Take the Long Way Home

This is how we learn: by looking at each thing, both the parts and the whole. Keeping in mind that none of them can dictate how we perceive it. They don’t impose themselves on us. They hover before us, unmoving. It is we who generate the judgments—inscribing them on ourselves.

— Marcus Aurelius

The presidential candidates are arguing over debates: how many there will be, who will host, what format each will take, and so on. Will each candidate have a minute or only 47 seconds to make a statement? Will the other candidate be able to rebut for 12 seconds or a leisurely 30?

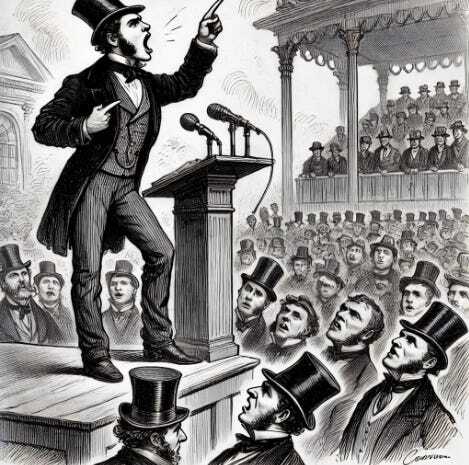

There was a time—1858, to cite one famous example—when political debates went on. Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas, campaigning for an Illinois senate seat, met seven times. Each debate featured a 60-minute opening address followed by a 90-minute response and then a 30-minute rebuttal. Three straight hours of bloviating in front of an audience. No softball questions, no timers running out. And, presumably, nobody talking about Hannibal Lecter.

Go back a little further, to the treason trial of Aaron Burr. At the conclusion of the trial, the prosecutor, George Hay, made a closing argument that went on for days and days—as long as nine hours in total, according to some sources. That’s three productions of Hamilton in a row, with some time in between for snacks. I see nothing in the historical record indicating that anyone in the courtroom shouted, “For the love of God, George, wrap it up!”

Sometimes the important things of the world require a little time and attention. Are we still capable of engaging with them at the level they require?

Anecdotally, I hear that teachers are getting complaints from students about having to read novels. They want shorter, punchier texts. And schools seem happy to comply. Make everything bite-sized. Better yet; make everything a video. Or, at least, accompany every text with a video. Everything seems to be designed from a starting assumption that kids don’t want to read anything, and need to be bribed or enticed into doing what’s required. Textbooks may have been a clever way of distilling complex ideas into easily-digestible nuggets, but apparently, even they are now Too Much.

It’s the attention-span, you see. It’s shrinking, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

But is that true? Do we need to make less demand on our attention these days because our attention span is shrinking? Or is our attention span shrinking because we make less and less demand of it?

A lack of commitment to longer-form reading in school shouldn’t be all that surprising, to be honest, and it’s not 100% due to pressure from students. We’ve had nearly a quarter of a century of NCLB/ESSA and its reading comprehension tests, few of which require students to respond to texts of more than a page or two in length. Schools still spend significant amounts of time and money preparing students to do well on those tests, so it’s easy to argue that the more the curriculum can resemble the tests, the better for all involved. What can one do? There may be an educational (and human) benefit to reading Bleak House, but too many administrators can’t see the connection between deep, wide reading and performance on a multiple-choice test. And, you know, those books are so hard.

Except…are they? Outside of school, millions of kids are reading things like Brandon Sanderson’s Stormlight Archives series, the first book of which comes in at a whopping 1,008 pages (just 28 pages shorter than Bleak House!). Did I mention it’s a series? It’s a series. Five giant novels, with complex world-building that can’t be any less alien and complex to deal with than Victorian England is. I’m not arguing that teenagers should naturally, without help, feel compelled to read about Victorian England. I’m just saying they’re capable.

We see similar hand-wringing in the visual arts. The cinema, a twitchy art form from the start, has lowered the bar on attention, they say: the average shot-length in an English language movie in 1930 was about 12 seconds. By 2014, it had decreased to 2.5 seconds. God knows what it is today. I don’t doubt the numbers. However, while the shots may be short, the stories are not. People seem to have no problem binging endless seasons of prestige TV, consuming multiple episodes of Game of Thrones or The Wire in an evening, night after night—both of which, again, present highly complex stories that take their time to spool out, set in intricately detailed political and economic worlds. As angry as people may have been about the final season of Game of Thrones, they seemed pretty happy to add to their 800 hours of investment by watching the new prequel. We are highly capable of sustained attention when we care. The question is: what do people think we care about or allow us to become invested in?

Have we convinced ourselves that today’s students aren’t interested in anything that doesn’t involve sex, dragons, or violence? Perhaps. Even if that were true, though, isn’t it our job to make interesting and relevant the things we think are important? Isn’t it our job to invite them into the larger world, and not let them linger in the nursery forever, thinking that’s all there is?

I think our attention span shrinks in the places where we don’t ask much of it or others don’t make demands on us. Our minds are flexible and malleable, and they can grow to meet pretty much any challenge. There are reasons why our species has taken over the entire planet, and it’s not just opposable thumbs. I think we’ve come to assume the worst of each other and ourselves, and then we go about making it real.

Our news media treats the presidential election as a horse race and can’t seem to talk about anything beyond who’s ahead and by how much. They barely ask any real questions of the candidates, and almost never push or challenge or follow up when they’re handed lies and pabulum. They don’t want to offend the candidates. They don’t want to bore their readers or viewers. It’s just a show, so let’s keep it peppy. People don’t want to engage (they think) in the real things of politics beyond a headline or a pithy quote—how a candidate’s policies might affect the economy, our rights, our nation’s position in the world, etc. Why bother with long form, investigative journalism? Either we couldn’t handle the complexity of the issues, or we’re too bored and decadent to care about them. So they seem to say.

And yet, are we genetically different from the people who stood and listened to Lincoln and Douglas debate for three hours? Are we a fallen species, somehow? I don’t think so. We are the same people. We just ask less of ourselves than we used to.

When we care, we invest. We can talk endlessly and in great detail about the Eagles’ offensive line and whether Nick Sirianni is up to the task of bringing the team back from its collapse last season. In bars and on talk radio, people offer up all kinds of arcane data, gleaned from multiple sources, to support their positions. Why should our sports discourse be able to handle more detail and evidence-based argument than our political discourse?

When we care, we become capable. Terezinha Nunes studied Brazilian street vendors who had little or no formal education, to see how they managed to perform complex mathematical calculations without a calculator or even a pencil and paper. European architects in the middle ages designed spectacular cathedrals that are still standing, without knowing much of anything about formal geometry or even being able to measure an angle with anything other than a wooden template.

We do not become capable of complex thought because of what happens in school. Sometimes I think we become capable in spite of it.

I’m tired of hearing that the kids can’t do it, that the kids won’t do it. I’m tired of hearing that we must teach them (over and over again, every year) explicit and decontextualized strategies for finding details in support of a main idea, for reading for inference, for understanding cause-and-effect relationships. I’m tired of hearing that we must work them, week after week, to make sure they can respond correctly to dumbass questions on meaningless tests. And that when they struggle, we must make all of the material smaller, shorter, easier, more relevant to what they think and care about right now. That all they can learn is what they already know. That we must bend down and down and down to meet them where they are…even though they only seem to be in that low place within the artificial context of the school day we’ve designed.

Preparation for the adult world is supposed to be our job, and the world doesn’t offer itself up to us in bite-sized nuggets, easy to digest. Real-life decisions rarely come with four answer choices. We are forcing a wide and complex reality through a tiny hole at the bottom of a funnel, and we expect what comes out to be of use to people. It’s not. It’s not even interesting—which may be why so many students are disinterested.

We don’t teach children how to read so that they can pass reading tests that demonstrate how well we’ve taught them how to read. That’s a snake eating its own tail, if ever I saw one. We teach children how to read so that they can use written language to learn things. Not to perform reading strategies; to learn.

Written text is a good medium for learning, because it can take as much time as it needs. It’s in no rush. Pick it up, put it down; no problem. Get lost (or get excited) and start over; no problem. Flip back a few pages to remind yourself what was just said; no problem. Go ahead and underline bits that you think are interesting. Linger on a line you like. Copy it on an index card and hang it on your wall for inspiration. If an essay needs more time to unfold its ideas, it can be a book. If a book needs more time to unfold its ideas, it can be a series.

Maybe we’re just not giving kids enough time to breathe.

We put children though school and make them think about things because, in theory, we want them to understand the world they’re about to inherit. And we want them to understand it so that they can put it to good use for themselves. Our goals for them are merely custodial; whether they know it or not, the goals are supposed to be theirs.

But if any of that is going to work, students need to read real things—things that matter—things that make them want to read more, go deeper, read again, argue. They need teachers who can help them see how and why those things matter, even if they were written hundreds of years ago or thousands of miles away. And then they need to do something with what they learn. They need to pull things apart and put them back together. They need to take ideas out for a test drive. They need to pull a thread and see where it leads.

The world is not made up of discrete, bite-sized nuggets, each one whole unto itself and dependent on nothing else. The world is a tangle and a jangle and a mess. Everything in it is connected to everything else in it, and everything in it is connected to something that used to be here and is now gone. It’s complicated.

Are we preparing our students for complication in the areas of life where their next steps are really going to need it? David Conley doesn’t think so. Here’s his take on what’s truly required for college readiness:

The college instructor is more likely to emphasize a series of key thinking skills that students, for the most part, do not develop extensively in high school. They expect students to make inferences, interpret results, analyze conflicting explanations of phenomena, support arguments with evidence, solve complex problems that have no obvious answer, reach conclusions, offer explanations, conduct research, engage in the give-and-take of ideas, and generally think deeply about what they are being taught.

We know our young people—and our adult friends and neighbors—are capable of this level of thought when it comes to the hobbies and pastimes they’re already immersed in. Why can’t schools find better ways to get students to engage at this level in things like history, literature, science, civics, philosophy, music, and art? Do we, the adults, secretly think these things are unworthy and boring? If we do, we should get out of the teaching business and make room for someone else.

Imagine if every high school teacher, regardless of the subject they taught, took Conley’s list to heart and made sure their curriculum provided (and demanded) opportunities for students to engage in each and every one of those activities, and made those activities as intellectually stimulating and viscerally rewarding as analyzing the home team or planning a Dungeons and Dragons campaign or arguing about whether the showrunners screwed Daenerys out of her rightful fate.

Make inferences, interpret results, analyze conflicting explanations, support arguments with evidence, solve complex problems that have no obvious answer, reach conclusions, offer explanations, conduct research, engage in the give-and-take of ideas, and generally think deeply about what they are being taught.

Every teacher. Every student. Every day.

Why not?

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers