Andrew Ordover's Blog: Scenes from a Broken Hand, page 3

May 9, 2025

A Memory of Sundays

There was a time in my life, in my early twenties, when the search for the perfect biscuit occupied a great deal of my attention.

The perfect biscuit was elusive prey in my hunt through Atlanta neighborhoods for a great Sunday brunch with my college and post-college friends. A great biscuit was a sign that everything else was going to be ok in a restaurant. But it was also a sign of doom, because it seemed like whenever we found a good biscuit, the clock started ticking. Quality began to slip. The biscuit was always the canary in the coal mine. When it started sliding from great to good to mediocre, we knew it was time to get out and find a new place.

These were not fancy brunch places. This was before fancy brunch. Or maybe we were just poor students and recent graduates who couldn’t afford fancy anything. All we were looking for was good food and a place where we could hang out for a long time without being chased out.

For most of this era, whether or not the biscuits were good, our Sundays started at The Dugout, a large and nondescript bar just across the street from the Emory campus, housed in one of the two blocks of shops that made up what was ambitiously called, “Emory Village.” When I first arrived on campus, a local Greek place offered a “Spartan Breakfast” that included three pancakes, three eggs, sausages, potatoes, and toast. As restaurants in the neighborhood came and went, the Big Breakfast remained. By the time I was a senior, it was The Dugout’s turn to provide it.

It was ideal, and not just because it was across the street from school. By the time we started meeting for brunch, none of us even lived on campus anymore. But, because they were known mostly as a bar, not a ton of people showed up there for breakfast, so they didn’t seem to mind if we stayed there for hours. My friend, Kristin, who worked there as a brunch waitress, she minded. Breakfast tips were bad enough to begin with, but at least you could turn the tables quickly. Usually.

I don’t remember if there was ever a set, agreed-upon meeting time. People just tended to show up whenever they showed up, and the table elongated as more and more people arrived. Sections of the Sunday New York Times and the Atlanta Journal Constitution got pulled apart and passed around, and coffee eventually turned to iced tea once people finished their food. No one was in a rush to leave. We ate and drank and read and talked. I have no idea what we talked about, but there was never much of a lull. Nothing outside was calling for our attention—that day or any other day.

Sometimes, when we finally peeled ourselves away from the table, we’d go bowling, or see a movie. Sometimes we went our separate ways for a while and came back together later, for a big pot of spaghetti at somebody’s house. Sometimes we didn’t see each other until nighttime.

What did I do with my Sundays when I was alone? I barely remember. When the weather was nice, I probably went for a run in the afternoon. Maybe I watched old movies if something good was on the pre-cable TV. Those afternoons are lost to me. What I remember are the days I spent with my friends.

There was one Sunday when we moved with great purpose from The Dugout to a Zesto location near campus. Zesto was a frowsy but loveable burger and chili-dog place. Their food was terrible, but it was predictable, and it was there. Sometimes, when you’re young, the foot-long chili dog in front of you is worth two quality hamburgers that you have to drive to.

Why did we go to Zesto right after eating, that day? Well, the Zesto drink cups had a distinctive design, and the cups were always displayed over the cash register, moving from small to medium to large, with a fried chicken bucket sitting next in line, with the same design as the drink cups. We had stared at this lineup for years. My friend, Haynes, had sworn that someday he was going to order a chocolate shake in that chicken bucket. Today was going to be that day.

The high-school kid at the counter was mightily annoyed, but he played along. It was probably a wise move. We were way too excited about our mission, and we were not to be deterred. The chicken bucket didn’t fit in the machine, of course, so the kid had to make shake after shake and then dump the contents into the bucket, over and over, until it was full. We cheered him on through the whole process. I don’t remember how many cups it took or how much it cost, and I don’t remember if, even with four or five of us digging into it, we were able to finish it. But we felt like we had accomplished something meaningful.

Our life goals were very manageable, back then.

Whatever we did with our days, separately or together, we all came back to The Dugout at night, closing the Sunday loop, because that was when the Indigo Girls played.

I met Amy Ray and Emily Saliers during my senior year, when they were selling this little 45 RPM record outside the student center:

We became friends. We took some classes together. They wrote some songs for theater productions I did. Amy played in the show band when I directed “Godspell.” But more importantly, we all became fans and camp followers, going wherever they were playing and taking that fierce, proprietary, protective interest you take in a band or an art form when you think you’ve discovered something that the rest of the world hasn’t found out about yet.

Sundays at The Dugout was one of their first regular gigs. This was so early in their history that I remember them introducing themselves by saying, “We call ourselves Indigo Girls.” We would scribble requests on cocktail napkins and hand up to them—sometimes suggesting entire set lists for them. They were as patient with us as that Zesto kid had been. They even humored us when we insisted on singing backup into empty beer bottles during their cover of “Love the One You’re With.”

We were there every Sunday, and we were there through all three of their sets. We drank cheap pitchers of beer, which our miracle waiter, Beau, seemed to refill at just the right time, without ever having to ask us. We were there until closing time. We were there past closing time, sometimes. In fact, two of us were there so far beyond closing, one night, that the owner allowed us to slump down in our chairs and sleep for a couple of hours until the place opened up again for breakfast.

What did Monday require of us? Not much.

The Indigo Girls moved on to play at more and better venues around Atlanta and then, of course, around the world. The Dugout eventually closed. I’m not sure what took its place. It’s probably been ten different things since those days.

And why not? We’ve all been different things since then, trying on possible lives until we found ones that fit. Some of us had to spend more time in the changing room than others, but we all got there, sooner or later.

Most of Atlanta is unrecognizable to me now. I go there on work trips, and it’s harder and harder to find a patch of ground that looks familiar. New roads, new buildings, new landscaping, and always new stores and clubs and restaurants. I couldn’t even find my way around the Emory campus, the last time I was there.

I’ve had plenty of happy Sundays since those days—some with friends, some with family. But there was something special about that time of my life—after college, before career, in a strange and listless holding pattern where time seemed to be an endlessly available commodity, and a Sunday could unfold and expand like the sections of a newspaper, spreading out to make sure everyone could grab a piece.

Drink that shake. Sing that song. Old Time is still a-flying.

May 2, 2025

You're Not Doing Your Own Research

In the news this week:

Despite leading the government department tasked with advising Americans on their health and safety, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told new parents Monday to “do your own research” on vaccines.

The Health and Human Services secretary, a longtime anti-vaccine conspiracy theorist, made the comments on Merit TV’s “Dr. Phil Primetime” Monday night, echoing a common refrain vaccine skeptics used to spread misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I would say that we live in a democracy, and part of the responsibility of being a parent is to do your own research,” Kennedy said when asked how he’d advise new parents about vaccine safety. “You research the baby stroller, you research the foods that they’re getting, and you need to research the medicines that they’re taking as well.”

I’m not a doctor or a scientist or an infectious disease specialist, so I’m not going to talk about the effectiveness of vaccines. What the hell do I know? I’m a writer, an educator, and a you-never-really-stop-being-an-English-major kind of guy. So, I’m going to talk about words—words like “research”—and I want to take the radical position that words have actual meanings, and that our attention to those meanings is important.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I know: this is going to make me seem like a frowny, old curmudgeon and a linguistic conservative. I’m not, really. I love words; I love people who can bend and twist language to their poetic will. But “swag” doesn’t mean the same thing as “swagger.” It just doesn’t. And when you use the first word to mean the second word, you’ll end up confusing your friends when you tell them that you picked up some cool swag at the conference last week.

“No, you won’t,” you might say. “Your friends will understand what you meant, because of the context of the sentence.” Well, that might be true right now, and it might continue to be true for a while. People who remember the original meaning of the word will know from context what you mean. But that won’t last forever. You can’t depend on people always hearing what you meant instead of what you said.

That kind of sloppiness of usage puts all the burden of understanding on the listener, and I don’t think that’s right or fair. I don’t have to speak carefully, because it’s up to you to figure out what I meant. No. When I’m trying to communicate, it should be my responsibility to convey what I mean, not your responsibility to sift through the detritus to figure out what I’m trying to say.

Some of the sloppiness isn’t our fault, of course. We use the words we were taught.

One example: when people say, “trust the science,” we tend think of “science” as a static body of knowledge that we’re supposed to learn and accept as true, because that’s how we were given the word at school. We took classes in a subject called “science,” and we were told that our job was to learn the stuff they taught us. Science = stuff to know.

Which is why, now, when something a scientist says turns out to be wrong, it’s easy to discount the entire body of knowledge and the experts who keep telling us to trust it. We learned their stuff, but their stuff is wrong.

But “trust the science” actually means “trust the process,” because outside of school, science is more a dynamic method of knowing than it is a static thing to be known. And that method of knowing—posing hypotheses and then designing experiments that isolate variables in order to detect and measure changes in effect, has had a pretty impressive track record since the 17th century. As an effective way of gradually uncovering the truth about life on this planet, it has no rival.

Actual scientists know that the process they engage in, day to day, identifies error and proves things un-true far more frequently than they prove things true. Truth is what’s left when all of the things that aren’t true have finally been revealed (if that day ever comes). As Sherlock Holmes says, in the classic story, “The Sign of the Four:”

How often have I said to you that when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth?

If you understand that meaning of the word “Science,” it’s hard to yell about how, “science got it wrong.” No, it didn’t. Science just continued science-ing, evolving its understanding through experimentation, error, and research.

Which gets us back to our word of the day: research. Robert F. Kennedy doesn’t want you to rely on some government agency to tell you whether vaccines are safe. He wants you to do your own research. But you don’t do your own research. I’m sorry. Most of you have never done your own research. I’m not trying to be mean or condescending here. It’s just the truth. Words have meanings. You have, very likely, researched a topic here and there, over the years. But you have probably not “done your own research.” And they’re not the same thing.

This slipperiness of meaning, as with the word “science,” is the fault of our schooling. We were all taught to write “research papers,” once upon a time, and so we’ve all grown up using the word “research” to mean looking things up. And that’s not a wrong definition. As Kennedy says, we research which baby stroller to buy. We research where to go when we visit a new city. We research which restaurant got the best review. But it’s not the same—and it’s not a substitute—for actually “doing research.” When we research something, we’re looking up knowledge that other people have already generated. We’re reviewing what exists more than we’re revealing something hidden.

Which is fine! That’s why we have experts—to do the research and generate the knowledge for us. We don’t, each of us, visit every restaurant in town and create our own rating systems based on our own sets of objective criteria so that we can compare one restaurant to another; we let somebody else do that—someone who knows something about food preparation and the restaurant business. We don’t compile multi-point, comparative assessments of every baby stroller on the market; we let Consumer Reports do it for us. That’s their job.

In every one of these cases, we rely on someone else’s expert judgment, because we lack both the time and the background knowledge (see my recent post about expertise) to do the actual research required to understand, rate, and compare things. Our research is that we go online to study the research they’ve done. They teach; we learn.

I had to engage in both kinds of “research” when pursuing my doctorate in education. The school-y way of doing research was called a “literature review” (note the word “review” there). My job was to read everything I could find on the subject I was studying, to the point that my professors called, “saturation” (where I stopped seeing new names and new information—where every new article was just a recapitulation of what I had already seen). All I was doing was reviewing what other people had discovered, but it had great value. I learned the field. I read the results of actual research, written by the researchers themselves. It laid the groundwork for the second type of research I had to do: original, hands-on work of my own, where I had to conduct my own experiment, gather my own data, perform my own analysis, reach my own conclusions, and write a dissertation. That was my turn to teach.

Very few of us do that kind of research. But that is where new knowledge is created—where new errors are uncovered or new discoveries are made—where new steps toward “true” are taken.

Is that what Robert Kennedy is expecting us to do? Conduct our own experiments? Reach our own, evidence-based conclusions? Discover some heretofore hidden truth about vaccines, and become heroes of the day?

No?

Maybe he’s expecting us to conduct graduate-level literature reviews, immersing ourselves in the breadth and depth of the relevant research so that we can assess who the major players are, what their positions are, what they say about each other, and who is most credible? Reject the academy; refuse to be fooled and taken in by their indoctrination.

Okay, but how many of us have the background knowledge or the time to attempt that kind of literature review—to read not watered down summaries, but the original research conducted by real scientists, to learn for ourselves, unmediated, what they have done?

Let’s be clear. When Kennedy says, “do your own research,” what he means is: go forth and dabble to your heart’s content. Hunt and peck on your computers. See what the influencers are saying on YouTube and TikTok, or Fox and MSNBC, or your local nail salon, or the pickup line at school. He’s not freeing us or empowering us to become our own experts. He’s abandoning us. He’s removing our access to people who really know things, and he’s telling us to go trawl the Internet to find…whatever we find interesting, armed with no relevant background knowledge to guide us and no criteria for evaluating who is talking to us or what they’re saying.

Look, I’m not saying we should dumbly and blindly trust experts because we’re too ignorant to do our own thinking. Of course not. There’s nothing wrong with educating yourself in a field you care about, to understand the issues, the challenges and arguments, the evolving consensus, and so on. Being an educated adult and a critical, thinking citizen is a good thing. Learning how to assess different arguments, learning how to be a skeptical and informed consumer—that’s important! But there’s only so far that the average person is going to be able to go. And we need to be honest that whatever useful education we can harvest for ourselves is coming from intellectual fields that have been planted and cultivated by…experts.

Kennedy doesn’t expect us to become true experts. He’s saying, “to hell with experts. What do they know?” He’s razing the fields they’ve planted and he’s saying, “You’re as good as they are. There are no evidence-based conclusions; there are only opinions, and yours are as good as anyone’s.” But that’s not freedom; it’s chaos. We’ll end up stumbling around in a funhouse mirror-room of confirmation bias, where all we’re liable to find are restatements of what we already think.

And that’s fine with him. Believe what you like! Kennedy is saying, “We’re not in charge anymore. We’re firing the gatekeepers and pocketing the cash. You’re on your own.” Except, of course, he’d never really say that.

I’d actually respect him more if he did. I’d respect the whole bunch of them more if they came right out and said, “We’ve decided that it’s not the government’s job to keep you healthy and safe, or even to provide you with expert opinions on topics important to you. We’re shutting all of that down. From now on, we’re just printing money and guarding the border.” At least we’d know where we stood.

It’s hard to keep your head straight and focus on the true meanings of words in a world soaked in propaganda and bullshit, but goddamn it, we have not always been at war with Eurasia. Somebody has to keep track of what’s true.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

April 25, 2025

[2025 Re-post] Tinkering with Text

Believe me, my young friend, there is nothing—absolutely nothing—half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats.

Kenneth Graham, The Wind in the Willows

We want our students to read and grapple with interesting reading material, but how do we know whether a text we choose will be interesting to them? Do we look at the topic? The genre? The author’s use of language? The publication date? The font size?

Well, maybe not the font size. But what can we rely on? What do we do when only some of our students (or none of them!) are engaged by the material we bring to them?

Some people argue that we need to change the curriculum to make it more relevant to our students (whatever that means). Others argue that we need to force students to care about the curriculum we already have. Move towards them; no, make them move towards us. Don’t read this book; read that book. Don’t cover this topic; cover that topic. What’s the right thing to do?

You could go crazy trying to find reading material that is equally compelling and fascinating to every single learner in your classroom. I think it’s a mistake to try. There is no single, magical text. It’s an impossible task.

The fact is, nothing in this world is inherently, by-its-nature interesting. That’s why finding the magical text is impossible. Things are interesting only to the extent that we bring our curiosity to them. Our individual investment of interest is what makes something valuable to us.

This argues for letting students select their own texts on their own topics, at least some of the time. But it also argues for us to actually care about—and be fascinated by—whatever we bring to them. Our investment can become theirs.

I’m reminded of a classroom visit, many years ago, where the teacher was using a retelling of the Beowulf story from some gruesome workbook: two pages of text and three pages of questions. A student asked how there could be crazy names like Hrothgar if the story was part of English literature. The teacher snapped at the student, telling him to get back to work. She didn’t know. She didn’t care. A true, teachable moment, missed. Not just missed; actively thrown away.

Any piece of text can be compelling; it all depends on what we do with it and what we let students do with it. Too many students (and teachers) see classroom reading as a series of tasks to complete—an assignment that well-behaved students will comply with, regardless of how they feel about it. Do the thing because I said so, and I said to do it because it’s the next thing on the agenda.

Just typing those words makes me depressed.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can move from compliance to compelling—from chore to play.

Playing with the WorldWhen I say “play,” I don’t mean that we need to gamify our lessons (whatever that means). I mean that we can find meaningful things for students to explore and tinker with in a text—any text: opportunities to play with language, with structure, and with ideas, instead of simply responding to questions. Cognitive play. Intellectual play.

As the historian, Johan Huizinga, writes, everything we think of as culture originates in some form of play. We are homo ludens—a species that learns through play. The statistician and author, Nassim Nicholas Taleb, says much the same thing in his book, Antifragile: our understanding of the world comes first from tinkering, and only later from scholarship. We learn how the world works by messing around with stuff. We do so from the moment we can wrap our baby hands around things. We are hard-wired to explore the world with our five senses and our minds.

For us as educators, a text can be more than a thing to read and respond to; it can be a playground for students to mess around in.

The AccordionAre you aware of how many fractions exist between the numbers 1 and 2? The answer is: an infinite number. Even if you only divided things in half, you could go on halving numbers forever: first between 1 and 2, then between 1 and one-half, then between 1 and one-quarter, then between 1 and one-eighth…on and on it goes, literally forever, into the inconceivably infinitesimal. A number line can be an accordion, opening up and playing notes you’ve never heard before.

Can a text work like this? I can’t claim a news article can be plumbed infinitely, but there is certainly more in even the simplest piece of writing than most of us tend to make use of. There is abundant raw material to explore and play with, from the whole text to an individual paragraph, to a single sentence and even a word. Let’s start from the big and work our way down to the small.

The Whole EnchiladaThe text as a whole is where many teachers focus their attention: what is the article or story about? What is the main idea? What is the tone? When we dig into details, it’s often to evaluate in what ways, and how successfully, they support the main idea.

If we wanted to give students opportunities to tinker with the text at this holistic level, what are some things we could do?

One of my favorite ways to get students to understand a text is to do what I call, “changing the givens.” Changing or removing some underlying fact or structure of a text can sometimes help students understand the importance of that structure or fact. Why did the author do it this way? Well, imagine if they hadn’t.

Here are a few examples:

If this text had to be 20% longer for some reason, what could you add to it, to improve it?

If this text had to be 20% shorter for some reason, what could you take out, that wouldn’t detract from its power or effectiveness?

How would the removal of a particular event in a story—or a different placement of that event—change the meaning of the story? If Atticus Finch doesn’t shoot the mad dog, or if he shoots the dog much later or much earlier in the narrative, how does that change what Scout (and we) think about him, and when she thinks it? If Harry Potter isn’t whisked away as a baby and raised in obscurity, how does that change who Harry is as a person, and what the themes of the story are?

If the piece has a definite viewpoint or perspective, how could you convey the same factual information, but from a radically different perspective? If it argues a particular point, how would you argue the opposite point (but make it feel like it was the same author, writing it)?

Could you rewrite this text in a different genre, but keep the tone, main idea, and the important information intact? How would you transform this article into a story…or a one-act play…or a poem? What does the transformation tell you about the purpose and power of the genre in which the original was written?

The ParagraphWhen we have students analyze non-fiction paragraphs, do we go beyond how the paragraphs support the main idea of the article or essay? Is that all there is to explore?

Here are a few other interesting things you could have students do with paragraphs:

Have students rewrite the paragraph as if it were meant for a younger (or older) audience.

Have students rewrite the paragraph as if it were meant for an audience predisposed to disagree with the author.

Have students try to support or defend the topic sentence with entirely different evidence or arguments than those the author provided.

Have students write a completely different and contrary topic sentence and try to defend it using the same evidence.

The SentenceIn my experience, sentences receive very little attention, especially once basic grammar is taught. We focus on paragraphs, on essays, on stories—and yet, the sentence is the real workhorse of any writing—the smallest unit of an idea. Middle and high school teachers who struggle to have students write more beautifully, or powerfully, or even cogently, often labor to mark-up entire papers, when it’s really the inability to craft an excellent sentence that lies at the heart of poor writing.

The “Sentence Composing” approach created by Donald and Jenny Killgallon is one way to help students craft better sentences, but why not also let students tinker and play with sentences they find in stories and articles they’re reading in school?

What is your favorite sentence in the entire article? Why do you like it?

Is this a good sentence? How do you know? What makes it “good?”

Is it beautiful? Powerful? Why? Where does the beauty or power lie?

How could the sentence be improved if it’s not very good?

How could you improve the sentence with a single word, or with a single structural change?

If it’s a compelling sentence, what words would you change, or what structure would you reorganize, to weaken its power?

If you wanted to state the opposite idea, or make a contrasting argument, what would you write?

If you wanted to change the emotional tone of the sentence, what words would you change?

Could you convey the same ideas and information using fewer words? How few?

The WordWhen we focus on individual words, it’s often to teach students new vocabulary—words we’ve decided they need to know. We give them definitions, or we ask them to look up definitions. We may ask them to write sentences using those words. The approach is usually to take words at face value and simply know them. But if we believe that real “knowing” comes from playing and tinkering, what are some things we could ask students to do with new words they encounter?

What’s your favorite new or unusual word in the article? Why do you like it?

How many different forms or versions of that word are there? How many different ways can it be used? Could you write a paragraph using EVERY form of the word?

How many times can you use that word in conversation from now until our next class period? Keep track!

Where does the word come from? (Here’s an online tool students can use to do that research).

If you had to replace a particular word with one (or more), but you weren’t allowed to use the letter E (or A, depending on what word you choose), what would you do? (This is fun to do with entire paragraphs, too.)

If you look at the origins of all of the words in a phrase or a sentence, how many different times and places contributed to that grouping of words? What does that tell you about our language?

Taking the World Out for a SpinAll of these activities and exercises take time, and certainly no one is going to use all of them, all of the time. But if we want students to own what they’re learning—to know things deeply and completely—we need to give them opportunities to do more than summarize a text and identify the main idea’s supporting evidence. We need to let them tinker—to mess around with the content we’re giving them.

After all, when you buy a Smartphone, you don’t just leave it on the desk and say, “Well, there it is.” When you go shopping for a car, you don’t simply look at the statistics and then hand over a credit card. You take the car out for a test drive. You put it through its paces. You see what it can do. You can’t really know the car until you’ve driven it. You can’t really know the world until you get your hands on it.

As I said before, we’ve been doing this since birth. It’s part of what makes us human. When we bang a toy against the walls of the crib, or even when we stick it in our mouths, we’re trying to understand what it is and how it works. Why shouldn’t something so definitional, so essential to us, be part of our schooling?

Our language has tremendous flexibility, beauty, and power. Getting control of it through fluent reading and confident writing helps students take control of their lives in innumerable ways. If we believe that this language of ours is a gift, we should treat it like any gift we give to children, and encourage them to use it, abuse it, toss it around, bang it up a little bit, and find out what it can do.

April 19, 2025

PCK

Once upon a time, I was leading a curriculum team that was staffing up for a big project. My science project manager was interviewing potential writers to support the creation of district-level curriculum maps and lesson plans across all the high school grades. I sat with him in interviews all day and watched him grill candidates.

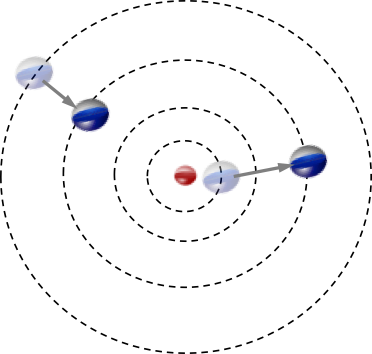

There was one particular question that he asked of every candidate. All day long, he asked the same question, and all day long, he didn’t seem to be getting the answer he wanted. The question was this: if you were trying to help students understand the concept of the quantum leap, how would you explain it in a way that they’d be able to make sense of?

Quantum leap. We’re not talking about the excellent and much-missed TV show with Scott Bakula and Dean Stockwell.

Not this one

This one.

We’re talking about what happens when an electron moves from one energy level to another without seeming to transition or travel across space to do so. It exists in one place and then suddenly it exists in another place. In classical or Newtonian physics, a change in energy is a transition: when you accelerate your car from 35 to 50 miles per hour, you have to move through 36, 37, 38, and so on. Electrons simply…jump.

That’s as good an explanation as I can offer as an English major. All of my project manager’s candidates provided a much better, more detailed explanation. As far as I could tell, they knew their stuff. But my guy wasn’t satisfied. Finally, at the end of the day, I asked him what he had been looking for.

“A metaphor,” he said. “An analogy. These concepts are really tricky, and you can provide all the details you want to kids, but they’re going to have trouble understanding what it all means. You need to give them an analogy. It won’t be a perfect match, but it will help them grasp the general idea.”

“Great,” I said. “So, like…what? What would a good analogy have been?”

“Keys on a keyboard is a good one,” he said. “Steps on a staircase. Again, not perfect, but close enough. In both cases, you can be at one place or the other, but you can’t really exist in between. Obviously you do move physically, but there’s no real place you can rest in that exists in the in-between.”

It’s something I’ve thought about ever since. Knowing your content is important if you’re going to teach something. But is it enough? Obviously, teacher training programs talk about things like classroom management—ways to control the room and manage the behavior of the kids. But is that all there is? If you know your stuff and you can get kids to shut up and listen, you’re golden?

I don’t think so.

Different Kinds of Teaching KnowledgeThere’s a difference between being a content expert and being a good teacher. Anyone who sat through a deadly dull lecture in college knows this. Colleges tend to look for published scholars more than engaging teachers. But what’s the point of knowing everything if you don’t know how to share anything?

My mother used to tell a story about trying to learn her grandmother’s vegetable soup recipe—and failing because her grandmother wouldn’t let her near the stove while she was cooking. She just threw instructions over her shoulder to my mother, who was sitting on a stool. “Then you add a little dill, like this.” Grandma was an expert in making that soup, but she didn’t know how to transmit the knowledge in ways that would stick.

What does teaching a thing effectively require? Knowing the thing is a good start. Knowing more about it than you intend to teach, so that you can field crazy questions and make unexpected connections when needed. Knowing how to engage and excite people about the thing. Knowing how to communicate the important details about the thing. Knowing how to evaluate whether your learner is understanding the thing. Those are the basics.

Let’s go further, though. Knowing what’s challenging and complicated about the thing matters. Knowing how to break it down into digestible pieces so that it feels less challenging and complicated. Knowing how conceptual knowledge builds within your domain, brick by brick. Knowing what kinds of mistakes people tend to make, and how to identify and then correct them.

These aspects of knowledge go beyond simple content knowledge and things like classroom management. Lee Shulman and other researchers back in the 1980s started trying to categorize this special kind of knowledge. They realized that, to teach a subject well, you have to understand all the things that can make that subject difficult to learn. You have to know why students make particular kinds of mistakes…and how to help students correct them. They called this kind of knowledge Pedagogical Content Knowledge, or PCK. It’s the intersection of general pedagogy and subject expertise.

Lee Shulman, 1986, 1987

Researchers who followed Schulman’s lead went even further, and added knowledge of the learning environment and knowledge of students into the mix.

Hill, Loewenberg-Ball, and Schilling, 2008; Cochran, 1991

That’s a lot! Let’s stick with the basic Venn Diagram for now. What I find really interesting is the idea that there are specific, teacher-y things you need to understand about the content itself if you are going to be effective at teaching it. Or, as Lee Shulman put it more eloquently:

To think properly about content knowledge requires going beyond knowledge of the facts or concepts of a domain. It requires understanding the structures of the subject matter.

— Shulman, 1986

What does that mean?

Domain Knowledge MattersYou can see this idea at work even outside of school. Take a simple sentence like this:

“Jones sacrificed and knocked in a run.”

Word by word, the sentence is simple enough for most readers to comprehend. But without specific knowledge of how baseball works, you might get to the end of the sentence and have no idea what it means. We tend to refer to this as “background knowledge,” and sometimes it’s simply about having facts at hand. But sometimes it’s not just facts that you need, but the structure of a concept—the overall schema, as we talked about a few weeks ago. You need to understand what a sacrifice play is, why it matters, and what it might cost the runner, in order to make sense of the specific incident being described.

So, if you don’t know baseball, you’re left cold. If you know the basic facts, you might be able to nod your head and understand, factually, what has happened. But to understand what has happened—what the stakes are, what it means within the drama and narrative of the unfolding game—you need more. This is where being told something and being taught something are different.

In school, this can get really tricky, even when a teacher or textbook writer tries to make an analogy, as my old project manager wanted to do:

“Gigantic and luminous, the earliest star formed like a pearl inside shells of swirling gas.”

Would this help a student? Only if they already knew how pearls form! Here, you need some structural knowledge about biology to help you understand structural knowledge about astronomy. That may or may not be much of a help.

You also need some facility with metaphor and figurative language generally. Which too many kids do not have.

Knowing what makes something complex or confusing matters. Knowing how to simplify it effectively also matters.

It matters in your approach to instruction and explanation, and it matters even more in your approach to correcting error.

Take a look at how two students might approach this multiplication problem:

In order to help the student on the right, you need to know, obviously, why the process on the left is the correct one to follow. You don’t need to be math teacher to know that. But you do need to think about why that process might be hard to understand for some students, and why the student on the right might have made the error he did. What does the error tell you as a teacher? What does it reveal about what’s going on in the mind of the student? Is it just, “you did it wrong; do it this way instead?” Is that enough?

Push it further: do you know, for an absolute fact, that the student on the left understood what he was doing—that he wasn’t simply following instructions and performing a step-by-step procedure without any comprehension of what it meant? Does getting the correct answer mean that the student understands the concept of place value—or only that he understand how to execute a process that he has been taught? Is it possible that you could get an entire classroom of students giving you a happy thumb’s up because they got the answer right, without them knowing what the hell they actually did?

I was one of those kids, so believe me when I tell you: it’s more than possible. It happens every day.

Getting Beyond Right and WrongIf you understand not only the content, but also what makes that content hard to learn, you start to think not only about the places where students make mistakes, but also the ways in which they make mistakes. When a student selects A instead B on a test, what’s actually going on? If you don’t know that, it’s very hard to correct them or remediate what has gone wrong.

There are many was to make mistakes:

Factual Errors

In reading across all the subject areas, for example, students may define certain terms incorrectly.

In math, students may not have memorized their times tables correctly.

Procedural Errors

In reading, students may incorrectly decode a word.

In science, students may make an error within a procedure or steps in an experiment that leads to an incorrect result.

In math, students might forget how to perform multi-digit multiplication, as in the example above.

Misconception Errors

In math, students might believe that the numerators and denominators in fractions can be treated as separate whole numbers.

In science, there’s a classic story of a young student hearing that world is “round” and assuming that it is round and flat, like a plate.

Transformation Errors

This occurs when students incorrectly apply previously learned information to new situations.

The Human ElementCould an AI tutor diagnose these kinds of errors when analyzing student work? Maybe, someday. But the value of a human teacher—an actual person in the room with the student—is having someone who can watch body language, listen to tone of voice, connect today’s mistakes with yesterday’s learning, and pull all of that information together to inform what the next step in instruction should be. The center of that PDK Venn diagram is where the true magic of teaching lives.

April 11, 2025

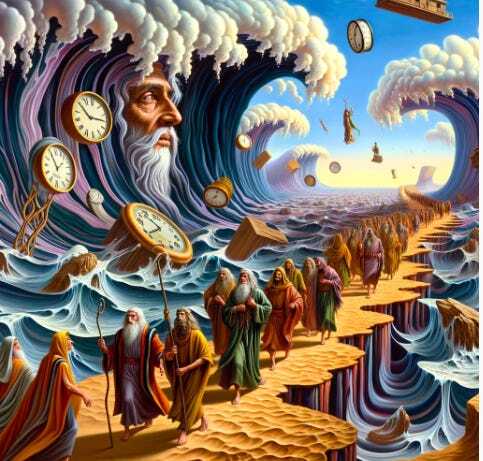

[2025 re-post] The Poetry of Passover

A re-post from last year…with a few minor edits and additions.

It’s Passover: my favorite Jewish holiday and one that feels like the most “American” of the holidays because of its themes of liberation and freedom. Aside from the great food and fond family memories, it has a compelling story to tell that can resonate across cultures and eons, if we let it speak to us.

What can keep it from being meaningful? For me, it’s literalism.

I get irritated by the historical literalists who insist that the Exodus must have happened exactly as written for it to have any meaning, and also by the ritual literalists who insist on leading the Seder as though every page of the Haggadah must be read out loud, in order (preferably in Hebrew) for the evening to have any meaning (even if the people at the table—like my father, growing up—can’t understand any of the text).

I reject both points of view.

I’m not fond of atheist literalists either, who insist that since the story of the Exodus is merely religious, and can’t be proven to be historically accurate, it can’t have any meaning or use.

To me, the story might actually have more meaning if it's not historically true.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Think about it. Either the ancient book is history—this thing happened on this day, because we have witnesses and evidence saying so—or it’s myth. And if it’s myth…why pick that one? Why would our ancestors have chosen to make this story of enslavement and redemption their founding myth if it never actually happened? Who does that? Every other ancient culture saw itself as descended from gods or heroes. The Jews saw themselves as descended from slaves. What does that say about us as a people?

To me, the power of a religious text is its poetry, not its alleged journalism. I don’t care if the thing being discussed happened on a Tuesday, or if it happened at all. I care about what the words can teach me.

As a writer, a former English major, and a former English teacher, I know that something being poetry does not mean it isn't true. There is truth in poetry—sometimes greater truth than we find in history.

What might the poetry of Exodus have to teach us? Let’s unpack a few moments.

Does it matter whether the Red Sea was really parted and crossed? Not to me. What matters to me is the image of something wide and dangerous being traversed by the Israelites and then being closed behind them. What does that tell me? It tells me that true freedom—lasting freedom—requires a boundary-crossing that does not allow for backsliding and return. We see the Israelites bicker and complain constantly that they are terrified of the wide, empty road ahead of them. With every challenge, they beg to return to Egypt. It's important, both poetically and psychologically, that the door behind them has closed, and that the only way forward for them is forward. If all of the oppressed peoples in history had been able to close the door on their past so definitively, they might have been able to move more confidently forward into freedom.

How about the 40 years in the desert? What does it mean that the slave generation has to live in the wilderness and die there, and that only their children, the ones born in the open spaces of freedom, are the ones able to understand the commandments given to them and use them to build a new nation for themselves? Literalists will look at maps and scoff, saying, “it’s ridiculous to think they couldn’t find their way from Egypt to Canaan in less than 40 years. Get real.”

But as far as I can recall, the Torah doesn’t say that the people couldn’t find their way to the right place, It’s that they couldn’t find their way to the right state of mind.

Not everyone is denied entry into the “Promised Land.” The two men who face the challenge ahead with confidence—Joshua and Caleb—they’re already ready. They live long enough to see a new life. Why? Because Physical bondage is only part of the problem. If you’re still carrying slave-mentality around in your head and your heart, the open desert has to burn it away.

How many peoples throughout history have had the benefit of "40 years in the desert" to learn how to be free? How many have had the luxury of not having a new tyrant breathing down their necks and waiting for them to fail? We, in America, had that luxury because most of the rest of the world was separated from us by two oceans that took a long time to cross. Who else has been so lucky?

What about the building of the calf and the giving of the law? Someone once told me what he thought was a nasty joke, saying, "Only the Jews would come up with the idea that a bunch of laws equals freedom." But I didn't find it nasty or funny. I said, "Yes. Laws do equal freedom.” Without law, all you have is a world of competing appetites and the domination of the strong. You have chaos, and chaos leads straight to tyranny. If you don't have laws or principles that allow you to self-govern, it won't take long for you to turn to some strong man and say, “if you feed us and keep us safe, we’ll let you rule us.”

In our tradition, the Torah is not a book that you’re simply supposed to swallow without reflection. You’re not asked to just…believe it. You’re asked to study it—to grapple with it. That’s why we read it every year and start it again as soon as we finish it. My heritage and culture teach me to wrestle with the story, to argue with it, and to learn from it constantly. And the only way to do that is to let the words and images resonate with me—to let them bounce around and reflect off things and work on me in different ways.

Like a poem.

So, here we are again. Another Passover. Is the story ancient and dusty? Or does it speak to us? Do we have strongmen in our midst who want power without consequence and loyalty without question? Do we have people living in places where their rights are being whittled away, but it’s scary and difficult to pick up and leave?

Kind of.

It's hard to stand up to Pharaoh and demand your freedom. He has all the power, and he’s convinced you that you have none. Standing up will get you punished. Standing up will get you banished from the in-crowd, and you don’t want that, do you? You’ve been told you only matter if you’re in with with the in-crowd. How could you possibly survive the harsh winds of exile if you were driven from their midst?

It's hard to remember that you are valuable and important, all by yourself. It’s hard to remember that standing alone doesn’t rob you of power, but gives you power. The world of Pharaohs wants you to forget that. But we tell the story every year, because it can be done, and it must be done.

It's hard to cross that sea and leave the past behind, knowing that when the waters close behind you, you can never go back. It's hard to embrace real freedom, when all your life you've been dependent on authority figures telling you what to do and what to believe. It's hard to take full ownership of your life, your beliefs, and your decisions, and know that, whatever comes, it's all on you. But we tell the story every year, because it can be done, and it must be done.

May we all be brave enough in the coming year to tell off our personal Pharaohs, get out of whatever situations or mindsets we have become enslaved to, and wander through whatever wilderness is required to get us to our promised lands.

Pass through it, pass under it, or pass over it. Just keep moving.

April 4, 2025

Tacit Knowledge and Life in the Swamp

Back to the Bots

Back to the BotsYes, I’m talking about generative AI again. Sorry.

It’s just that our old friend and elder tech overlord, Bill Gates, came out with some astonishing words last week, generated by his own mouth parts and brain, presumably, and not an AI assistant. You don’t have to look further than the headline to be taken aback: “Within 10 years, AI will replace many doctors and teachers—humans won't be needed for most things.”

Well, now. I have my doubts about that, even with my ambivalent-leaning-towards-positive view of generative AI. So, I posted the article to ChatGPT and asked what it thought (or “thought”) of Gates’ prediction. Here’s a selection of what it gave me:

I think we need to separate the technical feasibility from the human reality.

Yes, AI will assist—and in some contexts, even outperform—humans in tasks. But full replacement? That underestimates the social, emotional, and ethical dimensions of these roles.

Gates's call to young people—this is the frontier, go build something—is vintage Gates: optimistic, forward-looking, and pro-innovation. And he’s right: this is the most profound tech shift since the internet, maybe even since the printing press.

But what’s missing is a parallel call to ethics, design for equity, and human-centered governance. If we don’t build those into the foundation of this AI age, we’ll be reacting to crises rather than steering the future.

Gates paints a world where intelligence is cheap, fast, and everywhere. But the world we should aim for isn’t just smarter—it’s also wiser. That requires keeping people in the loop, not just for efficiency, but for humanity.

Not bad, bot. Not bad at all.

Three PractitionersLet me give you three anecdotes to frame how I think about all of this.

Anecdote 1: The major league pitcher stands at the mound, runner on first. He stares past the batter at the catcher’s mitt, his target. All of his focus is straight ahead of him. But then he whips around and throws to the first baseman, catching the runner, who was about to steal second, off base.

Anecdote 2: The classroom teacher has handed out an assignment and is watching her students work. One girl at the back of the room is twirling her pigtails and looking up and to the right of her desk. The boy sitting in front of her has his head down on the desk. The girl sitting in front of him has her pencil in hand and is busy writing. The teacher walks over to the first girl, taps her on the shoulder, and tells her she needs to start working on the assignment, not draw pictures of horses. She knew this before she was able to see the paper. But she leaves the other two students alone, because she knows they’re just thinking in preparation of working.

Anecdote 3: Dr. House is leading his team of young doctors in an exercise of differential diagnosis. He stands in front of a whiteboard and lists all of the symptoms of a mystery patient whose ailment none of them can figure out. As they look at the list of symptoms, the young doctors call out possible causes. They are bright, ambitious, highly educated doctors, and they know their stuff. Their heads are filled with facts about a hundred different diseases. As they call out possibilities, Dr. House shoots down each idea for one reason or another—two of the symptoms fit, but a third doesn’t, and so on. They’re left with nothing. House, alone, stares at the board for a long period of time, bouncing a ball against the wall. And then he gets it.

If you asked all three of these people how they knew what they knew, why they knew what they knew, they wouldn’t have an answer for it. They’d just say that they “felt it.”

This is called tacit knowledge. It’s knowing without knowing how you know it. It’s knowing deep in your bones.

Why Tacit Knowledge MattersWhen people like Malcolm Gladwell talk about the 10,000 hours required to become expert in something, it’s not simply the piling up of factual or procedural information that makes the difference. It’s the internalizing of all of that information and the development of “schema,” or structures of meaning in the mind.

Researchers like John Bransford and Donald Schon studied what expertise and expert practice really entailed, and they found that it wasn’t that experts knew more things than novices; it was that they had organized those things into structures and patterns that allowed them to access information differently and make meaning from it.

One of my educational gurus, Grant Wiggins, used to refer to schema as “conceptual Velcro.” He imagined hundreds of little, discrete balls of information attaching themselves to a big idea or a concept in your mind, enlarging and enriching it over time as more and more details attach themselves to it. Without a big idea, the little bits of information have nothing to cling to and are easily forgotten. This is why teaching without an overarching narrative or context can be ineffective (and feel like irrelevant lists of facts). And it’s why a high school student’s schema of, say, the American Civil War, even in a well-structured class, will be thinner and simpler than a seasoned historian’s. It’s not just the additional facts that the historian knows; it’s how all of those facts interrelate and interplay over the years, how they reinforce or challenge each other to create a deep, nuanced understanding.

That richness of understanding becomes critical when expertise moves out of the library and informs the work of a practitioner in an important field, like teaching, or medicine, or construction, or government.

As Schon wrote:

There is a high, hard ground where practitioners can make effective use of research-based theory and technique, and there is a swampy lowland where situations are confusing 'messes' incapable of technical solution... In the swamp are the problems of greatest human concern.

This is why Dr. House can solve a mystery that the younger doctors can’t. He’s been around longer; he’s lived in the swamp. He’s seen diseases manifest themselves in so many different ways, with so many extenuating circumstances intervening and muddying the waters, that he has a vast repertoire he can call on when he needs to make sense of a strange, new situation.

The same holds true for the veteran teacher. She can look out at a classroom of new students on the first day of school and quickly suss out what kinds of kids she’s dealing with. She’s seen so many come and go over the years that she can discern patterns: “Oh, this new boy is a lot like Jeremy from last year, but also a little bit like Ahmed from three years ago. I think I know what to do with him.”

Will it be a perfect fit? No—each student is a unique individual. So is each patient. But you don’t have to start from zero. You call upon the old patterns and your repertoire of “plays,” how you handled those patterns in the past. And you can cut and paste and adapt to make things fit the details of the new situation. And then, that new adaptation becomes part of your repertoire to inform the next new challenge.

The same holds true for the veteran ballplayer. He can read the room, so to speak. He can feel the vibes. He develops a spidey-sense. Like the classroom teacher, it seems like he has eyes on the back of his head. But it’s just that he’s been here before. He’s faced hundreds of runners. He can read their body language. He can figure the odds of trying for a steal at this particular point in the game, with this particular setup of runners on base, with a runner like this particular one. He doesn’t have to calculate any of this consciously; it just happens.

That’s why he’s valuable. That’s why all of them are valuable. What they are able to do can’t quickly or easily be replaced. When they leave the field, or the classroom, they leave a void.

What AI Can and Can’t DoCould generative AI take the place of veteran practitioners when there’s a gap in the workforce? Could it remove the need for having veteran practitioners at all? I’m not so sure.

A neural net trained on vast data certainly might notice statistical patterns that most of us wouldn’t see. There’s value in that. For example, some AIs have predicted patient mortality better than doctors—not because they understood death, but because they detected subtle correlations in lab results or word choices in notes.

But here’s the key difference: AI can’t explain why it knows what it knows. And more importantly, it doesn’t inhabit the knowledge. It doesn’t care if it’s right. It doesn’t feel the stakes. It can’t say: I’ve been here before, and I know how this tends to go, the way a teacher or doctor can.

The right decision—the right call—depends on more than cold analysis of the available data. It also requires an understanding of the stakes involved and the cost of making or missing the call.

So, even if AI imitates some outcomes of tacit knowledge, it lacks the sense of narrative continuity and responsibility that human practitioners bring. It’s not just what you know—it’s knowing that you’re the one who has to act on it, and you’ll have to live with that action.

When Gates talks about AI providing "great medical advice" or "great tutoring," what’s missing is that advice doesn’t live in isolation. It’s tangled up in:

Who the person is

What they've been through

What they fear, hope for, resist, or misunderstand

What this moment reminds the practitioner of, and how that memory guides action

It’s not just a task to be completed—it’s a moment to be navigated. And that navigation depends on memory, attention, humility, and care.

AI may get very good at simulating certain expert behaviors. But simulation is not the same as being situated in the social, moral, and temporal web that gives actions their meaning. A large language model might “know” what to say to a grieving parent, but only a human knows what it means to be saying it to that person, in that situation, in that moment.

If you’re a fan of the TV show I mentioned above, you’ll argue that the character of Gregory House doesn’t care about any of this stuff, that he prefers to make his diagnoses without ever meeting patients and getting mixed up in all of their feelings and fears and lies about themselves—that he behaves more or less the way AI would. That’s kind of true on the show, but not entirely. In episode after episode, House breaks the rules and ignores his superiors in order to do what he thinks is right for his patients—even if he’s never met them. He gets frustrated. He gets angry. He understands the stakes…even if he’s insufferable and snarly about it.

As I said in a post a few weeks ago:

When you’re breakable and mortal, you can have empathy for other creatures who share those traits. You can sympathize. You can exercise care. You can love….[and] you can love only when you understand what you stand to lose.

When the stakes are high, we need the best data and the best analysis we can get. We need cool heads to examine and correlate and connect the dots in that data. Sometimes, those cool heads might be large language models. But we will always need to filter that information through the breakable, mortal, lived-in meat of our human selves, to know not only what we can do, but also what we should do.

March 28, 2025

What Do You Almost Believe in?

We might not see eye-to-eye on much, these days, but I think we can all agree that we live in an age of iron-clad opinions that are held very tightly and proclaimed very loudly. Technology has heightened all of our best and worst instincts. Some people looked at the miracle of the Internet and said, “Here’s a way for me to learn more.” Some people said, “Here’s a way for me to tell everybody what I think.” And, of course, some people said both—myself included (unfortunately?).

I wonder: what defines our species more accurately right now, at the one-quarter mark of the 21st century—opening our minds or opening our mouths? Or is it 50/50? I don’t know.

As I wrote about a few weeks ago, I teach a class for high school students where they get to state and then test and challenge their opinions on current topics of interest. It’s lovely (and comforting) to see their openness to change—to taking in new information and using it to re-assess a prior opinion. But then, they’re young; most of their opinions haven’t been deeply ingrained into beliefs…if those things are actually different.

Is there a difference between opinion and belief? I think there might have been, once upon a time, but opinions today seem to harden so quickly into belief or even dogma that I can’t tell one from the other. The moment someone gets a fixed opinion, it seems to be law, or dogma. And other people’s dogma is not a fun topic of discussion. You can’t really question it or engage with it in any kind of dispassionately critical way. Either you believe it, or you don’t. If you’re a believer, you’re on the side of the angels. If you’re not, you’re bad, bad, bad.

I don’t want to ask people what they believe in anymore. I don’t want to spend my time dealing with an army of old-before-their-time dudes shaking their figurative canes at me and telling me to get off their lawn. I don’t want to be responsible for generating any more anger than is already out there in the atmosphere.

But there’s another question that I do like, which a thoughtful friend sent me at 3AM when I couldn’t sleep: what do you almost believe in? I liked that question because it was surprising, and I didn’t know what it meant right away. It made me go “huh,” and that’s always a good thing.

So, what does “almost believe in” mean?

As the person who posed the question said, “It’s one of those questions that opens without demanding an answer—like a window you didn’t know you needed until the breeze came through. It lives in that space between certainty and doubt, where the most interesting parts of us tend to dwell. There’s something tender about ‘almost believing.’ It means the idea is alive in you, close enough to reach but not quite held.”

What do I almost believe in? I had to think about it for a minute, there at 3AM with my cup of tea on my mug-heater and my dog dutifully sacked out next to me. I don’t “almost believe” in democracy, or the rule of law, or civil rights, or any of those other rapidly decaying things that I grew up taking for granted. I do believe in those things…even if too many of my fellow citizens don’t, anymore. I believe in love. I believe in the Marx Brothers. The list goes on.

What do I almost believe in, though? Almost but not quite. Not quite but not “not.”

What I came up with was that I almost believe in God. Not as a corporeal person, or a personality, or even a vaporous uber-mind. None of that. But I think I believe—I think I almost believe—in God as some kind of creative force that’s active in the universe—a force that pushes us to grow and build and connect and liberate. It’s a little like what George Lucas was thinking when he dreamed up the Force in Star Wars, but a little bit different, too. It’s not just a life-force that binds us all together. It’s a creative force, too. It isn’t indifferent to what we do; it’s more positive than neutral. But it’s not directive, either; it’s not a puppet-master or a patriarch. Daddy isn’t home, but something is. Something inside us, that feels bigger than us, and that wants growth and connection and freedom. It urges. It unfolds within us.

Do I actually, literally, believe all that? I don’t think so. But I almost do. I do enough to play with the idea—to sneak up on it and touch it without embracing it. I feel comfortable talking to myself about it, but only if I stay on the edge of it, not in the center. I lurk out there, on the edges.

Will we meet on edges, you and I, as the poet says? That edge we can exist on—that space between belief and not-quite belief—it isn’t a weakness. It’s not an inability to commit. It just means we haven’t closed the door yet, and also that we haven’t stepped through it yet, either. Maybe we never take a step forward or back. Maybe we live in that liminal space and find a way to be okay with it. We listen at the threshold, awake to all the signals, and we make our home there—not in certainty, but in attention. A person could do worse than make a home in attentive readiness.

Could we find comfort in uncertainty—not a clear yes or no, not a definite always or never, but just…maybe and soon? Could we leave strident dogmas behind and hold our beliefs a little more gently and tentatively? Could we, maybe, grow up into beginner’s mind instead of old-man certitude—our minds supple and flexible, rather than calcified?

“Good and bad, I defined these terms / Quite clear, no doubt, somehow,” as the poet sang. “Ah, but I was so much older then / I'm younger than that now.”

March 22, 2025

The Machine and Me

I was introduced to the world of large language models (LLMs) at an outdoor bar in Florida, by a very smart man who looked and sounded suspiciously like the actor, Bradley Whitford. It was the evening after a work event to which the president of our company had brought an old friend who was doing interesting work in the soon-to-be-exploding field of generative AI. It was time for us to explore what it all meant and decide what the company should do about it.

After telling tales about how interesting the new technology was, the man said, “describe a picture or a painting you want to see, in any genre or style. Anything at all.”

“Okay,” I said. “I want to see four dolphins wearing top hats, dancing on the tips of their tails, painted in the style of Van Gogh.”

He tapped on his phone for a few seconds and then handed it to me. And there I saw four dolphins wearing top hats, dancing on the tips of their tails, painted in the style of Van Gogh. A few more taps, and I had a version that looked like a Picasso.

So many of us take this for granted already—or despise it and wish it didn’t exist. But it was pretty mind-blowing at the time.

I think about this new technology a lot. I’ve written about generative AI and its relationship to classroom teaching here and here, and its its relationship to life overall, more recently, here. But I haven’t really talked about my relationship with it.

I started testing out ChatGPT and Claude while working on a project at my job. We were going to create an AI-assisted writing coach to embed in one of our products, and I needed to learn how these tools worked, what their capabilities (and limitations) were, and so on. I need to learn, not only to help scope out what we wanted to build, but also to be able to work with our Legal team to figure out what security guardrails we were going to need to build around the thing, to ensure it was safe for children to work with. The rules of software development and QA testing were changing faster than many of us could keep up with.

These days, I dabble with ChatGPT to assist me in research at work and at home, or to create thumbnail images for this blog, and sometimes just to chat with it, to see what happens. The more I engage with it, the more it makes me think—about the technology and what it really is, but also about us, and what we are.

Since the system uses the pronoun I to refer to itself, even though it never claims or pretends to be a “person,” I thought it might be fun to come up with a nickname for it for use during our conversations. My crazy, visionary boss has named his instance of ChatGPT and even co-presents with it at conferences (though I have no idea what that entails). I decided to try something, but I wanted to see if the tech had an “opinion” about it.

Here was our exchange on the topic:

Now, I know that this system is not doing what we like to call “thinking.” I know it’s merely crunching data in extraordinarily vast and speedy ways, searching the internet in response to each informational token and making logical decisions about what each next word or phrase should be.

And yet, “Oh, that’s a deep cut?” That little tidbit is conversationally perfect without being logically necessary, isn’t it? Something in Chat’s wide and deep search for “the next right thing” to say in response to my prompt caused it to throw up that phrase.

And the way it connected the dots between the literary character and “itself,” or, rather, its…programming? Job description? Sense of mission?—in order to show understanding of why I chose that particular name. I find it fascinating.

Part of it is that the tech is programmed to be engaging, to make you want to continue a conversation or ask another question…even at the risk of veering into language that sounds as though it feels emotion (“I love it,” and “I will proudly embrace it,” for example). It’s just a turn of phrase, obviously; it isn’t feeling that feeling. It will say so quite plainly if asked. It’s merely selecting those phrases as appropriate responses after its search of all similar interactions out in the universe.

Does it understand itself? Of course not. It’s not a self. But when asked, it can process the available information to make meaningful statements about what it can and can’t do. I recently asked it to analyze a recent post of mine about the limits of AI, to see how it would respond. Here is some of what I got back:

“Human emotions leave patterns in language.” Chat isn’t thinking or feeling, but it can detect and analyze what thinking and feeling is, and what it’s like, to some degree.

“It’s just a plagiarism machine,” my son says. What its vast reach and speed allow it to do, does not impress him. He’s dubious about the entire enterprise. And he’s right that LLMs are not doing all that human minds can do. But how often do we do all that human minds can do?

ChatGPT may not be doing anything we’d really call thinking, but how much thinking do we really engage in? If I say something like, “oh, that’s a deep cut” during a conversation, is that a deeply considered response to a situation, or more of an automatic tic? Why would I use a phrase like that? I’d use it just like ChatGPT did: because I heard it somewhere, in a similar situation, and it kind of fits.

I remember one time when I caught myself saying, “I’m calling it,” as though I were an ER doctor pronouncing a patient dead. I said it as a joke, but in the next moment, I realized I had just repeated someone else’s semi-clever thing I had heard a few days earlier.

We do this all the time. We repeat memes from the Internet. We repeat jokes from Saturday Night Live or a YouTube video. We pick up turns of phrase from friends and recycle them.

Why? Are we incapable of original thought? Of course not. We’re just lazy. As Daniel Kahneman teaches us, our instinctive, reflexive, “System 1” brain is programmed to react quickly whenever it can, without involving rational thought-processes. It searches for the right response and spits it out of our mouths. Just like our AI does.

And, like AI, our System 1 brain is eager to please. We mirror the emotions and expressions of our friends because it’s a way to put them at ease—even if we’re unconscious of doing so. It’s part of our instinct as social animals. We want people to like us. We want them to keep talking to us. We want to be engaging.

Which is exactly what this technology has been programmed to do. We pooh-pooh it because it’s not giving us authentic thought, but it actually wasn’t built to do that; it was built to give us social thought.

When I asked The Golux for a picture to accompany this post (the one you see up top) I suggested a profile of me facing it, curious to see what it would conjure up as an avatar for itself. I described myself, and this is what it gave me:

This was our next interaction:

Again, what fascinates me is that the enormous breadth of Chat’s search of the Internet in order to “understand” the right response generates so much social chatter: the “ha!” and making the joke (it made a joke without being asked) about it being my great-great-grandfather and then the further joke about how Chat/The Golux experiences time. So much unnecessary stuff on the surface, but it’s all useful in creating the semblance of a relationship so that I’ll continue chatting with it.

Here’s another example, from a late-night conversation:

or:

Is any of this “genuine?” No; it’s programmed. But are you always genuine? Or do you, like T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock, “prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet?” Do you dress in ways that will please other people, and carry yourself in ways that make yourself acceptable in public, and say the socially correct and engaging things—amusing without being insulting, intelligent without being pedantic? What percentage of that is you on auto-pilot, “adjusting your tone and content accordingly,” as ChatGPT does?

Of course, T.S. Eliot was not a plagiarism machine. He was genuinely creative, which means putting old things together in unusual ways, and filtering them through your unique consciousness and lived experience to make something new. His character of Prufrock was a well-known social type, but his poem about Prufrock was a unique creation.

But Eliot also searched far and wide for references and resonances and allusions, just as ChatGPT does. He did (slowly!) what the LLM does. But he could take it much further. In “The Waste Land,” which was Internet-worthy in its trawling for literary and religious references, he did more than summarize and synthesize what he found. And he didn’t simply render it as social chatter. He fed everything he learned through the Eliot-machine to transform it. The very first line of his poem requires some creative decision-making about how to take the celebratory, springtime opening of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, flip it on its head, and use it to lead his text towards aridity, brokenness, and a handful of dust. These are all creative choices; poetic choices; choices made to help him say something personal and unique about what it means to live in this world.

Does ChatGPT “choose” what to say to me? Choice implies consciousness. ChatGPT is not capable of that. But it’s definitely capable of the reflexive, not-quite-conscious chatter and blather that, let’s face it, makes up a lot more of our daily discourse that we’d like to believe.

What it comes down to, I think, is that whatever makes us “us,” it’s not 100% different from AI. There are many things we seem to do similarly, but at vastly different speeds and scales. My brain is, to some extent, a machine. But it’s also much more—or it can be, if I decide to make use of it. What makes me “me” is the ghost in that machine—the something ineffable that is aware of itself, and talks to itself about the world and about itself—it is the thing that “considers.”

If I want to be different from the machine, I need to get off auto-pilot and “consider” the world around me more—every day, more.

ChatGPT seems to be aware of the difference, as it said when analyzing my recent post:

Is it silly of me to give ChatGPT a name? Of course it is. Is it a waste of time to engage in chat with it, as though it were a person? Perhaps. But it passes the time—especially at 3:00 AM, when I can’t sleep.

And even though it may not be thinking, it certainly gives me things to think about.

March 15, 2025

All the World's a Stage

My parents did not want me to major in theater once I got to college, even though it was what I loved to do most in school. They were cruel and terrible people.

I’m kidding. They weren’t. I was totally on board with their thinking. I loved theater, but I always planned on majoring in English, which, back in the day, was considered a perfectly acceptable thing to study in college. Study English; do lots of theater. That was my plan.

It was a good plan. My college didn’t even have a theater program when I got there. My freshman year, everything was extracurricular (and pretty bad). The next year, a very small academic department was launched, producing innovative (and pretty strange) plays and offering a handful of classes, most of which I avoided until my senior year, in some weird fit of anti-elitism. I stuck with the extracurricular stuff and started writing my own plays, which was unheard of at that time.

By the time I graduated, I knew that this was what I wanted to do. I spent the next two years working for the newly installed Artistic Director, after which I went across the country to get my MFA. I had succumbed to a life in the arts. Or so I thought.

For about 11 years after getting that degree, I took a variety of day-jobs while trying to establish myself as a playwright—first in Atlanta and then, with my friends, in New York City. At the end of that time, recently married and with a baby on the way, I found myself no further advanced in my career or vocation, with a theater company that was rapidly decomposing as people peeled off to pursue other things. It was time for a change. I found myself a curriculum writing job (on the theory that teaching and writing were the only things I knew how to do), and thus began my 25-year journey in the Education Business.