s very risky if the report eventually gets released or if details surface through other means (i.e., leaks).

perry: In terms of the Republicans, I think Trump and his allies were going to attack the Justice Department officials who were involved in the Russia investigation and the media outlets that covered the investigative intensely no matter what. But that instinct to attack the media and the group of people who started the Russia investigation will be reinforced by this report.

I think a big part of Trump’s 2020 campaign will be an anti-institutional argument. Which he was making in 2016 too, I suppose, but the anti-media, anti-“deep state” part will be even more aggressive.

natesilver: It’s a thin line, though, for Trump to attack the media while also getting relatively friendly coverage about the Mueller report. And I’m not sure that I trust the White House to walk that line effectively. Like, I think they’ve been dunking a bit too much and not using this report to maximize their standing with swing voters.

sarahf: But just think of the chant at the rallies: NO COLLUSION!

natesilver: It will be “WITCH HUNT!!” “NO COLLUSION!!” like the old “TASTES GREAT!!” “LESS FILLING!!” commercials (dating myself here).

perry: I’m not sure this is a good election strategy. I just think it’s likely to be what happens — hating the media and the “deep state” is going to become a bigger part of GOP politics now.

natesilver: Yeah, and as I wrote a couple of days ago, Trump could stand to gain among Trump-skeptical Republicans who are also skeptical of the media.

sarahf: A key demographic to watch will also be independents and how they respond. As Nathaniel wrote previously, there was some polling that showed independents weren’t against the investigation. But I wonder if that changes or shifts now.

natesilver: Also given the timing of this … the Mueller report is coming early enough that if it had been really bad, Republicans could have considered taking an off-ramp from Trump.

But suppose, hypothetically, that there’s some new scandal. It’s going to take a lot of time to metastasize into something. And it’ll be too late for Republicans to nominate someone else for 2020, most likely.

So they’re probably fairly committed to Trump as their nominee at this point, and that’s likely to start affecting their behavior right away. Not that there was ever much of a chance that Republicans would nominate someone else, but if there was just the slightest bit of daylight, there’s less now.

perry: And you’re already seeing signs of that. Republicans like Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse, who used to criticize Trump a lot, are now trying to portray themselves as more pro-Trump.

Will it be harder for elected Republicans to criticize Trump when he does more outlandish things? I think so.

Trump has gained more and more control of the GOP over the past two years. And I think he’s strengthened by the ending of the uncertainty that surrounded the Mueller investigation while it was underway.

natesilver: So maybe that’s the simplest effect. It will increase the degree of party unity behind Trump.

perry: Jumping back to the Democrats, there are basically two camps among the presidential candidates. One group says that Trump is bad, but the country’s problems are much broader — rooted in the unequal power that the wealthy and elites wield. (Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders fall into this camp.) The other group says the problem is Trump and to some extent the Republican Party. (Most of the other candidates fall into this group.)

Because Trump has not been implicated by the Mueller investigation (at least based on Barr’s summary of the report), I think we’ll see Democratic primary candidates move toward the Warren-Sanders view. And that’s important.

I’m not sure if Warren or Sanders will win the primary, but it will be interesting to see if their broader vision takes hold within the party.

natesilver: My initial instinct, FWIW, was the opposite — that if the Mueller report has any effect (it probably/might not), it would help the more centrist candidates because Trump will be seen as more formidable now and therefore a higher premium will be placed on “electability.”

nrakich: It’s not a single spectrum, though. Perry is right that, say, Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand have been running more explicitly anti-Trump campaigns than Sanders and Warren have. But they’re all still lumped together as “progressive.”

natesilver: What about the Booker/Buttigieg/Beto gang, who have been running on a more upbeat, optimistic message?

perry: Electability is a huge focus of this primary. Full stop. But I also think the day-to-day exchanges in this campaign are about policy, and even people like Booker/Buttigieg/Beto

are moving toward more aggressive ideas like getting rid of the filibuster and the Electoral College.

It’s complicated. I feel like the primary is moving to the left on policy but is also really shaped by electability.

natesilver: It does seem like there are four quadrants. On the one hand, there’s “everything is going to hell” vs. “everything is going to be OK.” On the other hand, there’s “Trump is the biggest problem we’ve got” vs. “Trump is just a symptom of larger issues.”

sarahf: OK, so it sounds as though we think the effect of the Mueller report could be felt in two key ways in 2020:

There will be greater party unity behind Trump, regardless of how he chooses to spin the report’s findings (and setting aside the question of whether that’s a good strategy for winning swing voters).

Democratic presidential hopefuls might redirect their focus from Trump to saying the problem is bigger than Trump.

What else would you add?

nrakich: I’d just qualify No. 2 by saying that I don’t really think the Mueller report will have any effect on the primary. Primary voters are already partisan Democrats and have made up their minds about how shady Trump is.

natesilver: I don’t know. There was a mainstream media perception post-midterms, post-shutdown (Remember the shutdown? It wasn’t that long ago!) that Trump was in deep trouble and wasn’t so Teflon after all. Now you literally have headlines saying “TEFLON DON” and scoldy media people scolding other people in the media for underestimating Trump again. So the background climate changes a little bit.

Does it precipitate a change in behavior from the Democratic candidates? Maybe not.

nrakich: Yeah. Maybe it makes Democratic voters more concerned about the issue of electability in the short term. But “electability” means different things to different people. And in the long term, who knows?

natesilver: I’d just say that the Mueller news cycle already feels pretty different 48 hours later. You have some crazy stories — Avenatti, Jussie Smollett. You have the Justice Department taking a new position on Obamacare. You have this controversy over when and whether the Mueller report itself is going to be released. The news cycle moves on pretty quickly.

nrakich: Exactly.

I look forward to summer 2020 when we’re all talking about the political implications of Oprah giving every American a universal basic income.

March 26, 2019

Here’s How We’re Defining A ‘Major’ Presidential Candidate

How many Democrats are running for president? It’s not a trick question. And it’s not an easy question to answer.

Unfortunately, it’s also not a question we can really avoid. We’ll be writing about the Democratic primary for the next [checks notes] 16 months here at FiveThirtyEight, until the Democratic National Convention is held next July in Milwaukee. We’ll be making thousands of charts and graphics featuring these candidates, taping hundreds of podcast segments about them, and collecting heaps of data on their activities. While there’s some room for flexibility — I can mention Marianne Williamson’s name in passing without committing FiveThirtyEight to write a 2,000-word feature about her — we need to make a distinction between “major” candidates and everyone else for a lot of what we’re doing.

It would be nice to be extra inclusive, but that gets out of hand quickly. According to the Federal Election Commission, there were actually 209 (!) Democrats1 who had filed paperwork to run for president or form an exploratory committee as of last Friday afternoon, including luminaries such as Gidget Groendyk, Maayan Z. Zik, John Martini and Dakoda Foxx.

The Washington Post and New York Times have more modest lists of 15 Democratic candidates — but to be honest, their definition of who qualifies seems to be pretty arbitrary. For instance, Williamson, a self-help guru and best-selling author, is on both lists, but Wayne Messam — the mayor of Miramar, Florida, who this month formed a presidential exploratory committee — is not on either.

There are lots of other edge cases. What to do with entrepreneur Andrew Yang, who became Internet-famous and is now penetrating mainstream coverage of the 2020 race? What about Mike Gravel, who is an 88-year-old former U.S. senator and may be running for president — or who may just be helping some teenagers troll everybody? Then there is John Delaney, who is a former U.S. representative and has been languishing in obscurity despite having fairly traditional credentials for a presidential candidate.2 He’s been drawing a goose egg in most polls and failing to raise enough money to qualify for the debates despite having been running for president .

For better or worse, we need a set of relatively objective standards to distinguish major from minor candidates. So we’ll be introducing one in this article and revealing which candidates do and do not qualify so far. The fact that the standards are objective doesn’t mean they’re beyond reproach — there’s subjective judgment involved in determining which objective measures to use. (The judgment comes primarily from me and Nathaniel Rakich; everyone else politely ignored us while we went through several iterations of the qualifications in FiveThirtyEight’s politics Slack channel.) But they’re at least something we can apply consistently to all the candidates.

In fact, candidates will have two paths — plus one shortcut, which I’ll explain in a moment — to qualify as major by FiveThirtyEight’s standards. (Candidates must be officially running or have formed an exploratory committee to qualify; Joe Biden may be major, but he isn’t a candidate yet.) The first path is to meet the Democratic National Committee’s standards to qualify for the presidential debates. According to the DNC’s rules, candidates can qualify via either of the following ways:

Receive at least 1 percent of the vote in national or early-state polls from at least three separate pollsters on a list prepared by the DNC.

Receive donations from at least 65,000 unique individuals, including at least 200 donors in each of 20 states.

There are a couple of complications here. One is that we don’t necessarily expect the DNC to declare which candidates have and have not qualified until we get closer to the debates, which begin in June. So we’ll be determining this for ourselves, using their standards. We’ll also be taking candidates at their word when they claim to have reached 65,000 donors, unless we have some strong reason to doubt them; the DNC will seek to vet and verify their claims, by contrast.

Also, the DNC says that it will limit at least the first couple of debates to 20 candidates; if more than 20 qualify, they’ll use some other (ambiguous) method to decide who actually gets a podium. We’ll consider candidates to be major even if the DNC runs out of room for them, however.3

To be honest, we think the DNC standards are pretty generous. Getting 65,000 people to donate to you isn’t that much — Beto O’Rourke received donations from twice that many people within his first 24 hours!4 It’s also not that hard to hit 1 percent — just 1 percent! — in a handful of polls.

Nonetheless, we also have a second path open. It requires candidates to meet at least six of the following 10 criteria:

How we’re defining “major” presidential primary candidates

Candidates must meet the DNC’s debate qualifications via fundraising or polling OR meet at least six of these 10 criteria …

How actively the candidate is running

1.

Has formally begun a campaign (not merely formed an exploratory committee)

2.

Is running to win (not merely to draw attention to an issue)

3.

Has hired at least three full-time staffers (or equivalents)

4.

Is routinely campaigning outside of their home state*

What other people think of the candidate

5.

Is included as a named option in at least half of polls*

6.

Gets at least half as much media coverage as candidates who qualified for the debate*

7.

Receives at least half as much Google search traffic as candidates who qualified for the debate*

8.

Receives at least one endorsement from an endorser FiveThirtyEight is tracking

The candidate’s credentials

9.

Has held any public office (elected or appointed)

10.

Has held a major public office (president, vice president, governor, U.S. Senate, U.S. House, mayor of a city of at least 300,000 people, member of a presidential Cabinet)

The criteria are applied to the trailing 30 days.

* “Routinely campaigning” means being on the road, hosting events open to the public, for at least two weeks out of the previous 30 days. Polls include all state and national polls over the previous 30 days as tracked by FiveThirtyEight; however, each polling firm is counted only once. (If a candidate is mentioned by name in any of that polling firm’s polls over the previous 30 days, he or she counts as having been included.) Media coverage is based on the number of articles at NewsLibrary.com. Google search traffic is based on topic searches — rather than verbatim search strings — in the United States.

These standards are also meant to be pretty generous. If we think of those criteria as a point system, in which candidates get a point for every one they fulfill, someone can get to 4 points just by doing the basic blocking-and-tackling of a campaign: formally launching their bid, going out on the campaign trail, hiring a few staffers and claiming (however implausibly) that they’re in it to win it rather than (as Gravel has said) merely to draw attention to a favorite cause.5 In addition, candidates who are actively running can get 1 or 2 additional points if they have been elected or appointed to public office, depending on the stature of the position. So, candidates such as Delaney, U.S. Rep. Tulsi Gabbard and former Colorado Gov. John Hickenlooper can qualify as major based on actively campaigning (4 points) and their credentials as elected officials (2 points) alone.

For other candidates — those who have held only minor public offices or none at all, or those who are only campaigning half-heartedly — there are four additional ways to gain points, based on whether they’re included in polls, how much media coverage they’re getting and how much they’re being searched on Google, and whether they’ve been endorsed by anyone whom FiveThirtyEight is tracking. It’s really not that hard to get to 6 points.

There’s also the shortcut I mentioned before. If we consider it almost certain that a candidate will eventually qualify under either the first or the second path, we reserve the right to designate them as major even if they haven’t technically qualified yet. For instance, if John Kerry or Stacey Abrams were to run, they might not qualify right away because it would take the various metrics some time to catch up to their (somewhat unexpected) announcements, but they would almost certainly reach them within a few weeks. So we’d consider them to be major candidates from the start.

Which candidates have qualified so far?

By our accounting, 12 people have qualified for the debates under the DNC’s rules, one of whom (Biden) isn’t actually running yet. They also qualify as major under FiveThirtyEight’s rules, therefore.

Which candidates have qualified for the debates?

Candidates who achieved at least 1 percent in three DNC-approved polls through March 24, 2019

Candidate

CNN

Monmouth U.

Des Moines Register (Iowa)

UNH (N.H.)

Fox News

Biden

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Sanders

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Harris

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

O’Rourke

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Warren

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Booker

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Klobuchar

✓

✓

✓

✓

✓

Castro

✓

✓

✓

✓

Gillibrand

✓

✓

✓

✓

Buttigieg

✓

✓

✓

✓

Inslee

✓

✓

✓

Hickenlooper

✓

✓

Bloomberg

✓

✓

Brown

✓

✓

de Blasio

✓

✓

Yang

✓

✓

Delaney

✓

✓

Gabbard

✓

✓

Kerry

✓

Bennet

✓

Holder

✓

Bullock

✓

Shaded candidates have qualified for the debates under FiveThirtyEight’s interpretation of DNC rules, including Yang, who qualified on the basis of fundraising. According to the DNC: “Qualifying polls will be limited to those sponsored by one or more of the following organizations/institutions: Associated Press, ABC News, CBS News, CNN, Des Moines Register, Fox News, Las Vegas Review Journal, Monmouth University, NBC News, New York Times, National Public Radio (NPR), Quinnipiac University, Reuters, University of New Hampshire, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Washington Post, Winthrop University. Any candidate’s three qualifying polls must be conducted by different organizations, or if by the same organization, must be in different geographical areas.”

Eleven of these candidates — Biden, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, O’Rourke, Elizabeth Warren, Cory Booker, Amy Klobuchar, Julian Castro, Kirsten Gillibrand, Pete Buttigieg and Jay Inslee — have qualified on the basis of achieving at least 1 percent of the vote in three DNC-approved polls. A 12th candidate, Yang, has qualified by having at least 65,000 donors, according to his campaign. We reached out to various other campaigns that didn’t meet the DNC’s polling benchmark to ask whether their candidate had hit 65,000 donations, and none claimed to have done so.