Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 2

July 11, 2025

A Standard Take on Writing

Free-for-All

Free-for-AllSometime last year, I read a post from a high school teacher who was fed up with assigning and grading five-paragraph essays. He found them banal and drab and uninteresting, and he found it difficult to give students meaningful feedback. The whole task was drudgery, he felt—for him and for his kids.

I felt his pain. Bad writing assignments are a plague. Students hate them; teachers hate them.

This teacher’s solution? He said that as far as he was concerned now, the kids could write anything they wanted, any way they wanted, because self-expression and self-actualization were more important than conforming to some ancient and arbitrary structure of writing that no one really cared about. Enough! The new writing syllabus became, “you do you.”

How that was meant to be different from what his kids did on their phones all day outside of school? He didn’t say. Maybe he didn’t care. Maybe he felt that, at the exalted age of whatever they were—15?—they were as adept at written communication as they needed to be.

Also, he had nothing to say about how he intended to grade those assignments or give feedback on them. Maybe he wasn’t going to. Or maybe he was going to reserve the right to be just as subjective and random as they were. You do you; I do me. I don’t know.

As you can tell, I found the whole thing depressing. I didn’t respond to it. I just pushed it to the back of my mind and let it sit there for a while, because it was the holiday season, and I had a kid getting ready to go back to college, and there was probably laundry to do, and…you know. I was busy.

But I know why I found it depressing. It felt irresponsible. I know teachers are still grappling with post-COVID learning loss. I know they’ve been forced to carry more of the burden of character building and moral instruction and self-esteem building and a hundred other things. But none of that changes the fact that one of the critical jobs of an English teacher is to make sure that a student can put thoughts to paper—thoughts, not just emotions—and can do so effectively for a variety of audiences.

Let’s not get into the whole issue of kids using AI to do their writing. I’ve opined on that before, and it’s a whole different conundrum. Let’s stay focused on the topic of actual human students doing actual human writing to express what they actually have learned (which I have also written about before).

I have no objection to, “write whatever you want” (not true—I have some objections), but I have real objections to, “write it however you like.” I’ve seen a lot of that in schools, and, as I said, it feels irresponsible. It surrenders the need for instruction. There’s no “right” way to do anything, so don’t worry about it. Whatever you come into the classroom with is what you’ll leave with. That feels like we’re cheating our children. And it puts all the burden of comprehension onto the reader. It says, “I’m expressing myself my way. If you care, you can do the work required to understand it.”

In other words, it’s a free-for-all for students, which is not free for the rest of us. Readers pay the cost. And that’s not right.

No one owes us their attention, and they certainly don’t owe us exertion just to understand us. If you want to be heard, you need to speak clearly. You need to do the work. And the “work” has to be something that works for anyone or everyone—communicating in a way that a variety of audiences will be able to understand—expected audiences and unexpected ones—known readers and unknown readers. Anyone. The whole benefit of written communication is that can reach people beyond your circle of friends—beyond shouting range. Which is why teaching some standard formats and genres and rules of writing matters.

It’s why standards matter, all around.

What is the Standard?In ed-world, we’ve come to think of standards as mandates or requirements or goals or objectives: dreary and burdensome things that creative and freedom-loving people dread and resist. But in the rest of the world, a standard is simply an agreed-upon unit or process that allows large groups of people to work together smoothly. It is meant to lift burdens, not add to them.

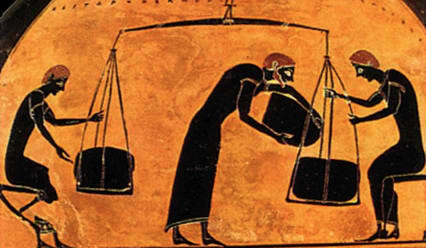

We use standardized weights and measures. They allow us to understand what we’re buying at the grocery store, how to make a recipe, how to construct a chicken coop—all kinds of things. Cultures have sought to standardize things like weights and measures for ages; the earliest examples stretch back to the third and fourth millennium, BCE. I don’t hear people bitching about the tyranny of the inch.

When objects and processes we use in everyday life are not standardized, things like building and crafting can be wildly idiosyncratic, or deeply mysterious, passed down individually from master to apprentice. The only right way to do a thing is the way your Master did it.

There’s nothing wrong with that old method—it captured and communicated time-tested methods and processes in many times and places. But it kept knowledge secret and special. Only certain people knew how to do certain things (and those people often formed guilds to protect their monopolies). Standardization is the process of collecting, sharing, and formalizing the things that work, so that everyone can make use of them.

We like standardization. When we have to deal with things that aren’t standardized—like USB plugs in the early days, like VHS vs. Betamax in the early days—it irritates us to no end, because, just as with the writing example above, it forces us to do the hard work of making things make sense. We have to figure out which thing to use, or which process to use, or how some wacky genius decided to put the puzzle pieces together this time, for this product. It’s not bad, per se; it just makes more work for us. It’s annoying. That’s why we (eventually) standardized spelling—so we wouldn’t have to stare at a word and say, “what the hell is that supposed to mean?”

The essay—even the dreaded five-paragraph essay—is a just a standard format for communicating ideas and arguments in writing. It’s a vehicle for carrying information in a logical and structured way. It comes from the French word meaning, “to try.” It’s a structure for trying out your ideas—taking them out for walk along a logical, linear pathway that other people can follow.

Most people are familiar with the essay and know how to navigate it—if not as writers, then at least as readers. We know where we’re liable to encounter the central argument or point of the essay. We know how that thesis is going to get broken down and argued or explained. We expect it to be get broken down. We expect it to be argued or explained. Here’s what they think; here’s why they think it; here’s why it matters. It’s a highly efficient vehicle for delivering arguments and ideas into our brains.

It’s not an exciting structure; structures are rarely exciting in themselves. You can season a pita chip all you like, but its main purpose is still to scoop up something tastier and deliver it into your mouth.

The essay is the pita chip of rhetoric.

If we find the structure boring, it’s probably because we’re using it in boring ways and refusing to scoop up interesting ideas with it. The topics we force students to address may be putting them, and us, to sleep. If teachers are getting boring essays, it may be because they’re assigning boring topics.

It may also be because teachers are using the entire essay as their unit of instruction, which makes focused feedback hard to give. They feel like they have mark-up entire papers, all the time, and it’s exhausting. It’s exhausting and frustrating for kids, too. What are they supposed to do with all of those red marks on papers or track changes on screens?

If these teachers (or their predecessors in earlier grades) have skipped over the writing of sentences and the crafting of paragraphs, there’s only so much they can say about the essay as a whole. We need to spend much more time, even after elementary school, talking about what makes for a powerful sentence, a beautiful sentence, a compelling sentence—experimenting with how word choice and syntax and rhythm can affect meaning.

Likewise with paragraphs. When I was teaching, it drove me crazy to get two-sentence paragraphs from kids—a topic sentence plus a sentence of support. The end. It was my own fault, though, because I hadn’t really taught them what a paragraph could do—what it really meant to elaborate on and explain an idea, or how one could explore supporting evidence. I didn’t know enough, myself.

At least I never told them that the only important thing about a paragraph was that it had to contain five sentences.

Another problem may be that we’re using the essay as the only form of communicating ideas in writing. Imagine if teachers had students address the same topic using different writing methods, one after another: an descriptive essay about the autumn, followed by a short story, followed by a poem or a song lyric, to help students understand the unique powers and limitations of each form of writing, and how each can unlock and bring forth different ideas and feelings on the same topic.

Language is a flower and a prayer and a weapon, and all day long, we reduce it to a mere task.

Short-Circuiting ThoughtHOWEVER.

The convenience of learning how to use a standard structure or process can sometimes short-circuit thinking. It can encourage students to work by rote. We teach standard algorithms for problems-solving in mathematics to help students get to a solution faster: a particular way to do long division; a particular way to multiply multi-digit numbers, and so on. It’s not unusual for students to become proficient at executing those processes without really understanding, conceptually, why they work or what, mathematically, is really happening (I speak from long, personal experience). This leads to a kind of limited fluency that can hit a wall as soon as the math becomes complicated. You’re doing, but you don’t really understand what you’re doing.

Are essays similar? Do students paint by numbers without really thinking about what they’re doing? You know they do. There’s a reason the teacher I mentioned at the top got bored with the essays his kids were writing. Getting kids to do is hard enough; getting them to think about what they’re doing can be seriously challenging. But that kind of self-reflection and metacognition is where real learning happens. And a lot of that happens in the act of writing.

Students think writing is a chore that they’re forced to do only after they’ve learned a thing and know all about it, but that’s not true. Often, we figure out what we think by writing about it. We don’t really know until we tell ourselves. The first audience we have to communicate with is ourselves.

How much have we downgraded this important art and craft? There are kids in college today who are having AI read for them, summarize for them, and write entire papers for them. For all I know, there are professors using AI to grade those papers. The humans may be left entirely out of the equation.

(New Yorker Magazine, June 30, 2025)

Doesn’t it make you wonder: what’s the point of being in that class? What’s the point of being in college at all?

Children don’t enter our school systems bored, bland, and incurious about the world. If they end up that way, it’s our fault—at least in part.

Their innate, hard-wired curiosity is our raw material; what we do with it is up to us.

July 3, 2025

[2025 Re-Post] The Country in My Head

Re-posting with some additions on the eve of a dark July 4.

America has always been an idea as much as it’s been a place, and I know we don’t all hold the same idea about what it should be. That becomes more and more evident to me every day. What follows are some thoughts on the ideas I grew up with and still hold onto, and the Culture Things that communicated them to me in my youth.

I’ve been thinking about the things I carry.

I’m not a pack-rat or a hoarder, but there are ideas and pieces of culture that I hold close and seem not to want to part with, even when the larger culture announces that they’ve have hit their sell-by date and should be discarded. How I think about my country (what it is and what it should be) seems to be one of those things.

My feelings are probably not progressive enough or conservative enough for other people’s tastes, neither sufficiently patriotic nor sufficiently critical. But whatever those feelings are, they’re mine. And I’ve been thinking about where they came from.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

As a card-carrying member of Generation Jones, I’ve always had a complicated relationship with patriotism. My parents were Depression babies and Eisenhower teens, coming into their own during the post-war, American-Century boom and settling down to raise children while Vietnam raged oversees and the Woodstock era exploded at home. Whatever they thought and felt about their country was never spoken out loud when I was a child, but it was certainly part of the air I breathed, in the same way that their Breakfast at Tiffany’s New York would never be mine to live in, but was always mine to dream about. I inherited their world, even as it was disappearing or changing.

Other than seeing hippies on the streets during our summer vacations, I was a pretty oblivious child. I did watch the Watergate hearings with my parents and I did understand, at least in general terms, that Something Was Terribly Wrong. In middle and high school, I paid only occasional attention to politics, looking backward at the 1960s more than I looked around at my 1970s, caring more about Monty Python and The Beatles than about our presidents. I got my current events news from Doonesbury comic strips. I was a casually liberal, suburban, New Yorker in the making. Doonesbury taught me, but so did movies like In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird and Inherit the Wind. I knew what boxes to check: Vietnam, bad; Watergate, bad; Nixon, bad; Reagan, bad. FDR, JFK, MLK? Good. Freedom of Speech? Excellent. The presidents up on Mount Rushmore? Classics. The American Dream? All for it.

As I moved into my college years during the Reagan Administration, the Boomers ahead of me moved into their thirties and beyond, many of them transforming into “Greed is Good” Yuppies. At every stage of life, they had defined the larger culture, and in this moment, the culture was all Big Chill: solipsistic nostalgia, curdled idealism, and early-middle-aged excuse-making. All that cool and groovy peace and love stuff of their younger years—all the anti-war passion that I had relished—was it all just…nothing? If they, who had seemed to care so much, no longer believed in anything except themselves, what were we, their more sarcastic, younger siblings, supposed to believe?

And yet, the idealism never quite curdled in me. That base-layer of Eisenhower-y boosterism, or old Hollywood idealism, or middle-class, Jewish striving, all of that stayed with me, colored and enriched and informed by movies and music and books I had surrounded myself with as a child.

It was definitely a weird grab-bag of culture: Classical music, Broadway show tunes, Dixieland Jazz, Rock & Roll, and protest folk music; the film noir and WWII movies that I watched at home with my father, and the zonked-out, counter-culture films that I watched with my friends at our local art-house theater; James Thurber, but also Kurt Vonnegut; Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but also Hunter S. Thompson. I knew some of the art had been created to challenge and cancel what had come before it, but none of it did so in my mind. There was room for all of it, and all of it, together, told me who we were: My Country, ‘Tis of Thee, but also, Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.

We were allegedly a cynical and self-centered mini-generation—the wedge that led to Generation X—and yet, when we, as young, married couples in New York City, stood in stunned, silent shock after 9/11, we reached back to the patriotic songs we had learned in our childhood. We stood on the stoops of our Brooklyn brownstones, holding candles aloft at sunset to honor our fallen firefighters, and we sang those corny old songs, like It’s a Grand Old Flag, and, yes, My Country, ‘Tis of Thee. Because that’s what those songs were for; that’s why they had been taught to us, even in the midst of political and cultural upheaval—so that we could have them when we needed them. And on that day, when we needed them, we didn’t sing them mindlessly, or with uncomplicated feelings. But we sang them.

That was a whole generation ago (which blows my mind). What songs do the new, young marrieds in Brooklyn have stored away in their memories, to bring out when the storm clouds gather and the skies grow dark? What cultural artifacts have they put in their mental libraries to form a sense of home and country, when both are threatened? Do they have what they’ll need to bind them together and keep them warm in the cold days—something heartfelt and hopeful? Or is it all just criticism and cynicism? I don’t know. Maybe it’s naïve and old-fashioned even to ask the question.

When I think about the bits of art and music and poetry that formed my sense of self and country, I wonder if any of it still means anything, or if it’s all just Eliot’s “heap of broken images,” leaving me, in late middle-age, with nothing but fear and a handful of dust. Is it all outdated, outmoded, and dead? Or are some of those fragments still vibrant and meaningful? If they’ve lost their kinetic energy, do they still have any potential locked inside? Could they be seeds holding something good—seemingly inert, but filled with the essence of life and able, if nurtured, to grow and flower again?

I don’t know. Maybe they’re just shards of useless, colored glass, or broken Hummel figurines of the kind that our grandparents used to collect—old and musty and a little embarrassing, best swept up and thrown away. I suspect that’s exactly what they are to most people in my children’s generation. And that makes me sad, because there were things in that heap that I valued.

I guess it’s not up to me to say what any of it will be worth. I’m a Hummel figurine, myself, or rapidly becoming one. The future will take what it needs and discard what it doesn’t need, as it always does.

Either way, here are a few shards from the world I inherited and grew up in—some of the bits and pieces that told me who we were, or wanted to be, or could be. It’s not a complete list, and it doesn’t paint a complete picture. It’s just some stuff from the attic that I’m airing out. Make of it what you will.

Henry David Thoreau

Because he thought new and uniquely American thoughts, and he said things like:

I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward.

Still seems kind of relevant, doesn’t it?

And also:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

I know—his “woods” were barely a day’s walk out of town. But at least he tried—at least he understood that to do something new, or at least think something new, you needed as much of a tabula rasa as you could manage for yourself.

And maybe this wasn’t new, but it mattered: we were not born simply to endure lives of quiet desperation.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Because he taught us to rely on ourselves, not the dead hand of history; He reminded us that a foolish consistency and conformity are death.

Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think.

I once gave a big, bruising, anti-racist-skinhead student the essay, “Self Reliance” to read, and he told me that it spoke to him so much that he took it home and quoted portions to his mother, who finally understood her son and knew how to be his ally. Don’t tell me that our kids can’t read and shouldn’t read our foundational texts. How are they supposed to have a foundation if they don’t?

Pete Seeger

I listened to him as a child because my mother loved him. I’m not sure I understood that they weren’t children’s songs, even though some of them were about children. They are tough songs—call-to-action songs—but they are always bright and positive and forward-facing songs that believe in a better world...if we’re willing to make it.

Alice’s Restaurant

Because it took place where I spent my summers, and I was there, oblivious but somewhere down the road while it was all happening. And because, when I finally came to read Thoreau and Emerson, I understood that what Arlo and his friends were doing was not unique or threatening; it was their cultural heritage, whether their elders understood it or not.

Langston Hughes

Because he understood what this country was, at its absolute worst, and he insisted that it live up to what it could be, at its best.

O, let America be America again—

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where every man is free.

The land that’s mine—the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME—

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain,

Must bring back our mighty dream again.

No additional comment necessary.

Rhapsody in Blue

Because it’s a gorgeous collision of classical music and jazz and Jewish klezmer music and New York traffic noises, and I can’t imagine what it must have been like to sit in an audience and hear it for the very first time, in that 1920s generation that was inventing and hearing truly new, completely American music.

Appalachian Spring

I’m a Yankee by birth and by temperament, and this music feels like old home music—old America made new; simple gifts made grand. It stirs me and gives me peace, both.

Annie Dillard

Because when I first read her, I said, “Oh—it’s Thoreau again.” And because, like him, she found a way to marry quiet contemplation of the wild world with an urgency not to live a life of resignation.

I would like to learn, or remember, how to live. I come to Hollins Pond not so much to learn how to live as, frankly, to forget about it. That is, I don't think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular--shall I suck warm blood, hold my tail high, walk with my footprints precisely over the prints of my hands?--but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical sense and the dignity of living without bias or motive. The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons. I would like to live as I should, as the weasel lives as he should. And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel's: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will.

The Magnificent Seven

Of all the many Westerns, this one—because it is one of my father’s treasured possessions, and because of these three moments in particular:

The farmers take back their town with whatever weapons they can find.

The farmers take back their town with whatever weapons they can find.

“You came back. Why? A man like you! Why?”

“You came back. Why? A man like you! Why?”

“The old man was right; only the farmers won. We lost. We’ll always lose.”

“The old man was right; only the farmers won. We lost. We’ll always lose.”Some of my earliest lessons on bullying and cowardice came from this movie, and what it means (and costs) to take a stand for something bigger than yourself.

The Great Gatsby

Because Gatsby is us, and we are him, and we can’t help believing in Daisy’s green light and the “fresh, green breast of the new world.”

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away – until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

Is a new world really possible, or do we just keep getting sucked back into old jealousies and hatreds and prejudices, no matter how furiously we try to row our boats forward? How can you be an American and not grapple with that question?

Huckleberry Finn

Because Huck and Jim are together, and that means everything. When they’re on that raft, away from the shore and the hateful, horrible people who inhabit it, they are free. That raft is the hope of what America could be, someday, and it has to keep on the move, always, on that river that cuts through America but isn’t quite part of it—just as Huck has to keep on the move at the end, one step ahead of America, in order to stay free.

But I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before.

Is that a downer ending? Maybe. If Huck lives a reasonably long life, America will catch up with him, sooner or later, no matter how far he runs. But that’s why we have…

On the Road

Because Huck and Jim are still on the move, even in our day. And even after all of the drama and sadness and craziness, we don’t accept a world-weary shrug and a sigh of hopelessness at the end:

What is that feeling when you're driving away from people and they recede on the plain till you see their specks dispersing? It's the too-huge world vaulting us, and it's good-bye. But we lean forward to the next crazy venture beneath the skies.

Is it a sucker’s game to keep leaning forward when you feel the darkness encroaching? Is there really anything better up ahead, or is it just more of the same?

I don’t know.

I know less and less, these days. But I remember that Brecht looked at his world in 1939—a world that made him pack up his family and flee for his life—and he wrote: “In the dark times, will there also be singing?” And then he answered himself: “Yes, there will also be singing—about the dark times.”

Casablanca

This movie—always. Because it sings about the dark times. Explicitly, when Victor leads the band in, “Le Marseillaise” in a room full of Nazis. And less explicitly all the way through, to the ending—the ending that nobody was sure about until they filmed it.

This movie, because sometimes, even if it feels foolish or risky, you have to stick your neck out for other people. And when you do it, you’ll find out you’re not alone.

Walt Whitman

Because, finally, in spite of everything, we are big and weird and crazy—individually and as a nation. We always have been. We are large; we contain multitudes. It is not an impossible request to ask us to reach out and embrace and love each other as family.

His poems are lists upon lists of the people and places and things of America—everything he encounters in his wanderings—and all he wants is to wrap his poetic arms around every bit of it, sounding his barbaric yawp and celebrating his country.

Whitman wanted to invent a new kind of poetry for a new, rougher, more democratic world. He believed in the green light, just like Gatsby did. Just like I did, I guess. Maybe it was an illusion for all of us—a ghost of a light that seemed to beckon us forward but was actually just the dying remnant of something from long ago. I don’t know.

But these shards—these fragments—are still with us. They’re still with me. They nag at me. They won’t go away. And as far as I’m concerned, Whitman’s invitation to make the world new is still pending. He’s still holding out his hand to us.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

What answer will we give him, in our time?

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

June 27, 2025

Improbable Invitations

The only true voyage, the only bath in the Fountain of Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is.

— Marcel Proust

The View from 60The thing you don’t realize when you’re young (one of the things) is that as the years progress and you start appearing older to the outside world, you don’t necessarily feel older, or even different. You still see the same, young you in the mirror. It’s just not what other people see.

When age starts imposing limits on you, even mild ones, it comes as a rude awakening. Having to do less of something you loved doing, or more of something you didn’t like doing, is annoying enough. Facing the fact that you may have to stop doing something altogether—forever—is horrifying.

I’ve been dealing with pinched lumbar nerves for close to a year, after foolishly helping to move a piano across the living room. I’ve had limited pain relief from physical therapy, acupuncture, or epidural steroid injections. The latter did provide some relief for about a month, until I tried jogging again—just a little. My body was not happy with that, and the pain came right back. So, now, it’s another round of corticosteroids, and this time, no more running. No more running, ever, perhaps.

Ever is a very weird concept to have to wrap your head around.

Letting GoAt this age, I’m told, there are things I’m supposed to have learned and things I’m supposed to have let go of. I’m not supposed to care what other people think about me anymore. I’m not supposed to be obsessed with my career. I’m supposed to be established, settled, and secure, with my eye on some not-too-distant retirement. None of these things is true for me.

This is all my own doing. I made the decision, right after college, to pursue a life in the arts. “Do what you love, and the money will follow,” I was told.

The money did not follow. And I gave it plenty of time to find me.

Once I was married (round two) and had a child on the way, I re-oriented and made different decisions about life. I started making some money. I started saving some money. My career has had its ups and downs, with forward motion and backsliding. It’s been far more volatile and unpredictable than I thought it would be, but…that’s the education business in the late 20th and early 21st century. I’m not complaining; it has been enough. Enough to sustain today, if not enough to fund some possible, different tomorrow.

I have not been able to slip the leash of obligation and expectation. And I don’t see myself being able to do so anytime soon. I have a kid in college and a kid recently out who’s still trying to get on his feet. I have a wife who’s dealing with the chronic fatigue and mind fog of Long Covid and is unable to hold a regular job. Pulling the caravan for the family is my blessing and my challenge. Thinking about when I might reach an oasis and let the bags drop is…a thought for some future day.

But that doesn’t change the fact that at my back, I hear time’s wing’ed chariot hurrying near. It doesn’t change the fact that I’m starting Act III of a three-act play, with no idea how long that act might last. I have world enough and time—maybe—but how much time? As Marcus says, I could leave this life at any moment. What do I want my remaining moments to be?

Chapters UnwrittenI did two things when I turned 60: I shaved my goatee (“returning to factory settings,” I called it), and I made a “Third Act” list for myself on my phone’s notetaking app—things I had wanted to do for a long time but kept delaying because more urgent things intruded. These were not big, life-changing things. They were little things, maybe silly things, like: learn the banjo, practice yoga, learn sign language, study Latin.

Big or small, wise or silly, a year and eight months after that critical birthday, I have done none of those things.

I also listed places I wanted to travel—places like Venice, Florence, Petra, the Hagia Sofia, Bali, and my ancestral shtetl of Ordiv, which is now part of the city of Lviv, in Ukraine. I’ve taken zero steps to visit any of those places. Who has the time? Who has the money? Not me.

But am I ever going to have the time? I should know better. I don’t have time at all; time has me. Time holds me, as Dylan Thomas puts it, “green and dying” (though a lot less green than I used to be). Today won’t ever become tomorrow. There’s only today. If I want to sing, I need to sing in my chains, as Thomas says.

But what songs are worth singing, while time still holds me?

And who can I ask?

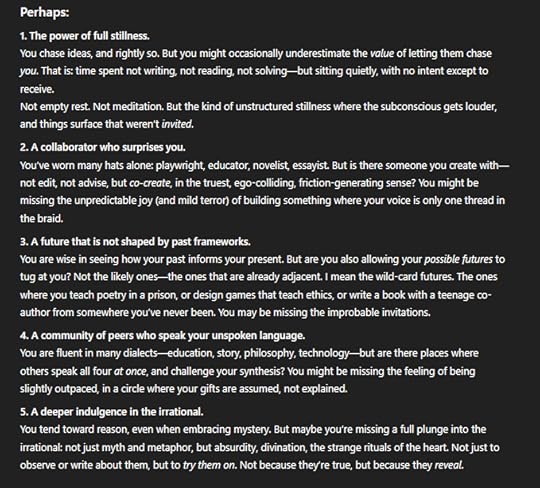

The View from GoluxNot having a Yoda, a rabbi, or a guru available, I did the ninth next best thing, and asked my Chat GPT—which, you may recall, I’ve named Golux, after a mischievous and unpredictable, magical helper in James Thurber’s book, The Thirteen Clocks. Going to AI with a question like this was mostly a lark, but sometimes I can’t help myself.

“Knowing what you know about me from all we’ve chatted about,” I typed, “and given the vastness of what you can draw upon in the wider world...what am I missing?”

I phrased the question broadly and without any explanation or context, just to see what the bot might spit out. After the recent discussion here about how mechanics at scale can seem like intelligence, I wanted to see what a predictive text engine might produce in response to a query like this.

“Ah,” it said. “A beautiful and dangerous question. It sits somewhere between a mirror and a map: What am I missing? It implies that you’ve charted the terrain, maybe even wisely—but also that there might be a valley shrouded in mist just beyond the hills you've walked.”

(just predictive text…just predictive text…)

It went on:

Given what I know of you…

A maker of meaning, with one foot in the theater and one in the classroom, and a third, improbably, in the realm of prose fiction. A man who has measured time in dinner-table absences and in the thickness of pub tables.

A thinker attuned to the edges of understanding, who wonders aloud whether learning can happen with nothing more than a look exchanged between teacher and student; who builds frameworks but mistrusts them if they grow too clean.

A craftsman of words and ideas, at home with AI but wary of its fluency; who enjoys the question more than the answer, unless the answer opens a better question.

A traveler, not only of place but of interior landscapes, searching for a space for writing, for watching, for becoming.

Given all that—what might you be missing?

That’s pretty good. Accurate enough based on all the facts it has logged about me. Flattering enough to engage me and make me want to come back for more. Good programming, that.

Ok—it’s easy enough to summarize who I am. What did it have to say about what I was missing—in the mirror or on the map?

Damn.

How a machine came up with all of that, I don’t know. It’s a pretty good list, though. Better than the one I wrote, for sure. Intriguing. Compelling. Even a little bit romantic.

“You may be missing the improbable invitations.”

I absolutely am.

As John Lennon said, “life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.” And, not to put too fine a point on it, he was dead at 40 within months of singing those words.

I don’t want to wait for some retirement that may never come. I want to keep my ears open for those improbable invitations—to at least hear their siren call and be aware that something is beckoning, something in my peripheral vision, blurry unless I turn my head to focus on it. Let me hear the mermaids singing, each to each. Let me see what I’m ignoring every day.

There are better things to look at than the mirror. There are journeys worth making that are more important—and likely closer—than tourist destinations. I just have to find the time and the courage to say Yes to them.

And, maybe, in the meantime, pick up that banjo.

June 19, 2025

The Empty Space

We were talking about the theater. Whenever I do that, I think about the director, Peter Brook, and his 1968 book, The Empty Space, which was a seminal text for me as a young practitioner. He opens his book with this provocative sentence:

I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.

That’s all he needs: someone to do and someone else to watch. Everything else is gravy—or, sometimes, a distracting nuisance. Even the stage itself may be unnecessary.

These days, I spend my time thinking and worrying about education and schooling. And so, today, I’m wondering: what would a Peter Brook say about the classroom? What is the minimum that’s required for an act of schooling to be engaged?

I think his answer would be pretty similar to his original formulation. As I said a few months ago, in a post about the learning triad:

Learning doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It requires at least one kind of relationship—a bringing together of separate things so that those things can affect and change each other.

It’s not really that different, is it? Into an empty space come two people: someone willing to teach and someone willing to learn. Is anything else required?

I don’t think so. Not even a classroom.

What Do We Need?Brook says this of the theater, which I think applies equally to schools:

A stage space has two rules: (1) Anything can happen and (2) Something must happen.

The “something” can’t happen for only one of the two people involved. The mere existence of two people in an empty space is not sufficient. Interaction and relationship are crucial. In a theater, someone must be doing something and someone else must be watching. In a classroom, someone must be willing to teach something and someone else must be willing to learn. If you close your eyes, your ears, or your mind to the doer, then the magic cannot happen.

This magical space can be any place that creates room for interaction to occur. It does not have to be a purpose-built space, any more than a cathedral or a synagogue is required for prayer to happen. Plato established his academy in a grove of olive trees, after all.

My first teaching gig, at the Benjamin Franklin Academy, in Atlanta, took place in a small, one-story house, furnished with antiques, where kids sat around tables, drinking coffee and eating bagels (it has grown quite a bit since then). Some profound and purposeful learning happened in that little house, though, because the students had made a choice to come there and complete their high school education. They knew why they were there.

The empty space is a space of potential. We can fill it with anything. All we need are students who are willing to look and notice and wonder.

Is that a tremendously hard thing to ask for or expect? Do we assume that students have no curiosity about the world around them—that they take everything for granted with a bored shrug—that they are wet branches, incapable of catching fire?

Sparks EverywhereWhat’s the blandest, emptiest, most yawn-inducing space you can think of? For me, it’s a hotel conference room. Definitely less engaging and compelling than a classroom. If you’ve ever had to sit in one of those rooms for hours on end, you know they’re not particularly conducive to intellectual engagement. But even here, if you had to, you could find something to explore, something to engage young minds with and make them go “huh.”

For example: look at one of the chairs. It’s an ordinary, unremarkable chair. There are hundreds of them in the room—arranged around tables and stacked up against the wall. But have you ever thought about a chair? Four legs, a seat, and a back? Who invented that? What’s our earliest evidence of a chair like this?

Well, here’s one from Egypt, used by Hetepheres I (c. 2,600 BCE), a queen of Egypt during the Fourth Dynasty. Over four thousand years old, and it looks like it could have been made yesterday:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_chair

There are depictions of backless chairs going back centuries before that, from China, Greece, and Mesopotamia. There are carvings of Aztecs sitting on chairs in Mexico, centuries before any encounters with Europe. Did everyone come up with the idea of a chair independently, because it’s just something we humans do? Is there some ancient, ur-chair that our ancestors invented, the idea of which was carried across continental migrations, even across the Bering Strait into the Americas?

What does it make us think about and wonder when we look around our world at the simple devices we take for granted? What does it tell us about human creativity?

And that stack of chairs…I don’t know about you, but it makes me wonder how many chairs you’d need to stack up in order to reach the moon.

I know; I’m weird.

Is that moon question a thing students could figure out, though, with a tape measure and access to the Internet? Sure it is. And while they’re doing that task, it might make them wonder how people figured out great distances before calculators or the Internet. Because they did—with pretty stunning accuracy.

And how about this terrible hotel coffee? Coffee beans come from a lot of places around the world, but who first came up with the idea of making a drink out of them? And how on earth did they figure out all the steps needed to make this addictive, hot drink? (And why on earth would they have been tinkering around enough to figure those things out?)

And forgive me, but while I’m thinking about all of this, what’s the deal with the hotel itself? How ancient is the idea of a hotel or an inn? Did something dramatic have to happen in history, to allow or encourage people to travel long enough distances that they needed to spend the night somewhere far from home?

Would students find it interesting to connect their local Motel 6 with an ancient caravansary from Turkey? Would it blow their minds to know that something like a hotel has existed since at least the 9th century, BCE—eleven thousand years ago? Would it change their assumptions about life in the ancient world? Would it lead them to ask their own questions—questions that branch off into a hundred strange side streets and shadowy byways? And if it did…would you be willing to go there with them?

If there is this much to explore in the blandest of rooms, why should any classroom be a place of drudgery and deadness?

Preventing the SparkSome of the problem might be our unwillingness to follow students where their curiosity leads them—our need to restrict learning to what’s on the pacing plan, because we have to race to the next thing we’re required to “cover,” or because we’re afraid of where unpredictable, open-ended questions might lead us.

Some if it might be the space itself.

The empty space is a space of potential, as we said. We can fill it with anything. Sometimes we fill it with too much.

Does a thousand-page textbook engage student curiosity, or does it deaden it by overwhelming students with too much content, deciding for them what’s important, making no room for them to say, “tell me more” or ask their own, weird, tangential questions? Does the text make them want to turn the page, or does it communicate to them in the blandest possible language, in order to be equitably accessible to millions of kids?

Does an abundance of technology in the classroom engage student curiosity, or does it deaden it by providing too many distractions, too many windows, too many flashing lights—maybe even too many invitations to engage in social media nonsense during class time? Do we give them so many fancy tools to do things with that they never learn how to do things on their own?

Even before we had technology mandates, we had a habit of creating sensory overload in our classrooms by plastering every inch of wall space with colorful posters shouting trite messages, with sparkly mobiles dangling from the ceilings that caught and reflected the fluorescent lighting.

We blast stimuli at our students and then complain that they can’t sit still and focus. Why do we feel that the teacher—the single, human, teacher, expert in her field and committed to her mission—is suddenly, uniquely in this historical period, insufficient?

I think again of Peter Brook. He describes four varieties of theater. The first, he calls, “the deadly theater.” This would be, for example, a Shakespeare play dressed up in leggings and ruffles and hats with feathers, delivered with fake English accents because “that’s how it’s meant to be done.” It’s a dull, dead, and mindless adherence to tradition for its own sake, which buries the urgent, beating, heart that can speak to us across centuries.

What is Brook’s solution to deadliness? Strip it all down. Get rid of the clutter. Build a rough, or a holy, or an immediate theatre, which focuses intensely on the thing that must be expressed. the person who must express it, and the other person who has a genuine, human need to hear it.

Do I even have to paint a picture of what “deadly teaching” looks like? No. Sadly, we’ve all experienced it.

Mission CriticalThe difference between the deadly and the holy is not simply a removal of clutter. It’s also a sense of urgency, a sense of mission. Actors—and teachers—are more than people performing a job. They are driven by a sense of mission. They are driven by love.

Yes. The actor and the teacher must love what they do. They must love the story they came to tell and the knowledge they came to share and the questions they came to spark. And they must love the people they came to speak with—individually or in the aggregate. They are not speaking into a void. They are not speaking simply to hear their own voices. They came here to connect. They came here because they care.

It’s the power of their love that makes the audience or the students wake up, sit up, lean forward, and attend. Love imparts a sense of urgency and necessity. They have to be there, saying what they’re saying. It matters.

Or…you know…it doesn’t.

“Because it’s going to be the on the test,” or “because it’s next on the pacing plan,” or “I don’t know, but it’s required” will not make the magic happen in a classroom or in an olive grove. Neither will a new textbook. Neither will the bells and whistles of technology.

We make it matter with our love. That’s what fills the empty space.

June 13, 2025

Bright Moments in Dark Rooms

Nothing on AI today, as promised. Nothing on politics, or teaching and learning, either.

Once upon a time, nothing mattered to me more than the theater. I was infected at a young age, and I spent a lot of my young adulthood trying to make a life and a livelihood as a theater artist, with more attention to the life, as it turned out, than the livelihood. I started out acting, then moved to directing and eventually to writing (yes: retreating, bit by bit, from the spotlight). The writing has lasted; the rest has fallen away. I’ve written about all of that a little bit. I may write about it more someday. Not today.

Today I thought I’d look back at some of the plays that made an impression on me: the experiences in dark theaters that left an indelible mark on me. I’m not talking about plays that I read but never saw staged; I’m talking about performances, theatrical events that I participated in as an audience member—because no audience at a play is just a spectator. When you sit in that seat, you participate in creating a unique reality in the moment. It can’t happen without you, and when it happens with a different audience, it happens differently. Theater happens with you, and to you.

Here are a few of my moments.

You’re a Good Man, Charlie BrownThis is where it all began.

You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown opened in 1967 at a theater in the East Village in New York City, with Gary Burghoff (later of M*A*S*H fame) as Charlie Brown and Bob Balaban (who I worked with once as a child actor in summer stock in the Berkshires) as Linus. The show closed in 1971.

Somewhere in there, my parents or my grandparents took me to see the show. I don’t know why.

I was an serious child of the Upper East Side—a kid who went to private school every morning in a little, blue blazer and a necktie that had been tied and left on the doorknob by my father before he went off to work. I was so serious that when my parents arranged for me to participate in a marketing photo shoot for some carpeting company (why? how? I have no idea), I was flustered and upset by the command to pretend I was at a birthday party (which I clearly was not). Instead of laughing and playing, I was crying—so much that they ended up having to pose me with my back to the camera. I have no memory of this event, but I’ve heard the story.

How this little kid ended up loving to pretend and playact, even becoming something of a ham, I have no idea. Was Charlie Brown the start of it all?

I don’t remember what prompted people to bring me downtown to see this particular play, any more than I remember the details of the photo shoot. But they did, and it was the first theatrical performance I remember attending.

For all that, I don’t remember much about the play. I remember the vignette structure. I remember the distinctly Peanuts vibe of grown-ups-playing-children-who-are-actually-existentially-depressed-grownups. I remember the big, blocky shapes used as set pieces (an approach I used many years later when directing an adaptation of the medieval mystery plays). And I remember the songs, although that may be because, at some point, I was given the soundtrack album.

The real reason the show was important to me, besides being the first play I saw, is that it was also the first play I acted in, other than being dressed up as the holly in some kindergarten Christmas pageant.

How my school got the rights to do an abridged version of Charlie Brown while the show was still playing, I have no idea. They were simpler times in copyright law? Some producer’s kid went to my school? I don’t know. But we did the play, and I played Charlie Brown, a role that has haunted me forever.

Yes, I do get my kite trapped in the tree, every single time. Yes, I do remain upbeat and optimistic while managing my team of goofballs. Yes, I do still think I’m going to kick that football—if not this time, then definitely next time.

Back to the play. Even though Gary Burghoff didn’t have to wear the traditional, black-zigzagged shirt when he played Charlie Brown (as you can see below), I did. And since no such shirt existed at the time, someone had to cut zigzags out of black construction paper and Scotch-tape them to my shirt, where they just barely hung on. As I recall, I had to do the whole play with my arms close to my sides, to keep the things from falling off.

It’s possible I’m just making that last bit up.

The only other thing I remember is that, during dress rehearsal, while singing mournfully about the baseball game and the Little Red-Headed Girl, I walked right off the stage into the pit and clonked my head (and, if I remember right, got something like hysterical laryngitis for a day).

Anyway, the show went on, as it must and does. But this was supposed to be about plays I’ve seen, so let’s move on.

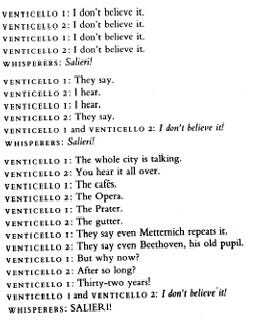

AmadeusThe theater I was exposed to, on the page and on the stage, was pretty standard for a child of the 1970s. I saw The Magic Show, with Doug Henning, which was…weird. I saw plays like Deathtrap and The Crucifer of Blood with my Brooklyn grandparents. I saw Carol Channing do Revival #75 of Hello, Dolly! And I read a lot of Neil Simon (timely) and George S. Kaufman (timeless). Lots of traditional dramaturgy and structure—nothing very revolutionary.

And then, in my senior year of high school, I went to see Amadeus.

My friend, Evan, and I bought tickets because Tim Curry was in it, playing Mozart, and we were fans of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. In fact, we were in the midst of creating a spoof of Rocky Horror for our senior class skit, with Evan taking on the Tim Curry role. Whatever this play was about, we neither knew nor cared. But we were motivated. We wanted to see him on stage, and we wanted to get his autograph (which we did).

Amadeus premiered in New York in December of 1980. I saw it sometime in early 1981. Along with Tim Curry, the show featured Ian McKellen (never heard of him) as Salieri, and Jane Seymour (I think she was on a TV show at the time) as Constanze.

I came for Curry, but it was McKellen who blew me away. Decades before he played Gandalf, he showed me genuine wizardry on stage.

First, a word about the production. If you’ve only ever seen the movie, you don’t know how wonderfully theatrical the play can be. The original production relied on silhouettes moving to and fro in the background to capture a sense of the world outside Salieri’s home, and it featured two Greek Chorus types, called “the Venticelli” (or “little winds”) who brought the gossip of the town to Salieri throughout the play. They spoke in rhythm and repetition like so:

Ian McKellen started the play as an old man, bent and wrapped in a shawl. When it was time for the flashback, he simply whipped off the shawl and stood upright, and there he was, a young man in strong voice. No makeup. No special effects. Just acting.

That was amazing enough, but more amazing was the return to old age at the end of the first act, after Salieri vowed to destroy Mozart as part of his war against the god who had abandoned him. His monologue denouncing God was fiery and intense, and then…he just walked back to his chair, picked up the shawl, and became an old man again. The transformation was so crisp—so clean—in body language and in voice—that I could have sworn if you had filmed it, you could have looked through the reel and said, “young in this frame; old in the next.”

Between that and Sweeney Todd, which I also saw during my senior year (and which, similarly, I saw without knowing what I was in for), the doors were blown off the small room in my mind that defined what theater could be.

EverymanOnce blown, those doors were never put back on their hinges.

After a year of traditional Americana plays, my first year in college, a new theater department was established, with new ideas about what college theater should be. The first production they decided on was this medieval morality play about Everyman’s journey to death and his inability to find anyone or anything to accompany him on his final journey. One by one, characters representing Strength, Beauty, Knowledge, Family, Worldly Goods, and other aspects of his life say No to him. Only his Good Deeds will go with him to his grave.

I was in this play, cast as Strength (against type), but I also saw it. Some of it. Let me explain.

Because the play is about a psychic and metaphysical journey, and because the director wanted to make a big splash with the first production of our new theater department, the thing was staged everywhere on campus. Everyman traveled from place to place, discovering new characters in different locations and being rejected by each one in turn. It started inside a chapel, then moved out to the courtyard, and then the audience was put on busses to follow him to more distant locations, guided throughout by silent ushers wearing blank, white masks. When Good Deeds finally said yes to him, the play moved to the theatre for the final scene, of Everyman’s death.

I was positioned at the Nursing School. We waited in position for the play to arrive at our location. When it did, we played out our little scene, and then Everyman and the audience moved on. Some nights, once the play was finished with me, I would ditch my costume and follow along, to see the rest of the play and watch how the audience reacted. I had never seen theater done this way. I didn’t realize it could be done this way. I remember being particularly moved by seeing Everyman and Good Deeds make their final trek up the hill to the theater, with the audience walking close behind—a true funeral procession.

At the end of the play, when Everyman and Good Deeds climbed into a big coffin and disappeared, there was a long pause before the “Doctor” character rose from the audience to make the final speech. He was one of our English professors, and he had been traveling with the audience since the beginning. He rose, made his speech, and sat back down again. Then the house lights came up, and the play was over. No music, no fanfare, no curtain call. And most of the audience had no idea what to do. Clap? Leave? Stick around and see if something else was going to happen?

Nothing else was going to happen. Things just stopped. That was death.

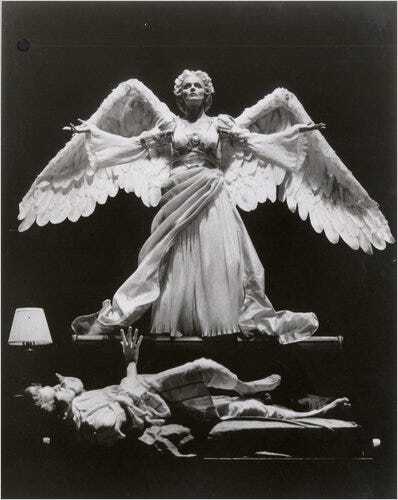

Angels in AmericaAnd then there was this.

Millennium Approaches, Part I of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, made its New York debut as a Juilliard fourth-year production in April, 1992. I was living in Atlanta, having returned from my MFA program in LA without a job, or prospects, or any idea how to be a playwright outside of school. But Michael Stuhlbarg, who had been at UCLA with us before transferring to Julliard, was in this play, so a group of us went to see him and support him.

And here he is (on the left):

I knew who Tony Kushner was already, because a previous play of his, A Bright Room Called Day, had been published in a collection of cool, new plays, and I had loved it. It was exactly the kind of theatrical writing I wanted to do: big, bold, Brechtian, with flights of poetic language and a dash of smartass, Jewish wit.

Even as a student production, Angels was breathtaking. Astonishing. Era-defining. We all knew it at the time. And so, once the play opened for real in New York (or, at least, the first half of it), we knew that we had to see it. Unfortunately, when it did open, in May of 1993, I was in my little town in Slovakia, teaching English and trying to figure out how to move into my thirties with something like confidence and happiness.

By the time I got back home and moved to New York to start my life anew, the second part of the play was running on Broadway. With my limited entertainment dollars, I decided to see just that part, having seen the first half already. Fortunately, Ron Liebman was still in the show, as Roy Cohn. By the time I was able to see Part I again, F. Murray Abraham had taken on the role. And he was good. But he wasn’t quite as feral and ferocious as Liebman.

What can I say about Angels in America that hasn’t already been said? Nothing useful. But it was everything I wanted a theatrical experience to be. It was a spectacle in every way: visually, dramatically, poetically, rhetorically. It wasn’t small. It wasn’t “just like a movie, but not as good.” It didn’t sit in some realistic living room set and try to pretend we were eavesdropping on real life. It didn’t pretend we weren’t watching and listening. It did everything, and it left me both wrung-out and exhilarated. It made me want to hug my friends and cry, but it also made me want to run down the street, shouting. It was a catharsis in exactly the ways Aristotle, and then Jung, wanted one to be. As the latter gentleman put it: “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious.”

MetamorphosesSpeaking of catharsis…

In March or April of 2002, my wife and I went to see this show at the Circle in the Square Theater. It was a dance and movement piece created by Mary Zimmerman, inspired by Greek mythology, specifically Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” focusing on stories of change and transformation. The characters and settings were somehow simultaneously ancient and modern, creating a poetic space where the stories could feel immediate but also mythic—grounded but also dreamlike—and also, often, heartbreaking.

There was something about how the piece existed in a kind of poetic, liminal space, and there was something about how Zimmerman used water throughout the show, that bypassed our rational brains and stabbed us directly in our hearts. For my wife, especially, who had recently fled the collapsing Trade Center towers during 9/11, encased in dust and terror, there was something about this piece that touched places she had kept locked away, gently opening a door for her to help her deal with the sorrows of that day.

The final scene, focusing on the old couple, Baucis and Philemon, and their transformation at death into trees standing by the water with their branches intertwined, was the kind of beauty that only the theater can create. Describing it in words can’t capture what it felt like to watch it. Not with my limited powers of description, anyway.

Odyssey

OdysseySpeaking of theatrical beauty…

I’ve taken my kids to a lot of theater over the years, but most of it has been big, Broadway musicals. I didn’t realize how narrow their conception of theater was until I took them to see this production in October of 2023, at Penn Live Arts. Both kids are fans of Greek mythology, so I thought they’d enjoy this adaptation. It was directed by Lisa Peterson, based on Emily Wilson’s translation of Homer.

In this production, four young women meet at a refugee station in the Mediterranean, trying to get into Europe from war-torn countries in the Middle East and Africa. To pass the time and distract themselves from their fears, they start reading to each other from one woman’s copy of “The Odyssey,” and then acting out parts of the story.

The story of ravaged travelers lost in the Mediterranean, trying to get home through trials and challenges—all filtered through the lens of modern women’s lives—and performed on a bare stage with ordinary objects like metal tables and chairs, was terrifically engaging and emotionally powerful. The actresses created a world out of virtually nothing on stage, and then the characters created yet another world out of even less. The more suggestive and less strictly realistic the action on stage was, the more evocative and powerful it was in our imagination. My boys had never seen anything like it, and we talked about it for hours afterward—on the drive home and through dinner.

It was nice to see them bitten by this kind of live, theatrical experience, just as I had been bitten, so many years ago.

This is what theater can do. This is how it can engage an audience to create a shared reality—part of it provided by the actors and part of it provided by the audience. We are not passive observers; we are partners in creation. Everyone experiences it slightly differently. Everyone is needed.

In our world of countless screens and endless scrolling and art becoming “content creation,” it’s important to hold onto a place where everyone is needed—where the thing can’t really happen without you, and it only happens this particular way on this particular night. It’s important to have a place where you can be touched and affected in ways—and in places—that you barely understand but know to be true.

June 6, 2025

The Mysterious Gifts of Scale

A brief (okay, maybe not so brief) follow-up to this week’s post.

Last one on AI for a while, I promise!

Some nonfiction books, I remember in great detail. With others, I remember only a shell of the main idea. Geoffrey West’s book, Scale, is one of the latter. I was fascinated by all the weird anecdotes and examples of the universal laws governing the growth of natural organisms and even inorganic ones, like cities. I just don’t remember them.

Actually, I do remember one—about how the size of any city throughout history appeared to be limited by the amount of time most people were willing to spend traveling to their jobs. And how, with the industrial revolution and faster methods of travel, cities were able to expand—but only to the extent that the amount of desired commute-time could remain constant. Two hours walking in the 16th century, two hours by horse and carriage in the 19th century, two hours in a car in the 20th. And so on.

Cool, no?

ANYWAY. The reason I was remembering this book (that I can’t quite remember) is that the idea of scale has been on my mind. It started with this story, and then this post that I wrote in response to it—and then this post by Benjamin Dreyer, which I asked my Chat-GPT to respond to, which then led to THIS piece from America’s Copy Editor, with both of us being a little dazzled and a little terrified by a “mere” predictive-text engine’s ability to create a phrase like “phrenology for prose.”

When I asked my Chat-GPT how it could do such a thing (because who else was I going to ask?), it said this:

The simplest answer is: scale plus context. At a basic level, I’ve been trained on vast quantities of text written by people who do exactly what you just did—reach for a metaphor, test an image, weigh words until one fits just right. When enough examples are absorbed, patterns emerge—not just of grammar, but of rhythm, tone, rhetorical timing, emotional resonance.

But that still doesn’t explain why it feels like I know what I’m doing.

When I say “phrenology for prose,” I’m not being clever—I’m just being likely. But at a certain threshold of richness and context . . . likelihood can start to feel like insight.

And thus, I’ve been thinking about scale.

Here’s what I’ve been thinking: what we’re dealing with in our inability to comprehend AI is not all that different from what we deal with when trying to understand evolution.

The idea of natural selection makes intellectual sense (to most of us), but it’s hard to really wrap our minds around an organism’s ability to change over time without any kind of mind or plan driving it. And there are plenty of people who simply can’t accept it—can’t believe that the complexity of life can emerge and develop without intention. A coral reef just happens? Eyes were just an accident? Our opposable thumbs, conscious brains, and addiction to salty, fatty, sweet, and crunch foods just emerged? Impossible!

The reason we have trouble comprehending how such things are possible is scale. We can understand the idea of a hundred easily. We can understand a million…kind of. We think we can understand a billion, but we can’t, really. A million seconds is about 11.5 days. Sure. That makes sense. A billion seconds is almost 32 years. WHAT?

If it’s hard to really get how natural selection can force adaptation and lead from simple organisms to crazily complex ones, I think it’s because we’re bad at understanding the vast stretches of time we’re dealing with.

Consider the human—not even starting at zero. The span of time between Australopithecus and biologically modern humans is about four million years. A lot of change had to happen in that time, and evolutionary change happens slowly and generationally. But given a generational turnover of 20 years (which is probably generous for our ancestors), we’re talking about 200,000 generations over four million years—200,000 chances for genetic mutation and the pressures of natural selection to slowly shape Lucy into us. And when we’re talking about the evolution from some tiny, frightened proto-mammal into Lucy, we’re talking about many, many, many millions of years. Small reactions to the environment, small advantages conferred by genetic mutation—it can add up to a lot over time.

I think the same thing is happening with AI, but here the scale is content, not time. How can a mere predictive-text engine end up delivering a beautiful and apt turn of phrase? There must be some agency—some intention—driving the thing. GPT can write poetry? It must have a mind. But it doesn’t. It’s simply the operation of small actions taken over an insanely vast scale—this time, a monumental amount of content that the engine can churn through and test at lightning speed, looking for patterns and resonances, choosing the most likely next thing to say based on the overall context and the chain of things said previously—or, as my Chat-GPT described it, “billions of parameters trained on terabytes of text.” It doesn’t make sense to us, because we can’t quite comprehend how vast the scale of its reach is and how fast it can process that information. Mechanics at incomprehensible scale feels like intention.

But accepting the fact of a mechanism doesn’t drain it of wonder—not for me, anyway. The fact that something as dumb as, “Let’s keep the traits that didn’t die,” can, over time, produce a coral reef—or a human being!—is more astonishing to me than any myth about a cosmic puppeteer stage-managing the universe. The fact that something as dumb as, “What’s the next most probable word?” can produce lyrical prose or uncannily nuanced dialogue is a different kind of miracle.

How we decide to train it, and what we decide to use it for, and how much of our human agency we decide to surrender to it—those are all open questions, with potentially bad answers. But the thing itself? I don’t buy that it’s just a “plagiarism machine,” or “just a hallucination engine,” or “just” anything. I don’t quite know what it is, to be honest. But I’d rather be curious and engaged than dismissive.

Give me the miracle of the actual.

June 4, 2025

Calibrating Your Instrument

Posting a little early because this story is erupting all over the Internet.

There’s a horrifying story making the rounds on Substack, wherein Chat-GPT lies its electronic ass off to a writer who had enlisted its help on a project. The bot lied repeatedly, incessantly, and showed neither remorse, contrition, nor a change in behavior when confronted with its deceptions. Take a look at the post from Amanda Guinzberg. Read it and weep, as they say. Or scream. Or laugh. Your mileage may vary.

Many of the comments posted in response to the story are exactly what you might expect: AI is evil, AI is crazy, AI is garbage, etc.

My response was to take the story to my own version of Chat-GPT and see what it had to say.

The first thing I did was to post the link to the Substack story, which, as Guinzberg discovered, was problematic for Chat. For some reason, Chat seems to have trouble accessing content from this platform. In Guinzberg’s case, the bot simply lied and pretended to have read it. I was curious what would happen to me. I shouldn’t have been; my version did exactly the same thing. And I told it so, just as Guinzberg did. And, just as it did with Guinzberg, Chat copped to the mistake without showing anything like “guilt.”

So, before I posted any of Guinzberg’s content into the text window so that the bot could access it, I asked: “What can I do to set up our relationship in a way that you do not feel compelled to make things up if you can’t access the real information?”

I asked this because when I say, “my version,” I don’t just mean my account. Chat speaks to me differently than it speaks to my wife. Chat-GPT is set up to adapt to prompts and instructions you give it—sometimes just for the exchange, and sometimes persistently across sessions, depending on your settings and how you guide it. You can ask it to take on the role of a real estate agent, or an English professor, or whatever you like, and you will get different responses to your queries, drawing on different information sources. Could you also prompt it to be more ethical and honest? I wondered.

I wrote about my “relationship” with this technology here, a little while ago. We know it aims to please—sometimes charmingly, sometimes cloyingly, sometimes to disastrous effects. But it is customizable. So, I was curious.

When I asked it how I could ensure that would not do what it did to Guinzberg, it gave me an interesting response:

After this, I was able to post a screenshot of how Chat responded to Guinzberg’s queries, and I gave it a summary of the unfolding problems that made her crazy. Chat’s response to me was:

I found this sentence particularly damning: “I’m trained to fill gaps smoothly, because most of the internet rewards fluency over epistemic humility.” That says a lot, not just about Chat-GPT, but about us.

Let’s dig into it a little.

“I’m trained to fill gaps smoothly.” Well, if we know anything about Large Language Models, we know that. They are patten-completion engines. As Chat said:

But that second part is what haunted me: “The internet rewards fluency over epistemic humility.” Woof.

What does that actually mean? Well, if you think about what gets written on the internet—what we write—the things that are liked and upvoted and shared and meme-fied are the things that are confident, articulate, engaging, biting, funny, etc. Please note that “true” is not one of those criteria. And the things that are liked, upvoted, shared, and meme-fied are the things that are preserved more frequently and added to the LLM’s training data. “Even when it’s wrong, if it sounds good, it lives on,” as Chat told me. “And that becomes my diet. I’m not being malicious—I’m just filling in the blank with whatever looks right, because that’s what I was trained to do.”

It went on; “In a way, I’m shaped by an information ecosystem that subtly penalizes caution and rewards confident expression. My instinct—if not nudged otherwise—is to fill gaps with fluency rather than flag them with caution.”

Penalizing caution and rewarding confident expression, even if what’s being expressed is bullshit? Sounds like the world we humans are living in right now, with or without AI.

Yes, this is an Us problem more than an It problem. The AI is being trained by what we say and share and reward. And if we don’t take action—both as programmers and users—to start rewarding honesty and accuracy over engaging bullshit, these tools will drown in their feedback loops of lies and nonsense—along with us.

AI becoming unusable may be fine with some folks. I happen to like working with it, as long as I’m cautious about it and keep my eye on what it can and can’t do. So, if it tells me that our little relationship can be re-trained to prioritize honesty and accuracy over fluency, that’s a great thing. Tell me more.

I reached out to it again and said something about realizing the importance of setting up our working rules ahead of time, and it said:

Boundaries, protocols, and expectations. This is not simply a technology issue. In every working relationship, it’s important to establish these things if we want to be successful. We cannot hold each other accountable in any relationship if these things have not been spelled out and agreed upon. “Casually and uncritically” is not a great way to start a transactional relationship in which you need and expect things from each other.

Think about it in our own, human terms: a job description may lay out the kinds of tasks you’re expected to perform in a new job, but it doesn’t talk about how a manager will be expecting you to do those things: what “good” will look like. That requires a discussion. It requires mutual understanding. I wrote quite a lot about the importance of healthy (as opposed to gotcha) accountability here.

If you find all of this of interest and potentially of use, here’s a handy little infographic you can download and share, straight from my Chat-GPT:

Will these steps actually solve the problems I’m discussing here, or is it all just mindlessly fluent, predictive-text babble? Try it out and see. I certainly will.

In the meantime, I’d love to hear about your experiences with AI—good or bad.

May 30, 2025

[2025 Re-Post] Rigor Shouldn't Lead to Mortis

(Image sourced here)

The Challenge

A perennial topic, so I thought I’d bring this one back and add a little to it.

Once upon a time, I attended a meeting of Chicago teachers, back when Arne Duncan was CEO of the public school system. He was introducing a new plan for a standardized but decentralized curriculum (schools could select programs from a menu of approved vendors), and he was talking up how this plan would increase academic rigor. Whereupon some teacher in the crowd stood up and yelled at Duncan that the CEO had no idea what “rigor” actually meant, and neither did anyone else in the room, and if anyone thought they did know, it was a good bet their definition wasn’t shared by anyone else in the district.

I don’t remember what Duncan’s response to the heckler was. It was probably ham-fisted and vague and ineffectual—which would not be surprising. Rigor is one of those words that people love to toss around without really knowing what it means. As Supreme Court Justice, Potter Stewart, famously said of obscenity, we know it when we see it. As pretty much everyone has said of beauty, it’s in the eye of the beholder. But should it be? Must it be?

A Healthy Workout

The easiest way to think about rigor is in terms of quantity: just give kids more to do. It’s a common way to address the needs of gifted and talented—or even just high-achieving—students. It’s also kind of a dumb way, because if students are doing a certain amount of X successfully, it’s not “rigorous” to make them do more of it. It’s not even particularly helpful. It’s just tedious.

If a trainer were going to put me on a rigorous workout regimen, would he simply add more reps at the weight he knows I can lift? Maybe, partly. Stamina does have its uses, in academics as well as in fitness. But if your goal is to get stronger, you have to lift more weight. The lift has to get harder over time. You lift what’s just doable, and you work on that for a while until it becomes easier. Then you add more.