Nate Silver's Blog, page 128

July 28, 2016

Election Update: Why Our Model Is Bullish On Trump, For Now

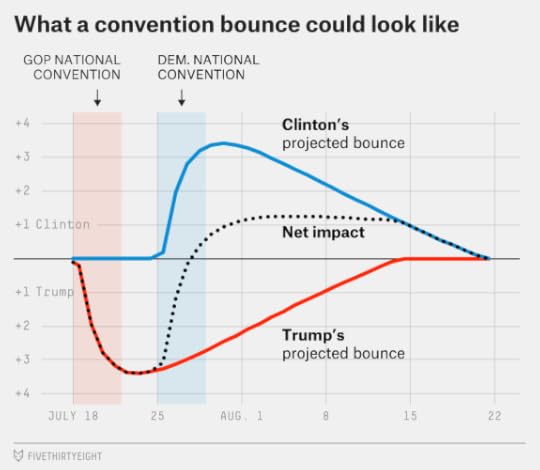

Further polling since the Republican National Convention has tended to confirm our impressions from earlier this week: Donald Trump has almost certainly gotten a convention bounce, and has moved into an extremely close race with Hillary Clinton. But Trump’s convention bounce is not all that large. You can find polls showing almost no bounce for Trump, and others showing gains in the mid-to-high single digits. Those disagreements are pretty normal and, overall, the polls suggest a net gain of 3 to 4 percentage points for Trump. That would be right in line with the average bounce in conventions since 2004, although it is toward the small side by historical standards.

Trump’s position in our polls-plus forecast, which adjusts for convention bounces, is almost unchanged over the past week; the model continues to give him about a 40 percent chance of winning the election, meaning that Clinton has a 60 percent chance.

Without adjusting for the convention bounce, however, the election is a dead heat. Our polls-only forecast, which doesn’t account for the convention bounce, gives Clinton just a 53 percent chance of winning, and our now-cast — which is more aggressive than the polls-only forecast and estimates what would happen in a hypothetical election held today — has Trump as a 55 percent favorite.

But I want to focus on some relatively technical subject matter today, apart from Trump’s convention bounce. FiveThirtyEight’s isn’t the only election forecast out there. Most of the others give Clinton a better chance than we do — some of them give her as high as an 80 percent chance, in fact, despite her recent slide in the polling. Why are our models more pessimistic about Clinton’s chances?

I’ve noticed that, when discussing differences between our forecasts and others, people tend to focus on which polls are included in the models or how the polls are weighted. The truth is, that stuff usually doesn’t matter very much. There are other things that make a much bigger difference.

One relatively important factor, for instance, is whether you use the version of polls with third-party candidates Gary Johnson and Jill Stein included, or the two-way matchup between Clinton and Trump instead. Recently, polls that included Johnson and Stein as options have been a percentage point or so worse for Clinton, on average. FiveThirtyEight’s models use the version of polls with third-party candidates when they have the choice, which slightly helps Trump.

Another question is how the models account for uncertainty in the forecast. For instance, if Clinton leads by 4 percentage points in a given state, how does that translate into her probability of winning it on Nov. 8? And given various probabilities of her winning each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, how does that translate into her probability of winning the Electoral College? This is tricky stuff, and we’ll save the detail for another day. For now, I’ll just say that it’s a mistake to assume that the error in each state is independent from the others: If both Ohio and Pennsylvania are tossups on Election Day, Clinton will probably either lose both or win both, instead of splitting them. This means that a narrow lead in the Electoral College is not as safe as it might seem.

But for the time being, most of the differences are caused by how quickly the models adjust to new polling data. Over the course of July, Clinton has steadily declined in the polls. How aggressive should a model be in accounting for that shift?

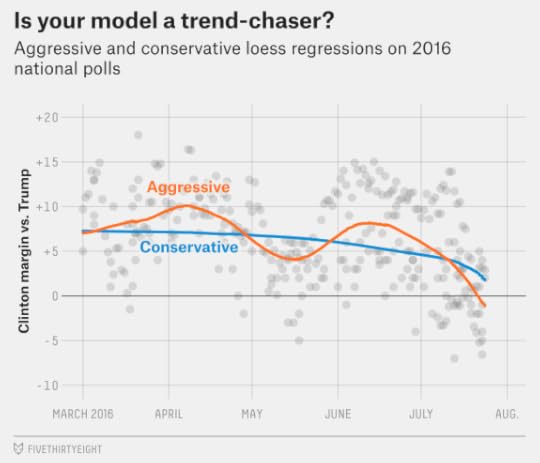

A lot of election models, including FiveThirtyEight’s, use a variation of loess regression as part of their process, a technique for drawing trend lines through a series of data. Loess regression is a good tool, but one problem is that it can draw rather different-looking trend lines through the same data, depending on something called the bandwidth or the smoothing parameter. Below, for instance, you’ll find two sets of loess curves based on all national polls since March 1. (Note: This is not the technique the FiveThirtyEight models use — for better or worse, our process is a lot more involved — but this will give you a taste of some of the challenges loess regression can present.)

The more aggressive trend line shows several peaks and valleys for Clinton. She rises in the polls in March and April, falls in May after Trump wraps up the Republican nomination, regains a significant lead in June, and then sees her numbers tumble in July. The more conservative trend line instead shows a slow and relatively steady decline for Clinton. And the two trend lines come to rather different conclusions about where the race stands right now: The conservative one still has Clinton ahead by about 2 percentage points, while the aggressive trend line has Trump up by 1 point.

So which one is correct? That’s another tricky question. If you’re using loess regression for descriptive purposes — to illustrate how the polls have moved in the past — the more aggressive trend line is clearly better. It does a much better job of capturing movement in the polls — we had more than enough data to know that Clinton moved up in the polls from May to June, for instance. But if you’re using loess to make predictions — to anticipate where the polls are going to go next — there’s an argument for using a more conservative setting. That’s because short-term movement in the polls often reverses itself — a candidate gets a bad news cycle, and she drops a couple of percentage points, but she recovers them once the news moves along to another subject. The convention bounce is one example of this, in fact, since the bounces often reverse themselves after a few weeks.

We spent a lot of time on this issue when originally building our model in 2008 and then when revising it in 2012 and earlier this year, trying to figure out how aggressive these loess curves should be in order to maximize predictive accuracy. The short answer is that you want an aggressive setting — very aggressive, in fact — late in the campaign, and a more conservative one earlier on.2 Still, it’s certainly also possible to be too conservative, which could mean missing the considerable shift away from Clinton that began a few weeks ago in the polls, well ahead of the conventions.

Related:July 27, 2016

Why Obama Might Be Trump’s Biggest Challenge

In this week’s politics chat, we talk about President Obama and his role in the 2016 election. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): This chat comes to you live from the lobby of the Aloft Philadelphia Airport hotel. Today’s topic: President Obama, who speaks to all the assembled delegates and media at the Democratic National Convention tonight. Two main questions for your consideration today: 1. Obama’s approval rating has been rising — why? 2. What effect will Obama have on the race? (And what effect do incumbent presidents have on open races generally?)

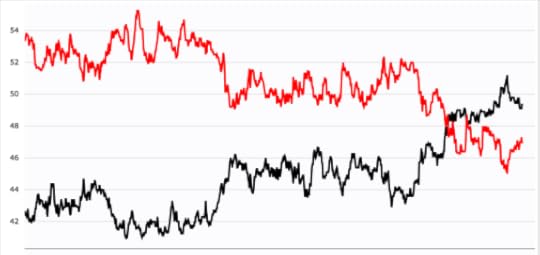

Let’s start with Obama’s increasing popularity. This chart from RealClearPolitics shows Obama’s approval (black) and disapproval (red) ratings:

What are the prevailing theories as to why Obama’s approval rating is up? (Also, side note: Harry is traveling while we do this chat so will only be participating sporadically.)

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): The main theory: Voters dislike Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, so Obama looks better by comparison.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Yeah, the specter of both Trump and Clinton — people are realizing how good they have it. Harry and I are on same page.

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): How confident are we about that theory? I mean, it’s intuitively compelling. But maybe Obama’s approval rating is ticking up for other reasons? The economy isn’t bad? He seems to pivot reasonably well off a GOP Congress? People are feeling sentimental since his term is about to end?

I will acknowledge that the shifts line up reasonably well with when it became clear that Trump and Clinton would become their respective party’s nominees.

micah: Do presidents’ approval ratings typically go up near the end of their second terms?

natesilver: They typically go up VERY late in the second term — like, once they become a lame duck. A little early for that now, though.

micah: I find the comparison to Trump and Clinton theory pretty compelling, especially because other events on the world stage haven’t exactly been morale-boosting.

clare.malone: Occam’s razor — isn’t that what it is, Nate? Clinton/Trump making him look better? (I’ve been here long enough that now I’m using all these stupid buzzzzzz terms.)

natesilver: Well, the contrast with the right track/wrong track numbers, which are bad, is pretty striking. “We think the country is going to hell BUT we sorta like that Obama guy!”

harry: Yeah, but those right track numbers have been bad for a while.

natesilver: It’s also become sort of politically convenient — on both the left and the right — to say the country is in decline. Pessimism sells. Which is not to say the United States doesn’t have VERY profound problems. But if you ask people about their personal circumstances, they feel a lot better than if you ask them about how everyone else is doing.

micah: Clare, in your reporting at Trump rallies and Clinton events, does Obama ever come up when talking to people?

clare.malone: Obama came up a lot more when people like Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio were in the race. Those guys were talking a whole lot more about how they thought that Obama was trying to adversely change American society. Trump talks just a ton about Clinton and honestly not that much about Obama these days (save for today).

natesilver: Which is why it will be interesting to see how much Obama takes on Trump tonight.

micah: Yeah, so let’s get to that: What do you expect from Obama tonight?

clare.malone: I think he’s going to basically say, “I know this job and all its perils and moral decision-making, the stresses, the seriousness of it — Donald Trump has not shown he is a serious person, a person intellectually up to the job.”

He’s going to make the qualification argument against Trump, whereas Michelle Obama made the ethical argument against Trump.

natesilver: As is true for most of these speeches, there are four basic directions he could take: (1) praise Clinton, (2) articulate Democrats’ values, (3) talk about how the country is making progress, (4) slam Trump.

So far, we’ve seen a lot of No. 1 and No. 2 at the convention. Which means Obama — and Joe Biden — might be more inclined to No. 3 and No. 4. It would be quite dramatic if Obama REALLY laid into Trump. Probably unusual for a sitting president to do that, although I’d need a historian to confirm that. And he has to avoid violating Michelle Obama’s credo of “when they go low, we go high.”

So it’s a high-stakes speech. I can see a universe in which Biden really goes after Trump and Obama is more subdued. It does seem a safe bet that SOMEONE is going to have to give the rip-Trump-to-shreds speech at some point, à la what Chris Christie did to Hillary Clinton. I just don’t know if it’s going to be the POTUS.

micah: I don’t think it will be Obama.

harry: I wouldn’t be surprised if it were Biden.

clare.malone: Obama doesn’t have to say Trump’s name to attack him. He could talk about the weight and seriousness of the office — people get the point, I think. Our brains haven’t turned all to Pokemon mush just yet.

micah: Give it time.

natesilver: I think the over-under line is that it will contain a few very pointed lines of criticism about Trump. A little could go a long way.

micah: Let’s zoom out for a second, beyond tonight’s speech — what effect do incumbent presidents have on open races?

Isn’t there some David Axelrod quote where he says every election is a referendum on the incumbent president?

natesilver: We don’t know because there have been only four term-limited presidents in the history of the United States. Five, counting Obama.

Obviously, you’d rather have the incumbent president be more popular than not. But it isn’t a 1-to-1 relationship. Bill Clinton had a better approval rating in 2000 than Reagan did in 1988. But George H.W. Bush won big, whereas Al Gore lost (err … tied, basically).

clare.malone: I remember having a conversation in a car in Iowa about whether Obama would have won the 2016 election if he were allowed to run. I think we decided he had a pretty good shot. While there might not be hard evidence, the fact that Hillary Clinton is standing on the shoulders of a fairly successful administration helps her, at least in the very specific case of 2016, when a lot of people don’t personally like the candidate running on the incumbent party’s ticket.

natesilver: There’s a contrarian case to be made that Obama’s approval ratings are improving precisely because he’s leaving the partisan fray … and that wouldn’t be true if he were eligible (and running for) a third term.

In fact, there’s a whole contrarian case to be made that Clinton’s unpopularity is a result of circumstances that might have affected any Democratic nominee and aren’t all that personal to her.

But … I don’t know. I tend to think Obama would wipe the floor with Trump.

micah: But Nate, isn’t the incumbent president’s approval rating really predictive?

natesilver: It’s really predictive when the incumbent is running for re-election. It’s moderately predictive when the incumbent isn’t.

micah: Trump, in a news conference in Florida going on as we chat, just called Obama “the most ignorant president” in American history.

natesilver:

Trump: 'I think President Obama has been the most ignorant president in American history.'

— Byron York (@ByronYork) July 27, 2016

I mean, from a Politics 101 standpoint, this is dumb. It’s possible that Trump is more popular — or less unpopular — than Clinton. He’s much less likely to win a popularity contest against Obama.

micah: That’s the thing. Part of this convention seems like presenting the race as the Clintons and the Obamas vs. Trump.

clare.malone: Hah.

micah: Oh, and Tim Kaine.

clare.malone: Poor Tim Kaine — no one’s paying him any mind. I guess that’s the point.

micah: Yeah, I don’t think the Clinton campaign is necessarily unhappy with that.

All right, next topic: Has the 2016 race generally, and the conventions in particular, made you re-evaluate Obama’s tenure? Re: our first question, it seems to have for the American people.

natesilver: My instinct, especially if you also look at what’s going on elsewhere in the world, is that it seems more remarkable that Obama was able to hold things together.

micah: Expound on that. Hold what together?

natesilver: For one thing, the Democratic coalition. Obama is one of the things that unites the Clinton and Sanders wings of the party.

But for another, playing a long game, and being a calming influence, instead of being overreactive.

Obviously Obama’s critics would call that a lack of leadership, and I’m probably revealing my biases here.

clare.malone: Here’s the one thing I keep on thinking about vis à vis Obama and the moral authority of a president and who is fit to hold the office: executive orders and executive actions.

It’s no secret that because he faced a recalcitrant Congress, Obama took a lot of executive actions. He was also a president famous for making a “kill list” for terrorists that seemed to many to operate outside the bounds of what many were previously constitutionally comfortable with. With Trump on the scene, with his recent comments about Russia and NATO, I have been thinking about the precedent that Obama set when it comes to executive actions.

What kind of actions would Trump take as president? Obviously, the Republicans have bemoaned Obama’s unilateral decision-making, but politics is all about using what’s expedient — once you’re in office and your predecessor has set a precedent, there’s very little to stop you from using it to your own ends.

micah: And that goes to Nate’s point about Obama holding things together — there are a lot of people, I imagine, who are fine with Obama doing those things who would not be fine with Trump doing the same, or even Clinton.

harry: People like Obama in ways they never liked Clinton. People trust him.

clare.malone: Yeah, and I think that’s the problem of Obama setting this precedent in a democracy — not all leaders are alike or as trusted. The system was put in place to guard against the misuse of power. Consolidation of power into anyone’s hands, even hands we trust at any given moment, should be seriously thought about.

That’s not a question of politics, I don’t think. It’s more about political philosophy, but man, political philosophy is lived by a person who holds the highest office in the land.

natesilver: Many, many people in the country don’t trust Obama. But in comparison to Trump or Clinton? They think he’s St. Francis. They think he’s basically acting in good faith.

micah: What are Obama’s trust numbers, Harry?

harry: Obama has generally been trusted even when his approval rating has been down.

clare.malone: Yeah, but same thing, Nate — good faith or trust. Obama has in many ways fundamentally changed the way a president acts in modern war and in some cases, on the domestic policy front. That is existentially troubling. (I say “existential” too much this year, but man …)

I’ve been living in one variety or another of a Potemkin village for the past 10 days. I’m feeling gnarly and existential and reflective, man.

natesilver: I think the country could really use three weeks off to watch the Olympics, or whatever. But I get the feeling it will be as crazy as ever.

micah: All right, final question. It’s fill in the blank: “Without Obama, Hillary Clinton’s support (currently about 41 percent in national polls, according to our polls-only model) would be ___ percentage points lower.”

In other words, does Obama matter on the margins? Or is he like super-important for Clinton?

natesilver: Ehh. I know where you’re going with that, but it’s a weird question.

My general view is that Obama’s influence is mostly priced into Clinton’s numbers at this point. In other words, I wouldn’t necessarily expect her numbers to improve just because Obama is more popular than she is.

But there’s one exception, I think, and that’s with Sanders voters.

clare.malone: Nate, you must be really bad at Mad Libs. This is a long fill in the blank.

natesilver: Clare, I don’t like to reduce everything to numbers.

clare.malone: Right, that’s just me. I apologize. Carry on — don’t let Micah box you in!

harry: I think if Obama’s approval were 5 points lower, Trump would be leading in all our models.

clare.malone: Huh. She’s living on that much of a razor’s edge?

harry: Yes.

natesilver: But is Obama’s approval rating a cause or an effect of political conditions? That’s why I think it’s weird to consider the president’s approval rating to be a “fundamental” variable, which is somehow detached from the horse race.

micah: OK, we gotta wrap.

clare.malone: So I guess you’re not getting an answer to your question, Micah. It’s an unknown unknown.

micah: I never get what I want.

clare.malone: NO, a known unknown. It’s unknowable. Whatever.

natesilver: Look, tonight’s speech is really important. If Obama’s approval ratings help Clinton, this convention is when she’s gonna get that help.

micah: That’s a good place to end.

Was The Democratic Primary A Close Call Or A Landslide?

Hillary Clinton will officially become the Democratic nominee for president this week, at which point we’ll finally close the chapter on the 2016 primaries. But when we look back on the 2016 race, how should we think of it, as a close call or as a blowout? Could a few small changes have made Sanders the nominee — and could a higher-profile candidate such as Elizabeth Warren have beaten Clinton, when Sanders didn’t?

My view is that the race wasn’t really all that close and that Sanders never really had that much of a chance at winning. From a purely horse-race standpoint, in fact, the media probably exaggerated the competitiveness of the race. But that’s not to diminish Sanders’s accomplishments in terms of what they mean for the Democratic Party after 2016. It’s significant that Sanders in particular — and not Warren or Joe Biden or Martin O’Malley — finished in second place.

There’s no agreed-upon standard for determining whether a nomination campaign was close or lopsided. Delegates might seem like the logical starting point; Clinton beat Sanders by 359 pledged delegates, and 884 delegates overall (counting superdelegates). But delegates don’t make for easy historical comparisons because the rules for delegate allocation change from party to party and election to election. As FiveThirtyEight contributor Daniel Nichanian pointed out, Clinton would have had a gargantuan win in pledged delegates — perhaps in excess of 1,000 delegates more than Sanders — if the Democratic nomination had been contested under Republican primary rules, which are winner take all or winner take most in many states. There’s also that sticky question of how to count superdelegates.

An alternative is to look at the aggregate popular vote, which makes for easier comparisons to past elections. According to The Green Papers, Clinton won 16.8 million votes to 13.2 million for Sanders, or about 55 percent of the vote to his 43 percent, a 12 percentage point gap.1

If Clinton had won by that sort of margin in a general election, we’d call it a landslide; her margin over Sanders was similar to Dwight D. Eisenhower’s over Adlai Stevenson in 1952, for example, when Eisenhower won the Electoral College 442-89. By the standard of a primary, however, Clinton’s performance was more pedestrian. The 55 percent of the popular vote she received is somewhat above average, in comparison to other open nomination races2 since 1972. Her 12-point margin of victory over her nearest opponent, Sanders, is below-average.

YEARPARTYNOMINEESHARE OF POPULAR VOTEPOPULAR VOTE MARGIN OF VICTORY2000DAl Gore75%+541988RGeorge H.W. Bush68+492000RGeorge W. Bush62+312004DJohn Kerry61+421980RRonald Reagan60+241996RBob Dole59+382016DHillary Clinton55+121992DBill Clinton52+322012RMitt Romney52+322008RJohn McCain47+252008DBarack Obama47-12016RDonald Trump45+201988DMichael Dukakis42+131976DJimmy Carter40+261984DWalter Mondale38+21972DGeorge McGovern25-1Which candidates dominated their nomination races?Sources: The Green Papers, Rhodes Cook, US Election Atlas, Wikipedia

That potentially understates Clinton’s performance, however, because Sanders never dropped out when a lot of other candidates in his position did, allowing the eventual nominee to run up the score in uncontested races. For instance, if you look at George W. Bush’s performance in the 2000 primary, it at first appears utterly dominant: He won 62 percent of the popular vote and beat his nearest rival, John McCain, by 31 percentage points.

But McCain dropped out of the race relatively early, after losing seven of nine states on Super Tuesday. At the time McCain dropped out, Bush led the popular vote only 51-43, less than the margin by which Clinton beat Sanders. Because of Republicans’ winner-take-all rules, McCain didn’t stand much chance of a comeback. (Then again, as I’ll argue later, Sanders never had much of a chance, either, after Super Tuesday.)

So we can rerun the previous table, this time freezing the numbers if and when the second-place candidate dropped out after Super Tuesday. Paul Tsongas was second in the popular vote to Bill Clinton when Tsongas dropped out in mid-March 1992, for example, so we’ll consider the race to have ended there, even though Jerry Brown continued a quixotic bid against Clinton and eventually lapped Tsongas into second.

POPULAR VOTEYEARPARTYNOMINEESHAREMARGIN OF VICTORYTOTALS THROUGH2000DAl Gore72%+46Bradley dropping out1996RBob Dole59+38End of race1988RGeorge Bush55+30Dole dropping out2016DHillary Clinton55+12End of race2004DJohn Kerry54+29Edwards dropping out2000RG.W. Bush51+8McCain dropping out1992DBill Clinton50+23Tsongas dropping out1980RRonald Reagan50+19Bush dropping out2008DBarack Obama47-1End of race2012RMitt Romney42+15Santorum dropping out1988DMichael Dukakis42+13End of race1976DJimmy Carter40+26End of race2016RDonald Trump40+13Cruz dropping out2008RJohn McCain38+6Romney dropping out1984DWalter Mondale38+2End of race1972DGeorge McGovern25-1End of raceWhich nominees were dominating when their top opponent quit?Sources: The Green Papers, Rhodes Cook, US Election Atlas, Wikipedia

Hillary Clinton’s performance is more impressive on this basis, given that Sanders contested the race to the end. Measured in this way, the 55 percent of the popular vote she received is tied for third-most out of 16 nominees, after Al Gore in 2000 and Bob Dole in 1996. And her 12-point margin over Sanders is roughly average, instead of below average.

But the calculation also potentially overstates the closeness of the Democratic race. College football stat geeks are fond of a concept called game control, which reflects how dominant the winning team was from start to finish. For instance, if Michigan State goes up two touchdowns early in a game against Ohio State, and Ohio State never makes it any closer than that, Michigan State will get a high game-control score even if they eventually win by “only” 17 points. By contrast, a team that trailed at halftime but eventually wins by 21 points after piling on in the fourth quarter won’t be considered all that dominant.

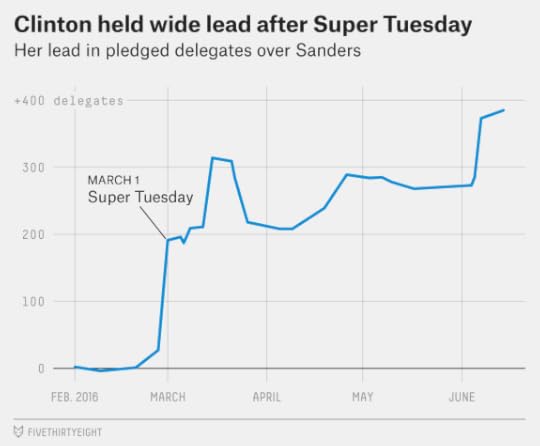

By this measure, Clinton was quite dominant. She trailed Sanders in pledged delegates only once, after Sanders won New Hampshire early on. But she regained the pledged delegate lead after Nevada and never looked back. After Super Tuesday on March 1, Clinton had a lead of 191 pledged delegates, and it never dropped below 187 pledged delegates the rest of the way:

Betting markets, although not a perfect measure, also remained extremely confident about Clinton’s chances from start to finish. According to Betfair, her probability of becoming the Democratic nominee shot up to 83 percent in October 2015 after Biden announced his intention not to run. From that point forward, her chances never dropped below 76 percent.

One reason for this confidence is that the Democratic race was quite predictable along demographic lines from start to finish. Polls and early results immediately made clear that Sanders would perform well in whiter states, while Clinton would perform well in states with substantial numbers of African-American and Hispanic voters. Before long, we also learned that Clinton tended to perform better in primaries — especially closed primaries — while Sanders did better in caucuses. Thus, once Clinton achieved victories in a series of diverse states in late February and early March — Nevada, South Carolina and the Super Tuesday states — it became fairly easy to extrapolate the rest of the race. Even states where the polls turned out to be wrong — underestimating Sanders in Michigan and Indiana or overestimating him in California, for example — weren’t that surprising on the basis of their demographics.

Related:July 25, 2016

Election Update: Trump Gets Convention Bounce, Drawing Polls To Dead Heat

The first few polls conducted after last week’s Republican convention suggested a small to medium convention bounce for Donald Trump, with Hillary Clinton holding on to narrow leads in several surveys. But a series of polls released Monday morning show bigger gains for Trump. In particular, Trump leads by 1 percentage point in a CBS News poll, by 5 percentage points in a CNN poll, and by 4 points in this week’s edition of the Morning Consult poll.1 He’s also extended his lead for 4 points in the USC Dornsife/Los Angeles Times tracking poll, although it has generally shown good results for Trump.

It isn’t straightforward to measure Trump’s convention bounce because he was already gaining ground on Clinton heading into the conventions, narrowing what had been a 6- to 7-point national lead for Clinton in June into roughly a 3-point lead instead. For instance, the CNN poll shows a massive 10-percentage-point swing toward Trump, but its previous poll was taken in mid-June, at a high-water mark for Clinton. By contrast, CBS News shows Trump gaining only 1 percentage point, but its previous poll was conducted earlier this month, shortly after the controversy over Clinton’s email scandal resurfaced.

But one method to measure the convention bounce is to look at FiveThirtyEight’s now-cast, our estimate of what would happen in an election held today. We don’t usually spend a lot of time writing about the now-cast because — uhh, breaking news — the election is scheduled for Nov. 8. The now-cast is super aggressive, and can overreact to small swings in the polls. But it’s useful if we want to get a snapshot of what the election looks like right now. It suggests that in an election held today, Trump would be a narrow favorite, with a 57 percent chance of winning the Electoral College.

The now-cast also suggests that Trump has gained a net of about 4 percentage points on Clinton in national polls from a week ago, turning a deficit of about 3 points into a 1-point lead. If so, Trump would turn out to have a fairly typical convention bounce. Over the past few cycles, convention bounces have been 3 to 4 percentage points, on average. As is also typical of convention bounces, Trump appears to have gained in the polls (taking votes from undecided and third-party candidates) more than Clinton has declined.

On the opposite side of the spectrum from the now-cast is our polls-plus forecast, which builds in a convention bounce adjustment. Because Trump’s convention bounce is broadly in line with its expectations, the polls-plus forecast hasn’t moved very much: It gives Trump a 42 percent chance of winning the Electoral College, up only slightly from last week.

Finally, there’s our polls-only forecast, which doesn’t have a convention bounce adjustment but is less aggressive than the now-cast. Clinton is very narrowly ahead in the polls-only forecast, although it’s close enough that a couple of strong polls could flip it to Trump.

If you have technical questions about how our models work, I’d encourage you to read our methodology primer. But in some ways, all of this detail is missing the forest for the trees.

On the one hand, the conventions are not a particularly good time to sweat every tick in the polls. Instead, they tend to be one of the less accurate times for polling. Historically, it’s unusual for candidates not to at least pull into a rough tie after their party convention — John McCain and Sarah Palin did so in 2008, for example, and even Walter Mondale led a couple of polls in 1984. But those bounces do not always turn out to be predictive.

If you must make a forecast, it’s probably better to adjust the polls (as the polls-plus model does) than not to adjust them. But even the polls-plus model is making what might best be described as an educated guess. Recent convention bounces have been relatively small, but historically, the polls have been highly volatile around the conventions, with convention bounces in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s sometimes running into the double digits. In some ways, the trajectory of the Clinton-Trump race so far has resembled a “vintage” presidential race, with wilder swings in the polls, as opposed to the 2004, 2008 and 2012 elections, when the polls were generally quite steady.

Related:Democratic Convention Preview: Can Democrats Get It Together?

The elections podcast crew is in Philadelphia! Since the end of the Republican National Convention, Hillary Clinton picked Tim Kaine as her running mate, Wikileaks gave us a glimpse behind the scenes at the Democratic National Committee, and Bernie Sanders die-hards descended on the City of Brotherly Love.

Nate Silver, Clare Malone, Harry Enten and Farai Chideya join Jody Avirgan to discuss what to expect from the Democrats’ week in the spotlight.

You can stream or download the full episode above. You can also find us by searching “fivethirtyeight” in your favorite podcast app, or subscribe using the RSS feed. Check out all our other shows.

If you’re a fan of the elections podcast, leave us a rating and review on iTunes, which helps other people discover the show. Have a comment, want to suggest something for “good polling vs. bad polling” or want to ask a question? Get in touch by email, on Twitter or in the comments.

July 23, 2016

Election Update: Is Trump Getting A Convention Bump?

Polls taken during and after the Republican National Convention, which concluded on Thursday in Cleveland, generally show Donald Trump continuing to gain ground on Hillary Clinton, making for a close national race. But it’s customary for candidates to receive a “bounce” in the polls after their convention. There’s not yet enough evidence to come to firm conclusions about the size of Trump’s convention bounce, but the initial data suggests that a small-to-medium bounce is more likely than a large one.

Before we run through the polls, a note of caution: The convention bounce is going to be harder than usual to study this year. That’s because in contrast to 2012, when the polls were extremely steady for weeks before the conventions, they were on the move heading into the RNC this year. In particular, they were on the move toward Trump — or away from Clinton — with Trump whittling down what had been a 6- or 7-percentage point lead for Clinton in late June into something more like a 3-point lead by mid-July.

So when you see a new poll suggesting that Trump has received a bounce, or failed to receive one, you’ll want to be mindful of when the previous edition of the poll was conducted. If the pollster had last surveyed the race in June, odds are that Trump has made some fairly big gains. Some of those were probably realized before the convention and not because of it, however. But if the previous edition of the poll was in July,1 his gains are likely to be smaller.

Keeping that in mind, here’s the data we have so far. First, there are three post-convention national polls, meaning that all of their interviews were conducted after Trump’s acceptance speech on Thursday night.

A RABA Research poll, conducted on Friday, shows Clinton 5 percentage points ahead of Trump, 39-34, with a large undecided and third-party vote. That sounds bad for Trump, but the trend line in the poll is favorable for him: The previous edition of the poll, conducted two weeks ago, had him down 12 points.A Gravis Marketing poll, conducted Thursday and Friday, has Trump 2 points ahead of Clinton. Their previous national poll, in late June, had Clinton up 2 points instead.2 Note, however, that Gravis has generally shown better results for Trump than most other pollsters.Finally, an Echelon Insights poll, conducted on Thursday and Friday, shows Clinton up by 1 percentage point, although Clinton’s lead grows to 4 points if Libertarian Gary Johnson and the Green Party’s Jill Stein aren’t included. Echelon Insights had not previously polled the election.You see what I mean? Measuring the convention bounce isn’t so straightforward. At first glance, it appears that the RABA Research poll is good for Clinton and the Gravis Marketing poll is good for Trump. But the RABA Research poll shows Trump making big gains and, furthermore, doing so in comparison to a July poll. By contrast, a 2-point lead in a Gravis Marketing poll is a pretty “meh” result for Trump, given that it has generally shown Trump-friendly results and that Trump didn’t improve all that much from its previous poll in June.

Meanwhile, Echelon Insights hadn’t conducted a pre-convention poll, so putting its numbers into context is hard. It’s interesting, however, that its poll shows a relatively large difference based on whether or not Johnson and Stein were included. It’s plausible that some of Trump’s post-convention gains will come from wayward conservatives who were thinking about voting for Johnson, so polls showing third-party candidates may show a larger bounce for him than those that don’t. Likewise, liberal voters who were contemplating a Johnson or Stein vote may move to Clinton after next week’s Democratic convention.

There are also a couple of polls that contain a mix of post-convention, pre-convention and during-convention data:

The USC Dornsife/LA Times tracking poll, conducted from last Saturday through Friday, has Trump up by 2 percentage points. That suggests very little bounce, given that Trump had been up by 1 percentage point in the poll before the convention.However, the Reuters/Ipsos tracking poll, conducted from Monday through Friday, shows Trump making major gains, trailing Clinton by less than 1 percentage point. Clinton had generally been up by around 10 percentage points in that poll before the convention began. Clinton’s lead is slightly larger, 3 percentage points, in the version of the poll without Johnson and Stein.Finally, a Rasmussen Reports poll, conducted during the convention on Monday and Tuesday, shows Trump ahead by 1 percentage point. That’s actually down from a 7-point lead for Trump in Rasmussen’s poll last week, although that poll had been a big outlier.This data is also pretty confusing. The massive gains Trump made in the Reuters/Ipsos are unabashedly good news for him. But their polling earlier in July had been something of a pro-Clinton outlier, so some gains for Trump were probably inevitable. Likewise, even though Rasmussen Reports has a long history of polls that show a statistical bias toward Republicans, a 7-point lead for Trump was a bit rich, even by Rasmussen standards, and the poll was likely to regress to the mean somewhat regardless of how effective Trump’s convention was. The trend lines in the USC poll aren’t great for Trump. But it only started publishing data a week or so ago, and the poll doesn’t include third-party candidates.

The FiveThirtyEight forecast models are helpful at times like this, but even they’re going to have trouble sorting everything out. Earlier this week, I wrote that “it would be a bad sign for Trump if he can’t at least tie Clinton in polls conducted in between the RNC and the DNC.” Our now-cast, which is very aggressive and addresses the question of what would happen in a hypothetical election held today, shows Clinton up by about 1 percentage point, so Trump has almost brought the race to a tie, but not quite. If Trump still trails in the now-cast after we get the next couple of polls in, the convention might qualify as disappointing for him, but it’s too soon to come to that conclusion. Meanwhile, Trump has continued to gain in our polls-only model, which is less aggressive than the now-cast but takes the polls at face value, whereas the trend in our polls-plus model, which builds in a convention bounce adjustment (it assumes that an average convention bounce is 3 to 4 percentage points) has been flat over the past few days.

I wish I had more definitive answers for you. But the data we’ve gotten so far is inconsistent and comes from a weird group of pollsters, several of which had shown outlier-ish results in one direction or the other before the convention began. I think we can probably rule out Trump getting a huge, 8-point bounce or something like that, and I think we can probably rule out his getting no bounce at all, but beyond that, we’re just going to have to be patient.

In another sense, however, the story isn’t so complicated. Whereas June’s polls suggested a potential blowout for Clinton, July’s polls have shown a highly competitive race. We’ll see what August’s polls bring, after the Democrats have held their convention and the bounces have died down.

VIDEO: The atmosphere of gloom at Trump’s convention

July 22, 2016

Tim Kaine Wouldn’t Do Much To Help Clinton Win The Election

UPDATE (July 22, 9:30 p.m.): Hillary Clinton made it official Friday night, telling her supporters in a text message that she had chosen Tim Kaine to join her ticket.

If Hillary Clinton chooses Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia as her running mate, as betting markets and journalists suspect, then in some ways, it’s a dull story. Kaine has traditional credentials, having served as Virginia’s governor before joining the U.S. Senate. He’s young enough, at 58, that he could run for president himself in 2020 or 2024. He’s not especially liberal, but he’s no Blue Dog Democrat, either. He’s a white guy, although he speaks good Spanish. If Mike Pence is a “generic Republican,” then Kaine is a “generic Democrat.”

The difference is that Kaine comes from a swing state, whereas Donald Trump would likely lose Pence’s home state, Indiana, only in a national landslide. If you’re going to pick someone from a swing state, is Virginia among the better options? And how much difference does the vice presidential nominee really make in his or her home state?

Our previous research suggests that a vice presidential pick adds about 2 percentage points to his party’s margin in his home state. So, for instance, if Clinton would otherwise win Virginia by 3 percentage points, her margin would theoretically increase to 5 points with Kaine on the ticket. Not all VP bonuses are created equal, of course; there’s some evidence that VP nominees chosen from less populous states (for instance, Joe Biden of Delaware or Sarah Palin of Alaska) make more difference than those picked from larger ones. But Kaine seems like a fairly typical case: Virginia is a medium-size state, and Kaine’s approval ratings there are solid but not spectacular.

It actually takes quite a confluence of circumstances, though, for those 2 percentage points in one swing state to change the winner of the Electoral College. For Kaine to swing the election for Clinton, she’d have to be losing Virginia without him (otherwise he’d be superfluous) but not losing it by more than 2 percentage points (otherwise, he wouldn’t help enough). Likewise, she’d have to be losing the Electoral College without Virginia’s 13 electoral votes, but she’d need to have at least 257 from other states or Virginia wouldn’t make a big enough impact.1

What are the odds of all of that happening? About 1 chance in 140, according to our polls-only model, based on a set of simulations I ran early Friday afternoon. That translates into only about a 0.7 percent chance that a VP pick from Virginia would swing the election to Clinton.

Not very impressive, right? Actually, it’s pretty good as far as these things go. A home-state VP pick would make more of an impact in Florida (where it would increase Clinton’s chances of winning the Electoral College by 1.8 percentage points), Ohio (1.3 points), Pennsylvania (1.1 points) or North Carolina (0.8 points). But Virginia is fifth on the list.

HOME STATE OF VP NOMINEEPERCENTAGE POINT CHANGE IN CHANCE OF WINNING ELECTORAL COLLEGEFlorida+1.8Ohio+1.3Pennsylvania+1.1North Carolina+0.8Virginia+0.7Michigan+0.4Iowa+0.4Colorado+0.4Minnesota+0.4Nevada+0.3Arizona+0.3Wisconsin+0.3Georgia+0.3Where would a running mate make the biggest impact for Clinton?Calculations are derived from FiveThirtyEight’s polls-only model and assume that the running mate would add a net of 2 percentage points to Clinton’s margin in his or her home state.

I’ve seen some griping that Kaine is a poor pick because Clinton ought to be able to win Virginia without him. In theory, that makes sense. Virginia’s demographics don’t seem very Trumpian. And mathematically, you stand to gain more from a VP pick in a state that’s slightly below-average for you than one that’s slightly above-average. But based on the polls, Clinton is vulnerable in Virginia. She leads there by only 2.6 percentage points in the polls-only model as of this afternoon, almost exactly matching her 2.5-point lead nationally.

Of course, a 0.7 percent increase in your chances of winning the Electoral College wouldn’t be worth it if your VP pick caused you problems in other respects. Presidential candidates seem to realize this, which is why there have been running mates from non-competitive states such as Delaware and Wyoming in recent years. But elections are won on the margins, and Clinton would be marginally better off with Kaine’s help in Virginia than without it.

Donald Trump Goes ‘All-In.’ How Will Clinton Respond?

Check out all our dispatches from the GOP convention here .

CLEVELAND — No matter what happens between now and the election on Nov. 8, Donald Trump’s dark and defiant acceptance speech on Thursday will probably be remembered as a pivotal moment in American political history. If Trump wins the election — an increasing possibility based on recent polls — the speech will serve as proof that he did so as an explicitly nationalist and populist candidate, having stirred up support in a country that has historically resisted such movements. If Trump loses to Hillary Clinton, especially by a wide margin, the speech will probably be seen as an historic debacle, the hallmark of a convention that went wrong from start to finish. Either way, the Republican Party might never be the same.

Trump delivered a long and loud address that violated most of the normal rules of acceptance speeches. The speech, and the Republican convention overall, made only perfunctory efforts to appeal to voters who weren’t already aboard the Trump train. It had no magnanimous gestures to Trump’s vanquished Republican rivals. It contained a fair bit of bragging, but not much autobiographical detail. It contained no laundry list of policy positions. Most strikingly, it was unrelentingly pessimistic, whereas acceptance speeches usually aim to soften the blow.

But Trump has broken a lot of rules and gotten away with it, and it will be a few days before we’ll have a sense of Trump’s convention bounce and a few weeks before we can reliably say how the conventions have affected the election overall. Given what Trump accomplished in the primaries, it’s probably prudent to avoid making too many assumptions in the meantime.

Related:July 21, 2016

How Should Trump Respond To The Cruz Craziness?

In this week’s politics chat, we run through the campaign developments that are likely to transpire in the next few days. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): We’re conducting our weekly politics chat a little late this week, and from Cleveland! And we’re going to do something a little different in terms of topic today. Usually, we like to focus on a single overriding question. But today, let’s talk about the next 48 to 72 hours, which seem likely to be chock-full of news and intrigue. We’ll talk about the aftermath of Ted Cruz’s defiant non-endorsement of Donald Trump, what Trump needs to do in his speech tonight, and the Hillary Clinton VP announcement, which may come very soon after Trump leaves the podium.

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): In the next 48 to 72 hours, I hope to not get any more sunburned than I already am. But also, I hope Cruz keeps being disruptive. It makes the hours fly by.

micah: Topic No. 1: Cruz got booed on Wednesday night for telling people to “vote your conscience” and not endorsing Trump. Did Cruz ruin Trump’s convention? Even if he did, does it matter?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): Having major Dana Carvey flashbacks right now:

clare.malone: I’m not sure whether or not he ruined Trump’s convention. I think the people in the convention hall were riled up by the Cruz speech and thought it was poor form. But what about the people watching from home? Did they think it was a little rude for Trump to butt in (when he came out at the end of the speech)? Did Trump ruin his own convention?

harry (Harry Enten, senior political writer): Can I just point out how ridiculous this whole thing is? First, the Trump campaign knew Cruz wouldn’t endorse. They let him speak in prime time anyway. Second, it would have been a smaller story — à la Jerry Brown not endorsing Bill Clinton in 1992 — but Trump couldn’t take the insult. The crowd starts booing Cruz, and then Trump enters almost as if this was the WWE. So he let Cruz speak and then ensured the media would play up the discord within the party.

natesilver: Let’s not get too cute about this one. Trump basically got humiliated on national television. That’s not how these things are supposed to go. I’m still a little bit in shock.

clare.malone: Totally … but he did know it was coming! It was in the pre-released remarks!

natesilver: Ehh, that’s a bit more complicated. There were two points in the speech where it would have been natural for Cruz to endorse Trump. Once early on, after he congratulated Trump. And then once about three-fourths of the way through the speech, when he talked about voting up and down the ballot for candidates who support freedom. In each case, he ad-libbed an additional line — acknowledging the enthusiasm of the New York delegation was ad-libbed — and drew out the pregnant pause for effect.

So a lot DID change from the remarks as prepared to the remarks as delivered. Even if Cruz hadn’t ad-libbed at all, it would have changed, because the way he delivered the lines drew much more attention to them and made them much more troll-ish.

micah: But the not-endorsing part didn’t change.

natesilver: Well, a lot of people haven’t endorsed Trump. And you don’t necessarily notice, because they’ll just plow right through with whatever platitudes they have.

harry: But that’s the thing — the delegates booed him. The delegates played it up. Then Trump comes in and plays it up more. What were they thinking?

clare.malone: They were thinking “theater.”

natesilver: Well, yeah, I’m not arguing that Manafort et al. did a great job. They seemed to be raising expectations throughout the day — maybe there would be an endorsement? — instead of managing them.

But it was also something you could teach in a rhetoric class — about the difference between a speech as written and a speech as presented.

clare.malone: I think it was foolhardy to expect that a guy like Cruz would be a sure bet to endorse — they had to know this was a possibility, and while I take your point, Nate, about the delivery, I still think that Trump relished the idea of going out there and stepping on Cruz’s toes. Yes, he was getting embarrassed, but he was going to counter-punch — his favorite thing, as we all know.

harry: I get that a speech might be different in text than in person. I get that there was a small chance he would endorse. But you don’t have to even take the risk by letting Cruz speak, and if you’re Trump, you certainly don’t need to enter.

clare.malone: I’m more interested in the people Cruz was talking to, though. Not the theater, ultimately

micah: Right, so let’s take a step back: Does it matter? Do Cruz’s voters stay with him?

natesilver: Most of Cruz’s voters were already with Trump. The Cruz voters who aren’t already with Trump might stay away from Trump instead of coming around, I suppose. But I think that’s slightly too literal a way to think about it. Conventions, and this convention in particular, are supposed to be displays of rallying around the nominee. This was the complete opposite of that, in a way that we haven’t seen at a lot of modern conventions. Folks at home might say, “These guys don’t have their shit together.” Donors might waver. People might pick up the negative buzz in the media, even if they didn’t watch the convention live. Trump might overreact and compound his problems. There are a lot of reasons why something like this can be bad news.

clare.malone: Yes, I think it does matter in the long run. I think a few people might be pissed off with him this year, sure, but ultimately, Cruz’s stick-to-itiveness is what his supporters like about him. I think he might try to use this as basically an Obama 2004 convention-type thing — look at this moment where I made a splash amid all the craziness. Because you can bet your sweet bippy that Cruz is going to run in 2020 whether or not Trump wins. He’s going to try to gather all the movement conservatives to his bosom again and tell them things will be different this time. Same thing works if Clinton wins.

harry: You ever have that perfect piece of food? You don’t know exactly what makes it great. You just know it’s good. I think of conventions like that. I don’t know if there’s a particular thing that makes one convention great and another bad. I think it’s a cumulative effect. And the stuff that happened with Cruz, the stuff that happened with Melania Trump, those things combined don’t help. As for Cruz’s future, we’re a long way from 2020. How his speech is viewed may have a lot to do with how Trump does in the fall.

natesilver: Yeah, and this is getting to be one of the conventions where they sat us 30 minutes late, and then the waiter forgot my drink order, and then when the main course finally came, there was a cockroach in it.

clare.malone: Or good conventions are like how the Supreme Court described hard-core porn: You know it when you see it.

Related:Donald Trump’s Convention Is Flirting With Disaster

We’ll be reporting from Cleveland all week and live-blogging each night. Check out all our dispatches from the GOP convention here .

Welcome, class, to Conventions 101. If you’re looking for Conventions 201, you’re in the wrong place; please see Professor John Sides down the hallway. And put those cellphones away, please. We’ll get to the drama created by Ted Cruz on Wednesday night in a moment, but let’s start with the basics. For instance, as far as we’re concerned, conventions serve two major functions:

Conventions serve to unify the party. Conventions, literally speaking, are party meetings. At its convention, a party nominates candidates for president and vice president, along with taking care of other party business, such as establishing rules for future nominations.Conventions are showcases for the presidential ticket. All the major broadcast and cable networks cover the conventions extensively, giving parties the equivalent of hundreds of millions of dollars in media exposure. In contrast to other sorts of political events, the media generally lets the parties set the program, and make their case to the American public in a relatively uninterrupted way. It’s a unique, once-per-cycle opportunity.Put another way, conventions are both the official end of the nomination process and the unofficial beginning of the general election process. In the modern political era, nominations are usually decided well ahead of the conventions, so they can come to resemble extended infomercials instead.

Still, these functions can sometimes come into conflict. If you watch only the prime-time coverage of conventions, the parties generally put on a good show. But at odd hours, there can be disputes on the convention floor. Or the party will put on speakers who present red meat to the party faithful, or who fulfill obligations to party constituencies, that it wouldn’t necessarily want swing voters to see.

But modern conventions are generally successful events. They almost always produce polling “bounces” in favor of the party that just held them. These bounces can be short-lived and aren’t always predictive. Still, some part of the convention bounce usually sticks, and polls taken a few weeks after the conventions are generally much more accurate than those taken a few weeks beforehand.

At a minimum, the parties almost always succeed at converting some undecided voters, who are leaning toward the nominee but who aren’t yet fully committed, into their column. So Hillary Clinton wants to persuade straggling Bernie Sanders supporters (and there are still quite a few of them) to join her cause, and Donald Trump wants to do the same for supporters of Cruz and other Republican candidates. Ideally, they’ll also bring some swing voters along. But if the nominees can’t achieve some modicum of party unity, the convention is a potential disaster.

So from a Conventions 101 standpoint, what happened in Cleveland on Wednesday night was a potential disaster for Trump and the Republicans. Cruz, the second-place finisher in the primaries, conspicuously refused to endorse Trump, and left the stage to a chorus of boos. An unusually large number of Republicans have also declined to endorse Trump, including Ohio Gov. John Kasich, who isn’t appearing at the convention even though his state is hosting it. But those defections might be forgotten about for a few days, provided that the party put on its best face in Cleveland. Cruz’s refusal to endorse Trump, however, which he seemed to draw out for emphasis to embarrass Trump, took place at center stage. It was bad from both a uniting-the-party standpoint and from a showcasing-the-ticket standpoint. It was among the most dramatic events that we’ve seen at a convention in recent years.

Related:Nate Silver's Blog

- Nate Silver's profile

- 730 followers