Prioritizing the "Aha!" Moment

If I’m talking with teachers about something like getting math students engaged in problem-solving discourse, somebody will always say, “But what about time on task?” If I’m writing something about argumentation using textual evidence, somebody will always want to comment about time-on-task. You can invent this new strategy or that new reform, but in the end, if students would simply spend more time engaged in their work, they would learn more. Is that not so?

Well…it is and it isn’t. As David Berliner says, “What is wanted is a measure of time-on-the-right-tasks” (The Nature of Time in Schools, 1990, p. 18). All instructional time is not created equal, and, as it turns out, all “engaged” time may not be the same, either.

Scenes from a Broken Hand is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In a chapter from Perspectives on Instructional Time (Fisher and Berliner, eds., 1985), Linda Anderson describes a team observing eight different 1st-grade classrooms. The students appear to be extremely diligent and well-behaved, doing exercises in their math and reading workbooks, completing their work in the allotted time, and being kind and polite to each other and to the teacher. These should be dream classrooms for teachers. However, when asked questions about the work they’ve just done, a large number of the students don’t have a clue what any of it means. “I didn’t understand that, but I got it finished,” one boy says (p. 195).

His response may be more typical than we’d like to admit. In the same chapter, the researchers observe a very happy set of students completing a fill-in-the-blank vocabulary activity, in which every blank is exactly the length of the word needed to fill it. The students are happy because they have figured out how to complete the activity without having to learn most of the words. It’s just a matter of making things fit. The procedure has become the content. Completing the worksheet is the actual learning objective, regardless of what the teacher may think is going on. Time-on-task? Absolutely. Time-spent-learning? Not so much.

One definition of student engagement, drawn from six years of classroom observation as part of the Beginning Teacher Evaluation Study (BTES), is known as “Academic Learning Time,” or ALT (Fisher, et al., 1978). ALT is the amount of time during which students are actively and productively engaged in real learning. As Berliner (1990) defines it, ALT is “that part of allocated time [the time set aside for instruction]…in which a student is engaged successfully in the activities or with the materials to which he or she is exposed, an in which those activities and materials are related to educational outcomes that are valued” (p.5).

Let’s slow that down and look at some of the key words in his definition.

Engaged: The researchers in the BTES study found that teachers who were more interactive in their teaching styles, who engaged students in academic discourse throughout instruction and practice, helped students perform at higher levels in both math and reading. Students whose skill practice was silent, isolated, and tied to a workbook showed slower progress and slighter academic gains. Berliner talks about the value of pacing a lesson briskly, to keep the discourse lively and the instructional movement exciting. It’s interesting how many teachers take the opposite approach, slowing things down to make sure everyone understands every word (like I’m doing here? Oops).

Successfully: Berliner and others who write about ALT stress that individual student success with the work must be a part of the equation—and they insist on very high rates of success; 70% or even 80% at a minimum. To them, this is a crucial difference between being merely on-task and being engaged in learning. After all, if students can’t demonstrate their learning, can we really say their time-on-task led to learning?

Related to Educational Outcomes: This touches back to our anecdote about the vocabulary worksheet. “Time-on-the-right-task” requires that student work be aligned with the topics and the rigor-level indicated in the teacher’s learning objectives and the related state standards. This might seem like a no-brainer, but there’s a difference between being aligned to a general topic on a pacing plan, and being aligned to a specific learning objective that is pitched at the appropriate level of difficulty.

That Are Valued: And, as the final cherry on top of the ALT sundae, we need to make sure that objectives set by the teacher and the work being asked of students are valuable, meaningful, and relevant to both the school and the student. Worksheets and practice sets might be valuable and meaningful tasks for students…or they might not be. If it’s just busy-work, we may get compliant and well-behaved students, but we likely won’t get genuinely engaged learning, and, as we saw above, we may not get any learning at all.

Clearly, the more of our instructional time that students spend in ALT, the more they will learn. But how much of our class time do students actually spend in ALT? Nationwide, the answer has been pretty grim. Researchers have found that some schools dedicate as little as 50% of their allocated time to instruction at all (after accounting for administrative tasks and classroom management issues), and that real engagement rates within that instructional time can range from 50% to 90%, depending on the skills of the teacher (Hollowood, Salisbury, Rainforth & Palomboro, 1995). At the low end, with students spending half of their class time in any kind of instruction, and half of that time in any kind of meaningful work, this means there are students who are spending no more than 25% of their time actively learning. One wonders what percentage of that time is spent at high levels of success.

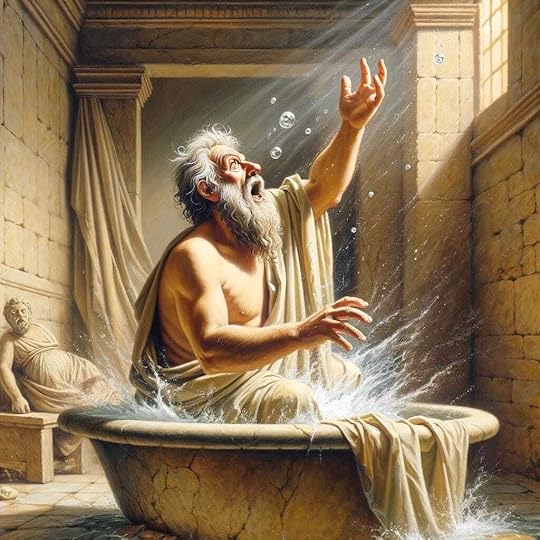

This is why the “Aha Moment” is so important. That moment of connection and realization is a great signal to us that a student isn’t just “doing it,” but is actually “getting it.” It’s a sign that something is actually changing inside the student—that a new idea is forming, or a change of perspective is happening. It’s a physical thing, and we’ve all felt it—we’ve all felt that moment where something just shifts and changes, and we suddenly see things differently. It’s thrilling. It’s addictive. And it leaves its mark.

Yes: to learn is to be changed. No one should walk out of a semester or year-long class exactly the same as when they walked in. What a waste of time! Maybe it’s your content knowledge or your ideas about the world that change. Maybe it’s a particular skill that you develop or improve. Whatever it is, a learning experience should be a workout; it should stretch the muscles and leave you stronger or more limber than you were before. And a learning process should be like a long-term exercise regimen; it should work upon you and leave its mark on you. Even if it’s just a new idea you never had before, once you have it, you can’t ever un-have it. That light bulb never gets turned off.

If we think about the moments where we saw a light bulb come on for a student, it’s pretty clear (at least in my experience) that those moments come in the midst of some kind of challenging, productive work the student is doing or discussion the student is having. Those moments don’t often come in the middle of a lecture, and they don’t often come at Question #11 in a practice set. They come when we’re pushing up against the outer edge of a student’s Zone of Proximal Development, challenging them to go deeper and further than they’ve gone before. They may come after several failed or botched attempts, when the pieces finally fall into place, and the details fit together to reveal the big picture and big idea that the student hadn’t seen before.

Those “Aha Moments” are why we’re all here. They are the brass ring. They’re what we ride the carousel for, year after year. They’re why our students are on the ride, too, even if they don’t realize it. They’ll never reach for that brass ring if they don’t know it exists. We have to give them the taste for it—the hunger for it. And they’ll never catch it if they don’t take the risk to stretch out their arms and reach—further than feels comfortable—further than they think they can go.

But once they’ve done it—once they learn what it feels like—there’s no stopping them.

Scenes from a Broken Hand

- Andrew Ordover's profile

- 44 followers