Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 6

October 11, 2024

Marcus and Me

“And what is good, Phaedrus,

And what is not good—

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?”

Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

I will not hide my biases and concerns. With a month to go before our Consequential Presidential Election, I look at our candidates and I wonder—as many of you wonder—how one of them could be be so utterly bereft of compassion, of empathy, of any kind of moral scruple? How is it possible to live on this planet for 78 years, caring about no one and nothing beyond your own appetite for attention, money, sex, and power? It bothers me when I look at someone like this who is a mere citizen, but it really worries me when I’m looking at a presidential candidate.

How can millions of people see Donald Trump as the Greatest Good for this nation, when his path to power requires him to set people against each other in terminal, tribal warfare, and when his focus is so relentlessly and persistently on what the world owes him, personally?

Is he just a narcissistic sociopath, and it’s all mere pathology? Or is he, in some ways, the apotheosis of the Baby Boom Generation, the Me Generation(s), the belief that “self-actualization” is more important than faith, family, friends, customers, country, the environment…anything outside of Self?

“Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” Or, you know…whatever.

We’re doing something wrong, people.

Tom Nichols has an important piece in The Atlantic about George Washington: the kind of man and leader he was, and why he mattered so much at a critical time in our young country’s history. It’s easy, perhaps, to do a hit job on Donald Trump by comparing him to the Father of Our Country. But Nichols’ deep dive into Washington, the man, is instructive, because it raises questions about the idea of character and where it comes from.

George Washington did not emerge from the womb as a moral and principled man, any more than he was born knowing how to lead an army. He learned those things, as we all do. He was raised quite deliberately to believe in public service and in private restraint. Those were qualities—virtues—deemed important and included in his formal education.

Thomas Ricks has a fascinating book about the schooling of young Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison. The four First Presidents were raised and educated in very different colonies, in very different social classes, in very different families. But they all learned some of the same things. Whether they learned at home or in a schoolhouse, their early education was steeped in antiquity. Each of the four First Presidents was required to learn Latin so that they could read contemporaneous accounts of life, war, and politics in the Roman republic and empire. Moral education came from the family and the church, of course, but it also came from ancient philosophers. Much of that philosophy centered on the Stoics. This is not surprising, because the four pillars of Stoicism eventually became the four cardinal virtues of Christianity, thanks, in part, to Thomas Aquinas.

In the minds of those 17th and 18th century generations, progress was real and linear and inexorable: the Greek world led to the Roman world, which led to the Christian World, which led to this New World—and each world taught and informed the one that followed, to enhance and perfect it. It’s not surprising that, in his insistence on retiring from the presidency and returning to his farm, George Washington was compared to Cincinnatus. He was raised, to some extent, to be a Roman statesman.

Stoicism is big, these days. You can even sign up for a daily newsletter of stoic (or allegedly stoic) wisdom. Everyone’s favorite exemplar of those old ways is Marcus Aurelius, who was as close to a Philosopher King as most of us know. His Meditations are easier to read than most books of philosophy—probably because they were written as journal entries and personal reminders, not as treatises to be taught by professors. Even if you’ve never read the book, you can find countless pithy quotes in every corner of the Internet, many of them adorned with his picture.

Of course, as with all quotes on the Internet, you need to be careful and do a little due diligence before you share things. One of my favorite quotes turns out to be from Tolstoy, not Marcus ("The object of life is not to be on the side of the majority, but to escape finding oneself in the ranks of the insane"). It’s still a great sentiment.

There are so many fake quotes from Marcus Aurelius that a professor had to make a YouTube video about them. So, in the spirit of the Romans: caveat emptor.

Marcus Aurelius first came to my attention many years ago, when the Indigo Girls released the song, “Galileo,” from their album, Rites of Passage. Someone—I’ve forgotten who—told me that he thought two lines from the chorus (“How long ‘til my soul gets it right? / Can any human being ever reach that kind of light?”) were either a sly reference to, or simply inspired by, the philosophy of the Roman emperor.

Intrigued, I went out to a book store and got a copy of the Meditations. At the time, all I could find was a fairly stuffy, formal, Victorian-era translation, which made connecting the dots a little complicated. But when you look at more modern translation, you can see what that someone-I’ve-forgotten was thinking:

To my soul:

Are you ever going to achieve goodness? Ever going to be simple, whole, and naked—as plain to see as the body that contains you? Know what an affectionate and loving disposition would feel like? Ever be fulfilled, ever stop desiring—lusting and longing for people and things to enjoy? Or for more time to enjoy them?

Meditations, 10,1. Translated by Gregory Hays

When I was growing up, I thought Stoicism (uppercase or lowercase) meant being emotionless—repressing all feelings; suffering in silence. Basic, dumb, old-fashioned, 1950s-style masculinity. Or that it was nihilistic—telling us to accept whatever comes, because you can’t change anything in the world. But it’s none of those things.

Stoicism asks you to reflect on the things of the world that you can affect and the things you can’t, and to put your energy and attention only on the former. It’s not about surrender; it’s very action-oriented (as any philosophy attractive to an emperor would have to be). It just cautions you to be realistic about causes and effects—realistic about what you can influence and change. To the Stoics, other people’s actions are outside of your control, but your responses to those actions are yours entirely. No one can actually hurt you, they said; you allow yourself to be hurt. You have the power to choose. What other people do is of little concern to you, in the end. It’s what you do that matters.

It’s a great rebuke to the culture of grievance that so many of us seem to be soaked in, these days, where we spend our hours rehearsing all of the wrongs that have been done to us and whining about how little we can do with our lives because of it, other than plotting revenge. To Marcus, the best revenge is simply refusing to be like the people who wronged us.

I love that Big Idea: what others did to us is of little concern; it’s what we do that matters. It urges us to action, not surrender. It tells us to own every bit of our lives. It tells us that being broken-hearted is all right, sometimes—important, even—but that it’s our choice to let our hearts be broken. And that it’s on us to decide what to do next. The sentiment reminds me of this moment from The Lord of the Rings which resonated with so many people when the movies came out in the years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11:

The Stoics were pretty realistic about mortality, too. They encouraged us to keep death somewhere in our peripheral vision at all times, as a reminder that “you could leave this life at any moment.” To be gloomy and depressed about life? No—to relish it and make the most of it. To “enjoy every sandwich,” as Warren Zevon put it, when he knew his last ride was coming to pick him up.

The Greeks and Romans of various philosophical schools spent a lot of time wondering what ideas like “goodness” and “happiness” meant, and what the best way to achieve those things might be. In a world where we are constantly bombarded with enticements to buy and take and use—to entertain and enjoy ourselves so that we can be truly happy—those ancient questions remain pretty important. What is our real purpose here on earth? Is it better to pursue being happy or being good? Is it enough to enjoy every sandwich?

Aristotle (not a Stoic) definitely thought there was more to life than the sandwich. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he said:

Happiness is not found in amusement; for it would be absurd if the end were amusement, and our lifelong efforts and sufferings aimed at amusing ourselves.

You remember Aristotle:

Amusement and comfort were fine, he believed. We need those things in order to live our lives, but they’re not the ultimate aim of life. As he said, “He is happy who lives in accordance with complete virtue.” Virtue, to him, was the goal. And virtue was not simply a collection of feelings; it was a set of actions. Public actions. Happiness meant having the things that enabled you to do good in the world.

Do we still believe that the happy life is one of virtue and contribution to society? If so, where in our modern world do we teach that? The message of modern Consumer Capitalism seems to be: you owe nothing to anyone but yourself; buy more stuff and have more fun. And it’s a pretty relentless message.

I think most parents would reject the idea that TAKING and USING were the highest values in the world, and would want something different getting through to their children as character education. But where does that something else come from? Does the task fall entirely on the family? Should religion be expected to carry the burden? What if you’re not part of a religious family or community? Should it be part of the school curriculum? Whose responsibility is moral and civic education?

There are people who sincerely believe that without the threat of divine punishment, people cannot be expected to be good, but I know plenty of atheists and agnostics who have found a way to restrain themselves from murderous rampages. If you are part of a religious tradition that teaches moral principles and civic virtues, fantastic. But if you’re not…what are those other avenues of learning?

And I do mean civic virtues here, not simply “civics,” the class where we learn how a bill becomes a law. Where do we learn the habits of heart and mind, and the public behaviors, that enable us to live together in a democratic society?

Look, I’m old. I grew up with stuff like this on TV:

The question matters to me as a citizen and a father, of course, but also as an educator. Previous generations saw moral and civic education as part of the role of the school. That’s not universally accepted anymore, because public schools have lost public trust in some areas, and we’ve also lost confidence and consensus around what we should be telling our kids.

I’ve seen a drive lately to bring back the idea of “Classical Education.” This exists mostly within religiously and politically conservative circles. You can find a variety of actors and agendas in this space, mostly in the charter school movement. You may find some of them innocuous and even inspiring; you may find others of them leaning towards White Supremacy and American Nativism. But if you’re on the Left, or even in the political center, it’s worth looking at what some of them are doing, and asking yourself whether any of it is speaking to something of value that, perhaps, we’ve lost.

The Great Hearts network of schools, currently in Arizona and Texas, publishes this as their purpose and philosophy:

Liberal education consists of cognitive, emotional, and moral education—thinking deeply, loving noble things, and living well together. We believe, with Plato, that the highest goal of education is to become good, intellectually and morally.

“Thinking deeply, loving noble things, and living well together.” How much of that is going on in our public schools today? Do our schools think it is their mission to make their students “good, intellectually and morally?” Some try. But is there agreement within their communities about what that would entail? Is there agreement between communities?

Dig into the Great Hearts English curriculum, and you’ll find their reading list to be Whiter and older and more male than in many public schools today. Dig into their history curriculum, and you’ll find far more focus on American history than world history, and not much of anything about the non-Western world. Progressive in tone? Hardly. Multi-cultural in breadth? No. It’s not what I would have wanted my kids to study in school—or, at least, not solely that.

But where they may not go broad, they do go deep. Their “Humane Letters” course, required for all high school students, is a hardcore seminar filled with genuinely complex, meaty texts and extensive Socratic dialogues designed to unpack the meanings and purposes of those “works of prose, fiction, political theory, epic poetry, philosophy, autobiography, drama, and selections from Jewish and Christian scriptures.”

Do I wish that every high school senior had access to that kind of a class? I do.

The curricular throwback to the 1950s might not be your family’s cup of tea. It’s not mine. But why should that be the only approach? Is “thinking deeply, loving noble things, and living well together” only a value on the political and religious Right, or should these things be the true aim of schooling?

Do schools have a role in making young people “good?” Would we even be comfortable letting them play such a role? And what shared philosophy or worldview would guide that shaping-of-good-people?

Donald Trump is the extreme example of what you get when you raise a child without ethics, morals, or focus on the good of the group. He is a raging, untamed Id, out for himself, only and always. That’s his family’s fault, and the fault of a mental disorder. But at some point, education also let him down.

What’s the point in learning how to read and write and do sums, if you don’t also learn how to live a happy life, as Aristotle defined it: a life among people, a life that teaches and enables and empowers you do good things for and with those people—to make a world together that’s worth living in?

I know, I know—the people who hoot and cheer for those who make us hate each other—who are okay with burning down the country as long as they can rule the ashes—they’re not breaking my heart; I’m allowing my heart to be broken. That’s on me. But Joe Biden talked a lot in 2020 about needing to heal the soul of America, and a lot of us agreed with him. So, how long ‘til our souls get it right?

October 5, 2024

The Last Mile Problem

The Man in the Van

The Man in the VanIn logistics and communications industries, there’s a thing known as the “last mile” problem. It relates to the challenges of taking the final step of delivery of goods and services to a customer.

In logistics, all of the careful packaging and shipping and warehousing and tracking of goods can fall apart when a box is put into the hands of some guy driving a van, who has to hand-deliver it to someone’s doorstep. Oversight can fall apart during that last mile. A lot of human error or slovenliness or greed or disinterest can come into play—from the van driver to a neighborhood thief to a homeowner who leaves a package out in the rain. The last mile is where systems surrender to trust.

In communications, the “last mile” involves the final step of connecting a network to an individual user—historically, the running of cable from a central line, managed and maintained by a fleet of workers in trucks, into and through your house, where God-knows-what might happen to it. The cable comes through your wall, and the electric company has no control over what your cat or your baby is going to do with it.

At some point, systems have to surrender to trust because the end users are not employees and they are not mere receivers; they are users—and the way in which they use a product or a service can be idiosyncratic, or ill-advised, or just dumb. As the purchasers those of goods and services, they have every right to be as crazy or stupid about their use as they want to be. They will do what they will do—not, perhaps, what we would wish them to do.

Life in the Egg CrateWe have our own last mile problem in the world of education. Creators of programs and products often refer to it as “fidelity of implementation.” It’s what doctors would call, “usage as prescribed.” We intend for a product to be used in a certain way, because we have some belief (or evidence) that this way-of-using is meaningful and effective. And…then what happens?

I worked for an education technology company that sold a reading program that had decades of solid effectiveness research behind it. We had data from over two million students showing that, when used as recommended, the product could accelerate Lexile (or reading level) scores three to four times greater than expected growth over the course of a school year. That’s a significant and meaningful level of growth for students who are lagging behind their peers. This acceleration rate held true across all demographic sub-groups; no matter what kind of student you were, you could improve and catch up and achieve. It was the most impressive efficacy research I had ever seen, for any company I had worked for. It could change lives.

However. As with any product like this (or any medicine, to go back to the doctor analogy) using-differently-than-directed may lead to sub-optimal results. In our research, we could see that when students didn’t read at least one article in the program each week, every week, or when they didn’t put some effort into answering questions correctly, the growth rates shrank. Some students used the product once a month. Some used it twice a year. Some raced through, selecting “C” for every answer, because they didn’t care. Those students saw no growth at all.

Anyone want to bet on many students used the product haphazardly or occasionally, versus how many used it consistently and to good effect? If you’re a gloomy, cynical pessimist, you’ll win this bet. About 10% of our students were using the program as recommended and getting the maximum possible growth out of it. A majority of users were barely “users” at all. Most of the students did little with the program and got little out of it. Implementation without intentionality made it, to be quite blunt, a waste of time and money.

My former company is hardly the only one dealing with this kind of discrepancy. Peter Greene cites a study in a recent blog post, showing even worse fidelity numbers for some very well-known products—one as low as 4.7%. That’s right—not even five students out of a hundred were getting the real benefit of the program the school had paid for. And this is a program that is in many American schools.

If a school is going to purchase something that can help students, whether it’s a product for classroom use or a training in a new instructional approach, the teachers need to implement that something with a sense of intention and purpose if it’s going to have any hope of being worth the investment. I like the word “intention” much better than “fidelity.”

But, as Greene puts it:

If you hand me a tool that has been made so difficult or unappealing to use that 95% of the “users” say, “No, thanks,” I’m going to blame your tool design.

Teachers have their own intentions and purposes and priorities. They owe publishers and software companies no “fidelity.” If they don’t like a product or a new instructional strategy, they’re not going to use it. If they find the kids don’t like it, they’ll stop forcing it on them. Teachers don’t care how much their administrators may have paid for the thing; it’s not coming out of their salaries.

The last mile problem we have in education is old and baked into the structure of how we do schooling. For decades, we treated schools like shopping malls, where every room was an entity unto itself, run independently and with little accountability to any central authority. Some researchers have called it an “egg crate,” approach: lots of little eggs, each in its own little protective cocoon. The more we have tried to standardize teaching, the more accountability measures and mandates and metrics have been forced upon our teachers, the less attractive the profession has become to many of them. Mission-driven and creative people don’t go into teaching in order to read a script or follow daily commands. Many find ways to ignore or work around those commands…or they leave the profession.

So, what can we do? How can those of us who make things for use in schools address this last mile problem that undermines the use of what we create?

Well, we’ve tried to provide initial and ongoing training. We’ve tried to bake in as much guidance and help as possible, to make up-front training less and less necessary. We’ve tried to do user research and user interviews to make sure our products are not “difficult or unappealing to use,” as Greene puts it.

Are there garbage products on the market? Of course there are—in every market. Caveat emptor, administrators: do your due diligence and don’t foist crap on your teachers and kids. Some stuff is just bad. Some stuff is well-intentioned but poorly designed or built. That’s not particularly interesting to me.

The challenges faced by good actors, making good product, trying to make a real difference—that’s what keeps me up at night—because I’ve been around for a while, and I know there are a lot of smart and dedicated folks working in this space. A lot. And they spend a lot of time and effort trying to do good things for students, whether it’s creating new products or improving existing ones. And if even the good stuff—if even the best stuff—has only a 10% rate of thoughtful, intentional implementation, then what hope is there?

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même choseAdoption of any new idea or practice requires a change in habits, and change is something we don’t manage well in schools. To be honest, it’s not something we manage well anywhere.

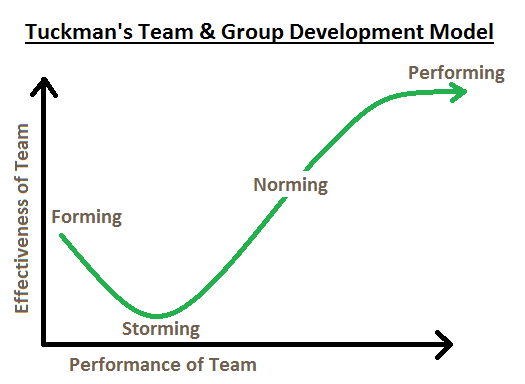

There are reams of books and articles about the challenges of driving organizational change. Since at least 1965, we’ve had a good and helpful model, developed by Bruce Tuckman. You may have heard the terminology of “norming, storming, forming, and performing,” or seen a graph that looks like this:

What does it tell us? It tells us that whenever a significant change is adopted, initial excitement gives way to the hard part of learning: the frustration and lower performance that come from trying to do something new. As you become more adept and comfortable, you become happier and more successful. Eventually, if the change was a wise one, you are more effective and efficient than you were before you started—and you’re feeling better about yourself and the team, as well. Everybody wins.

What actually happens, though, more often than not, is that when things start to fall apart, people bitch and moan and complain, and leadership usually gives in (or goes on to another job), abandoning the change effort and resetting the graph back to the start. So, what you really get is this cycle: initial excitement; frustration of learning; fear of failure; abandonment; let’s try the next new thing. Round and round it goes, with millions of dollars being spent with every reset, and no one making any real improvement.

Should we blame the people bitching and moaning and complaining? We should not. As Chip and Dan Heath put it, in their book, Switch, what looks like resistance may simply be exhaustion, People have hard jobs, and they didn’t ask to have their cheese moved, as another book puts it. They’re just trying to get through the day.

Change requires a lot of effort and a lot of time. Why engage with it if you know, deep down, that it’s going to be abandoned, just like the last Big Idea was? Change demands vulnerability: nobody likes feeling stupid and clumsy, and you always feel stupid and clumsy when trying something new. If you know that, “this, too, shall pass,” why even try? Why not just keep your head down and wait for the wave to pass you by?

No, don’t blame the troops: blame the leader. Who is making the case for this change? Who is convincing the troops that the old way isn’t good enough anymore? Who is convincing them that the gains will be worth the pains? Who is shepherding the flock to these new and better grazing fields?

If leaders really want to see change, they need to align their people’s intentions with their own. You can’t actually mandate a change; you have to manage it. You have to make the case for it. You have to dig in and show them that it’s important—that you won’t abandon it as soon as things get difficult. You have to be willing to burn the boats and say, “we’re not going back.” You have to be willing to take it to the last mile.

Help is on the wayFor those of us who create educational products with a sense of mission and purpose—who don’t work in classrooms but who want to help effect change in the world—the challenge we face—the great task—is keeping purpose and intentionality alive from start to finish: from designers to developers, from developers to marketing and sales teams, from the sales rep to the superintendent, and then to keep going—keep going—to find ways to help our superintendents carry the message, complete and with clarity, to their administrative team, and then to the classroom teacher, and then to each, individual student, so that the fire that lights us, that we use to light our products or programs, carries all the way to the hearts and minds of the students we’re trying to help, like the chain of torches that sends messages from mountaintop to mountaintop in Middle Earth.

It’s hard. You can tell how hard it is by how rarely it works. But in the end, it doesn't really matter what should be done or even what can be done. All that matters is what will be done.

September 27, 2024

Live Not in Nonsense

The World That Was

The World That WasBack in the 20th century, when I was a young person, there were clearly defined and limited ways for me to learn about something:

Ask a grown-up

Read a book

Watch TV / listen to the radio

Go to the library

Information resided in certain brains and certain places, and you had to go to them to get it. Information existed inside a gated fortress and it was doled out at the discretion of the people who manned the gates. If you asked nicely, you could get what you wanted—or, at least, what they decided you needed. We trusted the experts to be smarter than us and to guard and dispense the information responsibly.

From our modern vantage point, we can see the drawbacks and limitations of this set-up. But it’s what we had, so we didn’t question it much. “What if I know more than the experts?” would have been thought of as a ridiculous question. “What if they’re lying to us?” was laughed at in polite society, although, after Vietnam and Watergate, the people asking that question started getting a little more respect.

Whether we trusted the experts or doubted their intentions, they were still the gatekeepers and the fortress was simply the Way Things Were.

And now? Where are we now?

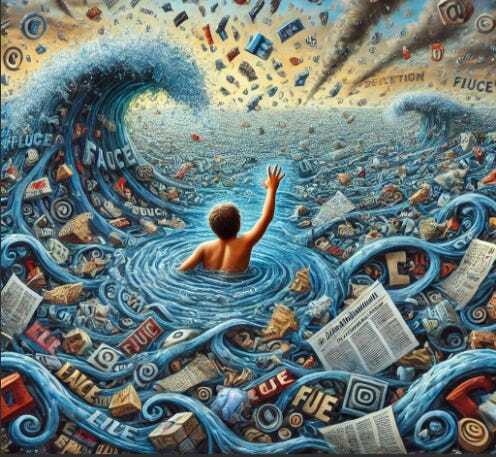

Here?

That’s what it feels like.

Without gates and gatekeepers, it’s a free-for-fall. It’s not just that anyone can access information; anyone can produce information. The gatekeepers weren’t just guards; they were creators. They had their hands on the means of production, and anyone outside the gates who tried to produce something—a book, a magazine, a TV show…well, you could tell it was amateur hour, cranked out in someone’s basement. There was no way to create and disseminate information at the same level as the experts. It reeked of crazy.

That’s obviously not the case now. Everything looks professional; everything looks well-made. You can’t tell from surface clues whether the source of information is a well-educated and well-intentioned person, or a complete loon. It’s hard to know if you’re eating protein, candy, or poison.

To switch metaphors: if we adults are drowning in lies, trivia, and nonsense that’s posing as genuine information, imagine what it’s like to be a kid. How can we help our students develop the skills they need to steer their ship of self to a safe harbor in this crazy world? We’ve been talking a lot about “soft skills” in recent years, but keeping one’s head above the swirling waters of nonsense feels pretty hardcore to me.

The View From Here“Doing your own research” is not a brand-new idea, and it’s not a disreputable one. Taking power from gate-keepers and deciding things for ourselves was a hallmark of the Reformation and the Enlightenment. It’s not a coincidence that the the rise of ideas about democratic self-rule coincided with the rise of science as a serious discipline. If you knew how to read, you could learn things for yourself (thank you, printing press). If you subjected new ideas to careful testing, you could figure out what was true about the physical world (thank you, scientific method). Franklin and Jefferson were amateur scientists, among all the other things they were. It affected the way they thought about the world. Early American poets railed against the idea of Old World authority. We overthrew the idea of Divine Right for both kings and traditions. The power was in our hands, every day, to learn and discover and decide and act. Revolutions are born of such paradigm shifts. Ours was.

The StakesThis book by Jonathan Rauch does a great job of tying the health of our democratic principles and culture to our ability to process information effectively and argue with each other productively. What he calls the “constitution of knowledge” is our system for synthesizing information collaboratively and turning disagreement into socially accepted truth. If we are constructing knowledge together as a society and taking democratic action based on that knowledge, it’s really important to keep lies and nonsense out of the system. A democracy can’t thrive in an ecosystem of lies. Good plants can’t grow in poisoned soil (yet another metaphor—sorry).

Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote an essay in 1974, while still in Soviet Union, called, “Live Not by Lies,” in which he talked about the challenges of survival and sanity in a world in which information was constantly withheld or distorted to control the populace. “The simplest and most accessible key to our self-neglected liberation,” he wrote, “lies right here: personal non-participation in lies. Though lies conceal everything, though lies embrace everything, we will be obstinate in this smallest of matters: Let them embrace everything, but not with any help from me.”

Vaclav Havel, trying to get through the same, post-Stalin malaise and misery in Communist Czechoslovakia, echoed Solzhenitsyn in his essay. “The Power of the Powerless,” and talked about the importance of “living in truth” refusing to participate in public lies.

These are Revolutions of One: not convincing a horde to storm the barricades, but making a barricade of your own mind—digging in and saying No.

This stuff matters. Once you know better, you can do better. Maybe you’re morally obligated to do better. But you have to know a lie is a lie in order to take that stand.

The ChallengeYou can tell how powerful this all is when you see hard some people work to take the power away from you, or at least muddle and confuse you so much that you give up the effort and let someone else tell you what to think. Hannah Arendt had their number:

Unfortunately, it’s easy to “flood the zone with shit,” as Steve Bannon put it, and use confusion to push people’s outrage button to get an emotional, rather than a rational, response. Our brains are happy to downshift from critical thinking to instinctive, primal reaction. Reasoning is hard, and our lazy brains would rather not do it unless absolutely necessary. This book does a nice job of helping us understand the various ways in which our cognitive biases and shortcuts cause us to “know what isn’t so.”

But the power remains in our hands, whether we use it well or not. We remain responsible for the decisions and actions we take, even if we’re under the spell of liars and loons.

The Road AheadAs educators, how can we help young people know better so that they can do better? By and large, our approach to instruction hasn’t changed much since I was in school, even though the information environment and our ability to know things has changed radically.

Think back to my four sources of information at the start of this post. How quaint! How ridiculous! Information is everywhere now. You don’t have to go anywhere. You don’t have to talk to anyone. You don’t even have to get out of bed. And if you don’t talk to a wise adult about what you’ve found, where you found it, and who produced it, you may end up walking around with some truly crazy ideas in your head.

This puts a huge amount of responsibility in the hands of children whose critical thinking skills are still being developed, and whose understanding of the world is still limited. When I was thirsty, I had to go to a designated place and ask for a cup of water. When today’s kids are thirsty, they stand in front of a firehose (sorry—I’ll stop now, I promise).

Here are four things we could work on with our students—especially our middle school and high school students—to help them navigate these treacherous waters:

Systems thinking. When we focus too much on discrete facts, everything ends up seeming of equal merit and importance. Each fact is a little rock, connected to nothing and meaning nothing beyond itself. That may make it easier to memorize things for a test, but it’s not useful learning—and it’s not a reflection of reality. The things of the world are deeply contextualized and connected and bound up in meaning. Events have causes and effects. History is made up of endless chains of causation—webs and networks, really, more than linear chains. Facts only matter to the extent that they help us understand larger systems. We need to help students see how information is connected. We need to help them build rich schema—big ideas and concepts that can hold the relevant information and connect the dots in meaningful ways. When you have schema like that, it’s easier to assess new information and decide whether it fits—whether it makes sense. As someone recently posted on social media: “Everything is a conspiracy theory when you don’t understand how anything works.”

How can we do this? The Understanding by Design framework and Concept-Based Curriculum can help teachers create more contextualized units of instruction, where discrete information is structured to drive towards a larger understanding.

Cognitive biases. As I mentioned earlier, our brains are lazy and take a variety of shortcuts to save on mental bandwidth. Sometimes the shortcuts are helpful (if they weren’t, we wouldn’t keep using them), but sometimes they’re dangerous. Sometimes they lead to things like stereotypes and racism. Being aware of how our minds work can help us catch ourselves when they’re not working well. These can be interesting things to learn about and engage with—especially if students can catch themselves and each other using them. Here’s a good resource from the Decision Lab.

Logical fallacies. Cognitive biases happen without our conscious intention. Logical fallacies are deliberate, bad-faith tricks used when making an argument. Teenagers can have endless fun hunting for examples of these techniques in advertisements, editorials, and speeches. Here’s a good resource from Purdue University

Credibility. If we are naturally inclined to seek out and privilege sources that agree with our position (and we are), and if authors use a variety of techniques, some slightly underhanded, to compel our assent (and they do), how can we help students assess the credibility of sources when they’re doing research? Here’s a handy resource, with a clever acronym, from the Robert F. Kennedy library. Acronyms are great—you could make a poster of it and have students practice the steps and compare results.

I know. It’s a lot. Here’s another option: just make use of this great, online course called, “Calling Bullshit,” assuming your school isn’t too squeamish about vocabulary. Or you could just use it yourself and then reframe it for your kids. The reading list alone is worth the visit.

September 20, 2024

Adventures in Professional Development

The State of Things

The State of ThingsAccording to TNTP’s 2015 report, “The Mirage,” the largest 50 school districts in the U.S. were (as of 2011-2012) devoting at least $8 billion annually to teacher professional development. More recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics seems to confirm this figure, showing that public schools spend about 1% of their annual budgets on professional development and related costs.

Despite this significant investment, TNTP’s study failed to discern any causal connection between the professional development efforts and other strategies being provided in their study schools, and any discernable teacher improvement. Some teachers in their study improved, while others (most of them) did not budge beyond their initial years of teaching. Induction programs and mentoring appeared to bring teachers up to a reasonably mediocre level of performance, a level at which most of them remained. Those who continued to grow seemed to do so for personal reasons disconnected from any efforts provided by the schools.

I am not surprised.

My Before TimeI don’t remember having any formal professional development during my weird teaching career, although I must have. In my first job, at a very alternative high school in Atlanta, each of us pursued our own professional learning in our own way, or in individual consultation with the headmaster. I don’t think we had any group sessions as teachers, any more than we led group classes with kids.

Later, working for New York City Public Schools, I’m sure I had training sessions on this or that, but nothing that I’d call real “professional learning.” In my first school, the relations between the principal and the staff became so toxic and strained by late October that full faculty meetings were canceled for the rest of the year, replaced with quick “stand up” meetings in a hallway right before the opening bell rang. This allowed the principal to bark orders at us and then walk away, which was all he really wanted.

In my second school, a magnet school attempting to be more progressive, we did have faculty meetings—long ones, every week: so long that they violated our union contract, a fact which we had to agree to and sign off on before taking the job. But I don’t remember what we talked about at any of these meetings, apart from the day when we haggled over the structure of the new report card and what the categories on the checklist section should be. I remember this incident only because I made a nuisance of myself, insisting that having “Improving” as the lowest possible rubric score was not honest. Some of my kids are not improving, I said. Do we think they’ll simply disappear if we don’t have a phrase to describe them?

I was not well liked that day.

Becoming The Guy in the SuitWhen I left the classroom and started doing curriculum writing at Kaplan’s fledgling K12 division in the early days of No Child Left Behind, I was recruited to help lead professional development sessions to support our new test-prep products. The trainer on staff had a good background in mathematics and was happy to explain and demonstrate the math courses, but he needed a partner to lead the English side of things, and since I was the primary writer of those courses, I seemed like the natural choice. Plus, I was too new and stupid to say No.

How ancient am I? My first year of presentations was accompanied by overhead transparencies using these delightful, classic, clip-art characters…

…broadcast using these delightful, classic projection devices:

I would trot out to various schools with my folder of transparencies, careful to keep them in the correct order, and then go through my little talk about test-taking strategies, gently placing one image after another on the device, while yammering for about ninety minutes.

Did teachers love these presentations? Reader, they did not.

First of all, they didn’t want to be there. Teachers never want to be there. They have papers to grade and lessons to plan and, if time allows, families to raise and lives to live. There is nothing less engaging than being forced into a classroom or auditorium after a full day of teaching to watch some guy in a suit talk about topics you didn’t ask to learn about, don’t care about, and suspect the presenter may not be an expert on.

Secondly, of all the things to spend your theoretically spare time learning, how to help students take tests was pretty far down on most teachers’ lists. This was the early days of No Child Left Behind, and the world of annual, mandated, standardized tests was still new to many people. The teachers resented having to make time for the tests, and they really resented having to make time for practice tests and exhaustive strategy instruction to save the school the embarrassment of not making its Adequate Yearly Progress goals.

Because this world was so new, there were many teachers in my sessions who thought that, because I was teaching them about the structure and challenges of their state test, I must be the guy who wrote the test and, worse, the guy who decided that their dear children would have to take it. The first section of every session consisted of me trying to make common cause with the group: Hey, guys! We’re all in this together! Let’s help our kids succeed!

It did not go over well.

Neither did the idea of approaching tests strategically. There were many English teachers who resented the idea that students should be asked to read with blinders on, with a specific and highly transactional purpose. They didn’t seem to want to admit that while there were many reasons why people read things in life, few of them (sadly!) involved a deep and thoughtful appreciation of metaphor.

Had I been in their seats, I probably would have reacted exactly the same way.

From Training to LearningAs time went on, our work in test-preparation broadened to include basic skills review and then core curriculum development for large, urban school districts whose central office capacity had been hollowed out in budget cuts, and where new leaders had ridden into town on white horses, promising Big Change. We started working with districts on rewriting their core curriculum, providing pacing plans, unit guides, model lessons (daily lessons, in some ill-advised cases), and benchmark assessments. I helped develop and lead PD sessions on the curriculum, our backwards-designed approach, what constituted good “essential questions,” what it meant to unpack learning standards, and so on.

These were also not particularly well-received. No one loves a mandate, and people sent into a school to implement a mandate are never exactly seen as heroes. What the district leaders tended to ignore or overlook was the challenge of managing institutional change and cultivating a healthy culture of mutual accountability (things I developed workshops on, years later). They simply mandated things and expected people to comply. But teachers can be very effective at nodding their heads, saying “yes, sir” or “yes, ma’am,” and then closing their classroom doors and doing whatever the hell they want to do. Which is why teachers tend to outlast administrators. And why things tend not to change.

Later, with other organizations, I got to work with authors like Robert Marzano, Eric Jennings, Jay McTighe, and Baruti Kafele, designing online PD courses or producing PD videos. Later still, I got to design and lead workshops on the Common Core State Standards, and create a day-long program called “Teaching for the Stretch,” all about effective questioning techniques and helping students manipulate and “play with” their learning, instead of simply ingesting it and then vomiting it back up on assignments and tests. From the reception I received and the number of times I was asked to deliver these sessions, they seemed to be a lot more engaging and useful to teachers. They were certainly more fun to lead.

Some of what I talked about in that series of keynote addresses and workshops, I’ve rewritten in more narrative form and published here on Substack: here, here, and here.

Why It’s a MessProfessional Development is a tricky business. Schools often try to shove it into a day or two of mass, formal presentations, rather than supporting professional learning authentically throughout the year. Schools rarely let teachers drive and guide and organize their own learning—deciding on their behalf, paternalistically, what they need and should care about. That’s not a recipe for team happiness.

Another problem is that schools—and the companies providing PD services—rarely engage in any real analysis of the work’s effectiveness. At most, you tend to see single-page evaluations handed out at the end of a session, asking teachers to rate whether the AC was working, whether the snacks were good, and whether the presenters know what they were talking about. Schools rarely learn more than this very base level of “loved it/liked it/hated it,” which makes it very hard for them to know if they’re spending their PD dollars wisely.

In theory (or, as I try to stop myself from saying, “you would think…”), administrators would want to know whether teachers actually learned anything—and then, some time later, whether they put that learning to use—and then, some time later, whether those changes to practice led to improvements in student performance. There is even a system devised to measure and rate these levels of effectiveness.

I have never seen it put to use. Never once.

In my darker hours, I’ve sometimes felt as though administrators, teachers, and PD providers were all in cahoots together, engaged in a massive conspiracy to check off a requirement without demanding too much of each other: just sit there, be quiet, and don’t ask for too much, and it will all be over soon.

If you don’t rock the boat, everyone gets what they want. Everyone except the children, of course.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and TomorrowDo we need to rock the boat? Do we need to do better in supporting the professional learning and growth of our teacher corps? I mean, if no one’s really complaining, why worry?

Here’s one reason:

This year, in 2024, the National Education Association (NEA) is reporting that there are about 567,000 fewer educators in public schools compared to pre-pandemic levels. A recent Department of Education report puts the number of lost public education jobs just in the first year of the pandemic at 730,000, or 9% of the total. The shortage is particularly acute in subjects like math, science, special education, and bilingual education.

The shortage is expected to worsen if current trends continue. According to the NEA, more than half of our educators plan to leave the profession earlier than expected, due to burnout and stress exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

We’re losing our seasoned veterans and their depth and breadth of knowledge. We’re having trouble holding onto our new recruits and building them up into tomorrow’s veterans.

When I hear people talk about the problem, they talk about one thing only: money. Teacher pay. And that’s an element of the problem, for sure. But it’s not the only one. The physical conditions under which teachers work, the emotional strain of teaching, the emotional state of their students—all of these things seem to be getting worse. And if our teacher corps is getting younger and younger, they’re going to need some serious help—some ongoing coaching; some real, instructional support; some ways to learn and grow throughout their career. Something that works.

We need a bigger boat.

September 14, 2024

A Perfect Day in Piešťany

In January of 1993, facing my 30th birthday and a marriage and life I wasn’t happy in, I took a job teaching English conversation in a small town in the Republic of Slovakia, which had just recently emerged from years of Communist rule and had broken away from the Czech Republic to become an independent nation. I was part of a program called Education For Democracy, which placed teachers in the larger cities and smaller towns of both countries. Because I had a tiny bit of teaching experience, I ended up working alone in a very small town, where I could ruminate to my heart’s content, or discontent, and try to figure out my life.

One of my fellow teachers, who had been posted to a beautiful and historic spa town, arranged for a group trip and spa treatment in early March. What follows is what I wrote in my diary about the trip once I returned to my little, monastic cell, in my little, remote, village.

It’s interesting to look back at these notes scribbled half of a lifetime ago in an old notebook, trying to decipher my terrible handwriting and remember where my head and heart were. I can see now how much I was talking to myself without realizing it. Looking at the world around me and saying you and they (with naive and semi-informed confidence), I was trying to break through my own stubbornness and say what I needed to hear.

I heard it eventually. Somewhat imperfectly. I’m still a work in progress.

Piešťany, March 14: We woke up, ate bread and jam, drank coffee, and headed out to the Ensana Thermia Palace, where one of G____’s adult students, a doctor at spa Irma, arranged for a free “treatment” for us. The men and women split up. I was with M____ and his friend, T____, who had arrived that morning. We stripped and were paraded down to the Sulphur bath, which was big and domed and full of gargoyles. Then we showered and were marched to the mud bath, in another domed room. This was very odd: brown water with very slimy mud on the floor of the bath, that our feet oozed into and stirred up.

After 15 minutes of that, we showered again and were led into small cubicles, where we were wrapped, mummy-style, in heavy sheets, and left to sweat like pigs for a while. When that was over, we were led upstairs for our massages. I had never had a nude massage before. It was a little disconcerting, but I got over it and just relaxed. After that, another shower and it was over. We stood, talking to a spa worker for a while, in broken Slovak, about various places in the US and the world.

Then we rejoined the women and floated, feeling light as air after the treatment, to a pizza parlor, where the groups who had visited the other spas joined us. There were 20 of us, all together. We took over the restaurant and frazzled the poor pizza-maker, who couldn’t keep up with the orders.

After a long wait but a good lunch, some Slovak pals of our Piešťany group led us on an an hour and a half hike up into the hills, where we saw a man shoveling snow off his roof, a yard full of chickens, and many little icons and shrines. It was a steep, rugged walk, and the weather was good enough for me to be able to take my coat off and push up my sleeves. It was a beautiful, spectacular day.

(I’m the scruffy-looking dude in the center)

At the end of the hike, we popped out onto a small road. Across the road was a tavern—out in the middle of nowhere. We went inside for some beer and discovered a folk band in full swing—standing bass, accordion, harmonica, guitar, banjo—and rowdy, rustic singing.

We stayed for hours, listening to the great music, dancing, and being plied with shots of slivovitz by generous locals. It was wonderful. Little G____, aged 67, danced up a storm. D____ got goofily drunk. And we all felt deliriously happy to be in Slovakia.

The bar closed at 7PM, and we went outside to wait for the local bus to take us back into town. It was a clear, fine night, with a field of stars in the sky and only an occasional car passing by to light up the silhouettes of the crowd, still singing, and the band, still playing.

They kept playing, even on the bus, all the way to town, and they kept playing in town, leading a procession of people, pied-piper-style, down the streets of the spa town—rows and rows of us, arms linked, marching down the center of the street, singing (or at least la-la-ing) and laughing.

We broke away at the end, because the bar they were stopping at was already packed. We went back to G____’s for a chili and pizza feast, which ended the perfect day perfectly.

When everyone else had cleared out, A____ and P____ and I sat around talking about the day and the people and the country—the capacity for rowdy, companionable singing—in a bar, on a bus, on the street—and the other, sadder capacity we’ve seen, for suffering life, for feeling that life is to be endured, and can’t be controlled, much less loved.

There’s such a break—such an amazing line between the children and the adults here. The teenagers look like teenagers in the US, but once they’re out of school, they get old. You can see it in their faces—the eyes, dimmer; the skin, tighter; the mouths, drawn. R____ told me she was 28. I had thought she was ten years older. They become old and worn and bent and beaten, way too young. And I know we’ve got it easy, compared to them. This is a poor country, etc., etc. I know that. But I can’t help thinking they contribute to this, in a way, by being passive, by accepting hardship as “fate,” by not demanding what they want and need, by allowing their world to sink into mediocrity, inefficiency, and facelessness.

You’ve got to feed your love—and anger—to keep them burning, to keep you young and vibrant and tingling. It’s not just better food and better medicine (though it is that—a lot). It’s the interior life, too. It’s being able to live the lusty, joyful singing outside the bar and when you’re sober. Joy has to be more than merely a pleasant stop along the road to drunkenness. Happiness has to be life-induced, not just drug-induced. Otherwise, it’s fleeting and hopeless, and it always leaves you sadder than when you started. You have to make your world new.

I think this is what the myth of America was all about. It’s the intuitive leap Jefferson made when he dropped “property” out of Locke’s formulation and substituted, “the pursuit of happiness.” We forget that the inherent right is “pursuit.” We have the right to pursue; we don’t have the guarantee that we’ll be. And every right is an obligation—if you don’t use it, you’ll lose it. You have to chase your happiness—go after it with both hands wide open. Run if you have to. And when America is working correctly, it protects that pursuit; it helps you develop your talents and abilities, or at least it doesn’t hurt you while you develop them. It allows you to be part of the chase, whoever you are, and to become excellent if you work at it.

I think that’s why A League of Their Own, which I found merely cute at home, was so intoxicating when I saw it here with these high school girls. It’s the embodiment of that American Dream, which has nothing to do with white picket fences and everything to do with excellence, joy, and happiness—the ability to go as far as your abilities and your drive push you, no matter who you are.

And that’s why this whole trend at home, of feeling victimized by everything, is so wrong. Okay, you were misused, abused, screwed-up, hurt. Okay. It may not be your fault, but it’s yours now. It’s what you’ve got. The question of who to blame becomes irrelevant. The important question is: what are you going to do now? You’ve got imperfect raw material. Who doesn’t? How are you going to mold it, shape it, sharpen it into something wonderful?

Dwelling on past injuries is what imprisoned this whole continent and trapped it in endless cycles of hatred and violence—because too many people lacked the courage and the political traditions needed to make authentic choices and move forward. We have the traditions, but we erode them by niggling fights over their interpretation.

The myth has never been the reality. but you shouldn’t use the reality to dismiss the importance of the myth. Our best moments have come when we’ve been true to the myth. When you realize that your life is yours, and that those three inalienable rights are existential obligations—when you’ve taken a step in that direction—even a baby step—and started making your life into something wonderful, despite all the shit surrounding you and trying to drag you down—then you’ve taken a giant step.

September 6, 2024

Roads Not Taken

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Robert Frost

It’s two in the morning, I can’t sleep, and my my mind is fixed on sliding doors.

What is it with us and the multiverse right now? Why do we seem so obsessed with the idea of many worlds or alternate realities? Marvel movies started with fun stories about individual superheroes and ended its Phase I project with two big Avengers movies, the second of which was all about undoing the actions of the first. Characters died, but we knew a sequel was coming that would have to undo much of the damage. Don’t worry, we told ourselves as we watched beloved characters turn to dust: it’s not permanent; they’ll go back and fix it. And they did. And ever since, Marvel has become obsessed with the multiverse, and it’s all gotten very confusing and self-referential, and, to me, a little weightless. Nothing is permanent, nothing is irrevocable. Nothing matters.

On Apple TV, there’s a miniseries called Dark Matter, based on a very cool and twisty novel in which an average guy has to confront infinite possibilities and varieties, because every action and decision he makes (according to the theory) creates a new branch of reality, a new universe. And infinite is…well, it’s maddeningly infinite. There’s a universe where I put strawberries in my yogurt this morning instead of blueberries. There’s a universe where I put six strawberries in, instead of five. And so on.

I don’t think this cultural moment is because we’re all suddenly fans of edgy physics. I think it’s because we’re feeling vaguely middle-aged for some reason—personally and as a nation. And we had gotten used to feeling pretty feisty and adolescent, like the whole world was ahead of us and we could do anything or be anything we desired. Right now, we can’t seem to help looking back with some wistful regret, wondering how we got here and whether we could have done something different.

You can see it politically on both ends of the spectrum. Republicans’ entire platform is about rolling back the clock to some earlier, allegedly better time in America. Democrats are happily chanting. “we’re not going back,” but many of them can’t help looking at things like the electoral college and wishing there was a way to go back in time and get rid of it, because fixing it now seems so impossible.

In our own lives, it can be an addictive mind-game to play, whether you’re thinking about a literal multiverse, as in Dark Matter, or simply an alternate pathway, as in the movie, Sliding Doors. What if I had done X instead of Y? What would my life look like now?

Of course, we often rig the game by saying, “if I had known then what I know now, I would have done things differently.” But you didn’t know then what you know now, did you? If you did, you would have been a different person: Now You, not Back Then You. The question is, could Back Then You have made a different decision?

There’s a more deterministic school of thought that would say No. You are a contingent being, defined and limited by all the experiences and actions and decisions of your past. The things that made you who you were, at that moment, condemned you to take exactly the action that you took. Character is destiny. We know that it’s the only decision you could have made, because, look: it’s the decision you did make. Part of what makes you You is the fact that you did X at that point in time. Part of what made you do X is that you were You.

But there’s another school of thought that would say Yes, you might have made a different decision, because so much besides your personality and your past can affect your decision-making. Had it been cloudy that day, it might have affected your mood. If you hadn’t gotten a good night’s sleep. If you were suffering from a slight cold. If the sun had been in your eyes. If a mosquito had just bitten you, you might have been in a fouler mood just at the moment when you made some decision. So, yes, you did take Action X. But you didn’t have to. Any dumb, little fluke of the world might have put you in a slightly different frame of mind and affected your thinking.

There are many moments that I look back on and wonder about. Leaving Los Angeles and going back to Atlanta after graduate school to get married and do theater. Was that a mistake, especially since the marriage didn’t last? Would I have had a career in screenwriting if I had stayed in Los Angeles and given myself a chance? What about leaving Atlanta to move to New York to do theater with my friends? Would I have had more success, long term, if I had stayed put? Once I was in New York, what about quitting teaching to focus on running our theater company instead of merely being a member of it? If I had stayed in the classroom, I’d already be retired and collecting a pension. Or I might have become a principal or even a superintendent. Or what if I had committed to theater more aggressively at that moment, and especially when my first son was born, instead of walking away from that life to be a responsible father and support my new family? So many decisions, so many actions. I know why I took each one and why I thought it was the right thing to do at the time. But was it? Would life have been better, richer, happier, healthier, if I had acted differently?

But I didn’t act differently. I think I fall more into the deterministic camp. I didn’t act differently for all of the reasons why I acted exactly as I did. Those reasons were part of who I was at the time. Character is destiny—because of who I was, I did what I did. Because I did what I did, I continued becoming the person I have became.

In the end, I guess it doesn’t really matter. Yogi Berra may have said that when you come to a fork in the road, you should take it, but Robert Frost was wiser. You can’t take the whole fork. “Knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.” Once you make your decision, the only way is forward. There’s no going back. Your life is formed and defined, moment by moment, by each action you take, and life serves up the next question, the next choice you have to make, and then the one after that—fork after fork, branch after branch. You are what you did; you will be what you do. Irrevocable; weighty; it matters.

August 31, 2024

Note-Taking is Thinking

The most important things to teach children are critical thinking and problem solving skills, so that children can learn how to think.

No—the most important thing to teach children is academic content across the subject areas, so that children can have something concrete to think about.

No—the most important thing to teach children is how to take tests strategically and effectively, because, in the end, that’s how they’re going to be judged by the educational gatekeepers who hold children’s futures in their hands.

You would think, after teaching generations of children, we’d know which things were most important to focus on. But you’d be wrong. In fact, if I’ve learned anything in my years working in education (a debatable proposition), it’s that any sentence starting with “you would think,” is a sentence that’s going to end in tears.

Allow me to complicate the issue even further. I’m all for teaching skills and teaching content and even approaching tests strategically, but I’d like to offer another candidate for your consideration: the ordinary and often-overlooked skills of note-taking and studying.

Seriously?

Yes, seriously. The more I think about it, the more amazed I am that we obsess over what to teach, while spending so little time on what students should do with what we teach. I mean, obviously, we focus on “doing” when it comes to activities, assignments, and tests. We focus on final, summative products. But are we focusing enough on what students do in the earliest moments of learning? When we teach, what should our learners be doing? When they read, in groups or alone, what should they be doing? When they go home and reflect on their day, what should they be doing? And when they are preparing to engage in upcoming activities, assignments, or tests, to demonstrate their learning, what should they be doing to ensure that those demonstrations will be successful? How should students receive and process the information and ideas we provide them with?

I have very clear memories of being taught, in 6th grade, how to take notes in outline form. We were learning about ancient Greek mythology, and our teacher showed us how to organize information by listing things in sequences of increasingly indented numbers and letters or bullet points. It worked perfectly for something as linear as the pantheon of Greek gods. It helped us capture the important information in an easy-to-read format, and more: it helped us see how some details related to and supported the main ideas, and how other details supported or illustrated those first details. I still take notes in outline form, almost all the time.

I’m not saying that this method is the only method or the best method; I’m just saying that it is a method. How we catch something is just as important as how someone pitches it. Where I put information in a notebook or on a tablet is just as important as where I put my house-keys when I come home. In both cases, if I just throw stuff down randomly, it’s going to create anxiety down the road, when I need it and have no idea where to find it.

Learning how to take down information schematically also helped me see how information worked; it taught me that information had a structure and organization and purpose to it, and it taught me how to listen for that structure and organization. The way I wrote down notes actually helped me think about what the information meant.

And yet, very few of the teachers I’ve known have taught these skills explicitly as part of their curriculum. They have a variety of reasons for not touching this topic, including:

They assume these things were taught in an earlier grade

They assume these things are just “picked up” in life, somehow

They feel like they don’t have time in their pacing plan

They don’t know an effective method for note-taking, themselves

It simply doesn’t occur to them that explicit teaching of note-taking is needed

These are all valid and understandable excuses, but think about the unfortunate results. We spend all our time preparing engaging and rigorous lessons, honing our instructional practice to a fine point—but the people on the receiving end may not have the right tools to catch what we’re pitching. I’ve seen students writing down nothing at all. I’ve seen students desperately trying to write down every word I’ve been saying. They simply don’t know what matters, so they have no idea what to do with the flood of stuff getting thrown at them.

Some teachers I know type up and share their notes to help students prepare for an exam, or they make their PowerPoint presentations available within an online learning management system. But if we, or new technology tools using generative AI, do all the summarization and analysis for them, we’re not helping them process and internalize information for themselves. Students are not mere spectators in a class; they’re meant to be active participants in it. Learning is work.

What Could Be

If note-taking is as integral to learning as I suspect it is, it needs to be taken more seriously—not simply just at a classroom level, but across the entire school. Especially as students get older and deal with multiple teachers, it’s crazy-making to have to do things in completely different, often arbitrary ways. Why does your first-period teacher require your name to go in the upper left, followed by the date, when your second-period teacher requires your name to go in the upper right, after the date? Why does your science teacher post assignments on Canvas, but your English teacher posts somewhere else that she likes better? So much of what we do in school meets the individual needs and desires of the adults, while making the world incoherent for students and their parents. Some of the individualization may be important to the way the content is taught, but a lot of it is probably personal preference.

Think how powerful it would be if schools did more than simply hand out a planner at the beginning of the year. Imagine if at an opening assembly, the principal taught all students how the school expected them to use the planner (after some collaborative decision-making among staff). Here’s where you should write down your homework for each subject; here’s how we’d like to see you write it down, so that it’s the same across classes—easy for you to check (and easy for your parents to check). And then: here’s our school-wide, recommended method of note-taking. There are some basics we like to see across all subjects and grades. Your subject teachers may have tweaks and additions related to their subjects, and that’s fine: science teachers may need something extra, social studies teachers may, as well. But the core of note-taking is something we’d like to be consistent across grades and subjects.

Imagine how much easier it would be for teachers to check notes in class—and for mentors and coaches to see how students are doing during observations. Imagine how much easier it would be for parents to help their children at home. Imagine how much easier it would be for students to use their notes.

Students don’t have a union representing their interests, but they definitely have a vote in how school is run. If they find a class boring or confusing, they can zone out, check out, or act up in protest. We often treat those things as character flaws rather than pointed and deliberate commentaries on what we’re doing.

We need to pay attention to what the school day looks like and feels like to the student. We need to do whatever we can to decrease fragmentation and incoherence, to make school feel like a thoughtfully constructed, intentional community designed around learning, where the parts reflect and comment on each other and on the whole. If we want students to be active participants in and shapers of their learning, not docile spectators, we need to care about—and think carefully about—how we want them to engage with that learning, minute by minute and day by day.

August 24, 2024

Next Phase, Take Two

We thought we were entering our Empty Nest stage two years ago, when Son #1 started his final year of college and Son #2 started his first. But both chicks ended up returning to the nest at the end of that year, to regroup and rethink their next steps. They were back—but they weren’t moving backwards. They were young adults now, living more or less on their own, even under our roof—working part-time, cooking their own meals, doing their own things, making their own plans. Finding time to have a meal together or watch a movie was a challenge.

And now they’ve packed up and gone. Again.

For good? Who knows. They’ll always have a bed waiting for them if they need one. In the meantime, though, the house is very quiet again (and yes, okay, a bit cleaner), and it’s going to take some getting used to. Again.

Our sons are 24 and 20. Still young, still starting out, still stretching their wings. But they’re not little kids anymore. They’ve become young adults—excellent and fine young adults—different from each other in some ways and plugged into the same wavelength in other ways—just like you’d hope two brothers would be. They talk to each other more than they talk to us, now, and that’s just as it should be. The quiet is right, even if it’s a little lonely.

Fatherhood was the best thing that ever happened to me, and maybe (I hope) the best thing I’ve ever done. There’s no part of it that I haven’t loved.

I loved the 2AM feeding shifts, being alone with each baby in the deepest part of the night. I loved rocking them to sleep in the little Baby Bjorn. I loved carrying them around, when they were a bit older, in the little backpack I had, marching through parks and playgrounds with them riding behind my head, singing, “Here’s to Cheshire, Here’s to Cheese,” and “I Had an Old Coat.” I loved watching them play with blocks and LEGOs, making creatures with Sculpey or markers or crayons, hiding in forts, telling stories. I loved being there for them when they needed me—to remove a splinter, or to bandage a wound, or to find something that was lost, or just to hold them when they needed to cry.

I loved watching them grow up—questioning, learning, thinking, deciding. I loved cooking for them, driving them around, introducing them to my favorite music and movies—and then learning new movies and music from them. I loved watching each one figure out who they were and what they wanted to do in life.

And now they’re out there, starting to do it.

And so, I think again of the lines from the movie, My Dinner with Andre, that I quoted last week. Because I can’t help myself. And I look at old pictures of those little boys, and I wonder how so much life could have gone by so fast.

People hold on to these images of father, mother, husband, wife...because they seem to provide some firm ground. But there's no wife there. What does that mean? A wife. A husband. A son. A baby holds your hands...and then suddenly there's this huge man lifting you off the ground...and then he's gone. Where's that son?

August 17, 2024

Music That Made Me

For someone who never succeeded in mastering an instrument (though I tried once with trumpet, once with flute, a couple of times with banjo, and several times with piano), music has always been important to me.

That doesn’t make me special; music is important to almost everyone. I’m not a musicologist, like my sister-in-law, so I’m not going to try to explain why music matters, or what it does to us in general terms. I’m not qualified.

Instead, I’ll do what I did with books a couple of weeks ago—talk about some pieces of music that mattered to me: things that resonated with me at some point in my life and affected or changed something in me.

You know what a sympathetic vibration or resonance is? It’s when you play a note on an instrument or hit a note on a tuning fork, and the vibration of the sound waves makes another instrument or string vibrate at the same frequency, even when there’s no physical contact. That’s how I think about these pieces of music—when I hear them, they vibrate something inside of me. When I first heard them, they changed something in me. They’re landmarks of some kind, saying something about who I am.

And, fair warning, what they say is probably pretty pedestrian. Looking down the list, I see that nothing is very edgy or experimental or alt. But then, neither am I. I’m a late Boomer/Generation Jones kid from the suburbs who listened to The Beatles, The Who, and Springsteen in high school, not The Sex Pistols or even The Ramones. It is what it is. I yam what I yam.

In quasi-but-not-strictly chronological order…

Dear Pen Pal (T.E.A.M)My first grade class (when we were still living in Manhattan) put on a production of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown, which is pretty amazing, now that I think of it, because the musical had only just premiered off-Broadway about three years earlier. Somewhere in there, before or during first grade, I went and saw it. It was one of the first plays I was ever taken to see.

In school, I played Charlie Brown, complete with black construction paper zig-zags taped to my shirt, because no one could find or make a real “Charlie Brown” shirt for me.

This number, where Charlie Brown describes a disastrous baseball game to his pen pal, was my big solo, and all can I remember about it is falling off the stage during dress rehearsal. But it was my first time on stage, and it certainly lit a long-burning fire in me for doing theater—and loving musicals.

Why does this song stay with me? As happy and well-adjusted a first grader as I was, I think there’s something in the song’s bittersweetness that resonated with me. I’ve always liked a sad song or a melody tinged with a little mournfulness. The big rah-rah of the team’s singing, juxtaposed with Charlie Brown’s lonely solo…I’ve felt that thing, many times in my life.

Did I internalize the character of Charlie Brown a bit too much, maybe? Yeah, maybe. Maybe playing him onstage in first grade led me to play the role in real life: the put-upon straight-man surrounded by a cast of crazies. In the group but not always of the group. Or maybe it’s who I was fated to be, regardless, and it was just an inspired bit of casting by my first grade teacher.