Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 8

May 31, 2024

Feudal America

The Atlantic Magazine recently devoted an entire issue to warnings about what a second Donald Trump administration would look like. I admired their focus and determination, but I worried (and still do) that it’s going to amount to yelling into the wind. They’ve published multiple warnings, but the people whose minds need to be changed don’t seem to be reading The Atlantic.

They had a depressing little article way back in 2017, too, about how the idea of America—the set of beliefs that animated people like Whitman, Emerson, and Thoreau—appeared to be disappearing with each passing generation, leaving only a dry husk of nationalism, racism, and xenophobia in its place. It inspired me to write much of what follows below, which felt relevant enough for me to resurrect from my old Blogger site and revise. And now, after watching Donald Trump’s conviction as a felon—and how horrid and inappropriate our Landed Gentry feel it is—I’m inspired to publish it again.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

What the 2017 article was describing was not simply a matter of history replacing Old Dead White Men with something more modern and alive and progressive. In some ways, putting those people behind us may be regressive. Thomas Jefferson may have been a racist and a misogynist and even, perhaps, a rapist. But in the realm of politics, he was a revolutionary, and he helped lead a revolution in thinking. His generation had its faults, for sure, but they tried valiantly to break away from old ways of doing things in the old world and build something new here. Often they were hobbled by their own limitations and blind spots. Sometimes they succeeded.

When they did succeed, they tended to piss off a lot of people—and if they were among us today, they would piss off just as many. Early on, Jefferson tried to break the whole idea of protocol and grandeur by seating foreign diplomats at a round table and serving ordinary food. The dignitaries were furious. If someone were to do that today, we’d call them a Communist. Our leaders certainly don’t do that anymore. They know we love the pomp and pageantry. We love the grandeur of royalty and celebrities and glamor. Maybe we love it too much.

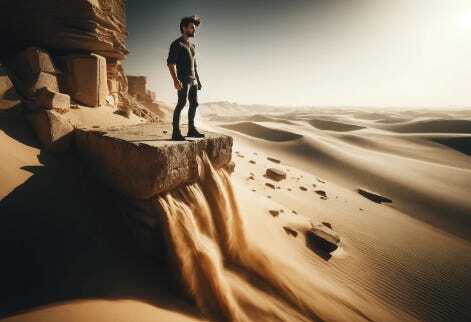

F. Scott Fitzgerald saw it coming as early as the 1920s, when he wrote, towards the end of The Great Gatsby:

And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away – until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

According to that Atlantic article from 2017, on a scale of 1-10, less than a third of Americans born since 1980 assigned a 10 to the value of living in a democracy (as opposed to 3/4 of those born before WWII). A quarter of Millennials said it was not important to choose leaders in free elections, and a little less than a third thought civil rights were needed to protect civil liberties. The article didn’t talk about what or who those people thought would protect their liberties, absent a code of civil rights. Perhaps they thought Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk would have their backs. Maybe they thought Donald Trump would.

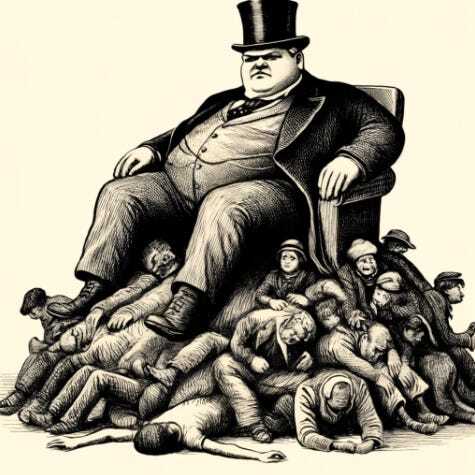

There was a time—just yesterday, really—when the average person’s safety depended on his allegiance to a local lord of some kind. The lord was part of the ruling class—the strong and wealthy and well-connected. They weren’t regular people, and regular people could not ascend or aspire to their level. In some places, rulers were considered gods; in others, they simply received their right to rule from God. Either way, they owned the wealth of the country, and they owned the land of the country, and those things were carefully managed and preserved and handed down from generation to generation.

This is important to understand: the ruling class didn’t just have a lot of money; they actually owned the country. A local warlord or strongman would be given a garrison and some parcel of land by the ruler, and his job was to hold it against invaders and other evil-doers. The regular people who happened to live on those lands were under the protection of that lord, and paid for that protection with…whatever was asked of them (just as the lord owed his life to his ruler). Perhaps the lord wanted a percentage of your crops. Perhaps the lord wanted you to serve as a soldier in his little army. Perhaps the lord wanted your daughter. All fair game. He didn’t just write the laws; he was the law. If you didn’t like the way he ran things, or the level of protection you and your family were afforded, or the price you had to pay to stay within his realm…too bad. In some lands and times, he actually, outright owned you. In others, he simply had such overwhelming power over you that he might as well have owned you.

That is the way things were, with minor variations, for most of us and for most of recorded history (what the world looked like before then may have been very different, according to the authors of The Dawn of Everything). The strong and the wealthy owned and ruled, and the rest of us served their interests, their needs, and their appetites. The rulers took care of the poor to whatever extent they felt it was affordable and manageable. After all, they needed farmers and soldiers. There was work to be done…and they, the lords, were the ultimate owners of that work, regardless of who did it for them. The rich assumed that the fact of their wealth was an indication of their moral and spiritual worth, and the poor were taught that their poverty was a sign that there was something wrong with them, something that their lords suffered with patience and magnanimity, as God himself did.

What worries me—what the news seems to be telling me—is that this dynamic is baked deep into our bones. Something in us yearns for the strongman, for the big daddy, for the god who rewards and punishes, who seeks vengeance against those who have wronged him. Something in us hungers for absolutes, for a world of black and white in which our group, our tribe, our people, live unquestionably within the “white.” Don’t let two hundred years of self-government inspired by the Enlightenment fool you. Two hundred years is nothing and the Enlightenment is constantly under threat, even in our schools.

If you look across human history, the idea of broadly applicable civil rights is not the norm—not by a long shot (and not even in our own country for most of its history). Rule of law is not the norm. Representative democracy is definitely not the norm. Even a merchant/entrepreneurial class standing between the peasantry and the aristocracy is not the norm. If we assume that these things just happen, and will always be there for us, then we’re fools. The founders of our country and their more progressive descendants fought hard to bring these things into existence.

As the authors of the recent book, The Narrow Corridor, make clear, the conditions for having a country like ours are very particular, and are historically rare. Our “new world” requires a certain amount of central government power to get things done and a certain amount of public pressure and constraint to hold that power in check. It doesn’t happen everywhere, or often.

My fear is that, if we don’t understand and value that narrow corridor, the old ways of doing things will return. We saw it creep in during the Gilded Age, only to get pushed back by a couple of Presidents Roosevelt. And again, today, it’s returning.

The strong and the wealthy want to rule; they expect to rule; they are surprised and annoyed whenever constraints are put on them; and they fight, constantly, to remove those restraints and run free. They feel it is their right (or perhaps their moral burden), as exceptional people. They work very hard to make us think that it is in our best interests, too, to let them do as they please—not only to rule the land, but also to run roughshod over it however they please, without limit or restraint.

It seems to me that American politics at its core is not really about liberal or conservative cultural issues: it’s really a fight between those who want to constrain wealth and power enough to allow every citizen the freedom and means to pursue happiness, and those who feel the wealthy and powerful are entitled to whatever they can take. Some people call that “class warfare,” like it’s a bad thing. But maybe it’s not a bad thing. Maybe it’s the real thing.

We value the freedom to do as we please, but we also value equity and fairness. Two great ideas that fit together like oil and water. American politics is not a stable, comfy thing; it's a state of eternal dynamic tension. It was built that way on purpose.

If we value personal freedom but also societal equity, we have to find ways to balance them. And “ways” means laws. Those with wealth and power are always well positioned to acquire more of both; those with neither are eternally at a disadvantage. Where we can’t do for ourselves, the force of law has to do for us. That’s what laws are for.

We were not promised happiness, but we were promised the ability to pursue happiness, and the laws of the land exist, to some extent, to allow each citizen a reasonable shot at that pursuit. The fair and equitable pursuit of happiness, regardless of birth circumstances, has never existed without structures put in place and held in place for that purpose. Without those laws, all you can do is ask pretty please for the wealthy and powerful to help you out. And they will, gladly….for a price. The historical norm, into which we could easily slide if we’re not careful, is some form of feudalism, where a tiny fraction of the population own everything…and everybody.

Donald Trump is not really a Republican or a Democrat; he’s a feudal lord dressed in a bad suit, confused about why all the little people are getting in his way. His every action, from the way he decorates his homes and addresses his adoring crowds to the way he takes what he wants when he wants it, speaks to this self-image. His plans for a second administration make it clear.

He does not exist to serve us; we exist to serve him. The only reason for our existence is to exalt him. The giant flags with his name on it make it clear that many of his supporters are happy with this state of affairs. As far as he is concerned, the country is his for the taking—his and his family’s. He has lived this way, unapologetically, for nearly 80 years. How he managed to bamboozle anyone into believing he cared about the “common man” as anything but the raw ingredients for his next meal amazes me, but there it is.

Am I just a liberal alarmist suffering from Trump Derangement Syndrome? Maybe I am. But if we did slide into something like an American feudalism, what would it look like?

I think it would start with some simple beliefs that already rattle around our culture—things like basic health care not being a right; the government not owing you anything; all taxation being theft; the government needing to be small enough to drown in the bathtub; the desire to be left alone, to do what we will; unfettered individualism.

Those sound very American, very cowboy-like, very freeing. And they can be freeing and desirable…as long as you have cash. You're only free if you can afford to be free.

You can already see a creeping sort of feudalism in the way we think about health care. If you're wealthy, health care is a commodity you can buy. For everyone else, it has become a gift (a "benefit") to be bestowed upon you by your employer, because it's simply too expensive for most of us to afford on our own. And you’d better behave yourself if you want to hold onto that benefit. If you don’t like that, you can go with the rest of the bungled and the botched to the emergency room and throw yourself on their mercy. Of course, if taxation is theft, and everyone has to pay their way individually, 100%, you may not have that merciful option open to you for very long. But…too bad for you. That’s life. You are owed nothing; you are promised nothing; you should have worked harder.

Roads? Schools? Protection from fire? Protection from thieves? The rich and the powerful are happy to pay for those things…for themselves. But what happens if we really buy into the idea that taxation is theft--that the Haves owe nothing to their neighbors? Those who have will retreat to their gated compounds, where the roads are well tended. They will provision their estates wonderfully. And they will protect what they have ruthlessly. After all, there are so few of the blessed inside, and so many of the cursed outside. There is no social contract; there is only you, and you, and you.

Of course, a wide range of services will always be needed within these compounds. Someone will have to sweep the streets. Someone will need to teach the children. And so on. There will be jobs to be bestowed. And one assumes there will be some level of charitable giving, as well. The wealthy aren't monsters. If giving isn't mandated by law, it will be compelled by religion or ethics or whatever.

So...the gates will open, and the serving class will be allowed in, one by one—pledging their allegiance and their service to the lord and accepting his protection in return. Of course we’ll pledge our allegiance. What other choice will we have? If we destroy the idea of a government that we select and fund, whose functions and functionaries are beholden to voters, what will we have left but a ruling class that gets to make all the decisions by itself, for itself? And for us, too, when it occurs to them. Your lord might be an actual person, or it might be a corporation, but either way, the lord will hold power and the lord will grant privileges. “Rights” will be what you earn through your loyalty and hard work. Again, Trump has made it quite clear that he views things exactly that way.

When we look around the world today, we see a lot of representative democracies, and we think, “Well, that’s just how good, sane people do things, here in the 21st century.” But this century is just a dot on a very long timeline, and our nation’s whole history is just a tiny stretch of time between dots. Electing leaders and holding them accountable to our needs and desires is nothing like the norm, historically. Assuming our leaders should be held accountable to the same set of laws as all other citizens is equally unusual. If we think it’s a valuable thing, we’d better start valuing it.

We should not assume that what we have is safe, stable, or normal. It needs constant protection. If we care about it, we have to make sure we actually understand how it works, so that we can protect it. We have to teach it to our children and make sure they treasure it. We have to be zealots about it. As unfashionable and un-ironic and un-detached as it may sound, we have to be patriots.

May 24, 2024

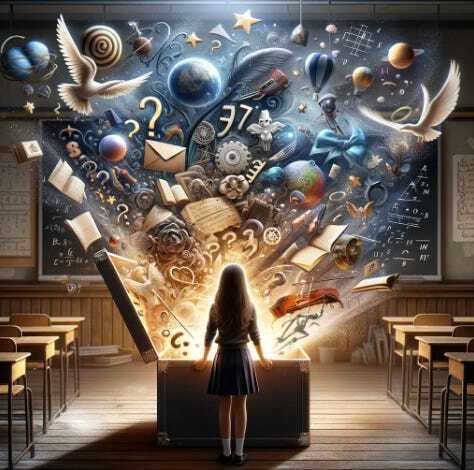

Cultivating Student Curiosity

Once upon a time, I performed a magic trick at a teacher workshop. I was working with a set of elementary-school teachers in Indianapolis: two workshops per day, over two days. With each of the four groups, I asked the teachers to show me what they thought their students would draw if they were asked to picture a house, with a family and tree out front and the sun up in the sky. When they were finished, I said, “Now here’s my magic trick. I haven’t been anywhere near my computer while you’ve been drawing, but now I will reveal the picture that every one of you drew.” And I put this picture up on the screen:

Sure enough, it was exactly what every one of them had drawn. They laughed. But they were right—it probably was what all of their students would have drawn.

Why?

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Un-boxing the Student BrainThink about it for a moment. Every house a square with a triangle on top? Why? Is that really an approximation of what the kids’ houses looked like? All of them? Is that really what any house looks like? And why would they all be the same, when every house on a block looks a little bit different? Where are the two-story houses, the split-level houses, the apartment buildings? And why do the mothers all have long hair and the triangle that symbolizes dresses or skirts? Is that really what their mothers look like today? Who told them that a triangle symbolized Woman? Why does the tree look like a lollipop? Why is the sun a yellow circle with straight lines coming out of it—and, often, a smiley face?

The teachers offered up a wide range of interesting answers, including the following:

It’s what they’ve seen in books and magazines over the years.

It’s what they’ve seen their peers do over the years.

When they see their peers doing it, they change their picture to match what looks “right.”

They get corrected by their teachers, who unwittingly get kids to conform to what looks “right.”

They get preemptive instruction from teachers, who suggest using simple shapes (squares, triangles, circles) to keep kids from becoming frustrated.

I think these are all very plausible explanations, but think about what they do to the minds of the students. When any of these things happen in a classroom—and especially when they all happen —the result will be conformity—and, in this case, conformity to something that doesn’t even resemble reality. A student who enjoys science and knows what the sun really looks like will be encouraged (on purpose or unwittingly) to stop trying to draw a reddish-orange ball of burning gas and start to draw a yellow, smiley circle. He will start to learn that what he knows to be true is less important than what the adult in charge wants from him. A child whose mother has short hair and wears jeans will draw a mother who looks nothing like her actual mother. She will start to learn that aspects of her life are “wrong,” because they differ from some accepted norm. Little by little, they will all learn to substitute an approved, common vision for their own, singular visions. And then, sometime in middle school, we’ll start wringing our hands and asking what happened to their creativity.

According to research by the Right Question Institute, as children become verbal, the number of questions they ask in school shoots through the roof, but then begins a slow decline starting at around grade three. By age 18, they are hardly asking any questions at all. Now, one could argue that this decline happens at about the same rate as their reading and writing skills develop, showing that they have a decreasing need to ask questions in school because there are finding their own answers.

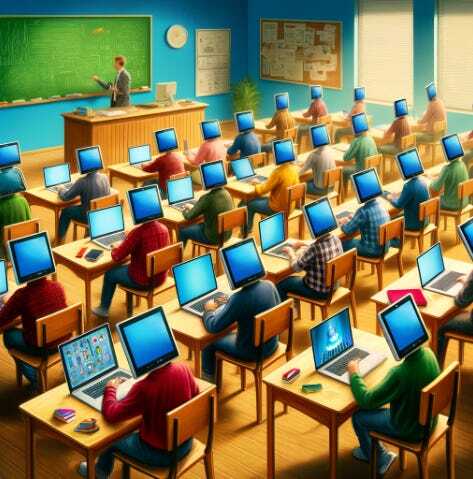

That’s possible. But anyone who has ever taught middle or high school would snort with amused disbelief at the idea. In fact, far too many of our students become increasingly uncurious about the things taught in school. Not uninterested, necessarily, but uncurious. They learn not to ask questions, because they learn that their questions are not considered important—only the teacher’s questions matter. The adults mandate what will be studied, and how, and what aspects of the material matter. The job of students is to answer questions. The job of students is to be compliant and responsive and well-behaved. There is no room for curiosity in the lesson plan. Where curiosity flourishes (if it does so at all) is at home, where they can pursue their own lines of inquiry about their own interests in their own ways.

Curiosity is not absent from our learning standards. The Common Core State Standards, and standards in many non-CCSS states as well, ask students to form and write personal opinions in the younger grades and evidence-based arguments once they get older. More straightforward, informational writing is still important, but far less important than developing the skill of argument. This new focus is not accidental or without purpose. As the Council of Chief State School Officers write:

The ability to frame and defend an argument is particularly important to students’ readiness for college and careers.

Well. It’s hard to make an argument if you aren’t interested enough about what you’re studying to develop a point of view. It’s do-able, certainly, but it’s painful to write and even more painful to have to read. Argument requires little curious engagement—enough for a question, even a little bit of “I wonder” to form itself in your mind.

The standards of mathematical practice likewise talk about the importance of argument. The first standard asks students (at all ages) to “reason abstractly and quantitatively,” and the second standard asks students to “construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.”

If curious engagement leading to evidence-backed opinion and argument is what we expect students to do, how can we make sure that we’re not inadvertently steering them away from those goals as they grow up with us?

Changing What We Ask ForAn easy first step is to change the way we phrase our learning expectations. Every teacher learns, as part of her training, that lesson objectives must be clear, concrete, and measurable. And most of us learned to write our objectives using SWBAT language: “Students will be able to…” followed by that clear, concrete, measurable goal. For example:

Students will be able to support a topic sentence with evidence.

There’s nothing wrong with that objective…except that it tells students what they will do, rather than inviting or challenging them to do something. And that’s not an insignificant difference. If we want students to be curious, not just compliant, then we need to give them something to be curious about—something to make them sit up and go, “huh.” Imagine if we phrased that learning objective as a question instead of a command:

How can you convince readers that your argument is valid?

Or even:

What’s the most effective way to win an argument?

Think about how differently those sentences register and resonate in your head when you hear them. The statement is impersonal and commanding, where the questions are personal and inviting. When you hear the questions, it’s hard not to start thinking of a response or at least wondering what a good response might be. The questions challenge us and pose problems to be solved. The statement simply tells us to do stuff.

Now imagine what you could do if that lesson objective was part of a larger unit—maybe even an interdisciplinary unit—that looked at all the different ways we have of figuring things out, as humans. What does it mean to prove something happened in history? What does it mean to prove a hypothesis true or false in science? What kind of truth does a poem contain? What if we used a question to frame the entire unit—something like this?

How do we know what’s true?

There’s a question that connects academic content to the student’s own world and life and concerns. And why wouldn’t we want to do that? Isn’t that why we bother teaching them all of the things we teach them? It’s not simply because we have a checklist of skills and standards we have to “cover;” it’s because we’re helping them learn to live in the world—successfully and happily, we hope.

Why not explicitly invite students to be curious and interested in what we’re teaching (instead of just hoping for it)? What we’re teaching is interesting and important! If it wasn’t, we wouldn’t keep teaching it, generation after generation. Let’s try to remind ourselves—and show our students—why the stuff of school matters. Who knows? Maybe they’ll ask a question that no one has ever asked before—or find a solution to a problem that no one has been able to solve before.

It’s not just about validating their quirky representations of reality when they draw a house for us—as important as that validation is. It’s also about encouraging and challenging them to imagine the house they want to live in someday, in the future they’re just starting to build.

May 18, 2024

The Things That Matter

Intro: Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose

Intro: Plus ça change, plus c'est la même choseMy great grandfather started practicing medicine in Brooklyn at the beginning of the 20th century. In his early years, he traveled by horse and carriage to see his patients. Before he died, in his nineties, he got to witness not only the moon landing, but also the deployment of our first orbiting space station, Skylab. That’s a hell of a lot of change in one lifetime. I feel old when I think about watching filmstrips in school and using a rotary telephone attached to the wall by a cord. I’ve got nothing on my Grandpa Dave.

When everything is changing and everyone is obsessing over the new and the shiny, my curmudgeonly side starts pushing back and telling things like AI and Gamification to get off my lawn (even though I have actively worked on products using both of those things). Part of me embraces the new and the cool, but part of me wonders just how much, or how long, the new and cool really matter.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

We love talking about “game changers,” but the teaching game hasn’t changed all that much in over a hundred years. I used to think that was a Very Bad Thing—that teaching was terribly conservative and resistant to change. But maybe it’s a good thing! Maybe there are some parts of teaching that actually shouldn’t change—approaches to education that just plain matter and shouldn’t be messed with too much.

If so…what are those things? What must a good education provide, regardless of what new tech or technique we use to deliver it? Here are my thoughts. What are yours?

Build SchemaWe spend a lot of time teaching facts, but not as much time as we should providing context for those facts and helping children develop schema, those mental models we use to organize and arrange discrete facts and put them together into ideas and concepts. We learn facts in order to build schema, and while we often forget a lot of facts once we leave school, we tend to walk away with some Big Ideas about the world and how it works. We have an understanding of the Civil War—why it started, what it meant, and what it changed—even if we’ve forgotten a ton of details about it. But if the way the subject is presented is all factual detail and no Big Ideas, our minds aren’t well equipped to organize and store things in long-term memory.

What’s New?Can new and cool technology play a role in developing schema? Why not? We’ve relied on paper graphic organizers for years to help students organize information, and putting those same charts and graphs in PDF format is only a baby step forward. I think we have a wide range of opportunities in front of us to use online annotation, organization, and collaboration tools to help students access, manage, and process information in radically more efficient ways—not only during the school year, but also across school years, throughout their K-12 journey. We’ve barely scratched the surface.

Build SkillsPart of what matters in education is methodical, planful training in the skills we will need for adult life: reading skills; writing skills; the ability to speak in public; the ability to manipulate numbers and perform calculations; the ability to break down a problem, organize important information, and make a plan towards solving that problem. This may not be the most engaging or creative aspect of schooling, but it’s critical. Part of what we want from schools is to make young people capable.

What’s New?Anyone learning a new skill, whether it’s multiplying fractions or shooting a layup or playing the piano, needs ongoing, timely, and relevant feedback. A coach or mentor needs to watch the learner’s performance carefully, provide support and encouragement, and intervene when necessary to tweak and improve the learner’s performance. Imagine how proficient a basketball player would be if he had to practice drills for two to three weeks by himself before receiving any feedback from a coach. That’s what happens far too often in our classrooms, especially as students get older. A high school student may have to wait a week or longer (sometimes far longer) to get an essay back from a teacher, and in many cases, all they get back is a grade. Even if a paper is marked up with red ink, it may be far too much feedback, coming far too late, to be of any real use.

This is where technology may be able to help—especially tools making use of generative AI. We are already seeing math and writing tools coming to market, promising to give personalized and timely feedback to an entire classroom simultaneously, providing instructional support at a scale and a pace that no single teacher could hope to do.

Build HabitsRelated to skills but slightly different is the idea of habits of mind—the ways in which we perform skills. In the working world, how you do a thing is often as important as whether you can do it (if not more important). Many people have tried to organize and systematize lists of these crucial habits for use in schools, starting with Arthur Costa and Bena Kallick, but extending to things like 21st Century Skills or Common Core’s standards of mathematical practice. You’ll see a lot of the same ideas popping up in these different lists: being resilient and persistent; working methodically and carefully; communicating clearly; thinking critically and analytically; taking calculated risks; questioning and experimenting; working collaboratively; and so on. Other than the math practice standards, few of these show up explicitly in state learning standards or in school curriculum frameworks, but they’re implicit in what most schools and teachers consider to be “good work.” Which means these things may be expected far more than they’re being taught.

What’s New?Can gamification help students feel more engaged and motivated, not only to practice key skills, but also to develop habits like resilience, precision, and thoughtful risk-taking? Perhaps. Recent research produced as part of the Responsible Innovation in Technology for Children (RITEC) project, funded by UNICEF and the LEGO Group, found that:

Digital games, when designed well, can allow children to experience a sense of control, have freedom of choice, experience mastery and feelings of achievement, experience and regulate emotions, feel connected to others and manage those social connections, imagine different possibilities, act on original ideas, make things, and explore, construct and express facets of themselves and others.

But gamification does not have mean only “playing a character-based video game,” or something that formal and structured. It can also mean any activity that allows students to be playful and experimental with the content they are learning—to stretch and pull at it like Silly Putty, to see what it’s made of and what it can do. I wrote about that here in a recent blog post:

As the historian, Johan Huizinga, writes, everything we think of as culture originates in some form of play. We are homo ludens—a species that learns through play. The statistician and author, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, says much the same thing in his book, Antifragile: our understanding of the world comes first from tinkering, and only later from scholarship. For us as educators, a text can be more than a thing to read and respond to; it can be a playground for students to mess about in.

While technology can help us provide structured games as supplements to the curriculum, it can also afford a myriad of opportunities for students to experiment, mess with, and play with the concepts and information they are learning, rather than simply learning X, writing down X, practicing X, and then writing down X on a test.

Find JoyThis one goes beyond having fun playing games or messing about with one’s learning. Joy is a thing you won’t find in any set of state learning standards or adjacent “habits of mind” schemes, and it’s a shame. If you speak to professionals and practitioners—actual mathematicians, scientists, historians, artists, or writers, joy lies at the heart of what they do. It’s what motivates them to do the work; it’s what they find in the daily practice of the work. It’s why they chose their profession. It’s why they bother. And yet, seeking out joyfulness—figuring out what resonates with you, what makes your heart sing and your mind race—is not considered a priority or a goal of our K-12 schooling. It think that’s foolish, and maybe even dangerous. Education should not be focused solely on teaching children how to do things that will someday make them money; it should also be focused on preparing young people to have rich and deep and joyful and rewarding lives in a rich and deep and complex world. So I’m putting “Joy” here as one of my essentials, even if the rest of the world doesn’t.

What’s New?Can new tools in the classroom, whether technology-based or not, enhance a student’s joy in learning? I have no idea. Maybe—but not unless joy is something the teacher cares about first. A teacher can light a fire of curiosity within the souls of her students, or she can snuff out the fire that’s already burning. So, while some piece of new or shiny technology might help enhance the former, I doubt very much that it could mitigate the damage of the latter. But I could be wrong. Tell me if I’m wrong.

Outro: Things Change…or Maybe NotAll right—those are my four non-negotiables, my four must-do categories for any education system: Schema, Skills, Habits, Joy. What does your list boil down to?

To wrap this up, here are two slightly different, but equally beloved, takes on our theme of change and persistence.

Dylan’s Take:

Tennyson’s Take:

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

May 13, 2024

Teach the Tension

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

T.S. Eliot’s poetic protagonist, J. Alfred Prufock, a favorite character from my high school reading, is permanently stuck. He sits in dull parlors and measures out his life in coffee spoons while feeling dissected and judged like a dead animal on display. It’s fitting that we read about him in high school, because far too often, that’s how teachers seem to treat their academic curriculum: like it’s a dead thing pinned to a display case—finished, fully understood, capable of being summarized in a mediocre book or lab report by any student paying meagre attention. Not just easily digestible by children, but pre-chewed for them. No wonder students are bored by it; I’m bored, just writing about it.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It’s an easy mistake to make. The curriculum is made up of skills and content: skills are things kids need to do; content is stuff kids need to know. “Stuff to know” suggests that the stuff is know-able and, in fact, already known by the adults and experts charged with teaching it. How could state boards of education approve of learning content and standards if it’s not all agreed upon? How can publishers make fancy books with glossy covers if the stuff inside isn’t pretty much settled?

There are two problems with this belief. One: a lot of what’s in those books is not really “settled.” Two: many of the things that are settled got that way through years of struggle. So we have historical struggle that may be ongoing or may be ended, and in either case, it’s rendered inert in a summary paragraph in a textbook. We know how the fight ended, so who cares about the fight?

Well, we should, for a variety of reasons. The fight is more interesting than the outcome, for one thing, and if we want our curriculum to be engaging, we shouldn’t jump straight to the end of the movie, or drain it of all its dramatic power by giving a quick summary. The fight can also be instructive—maybe as instructive as the thing being fought over.

Everything in the world that students inhabit—everything—came about through conflict and struggle, trial and error, hypothesis and experimentation, and sometimes sheer chutzpah. You could probably pick anything at random that’s visible to your students at any given moment, and find an interesting story about how that thing came to be—and, possibly, how it almost didn’t come to be. The world we have is a lot more contingent than we let on.

I was no fan of history as a subject when I was in school. I found it absolutely tedious. But the year after I graduated from college, I was asked to write a play about the treason trial of Aaron Burr for my university’s law school, which had a beautiful fake courtroom with abundant audience seating used for mock trials. (This was long before Burr became a well-known figure again, thanks to Lin-Manuel Miranda.) I knew nothing about the topic. None of my friends did, either. For all of us, our American history education went from the Declaration to the Constitution and then straight to the events leading up to the Civil War.

So, I went off to the library to research it. And man, what a fun and ugly and scandalous story it was! For the first time in my life, I was digging into primary sources (including the trial transcripts and contemporary newspaper reporting from a young Washington Irving) and the works of actual, grown-up historians—people who had contradictory ideas and opinions about the events, and who had amassed research to back up those opinions. Which of them was right? Which of them had an agenda? Was Burr really a bad guy? Was Jefferson really a good guy? What actually happened back then? WHY WAS IT SO HARD TO KNOW?

It was fascinating. And exciting. And I’ve been reading history ever since.

Why was none of that part of my high school curriculum? Why was I handed heavily edited summaries and conclusions about history, day after day, rather than being asked—even occasionally—to weigh the evidence and draw my own conclusions? Why wasn’t I given the opportunity to learn—to be guided carefully and planfully to learn—how challenging and fraught that process can be, and how tentative and cautious our conclusions should be? Some kids do get this experience, but why shouldn’t every 18 year old emerge from their K-12 schooling knowing how to research, how to evaluate, how to form an informed opinion, and, maybe most importantly, how to be humble about what they think they’ve learned? What would our recent experience with COVID, masking, and vaccines have been like in that world?

When you read grown-up history, not only do you plunge yourself into a world where people today disagree about what happened long ago; you also learn much more about the people who disagreed about what was happening while it was happening. And once you get beyond textbook summaries about who won and who lost, you can start appreciating the nuances of some of the arguments—you start realizing that in many cases, the battles were between different aspects of what is good and right, not simply between what is good and what is evil, what is right and what is wrong. The battles are hard.

There are arguments happening in our own political world that go all the way back to the founding of the country. Some of them you may be able to write off as good guys vs. bad guys—abject racists are bad; I don’t feel the need to consider their point of view. But many of those arguments have lasted for hundreds of years because they’re hard—because there is merit on both sides. On some topics, we are in a permanent state of tug-of-war, and we should be. We don’t really want one side to be completely victorious; we want to figure out where in the middle we want to live.

For example: we believe in personal freedom (the pursuit of happiness). We believe in equality (all men are created equal). These are both lovely ideas. But they often work in opposition to each other, not always in harmony. The freedom to pursue my happiness might mean the freedom to excel beyond others. Am I free to win, if other kids have to lose? Not everyone has the same opinion on that topic, especially where younger kids are involved. Mandated or legislated equality would infringe on freedom. And we want it to, to some degree. We want a leveled playing field when it comes to externals like race or class or gender. Do we want a leveled playing field when it comes to individual abilities? Kurt Vonnegut played with this tension nicely in his story, Harrison Bergeron. The goal for most of us, I think, is not either/or—it’s both/and. But how much freedom? How much equality? How do we want to balance that scale? When you demonize the other side of the argument, no balancing is possible—everything is zero-sum.

Freedom and security live in the same kind of tension, although we pretend they’re equal and harmonious goods. We want to be left alone to do as we please. We also want to be kept safe. I want cops on the street, but I don’t want them to stop me when I’m speeding, but I do want them to stop that other guy who’s speeding if he looks dangerous. I want to be able to move freely across state lines, without constant checkpoints and searches. I also want to be protected from terrorism. How much of one am I willing to sacrifice for the other?

People have struggled over these competing goods as long as there have been people. Our founders had them front-of-mind when they constructed our state and federal governments. As adults in a free society, we have to engage with these questions all the time. Why doesn’t our schooling do a better job of preparing us to be the kinds of citizens our country needs? Where else are we supposed to train young people to engage in the open, respectful dialogue and debate that self-governance requires?

Instead of racing through a curriculum of kings and wars and greatest-hits events, where everything is known and settled, and simply needs to be memorized, why can’t we slow down, every once in a while, and let kids grapple with things? Why not let them read contradictory accounts? Why not let them debate ideas—and be forced to research and represent both sides before knowing which side they’ll have to argue?

Wouldn’t we be more likely to give each other the benefit of the doubt in our complex, diverse society, if we had been trained in school to think more divergently, to learn that there are two or more sides to every argument, and that in most cases, all sides have some merit worth considering before rendering judgment? Wouldn’t we be better equipped to cast votes on the topics of our own day if we understood better what got us here, and how hard it was to get us here, and how many mistakes we’ve made along the way?

______________________

*The idea has been expressed, in one form or another, by authors as various as Thucydides, Machiavelli, Orwell, and (possibly) Churchill.

May 7, 2024

What We Learn From Our Teachers (re-posted)

(reposting from last April, in honor of Teacher Appreciation Week)

When online learning started creeping into the world, many teachers reacted with suspicion and alarm, assuming that the adoption of technology would interfere with, rather than help, their daily work, and would most likely be deployed by administrators to reduce staff and save money. I worked in two different online school management companies, and I heard these fears first-hand—and saw that they often were well-founded. Many virtual school operators certainly did (and do) want to find ways to increase the student-teacher ratio and improve their financial bottom-line. And, in the early days at least, the technology was more of a hindrance to instruction than a help.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

When starting from a place of fear and suspicion, teachers may not be the strongest and most confident advocates for themselves. And since they are often represented by labor unions, not professional organizations, the language of their advocacy often sounds more like job and wage protection than any kind of pedagogical treatise.

Do teachers matter? Will they always matter? Now that we have Chat GPT version 3, no 4, no 4.5…is it only a matter of time before generative AI does away with the need for an instructor?

I think the answer to that is, '“Yes If.” Yes, if you believe the sole, or even primary, role of a teacher is to deliver information (AKA “cover the curriculum”) and assess student performance. If that’s all we need teachers for, then we probably don’t need teachers—certainly not highly-paid, highly-credentialed ones. We have myriad methods of communicating information to young people now, many of them more engaging than a lecture delivered in a cinder-block room. And we have increasingly sophisticated ways of assessing whether students understand what they have allegedly learned and can perform the skills that they have been taught.

But is that all a teacher is good for? Is that even mostly what a teacher is good for? I don’t think so.

If I think about my middle and high school experience (the elementary years are too shrouded in mist now to be of much use to me), it’s not specific facts or skills that I remember, but passions, dispositions, and habits of mind. I don’t remember the content; I remember the people. And when I say I remember them, I don’t mean I remember this person being nice or that person being cruel. I mean I remember this teacher’s way of sharing her passion for history, or that teacher’s love of storytelling, or another teacher’s warmth and concern in hearing—really hearing—the needs of her students. I remember my teachers as mentors, and guides, and models of intellectually engaged adulthood. I learned the content and skills required of me, not because they were required of me, but because people I respected—people I wanted to impress, or be like—asked it of me and helped me to do it. That’s what a teacher does, that no AI will ever quite replicate.

Education is not simply a law; it is a rite of passage, a way of becoming part of one’s community. You learn your people’s history, their mythology, their way of seeing the world. You develop the skills necessary to perform a variety of functions in an adult world you are soon to become a part of. When I think of the various rites of passage I know about around the world and through history, zero of them are done completely alone by children. There is always a mentor; there is always a guide. There is always someone whose job it is to steer children through the rite and help them get safely across the threshold to a new state of being. Why? Because that transition is difficult. Sometimes it’s dangerous and scary. Oftentimes, a child would rather not do it—would rather stay in the nursery, among children, playing videogames and having a good time. Who wouldn’t?

In our society, which is bereft of real rites-of-passage, so many people (men especially) look, sound, and behave like teenagers well into their late twenties, or even beyond. I don’t think that’s coincidental. We do a poor job of expecting and demanding transition of our young people, and we continually insult and degrade the people whose job it is to guide our young people from childhood to adulthood. We celebrate and enrich our overgrown children, and we make fun of seriousness, of responsibility, of accountability. We would rather play. Who wouldn’t?

I will put it this way: we should respect our teachers, because there is no functioning society without them. A computer program that offers up content and assessments will blink uselessly on a screen, with no one looking at it and no one learning from it, if there is no caring, engaged adult creating a community of learning in which, perhaps, that program can play a role. A teacher says, “Here is the world; come be a part of it. I will show you how.”

I taught English because I thought literature was important, just for its own sake, qua literature. I was mistaken. Literature doesn’t have a sake. Only people have a sake. The world has a sake. If I don’t know how my subject of specialization can make life in this world better, for an individual and for a nation, then there’s no particular reason to teach it to everyone.

Teachers need to do a better job of making the case for what they teach, and why they teach, and why they matter. Because they matter quite a lot.

May 3, 2024

Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer's Day?

My post last week about the poetry of Passover got me to thinking.

We’ve seen countless news stories and blog posts about the importance of improving science and mathematics instruction in our country. In recent years, we argued endlessly (and fruitlessly) about the emphasis within the Common Core State Standards on complex, informational text. Everywhere you look, people are up in arms about our need to prepare students better for a complex, technological world.

I have no argument with any of that. I think it’s all correct, all on-target, and all necessary. And yet…

And yet, I think we’re missing something. We definitely need to help our students handle a wealth of concepts and content across all subject areas. But the place where many students have trouble is the grey area where facts are contradictory or confusing—where meaning isn’t quite clear or shifts from moment to moment—where the truth of the matter lies not in “this or that,” but in “both things at the same time.”

Why do we have so much trouble with this? Because we don’t teach enough poetry.

I know, it’s a radical proposition. It’s ridiculous. Poetry barely makes an appearance in state learning standards. It’s laughable—it’s esoteric—it’s a relic of an earlier, gently humanistic world. You don’t need poetry to get an MBA, write a legal brief, develop the next generation of massively-multi-player games, or design a higher-capacity car battery. So who needs it?

We do.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Why Poetry MattersWhen we teach poetry and focus only on rhythm and rhyme as the most important—most definitional—things, we not only leave out a lot of good poetry; we also miss why it really matters. Poetry is suggestive and sly; it thrives in the grey area of ambiguity—a liminal place of always becoming but never quite being. That’s what it does best. It hints and insinuates, often without resolving into anything concrete. Whether it rhymes or scans or just dumps words onto a page, what makes poetry poetry is its ability to hover in a place where things can be and not-be, both at the same time.

Take a look at this stanza from E.E. Cummings:

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

Look at lines 2, 3, and 4. Notice how they suggest two sentences without quite settling down into one or the other. If this were prose, it would say, “Who pays any attention to the syntax of things?” Or it would say, “The syntax of things will never wholly kiss you.” Cummings jams the two sentences together, with “the syntax of things” as the pivot of the seesaw. It’s both ideas at once; it’s neither idea absolutely. It lives in a weird limbo of thought that you can’t quite pin down. That’s what poetry can do, and it gives us a different kind of access to the world than journalism does.

I say, “it gives us,” but it doesn’t for everyone. Some people find poetry perplexing or merely irritating—as my 9thgrade students did, years ago, when I tried to teach the Cummings poem. My students were maddeningly literal—and not just about poetry. No matter what we were discussing, they wanted to know: What does it mean? Is it this or that? It must be this or that! Everything had one meaning—one answer—only. And it was my job to hand it to them.

The inability to handle ambiguity carries over into prose, of course. Poetry is a great place to learn it, but great writers make use of it everywhere. I remember teaching a Ray Bradbury story called “The Dragon,” in which two knights in armor prepare to battle a terrible beast. The dragon they describe breathes fire, has one horrible, yellow eye, is impervious to knives or spears, and travels the same path between two towns every night, mowing down anything in its path. In the final moment of the story (spoiler alert), as the knights attack the monster, the scene switches perspective, and we see two engineers on a train, mystified at the apparition they’ve just seen. Two knights in armor! They came out of nowhere. It happens every night. So weird.

“Ahhhh,” good readers say. The dragon is a train. The train is a dragon. Cool! But my students did not say, “Cool!” They didn’t get it.

I read the story to them again. They still didn’t get it.

I listed the attributes of the dragon and the attributes of a train, side by side, on the board (yes, it was a blackboard. I’m old). Now they kind-of got it. But they wanted to know: “Was it really a dragon or was it really a train?”

My answer was, “Yes.” They were not amused.

They weren’t stupid kids; they just couldn’t process the idea that a thing could ever be two things at once—that it could exist in a strange world of sort-of-being where both things (and neither thing) were, in some ways, true. They didn’t like that. There could be different perspectives, different points of view—they were fine with that—but one of them had to be “true” and therefore correct.

Is that because kids watch more video and read less text these days, and commercial, general-audience video is pretty much what-you-see-is-what-you-get? I don’t know. But I think it’s a very limiting way to see the world. And it’s not just a Humanities issue. Our inability to hold two contradictory ideas in our minds keeps us from grappling with the world in all of its confusing, ambiguous mess. Our belief that all things have clear explanations and definitions that are absolute and exclude all other explanations or definitions makes us partisans on every topic of discussion, from education to climate change to religion to science. There are always two sides, and your side is always the right side, and the other side is always the enemy. It’s a terribly reductive and simple-minded way to see the world, which is infinitely complex and strange.

The push to bring more primary source text into our science and social studies classes—to rely less on textbook syntheses and summaries—is motivated by exactly this understanding that students need to analyze competing and contradictory points of view, to learn how to compare, assess, and, ultimately, deal with areas where a single, simple solution is not reachable. But if we, as their teachers, do not have a facility for dealing with ambiguity—if we are not comfortable living in the grey areas—then we are going to be ill-equipped to help our students navigate those issues. They will be saying, “But what’s the answer?” And we will feel compelled to give them one.

Against a Flat WorldOf course, poetry and metaphor deal with much more than just contradiction or ambiguity. Metaphor is about association and resonance and connectivity. The snow is a blanket upon the earth. The blanket keeps me toasty warm. Toast is…well, maybe toast is just toast. But you get my point: metaphor creates connections and resonances among the things of the world. It catches us up in a net of relationships. It makes the world vibrate: touch one string, and another hums. Where there is no metaphor, nothing is like anything else, and nothing reverberates. The world just is—a jumble of discrete, isolated objects on a lonely plane of thing-ness.

When the world is reduced to discrete things, the only logical response to poetic imagery is to accept it as factually true or reject it as silly nonsense. Either the thing is a dragon, or it’s a train, and if it’s neither, it’s a stupid story. Sorry, Ferdinand, those are not pearls that were his eyes. They’re just eyes. The “sea change into something rich and strange” is…not.

On the plane of thing-ness, this approach makes sense. But the third option, beyond true and false, is vitally important. There is truth in poetry that’s very different—of a completely different nature—than the factual truth of journalism or history (as I discussed last week in terms of religious texts). When we see the snow as a blanket upon the earth, we think of winter differently: we catch the importance of that period of the growing cycle; we feel what it means to slumber snugly, to hibernate, to wait in the warm, dark place for spring to come, so that we can grow and bloom again. We are like the world; we’re part of the world. We know something that’s beyond mere facts.

Sometimes poetry tells us that there is no answer. And that’s fine, too. Sometimes, describing the mess accurately is the best thing we can do. “Describing the mess,” is how Samuel Beckett once defined his job when asked what his strange plays were all about. But he described the mess in ways no one before or since has managed. There are moments in Waiting for Godot that speak truth to me far more profoundly than what I’ve found in philosophy books or in the news. Especially this:

Astride of a grave and a difficult birth.

Down in the hole, lingeringly, the grave digger puts on the forceps.

We have time to grow old.

The air is full of our cries.

But habit is a great deadener.

At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing.

Let him sleep on.

That image in the first two lines chills me to the bone. If you painted a picture of it, it would be nightmare fodder worthy of Goya. And while it’s not literally true that we’re born astride of a grave, the text says something important about our brief sojourn on earth—and how much of it we tend to waste.

So listen. I’m all for better math and science education. I’m all for historical literacy. But we live in a world that can be oppressively fact-filled while also being bereft of wisdom. Knowing the structure and architecture of a thing is not fully knowing it. There are thirteen ways of looking at a blackbird, not just one. There is more to life than “the syntax of things,” as Cummings called it. It’s important to gather ye rosebuds while ye may. It’s important to hear your being dance from ear to ear. We’re not here for all that long (as Beckett reminds us). Time’s winged chariot is hurrying near, and there is so much—so much—to learn.

After all, as Cummings says at the end of his poem, “Life's not a paragraph / And death i think is no parenthesis.”

April 27, 2024

The Poetry of Passover

Some old and new thoughts on the season—revised and added to from my old blog…

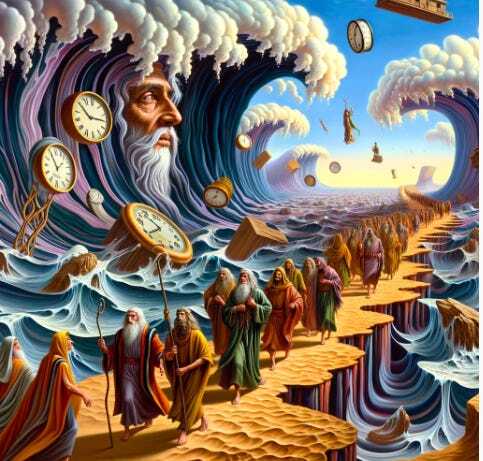

Here it is, Passover. As usual, I get irritated by the literalists—the historical literalists who insist that the Exodus must have happened as written for it to have any meaning, and the ritual literalists, who insist on leading the Seder as though every page of the Haggadah must be read out loud, in order, as is, for the evening to have any meaning. I reject both points of view.

And I’m not fond of the atheist literalists either, who insist that if the story of the Exodus is not factually true, it is without meaning or use.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

To me, the story might actually have more meaning if it's not historically true. Why would our ancestors have chosen to make this story of enslavement and redemption their founding myth? Who does that? Every other ancient culture saw itself as descended from gods or heroes. The Jews saw themselves as descended from slaves. What does that say about us, as a people?

As a writer and a former English major and English teacher, the fact that something may be poetry does not mean that it isn't true. There is truth in poetry—sometimes greater truth than we find in history.

What does the poetry of Exodus tell us?

Does it matter whether the Red Sea was really parted and crossed? Not to me. What matters to me is the imagery of something enormous being crossed by the Israelites, and then being closed behind them. It means that true freedom requires a boundary-crossing in a way that does not allow for backsliding and return. We see the Israelites bicker and complain constantly that they are terrified of the wide, empty road ahead of them. With every challenge, they beg to return to Egypt. It's important, both poetically and psychologically, that the door behind them closes, and that the only way forward for them is forward. If all of the oppressed peoples in history had been able to close the door on their past so definitively, they might have been able to move more confidently forward into freedom.

How about the 40 years in the desert? What does it mean that the slave generation had to live out in the wilderness and die there, and that only their children, the ones born in the open spaces of freedom, were the ones able to understand the commandments given to them and use them to build a new nation for themselves? How many peoples throughout history have had the benefit of "40 years in the desert" to learn how to be free? How many have had the luxury of not having a new tyrant breathing down their necks and waiting for them to fail? We, in America, had that luxury because most of the rest of the world was separated from us by two oceans that took a long time to cross. Who else has been so lucky?

What about the building of the calf and the giving of the law? Huge. Someone once made what he thought was a nasty joke to me, saying, "Only the Jews would come up with the idea that laws equal freedom." But I didn't find it nasty or funny. I said, "You're damned right. Because laws do equal freedom.” Without law, all you have is chaos, and chaos leads straight to tyranny. If you don't have some laws or principles that allow you to self-govern, it won't take long for you to turn to some strong man and say, “if you feed us and keep us safe, we’ll let you rule us.”

In our tradition, the Torah is not a book that you’re simply supposed to swallow whole without reflection. That’s why we read it every year and start it again as soon as we finish it. My heritage and culture teach me to wrestle with the book, to argue with it, and to learn from it constantly. And the only way to do that is to let the words and images resonate with me—to let them bounce around and reflect off things and work on me in different ways.

Like a poem.

So here we are again. Another Passover. Is the story ancient and dusty? Or does it still speak to us? Do we have strongmen in our midst who want power without consequence and loyalty without question? Do we have people living in places where their rights are being whittled away, but it’s scary and difficult to pick up and leave?

It's hard to stand up against Pharaoh and demand your freedom. It's hard to remember that you are valuable and important, when all your life you've been told you're not. But we tell the story every year, because it can be done and it must be done.

It's hard to cross that sea and leave the past behind, knowing that when the waters close behind you, you can never go back. It's hard to embrace real freedom, when all your life you've been dependent on authority figures telling you what to do and what to believe. It's hard to take full ownership of your life, your beliefs, and your decisions, and know that, whatever comes, it's all on you. But we tell the story every year, because it can be done and it must be done.

May we all be brave enough in the coming year to tell off our personal Pharaohs, get out of whatever situations or mindsets we have become enslaved to, and wander through whatever wilderness is required to get us to our promised lands.

Pass through it, pass under it, or pass over it. Just keep moving.

April 17, 2024

Little Boxes

I have been reading Ghosted, a new memoir by Nancy French, and it’s a compelling and incredible story. I’m only at the halfway point, so I haven’t gotten to the actual “ghosting” part, in which the entire Conservative movement declares Nancy and her husband, David, personae non gratae for committing the sin of not supporting Donald Trump. They’re kicked out of the tribe. They no longer fit.

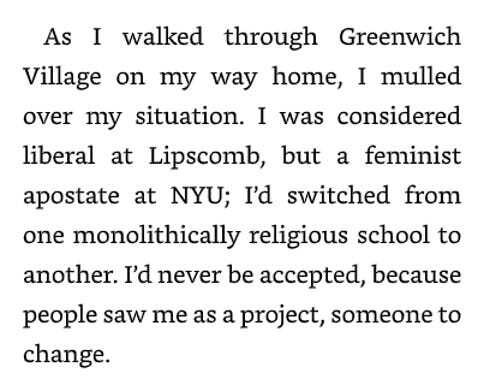

There are pre-echoes of that theme earlier in her story, and one of them really jumped out at me. It occurs when Nancy leaves her rural, southern roots and moves with her husband to New York City. She starts taking classes at NYU, and in a class on feminism, she has this encounter with her fellow students:

After class, she has this thought:

They saw her as someone they needed to change, but they also saw her as someone who didn’t fit—someone who was just…wrong. She couldn’t be a feminist; they already knew what a feminist was. Their definition was right; this person had to be wrong (ah, back to my old friend, the platypus).

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The passage jumped out at me because I remembered a friend who had a similar situation back in the early 2000s. She was a curriculum writer on my team. She was an Army wife. She confided in me one day that she felt caught between two worlds. On the base, in her military community, she felt like a liberal outlier compared to the other women she spent time with. Their views sometimes made her uncomfortable, so she tended to keep her opinions to herself to avoid problems (especially during the early days of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars). She was one of them, but she didn’t quite fit in. But now, here at work among predominantly liberal educators, she felt no better. Her lived experience was very different from theirs, and she found that many of her views were now to the right of everyone. And so, once again, she kept her opinions to herself. She had no place where she felt safe to be fully herself. Everyone had their nice little boxes defining what it meant to belong—little houses on the hillside, as the old song goes—and she didn’t quite fit into any of them. And the doors and windows were shut tight.

We humans have a tendency to take the symbol for the thing-symbolized. We pledge allegiance to the flag, but we too often abandon the people who make up “the republic for which it stands.” We invent definitions and distinctions to help us understand the world, but then we forget that the world is what matters, not our definitions and distinctions.

George Orwell says, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” But what is in front of my nose? Is it just what my five senses are capable of perceiving? I can tell you right now that my senses can be sub-par. I’ve worn glasses most of my life. I know that what my eyes can see is not all there is to be seen, no matter how much I squint. And even if all five senses were firing on all cylinders, I know there’s a lot more out there in the world. A snake can perceive infrared radiation. The images they can see in the dark are “real,” aren’t they, even if none of us can see them?

Okay, maybe that’s too weird. Forget about snakes. Let’s stay with humans. If ten of us took photographs of the same landscape with the same camera, would the pictures be identical? Not likely; we’d frame and light and edit things in our own, individual ways. What Ansel Adams saw at Yosemite was a vision uniquely his. And if we used paint, the results would diverge even more. Whose landscapes are more “real,” Monet’s or Van Gogh’s—or, God help us, Dali’s? Am I supposed to judge which person has the right to say, “this is real,” or even, “I see what I see?” Are any of them truly wrong?

It seems to me that “reality” has to be a composite—a multi-faceted prism rather than a single pane of glass. If we want to understand the reality of the world around us, we need to look through different lenses and listen to different voices. That’s the world we actually share, if we care to know it.

And those different voices…are they unitary within the little boxes we’ve created for them? Is there only one way to be White or Black? One way to be a southerner or a Yankee? One way to be a Conservative or a Liberal? One way to be a feminist? Or a Christian? Or an American? Do we really think each of the boxes we created to help us make sense of the world holds only one example?

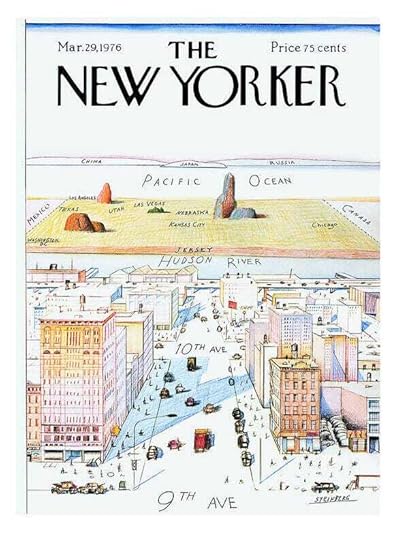

I sure acted that way, growing up. As a kid in a liberal, Jewish household in a liberal, Jewish suburb of New York City, I barely understood the breadth and diversity of the Jewish world, much less the Christian one. And life beyond the Northeast? That was about as well defined in my mind as in that famous New Yorker cover:

What did I know of Christians or Conservatives, for example? Nothing. I wrote a paper on Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority for a high school history class, in 1980 or 1981, when his political influence was at its zenith. I did some primitive research on who he was and what he was all about. I’m sure if I read it now, it would reek of self-righteous, teenaged, liberal bias. Why wouldn’t it? What did I know, besides what my parents and their friends said, and what I read in Time magazine?

I’m not saying I was wrong about him, mind you. I’m just saying I didn’t go to a lot of trouble to find out whether I was right—or whether there was any nuance to the picture I was painting.

College and travel and life helped break me out of my bubble a little, and learn how small my childhood world had been. But even then, I traveled in small, concentric circles, spending all of my days with the same kinds of people: theater people and teachers. It took me a long time—far too long—to get over my shyness and introversion and just talk to people outside my circle. Say hello to people at counters or in elevators or on a bus. Engage them in conversation. Listen to them. It took watching an old favorite movie again, “Harold and Maude,” and hearing Maude say, when Harold praises her for being good with people, “Well, they’re my species.”

So simple. So dumb. But that line haunted me for weeks, and it made me want to do better with my species. I’m still working on it.

This Internet thing has helped. I have access to so many people now—people from different upbringings, people with different faith traditions, people with different political convictions. And sure, some of them are bad actors with ugly motives. Some of them are trolls. But most of them—most of the people I’ve encountered online—have been lovely. I’ve read and listened to Progressives far to my left. I’ve read and listed to Conservatives far to my right. I’ve learned from people who talk about religion and family and education and politics in ways I was previously unaware of—people who are funny, thoughtful, sardonic, wise, curmudgeonly…you name it. Interesting. Different from me in a hundred ways. Sometimes they challenge me to rethink my assumptions. Sometimes they help me reinforce my conclusions. Regardless, it has been gratifying to learn from them and to understand—just a little bit—the different and sometimes contradictory ways that people of good faith and good intention see the world.

Not everybody thinks this way, I know. A lot of people don’t feel the need to go past their front yards and get other people’s perspectives, because they already know they disagree. Why waste time listening to people you already know are wrong? It’s exhausting and pointless. Sometimes crazy-making.

Why should it make us angry or crazy to listen to our neighbors talk about the world around them, though? Experiencing variety shouldn’t confer any obligation to approve one part of it or condemn another part. It’s all free samples; no one’s forcing us to buy. And yet, so many of us respond to the offer of the world beyond what we know by saying, “No thanks; I’m good.”

It’s not just about respecting other people’s opinions or being open to changing your mind about something. I think it’s more about taking in the variety and strangeness of the great, wide, world, just for its own sake, because it’s there. It’s about accepting the gift that has been given to us. As Annie Dillard says, “beauty and grace are performed whether or not we will or sense them. The least we can do is try to be there.”

I want to be there. I want to be there better—for my friends, for my family, for the handful of people who read this blog and the random things I post on social media. But mostly, I want to be there for me—because it feels like a better life, more capaciously lived.

“Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind,” Emerson says. And I get that. We need to rely on ourselves and trust our own vision. We need to stand up for what we believe. But we also need to be brave enough to see and make room for other people’s visions, providing they’re not Nazis or other monsters. We need to make a safe space for the decent people we meet, and hear them out without instantly judging or dismissing them. Instead of leaping to put them into a box or force them out of a box, we need to find ways to simply embrace them as part of the messy and chaotic reality of the world we live in. After all, they’re our species.

April 13, 2024

Can't Dance, Won't Dance? Better Learn How to Dance

Baruti Kafele, a school principal turned inspirational speaker with whom I’ve worked several times, used to love quoting an Ashanti proverb to throw cold water on teachers’ complaints about all the things allegedly standing between them and good instruction: “He who cannot dance will say the drum is bad.” He’s a no-excuses kind of guy, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t acknowledge challenges and difficulties. There’s a difference between a reason and an excuse, and God knows there are plenty of reasons why teaching is hard—especially today. But do we accept them as excuses for why we can’t get to Good?

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

When it comes to complaints about the over-use of technology in the classroom, I don’t want to take the Cher approach…

But I do think we need to find ways not to blame the drum, because…that drum isn’t going anywhere.

There was an opinion piece on classroom technology in the New York Times last week that got a lot of attention around my workplace, which is not surprising, given that I work in ed tech. You don’t have to go any further than the title to know what its take is going to be: “Get Tech Out of the Classroom Before It’s Too Late.” If the Times style guide allowed exclamation points in headlines, there would have been two or three in this one.

There are real and serious issues explored in this piece—elementary and middle school students getting access to violent YouTube videos while in school; kids reading “almost exclusively on iPads because their school districts had phased out hard-copy books and writing materials;” teachers finding it difficult to hold the attention of their students when technology is at their fingertips. These are real concerns. I just don’t think “getting tech out our classrooms” is a realistic solution. As with so many things, the extreme pendulum swings are not where the best solutions lie. There is a happy medium to be found, and it’s not in yelling at the drum; it’s in learning how to dance better. It’s hard work, but it’s on us—all of us—to do that work.

I heard from many parents who said that even when they asked district leaders how much time kids were spending on their screens, they couldn’t get straight answers; no one seemed to know, and no one seemed to be keeping track.

That quote is part of the problem—maybe the root cause of the problem. It’s the responsibility of school leaders to know what they’re bringing into a building and how it’s being used, whether that’s a textbook, a computer, the mystery meat being served for lunch, or a piece of athletic equipment. I know, I know. “There’s so much, it’s so complicated, how can I possibly keep track?” I get it. But too bad. You have to keep track; you’re the gatekeeper. You’re the guard at the door, and there are children inside. Do the due diligence.

Are some tech companies being irresponsible and greedy? Are they overpromising and underdelivering? Are they not putting adequate guardrails around their products? Are they designing their products deliberately to be as engaging and “sticky” as possible? Yes, my sweet, summer child: some companies in the great marketplace of life are bad and irresponsible actors. Welcome to Capitalism.

Some; not all. Some companies providing tech products and services to schools take their jobs and their responsibilities very seriously, and try hard to be good actors and honest brokers. Ask around; find out who you should trust…and how far you should trust them. Caveat emptor.

But the drum itself doesn’t make the dance. Bringing the right product into the building is part of the battle, but how the product is used matters, too. When, where, how often, and how.

"Letting kids do whatever they want on laptops or phones all day," is no one's idea of good teaching, so why is it happening? I think it happens because there’s a gap between good intentions and actual implementation. As T.S. Eliot says, “between the idea and the reality falls the shadow.”