Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand

September 19, 2025

Great Reckonings in Little Phrases

A World of Association

A World of AssociationJournalism is meant to tell you what the world is; poetry is meant to tell you what it’s like. Journalism does its job by marshalling facts (one hopes); poetry does its job by creating associations in your mind.

Poetry can be more concise than prose, because an association or comparison can, in a single image, convey a lot of information. That’s the joy and fun of poetic language—and it’s also what tends to drive schoolchildren crazy. When E.E. Cummings says, “life's not a paragraph/ and death i think is no parenthesis,” what, exactly, does he mean? Or, I guess: what, inexactly, does he mean?

He doesn’t say. Poetry doesn’t explain.

“Feeling is first,” he says, in the title of his poem, so how does that line make you feel? Your personal experiences with paragraphs and parentheses may determine what you bring to the party. Does he mean that life is not short? That it is not a rhetorical argument tightly focused on a single topic? That it refuses concise structure? That it’s not an annoying and repetitive chore mandated by a teacher? You tell me.

Is death not a parenthesis because it is, instead, a period—not the closure of one idea within others, but a permanent stop? Or is it not a parenthesis because it’s only half of a circle, not the a closed loop that death (as far as we know) is?

Whatever he meant and whatever you think it means—or however it makes you feel—he nailed it in 11 words, six of them being words like, “a,” or “is,” or “no.” And I needed…well, a paragraph. And I probably made a hash of it.

Poetic language is magic, but you need to be prepared for it. It requires prior knowledge—or, if not knowledge, then at least some experience of the world. If this is like that, but you have no experience of that, you’re left with very little insight into this.

This is more dire in metaphor than it is in simile, because simile does a little of the work for you, pointing you in the right direction. You may never have thought about this, if your teachers said, “a simile uses like or as,” and left it there. That’s technically correct, but it doesn’t tell you anything useful.

Let me give you a rude example. If I said, “that kid, Hugo, is such a pig,” most of you would know more or less what I meant—the more or less depending on your knowledge and experience with pigs. Even if you’ve never met a pig in person, you know something about them, or at least what we think of them.

When I say, “Hugo is a pig,” I’m making a complete or holistic comparison: X = Y, in all of its aspects. Fairly or unfairly, every association you bring to the idea of a pig you will now bring to this kid named Hugo. That’s a metaphor. If I think a pig is fat, dirty, messy, smelly, and noisy, well…sorry, Hugo, I now think the same things of you. Of course, if I think a pig is cute, cuddly, and super-smart, Hugo will come out looking a lot better. But that’s probably going to be the minority opinion.

If I wanted to be more precise in my description, I might restrict the association and say, “that kid, Hugo, is as messy as a pig.” Now it’s a more limited comparison: one aspect of X = Y. That’s a simile, and that’s why it uses like or as. Myra is as fast as a cheetah, but she resembles a big cat in no other way. Ahmed is sharp like a tack, but he is neither made of metal nor used to pin pictures on a corkboard. And so on.

One of the challenges of teaching poetry, or prose with poetic language, is that associations and comparisons used by authors may become increasingly remote to readers over time. That can happen because of changing culture and language, and it can also happen because more and more modern readers live in cities, surrounded by concrete and plastic, making older, more nature-based imagery difficult to understand. When a student reads that Robert Burns’ love is a like a red, red, rose, does he get anything out of that image beyond its red redness?

I wonder: what metaphors and similes should we expect from poets growing up today? How will they turn their world into meaning?

I wrote more about this aspect of poetry, and even that particular Cummings poem, in a post here last year. Enjoy.

I want to move to another problem.

A World of AllusionImagery and metaphor enrich our language if we can access them, but so does allusion. Instead of equating something with something else, writers sometimes quote, or paraphrase, or hint at powerful and well-known phrases from the past—from the Bible, from Shakespeare, from a wide array of literature that they assume their readers are familiar with. Those shout-outs to The Greats can work in a similar way to metaphor—they can suggest, in a phrase or a sentence, much more than the words actually say. They can carry a lot of weight in a small package, just like imagery can.

If I write about an act of political violence and call upon us to awaken “the better angels of our nature,” I’m saying more than I’m actually saying. I’m summoning the spirit of Abraham Lincoln, who spoke those words in his first inaugural address on the eve of the Civil War. I’m aligning my thoughts with his. I’m aligning our moment in time with his. I’m suggesting, perhaps, that our moment holds great peril for us if we cannot recognize each other as fellow citizens and fellow humans. I’m saying all of that without saying all of it:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

But, just as with metaphor, a reader who does not know my reference may see nothing resonant in the words. The red, red rose will simply be red. X = X.

Long before we had an internet, we had something like hypertext in our literature, with invisible links woven into our language, referring out of one text into the entire literary canon, out of one period of time into the vastness of human history. Of course, you couldn’t click on a link and go to the source; you were just expected to know it.

And for many years, people did know—even non-college-educated people. If you grew up with a King James Bible in your house, you got the biblical references in anything you might read or hear. If you had a collection of Shakespeare plays, your ability to access allusion was even greater. Those are probably the two greatest sources of literary allusion in the English language, but for many people today, those wells may have run dry.

What Do We Hold in Common?How important is it that we all know the same source material—that we all get the joke?

My wife certainly thinks it’s important. It’s been one of the core tenets of her Craftlit podcast for almost 20 years.

Does it matter if you know where “hoist with his own petard” comes from (especially if you don’t even know what it means)? Does it matter whether you know the source of the phrase, “all flesh is grass” (especially if you’ve never watched grass live and die from season to season)?

I don’t know. A turn of phrase can lose meaning for so many different reasons. I worry that much of what our authors have written is losing connection with those to whom we’re handing their work. If we still bother handing it at all.

We’ve had decades of fights about the literary canon: Should one even exist? If so, who and what should be included in it? Does it matter whether today’s students know who Boo Radley is, just because yesterday’s students did? Does Holden Caulfield matter as much as Hamlet (if Hamlet even matters anymore)? Should Janie Crawford matter as much as Jay Gatsby?

In general terms, does the lack of a shared literary heritage erode our ability to communicate with each other on any plain but the most basic, with no echoes or resonances or links? Or should reading just be a free-for-all, matching kids with their interests and being happy that anybody’s reading anything?

When E.D. Hirsch published Cultural Literacy in 1988, in the midst of the Reagan/Bush era, liberals like me were not inclined to want to listen to his message. Who cared whether kids were reading the same things that adults had read when they were kids? Multiculturalism was more important to the discourse at that moment—representing the diversity of our country and its history, bringing voices and groups into the curriculum that had systematically been left out. That was important and it remains important.

But.

Shouldn’t our goal be to hear more voices, not just different ones? To be in on more of the jokes? To be included in more of the IYKYK crowd, whatever the topic of the day might be? Isn’t there room for Janie and Jay when you’re reading about 1920s America? We are large, as I say here ad nauseam; we contain multitudes.

If you get the reference.

OK BoomerCulture may be nothing more than “the way we do things around here,” but every part of that definition matters: the way, the we, and the here. Every part helps define you and, by putting a border around what you do and where you do it, it helps distinguish you and your group from others, whether they’re ethnic groups, religious groups, residents of a particular area, or generations. Your music is your music, not that crap they play on the oldies station, even if that station is playing music no more than 10 years old. Harry Potter? Dead to me; on to the next. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Culture is a liquid, not a solid; it takes the shape of whatever it’s contained in. Each of us deserves art and culture that takes the shape of the lives we’re living.

But the whole idea behind “cultural literacy” was that some things defined us across all of those sub-groups; some things were shared, and they gave us a common vocabulary that could transcend the esoteric cultural references that only your in-group would know. As different as we all were, there were some cultural touchstones that we all shared—a little bit of unum in a nation of pluribus.

But was that just special pleading from someone who wanted to cram his own culture down everyone else’s throats and pretend that what was his was really theirs?

It’s a fair question.

Avoiding the Lonely RoadHere’s where I come down on it.

I love literature because it enmeshes me in a rich web of association that connects me to people and stories and ideas across continents and centuries. Whatever I encounter and grapple with in my life, I know it’s is like something else that has happened before, and my experience is like someone else’s.

There is great comfort in that. I am not walking the road of life by myself, even when I am alone. I’m riding down the river with Huck and Jim, trying to find a little free air to breathe. Or I’m Ellison’s invisible man (and his snarly Russian cousin) hiding out in the basement of my mind and curdling with resentment because of every dream that’s been deferred. Or I’m wandering lonely as a cloud, my heart filled with pleasure, just like Wordsworth. The more I read, the more company I have on the journey. My feet fit comfortably in their footprints.

It’s even more of a comfort when I can share what I’m feeling with my friends in a language they can understand. Or with strangers here on Substack, since I feel compelled to write, even if no one is listening. “Words, words, words,” as a disenchanted Dane of my acquaintance likes to say.

But what language will they understand? What do we all share?

Well, I could write a few paragraphs of quasi-journalistic prose telling people in simple, stark phrases exactly what my life is. I could do that. Plain and simple—just the facts. And you, the reader, would probably understand those facts and say, “OK.”

I mean, you’d get it. More or less.

But would you really get it—mind to mind and heart to heart? Would you feel it the same way I felt it, or at least understand how I felt it?

Maybe. But facts can hold us at a safe and sterile distance. I want more.

If I could cut through the facty forest and help you feel what it felt like—if I could transfer into your mind the experience of my hands and my heart—that would be different. If I could whisper, in a small, diamond-like concentration of thought, what I was feeling in a particular moment, and connect that to what you have felt and to what other people have felt, no matter what climate we’ve lived in or what political structure we’ve lived under or what age we’ve lived and died in…

Well, maybe, just maybe, you’d read my words with surprised recognition and a sharp intake of breath, and say, “Oh!”

The rest can be silence.

Closed parenthesis or period. It would be enough.

Friendly Reminder:

My new book, Box of Night, is available in paperback and Kindle eBook formats here. A little bit mystery, a little bit science-fiction, a little bit dystopian thought experiment. I hope you’ll give it a try.

If you do, and you enjoy it, let me know. And if you really like, it, please write a review at Amazon or Goodreads. Every little bit helps.

September 12, 2025

[2025 Re-post] Breathing In and Breathing Out

A re-post from last year to start the new school year…

The Bait-and-SwitchEducation can be transformative, or it can be transactional. In theory, it can be both. In practice, not so much.

What does it mean that education can be transformative? It means that learning can change you—change the wiring in your brain, change the rhythms of your mind. Just as a rigorous regimen of exercise, committed to over a period of time, will change the shape and capabilities of your body, so will a rigorous regimen of learning, committed to over a period of time, change the shape and capabilities of your mind. You will have thoughts and ideas you could never have entertained before. You will be able to do things—real things in the world—that you were never able to do before.

The value of going to law school, they say, isn’t that you come out with a bunch of legal facts at your disposal; it’s that you have trained your brain to think uniquely and differently—to think like a lawyer. When I started working on my dissertation in education, one of my advisors told me that the process was as important as the final product. The process was going to train me to pursue a line of inquiry and chase it to a conclusion in a radically different way than I had ever done before—the result of which, he said, was important enough that the university would change my name (by calling me “Doctor”).

OK—then what does it mean that education can be transactional? It means that if you comply with the rules, you can pass a course. If you pass enough courses, you can get a diploma. If you get a diploma, you can have access to higher-level schools and then jobs. You give; you get. You may end up with some new information in your noodle if you can hold onto it long enough. That can be part of the bargain, part of the ticket price. But the You at the end will still be the more or less the same You who walked in the door at the beginning. You + your purchase.

We do a lot of Big Talk in this country about the transformative power and potential of education. It’s why equity has become such a hot topic in our discourse: we want every child to have the access and resources and opportunities they need to make something wonderful—and new—of their lives. Education is the beating heart at the core of the idea of social mobility that we still hold onto, even as actual mobility has calcified over the years.

If what we promise to be transformational turns out to be merely transactional, we’ve committed a bit of a bait-and-switch on our young people. They gather up the necessary ingredients for a magic spell and take those ingredients to the wizard. Words are said; there’s a bang and a flash. But when the smoke clears, the frog is still a frog. They thought they were paying to become a prince, but in fact, they were just paying for the flash.

What Happened?Was it always a lie? I don’t think so. Alexander Hamilton’s education was transformative. Anyone who’s seen the play—especially this song—knows that. Abraham Lincoln’s education used to be a story every schoolkid read about. Frederick Douglass committed a literal crime by learning how to read—that’s how important and dangerous slaveholders understood education to be.

There are countless stories. I met an old man at a conference once who told me that because of the faith of a single teacher, he persevered against all odds and became the first person in his immediate family to become literate, the first person in his extended family to go to college, and the only person in the family’s history to leave their home state. Now he had grown children who were engineers and lawyers with children of their own. His education hadn’t just transformed his life; it had changed the history and trajectory of his entire family.

So what happened? I blame accountability.

Not the concept itself. I’m a fan of accountability when it’s authentic, and mutual, and healthy (as I’ve written about here). But accountability as an official movement, tied to high-stakes tests in math and reading at every grade level—the movement that started in the early 2000s—I think that has done a tremendous amount of unintentional and unanticipated damage.

The idea was to hold schools accountable to rigorous and broad learning standards, but the tests were how standards were measured, and the gap between a standard and how it was assessed could be profound. It created some cognitive dissonance. Which target was the serious one, the standard or the test? Which target mattered?

You could argue that they both mattered equally, or that one was a stand-in for the other. That was certainly the intent. But in many cases, tests started aiming at easier targets than the learning standards, either because the nature of a multiple-choice test simply couldn’t assess the actual level of understanding embodied by the standards, or because state governments needed a non-embarrassing percentage of kids to pass their tests. So, with limited time and breath available, would a teacher focus on the standard or on the test?

I think we all know what the answer was. Over time, we saw math and reading instruction narrow into test-prep sessions focusing on test-taking strategies. Working in education publishing, I saw school leaders reject high-quality programs if they offered material that varied even a little bit from the Big Test in look and feel and scope. Nothing was worth doing if it wasn’t aimed directly at test performance.

Teachers didn’t like it, of course. Principals and superintendents didn’t like it. But in the end, the test ruled. If writing wasn’t tested in your state, writing instruction withered. If history wasn’t tested, history got shoved aside, especially in elementary classrooms. If reading novels didn’t lead directly to test success, reading novels became a luxury. If cheating—individually or institutionally—saved one’s skin, then, well…

Transactional in the extreme.

The hangover we’re living in now, after more than 20 years of this stuff, casts a pall over everything. Reading is not about the joy of words or imagery; it’s not about engaging with another mind and seeing another way to understand the world. It’s not about culture, or values, or empathy, or poetry. It’s barely about learning anything. It’s just about downloading a bit of information that will only matter because it’s being tested—and the faster you can do it, the better. Efficiency is the key.

Look, reading for information is fine. Even skimming for information is fine. Sometimes that’s all you need to do with a text. But if every act of reading is undertaken solely to answer some multiple choice questions, why not just feed the whole text into ChatGPT and let it give you a bullet-point summary of the important information? Why work so hard? Save your energy. Cut to the chase.

I had friends in school who never understood the point of reading a novel when you could simply skim through the Cliff’s Notes to find out what happened in each chapter. As though “what happens next” is the only question worth asking about a narrative. And they had a point, I guess…if it is the only question worth asking.

Likewise, writing in school, after the elementary grades, is rarely about finding and cultivating your voice, or exploring and probing and testing an idea (of your own or of someone else’s), or learning how to share your thoughts with another human being. It’s about getting to the point, quickly and cleanly—delivering predetermined and required information as generically as possible and in line with the scoring rubric (which, in some cases, doesn’t care much whether you write in complete or grammatically correct sentences).

Again, that kind of writing has its place. But if that becomes the only point of committing words to paper or screen, why not just make a list of bullet points? Or, if more is needed, feed those bullets into AI and let the tool do the writing for you? What’s the point of craft or voice or tone? Why stick yourself in the middle of the process at all? Just let AI do the reading and the writing, and you can go scroll through some videos on your phone.

If school is purely transactional—you do what’s required to pass the course—then why not do the minimum required? Why not use all the tools available to you, as I wrote here? You’d be crazy not to. What does “cheating” even mean, if true understanding and transformation are no longer the point?

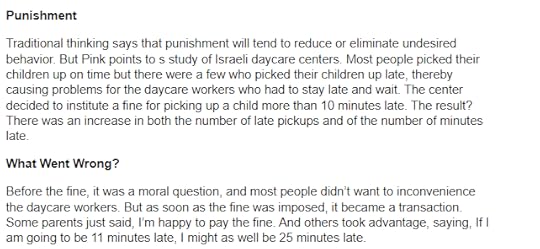

If there’s no value in doing the work, only in getting the result, then school and education are very different things from what I grew up with—very different endeavors from what I thought I was committing my life to. And when something of moral value becomes a simple transaction, it can do real damage to a community, as Daniel Pink shows us:

School can be a community where we build knowledge together, wrestle with ideas, and develop skill competence in order to become wise and capable human beings and useful members of our tribe. Or school can be a place we’re commanded to attend by law, where we sit still, speak only when called on, and jump through a variety of hoops that placate the authorities who have control over our lives. It’s kind of hard for it to be both. And what is required in order to thrive and succeed in each of those systems is very different.

Transformative Reading and Writing

Reading is like breathing in, and writing is like breathing out.

— Pam Allyn

I want to challenge us (and myself) to remember what reading and writing are really for—what they mean beyond their basic, transactional, informational purposes. It’s not super-complicated. I think Pam Allyn nails it.

Reading is like breathing in. It’s a way of taking the world—or somebody’s vision of the world—deep into ourselves. The ideas we take in are not finished products that simply pass through us. It’s not a passive process. “You read and you’re pierced,” as Aldous Huxley says. The words and phrases invade us in pieces and have to assemble themselves into ideas in our minds. Like the air that we take into our lungs, they go deep inside and spread out, touching many parts of us. And, like the air we breathe and the food we eat, the words we read bring nourishment.

We breathe in the same words millions of times, but they’re assembled into phrases and thoughts in different ways, used differently by different people. Each word, each phrase, takes on new shades of meaning in our minds every time we breathe in a new use of it. Even the same phrases—the same stories—can mean new things when we breathe them in again, years later. Other people’s words fill us nearly to bursting. And then we exhale.

Writing is like breathing out. All things that come into us transform and come out in a different form. Oxygen comes in, carbon dioxide goes out. Ideas are like that, too. I’ve known young writers who didn’t want to read because they were afraid of being influenced. But that’s absurd; everything influences us. Everything touches us. No one gets through life unscarred, untouched. The world pierces you and flows through you, but the unique you-ness of you, whatever that is, becomes a filter or a prism, and when you create—write, paint, sculpt, sing, whatever—when you exhale, you cannot help but transform those materials. They leave your mind and body with indelible traces of you on them.

As a teacher, I want to know what you think. But more, I want to know how you think—how the world has left its traces on you, and how you have interpreted and touched that world in return. I want to read students. I want to breathe in their words.

Do we take time to teach children how to write multiple sentences about a single idea—sentences that are beautiful, and then angry, and then funny, and then weird—to show them how flexible a tool a sentence can be? Do we take the time to ask all the children try to write the same story, with the same plot and the same characters, so that they can discover how radically not the same the resulting stories turn out? Do we help them learn how powerful that exhalation can become if they understand their own breath?

Or do we simply tell them that a simile is a something that uses like or as, and that a paragraph is a something that has five sentences, and call it a day? Simple rules for simple outputs? What is the scoring rubric that matters here?

No one expects every 18-year-old to know exactly who they are and what they should be about in life. But our job is to give them the tools they need to engage in that exploration—to search out the wisdom they need, to know how to distinguish wisdom from nonsense, and to share their thoughts and feelings—and, yes, even a summary of information on a TPS report—with other people. It’s our job to give them the tools they need to help them become themselves—the greatest possible version of themselves, as this old, rabbinic story tells us:

I don’t know what I’ll say when my time comes. But I know that “Choice C” will not be the right answer.

Friendly Reminder:

My new book, Box of Night, is available in paperback and Kindle eBook formats here. A little bit mystery, a little bit science-fiction, a little bit dystopian thought experiment. I hope you’ll give it a try.

If you do, and you enjoy it, let me know. And if you really like, it, please write a review at Amazon or Goodreads. Every little bit helps.

September 4, 2025

The View From There

I was in Jersey City last weekend for a family wedding. It was big and fun and festive, and once the party got started, it was loud. Live band, heavy bass, great for the dance floor but not so great for my tinnitus. I needed an occasional escape.

Fortunately, it was easy to step outside onto a promenade along the Hudson River to get some cool and quiet air. I took advantage more than once—sometimes to talk to my various cousins; sometimes just to stand at the railing and stare. The picture above is the view I was staring at.

It’s not an angle I was familiar with, having spent my New York City years either in Manhattan or in Brooklyn, with the opposite view of the skyline from across the East River. But even though I wasn’t used to looking at the city from the Jersey side, a lot of what I could see was familiar, as I had lived and worked in buildings and neighborhoods that were visible from where I was standing.

The skyline has changed a lot since I lived there, most dramatically and horribly because of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center. There’s a new tower there that didn’t exist when I was a New Yorker. At most, there was a pit that my office looked down upon (after my company moved downtown to, yes, take advantage of cheaper commercial real estate). I remember standing in our conference room, looking down at the construction site and wondering what was going to grow from that graveyard. I left before anything took root there.

Further uptown, I saw more buildings that didn’t exist back in my day. But a lot was still familiar. There was the World Financial Center, where I worked as a secretary for years while running a small theater company with my friends. There was the pier at the end of Christopher Street, near where I once lived, across from the Lucille Lortel Theater. There, further uptown, was the Empire State Building, obviously, where I had once taken my three-year old to give my wife some peace and quiet with our new infant son. So many places that held traces of my past, and hundreds more places hidden from view.

There’s an old science fiction story, I think by Robert Heinlein, in which someone describes what it’s like to view humans from outside the flow of time. Instead of discrete bodies occupying a particular space in a particular moment, we appear more like giant millipedes, occupying every place we’ve ever been, all at one—connected bodies stretching out behind us wherever we’ve been, and connected bodies stretching out ahead of us wherever we’re going to be.

Looking across the river at Manhattan, I thought about the younger me who walked up and down those streets: back and forth from the West Village to the East Village to teach school and attend rehearsals. Up and down Lexington Avenue to visit my grandmother. Up and down 6th Avenue to ride my bike (perilously) to the park on nice weekends. So many snaking lines crisscrossing the city and each other, marking my days and years there.

And more: there I was, as a child, in my first sojourn in the city, in my little blue blazer and the necktie that my father tied for me and left on a doorknob before going to work. There I was, walking with my mother down East End Avenue to go to school, or riding the crosstown bus with her to go see the dinosaurs. There I was, careening around Carl Shurz Park with my little corgi or riding my bike (perilously) along the cobblestones of the East River boardwalk.

There are parts of Millipede Me crisscrossing other places, of course: Atlanta, Tucson, the Berkshires, Virginia, Pennsylvania. And lines connecting one place to another as I moved from place to place. I’ve marked up the map pretty well in my 60+ years. But in my early childhood years and in my 30s, I spent a lot of time right there in New York City, and it was strange and a little wistful-making to stand across the river and think about those times and all the past versions of me that still existed out there, somewhere, if only I could see my whole life laid out in a single picture.

Some part of me is still there in that city, I thought, in all of those places, going to and fro full of dreams and hopes and fears—crossing my own path a million times, probably, just as I was crossing the paths of millions of others who had walked those streets before me, (also full of dreams and hopes and fears), never knowing they were there. Just as future young people will cross my ghostly paths, and maybe even follow some of my footsteps, without ever knowing it.

I don’t know why, but it was a comforting thought.

None of it is gone. Not even the old buildings. Everything changes, but somehow, everything remains.

August 29, 2025

[Re-post] The U.S. Without Us

I only wrote this back in March, but now that we have masked thugs patrolling our streets, sweeping up pretty much anyone whose skin-tone doesn’t match the white picket fence that they imagine defines America, I thought it might be worth re-posting.

The more I read and listen, the more obvious it is to me that my MAGA fellow citizens don’t want me as part of their glorious, New/Old America—and not just because of my political views. They have a very clear vision of what they want from their country, and it’s not the vision I was raised with, as tested and challenged as that vision has been throughout my life.

When I first saw scenes like this one from Hamilton, I remember saying, “that’s my country—the past reaching out to the future to teach us who we are, despite everything, and the future reaching back into the past to claim ownership, despite everything.” All Americans claiming a share of “American-ness,” in all of its messy complexity. It was exhilarating.

Other people, apparently, saw it as an intolerable hellscape, and they elected Donald Trump to put a stop to it.

So many things that seem blurry or distorted can come clear when you put the right lens on them. Why is there so much Republican attraction to Russia and Hungary all of a sudden? How could people have been wearing pro-Putin t-shirts at Trump rallies? Was it just to troll liberals? Was it just an attraction to cruelty and authoritarianism and some weird, strict, Daddy’s-home-ism?

No. There’s more to it than that. Politics is temporary, but racial and religious supremacism is forever. Some people seem to have become convinced that Russia and Hungary are our true, natural allies in the great cause of “Defending Our White, Christian Culture against the Encroaching Hordes.” That’s why former Cold Warriors can switch sides and start loving Mother Russia. The battle lines have been drawn.

Which is grimly clarifying, I guess. It puts a lot of things into perspective for me. Message received.

I read a Substack post a couple of weeks ago written by a White man of approximately my age, bewailing the state of the country, with its crime and its angst and its uppity Black people and its out-of-control immigration. He devoutly wished the nation could return to the peaceful and monochromatic state of his youth. His essay had many, many approving comments, including a few who took the extra step of blaming everything on The Jews. Because, you know, of course.

You’ll forgive me if I call bullshit on the whole thing.

First of all, this gentleman’s shining, innocent youth was back in the 1960s and 1970s, just like mine, and if he thinks there was less crime and turmoil and political angst back then, and no Black or Brown people demanding their rights, he’s looking through some seriously bubble-gum-colored glasses. The way-back of an old station wagon is not the best vantage point for viewing the world and understanding its history.

I get it: nostalgia is a serious drug, and Baby Boomers have been under its influence for a long time. But a responsible author should clue his readers in to his drug intake.

The tone of this gentleman’s essay was more angry than wistful, more eliminationist than accommodationist. “Why can’t they all just go away and leave us in peace?” was his basic message, and it’s a question that, if taken seriously and not just rhetorically, is pretty chilling. At a time when the contributions and even the existence of women and minorities as active parts of the American story are being invisible-ized, it’s a question we should take seriously. These people mean what they say, and even if they’re a minority, they’re a powerful one right now.

It’s not just yammering yahoos on social media. There are well-known, influential writers who have been flirting with this issue for years. As hard-right and hard-White as I knew Ann Coulter and Pat Buchanan to be, for example, I was taken aback a few years ago to see them talking about ideas like “settler stock” and how America was the birthright of Northern Europeans long before any pesky documents like the Constitution were written. The rest of us were just in the way, as far as they were concerned, and should be allowed to remain here only by the magnanimous good graces and with the explicit permission of our WASP overlords—which is especially horrific coming from an Irish American like Buchanan, who ought to know better.

If it was just the last 50 or 60 years that these people wanted to roll back—getting rid of Civil Rights laws and women’s liberation and gay marriage and all that—it would be one thing. One bad thing (bad for everybody). But some of these people seem to want to roll things aaaaaall the way back: pre-Ellis Island for sure, and maybe even further.

“Americans for Americans only,” as the charming Stephen Miller said at a recent, Nuremburg-esque rally. I don’t know about you, but I don’t think he was rallying for a more efficient system of legal immigration. He, too, is on the eliminationist side of the equation. Our purity must be preserved.

Which is nuts, because, like Pat Buchanan, he seems to think that his family would be spared and accepted into the volk while everyone else not of settler stock was purged. Mass deportations now! Just not my people.

I try to picture the America that their rhetoric seems to yearn for—one without any ethnic influences beyond England, Germany, and Scandinavia. See it with me, if you can: not only is there no hip-hop; there’s no rock and roll, no blues, no jazz, no gospel music. The Grammy Awards would just be versions of “Turkey in the Straw,” all the time. Ethnic food would be limited to pigs knuckles and knockwurst. I can’t even imagine what theatrical entertainment would look like if you removed from our history the immigrant influence on vaudeville, Broadway, stand-up comedy, and Hollywood. Would it just be a lot of this?

I know, I know, I’m being ridiculous. That’s not really what they want. But the Boomers who whine about the Good Old Days don’t seem to deal with the fact that their vision of white-bread America was compromised and infiltrated long before they were born. A lot has happened since the Mayflower! I mean, sure, it took a long time for women and gays and ethnic minorities to have anything resembling equal rights, but their influence was felt for years. It was in the mix.

The idea that a majority—that bulge in the center of a statistical distribution—can remain untouched and unaffected by the long tails to its right and left—it just isn’t true. Humanity is a continuum, and it’s dynamic. You can’t just snip off the tails and cast them away. That’s not how distributions work. Someone will always be the outlier.

When we think about the effects of immigration, we tend to think uni-directionally. You come to this country with your own language, your own regional and religious practices, your own clothing styles, etc. You’re in your own, little, ethnic enclave. But over time, you become “Americanized.” You move in the direction of the majority. Over the generations, you blend in more and more. We call that assimilation. But we could also call it regression to the mean: if you can’t get any more different or extreme, you tend to slide towards the center over time.

But the flow goes both ways. When you add new flavors to a soup or a stew, those flavors don’t vanish. They’re additive. Sure, they meld with whatever was in the pot originally. They lose a little of their distinctive tang. But they also change the flavor of what was in there. It’s not a one-way, zero-sum encounter. Immigrants become more “American” over time, but the flavors of their culture add to the mix and change what being “American” means. The anti-immigration folks know this very well; it’s exactly what they hate and fear. But it’s been happening since Day 1, and it’s never stopped happening. What “America” do the right-wing culture warriors actually want to freeze in amber? Do they even know?

Sure—the original, White majority of the colonies was mostly English, German, Irish, Scottish, and Dutch. Very northern European, very Protestant. But, even as early as 1776, they weren’t really those things anymore. They were something new. Whether they thought of themselves as loyal colonists or rebels during the Revolution, they did seem to think of themselves as something more than, or other than, Dutch or German or even English. They were a new nationality before the Declaration and the war gave them a new nation. Ben Franklin (in this movie version, at least) seemed to think there was something distinct about the people he was living with—something new that required its own nation.

So, even if our Founders all came from so-called “settler stock,” they were no longer what their immigrant ancestors had been. Things were already changing. Things never stop changing. So where, exactly, do Ann and Pat wish they could freeze the film? 1620? 1776? 1953?

I know Ben Franklin wouldn’t look around New York City today and say, “Ah—the Americans—my people.” But you know what? A whole lot of today’s Americans wouldn’t look at Ben Franklin’s America and call it theirs, either. I certainly wouldn’t. Neither would Ann Coulter, if she’s being honest. The overwhelming majority of us wouldn’t. Everything about it would feel strange and alien to us. Everything. Who “we” are is a moving target.

Like I said, I know this is all a bit of a straw-man argument. Ann and Pat and the Substack writer don’t really want to put on powdered wigs. They don’t want to eat only bangers and mash, and pigs knuckles for a weekend treat. They just want their 1950s America back, with cultural blinders firmly affixed, allowing them the benefits of a diverse society without having to acknowledge the people who are providing those benefits, without having to grant them any rights to vote, to shop, or to walk down the street without permission.

But gosh, that’s a hard state to maintain—keeping the cultural door open, but only just so much—letting in some things but keeping out others—enjoying the fruits without enfranchising the producers. You can do it for some period of time, I guess, but it takes something like a police state to pull it off. It takes Orwell’s “boot stamping on a human face—forever.” Which, as we can tell from the rhetoric of the Trump administration, is not necessarily off the table.

But...forever? I don’t know. Even with a figurative boot on their face, it’s hard to keep control of your kids, and their curiosities, and their appetites. Anyone who remembers the events of 1989 knows how hard it is to build a wall around a culture. Influence is constant, and fluid, and it permeates even the strongest of walls. The East Germans who poured through the holes they made in the Berlin Wall already knew what was on the other side, waiting for them.

Even my Substack writer’s blessedly WASPy 1970s weren’t as White as he imagines. The cultural palette was already changing. We already had Italian food (and remember: Italians were not originally considered “White” when they started coming here). We even had Chinese food (that group whose continued immigration was explicitly banned by law in 1882). Granted, it was all just pizza and spaghetti and chicken chow mein when I was growing up. It was terrible and bleached and bland. But it was here—it was part of America. Had been for years. Exotic compared with the Wonder bread and American cheese of the mainstream diet, perhaps. But we wanted it. We wanted it so much that pizza and spaghetti are now as American as apple pie. And once they became the norm, firmly part of the Big Middle, people started wondering what else might be out there on the edges, that might be even tastier. There was no Mexican food at all in the Long Island world I grew up in. None. Now it’s a staple of fast food, everywhere you look. The outliers don’t just regress to the mean; they’re actively pulled in.

How about bagels? Bagels don’t even qualify as ethnic food anymore. They’re just…bread. You don’t have to be a New Yorker or a Jew to ask for a bagel with a schmear. People eat blueberry bagels! How White can you get? Do Ann and Pat really want to foreswear bagels because their settler ancestors wouldn’t have known about them? Please.

What I’m saying is, America may have made my Jewish family less distinctly “Jewish” over time, but we also made America a bit more Jewish in the bargain. And that goes for all of us former immigrants. The middle affects the edges, and the edges affect the middle, and the “normal” is ever-changing. And thank God.

We celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day whether we’re Irish or not. An American holiday. We listen to jazz and R&B and hip hop. American pop. We add klezmer to jazz and blend both with European classical music, and we end up with Rhapsody in Blue. The American songbook. We blend immigrant vaudeville with British operetta and end up with musical comedies. American theater.

We are culturally voracious; we take everything and make it part of who we are. Our hunger for newness and variety is part of what makes us America. The center reaches out, takes, and normalizes what was once extreme. The mean wants to contain the whole. That’s precisely why Hamilton becoming mainstream theater was so exciting.

But when the narrow and limited and fearful people huddled together around that mean refuse to engage in any outreach, you get xenophobia, and homophobia, and anti-Semitism, and all of the desperate clinging to rotten ideas like ethnic purity.

Ethnic purity! Forget “settler stock.” This is way beyond that. These people seem to think there was, once upon a time (1620?), such a thing as a pure Englishman, the same way the Nazis thought about pure Germans. But no Englishman is a pure Englishman. What does that even mean? English DNA (and the English language along with it) is the result of years of conquest by Romans, Celts, Germans, Vikings, French, and God knows who else. No one is exempt; World history is an endless series of wandering, warring, conquering, raping, intermarrying, converting, etc. No one isn’t a mutt. Not unless they’ve spent a few thousand years isolated on an island.

Purity. What a small and constricting and stupid thing to hold onto. It should be laughed out of any room it’s spoken in.

Making America anything “again” is regressive and insane. The world only spins forward, and it was doing so 100, 200, and 1,000 years ago. We were never pure. We were never “only” anything. What we are in this country is the product of hundreds of years of cultural assimilation—every group affecting and inspiring and changing the other. You can’t un-stir that stew. The mix is mixed.

You can whine about all of that and wish it weren’t so. You can gather up your thugs and take to the streets to separate the This from the That. Or you can relax and go have a taco.

I know, for me, which choice leads to a happier life.

And, just to drive Stephen Miller crazy, here’s my new national anthem:

August 22, 2025

[2025 Re-Post] Education is an old world and a new world, both

I know it’s liable to drive tribalists crazy, but the truth about education is that it is both conservative and liberal, both traditionalist and progressive—always has been and always will be. And that’s okay.

I’ve always been a “you need two wings to fly” kind of person, so that idea doesn’t bother me much. It bothers a whole lot of other people, though. We’re in a “missiles over planes” mindset about pretty much everything these days: whatever it is, it must be one thing, aimed in one direction, fixed relentlessly on its target, with a mission to destroy something rather than carry someone to a new place.

Unfortunately for them, and perhaps fortunately for the world, our opinion about a thing doesn’t change its actual nature.

Regardless of one’s political mindset, the fact is that education is conservative and traditionalist at its core, and to pretend otherwise is silly. The point of teaching content—any content—is to connect our children to their culture and history so that they can continue the story that our forebears started and that we have been a part of. It’s a connection to our past, whether we’re teaching actual history or something like science, literature, or even math. The textbook is a collection of the things we’ve learned as a society, that we’ve decided (collectively) to keep in our brains for another generation.

Education allows each of us to be smarter than any of us; it allows us to access the history of thought, of experimentation, of discovery. The ability to access a wide and deep world of other brains, and not have to discover everything by ourselves, individually, through trial and error, repeatedly in each generation, is the superpower that has made humans what we are.

But education is also progressive. Maybe not in every time and in every place, but certainly here in our country. Our Founders read history to find out how other people in other places had solved problems similar to the ones they were facing, and they used what they learned to forge a new path for themselves—to do it better and to make it last. They were scientists and tinkers and optimists at heart.

We have students read novels about problems and conflicts and sadness and pain—not to bum them out and make them feel that the world is terrible, but to help them develop empathy beyond what they can see and hear, and to build within them a desire to help others and improve the world.

Yes—improve the world. Because the desire to make the world anew is our birthright as Americans (and sometimes our tragic flaw). If you ban those books and squelch those topics and decide that the Precious Flowers in the classroom can’t handle direct sunlight, you’re not going to grow very hardy plants. If you believe in American Exceptionalism—if you believe that this country has a unique job to do in the world—then you’d better make sure you raise children who understand the world, and who know how to engage with it—in all of its glory and ugliness. Antifragile students who can weather the storms of life and keep growing.

A med school professor who made a speech to my freshman class, the first day of college, spoke of the early European explorers and the importance of finding a point on the horizon past which you know nothing, and sailing straight for it. That—he said—is what education is all about. That—he said—is what this country is all about.

And yes, those explorers did terrible things when they reached what they thought was a new world, because they brought their traditions with them, which included all their limitations and ignorance and bigotry. And that part needs to be taught, too. The blessings and the curses. The desire to make a new world and the tragedy of importing your old hatreds into it.

Never stop asking. Never stop learning. Never be satisfied that you know everything you need to know. Never assume the land you stand on is the promised land simply because it’s where you are, or that you are its savior simply because you’re You (any more than you should assume that the land you stand on is cursed, or that you are a devil, simply because of your history).

The real promise is the fire that drives you forward.

But don’t go forward empty-handed…or empty-headed. Learn the past. Learn from the past. And build on it. Conserve…and progress.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

August 16, 2025

Camerado, I give you my hand

Regardless of your political affiliation, “Make America Great Again” is an absurd concept. At any given point in our history, we’ve been good in some areas, mediocre in other areas, and appalling in a few spots. That’s just reality. It will probably continue to be our reality for as long as we have a country.

I know there are some people who would prefer not to talk about anything appalling in our history or allow anyone else to talk about it. Those people are cowards, as far as I’m concerned, and the exact opposite of patriots. You can’t make your country better—any more than you can make yourself better—if you’re afraid to look in the mirror and account honestly for what you see there.

But “honestly” doesn’t have to mean singularly or exclusively critical or negative. I believe in what Bill Clinton once said—that there’s nothing wrong with our country that can’t be fixed by what’s right with our country. And maybe we need to be a little more embracing of each other and a little less constantly on the warpath against each other. Maybe we need to retire our inner Karens, stop complaining to the manager about every single thing that isn’t being served up to us exactly how we want it, and get back in touch with the grander American soul that Walt Whitman first defined for us.

Whitman and Us“I am large; I contain multitudes.”

If you know any line of Walt Whitman’s, you probably know that one. It’s part of a breathtakingly brash and egotistical poem that announced his presence in American letters, claiming that he was the entire country and the entire country was him, and he was here to say Yes to it all in all of its crazy-quilt complexity.

Walt Whitman knew a thing or two. America is not just the descendants of the Mayflower Compact signers, or the Daughters of the American Revolution, or the Daughters of the Confederacy, no matter what people like JD Vance want to believe. That may be what people in 1620 wanted Plymouth to be. It may even be what people in 1776 or 1789 wanted the country to be. But too bad for them; they wrote what they wrote, and they started what they started, and Lady Liberty lifted her lamp beside the golden door. And here we are.

Even before the influx of immigrants and the freeing of the enslaved, there were Americans who understood their nation as a reaching-out place more than a turning-inward place. The generation born after the Revolution grew up in a different world than their ancestors, or even their parents—they grew up inside the United States, and as Clay Shirky taught us about the Internet, those who grow up inside a new technology understand it far differently from those who adopt it as teenagers or adults.

Among the first generations to be born inside the United States, we got writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain, Edgar Allan Poe, and Walt Whitman. Those writers, more than any others I know, defined what it meant to be American. The founding generation invented the political structure; these generations invented the culture and the personality traits that future generations took for granted.

Whitman, born in New Jersey in 1819, wrote only a single volume of poetry, but he revised it and added to it throughout his lifetime, and he often talked about his book, Leaves of Grass, as though it were his body, or even his country.

Whitman was not a recluse or a philosopher. His poetry wasn’t precious or intricate. He knew he was part of a big, giant, baby of a country, and he wanted to wrap his arms around all of it, in reality and his poetry. His poems were often long lists of people—all kinds of people, doing all kinds of jobs, in all kinds of places. And his book is a series of explorations and celebrations of his country and its people.

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

“Allons!” he called to his readers. “The road is before us!”

If the road trip is the quintessentially American story, then Whitman, followed by Twain, invented that story for us.

Camerado, I give you my hand!

I give you my love more precious than money,

I give you myself before preaching or law;

Will you give me yourself? will you come travel with me?

Shall we stick by each other as long as we live?

He didn’t want to sit in dark rooms and brood. He wanted to get outside and breathe fresh air and live. He wanted to go everywhere and meet everyone. His poems are catalogues of people making and doing things. Whitman embraced the differences and marveled at the diversity he saw around him. He didn’t sugar-coat or ignore what was violent or painful. He knew war and he knew peace. He knew love and he knew hatred. He invented a new, American poetry that was muscular and athletic and energetic. He sounded a barbaric “yawp” over the roofs of the world.

Whitman and MeCreeds and schools in abeyance,

Retiring back a while sufficed at what they are, but never forgotten,

I harbor for good or bad, I permit to speak at every hazard,

Nature without check with original energy.

Maybe I admire this guy and his poetic life-force because I always felt like I lacked it. I was not the kind of person who knew how to respond to Whitmanesque invitations. I could perform on stage in plays, but I couldn’t talk to people at parties. I could go all night at a bar or a diner with three friends, but in a big room, filled with strangers? Hopeless. I was the guy hugging the wall, the guy who hung around for a miserable hour and then disappeared without telling anyone. I was the guy who cringed at the idea of “networking” or “schmoozing.” I did sit in dark rooms and brood.

But then I had kids. Two kids. One who was more of an introvert, who tensed up when another kid from his class waved at him from across a field, and one who was a social butterfly, chatting up everyone (mostly women), complimenting them on their hair or their nails, asking them where they got the necklace they were wearing, engaging with them with genuine affection and curiosity. And it was amazing to see how people lit up whenever that kid spoke with them—how seen and appreciated they felt in that moment, just in response to the slightest kindness and curiosity. And it made me remember something from an old movie.

The movie is Harold and Maude, one of my favorite weird, indie, 1970s movies, about an outgoing, life-affirming old woman and her relationship with a depressive, morose young man.

In the scene I thought about while watching my kid (which I can’t find on YouTube to share), Harold compliments Maude on how well she gets along with people. Maude shrugs and says, “Well…they’re my species.”

That line always hit me in the gut. Because they were my species, too, and what was I doing to get out among them and know them? Very little.

Maude, it turns out, is a Holocaust survivor—another tidbit that hits one in the gut. Because if she can find a way to say Yes to life and people, then what’s our problem?

I made a promise to myself to do better—to engage more, to ask more, to have fewer purely transactional relationships with the people I encountered. I ask about people more now—anyone I meet. I look them in the eye more. I let them know I see them and that I’m curious about them.

It changes everything.

That’s probably not a revelation to you, but it was to me. And I’m glad I was able to learn from my children and grow a little bit as an adult.

Social Media isn’t SocialGetting out into the actual world is not the same thing as texting friends or surfing the Internet. It’s easy to forget that, but I can see some of the Gen-Z kids, including my own, figuring things out and taking steps to fight against the so-called social media world that they’ve inherited. They see what it’s done to Millennials, Gen-Xers, and Boomers, and a lot of them don’t like what they see.

What does social media do? It identifies and defines us based on whatever we bring to it, and then it feeds our opinions back to us in an endless feedback loop that enhances and deepens and calcifies our views to an extent that becomes increasingly difficult to break free of. That’s not social. It’s solipsistic.

The remedy is obvious, even if it’s not easy. The remedy is to turn off the computer, leave your phone and your convictions at home, and set out, like Whitman, to encounter people as they are, wherever they are—to ask about them rather than decide about them—to be “curious, not judgmental” (as Whitman appears not to have said, despite what Ted Lasso thought). To be among the people, and with the people, and to find something to appreciate about them, whatever they may be.

That’s not an easy ask for some of us. It’s not an easy ask for me, sometimes. But I’m trying to do better. Because I know that the more I ask and listen, the less alien other people seem.

I am with you, you men and women of a generation, or ever so many generations hence,

Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt,

Just as any of you is one of a living crowd, I was one of a crowd,

Just as you are refresh’d by the gladness of the river and the bright flow, I was refresh’d,

Just as you stand and lean on the rail, yet hurry with the swift current, I stood yet was hurried,

Just as you look on the numberless masts of ships and the thick-stemm’d pipes of steamboats, I look’d.

I don’t expect everyone I meet to think the same way I do, or feel the same things that I feel, or agree with my beliefs and opinions. But I know that it’s better to ask about people than make assumptions about them. And I know that it’s better to listen, and learn, and understand people who think differently than to presume and condemn without listening. Even if it’s hard to do. Maybe especially then.

If we want to make America great, we need to get outside of our bubbles and see what America is—and find a way to say Yes to it, in all of its complexity and rawness and weirdness, regardless of what color its skin is, or what clothes it wears, or what language it grew up speaking, or who it wants to love. We need to stop hugging the walls of our biases and preconceptions and get out into the party and mix.

We are large; we contain multitudes. We should start acting like it.

August 7, 2025

The Game is Playing You

Sometimes, people ask me how long it takes to write a book, It’s kind of an impossible question. Even if I only dealt with the actual, literal, typing of words, there is no single answer. I’ve written four novels, and each one has oozed from my fingertips onto the keyboard at its own pace. And the actual, literal typing is just a small piece of the puzzle. There’s research (sometimes), outlining, thinking, more thinking, revising the outline, throwing away everything and starting over, and, of course, avoiding the project altogether.

We joke that avoiding writing is a major part of writing, but there’s some truth to that, and it’s not a bad thing. Walking away is important. Letting things bubble and percolate and rearrange themselves in the back of your mind—all of that is part of the process. You write with your whole mind—the conscious and the unconscious; the deliberate and the serendipitous. In the description of my new novel, I say something about how “the game just might be playing you,” and I think that’s actually true of writing. Am I writing the story, or is the story writing itself through me? Maybe it’s both.

Sometimes, I can do all the mechanical prep work and still not be ready to write, because the thing hasn’t gelled and cohered enough in my head to know how to start, or how to take the next step. Sometimes, I get the thing started and then hit some kind of snag that keeps me from moving forward. Sometimes, despite all my outlining, I’m just mystified by the big middle of the story, unsure how to get to the end that I’ve envisioned. I almost always have a picture of where I’m trying to go, but there are definitely times when the Yellow Brick Road gets overgrown in a dark wood.

And sometimes, to be honest, I just don’t want to take the next step, because I know it’s going to be hard. My last mystery novel, Cats in the Cradle, was like that. The subject matter was unpleasant and upsetting. I knew the research was going to be nauseating, and I knew that the writing was going to take me to some dark, bad places. It was my own damned fault; I’m the one who chose that subject matter. But it was easy to find reasons to avoid wading into those murky waters. I avoided it for months. Years, even.

My new book, Box of Night, was both fast and slow. Although the actual writing of the first draft went very quickly, the idea had been rattling around in my head for a long time—maybe 20 years or more. I didn’t have a fully formed idea back then—not a whole story, waiting to be attacked—but there were a few seeds and scenes that have been with me since the beginning. The first two chapters of the novel, I knew completely from Day One, as though they were scenes in a movie. I knew them two decades ago. They just had to wait for the rest to get filled in.

It’s a very different book for me—different tone, different style, different subject matter. I think it’s very current and relevant (even though the idea is as old as my children), so I’m excited to have it out in the world and have people read it.

The story is about old cities and new technology, careless corporations and hopeless people, moral stances and moral compromises. And it starts like this:

Suddenly he is deep in a forest.

If you’re interested, I’m running a book giveaway on Goodreads for the next week or so. Or, you know, you could just take a chance on a hopeful author and buy yourself a copy.

If you do read it, please let me know what you think—here, or on Goodreads, or on Amazon. It’s yours now. I hope you enjoy it.

July 31, 2025

[2025 Re-post] Reading is a Contact Sport

Reposting this from the summer of 2023 in honor of the upcoming publication of my novel, Box of Night—with a few updates re AI and Chat-GPT—relevant to our times and, not coincidentally, to my book.

The most famous depiction of a scene from Shakespeare is an 1851 oil painting by John Everett Millais. It depicts the character of Ophelia, drowning. Anyone who has read Hamlet would agree that the painting is a perfect representation of what happens to the doomed young woman, correct in every detail. Anyone who has seen a production of Hamlet has seen it play out exactly like this. Except they haven’t; the scene doesn’t exist—not on stage, at least. It is described only, in heart-breaking detail by Queen Gertrude:

There is a willow grows askant the brook

That shows his hoar leaves in the glassy stream.

Therewith fantastic garlands did she make

Of crowflowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples,

That liberal shepherds give a grosser name,

But our cold maids do “dead men’s fingers” call them.

There on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds

Clamb’ring to hang, an envious sliver broke,

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And mermaid-like awhile they bore her up,

Which time she chanted snatches of old lauds,

As one incapable of her own distress

Or like a creature native and endued

Unto that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death.

(Hamlet, Act IV, Scene 7)

Because it is described so beautifully, you have probably seen something in your mind’s eye (as Hamlet would put it) similar to the Millais painting, even though you never actually saw it.

When we read, we are not passive recipients of words or consumers of dead text; we are co-creators of a world. The author delivers a script to us, but we cast the play, build the sets, sew the costumes, and direct the actors—all on the stage of our imagination. Millais never saw Ophelia drifting down a river, except in his mind. What he painted is what he saw there. Maybe you saw the same thing. Maybe you saw something slightly differently. Your results may differ, even though the description is vivid.

Your results may differ. We don’t talk about that fact nearly enough in our English classes. My Great Gatsby is not yours. Not exactly. When Gatsby pines for Daisy, the object of his obsession may not look in my mind exactly the way she looks in yours. That’s because my history of romantic obsession, doomed or otherwise, mingles with Fitzgerald’s in a creative partnership to create a fully realized story that belongs only to the two of us. Just as the color red that I see is truly and authentically red, even if I can’t swear it’s exactly the same color you see, my Daisy is the true and real Daisy, even if she doesn’t look like yours.

One of my creative writing teachers, Terry Kay, made our class read his southern gothic tale about a drifter who wanders into a rural town and cons the inhabitants. After we finished the novel, Terry asked each of us to describe, physically, the main character. We were surprised to find out that none of our descriptions matched. Terry wasn’t surprised; he had planned it that way. The character was never actually described in the novel. It was left to each reader to imagine this slippery, dangerously charming character. And none of us had any trouble doing so, even without being given any clear information to guide us.

Terry’s character—and the unreachable Daisy, and every fictional character we encounter—is a probability wave of all possible interpretations—all true, all present, never resolving into a single, irrefutable image—until someone makes a movie and the metaverse of images collapses into a single portrayal.

I love movies, but movies are a different animal. On the page, on the stage, even in my earbuds, I get to co-create a story with the author. On the screen, all I can do is watch. There is only one Ice Planet of Hoth, and George Lucas has given it to me, complete. I can cosplay at conventions or write my own fan-fiction, to be sure—but my stories will always play out in his world, and his world will always look like what he created.

Maybe that’s not a problem when a movie is the original creation of a filmmaker. There was no Ice Planet before Lucas created it, so I guess he has every right to make us see exactly what he wants us to see. But when a movie is made of a beloved novel, something else happens. We lose our partial ownership of the story and surrender it to the filmmaker. We don’t mind so much if it’s a good movie—nobody seems to object to seeing Gregory Peck, and only Gregory Peck forevermore, as Atticus Finch—but it’s infuriating if we think a movie has “ruined” a book we love by miscasting or otherwise disrespecting it. We try to hold onto our personal image of the characters, but once we’ve seen the movie, it’s hard. They’ve taken it from us.

This is a recent phenomenon in the history of storytelling. Yes, we’ve had plays enacted in theaters for centuries, and on stage, a compelling actor may “own” a role to some degree. But even there, the reality of the story doesn’t live entirely on stage. It’s a mere sketch. The Globe Theater never looked like Elsinore; that bleak, winter castle existed only in our minds. We have to fill in the blank spaces, imagining what’s offstage when someone exits, and so on. And, of course, someone else can always come along and mount a new and different production whenever they like. The probability wave still exists. It is only the movies—only in the last 120 years or so—that storytellers have had a way of pushing their singular vision of reality, entire, into our minds, without our imaginative participation or co-creation. Our passivity in receiving completed “product” is relatively new.

I don’t know to what extent this holds true with non-fiction. Is there a cognitive difference between reading someone’s essay on history or politics, and watching an equally well-researched and well-argued video essay on the same topic? I honestly don’t know.

What I do know is that reading fiction should not be seen as another school chore—a time-consuming and probably second-best way of “getting” a story so that it can be summarized and explained in an essay or on a test. When students decide to “just watch the movie instead,” or consult Spark Notes, or, now, ask Chat-GPT to provide a summary and an analysis, we don’t do a great job of explaining why those are not good options. We tell them that it’s cheating, but we don’t tell them what they’re cheating themselves out of. If teachers don’t know why a book is worth reading—actually reading—then why should students know?

Knowing what happens next is not the only point of reading fiction, or even the most important point. Owning what happens next, feeling it deeply, letting it live inside of your like the owned thing it is—that’s the point. Letting it change you and become a part of you. Atticus says you can’t know another person until you’ve walked around in their shoes. We can’t know a book until we’ve walked around in its pages.

What does it mean to know a book?

Being able to report that some guy named Jake Barnes sat at a café in Paris, watching a woman named Brett—that’s simply information. When you read, though—when the story plays itself out in your mind—you get to be Jake Barnes, watching the mad swirl of friends and lovers dancing themselves into oblivion. When he says, “I,” he becomes you. It’s not only Hemingway’s story; it’s yours. The author gives you the clay, but you, like God, breathe life into it, giving his creation your living spirit. And when his people are animated by you, you’re invested in them, caring for them, suffering with them. You are not allowed to watch from a disinterested distance. You are walking in around in their shoes. You are implicated.

That’s what we come to fiction for. That’s why reading fiction matters. Don’t take the shortcut and let someone else make all the decisions for you so that you can pass a test. Don’t just watch in the dark. Pick up the brush and paint.

Share Scenes from a Broken Hand

July 25, 2025

The Limits of Compliance

In my upcoming novel, Box of Night (watch this space for more information), there’s a scene in which a mother confronts a school counselor about an evaluation for giftedness that her son recently completed, about which the counselor has some concerns:

His mother takes this in for a moment, then says, “Danny told me the point of the exercise was to show which cats had whiskers.”

“That was only part of the exercise,” the counselor says. “I had no doubt he could tell the difference. Some children can’t. That is not Danny’s problem. Following directions and respecting authority are.”

“I see,” says his mother. She looks over to him. Then she looks back. “Did you tell him that the point of the exercise—the whole point of him being in your office—was to follow directions and…respect your authority?”

“Mrs. Kanin,” the counselor says, with a dramatic show of patience, “the point of every activity in school is to follow directions.”

Is it?

Why do we send our children to school? We send them to learn about the world. We send them to learn something about themselves. We send them to make friends. We send them to become “socialized,” whatever we think that means. We send them so that they’ll have the tools to have happy and productive adult lives.

Many of those things have as much to do with behavior as they have to do with academics. In large classrooms, even academics has a lot to do with behavior. It’s hard to learn in chaos.

Unfortunately, those needs can lead teachers and administrators to prioritize behavior over everything else, making compliance the most important learning standard of them all, even if it’s not listed on any state documents or captured in any multiple-choice tests. Whether intentionally or not, having students sit still and shut up can end up meaning more—and teaching more—than a lesson in long division.

School reformers have decried the “factory model” of American schooling for decades. It can be dispiriting and uninspiring, and it may even run counter to the democratic aspirations and spirit of our country. In his 1975 book, The Night is Dark and I Am Far from Home, Jonathan Kozol railed against the conformity and rigidity of American schooling, and he drew a rhetorical line between its unspoken curriculum of mindless obedience and the persecution of war crimes and atrocities during the Vietnam War.

On a less extreme but still angry note, this 2010 presentation from Sir Ken Robinson dissected what he called the “batch-processing of children by age,” and its inability to meet the individual needs and gifts of our students.

If “I did what you told me to do” becomes more important than, “I understand what you were trying to teach me,” a lot of student mistakes and misunderstandings can fly under the radar. Compliance just requires a checklist. Learning requires a conversation.

Compliance is a chore, and nobody likes chores. If students feel that the daily lessons they sit through in school are chores for their teachers, how seriously will they take the content they are being taught? How many questions will they ask? How much will they care?

Why should they care about the big concepts in mathematics and science and language and history—the “enduring understandings” as Grant Wiggins used to call them—if the adults around them seem to care more about “coverage?” What is coverage if not a culture of “get ‘er done?” We covered the whole curriculum! We got to the end of the textbook before we ran out of time! Yay?

This has implications beyond school. The more things we see as chores that we need to “get done,” the less thoughtful and careful we are about those things. And some of those things matter a lot.

In my world of online product development, there are all kinds of requirements and compliances that need to be met. For many of them, a merely dutiful approach can end up missing a lot of important nuance and detail, leading to a less-than-ideal product.

One example: The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law in 1990. It took five years for the first set of web accessibility guidelines to be established. A lot of different guidelines from a lot of different authors were pulled together into a unified set of website accessibility guidelines in 1998, leading to version 1.0 of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, or WCAG, in 1999. We are now living under version 2.0 of those guidelines.

You would think (always a dangerous way to start a sentence) that after 35 years of law and 25 years of official guidelines, all commercial websites and online products would be universally—or at least minimally—accessible. They are not. You would think that programmers and developers would be leaving their college and graduate programs well versed in the WCAG requirements and well prepared to build accessible products. They are not. At two different companies, I’ve had to find budget to provide training to design and development teams to help them understand the requirements and know how to meet them.

Even among designers who claim to know the requirements, I’ve seen very few who take them to heart or approach them thoughtfully or creatively.

Thoughtful and creative? They’re requirements. Come on, dude.