The Fickle Feather of Ma'at

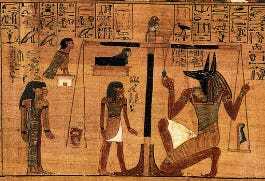

Many people, in many times and places, have held beliefs about the afterlife and the ways in which actions and choices from life will be judged. The ancient Egyptians had the idea of your heart being weighed against a feather from the goddess, Ma’at. The Hindus had the idea of karma, where the actions in this life affect the kind of life you come back to in reincarnation. Some people believe in heaven and hell. Some people believe we make heaven or hell right here on earth.

In all of these belief systems, actions have consequences. Important consequences. It’s something we humans have figured out, pretty much wherever we’ve set down roots on this planet.

And, for just as long, we’ve tried to find ways to weasel out of those consequences.

Once upon a time…I was leading a project for a Major Urban School district, designing and creating a standardized curriculum to be used across all of its middle and high schools. My team was working closely with advisory groups of teachers from each subject area, and one of the things they wanted to know was how scripted the curriculum was going to be. My team was trying to get district leadership not to demand a fully scripted set of lesson plans, but, instead, to let us set weekly learning objectives aligned to the state standards, and then provide teachers with a variety of instructional suggestions, and the occasional model lesson, to use as guides. We felt this struck the right balance between the district’s need for more standardization and coherence across (and within) its schools, and the teachers’ needs for professional autonomy and the ability to deal with the needs of individual classrooms and kids.

Some teachers approved of this approach. Most said nothing, resigned to accept whatever they were given. And then there was this one English teacher, who nodded along as I explained things, and then said, “As far as I’m concerned, give me 180 scripted lesson plans and tell me what to do with every fucking minute of every fucking day, or leave me the fuck alone to do my job.”

He didn’t want those 180 scripted lesson plans, mind you. He wanted to be left alone. But somehow, in his mind, the misery of having his job reduced to reading from a script was preferable to being held accountable on a weekly basis to meeting certain goals and objectives. He wanted to do what he wanted to do, with nobody sitting in judgment. He felt—as many teachers I’ve met have felt—that he was accountable to no one’s judgment but his own, that no one was qualified to hold him to account for the instructional decisions he made.

But, wait—don’t most teachers have some kind of district-mandated pacing plan that they have to follow?

They certainly do. But many of those plans simply list topics to be taught, or larger standards to be addressed. They don’t break those down (or “unpack” them, as we like to say) into clear, measurable objectives that build towards broader goals. There’s a big difference between telling a teacher to “cover” something next week, and spelling out exactly what her students should know and be able to do by the end of that week.

We’re talking about accountability here, in case you missed the subtitle of the post. And accountability is one of those things that people claim to love, as long as the eye of judgment is pointed at somebody else.

What is it?When we talk about accountability, we’re usually talking about one of two things: making sure people have done what they’ve promised to do (or been asked to do), or imposing some kind of consequences on them (good or bad) for what they have done or failed to do. “Hold them accountable” can mean either of those things—oversight or consequences. Because so much weight falls on the “consequences” part, and so many people do the “oversight” part poorly or haphazardly, the entire idea tends to feel punitive and something to be avoided at all costs. For a brief period when I used to lead workshops on the topic, I would start by asking participants to list all the words they thought of when I said “accountability.” The words they listed were always, without exception, negative.

Henry J. Evans, in his book, Winning with Accountability, tries to present the idea in a more positive light. He says that the word means, “Clear commitments that, in the eyes of others, have been kept.” To him, accountability is not a uni-directional thing, but is, instead, a relationship. If you are my manager, it’s not just that you hold me accountable for meeting certain goals; I also get to hold you accountable for setting goals that are clear and achievable.

And that ought to be a good thing—a positive thing. I want to succeed at my job, after all, and it’s hard to do so if I don’t know what the job is or what my manager needs from me. A healthy accountability relationship should make both partners happier. In theory.

How to be clearSetting clear objectives doesn’t mean speaking louder, though some managers seem to think that’s all that’s required. Clarity means helping the other person succeed by letting them know exactly what you need, and what “good” will look like.

That’s not as easy as it sounds. We use a lot of slippery words in everyday speech—often without realizing it. We say, “get it to me soon,” without specifying what “soon” means to us. Maybe I think ten minutes is soon enough, but you think an hour is sufficient. If we walk away from a conversation holding those two, separate ideas, we’re going to end up in a bad place.

Is “end of day” any better? Maybe. But is that the end of the working day, or the end of the calendar day? Your time zone? My time zone?

AND: If I ask for something by the end of the day, but I have no intention of reading it until tomorrow morning, wouldn’t it be better to say, “on my desk by 9AM,” to give you that extra time to work on it, if you need it? Why make a demand that actually doesn’t matter?

All sorts of words and phrases can be traps—requests that require people to read our minds, and that punish them if they fail. If we want people to succeed—if we want them to give us what we need—we need to think carefully about what we’re asking for and how we’re asking:

Or, for example, “I’m going to make America great again,” or, “I’m going to stop price gouging.” Empty promises? Maybe, maybe not. It’s hard to tell when the language is so vague. Neither of the statements is a “clear commitment” whose successful fulfilment other people would be able judge. Who’s to say what “great” means? Who’s to say that a price reduction is deep enough to no longer be considered “gouging,” or if the high price was the result of gouging in the first place? Which is precisely why politicians like to use this kind of language. They can claim success using whatever criteria they feel like using. They can move the goalposts. They can invent goalposts that never existed before. That’s part of the game.

In our lives, if we want to demand clear commitments from other people, and if we want to be successful at delivering on the commitments we’ve made, what would better language look like? Instead of asking for “a proposal,” should you specify how many pages, what font size, what the title should be, how many sections it should contain and what each section is, what the introduction should state, what the core arguments are, and so on? Would that make clear what “good” looks like?

I mean…you could do that. That’s the 180 lesson plan approach. But it’s an awful lot of work for you, and it makes the other job pretty lousy. That’s micromanaging, not managing. And nobody enjoys that.

There’s a sweet spot in between the extremes of micromanaging and, well, abandonment. You could paint a picture of what you’re looking for. Maybe something like, “I need a proposal to submit to the board, to explain what the project is, why it’s the right idea, and why we need the funding to do it this year instead of next. They love data, so give them some real examples of what we could accomplish and some decent numbers on ROI, if you can get Sales to commit to anything. Ten pages, tops, with a solid executive summary, because half of them will only read that.”

Will your employee know how to give you what you want? Probably. You’ve given them the tools they need to succeed, but you’ve also given them space to figure out the best way to get there. They get to make some choices, using their skills, their intelligence, and their creativity. And they get to be held accountable for the wisdom and efficacy of the choices they make. In a setting like that, people who make better choices—who deliver better and more interesting results—get to rise and prosper. The micromanaged mice, not so much: they all deliver exactly the same thing. The only way they can distinguish themselves is to do it faster and with fewer complaints.

Freedom within clear boundaries and directions is what we wanted for our teachers back in the day—and it’s precisely what that English teacher did not want. He wanted success on his own terms. He wanted success without any terms. He wanted to be left alone to do as he pleased—the Byronic hero of education, facing the challenges of the world alone. But how many people get to live like that? How many people should?

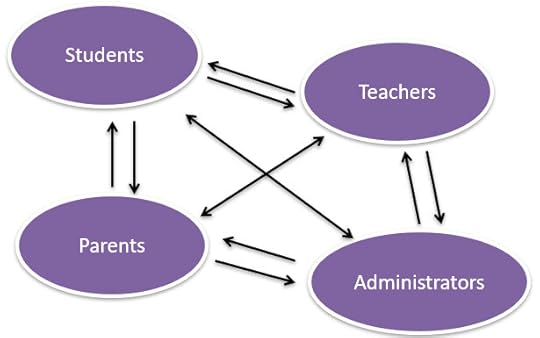

What do we owe each other?A healthy organization—or society—is one that has a culture of mutual accountability, with two-way arrows connecting all the stakeholders to each other—a web or network of accountability relationships. In a school, it might look something like this:

In my workshops, we would talk about each one of these arrows, and what each “stakeholder” in education actually needs from the other. There’s a lot going on in this web, and most of us don’t give it a thought.

And this isn’t even the whole picture, Widen the lens and you can include local, state, and national policy makers and elected officials. We are all connected to each other; we all need things from each other in order to succeed—even people we’ve never met. We all owe each other something.

Let justice be doneThat’s all well and good, but what about the tough part—the consequences? What about bringing down the hammer? That’s the part people focus on most often, which is why we hate the whole idea of accountability.

Look, we all know there have to be consequences in life. There’s a difference between freedom, which has some limits (if only to avoid infringing on the freedom of others) and license, which is just reckless abandon. Supernanny taught us what happens to children when parents are afraid to set rules and boundaries and then enforce them. Chaos is what happens. Willful, unhappy children, and exhausted, miserable parents. A society of id-monsters running around, doing whatever they want, to whomever they want, is a nightmare, and societies don’t like to live in a nightmare for long. If we can’t hold each other accountable in a civil society, we don’t end up in a chaotic state of nature; we end up in a police state.

When we impose consequences on children, we do it to teach them, not to punish them (in theory). For adults, who are supposed to know better, it’s more of a mixed bag. We may set consequences to help the wrong-doer learn how to do better, or to warn other, potential wrong-doers to think twice. Or we may do it simply to punish people and satisfy a thirst for retribution. You must pay for what you have done. Justice must be done.

Come what may? No matter the cost to the rest of us? Some would say Yes.

There’s an old phrase: Fiat justitia ruat caelum. Let justice be done, though the heavens fall. Writers love to use the Latin, even though no ancient source seems to exist. The first use of the phrase in English dates to 1601. But whatever. It sounds cool and severe in any language. And it sounds satisfying. Justice matters more than our comfort. Justice matters more than politeness. Right the scales and punish the wicked, no matter how much damage it might do. It’s worth it in the long run. If people fuck around, they have to find out. Period. So says Gritty, and who am I to argue?

And yet.

The idea has fallen in disrepute in our country over the past few years—at least for a privileged few. A former president violated important norms of both polite society and political office. He faced no consequences for it. He had previously led a life of rudeness, norm-breaking, and outright cheating in business, and never had to pay any kind of price for it. Someone else was always left to clean up his messes. Past treatment seemed to demand similar future treatment.

And then he was accused—and indicted—of breaking actual laws. He did things, or caused things to be done in his name, that cried out for some kind of consequence. You can’t just let people break laws, even if they’re powerful people, famous people. Can you? After all, what’s a law that isn’t enforced? Just a pretty idea.

And then…the hands of justice wavered. Politicians from his party could not bear to make him face consequences if those actions might weaken their own power. Politicians from the other party, once in power, worried about seeming heavy-handed in going after a rival. The news media pulled its punches and used weasel words in describing him, desperate to be seen as non-partisan and objective…as though “objective” meant ignoring the truth.

Maybe the heavens would have fallen if justice had been done. Maybe not. The heavens may fall, now, precisely because justice was not done. Because he’s about to be our president again. Un-chastened, unashamed, unpunished, and unapologetic. He has taught us that he is above the reach of the law—beyond the judgment of mere mortals. Whether this turns out to be a good thing for our country remains to be seen. History would seem to indicate that god-like immunity and impunity for the ruler does not end well for the people, but, you know…we’ll find out. We always find out.

The PriceIf accountability is a web of mutuality more than a command or a punishment, if it’s a system that helps us give each other what we need, than a violation of trust or an abandonment of a commitment can fray or break one of those connections, and little by little, the web unwinds. Unwind it all, and each of us is left alone. It’s a cold world to be alone in.

It’s often said that if you want to accomplish something, it’s good to have an “accountability partner.” You want something for yourself; your partners want something for themselves. You check in with each other every day or every week to hold each other accountable. Did you stay away from sweets? Did you take a drink? Did you write your five pages?

We know this works. If you want the results you say you want, you often need someone to help you stay on track; you need someone to hold you accountable to the promises you’ve made—even the promises you’ve made to yourself.

We also know it’s a pain in the ass—because a part of us would love to eat the donut, take the drink, and watch another season of “Love is Blind” instead of writing. We want what we want, but sometimes we need a kick in the butt to go get it.

None of us is alone. We rely on each other for so many things, whether we work together, or are in a family together, or simply live in community together. We need each other. We owe each other. And holding ourselves and each other accountable is how we get the good things we want in life. Even though, sometimes, it’s a pain to have standards. Even though it’s scary to have to wag a finger and scold, or make corrections to someone’s work, or put a powerful person in prison.

If we fail ourselves, or if we fail each other, then judgment will come. Maybe not at the time we imagine, or in the place we imagine, or in the way we imagine, but it will come. It always comes. There is always a price to be paid for not doing what we know we should have done.

The scale awaits.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers