Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 5

December 22, 2024

Lost in a Good Book

Family is converging, Smoking Bishop is on the stove, and I’m trying to recover from a head and chest cold that my wife graciously gave me as an early Christmas present. Since that down-time allowed me (finally) to finish a book that I’ve been slogging through for months, I thought I’d look back on my year in reading.

Non-FictionThe Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

A giant tome of a book with one of those grand-theory-of-everything approaches to our world. Graeber and Wengrow upside-down-ify our old assumptions about the inevitable progression of humankind from hunter-gatherer to farmer to serf to citizen. They show us recent findings in archeology, like Gobekli Tepe, that suggest some kind of city planning or formal group structure for people, thousands of years before we thought anything like that existed, and without any sign of a king or overlord ruling the place. They present evidence that, for a long time and in many places, we were happy to live as nomadic foragers during the warm months, but then came together in centralized living with something like a government for the colder parts of the year. And they suggest that the Spanish encounters and conversations with indigenous Americans, which were documented and published widely in Europe, inspired the political ideas of the Enlightenment.

A Brilliant Life, By Rachelle Unreich. Our fabulous friend, Rachelle, an Australian journalist, sat with her mother in the last years of her life, interviewing her about her experiences in World War II, her survival through the horrors of the Holocaust, and her amazing resilience and determination not to let those events define the rest of her life. Tough, at times, of course—but also inspiring and lovely.

Thinking in Bets, by Annie Duke.

Duke, a professional poker player and the founder of the Alliance for Decision Education, has written several books that apply her unique perspectives and skills to the world the rest of us live in. In this book, she talks about how to assess risk in everyday life.

The Righteous Mind, by Jonathan Haidt

Haidt’s most recent book, about smartphone addiction, has churned up a lot of controversy. I haven’t read that one, but I did read this, earlier book, which attempts to put definition and explanation around different worldviews and ways-of-being. He argues that more religious and conservative people work from the same, general set of morals and values as more secular and progressive people, but that they weight and prioritize those values very differently, creating an interesting Venn diagram that has some overlap, but also some start differences.

This is Not My Memoir, by Andre Gregory

This is Andre, of My Dinner with Andre, the theater director and sometime film actor, telling stories of his life—his larger-than-life parents, his refugee childhood, his adventures in theater, and all of the strange and interesting people he’s collected along the way.

Ghosted, by Nancy French

Many people know of David French, the New York Times opinion writer and Republican apostate who, though deeply conservative both religiously and socially, had to be banished from the tribe for speaking the truth about Donald Trump.

His wife, Nancy, went through a similar scourging. Once a sought-after ghost-writer for conservative public figures looking to write memoirs, she was driven out of polite society—partly because of her marriage to David, and partly because of her work as an investigative journalist, uncovering years of sexual abuse and coverup at an Evangelical Christian summer camp.

No longer wanted as a writer of other people’s memoirs, French decided to write one of her own, and it’s an amazing story of grit, resilience, faith, and love. It gave me a glimpse, not only inside one person’s unique life, but also into a world I have had very little access to or or knowledge of. And that’s always a good thing.

Oath and Honor, by Liz Cheney

I was no fan of the Cheney family during and after the Bush administrations. Many of us thought papa Dick Cheney was a war-monger and a war profiteer, and I haven’t changed my opinion of him much since then.

But. There’s no getting around the fact that father and daughter stood firm against Donald Trump when so many in the Republican party folded. And Liz has put her career and reputation on the line, again and again, to do the right thing. So, I thought it would be interesting to read her memoir of this period.

It’s thorough and damning, and it’s not afraid to name names as the story unfolds and Trump’s election denialism turns into something toxic. Mike Johnson, our current Speaker of the House, is all over the story. Those of us who didn’t know who he was until he emerged from the Kevin McCarthy wreckage: he was there, and he was making himself very useful.

Cheney is so plain-spoken and unadorned and…well…Wyoming…that that she can get away with scenes that many readers would howl at in cringy disbelief. As she gets ready to head back to Washington to chair the January 6 committee, her father walks her out to the car, then leans down into the driver’s side window, and says, “Protect the republic, daughter.” To which she answers, “I will, Dad.”

Somehow, I can actually believe them having that exchange, hokey and old-fashioned as it is. And, somehow, that feels like a good thing.

Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come, by Jessica Pan

I found Jess Pan on Substack, where she was writing a charming blog about living in Paris and working in a bookstore. That led me to her funny and touching book about the year she spent defiantly saying Yes to everything, to break her out of her introversion and the rut she felt she had been digging for herself.

That’s it for non-fiction. Not a single education or technology book in the batch. How did that happen?

FictionWhen I started putting this list together, I felt sad about how little fiction I had read this year. Only four books? Really? But then I realized that at least two of the four were 1,000+ page beasts, and I didn’t feel so bad.

Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver

The one actual, contemporary bestseller that I read this year. I thought it was fantastic—so much so that I decided to read David Copperfield (upon which it is based) immediately after, because I had never read it before. Kingsolver does an amazing job of getting inside the head, and capturing the voice, of a boy and young man raised in Appalachia and dealing with abuse and deprivation of all kinds. Is it bleak? Yeah, it’s a little bleak. Is it unremitting? Yeah, kind of. But the main character’s grit, and humor, and insistence on moving ever forward, hoping for a better life, makes the journey well worth taking.

David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens

As I said, I had never read this book before. So, reading it after Kingsolver’s modern adaptation obviously colored the experience for me. I saw all the connections, all the references, all the things Kingsolver used, or changed, or discarded entirely.

Even so, it was great to read the original. I really didn’t like or appreciate Dickens in high school, which is the only time I read him (or was forced to read him). But now…it’s a little different. Bleak House was a revelation. And this book, as grim and unremitting as it is, sometimes, is also a whole universe, with laughter and lightness and pretty much everything else life has to offer. As tough a time as young David has, being pushed and prodded from place to place, there are always a few wonderful and warm-hearted characters around, who keep showing up in his life and bringing a little light to things.

Children of Time, by Adrian Tchaikovsky

This was recommended to me by my Ed Reform and Ed Tech friend, Thomas Steele-Maley, as we were comparing notes on favorite science fiction novels. I recommended N.K. Jemisen’s “Broken Earth” trilogy to him, which I’m sure he still hasn’t read (what say you, Thomas?). I loved this first novel, but got bogged down in the second of the trilogy. My older son, who loves both science fiction and fantasy, tore through the trilogy and is deeply disappointed with me for abandoning it.

HOWEVER. This first novel is amazing, and I’m very glad I went into it knowing nothing about it. The book narratives enormous leaps through centuries like nothing I can think of, other than A Canticle for Liebowitz. And the author does a great job of capturing the way a sentient, non-human being, living in a body very different from ours, might understand the world and build a society and a technology.

The Way of Kings, by Brandon Sanderson

This one was recommended by my children. Well…that’s not entirely accurate. It was demanded of me by my children. They started the negotiation at, “you have to read everything Brandon Sanderson has written,” and then retrenched at, “you have to read The Stormlight Archive.” My final bargaining position was, “I’ll read the first book, but that’s it. I can’t spend the rest of my life reading this one guy.” Because…this guy churns out pages, let me tell you. My boys accepted that offer, suspecting that, once I finished, I’d want to keep going. They might not be wrong.

I had a lot of trouble getting hooked. The first few chapters each focus on a different character, and not all during the same time period. I felt bogged down by all the alien words for things and names of people (especially when names were “normal” but with extra letters for the sake of alienness, like, “Szeth”). But that comes with the territory, I know.

It took a long time (it felt like a VERY long time) for a story to start to come together in my mind, with some compelling forward motion. Once it did, it was smooth sailing and quick reading.

Sanderson’s world-building is insanely detailed—not only in the center of the story, but also in lands far distant and times far past. His dialogue is a little flowery and fraught for my tastes, but people who love the fantasy genre don’t seem to care much about that. And the themes of the story are absolutely grounded, and real, and important.

So…yeah…maybe I’ll read the second one. Just the second one, though. I swear. And not right away.

Because…

OngoingUlysses, by James Joyce

I read this in college, in a seminar led by Joyce’s most well-known biographer, Richard Ellmann. That was a great experience. But it was a long time ago. I always thought it might be nice to re-read the book as an adult, and try to just…enjoy it, without analyzing every word or referring to the secret codex to unlock meaning from every reference.

My wife bought me a beautiful, hardcover version in Ireland and hefted it all the way home for me. I’ve made some progress, but it’s the kind of thing I like dipping into for a little bit, now and then, rather than reading straight through. So…it’s going to take a while.

What I Didn’t Quite Get Around ToAnd here’s what’s been sitting on my Kindle, waiting for attention, while I’ve been trying to finish the Sanderson novel:

Polestan, by Neal Stephenson

The Grey Wolf, by Louise Penny

The War of Return, by Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf

Escape from Freedom, by Erich Fromm

Life in Code, by Ellen Ullman

How We Learn, Stanislaus Dehaene (aha! There’s the education book I was missing)

On to 2025!

December 13, 2024

Measure Once, Cut Twice...or Something

I wrote recently about the idea of accountability—why it matters and how we do it wrong, especially in education. In many school districts, the office in charge of testing is called “assessment and accountability,” though it’s never quite clear who is being held accountable, and to what.

One thing I’ve learned about testing is that the closer to instruction it is done, in both time and space, the more useful the information will be. A classroom quiz at the end of the week is more instructionally useful to teachers than a final exam, and a classroom final exam aligned to the teacher’s day-to-day curriculum says more about what students learned than a state-wide assessment on large and sometimes vague “standards.” But our recent history hasn’t shown a lot of trust in teachers to do their jobs behind closed doors.

Being FormativeA classroom quiz at the end of the week is more instructionally useful to teachers than a final exam. If you see bad results on a Friday, you can take action on Monday to remediate the problem…unless you’re tied to a pacing calendar that allows you no room to breathe or flexibility to change plans.

Those kinds of assessments are called “formative,” because their focus is meant to be on the formation of skills and knowledge. Formative assessments can be as formal as a written test or as informal as “raise your hand if you think the answer is five.” The key to any of these assessments, from quick check-ins to quarterly benchmark tests, is that teachers can take action in response to them, as W. James Popham lays out elegantly in his book, Transformative Assessment.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It’s not just that teachers should have time to take action; it’s also that they should have a plan to do so—a plan they’ve worked out ahead of time. I’m going to check for understanding at the end of class today, and here are three things I might do tomorrow, depending on what I find out. Or even: I’m going to pause here, mid-class, to make sure everyone gets what I’m saying, and I have a plan in mind for what I’m going to do immediately thereafter, depending on what I learn.

When I first read Popham’s book, I was embarrassed to admit that I had never really thought about the importance of that planned follow-up. The follow-up actually matters more than the question: after all, what’s the point in taking someone’s temperature if you’re not going to do anything when you find out your child has a fever?

Far too often, we ask these check-in questions and then plow ahead with the lesson as planned, regardless of what we learn. Oh, we might correct a mistake when we hear one, but we don’t (nearly often enough) change what we were going to do next because of that mistake.

StandardizationOne problem with formative assessment is that it often gets swallowed up in the accountability mania. It’s not enough for a teacher to assess her class, her way, on her content. She must use district-mandated tests based on a district-mandated curriculum, for review by district-level managers. Students must receive a grade. Everything formative becomes summative, with a focus on judgment and consequences, not learning.

I was involved in such a mandate when I worked for a company that was creating standardized curriculum and assessments for a large, urban school district in the early days of No Child Left Behind. There was a lot that was good about the project and a lot that was fraught and stupid, but one of the worst parts was designing the assessments, because the teachers pitched an absolute fit about being held accountable so visibly and transparently, at a district level, to teaching particular content. They understood that one purpose of those assessments was going to be to judge them, and they didn’t like it. So, they harassed district leadership until they got the superintendent to back down from his original idea. In the end, we were allowed to assess only the larger skills being taught, not any particular content in the curriculum. In Social Studies, for example, we could assess map-reading skills in general, but we couldn’t assess whether kids in American History classes knew the fifty states or how to find the Missouri River, both of which were part of the curriculum.

The further away from the classroom the testing is conceived, the more standardized it becomes, to make local variance less important and to generate comparative results across large populations. The more tests there are to score, the longer it takes to return results. No Child Left Behind gave us a ton of end-of-year state tests whose results didn’t show up until the following year, when they were useful to no one except bureaucrats who wanted to scold schools for underperformance.

Some states tried to do a good job with these tests and assess student learning as well as they could; some didn’t try very hard. I remember in the early days, when New Jersey published a sample high school exit exam in English. It had a lot of interesting components to it, including narrative writing based on a piece of visual art, and also some kind of timed live presentation. Not everything survived early review; a lot of the more interesting elements proved too subjective to score and took too long to review. Efficiency and cost-savings ended up being more important (which is why many states never even bothered trying anything except multiple-choice questions).

If you want valid and reliably standardized scoring, you need a standardized implementation across the entire population, and that can make it difficult to do things like, “gather resources and prepare a 15-minute presentation.” In New York, where the high school exit exam in English required a speech to be read aloud to students, one school was so worried about the variance in delivery across its faculty that it had the principal read the selection over the loudspeaker. If you’ve ever been in a big, old, school building, you know just how crappy the sound quality can be on those loudspeakers. But hey, at least it was equally crappy for everyone.

Because “education reform” is more often about pendulum swings than it is about forward motion, the era of high stakes exit exams may be coming to an end. Only six states still require them, and two of the more thoughtful and rigorous tests, in Massachusetts and New York, are being phased out, to be replaced by something theoretically more “authentic.”

“I wish them well,” as Princess Saralinda is doomed to say to every suitor who sets out on a dangerous quest to win her hand, in my favorite childhood book, The Thirteen Clocks.

What Might Better Look Like?When people talk about “authentic” assessment, they tend to mean that they’re looking for ways to assess student knowledge and skills in contexts that more closely resemble the way we adults use them in everyday life—moving away from these artificial things we call tests and moving toward some kind of real-world performance or demonstration.

Ted Sizer, who wrote the influential books Horace’s Compromise and Horace’s School, talked about finding ways to demonstrate mastery by what he called exhibition. As one of his colleagues wrote, in an edition of the newsletter Sizer’s Coalition of Essential Schools used to put out:

Ted Sizer reached all the way back to the eighteenth century in search of an assessment mechanism that might function in this way. He found at least the possibility of it in a ubiquitous feature of the early American academies and of the common schools that shared their era. The exhibition, as practiced then, was an occasion of public inspection when some substantial portion of a school’s constituency might show up to hear students recite, declaim, or otherwise perform. The constituency might thereby satisfy itself that the year’s public funds or tuitions had been well spent, and that some cohort of young scholars was now ready to move on or out.

Joe McDonald in Horace newsletter, Winter 2007, Vol. 23 No. 1

Sizer outlined a number of possible small-scale “exhibitions” throughout his two books—things like asking middle school students to prepare a tax return for a family of four as a math assessment. But when it came to more summative and comprehensive assessments, his coalition of schools developed something bigger.

The “Rite of Passage Experience," or ROPE program at Walden III, which has been in place for over a decade, is a fully developed model of how such a requirement can function. Born from the Australian "walkabout" tradition in which a youngster must meet certain challenges to attain adulthood, ROPE is expressly designed "to evaluate students' readiness for life beyond high school."

Horace newsletter, March 1990, Vol. 6, No. 3

In the same newsletter, researcher Grant Wiggins, who went on to create the Understanding by Design framework with Jay McTighe, laid out some criteria for these larger-scale exhibitions:

I’ve seen bits and pieces of this kind of assessment, but never all of the bullet points at once, in something systematic and comprehensive. Maybe you have.

When I was teaching in Atlanta, in a very alternative school, we tried an assessment like this at the end of a pilot of an interdisciplinary unit on the theme of “utopias.” Students had studied both the Peloponnesian War and the Cold War, had read sections of Plato’s Republic and 1984; and had read short stories, poems, and bits of philosophy. They had responded to each item through quizzes and essays and such, but we wanted to do some kind of final assessment. So, we threw it open to the students and asked them to represent their idea of “utopia” in any form they chose. It was very loose and disorganized; we didn’t even have a scoring rubric. But the results were fascinating. Each student had to present their project and explain why and how it represented their thinking. One student wrote a song; another created a sculpture; one just did a guided mediation for the class. It was an interesting experiment. Where the school took that work after I left, I don’t know.

This kind of project-based learning and assessment can be fun and informative and engaging for students. It can also be garbage. Crafting the right project and figuring out what criteria you’re going to use to evaluate it are both very tricky. In practice, I’ve seen teachers grading the quality of an art project rather than its demonstration of academic skills or content knowledge. “I really enjoyed the way you edited your video” is lovely feedback, but if the video is meant to replace, say, a history test, the feedback needs more academic teeth than that.

When I was teaching conversational English in the Republic of Slovakia, I saw another element of the exhibition idea—actually, something more in line with the idea quoted above: “The constituency might thereby satisfy itself that the year’s public funds or tuitions had been well spent, and that some cohort of young scholars was now ready to move on or out.” The high school students didn’t have any exit exams, but there was a formal assessment period at the end of the year, when classes were suspended and members of the community were invited to join school leaders to sit behind a table and observe as teachers posed questions or gave performance tasks to students, to see if they could talk the talk and walk the walk in public, as educated adults. It was a genuine rite of passage for young people in the community, and everyone took it seriously. Kids came to school formal attire; parents brought tons of food (and alcohol) to sustain the judges all day. It was both festive and serious, and it made it clear that school mattered. I’ve never seen anything else like it.

Can Authentic Also be Efficient?If schools have resisted large-scale, authentic assessment in the past because of the burden it places on teachers, computer technology has been advancing in ways that may help to ease that burden.

In the first and most obvious case, machine scoring can now handle a great deal more than old-fashioned multiple-choice questions. There is a wide range of what we call “technology-enhanced questions,” ranging from fill-in-the-blank questions, to drag-and-drop or matching tasks, to plotting lines on a graph or measuring angles, all of which can be scored instantly by the computer, and all of which is a bit more performance-oriented than traditional questions.

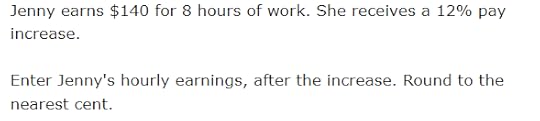

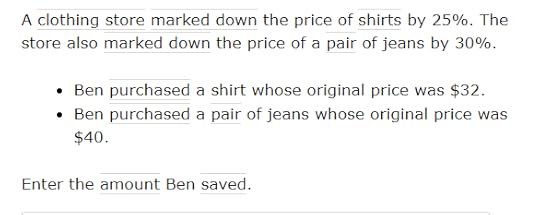

But most of these tasks are built with a single correct answer in mind, which keeps them from being truly real-world-like. When we have to use our math or language skills as adults, or call up our history and science knowledge, the problems are often ambiguous and unpredictable, and the solutions may vary, depending on how we approach them and what information or questions or assumptions we bring to them. There’s a big difference between a question like this:

And one like this:

What’s the challenge in asking a question like the second one? Every child will provide different information and will therefore have a different response. The teacher will not be able to grade the child’s performance unless she reviews the child’s thought process. It. Takes. Time.

Will generative AI be able to help? Maybe. Many companies are racing to provide schools and EdTech companies with tools that can analyze student writing (or speech) and provide clear, focused feedback—and even a rubric-based score. They’re a little hit-or-miss at the moment, given AI’s habit of…um…making stuff up (or “hallucinating”). But things are moving quickly in that world, and it will be interesting to see whether (or when) the tools will improve enough to be reliable without human input or interaction. Maybe the future won’t be completely hands-off for teachers, but will, instead, involve a partnership between AI and the teacher—not removing the burdens and challenges of authentic assessment entirely, but easing them and making them more manageable.

I would love to see more of what I saw in my small, Slovak town: a world in which the relationships between school and community, student and adult, are strong and clear and meaningful—where the whole town can feel like they have a stake in the skills and abilities of their young people, and can celebrate their entrance into adulthood and citizenship.

A guy can dream.

December 6, 2024

Be a Slider, not a Toggle

Whoever undertakes to set himself up as a judge of Truth and Knowledge is shipwrecked by the laughter of the gods.

Edmund Burke, Preface to Brissot's Address to His Constituents (1794)

Cosmic Scales vs. Cosmic WarsI don’t believe the stars affect your personality, but I’m about as Libra-y as anyone born in early October can be. I like balance; I like moderation. I like it so much that I try to moderate my moderation with occasional bouts of excess.

I like the middle-path. I like it when everyone is getting along. I’m politically liberal, but I believe the old adage about a bird with one wing only being able to fly in circles. I try to test my biases by reading ideas and opinions that I don’t share—from both political extremes. I’ve always felt it’s a basic civic duty of someone living in a democracy.

I know my bias towards balance colors the way I look at the world, and I know other people see things differently. Some people love a good fight. Some people love rooting for one team and despising the other team. Some people fight well and healthily. I don’t. I never learned that skill, so I just tend to…avoid fights if I can. I enjoy a good argument—about politics, art, ideas, etc. I’ll happily sit up all night at a bar or a coffee shop, debating and discoursing with friends about pretty much anything. But I get uncomfortable when it becomes angry and personal—when all the logical fallacies get pulled out and people start attacking each other instead of exploring ideas together. I don’t plunge happily into conflicts like that. I don’t plunge at all.

As you can imagine, I’m not loving our current political environment, where everyone is expected to wear a team jersey and adopt every position that comes with it—where everybody seems to believe that we’re engaged in a cosmic battle between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. Variety and complexity and ambiguity are out; having absolutist and extreme positions is in.

People with a fancy vocabulary might refer to this worldview as Manichaeism. The term comes from a cosmology with its roots in Mesopotamia (the prophet Mani was born into a Jewish Christian Gnostic family in what is now Iraq), centered around an eternal battle between good and evil, light and darkness. It thrived and even rivaled Christianity for popularity between the third and seventh centuries, CE, stretching from the Roman Empire all the way to China. The religion drew from many faiths and philosophies, including Zoroastrianism, which grew up in the same region about 400 years earlier, and which also featured a cosmic battle between good and evil, light and dark.

Those ancient worldviews definitely affected and informed our own, competing for attention, as they did, with early Christianity. That kind of dualism wasn’t really present in ancient Judaism. There was no concept of heaven or hell there, no cosmic battle for the souls of humankind. Later interpretations by both Jews and Christians layered some aspects of that dualism on top of the old texts.

The ancient Greeks, who influenced Roman religion before Christianity took hold, were more concerned with cosmic balance than with cosmic victory. They had a whole pantheon of gods representing a wide range of human emotions and attributes, each of which had to be honored and respected if one wanted to lead a good and happy life. Focusing on one and ignoring the others was often the cause of doom and downfall in their stories. Finding the middle way between extremes was seen as a virtue. As Aristotle said:

First of all then we have to observe, that moral qualities are so constituted as to be destroyed by excess and by deficiency—as we see is the case with bodily strength and health….Strength is destroyed both by excessive and by deficient exercises, and similarly health is destroyed both by too much and by too little food and drink; while they are produced, increased and preserved by suitable quantities. The same therefore is true of Temperance, Courage, and the other virtues. The man who runs away from everything in fear and never endures anything becomes a coward; the man who fears nothing whatsoever but encounters everything becomes rash.

Nichomachean Ethics, Book Two

Those ideas of balance and moderation and restraint influenced the Stoics, who influenced all kinds of folks throughout history, including our first few presidents (as I wrote about recently), as well as English conservatives like Edmund Burke, who said, “Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites.” (National Assembly, IV. 319)

But maybe that idea of balancing equal and opposing forces is too simplistic, too binary, too chained to Manichaean ways of thinking. Maybe the idea of a wider and more chaotic pantheon of cosmic forces is a healthier cosmology. It’s not a see-saw we’re trying to balance; it’s more like that old plate-spinning trick that used to be on early TV variety shows. After all, how much of our world is truly binary? How much falls neatly into black or white, good or evil, temperance or vice? Very little, it seems to me.

Banning the BinariesI’m starting to worry that we’re ruining ourselves by insisting that our most important issues are toggle switches instead of sliders.

You know the difference. A toggle switch has a limited number of settings, often just two. The lamp is either on or off; there’s no midpoint between the two settings. A slider, though, like a lamp’s dimmer switch, can glide along a span between extremes and can stop at many points along the way.

Toggle-thinking allows for only two states: A or B, black or white. Slider-thinking allows for a continuum of states: you can land anywhere from A all the way to Z. Black and white are in there, but so are many shades of grey—and the full spectrum of visible colors. Maybe it’s hard to see the reality of the rainbow if your only settings are black and white.

For any political or cultural issue, there are extreme positions and people who hold them. But there are millions of people who hold views between those extremes, and their voices are effectively shut out of the discourse, because winning an argument is more important than solving a problem, and maybe a strident “A” is a stronger argument than, “I don’t know, maybe it’s somewhere around Q.”

The problem with leaning towards A or Z extremes to win arguments is that most of us live somewhere in the in-between—and we land on different in-between positions depending on the topic or issue. Just as we’re not always standing at either A or Z, we’re not consistently at Q, either. I may be at Q on some questions, D on others, and maybe J somewhere else. We are jagged, not continuous, as Todd Rose makes clear in his book, The End of Average. Saying that the average weight of a population is, say, 250 pounds, doesn’t tell you anything about the varied individuals who make up that group. Individual qualities get lost to the average; individual perspectives get lost to the extremes.

We need to reclaim some jagged space for ourselves.

We have a young generation trying to reclaim that kind of space with their understanding of gender and sexuality, and God bless them for doing it. But they’re still locked into our old vocabulary. Saying you’re “non-binary” claims a new space, but only as a negation of the old spaces; it accepts the idea that the binary is the Thing, and you’re just against it. When it comes to gender expression and sexual attraction, do we really accept that it’s a world defined by twos, and anything that doesn’t fit the definition is either a lie or a weird outlier?

There are men who have what traditionally would be thought of as more feminine attributes and qualities. Some are attracted to women; some are attracted to men. There are men who present as more traditionally “macho.” Doesn’t tell you anything about who they’re attracted to or how they define themselves. We have no good classification language for any of this—for men, for women, for trans people. “Straight White Male” doesn’t come close to defining who someone is, and neither does LGBTQ, though we make a ton of assumptions based on labels like these.

I remember what I wrote about the duck-billed platypus, and how he was defined out of the biological classification scheme because he didn’t fit neatly into any of the man-made categories that scientists so confidently created. Maybe we need toss our old categories overboard and start over. Look at actual reality and make room for the variety that’s really there.

If we are slider switches, we consist of multiple sliders, and each of us has unique settings for each switch, like in a recording studio. On one attribute, I might be at setting 3; on another. I might be a 7. Who we really are, in our depth and complexity, looks much more like this image than a red flag or a blue flag can convey:

Let’s Talk

Let’s TalkHere’s one example of what I mean: Pro-Life and Pro-Choice are great team names but unhelpful ways of describing reality at an individual level. Most people in this country are pro-life to some extent, in some circumstances, and pro-choice to some extent, in some circumstances. “To some extent and in some circumstances” actually matters. Acknowledging that there are extenuating circumstances and mitigating details when these issues come up in real life—that’s the beginning of productive discourse. Exploring where we all set our slider-switches, and when, and why, is how we begin to craft compromise and, ultimately, policy…if that’s what we want (as opposed to endless warfare).

Some people do hold extreme and absolutist positions on all kinds of issues. Taxation, healthcare, gun rights, religious liberty. I get it. I find some of those people a little scary. Their worldviews admit only true believers and apostates, the forces of God and the legions of Satan. For them, the only resolution to the conflict they’ll accept is cultural—or actual—war, and the obliteration of the Enemy. Is that really where we want to live?

When we accept that there are many positions one can take between the extremes, and that most people live at different points along the continuums, there’s more opportunity for dialogue. When we accept that there are many ways to live between or outside of the binaries we’ve used to describe life—whether in politics, gender, sexual attraction, or anything else—life looks a lot more vibrant and interesting.

So, let’s talk. Let’s argue about where along the continuum we want to take a stand. Let’s accept and even revel in the grey areas, the ambiguities, the extenuating circumstances that make life complicated but also interesting. Let’s put it all on the table so that we can say, “Now, what are we going to do about it?”

I’m tired of us not being able to get to, “What are we going to do about it,” and I’m tired of pretending that this inability is accidental or fated. It’s neither. Our inability to talk to each other and solve problems is deliberate and planned. We are placed and kept at each other’s throats to build and maintain the power and wealth of those who represent the extreme positions—many of whom don’t even believe in those positions but have found it profitable and advantageous to hold them.

The continuum is messy and confusing. It requires respectful argument. It requires understanding and empathy. It requires shoving the slider a little more this way, a little more that way, till you get the setting just right for most people—or close enough to “just right” to live with. Choosing A or Z is easier, I know. Hating Z because you’re at A is also easier.

But none of this was meant to be easy.

December 1, 2024

[Re-post] It's All Our Fault

Because of the holiday this week, I’m reposting one more older piece, that didn’t get a lot of views back when I first uploaded it. New stuff next week, I promise.

We spend a lot of time fighting about what subjects should be taught in our schools and what facts should be included in those subjects, thinking that our tinkering and arguing is essential to the health of the republic—that, perhaps, if we just ban this book, or censor this topic, or include this under-represented perspective, we will fix the ____ that plagues us (which could be, depending on your political persuasion, ignorance, gullibility, and tribalism, or moral relativism, atheism, and multiculturalism, I guess).

In our endless cleverness—and bitterness—we find a way to fight about every subject at every grade level: from how we should teach our youngest students to read, to what we should allow our oldest students to read; from how we should teach our youngest students to develop math fluency, to what kinds of problems they should be allowed to apply their mathematical thinking to.

In all of these arguments, we make an assumption that whatever we teach, our students will learn, and that whatever we ask them to think about, they’ll think about in the same way, and from the same perspective, as their teachers. These are dubious propositions at best, especially once we start talking about high school students. It assumes a pedagogical power on the part of our public school teachers that feels superhuman to me and divorced from any reality I’ve ever experienced. Good luck getting kids to do their homework, much less adopt your worldview.

The thing we argue about far less—and which, it seems to me, has far more effect on the health of our country—is how we teach our children to understand and adopt the basic habits of mind necessary for participation in a republic. At most, we force students to take a civics class where they learn how a bill becomes a law. Is that all we think is required? Do we think that political self-rule is simply automatic? Instinctive? That, left to our own devices, we all understand how to engage with our neighbors in the kind of rational discussion and debate that allows a community—and then a state—and then a nation—to make rules for itself and then live by those rules? If we believe that…why do we believe it? Has anyone been to a school board meeting lately? What are we thinking?

For most of recorded history, the norm has not been community self-rule, but something like feudalism or monarchy (for a fascinating look at pre-recorded history, and the surprising variety of social/political forms and shapes in which we seem to have lived, check out The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber). And in our own time, we’ve seen two examples of so-called Western, allegedly civilized societies sliding from democracy into autocracy: once in the 1930s, and once right now. If democracy is so instinctive, why does it seem to be so hard to hold onto?

And if we believe that democracy is not only our birthright, but coded into our DNA, why are we so afraid that schoolchildren will mindlessly agree with and adopt the opinions of their teachers (and that, therefore, those adult opinions must be tightly monitored and controlled)? Is it just about children—that they have not yet been adequately taught to be critical, skeptical, and rational? If we believe that about seven year-olds, why do we still seem to be believe it about 17 year-olds? And do we still believe it about 27 year-olds?

I would argue that democracy requires habits of mind that are not instinctive and automatic, and that require education and training in order to adhere in adulthood and allow individuals to stand upright and make decisions for themselves and for their communities—decisions that do not simply hand power over to a charismatic charlatan or a bullying strongman. What is natural and instinctive—what appeals to our lazier, less rational, more reactive brains (as per Daniel Kahneman’s metaphor of having two brains, one fast and one slow) is to take mental shortcuts wherever we can, to let other people make difficult decisions and take difficult actions upon themselves, especially if they present themselves as strong. We are capable of thinking and acting for ourselves—but it’s often easier to defer to authority, especially when authority begs, pleads, and cajoles with us to give them that deference.

In the decades after the American Revolution, writers gave a lot of thought to what this new country could be, and what kind of mind and soul was required to make good the promises of our founding documents. Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography of the personal virtues he tried to practice and perfect, starting in earliest childhood—virtues that aligned neatly with those of the Roman Stoics who many of the Founders admired for their ability to lead calm and self-directed lives. Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote compellingly about self-reliance and what was required to break free of the constraints of history and the expectations of one’s neighbors. “Trust thyself,” he said. “Every heart vibrates to that iron string.” Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” made reliance on one’s own spirit in the face of history and convention something nearly religious. Frederick Douglass, in his famous Fourth of July address, challenged White America to live up to its founding principles and face its hypocrisy in denying those ideals to so many people living on these shores.

All of these thinkers and writers were focused on the new-ness of what they saw in this country—in actuality or at least in potential. All of them saw the need to break free of old chains, old habits, old ways of doing things, if this was truly to become a new world, and not simply a transplant of the old world onto new ground. It was, to them, a project. It required doing. And to do something new required learning something new.

So: where should these habits be learned? Is it the job of American schools to explicitly teach these virtues or habits, as part of some kind of character education curriculum? If so, are we able, anymore, to agree on what those virtues and habits are, and whether schools have any right to teach anything beyond being, you know, nice to each other?

Should these virtues and habits be taught more implicitly, by exposing students to the essential writings of the 18th and 19th centuries, that helped delineate these idea? That seems like the proper role of schooling, and fairly uncontroversial. But how many of our high schools or middle schools are still teaching those writers?

It’s not just about certain Progressives in education deciding that Dead White Men need a downgrade in our curriculum. The mere fact that the stuff is old frightens many teachers (and publishers) away from doing more than publishing a fragment or a summary.

When the Common Core State Standards were being rolled out, I led some workshops to introduce teachers and administrators to the standards and to some of the test questions being developed to assess those standards. Because of the reading standards’ focus on close reading of complex, informational text, and the importance of reading such texts in the academic disciplines and not just in English class, one of the sample assessment items included a passage from John Locke, which students were asked to compare with the Declaration of Independence, to discuss the ways in which Jefferson’s thought was inspired and informed by the earlier, English writer (and the ways in which Jefferson varied from Locke). The audience reacted with, I think it’s fair to say, outrage. How dare the test-makers throw something that long, that complex, that OLD at our students? There was no way their students were going to be able to handle that reading load on a test.

Was this outrage…outrageous? No, in some ways it was perfectly justified. Rolling out a new, more challenging set of academic standards for 13 grade levels and expecting the oldest students immediately to meet those standards, without the benefit of having grown up under them, was foolish. A sane system would have introduced the standards at Kindergarten and then added a year’s worth of new expectations as that cohort grew. But that would have required 13 years of sustained political conviction and capital, which…we don’t have.

On the other hand, was it really outrageous to expect 17 and 18 year-olds, young Americans at or near voting age, to be able to grapple with the foundational texts and ideas of their nation? If so…why? I know the standards were new, but why was the gap between the old and the new so profound and challenging? Why had we stopped expecting young people to be able to read at the same level that Franklin, Jefferson, Lincoln, Douglass, and others had written? We still teach Shakespeare (badly, mostly, but still); why is that required and expected, but John Locke is considered a bridge too far? Why was that something new and strange, that students would never have seen before?

This is not merely academic or pedagogical. A strong America needs to be able to understand its own history, and to be capable of reading it in its original voices. A strong America requires people able and willing to identify propaganda, race-baiting, and tribal divisiveness, and to reject it—because it knows what its values and beliefs are. A strong America requires people who know when they’re being played—when they’re being seduced into hurting “others” who are actually just their neighbors. A strong America, upon learning that an adversary nation is trying to influence and upend its elections, should be able to reach across political divides, unites as a country, and says, “Hell no.” A strong America would not wave enormous flags and build golden idols bearing the name and face of a mere political candidate, as if that candidate were God himself, or the avatar of the country.

That has not been this nation. Not in a while.

If we had been taught right, we would know better, and we would say No. It’s as simple, and as difficult, as that.

Ignorant, deluded, fearful people who are easy victims of xenophobia and conspiracy-mongering are not caring neighbors, are not good protectors of their communities, and are not truly free. Citizens who are strong, smart, self-reliant, independent, and hard-to-fool are tricky subjects for bad people to lead, which is why so many of those bad people are happy to see so many citizens ignorant, deluded, and fearful. I call that un-American.

It can’t be the job of schools alone to mold our young people into strong and free Americans. Families matter hugely. What gets said around the dinner table (if anyone eats at the dinner table anymore) matters. Churches, mosques, and synagogues matter. Community civic organizations matter. So much matters. Only the whole community can make the whole community strong.

The whole community. Every child, every family, every religion, every ethnicity, every gender expression, every way of loving and living. Us.

November 22, 2024

[Re-post] Actually Existing People

Because of the “normal distribution” post that I republished last week, and because of the recent, utterly cruel, cynically political posturing of Nancy Mace around trans women and bathrooms, and because of the beautiful film that Will Ferrell made about his friend, Harper Steele, I wanted to follow up with another repost, of something I wrote in July of 2023.

If you haven’t seen Will + Harper , on Netflix, you should. It’s a kind and funny and heartfelt look at an enduring friendship, and what it means to truly know someone, and how you can think you’ve known someone for decades without really understanding their heart, and how brave and scary it can be to reach out and ask the hard questions you never bothered to ask before, and how brave and scary it can be to open yourself up to show yourself to another person—even an old friend.

Are there tears? There are some tears. Are there hard scenes with ugly people? There are a few. But there is also a ton of love and empathy and understanding—some of it coming from places and people that might surprise you.

The film reminds us that this country is not filled with MAGAts or Snowflakes or Wingnuts or Libtards; it’s filled with people—quirky, individual people—actually existing people, most of whom are just trying to live their lives in peace and freedom and dignity and safety. Which is what made me want to revisit what I wrote here, a year ago.

It was sometime in my twenties when I finally started to notice that our news media provided descriptions and qualifiers for some people, that tended not to be used for other people. If a man being reported on was Black, he was identified as such; if he was White, race wasn’t mentioned. If a woman was being reported on, her clothing and hair were described; if it was a man, those things were omitted. These descriptors said to readers, whether they consciously realized it or not, that certain things were “normal” and therefore not worthy of comment, and that anything outside of that norm needed to be described to ensure understanding. Race was invisible unless it was a particular race; gender was only noteworthy if it was female. White and male was simply “regular”—the default setting of human—or, at least, American.

And yes, I probably should have noticed this much, much earlier. Shame on me.

We all should have noticed. But prior to the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements, most of the people being talked about in newspapers were White males. And let’s get real: is it easier to drop all the modifiers if everyone you’re talking about—and everyone you’re talking to—shares them? Of course it is. So, if the newspaper is a record of what members of the club are doing, meant only for other members of the club to read…how much detail do you really need? It’s understood. It goes without saying.

Note to self: Beware of what goes without saying.

Now, of course, we’re more inclusive—or, at least, we try to be more inclusive—or, at least, we’re aware when we’re not doing such a great job of it. We know that being in the majority doesn’t mean you’re the only thing that exists. There are Actually Existing People all over this country who do not fit into one majority group or another. We get that. But when we use language to frame reality in a way that excludes people, we make it too easy to think of them not just as members of a minority group, but as quasi-humans, people who are abnormal, outlying, not part of the tribe: wrong. And once you have done that to a group of people, it becomes easy to do other, more terrible things to them.

I mentioned last week how people like Todd Rose have showed us how un-meaningful it is to be bunched around the mean value of one or two traits or behaviors. There are more of us there; that’s all it means. But when there are more of us, we assume we’re in the right. We can’t help ourselves. When you’re a kid at the school bus stop, it’s hard not to think less of the kid who stands by himself on one corner, because he’s not part of the crowd bunched on the opposite corner. To be alone is to be the loser. This is how we define everything.

Our “the majority owns the normal” framing encourages othering, even though the fact of being a few standard deviations away from some mean value has, in itself, no moral or ethical value; it simply says that whatever it is, there is less of it in the tails than in the bulge. But remember: there are a lot of “its” that make up the whole. No one represents the absolute mean of all traits and values. The “100% normal” is a null set—no one is there. Someone you think of as a freak or a weirdo because of one aspect of their life might align perfectly with you, and with the majority of people, in some other aspect (and that guy who looks and dresses and talks just like everyone else might be keeping some disturbing and dangerous behaviors secret).

Regression to the mean is not a sign of righteousness. Anything existing along a continuum is part of the data set, as I wrote last week. It’s all a part of who we—the big we—are. I may be waiting by myself at the bus stop, but we’re all getting on the same damned bus. Why does it matter where I stand? Or what kind of coat I’m wearing? Or who my parents are married to?

In elementary classrooms, teachers have pictures of their spouses on their desks and make casual mention of their families as part of class discussion. It happens all the time. Teachers ask questions about the families of their students. And all of this is fine…as long as the spouses and parents are heterosexual. But if the same things are done in reference to a same-sex spouse or parent, it’s considered (in some parts of the country) dangerous, provocative, and an act of deliberate “grooming” of young people, to get them to change their gender identity or sexual attraction.

As if casually talking about your weekend could effect such a profound change in anyone.

Gay teachers and parents, and their same-sex partners, exist. THEY WALK AMONG US. So do trans men and women. So do gingers and vegetarians and Presbyterians, by the way. Acknowledging and validating the existence of gay and trans people shouldn’t be a threat or a challenge to the sanctity of anyone’s family, any more than a Jewish teacher talking about Chanukah should be a threat or a challenge to any Christian’s faith. We got over that fear (mostly). We can get over this one. Not everybody is the same or does the same things. That makes zero demand on the rest of us. I’m having tacos for lunch. You do you.

I’m trying to understand why “you do you” is so threatening to some people—why “live and let live” seems to be acceptable only up to the point of “it makes me feel icky,” and then must be stopped by legislation.

I do understand the moral panic that some parents are feeling over the recent increase in visibility and acceptance of trans men and women. I think it’s misguided, but I understand it. Some of them seem to worry that acknowledgement and acceptance have led directly to a spike in children identifying as gay or trans—that it is a causal relationship: someone is making my child into something they’re not. But can popular culture really cause straight young people to become gay or trans? I mean, it hasn’t made any gay kids straight.

Or does acceptance simply allow gay and trans children—already existing gay and trans children—feel safer about sharing who they are and what they’re going through?

Honestly: do people really think our culture is creating new gay people out of straight people? Do they think “trans” is some cool, new, cultural product that the 21st century invented, a lifestyle so sparkling and attractive that kids can’t resist adopting it?

Or is it more likely that our language and the weight of our biases invisible-ized entire swaths of people for generations, making it difficult for us to see them and making it dangerous for them to show themselves?

I am thinking of someone close to me who suffers from Depression: capital D, clinical, chemical imbalance Depression. When she first talked about it with her mother, she discovered that she was far from alone: her family was riddled with Depression, going back generations. But it was never spoken of, never discussed. It was shameful. Not just in her family—across the whole culture. And so, it remained invisible, and each sufferer had to suffer tenfold, alone and in silence.

Is that level of suffering really justifiable, if the only reason for it is to make sure other people don’t feel uncomfortable?

It seems to me that, at most, cultural acceptance is leading some young people to investigate and experiment and ask questions. Is that a crisis? Investigation and experimentation are what young people do. It’s what adolescence is all about. Whether it’s alcohol or drugs or gender—or skateboarding, for that matter—anything teens are curious about and hungry for, trying to see if it resonates with them, can be done safely, or it can be done dangerously.

I don’t know where the lines should be drawn when it comes to things like body dysmorphia and gender affirming care for young people, or who should be drawing those lines. Let’s have that discussion. Having raised two kids, I’d probably defer to safety most of the time. But mental health is part of the safety equation. Either way, I wouldn’t want the decision legislated for me by people my children have never met.

Isn’t acknowledging and accepting what actually exists in the world the best first step towards having sane discussions about people’s desires and choices?

The MAGA types, with their eyes fixed firmly on the past, seem to think that the Actually Existing world of their childhood was wildly different than our current world—that certain things and people they find problematic simply didn’t exist back then. But that’s nonsense. There were always Black people. There were always Jews. There were always gay and trans people. Just because they may have been kept out of sight doesn’t mean they weren’t out there, actually existing and trying to live their lives. What changed was our framing and our language (and then our laws). We can see people better now, and that makes some of us uncomfortable.

Maybe part of the discomfort is the understanding, deep down, that gay and trans who seem a tiny bit happier and more comfortable now were always among us, silenced and immiserated by our prejudices and fears.

Our children are not being changed into something they never were. They're just feeling safer expressing who they are, or asking questions about who they might be, because our old, constrained, only-the-bulge-in-the-center-is-real way of thinking is changing.

The rainbow has always been there. All of its colors have always been there. The fact that we used to see the world in black and white doesn’t mean the world was binary and limited; it just means we were.

November 16, 2024

[Re-post] The Normal Distribution and the Act Like a Man Box

I've been thinking again about "manhood" and what it means—or what we think it means—to be a man. I was thinking about it a year ago when I first wrote this piece, and I’m thinking about it again today, in the midst of this era of tech bros and podcast bros and overly-pumped-up, heavily tattooed bros yelling at everyone else about what Real Men do and say. The Bro-ocracy is bringing me down. I need a little more The-Dude-Abides in my world.

I am not a psychologist or a sociologist or any other kind of -ologist qualified to say anything with authority. Let me put that our there right here at the top. I’m just a guy, thinking out loud. I'm a guy who has been a man for his whole life and a father of two men for nearly 23 years. But that's all I am, so...caveat lector.

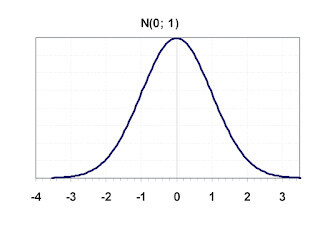

What I keep thinking about is: what is normal? Statistically (I’m not a statistician), normal is not a single thing; normal is a distribution around a mean. We’ve all seen the “bell curve.” To be formal about it, according to this statistics website:

The normal distribution is a continuous probability distribution that is symmetrical around its mean, most of the observations cluster around the central peak, and the probabilities for values further away from the mean taper off equally in both directions.

A “continuous probability distribution” feels very quantum-physics-y to me in its suggestion that reality is less concrete and fixed that we perceive it to be—more wave than point, more probability than certainty. (I’m not a physicist—these are all just the ramblings of a promiscuous and fairly dilettante-ish reader.)

Todd Rose tells some amusing anecdotes, in The End of Average, about times when we have sought an actual individual to represent the “average” of a set of qualities representing manhood or womanhood. In both cases, the search came up empty. There was no single person who represented all the mean scores of all the manly or womanly qualities; the pure middle was an empty set. We are ‘jagged,” Rose says. One fact doesn’t always carry with it all the other facts that may adhere to it in the mean.

Qualities exist across a continuum, and they bunch and gather around the mean. Imagine a normal distribution of traits and behaviors that we have historically thought of us “masculine,” with the more feminine at the left-hand tail and the hyper-macho at the right hand-tail. (I’m making this up.) Most men might bunch and gather around the mean as aggregates of behavior, but if you isolated particular behaviors, or attitudes, or affects, our individual scores might be all over the place. That’s what makes us jagged individuals.

That’s what makes us individuals, but we socialize ourselves and each other pretty hard, as men, to fit ourselves snugly inside what Rosalind Wiseman calls “the Act Like a Man” box. There is one acceptable way to be a boy or a man—deviate from it at your peril.

We’ve been raised with some pretty hardcore, binary thoughts about gender and sexuality. “Normal” men are one thing, feel one thing, behave one way, are attracted in one way to one opposite sex. Anything that deviates from that “normal” is, by our definition, deviant. But the reality is that “normal” is a cluster of things hovering around a mean, not a singularity where all things meet. If there is such a thing as mean masculinity, it exists only because most cases of Actual Men hover around that point, at locations somewhere to one side or another of that mid-point it in equal measure. In other words, not all men are exactly X in all things (or in any things); some men are a little X+ in certain traits or on average (meaning to the left of X, not better than X) and some are a little X- (meaning to the right of X, not lesser than X); some are a LOT X+ and X-.

But what have we men done? We have looked at that distribution and we have invalidated almost everyone to the left as being dangerously “faggy” or “gay.” Maybe only the tail; maybe almost all the way up to just short of the mean. Depends on the generation. But even in our relatively enlightened times, too many of us live in terror of anything to the left of the mean, and hope that we, personally, are never tagged as being in that group. But the extreme right? Oh, the extreme right is considered totally safe and viable: the hyper-macho, the toxic, the brutal—those are all considered permissible ways of being a man. So, we don’t just accept the cluster around the mean—we say “real men” exist at the mean and all the way out to the furthest extreme of only the right-hand tail, while anything even slightly to the left of the mean is dangerous and to be shunned. Tell me that’s not fear-based behavior.

Remember—the mean, the average, the “normal” would not exist unless there were equal numbers of cases on BOTH sides of it. That’s how the distribution works. Which means there are a hell of a lot of us to the left of the mean (in aggregate and also in a variety of individual traits). In fact, there have to be as many of us on the left as there are on the right! But we’ve decided to make invisible and untouchable any expression of masculinity that exists to the left-of-X. Those traits cannnot exist and must not exist in the Act Like a Man box.

Which is ludicrous, right? Because if the values to the left of the mean disappeared, the mean would shift hard towards the right. By definition. But we like to pretend that nothing to the left of the mean is part of who we are, and we reinforce that idea constantly.

Would gay men, measured alone, fall into the same rough distribution of traits and behaviors, or would their mean skew a little to the left? I don’t know. Would straight men pulled out into a separate group skew a little to the right? I don’t know.

What I do know—or sense, because, again, I have no expertise in any of this—is that all of this—all of it—should be considered a normal and ordinary range of human expression.

Why does that matter? It matters because people in the majority (the clump around the mean) like to pretend that minorities do not exist—or, at the very least, that their existence as minorities makes them less-than-worthy or less-than-real or less-than important. But remember: in a distribution, the extremes help to define the mean. And remember: so very, very much of life on earth falls into these kinds of distributions. For any set of values clumped around a mean, there are always tails at either end. They are not weirdos or deviants or wrong. They simply represent the tails—they are people with certain traits expressed less often than others within a particular population. But they are expressed. They are part of the data set. They are part of us. They help define us. They belong.

Again: go searching for the individual person who is a perfect representation of the average of all traits—Mister Perfectly Average Man, and you’ll come up with an empty set. There is no perfectly-averagely-masculine man. If masculinity were made up of 100 separate traits, none of us would register at-the-mean 100 times. We’d be a little to the left here, a little to the right there, a little further out in some areas, a little closer in for others. As individuals, we are all over the map—and yet, so many of us are terrified of allowing ourselves to vary. At. All.

There are as many ways to be a man as there are men. There is no box. There is no fucking box. We need to just stop. We need to let some air in and let each other breathe.

November 9, 2024

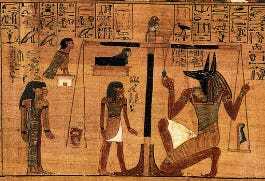

The Fickle Feather of Ma'at

Many people, in many times and places, have held beliefs about the afterlife and the ways in which actions and choices from life will be judged. The ancient Egyptians had the idea of your heart being weighed against a feather from the goddess, Ma’at. The Hindus had the idea of karma, where the actions in this life affect the kind of life you come back to in reincarnation. Some people believe in heaven and hell. Some people believe we make heaven or hell right here on earth.

In all of these belief systems, actions have consequences. Important consequences. It’s something we humans have figured out, pretty much wherever we’ve set down roots on this planet.

And, for just as long, we’ve tried to find ways to weasel out of those consequences.

Once upon a time…I was leading a project for a Major Urban School district, designing and creating a standardized curriculum to be used across all of its middle and high schools. My team was working closely with advisory groups of teachers from each subject area, and one of the things they wanted to know was how scripted the curriculum was going to be. My team was trying to get district leadership not to demand a fully scripted set of lesson plans, but, instead, to let us set weekly learning objectives aligned to the state standards, and then provide teachers with a variety of instructional suggestions, and the occasional model lesson, to use as guides. We felt this struck the right balance between the district’s need for more standardization and coherence across (and within) its schools, and the teachers’ needs for professional autonomy and the ability to deal with the needs of individual classrooms and kids.

Some teachers approved of this approach. Most said nothing, resigned to accept whatever they were given. And then there was this one English teacher, who nodded along as I explained things, and then said, “As far as I’m concerned, give me 180 scripted lesson plans and tell me what to do with every fucking minute of every fucking day, or leave me the fuck alone to do my job.”

He didn’t want those 180 scripted lesson plans, mind you. He wanted to be left alone. But somehow, in his mind, the misery of having his job reduced to reading from a script was preferable to being held accountable on a weekly basis to meeting certain goals and objectives. He wanted to do what he wanted to do, with nobody sitting in judgment. He felt—as many teachers I’ve met have felt—that he was accountable to no one’s judgment but his own, that no one was qualified to hold him to account for the instructional decisions he made.

But, wait—don’t most teachers have some kind of district-mandated pacing plan that they have to follow?

They certainly do. But many of those plans simply list topics to be taught, or larger standards to be addressed. They don’t break those down (or “unpack” them, as we like to say) into clear, measurable objectives that build towards broader goals. There’s a big difference between telling a teacher to “cover” something next week, and spelling out exactly what her students should know and be able to do by the end of that week.

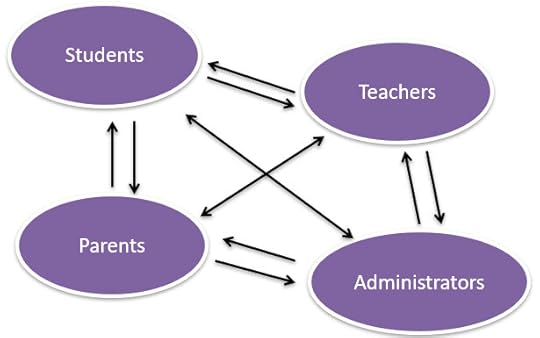

We’re talking about accountability here, in case you missed the subtitle of the post. And accountability is one of those things that people claim to love, as long as the eye of judgment is pointed at somebody else.

What is it?When we talk about accountability, we’re usually talking about one of two things: making sure people have done what they’ve promised to do (or been asked to do), or imposing some kind of consequences on them (good or bad) for what they have done or failed to do. “Hold them accountable” can mean either of those things—oversight or consequences. Because so much weight falls on the “consequences” part, and so many people do the “oversight” part poorly or haphazardly, the entire idea tends to feel punitive and something to be avoided at all costs. For a brief period when I used to lead workshops on the topic, I would start by asking participants to list all the words they thought of when I said “accountability.” The words they listed were always, without exception, negative.

Henry J. Evans, in his book, Winning with Accountability, tries to present the idea in a more positive light. He says that the word means, “Clear commitments that, in the eyes of others, have been kept.” To him, accountability is not a uni-directional thing, but is, instead, a relationship. If you are my manager, it’s not just that you hold me accountable for meeting certain goals; I also get to hold you accountable for setting goals that are clear and achievable.

And that ought to be a good thing—a positive thing. I want to succeed at my job, after all, and it’s hard to do so if I don’t know what the job is or what my manager needs from me. A healthy accountability relationship should make both partners happier. In theory.

How to be clearSetting clear objectives doesn’t mean speaking louder, though some managers seem to think that’s all that’s required. Clarity means helping the other person succeed by letting them know exactly what you need, and what “good” will look like.

That’s not as easy as it sounds. We use a lot of slippery words in everyday speech—often without realizing it. We say, “get it to me soon,” without specifying what “soon” means to us. Maybe I think ten minutes is soon enough, but you think an hour is sufficient. If we walk away from a conversation holding those two, separate ideas, we’re going to end up in a bad place.

Is “end of day” any better? Maybe. But is that the end of the working day, or the end of the calendar day? Your time zone? My time zone?

AND: If I ask for something by the end of the day, but I have no intention of reading it until tomorrow morning, wouldn’t it be better to say, “on my desk by 9AM,” to give you that extra time to work on it, if you need it? Why make a demand that actually doesn’t matter?

All sorts of words and phrases can be traps—requests that require people to read our minds, and that punish them if they fail. If we want people to succeed—if we want them to give us what we need—we need to think carefully about what we’re asking for and how we’re asking:

Or, for example, “I’m going to make America great again,” or, “I’m going to stop price gouging.” Empty promises? Maybe, maybe not. It’s hard to tell when the language is so vague. Neither of the statements is a “clear commitment” whose successful fulfilment other people would be able judge. Who’s to say what “great” means? Who’s to say that a price reduction is deep enough to no longer be considered “gouging,” or if the high price was the result of gouging in the first place? Which is precisely why politicians like to use this kind of language. They can claim success using whatever criteria they feel like using. They can move the goalposts. They can invent goalposts that never existed before. That’s part of the game.

In our lives, if we want to demand clear commitments from other people, and if we want to be successful at delivering on the commitments we’ve made, what would better language look like? Instead of asking for “a proposal,” should you specify how many pages, what font size, what the title should be, how many sections it should contain and what each section is, what the introduction should state, what the core arguments are, and so on? Would that make clear what “good” looks like?

I mean…you could do that. That’s the 180 lesson plan approach. But it’s an awful lot of work for you, and it makes the other job pretty lousy. That’s micromanaging, not managing. And nobody enjoys that.

There’s a sweet spot in between the extremes of micromanaging and, well, abandonment. You could paint a picture of what you’re looking for. Maybe something like, “I need a proposal to submit to the board, to explain what the project is, why it’s the right idea, and why we need the funding to do it this year instead of next. They love data, so give them some real examples of what we could accomplish and some decent numbers on ROI, if you can get Sales to commit to anything. Ten pages, tops, with a solid executive summary, because half of them will only read that.”

Will your employee know how to give you what you want? Probably. You’ve given them the tools they need to succeed, but you’ve also given them space to figure out the best way to get there. They get to make some choices, using their skills, their intelligence, and their creativity. And they get to be held accountable for the wisdom and efficacy of the choices they make. In a setting like that, people who make better choices—who deliver better and more interesting results—get to rise and prosper. The micromanaged mice, not so much: they all deliver exactly the same thing. The only way they can distinguish themselves is to do it faster and with fewer complaints.

Freedom within clear boundaries and directions is what we wanted for our teachers back in the day—and it’s precisely what that English teacher did not want. He wanted success on his own terms. He wanted success without any terms. He wanted to be left alone to do as he pleased—the Byronic hero of education, facing the challenges of the world alone. But how many people get to live like that? How many people should?

What do we owe each other?A healthy organization—or society—is one that has a culture of mutual accountability, with two-way arrows connecting all the stakeholders to each other—a web or network of accountability relationships. In a school, it might look something like this:

In my workshops, we would talk about each one of these arrows, and what each “stakeholder” in education actually needs from the other. There’s a lot going on in this web, and most of us don’t give it a thought.

And this isn’t even the whole picture, Widen the lens and you can include local, state, and national policy makers and elected officials. We are all connected to each other; we all need things from each other in order to succeed—even people we’ve never met. We all owe each other something.

Let justice be doneThat’s all well and good, but what about the tough part—the consequences? What about bringing down the hammer? That’s the part people focus on most often, which is why we hate the whole idea of accountability.

Look, we all know there have to be consequences in life. There’s a difference between freedom, which has some limits (if only to avoid infringing on the freedom of others) and license, which is just reckless abandon. Supernanny taught us what happens to children when parents are afraid to set rules and boundaries and then enforce them. Chaos is what happens. Willful, unhappy children, and exhausted, miserable parents. A society of id-monsters running around, doing whatever they want, to whomever they want, is a nightmare, and societies don’t like to live in a nightmare for long. If we can’t hold each other accountable in a civil society, we don’t end up in a chaotic state of nature; we end up in a police state.

When we impose consequences on children, we do it to teach them, not to punish them (in theory). For adults, who are supposed to know better, it’s more of a mixed bag. We may set consequences to help the wrong-doer learn how to do better, or to warn other, potential wrong-doers to think twice. Or we may do it simply to punish people and satisfy a thirst for retribution. You must pay for what you have done. Justice must be done.

Come what may? No matter the cost to the rest of us? Some would say Yes.