Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 4

March 1, 2025

[2025 Re-post] Wandering

I had a few ideas for things to write this week, and a couple of pieces that were already in draft form. But I’ve been so disgusted and exhausted by the gleeful recklessness and cruelty of our government that I didn’t have the heart to finish anything. None of it seemed to matter, or none of it felt like anything I had a right to be opining about. So, here’s something a little gentler and more personal that I posted a while ago.

When I’m in the right frame of mind, any dirt road I’m on becomes the first dirt road I ever walked—a quiet, residential byway that snaked along Stockbridge Bowl in the Berkshire mountains of western Massachusetts. Wherever I happen to be, if it’s quiet enough to hear pebbles crunch under my feet and a breeze blow through the weeds, my mind takes me back to my original happy place, meandering along the quiet, one-lane road that connected summer homes in a development called Lake Drive.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when I was a child, the skinny tail of Stockbridge Bowl that led to a waterfall was bounded on both sides by cottages. The side called Beachwood was more built-up and populous; the side we were on, which didn’t even have a name when we moved there, was more sparsely populated, especially as you moved out of the woods and into the open air. There were fewer houses there, closer to the waterfall; newer, bigger, more modern. The road seemed to change, too, perhaps from more exposure to sunlight. The rocks and pebbles seemed whiter and cleaner, and the crunch under my feet felt different. Down where we lived, the woods were denser and the cottages seemed smaller and older.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Lake Drive started on Route 183—just an unmarked turnoff back in the day, and then, later, marked only with a small sign. Even today, the entrance is unassuming. Driving down the dirt road towards the woods, you curve past a field of tall weeds, unsure what the purpose of this road might be. It isn’t until you enter a cave of dense trees that you can see that people live here.

The cottages, deep in the shade of the woods, were an idiosyncratic lot back then; no two looked the same. Some had lawns; most simply lived nestled in the woods. Most looked hand-made. Some were. I remember watching a neighbor build his own house. I would occasionally run back and forth for him to bring him tools. He rewarded me by placing an acorn I had given him up on the roof as part of the chimney.

Our house was tiny—a single story, with an open living room/dining room plan, one bathroom, and three small bedrooms. It was non-functional in winter weather, so we boarded it up at Labor Day, drained the pipes, and left it behind for the bulk of the year.

In front of the house was a large patch of dirt that refused to turn into a lawn, with a rapidly rusting swing set. Halfway down the front yard, there was a a pathway cutting through the woods down to the dock where I could sit with my dog, communing with local ducks and geese.

We had an old rowboat, which was mine to take out whenever I wanted, once I knew how to row it. Sometimes, I tied up at a small island and pretended to be Tom Sawyer. Mostly, I just liked to row out into the middle of the lake and drift, reading a book and dreaming my dreams.

I wandered a lot during those childhood summers, totally unsupervised. I don’t think my parents ever knew where I was, and I don’t think they ever worried about the fact that they didn’t know, as long as I was back by nightfall. We had two acres of woods around and behind the cottage, and they were mine to explore. There were giant, limestone boulders strewn about, that I could scamper up like a goat, grabbing handfuls of moss to help haul myself to the top. Some were quite tall; one, behind our cottage, was as high as the house. I liked to find long, thick tree limbs on the ground (long to me, at least), and use them to lever myself off the tops of big rocks, swinging through the air and crashing down into the leaves below. It’s a good thing I never broke a leg, because it would have been hours before anyone knew I was in trouble.

And I walked. I walked up the road, out of the cave of trees, to have private little picnics in the field of weeds, opening milkweed pods and playing with the maple tree seeds that had helicopter-rotor wings on them. I walked down the road, along the lake outlet, passing my hands along the flat tops of queen anne’s lace and listening to the rhythmic crunch of my feet on the sand and pebbles. I walked to the waterfall and over the little, wooden bridge that finally, at lake’s end, connected Lake Drive to Beachwood. And then I walked back, humming made-up songs about weeping willow trees.

So much time alone with my thoughts and dreams and songs, with nothing but wind and birdsong to accompany me. How could I have known how rare that time and that silence would become?

Last week, we went down to Cape May, in New Jersey, with my wife’s family, for our annual time at the beach (sorry—the shore). There were 11 of us in the house, spanning three generations. It was happy and fun, but it was loud. One day, I rode my rental bike out to the state park and walked along the nature trail. Each morning, I’d been running along the boardwalk with the usual music or podcast voices in my ears, and it was always a nice respite—but this day, I rode without headphones and then walked in silence.

The nature trail has a long expanse of handsome, raised, wooden walkways, but deeper into the woods, the walkways disappear and turn into paths of dirt and then, closer to the water, pebbles and shells. And as I walked alone, with no electronic noise in my head, I heard my feet crunching rhythmically on the road below my feet, and I was home again—picking queen anne’s lace and singing to the trees.

It requires some silence, which is harder and harder to find, and harder to grant ourselves even when the environment allows it. It requires some silence and some time to let the world recede a little, to let your brain stop reacting to the constant stimuli of life. The world is too much with us, as Wordsworth says. Sometimes we have to get away from the world we’ve made and touch the earth we didn’t make, to remind ourselves where we really live.

It’s not merely a dirt road that sends me back into my childhood; it’s a dirt road and a long stretch of silence—long enough to let that rhythmic crunching lull me into a sort of trance so that I can let the balloon string go and allow my mind to float and wander where it will. I keep that brain on a tight leash too much of the time. It’s nice to unclip it and let it run free. I wish I remembered, more often, to do that.

I was lucky to have those woods when I was a child. I was more than lucky; I was privileged. We need to protect the wild spaces we have—especially our public, wild spaces, so that everyone can have access. But we also need to protect our souls when we’re in those spaces, by pausing the constant bombardment of words and music, just for a bit. More than a bit, actually. It takes some time for the roar to recede and for anything else to have a chance.

Will it seem boring? It might seem boring, especially if we’re not used to it. But maybe we should give ourselves the gift of occasional boredom in this world of constant stimulation. Take a walk without purpose or goal, listening only to the world around you. Do it until you get antsy, and then do it a little longer, letting your mind sink deep into yourself and, at the same time, fly free.

I know where my thoughts like to go. Where do yours take you?

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

February 20, 2025

The Velocity of Care

Now I will do nothing but listen,

To accrue what I hear into this song, to let sounds contribute toward it.

I hear bravuras of birds, bustle of growing wheat, gossip of flames, clack of sticks cooking my meals,

I hear the sound I love, the sound of the human voice….

— Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself”

Our Special JobIn certain strains of Jewish mysticism, it is said that when God wanted to create the universe, he had to contract some part of himself from the everything-that-was-nothing in order to make room for some something. He channeled the divine light of creation into vessels of some kind, but they shattered and scattered shards of light throughout the world—light that we humans are tasked with finding and bringing together so that what was shattered can be healed.

This idea of healing the world is called Tikkun Olam, and the phrase is used both mystically and in more pedestrian, everyday ways. Tending to the sick, feeding the hungry, repairing what’s broken—it’s not merely charity; it’s our cosmic duty. It’s our partnership with the almighty.

Partnership! It’s a concept I’ve always found fascinating, because if God is “almighty,” then what does he need us for? What does he need, period? Isn’t the whole idea heretical? If you’re omnipresent and omniscient and omnipotent, why do you need a partner to complete the creation?

Here’s what I think: if you are omnipotent and eternal, the one thing you can’t be is limited. You can’t really understand what it means—what it feels like—to be fragile, to be a mayfly that comes and goes in the blink of an eye. We humans may be created in God’s image, but we can break in a million ways that he can’t. We can die. We will die—and we know we will, someday. Existential dread is our jam.

And I think that may be the missing piece that’s needed. Because when you’re breakable and mortal, you can have empathy for other creatures who share those traits. You can sympathize. You can exercise care. You can love.

Some people say that God is love, but I’ve never bought that idea. I say you can’t feel love or make love or do the things that love requires unless you live down here, close to the ground, close to the mud, where you can hear hearts beat and see blood ooze. You can love only when you understand what you stand to lose.1

That’s my take. It’s our job to heal the world because only we can feel the wounds. That’s what we’re needed for.

The Algorithm Can’t Love YouWe are inventing technologies that have tremendous power and may soon learn how to learn and grow and correct their errors. Will they become infallible? Will they become omnipotent? Will they decide, someday, to make it impossible for us to turn them off?

They’re certainly verging on the omnipresent. And they already receive a fair amount of worship.

Someday, they may become what we decide to call intelligent, or sentient, or alive. For all I know, they already are. They can churn through vast amounts of information in the blink of an eye and perform analysis and summary and synthesis at speeds we never dreamed of. They can answer questions better than any oracle or genie we ever imagined.

There are some people who would love to turn many or most functions of business and government over to the algorithms and the large language models. Some of those people would like to start on that project immediately. Some of them may already be doing so.

But can AI consider? Can it wonder? Will it take our feelings into account while working its way towards answers? Does it understand what it means to be a person? Or is that something that only fallible, limited humans can do?

I’d like to know. I think it’s important.

There are a million questions that need answering. Some of them I’m happy to entrust to calculators and algorithms. Some of them I’m not.

Respect Your Radical AncestorsSomewhere in Europe, sometime in the 17th century, people started having crazy ideas. Maybe this bunch of French and Englishmen came up with the ideas by themselves; maybe (as David Graeber believed), they picked them up by reading about encounters between Spanish Jesuits and indigenous leaders in the Americas—curious and savvy operators who were incredulous about how these weird Europeans said they lived. Either way, people in Europe and then here in America started entertaining some radical “what if” questions: what if kings weren’t actually anointed by God? What if priests didn’t have any more access to the truth than peasants? What if the power to rule and make important decisions rested with us…and always had? What might that look like?

A king or a priest’s decisions must always be correct and can never be questioned, because their power to decide comes straight from God, and God, as we said, is infallible. But if we take that “consent of the governed” stuff seriously and decide that the power to make decisions lives with us, fallible old us, how can we know we’re making the right decisions?

We talk it out, that’s how.

The Cooling SaucerThe differences of opinion, and the jarring of parties in that deliberative assembly, often promote deliberation and circumspection; and serve to check the excesses of the majority.

— Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 70 (1788)

The algorithm doesn’t deliberate, any more than God does. The process is invisible, inscrutable, and internal, and the decision is final.

The rest of us need to talk.

We talk at coffee shops. We talk at the pub. We talk at town hall meetings, and school board meetings, and public debates. We talk and we talk. Sometimes we even listen.

As heated and passionate as the talk can get, the mere fact that we’re talking to each other can have a cooling effect, because it delays action. It allows tempers to flare, but also to subside. It gives people a chance to hear each other. It provides room for people to change their minds. If we keep talking, there’s a chance we might actually stumble into rational thought—which, as we know, is hard work that our brains would prefer not to do. As Daniel Kahneman has taught us, thinking fast and thinking slow are two very different ways of thinking.

George Washington allegedly said that the purpose of the Senate—with its fewer members serving more constituents for longer tenures—was to be the cooling saucer into which the hot tea of passionate debate from the House of Representatives could be poured. A rush to judgment was not considered a virtue. “Delay,” Thomas Jefferson wrote to Washington in May of 1792, “is preferable to error.”

Of course, they lived in a world where things moved more slowly, and there was time to have a second or third thought before the hammer of action fell down on you. Even shooting someone with a musket required half a minute of prep—plenty of time to change your mind.

In a world where everything has sped up, where we expect instant service and instant delivery and instant response, can we still value unrushed discussion and unhurried decisions…anywhere?

The Thrill of Breaking Things“Move fast and break things,” is the mantra of the tech world, and it’s thrilling to break things—we all know that. It’s reckless and risky and it gets your heart beating. There’s something irrevocable about breaking things. It gives you a feeling of power. It makes you feel like you’ve done something.

I remember being in summer camp one year and rampaging with some friends through the possessions of one of our bunkmates whom we hated. We threw the batteries from his radio into the woods, then we cut holes in his underwear—we even cut a bar of soap in half. Before we knew it, we had destroyed everything he had brought to camp. Everything. We didn’t plan on doing that; we just got carried away. Carried away by forces beyond our control. We were serving some savage god, and we were in its grip and doing its bidding. Don’t pretend that isn’t a powerful high.

Move fast! Break things! Get Shit Done! Absolutely. But is there time to ask if the shit you’re doing is good for you? If it’s good for the people you live with? If moving that fast and breaking all that stuff accomplishes something positive?

And if it is positive—if there’s stuff that needs breaking in order for us to move forward and build something new—what’s the rush? Let’s be honest: don’t you move fast mostly to avoid thinking about what you’re doing? Don’t you move fast mostly to make sure you don’t have time to second guess yourself—or let others second guess you?

Hey, man, if you didn’t like it, you should have said something. Too late now! Anyway, it’s not my fault; I got carried away.

Slow Your RollThere are things in this life that, once broken, are hard to put back together. Maybe impossible. Our country might be one of those things.

I’d like the people with figurative machetes to take a little time before hacking at the limbs of our government and culture. I’d like them to take a little time to think about what they’re doing. Time to deliberate and talk it through. Time to—yes—second guess themselves, do a little research, ask a few questions. Time for something more than a spasm of reflex between impulse and action.

Without that pause to think, they may find themselves ashamed and aghast someday when they come down from that drug of action, when they’re standing in the ruins with blood on their hands. For their sakes and mine, I’d like them to take a little time. Even in our little, mayfly lives—even when the world is moving at the speed of light—a little inefficiency feels like a small price to pay.

There’s already too much that’s broken and wounded in this world. We don’t need to add more to it. There are only so many hands available to stitch up the wounds and put those shards of light back together into something whole. It’s a hard enough job already.

Breaking stuff is easy. Anybody can break stuff. We were called on to do better.

1Christian friends, I see your hands raised. I hear you saying, “But…but…but…”

I think I know what you want to say, and I think I should leave it to you to say it—here in Comments if you like. It’s not my place.

February 14, 2025

Where Do You Stand?

Here’s What I Do on Monday Mornings

Here’s What I Do on Monday MorningsOne day a week, I volunteer at the Raritan Learning Cooperative, in Flemington, New Jersey, to teach a class called, “Where Do You Stand?” The cooperative follows many of ideas laid out in A.S. Neill’s seminal book, Summerhill, and is offered as a support to homeschooled students for whom traditional schooling has not been a good fit. The core staff and a group of volunteer teachers offer a variety of classes, filling up the hours of a school day, but students decide with their advisors what they want to take.

Neill’s theories, which he put into practice in his own school in the 1920s, and which have been embraced by a handful of other schools ever since—notably the Sudbury Valley School in Massachusetts—was that removing compulsion from education would lead to faster and more engaged learning, even if some students took a while to latch on. Neill found this to be true in his own practice: many kids started reading later than they would have in traditional schools, for example, but they quickly caught up with and surpassed their peers.

You can force someone to sit in a chair and comply with directives, Neill thought, but you can’t force them to learn. People learn when they decide something is meaningful to them. What would have felt boring and oppressive when forced becomes important when chosen. As another schooling renegade, John Taylor Gatto once put it, “nothing important can ever really be boring.”

Back to “Where Do You Stand?” I didn’t invent the class; it’s been offered before, though I’ve put a few of my own touches on it. Our big, round table has definitely filled up since the start of the school year, as more kids have decided to drop in and see what we’re doing. The head of the cooperative tells me that some of the students rate it as their favorite class, which is certainly nice to hear.

So, I thought I’d share a little of what we do.

Here’s How it GoesIt begins when someone comes in with a hot topic in mind, or when I suggest a topic (which I do only when I’m met with blank stares and shrugs). It should be an issue about which someone can take a clear Yes/No stand. So far, we’ve covered topics such as: school dress codes; the ethics of animal product testing; the importance of foreign aid; whether the United States should engage in mass deportations; whether a college education should be free; whether the Bible should be taught in schools; and whether a Universal Basic Income is a good idea. Most of these topics were suggested by the kids.

Once we’ve agreed on a topic, we discuss it briefly, just to make sure everyone knows what we’re dealing with. Then I ask the students to get up out of their chairs and show, literally, where they stand. One corner of the room is for those who AGREE; one is for those who DISAGREE; another is for those who DON’T KNOW; and the fourth corner is for those who DON’T CARE (although we’ve yet to find a topic that puts anyone in that corner). We take a few minutes to go around the room and have each student talk about why they’ve chosen that corner and what they think about the issue. I may restate their position to make sure we all understand it; I may ask some clarifying questions. But I don’t challenge them or open the floor to discussion yet. That comes later.

Sometimes, kids will stand along the wall between the AGREE and DISAGREE corners—not quite wanting to commit to DON’T KNOW, but still uncertain about whether they agree or disagree. I always ask them why they’re standing there and why they think it’s different from DON’T KNOW. Most of the time, it’s not that they don’t know; it’s more that they’re going back and forth between the two, or they’re confused.

We go around the room and everyone states their case. Then everyone sits down again and pulls out their phones to do research on the topic. They don’t take notes unless they want to. They do cite sources, if only informally and as part of our discussion. Where kids go looking for information is critical, as we all know, and I want them to think about how they know what they know, or what they think they know.

Early in the year, we had discussions about things like logical fallacies, confirmation bias, and the importance of checking multiple sources. I try, gently, to remind them of these things—especially if there’s evidence of bad argumentation in their research or in the discussion.

Sometimes I ask students to research the topic generally, just to learn more about it. Sometimes I ask them to dig into their opinion for supporting details. Sometimes I encourage them to research the opposite of their opinion, to test and challenge what they think. Sometimes, as we did this week, I ask each of them to look into a different aspect of the issue, because it’s complex and has a lot of moving parts to it.

We take 10 or 15 minutes to do this research, which, admittedly, is far from exhaustive. But it gives the kids a taste of the universe of information out there, and (I hope) it encourages them to look further outside of class. And, to be honest, ten minutes of silent, focused research is a lot for these kids.

After they’ve had some time to dig, we go around the table and share what we’ve learned. I usually ask them where they found their information. Sometimes I push them to dig a little deeper, or I ask them if they’ve really understood what they’ve been reading off their phones. If their understanding is a little wobbly, I try to fill in some of the gaps. I try to be careful not to lecture. That’s not what the class is about.

Everyone says their piece. Then we open it up to general conversation. They’re a lively, curious, and (mostly) talkative bunch, so it’s always an interesting discussion. Sometimes it becomes a serious debate focused on the issue at hand. Sometimes it wanders off down unpredictable side streets and byways. I have no real agenda for any of this, so I’m comfortable letting the conversation go where it will. As before, when I notice gaps in background knowledge or context, I try to do a little backfilling for them.

At the end, everyone votes with their feet again, and we see if anyone has changed their mind. We go around the room, and everyone speaks briefly about why they’re changed their mind, or why they’ve decided to stand firm.

We have had classes when people have moved and shifted quite a bit (their feelings on the importance of foreign aid were once such time). We’ve had times where, no matter what has been said, people stick with their original opinions. That’s fine with me, as long as they’ve really thought about it.

And that’s the class.

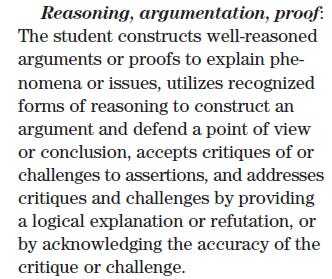

Here’s Why it MattersDavid Conley, director of the Center for Educational Policy Research at the University of Oregon, has long advocated for the importance of research and argumentation in preparing students for the rigors of college work. In his article, “Rethinking College Readiness,” he says:

He goes into more detail here:

One of my favorite books on argumentation, Oh, Yeah?!: Putting Argument to Work Both in School and Out, does a lovely job of systematizing the art of shaping an argument, boiling the process down to three steps:

What do you think?

Why do you think that’s true?

So what?

The “so what?” phrasing is a little aggressive, perhaps, but it’s a critical piece that often gets overlooked by English teachers. (I certainly never gave it the attention it deserved.) Everyone focuses on forming good thesis statements and supporting claims with evidence, but instruction often stops there, which is why so many essays have paragraphs of only a sentence or two, and why so many young writers agonize over what they’re supposed to do next.

The “so what?” piece is officially called the “warrant,” and it may be the most important part of an argument. It’s where the writer or speaker explains why the argument matters—why the reader should care. If X is the claim and Y is the evidence, Z, the warrant, explains why the truth of X is important and meaningful. Very often, it takes some investment of effort in that “warrant” section to really understand why you wanted to make the argument in the first place. The authors of Oh, Yeah?! provide some great examples of arguments where very young students unpack their thinking while trying to explain or justify a stance they’ve taken. Reading the transcript, you can almost see them reaching a little “aha moment” in the process of trying to explain their thinking.

I don’t ask the kids in my class to write essays or even paragraphs, because it’s not what the class is about. They have other opportunities throughout the day or week to focus on their writing, creative and otherwise. And to learn history and science content, if that’s what they’ve chosen to learn. I try to stay focused on the gig I was given: providing an opportunity for kids to talk about things that matter to them and to have their questions and opinions heard and respected by their peers and by an adult.

As I said, I know ten minutes of research isn’t enough for anyone to truly be able to think critically about an issue. I’ll cop to that. Critical thinking can’t happen in a vacuum. You can certainly think emotionally about a topic you know little about [gestures to social media generally], but you can’t think very critically about it. You need to know stuff, and this class is not heavy on the building of content knowledge.

My hope is that the class gives these kids a little taste of something that will develop into a bigger appetite: for questioning, for exploring and investigating, for supporting their opinions with evidence and arguments, and for being willing to challenge their preconceptions and question their biases.

Here’s Why Else it MattersThis is important beyond college readiness. We live in a particularly shouty and stupid age, where the volume and attitude of an argument seem to matter than its factual or rhetorical content. And while that’s entertaining in the gladiatorial arena of social media, it’s not conducive to building a sense of community or making decisions about how to live together. A civics class that replays the old, Schoolhouse Rock video about how a bill becomes a law is great, I guess. The whys and wherefores of our political system are fine and dandy. But we also need to teach kids how people from different backgrounds, with different and sometimes competing ideas and needs, work together to discuss the issues of the day and solve problems for themselves. Expressing your opinions, listening to your neighbors, evaluating the truth and value of what you hear, finding common ground where possible, making compromises where necessary—that’s the core stuff of self-rule, and if we lose that, it won’t really matter which sub-committee is responsible for which bill.

That’s where I stand.

Many thanks to the staff of the Raritan Learning Cooperative for doing the good and hard work of meeting the needs of non-traditional students. It’s a special place. It’s the kind of place where I started my teaching journey, and it’s been great to get back to those roots, even if only for an hour a week.

More thanks and all credit to the fabulous Heather, for pushing me to get away from my computer for an hour and do something useful in the world. And Happy Valentine’s Day!

February 7, 2025

[Re-post] The Country in My Head

It’s been quite a week.

I tried writing something. I worked on it every day—bits and pieces, here and there. I couldn’t make it come together. Every time I looked at it, I thought, “who the hell are you, to be saying any of this?” And also: “who cares?”

So, I trashed it.

Given what’s been going on in Washington, though, I thought I’d re-post this piece from November of 2023. It’s just about me, and what this country has meant to me—or, rather, what bits and pieces of art and culture have created meaning for me, throughout my life, around this idea of “America.”

I’ve been thinking about the things I carry.

I’m not a packrat or a hoarder, but there are ideas and pieces of culture that I hold close and seem not to want to part with, even when the larger culture announces that they’ve have hit their sell-by date and should be discarded. How I think about my country (what it is and what it should be) seems to be one of those things. It sometimes seems to be neither sufficiently progressive nor sufficiently conservative for other people’s tastes, neither sufficiently patriotic nor sufficiently critical. But whatever it is, it’s mine. And I’ve been thinking about where it all came from.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

As a card-carrying member of Generation Jones, I’ve always had a complicated relationship with patriotism. My parents were Depression babies and Eisenhower teens, coming into their own during the post-war, American-Century boom and settling down to raise children while Vietnam raged oversees and the Woodstock era exploded at home. Whatever they thought and felt about their country was never spoken out loud when I was a child, but it was certainly part of the air I breathed, in the same way that their Breakfast at Tiffany’s New York would never be mine to live in, but was always mine to dream about. I inherited their world, even as it was disappearing or changing.

Other than seeing hippies on the streets during our summer vacations, I was a pretty oblivious child. I did watch the Watergate hearings with my parents and I did understand, at least in general terms, that Something Was Terribly Wrong. In middle and high school, I paid only occasional attention to politics, looking backward at the 1960s more than I looked around at my 1970s, caring more about Monty Python and The Beatles than about our presidents. I got my current events news from Doonesbury comic strips. I was a casually liberal, suburban, New Yorker in the making. Doonesbury taught me, but so did movies like In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird and Inherit the Wind. I knew what boxes to check: Vietnam, bad; Watergate, bad; Nixon, bad; Reagan, bad. FDR, JFK, MLK? Good. Freedom of Speech? Excellent. The presidents up on Mount Rushmore? Classics. The American Dream? All for it.

As I moved into my college years during the Reagan Administration, the Boomers ahead of me moved into their thirties and beyond, many of them transforming into “Greed is Good” Yuppies. At every stage of their life, they had defined the larger culture, and in this moment, the culture was all Big Chill: solipsistic nostalgia, curdled idealism, and early-middle-aged excuse-making. All that cool and groovy peace and love stuff of their younger years—all the anti-war passion that I had relished—was it all just…nothing? If they, who had seemed to care so much, no longer believed in anything except themselves, what were we, their more sarcastic, younger siblings, supposed to believe?

And yet, the idealism never quite curdled for me. That base-layer of Eisenhower-y boosterism, or old Hollywood idealism, or middle-class, Jewish striving, all of that stayed with me, colored and enriched and informed by movies and music and books I had surrounded myself with as a child.

It was definitely a weird grab-bag of culture: Classical music, Broadway show tunes, Dixieland Jazz, Rock & Roll, and protest folk music; the film noir and WWII movies that I watched at home with my father, and the zonked-out, counter-culture films that I watched with my friends at our local art-house; James Thurber, but also Kurt Vonnegut; Hemingway and Fitzgerald, but also Hunter S. Thompson. I knew some of the art had been created to challenge and cancel what had come before it, but none of it did so in my mind. There was room for all of it, and all of it, together, told me who we were: My Country, ‘Tis of Thee, but also, Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.

We were allegedly a cynical and self-centered mini-generation—the wedge that led to Generation X—and yet, when we, as young, married couples in New York City, stood in stunned, silent shock after 9/11, we reached back to the patriotic songs we had learned in our childhood. We stood on the stoops of our Brooklyn brownstones, holding candles aloft at sunset to honor our fallen firefighters, and we sang those corny old songs, like It’s a Grand Old Flag, and, yes, My Country, ‘Tis of Thee. Because that’s what those songs were for; that’s why they had been taught to us, even in the midst of political and cultural upheaval—so that we could have them when we needed them. And on that day, when we needed them, we didn’t sing them mindlessly, or with uncomplicated feelings. But we sang them.

That was a whole generation ago (which blows my mind). What songs do the new, young marrieds in Brooklyn have stored away in their memories, to bring out when the storm clouds gather and the skies grow dark? What cultural artifacts have they put in their mental libraries to form a sense of home and country? Do they have what they’ll need to bind them together and keep them warm in the cold days—something heartfelt and hopeful? Or is it all just criticism and cynicism? I don’t know. Maybe it’s naïve and old-fashioned even to ask the question.

When I think about the bits of art and music and poetry that formed my sense of self and country, I wonder if any of it still means anything, or if it’s all just Eliot’s “heap of broken images,” leaving me, in late middle-age, with nothing but fear and a handful of dust. Is it all outdated, outmoded, and dead? Or are some of those fragments still vibrant and meaningful? If they’ve lost their kinetic energy, do they still have any potential locked inside? Could they be seeds holding something good—seemingly inert, but filled with the essence of life and able, if nurtured, to grow and flower again?

I don’t know. Maybe they’re just shards of useless, colored glass, or broken Hummel figurines of the kind that grandparents used to collect—old and musty and a little embarrassing, best swept up and thrown away. I suspect that’s exactly what they are to most people in my children’s generation. And that makes me sad, because there were things there that I valued.

I guess it’s not up to me to say what any of it will be worth. I’m a Hummel figurine, myself, or rapidly becoming one. The future will take what it needs and discard what it doesn’t need, as it always does.

Either way, here are a few shards from the world I inherited and grew up in—some of the bits and pieces that told me who we were, or wanted to be, or could be. It’s not a complete list, and it doesn’t paint a complete picture. It’s just some stuff from the warehouse that I’m airing out. Make of it what you will.

Henry David Thoreau

Because he thought new and uniquely American thoughts, and said things like:

I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward.

And also:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Because he taught us to rely on ourselves, not the dead hand of history, and that foolish consistency and conformity are death.

Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.

What I must do is all that concerns me, not what the people think.

Pete Seeger

I listened to him as a child because my mother loved him. I’m not sure I understood that they weren’t children’s songs, even though some of them were about children.

Alice’s Restaurant

Because it took place where I spent my summers, and I was there, oblivious but somewhere down the road. And because, when I finally came to read Thoreau and Emerson, I understood that what Arlo and his friends were doing was not unique or threatening, but was part of a our cultural heritage.

Langston Hughes

Because he understood what this country was at its worst, and he insisted that it live up to what it could be at its best.

O, let America be America again—

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where every man is free.

The land that’s mine—the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME—

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain,

Must bring back our mighty dream again.

Rhapsody in Blue

Because it’s a gorgeous collision of classical music, and jazz, and Jewish klezmer music, and New York traffic noises, and I can’t imagine what it must have been like to sit in an audience and hear it for the very first time, in that jazz generation that was inventing and hearing truly new and completely American music.

Appalachian Spring

I’m a Yankee by birth and by temperament, and this music feels like old home music—old America made new; simple gifts made grand.

Annie Dillard

Because when I first read her, I said, “Oh—it’s Thoreau again.” And because, like him, she found a way to marry quiet contemplation of the wild world with an urgency not to live a life of resignation or quiet desperation.

I would like to learn, or remember, how to live. I come to Hollins Pond not so much to learn how to live as, frankly, to forget about it. That is, I don't think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular--shall I suck warm blood, hold my tail high, walk with my footprints precisely over the prints of my hands?--but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical sense and the dignity of living without bias or motive. The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons. I would like to live as I should, as the weasel lives as he should. And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel's: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will.

The Magnificent Seven

Of all the many Westerns, this one—because it is one of my father’s treasured possessions, and because of these three moments in particular:

The farmers fight for themselves and take their town back.

The farmers fight for themselves and take their town back.

“You came back. Why? A man like you! Why?”

“You came back. Why? A man like you! Why?”

“The old man was right; only the farmers won. We lost. We’ll always lose.”

“The old man was right; only the farmers won. We lost. We’ll always lose.”The Great Gatsby

Because he is us, and we are him, and we can’t help believing in Daisy’s green light and the “fresh, green breast of the new world.”

Most of the big shore places were closed now and there were hardly any lights except the shadowy, moving glow of a ferryboat across the Sound. And as the moon rose higher the inessential houses began to melt away – until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh, green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees, the trees that had made way for Gatsby’s house, had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams; for a transitory enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.

Huckleberry Finn

Because Huck and Jim are together on their journey. They’re the people no one cares about or respects or values. But when they’re on that raft together, they’re free.

But I reckon I got to light out for the territory ahead of the rest, because Aunt Sally she's going to adopt me and sivilize me, and I can't stand it. I been there before.

Casablanca

Because sometimes, you do have to stick your neck out for somebody—and when you do, it makes everything better.

On the Road

Because, after all of the drama and sadness and craziness, there isn’t a world-weary shrug and a sigh of hopelessness—there’s this:

“But why think about that when all the golden lands ahead of you and all kinds of unforeseen events wait lurking to surprise you and make you glad you're alive to see?”

Walt Whitman

Because, finally, we are big and weird and crazy, goddamn it—individually and as a nation. We are large; we contain multitudes.

Failing to fetch me at first keep encouraged,

Missing me one place search another,

I stop somewhere waiting for you.

January 31, 2025

Book Stuff

Here in southeastern Pennsylvania, winter has actually felt like winter for a change, with bitter cold and stiff winds and a little bit of snow that seems not to be melting right away. Getting ready to walk the dog is a production. Dinners are best accompanied by a fire. I like it.

You know what goes well with a cold night and a warm fire? Of course you do; you read the subtitle at the top of the page. Did you know that I’ve written three mystery novels? Have you read any of them? Have you read all of them? They’re available at Amazon in paperback and Kindle formats. If you like my non-fiction writing here—and/or if you like mysteries—and/or if you like character-driven stories with a strong sense of place—perhaps you might enjoy my books.

All three of the mysteries follow a slacker jazz musician named Jordan Greenblatt (the least film-noir detective name imaginable, for the least noir-ish hero I was able to imagine), who lives in a low-key, artsy neighborhood of Atlanta, Georgia and who aspires to not much beyond hanging out on his porch with his bandmates, his college friends, and his wife. He supports his music habit by doing uninteresting, un-dangerous, investigative work…until he wades into waters that are way over his head.

The books are sequential, but I think (and have been told) that they work just find as stand-alone stories.

Here’s a little bit about each:

Jordan Greenblatt deals with life the way he deals with music—as a supporting player. Jordan is the bass guitar in the band of life—steady, solid, able to keep his cool, emotionally detached. Even as a private investigator, Jordan keeps a low profile. He takes pictures of adulterous husbands and helps local lawyers with medical malpractice cases, but he rarely breaks a sweat. And then, one steamy summer day, Jordan agrees to look into an old hit-and-run accident that took the life of a girl he knew in high school—a case in which he has a personal stake, for once in his life. The more he looks into the story, the more he is forced to question everyone’s assumptions. Bit by bit, he is dragged deeper and deeper into a mystery that he is not prepared to handle—a mystery that threatens to uncover many closely-guarded and long-protected secrets—including his own.

Jordan Greenblatt thought he had put diva drama and bad choices behind him a long time ago. But when a worried theater student comes to him for advice, it sets off a chain of events that leads Jordan back to his old college campus, working undercover to find a dangerously addictive new drug and the students or staff members who might be selling it. Leaving his regular life behind, Jordan tries to solve a puzzle and save a life without losing himself in the bargain. The longer he stays, the more he wonders if he can get the answers he needs and find his way back home.

Bill and Robinette Tomlinson think their prayers have been answered when they bring two foster children into their suburban Atlanta home. But when the birth mother is released from jail and fights to get her children back, the kids don’t just move away; they disappear. And so does the mother. And soon, so does Bill. Unsure what to do, Robinette turns for help to her college friend, Jordan Greenblatt, recently retired as a private investigator. What starts as a simple favor for a friend turns into a deadly search through small, South Georgia towns and the darkest recesses of the Internet. What kind of web has trapped Bill and the children—and can Jordan untangle it in time to save them?

I hope some of the above intrigues you enough to give one of the books a try. If you read one and like it, let me know!

January 24, 2025

When Schooling Becomes Nonsense

How Can We Support Those We Serve?

How Can We Support Those We Serve?Once upon a time, or so I’m told, publishers were able to make a single edition of a textbook and call it a day. Schools did whatever they wanted with that material, but they didn’t ask the publishers to re-create it to meet their local or individual needs.

Could that really be true? Who can even imagine it?

Those days are long gone. My entire professional life has been spent in a world of state standards and, at least for the more populous states, state-specific editions of textbooks and programs.

But even that world is disappearing. The idea that you can create a single version of a program to meet the needs of an entire state? That’s not good enough! Simply aligning to the grade level, academic standards is just the beginning of the challenge now. You also have to deal with local culture and local concerns and local fears. We can’t leave it up to the teachers to adapt materials on their own, to meet local needs. You can’t trust those people! Or maybe you can trust them, but you can’t ask them to do all that work.

It’s strange, but in some ways, addressing different needs between Massachusetts and Mississippi is actually less challenging than differentiating between Boston or Jackson, or any other city, and the smaller, more rural communities in either state. They have different values. Some of them are suspicious of “socialist government schools.” Some of them are suspicious of “bible-thumping activists.” All of them require materials to guide student learning.

But how can you create an American history program that emphasizes the long arc of the fight for civil rights—the struggle to extend the rights and blessings of freedom to marginalized minority groups—if every one of the words I just used is adored and celebrated by some of your clients, but loathed and feared by others? You can’t. What story are we supposed to tell? How many different stories can there be? One per customer?

Math is not much safer, by the way. Just two years ago, the state of Florida blasted new math programs offered by major publishers because they dared to talk about things like cooperation and collaboration in problem-solving, language which fairly stank, they felt, of Social and Emotional Learning, a thing which they did not want spoken of. Florida insisted on doing math in its own way.

These are complicated and angry times. How can we in the educational publishing and ed tech world navigate the needs and fears of our clients responsibly, without sacrificing what we know to be right?

Two StoriesAnecdote 1: I was leading a curriculum team that was developing assessment items for use in very religiously conservative schools. We had strict guidelines around acceptable content for reading passages and accompanying imagery: no women in the workplace; no boys and girls playing together; no exposed skin in pictures (beyond faces); no discussion of evolution or genetics; no discussion of the planets (because they were named after pagan gods)—things like that.

Did I love working under these constraints? I did not. But I tried to set some guidelines for myself, to feel like I had some agency and control. Avoid certain topics to show respect for their culture and values? That was fine with me; it was their school and their community, and they were paying for the product. But I drew the line at lying. I wasn’t going to say that the sun revolved around the earth, or that the earth was only a few thousand years old, or anything like that. I wasn’t going to present as fact and test student “knowledge” on anything I knew not to be true. Fortunately, nobody ever asked me to.

Anecdote 2: I was leading a product team and one of our reading programs, which published articles weekly across a wide range of subjects, was causing concern in some districts and foreign countries because of some of the topics our writing team selected. This required the writing team to create topic exclusion lists on a district-by-district basis, which was time-consuming and a bit depressing for a team that worked hard to find the widest possible variety of subjects to keep students engaged and interested.

When book-banning talk started heating up after COVID, we decided to put the power in the hand of district leaders instead of our central teams. We built a tool for administrators, where they could review lists of topics and suppress them at a school or district level. The writing team could publish whatever it wanted, and schools could decide what they wanted their student to see or avoid.

Am I proud of either of those actions of mine? They felt right at the time. They felt fair. But was I compromising…or surrendering?

Who Rules: The Clean PartWho gets to make decisions about what gets taught in schools?

Let’s start with the easy, fairly straightforward part. Starting at the top: the Federal Government (as of this writing) has no authority to dictate what is or isn’t taught. Period. Even when Common Core was being cursed and hissed at, there was no Federal iron hand telling anyone what to teach. The “national” standards were voluntary and adopted (or not) and adapted (or not) by states. There are some Federal rules around how schools are run, partly to enforce civil rights legislation and partly to guide title funding that goes out to states and to schools. But curriculum is not dictated by Washington.

Curriculum is sometimes dictated at the state level. States adopt learning standards to set grade-level goals for students, and some states also adopt textbooks or programs in support of those standards—sometimes a limited shopping list of blessed materials that schools can choose from; sometimes a particular, mandated text; sometimes nothing.

Curriculum is dictated to the largest extent by school districts, under the guidance of leaders hired by elected school boards. School and district leaders make the thousand and one decisions about what gets taught, when it should be taught, how it should be taught, and what’s for lunch. They are accountable to their superintendent, and the superintendent is accountable to the board, and the board is accountable to voters. If the curriculum is poorly aligned to the state’s standards, or test scores are a disaster, or there are complaints from parents, there is a direct chain of accountability.

Who Rules: The Messy PartSeen this way, parents are the true rulers of the school, through their elected representatives on school boards and the people those boards hire. If parents are unhappy, they can petition and protest. If they’re really unhappy, they can vote people out of office and demand a change. Parents must be heard and attended to.

But do schools do exactly what parents want, all the time? No. They can’t. This is not Baskin Robbins, with 31 flavors. This is not Cold Stone Creamery, where you can decide what fun stuff you want mixed into your ice cream. Every single customer doesn’t get exactly what he or she wants. As I’ve written previously, a district has to serve the parent community—and the rest of the tax-paying community—in the aggregate. It can’t cater to a thousand persnickety demands from a thousand persnickety parents, any more than the police department or the fire department or the guy who plows the streets can. Public schools are a public service—they make decisions for the good of the community as a whole.

The Balancing ActAh. But. “The community” is a tricky concept. I mentioned something above about parent and non-parent taxpayers. Those are two separate constituencies within a larger school community. They may share a great many desires and goals, but they may also differ on a number of things. The non-parent segment may be sick and tired of their school taxes going up every year, and cool, new programs being adopted every year, and, I don’t know, fancy new furniture being purchased every decade or so. They may not see any direct benefit in all of this spending, and they won’t until they try to sell their houses.

On the other hand, part of that non-parent constituency (or maybe split between parents and non-parents) might be a sub-community of local employers and business-owners, and perhaps they do see a direct benefit in the strength of the school program, in preparing young people to be better citizens, employees, and consumers.

AND…what are the borders of this community? In this day and age, don’t our young people belong to many communities all at once, all the time? Don’t they have access to, and draw values from, very far-flung people and groups?

Schools, families, neighbors, and religious institutions all work together (in theory) to raise young people into adulthood, steeped in the wisdom and values of the local community. But which community are they beholden to? Is it just the group that pays taxes? Maybe. Is it just the group that complains the loudest? Maybe.

Does a community have the right to have tight, cultural borders—to ignore the wider world and prescribe what children learn and what values they’re taught? Of course it does. Could a different community feel an obligation to prepare students to be part of a larger, more global culture? Of course it could. And those two communities could, conceivably, sit right next to each other. And both have the right to do as they please, and both require products and services to support their educational mission.

The Obligation

The ObligationI absolutely believe in vendors and publishers respecting and meeting the needs of local cultures, local communities, and local values. And yet, personally, I don’t like the idea of letting schools off the hook too easily. Learning is supposed to be more than simple recitation of what the last generation thought it knew. Learning isn’t supposed to be simple or comfortable, or reflexively responsive to whoever complains the most. Learning requires stretching some muscles—getting smarter and stronger. It shouldn’t be any more comfortable than a good workout at the gym. You’re meant to stress and stretch muscles so that they can grow and take more weight. And just like in the gym, you’re not supposed to be left untouched, undisturbed, unprovoked, unchallenged, unbothered, and unaffected by your education. That’s babysitting, not schooling. The point of babysitting is get kids to go to sleep. The point of schooling is to get them to wake up.

The DangerA government or a movement that wants to quiet dissent and minimize challenge can do so through brute force, but it can also do so, efficiently and with less shock, by controlling what gets said in public and what gets taught in school. And we don’t need to wait for Big Brother or black helicopters or jack-booted thugs to sweep down into our districts to change what is taught and how it is discussed. We’re already doing it to ourselves, through social media, intimidation of elected school boards, and self-censorship—through activist groups insisting that their values are the only values that need to be attended to, and that they, personally, define what “the community” is.

They do this to make educational programming safe for their kids (allegedly), but it doesn’t make schooling safe; it makes it clownish and stupid and of little actual value. When we censor ourselves to avoid offending anyone, we make school stupid. We ask children to sit in their hard chairs all day long to learn about the world, and then we withhold and confuse the facts of that world and hope they don’t notice or complain. If they swallow the slop without complaining, we call them Good Kids and reward them. But are we actually helping them understand the world they’re going to live in and work in and inherit?

Obfuscating the reality of racism during discussions of slavery makes the entire rest of American history make no sense. Or it makes it make the wrong kind of sense. They have to live in this country—with all of its echoes and resonances and lingering effects of something they haven’t been allowed to grapple with. How does that help them?

Pretending that great poems aren’t about sex or death or other Big Human Things makes the whole idea of poetry a confusing waste of time. Literature grapples with the big questions of life, and we ask kids to read that literature without actually grappling with those questions openly or honestly. What’s the point?

Math in life is about much more than memorizing times-tables. Taking the unpredictability and genuine problem-solving-ness out of math makes it hard for kids to understand why they will ever need it.

What is the point of any of it, if you’re not allowed to think about it, but are merely required to repeat it back to an adult the way you heard it?

Primum Non NocereI say, save the fairy tales for home and the dogmas for church, and let schools teach what they’re supposed to teach. Let teachers and students ask hard questions and think their way to hard answers. Let them think without panicking, every day, about what thoughts they might be having.

That’s easy for me to say, I guess. I’m an informed customer, being a former teacher and an Ed Biz guy. I know the teachers in my community. I trust their wisdom and their professionalism. Not everyone feels that way.

But however you feel, you have to acknowledge that education is what made the human race world-conqueringly successful as a species. We found a way to let an individual animal know more than they could ever personally experience or discover in a single lifetime. No other animal gets that, except through hard-wired instinct. We—just we—learned how to download the life experiences of our entire species and make use of it within each of our short, individual lifespans. Only we get to do that. Every child who starts school this year gets to start unwrapping the gift of thousands of years of knowledge, exploration, folly, confusion, revelation, and joy.

And what do we adults do? We undermine, obfuscate, and make inefficient that whole, glorious endeavor…to avoid offending our neighbors.

Shame on us.

January 17, 2025

The House I Grew Up In

Studies show that the act of recollection can reinforce a memory and enhance its stability. This is called Reconsolidation Theory. There’s also something called Levels of Processing Theory, which says that the depth at which information is processed can affect its retention in long-term memory. Think deeply and often about something and you’ll remember it more and longer. The less you think about a thing, deliberately and actively, the more likely it is that the sharp details of that memory will fade over time. This is the same mechanism that’s at work when you take a test—if it’s a rigorous test demanding real work from you: you’re asked to retrieve information from your memory and do something with it, which helps solidify the information in your memory and give you longer-term access to it. (See? It’s not just about getting a grade.)

When I first learned about this, I decided to spend a little time, every once in a while, (usually when I can’t fall asleep), thinking actively and deliberately about some old memory—a place or an event—to make it fresh again and help keep it alive. Obviously, there’s a danger to this: every time you remember something, you run the risk of augmenting, embellishing, and changing things here and there without quite realizing it. So, there’s a chance that while you’re solidifying an old memory, you may also be fictionalizing it.

I’ll take the risk.

Last week, while wide awake at two in the morning, I decided to remember everything I could about the house I grew up in from third grade through high school. I closed my eyes and took a slow and careful walk around the place, trying to remember as many details as I could.

Here is a daylight-hours recreation of my tour.

The HouseThe house I grew up in was on a street called Deerpath, in the East Hills section of Roslyn, Long Island. It was a nice, leafy suburb of New York City. No mini-mansions back when I was there—that era came later. No nine-car garages. Just solid houses, tidy lawns, and big, old trees. It wasn’t Fitzgerald’s East or West Egg, but it was no more than a ten-minute drive to those big, old shore houses—the ones that were still around. It’s funny—although Roslyn is situated right on Hempstead Harbor, which opens into Long Island Sound, I never thought about it as being a shore town. I have no memory of the water.

Our house sat between Squirrel Hill Road and Laurel Lane, both of which dead-ended at Deerpath and then led down steep hills to another road that paralleled ours. They were fun roads to ride your bicycle down, unless you were a complete idiot and decided to do it with your eyes closed and your arms outstretched, like…. someone I once knew.

No two houses on our street looked exactly alike, but they were all two-story, pre-war, colonial-style boxes. Our house was the boxiest and most traditional of the bunch, as I remember it: a big cube with a little garage pod sticking out of the right side and a matching patio pod sticking out of the left side for symmetry.

When we moved from The City to The Island and bought the house, it was painted white with black shutters. My father had it repainted a light brown, with dark red shutters, and he planted flower gardens along the street to break up the lawn a bit. The last time I drove by, years ago, the house had been returned to black and white, and all of the gardens had been ripped out, replaced with grass.

The ApproachWalking up the driveway on the right side of the house to get to the back door (which almost everybody did, unless you were delivering a package or coming to a party), you’d pass the garage and then have to open a long, wooden gate to get to the back. The gate wasn’t in two symmetrical sections with a break in the middle; it was one, long gate, that swung open from the extreme right side.

The garage opened to the back, facing a large square of pavement. My father kept his cars in the garage—his fancy, mid-life crisis sports cars—first a Lancia, then a Porsche, and then, finally, for some reason, a Buick Skyhawk. That was the car I helped drive when we left for the last time and moved to Atlanta. It was the only of his cars I ever drove.

I remember the Porsche well. The Lancia I only remember riding in once, when my father told me that my great-grandmother had died. All I really remember is seeing the huge tires of trucks as they pulled alongside that little, purple, toy of a car.

My mother had the mom-cars—the family cars—the cars I rode in more often and eventually learned to drive in. She parked them out on the blacktop, and I did my best to avoid dinging them whenever I shot baskets back there after school.

There was a backboard attached to the roof of the garage, behind which I always managed to get balls stuck. There was just enough space between the slanted roof and the bottom of the backboard to stick a broom handle in, to push balls loose—as long as the broom handle was long enough. Luckily, we had a large, outdoor, push-broom for leaves. One day, once I had gotten the ball loose, I just let the broom fall sideways out of my hand and arc down so that I could hear it make a satisfying smack on the ground. Unfortunately, my brother was walking up the driveway at the same time, invisible to me, and the broom smacked him in the head as soon as he appeared, making a much less satisfying sound and forcing my brother to get stitches.

Perpendicular to the garage door was a short stoop and a red Dutch door to the kitchen. I don’t remember us ever unlatching the top from the bottom—not once, in all the years we lived there. But I do remember putting my arm through one of the windowpanes in the door while slamming it in anger. Then it was my turn to get stitches.

Come On InWhen you entered the kitchen, there were drawers immediately to your right, including a big bread drawer that, when you pulled it open, had a white, sliding door along its top, to keep things inside fresh. That’s where after-school snacks lived, so that’s what I think of first when I think about coming into the kitchen through the back door. I can still taste one particularly awful, dry, fake-chocolatey snack in my memory—some block of highly processed cake and icing that only existed in the 1970s.

To the left, upon entering, was a tall pantry cupboard and then a small, round-top table with chairs. There was a little cut-out shelf above that table, for phone books and such things. To the right of that shelf was our yellow wall telephone, with an extra-long cord that let my mother putter around the kitchen at night while smoking and talking for hours.

Next to the phone was a white, swinging door that connected the kitchen to the dining room. And just past that door was our refrigerator. Facing the fridge was a low shelf, where an old, white radio sat, with an even older, yellowing, Peanuts comic strip taped to it, in which Lucy complained to her brother, Linus, about how it always rained whenever she wanted to do something. Why my mother treasured and kept that particular comic strip, I’ll never know. I don’t even know why we kept the radio. I can’t remember it ever being on.

Past that little shelf was the stove, and then, on the wall directly opposite the swinging door, the sink, with a window above it, and then those first drawers I mentioned, and now you’re back at the Dutch door where you started, with its small (very breakable) windows—the windows at which my friend, James, would always stand silently, nose to the glass, when he came to pick me up in the morning for our walk to school, waiting for me to notice him.

But we’re not leaving yet. Back into the kitchen. Go through the swinging door and you exit the kitchen into the dining room, which faced the street and had a big, bay window that, in our house, was always covered with hanging plants and blueish plant lights. I could always tell my friends which house to drop me at by pointing at the lights in those windows. No other house had them.

Our dining room held a big table, a sideboard, and an old, upright piano. There was an open archway leading into the foyer, with a matching archway facing it, leading into the living room.

The other way out of the kitchen, between the fridge and the low shelf with the radio, was a hallway leading to a half bathroom and then my bedroom, before turning left and leading into the foyer, with a doorway going down to the basement.

My RoomMy room had originally been a maid’s room, back in the higher-class days of the house. It was a tiny room. When we first moved in, my parents gave it to me as a study, which held a small desk and…not much else. There was no room for a bed and a desk—that’s how small it was. It was even too small for a normal door, so my parents found a floor-to-ceiling, saloon-type door that folded open and closed instead of swinging in or out. But the door they found was too wide for the non-standard doorway, so it never was able to close fully.

Attached to the doorframe, high up, was a pull-up exercise bar that I probably used all of three times. Why it was there and remained there, year after year, I don’t know. On the other hand, there’s all sorts of stuff sitting within view of me right now, in my home office, that I haven’t touched in years, from resistance bands to a banjo. So…there you go.

Hanging above my door was a woodcut of my name that an older cousin had made for me at some point. That sign was destroyed accidentally when my little brother, sitting on my father’s shoulders while being carried down the hall, flailed his arms around and knocked the thing down.

Eventually, when I begged for my own bedroom, my parents arranged for a young carpenter who was renting the house for the summer to build a loft bed for me, with a desk and dresser hanging under the loft. It was a very cool set-up. The bed was high enough that I could just barely sit up straight without hitting the ceiling. I had a wooden cube hanging on the wall to the right of the bed, to serve as a night-table. The dresser held up the head of the bed, and a ladder held up the foot. In between, a black desk shaped a bit like a paramecium was suspended from above, letting me sit facing out into the room. When I sat at the desk, I had a little bookshelf to my left, taking up half of the width of the bed, with the ladder taking up the rest. The whole scheme allowed me to have everything I needed, while taking up no larger a footprint than a twin bed.

Looking at the little bookshelf, what do I see? It was only big enough for paperbacks—there was another, larger bookshelf on the wall opposite my desk. I know I had three Ray Bradbury story collections on that little shelf—I can see the covers in my mind right now. Possibly there were some James Thurber books. Probably some Alistair MacLean novels, like The Guns of Navarone. I can’t remember what else was there, aside from an embarrassing motivational poster about dieting that featured an orangutan—about which, the less said, the better.

What else? I had a very small closet and a very small window, which let in very little light, mostly because it was blocked by an air conditioning unit, a little jade plant named Morris, and some oversized Doonesbury and Marx Brothers books.

The carpet in my room was a Tartan plaid, and, for some perverse reason, I decided that my walls had to match the carpet, alternating between red and yellow. It was hideous, but I guess I loved it. There was also a hideously green, but comfortable, chair to sit in. That’s right: alternating red and yellow walls, a Tartan plaid carpet, and a neon-green chair. It’s a very good thing that I didn’t come home to that room drunk. Well…not more than once, anyway, which led to a lecture from my father, the next morning—not about abstaining, but about drinking more carefully and strategically.

Moving AlongIn the hallway between my room and the foyer was the door to the basement. When we moved in, it was just a big, concrete-floored storeroom. My parents made a playroom in the center of the room and used classic, 1970s faux-wood paneling to create a walled-off storage area along one side and a large laundry room out of about a third of the rest of the space, which later also served as my father’s darkroom. They carpeted the play area, put in two twin beds to use as sofas, and loaded most of our toys and LEGOs and wooden blocks into cabinets. Later, there was a stereo that let me listen to my music without bothering my parents, and a TV where I could watch Monty Python by myself on Sunday nights.

The basement was also where my little brother spent hours pretending to be either or both of the Potvin brothers, “skating” across the carpet and scoring goal after goal for the Islanders. In classic Boy style, he was both athlete and announcer, doing great deeds and also narrating them for a TV audience, with volume and pitch increasing until he screamed, “GOAL!”

When you came back upstairs and turned right, or if you came into the house through the front door, you would find yourself in a small foyer. The foyer was our dog’s favorite part of the house, because it’s where the mail came in through a slot in the front door, and Lightning Dog loved grabbing letters from the slot and shaking or tearing them to pieces—a thing he also did with the hand of my friend, James (remember James?), when he foolishly reached into to the mail slot, thinking he might be able to find…a spare set of keys on the floor? I have no idea. It was a bad idea.

There was one piece of furniture in the foyer, to the right of the front door, that my parents called a “whatnot.” It was a knick-knack cabinet with several square shelves and elaborate, curlicue verticals connecting the shelves. I’ve never heard anyone else refer to a piece of furniture as a “whatnot,” but when I searched online for the term, just now, I discovered that it is, in fact, a real thing.

Standing at the front door and looking in, you’d face a stairway directly in front of you, with the hallway to the basement and my room to its right. Along that hallway was an antique settle bench. I don’t remember where it came from or why it was important, but it was always there, in that hallway alongside the staircase.

From the foyer, there was an archway to the living room to the left, and an archway to the dining room facing it on the right. The foyer and the walls going up the stairway were papered with a shiny, vinyl wallpaper that was white, with vaguely bamboo-ish yellow shapes. As weirdly 1970s as that seems, it was nothing compared to the black and neon wallpaper in the kids’ bathroom, upstairs, about which, more later.

The living room was spacious, with a bay window looking out onto the street and a large window opposite it, looking out into the backyard. That window was framed by floor-to-ceiling bookcases, which also held my parents’ turntable and stereo. Shelves below the big window held their collection of record albums: mostly classical and Sinatra, with soundtracks from the great Broadway shows they had seen as a young, married couple in 1960s Manhattan.

Walking into the living room, you’d see a long sofa on the near wall and a fireplace on the far wall. To the left of the fireplace was a door out to the porch, which screened or glassed-in depending on the season, with a flagstone patio beyond it. To the left of that porch door was a small, wheeled table with bottles of alcohol and mixers.

We had a big coffee table in front of the sofa—marble-topped, with a black wooden trim and a rattan shelf beneath it, on which all of our photo albums, including my parents’ wedding album, sat. I used to love pulling out those albums and looking at old pictures of us and older pictures of young grandparents and other family members. I guess kids just scroll on their phones now, but I feel like that loses something special—that fun of spreading big books out and flipping through pictures of ancient relatives you never knew, or people you knew only in their older forms. I remember looking at pictures of my great grandfather at my parents’ wedding—a man who was still alive well into my junior high school years—and being awestruck at the thought that a man could be “old” (a grandfather!) for so long.

If you looked up from the sofa, you’d see two chairs on either side of the fireplace—one wing-backed and one more square. Between the wing-backed chair and the bookshelf, on that far side of the room, was a long, wooden desk that held picture frames on top, with drawers containing all kinds of odds and ends from my parents’ life before children, including funny poems written by my mother for various birthdays and other events. Not for our birthdays, though—I never saw her write poems like that when I was growing up. They were relics from a younger, pre-suburban life.

UpstairsThe stairs up to the second floor went straight back from the front door to a landing and then turned to the right. The first room at the top of the stairs was ours, originally, and then just my brother’s. It was a big room, and I have almost no memory of living there with him, aside from putting horrific “Wacky Packages” stickers all over my dresser, which proved completely impossible to remove.

There was an open hallway that ran along the second floor, with a metal railing to keep you from falling down into the foyer. When I was young and my brother and I shared a bedroom, the hallway and railing made for a perfect spy perch for watching people coming and going when my parents would throw parties.

The hallway moved to the right, from our bedroom to my father’s study, which was carpeted in white shag, with a big, draftsman’s desk. I used to love hanging out there, when my father wasn’t using the room, because the carpet was really comfortable and because my father had a cassette tape player and recorder there, which I loved playing with, recording strange stories or pretending to be a radio broadcaster.