Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 9

March 23, 2024

The Platypus Would Like a Word

Everyone knows at least something about the book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (maybe only the title). But fewer people are aware of Robert Pirsig’s follow-up book, called Lila, which came out decades after Zen. This book is about a boat trip down the Hudson River, rather than a motorcycle trip through the West. Once again, Pirsig talks about Quality—what it means and how we can rank and classify it. The author totes a bunch of shoeboxes around with him, filled with index cards that he’s constantly reshuffling and rearranging, trying to find some kind Unified Field Theory of what “good” means. It’s interesting and funny and maddening and painful, just as his earlier book was (assuming you find ideas and the people who care about them interesting).

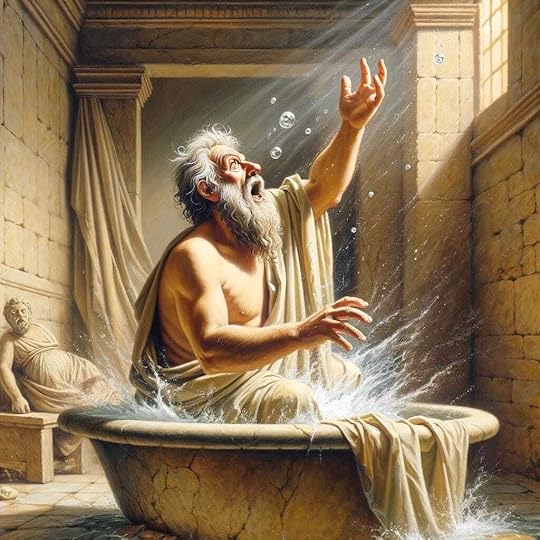

There's a section where he talks about the early days of scientific classification. He describes how scientists first came up with their categories of mammal, fish, reptile, and so on. And he describes what happened when those scientists encountered the duck-billed platypus—which, as you may know, doesn't fit neatly into any of those categories. It’s a mammal, but it lays eggs. It’s also venomous, like a snake, but, you know, different. The first scientists to examine a preserved platypus body apparently thought it was a practical joke—a fake animal stitched together from the carcasses of several “real” animals. But it wasn’t, and they had to figure out where it fit. But it didn’t fit. So…did the scientists go back to the drawing board and re-think their lovely system? No, they just decided that the platypus was wrong, and assigned him to his own, special place—outside.

See, the system—their arbitrary, artificial construct—that was right. It was the living, breathing creature that was wrong. We can only imagine what the platypus might have wanted to say in response.

I feel like the world of arts education falls victim to this platypus syndrome. I'm not the first person to suggest that our school system classifies and categorizes knowledge ways that are alien to how people live their lives outside of school. We've tried to convince generations of children that history has nothing to do with today, and that literature and science shouldn't be talked about in the same room. We've allowed them to think that that some people simply "get" math and others simply don't (as I mentioned last week). And we've allowed them to think that art is optional: a subject that is not academic, not essential, and not worth prioritizing when the budget axe falls.

Children in elementary school don't have this problem. They're generalists. They learn about Native Americans and then they go make an Indian village out of pipe cleaners and corkboard (well…these days they probably animate it in Blender). They don't care. Art is simply one way of understanding the world—one way among many. Children get it, but we've forgotten. We treat art as a specialization in middle and high school, and not a very important one. If older kids even have an arts program in their school, it's usually a separate, set-apart world, an “elective,” the point of which is…well, I don't know what the point is meant to be. To study art for its own sake, I suppose—to learn the techniques, respect the discipline, and clean the brushes when you're done.

If we do a poor job of answering the “when am I going to need this” question in Algebra, we don’t even bother answering it in arts classes. There was a time when you could argue that learning how to play a musical instrument or paint a picture was important because, pre-electronics, you needed ways to entertain and amuse yourself and your family. Even that reason is dead for most people—we consume far more entertainment than we create for ourselves using classical techniques, and the 10,000 videos that kids create and share don’t seem to be part of formal art instruction in most schools. Which leaves us with “art for arts sake.”

I think “art for art's sake” is nonsense, especially in our schools. Art doesn't have a sake—only we have a sake. Art is for life's sake, or it's nothing. And in too many schools, it is nothing. It's considered a frill—a luxury. And for those of us who consider ourselves artists of one kind or another, this is our fault, because we've allowed ourselves to be defined at the margins—when in fact we should be the vital center, the beating heart of any school. Art isn't just a way of expressing our emotions. It's the place where everything we study meets. Art is history, math, science, math, all rolled up together. It is, to a large degree, what humans do with what they have learned. And it has so much more to teach us than we allow into our schools.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

For example—one example—what does it mean that, at a certain point in European history, painted representations of reality stopped looking two-dimensional and took on depth? Where did perspective drawing come from? What's the science behind it, and where did it come from? Why did painters in the West suddenly understand how to do that, when they never had before? Why did it happen as we moved out of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance? And what did that shift, along with all the other seismic shifts of that era, do to the way people understood their world?

These aren't small questions. If you were going to teach teenagers about the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, why wouldn't you want them to look at these paintings and how they changed? Why wouldn't you want them to study cathedrals and illuminated manuscripts, and how they changed? Why wouldn’t you want them to bring history and science together and apply them to art (or vice versa)? Isn't that at least as effective a way of showing how a world evolves as reading about King X and War Z? And what if—here's a radical thought—what if students could actually make some of that art while they were studying the time period? I mean teenage students, here, not little kids. What if they had the chance to discover, tactilely, just how laborious a task it is to illuminate a manuscript by hand, and what it must have meant—physically and emotionally—to move from that world into a world with a printing press? Why not have theatre classes stage scenes from the Medieval mystery plays and then a scene from Hamlet, to explore how “three dimensional” drama was becoming at exactly the same time? Why wouldn’t you want their hands to understand what their minds were learning?

The art we create—and the way we go about creating it—can tell us so much about the world we live in, past and present—our beliefs, our values, our dreams, our nightmares. It seems incomprehensible to me that we've allowed the arts to be defined as window-dressing for suburban schools—pretty to look at and a great selling-point for parents looking to move into the neighborhood, but utterly without weight or consequence. Artists have been placed outside everything that is considered important in the world of school.

I used to get angry at school districts for thinking that the arts were tangential and disposable, but I don't get angry at them anymore. They're following our lead, as artists. We've allowed ourselves to be defined this way. When we enter the schools as teachers, we don’t fight for the centrality of what we do. Too many of us hunker down in our rooms and teach a hermetically-sealed curriculum that is all about making the art, not about why the art matters and how it can enrich what’s happening down the hall.

If we want school to matter, we should make the arts in school matter. Connect them in meaningful ways and students will stop asking why what they’re learning is important and when they’ll ever have to use it.

The platypus couldn't fight back—but we can.

March 16, 2024

Math and Me

Math has never been my friend. I was one of those kids who was allowed to grow up saying, “I’m not really a math person,” never questioning or challenging whether that was a sane thing to say. But the adults never seemed to question or challenge it, either. You can bet they would have pitched a fit if I had said, “I’m not really a reading person” or “I don’t do reading.” But when it came to math, people just shrugged and said, “Yeah, I get it.”

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I don’t know when or why it started. I remember playing with Cuisenaire rods in early elementary school, when those “manipulatives” were still relatively new and allegedly revolutionary. But I have no memory of using them in ways that led to “aha!” moments for me, or built my conceptual understanding of how numbers worked. All I remember is stacking them to make multi-colored ziggurats.

I do know that by 7th grade, math avoidance had set in. I was part of another allegedly revolutionary reform effort, in which we took our English, Social Studies, and Math classes in adjoining rooms, and then had a period every day called “Workshop,” in which we did project-based “contract” work across the three subject areas, and could wander from room to room to get help from whichever teacher we needed. I don’t remember doing anything interdisciplinary. In fact, I tried hard to pick only English projects and avoid math. And I got away with it.

Why did I want to avoid math as early as 7th grade? I have no idea. But it was definitely a language I did not speak fluently. In fact, as I wrote that last sentence, I suddenly remembered trying to memorize my multiplication tables in 4th grade, and how it (and the reward of being taken to McDonalds) eluded me for months, until I was one of the last kids in the class to pass the finish line.

When I think about my math education—in any of my years of schooling—all I can see is memorization of facts that quickly slipped from my mind, and application of algorithms and processes that I didn’t understand but dutifully executed. When they worked—yay. When they didn’t, I had no idea why. I did what was asked of me, but I never got it. Or knew why I needed to.

Until 8th grade. In 8th grade, I was able to take a self-paced math class. Yes—as a child of the 1970s, I progressed through one Bright Progressive Idea after another, every one of which was picked up for a short time, played with, and then discarded. And because this was the 1970s, “self-paced” meant that I sat with a portable cassette tape recorder and listened to someone teach the chapter while I followed along and did my work. What was revolutionary was that when I didn’t understand something, I could stop the tape! I could stop it whenever I needed to, and rewind it, and listen to it again, as many times as I needed to. No one else had to know. I didn’t have to hold the class up to get my questions answered. When I finished a tape, I took it up to the front of the room and exchanged it for the next tape. If the taped instruction didn’t make sense to me, even after multiple repetitions, I could go work with the teacher, one-on-one. It was glorious. It was the one year when I did well in math and liked it.

And then I went up to high school, and took a traditional Algebra class, and commenced to fail.

Did I say to myself, while struggling through Algebra, anything like this?

“Gee, I wish I could do this the way I did math last year, because that made sense to me, and it worked. This school system is letting me down by not letting me learn in the ways that work for me as an individual.”

God, no. What I said to myself was, “Guess I suck at math after all.”

And that was what I said to myself about math deep into my 40s.

One day, while working for Education Company #1, I found myself on a plane heading to California, where I was being sent to train a group of sales reps on a new, middle-school math intervention program. Why they had dispatched me to do this job, I have no idea, but there I was, on the plane, reviewing the lesson that I had been given to use as a demo. The lesson was about mental math, and it was using percentages as an example of how anyone could do calculations without paper and pencil. “Anyone can find 73% of a number in their head!” the lesson crowed, and I said to myself, “Like hell.” But I read on.

“You can find 50% of a number in your head, can’t you?”

And I said, “sure.”

“You can figure 10% in your head, right?”

“Uh huh.”

“And if you can figure 10%, you can figure 1%. Right? Right! So: what’s 73%, really? It’s just 50 + 10 + 10 + 1 + 1 + 1.”

Now, friends, if you are not a math-phobe yourself, you may not understand how strange and revelatory this moment was for me. But there I was, in my 40s, being given permission to think about numbers in ways I had never thought to do—had never been taught to do—ever in my life.

The idea that you could pull numbers apart and put them back together in different ways—that you could stretch and manipulate and play with them…no one had ever talked about numbers like that in my life. I was raised to wave my wand in one particular way and speak my spell in one particular way, and hope that the magic worked. This little demo lesson changed the way I thought about math as an academic discipline, and the way I thought about my relationship with numbers.

This is why I love people like Jo Boaler, whose book, Mathematical Mindsets, does a lovely job of showing how to build real, genuine number sense with children in playful, creative ways. It’s why I love the Standards of Mathematical Practice that were laid out by the Common Core State Standards. They encourage teachers to focus not only on factual knowledge and procedural fluency, but also on all the various ways in which we use and manipulate numbers and mathematics. This is how you teach math as a language, not simply a set of tasks.

As an English teacher, I knew that children had to learn how to decode the symbols of language and attach meaning to them—and that comprehension of written ideas was not possible until students achieved “automaticity,” meaning that the decoding had become automatic, and that children were reading words and sentences instead of sounds. The more information we can chunk and move from working memory to long-term memory, the more working memory we can free up to handle higher-level, more complex tasks.

I understood this in English. Why did no one ever talk about math the same way? Because math is the same: you do need to memorize your number facts so that you can call them to mind quickly. You can’t solve complex equations if you’re still trying to remember what 6 X 7 is. You can’t think about complicated relationships among angles in a geometric figure if you can’t quickly call to mind what those angles have to add up to. You need to develop automaticity in the language of math in order to be able to comprehend a “sentence” in math and make meaning of it.

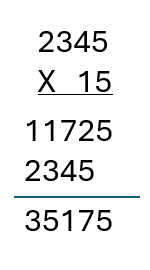

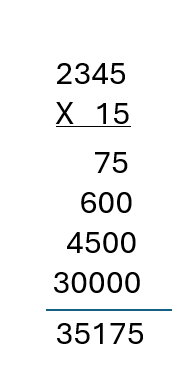

One final example: when we were deep in the throes of Common Core (yet another revolution that was well-intended, poorly understood, clumsily implemented, and then hastily abandoned by many states), I came home one day to find my wife and my 5th grade child in agony. The kid was struggling with homework, and it had reduced both of them to tears. I took a look at the equation they were struggling with. It was a multi-digit multiplication problem—4 digits multiplied by 2 digits—easy-peasy. Something like this, say:

My wife had been trying to help our child work through the problem in the traditional way we all learned, where you multiply each digit of the first number by one digit from the bottom number, and then do it again with the next digit, “carrying” when the result needed more than one number.

But the kid had resisted, saying, “That’s not the right way to do it! My teacher says we’re not allowed to do it that way anymore. She says we have to do it like this.” And he pulled out an example they had worked through in class, which would have required solving the new problem like this:

“What the hell is that?” my wife said.

“I don’t know!” the kid said. And then they were both crying.

Enter me. And because I had been dealing with this stuff at work, I recognized what was going on. The teacher didn’t want them to multiply 5 by 5, and then 5 by 4 and then 5 by 3, and then 5 by 2, and then do it all again, multiplying by 1. She wanted them to multiply 5 by 15, and then 40 by 15, and then 300 by 15, and then 2000 by 15. Because that’s what was actually happening in the equation. And while the old process works, and is faster, it doesn’t reveal how those numbers work together. It doesn’t remind you that the 2 up top is really 2,000. The second method shows you what is actually happening—it helps you understand place value, and what a number like 2,345 actually means. You’re visibly unpacking what’s happening in that multiplication. Whereas, in the traditional algorithm, you’re just learning how to wave the wand and speak the spell.

Which I still do. Which we all do. Magic spells and algorithms are super-helpful!

The teacher’s mistake was to say, “You can’t do it the old way anymore,” because that was absurd. All she was doing was substituting one meaningless procedure for another. The whole point of the alternate procedure was to help build number sense. Once it’s built, by all means go back to the easier, faster way of doing things. Why wouldn’t you? At least then, when you’re using the traditional method, you might actually remember why you’re “carrying” a number during the process.

You can’t build thinking through thoughtless procedures. All you can build that way is compliance. I know this to be true, because I was a very compliant math student, and a profoundly thoughtless one. I did things every day, but rarely understood what I was doing. And I was allowed to move through school and into adulthood saying, “I don’t do math.” Which is lunacy, because we all do math and we all need math. Math is a language we use to solve certain kinds of problems in our life, and why should anyone be allowed to blithely wander into adult life deprived of that language?

The balance between doing it and getting it is badly out of whack for too many students. And if they don’t “get it,” day after day, year after year, it’s hard to make the case that “doing it” is worth their time.

March 9, 2024

Climbing the Pyramid

When we wring our hands and worry about what students know and what students can do, we often take a very binary approach: they either know or they don’t know a fact; they either can or can’t perform a skill. It’s a well-known way of talking about student learning, but it doesn’t get to the heart of what young people need in order to be successful adults in our world.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There are three interesting frameworks that illustrate how learning progresses and highlight the fact that we spend most of our time obsessing over the most basic levels, ignoring or throwing up our hands in helplessness when faced with the higher levels.

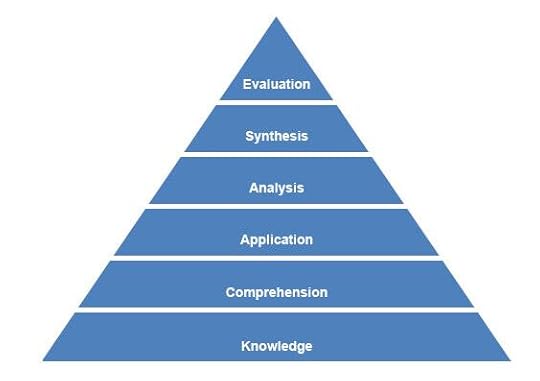

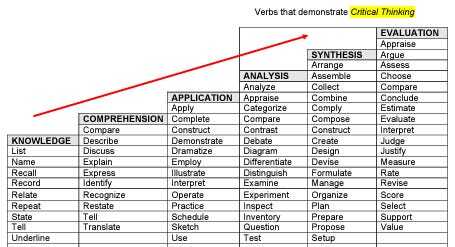

Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning, published in 1956, proposed a pyramid of learning outcomes, with basic knowledge and comprehension forming the essential base of the structure, moving up through application and analysis to a peak of evaluation. The goal, to Bloom, was the ability to be able to synthesize discrete pieces of information. and then evaluate and judge what makes sense, what is right and wrong, and what is useful in life.

This handy chart matches each stage of the pyramid with the kinds of verbs that teachers might include in lesson objectives. It highlights the problem we face if we remain focused on the lower two or three levels of the taxonomy. Think about what kinds of lessons—what kinds of assignments—students might be asked to engage in when focused on the verbs in each category:

Far too much of what happens in our schools involves tasks that require statement, recall, repetition, description, explanation, and basic application. Those are fine places to start building understanding, but if we want students to be able to use their knowledge in interesting and unpredictable ways out in the world, we need to give them opportunities to do things like analyze, debate, inspect, question, design, propose, appraise, evaluate, judge, and create. Creation is so important, in fact, that when the taxonomy was revised in 2001, it moved creation to the top spot on the pyramid.

Norman Webb’s “Depth of Knowledge” (DoK) framework, published in the late 1990s, is another way of looking at the same issue. Webb proposed four levels: Recall and Reproduction; Skills and Concepts; Strategic Thinking; and Extended Thinking. You can see how those four levels align with Bloom’s six. An interesting addition is the idea that the highest levels of cognition require more time. In fact, one major difference between activities in Level 3 and Level 4 is the amount of time required to complete the activities.

A third framework, one that I particularly like, is called Structure of Observed Learning Outcomes, or SOLO, developed by John Biggs and Kevin Collis in 1982. As with the other two frameworks, SOLO focuses on the increasing complexity of what students can do with the things they know. SOLO has five levels: Pre-structural, in which students have a lack of understanding; Uni-structural, in which students can identify single, disconnected facts; Multi-structural, in which students gather multiple pieces of information within a Big Idea or schema, but without causal connections; Relational, in which students build the connective tissue among facts and start to see cause and effect relationships and systemic structures within bodies of knowledge; and Extended Abstract, in which students can use what they have learned to go beyond what they have been taught.

Here’s a clever little video showing how SOLO works, using the example of building things with LEGO:

I think it’s a useful framework to help teachers quickly identify the level at which they are asking students to work. And it highlights, perhaps better than any other framework, where most of our teaching and learning lives. In too many classes, students are working at the Multi-structural level, being given a long list of things to learn and things to do, with the requirement to remember and regurgitate those things on command, but no real understanding of why they matter or what to do with them in life.

If they’re lucky, students get up to the Relational level, where they are given a cognitive map of some kind—that LEGO instruction manual. They can put the pieces together in ways that have been pre-ordained, but they may not know why any of them matter outside of the context in which they’ve been presented.

Our goal should be that final level—the ability to take all the things you’ve been given and make your own, wild and wonderful and weird creations—the ability to carry your learning into life and use it in ways that no one had planned and that no one could have been able to predict, to enrich your life and empower your ambitions.

It’s something we all hope for. Could we do a better job of designing instruction to make sure it happens?

March 2, 2024

Filling in the Gaps

When I was in 6th grade, we engaged in a big archeology project with another classroom. Each room’s job was to invent an ancient culture in detail and then create a variety of artifacts to pack up and send across the hallway, for the other room to “dig up” and interpret. My class decided that our ancient culture would be all about cheese. I have no idea why we were all about cheese, but we were committed. We even visited a local cheese shop to learn obscure and interesting cheese names and facts. As a class, we sketched out all the ways our society worked, and then we broke up into table groups to take on roles within that society and start creating half-broken artifacts representing the lives we had lived—to both inform and confuse our junior archeologists across the hall.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I don’t remember what the result of the project was—what the other classroom made of what we created, or what they sent over to us to interpret. But the fact of the project has stayed with me forever, along with the lesson we learned, that our understanding of the past is built of bits and pieces—T.S. Eliot’s “heap of broken images.”

We have 14 plays from ancient Greece, along with teasing references in other literary works to a few other plays and playwrights. But there were hundreds of plays, and most of them are lost. Do we really think that our 14 paint an accurate and complete picture of what “theater” was, in that place and time? Do we assume that whatever was lost was lose-able, because it was less worthy, or even less representative? The 14 plays survived because they were popular and had many copies made of them—but they also survived out of sheer chance and luck.

When Hilary Mantel wrote her wonderful Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII, it outraged a lot of people who had grown up seeing Cromwell as the bad guy and Thomas More as the saint and martyr. Count me among them—I grew up watching A Man for All Seasons, and Paul Scofield was definitely my dude—not Leo McKern. But in Mantel’s novel, Cromwell was the proto-modern man—capable, rational, far-sighted, personally ambitious, unafraid to question the past, suspicious of superstition. More, in her telling, was a cold, bloodthirsty, religious zealot—and kind of a prig. He was the past; Cromwell was the future. In her telling, Cromwell’s mind is the mind that created the world we live in.

So, who’s right? Historians complained that the record proved Mantel hysterically wrong. But what is the record? Surviving letters, speeches, and proclamations written by those who survived Cromwell and defeated him: history as written by the winners. We know what he did (some of what he did), but do we know why he did what he did? Do we have it in his words? Do we know his mind? Do we know it all?

I think back to our archeology project in sixth grade. We created an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, and we asked the other classroom to use the pieces we gave them to help them fill in the gaps. History is like that—and sometimes, we have very few pieces to work with. How do we know—how do we know—that the pieces we create to fill in the gaps accurately represent the material that once used to be there? It makes me think of the frog DNA that the scientists in Jurassic Park use to fill in the gaps for the dinosaurs they’re trying to recreate. Those pieces do the trick—they create a living creature that’s a lot like a dinosaur—but they don’t recreate what actually roamed the earth; they make something slightly different.

Something similar happens in the here and now, in our every waking moment. As Daniel Kahneman writes in his amazing book, Thinking Fast and Slow, our eyes take in more visual data from our immediate environment than our brains are capable of processing in real time. We think we’re walking around inside a complete and accurate visual representation of the world, but…we don’t know that for a fact. The capacity of our brain to process information, and our working memory’s limited capacity to hold information, all put constraints on how much raw, visual data actually gets consciously perceived, processed, and acted on. We construct a simplified model of reality based on selective sampling of visual details. Then we fill in the gaps. When reality seems to fit, and for as long as it seems to fit, we don’t challenge or change the model we’ve built. When reality conflicts, we make adjustments. This has been tested and confirmed, over and over again—sometimes in amusing ways (like quickly swapping one blond woman for another to see if the man she’s been speaking with realizes there’s a new person in front of him) (TLDR: he doesn’t).

When we test our perception against facts, we have a chance to readjust the model of the world that we’ve constructed. We get to blink and realize that the woman in front of us is not the woman we thought she was. But if we filter and limit the information that comes in, all we do is reinforce the model we have. If we only read and hear things that reinforce our pre-existing ideas, we have no chance to find out if our ideas are still true. We all know about that; it’s called confirmation bias. But this kind of bias leads to something called the ladder of inference, in which we become trapped in an ever-tightening noose that hardens our perceptions and pushes us to more extreme positions. We live our lives in a constant state of “it is,” instead of entertaining an occasional “what if?” that might force us to think differently.

I think it’s important to realize that this doesn’t apply only to some of us but not to the rest of us. This isn’t about Right vs. Left, or urban vs. rural, or college-educated vs. GED. This affects all of us. It’s simply how our brains work. The world we live in is not exactly, not precisely, not completely, the world we perceive in our individual minds, the world we tell ourselves stories about. There are gaps. And even when we work to close the gaps, the world is constantly changing, leaving our models behind.

It’s a little terrifying—a little science-fiction-y, maybe, but there it is. Our bodies exist together in the same world, but our minds do not—not unless we take action to learn more about the world and challenge what we think it is; not unless we talk to each other about how we perceive the world and listen to our neighbors about how they perceive it.

As it turns out, this is the essence of democracy and self-rule. This is what is required to make democracy work. Long before we had a revolution and a Constitution, we had town meetings. We came together in small groups and said, “this is what I see; what do you see?” Dictatorship does not need such things—it radically does not want them. Dictatorship says, “I am in charge, and the way I see the world is what the world will be.”

The Thomas More of A Man for All Seasons is still a hero to me, because he says to his king: you have the right to rule the nation, but you cannot rule my mind or my soul. I do not know how accurate this depiction is to the real man who died in 1535, but he is real to me. And when I see Alexei Navalny returning to Russia and saying essentially the same thing to his king, I know that there is truth there.

I don’t know how we can claim to be free men and women if we don’t do the work of dispelling ourselves of superstition, illusion, and bias—to see the world around us as it actually is, as clearly as we possibly can. So many bad people benefit from our unwillingness to do this hard work. And it is hard work—hard, constant work.

As George Orwell said: “To see what is in front of one's nose needs a constant struggle.” But, as our modern man for all seasons, Alexei Navalny, said, shortly before his death: "You're not allowed to give up."

February 25, 2024

The Bun Dance

My mornings start with Wordle, Connections, and the Spelling Bee on the New York Times puzzle app—sometimes ridiculously early. My goal with Spelling Bee is to get to “Genius” level if I can. Later in the day, I might try for “Queen Bee’ if I’m feeling ambitious. And if the hints actually help me.

The other day, I hit '“Genius” without finding the pangram, the word made up of all seven letters in the puzzle—which I find particularly annoying. I went back to the puzzle several times during the day, to see if looking with fresh eyes might reveal something. Eventually, it did, and I found the word “abundance.”

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The funny thing was that, earlier in the day, while messing around with letters to see if I could unlock an idea, I had typed in “bun dance,” and had not seen the real word just sitting there, waiting for me to add the letter “a.”

Sometimes, we see things without actually seeing them.

I thought back to this silliness a few days ago, while running a product workshop with our sales team and talking about aspects of the Science of Reading. A lot of attention has been paid to the need for explicit and systematic instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics in the early grades. This was the focus of Emily Hanford’s excellent podcast series, Sold a Story, which is compelling and disturbing even if you’re not in the ed biz or putting children through school right now. But there are some folks in school districts and state departments of education who seem to be missing the fact that the Science of Reading is not a single thing or a single approach, and that what it requires changes as children get older.

Once students have successfully learned how to read independently, they do not need endless lessons in reading comprehension skills—explicit and systematic instruction, in grade after grade, on things like finding the main idea, identifying supporting details, and using context clues to understand new vocabulary. And yet, that’s what many RFPs and adoption rubrics seem to be demanding—understandably for academic intervention programs, but also, sometimes, for core and supplemental programs. It’s beyond overkill; it’s actually counterproductive.

As Natalie Wexler lays out in her book, The Knowledge Gap, once students know how to read, their reading improves by building knowledge, not abstract, disconnected “skills.” And yet, throughout the country in our elementary schools, ever since the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, we’ve been pushing science and social studies to the side to make room for generic skills-work within the reading block. Students are reading nonsense—passages that exist only to emphasize a particular skill but not to build any useful knowledge. And they are expected to be able to transfer these free-floating skills to their textbooks and novels, later on. Or perhaps just to their state standardized tests, which is the only kind of reading activity in life that resembles these skills lessons.

The problem is that skills don’t exist in a vacuum; they are context-dependent. If you don’t have a basic grasp of a historical period, you’re going to have trouble applying generic reading skills to historical reading. If you don’t really understand how vaccines work, you’re going to have a lot of trouble, even as an adult, engaging in a debate over the efficacy of a new vaccine during a pandemic—as we all saw, just a few years ago.

E.D. Hirsch pointed this out back in 2006 (earlier, really), by showing how a very simple-to-read sentence could be baffling to readers coming to it without context. Most Americans will have no trouble with a sentence like, “Jones sacrificed and knocked in a run.” But if you know nothing about baseball, you will read the individual words but fail to put them together into an idea. And no worksheets on reading skills can cure that problem. Only access to and experience in the world can.

Even when our curriculum does present students with useful information in the subject areas, it runs the risk of drowning young brains in disconnected facts. Remember, it’s not the facts that matter; it’s the context, or what scientists call the schema, the way we organize discrete information around big ideas. Grant Wiggins used to call it, “contextual Velcro;” the facts you learn are discrete, little balls, but they need a sticky target to hold onto.

This was the whole idea of H. Lynn Erickson’s approach to “concept-based instruction and curriculum.” The facts of a historical period are not important (or memorable) in themselves; they are important to the extent they help us understand something about that period—and, hopefully—our own world. So: if you’re learning about the westward expansion in our country simply because it’s in Chapter 5 and you already finished Chapter 4, that’s not super-compelling (or memorable). But if the information is presented within the context of an engaging question, like, “why do migrants risk everything to move to a new place?” you give students a reason to care about the content. And you can tie that historical period to many others, going all the way back to the story of Abraham in the Bible, and coming all the way up to current debates about immigration reform. This is learning, not only to know and remember, but also to recognize and empathize. This is learning that enmeshes you in a world, rather than leaving you free-floating and confused.

The world is rich and varied and wondrous and strange. Our job as educators is to make sure our students see it in all of its abundance…and not get stymied by a meaningless “bun dance,” that’s almost-but-not-quite what they need.

February 17, 2024

In Defense of Writing

I entered the education business in the year 2000, shortly before the passing of the No Child Left Behind Act, and from that moment to this one, the act and the art of writing have been cheapened, under-supported, under-appreciated, and dismissed in far too many states and schools. As a writer, I object. As a thinker and a citizen, I’m concerned.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It’s often said that if you want something emphasized in school, you test it—and that if you don’t test it, it will end up being de-emphasized whether you want it to be or not. Standardized tests in social studies and science were not included in NCLB, which led many states and schools to narrow the curriculum and pay less attention to those subjects, purely out of a survival instinct and a fear of getting punished for poor reading and math scores. Writing suffered the same fate; where it wasn’t included in assessments, it wasn’t taught or demanded as comprehensively as it should have been. And where it was taught, it was approached too often as a “teach to the test” task: however writing was tested, that’s exactly how—and how much—it was taught.

And how was it tested? As a timed task, always. As a response to comprehension of text, sometimes. As a way of making an argument about a hot topic, fairly often. It was scored according to a rubric, by people who did not know the student, and it yielded a number which told schools and teachers and students…very little. In all my days in the test-prep biz, I never heard of writing scores being determinative; they were part of the picture, but they were never important enough to make or break the overall score. And where the scoring rubrics were made public, writing became a very trainable task. It was not a thing that mattered; it was simply a thing that had to be done.

Why does writing matter? Because it forces us to visualize what we’re thinking. When we speak, the words drift out into the air and are gone. We can’t call them back. We can’t re-shape them. And it’s very difficult to build upon them in the moment, to create a structured argument or idea. Not impossible, obviously (our ancient ancestors managed it)—but difficult.

When the words are in front of us, on paper or on a screen, we can look at them and say, “That’s exactly what I meant,” or we can look at them and say, “That is not it at all.” Writing helps us think about what we’re thinking. Writing allows our words to be clay, and gives us time (if we are given time) to shape and re-shape that clay until the resulting object pleases us. This blog post may be good or it may be bad, but I can assure you, the published version will look nothing like the first draft. I’ve already written and cut whole paragraphs, and I haven’t even gotten through a draft yet.

Is that just because it’s difficult to find the right words to express our thoughts? Sure, partly, sometimes. But it’s also because it’s difficult to know just what our thoughts are when they’re swirling around our head, unformed and unexpressed. When you write the words down and say, “No,” it may not be because the words aren’t right; it may be because what you thought you were thinking wasn’t really what you were thinking, or what you wanted to say wasn’t quite this. It’s hard to know until you see it.

“What are you trying to say here?” requires a lot more focused coaching and regular feedback from a teacher than “what is a noun?” And it requires time—writing time and reading time. Unfortunately, in far too many places, teachers have less and less time to devote to writing, the older the students get. As writing becomes longer and more complex, the time it takes to read it thoughtfully and give useful feedback can become overwhelming, and the expertise required to give meaningful feedback increases. If the real value in writing is formative (I’m working my way towards what I’m thinking), rather than summative (here—it’s done—what did I get?), students should have someone sitting with them from the initial outline through all of their drafts, guiding and helping them. And yet, I’ve known too many students who get no feedback at all, just a letter or a number grade, or who get some desultory red marks on their paper at the end of the term, when there’s no time to do anything about it. And I’ve known too many teachers who become overwhelmed by the task of responding to student writing in any way that’s helpful. Good teachers—trained and experienced teachers who might actually have something useful to say about a student’s writing—the kind of teachers we seem to be losing from the workforce every month.

I think this is where the brave, new world of generative AI could be helpful, as I wrote last year. If what students need is a personal writing coach, a little Jiminy Cricket perched on their shoulders whenever they’re working, guiding and advising them, then this new technology may be the best way to give them the support they need, at scale.

What we do not need is a faster way to render a rubric score—which is what we’ve had from technology so far. We’ve had auto-grading software, though most of it required a pretty heavy hand of human training at the individual question level before it could be used. Now, though, with tools like ChatGPT, we have the ability to engage students in actual discourse around their writing—to give them immediate feedback on whatever they are writing, focused not only on grammar and structure, or even on whether a response is factually correct or not, but also on matters of craft and voice.

Does this remove the teacher from the equation? No! Or, at least, I hope not. But it can provide a kind of electronic teaching assistant to extend a teacher’s reach, doing the slow and patient work of helping hundreds of students simultaneously: asking questions; providing feedback; pushing students to try again, to rephrase, to refine and iterate. It can help change the conversation from writing-as-compliance-task to writing-as-learning-and-reflection.

But does this really matter? Reflecting on what we’re thinking, and how and why we’re thinking it—being extra careful about the words and arguments we use to communicate our thoughts—isn’t that a bit of an elitist luxury? What difference does it really make?

I think it makes all the difference in the world. I think we are rushed and sloppy with our thinking and our sharing. We tweet, we text, we post…we blurt out our thoughts as fast as we can type them, and we create confusion and misunderstanding as we go—and sometimes real damage. This is an increasingly complex world, and we are fed more and more information about more and more corners of it, faster and faster every year. We are reactive, not reflective, and it shows in our public discourse and in our politics. On our best days, we are emotional more than we are rational, and these have not been our best days.

But the world belongs to us. We could take a moment. We should take a moment. We should take all the time we need to think about the world, and to think about how we’re thinking about it, and where our ideas come from, and whether those ideas are good and helpful. We should take the time we need to write, and erase, and rewrite…and then walk away to get some fresh air and listen to, I don’t know, a bird or two…and then come back and look at what we’ve written. To look at what we think.

We matter. What we think about the world matters. What we think about the world affects what we do in the world, and to the world. It’s the only world we’ve got. And our life in it is the only life we’ve got. Don’t you think it’s worth more than a first draft?

January 28, 2024

The Right to a Wrong Idea

In my last post, I said something about how teaching comes in two flavors or styles: the sharing of gifts and the asking of questions. All well and good. But is the student always required to accept the teacher’s gift? Is the student required to give the answer the teacher wants?

If I teach that 2 + 2 = 4, is it okay if a student says, “No, it isn’t?” Maybe you think that’s an easy question. How about this one: if I teach that the states of the southern confederacy seceded in order to protect their right to keep slaves, is it okay if a student says, “No, they didn’t?”

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The easy response in both cases would be to say that it’s the teacher’s job to correct the student, period. Identifying and correcting misconceptions is a critical part of teaching. It’s why we don’t simply say a bunch of things and then move on to the next bunch of things. We assess—informally and formally—all the time—to make sure students understand and can apply what we have taught. We hold ourselves responsible for them knowing the truth. When we catch a mistake or a misconception, we’re supposed to correct it. Otherwise, what’s the point of all the blather? We might as well just talk to ourselves.

The older-fashioned way of doing this is to say, “WRONG” and provide the correct answer—or to move to another student to see if they know what they’re talking about. But this can be an unpleasant and humiliating experience for the student, and it doesn’t encourage them to raise their hand next time. It’s also not a particularly useful encounter for the teacher. All you’ve learned is that they don’t know X. Why they don’t know it, you have no insight into. And neither do they.

This is why, in classroom discourse, it can be more useful to ask students to explain their answers, even if it takes more time than simply correcting them. You can learn how a student thinks—and that is much more valuable than knowing they selected C instead of B.

Sometimes it’s important to dig into the correct answers, too, just to make sure students know what they’re talking about. There’s a great story that John Bransford relates, about a third grader who is asked about the shape of the earth. She says it is round, and the answer is accepted. It is only several years later that the student discovers, upon being embarrassed in front of her class, that when she had said “round,” she had been thinking in two dimensions, not three. The third-grade teacher hadn’t taken a second to ask, “round like what?” to find out if she would say, “round like a ball,” or “round like a plate.” Taking that extra minute to ask, “what do you mean by that?” can save everyone a world of trouble later on.

“What do you mean by that?” is a powerful assessment tool. It digs under the surface to reveal what’s underneath. “How do you know?” or “can you show me how you got that?” are also good options. It’s possible that a student heard her neighbor whisper the correct answer a minute ago. It’s possible that she memorized the correct answer but has no real understanding of why it’s correct. One probing question can reveal a lot.

It’s also a more respectful way of engaging with a learner. It’s not adversarial; it doesn’t flaunt the teacher’s authority. It communicates genuine curiosity. It opens things up rather than shutting things down. It tells students that a mistake is the beginning of learning, not a dead-end of embarrassing failure. From personal experience, I can tell you that my lifelong feelings about math would have been very different if anyone had ever helped me think about why I was wrong, instead of simply telling me, over and over, that I was wrong.

This approach becomes even critical as the student gets older and the issues under discussion become more complex and, potentially, controversial. So, let’s get into that. What happens if a student isn’t making a straightforward procedural error, but is stating a belief based on a religious or political background that put them at odds with your curriculum or with you?

The easy answer is to say, again, that it’s the teacher’s job to correct the student, period. But these days, depending on the state and the district, a teacher can be accused of “indoctrination,” simply by teaching a fact (or, worse, an interpretation) that is at odds with the community’s way of thinking—or even one parent’s. So what’s the right thing to do?

My feeling is that even when things are controversial, asking probing questions is the right way to proceed. If the student insists that slavery had nothing to do with the Civil War, ask them why they think that, and where they got their information, rather than shutting them down and saying, “no.” There is a difference between fact and opinion, between reality and belief, and part of our job is to help students build the intellectual toolkit they need to tell the difference. If we do all the thinking for them, we’re keeping all those tools for ourselves.

Dialogue, as we said, is more than respectful and curious; it also opens the door to change. Socrates changed people’s minds without stating a position of his own; he just asked annoying questions that forced his victims to think their way to a different position. Socratic teaching takes a lot longer than simply lecturing. A lot longer. But students come out of the encounter owning the resulting ideas as their own (whether they have changed their minds or held firm on their previous beliefs). We can engage them in the dialogue, but they have to own their minds.

Are we okay with the holding firm, though? Do we think a student has the right to hold a position or belief we think is flat-out incorrect—or abhorrent? What is a liberal teacher supposed to do with an alt-right reactionary in her classroom? What is a religiously conservative teacher supposed to do with an outspokenly progressive student staring her down?

Let’s agree that respect is the non-negotiable floor to all of this. Everyone must be treated with dignity and respect in the classroom. Every child needs to feel safe and welcomed. Every teacher needs to feel safe and respected. If a child’s beliefs make it impossible for them to be a respectful member of that classroom community, they need to learn elsewhere. If a teacher’s beliefs make it impossible for them to be a respectful member of that classroom community, they need to teach elsewhere.

Once we’ve established that, is it allowable for a teacher to express a political opinion in the classroom and to argue against a student whose beliefs they disagree with? Plenty of people these days say No. It’s indoctrination, and is wildly inappropriate—it should be, in fact, a firing offense. Other people say Yes—the world is inherently political, and it’s impossible to talk about the world in any serious way without having a perspective on it. Young people cannot learn about the world if they, and we, are not allowed to speak openly and honestly about it.

I don’t know that there’s a perfect answer—or a universal answer that applies everywhere and makes everybody happy. But I think the key is examining and understanding one’s own beliefs and biases and seeing them clearly—knowing where and when they affect the way material is presented in the classroom, and then clearly distinguishing “I think” from “it is so.” Here is what we know and what we do not know; here is what I think it all means; here is why I think that. When we express an opinion in front of students, we should hold ourselves accountable to opening our mind to them in this way. When they express an opinion, they should learn to do the same. It may not be a perfect inoculation against charges of indoctrination, but it gives teachers a firmer bit of ground to stand on.

Sometimes, the progression of evidence is air-tight and a position is either clearly right or clearly wrong. If a student cannot defend their position, it should be challenged. If they believe that 5 x 3 = 72, well, they’re wrong. They will not be able to prove or support that position. So…give them the chance and let them learn.

What about the student who denies that slavery caused the Civil War? Well, the behavior of humans is messier than the behavior of integers, so it’s not as cut and dried as 5 x 3. It takes longer to understand why that position is incorrect. Understanding history involves more than reciting events in a narrative as though an author wrote a novel; it requires questioning the fragmentary and contradictory evidence that history has left behind—what the evidence is, and where it came from, and what agendas drove the creation of it, and how it has been used in the years since the event. It requires asking what we think we know, and why we think we know it. That is the essence of historical literacy. To avoid engaging with that way of thinking because it might offend someone is malpractice.

The idea that teachers should confine themselves to “reading, writing, and arithmetic,” the vaunted “basics,” and keep away from anything controversial or political, is hopeless. The world is not simple, and we will not help the world by pumping simple-minded adults out into it at every high school graduation. The idea that there should be an iron-clad separation between what young people learn at home and what they learn at school, and that the one must never affect or influence the other, is absurd. Our upbringing does affect and influence how we think about the things we learn in school. And the things we learn in school do affect and influence the beliefs we were raised with. It has always been this way; it will always be this way. The only question is whether young people emerge from their schooling trusting their elders as honest guides and coaches, or whether they enter adulthood despising their elders as liars.

No social movement or legislation to infantilize education will win, in the end. The world makes itself known. It’s up to us to decide what role we want to play in its revelation.

January 23, 2024

The Importance of Shutting Up

Teachers like to talk. I was a teacher, and while I think of myself as an introvert at heart, I have to admit that in the right circumstances, man do I like to talk. My parents were teachers. My wife was a teacher. Talkers, all.

This shouldn’t be surprising. We know a lot of stuff. We’re passionate about the things we know. We like to share. We love to share. My wife and I drive friends crazy with constant book recommendations because OH MY GOD YOU HAVEN’T READ THIS YET? YOU HAVE TO READ THIS! In fact, my wife went through such painful book-talk withdrawal when she stopped teaching that she started a podcast, 17 years ago, to talk about—actually, to teach—her favorite classic novels.

And me…well, here I am.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

When we truly love the things we teach, there is something beautiful and meaningful in the act of sharing. A treasure is more valuable when it is shared and appreciated. I had a philosophy professor back in college who told a story about being a resident advisor, earlier in his career, and having two kids run over to his room to tell him about a sunset that was happening on the other side of the building and that he simply had to see. He walked over with them to witness the sunset, then returned to the dark side (where, he liked to joke, philosophers belong) to think about the event. Why had the kids felt the need to share the beauty? Because you appreciate the wonder of wonderful things more when you share them with somebody else. If that’s not a philosophy of teaching, I don’t know what is.

There is another aspect of teaching, though, beyond the sharing of gifts. It’s the asking of questions—the prodding of students to think for themselves. Here, the teacher doesn’t just lecture; she pokes and prods and questions and re-questions, to challenge every assumption and make the student think their way past biases, misconceptions, and errors, to find the truth.

Both aspects are important and real; both aspects are things we’re taught to value. But the first one takes our attention so much of the time that we often forget to value the second one. When we do value it, we give scant time for it, surfing over students’ heads in search of a response to a question that has one, definitive, correct answer—an answer that the teacher already knows, and from which the teacher can derive no profound data, aside from confirmation that a student got it.

If we believe that learning involves more than simply hearing things and repeating them back—that it requires some thinking, some processing, and some synthesis of ideas—then we need to provide time and space for that to happen. We need to reduce our own noise and allow enough quiet space for students to think and speak. Robert Marzano taught us about wait time years ago—the idea of allowing more time and space for a student to speak up and provide an answer before we move on to another victim. But do we leave enough time and space for the answer itself? Do we even ask questions that require time to think through?

If we believe that students are not empty vessels waiting to be filled—that they bring rich lives and interesting brains to school—then we have to make sure we leave space for students to talk to each other, and to themselves, and to us. We need to give them time to unspool a thought and develop it—not just respond off the top of their head. I was taught in grad school that when interviewing, it’s best to reduce the number of questions you ask and allow a lot of time for a response, because the really good stuff, the stuff you want, will not come out first; it will only come out as the respondent has to sit in silence after that initial response, and reflect on what they really think.

If we believe that teachers should be learners, too, and that learners can be teachers, then we need to rein ourselves in from time to time and do more listening than talking. It’s a scary thing, sometimes—that silence can be a very vulnerable space. But it matters.

If we believe that genuinely formative assessment requires us to get inside students’ brains and see not only what they’re thinking, but how they’re thinking (and why they’re thinking that thing, that way), then we need to let them do more than answer a question. We need to let them think, and talk, and talk some more—to explain their approaches and justify their solutions. We need to ask the kinds of questions whose answers might surprise us…and teach us something.

A great athletic coach knows when to demonstrate, when to watch performance, and when to step in with feedback or a minor adjustment. They spend a lot more time watching than talking, because they know that their performance isn’t what matters; it’s the players who have to play the game.

Too many of our students think that they come to be school to be spectators. We need to let them know that their job is to play.

January 13, 2024

Prioritizing the "Aha!" Moment

If I’m talking with teachers about something like getting math students engaged in problem-solving discourse, somebody will always say, “But what about time on task?” If I’m writing something about argumentation using textual evidence, somebody will always want to comment about time-on-task. You can invent this new strategy or that new reform, but in the end, if students would simply spend more time engaged in their work, they would learn more. Is that not so?

Well…it is and it isn’t. As David Berliner says, “What is wanted is a measure of time-on-the-right-tasks” (The Nature of Time in Schools, 1990, p. 18). All instructional time is not created equal, and, as it turns out, all “engaged” time may not be the same, either.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In a chapter from Perspectives on Instructional Time (Fisher and Berliner, eds., 1985), Linda Anderson describes a team observing eight different 1st-grade classrooms. The students appear to be extremely diligent and well-behaved, doing exercises in their math and reading workbooks, completing their work in the allotted time, and being kind and polite to each other and to the teacher. These should be dream classrooms for teachers. However, when asked questions about the work they’ve just done, a large number of the students don’t have a clue what any of it means. “I didn’t understand that, but I got it finished,” one boy says (p. 195).

His response may be more typical than we’d like to admit. In the same chapter, the researchers observe a very happy set of students completing a fill-in-the-blank vocabulary activity, in which every blank is exactly the length of the word needed to fill it. The students are happy because they have figured out how to complete the activity without having to learn most of the words. It’s just a matter of making things fit. The procedure has become the content. Completing the worksheet is the actual learning objective, regardless of what the teacher may think is going on. Time-on-task? Absolutely. Time-spent-learning? Not so much.

One definition of student engagement, drawn from six years of classroom observation as part of the Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study (BTES), is known as “Academic Learning Time,” or ALT (Fisher, et al., 1978). ALT is the amount of time during which students are actively and productively engaged in real learning. As Berliner (1990) defines it, ALT is “that part of allocated time [the time set aside for instruction]…in which a student is engaged successfully in the activities or with the materials to which he or she is exposed, an in which those activities and materials are related to educational outcomes that are valued” (p.5).

Let’s slow that down and look at some of the key words in his definition.

Engaged: The researchers in the BTES study found that teachers who were more interactive in their teaching styles, who engaged students in academic discourse throughout instruction and practice, helped students perform at higher levels in both math and reading. Students whose skill practice was silent, isolated, and tied to a workbook showed slower progress and slighter academic gains. Berliner talks about the value of pacing a lesson briskly, to keep the discourse lively and the instructional movement exciting. It’s interesting how many teachers take the opposite approach, slowing things down to make sure everyone understands every word (like I’m doing here? Oops).

Successfully: Berliner and others who write about ALT stress that individual student success with the work must be a part of the equation—and they insist on very high rates of success; 70% or even 80% at a minimum. To them, this is a crucial difference between being merely on-task and being engaged in learning. After all, if students can’t demonstrate their learning, can we really say their time-on-task led to learning?

Related to Educational Outcomes: This touches back to our anecdote about the vocabulary worksheet. “Time-on-the-right-task” requires that student work be aligned with the topics and the rigor-level indicated in the teacher’s learning objectives and the related state standards. This might seem like a no-brainer, but there’s a difference between being aligned to a general topic on a pacing plan, and being aligned to a specific learning objective that is pitched at the appropriate level of difficulty.

That Are Valued: And, as the final cherry on top of the ALT sundae, we need to make sure that objectives set by the teacher and the work being asked of students are valuable, meaningful, and relevant to both the school and the student. Worksheets and practice sets might be valuable and meaningful tasks for students…or they might not be. If it’s just busy-work, we may get compliant and well-behaved students, but we likely won’t get genuinely engaged learning, and, as we saw above, we may not get any learning at all.

Clearly, the more of our instructional time that students spend in ALT, the more they will learn. But how much of our class time do students actually spend in ALT? Nationwide, the answer has been pretty grim. Researchers have found that some schools dedicate as little as 50% of their allocated time to instruction at all (after accounting for administrative tasks and classroom management issues), and that real engagement rates within that instructional time can range from 50% to 90%, depending on the skills of the teacher (Hollowood, Salisbury, Rainforth & Palomboro, 1995). At the low end, with students spending half of their class time in any kind of instruction, and half of that time in any kind of meaningful work, this means there are students who are spending no more than 25% of their time actively learning. One wonders what percentage of that time is spent at high levels of success.

This is why the “Aha Moment” is so important. That moment of connection and realization is a great signal to us that a student isn’t just “doing it,” but is actually “getting it.” It’s a sign that something is actually changing inside the student—that a new idea is forming, or a change of perspective is happening. It’s a physical thing, and we’ve all felt it—we’ve all felt that moment where something just shifts and changes, and we suddenly see things differently. It’s thrilling. It’s addictive. And it leaves its mark.

Yes: to learn is to be changed. No one should walk out of a semester or year-long class exactly the same as when they walked in. What a waste of time! Maybe it’s your content knowledge or your ideas about the world that change. Maybe it’s a particular skill that you develop or improve. Whatever it is, a learning experience should be a workout; it should stretch the muscles and leave you stronger or more limber than you were before. And a learning process should be like a long-term exercise regimen; it should work upon you and leave its mark on you. Even if it’s just a new idea you never had before, once you have it, you can’t ever un-have it. That light bulb never gets turned off.

If we think about the moments where we saw a light bulb come on for a student, it’s pretty clear (at least in my experience) that those moments come in the midst of some kind of challenging, productive work the student is doing or discussion the student is having. Those moments don’t often come in the middle of a lecture, and they don’t often come at Question #11 in a practice set. They come when we’re pushing up against the outer edge of a student’s Zone of Proximal Development, challenging them to go deeper and further than they’ve gone before. They may come after several failed or botched attempts, when the pieces finally fall into place, and the details fit together to reveal the big picture and big idea that the student hadn’t seen before.

Those “Aha Moments” are why we’re all here. They are the brass ring. They’re what we ride the carousel for, year after year. They’re why our students are on the ride, too, even if they don’t realize it. They’ll never reach for that brass ring if they don’t know it exists. We have to give them the taste for it—the hunger for it. And they’ll never catch it if they don’t take the risk to stretch out their arms and reach—further than feels comfortable—further than they think they can go.

But once they’ve done it—once they learn what it feels like—there’s no stopping them.

January 6, 2024

School Culture and Our Ancient Brain

If you have only taught in one school (or if all you know are the schools you attended as a student), it’s easy to take your personal experience as the norm, and maybe even as the inevitable. But as with everything else in life, the more varied your experiences are, the more your easy generalities and stereotypes tend to collapse. There may be thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird, but there are thousands of ways of looking at a school. And this matters a lot when we think about our expectations of students.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I started realizing this early in my career, when I taught at the Ben Franklin Academy, in Atlanta, GA. This is a wonderfully innovative, alternative school for students who need a more personalized educational experience. When I taught there, in the earliest days of the school (when the building was much less grand than what you see on the website now), it was very much a place for kids who had not succeeded in other educational settings, many of whom had become a bit “school-phobic.” Because of this, the founder and headmaster, Wood Smethurst, designed every inch of the school to not broadcast it’s school-ness, from the layout to the furniture to the structure of the school session, which was entirely self-paced and student-driven, with 1:1 meetings with teachers as needed. Kids could get up and walk around as needed, and even go into the kitchen and fetch a snack whenever they wanted. There were also cats to play with.

We had a few real hard cases in the years I was there, and you might think kids like that would take a while to acclimate to this very different environment. They might start fights, skip school, vandalize the property—all the things they had done at their previous schools—at least for a little while, until they learned that this was a different sort of place. But it never happened—never once, in the years I taught there. Their behavior was different from the second they walked through the door.

Why? I wondered. Was it because something in their most primitive brain told them that the old behaviors, which were required for survival in the old environment, were simply no longer needed? Were we that good at sussing out our environment at an unconscious level and adapting ourselves to fit it successfully? Is that one of the reasons Homo Sapiens were able to leave Africa and find ways to live in every corner of the world? Was that our species’ real superpower? And, if so, would these same kids, if I returned them to their horrendous old schools, snap instantly back to the old behaviors that had served them well in the past (physically, if not academically)? I suspected so.

If this is true, even partially, it means that school culture matters very, very much, because it influences and affects the way students behave towards, and in, their school from the moment they set foot in the building, in ways they may not even be aware of. And, as I learned at Ben Franklin, everything contributes to that culture: the physical layout, the furniture, what’s on the walls, the places and ways in which kids interact with each other and with teachers—all of it.

I was doing a series of professional development workshops for two charter middle schools in the Midwest, a few years ago. The two buildings had been built at the same time and were of identical construction. But they were led by two very different principals, with two very different philosophies and approaches—which allowed me to see how the same building could be used in two dramatically different ways and feel entirely different from each other. One was brighter and more cheerful, with a variety of public places to gather and socialize and work. When I went to the workshop, the teachers were wearing funny sweatshirts and brought tons of snacks, and were…just happier. It was a building I wanted to be in. The other building was completely different, and it felt completely different. Colder, more formal, more industrial. And the people behaved in those ways as well.

Culture can be part of the hidden curriculum of a school—the things we teach children whether we consciously plan to or not. The hidden curriculum can teach bias and prejudice; it can teach fixed mindset; it can teach jingoism or political pessimism; it can do a lot that most of us would be shocked to realize.

One of the most common things a hidden curriculum can teach is compliance. Jonathan Kozol wrote blisteringly about this at the tail end of the Vietnam war, attacking public schools for teaching docile, servile conformity through the ways in which they educated, even while claiming to teach democratic individualism through their lessons.

In a compliance culture, “time on task” becomes more important than the task itself, and students quickly intuit that the most important things are working quietly, finishing the assignment, and getting a good grade at any cost. What kids have come to understand about the content is of secondary importance in this hidden curriculum, regardless of what the adults may claim to care about. What students think or feel about what they have learned may be even less critical.

If those are the most important things, students will focus relentlessly on them, and many will look for shortcuts and easy-ways-out to give the adults what they want as painlessly as possible. It is easy to be outwardly compliant while being inwardly resistant or, perhaps, just disinterested. This is how cheating and plagiarism happen. If a school culture, in both its visible and hidden forms (and the culture of the community of parents it serves) truly values, prioritizes, and rewards learning and understanding over mere compliance, cheating becomes counterproductive. Yes, yes, you did all the things—but what do you know?

If I’m right about our deepest-brain ability to change on a dime if old behaviors are no longer necessary or beneficial when the environment changes, then concerns about cheating and plagiarism, which are especially front-of-mind in this new, ChatGPT world, are not necessarily school-killers. We can address them and deal with them,. It just won’t be easy. Changing the culture of a school—changing the expectations and demands of a parent community—doesn’t come easily. We may need to do some hard thinking, and have some hard conversations, about what’s productive and important and necessary.

It’s not that “time on task” doesn’t matter anymore. Of course it does. But we need to start paying more attention to those tasks, and make sure they’re worthy of our students’ time.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers