Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 7

August 3, 2024

Books That Made Me

Books matter. It’s the one concession I’ll make to the book-banning fanatics who harass our local school boards. They know that the books children read can be influential—can inform and help shape their worldview, their moral compass, their empathy, even their sense of humor. That importance is exactly why we need to make sure children have exposure and access to as wide a variety of authors, styles, genres, voices, backgrounds, and opinions as possible—unless you want your child to grow up narrow, limited, two-dimensional, and afraid of the world beyond their home. I don’t think the Moms for Liberty crowd think that’s what they want for their children, but it’s what they’re going to get if they’re successful.

I’ve been thinking about books and authors, and it made me want to write about the books that made me. Not my top ten list or my all-time favorites: not Vonnegut, Waugh, Bradbury, MacLean (Alistair), or King (Stephen). No, these are the books that helped shape my mind and my heart—the books that helped me become who I am. Some of them, anyway; there have been many.

Winnie the Pooh

Books were a huge part of my childhood, and there are many that I remember fondly, many that I forced on shared with my own children. But the A.A Milne books—this one, House at Pooh Corner, and the poetry collection, Now We Are Six, are special. More than any other, they helped me become a lover of books and stories and characters. Part of their importance was that my mother loved them dearly and read to me from her own, well-worn and well-used childhood copies.

What mattered so much to me in these books? I think it was the fact that Christopher Robin had a such rich, well-populated, imaginative world available to explore and live in. That was intoxicating. It was the humor and gentleness of that world. And it was the decency and stalwartness of Pooh Bear, that great and loyal and non-judgmental friend to the anxious, the depressed, the bossy, and the pompous alike. I think he was probably my first fictional role model. In later years, I would come to admire and try to imitate the wit and snark and wily resourcefulness of characters like Bugs Bunny, but it was Pooh Bear who lived and lives in my secret heart.

The Thurber Carnival

Someone gave me this book when I was in my early tweens, and I didn’t know what to do with it at first. I knew who Thurber was because of his children’s book, The Thirteen Clocks, which I loved, but this was adult prose, and I was suspicious of it. The drawings in the back section of the book were funny, though, so I started there—with his old, New Yorker cartoons, and then his illustrations for famous poems, and then his snide takes on Aesop’s Fables, (especially “The Unicorn in the Garden.” I liked those. They seemed more or less in line with the humor I liked in his children’s book. So, once I had used up all of the bits with pictures, I went back to the front of the book and started reading his stories, and I fell in love. They had the same wit and wordplay I loved in my favorite children’s books, but they were not written for children. Each story was a perfect little gem, and this book held a wide variety of stories, including those that made up his childhood memoir, “My Life and Hard Times,” and classics like, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.” I think Thurber opened the door to grown-up reading for me. And the way I read Thurber’s book, reading all the fun stuff at the back first, and then starting over at the front to do the real work, is the way I still read Thurber’s magazine, The New Yorker.

Franny and Zooey

I read The Catcher in the Rye in high school, like pretty much everyone else in my generation—except for the kids in the neighboring Island Trees school district, where the book was banned (yes, children, even back then), an act which led our school’s sports fans to wave copies of the novel instead of pom-poms whenever we played against them. Did I like it? I liked it. Did I love it? Kind of—parts of it. But years later, when I stumbled across this book, made up of two longish and connected stories, it was a whole different ball game. The big, weird, raucous, over-educated Glass family, which Salinger wrote about here and elsewhere, and which later inspired the movie, “The Royal Tenenbaums,” engaged me more than poor old, lonely Holden Caulfield ever did. As an extended conversation about ideas more than a traditional narrative, it was something brand new to me, and something I continued to seek out in fiction. The speech at the end about shining your shoes for the Fat Lady said something about how faith and spirituality could be bigger and more interesting than organized religion—something that resonated with me and reawakened a curiosity that had lain dormant for a long time.

The Women's Room

My first year of college was a revelation in so many ways—leaving home, leaving New York, befriending kids I never would have met before, learning about things I had never had access to before (Philosophy! Anthropology! Beowulf being chanted in Old English!).

One of my classes as a baby English major was an elective in feminist literature. I don’t remember much of what we read besides this book and Carol Gilligan’s In a Different Voice. And I don’t remember much of the plot of this novel, aside from the bits of it that Lily Tomlin and Jane Wagner lifted (or were inspired by) for the second act of The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe. But I remember the effect the novel had on me as an 18-year-old fledgling male. I was just old enough to be able to start to understand the anger that coursed through the book, and to be able to see, through new eyes, the 1950s and 1960s that French grew up in, and the 1970s that I grew up in—the decade that she struggled with as a young married woman trying to lead an authentic life.

It made me see the women in my own family differently: my grandmother, educated and feisty, but surrounded by domineering male doctors who only wanted servility; my mother, more like my grandmother than either of them ever dared to admit, who held her beatnik soul at bay for years to be a good housewife and mother, and who let it all flourish in later years as a larger-than-life and beloved fifth grade teacher; and my mother’s first cousin, who saw what being a woman required in America and ran away from all of it, literally, to become a world-renowned photojournalist.

A book that helps you see the world, your family, and yourself differently: that’s what it’s all about, isn’t it?

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Someone bought this book for me as a gift when it was first published—my mother, maybe, or my grandmother—someone who was reading the New York Times Book Review. I had no idea what it was, but when I picked it up, I couldn’t put it down. From the first chapter, it was clearly a novel about ideas, which I liked. It also had an author intruding into the narrative to talk about the main characters in a way that I had only ever seen Kurt Vonnegut do—and I liked that. And it was thrillingly political and erotic and not-American in so many ways. Kundera became one of those authors whose works I had to hoover up and read as soon as I could get my hands on them. And he started my fascination with Prague and Czechoslovakia, and then my hero-worship of Vaclav Havel, all of which led to my brief teaching stint in a small, Slovak town a few years after the Velvet Revolution. And a play based on that experience, once I had settled in New York to make theatre with my friends.

The Empty Space

As a New York and Long Island theatre kid in the 1970s, I loved musicals, and I loved Neil Simon, and I loved Kaufman and Hart, and…that’s pretty much all I knew. Peter Shaffer’s play, Amadeus, blew my mind when I was a senior in High School, because the high theatricality of how it was presented, with the whispering venticelli and the use of silhouettes, and Ian McKellen changing from old man to young man in a split second with no tricks or effects, was unlike anything I had ever seen before. Later that same year, I saw Sweeney Todd, and it, too, rearranged my brain cells. Then I went off to college, where, after a year of conventional and old-fashioned plays, a new team was brought in to reinvigorate the program and do something innovative and new. The first play they did was the medieval morality play, Everyman, which we staged at multiple locations around campus, bussing the audience from place to place as they followed Everyman on his journey towards death.

This book, by Peter Brook, helped me put words and ideas behind the new kinds of theatrical experiences I was seeing, challenging my old fashioned idea of what a play could be and helping me put the old living-room plays of my childhood to rest. This book is how I could be open and willing and ready for new things after I graduated, when a new Artistic Director came in from England and hired me as his assistant. That was the beginning of my 15 years of making theater, post-college.

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

I don’t remember how I came across the book originally, but I associate it, along with Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, most strongly with my friend, Thor Hesla. I know that he and I were discussing both books when I went to visit him at Yosemite National Park in the late 1980s, where he was living in a M*A*S*H-style tent compound and working as a dishwasher, his way of making a small living off the grid while writing a book that was part childhood memoir and part treatise on nuclear defense strategy. Only Thor could have made that combination work.

Annie Dillard became another of those authors whose every work I had to seek out and read immediately, as soon as I became aware of it. I loved how she combined deep, quiet observation of the natural world with ruminations about God and the god-smacked, and thoughts about the fate of us little humans in a big old universe. She talked about Emerson, and Martin Buber, and the Baal Shem Tov, and how weasels had something to teach us about how to live. She connected a lot of strange dots for me.

Horace's Compromise

For a lot of my young adulthood, I tried making my way in the world as a playwright while supporting myself as a schoolteacher. I cared about them both, and wanted more out of both than traditional structures seemed to offer. Eventually, I had to choose one over the other. I tried sacrificing teaching to put more focus on theatre, but in the end, it worked out the other way around.

Why was I frustrated and disappointed with traditional structures in teaching? This book is one of the reasons. I started teaching at a small and very alternative high school in Atlanta, Georgia—a place where all of the teaching was 1:1 and all of the learning was self-paced. Nothing in the school looked like a school or worked like a school. Kids could get up and move around. Kids could go into the kitchen and make a snack for themselves when they needed to, or sit outside in the garden to read a book. It was a deeply human and respectful way to organize time, and it ruined me for the more traditional 45-minute-period/8-period-a-day schools I taught in subsequently.

In Horace’s Compromise, Ted Sizer goes back to school and walks through a day like a kid, horrified at the shattering of attention every time a bell rings, and by the insistence on thinking about X and then stopping thinking about X, on other people’s timelines, regardless of his needs or his moods or his interests. It’s easy to forget how strange and artificial and sometimes brutal a traditional, American high school can be. And once you start asking, “Does it have to be this way?” it’s hard to go back.

Just like it was hard to go back to being a thoughtless dude after reading The Women’s Room. Just like it was hard to sit still for a drab and static living room play after reading The Empty Space. Just like it was hard to pass a quiet, wooded area without pausing to look and listen after reading Pilgrim at Tinker Creek.

Books are a virus. Books get into your cells and change them. Books are not to be taken lightly.

We shouldn’t roll our eyes when the fearful among us want to ban books or exclude them or limit our children’s exposure to them. They aren’t silly people. They are angry and scared people, and they have their hand on an iron door, desperate to slam it shut. We need to join the fight and create a counterweight to keep that door open.

They understand that there is Big Magic at play in books. We should, too.

July 27, 2024

The Teachable Moment

“Teachable moment” is such a common phrase in education that it may be surprising to learn that the concept was actually invented by someone and isn’t Ancient Folk Wisdom. The phrase was coined by Robert Havighurst in 1952. It refers to the moment when the opportunity to teach something coincides with the student’s developmental readiness to learn it and with their interest in learning.

Most of the times that I’ve heard (or used) the phrase, it has referred to an unexpected, unplanned, fleeting moment that falls into one’s lap. It could happen when something in the wider world, that students care about, lines up with what you were about to teach. It could happen when a child expresses a surprising curiosity about something you’ve covered—when they sit up a little straighter and say something like, “Wait…what?” Something clicks for them, and you have an opportunity to use the moment for deeper engagement than you had expected.

How can we make the best use of that teachable moment, whether we’ve planned for it or stumbled into it? What do we do with it?

Is talking about something the same thing as teaching it? I don’t think so. Words can go in one ear and out the other. If we believe that actual learning requires some kind of change to you—that it rewires your thinking in some way or leaves a mark—then it has to be more than mere storytelling, as engaging as that might be. If you seize the teachable moment and make good use of it, it should lead to that glorious Aha! moment we all dream about, where we can see in a student’s eyes that the pieces have suddenly fit together in ways they never did before (something I wrote about in this post). Which means that the teachable moment requires a thoughtful learning experience of some sort, not just a fun conversation about a cool topic. We have to be prepared for these moments to happen, even if they take us by surprise.

Sometimes, simply throwing questions back at students and asking them to drive or at least participate in the teachable moment is enough to lift things above a traditional, “grown-ups are talking” explanation—more like a Socratic Seminar than a lecture. That’s not a bad option if you’re truly taken by surprise.

Dan Meyer, the math teacher, is a master at setting kids up for teachable moments. He manages to create these moments, deliberately withholding information to make kids pay more attention and start asking questions. He finds ways to entice kids into inviting him to teach. He teaches because they demand it. It’s pretty amazing.

Sometimes, a teachable moment presents itself outside the classroom in other parts of a child’s life. I remember Grant Wiggins posing an icebreaker question at a workshop, asking us about the most meaningful learning experience we’d ever had, that was planned and structured for our benefit. As it turned out, few of the experiences people talked about had taken place in a classroom. People talked about athletic coaches, music tutors—people who taught them something by making them do something. It was a pretty embarrassing revelation in a room full of educators, to find that people’s most memorable and meaningful learning experiences happened outside of school.

What would you answer? Would it be something a classroom teacher did for you? Or was it a parent, a coach, a mentor, or someone else?

When I was in the workshop, I thought of two experiences from my previous life in the theater. One had been a casual comment that changed the way I wrote; the other had been something formally structured for me, which is what Wiggins was looking for.

The casual comment had come from a professor in my MFA program. He had read a draft of my thesis play, The King of Infinite Space, which was all about revolution and freedom and oppression. The draft was big and messy and unruly, and he had plenty to say about all of that. But he also wanted to say something about the old commandment of, “show, don’t tell.” He decided to model that very commandment in how he gave me feedback. He asked me what I thought my play was about—what the overall theme was. I said I thought it was mostly about freedom. “Good,” he said. “Go back into the play and remove that word wherever you see it. Deny yourself the word and see what happens.”

He didn’t tell me why. He didn’t tell me what the result would be. All of that was for me to discover on my own. And it was great advice. By deleting the most important word, I had to find other ways—more dramatically interesting ways—to communicate the idea. I had my Aha! moment—though it took a few weeks of work for the light bulb to get lit.

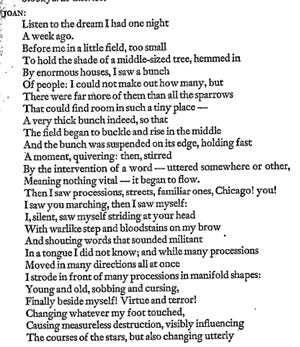

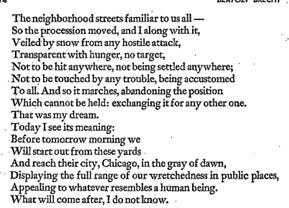

The more structured experience had come earlier, while I was serving as assistant director for the theater department at the college I had just graduated from. We were working on a production of Bertolt Brecht’s play, Saint Joan of the Stockyards. I had dutifully been reading all about Brecht and his famous alienation effect so that I could of use to the director. But had I learned anything?

One night, when we were going to be rehearsing with just the lead actress, the director (a big, hairy, imposing Englishman) announced that he had opera tickets and was leaving the rehearsal in my hands. And off he went.

We were meant to be rehearsing this monologue:

So, I did my best to help the actress, and we went over the piece many times before we called it a night and went home. We were pretty pleased with the work we had done.

The next day, we reconvened and showed the director the monologue. The lead actress emoted all over the place. She relived Joan’s dream in front of us, trying her best to summon up both the imagery of the dream and her emotional reaction to it. You could feel her hope, her fear, her resolution. I was very proud of her.

The director watched it all silently, nodding his head, and then he said, in his best Michael Caine voice, “That was lovely Stanislavski, but it was shit Brecht.” Neither the actress nor I knew how to respond to that. So the director got up out of his seat and took over. He had the actress walk over to a stack of metal, folding chairs on the side of the stage and move them, one by one, from their stack to the center of the stage, opening them and putting them in rows. As she was walking back and forth, doing the task, he barked out orders to go faster and faster, until, by the end, she was out of breath. “Now,” he said, “Quick. Turn to the chairs and do the speech.”

Because she was tired and out of breath, but she was still an actress trying to convey something, all of her energy and emotion went into just getting the words out to her imagined audience. No remembered feelings; no performed emotion. Just the urgency of communicating something important to people.

She finished, and the director turned to me and said, “That’s Brecht.”

“Great,” I said. “Why didn’t you just tell us that, last night?”

“Because you wouldn’t have learned anything,” he said.

And he was right. Quasi-abusive, perhaps, but right. I had done all the reading. I had understood it, kind of, intellectually. But doing it—wrong, first, and then differently—seeing the result and the effect of both versions—gave the actress and me the Aha! moment we needed. It was visceral. we could feel it.

How often do we structure learning experiences in the classroom to allow for this kind of discovery—this kind of Aha! moment? Traditionalists who despise the idea of “discovery education” would likely complain that it’s an inefficient use of classroom time and a demand of too much cognitive load for students. Teachers should just deliver the information and give students time to practice their skills. But even they believe in a structured process that leads to a “gradual release of responsibility,” with the student gaining independence and competence at the end of the process.

When and how does polite compliance with a teacher’s instructions transform into mastery and ownership? It’s not simply mindless repetition—and nobody argues that it should be. We all know that something has to change; something has to click. Something has to make the student say, “Oh! I get it now.”

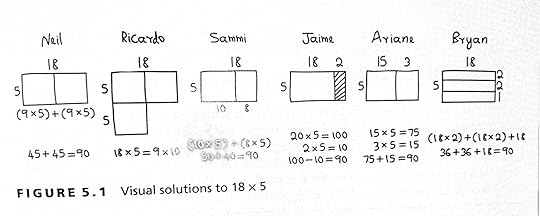

Maybe there are times for more constructivist kind of project, where students have to “discover” a formula or a rule on their own, instead of being told what it is. Maybe there are times to have students engage in a worked example or listen to a teacher model a thought process before doing problems their own. There’s no one right method that works all the time, in all cases. But we know that it’s good for learners to get their hands dirty, literally or figuratively. Understanding comes from manipulation—from use. You’d never buy a car without taking it out for a test drive, no matter how much you’ve read up on it and studied its specifications. Students need to take their learning out for a test drive, too—even if it’s just testing out their ideas in a long-form discussion.

I remember watching Bror Saxberg and Frederick Hess talk about a new book they had published. They were reframing the job of teacher, in this new(ish) digital age, and they asked us to think of the role as a “Learning Engineer,” someone who structures experiences in order to facilitate other people’s learning. That’s very different from thinking of the role as someone who simply explains things and then assesses understanding.

If the job is to facilitate learning, how to do you structure and plan for that Aha! moment in your own practice?

July 20, 2024

Breathing In and Breathing Out

The Bait-and-Switch

The Bait-and-SwitchEducation can be transformative, or it can be transactional. In theory, it can be both. In practice, not so much.

What does it mean that education can be transformative? It means that learning can change you—change the wiring in your brain; change the rhythms of your mind. Just as a rigorous regimen of exercise, committed to over a period of time, will change the shape and capabilities of your body, so will a rigorous regimen of learning, committed to over a period of time, change the shape and capabilities of your mind. You will have thoughts and ideas you could never have entertained before. You will be able to do things—real things in the world—that you were never able to do before.

The value of going to law school isn’t that you come out with a bunch of legal facts at your disposal; it’s that you have trained your brain to think uniquely and differently—to think like a lawyer. When I started working on my doctoral dissertation in education, one of my advisors told me that the process was as important as the final product. The process was going to train me to pursue a line of inquiry and chase it to a conclusion in a radically different way than I had ever done before—the result of which, he said, was that the university would change my name (by calling me “Doctor”).

What does it mean that education can be transactional? It means that if you comply with the rules, you can pass a course. If you pass enough courses, you can get a diploma. If you get a diploma, you can have access to higher-level schools and then jobs. You give; you get. You may end up with some new information in your noodle if you can hold onto it long enough. That can be part of the bargain, part of the ticket price. But the you at the end will still be the more or less the same you who walked in the door at the beginning.

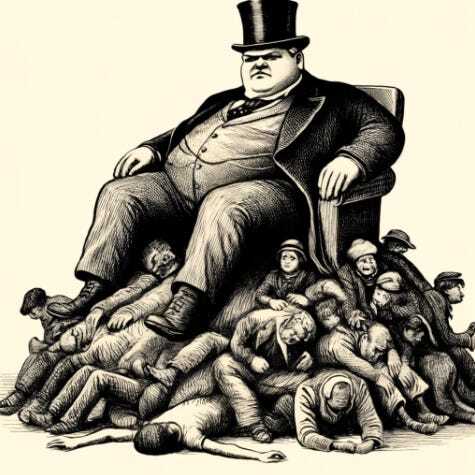

We do a lot of Big Talk in this country about the transformative power and potential of education. It’s why equity has become such a hot topic in our discourse: we want every child to have the access and resources and opportunities they need to make something wonderful—and new—of their lives. Education is the beating heart at the core of the idea of social mobility that we still hold onto, even as actual mobility has calcified over the years.

If what we promise to be transformational turns out to be merely transactional, we’ve committed a bit of a bait-and-switch on our young people. They gather up the necessary ingredients for a magic spell and take those ingredients to the wizard. Words are said; there’s a bang and a flash. But when the smoke clears, the frog is still a frog. They thought they were paying to become a prince, but in fact, they were just paying for the flash.

Was it always a lie? I don’t think so. Alexander Hamilton’s education was transformative. Anyone who’s seen the play—especially this song—knows that. Abraham Lincoln’s education used to be a story every schoolkid read about. Frederick Douglass committed a literal crime by learning how to read—that’s how important and dangerous slaveholders understood education to be. There are countless stories. I met an old man at a conference once who told me that because of the faith of a single teacher, he persevered against all odds and became the first person in his immediate family to become literate, the first person in his extended family to go to college, and the only person in the family’s history to leave their home state. Now he had grown children who were engineers and lawyers with children of their own. His education hadn’t just transformed his life; it had changed the trajectory of his entire family.

So what happened? I blame accountability.

Not the concept itself. I’m a fan of accountability when it’s authentic, and mutual, and healthy. But accountability as an official movement, tied to high-stakes tests in math and reading at every grade level—the one that started in the early 2000s—I think that has done a tremendous amount of unintentional and unanticipated damage.

The idea was to hold schools accountable to rigorous and broad learning standards, but the tests were how standards were measured, and the gap between a standard and how it was assessed could be profound. It created some cognitive dissonance. Which target was the serious one? Which target mattered? It turned out that the test scores, tied as they were to punitive actions from the state, mattered a great deal more than the actual learning. Thus, a new transaction was born: get scores over a certain threshold and you’ll be left alone.

We all saw math and reading instruction narrow into test-prep sessions focusing on test-taking strategies. Working in education publishing, I saw school leaders reject high-quality programs if they offered material that varied even a little bit from the Big Test in look and feel. Nothing was worth doing if it wasn’t aimed directly at test performance. Teachers didn’t like it, of course. Principals and superintendents didn’t like it. But in the end, the test ruled. If writing wasn’t tested in your state, writing instruction withered. If history wasn’t tested, history got shoved aside, especially in elementary classrooms. If reading novels didn’t lead directly to test success, reading novels became a luxury.

Transactional in the extreme.

The hangover we’re all living in now, after more than 20 years of this stuff, casts a pall over everything. Reading is not about the joy of words or imagery; it’s not about engaging with another mind and seeing another way to understand the world. It’s just about downloading information—the faster, the better. Efficiency is the key. Which is fine in some contexts. Sometimes all you really need is to distill some basic facts from a text. But if every act of reading is undertaken solely to answer some multiple choice questions, why not just feed the whole text into ChatGPT and let it give you a bullet-point summary? Cut to the chase.

I had friends in school who never understood the point of reading a novel when you could simply skim through the Cliff’s Notes to find out what happened in each chapter. As though “what happens next” is the only question worth asking about a narrative. And they had a point, I guess…if it is the only question worth asking.

Likewise, writing in school, after the elementary grades, is rarely about finding and cultivating your voice, or pursuing and exploring an idea (of your own or of someone else’s) to its conclusion, or learning how to share your thoughts with another human being. It’s about getting to the point, quickly and cleanly. Delivering information as generically as possible. That’s how you’ll need to write on a job somewhere, so that’s what writing is for. So, again, if that becomes the only point of committing words to paper or screen, why not just make a list of bullet points and let AI do the writing for you? Better yet, why stick yourself in the middle at all? Just let AI do the reading and the writing.

If school is purely transactional—you do what’s required to pass the course—then why not do the minimum required? Why not use all the tools available to you, as I wrote here? You’d be crazy not to.

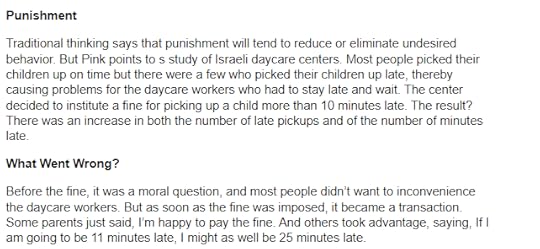

If there’s no value in doing the work, only in getting the result, then school and education are very different things from what I grew up with—very different endeavors from what I thought I was committing my life to. And when something with moral value becomes a simple transaction, it can do real damage to a community, as Daniel Pink shows us:

School can be a place where we build knowledge, wrestle with ideas, and develop skill competence in order to become wise and capable human beings. School can be a place where we sit still, speak only when called on, and jump through a variety of hoops that placate authorities who have control over our lives. It’s kind of hard for it to be both. And what is required in order to thrive and succeed in each of those systems is very different.

Transformative Reading and Writing

Reading is like breathing in, and writing is like breathing out.

— Pam Allyn

I want to challenge us (and myself) to remember what reading and writing are really for—what they mean beyond their basic, transactional, informational purposes. It’s not super-complicated. I think Pam Allyn nails it.

Reading is like breathing in. It’s a way of taking the world—or somebody’s vision of the world—deep into our lungs. The ideas we take in are not finished products that simply pass through us. It’s not a passive process. “You read and you’re pierced,” as Aldous Huxley says. The words and phrases invade us in pieces and have to assemble themselves into ideas in our minds. Like the air that we take into our lungs, they go deep inside and spread out, touching many parts of us in order to bring nourishment. We breathe in the same words millions of times, but they’re assembled into phrases and thoughts in different ways, used differently by different people. Each word, each phrase, takes on new shades of meaning in our minds every time we breathe in a new use of it. Even the same phrases—the same stories—can mean new things when we breathe them in again, years later. Other people’s words fill us nearly to bursting. And then we exhale.

Writing is like breathing out. All things that come into us transform and come out in a different form (I know, I know—resist the urge to be disgusting). I’ve known young writers who didn’t want to read because they were afraid of being influenced. But that’s absurd; everything influences us. Everything touches us. No one gets through life unscarred, untouched. The world pierces you and flows through you, but the unique you-ness of you, whatever that is, becomes a filter or a prism, and when you create—write, paint, sculpt, sing, whatever—when you exhale, you cannot help but transform those materials. They leave your mind and body with indelible traces of you on them.

As a teacher, I want to know what you think. But more, I want to know how you think—how the world has left its traces on you, and how you have interpreted and touched that world in return. I want to read students. I want to breathe in their words.

Do we take time to teach children how to write multiple sentences about a single idea—sentences that are beautiful, and then angry, and then funny, and then weird—to show them how flexible a tool a sentence can be? Do we take the time to have all the children write the same story, with the same plot and the same characters, so that they can discover how radically not the same the resulting stories turn out? Do we help them learn how powerful that exhalation can become if they understand their own breath?

Or do we simply tell them that a simile is a something that uses like or as, and that a paragraph is a something that has five sentences, and call it a day? What is the scoring rubric that matters here?

No one expects every 18-year-old to know exactly who they are and what they should be about in life. But our job is to give them the tools they need to engage in that exploration—to search out the wisdom they need, to know how to distinguish wisdom from nonsense, and to share their thoughts and feelings—and, yes, even a summary of information on a TPS report—with other people. It’s our job to give them the tools they need to help them become themselves—the greatest possible version of themselves, as this old, rabbinic story tells us:

I don’t know what I’ll say when the time comes. But I know that “Choice C” will not be the right answer.

July 13, 2024

What Do They Need to Know?

The harder Tom tried to fasten his mind on his book, the more his ideas wandered. So at last, with a sigh and a yawn, he gave it up. It seemed to him that the noon recess would never come….Tom’s heart ached to be free, or else to have something of interest to do to pass the dreary time.

— The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain

How did the river make me a teacher? Listen. It was alive with paddle-wheel steamers in center channel, the turning paddles churning up clouds of white spray, making the green river boil bright orange where its chemical undercurrent was troubled; from shore you could clearly hear the loud thump thump thump on the water. From all over town young boys ran gazing in awe. A dozen times a day. No one ever became indifferent to these steamers because nothing important can ever really be boring.

— Dumbing us Down, by John Taylor Gatto

I’ve been watching old episodes of Alone on Netflix, and it’s gotten me thinking (because thinking is something I can do reasonably well, unlike skinning squirrels and insulating log cabins with moss).

Watching these contestants and learning about their lives back home—the survival classes they teach, the wilderness tours they lead, the hunting and fishing they did with their fathers—makes me think about people I’ve known in my own life who have had radically different upbringings from me—people who hunted for whatever meat they ate; people who valued the wilderness more than they did the city; people raised in poverty; people raised in the church. They are curious people and knowledgeable people. But they’re curious and knowledgeable about things I know little about. And it’s possible they’d say the same thing about me. But the things I know are the things our school systems and our various sets of learning standards tend to privilege and prioritize, while the things these other people know are barely ever whispered inside a schoolroom. Why?

Is it that we think of their knowledge as old-fashioned and outdated—not important in our increasingly urban and industrial world? If that’s the case, why do we ask children to study poetry from past centuries whose people had far more in common with our rural cousins than they have with us city-dwellers? So much of the poetic imagery we ask our students to analyze is based on the natural world, with references to particular flowers, birds, minerals, leaves, and sounds. But how much is tactile, experienced knowledge and understanding of the environment prioritized as essential in school?

The people who make decisions about schooling are, by and large, people who enjoyed school and were successful in it. I think this is part of the issue. They pass on to the next generation the things that worked for them. If they liked reading more than getting their hands dirty, then reading matters. If they were okay with sitting still for long periods of time, then sitting still is the right way to learn. This year’s star students resemble last year’s, and this year’s outliers resemble last year’s, ad infinitum.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This isn’t as hopeless and hermetically sealed as I’m making it seem. Diverse voices do creep into the curriculum (slowly), and pedagogical reforms do creep into the classroom (slowly). But what school is for, and what knowledge and skills matter—those things are tightly held, and if you widen your circle of empathy, you can understand why some people feel their lives and their culture are left out.

If the skills and knowledge that make up a set of learning standards are the most important things—the most enduring things—then they should matter to everyone to whom they are meant to apply. Which is why they tend to be written broadly, and why efforts at creating a national set of standards, which would have to be even broader, have failed in our very large and very diverse country.

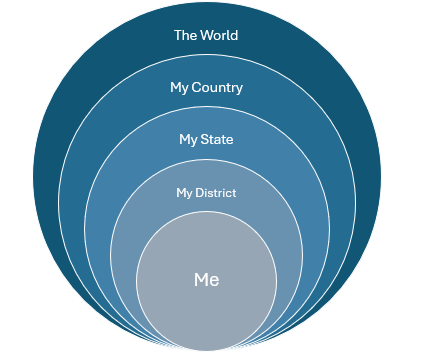

But that should be the floor, not the ceiling. Or, maybe more accurately, it should be the largest of a set of concentric circles. It is not the only circle that we should be dealing with.

When we design curriculum, we should be thinking of the largest world we’re trying to prepare our students to enter. And we have to think about the learning standards set for us by our state. But there should be room for variation and customization beyond that point. Even our smallest states are diverse. There are cities, suburbs, and rural areas. There are liberals and conservatives. There are deeply religious people and fiercely agnostic people. And even within those groups, there is subgroup variation and then, at the core, there are unique individuals. Each of those circles or rings is meaningful. And yet, we either ignore all of them except for the largest, or we agonize about “personalization” without thinking about anything that sits between the innermost circle and the outermost.

The twin goals of education should be to understand oneself and one’s world. But as you can see from the picture above, there are many worlds one has to learn about and live within—and their needs and values don’t always align nicely. Living in the world means understanding all of the variation within it and how to coexist respectfully and successfully with all of it.

The problem with buying, say, a U.S. History textbook from a national publisher is that the “state version” they create for your state will involve as short and limited a checklist of changes as they can get away with—for obvious reasons. It will include and exclude things as required, but it will still be a version of the national edition. It will be up to local teachers to help students get a deeper understand of the history and culture of their state and how that state sits within and sees the union of which it is a part.

But that’s just the start. They will also need to help students understand the town or city they live in and its relationship to both the state and the country. And they will need to help students understand the subgroups to which they belong and each group’s relationship to the larger population. And they will need to help students understand their weird, unique selves, and that self’s relationship to…everything.

It’s a tall order. No packaged, published curriculum can do all of that work for a teacher, and a traditional classroom and class period is a challenging structure in which to pull it off. But if we truly believe in providing equity as well as excellence—in respecting and valuing not only the “whole child,” but also the whole, diverse country—then we need to find ways to get there.

John Taylor Gatto, who launched the unschooling movement with his book, Dumbing us Down, says, “Nothing important can ever really be boring.” If we believe in the importance of what we’re teaching, but find some of our students to be bored, then something is getting in the way. Those kids are required by law to show up; they are not required to care. If we believe that our job is not only to help them know, but also to help them care, then we have work to do. And part of that work includes understanding better and caring more about the lives they live and the things they know before they ever walk into our buildings.

July 5, 2024

The Play Was the Thing

Here in the Roaring (20)20s, things change fast enough that it’s easy to say about old events, “that was back in a previous life.” I’ve certainly talked that way when discussing my long-ago. I am in the education business these days, and have been, exclusively, for 24 years. Before that, though, from the time I graduated college to the time my wife told me she was pregnant—roughly 15 years—the aim and focus and passion of my young adult life was to make theater. That was a very different life.

I wrote plays. I occasionally directed them. I served as Literary Manager for a regional theatre in Atlanta. I worked with an amazing group of friends in a small, off-off-Broadway theater company in New York City. For a while, I had a play produced somewhere every year—mostly by our own, little company. We had a good run for a few years. Good reviews. Dedicated audiences. But small companies that can’t pay their members aren’t the most stable things, and eventually, people peeled off to pursue other opportunities or leave the theater entirely. Left alone and about to become a father, I turned on the ghost light and left the building. Now I serve my writing compulsion here on Substack and with occasional mystery novels (and a science-fiction-y mystery coming…someday).

Up till now, the scripts of my old plays have existed only on my computer. But, you know…time’s wing’d chariot and all that. I’m not getting any younger. So I thought it might be nice—for my kids, at least, and perhaps for the people who worked on the productions back in the day—to put the texts together and publish them. Which I have now done. They sit on Amazon alongside my novels, in paperback and Kindle versions. If you enjoy my writing here and are curious to see a different aspect of it, seven plays await you, in two volumes.

The plays I describe below were all produced at least once (some of them twice; one of them more). They had productions in New York, Atlanta, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and at a theater in Norway. Some scenes and monologues were published in Smith & Kraus' Best Stage Monologues and Best Stage Scenes anthologies in 1993, 1997, and 1998.

None of them is perfect. I knew that at the time, and I certainly know it now, after rereading them to format them for publication. But they’re interesting, and they’re ambitious, and I think each of them has something to say and a unique way of saying it. I’m happy to see them in a format where other people can read them.

There are other plays—unproduced, untouched. They will remain in darkness.

First up is Collected Plays, Volume I: Original Works. As the title says, these are my original, full-length plays.

Here is what you’ll find:

The King of Infinite Space

In the ruins of an old prison at the edge of a landscape blasted by war, teenagers act out the story of the previous generation’s struggle for survival.

“It’s kind of neo-Brechtian and and kind of “Star Trek”-y and kind of funky-political.” New Yorker Magazine, Sept. 28, 1992

It’s a big, crazy spectacle of a play, with songs, masks, verse passages, a play-within-the-play, and all kinds of opportunities for extreme theatricality. It was my MFA thesis project, based on research on Brechtian and Asian theater techniques and on the allure of autocracy and the fragility of self-government. It has had the most productions of anything I’ve written.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

A young man inherits an old car from his activist parents and drags his best friend on a cross-country journey in search of meaning and understanding.

“Ordover’s expressionistic drama is a sort of New Age “On the Road” that mingles an inchoate spirituality with the throbbing impulsiveness of its Beat predecessor.…a veritable primer in Semiotics.” Los Angeles Times, December 16, 1994

“Ordover’s script is moving and lyrical.” Back Stage West, December 29, 1994

As the reviews said, this is a theatrical on-the-road story, a buddy story, a modern-day Huck Finn adventure, and a quest for enlightenment. While more realistic in its setting, it requires just as much chutzpah to pull off as The King of Infinite Space, since a production has to dramatize a car trip across the country and uses a small ensemble to portray multiple characters. There’s also some choral chanting of Walt Whitman to contend with.

Motherland

A teacher in a small Slovak town tries to free herself from old ways of thinking and living in the wake of the Velvet Revolution and the fall of Communism.

“One of the best new American plays I saw this season.” The Hudson Review, Summer 1996

“It is Ordover’s brilliant writing that steals hearts.” Washington Square News, March 22, 1996

I wrote Motherland after spending half a year teaching in a small town in Slovakia, a handful of years after the fall of Communism. It was a challenging time in my life, and an even more challenging time in the lives of the people I met there. This play was a love letter to them.

The Wind on the Water

A Jewish investment banker awakens on Christmas morning with the wounds of Christ, unleashing a religious and media frenzy that takes over his life.

“The play becomes partly an adventure story and partly a serious religious caveat, and it startlingly reminds us how the political and moral forces of millennialism can go spinning out of control.” New York Theater Wire, October 1999

This was the last of my plays to be produced—a story I had been thinking about and turning over in my head for many years, but had never dared to write. The approaching millennium made it seem timely and relevant, although apocalyptic thinking and the manipulation of people’s religious beliefs to gain power never seem to go out of style.

The second book is titled, Collected Plays, Volume II: Retellings. This volume includes three adaptations of ancient plays and stories.

Here’s what you’ll find:

Agamemnon

A queen, her son, and his teacher await the return of their king after ten years of brutal war. It’s a stripped down version of the Oresteia set in an unspecified day and place. The language is modern, except for flashes of prophetic trance-talk that echoes the original texts. It was written during the Yugoslavian civil war and reflects some of the angst of that time, as we watched ancient, ethnic conflicts re-erupt in ways that surprised us and seemed impossible to resolve.

Gilgamesh

The oldest story in the world, in which a king finds and loses a great friend, and then sets off in search of an answer to the question of eternal life.

“An extraordinary evening of beauty and terror.” Off-Off-Broadway Review, April 6, 1995

This is another big, theatrical spectacle. It includes songs and verse passages, and features gods, monsters, strange journeys, and a re-telling of the pre-Biblical flood story. The story requires big, bold, theatrical gestures, but the content is not for children. Ancient as it is, the Sumerian text is a remarkably tough and honest look at the meaning of life and the inescapability of death.

The Golem

In 17th-century Prague, a rabbi and his family turn to ancient mysticism in a desperate attempt to protect their community from approaching violence.

“A work of considerable passion and clarity, which addresses a problem that continues to breed war and hatred today.” TimeOut New York, May 8, 1997

The tale of a rabbi creating a living creature out of clay goes all the way back to the Talmud. Eventually, the legend adhered itself to a real, historical figure in 16th century Prague. There are many versions of the story (which may have influenced Mary Shelley in the writing of Frankenstein), including a 1921 theatrical adaptation in Yiddish by H. Leivick. I wanted to embed my version in the realism of its historical context, a time when change, enlightenment, and science seemed to be promising an end to superstition and religious hatred. We all know how that turned out. I think the play also has timely things to say about the necessity of defending yourself and the seduction of wanting to avenge the wrongs done to you.

That’s it. Seven plays in two volumes for anyone who might be interested in reading them. And, hey, if you like one and think you might like to stage a production…drop me a line.

June 29, 2024

Living and Learning Non-Linearly

Midway in our life's journey, I went astray

from the straight road and woke to find myself

alone in a dark wood.

—Inferno, Dante Alighieri (translation by John Ciardi)

Ah…life’s journey. Fun stuff. Kierkegaard tells us life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards. But what does he know?

I wonder sometimes: does “understand” mean there’s a shape and a meaning and a purpose to life that we can finally glean in its final moments? Or does it mean that in those final moments we realize there was never any meaning or purpose or shape at all?

It’s possible that the moments of our life are just moments—beads on a string—and that they don’t “add up” to anything. Stories and lives aren’t the same, after all. Stories have an arc and a shape that have been formed by an author. They build towards an ending that’s satisfying to readers because it resolves and completes all that has come before it. Lives are just…lives. Is our purpose in life to build towards a happy ending, or just to have as long and happy a middle as we can manage?

We seem to be addicted to stories, perhaps more now than at any previous point in our history. Life, love, politics, the news—scripted shows, unscripted but heavily manipulated “reality” shows—everything has to conform to the rise and fall of narrative structure. We must struggle. We must overcome. We must have a stirring soundtrack playing underneath the action at all times.

In stories, every action leads inexorably to the next action. In life, crazy shit has a way of just happening. If the laws of cause and effect were ironclad and reliable, we’d be able to predict every outcome of every situation. But we can’t. We make bets. And sometimes, even when the odds look really good, we lose. Random, crazy things happen in life, in ways we’d never accept in fiction. This is why writers who craft “based on a true story” narratives have to warp the true parts to make the story parts more satisfying. The guy who wants to meet the queen can’t just stumble blindly around the palace until he finds her bedroom (which is what actually happened); he has to case the joint, plan the break-in, and work with the finesse of a cat-burglar. In life, sometimes, the guy who doesn’t plan gets to meet the queen, and the guy who plans meticulously gets caught.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t make plans for ourselves and our children, or prepare for the future we want, Of course we should. I’m just saying we need to make room for the random and the unpredictable, and give them some respect. Maybe the good preschool gets your child into the good magnet school. But maybe it doesn’t—and a kid they meet in the regular old school becomes hugely important in their life. Maybe majoring in Business instead of Art makes a young graduate more employable. But maybe it doesn’t—maybe the investment bank snaps up the Art major and leaves the Business major at the curb, because this week, right now, they’re about to manage a big M&A project that involves art galleries, and they’d love to have a smart young analyst on board who has experience in art. When humans make decisions, instead of leaving them to algorithms, unpredictable and wacky things can happen.

Maybe our goal should be to cast our net widely, pull in as much knowledge and experience as we can, and not worry so much about what it’s all going to add up to. Maybe the act of learning and living—seeing cool things, doing cool things, learning cool things—is what it all adds up to. The “crazy shit” that gets edited out of a story because it hinders forward narrative progress might actually be the best and most interesting parts of life. And things that appear at first to be side streets may turn out to be the most important parts of our journey.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I was an English major in the early 1980s, and I studiously avoided thinking about what it would prepare me for, mostly at the encouragement of my parents, who had been forced to behave otherwise by their parents. I was told that the purpose of going to college was to become a well-rounded and well-educated human being, and that I could worry about career choices afterwards. So, that’s what I did.

Of course, it being the early 1980s, few of my friends were thinking the way I was. Yuppies were ascendant, and “Greed is Good” became the rallying cry two years after I graduated. I spent most of my spare time doing theater, which I intended to pursue after graduation, though I had no idea how that was going to happen. I discovered at the end of my senior year that most of my theater pals had other things in mind. They went off to law school or business school or entry-level jobs in big corporations, leaving me looking around in a panic, saying, “Was I supposed to have a plan?”

This is what led me, in desperation, to respond to a late-night TV ad for a six-week bartending program that guaranteed job placement. Yes, I am a graduate of the Georgia School of Bartending. And I did get a job upon graduation, at a suburban ribs restaurant and lounge. It was a nightmare, and I didn’t last long. But the day I was fired, I got snapped up by my college’s theater department to serve as their new Artistic Director’s assistant. I happened to stop by the office the day I was fired. It happened to be the day that new director had arrived from England. I happened to be available. And so, I ended up working there for the next two years, before I went off to graduate school to get my MFA in theater.

When I came back, I did volunteer work for a local theater as their literary manager, reading all the plays no one had asked for and no one had any intention of producing. I thought that was my entry level” job in theater, preparing me for the rest of my life. Meanwhile, I needed a paying job, so my mother hooked me up for an interview with a friend who was the headmaster of a brand new, very alternative high school. Because it was private, it didn’t matter that I didn’t have a teaching certification—or any experience. All the headmaster cared about was that I knew literature, could write well, and liked kids.

Eventually, I ended up leaving teaching to run a small theater company. Then, when I needed a better-paying job, I worked for a small but growing division of an education company as a curriculum writer. And even though I walked in with zero business experience (beyond ringing up drinks at the bar), I discovered that years of directing plays had prepared me well for managing creative and collaborative teams, and I was able to grow and rise quickly within the company. I happened to have what they happened to need at the moment when they happened to need it and not have it.

Thus began my career in education, which is now in its 30th year.

Master plan? Random chance? You tell me.

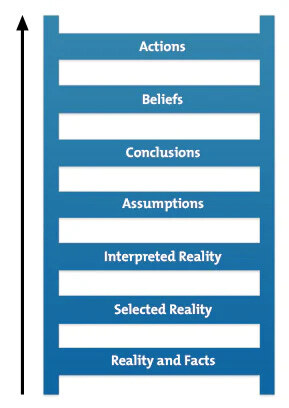

Personally and professionally, I am the sum total of the things I’ve learned and the things I’ve done—the choices I’ve made and the choices I’ve run away from. Was there a map somewhere, leading me inexorably to where I stand today? I don’t think so. But there was certainly a personality or identity informing my actions and choices from day to day. I did what I did because I was who I was—sometimes with a plan in mind and sometimes in response to a random chance. So maybe identity plus opportunity creates the map. And maybe there’s a virtuous or vicious cycle involved, where identity informs choices and choices reinforce identify, on and on throughout your life—in ever-tightening, ever-more-restrictive circles.

This reminds me of the “ladder of inference” idea, where your biases limit your intake of data and the conclusions you’re liable to reach—which further limits the data you’ll be willing to consider next time. We think that putting on blinders and being single-minded helps us focus on chasing our goals, but maybe, in reality, those blinders get tighter and tighter over time, and our goals becomes smaller and smaller, with any other options being ruled out by becoming invisible to us.

Maybe there’s another way of looking at it. Instead of climbing a ladder or walking a road or aiming at a target—all of those linear ways of thinking—maybe we should be more circular, more holistic, more…as my parents said when talking about college…rounded.

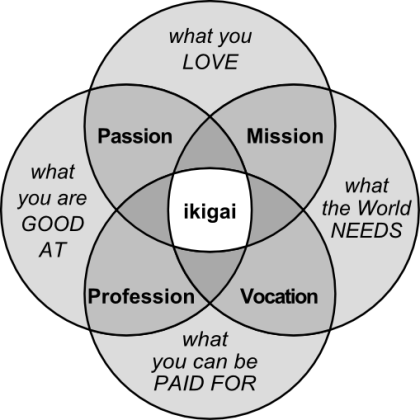

There’s a Japanese concept called Ikigai, which translates loosely as, “the reason why you get up in the morning.” It’s not depicted as an end point in a linear process. It’s usually represented by a Venn diagram:

I think that’s very interesting. It’s not an end-point; it’s an intersection-point. But “pursuit” is still part of the dialogue. I’ve heard people talking about Ikigai as a way of helping you think about what career you should look for: find the one thing that does all of this for you, and you’re golden. Another goal; another destination. But maybe that’s not possible for everyone. Maybe the goal shouldn’t be to “get” anywhere. Maybe the goal should be to make sure that each circle is represented in your life, is present in your life somewhere. Maybe a job doesn’t have to connect all of the things; maybe it’s your whole life that does.

The world is wide and weird and hard to predict. Something in our peripheral vision or down a side street could be the thing that ends up being most valuable to us. As Kierkegaard told us, we can’t really know what the journey means until it’s all over…if it means anything at all, beyond making a journey.

If that’s true, maybe we don’t actually awake in a deep wood, midway through life’s journey, having strayed from the straight path. Maybe the waking up is when we realize there was no path in the first place.

June 21, 2024

Own the Room

An adventure is only an inconvenience rightly considered. An inconvenience is only an adventure wrongly considered.

— G.K. Chesterton

For a couple of years, I traveled around for work, speaking and leading workshops on a topic I called, “Teaching for the Stretch,” which was all about engaging students in “conceptual play” to help them reach higher and deeper levels of understanding. Part of that approach involved asking more open-ended, speculative questions to give students time to get their “hands” on the academic content and do interesting things with it. Whenever I spoke with teachers and principals, I heard them express fear that truly open-ended questions might pull classroom discourse far off topic and away from the lesson as planned. This was the place on their map that was marked, “Here be dragons.” Go no further; turn back.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In many schools, we demand that teachers write lessons according to a particular format and turn in their plans every week. In many schools, those lessons must hit particular targets at a particular time to align with an overall pacing plan for the school year. How could a clown like me tell them, in good faith, to ask more “why,” “how,” “what do you think,” and “how do you know” questions that don’t have simple answers and eat up tons of class time? How could I even suggest posing questions like, “what if we looked at this in a different way?” Wasn’t that just opening the door to chaos, disorder, and the Death of the Plan?

Well…possibly. But I think we can open the door a little, just to get some fresh air in the room, without inviting chaos for dinner. We’ve given teachers pre-service teachers many strategies for classroom management, but I think we’ve shortchanged them on a crucial piece of the puzzle, which has to do with managing discourse in ways that are inviting and engaging rather than limiting and punitive.

Whether we’re talking about a traditional, direct-instruction model or something more open and inquiry-based, the teacher is the overall manager of the time and space set aside for instruction, and instruction is a living, breathing, shared experience. It’s not just a delivery of information; it’s a conversation—an exploration. In some ways, it’s a performance, and no performance, even a monologue, is purely monologue. We’re always talking to someone, reacting to someone, feeding and being fed by someone. It’s interactive, even if the reaction you’re mandating is silence. But it’s a shame if you stifle reactions from your “audience” beyond what you’ve already decided you want from them. After all, whatever happens in that room, it’s allegedly being done for their benefit.

We often talk as if our time were the precious commodity, as if students were creating obstacles to what we were trying to accomplish. That mindset suggests (whether consciously or not) that students owe us their attention, and that when they become distracted, it’s an insult to us. But what if we thought about their time as being more important? Our students are legally mandated to attend our classes, but they can certainly absent themselves mentally if they’re not engaged. What if we acted as though their attention were a gift that we had to earn? What if we thought about classroom management the way an actor or a stand-up comic thinks about their time on stage? I’m not saying we should entertain and amuse students every second of the day. Learning is difficult, and we shouldn’t have to pretend that it isn’t. It’s work. But the teacher still needs to “own the room,” as a performer might say—not for her own attention and ego gratification, but to be able to shape and manage the entire experience for the benefit of the class.

How do actors or other performers learn how to “own a room?” For a start, they learn how to control and use their voices and bodies. Actors spends years getting voice and movement training to help them embody a wide range of characters and emotions. They learn how “body language” communicates different things to viewers—how crossed arms convey weakness, how spread legs convey strength, and so on. A lot of it is obvious enough to be cliched, now, but it’s still true. And all of it is for the audience’s benefit—to elicit responses and reactions and thoughts from them.

More: Comics learn when to stand still, when to prowl the stage, and how to use thier voice and their microphone to create all sorts of vocal effects. They learn through long, hard experience where a whisper is funnier, or when a pause makes the laugh bigger. They learn how much information a set-up needs in order to make the punchline land. Good trial lawyers learn similar techniques. During direct examination, they will remain seated or stand to one side to let the witness talk directly to the jury, but during cross examination, they’ll place themselves between the witness and the jury, so that their questions and commentary (and side-eye) become the filter through which the jury experiences the witness’ testimony. It’s subtle, but it matters. It shapes the audience’s experience.

Veteran teachers pick up similar techniques—when to get quiet and when to raise their voice, when to move around the room and when to stand still—but by and large, we make teachers learn these things on the job, haphazardly, and we don’t give any guarantees that they’ll learn them at all. These things are not part of the teacher training curriculum; they’re just skills you pick up along the way if you’re lucky. And that’s a shame. We sometimes say that everything a child does in a classroom is data, but it works the other way around, as well. The way a teacher dresses, speaks, and moves speaks volumes to children, and all of those things can either support or undermine the academic work the teacher is trying to do.

Imagine if part of a teacher’s training included the purposeful and strategic use of voice, movement, and body language. Imagine if novice teachers learned techniques for holding their student “audience” in the palm of their hands and earning their attention and engagement. Imagine if teachers could approach a class period as an interactive performance, a carefully and purposefully shaped period of time that has a beginning, middle, and satisfying conclusion. That’s what our best teachers do already. If the skills are similar to those learned by actors and trial lawyers, why can’t we “bottle” that stuff and teach our cadets how to do it?

There’s another crucial skill that speaks directly to the “teaching for the stretch” idea, that need to breathe air into a lesson to allow for questioning that probes and pushes a student’s learning. I’m talking about the skill of improvisation. Veteran performers know that every night holds the potential for a hundred disasters—and that every disaster can be an opportunity. They learn how to roll with the punches and keep the show moving. Athletes know that diagrams drawn in the locker room are lovely ideas that can be scuttled by reality in a split second. They know how important it is to be able to analyze a dynamic situation quickly and take the appropriate action. Dwight Eisenhower said, “Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” Mike Tyson said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” There’s a lot of very different lived experience embodied in those two sets of very similar words. They must be on to something.

Teachers need the same set of skills, but, again, we rarely teach them explicitly. We should. “You’ll get the hang of it” is an unreliable way of preparing a professional for the job. No matter how perfect and well-crafted a lesson plan may be, reality has a way of throwing curve balls at you, and if you don’t learn how to hit them, your first few games are going to be trouble.

How does this relate to stretch and conceptual play? I think it has to do with the kinds of questions we ask and the kinds of answers we expect. If our lesson plans set us up to ask only closed, fact-oriented questions, we can estimate lesson time fairly efficiently. We ask the question, we hunt for who has the right answer, and we move on. We get what we look for—what we expect. We miss what we don’t think to look for. But if we’re more interested in the wrong answers and what they tell us about the way students are thinking, it’s very hard to know how long that kind of exploration may take, or where a more open-ended question might take us. If you don’t know what kind of answer you’re going to get—or what kinds of questions students might ask of you—then you need to be prepared to change gears and respond. Response is the first step in genuine dialogue. Refusing to respond—just because it takes you off track— betrays a lack of respect for students and for real learning. “We need to move on,” shows students that your time and your plan are more important than their needs. “Let’s unpack that and see where it leads,” should be a joyful, and common, classroom experience.

So how can we help teachers be prepared for the curve balls and know how to respond to them? This is where training in improvisation could come in handy. Improvisation teaches a wide variety of strategies for being in the moment and being available to respond to whatever gets thrown at you. Some of the techniques you learn include Agree and Add, which is also known as Yes, And. We’re often trained to say No when we get thrown a curve ball—or, at most, Yes, But: “Yes, that’s an interesting point, but that’s not what we’re talking about today.” Improv teaches you to listen to and then accept the things that get thrown at you—and then build upon them. It gives respect to the thrower of curve balls (or, to be kinder, the student questioner) and takes seriously what they have offered. It teaches us to avoid rejecting the things we haven’t planned for, just because we didn’t plan for them—to accept them and find a way to use them in our teaching. It teaches you to be ever on the lookout for the “teachable moment,” and then make the most of it.

Improv teaches you to explore, together with your partner, whatever you’ve found—to dig into it and ask questions about it. What’s in there? How does it work? What else does it lead to? These are all terrifying questions to a teacher who is trying to re-route a student away from a tangential question and back to the main idea. But if we believe that tangential lines of thought are often where students become truly engaged—and that those tangential questions can reveal how a student is thinking about the core lesson material—then we need to have strategies for dealing legitimately with them, not dismissively. Every one of them can be a teachable moment if we know how to make use of them—if we’re ready to change our plan and engage with the moment we’ve been given.

A blog post from Mindshift talks about the power of improvisation for students as well as teachers, saying about students that “improv chips away at mental barriers that block creative thinking…and rewards spontaneous, intuitive responses.” Quora has an interesting discussion thread on the topic, as well.

Every great athlete and soldier knows that all plans are provisional; that reality intrudes in surprising ways. We know it, too. So why don’t we meet the challenge head-on and help our teachers-in-training build the skills they’ll need to deal with the crazy curve-balls that will absolutely, without question, get tossed at them?

As the old Yiddish expression tells us, “Man plans; God laughs.” If we know that the universe is liable to laugh at our best planning, maybe we can learn to laugh along with it.

June 15, 2024

Fixing Our Incentive Structures

Introduction

IntroductionOne of the things we’ve learned over the past eight years is that a lot of what we’ve taken for granted about the way our world works is based on norms, not laws—un-forceable and unenforceable expectations of good behavior. We operate on the honor code far more often than many of us realized.

That’s not likely to change. There may be places where legislation could be helpful, but a lot of what we need are changes to “incentive structures,” the sets of ordinary, informal rewards and punishments that guide our everyday behavior. We can’t legislate every single aspect of our life, and we wouldn’t want to.

Where could we think differently about our incentives and how they drive behavior? Here are a few ideas.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In EducationI wrote about this issue last year in reference to ChatGPT and what its effects on schooling might be. As I said back then:

If students believe that the most important thing is getting an assignment completed and getting a good grade, they will use Chat as they’ve used dozens of other tools throughout the years—as a way to cut corners or cheat. That this is the most predictable result says more about our values than it does about the technology.

The easy-but-wrong response to a new threat is to legislate it away. In schools, that means banning books, devices, tools, etc. Some schools and districts are doing exactly that, but I think it’s always losing a battle. And it doesn’t speak to the real problems. When it comes to plagiarism and cheating, the incentive structure in our schools tells students that scoring matters more than learning. So, how do we change that incentive structure?

The most radical thing we could do is get rid of grades and rankings entirely, but I don’t see that happening, ever. The second most radical thing would be to assign only a single grade, at the very end of the course, representing final mastery of the material. I don’t see that happening, either, although I wish it would. Some students have to work their way towards learning; it takes them a while to “get it” and succeed. Is that really something we should punish or downgrade? Because that’s exactly what we do, while rewarding most lavishly the students who “get it” on Day One and skate easily through the rest of the course. Why should I be punished if I start the course getting poor assignment grades? Isn’t the end result what matters? Why do we have to average all the grades earned during the course? Aren’t we actually punishing effort in this structure? Do we really want to be telling young people that the way they start something will forever hobble and haunt any future progress they manage to make? That doesn’t sound very “American Reinvention” to me.

If we can’t change the entire grading structure, we can mitigate against its harms in smaller ways. One way is to give students opportunities to revise work and retake tests as often as they want to. I would rather tell students that every one of them has the ability to get an A grade on a paper—and that whether they get it or not depends entirely on them and how much work they’re willing to put in. Here’s the scoring rubric: here’s what you’re aiming for. I will give feedback at every attempt, to guide you towards a better score. You can stop at one draft or push through to three or four—as many as it takes to get where you want to go. You decide when to stop. You decide what’s “good enough.” If you stop short of the A grade, that’s your choice, not my semi-arbitrary, one-moment-in-time judgement.

Some people object to this idea, saying it encourages students to be lazy and disorganized, to avoid studying for tests or turning in work on time. Maybe. Maybe, for kids who are already in a position to deliver on-time. But even for them, they’ll eventually figure out that the less up-front work they put in, the more work they’ll have to put in later, to get it right.

Either way, which structure do you think better prepares students for success in life and work—the one I just described, or a year of unannounced pop quizzes? I don’t know about you, but I haven’t had a pop quiz in a very long time.

Another way to incentivize actual learning over corner-cutting and cheating is to make demonstration of skills and knowledge more public than private. Have students stand in front of peers—and sometimes adults from the school and the community— to talk the talk and walk the walk. Let people engage them in conversation about what they know and what they can do. This doesn’t have to be a scary inquisition. If students have done the work, it can be very exciting and give the students a lot of pride over what they’ve accomplished. At the end of high school, where I’ve seen it done, it can be a genuine rite-of-passage, where adults accept young people into their community.

In Social MediaMy wife and I were talking about this the other night. How can you incentivize people to behave better online without limiting or chilling their speech? Some people talk about getting rid of the ability to post anonymously, but that’s tricky—there are people out there who can’t be honest without hiding behind a mask, and they may have important things to say.

Here’s an idea we came up with. What if the platforms used AI to assess the text of each post for its tone, and then added some kind of flag or marker based on its kindness, supportiveness, or helpfulness vs. its cruelty or mockery? Maybe it’s just positive vs. negative vs. neutral. This might not be meaningful for an individual post, where the tone is pretty obvious on its own—but an overall percentage score tied to the poster’s profile could be really informative and tell you whether or not this is someone you actually want to engage with. It would also be useful and revelatory to see what your own percentage is. (“My stuff is only 62% positive? I thought I was much nicer than that!”)

What would this change? First, it might make each of us a little more thoughtful about what we put out into the universe, whether under our own name or under a pseudonym. We don’t want a system that stops us by force, but we should want a system that makes us pause and think a little before acting. Right now, the algorithms incentivize outrage, because high and hot emotion leads to more engagement. But is that really good for us? I think we would want kindness and helpfulness to be better incentivized in any places where we meet in public—or at least for it to have a fighting chance.

Better incentivized, maybe, but not required. Sometimes we want someone to say something outrageous and mean in public. Sometimes we need to vent, and we want others to hear it (and we enjoy hearing others doing it). That’s healthy. Criticism is important. Figuring out how to evaluate when criticism is healthy and supportive rather than demeaning and cruel would be a challenge, but not an insurmountable one, I think.

Some people might want to ban and utterly prevent the demeaning and the cruel. That’s where we are right now. What constitutes hate speech? What constitutes protected speech? I’m not talking about any of that; I’m simply talking about identifying kinds of speech. Which is tricky enough, I admit—and something many people would object to. But I feel like, if angry venting is you want to do, every post, every day, we you ought to be willing to own that. If I use my social media to spew obscenities at the world, I shouldn’t be coy about it or take to my fainting couch if my profile says something like, “98% Negative.” No one’s going to stop me from saying something nasty, but if I choose to say it, it ought to…count. Somehow. It should be noted.